Abstract

A 38-year-old woman was diagnosed with cutaneous anaplastic T-cell lymphoma that proved refractory to methotrexate, bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, interferon γ-1b, interferon α-2b, vorinostat, and pralatrexate. She was therefore started on the newly approved monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody brentuximab vedotin. Treatment with brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg IV every 3 weeks quickly led to disappearance of her cutaneous tumors. The day after her second brentuximab infusion she developed word-finding difficulties and unsteady gait. Due to further neurologic deterioration, she was admitted to an outside hospital. Brain MRI revealed multifocal enhancing white matter lesions throughout bilateral cerebral hemispheres and posterior fossa (figure, A–C). Brain biopsy was performed 15 days after her last brentuximab dose to rule out metastases and she was diagnosed with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (figure, J). The patient was discharged home with hospice care. Upon discharge, she was started on prednisone 50 mg daily to help treat her eczema. Her family brought her to our clinic for a second opinion.

A 38-year-old woman was diagnosed with cutaneous anaplastic T-cell lymphoma that proved refractory to methotrexate, bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, interferon γ-1b, interferon α-2b, vorinostat, and pralatrexate. She was therefore started on the newly approved monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody brentuximab vedotin. Treatment with brentuximab 1.8 mg/kg IV every 3 weeks quickly led to disappearance of her cutaneous tumors. The day after her second brentuximab infusion she developed word-finding difficulties and unsteady gait. Due to further neurologic deterioration, she was admitted to an outside hospital. Brain MRI revealed multifocal enhancing white matter lesions throughout bilateral cerebral hemispheres and posterior fossa (figure, A–C). Brain biopsy was performed 15 days after her last brentuximab dose to rule out metastases and she was diagnosed with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (figure, J). The patient was discharged home with hospice care. Upon discharge, she was started on prednisone 50 mg daily to help treat her eczema. Her family brought her to our clinic for a second opinion.

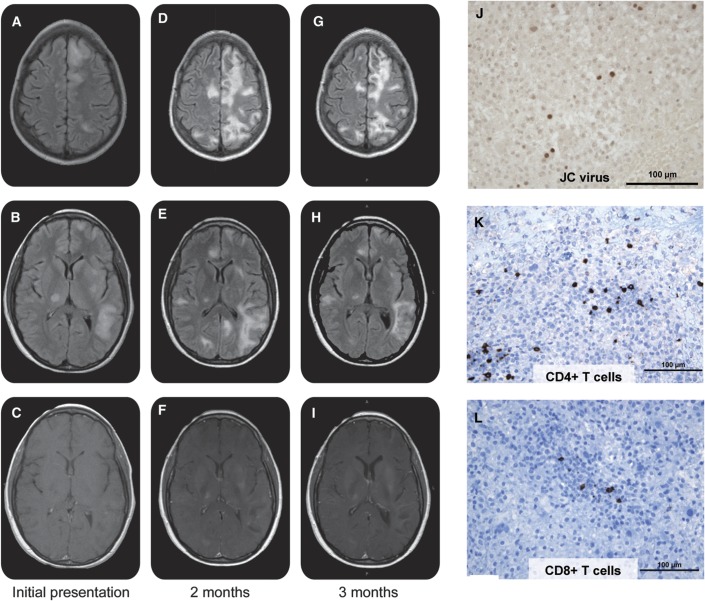

Figure. Radiographic and pathologic evidence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy–immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

(A–I) Axial MRI over time shows worsening of signal abnormality on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (top 2 rows) at 2 months (D, E) compared to initial presentation (A, B) with some improvement at 3 months (G, H). There is significant increase in gadolinium enhancement 2 months after initial presentation (F) compared to initial imaging (C), which is essentially unchanged at 3 months (I). (J–L) Left frontal brain biopsy reveals subsets of large gemistocytic astrocytes and oligodendrocytes with prominent nuclear enlargement that were positive after immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody against JC virus (Santa Cruz Immunochemicals, Santa. Cruz, CA) (J). Multiple infiltrating T cells are seen on immunohistochemistry staining for CD4 (K) and CD3 (L).

The patient presented to us with a mixed nonfluent aphasia, mild apraxia, 4/5 strength in all extremities, and gait ataxia that required one person assist. Repeat brain MRI demonstrated worsening white matter lesions and contrast enhancement, concerning for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) (figure, D–F). Additional immunostaining of her brain biopsy was performed, which demonstrated a mixed population of T-cell infiltrates with a predominance of CD4+ T-cells (figure, K and L). We continued her on high-dose oral corticosteroids for suspected PML-IRIS. Since she had not received brentuximab in more than 8 weeks, we opted not to initiate plasma exchange therapy. Over the ensuing weeks, our patient demonstrated slow but definite improvement. She is currently ambulating without assistance and has increased spontaneous speech and comprehension. Her most recent brain MRI showed decreased lesion load and reduced enhancement (figure, G–I). She continues to be followed closely clinically and with frequent MRIs.

Discussion

Recently, PML has been seen in an increasing number of patients receiving monoclonal antibodies. Most prominently, it has been described in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving natalizumab, an α-4 integrin blocker.1 However, PML has also occurred in patients receiving other immunomodulatory therapies.2

Several cases have been reported in patients on the B-cell-depleting anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab, and the adhesion molecule inhibitor, efalizumab, which binds the α-1 integrin CD11a.3 The Food and Drug Administration recently added a black box warning to the package insert of brentuximab in response to the report of 2 additional cases of PML that were associated with this medication (included our patient). Brentuximab is an antibody-drug conjugate linking the antimicrotubule agent monomethyl auristatin E to a CD30 monoclonal antibody. CD30 (TNFSR8) is frequently expressed on anaplastic large-cell lymphoma cells as well as in Hodgkin lymphoma.4 It is not surprising that alterations in immune cellular function can lead to PML; however, it is not entirely clear why PML occurs with higher frequency in certain patient populations or with particular immunomodulatory agents. Our patient developed PML after 2 courses of brentuximab, which raises concern that this therapy increased her risk for developing PML, although the combination of her underlying lymphoma and exposure to prior immune-altering medications likely added to that risk.

Patients with PML frequently develop IRIS. The exact pathobiology of IRIS is not entirely understood, although rapid infiltrates of cytotoxic T-cells have been implicated.5 While reconstitution of the immune system is important for controlling the JC virus infection, CNS inflammation due to IRIS can result in death or permanent neurologic disability; therefore, IRIS needs to be recognized early.6 The diagnosis of PML-IRIS can be challenging as there currently are no established diagnostic criteria, though rapid clinical worsening and patchy contrast enhancement on MRI raise the concern for IRIS.6 In our patient, the exact timing of onset of IRIS is not entirely clear as she was not followed closely until establishing care with us. However, the presence of T-cell infiltrates on her brain biopsy and enhancement on her initial MRI suggests early IRIS or simultaneous PML-IRIS. Previous reports have suggested that treating patients with PML-IRIS with corticosteroid therapy may help facilitate better neurologic outcomes.5 Additionally, severe cases of CNS-IRIS may require a longer duration of corticosteroid treatment, as highlighted by our case. Studies of the benefits, optimal timing, dosage, and duration of corticosteroids are needed to help guide long-term management in these patients. While management of PML and PML-IRIS can be challenging, early initiation of hospice care may not be the appropriate decision. As highlighted in this case report, favorable outcomes are possible with patience and close monitoring.

Footnotes

Author contributions: G. von Geldern: drafting and revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. C. Pardo: analysis or interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript for content. P. Calabresi: drafting and revising the manuscript for content. S. Newsome: drafting and revising the manuscript for content, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data.

Disclosure: G. von Geldern and C. Pardo report no disclosures. P. Calabresi has received consulting fees from Teva, Biogen-Idec, Novartis, Genzyme, Vertex, Vaccinex, Abbott, and Johnson & Johnson; he has done contracted research for Teva, Biogen-Idec, Novartis, Vertex, Abbott, Bayer, and EMD Serono. S. Newsome is a consultant for Biogen-Idec and Novartis and has received speaker’s honoraria from Biogen-Idec and Teva pharmaceuticals. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Clifford DB, DeLuca A, Simpson DM, Arendt G, Giovannoni G, Nath A. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:438–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Major EO. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients on immunomodulatory therapies. Annu Rev Med 2010;61:35–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson KR, Focosi D, Major EO, et al. Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: a review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanale MA, Forero-Torres A, Rosenblatt JD, et al. A phase I weekly dosing study of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed/refractory CD30-positive hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:248–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan IL, McArthur JC, Clifford DB, Major EO, Nath A. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in natalizumab-associated PML. Neurology 2011;77:1061–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison DM, Newsome SD, Skolasky RL, McArthur JC, Nath A. Immune reconstitution is not a prognostic factor in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neuroimmunol 2011;238:81–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]