Abstract

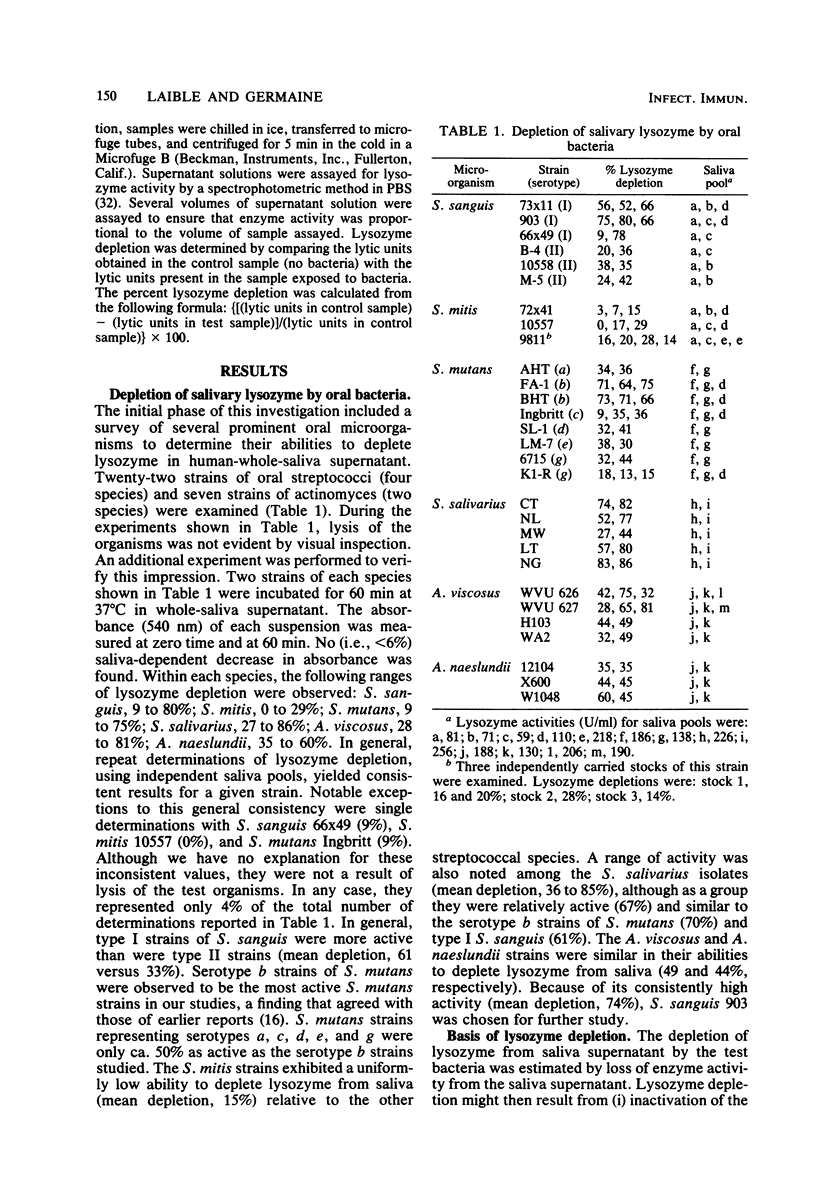

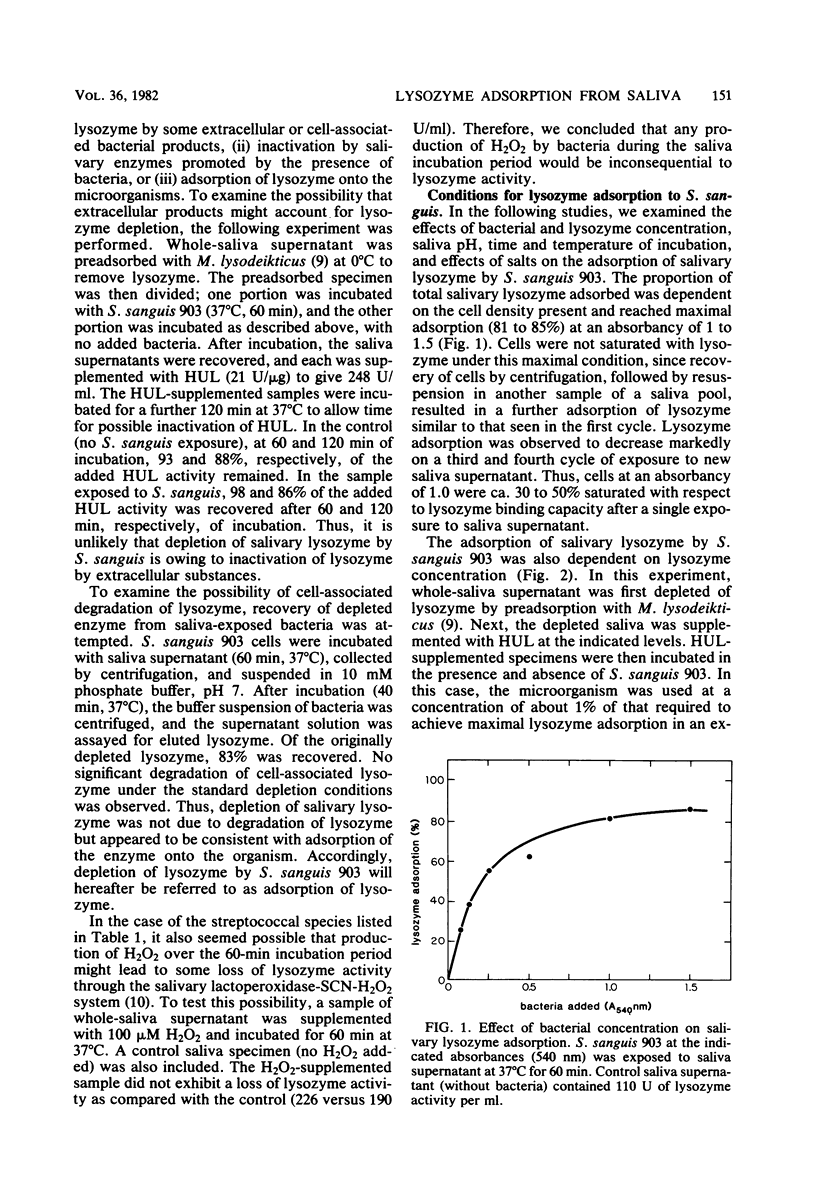

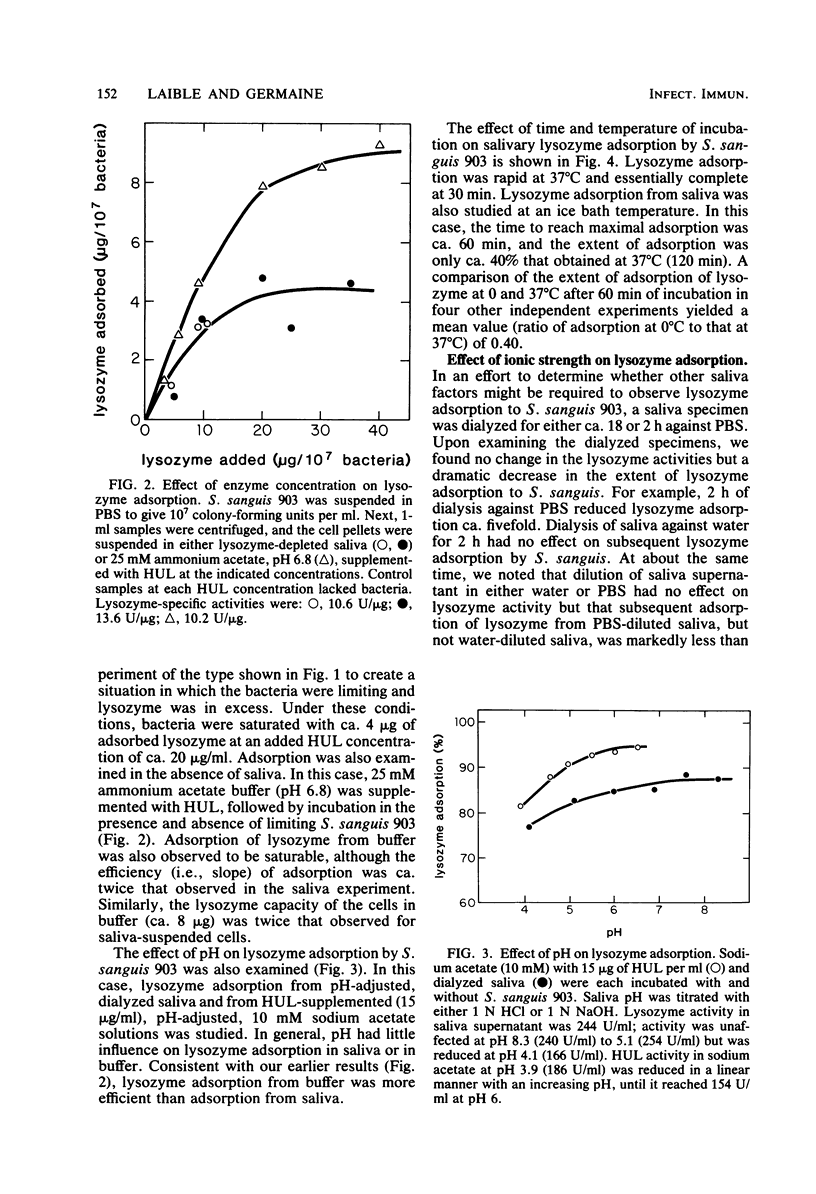

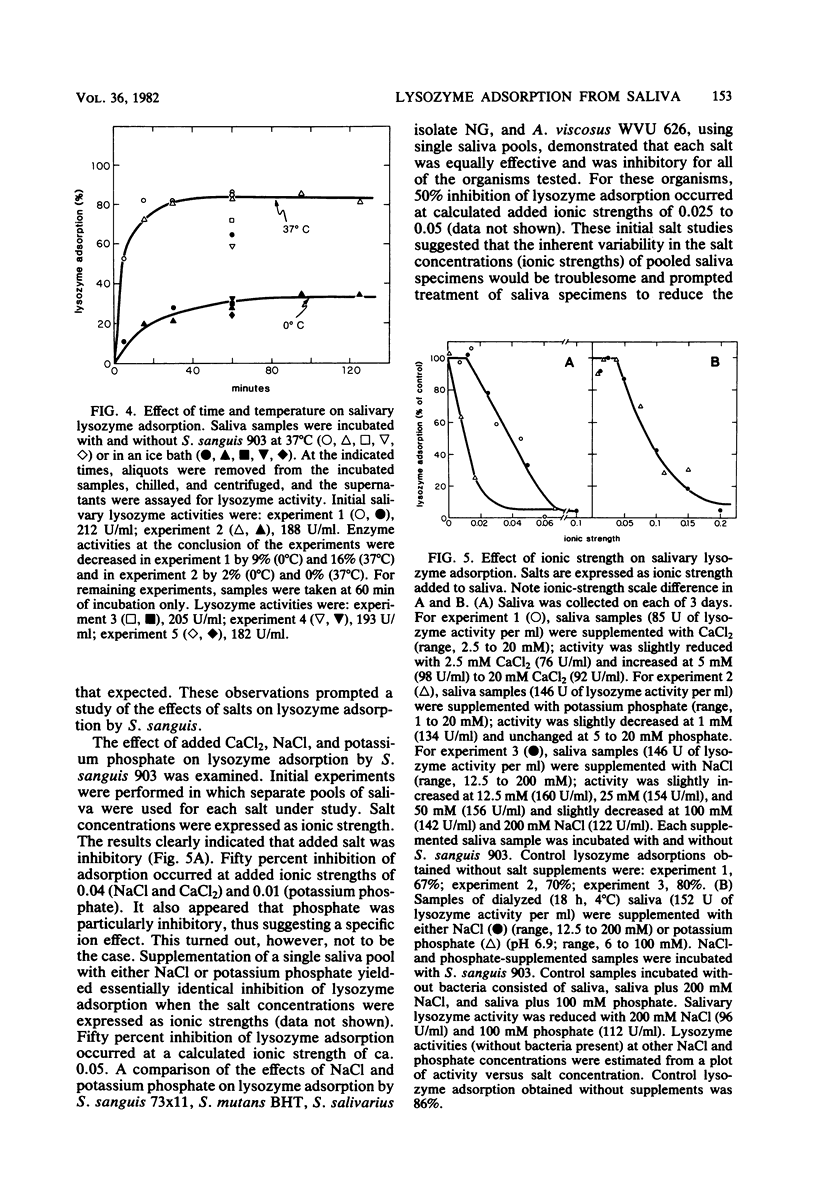

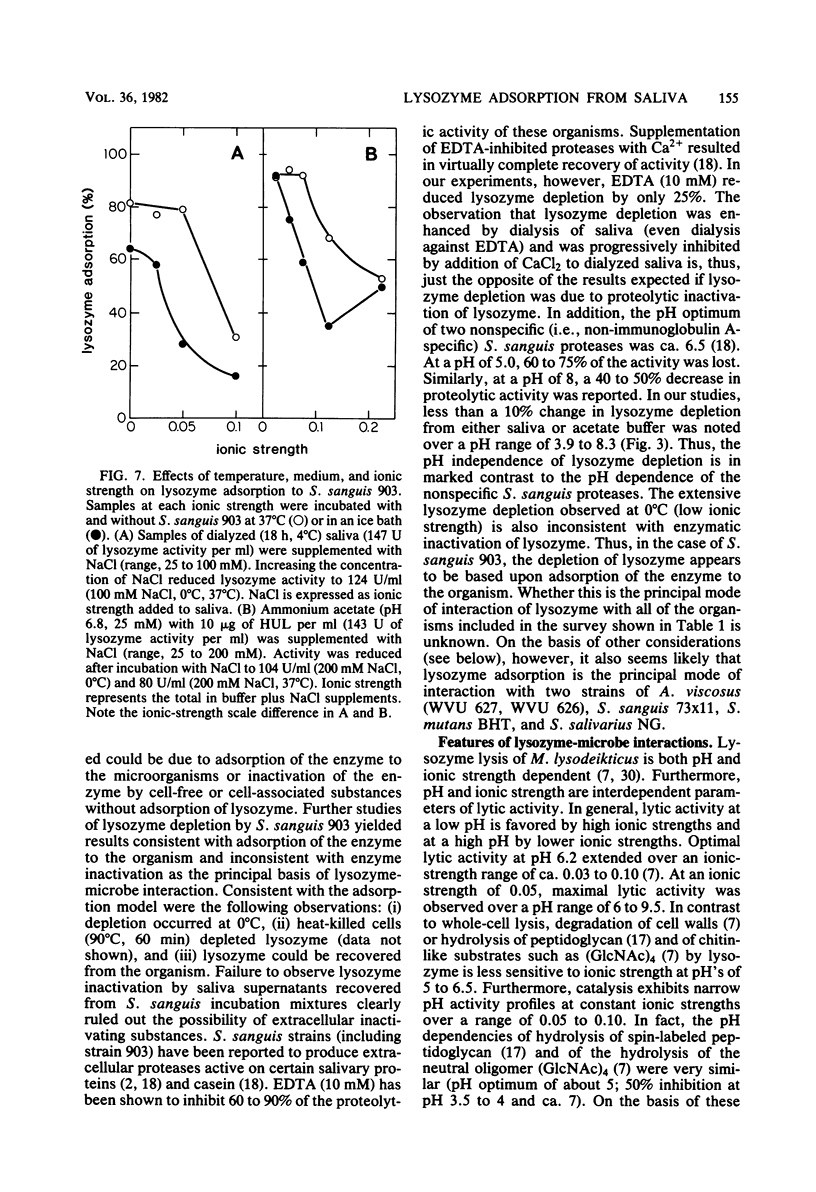

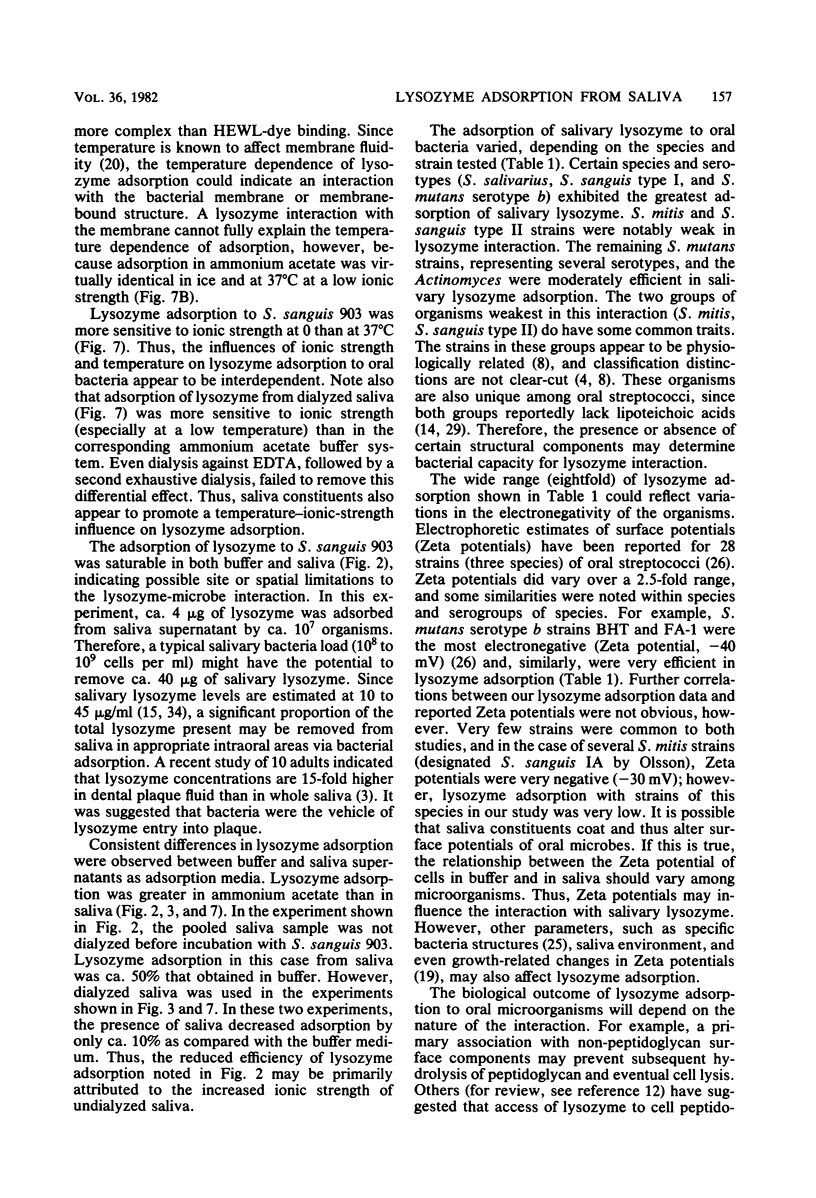

Several strains of Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus mitis, Actinomyces viscosus, and Actinomyces naeslundii plus fresh isolates of Streptococcus salivarius were surveyed for their abilities to deplete lysozyme from human-whole-saliva supernatant. Bacteria were incubated in saliva for 60 min at 37°C and then removed by centrifugation, and the recovered supernatant solutions were assayed for lysozyme activity by using whole cells of Micrococcus lysodeikticus as the substrate. Mean lysozyme depletions by bacterial strains varied over a wide (eightfold) range. The greatest mean depletion of lysozyme (60 to 70%) was observed with S. sanguis (biotype I), serotype b of S. mutans, and the fresh S. salivarius isolates. The lowest mean depletion was noted with S. mitis (15%) and biotype II S. sanguis (ca. 30%). The remaining species and strains exhibited an intermediate degree of depletion. In studies with S. sanguis 903, lysozyme was depleted by normal or heated (90°C, 30 min) bacteria and could be recovered from the organism. Furthermore, under appropriate conditions, lysozyme depletion by cells at 0 and 37°C was very similar. On the basis of these observations, we concluded that depletion was due to the adsorption of lysozyme by the organism. With S. sanguis 903, lysozyme adsorption depended on the concentration of bacteria, time of incubation, and the ionic strength of the medium. The extent of adsorption, however, was independent of pH's of 3.9 to 8.3. When a low concentration of S. sanguis 903 was used, lysozyme adsorption reached saturation (4 μg of adsorbed lysozyme per 107 cells) at 20 μg of lysozyme added per ml. Salivary lysozyme adsorption by several other oral microorganisms (A. viscosus WVU 626 and WVU 627, S. sanguis 73×11, S. mutans BHT, and S. salivarius NG) was similar to that of S. sanguis 903 in sensitivity to ionic strength. Lysozyme adsorption by S. sanguis 903 from either a buffer solution or a saliva supernatant was more sensitive to ionic strength at 0 than at 37°C. On the basis of results from experiments in saliva versus buffer, we concluded that saliva had no major effect on the extent of lysozyme adsorption by S. sanguis 903 other than providing a source of ionic strength. A comparison of pH and ionic strength effects on lysozyme adsorption by S. sanguis 903 with literature reports of lysozyme lysis of whole cells and hydrolysis of cell walls, peptidoglycan, and (GlcNAc)4 suggested that adsorption by S. sanguis 903 was more dependent on electrostatic interactions than was lysozyme catalysis. The possibility is discussed that anionic bacterial surface components mediate lysozyme adsorption and temper the potential effects of lysozyme on the microorganisms.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Banerjee A., Banerjee A. C., Bhattacharyya B. Lysozyme-induced polymerization of tubulin. Burial of the colchicine-binding site as a probe. FEBS Lett. 1981 Feb 23;124(2):285–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLVIN J. R. A note on the stoichiometry of adsorption of anions by lysozyme. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1955 Jul;33(4):651–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choih S., Smith Q. T., Schachtele C. F. Modification of human parotid saliva proteins by oral streptococcus sanguis. J Dent Res. 1979 Jan;58(1):516–524. doi: 10.1177/00220345790580011301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. F., Hsu S. D., Baum B. J., Bowen W. H., Sierra L. I., Aquirre M., Gillespie G. Specific and nonspecific immune factors in dental plaque fluid and saliva from young and old populations. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):998–1002. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.998-1002.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies R. C., Neuberger A. Modification of lysine and arginine residues of lysozyme and the effect on enzymatic activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969 Apr 22;178(2):306–317. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies R. C., Neuberger A., Wilson B. M. The dependence of lysozyme activity on pH and ionic strength. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969 Apr 22;178(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facklam R. R. Physiological differentiation of viridans streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1977 Feb;5(2):184–201. doi: 10.1128/jcm.5.2.184-201.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germaine G. R., Tellefson L. M. Effect of human saliva on glucose uptake by Streptococcus mutans and other oral microorganisms. Infect Immun. 1981 Feb;31(2):598–607. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.598-607.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germaine G. R., Tellefson L. M. Simple and rapid procedure for the selective removal of lysozyme from human saliva. Infect Immun. 1979 Dec;26(3):991–995. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.3.991-995.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons R. J., de Stoppelaar J. D., Harden L. Lysozyme insensitivity of bacteria indigenous to the oral cavity of man. J Dent Res. 1966 May-Jun;45(3):877–881. doi: 10.1177/00220345660450036201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman H., Pollock J. J., Iacono V. J., Wong W., Shockman G. D. Peptidoglycan loss during hen egg white lysozyme-inorganic salt lysis of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 1981 May;146(2):755–763. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.755-763.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman H., Pollock J. J., Katona L. I., Iacono V. J., Cho M. I., Thomas E. Lysis of Streptococcus mutans by hen egg white lysozyme and inorganic sodium salts. J Bacteriol. 1981 May;146(2):764–774. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.764-774.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada S., Slade H. D. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Rev. 1980 Jun;44(2):331–384. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.2.331-384.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankiewicz J., Swierczek E. Lysozyme in human body fluids. Clin Chim Acta. 1974 Dec 17;57(3):205–209. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(74)90398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono V. J., MacKay B. J., DiRienzo S., Pollock J. J. Selective antibacterial properties of lysozyme for oral microorganisms. Infect Immun. 1980 Aug;29(2):623–632. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.623-632.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. S., Neuhaus F. C. Spin-label assay for lysozyme. Anal Biochem. 1978 Mar;85(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib R. S., Calvanico N. J., Tomasi T. B., Jr Studies on extracellular proteases of Streptococcus sanguis. Purification and characterization of a human IgA1 specific protease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978 Oct 12;526(2):547–559. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(78)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael J. C., Ou J. T. Binding of lysozyme to common pili of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1979 Jun;138(3):976–983. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.976-983.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odeberg H., Olsson I. Mechanisms for the microbicidal activity of cationic proteins of human granulocytes. Infect Immun. 1976 Dec;14(6):1269–1275. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.6.1269-1275.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson J., Glantz P. O. Effect of pH and counter ions on the zeta-potential of oral streptococci. Arch Oral Biol. 1977;22(8-9):461–466. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(77)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson J., Glantz P. O., Krasse B. Electrophoretic mobility of oral streptococci. Arch Oral Biol. 1976;21(10):605–609. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(76)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosan B. Absence of glycerol teichoic acids in certain oral streptococci. Science. 1978 Sep 8;201(4359):918–920. doi: 10.1126/science.684416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUGAR D. The measurement of lysozyme activity and the ultra-violet inactivation of lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1952 Mar;8(3):302–309. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(52)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa G., Weissmann G. Incorporation of lysozyme into liposomes. A model for structure-linked latency. J Biol Chem. 1970 Jul 10;245(13):3295–3301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virella G., Goudswaard J. Measurement of salivary lysozyme. J Dent Res. 1978 Feb;57(2):326–328. doi: 10.1177/00220345780570023001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. C., Gibbons R. J. Inhibition of bacterial adherence by secretory immunoglobulin A: a mechanism of antigen disposal. Science. 1972 Aug 25;177(4050):697–699. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4050.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. C., Gibbons R. J. Inhibition of streptococcal attachment to receptors on human buccal epithelial cells by antigenically similar salivary glycoproteins. Infect Immun. 1975 Apr;11(4):711–718. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.4.711-718.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]