Abstract

Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the genome of the cartilaginous fish, Callorhynchus milii (elephant shark), encodes a melanocortin-2 receptor (MC2R) ortholog. Expression of the elephant shark mc2r cDNA in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells revealed that trafficking to the plasma membrane and functional activation of the receptor do not require coexpression with an exogenous melanocortin receptor-2 accessory protein (mrap) cDNA. Ligand selectivity studies indicated that elephant shark MC2R-transfected CHO cells produced cAMP in a dose-dependent manner when stimulated with either human ACTH (1–24) or [Nle4, d-Phe7]-MSH. Furthermore, the order of ligand selectivity when elephant shark MC2R-transfected CHO cells were stimulated with cartilaginous fish melanocortins was as follows: ACTH (1–25) = γ-MSH = δ-MSH > αMSH = β-MSH. Elephant shark MC2R is the first vertebrate MC2R ortholog to be analyzed that does not require melanocortin receptor-2 accessory protein 1 for functional activation. In addition, elephant MC2R is currently the only MC2R ortholog that can be activated by either ACTH- or MSH-sized ligands. Hence, it would appear that MC2R dependence on melanocortin receptor-2 accessory protein 1 for functional activation and the exclusive selectivity of this melanocortin receptor for ACTH are features that emerged after the divergence of the ancestral cartilaginous fishes and the ancestral bony fishes more than 400 million years ago.

The salient features that distinguish the mammalian melanocortin-2 receptor (MC2R) from other mammalian melanocortin receptors (i.e. MC1R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R) are the following: 1) the requirement for interaction with melanocortin receptor-2 accessory protein 1 (MRAP1) to facilitate both the trafficking of MC2R to the plasma membrane and the functional activation of MC2R at the plasma membrane (1, 2), and 2) the strict ligand selectivity of MC2R for ACTH coupled with the inability of MSH-sized ligands (i.e. α-MSH, β-MSH, and γ-MSH) to activate this melanocortin receptor (MCR) (3). As a result, MC2R is the most functionally constrained member of the MCR family in terms of ligand selectivity. These unique features have been observed in several studies on mammalian MC2R (4, 5), and relatively recently these same constraints on activation were observed for the MC2R of the teleosts, Danio rerio (zebrafish) (6) and Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout) (7), and the MC2R of the amphibian, Xenopus tropicalis (8). Based on these observations, it would be reasonable to propose that the MC2R of all the bony vertebrates (i.e. the ray finned fishes, lobe finned fishes, and tetrapods) have these features in common.

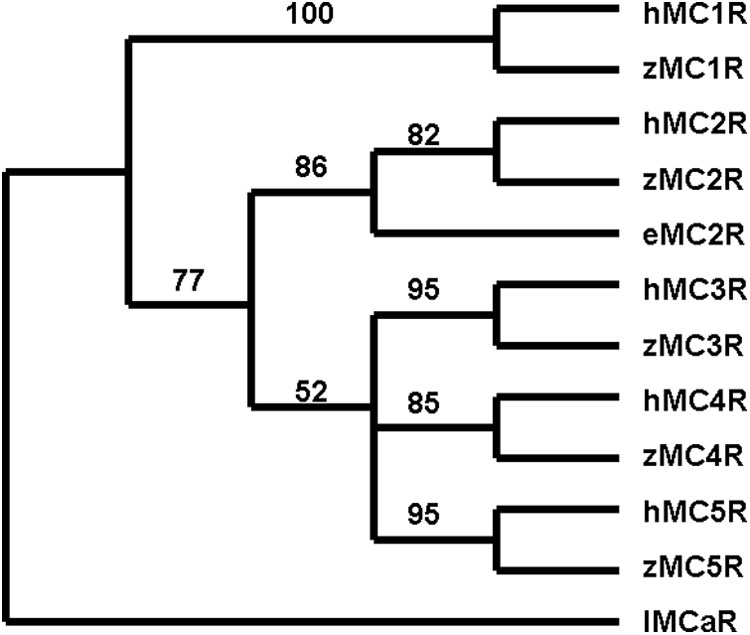

The presence of at least five mcr paralogous genes in the genomes of teleosts and tetrapods appears to have been the result of two genome duplication events and at least one local gene duplication event that have occurred during the radiation of the chordates (9). In this scenario, duplications of an ancestral mcr gene, of presumably protochordate origin, would yield five mcr paralogs in the ancestral jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes) (10). During the subsequent radiation of the gnathostomes (i.e. cartilaginous fishes, bony fishes, and tetrapods) the evolution of the MCR gene family has been influenced by gene loss (11) and lineage-specific gene duplication events (12). In this regard, gene loss may be most evident in the cartilaginous fishes, one of the stem ancestral gnathostome groups (13). Studies on the shark, Squalus acanthias (14, 15), revealed the presence of orthologs of MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R in the S. acanthias genome. However, a recent analysis of the genome project for the holocephalan cartilaginous fish, Callorhynchus milii (elephant shark) uncovered orthologs only for MC1R, MC2R, and MC3R (10). The identity of the elephant shark MCRs was based on a maximum likelihood analysis, which placed each elephant shark sequence in a clade with the corresponding human MCR ortholog (10). In this regard, the detection of a putative elephant shark MC2R was of particular interest since previous studies on two species of elasmobranch sharks had not detected an MC2R ortholog in the genomes of these cartilaginous fishes (14, 15, 16). Maximum parsimony analysis of elephant shark MC2R, human MCRs, and zebrafish MCRs (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org) also placed the elephant shark MC2R in the same clade with human and zebrafish MC2R.

Fig. 1.

Maximum parsimony analysis of human, zebrafish, and elephant shark MCR. Maximum parsimony analysis was done using the branch and bound analysis algorithm (PAUP 4.3). The following sequences were aligned as described by Dores et al. (35): human, MC1R (AAD41355.1), MC2R (AA067714.1), MC3R (AA072726.1), MC4R (AA092061.1), and MC5R (NP_005904.1); zebrafish, MC1R (AA162848.1), MC2R (NP_775386.1), MC3R (AA024744.1), MC4R (AAL85494.1), and MC5R (NP_775386.1); and C. milii MC2R (FAA704.1). The sequence of Lampetra fluviatilis MCa receptor (lMCaR; ABB36647.1) was used as the outgroup. The bootstrap values in this figure were derived from 1000 replications.

A comparison of several gnathostome MC2R sequences (Supplemental Fig. 2) indicates that elephant shark MC2R has several features in common with the gnathostome MC2R including a short N-terminal domain with two N-linked glycosylation sites, a short C-terminal domain, and at least 50% primary sequence identity in transmembrane regions 6 and 7, intracellular loops 1 and 2, and extracellular loop 3. However, these sequence comparisons do not reveal whether elephant shark MC2R has the same pharmacological properties as teleost or tetrapod MC2 receptors. Working on the assumption that all vertebrate MC2R orthologs are MRAP1 dependent and can be activated only by ACTH but not by α-MSH, a V-5 epitope-tagged elephant shark mc2r cDNA was transiently transfected into a heterologous mammalian cell expression system [Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells] in the presence and absence of either mammalian or teleost MRAP1 orthologs or an elephant shark MRAP2 ortholog, and ligand selectivity analyses were done with either mammalian melanocortins or cartilaginous fish melanocortins. These experiments revealed that the elephant shark MC2R is an MRAP-independent MCR that can be activated by either ACTH or MSH-sized ligands with varying degrees of efficacy.

Materials and Methods

MC2R and MRAP constructs

Elephant shark (C. milii) MC2R (accession no. FAA704.1) and human MC2R (accession no. AA067714.1), were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) with an N-terminal V-5 epitope tag and inserted into a pcDNA3.1+ vector. Mouse (Mus musculus) MRAP1 (accession no. NM_029844), zebrafish (Danio rerio) MRAP1 (accession no. XR_117835), and elephant shark (C. milii) MRAP2, (accession no. BR000861) were individually synthesized by GenScript with an N-terminal FLAG epitope tag and were separately inserted into pcDNA3.1+ vectors.

Tissue culture

The experiments were done in transiently transfected CHO cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). The CHO cells were grown at 37 C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator in Kaighn's modification of Ham's F-12 (2 mm glutamine, 1500 mg/liter bicarbonate) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 ml normocin.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

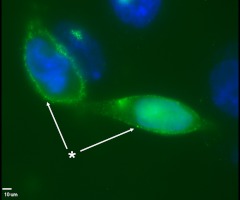

CHO cells were grown in two-well chamber slides (1 × 105 cells/well) for 24 h before transfection. The cells were transfected with 1 μg of elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Opti-MEM (Cellgro, Manassas, VA). After 24 h in culture, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and the immunofluorescence analysis was done on permeabilized and nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 2) as described previously (8). The primary antibody, a mouse monoclonal anti-V5 antibody, was diluted 1:100 in PBS + 1% BSA solution. The cells were incubated with the primary antibody for 1 h at 37 C. After a wash step, the cells were incubated with the secondary antibody, donkey antimouse antibody linked to Alexa-Fluor488 (1:400 in PBS + 1% BSA) for 45 min at 37 C to visualize MC2R immunofluorescence (Fig. 2, green). Coverslips were mounted onto slides using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Fig. 2, blue). The control for this experiment was the absence of immunofluorescence in permeabilized transfected cells following incubation with the V5-specific secondary antiserum only (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence detection of elephant shark MC2R expressed in CHO cells. In CHO cells the V5-tagged elephant shark MC2R was detected on the surface of nonpermeabilized CHO cells (white arrows; marked by the asterisk). Green, Elephant shark MC2R (Alexa-Fluor488); blue, nuclei (DAPI). Space bar, 10 μm.

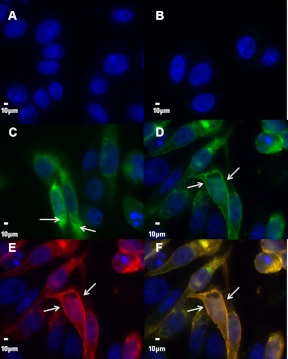

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence control experiments. A, To demonstrate the selectivity of the V5-specific secondary antibody, permeabilized elephant shark MC2R-transfected CHO cells were incubated with the secondary antiserum only, and no immunoflurescence was detected. B, To evaluate whether our clone of CHO cells express an endogenous MRAP, cells were transfected with a human V5-tagged mc2r cDNA alone and incubated with the V5 primary and secondary antibodies. For nonpermeabilized cells no immunofluorescence was observed on the plasma membrane. C, For permeabilized cells immunofluorescence was detected in subcellular compartments (white arrows). Hence, although the hmc2r construct was expressed in these CHO cells, human MC2R did not traffic to the plasma membrane. D, To demonstrate that exogenous MRAP can function in this clone of CHO cells, cells were cotransfected with V5-tagged hmc2R cDNA and a Flag-tagged mouse mrap1 cDNA, and nonpermeabilized cells were coincubated with the V5-specficic antibody and the Flag-specific antibody. Incubation with the V5-specific secondary antibody revealed human MC2R immunofluorescence (green) on the plasma membrane (white arrows). E, Incubation of these same cells with the Flag-specific secondary antibody revealed mMRAP1 immunofluorescence (red) on the plasma membrane (white arrows). F, Overlayering of images D and E provides evidence for the colocalization (yellow) of human MC2R and mMRAP1. Images B, D, E, and F were acquired with the same setting and are displayed on the same intensity scale. Images A and C are displayed on distinct intensity scales. For all panels, blue demonstrates nuclei (DAPI). Space bar, 10 μm.

To demonstrate that the clone of CHO cells used in this study lacks endogenous MRAP, cells were transfected with a human MC2R cDNA (1 μg) as described above, and immunofluorescence was done on nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 3B) and permeabilized cells (Fig. 3C). Finally, to demonstrate that exogenous MRAP can be functionally expressed in the clone of CHO cells used in this study, cells were cotransfected with a human MC2R cDNA (1 μg) and a mouse MRAP1 cDNA (1 μg) as described previously (8), and immunofluorescence was done on nonpermeablized cells (Fig. 3, D–F). Images were obtained using a ×100 oil immersion objective (Zeiss Plan-NEOFUAR; Carl Zeiss, New York, NY) with a fluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu digital camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) and a Sutter excitation filter wheel with Semrock filters (Sutter Instruments, Navato, CA). All images were analyzed using SlideBook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc, Denver, CO).

Functional expression assays

CHO cells were transfected with 2 μg each of elephant shark mc2r cDNA and cre-luc reporter plasmid (17) either with an mrap cDNA construct or in the absence of an mrap cDNA construct using a cell line nucleofector kit (Amaxa, Inc.; www.lonza.com) with solution T and program U-023. The cells were then plated on a white, 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. After 48 h in culture, the transfected cells were stimulated with melanocortin ligands in serum-free CHO media for 4 h at 37 C at concentrations ranging from 10−6 to 10−12 M. After the incubation period, 100 μl of Bright-Glo luciferase assay reagent (Promega Inc., Madison, WI) was applied to each well and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Luminescence was then measured with a Bio-Tek Synergy HT plate reader (Winooski, VT). The following ligands, all synthesized by New England Peptide (Boston, MA), were tested: human ACTH (1–24), [Nle4, d-Phe7] (NDP)-α-MSH, and the dogfish (S. acanthias) melanocortins: ACTH (1–25), α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH, and δ-MSH (18).

Data analysis

All experimental treatments were performed in no less than triplicate and then corrected for control values, which were obtained by using transfected cells that were left unstimulated. In each of the assays, maximal activation levels were between 3 and 10 times the control levels. The values in the luciferase assays were normalized to the average readings for cells treated with 1 μm human ACTH (1–24) (Figs. 4 and 5A and Supplemental Fig. 3) or 1 μm dogfish ACTH (1–25) (Fig. 5B). Average values and sem were graphed using KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, Reading, PA), and the EC50 value for each ligand was determined. The EC50 values were compared by using the Student's t test.

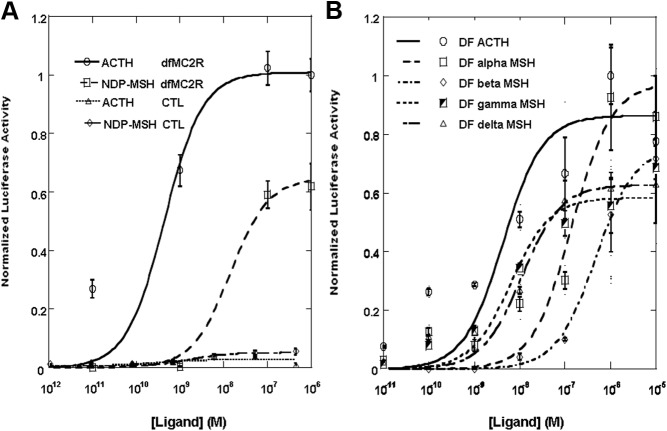

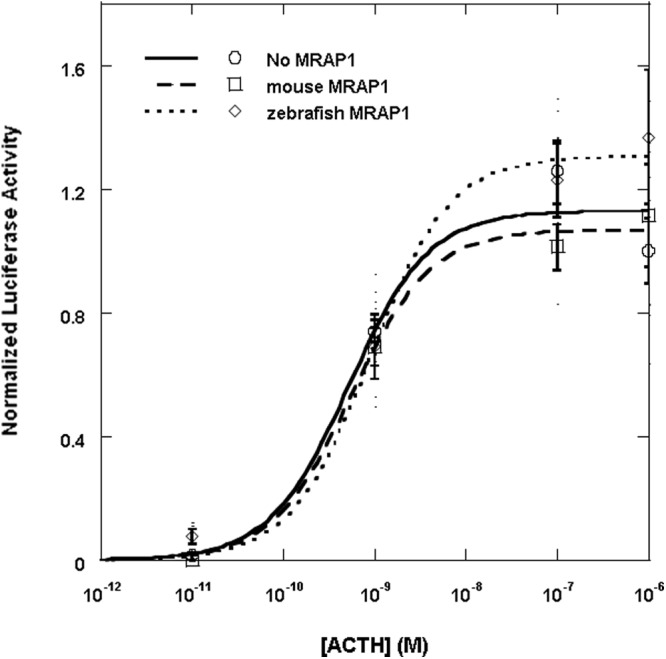

Fig. 4.

Coexpression of the elephant shark MC2R with MRAP1. CHO cells were transfected with either the elephant shark mc2 receptor cDNA construct and the cre/luc cDNA construct only (solid curve) or with the mouse mrap1 cDNA construct (dashed curve) or with the zebrafish mrap1 cDNA construct (dotted curve), and 2 d after the transfection, wells containing 1 × 105 cells were stimulated with human ACTH (1–24) at concentrations ranging from 10−5 to 10−12 m as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as mean ± sem (n = 4). The results were normalized to the average readings for cells treated with 1 μm human ACTH (1–24).

Fig. 5.

Ligand selectivity of the elephant shark MC2R. A, Functional expression of the elephant shark MC2R after stimulation with mammalian ligands. CHO cells were transfected with an elephant shark mc2 receptor cDNA construct and a cre/luc cDNA construct. Two days after the transfection, wells containing 1 × 105 cells were stimulated with either human ACTH (1–24) or NDP-α-MSH at concentrations ranging from 10−6 to 10−12 m as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction of nontransfected cells [control (CTL)] to these ligands is also shown. Results are expressed as mean ± sem (n = 3). The results were normalized to the average readings for cells treated with 1 μm human ACTH (1–24). B, Functional expression of the elephant shark MC2R after stimulation with dogfish melanocortins. CHO cells were transfected as described in A, and 2 d after the transfection, wells containing 1 × 105 cells were stimulated with dogfish ACTH (1–25), α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH, or δ-MSH at concentrations ranging from 10−5 to 10−11 m as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as mean ± sem (n = 3). The results were normalized to the average readings for cells treated with 1 μm dogfish ACTH (1–25).

Maximum parsimony analysis

Maximum parsimony analysis was done using the branch and bound analysis algorithm (PAUP 4.3). The following MCR amino acid sequences were analyzed: human MC1R (AAD41355.1), MC2R (AA067714.1), MC3R (AA072726.1), MC4R (AA092061.1), MC5R (NP_005904.1), and zebrafish MC1R (AA162848.1), MC2R (NP_775386.1), MC3R (AA024744.1), MC4R (AAL85494.1), and MC5R (NP_775386.1). The sequence of Lampetra fluviatilis MCaR (lamprey; ABB36647.1) was used as the outgroup. The bootstrap values in Fig. 1 were derived from 1000 replications.

Results

Immunofluorescence analysis of elephant shark MC2R expressed in CHO cells

To determine the parameters for expressing elephant shark MC2R in CHO cells, the V5-labeled elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct was transfected into CHO cells and V5 immunofluorescence was detected in permeabilized cells (data not shown). We also checked for V5 immunofluorescence in wells in which the transfected cells were not permeabilized. The operating assumption was that no immunofluorescence would be detected on the surface of the nonpermeabilized transfected CHO cells. However, as indicated in Fig. 2, V5 immunofluorescence was detected on the surface of the transfected CHO cells. Because CHO cells do not express an endogenous mrap gene (19), and no exogenous mrap cDNA was cotransfected with the elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct, it appears that the trafficking of the elephant shark MC2 receptor from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane does not involve interaction with an MRAP. As an indication of the specificity of the V5 secondary antiserum, no immunofluorescence was detected when elephant shark MC2R-transfected CHO cells were incubated with the V5-specific secondary antibody alone (Fig. 3A). To demonstrate that our clone of CHO cells does not express endogenous mrap genes, cells were transfected with a human mc2r cDNA, and no immunofluorescence was detected on the surface of nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 3B). However, immunofluorescence was detected in permeabilized cells, which indicated that the hmc2r cDNA was expressed (Fig. 3C). Finally, to demonstrate that exogenous MRAP can be functionally expressed in our clone of CHO cells, cells were cotransfected with a hmc2r cDNA and a mouse mrap1 cDNA. This experiment indicated that colocalization of the immunoreactive human MC2R and the mouse MRAP1 was apparent on the plasma membrane of nonpermeabilized cells (Fig. 3, D–F).

Coexpression of elephant shark MC2R with MRAP cDNA constructs

To determine whether coexpression with MRAP1 would affect the activation of elephant shark MC2R, CHO cells were first cotransfected with an elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct and either a mouse mrap1 (mMRAP1) cDNA construct or a zebrafish mrap1 (zfMRAP1) cDNA construct (Fig. 4). The mouse and zebrafish MRAP1 were used in this experiment due to the fact that a MRAP1 ortholog has not been found in the elephant shark genome database (10), yet mMRAP1 and zfMRAP can be used for functional activation of teleost MC2R (6, 8). The transfected cells were stimulated with human ACTH (1–24) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Note that coexpression of elephant shark MC2R with either MRAP1 cDNA had no effect, either positive or negative, on activation. In this experiment the EC50 value for elephant shark MC2R expressed alone was 5.2 ± 1.0 × 10−10 m, and in presence of mMRAP1 or zfMRAP1 the EC50 values were 5.6 ± 1.1 × 10−10 m and 8.9 ± 1.9 × 10−10 m, respectively. CHO cells were also cotransfected with the elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct and an elephant shark mrap2 cDNA construct and stimulated with human ACTH (1–24) (Supplemental Fig. 3). However, the presence of the elephant shark MRAP2 had no effect, either positive or negative, on the EC50 value.

Ligand selectivity of elephant shark MC2R

In a subsequent experiment, CHO cells were cotransfected with the elephant shark mc2r cDNA construct and stimulated with either human ACTH (1–24) or NDP-MSH. The operating assumption was that NDP-MSH would have no effect on the elephant shark MC2R ortholog. However, NDP-MSH activated the elephant shark MC2R in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). The EC50 value for the human ACTH (1–24)-stimulated cells was 6.3 ± 2.5 × 10−10 m, and the EC50 value for the NDP-MSH-stimulated cells was 1.3 ± 0.6 × 10−7 m. Although human ACTH (1–24) was clearly the more potent ligand (P < 0.05), it is unprecedented for a MC2R ortholog to have any sensitivity for an MSH-sized ligand.

The potency of various cartilaginous fish melanocortins was also tested on CHO cells transfected with elephant shark MC2R. For this experiment the S. acanthias (dogfish) melanocortins ACTH (1–25), α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH, and δ-MSH (18) were tested at concentrations ranging from 10−5 to 10−11 m (Fig. 5B). The EC50 values for the dogfish melanocortins were as follows: ACTH (1–25), 4.3 ± 1.4 × 10−9 m; γ-MSH, 6.3 ± 1.8 × 10−9 m; δ-MSH, 1.1 ± 0.2 × 10−8 m; α-MSH, 1.4 ± 0.5 × 10−7 m; and β-MSH, 4.7 ± 1.4 × 10−7 m. Although the EC50 values for ACTH (1–25), γ-MSH, and δ-MSH were not statistically different, ACTH (1–25) was clearly a more potent ligand than either α-MSH or β-MSH (P < 0.01). The order of sensitivity for the dogfish melanocortins was ACTH (1–25) = γ-MSH = δ-MSH > αMSH = β-MSH.

Discussion

The distribution of melanocortin receptor paralogs and a MRAP2 paralog in extant cartilaginous fishes presents a number of unresolved questions. The model for the evolution and radiation of melanocortin receptor paralogs predicts that five MCR genes may have been present in the ancestral gnathostomes (10). Among the extant groups of gnathostomes (i.e. cartilaginous fishes, ray finned fishes, lobe finned fishes, and tetrapods), the presence of five MCR paralogs within individual species in each group has been confirmed with the exception of the cartilaginous fishes. Among these gnathostomes, cDNA were cloned from the genome of the elasmobranch, S. acanthias, which corresponded only to orthologs of MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R, respectively, (14, 15), whereas, an in silico analysis of the genome of the holocephalan, C. milii (elephant shark), revealed only the presence of orthologs of MC1R, MC2R, and MC3R, respectively. If in fact the ancestral gnathostomes had five paralogous MCR genes, then it would appear that gene loss has played a significant role in the selection of MCR paralogs in extant cartilaginous fishes.

Previous studies on the elasmobranch (sharks and rays) MCR (i.e. MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R) indicated that ACTH is more potent than any of the elasmobranch MSH (i.e. α-MSH, β-MSH, γ-MSH, and δ-MSH,) at activating these receptors (20, 21). It is known that corticotropic cells of the anterior pituitary of elasmobranches express the pomc gene, and these cells synthesize ACTH (18, 22). It is also known that melanotropic cells of the intermediate pituitary of elasmobranches also express the pomc gene yet make the various MSHs (18, 23). Because elasmobranch MCR can be activated by either ACTH or the MSH, the mechanism for regulating the production of glucocorticoids by the interrenal glands of sharks and rays appears to be more complex than in the bony vertebrates. The receptor on the elasmobranch interrenal gland responsible for initiating glucocorticoid synthesis has not been identified. However, based on the current possibilities (i.e. MC3R, MC4R, or MC5R), activation of interrenal (HPA/I) cells cannot be regulated by a single melanocortin as seen in hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal /hypothalamus-pituitary-interrenal axes of teleosts and tetrapods (3, 6, 24). Because agouti gene-related peptide (AGRP) have been detected in the genome of at least one cartilaginous fish (10), perhaps these polypeptides play a role in regulating glucocorticoid synthesis. Alternatively, another polypeptide/G protein-coupled receptor combination may regulate glucocorticoid synthesis in elasmobranches. In this regard, a recent study on an angiotensin II receptor expressed by stingray head kidney cells (interrenal tissue) is relevant (25). Activation of this receptor will result in glucocorticoid production. It would appear that multiple mechanisms may be present on elasmobranch interrenal cells to regulate the production of glucocorticoids. However, studies to delineate these mechanisms have not been done.

The current study has focused on the pharmacological properties of an MC2R ortholog in the genome of the holocephalan cartilaginous fish, C. milii. The identity of this receptor as a MC2R ortholog was based on a maximum likelihood analysis (10) and was supported by maximum parsimony analysis of a similar data set of MCR amino acid sequences (Fig. 1). However, the elephant shark MC2R ortholog has properties that are very different from either teleost or tetrapod MC2R orthologs. Immunofluorescence analyses and functional expression assays done in CHO cells indicated that the elephant shark MC2 receptor does not require MRAP for either trafficking to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2) or functional activation by human ACTH (1–24) (Fig. 4). Indeed, cotransfection with teleost or tetrapod MRAP1 or an elephant shark MRAP2 ortholog had no effect, either positive or negative, on the functional activation of the receptor (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 3). Although these data do not reveal a function for the elephant shark MRAP2 ortholog, collectively these results indicate that the elephant shark MC2 receptor is an MRAP-independent MC2R ortholog.

This conclusion is not unprecedented. As presented in the introductory text, the working hypothesis for the evolution of the melanocortin receptor gene family (9, 10) is that the ancestral melanocortin gene emerged in an ancestral, and now extinct, protochordate lineage. Following the first chordate genome duplication event (1R), two paralogous MCR-like genes are predicted to have been present in the ancestral agnathans, and following the second chordate genome duplication event (2R), four paralogous melanocortin receptor genes are predicted to have been present in the ancestral gnathostomes. A local gene duplication of one of the paralogous melanocortin receptor genes in the ancestral gnathostome genome is predicted to account for the presence of a fifth paralogous melanocortin receptor gene in the stem gnathostome classes (i.e. the cartilaginous fishes, the ray finned fishes, and the lobe finned fishes and tetrapods) (10). In support of this hypothesis, two paralogous MCR cDNA (MCa and MCb) have been characterized from the lamprey genome (26). Phylogenetic analyses indicate that MCa is a MC1R ortholog and MCb is a MC4R ortholog. The lamprey MCa receptor has been functionally expressed in human embryonic kidney-293 EBNA cells without the need for cotransfection with an exogenous mrap cDNA. Note that no MC2R orthologous gene has been detected in the lamprey genome.

With respect to the other cartilaginous fish melanocortin receptors (i.e. dogfish MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R), all of these receptors can be functionally expressed in heterologous mammalian cells without cotransfection with an exogenous mrap cDNA (14, 15, 21). When all these observations are taken collectively, two hypotheses emerge: 1) the MC2R gene most likely originated with the ancestral gnathostomes before the radiation of the three stem classes of gnathostomes; and 2) melanocortin receptors in agnathans and in the ancestral gnathostomes were MRAP independent. Based on these hypotheses, we predict that the MRAP-independent nature of the elephant shark MC2R was an ancestral feature rather than a derived trait.

Based on these assumptions, it would appear that dependence on MRAP for trafficking to the plasma membrane and for functional activation of the MC2 receptor must have evolved after the divergence of the ancestral cartilaginous fishes and the ancestral bony fishes. Current understanding of the dependence of the MC2R on MRAP indicates that a complex forms between two MRAP homodimers and a MC2R homodimer (27). Although the MC2R-trafficking motif and functional activation motif on MRAP1 have been identified (28, 29), the corresponding contact site on the MC2 receptor for interaction with MRAP has not been determined for either teleost or tetrapod MC2R.

Another major difference between elephant shark MC2R and teleost and tetrapod MC2R is with respect to ligand selectivity. There is an extensive literature on the exclusive selectivity of the adrenal cortex (i.e. MC2R) receptor for ACTH and the inability of α-MSH to activate this receptor (30) or even to act as a competitive inhibitor of ACTH binding to the receptor (31). Although ACTH (1–24) was a more potent stimulator of elephant shark MC2R than any of the MSH that were tested, the fact remains that the receptor could be activated by NDP-MSH or the dogfish fish MSH in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5, A and B). A similar preference for ACTH-sized ligands compared with MSH-sized ligands has been observed for the lamprey melanocortin-a (MCa) receptor (26), and the S. acanthias (dogfish) MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R (14, 15, 21).

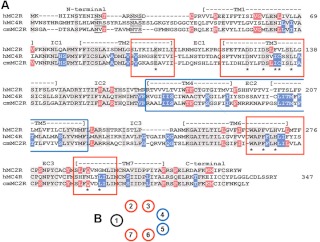

Clearly the HFRW binding site on the elephant shark MC2R can accommodate either ACTH or the MSH. This is a feature that has been observed for teleost and tetrapod MC1R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R but not for a teleost or tetrapod MC2R ortholog. Some understanding of the ligand selectivity of the elephant shark MC2 receptor ortholog relative to the teleost and tetrapod MC2R orthologs may be apparent from a comparison of the amino acid sequences of human MC2R, human MC4R, and elephant shark MC2R (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Alignment of human MC2R, human MC4R, and elephant shark MC2R. A, The amino acid sequences for human MC2R, human MC4R, and elephant shark MC2R were aligned as described in the legend to Supplemental Fig. 1. Amino acid positions that were identical in all three sequences were shaded in gray. Amino acid positions that were found only in the human MC2R and elephant shark MC2R are shaded in red. Amino acid positions that are only found in the human MC4R and elephant shark MC2R are shaded in blue. The position of the amino acids required for the HFRW binding site of human MC4R (33) are marked with an asterisk. The portions of TM2, TM3, TM6, and TM7 that form the HFRW binding site on the human MC4R are in the red boxes for emphasis. TM4, EC2, and TM5 were placed in the box with the blue boundaries for emphasis. B, Cartoon representation of MC2R. The TM of MC2R are arranged in a barrel configuration. The site of the HRWR binding site is marked by the TM regions with a red border. The TM regions that could constitute the proposed location of the K/RKRR binding site are marked with a blue boundary.

The mammalian and cartilaginous fish lineages last shared a common ancestor well over 400 million years ago (32); hence, it would be assumed that the number of identical positions in the human MCR sequences relative to the elephant shark MC2R sequence would be few. In fact, only 33% of the amino acid positions in this alignment are identical in all three sequences (Fig. 5A, residues shaded gray). As indicated by the red-shaded amino acid positions, an additional 24 positions are identical in the human and elephant shark MC2R orthologs. However, there are 29 positions (shaded blue; Fig. 6A) that are identical for human MC4R and elephant shark MC2R. Clearly these positions did not influence the positioning of the elephant shark MC2R in the maximum parsimony analysis (Fig. 1) but may play a role in ligand selectivity. There are some unexpected similarities between human MC4R and elephant shark MC2R that are worth noting.

All melanocortin receptors have a binding site to accommodate the HFRW motif of the melanocortin ligands (for review see Ref. 3). Pogozheva et al. (33) used a computer-modeling strategy and a site-directed mutagenesis paradigm to identify 11 critical amino acids in human MC4R that form the HFRW binding site. These residues are marked with a star in Fig. 6A. Note that the human MC2R sequence has eight of these conserved amino acid positions. However, the elephant shark MC2R sequence has 10 of these conserved amino acid positions. The additional conserved amino acid positions are found in transmembrane region 3 at residues I132 and C133. These two residues are also present at the same position in nearly every MC1R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R that has been characterized (16), including the two lamprey melanocortin receptor paralogs (26). Hence, it would be reasonable to assume that residues in transmembrane (TM) 2, TM3, TM6, and TM7 were also present in the ancestral vertebrate MCR. However, these two amino acid positions are not found in MC2R orthologs (Supplemental Fig. 2). Furthermore, ACTH binding to a teleost or tetrapod MC2R ortholog also requires accommodation of the K/RKRR motif (29), which is present in the ACTH sequence of gnathostomes (34).

Assuming that the transmembrane regions of melanocortin receptors are oriented as shown in Fig. 6B to form the HFRW binding site, then the likely site for the K/RKRR binding site would be in the TM4, extracellular loop 2 (EC2), or TM5 portion of the receptor. In these regions of the receptor (Fig. 6A, blue box), it appears that the elephant shark MC2R is more MC4R-like than MC2R-like. Amino acid substitutions in the TM4/EC2/TM5 during the early radiation of ancestral bony fishes could have altered the three dimensional shape of the receptor to create the K/RKRR binding site. Thus, studies on some of the older lineages of the bony fishes may shed light on these changes. However, the ability of the teleost and tetrapod MC2 orthologs to exclude the MSH indicates that these receptors must have a more dynamic activation mechanism, which involves a confirmation change when the appropriate ligand (i.e. ACTH) makes contact with the receptor. In this regard, characterization of the K/RKRR binding on MC2R orthologs will be important in deciphering the mechanism of activation.

Although the phylogenetic analyses indicate that the elephant shark MC2R is orthologous to the teleost and tetrapod MC2R, from a functional perspective, elephant shark MC2R has properties that are distinct from these bony vertebrate MC2R orthologs. It would appear that after the divergence of the ancestral cartilaginous fishes and the ancestral bony fishes, significant changes occurred to the ancestral bony fish MC2R ortholog, which have influenced the regulation of interrenal cells and adrenal cortex cells in teleosts and tetrapods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Lorenzon for her assistance with the immunofluorescence analysis. The mouse MRAP1 cDNA construct was provided by Dr. Patricia Hinkle (Rochester University, Rochester, NY).

This work was supported by Grant IOB 0516958 from the National Science Foundation (to R.M.D.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- DAPI

- 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole

- EC2

- extracellular loop 2

- MCR

- melanocortin receptor

- MC2R

- melanocortin-2 receptor

- mMRAP1

- mouse mrap1

- MRAP1

- MC2R accessory protein 1

- NDP

- [Nle4, d-Phe7]

- TM

- transmembrane domain

- zfMRAP1

- zebrafish mrap1.

References

- 1. Hinkle PM, Sebag JA. 2009. Structure and function of the melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol 300:25–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Webb TR, Clark AJL. 2010. Minireview: the melanocortin 2 receptor accessory proteins. Mol Endocrinol 24:475–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cone RD. 2006. Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocr Rev 27:736–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Cone RD. 1992. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science 257:1248–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kapas S, Cammas FM, Hinson JP, Clark AJL. 1996. Agonist and receptor binding properties of adrenocorticotropin peptides using the cloned mouse adrenocorticotropin receptor expressed in a stably transfected HeLa cell line. Endocrinology 137:3291–3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agulleiro MJ, Roy S, Sánchez E, Puchol S, Gallo-Payet N, Cerdá-Reverter JM. 2010. Role of melanocortin receptor accessory proteins in the function of zebrafish melanocortin receptor type 2. Mol Cell Endocrinol 320:145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aluru N, Vijayan MM. 2008. Molecular characterization, tissue-specific expression, and regulation of melanocortin 2 receptor in rainbow trout. Endocrinology 149:4577–4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liang L, Sebag JA, Eagelston L, Serasinghe MN, Veo K, Reinick C, Angleson J, Hinkle PM, Dores RM. 2011. Functional expression of frog and rainbow trout melanocortin 2 receptors using heterologous MRAP1s. Gen Comp Endocrinol 174:5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schiöth HB, Haitina T, Ling MK, Ringholm A, Fredriksson R, Cerdá-Reverter JM, Klovins J. 2005. Evolutionary conservation of the structural, pharmacological, and genomic characteristics of the melanocortin receptor subtypes. Peptides 26:1886–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vastermark A, Schiöth HB. 2011. The early origin of melanocortin receptors, agouti-related peptides, agouti signaling peptide, and melanocortin receptor accessory proteins with emphasis on pufferfishes, elephant shark, lampreys, and amphioxus. Eur J Pharmacol 660:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klovins J, Haitina T, Fridmanis D, Kilianova Z, Kapa I, Fredriksson R, Gallo-Payet N, Schiöth HB. 2004. The melanocortin system in Fugu: Determination of POMC/AGRP/MCR gene repertoire and synteny, as well as pharmacology and anatomical distribution of the MCRs. Mol Biol Evol 21:563–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ringholm A, Fredriksson R, Poliakova N, Yan YL, Postlethwait JH, Larhammar D, Schiöth HB. 2002. One melanocortin 4 and two melanocortin 5 receptors from zebrafish show remarkable conservation in structure and pharmacology. J Neurochem 82:6–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson JS. 1994. Fishes of the world. 3rd ed New York: John Wiley, Sons Press [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ringholm A, Klovins J, Fredriksson R, Poliakova N, Larson ET, Kukkonen JP, Larhammar D, Schiöth HB. 2003. Presence of melanocortin (MC4) receptor in spiny dogfish suggests an ancient vertebrate origin of central melanocortin system. Eur J Biochem 270:213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klovins J, Haitina T, Ringholm A, Löwgren M, Fridmanis D, Slaidina M, Stier S, Schiöth HB. 2004. Cloning of two melanocortin (MC) receptors in spiny dogfish. Eur J Biochem 271:4320–4331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baron A, Veo K, Angleson J, Dores RM. 2009. Modeling the evolution of the MC2R and MC5R genes: studies on the cartilaginous fish, Heterondotus francisci. Gen Comp Endocrinol 161:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chepurny OG, Holz GG. 2007. A novel cyclic adenosine monophosphate responsive luciferase reporter incorporating a nonpalindromic cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element provides optimal performance for use in G protein coupled receptor drug discovery efforts. J Biomol Screen 12:740–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amemiya Y, Takahashi A, Suzuki N, Sasayama Y, Kawachi H. 1999. A newly characterized melanotropin in proopiomelanocortin in pituitaries of an elasmobranch, Squalus acanthias. Gen Comp Endocrinol 114:387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sebag JA, Hinkle PM. 2007. Melanocortin-2 receptor accessory protein MRAP forms antiparallel homodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:20244–20249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haitina T, Takahashi A, Holméén L, Enberg J, Schiöth HB. 2007. Further evidence for ancient role of ACTH peptides at melanocortin (MC) receptors; pharmacology of dogfish and lamprey peptides at dogfish MC receptors. Peptides 28:798–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reinick CL, Liang L, Angleson JK, Dores RM. 2012. Functional expression of Squalus acanthias melanocortin 5 receptor in CHO cells, ligand selectivity and interaction with MRAP. Eur J Pharmacol 680:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lowry PJ, Bennett HP, McMartin C. 1974. The isolation and amino acid sequence of an adrenocorticotrophin from the pars distalis and a corticotrophin-like intermediate-lobe peptide from the neurointermediate lobe of the pituitary of the dogfish, Squalus acanthias. Biochem J 141:427–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lowry PJ, Chadwick A. 1970. Purification and amino acid sequence of melanocyte-stimulating hormone from the dogfish, Squalus acanthias. Biochem J 118:713–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gantz I, Fong TM. 2003. The melanocortin system. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E468–E474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans AN, Rimoldi JM, Gadepalli SV, Nunez BS. 2010. Adaptation of a corticosterone ELISA to demonstrate sequence-specific effects of angiotensin II peptides and C-type natriuretic peptide on 1 α-hydroxycorticosterone synthesis and steroidogenic mRNAs in the elasmobranch interrenal glad. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 120:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haitina T, Klovins J, Takahashi A, Löwgren M, Ringholm A, Enberg J, Kawauchi H, Larson ET, Fredriksson R, Schiöth HB. 2007. Functional characterization of two melanocortin (MC) receptors in lamprey showing orthology to the MC1 and MC4 receptor subtypes. BMC Evol Biol 7:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cooray SN, Chung TT, Mazhar K, Szidonya L, Clark AJ. 2011. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer reveals the adrenocorticotropin (ACTH)-induced conformational change of the activated ACTH receptor complex in living cells. Endocrinology 152:495–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sebag JA, Hinkle PM. 2009. Regions of melanocortin w (MC2) receptor accessory protein necessary for duel topology and MC2 receptor trafficking and signaling. J Biol Chem 284:610–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Webb TR, Chan L, Cooray SN, Cheetham ME, Chapple JP, Clark AJ. 2009. Distinct melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein domains are required for melanocortin 2 receptor interaction and promotion of receptor trafficking. Endocrinology 150:720–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schwyzer R. 1977. ACTH: a short introductory review. Ann NY Acad Sci 297:3–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buckley DI, Yamashiro D, Ramachandran J. 1981. Synthesis of a corticotropin analogue that retains full biological activity after iodination. Endocrinology 109:5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carroll RL. 1988. Vertebrate paleontology and evolution. New York: W. H. Freeman [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pogozheva ID, Chai BX, Lomize AL, Fong TM, Weinberg DH, Nargund RP, Mulholland MW, Grantz I, Mosberg HI. 2005. Interactions of human melanocortin 4 receptors with nonpeptide and peptide agonists. Biochemistry 44:11329–11341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dores RM, Lecaude S. 2005. Trends in the evolution of the proopiomelanocortin gene. Gen Comp Endocrinol 142:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dores RM, Rubin DA, Quinn TW. 1996. Minireview: is it possible to construct phylogenetic trees using polypeptide hormone sequences. Gen Comp Endocrinol 103:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.