Abstract

Mammary organoids from adult mice produce tubules, analogous to mammary ducts in vivo, in response to hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) when cultured in collagen gels. The combination of HGF plus progestin (R5020) causes reduced tubule number and length. We hypothesized that the inhibitory effect on tubulogenesis was due to progestin-mediated alteration of HGF/c-Met signaling. Using molecular inhibitors and short hairpin RNA, it was determined that HGF activation of Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac1) was required for the formation of cytoplasmic extensions, the first step of tubulogenesis, and that Rac1 activity was Src kinase (Src) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) dependent. The highly novel finding was that R5020 reduced tubulogenesis by up-regulating and increasing extracellular laminin and α6-integrin ligation to reduce activation of the Src, focal adhesion kinase, and Rac1 pathway. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, another progesterone-induced paracrine factor, did not replicate this effect of R5020. The inhibitory effect of R5020 on tubulogenesis was likely mediated through progesterone receptor (PR) isoform A (PRA), because PRA is the predominant PR isoform expressed in the organoids, and the progestin-induced effect was prevented by the PR antagonist RU486. These results provide a plausible mechanism that explains progestin/PRA-mediated blunting of HGF-induced tubulogenesis in vitro and is proposed to be relevant to progesterone/PRA-induced side-branching in vivo during pregnancy.

Before pregnancy, the mouse mammary gland consists of a system of simple branched ducts. With the onset of pregnancy, progesterone plays a key role in the development of short side branches off larger ducts that provide the platform for the lobuloalveolar development required for lactation. Alveologenesis and lactational differentiation are mainly driven by progesterone during pregnancy (1, 2). Through the use of transgenic overexpressing and gene deletion mouse models of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and wingless-type MMTV integration site 4 (Wnt-4), these two progesterone-induced paracrine factors have both been implicated in mammary gland side branching and alveologenesis (3, 4). These paracrine factors have been shown to have roles in mediating cell proliferation (5, 6) and stem cell renewal and cell fate determination (7, 8). However, the underlying mechanisms specific to progesterone-mediated side branch development have not been well defined. The initial step in alveologenesis and lactational differentiation is the formation of side branches, i.e. shortened ducts. Thus, it was of interest to determine how progesterone might mediate this early effect in the alveologenic process. Alveologenesis can be viewed as a transition from the predominance of ductal development to the production of highly differentiated alveolar cells; inherent in this process is the apparent attenuation of ductal elongation. Thus, although progesterone action is key to the proliferative expansion of alveolar epithelial cells, it appears that it also has the effect to produce short side branches, which suggests it attenuates ductal elongation.

In vitro mammary ductal development can be recapitulated using a three-dimensional (3D) collagen I (Col I) gel culture model. This collagen gel culture model has been used extensively to study lung (9), salivary gland (10), and kidney (11) tubule development and mammary ductal development (12–14). Estrogen and progesterone receptors (PR) are well maintained in mammary organoids, and this culture model has proven useful to study steroid hormone action in mammary organoids (15). Estrogen alone or combined with progestin does not have an effect on proliferation or morphological changes (14). However, we and others have shown that primary mammary organoids composed of luminal epithelial cells (LEC) and myoepithelial cells (MEC) treated with growth factors, particularly hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) an estrogen-induced fibroblast-derived paracrine growth factor (14), develop tubules that resemble mammary ducts in vivo (12–14). In this culture model, we have defined the morphological steps during tubulogenesis (15). First, LEC send out cytoplasmic extensions into the matrix. As LEC proliferate, a single-layer chain of cells invades further, and then epithelial cells undergo a redifferentiation stage where they form bilayered cords of cells and finally mature tubules with patent lumens. MEC follow the leading LEC in this process. Notably, HGF-induced tubulogenesis is modulated by the addition of a synthetic progestin, R5020, resulting in shorter tubules (13, 15). No extensions or tubules are formed in response to treatment with progestin alone, but instead, progestin-alone treatment causes central lumen formation within the body of the organoid by topographically localized apoptosis (13, 15). The observed R5020-induced shortening of tubules induced by HGF has led us to hypothesize that this progestin-mediated effect in vitro is analogous to progesterone-mediated side branching in vivo. Thus, the present studies were undertaken to identify the mechanisms by which progestin mediates tubule shortening.

It has previously been shown that Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) contributes to actin protrusions at the leading edge of migrating cells and is implicated in the early steps of in vitro tubulogenesis (cytoplasmic extension and chain formation) in other cell culture models (16–20). A number of pathways acting upstream of Rac1 in tubulogenesis and cell migration have been identified for MDCK cells including MAPK (21), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (22, 23), Src kinase (Src) (24, 25), and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (19). The HGF signaling pathway regulating tubule formation in mammary organoids is not known, nor is the effect of R5020 on HGF signaling to produce tubule shortening. Thus, the present studies were undertaken to identify the signaling pathways downstream of HGF that mediate tubulogenesis in mammary organoids and the mechanisms of R5020-mediated blunting of tubulogenesis as an in vitro model that could provide novel insights into progesterone-induced in vivo side branching during pregnancy.

Our studies show that HGF initiates tubulogenesis by producing cytoplasmic extensions, the first step in tubule formation, by a Rac1 pathway that is downstream of Src and FAK activity. Furthermore, our studies show that progestin mediates tubule shortening through a previously unidentified and novel mechanism whereby progesterone-induced Lm-5 activates α6-integrin signaling to reduce Rac1 activation. We propose that this is the mechanism responsible for R5020 blunting of HGF-induce tubulogenesis of mammary organoids.

Materials and Methods

Animals

BALB/c virgin adult females (16–24 wk old) were used as the source of mammary gland tissue for primary cell culture. Animal use was in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care and approved by the All University Committee on Animal Use and Care at Michigan State University.

Three-dimensional collagen cultures

For 3D collagen cultures, primary mouse mammary epithelial organoids were isolated as previously published (15). Cultures were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 96-well plates in Col I gels (2 mg/ml, underlayment of 40 μl/well, and cells plated in 75 μl/well; rat tail collagen; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) or in growth factor-depleted Matrigel (100%, underlayment of 40 μl/well, and cells plated in 75 μl/well; BD Biosciences) as previously described (14). The preparation of gels was according to manufacturer's instructions. The gels (Col I and Matrigel) remained attached throughout the culture time. All experiments, except where specified, were carried out in Col I gels. Cultures were maintained in basal medium (BM) [serum- and phenol red-free DMEM/F12 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 100 ng/ml human recombinant insulin, 1 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA (fraction V), 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin] with or without or in various combinations of HGF (50 ng/ml; Sigma), promogestone (20 nm R5020 synthetic progestin; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA), mifepristone (100 nm RU486; Sigma), and 20 nm RANKL (200 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The synthetic progestin R5020 was used for culture studies because it is more stable and less rapidly metabolized than progesterone (13).

For inhibitor studies, organoids were pretreated with inhibitors 30 min before plating. Organoids were treated with 10 μm FAK inhibitor-14 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO), 20 μm pp60-c Src inhibitor 2 (PP2) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), 10 μm PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Cell Signaling Technology), or 10 μm MAPK kinase (MEK) inhibitor U0126 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Monolayer cell culture

Six-well plates were precoated with 50 μg/ml Col I or Laminin 1 (Lm-1) (BD Biosciences) before plating of cells. Isolated primary mammary epithelial organoids were plated as a monolayer with 4 × 106 cells per well allowed to attach 48 h in BM. Organoids were then cultured in BM or HGF and harvested after 4 h of treatment.

Knockdown of proteins by adenovirally delivered short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

Adenovirus carrying both a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression cassette and shRNA sequences targeting Rac1, Lm-5 (γ2-subunit), or scramble sequences were generated. Freshly isolated organoids were infected in BM suspension with adenovirus carrying GFP cassette [multiplicity of infection (MOI) 50 or 100], Rac1 shRNA (MOI 50), Lmγ2 shRNA (MOI 100), or scramble (MOI 50 or 100) for 3.5 h at 37 C. Infected organoids were centrifuged, and the viral supernatant was removed. Organoids were washed and resuspended in BM, plated in collagen gel, and maintained in BM 24–48 h before treatment. To determine infectivity, GFP expression was analyzed using a Nikon inverted epifluorescence scope (Mager Scientific, Dexter, MI) 24 h after infection, and 80–90% infection was obtained.

RT-PCR

Effect of knockdown of Lmγ2 expression was determined by RT-PCR. Organoids were infected with scramble control or Lmγ2 shRNA and maintained in BM for 24 h and then treated with HGF or HGF plus R5020 (HGF+R5020). Twenty-four hours later, gels were removed and RNA was extracted using the Trizol method, described previously (26). cDNA was prepared from isolated RNA using random hexamer primers from RT2 First Strand Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A 7500 FAST RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) was used for RT-PCR. Gene expression assays were performed in triplicate with RT2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (QIAGEN) and prevalidated primers for Lmγ2 (LAMC2) and GAPDH. The expression values were normalized to GAPDH and the comparative cycle threshold method was used to determine the change in gene expression.

Morphometrics

Phase-contrast images were captured with a 20× lens using a Nikon TMS-F inverted scope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a Q imaging Micropublishing version 5.0 RTV camera and Qcapture pro software (QImaging Corp., Surrey, British Columbia, Canada). Images were analyzed for extension, chain, and tubule number per organoid with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Our previous studies using confocal microscopy defined the appearance of extension, chain, chord, and tubules (15) that formed the basis for the identification of the same structures in phase-contrast images. The width and length of projections were used to classify structures into extensions, chains, and tubes. Pixel width was measured to classify structures first. Anything that was less than 25 pixels wide was considered a single-cell-layered structure (an extension or chain). If the measurement was over 25 pixels, it was considered a multicell-layered structure (cord or tube). Length was then used to classify structures further. Anything over 45 pixels long was considered a chain, cord, or tube. Because phase-contrast imaging is limited, lumens cannot be seen to distinguish the difference between cords and tubules. For this reason, cords and tubes were grouped together. In the α6-integrin blocking antibody experiments, structures longer than the average tubule length (≥140 pixels) were considered long tubules. For shRNA cultures, images of organoids expressing 80–90% GFP were captured using a Nikon inverted epifluorescence scope with 10× lens (Mager Scientific, Dexter, MI) and analyzed with MetaMorph software. For Lmγ2 shRNA experiments, structures longer than the average tubule length (≥50 pixels) were considered long tubules. The results are reported as the mean ± sem, and differences are significant at P < 0.05 with ANOVA.

Rac1-GTP assay

Rac1-GTP assays were performed following a modified method from Yamazaki et al. (27). Cultures were plated in collagen gels at a density of 1.4 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates. Collagen gels containing organoids were homogenized in Rac1 lysis buffer [50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, protease inhibitor cocktail; Sigma]. Cleared lysates were used for Rac1-GTP pull-down assays using Rac/Cdc42 (p21) binding domain (PBD) of the human p21 activated kinase 1 protein (PAK) (PAK-PBD) protein agarose beads (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) according to the manufacturer's recommendation.

Immunoblotting

All immunoblots were prepared for scanning using a Li-Cor Odyssey (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) platform according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Protein supernatants were used for immunoblotting using the following antibodies: anti-Rac1, clone 23A8 antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:1000 dilution), phospho-protein kinase B 1/2/3 (pAkt 1/2/3) (Ser 473, 1:200 dilution), PI3K p85α (B9, 1:500 dilution), phospho-Erk (E-4, 1:200 dilution), Erk1/2 (C-16, 1:1000 dilution), Lmγ2 (c-20, 1:200 dilution), and FAK (A-17, 1:1000 dilution) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. The phospho-FAK (pY397, 1:1000 dilution) antibody was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The phospho-Src (Y416, 1:200 dilution) and Src (1:1000 dilution) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. For phospho-FAK, FAK protein was immunoprecipitated and an immunoblot was performed to detect phospho-FAK. IRDye 680 or IRDye 800 secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences) against mouse, rabbit, or goat were used at 1:5000 dilutions. Erk1/2 was used as a loading control for all immunoblots because actin levels changed with treatments. Densitometric measurements of protein bands were assessed using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Antibody labeling of organoids

The procedure for antibody labeling of organoids in collagen gels was previously described (15). Gels containing fixed organoids were labeled with the goat polyclonal Lmγ2 antibody (1:200) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against cytokeratin-18 (K18, ab668-100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4 C. Gels were washed and incubated for 1 h with rabbit antigoat biotin (1:400; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and then washed and incubated overnight at 4 C with goat antimouse Alexa 488 and streptavidin-Alexa 546 (1:200; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Gels were washed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and mounted to slides with fluorescence mounting medium. A Pascal laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) was used to capture images. A 3D Z-plane series with a step size of 4 μm was used to generate each image.

Antibody blocking of α6-integrin

Isolated primary organoids were pretreated in BM suspension with 10 μg/ml of anti-α6 integrin blocking antibody (GoH3) or IgG2a isotype control (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 30 min. Organoids were plated in Col I containing 10 μg/ml GoH3 or IgG2a and allowed to gel for 20 min before addition of HGF or HGF+R5020. Organoids were maintained as described above.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated up to eight times (n = the number of experimental repeats).

Values are presented as mean ± sem. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test or ANOVA using SYSTAT (SYSTAT Software Inc., Chicago, IL) as appropriate and results considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

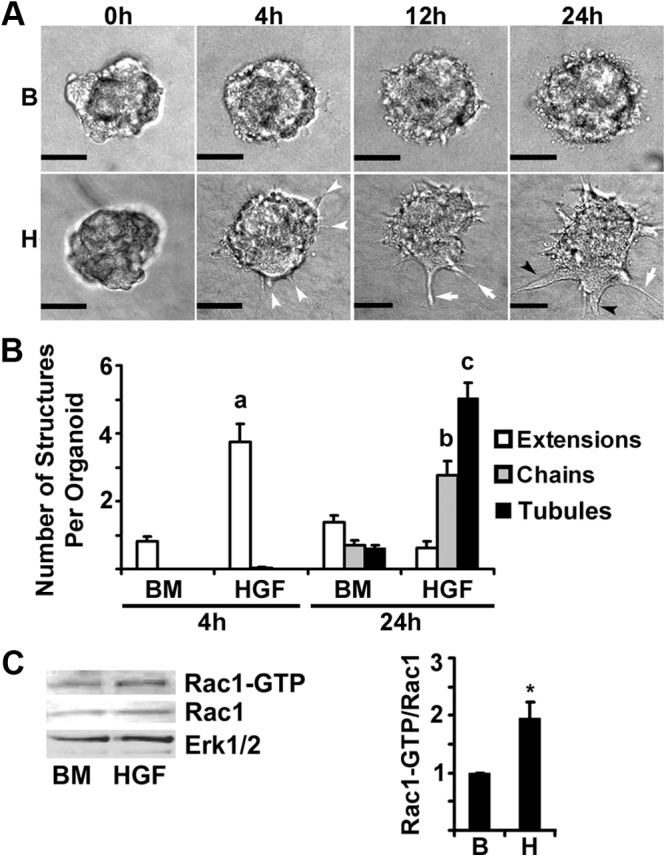

HGF induces cytoplasmic extensions to initiate tubulogenesis in mammary organoids by Rac1 activation

To determine the timing of the blunting effect of R5020 on tubulogenesis, the time course of HGF-induced tubulogenesis was analyzed from 0–24 h (Fig. 1, A and B). When first plated (0 h), organoids had a rounded morphology. The development of cytoplasmic extensions, the first step in tubulogenesis, was first observed by 4 h. By 24 h, chains and tubules were observed in HGF-treated organoids. Because Rac1 activation has been identified as an important mediator of tubulogenesis in other culture models, its role was analyzed in mammary organoid tubulogenesis. In organoids treated for 4 h with HGF, a significant (2-fold, P = 0.05) increase in activated Rac1 (Rac1-GTP) was observed coincident with cytoplasmic extension formation. To confirm the role of Rac1 in extension formation, Rac1 was silenced in organoids with shRNA. Adenoviruses were created that contained a GFP cassette and shRNA against Rac1. The presence of GFP (GFP+) allowed infected and shRNA-producing cells to be differentiated from noninfected (GFP−) cells. At 48 h after infection, organoids were treated with BM or HGF for 4 h. GFP+ extensions, chains and tubules were measured over 24 h (Fig. 2A-B). Organoids infected with vector control and scramble shRNA were able to make GFP+ and GFP− extensions, chains, and tubules. The only structures that were able to form in Rac1 shRNA-treated organoids were GFP−. The absence of GFP indicated that cells in these structures were uninfected and thus not likely to contain Rac1 shRNA. There were virtually no GFP+ extensions in the Rac1 shRNA-treated organoids at 4 or 24 h, Total Rac1 levels as measured by immunoblot were reduced by about 50% by Rac1 shRNA (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data confirmed a role for Rac1 in extension formation during tubulogenesis.

Fig. 1.

Time course of morphological changes induced by HGF. Organoids plated in Col I gels were treated with BM control (B) or HGF (H) (50 ng/ml) for up to 24 h. Panel A, Representative phase-contrast micrographs of organoids at 0, 4, 12, and 24 h. White arrowheads indicate extensions, white arrows indicate chains, and black arrowheads indicate tubules. Scale bar, 0.05 mm. Panel B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules at 4 or 24 h treatment. a–c, P < 0.05 that HGF treatment increased indicated structures compared with BM (n = 10). Panel C, Analysis of active Rac1 at 4 h treatment with HGF. Rac1-GTP levels were analyzed by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1, and fold change relative to BM was calculated. *, P < 0.05, HGF Rac1-GTP greater than BM Rac1-GTP (n = 4).

Fig. 2.

Rac1 shRNA blocks HGF-induced tubulogenesis. Organoids were infected with control virus (GFP+ vector and GFP+ scramble) or virus carrying shRNA against Rac1 (GFP+ Rac1 shRNA1 and GFP+ Rac1 shRNA2) and plated in Col I gels. At 48 h after infection, organoids were treated with HGF for 24 h. A, Representative phase-contrast and GFP overlay images of organoids at 4 and 24 h. White arrowheads indicate extensions, white arrows indicate chains, and black arrowheads indicate tubules. Insets are enlargements of GFP+ and GFP− extensions. B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules at 4 or 24 h. a–c, P < 0.05 that the numbers of indicated structures are reduced by Rac1 shRNA compared with vector control. A total of 30–50 organoids were analyzed per treatment from two separate experiments. C, Immunoblot of total Rac1 at 4 h after treatment with BM or HGF. For densitometry, Rac1 was normalized to total Erk1/2.

HGF-induced Rac1-GTP in mammary organoids is Src and FAK dependent

Src, FAK, PI3K, and MAPK have all been reported to regulate Rac1, tubulogenesis, and cell migration in other models (19, 22–25, 28). Molecular inhibitors targeting Src, FAK, PI3K, and MEK signaling were used to determine the effect on HGF-induced tubulogenesis and Rac1-GTP in mammary organoids. When organoids were treated with HGF in the presence of the Src or the FAK inhibitor, the numbers of extensions were significantly reduced compared with HGF controls (Fig. 3, A and B). Src or FAK inhibition reduced the numbers of extensions at 4 h and the numbers of chains and tubules at 24 h. Furthermore, Src or FAK inhibition significantly reduced the levels of Rac1-GTP at 4 h (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that Src and FAK signaling downstream of HGF/c-Met regulate Rac1 activity and extension formation in organoids. In contrast, when organoids were treated with HGF in the presence of the MEK inhibitor or the PI3K inhibitor, extension formation was not significantly inhibited at 4 h (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). In addition, the MEK and PI3K inhibitors did not reduce the levels of Rac1-GTP. Because R5020 can cause MEK activation and extranuclear signaling in cultured human breast cancer cells (29), we asked whether R5020 activation of this pathway contributed to the R5020 inhibition of extension formation. At 4 h in culture, the MEK inhibitor had no effect on either HGF-induced extension formation or inhibition by R5020 (Supplemental Fig. 1C). However, later at 24 h, the MEK inhibitor significantly reduced tubule number, indicating a potential role in the process of tubulogenesis after extension formation.

Fig. 3.

Src or FAK inhibition blocks HGF-induced tubulogenesis. Organoids plated in Col I gels were treated with BM (B) or HGF (H) in the presence or absence of the pp60-c Src inhibitor 2 (PP2; 20 μm) or the FAK inhibitor (FAKi-14; 10 μm) for 24 h. Panel A, Representative phase-contrast micrographs of organoids at 24 h. White arrow indicates a chain, and black arrowhead indicates a tubule. Scale bar, 0.05 mm. Panel B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules after 4 and 24 h treatment with the Src or FAK inhibitors. a–f, P < 0.05 that Src or FAK inhibitors decreased the numbers of indicated structures compared with controls (n = 3). Panel C, Rac1-GTP levels were analyzed by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. Phospho-Src levels were analyzed by immunoblot; phospho-FAK levels were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1, and fold change relative to BM was calculated. *, P < 0.05, HGF Rac1-GTP greater than BM Rac1-GTP; #, P < 0.05 that Src inhibitor or FAK inhibitor reduced HGF Rac1-GTP (n = 3).

R5020 reduces HGF-induced cytoplasmic extensions and Rac1-GTP in mammary organoid tubulogenesis

To determine when R5020 reduced tubulogenesis, the R5020 effect on early events in tubulogenesis was analyzed (Fig. 4, A–D). At 4 h, R5020 significantly decreased the number of HGF-induced cytoplasmic extensions (Fig. 4, A and B). Furthermore, by 4 h, HGF+R5020-treated organoids had significantly lower levels of Rac1-GTP than HGF-treated organoids, suggesting that R5020 interferes with Rac-1 activation (Fig. 4C). Because Src and FAK were necessary for Rac1-GTP and extension formation in tubulogenesis, the levels of phospho-Src and phospho-FAK were also analyzed. Phospho-Src and phospho-FAK were also reduced in HGF+R5020-treated organoids (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that R5020 decreases HGF-induced extensions through reduced activation of Src, FAK, and Rac1.

Fig. 4.

R5020 reduces HGF-induced tubulogenesis. Organoids plated in Col I gels were treated with BM (B), HGF (H), or HGF+R5020 (HR) for 4 h. Panel A, Representative phase-contrast micrographs of organoids at 4 h. White arrowhead indicates extensions. Scale bar, 0.05 mm. Panel B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules after 4 h treatment. a, P < 0.05 that HGF+R5020 reduced the numbers of indicated structures compared with HGF (n = 7). Panel C, The effect of R5020 on HGF-induced Rac1 activation. Rac1-GTP levels at 4 h were determined by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1, and fold change relative to BM was calculated. *, P < 0.05, HGF Rac1-GTP greater than BM Rac1-GTP; #, P < 0.05 that R5020 reduced HGF Rac1-GTP (n = 3). Panel D, Representative immunoblots of the R5020 effect on phospho-Src and phospho-FAK 4 h after treatment.

RANKL is a progestin-induced paracrine factor that mediates proliferation in vivo and is implicated in progesterone-induced side branching (6, 30). We have previously shown that RANKL in combination with HGF specifically promotes MEC proliferation in our organoid culture model (15). We examined the effect of HGF plus RANKL on tubulogenesis and found that RANKL did not reproduce the tubule shortening that was observed with HGF+R5020 (Supplemental Fig. 2).

R5020 up-regulates Lm-5 and reduces HGF-induced Rac1-GTP and tubulogenesis

Next, we investigated how R5020 reduced Src, FAK, and Rac1 activity in HGF+R5020-treated organoids. An important contributor to tubulogenesis is the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which can influence a cell's response to hormones and growth factors (31). MDCK cells embedded in Col I form tubules in response to HGF but do not when embedded in Lm-1-rich Matrigel (32, 33). This was also observed for mammary organoids in our culture model (Supplemental Fig. 3). From previous microarray analysis of cultured mouse mammary organoids, Lmγ2 (subunit of Lm-5) mRNA was found to be up-regulated by R5020 (26). This led to the hypothesis that Lm acts as an R5020-induced paracrine factor to reduce Rac1-GTP level and extension formation in mammary organoids undergoing tubulogenesis.

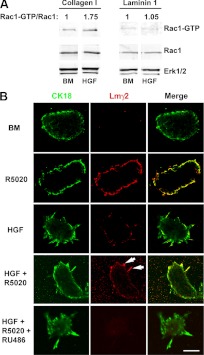

Previous studies of ECM effects on steroid hormone response in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells plated in 2D culture showed a robust effect of Lm to inhibit Rac-1 activation (31). Thus, we used this approach as a first step to see whether Lm had a similar effect on normal mouse mammary organoids plated in 2D culture. In primary mammary epithelial cells cultured on Col I- or Lm-1-coated plates and treated with HGF for 4 h, the Rac1-GTP level was increased in cells cultured on Col I but not on Lm-1 (Fig. 5A). These results are consistent with the concept that altered composition of the ECM can modulate the Rac-1-GTP level in response to HGF treatment. In-gel immunofluorescence antibody labeling of intact organoids after 24 h treatment showed the highest level of Lmγ2 in R5020-treated cultures, the lowest levels of Lmγ2 in BM and HGF-treated organoids, and an intermediate level of Lmγ2 in HGF+R5020-treated organoids (Fig. 5B). Lmγ2 was predominantly localized at the outer edge of the organoids treated with R5020. Notably, increased expression was localized to the shortened tubules in the HGF+R5020-treated organoids. This was in contrast to the very low level of Lmγ2 observed surrounding tubules formed in the HGF-treated organoids. Treatment with HGF+R5020 plus RU486, a PR antagonist, resulted in a loss of Lmγ2 staining, and well-formed tubules were observed. We also looked at Lmγ2 protein expression earlier, at 4 h, and found results similar to those at 24 h (Supplemental Fig. 4). The 4-h R5020-induced increase of Lmγ2 was consistent with the R5020 inhibitory effect at 4 h. These results are consistent with our previous report that R5020 induced Lmγ2 mRNA expression and indicates that R5020-induced Lmγ2 induction can alter the ECM composition surrounding organoids.

Fig. 5.

R5020 increases Lmγ2 expression in mammary organoids, and Lm reduces HGF-induced Rac1-GTP. A, Organoids were cultured as a monolayer on Col I or Lm-1 and treated with BM or HGF for 4 h. Rac1-GTP levels were analyzed by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1, and fold change relative to BM was calculated. B, Confocal immunofluorescence images of organoids plated on Col I gels at 4 h after in situ double-antibody labeling with anti-cytokeratin 18 (CK18) (green) and anti-Lmγ2 (red). Note increased intensity of Lmγ2 (red) staining in R5020- and HGF+R5020-treated organoids. HGF+R5020 treatment increased Lmγ2 (red) staining that was localized to blunted tubules (white arrows). There was a loss of staining upon RU486 addition to HGF+R5020-treated organoids. Scale bar, 0.05 mm.

To determine whether R5020-induced Lmγ2 was responsible for stunted tubulogenesis, organoids were infected with adenovirus delivering a GFP+ Lmγ2 shRNA vector or GFP+ scramble control; organoids were treated with HGF or HGF+R5020, and the effect on morphology and Rac1 activity was assessed (Fig. 6, A–D). The shRNA knockdown of Lmγ2 was confirmed by RT-PCR (Supplemental Table 1). Compared with HGF+R5020 controls, HGF+R5020-treated organoids that had been infected with Lmγ2 shRNA were able to produce significantly more tubules at 24 h (Fig. 6, A and B). The percentage of organoids with long tubules was also significantly greater in Lmγ2 shRNA-treated organoids compared with the HGF+R5020-treated controls (Fig. 6C). In addition, increased Rac1-GTP and phospho-Src levels were detected in Lmγ2 shRNA-treated organoids compared with HGF+R5020 controls. Taken together, these results are consistent with Lm-5 as an R5020-mediated paracrine factor that inhibits HGF-induced tubulogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Lmγ2 shRNA reverses the effect of R5020 on tubulogenesis. Organoids were infected with control virus (GFP+ scramble) or virus carrying shRNA against Lmγ2 (GFP+ Lmγ2 shRNA) and plated in Col I gels. At 24 h after infection, organoids were treated with HGF (H) or HGF+R5020 (HR) for 24 h. A, Representative phase-contrast and GFP overlay images of organoids at 24 h. White arrows indicate chains, and black arrowheads indicate tubules. B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules at 4 or 24 h. a, P < 0.05 that Lmγ2 shRNA increased the number of tubules compared with HR controls. A total of 48–67 organoids were analyzed per treatment from two separate experiments. C, Quantitation of the percentage of organoids producing long tubules (≥50 pixels); 134–141 organoids were analyzed per treatment from three separate experiments. *, P < 0.05 that Lmγ2 shRNA increased the percentage of organoids with long tubules. D and E, The effect of Lmγ2 shRNA on Rac1 activation (D) and phospho-Src (E). Rac1-GTP levels were analyzed by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1. Phospho-Src was assessed by immunoblot 4 h after treatment with HGF+R5020.

Lm-5 signals through α6-integrins. Additional support for the contention that Lm-5 negatively regulates tubulogenesis was obtained by blocking α6-integrin action with an α6-integrin-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 7, A–D). Antibody blocking of α6-integrins in HGF+R5020-treated organoids restored extension and tubule formation at 4 and 24 h to the level seen with HGF alone (Fig. 7, A and B). In addition, at 24 h, there was a trend toward a higher percentage of longer tubules in antibody-treated HGF+R5020-treated organoids (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that blocking α6-integrin reduced the R5020-blunting effect on tubulogenesis. Furthermore, the levels of Rac1-GTP and phospho-Src were increased after antibody blocking of α6-integrin in HGF+R5020-treated organoids. These results are consistent with the interpretation that R5020 up-regulates Lm-5/α6-integrin signaling, which has an inhibitory effect on Src and Rac1 activation resulting in reduced extension formation and blunted tubulogenesis.

Fig. 7.

Effect of antibody blocking of α6-integrin on R5020 inhibition of tubulogenesis. Organoids plated in Col I gels were treated with HGF (H) or HGF+R5020 (HR) in the presence or absence of the α6-integrin blocking antibody, GoH3 (10 μg/ml) for 24 h. A, Representative phase-contrast micrographs of organoids at 24 h. White arrows indicate chains, and black arrowheads indicate tubules. Scale bar, 0.05 mm. B, Quantitation of extensions, chains, and tubules after 4 and 24 h treatment. A total of 54–69 organoids were analyzed per treatment from two separate experiments. C, Percentage of organoids forming long tubules (≥140 pixels) after 24 h. D, The effect of α6-integrin blocking antibody on Rac1 activity and phospho-Src. A representative experiment shows Rac1-GTP and phospho-Src levels at 4 h analyzed by Rac1-GTP pull-down and immunoblot. For densitometry, Rac1-GTP was normalized to total Rac1.

Discussion

In vitro HGF induces tubule development in mouse mammary organoids in 3D Col I gel cultures that mimic mammary duct formation in vivo. When combined with HGF, R5020, a synthetic progestin, causes blunting of tubulogenesis. In this report, we determined that the initial step in tubule formation, cytoplasmic extension formation, is mediated by HGF/c-Met activation of Src, FAK, and Rac1. Activation of this pathway was reduced by R5020 to produce fewer cytoplasmic extensions and shorter tubules. The novel finding in these studies was that R5020 produced this response by decreasing activation of Src/FAK/Rac-1 signaling through increased Lm-5 expression and paracrine signaling through α6-integrin. An important step in progesterone-induced mammary gland lactational differentiation during pregnancy in vivo is the development of side branches seen as short ductal extensions off longer established ducts. These side branches form the platform for alveolar development in preparation for lactation. The underlying mechanism of progesterone-induced side branch formation is not known. Based on the present results, we hypothesize that the progestin-induced blunting of HGF-induced tubulogenesis in vitro mimics progesterone-induced side branching in vivo and is likely mediated by similar mechanisms (13).

HGF activates a Src/FAK-Rac1 pathway to induce tubule formation

HGF-induced extension formation by 4 h coincided with increased Rac1-GTP levels. Through the use of shRNA against Rac1, the GTPase was identified as a key regulator of extension formation. For MDCK cells, in vitro extension formation and tubulogenesis are also mediated through Rac1 signaling (18). Thus, mammary organoids, composed of two cell types, behave similarly to MDCK cells. We have previously reported that LEC rather than MEC form extensions (15). Therefore, it is likely that Rac1-induced changes during extension formation is occurring mainly in the LEC.

Using specific inhibitors, Src and FAK were identified as key upstream regulators of Rac1 activity and extension formation. Although HGF-induced Src has been implicated in motility and proliferation of mouse mammary carcinoma cells (24), a role for Src in tubulogenesis of normal mouse mammary cells has not been previously reported. FAK and Src have been documented to cooperate at focal adhesions and to mediate both integrin and receptor tyrosine kinase signaling (34). Interestingly, a role for Src in tubulogenesis in MDCK cells has not been reported. In contrast, MEK and PI3K mediate cell migration and tubulogenesis of MDCK cells (21–23, 35). However, MEK and PI3K inhibition failed to reduce Rac1-GTP levels in the present studies.

Significant proliferation in organoids is not detected before 48 h of culture (14, 36). Although no effect was observed on early steps of tubulogenesis, i.e. extension formation, we have observed that MEK and PI3K inhibition severely impairs proliferation at 48 and 72 h when tubules mature. In this regard, a late effect on proliferation was also observed when Rac1, Src, and FAK1 were inhibited in organoids (Meyer, G., and S. Z. Haslam, unpublished observations). This suggests that Rac1, Src, and FAK1 contribute to both early tubulogenesis (extension formation) and later to proliferation, whereas MEK and PI3K signaling may be more important for the later steps in tubulogenesis and proliferation. These results are relevant for understanding how the temporal sequence and underlying mechanisms of signaling pathways control motility and/or proliferation in normal mammary cells.

R5020 reduces the Src-FAK-Rac1 pathway and extension formation

R5020 inhibited the early stage of tubulogenesis in organoids treated with HGF+R5020 by decreasing the level of Rac1-GTP, resulting in a reduced number of extensions. Furthermore, R5020 also reduced the levels of phospho-Src and phospho-FAK. Therefore it is likely that R5020 blunts HGF-induced tubulogenesis through inhibiting activation of the Src-FAK-Rac1 pathway. This early effect of R5020 likely contributes to the previously reported shortened tubules that develop in HGF+R5020-treated organoids (13). Notably, MEK inhibition had no effect on R5020 inhibition of extension formation. In human breast cancer cells, progestin has been shown to activate ERK1/2 and to activate downstream signaling and transcriptional responses independent from the transcriptional activity of the PR (29). This action of progestin is believed to be mediated through the B isoform of the PR (PRB) (29). In mouse mammary organoids, the PRA isoform predominates (15), and this could account for a lack of effect of MEK inhibition on the R5020 response. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence of progestin regulating Rac1 to control tubulogenesis of primary mammary organoids.

R5020 increases Lm-5 expression to decrease HGF-induced tubulogenesis

The role of ECM composition on tubulogenesis was investigated based on the previous findings that MDCK cells in Lm-rich Matrigel do not form tubules in response to HGF (32, 33) and the previous finding that R5020 signaling induces expression of Lm mRNA in organoids in collagen gel culture (26). We found that Rac1-GTP level was reduced in mammary epithelial cells when cultured on Lm compared with culture on Col I. We determined that R5020 increased expression and protein level of Lmγ2 (subunit of Lm-5) in mammary organoids. When Lmγ2 was silenced, Rac1-GTP level and tubule length and number were restored. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that Lm-5 is an R5020-induced paracrine factor that negatively regulates tubulogenesis. Blocking α6-integrin also restored Rac1-GTP level and tubulogenesis in HGF+R5020-treated organoids. Taken together, the present findings suggest that Lm-5/α6-integrin signaling negatively regulates tubulogenesis and Rac1-GTP and that R5020-induced Lm-5/α6-integrin signaling contributes to reduced cytoplasmic extensions and shorter tubules observed in HGF+R5020-treated organoids.

It is well established that ECM composition influences the physical organization and functions of mammary epithelial cells in vitro (37). Laminin-rich Matrigel has been shown to promote lumen formation and lactational differentiation of mouse mammary epithelial cells in 3D culture (38). It has also been shown that α6-integrin signaling plays a critical role in Lm-induced mammary cell lactational differentiation in vitro (39). Matrigel also promotes lumen formation of immortalized, nontransformed human MCF-10A breast epithelial cells (40). Thus, our current findings that R5020-induced lumen formation within organoid bodies was associated with increased expression and extracellular localization of Lmγ2 is consistent with previous findings about lumen formation. Our present studies extend these findings to show that Lm-rich ECM (Matrigel) inhibits tubule formation of HGF-treated mammary organoids and increased Lm (Lmγ2) expression and α6-integrin signaling induced by HGF+R5020 caused decreased tubule formation. Notably, the induced Lmγ2 was localized to the tips of blunted tubules. Thus, Lm in the ECM provided exogenously (Matrigel) or produced endogenously (Lmγ2) by progestin serves to blunt tubule development in vitro. We propose that similar progesterone-dependent processes may take place to produce ductal side branching, an early step leading to lactational differentiation in vivo.

RANKL has been identified as a progesterone-induced paracrine factor involved in the side-branching response in vivo (6, 30). We have previously investigated the effect of RANKL in our mammary organoid culture system and determined that in conjunction with HGF, its predominant effect is to specifically increase MEC proliferation (15). We have also examined the effect of RANKL on tubulogenesis herein and found that it did not reproduce the effect of R5020 when combined with HGF.

Because the adult mammary gland that was the source of our organoids predominantly expresses PR isoform A (PRA) (41) and the organoids express predominantly PRA (15), we postulate that the observed effects of R5020 are mediated through PRA. This is likely mediated through nuclear signaling because we have previously reported (13) and showed in this report that the PR inhibitor RU486 blocks R5020's inhibitory effect on tubulogenesis. To our knowledge, there is no report on a potential effect on side branching in PRA gene-deleted (PRAKO) mice. It should be noted that the PRAKO phenotype was studied in a C57BL/6 background (2). We have previously reported that C57BL/6 mice are insensitive to progesterone action before pregnancy and side branching is significantly delayed during pregnancy in that strain compared with the BALB/c strain studied in the present report (42). This raises the possibility that different signaling pathways may regulate side branching in C57BL/6 mice.

The first step on the road to alveologenesis and lactational differentiation is the formation of side branches, i.e. shortened ducts. Alveologenesis can be viewed as a transition from extensive ductal elongation to the production by proliferation of highly differentiated alveolar cells; this process requires a limited form of ductal development. Thus, although progesterone action is key to the proliferative expansion of alveolar mammary epithelial cells, it also produces short ducts, i.e. side branches. Taken together, the present findings lead us to propose the following model of mammary organoid tubulogenesis and side branching. Under HGF treatment and increased Rac1-GTP, LEC in Col I form cytoplasmic extensions that become motile and migrate to form tubules. In the presence of R5020, PRA up-regulates Lm-5 and blunts the tubulogenic response to HGF through an Lm-5/α6-integrin inhibition of a Rac1-mediated pathway. We hypothesize that R5020-induced blunting of tubulogenesis in vitro may be a surrogate for the formation of the short ducts produced during the side-branching response induced by progesterone in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA-40104 to S.Z.H. and by the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers Grant U01 ES/CA 012800 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Science and the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (to S.Z.H.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Science or National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BM

- Basal medium

- Col I

- collagen I

- 3D

- three-dimensional

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- LEC

- luminal epithelial cell

- Lm

- laminin

- MEC

- myoepithelial cell

- MEK

- MAPK kinase

- MOI

- multiplicity of infection

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PP2

- pp60-c Src inhibitor 2

- PR

- progesterone receptor

- Rac1

- Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- Src

- Src kinase.

References

- 1. Aupperlee MD, Haslam SZ. 2007. Differential hormonal regulation and function of progesterone receptor isoforms in normal adult mouse mammary gland. Endocrinology 148:2290–2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Jr, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. 1995. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev 9:2266–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fernandez-Valdivia R, Mukherjee A, Ying Y, Li J, Paquet M, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP. 2009. The RANKL signaling axis is sufficient to elicit ductal side-branching and alveologenesis in the mammary gland of the virgin mouse. Dev Biol 328:127–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brisken C, Heineman A, Chavarria T, Elenbaas B, Tan J, Dey SK, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Weinberg RA. 2000. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev 14:650–654 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao Y, Bonizzi G, Seagroves TN, Greten FR, Johnson R, Schmidt EV, Karin M. 2001. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell 107:763–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beleut M, Rajaram RD, Caikovski M, Ayyanan A, Germano D, Choi Y, Schneider P, Brisken C. 2010. Two distinct mechanisms underlie progesterone-induced proliferation in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:2989–2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F, Sheridan JM, Pal B, Wu D, Simpson ER, Yasuda H, Smyth GK, Martin TJ, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. 2010. Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature 465:798–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joshi PA, Jackson HW, Beristain AG, Di Grappa MA, Mote PA, Clarke CL, Stingl J, Waterhouse PD, Khokha R. 2010. Progesterone induces adult mammary stem cell expansion. Nature 465:803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Itakura A, Kurauchi O, Morikawa S, Okamura M, Furugori K, Mizutani S. 1997. Involvement of hepatocyte growth factor in formation of bronchoalveolar structures in embryonic rat lung in primary culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 241:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furue M, Okamoto T, Hayashi H, Sato JD, Asashima M, Saito S. 1999. Effects of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and activin A on the morphogenesis of rat submandibular gland-derived epithelial cells in serum-free collagen gel culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 35:131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montesano R, Soriano JV, Pepper MS, Orci L. 1997. Induction of epithelial branching tubulogenesis in vitro. J Cell Physiol 173:152–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soriano JV, Pepper MS, Nakamura T, Orci L, Montesano R. 1995. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates extensive development of branching duct-like structures by cloned mammary gland epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 108(Pt 2):413–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sunil N, Bennett JM, Haslam SZ. 2002. Hepatocyte growth factor is required for progestin-induced epithelial cell proliferation and alveolar-like morphogenesis in serum-free culture of normal mammary epithelial cells. Endocrinology 143:2953–2960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang HZ, Bennett JM, Smith KT, Sunil N, Haslam SZ. 2002. Estrogen mediates mammary epithelial cell proliferation in serum-free culture indirectly via mammary stroma-derived hepatocyte growth factor. Endocrinology 143:3427–3434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haslam SZ, Drolet A, Smith K, Tan M, Aupperlee M. 2008. Progestin-regulated luminal cell and myoepithelial cell-specific responses in mammary organoid culture. Endocrinology 149:2098–2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ridley AJ, Hall A. 1992. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell 70:389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ridley AJ, Comoglio PM, Hall A. 1995. Regulation of scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor responses by Ras, Rac, and Rho in MDCK cells. Mol Cell Biol 15:1110–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogers KK, Jou TS, Guo W, Lipschutz JH. 2003. The Rho family of small GTPases is involved in epithelial cystogenesis and tubulogenesis. Kidney Int 63:1632–1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishibe S, Joly D, Liu ZX, Cantley LG. 2004. Paxillin serves as an ERK-regulated scaffold for coordinating FAK and Rac activation in epithelial morphogenesis. Molecular cell 16:257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tushir JS, D'Souza-Schorey C. 2007. ARF6-dependent activation of ERK and Rac1 modulates epithelial tubule development. EMBO J 26:1806–1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Brien LE, Tang K, Kats ES, Schutz-Geschwender A, Lipschutz JH, Mostov KE. 2004. ERK and MMPs sequentially regulate distinct stages of epithelial tubule development. Dev Cell 7:21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khwaja A, Lehmann K, Marte BM, Downward J. 1998. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase induces scattering and tubulogenesis in epithelial cells through a novel pathway. J Biol Chem 273:18793–18801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu W, O'Brien LE, Wang F, Bourne H, Mostov KE, Zegers MM. 2003. Hepatocyte growth factor switches orientation of polarity and mode of movement during morphogenesis of multicellular epithelial structures. Mol Biol Cell 14:748–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rahimi N, Hung W, Tremblay E, Saulnier R, Elliott B. 1998. c-Src kinase activity is required for hepatocyte growth factor-induced motility and anchorage-independent growth of mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 273:33714–33721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chianale F, Rainero E, Cianflone C, Bettio V, Pighini A, Porporato PE, Filigheddu N, Serini G, Sinigaglia F, Baldanzi G, Graziani A. 2010. Diacylglycerol kinase α mediates HGF-induced Rac activation and membrane ruffling by regulating atypical PKC and RhoGDI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4182–4187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Santos SJ, Aupperlee MD, Xie J, Durairaj S, Miksicek R, Conrad SE, Leipprandt JR, Tan YS, Schwartz RC, Haslam SZ. 2009. Progesterone receptor A-regulated gene expression in mammary organoid cultures. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 115:161–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamazaki D, Kurisu S, Takenawa T. 2009. Involvement of Rac and Rho signaling in cancer cell motility in 3D substrates. Oncogene 28:1570–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chianale F, Cutrupi S, Rainero E, Baldanzi G, Porporato PE, Traini S, Filigheddu N, Gnocchi VF, Santoro MM, Parolini O, van Blitterswijk WJ, Sinigaglia F, Graziani A. 2007. Diacylglycerol kinase-α mediates hepatocyte growth factor-induced epithelial cell scatter by regulating Rac activation and membrane ruffling. Mol Biol Cell 18:4859–4871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boonyaratanakornkit V, McGowan E, Sherman L, Mancini MA, Cheskis BJ, Edwards DP. 2007. The role of extranuclear signaling actions of progesterone receptor in mediating progesterone regulation of gene expression and the cell cycle. Mol Endocrinol 21:359–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM. 2003. Defective mammary gland morphogenesis in mice lacking the progesterone receptor B isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9744–9749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie JW, Haslam SZ. 2008. Extracellular matrix, Rac1 signaling, and estrogen-induced proliferation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Breast cancer research and treatment 110:257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santos OF, Nigam SK. 1993. HGF-induced tubulogenesis and branching of epithelial cells is modulated by extracellular matrix and TGF-β. Dev Biol 160:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams MJ, Clark P. 2003. Microscopic analysis of the cellular events during scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor-induced epithelial tubulogenesis. J Anat 203:483–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen HC, Chan PC, Tang MJ, Cheng CH, Chang TJ. 1998. Tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase stimulated by hepatocyte growth factor leads to mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem 273:25777–25782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Popsueva A, Poteryaev D, Arighi E, Meng X, Angers-Loustau A, Kaplan D, Saarma M, Sariola H. 2003. GDNF promotes tubulogenesis of GFRalpha1-expressing MDCK cells by Src-mediated phosphorylation of Met receptor tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biol 161:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xie J, Haslam SZ. 1997. Extracellular matrix regulates ovarian hormone-dependent proliferation of mouse mammary epithelial cells. Endocrinology 138:2466–2473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nelson CM, Vanduijn MM, Inman JL, Fletcher DA, Bissell MJ. 2006. Tissue geometry determines sites of mammary branching morphogenesis in organotypic cultures. Science 314:298–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Medina D, Li ML, Oborn CJ, Bissell MJ. 1987. Casein gene expression in mouse mammary epithelial cell lines: dependence upon extracellular matrix and cell type. Exp Cell Res 172:192–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmeichel KL, Weaver VM, Bissell MJ. 1998. Structural cues from the tissue microenvironment are essential determinants of the human mammary epithelial cell phenotype. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 3:201–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mailleux AA, Overholtzer M, Brugge JS. 2008. Lumen formation during mammary epithelial morphogenesis: insights from in vitro and in vivo models. Cell Cycle 7:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aupperlee MD, Smith KT, Kariagina A, Haslam SZ. 2005. Progesterone receptor isoforms A and B: temporal and spatial differences in expression during murine mammary gland development. Endocrinology 146:3577–3588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aupperlee MD, Drolet AA, Durairaj S, Wang W, Schwartz RC, Haslam SZ. 2009. Strain-specific differences in the mechanisms of progesterone regulation of murine mammary gland development. Endocrinology 150:1485–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.