Abstract

Adipocytes express angiotensin receptors, but the direct effects of angiotensin II (AngII) stimulating this cell type are undefined. Adipocytes express angiotensin type 1a receptor (AT1aR) and AT2R, both of which have been implicated in obesity. In this study, we determined the effects of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency on adipocyte differentiation and the development of obesity in mice fed low-fat (LF) or high-fat (HF) diets. Mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the aP2 promoter were bred with AT1aR-floxed mice to generate mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency (AT1aRaP2). AT1aR mRNA abundance was reduced significantly in both white and brown adipose tissue from AT1aRaP2 mice compared with nontransgenic littermates (AT1aRfl/fl). Adipocyte AT1aR deficiency did not influence body weight, glucose tolerance, or blood pressure in mice fed either LF or high-fat diets. However, LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice exhibited striking adipocyte hypertrophy even though total fat mass was not different between genotypes. Stromal vascular cells from AT1aRaP2 mice differentiated to a lesser extent to adipocytes compared with controls. Conversely, incubation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with AngII increased Oil Red O staining and increased mRNA abundance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) via AT1R stimulation. These results suggest that reductions in adipocyte differentiation in LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice resulted in increased lipid storage and hypertrophy of remaining adipocytes. These results demonstrate that AngII regulates adipocyte differentiation and morphology through the adipocyte AT1aR in lean mice.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has well-established roles in fluid homeostasis, blood pressure regulation, and the development of various forms of cardiovascular diseases. Several cell types express components of the RAS (1) allowing for angiotensin II (AngII) to elicit endocrine, autocrine, and/or paracrine effects. Adipocytes express angiotensin receptors, with differences in angiotensin receptor subtype expression depending on the species and source of adipose tissue (2–4). In rodents, angiotensin type 1a receptors (AT1aR) and AT2R have been localized to adipocytes (5, 6), whereas AT1bR are not readily detectable in murine adipose tissue (7). The functional and/or pathophysiological role of angiotensin receptor subtypes in adipocytes is unclear.

Genetic ablation of RAS components, including angiotensinogen, renin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and AT1aR in mice, results in reduced body weight due to reductions in fat mass when mice are fed standard or high-fat (HF) diets (8–11), although there are contrary data (12, 13). Even more perplexing, infusion of high doses of AngII can also result in weight loss and reduced adiposity (14–17), making it difficult to define the role of AngII in the regulation of adipocyte growth and/or differentiation. These apparent contradictions have yet to be resolved and are complicated by direct vs. indirect effects of AngII on adipose growth and development.

In studies aimed at examining direct effects of AngII to regulate adipocyte differentiation using clonal cell lines or ex vivo differentiation of preadipocytes, conflicting results have also been obtained. Several studies indicate that AngII enhances adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation (6, 18, 19), whereas others suggest that AngII inhibits adipocyte differentiation (20–23). There are also conflicting reports regarding which of the AngII receptors are responsible for these effects, because investigators have reported that AngII stimulates adipogenesis through the AT1R or AT2R (6), whereas other studies have reported that AngII inhibits adipocyte differentiation (21). The use of AT1R antagonists with AT1R-independent effects on adipocyte differentiation [i.e. activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)] (24, 25) complicates interpretation of results from these studies.

Based on results from mouse models demonstrating that whole body deficiency of components of the RAS reduces body weight and fat mass, we hypothesized that AngII promotes differentiation through direct effects at adipocyte AT1aR, which may have therapeutic implications in the development and/or treatment of obesity. To test this hypothesis, we generated mice with adipocyte deficiency of AT1aR. In HF-fed mice, deficiency of AT1aR in adipocytes had no effect on the development of obesity, glucose intolerance, and obesity-induced hypertension. Notably, low fat (LF)-fed mice lacking AT1aR in adipocytes exhibited pronounced adipocyte hypertrophy in visceral and sc adipose depots, and stromal vascular cells (SVC) isolated from mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency exhibited reduced capacity to differentiate to adipocytes. These results suggest that AngII promotes adipocyte differentiation through direct effects at adipocyte AT1aR in lean mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice and diet

All experiments were conducted according to National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. AT1aR-floxed (AT1aRfl/fl) mice (26) were crossed initially to FLPe mice (B6.SJL-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to remove the neocassette, and subsequently female AT1aRfl/fl mice were bred to hemizygous transgenic male Cre mice under control of an aP2/promoter/enhancer.Cg-Tg (Fabp4-cre 1Rev/J; The Jackson Laboratory) (Fig. 1A). For all studies, male and female AT1aRfl/fl littermates were used for comparison with mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency. Male mice (8–10 wk of age) of each genotype were fed either LF (10% kcal as fat, D12450B; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or HF diets (60% kcal as fat, D12492; Research Diets) ad libitum for 16 wk with free access to water. AT1aRaP2 mice were bred to ROSA26 mice [B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sor<tm1Sor>/J; The Jackson Laboratory], and β-galactosidase activity was measured to confirm lineage expression of Cre recombinase in adipose tissue. Briefly, adipose tissues collected from aP2-Cre null (Cre 0/0) and aP2-Cre positive (Cre+/0) AT1aRfl/+ mice heterozygous for the ROSA26 allele were sectioned and stained overnight with X-gal. Blue staining indicated successful removal of a stop codon from the β-galactosidase gene by Cre recombinase.

Fig. 1.

Development of mice with adipocyte deficiency of AT1aR. A, Mice with loxP sites flanking exon 3 of the AT1aR gene (a) were bred to mice expressing flippase (FLP) that recognizes the FRT sites to remove the neocassette (b). c, AT1aRfl/fl mice were bred to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the aP2 promoter to generate adipocyte AT1aR-deficient mice (AT1aRaP2) and nontransgenic littermates (AT1aRfl/fl). B, AT1aR adipocyte deficiency was confirmed in BAT and WAT, respectively. Data are represented as mean ± sem from n = 8–10 mice/group. *, P < 0.05 compared with AT1aRfl/fl.

Measurement of body composition

Body weights were recorded weekly for all mice. The body composition of a subset of mice was analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy [EchoMRI (magnetic resonance imaging)] before mice began the diet and after 14 wk on diet.

Measurement of glucose tolerance

Glucose tolerance tests were performed after 8 and 15 wk on diet. Mice were fasted 6 h, and blood glucose measurements were measured at 0 min (before injection of glucose solution) and at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after ip injection of glucose (1 g/kg body weight). After 14 wk on diet, insulin tolerance tests were performed after a 4-h fast. Insulin was administered at a dose of 0.5 U/kg body weight via ip injection, and blood glucose was measured at 0 min (before injection of insulin) and at 30, 60, and 120 min after insulin injection.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure and physical activity were measured by telemetry for 3 d. After 15 wk on diet, telemetry implants (model TA11PA-C10; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were surgically inserted as described previously (27). After 16 wk on diet, baseline blood pressures were recorded for three consecutive day and night periods. Mice were excluded before obtaining measurements (n = 1/28 AT1aRfl/fl, n = 2/20 AT1aRaP2) if their mean pulse pressure was less than 17 mm Hg, as an indication of a poor signal from the telemeter to the receiver.

Plasma measurements

Mice were terminated after a 4-h fast. Plasma renin concentrations were measured by incubating plasma (8 μl) with exogenous angiotensinogen (25 nm) in the presence of ACE inhibitors, and then AngI was quantified by RIA (DiaSorin, Via Crescentino, Italy). Plasma angiotensinogen concentrations were quantified using mouse total angiotensinogen assay kits (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan). Plasma insulin concentrations were quantified with the Ultra Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL), and plasma leptin concentrations were quantified with a Mouse Leptin ELISA kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) were quantified with the NEFA-HR(2) kit (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA).

Quantification of mRNA abundance

To quantify mRNA abundance, RNA was isolated using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI). RT was performed on RNA (0.4 μg) using qScript cDNA SuperMix as per manufacturer's instructions (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Real-time PCR was performed with PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix for iQ on 2 ng of cDNA template (Quanta Biosciences). A standard curve was generated from a series of 10-fold dilutions of cDNA with each real-time PCR plate, and this was used to extrapolate the relative starting quantity of mRNA for the gene of interest from the given threshold cycle values. Data are expressed as the ratio of the gene of interest starting quantity to that of 18S.

Determination of adipocyte size

Sections of formalin (10% wt/vol) fixed pieces of retroperitoneal or sc adipose tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images of slides were obtained at ×10 magnification. Using the “detect edges,” image threshold, and object count features of NIS Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), the area of each adipocyte and the number of adipocytes within a 700 × 700 μm measurement frame were quantified by an individual blinded to experimental groups. Adipocyte size and number were quantified on three measurement frames within each section of adipose tissue (n = 3 sections/mouse) from mice in each group (n = 3 mice/group).

Differentiation of preadipocytes from SVC

Subcutaneous adipose tissue was dissected from the inguinal region, minced, and incubated in basal medium (OM-BM; Zenbio, Research Triangle Park, NC) supplemented with collagenase (1 mg/ml) and penicillin/streptomyocin mixture (5%) for at least 1 h with shaking at 37 C as described previously (28). Two days after cells had achieved 100% confluency, media were changed to differentiation medium (OM-DM; Zenbio) and replaced every other day for 8 d. Cells were either harvested for RNA using TRIzol or fixed and subsequently stained with Oil Red O (ORO). For ORO measurements, cells were fixed in formalin (10%) and stained with filtered ORO (0.3% wt/vol) solution for 30 min at room temperature. For quantification, isopropanol (1 ml) was added to the plates to extract ORO stain, this solution was transferred to a microtiter plate, and absorbance was measured at 510 nm.

3T3-L1 adipocytes

3T3-L1 adipocytes were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in DMEM containing fetal bovine serum (10%) and penicillin/streptomyocin mixture (5%). Two days after cells were 100% confluent, differentiation of preadipocytes was initiated by administration of a cocktail containing insulin (0.1 μm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), dexamethasone (1 μm; Sigma-Aldrich), and isobutyl methyl xanthine (0.5 mm; Sigma-Aldrich). Incubation with AngII (1 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) or losartan (1 μm) was performed with fresh media containing drugs replaced every other day. After 6 d of differentiation, cells were harvested for RNA isolation using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or for quantification of ORO staining as described above.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed by ANOVA for comparisons between the four diet/genotype groups, as appropriate, using the Holm Sidak test for post hoc analysis. When time was an additional variable, data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA. Data are represented as mean ± sem. If normality or equal variance tests failed, simple transforms were performed or the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used with Dunn's post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Generation of mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency

To confirm effective and specific deletion of exon 3 of AT1aR in adipocytes, AT1aR mRNA abundance was quantified in adipose tissues, liver, kidney, heart, and spleen from mice fed standard laboratory diet. AT1aR mRNA abundances were not significantly different in liver, kidney, spleen, or brains from AT1aRfl/fl compared with AT1aRaP2 mice (Fig. 1B). In heart, AT1aR mRNA abundance was reduced modestly, but significantly, in AT1aRaP2 compared with AT1aRfl/fl mice. In interscapular brown adipose tissue (BAT) and epididymal white adipose tissue (WAT), AT1aR mRNA abundance was decreased significantly in AT1aRaP2 compared with AT1aRfl/fl mice. Moreover, positive β-galactosidase staining was present in sc WAT and interscapular BAT of Cre +/0 mice (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org).

Adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no effect on the development of obesity or obesity-associated parameters

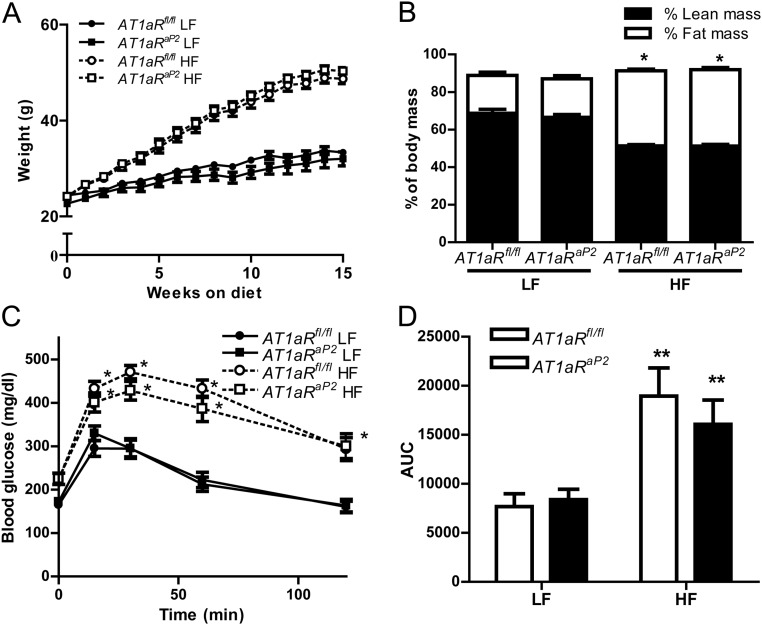

HF-fed mice of each genotype had significantly increased body weight and fat mass compared with LF-fed controls (Fig. 2, A and B). However, adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no significant effect on body weight (Fig. 2A) or fat/lean mass (Fig. 2B) in either LF- or HF-fed mice. Although the mass of retroperitoneal (RPF) and epididymal (EF) adipose tissues were significantly increased by HF feeding, there were no significant effects of genotype in either diet group (Table 1). Physical activity was reduced in HF-fed mice of each genotype, with no significant differences between genotypes (Table 1). Glucose tolerance was significantly impaired in HF-fed mice of each genotype compared with LF-fed controls (Fig. 2, C and D). However, adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no significant effect on glucose tolerance in either LF- or HF-fed mice. Similarly, although HF feeding significantly impaired insulin tolerance tests in both genotypes, there were no significant differences in insulin tolerance between LF or HF AT1aRaP2 mice compared with AT1aRfl/fl controls on respective diets (Supplemental Fig. 2). Plasma insulin and leptin concentrations were increased significantly by HF feeding in mice of each genotype, but there were no significant differences between genotypes in either diet group (Table 1). Plasma concentrations of NEFA were not significantly influenced by diet or genotype (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Deficiency of AT1aR in adipocytes had no effect on development of obesity or obesity-associated glucose intolerance. A, Body weight over 15 wk of LF or HF feeding in mice of each genotype. Beginning at wk 3, HF-fed mice of each genotype had significantly increased body weight compared with LF-fed controls. B, Fat and lean mass (% body weight) of AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice fed LF or HF diets for 16 wk. C, Blood glucose concentrations at selected time points after a bolus of glucose (time 0) in AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice fed a LF or HF diet for 15 wk. D, Area under the curve (AUC) (arbitrary units) quantification of blood glucose concentrations shown in C. Data are represented as mean ± sem from n = 9–12 mice/group. *, P < 0.05 or **, P < 0.001 compared with LF within genotype.

Table 1.

Effects of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency on body parameters of LF- and HF-fed mice

| LF |

HF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1aRfl/fl | AT1aRaP2 | AT1aRfl/fl | AT1aRaP2 | |

| EF mass (g) | 1.01 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.21 | 1.66 ± 0.07a | 1.54 ± 0.06a |

| RPF mass (g) | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 1.46 ± 0.06a | 1.46 ± 0.13a |

| Heart mass (g) | 0.15 ± 0.003 | 0.15 ± 0.005 | 0.18 ± 0.01a | 0.19 ± 0.01a |

| Heart rate (bpm; 24 h mean) | 568 ± 7 | 568 ± 15 | 597 ± 9a | 604 ± 10a |

| Activity (counts/min; 24 h average) | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.4a | 4.6 ± 0.4a |

| Plasma leptin (ng/ml) | 11.8 ± 2.2 | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 56.0 ± 1.5a | 49.5 ± 3.5a |

| Plasma insulin (ng/ml) | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.26 | 1.06 ± 0.19a | 1.96 ± 0.42a |

| Plasma NEFA (mEq/liter) | 1.38 ± 0.14 | 1.47 ± 0.12 | 1.51 ± .21 | 1.40 ± 0.27 |

| Plasma renin concentration (AngI) | 20.2 ± 7.4 | 24.9 ± 8.7 | 7.12 ± 1.7a | 10.4 ± 2.6a |

| Plasma angiotensinogen (nmol/liter) | 2.42 ± 0.13 | 2.02 ± 0.13 | 3.73 ± 0.26a | 3.85 ± 0.28a |

Animals were fasted for 4 h before killing. Values are means ± sem (n = 7–15 per group). EF, Epididymal fat; RPF, retropentoneal fat.

Effect of diet, P < 0.05.

Systolic blood pressures during the day and night cycle were increased significantly in HF-fed mice of each genotype compared with LF-fed controls (P < 0.05) (Supplemental Fig. 3). However, adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no significant effect on systolic blood pressure in either LF or HF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice compared with AT1aRfl/fl controls. Heart mass and rate were significantly increased in HF-fed mice of each genotype compared with LF-fed controls, but there were no significant differences between genotypes (Table 1). Because previous studies demonstrated systemic regulation of components of the RAS in HF-fed mice (27), we quantified plasma concentrations of renin and angiotensinogen. Plasma angiotensinogen concentrations were increased significantly in HF-fed AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice compared with LF-fed groups, with no differences between genotypes (Table 1). Conversely, plasma renin concentrations were decreased significantly in HF-fed AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice compared with LF-fed groups, with no differences between genotypes (Table 1).

Because adipocytes also express AT2R, which have been proposed to contribute to obesity development in mice (29), we quantified mRNA abundance of AT2R and AT1bR in adipose tissue from mice of each genotype. In AT1aRfl/fl controls, AT2R mRNA abundance was increased significantly in visceral adipose tissue from HF-fed mice compared with LF-fed controls (Supplemental Fig. 4A). However, there was no significant effect of AT1aR deficiency in adipocytes on AT2R mRNA abundance in either visceral or sc adipose tissues of LF- or HF-fed mice. Similarly, AT1bR mRNA abundance was not significantly influenced by diet or genotype in visceral or sc adipose tissue (Supplemental Fig. 4B).

Adipocyte AT1aR deficiency resulted in striking adipocyte hypertrophy in LF-fed mice

In visceral retroperitoneal and in sc adipose tissue from LF-fed mice, adipocyte AT1aR deficiency resulted in a greater number of large adipocytes (Fig. 3, A–C, and Supplemental Fig. 5, A–D). Mean adipocyte size in retroperitoneal adipose tissue sections from LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice (2925 ± 361 μm2) was increased significantly compared with adipocyte size in AT1aRfl/fl controls (1328 ± 146 μm2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). Notably, the size of adipocytes from retroperitoneal adipose tissue sections of LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice was similar to adipocyte sizes in HF-fed AT1aRfl/fl controls. However, despite the increase in adipocyte size, adipose tissue mass was not increased significantly in LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice compared with AT1aRfl/fl controls (Table 1). Similar findings were observed in sc adipose tissue sections from LF-fed AT1aRaP2 compared with AT1aRfl/fl mice (Supplemental Fig. 5, A–D). Increases in adipocyte size in retroperitoneal and sc adipose tissue sections from LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice resulted in a significant reduction in the number of adipocytes within a measurement frame compared with cell numbers in sections from LF-fed AT1aRfl/fl controls (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. 5D). In retroperitoneal adipose tissue sections of HF-fed AT1aRfl/fl mice, mean adipocyte size increased significantly compared with LF-fed controls (Fig. 3C). However, there was no significant effect of HF feeding on adipocyte size in retroperitoneal adipose tissue sections from AT1aRaP2 mice (Fig. 3C). In sc adipose tissue sections, adipocyte size increased significantly in HF-fed mice of each genotype compared with LF-fed groups (Supplemental Fig. 5C). However, there were no significant differences in adipocyte sizes within sc adipose tissue sections from HF-fed AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice.

Fig. 3.

Adipocyte AT1aR deficiency resulted in striking adipocyte hypertrophy in visceral retroperitoneal adipose tissue sections from LF-fed mice. A, Histograms of adipocyte number of selected areas quantified in adipose tissue sections using image analysis software (sections from n = 3 mice/group and three image fields per section) from LF-fed (left) or HF-fed mice (right). B, Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections of retroperitoneal visceral adipose tissue used for quantification of adipocyte sizes from LF-fed (left) or HF-fed mice (right) of each genotype. Scale bar, 200 μm. C, Quantification of mean adipocyte area. D, Quantification of adipocyte number per measurement frame. Data are represented as mean ± sem from n = 9 mice/group. *, P < 0.005 compared with LF within genotype; **, P < 0.05 compared with AT1aRfl/fl within diet group.

Deficiency of AT1aR in adipocytes decreased differentiation of SVC to adipocytes, whereas AngII promoted differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes

Increases in adipocyte size from LF-fed mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency could result from reductions in lipolysis, alterations in lipid synthesis and/or uptake, or from decreased capacity of preadipocytes to differentiate to adipocytes. Plasma NEFA were not different between LF-fed mice of each genotype, suggesting that lipolysis was not influenced by adipocyte AT1aR deficiency. We examined the ability of preadipocytes within SVC isolated from mice of each genotype to differentiate into mature adipocytes. AT1aR mRNA abundance was significantly decreased in adipocytes (d 8) differentiated from SVC of AT1aRaP2 mice compared with AT1aRfl/fl controls (AT1aRfl/fl, 0.30 ± 0.02; AT1aRaP2, 0.16 ± 0.01 AT1aR/18S RNA ratio; P < 0.001). Deficiency of AT1aR resulted in significantly reduced ORO staining on d 8 of differentiation compared with SVC differentiated from AT1aRfl/fl controls (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A). In addition, mRNA abundance of PPARγ was significantly decreased in adipocytes differentiated from AT1aRaP2 mice compared with AT1aRfl/fl controls (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Reductions in ORO staining occurred in the absence of changes in mRNA abundance of either fatty acid synthase or CD36 (Fig. 4, C and D, respectively). Conversely, incubation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with AngII throughout the differentiation protocol significantly increased ORO staining and mRNA abundance of PPARγ in mature adipocytes (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4, E and F, respectively, and Supplemental Fig. 6). AngII-mediated increases in PPARγ mRNA abundance were abolished when 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated with the AT1R antagonist, losartan (Fig. 4F). However, incubation of preadipocytes with losartan in the absence of AngII had no significant effect on PPARγ mRNA abundance in differentiated adipocytes.

Fig. 4.

Deficiency of AT1aR reduced differentiation of SVC to adipocytes, whereas AngII promotes differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. A, ORO staining (absorbance measured at 510 nm) of adipocytes differentiated from SVC of AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice. Data are represented as mean ± sem from n = 3–5 samples/genotype. PPARγ (B), fatty acid synthase (C), and CD36 (D) mRNA abundance in adipocytes (d 8) differentiated from SVC of AT1aRfl/fl and AT1aRaP2 mice. Data are mean ± sem from n = 8–11 samples/group. E, ORO staining of 3T3-L1 adipocytes differentiated in the absence (vehicle) or presence of AngII (1 μm). F, PPARγ mRNA abundance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes differentiated in the absence or presence of AngII, losartan or AngII + losartan (1 μm of each compound). Data are represented as mean ± sem from n = 4–5 samples/group. A–C, *, P < 0.05 compared with AT1aRfl/fl. F and G, *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle (DMEM); **, P < 0.05 compared with AngII.

Discussion

Results from this study demonstrate that adipocyte AT1aR deficiency promotes the development of adipocyte hypertrophy in mice fed a LF diet. The size of adipocytes in visceral adipose tissue from LF-fed mice AT1aRaP2 mice was similar to the size of adipocytes in nontransgenic littermate mice fed a HF diet. However, despite increases in adipocyte size in AT1aRaP2 mice, fat mass was similar in mice of each genotype fed the LF diet. Thus, adipocyte hypertrophy in LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice, in the absence of increases in total adipose tissue mass, was insufficient to promote differences in body weight, glucose tolerance, or blood pressure. Preadipocytes from adipocyte AT1aR-deficient mice demonstrated reduced capacity to differentiate to adipocytes, suggesting that the increased adipocyte size in LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice occurred as a consequence of increased lipid storage in a reduced number of adipocytes. Conversely, incubation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with AngII promoted ORO staining and PPARγ expression in differentiating adipocytes, supporting a role for AngII to promote adipocyte differentiation. Surprisingly, the effects of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency to increase adipocyte cell size in visceral, but not sc, adipose tissue from LF-fed mice were not observed when mice were fed a HF diet. These results suggest that adipocyte AT1aR regulate adipocyte differentiation under lean, but not obese, conditions.

Adipose tissue expresses several components of the RAS necessary to produce and respond to AngII. Results from this study confirm previous reports that murine adipocytes express both AT1aR and AT2R, with low levels of AT1bR (6, 7). Adipocyte AT1R have been suggested to regulate adipocyte differentiation or growth, adipocyte glucose uptake or metabolism, or expression of RAS components in adipocytes (6, 13, 30). Murine models of global genetic AT1aR deletion and systemic administration of angiotensin receptor blockers to rodents have been previously used to study effects of this receptor on the development of obesity (11, 31, 32). Specifically, whole body deficiency of angiotensinogen, renin, or ACE in mice fed standard mouse diet resulted in reduced body weight, fat mass, glucose intolerance, and decreased blood pressure (8–10). In addition, whole body deficiency of angiotensinogen, ACE, AT1aR, or AT2R reduced the development of obesity in mice fed a HF diet (8, 11, 33). Conversely, we have previously demonstrated that deficiency of AT1aR or AT2R in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice fed a high cholesterol/fat diet had no effect on body weight (12). These conflicting data are confounded by an inability to define the cell type(s) responsible for effects of whole body deficiency of individual RAS components. To address the direct role of AngII effects at adipocyte AT1aR, we created mice with deficiency of AT1aR in adipocytes and demonstrate a lack of effect on body weight or fat mass when mice are fed a LF or HF diet. These results demonstrate that previously observed effects of whole body AT1aR deficiency to decrease the development of obesity (11) result from reduced effects of AngII at other cell types. Similarly, because adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no effect on systemic concentrations of synthetic components of the RAS, then previously observed elevations in these RAS components in obese mice (27) do not result from AngII effects at adipocyte AT1aR. Additionally, it is possible that improvements in glucose tolerance and blood pressure observed in mice with whole body AT1aR deficiency (11) are secondary to the previously observed leaner phenotype of these animals, because adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no effect on these obesity-associated parameters.

Because whole body AT2R deficiency has also been reported to reduce the development of obesity (26), albeit with conflicting results (12), a possible explanation for the lack of effect of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency on the development of obesity may be compensation by this or other AngII receptors in adipocytes. In the present study, quantification of mRNA abundance of AT1bR and AT2R from whole adipose tissue lysates did not reveal transcriptional up-regulation of either receptor to compensate for the loss of adipocyte AT1aR. Thus, it is unlikely that effects of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency were masked by compensation through AngII effects at other receptor subtypes.

A surprising finding from this study was that AT1aRaP2 mice have large visceral and sc adipocytes when fed a LF diet. Quantification of mean adipocyte size indicated that the magnitude of adipocyte hypertrophy in visceral adipose tissue sections from LF AT1aRaP2 mice was similar to the hypertrophy observed in HF-fed control mice. Despite this striking increase in adipocyte size, there were no differences in fat mass between genotypes on LF diet. The finding of similar fat masses in LF-fed mice of each genotype, despite marked adipocyte hypertrophy in AT1aRaP2 mice, suggests that a smaller number of adipocytes in LF AT1aRaP2 mice accumulated more lipid to maintain adipose mass at a similar level between genotypes. In accordance with the lack of an effect on fat mass, there was no evidence of glucose intolerance, and no changes in plasma insulin or leptin concentrations in LF-fed AT1aRaP2 mice, signifying that in lean mice, adipocyte hypertrophy alone is insufficient to alter levels of these proteins associated with an obese phenotype. Notably, HF feeding resulted in a further increase in adipocyte size in sc, but not visceral, adipose tissue from AT1aRaP2 mice. A lack of increase in the size of visceral adipocytes upon HF feeding in mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency suggests either that adipocyte lipid storage capacity and/or size had reached a maximum extent or that deficiency of AT1aR on adipocytes prevented HF-induced elevations in adipocyte size. Given that adipocytes within sc adipose tissue from AT1aRaP2 mice exhibited a further increase in size upon HF feeding, these results suggest that maximal lipid storage capacity in visceral adipose tissue most likely accounted for a lack of further increase in adipocyte size in this adipose depot upon HF feeding.

Adipocyte hypertrophy in LF-fed mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency could result from several mechanisms, including reduced lipolysis, reduced numbers of adipocytes (with remaining adipocytes filling up with lipid), or increased lipid synthesis or uptake in resident adipocytes. Because plasma concentrations of NEFA were not different in LF-fed mice of either genotype, lipolysis was most likely not influenced by AT1aR deficiency in adipocytes. The literature on AngII regulation of lipolysis is conflicting, with some reports demonstrating minimal effects of AngII on adipose tissue lipolysis in humans (34), compared with reductions in lipolysis of human adipose tissue in response to AngII in normal weight (35) and obese subjects (36). In this study, mRNA abundance of fatty acid synthase and CD36 were not altered in AT1aR-deficient adipocytes, suggesting that reduced synthesis and/or uptake of lipids most likely did not contribute to differences in ORO staining. Others have reported that AngII induces fatty acid synthase expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. However, it was unclear whether these effects were through AT1aR or AT2R (18), and little has been reported regarding regulation of CD36 by AngII in adipocytes.

Because our data did not support changes in lipid uptake, mobilization, and/or synthesis in adipose tissue from LF-fed mice with adipocyte AT1aR deficiency, we focused on adipocyte differentiation as a potential mechanism contributing to hypertrophy of remaining adipocytes. Indeed, preadipocytes isolated from mice lacking adipocyte AT1aR differentiated ex vivo had reduced lipid accumulation and PPARγ mRNA abundance, indicating a reduced capacity for differentiation. Results from this study conflict with those of Kouyama et al. (11), who examined mouse embryonic fibroblasts isolated from wild-type and whole body AT1aR-deficient mice and found no difference in their ability to differentiate into adipocytes. Differences between results from these studies may reflect the differences between culture systems (i.e. preadipocytes from the SVF compared with mouse embryonic fibroblasts). In addition, results from this study demonstrate that previously observed protection against the development of obesity in whole body AT1aR-deficient mice occurred independent of adipocyte AT1aR.

Our results demonstrate that AngII promotes differentiation of murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes in an AT1R-dependent manner. Several in vitro experiments using adipocyte cell lines have implicated a role for AngII in lipid accumulation and differentiation of adipocytes, with conflicting results. Initial studies from Darimont et al. (6) demonstrated that AngII promoted adipocyte differentiation of Ob1771 mouse adipocytes by eliciting prostacyclin from mature adipocytes via AT2R. In another study, AngII increased glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-positive, lipid-containing cells in mouse adipose tissue explants, although the roles of specific AngII receptors were not investigated (19). A proadipogenic effect of AngII was confirmed in 3T3-L1 and human adipocyte primary cells where AngII increased triglyceride content, fatty acid synthase activity, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, and lipid accumulation, although in these studies, both AT1R and AT2R antagonists abolished AngII-induced effects (18, 37). Other reports, however, indicate that AngII decreased lipid content as well as PPARγ and fatty acid synthase in 3T3-L1 and isolated human adipocytes (21–23). Although discrepancies in the literature may be due to the variety of culture systems, sources of adipocytes, differentiation cocktails, and experiment durations used by each group, this field of research is also complicated by the AT1R-independent stimulation of PPARγ by some AT1R antagonists (24, 38, 39). For example, Wistar Kyoto rats administered candesartan exhibited increased expression of PPARγ expression in adipose tissue and consequently had a larger number of small adipocytes (31). Similar results have been reported with telmisartan and irbesartan (25, 32, 40). It would be interesting in future studies to examine effects of AT1R antagonists with PPARγ-stimulating properties in AT1aR-deficient adipocytes to better define the AT1R-independent effect of this class of compounds.

In conclusion, adipocyte AT1aR deficiency had no effect on development of obesity or obesity-induced hypertension and dysregulated glucose homeostasis. However, in lean mice, deficiency of AT1aR in adipocytes promoted striking adipocyte hypertrophy in visceral and sc adipose tissue, without the negative consequences typically associated with this phenotype. Mechanisms for effects of adipocyte AT1aR deficiency include reductions in differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes, resulting in increased lipid accumulation across a smaller number of adipocytes in LF-fed mice. Conversely, AngII promoted the differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes through an AT1R-dependent mechanism. These results demonstrate that AngII acts at adipocyte AT1aR to regulate adipose tissue growth in lean mice, which may have implications in diseases associated with cachexia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the skillful technical assistance of Dr. Wendy Katz for embedding and sectioning adipose tissue and Ms. Debra Rateri for assistance with the development of AT1aRaP2 mice.

This work was supported by AHA Predoctoral Fellowship 11PRE6760002 (to K.P.) and National Institutes of Health Grants T32 HL072743 (to K.P., L.A.C., and A.D.), HLBI R0173085 (to L.A.C.), and P20 GM103527.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ACE

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AngII

- angiotensin II

- AT1aR

- angiotensin type 1a receptor

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- HF

- high fat

- LF

- low fat

- NEFA

- nonesterified fatty acid

- ORO

- Oil Red O

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RAS

- renin-angiotensin system

- SVC

- stromal vascular cell

- WAT

- white adipose tissue.

References

- 1. Bader M, Ganten D. 2008. Update on tissue renin-angiotensin systems. J Mol Med 86:615–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zorad S, Fickova M, Zelezna B, Macho L, Kral JG. 1995. The role of angiotensin II and its receptors in regulation of adipose tissue metabolism and cellularity. Gen Physiol Biophys 14:383–391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cassis LA, Fettinger MJ, Roe AL, Shenoy UR, Howard G. 1996. Characterization and regulation of angiotensin II receptors in rat adipose tissue. Angiotensin receptors in adipose tissue. Adv Exp Med Biol 396:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Kreutz R, Runkel N, Distler A, Sharma AM. 1999. Co-expression of renin-angiotensin system genes in human adipose tissue. J Hypertens 17:555–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crandall DL, Herzlinger HE, Saunders BD, Armellino DC, Kral JG. 1994. Distribution of angiotensin II receptors in rat and human adipocytes. J Lipid Res 35:1378–1385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darimont C, Vassaux G, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. 1994. Differentiation of preadipose cells: paracrine role of prostacyclin upon stimulation of adipose cells by angiotensin-II. Endocrinology 135:2030–2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burson JM, Aguilera G, Gross KW, Sigmund CD. 1994. Differential expression of angiotensin receptor 1A and 1B in mouse. Am J Physiol 267:E260–E267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Massiera F, Seydoux J, Geloen A, Quignard-Boulange A, Turban S, Saint-Marc P, Fukamizu A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Teboul M. 2001. Angiotensinogen-deficient mice exhibit impairment of diet-induced weight gain with alteration in adipose tissue development and increased locomotor activity. Endocrinology 142:5220–5225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takahashi N, Li F, Hua K, Deng J, Wang CH, Bowers RR, Bartness TJ, Kim HS, Harp JB. 2007. Increased energy expenditure, dietary fat wasting, and resistance to diet-induced obesity in mice lacking renin. Cell Metab 6:506–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jayasooriya AP, Mathai ML, Walker LL, Begg DP, Denton DA, Cameron-Smith D, Egan GF, McKinley MJ, Rodger PD, Sinclair AJ, Wark JD, Weisinger HS, Jois M, Weisinger RS. 2008. Mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzyme have increased energy expenditure, with reduced fat mass and improved glucose clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:6531–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kouyama R, Suganami T, Nishida J, Tanaka M, Toyoda T, Kiso M, Chiwata T, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Fukamizu A, Horiuchi M, Hirata Y, Ogawa Y. 2005. Attenuation of diet-induced weight gain and adiposity through increased energy expenditure in mice lacking angiotensin II type 1a receptor. Endocrinology 146:3481–3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Lu H, Inagami T, Cassis LA. 2004. Hypercholesterolemia stimulates angiotensin peptide synthesis and contributes to atherosclerosis through the AT1A receptor. Circulation 110:3849–3857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lu H, Boustany-Kari CM, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. 2007. Angiotensin II increases adipose angiotensinogen expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E1280–E1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brink M, Wellen J, Delafontaine P. 1996. Angiotensin II causes weight loss and decreases circulating insulin-like growth factor I in rats through a pressor-independent mechanism. J Clin Invest 97:2509–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cassis LA, Marshall DE, Fettinger MJ, Rosenbluth B, Lodder RA. 1998. Mechanisms contributing to angiotensin II regulation of body weight. Am J Physiol 274:E867–E876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cabassi A, Coghi P, Govoni P, Barouhiel E, Speroni E, Cavazzini S, Cantoni AM, Scandroglio R, Fiaccadori E. 2005. Sympathetic modulation by carvedilol and losartan reduces angiotensin II-mediated lipolysis in subcutaneous and visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2888–2897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Kloet AD, Krause EG, Scott KA, Foster MT, Herman JP, Sakai RR, Seeley RJ, Woods SC. 2011. Central angiotensin II has catabolic action at white and brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301:E1081–E1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones BH, Standridge MK, Moustaid N. 1997. Angiotensin II increases lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 and human adipose cells. Endocrinology 138:1512–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saint-Marc P, Kozak LP, Ailhaud G, Darimont C, Negrel R. 2001. Angiotensin II as a trophic factor of white adipose tissue: stimulation of adipose cell formation. Endocrinology 142:487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schling P, Löffler G. 2001. Effects of angiotensin II on adipose conversion and expression of genes of the renin-angiotensin system in human preadipocytes. Horm Metab Res 33:189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janke J, Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Luft FC, Sharma AM. 2002. Mature adipocytes inhibit in vitro differentiation of human preadipocytes via angiotensin type 1 receptors. Diabetes 51:1699–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saiki A, Koide N, Watanabe F, Murano T, Miyashita Y, Shirai K. 2008. Suppression of lipoprotein lipase expression in 3T3-L1 cells by inhibition of adipogenic differentiation through activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Metabolism 57:1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fuentes P, Acuña MJ, Cifuentes M, Rojas CV. 2010. The anti-adipogenic effect of angiotensin II on human preadipose cells involves ERK1,2 activation and PPARG phosphorylation. J Endocrinol 206:75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T, Kintscher U. 2004. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activity. Circulation 109:2054–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Janke J, Schupp M, Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Boschmann M, Sauma L, Nystrom FH, Jordan J, Luft FC, Sharma AM. 2006. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonists induce human in-vitro adipogenesis through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation. J Hypertens 24:1809–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, Balakrishnan A, Owens AP, 3rd, Howatt DA, Subramanian V, Poduri A, Charnigo R, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. 2011. Endothelial cell-specific deficiency of Ang II type 1a receptors attenuates Ang II-induced ascending aortic aneurysms in LDL receptor−/− mice. Circ Res 108:574–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gupte M, Boustany-Kari CM, Bharadwaj K, Police S, Thatcher S, Gong MC, English VL, Cassis LA. 2008. ACE2 is expressed in mouse adipocytes and regulated by a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295:R781–R788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodbell M. 1964. Localization of lipoprotein lipase in fat cells of rat adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 239:753–755 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yvan-Charvet L, Even P, Bloch-Faure M, Guerre-Millo M, Moustaid-Moussa N, Ferre P, Quignard-Boulange A. 2005. Deletion of the angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) reduces adipose cell size and protects from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 54:991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Juan CC, Chien Y, Wu LY, Yang WM, Chang CL, Lai YH, Ho PH, Kwok CF, Ho LT. 2005. Angiotensin II enhances insulin sensitivity in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 146:2246–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zorad S, Dou JT, Benicky J, Hutanu D, Tybitanclova K, Zhou J, Saavedra JM. 2006. Long-term angiotensin II AT(1) receptor inhibition produces adipose tissue hypotrophy accompanied by increased expression of adiponectin and PPAR-γ. Eur J Pharmacol 552:112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muñoz MC, Giani JF, Dominici FP, Turyn D, Toblli JE. 2009. Long-term treatment with an angiotensin II receptor blocker decreases adipocyte size and improves insulin signaling in obese Zucker rats. J Hypertens 27:2409–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Premaratna SD, Manickam E, Begg DP, Rayment DJ, Hafandi A, Jois M, Cameron-Smith D, Weisinger RS. 2012. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition reverses diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and inflammation in C57BL/6J mice. Int J Obes 36:233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Townsend RR. 2001. The effects of angiotensin-II on lipolysis in humans. Metabolism 50:468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boschmann M, Ringel J, Klaus S, Sharma AM. 2001. Metabolic and hemodynamic response of adipose tissue to angiotensin II. Obes Res 9:486–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goossens GH, Blaak EE, Arner P, Saris WH, van Baak MA. 2007. Angiotensin II: a hormone that affects lipid metabolism in adipose tissue. Int J Obes 31:382–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hung WW, Hsieh TJ, Lin T, Chou PC, Hsiao PJ, Lin KD, Shin SJ. 2011. Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system ameliorates apelin production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 25:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benson SC, Pershadsingh HA, Ho CI, Chittiboyina A, Desai P, Pravenec M, Qi N, Wang J, Avery MA, Kurtz TW. 2004. Identification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPARγ-modulating activity. Hypertension 43:993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rong X, Li Y, Ebihara K, Zhao M, Naowaboot J, Kusakabe T, Kuwahara K, Murray M, Nakao K. 2010. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-independent beneficial effects of telmisartan on dietary-induced obesity, insulin resistance and fatty liver in mice. Diabetologia [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Souza-Mello V, Gregório BM, Cardoso-de-Lemos FS, de Carvalho L, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. 2010. Comparative effects of telmisartan, sitagliptin and metformin alone or in combination on obesity, insulin resistance, and liver and pancreas remodelling in C57BL/6 mice fed on a very high-fat diet. Clin Sci 119:239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.