Abstract

Substance P (SP), a neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R) agonist, is mainly produced and stored in primary sensory nerves and, upon its release, participates in cardiovascular and renal functional regulation. This study tests the hypothesis that activation of the NK-1Rs by SP occurs during hypertension induced by deoxycorticosterone (DOCA)-salt treatment, which contributes to renal injury in this model. C57BL/6 mice were subjected to uninephrectomy and DOCA-salt treatment in the presence or absence of administration of selective NK-1 antagonists, L-733,060 (20 mg/kg·d, ip) or RP-67580 (8 mg/kg·d, ip). Five weeks after the treatment, mean arterial pressure determined by the telemetry system increased in DOCA-salt mice but without difference between NK-1R antagonist-treated or NK-1R antagonist-untreated DOCA-salt groups. Plasma SP levels were increased in DOCA-salt compared with control mice (P < 0.05). Renal hypertrophy and increased urinary 8-isoprostane and albumin excretion were observed in DOCA-salt compared with control mice (P < 0.05). Periodic acid-Schiff and Masson's trichrome staining showed more severe glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial injury in the renal cortex in DOCA-salt compared with control mice, respectively (P < 0.05). Hydroxyproline assay and F4/80-staining showed that renal collagen levels and interstitial monocyte/macrophage infiltration were greater in DOCA-salt compared with control mice, respectively (P < 0.05). Blockade of the NK-1R with L-733,060 or RP-67580 in DOCA-salt mice suppressed increments in urinary 8-isoprostane and albumin excretion, interstitial monocyte/macrophage infiltration, and glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial injury and fibrosis (P < 0.05). Thus, our data show that blockade of the NK-1Rs alleviates renal functional and tissue injury in the absence of alteration in blood pressure in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. The results suggest that elevated SP levels during DOCA-salt hypertension play a significant role contributing to renal damage possibly via enhancing oxidative stress and macrophage infiltration of the kidney.

Hypertension is a leading risk factor for the development and progression of chronic renal and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension-induced renal injury is characterized by glomerular sclerosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis. Clinical studies have shown that patients with salt-sensitive hypertension are at a significantly high risk for the development of hypertensive end-organ damage, including renal injury (1). Although multiple factors, including endothelin-1, angiotensin II, aldosterone, oxidative stress, and proinflammatory cytokines, have been suggested to mediate renal damage associated with salt-sensitive hypertension (2, 3), precise mechanisms with clearly defined molecular targets for intervention to prevent salt-induced renal damage remain to be delineated.

It is well established that the cardiovascular system and the kidney are innervated by sensory nerve terminals that contain various neuropeptides, e.g. calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) (4), which may modulate cardiovascular and renal function. Indeed, sodium excretion in response to sodium loading is impaired in salt-sensitive hypertension induced by surgical sensory denervation or by sensory nerve degeneration after neonatal capsaicin treatment (5, 6). In addition, blockade of CGRP receptors elevated blood pressure in rats fed a high-salt, but not normal-salt, diet, suggesting that high-salt intake may activate sensory nerves, leading to release of sensory neuropeptides including CGRP and SP (7, 8).

SP is one of five members of the tachykinin family that includes neurokinin A, neuropeptide K, neuropeptide γ, and neurokinin B in addition to SP. The effectors of tachykinins on target cells contain three specific receptors: the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1R), NK-2R, and NK-3R. Each tachykinin appears to activate a distinct tachykinin receptor. The NK-1R may be activated preferentially by SP (9). SP may act as a neurotransmitter or pain mediator when released from both central and peripheral endings of primary sensory neurons or from various inflammatory cells (9, 10). In the central nervous system, SP is thought to participate in various behavioral responses. In the peripheral system, SP may regulate cardiovascular and renal function upon being released from sensory nerves innervating these organs/tissues (4). However, the effect of SP on hypertension-induced renal damage remains to be delineated.

In the present study, we aimed to study the importance of SP in mediating renal injury induced by deoxycorticosterone (DOCA)-salt hypertension. To this end, we induced salt-sensitive hypertension in mice by treating them with DOCA and salt and studied the effect of chronic NK-1R blockade using specific NK-1R antagonists, L-733,060 and RP-67580, on renal injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Ten-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA), were used in this study. The mice were housed at 21 C with 12-h light, 12-h dark cycles and fed a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum. After acclimatizing, the mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups subjected to experimental protocols that were approved by the Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee.

Telemetry blood pressure assay

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were determined using the telemetry system (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) following the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (80 and 4 mg/kg, sc, respectively), and the transmitter catheter was implanted into the left carotid artery with the transmitter body placed sc in the lower right hand side of the abdomen. The mice were returned to their individual cages and allowed for recovery for 3 d before starting of the radiotelemetric recording.

Experimental protocol

One week after the baseline radiotelemetric recording, DOCA-salt hypertension was induced as described previously (11). In brief, the left kidney was removed through a dorsal flank incision under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia as described above. The DOCA pellets [24 mg/10 g body weight (BW); Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL] were implanted in the midscapular region. Mice receiving DOCA were given 1% NaCl and 0.2% KCl to drink, and treatment with DOCA-salt continued for 5 wk. Mice undergoing uninephrectomy without receiving DOCA and saline served as controls. To determine the effect of SP on DOCA-salt-induced renal injury, mice receiving DOCA and saline were ip injected vehicle, the NK-1R antagonist L-733,060 (20 mg/kg·d), or RP-67580 (8 mg/kg·d) for 5 wk. L-733,060 and RP-67580 were purchased from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO). The doses of L-733,060 and RP-67580 have previously been shown to effectively block SP-mediated inflammatory reactions (12–14). L-733,060 and RP67580 were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide to give a stock solution and further diluted (1:10) in normal saline containing 10% Tween 80/10% dimethylsulfoxide. Experimental groups (n = 6–8 per group) included 1) control mice receiving tap water and vehicle injection; 2) DOCA-salt + vehicle; 3) DOCA-salt + L-733,060; and 4) DOCA-salt + RP-67580. The mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia for 24 h after surgery, and radiotelemetric recording continued for an additional 5 wk. At the end of 5 wk of treatment, mice were placed in mouse metabolic cages for 24-h urine collection. Plasma and kidney were then harvested, weighted, and stored at −80 C for biochemical analysis or fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution in phosphate buffer for histological analysis.

Plasma and urine analysis

Plasma and urine creatinine concentrations were assayed by the use of an improved Jaffe creatinine assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Urinary albumin was measured with an ELISA kit (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA). Urinary 8-isoprostane levels were determined using the kit from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Histological and morphological analysis

Kidney tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate buffer formalin. Sections of 5 μm of paraffin-embedded tissue were cut and stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) or Mason's trichrome stain. Morphologic evaluation of glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial injury were performed blindly with the use of a light microscopy and assessed semiquantitatively as described previously (3). The glomerulosclerosis index was determined in PAS-stained sections in 50 randomly selected glomeruli per section under ×400 magnification. The tubulointerstitial injury index was assessed in Masson's trichrome-stained sections in 20 fields selected randomly from each kidney at ×200 magnification.

Immunohistochemistry

Renal monocyte/macrophage infiltration was analyzed in tissues embedded in 3-μm-thick paraffin sections obtained 5 wk after the treatment. Kidney sections were incubated with a primary antibody directed to F4/80 (1:200, rat antimouse macrophage monoclonal antibody; Serotec, Oxford, UK) overnight at 4 C. Horse antirat IgG horseradish peroxidase (1:400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was applied and incubated for 1 h at room temperature and visualized by incubating the sections with the substrate vector fast red (Vector Laboratories). Negative control experiments were performed by omitting the primary antibody from the incubation. The quantification of F4/80-positive cells in the cortex was carried out in a blind fashion under ×400 magnification. For each section, 15 randomly selected cortical fields were examined. The number of positive cells was expressed as cells per square millimeter.

Hydroxyproline assay

The collagen content of renal tissue was determined by hydroxyproline assay. Kidney samples were processed as described previously (11). Hydroxyproline content was determined with a colorimetric assay and a standard curve of 0–5 μg of hydroxyproline. Data were expressed as micrograms of collagen per milligram of dry weight, assuming that collagen contains an average of 13.5% hydroxyproline.

Radioimmunoassay

A rabbit antirat SP RIA kit (Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA) was used to determine SP levels in plasma following manufacture's instruction. This antibody has 100% cross-reactivity with rat SP. Cross-reactivity with neurokinin A, neurokinin B, and neuropeptide K is less than 0.01%.

Statistical analysis

All of the values are expressed as means ± se. The significances of differences among groups were analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni's adjustment for multiple comparisons or by an unpaired t test for comparing differences between two groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

As demonstrated in Table 1, there was no significant difference in BW between groups at the end of the experiments. DOCA-salt treatment increased the kidney:BW ratio when compared with control mice (116.3 ± 2.7 vs. 75.7 ± 1.4 mg/10 g of BW; P < 0.05), but no difference was found between DOCA-salt-treated mice with or without the NK-1R antagonists L-733,060 and RP-67580 (P > 0.05). DOCA-salt treatment increased urinary output and sodium excretion when compared with control mice (17.1 ± 2.6 vs. 1.4 ± 0.4 ml/24 h, 1.22 ± 0.45 vs. 0.11 ± 0.05 mmol/24 h; P < 0.05). Although there was a tendency toward higher urinary output and sodium excretion in DOCA-salt mice treated with NK-1R antagonists compared with vehicle-treated DOCA-salt mice, there was no significant difference between these two groups (P > 0.05). There were an elevated level of albumin excretion and a decreased level of creatinine clearance in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice (41.1 ± 3.5 vs. 5.8 ± 0.6 μg/24 h, 128 ± 12 vs. 331 ± 15 ml/24 h; P < 0.05). Administration of the NK-1R antagonists L-733,060 and RP-67580 in DOCA-salt mice reduced the increment of urinary albumin excretion by 37 and 42%, respectively (P < 0.05), and improved creatinine clearance compared with vehicle-treated DOCA-salt mice (226 ± 15 and 217 ± 16 vs.128 ± 12 ml/24 h; P < 0.05). Urinary 8-isoprostane excretion was increased in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice (1.76 ± 0.16 vs. 0.49 ± 0.10 ng/24 h; P < 0.05), and blockade of the NK-1R with L-733,060 and RP-67580 reduced 8-isoprostane excretion compared with vehicle-treated DOCA-salt mice (1.10 ± 0.12 ng/24 h and 1.18 ± 0.10 vs. 1.76 ± 0.16 ng/24 h; P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Biochemical profile of the animals

| Parameter | Control | DOCA + vehicle | DOCA + L-733,060 | DOCA + RP-67580 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 28.6 ± 0.3 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 29.3 ± 0.4 | 28.1 ± 0.4 |

| Kidney weight (mg/10 g of BW) | 75.7 ± 1.4 | 116.3 ± 2.7a | 113.4 ± 3.9a | 111.1 ± 3.3a |

| Urinary output (ml/24 h) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 17.1 ± 2.6a | 22.7 ± 4.5a | 20.1 ± 2.3a |

| Sodium excretion (mmol/24 h) | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.45a | 1.75 ± 0.65a | 1.55 ± 0.61a |

| Urinary albumin (μg/24 h) | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 41.1 ± 3.5a | 25.8 ± 2.3ab | 23.6 ± 1.7ab |

| Urinary 8-isoprostane (ng/24 h) | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 1.76 ± 0.16a | 1.10 ± 0.12ab | 1.18 ± 0.10ab |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/24 h) | 331 ± 15 | 128 ± 12a | 226 ± 15ab | 217 ± 16ab |

Values are means ± se; n = 6–8. Control, DOCA + vehicle, DOCA + L-733,060, and DOCA + RP-67580 indicate control mice and DOCA-salt-treated mice receiving vehicle, L-733,060, or RP-67580, respectively.

P < 0.05 vs. control mice.

P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt-treated mice.

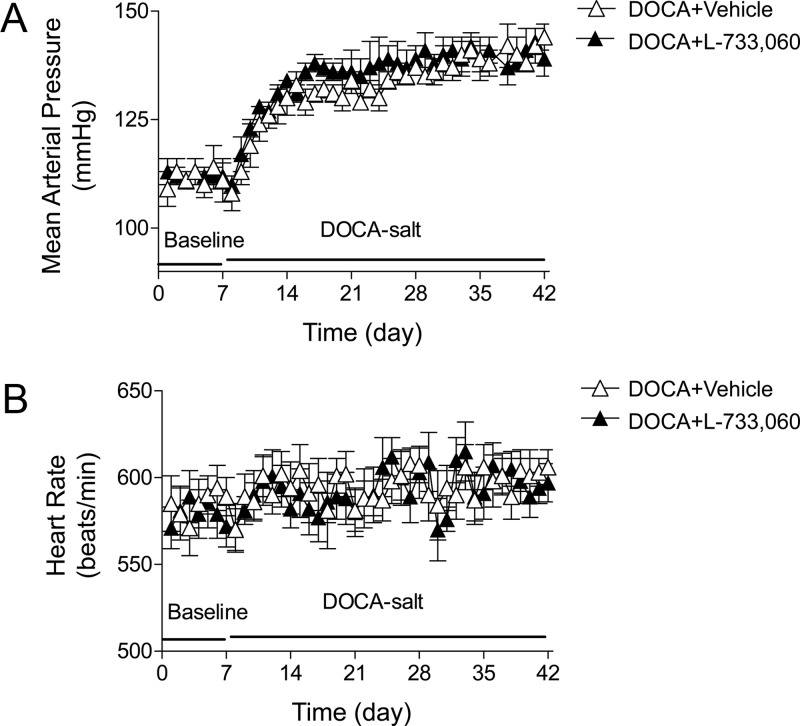

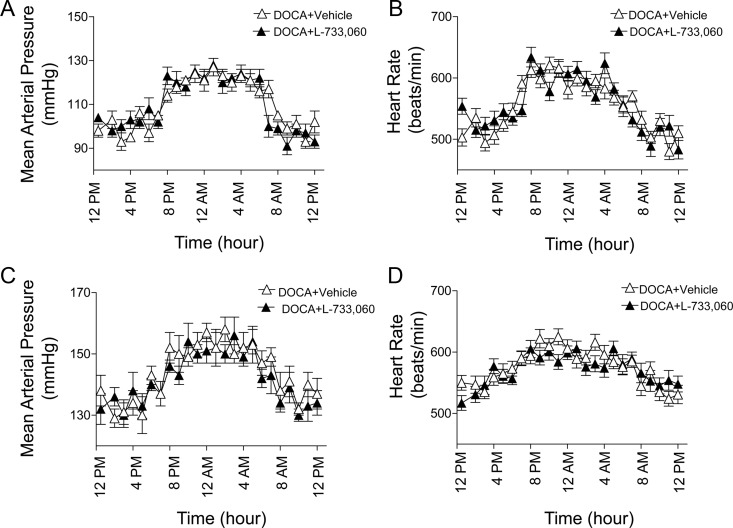

DOCA-salt treatment led to an increase in MAP determined by radiotelemetry (Fig. 1A). One week after DOCA-salt treatment, MAP increased from 109 ± 4 to 128 ± 3 mm Hg and continually increased to 144 ± 3 mm Hg by the end of the 5-wk treatment. Moreover, mice with the blockade of the NK-1R with L-733,060 during DOCA-salt treatment had similar MAP compared with vehicle-treated DOCA-salt mice. Likewise, there was no difference in HR between DOCA-salt mice treated with or without L-733,060 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2, there was no difference in MAP and HR over a 24-h period between DOCA-salt mice treated with and without L-733,060 at 1 d before DOCA-salt treatment (Fig. 2, A and B) or at the end of DOCA-salt treatment (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 1.

Changes in MAP and HR in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice with or without L-733,060 treatment. Graphs representing daily average 24-h MAP (A) and HR (B). Values are means ± se (n = 4).

Fig. 2.

MAP and HR in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice with or without L-733,060 treatment at 1 d before DOCA-salt treatment (A and B) or at the end of DOCA-salt treatment (C and D). Graphs representing MAP and HR over a 24-h period. Values are means ± se (n = 4).

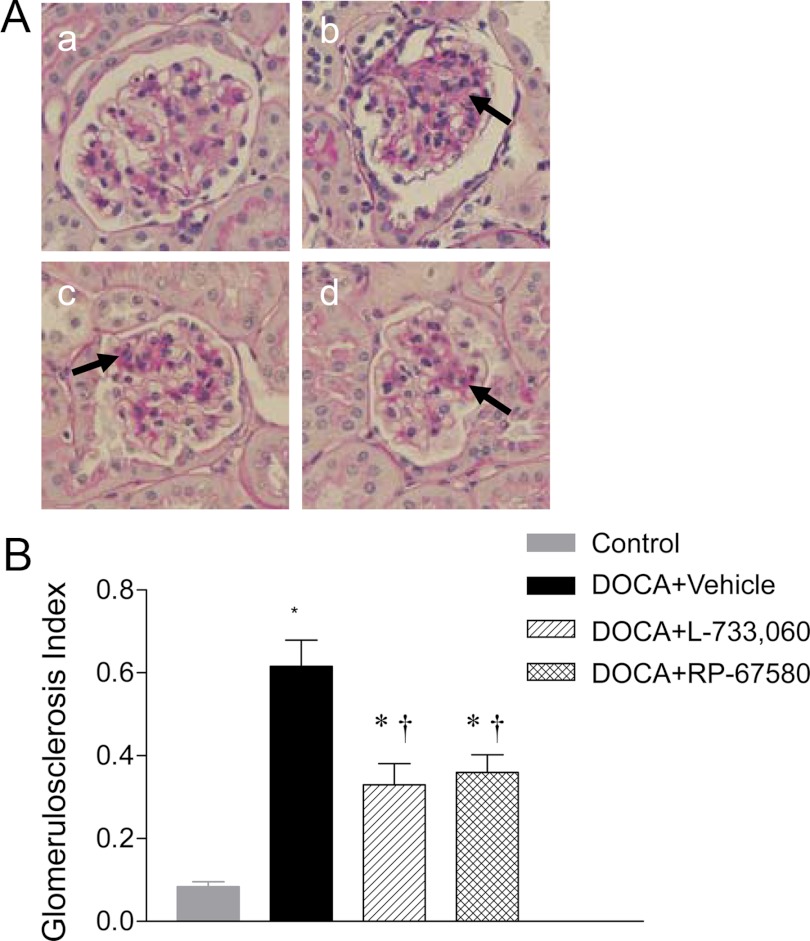

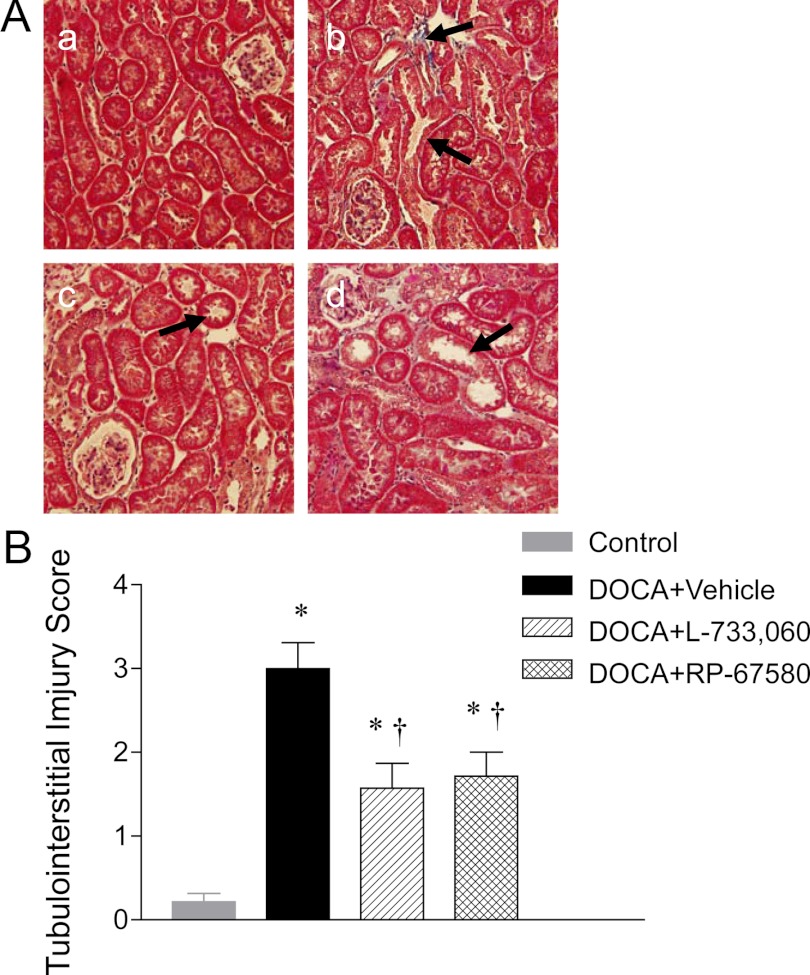

Renal histological injury was determined by semiquantitative morphological analyses executed blindly. As illustrated in Fig. 3, A and B, compared with control mice, DOCA-salt-treated mice exhibited significant glomerulosclerosis and increased glomeruloslerosis index (0.62 ± 0.06 vs. 0.08 ± 0.01; P < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 4A, more severe tubular injury consisting of tubular atrophy/dilation and interstitial fibrosis was found in the kidneys of DOCA-salt-treated mice compared with the kidneys of control mice. Quantitative analysis showed that DOCA-salt treatment increased tubulointerstitial injury scores compared with control mice (3.00 ± 0.30 vs. 0.21 ± 0.10; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). NK-1R blockade with L-733,060 and RP-67580 significantly reduced glomerulosclerosis index (Fig. 3B) and tubulointerstitial injury scores (Fig. 4B) in DOCA-salt mice.

Fig. 3.

Effect of NK-1R antagonists on renal glomerular injury of DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. A, Histological sections stained with PAS stain showing glomerulosclerosis in control (a) and DOCA-salt-treated mice receiving vehicle (b), L-733,060 (c), or RP-67580 (d). The arrows indicate that areas of glomerulosclerosis. Magnification, ×400. B, Quantitative evaluation reveals that effect of L-733,060 and RP-67580 on glomerulosclerosis index in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Values are means ± se (n = 6–8). *, P < 0.05 vs. control mice; †, P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt-treated mice.

Fig. 4.

Effect of NK-1R antagonists on renal cortical tubulointerstitial injury of DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. A, Histological sections stained with Masson's trichrome stain showing renal cortical tubulointerstitial injury in control (a) and DOCA-salt-treated mice receiving vehicle (b), L-733,060 (c), or RP-67580 (d). The arrows indicate that tubular dilation and interstitial fibrosis. Magnification, ×200. B, Quantitative evaluation reveals that effect of L-733,060 and RP-67580 on tubulointerstitial injury score in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Values are means ± se (n = 6–8). *, P < 0.05 vs. control mice; †, P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt-treated mice.

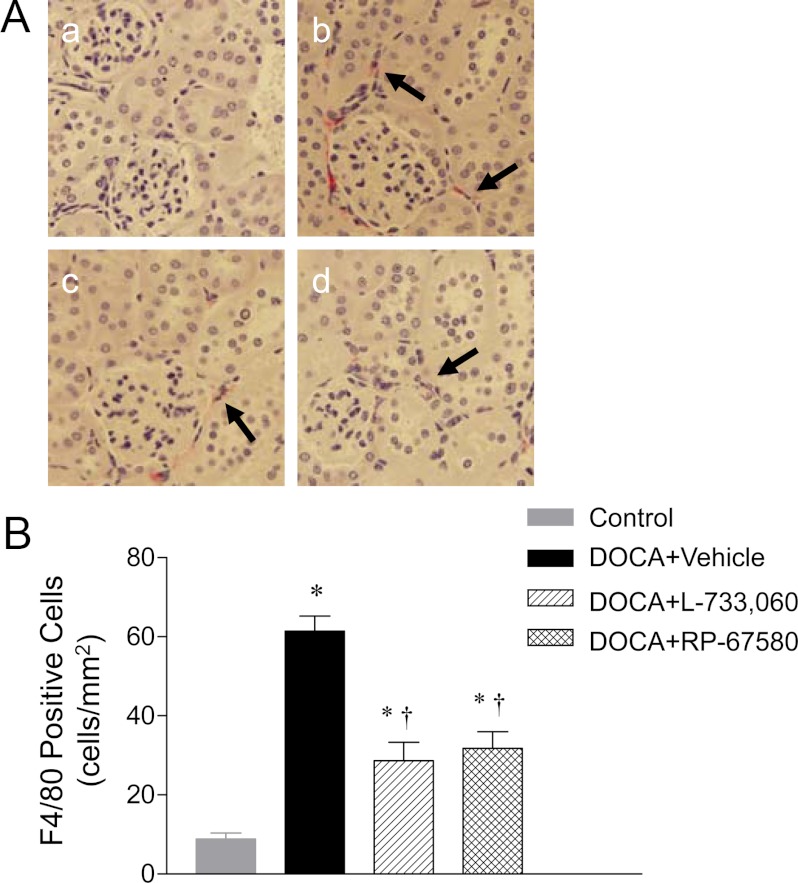

Monocyte/macrophage infiltration was determined and used as an indicator of inflammation in the kidney. The interstitial monocyte/macrophage infiltration was indicated by F4/80-positive cells that stained red. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, A and B, a significant interstitial macrophage infiltration was observed in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice (61 ± 4 vs. 9 ± 2 cells/mm2; P < 0.05). Administration of L-733,060 or RP-67580 significantly reduced interstitial macrophage infiltration induced by DOCA-salt treatment (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effect of NK-1R antagonists on renal cortical interstitial monocyte/macrophage infiltration of DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. A, Immunohistochemically stained sections showing that F4/80-positive cells (monocytes/macrophages in red) in renal cortex from control (a) and DOCA-salt-treated mice receiving vehicle (b), L-733,060 (c), or RP-67580 (d). The arrows indicate that F4/80-positive cells. Magnification, ×400. B, Quantitative evaluation reveals that effect of L-733,060 and RP-67580 on F4/80-positive cells in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Values are means ± se (n = 6–8). *, P < 0.05 vs. control mice; †, P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt-treated mice.

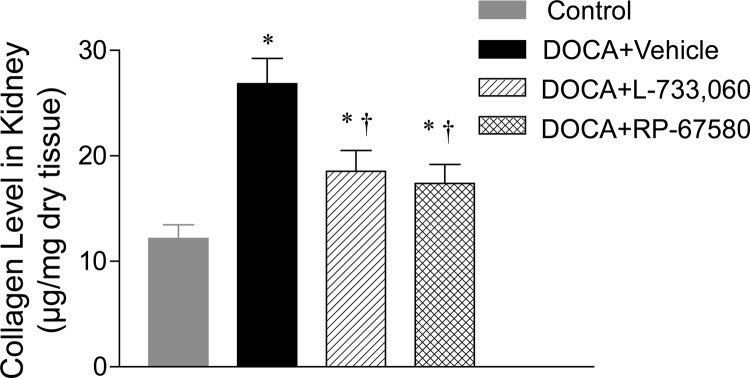

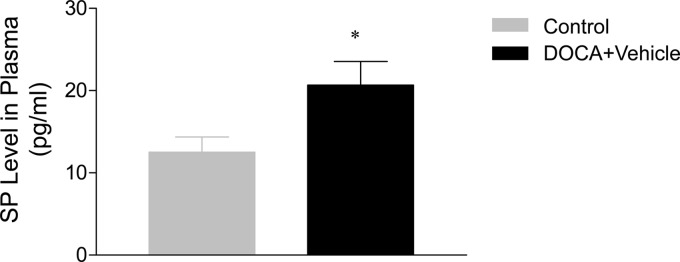

As shown in Fig. 6, renal collagen level determined using hydroxyproline assay was significantly elevated in DOCA-salt-treated mice compared with control mice (26.8 ± 2.4 vs. 12.2 ± 1.3 μg/mg dry tissue; P < 0.05). Blockade of the NK-1R with L-733,060 or RP-67580 markedly reduced the effects of DOCA-salt treatment on renal collagen levels (18.5 ± 2.0 and 17.4 ± 1.8 vs. 26.8 ± 2.4 μg/mg dry tissue; P < 0.05). Finally, Fig. 7 shows that plasma SP levels, the agonist of NK-1R, and a marker of activated primary sensory nerves were significantly increased in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice (20.7 ± 2.9 vs. 12.5 ± 1.8 pg/ml; P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Effect of NK-1R antagonists, including L-733,060 and RP-67580, on renal collagen levels in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Values are means ± se (n = 6–8). *, P < 0.05 vs. control mice; †, P < 0.05 vs. DOCA-salt-treated mice.

Fig. 7.

Effect of DOCA-salt treatment on plasma SP level. Values are means ± se (n = 6–8). *, P < 0.05 vs. control mice.

Discussion

The data from the present study showed that neuropeptide SP may serve as a novel mediator of renal injury in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. The results showed that plasma SP levels were elevated in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Blockade of NK-1R, the primary receptor for SP, alleviated renal injury in the absence of changes in blood pressure. Lessened renal injury by blockade of NK-1R in DOCA-salt mice is evident by 1) improved renal function, including an increase in creatinine clearance and a decrease in urinary albuminuria and urinary 8-isoprostane excretion, and 2) improved renal morphology consisting of ameliorated glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial injury, interstitial monocyte/macrophage infiltration, and collagen deposition. Taken together, the present findings suggest that DOCA-salt hypertension increases the release of SP, leading to aggravated renal injury via activation of the NK-1R in mice.

We found that urinary albumin excretion, an important predictor for the end-stage renal disease, was elevated by about 7-fold in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice. Elevated urinary albumin excretion was accompanied with the similar degree of morphological alterations observed in glomeruli of DOCA-salt mice, i.e. the glomerulosclerosis index elevated about 7-fold in DOCA-salt mice compared with control mice. Previous reports show that urinary albumin increased before renal lesion could be detected by light microscopy (15), a finding plausibly explained by ultrastructural changes, including thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and degenerative changes of podocytes, which preceded light microscopic histological disturbances (16). Indeed, podocyte injury, as a result of elevated blood pressure in DOCA-salt mice, may lead to proteinuria (17). Although MAP determined by radiotelemetry was equally elevated in DOCA-salt mice treated with or without the NK-1R antagonist L-733,060, we could not rule out the possibility that the local hemodynamics in glomeruli were altered when NK-1Rs were blocked, which might contribute to reduced glomerular injury in DOCA-salt mice. Further studies are needed in the future to clarify the issue.

Tachykinin receptors, including NK-1, NK-2, and NK-3, are G protein-coupled receptors. Although SP may activate all three tachykinin receptors, its potency is greatest when binding to the NK-1R subtype (9). It has been shown that the nucleus tractus solitarius, an important regulator of baroreflex, expresses high density of NK-1Rs involving in the transmission of cardiovascular reflexes (18). Moreover, microinjection of SP into the nucleus tractus solitarius increases blood pressure and baroreflex sensitivity (19), providing functional evidence supporting that NK-1R activation or blockade modulates baroreflex control. Furthermore, SP has a direct effect on postganglionic sympathetic nerve activity, evident by the fact that sympathetic ganglia stimulated by SP in situ result in an increase in renal sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure, and HR (20). The increases in these parameters could be attenuated by the selective NK-1R antagonist, GR-82334, suggesting that SP increases postganglionic sympathetic nerve activity via activation of NK-1Rs (20). Taken together, the results suggest that activation of NK-1Rs by SP may modulate sympathetic nerve activity via the central and peripheral mechanisms. However, although catecholamine concentrations were not examined in the present study, there was no indication of altered sympathetic nerve activity by the NK-1 antagonists based on telemetry recording of MAP and HR over the 24-h period. It is likely that endogenously released SP is not sufficient to induce detectable changes in MAP and HR regulated by sympathetic nerves in the face of DOCA-salt hypertension, and thus blockade of SP binding to its receptor would show a lack of changes in the diurnal pattern of MAP and HR. Future studies on NK-1R antagonist-induced renal protection via affecting central or peripheral sympathetic nerve activity are warranted given that enhanced sympathetic nerve activity has been shown to actively participate in the pathogenesis of renal damage in the DOCA-salt model (21).

Tachykinin SP is considered as a key mediator of inflammatory responses and neuroimmune reactions (22). SP elicits local vasodilation and alters vascular permeability, resulting in enhanced delivery and accumulation of leukocytes to tissues for participation of local immune responses (23). SP not only acts as a chemoattractant for leukocytes but also induces chemotaxis of leukocytes (24). In vitro, SP leads to activation of the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor κB and activation of immune cells to produce cytokines (25). In vivo, studies using either NK-1R antagonists or mice genetically deficient in the NK-1R indicate a role of this receptor contributing to asthma and chronic bronchitis, intestinal inflammation, pancreatitis, and resistance to infection (22, 26). Indeed, SP affects migration and cytotoxic effects of leukocytes in such that it prepares leukocytes for an exaggerated inflammatory response (27). Recent evidence shows that progression of hypertension-induced renal damage is associated with intrarenal leukocyte infiltration and inflammation (28). In addition, treatment with immunosuppressant/antiinflammatory drugs or chemokine receptor antagonists to inhibit leukocyte recruitment prevents the progression of renal injury in hypertensive animals (3, 29). Taken together, these observations support the notion that enhanced inflammatory responses induced by elevated plasma SP levels may contribute to pathogenesis of renal injury in DOCA-salt mice. Indeed, we found that two structurally distinct NK-1R antagonists markedly decrease the extent of macrophage infiltration into the kidney in DOCA-salt mice.

SP is known to induce increased extravasation of leukocytes and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation of leukocytes (30). It has been shown that rat peritoneal mast cells generate intracellular ROS upon stimulation with nanomolar concentrations of SP (31), and the effects of SP on leukocyte ROS production are dose dependent (32). Despite ROS's protective effects in the case of bactericidal infection, accumulating evidence suggests that ROS plays a role in the pathogenesis of tissue destruction. Single oxygen and hydroxyl radicals derived from superoxide anions that are produced by a membrane-localized enzyme reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase in macrophages and neutrophils are extremely reactive in breaking DNA strands, altering enzyme activities, and inhibiting lipid peroxidation (28). Indeed, progression of hypertension-induced renal damage has been linked to oxidative stress (28). We found that urinary 8-isoprostane, a stable and key marker of oxidative stress, was elevated in DOCA-salt mice, indicating enhanced ROS generation in these hypertensive mice. In addition, treatment with the NK-1R antagonists resulted in decreased urinary 8-isoprostane excretion, accompanying with attenuated renal injury in DOCA-salt mice. Although it is likely that NK-1R antagonists may reduce renal injury, in part, by inhibition of ROS production in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice, whether NK-1R antagonist-induced suppression of ROS may serve a causative role for renal protection observed in these mice remains to be further investigated in the future.

L-733,060 and RP-67580 belong to potent nonpeptide antagonists of SP both in vitro and in vivo. They act specifically and competitively on NK-1R (13, 33). The development of selective, nonpeptide NK-1R antagonists has enabled investigation of the role of tachykinin. In the present study, both NK-1R antagonists alleviate renal injury in terms of renal function and morphology in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Given that the structures of L-733,060 and RP-67580 are distinct, the effects of these drugs are likely related to specific rather than nonspecific action of NK-1R blockade. Using the doses of RP-67580 and L-733,060 reportedly sufficient to produce effective NK-1R blockade (13, 14), these drugs decreased renal injury by about 50% in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice in the present study. The remaining renal damage unaffected by these antagonists indicates that SP is not the sole factor mediating renal injury induced by DOCA-salt hypertension and that SP-independent mechanisms are operant, which is beyond the scope of the present study but deserves future investigation.

In summary, our data demonstrate a newly recognized role of the SP-NK-1R pathway in renal injury occurring in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. The findings that blockade of NK-1R attenuates renal injury induced by DOCA-salt hypertension suggest that SP may contribute to DOCA-salt hypertension-induced renal injury by activation of NK-1R in mice leading to enhanced oxidative stress and inflammation in the kidney.

Perspectives

This study suggests a role for SP in renal injury induced by DOCA-salt hypertension and indicates that blockade of NK-1R may provide protection against renal injury after DOCA-salt treatment in mice. Although these data contribute to our understanding of the pathophysiology of renal injury and raise the possibility of using NK-1R antagonists clinically in preventing renal injury during salt-sensitive hypertension, a cautionary note exists. The DOCA-salt-hypertensive model is not a form of hypertension simply caused by excessive salt intake, and it is well known that salt or mineralocorticoid may each induce blood pressure-independent damage (34–36). In addition, gradual increases in blood pressure occur over a long period of time in most of primary hypertensive patients. In contrary, a rapid and severe increase in blood pressure is seen in DOCA-salt-hypertensive mice. Thus, the model of DOCA-salt hypertension in animals, like any other experimental model, has its limitations. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the mouse model may serve as a valuable tool for providing insights so that future human studies may be justified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL-57853, HL-73287, and DK67620 (to D.H.W.). This work was also supported, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81170243 (to Y.W.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BW

- Body weight

- CGRP

- calcitonin gene-related peptide

- DOCA

- deoxycorticosterone

- HR

- heart rate

- MAP

- mean arterial pressure

- NK-1R

- neurokinin-1 receptor

- PAS

- periodic acid-Schiff

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SP

- substance P.

References

- 1. Rostand SG, Kirk KA, Rutsky EA, Pate BA. 1982. Racial differences in incidences of treatment for end stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 306:1276–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vernerová Z, Kujal P, Kramer HJ, Bäcker A, Cervenka L, Vanecková I. 2009. End-organ damage in hypertensive transgenic Ren-2 rats: influence of early and late endothelin receptor blockade. Physiol Res 58:S69–S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Y, Wang DH. 2009. Aggravated renal inflammatory responses in TRPV1 gene knockout mice subjected to DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol 297:F1550–F1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wimalawansa SJ. 1996. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and its receptors: molecular genetics, physiology, pathophysiolgy, and therapeutic potentials. Endocr Rev 17:533–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. 2003. Dietary sodium loading increases arterial pressure in afferent renal-denervated rats. Hypertension 42:968–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang DH, Li J, Qiu J. 1998. Salt sensitive hypertension induced by sensory denervation: introduction of a new model. Hypertension 32:649–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Y, Wang DH. 2006. A novel mechanism contributing to development of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension: role of the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1. Hypertension 47:609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Kaminski NE, Wang DH. 2005. VR1-mediated depressor effects during high-salt intake: role of anandamide. Hypertension 46:986–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakanishi S. 1991. Mammalian tachykinin receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci 14:123–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maggi CA. 1997. The effects of tachykinins on inflammatory and immune cells. Regul Pept 70:75–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Babánková D, Huang J, Swain GM, Wang DH. 2008. Deletion of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors exaggerates renal damage in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension 52:264–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bang R, Sass G, Kiemer AK, Vollmar AM, Neuhuber WL, Tiegs G. 2003. Neutokinin-1 receptor antagonists CP-96,345 and L-733,060 protect mice from cytokine-mediated liver injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 305:31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garret C, Carruette A, Fardin V, Moussaoui S, Peyronel JF, Blanchard JC, Laduron PM. 1991. Pharmacological properties of a potent and selective nonpeptide substance P antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:10208–10212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inoue H, Nagata N, Koshihara Y. 1995. Involvement of substance P as a mediator in capsaicin-induced mouse ear oedema. Inflamm Res 44:470–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Liew JB, Davis FB, Davis PJ, Noble B, Bernardis LL. 1992. Calorie restriction decreases microalbuminuria associated with aging in barrier-raised Fisher 344 rats. Am J Physiol 263:F554–F561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagase M, Shibata S, Yoshida S, Nagase T, Gotoda T, Fujita T. 2006. Podocyte injury underlies the glomerulopathy of Dahl salt-hypertensive rats and is reversed by aldosterone blocker. Hypertension 47:1084–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mundel P, Shankland SJ. 2002. Podocyte biology and response to injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:3005–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Helke CJ, Seagard JL. 2004. Substance P in the baroreceptor reflex: 25 years. Peptide 25:413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abdata AP, Haibara AS, Colombari E. 2003. Cardiovascular responses to substance P in the nucleus tractus solitarii: microinjection study in conscious rats. Am J Physiol 285:H891–H898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schoborg RV, Hoover DB, Tompkins JD, Hancock JC. 2000. Increased ganglionic responses to substance P in hypertensive rats due to upregulation of NK1 receptors. Am J Physiol 279:R1685–R1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wofford MR, Hall JE. 2004. Pathophysiology and treatment of obesity hypertension. Curr Pharm Des 10:3621–3637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison S, Geppetti P. 2001. Substance P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33:555–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pernow B. 1983. Substance P. Pharmacol Rev 35:85–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schratzberger P, Reinisch N, Prodinger WM, Kähler CM, Sitte BA, Bellmann R, Fischer-Colbrie R, Winkler H, Wiedermann CJ. 1997. Differential chemotactic activities of sensory neuropeptides for human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol 158:3895–3901 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marriott I, Mason MJ, Elhofy A, Bost KL. 2000. Substance P activates NF-κB independent of elevations in intracellular calcium in murine macrophages and dendritic cells. J Neuroimmunol 102:163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kincy-Cain T, Bost KL. 1996. Increased susceptibility of mice to Salmonella infection following in vivo treatment with the substance P antagonist, spantide II. J Immunol 157:255–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perianin A, Snyderman R, Malfroy B. 1989. Substance P primes human neutrophil activation: a mechanism for neurological regulation of inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 161:520–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Vaziri ND, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ. 2004. Oxidative stress, renal infiltration of immune cells, and salt-sensitive hypertension: all for one and one for all. Am J Physiol 286:F606–F616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Olearczyk JJ, Sridhar A, Cook AK, Inscho EW, Pollock DM, Imig JD. 2007. Chemokine receptor 2b inhibition provides renal protection in angiotensin II-salt hypertension. Hypertension 50:1069–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chien CT, Yu HJ, Lin TB, Lai MK, Hsu SM. 2003. Substance P via NK1 receptor facilitates hyperactive bladder afferent signaling via action of ROS. Am J Physiol 284:F840–F851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brooks AC, Whelan CJ. 1999. Reactive oxygen species generation by mast cells in response to substance P: a NK1-receptor-mediated event. Inflamm Res 48:S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen WC, Hayakawa S, Shimizu K, Chien CT, Lai MK. 2004. Catechins prevents substance P-induced hyperactive bladder in rats via the down-regulation of ICAM and ROS. Neurosci Lett 367:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seabrook GR, Shepheard SL, Williamson DJ, Tyrer P, Rigby M, Cascieri MA, Harrison T, Hargreaves RJ, Hill RG. 1996. L-733,060, a novel tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist: effects in [Ca2+]i mobilization, cardiovascular and dural extravasation assays. Eur J Pharmacol 317:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fiore MC, Jimenez PM, Cremonezzi D, Juncos LI, Garcia NH. 2011. Statins reverse renalinflammation and endothelial dysfunction induced by chronic high salt intake. Am J Physiol 301:F263–F270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Remuzzi G, Cattaneo D, Perico N. 2008. The aggravating mechanisms of aldosterone on kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:1459–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kawarazaki H, Ando K, Fujita M, Matsui H, Nagae A, Muraoka K, Kawarasaki C, Fujita T. 2011. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation:a major contributor to salt-induced renal injury and hypertension in young rats. Am J Physiol 300:F1402–F1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]