Abstract

We have previously confirmed a paradoxical mineralizing enthesopathy as a hallmark of X-linked hypophosphatemia. X-linked hypophosphatemia is the most common of the phosphate-wasting disorders mediated by elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and occurs as a consequence of inactivating mutations of the PHEX gene product. Despite childhood management of the disease, these complications of tendon and ligament insertion sites account for a great deal of the disease's morbidity into adulthood. It is unclear whether the enthesopathy occurs in other forms of renal phosphate-wasting disorders attributable to high FGF23 levels. Here we describe two patients with autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets due to the Met1Val mutation in dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 (DMP1). In addition to the biochemical and skeletal features of long-standing rickets with elevated FGF23 levels, these individuals exhibited severe, debilitating, generalized mineralized enthesopathy. These data suggest that enthesophytes are a feature common to FGF23-mediated phosphate-wasting disorders. To address this possibility, we examined a murine model of FGF23 overexpression using a transgene encoding the secreted form of human FGF23 (R176Q) cDNA (FGF23-TG mice). We report that FGF23-TG mice display a similar mineralizing enthesopathy of the Achilles and plantar facial insertions. In addition, we examined the impact of standard therapy for phosphate-wasting disorders on enthesophyte progression. We report that fibrochondrocyte hyperplasia persisted in Hyp mice treated with oral phosphate and calcitriol. In addition, treatment had the untoward effect of further exacerbating the mineralization of fibrochondrocytes that define the bone spur of the Achilles insertion. These studies support the need for newer interventions targeted at limiting the actions of FGF23 and minimizing both the toxicities and potential morbidities associated with standard therapy.

Some of the most high profile discoveries in bone and mineral metabolism of the past decade have involved identification of genes that are responsible for genetic syndromes of abnormal mineralization. A murine model of X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH), the Hyp mouse, has proved invaluable in illuminating the physiological role of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23 as an important regulator of phosphate homeostasis as well as the recognition of bone as an endocrine organ (1, 2). FGF23 was so identified as a phosphotonin that acts via the FGF receptor (FGFR)-1/α-klotho complex at proximal tubular epithelial cells to regulate phosphate reabsorption and the synthesis of biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (3–8). The transmembrane protein, klotho, increases the affinity of FGFRs for FGF23, in particular FGFR1c, FGFR3c, and FGFR4 (9). A number of phosphate-wasting disorders in addition to XLH have been attributed to high circulating levels of FGF23 including tumor-induced osteomalacia, autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets, and autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR) 1 and 2 (10–15).

XLH is the most common of the phosphate-wasting disorders mediated by FGF23 (16). FGF23 is inappropriately high in patients with XLH and significantly elevated in Hyp mice as a consequence of inactivating mutations of the phosphate regulating endopeptidase homolog, X-linked (PHEX) gene product (17, 18). PHEX encodes an endopeptidase that, when inactivated, results in elevated circulating levels of FGF23 (2). Less reported than defective bone growth and mass, a generalized and severe mineralization of tendon and ligament insertion sites (enthesophytes) and osteoarthropathy characterized by osteophytes are also hallmarks of XLH. Indeed, despite childhood management of the disease, these complications of cartilaginous tissues become a dominant feature in the clinical evolution of XLH and account for a great deal of the disease's morbidity into adulthood (19–21). In addition, both occur at a much higher frequency and earlier than occurs in the typical aging population (20–27). Our recent report including a survey of 39 patients (32.7 ± 19.5 yr) with XLH revealed that a majority had evidence of enthesopathy with multiple insertion site involvement (28). The Achilles insertions into the calcaneal tuberosity, including the plantar ligament, and the quadriceps femoris tendon insertion into the patella and the distal patellar tendon were involved in 74 and 56% of patients, respectively. The pelvis and spine (with spinal stenosis) are also frequently involved and together contribute to the debilitating aspects of this disease (20, 29). These numbers are consistent with two additional retrospective analyses that report enthesophytes in 69% of patients up to 30 yr of age, with 100% of patients above 30 yr showing evidence of enthesis involvement (21, 25).

The etiology of enthesophyte formation in XLH remains unresolved but has been suggested to be an intrinsic part of the disease (19, 21, 24, 28). A confounding and paradoxical feature of the mineralizing enthesopathy of XLH is the prevalence and relatively early onset in a disease characterized by rickets, hypophosphatemia, and unmineralized osteoid. Even with standard treatment of oral phosphate and calcitriol, which improves the clinical course of the disease and biomechanical properties of the bone into which the entheses insert, enthesopathy develops (19, 30, 31). Accordingly, there is no evident correlation between the enthesopathy of patients, regardless of treatment history (21, 32). Our finding in a murine model of XLH, the Hyp mouse, that a mineralized enthesopathy develops at sites most frequently involved in patients with XLH is also consistent with the finding that enthesopathy develops in the absence of treatment and is therefore not a consequence of treatment (28).

It is unknown the degree to which FGF23 and PHEX contribute to the progression of the mineralizing enthesopathy of XLH. The substrate of the mutated PHEX gene product has not yet been identified but does not appear to involve the proteolytic processing of FGF23 (2). It is also unknown whether PHEX (or a PHEX substrate) locally regulates chondrocyte mineralization (33, 34) or fibrocartilage. We previously proposed that the paradoxical mineralization of the entheses within the biochemical milieu of XLH might be due to the direct actions of FGF23 on fibrochondrocytes (28). The mineralizing enthesopathy of Hyp mice is characterized by significant hyperplasia of resident mineralizing fibrochondrocytes that coexpress FGFR3 and klotho. This is in sharp contrast to what is generally thought to be the usual progression of enthesophytes as a heterotopic endochondral bone-forming process (35, 36). To this end, we present here clinical and radiographical evidence that the enthesopathy may also be a feature of another FGF23-mediated phosphate-wasting disease, ARHR. The phosphate-wasting of XLH AND ARHR1, although the consequence of two distinct mutations [PHEX and dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 (DMP1), respectively], arises as a result of elevated FGF23 (12, 37, 38). These data suggest that FGF23 may be a common etiological factor in the progression of the enthesopathy in phosphate-wasting disorders.

Because it remains to be defined which factor(s) contribute to the calcification of tendon and ligament insertion sites in XLH, we have now expanded our earlier observations to include studies conducted on a murine model of FGF23 overexpression using a transgene encoding the secreted form of human FGF23 (R176Q) cDNA (FGF23-TG mice) (39). These mice have a biochemical profile akin to the phosphate-wasting disorders attributed to FGF23 including decreased renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate, increased serum alkaline phosphatase activity, and low serum levels of 1,25 vitamin D3 despite hypophosphatemia. In addition, FGF23-TG mice display all the phenotypic traits of phosphate-wasting disorders described in Hyp mice (1) [and DMP-1 null mice, the murine model of ARHR (10)] including hypophosphatemia rickets and metaphyseal splaying, diminished cortical and trabecular bone volume, and expanded unmineralized osteoid. Finally, it is currently unknown what impact standard therapy has on the progression of the enthesopathy of phosphate-wasting disorders. We therefore examined the cellular effect of treatment on enthesophyte formation in Hyp mice and discuss the implications of our findings in considering strategies in the management of the adult morbidities of this disease.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated. Type II collagen antibody was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Animals and tissue processing

Female Hyp mice of the C57BL/6 strain (and littermate C57BL/6 controls) were obtained in-house at the Yale University School of Medicine animal care facility using animals obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals were maintained on normal rat chow and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Bone samples were obtained from FGF23-TG mice bred in the C57BL6 background in accordance with the McGill University animal care committee guidelines. Serum calcium and phosphate levels were confirmed in control and Hyp mice and at the time the animals were killed by orbital bleed and analyzed at the Yale Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center. Serum was collected in Hyp mice before treatment and at the time the animals were killed. Treated Hyp mice were maintained on high-phosphate drinking water (1.93 g elemental phosphate/liter starting at weaning, ad libitum) and injected sc with calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D3; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI] from wk 3 to 12 (0.175 μg/kg·d) every other day.

At the time the animals were killed, legs were rapidly dissected for the Achilles tendon insertion of the triceps surae into the calcaneus and fixed in 4%-buffered paraformaldehyde for 1–2 h on ice for immunohistochemistry and alkaline phosphatase activity. Selected bones were decalcified in daily changes of 7% EDTA/PBS solution at pH 7.1 for 21 d at 4 C and washed with PBS/50 mm MgCl2 overnight. Tissues were paraffin embedded and sectioned to a thickness of 8 μm, with the section thickness used as an indicator of relative tissue depth for comparison between Hyp and control. The contralateral leg was embedded in plastic and used for von Kossa and safranin O staining; the leg was fixed in ethanol, embedded in plastic, and sectioned at 4 μm. Each condition was repeated in 10 littermate mice and six littermate mice for phosphate/vitamin D studies.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized tissue sections were processed as previously described with immunostaining visualized using the ABC staining system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) followed by incubation with a peroxidase substrate (diaminobenzidine) for 3–5 min (28).

Alkaline phosphatase activity and analysis

Alkaline phosphatase activity was performed on serial sections of deparaffinized sections and cell density analyzed as previously described (28, 40). Briefly, alkaline phosphatase-stained cells of insertions sites were quantified by analysis of the total calcaneal insertion including the calcaneal and plantar fascial insertions. Images were converted to gray scale in Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). From histograms of eight-bit, gray-scale images, a luminance value of 40 was defined as the upper threshold that defined positive staining of cells. The total sum of data points within this range of the histogram was calculated, and data are reported as the density of alkaline phosphatase-stained fibrochondrocytes and expressed as a percentage of alkaline phosphatase-positive fibrochondrocytes to total enthesis area.

Von Kossa and safranin O staining

For safranin O, deparaffinized sections were stained with Weigert's iron hematoxylin working solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) followed by fast green solution (Acros Organics, Morris Plains, NJ), and then stained in 0.1% safranin O solution (Polysciences, Warrington, PA), as previously described (40). Mineral staining was conducted by the Yale Core Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders using a von Kossa staining procedure with toluidine blue counterstaining.

Lacunar area measurements

Measurements of lacunar area were performed on ×40 images of the Achilles insertion and plantar ligament that had been stained for mineral using the von Kossa method as these images retain a high contrast between mineral and unmineralized tissue. Lacunae were measured using ImageJ in which a threshold was applied to images to fit and outline the lacunae of attachment zone fibrochondrocytes. After thresholding, a scale was set (in micrometers) and lacunae area was assessed using the Analyze Particle command to count and measure objects in the total area sampled. Analyzed images were manually examined and outlined objects that did not correspond to fibrochondrocytes were omitted from the final data set. Four to five sections per animal were assessed and the calculated area of the lacunae were averaged and compared with like-treated animals. Data were reported as the average area of lacunae (square micrometers).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± se. Statistical significance (P < 0.01) was determined using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad software; GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

Clinical presentation

The proband (Fig. 1A; subject II3), a 36-yr-old man of Lebanese origin, presented at the clinic for evaluation of abnormal skeletal development and worsening chronic back pain. The patient was diagnosed with rickets early in childhood and underwent surgical correction of what he reported as bowed legs. He was also treated periodically with active forms of vitamin D and occasionally oral phosphate. For the last 8 yr, he had been complaining of worsening low back pain and stiffness, which was now becoming referable also to the dorsal and cervical spine. Otherwise, he was healthy with no intercurrent illnesses or hospital admissions. He was born to healthy parents who were first cousins. He had one older and one younger brother (subjects II2 and II5) who were both short with bowed legs. The youngest brother was the most severely affected (subject II5, see below). His sister and eldest brother had attained normal height.

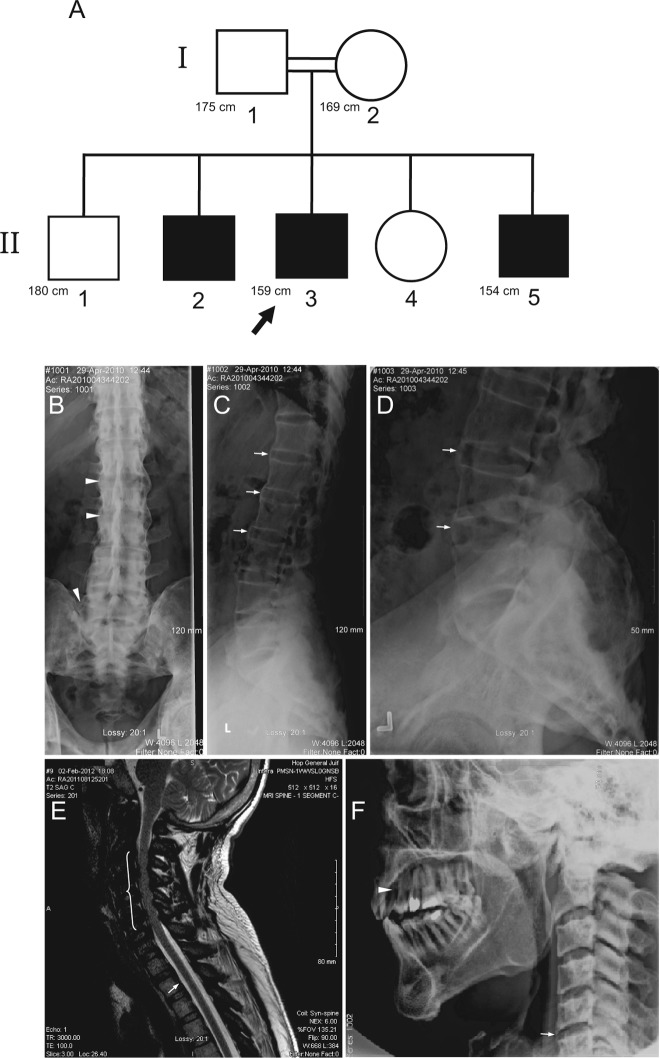

Fig. 1.

A, Pedigree of the family with ARHR. White symbols, Unaffected members; black symbols, affected members; double line, consanguinous marriage. Arrow indicates proband. Known height measurements are indicated in centimeters. B–D, Radiographs of thoracic and lumbosacral spine of the proband showing calcification and/or ossification of the interspinous and iliolumbar ligaments (arrowheads), sacroiliac joint sclerosis, and multiple enthesophytes (arrows). E, Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine of the proband illustrating advanced sclerosis at the spinous processes with marked hypointensity on T2 of the interspinous ligaments, suggesting the presence of calcification and/or ossification. Due to the increased sclerosis of the cervical spine, the central canal from C2 to C6 is moderately narrowed (bracketed region). Furthermore, there is ossification along the posterior longitudinal ligaments (arrow). F, Subject II5 radiographs of the cervical spine showing enthesophyte formation (arrow). Arrowhead indicates the site of tooth removal to allow for insertion of straw for feeding.

At presentation, the proband was of short stature (159 cm) and had severe knee varus deformities despite having undergone in the past multiple surgical procedures for restoration of the mechanical axis of the limbs. The head circumference was increased (60.3 cm) with a broad forehead. He had crowding of the upper incisors and canines with extensive dental caries. There were bilateral longitudinal surgical scars in the medial aspect of the proximal tibiae. Subject II5, a 26-yr-old man at the time of presentation, had an early clinical course very similar to his brother (the proband). He was also treated sporadically with vitamin D and oral phosphate and lower limb osteotomies were performed early in the second decade of life to correct the lower extremity deformities. His height was 154 cm and had knee varus deformities. His major complaint at the time centered on his inability to eat due to severe fibrosis affecting the temporomandibular joints. The interincisal opening distance was only 3 mm. The occlusion was so severe so as to necessitate the removal of a tooth to ensure adequate administration of liquid nourishment via a straw. Subsequently, bilateral temporomandibular joint implants were surgically inserted and have provided normal jaw function.

Biochemical parameters

Biochemical parameters for both subjects II3 and II5 devoid of any treatment are shown in Table 1. They had hypophosphatemia and normocalcemia, with elevated alkaline phosphatase activity, osteocalcin, PTH, and FGF23 levels. Tubular maximum phosphate reaborption/glomerular filtration rate, indicating the serum phosphate concentration at which phosphate appears in the urine, was markedly diminished with low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and inappropriately low/normal 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 for the degree of hypophosphatemia. The clinical and biochemical parameters in the two brothers were therefore compatible with FGF23-related hypophosphatemic rickets and osteomalacia.

Table 1.

Physical, biochemical, and bone densitometry parameters in subjects with ARHR

| Subject II3 | Subject II5 | Normal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | M | |

| Age (yr) | 36 | 26 | |

| Height (cm) | 159 | 154 | |

| Creatinine (μmol/liter) | 57 | 63 | 65–120 |

| Calcium (mmol/liter) | 2.39 | 2.51 | 2.12–2.62 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/liter) | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.70–1.45 |

| PTH (ng/liter) | 126 | 62 | 10–70 |

| ALP (U/liter) | 263 | 134 | 40–125 |

| Osteocalcin (μg/liter) | 95 | 57 | 5–55 |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/liter) | 31 | 35 | 75–250 |

| 1,25(OH)2D (pmol/liter) | ND | 129 | 38–134 |

| FGF23 (pg/ml) | 110 | 87 | <71 |

| TmP/GFR (mmol/liter) | 0.59 | 0.35 | >0.80 |

| L2-L4 BMD T-score | +5.8 | ND | |

| Femoral neck T-score | +2.8 | ND |

M, Male; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3; ND, not determined; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; BMD, bone mineral density; TmP, tubular maximum phosphate reabsorption.

Genetic analyses

Sequence analyses of PHEX and FGF23 from the proband's genomic DNA by a commercial genetics laboratory before presentation did not reveal any abnormalities. In contrast, similar analysis of DMP1 identified a missense mutation in exon 2 that changed the initiator codon ATG to GTG (1A G, leading to M1V), a loss-of-function mutation (12), confirming the diagnosis of autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets 1.

Radiographic assessment

Radiographs of the proband's axial skeleton demonstrated marked sclerosis along the facets as well as enthesophytes and severe ligamental calcifications, involving mainly the interspinous ligaments, likely resulting in pain and movement restriction of the spine (Fig. 1, B–D). There was bony ankylosis of the sacroiliac joints. Paraspinal and ileofemoral ligaments calcification overestimated the bone mineral density measurements at the lumbar spine and femoral neck, respectively (Table 1). On the cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging, there is again evidence of calcification of the interspinous ligament as well as the posterior longitudinal ligament throughout the cervical spine causing multilevel central canal stenosis (Fig. 1E). Enthesophytes were also noted at the vertebral bodies of subject II5 (Fig. 1F).

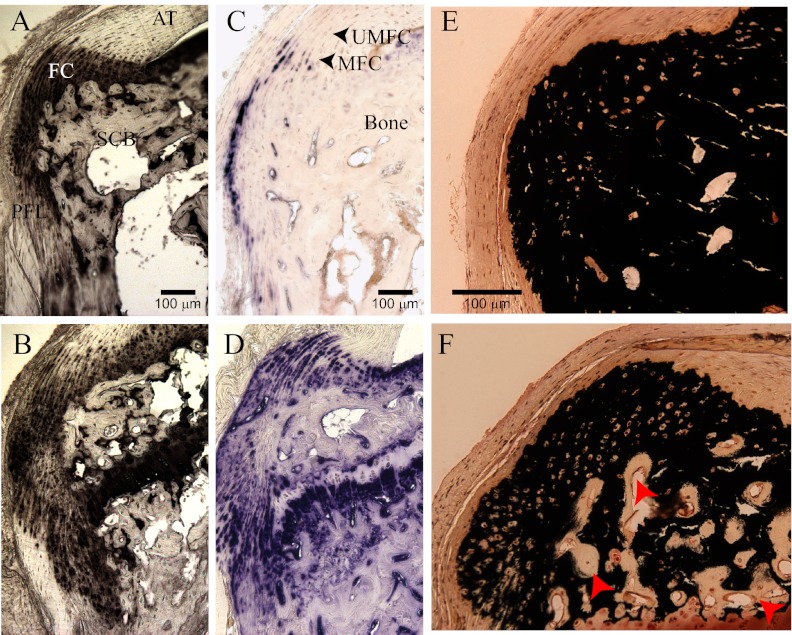

These data suggest that mineralizing enthesopathy is a feature common to phosphate-wasting disorders mediated by FGF23. To address this possibility, we examined the Achilles insertion of a murine model of FGF23 overexpression using a transgene encoding the secreted form of human FGF23 (R176Q) cDNA (FGF23-TG mice). Three primary histological markers of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes were made: 1) pericellular type II collagen, the primary secreted matrix protein of chondrocytes (41); 2) in situ alkaline phosphatase enzyme activity as an indicator of cells actively involved in the mineralization of the fibrocartilage matrix (42); and 3) in situ von Kossa stain for calcium phosphate mineral. We have previously reported that the primary histological feature of the enthesopathy of the insertions of 6- to 8-month-old Hyp mice was a dramatic cellular expansion and thickening of mineralizing enthesis fibrocartilage. We also found evidence of cellular expansion in several fibrocartilaginous sites in Hyp mice in early as 10 wk of age. We have previously demonstrated that the Achilles insertion in mice develops entirely postnatally, maturing at 12 wk (28). We therefore examined the Achilles insertions of 12-wk-old in FGF23-TG mice and compared these findings with littermate control mice and to Hyp mice.

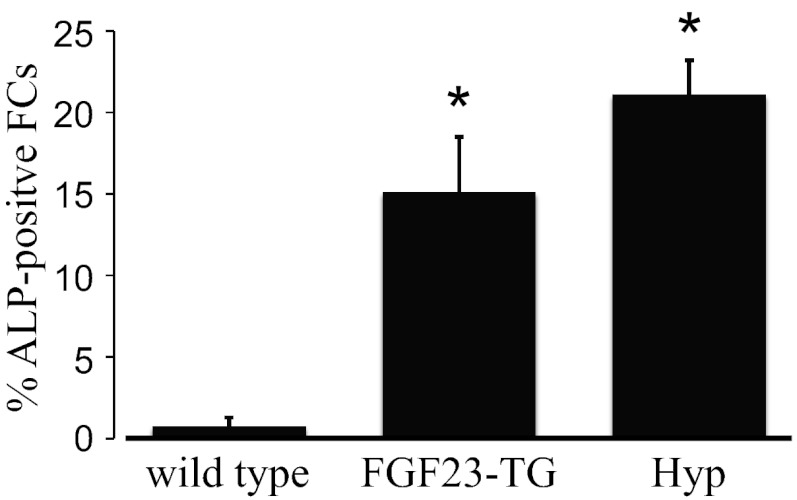

Fibrochondrocytes are terminally differentiated cells that are thought to initially arise from residual cells of the cartilaginous anlagen of the calcaneus (28, 43) but during development arise by metaplasia of tendon cells at the insertion site (44). At these sites, their phenotype can be tracked by the conversion of predominantly type I collagen-secreting cells to cells that synthesize and secrete primarily type II collagen. Accordingly, the number of type II collagen-expressing cells was elevated in FGF23-TG mice at the calcaneal insertions compared with control littermate mice (Fig. 2A vs. B). The zone of mineralized fibrocartilage of the enthesis is normally confined to a small number of cells at the Achilles insertions at maturity (36). As such, the percentage of alkaline phosphatase-positive chondrocytes relative to the total area of the Achilles and plantar facial insertion area was found to be 0.75 ± 0.52% (n = 10) in wild-type mice (Figs. 2C and 3). In contrast to these findings, the percentage of type II collagen cells exhibiting alkaline phosphatase activity in the Achilles insertions of 12-wk-old FGF23-TG mice was significantly elevated above control mice (15.1 ± 3.4%, P < 0.01, n = 10, Figs. 2D and 3). These results were comparable with the percentage of alkaline phosphatase-positive cells at the Achilles insertions of 12-wk-old Hyp mice (Fig. 3) compared with control mice (21.1 ± 2.1%, n = 6 P < 0.01), representing a greater than 20-fold increase in cells positive for alkaline phosphatase.

Fig. 2.

Cellular expansion of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes in 12-wk-old FGF23-TG mice of Achilles tendon (AT) insertion into the calcaneal tuberosity and of the distal plantar fascia ligament (PFL). A, Control wild-type littermate mice. Immunohistochemical staining of type II collagen of the calcaneal entheses is confined to the fibrochondrocytes of the AT and PFL, and bone is negative. B, FGF23-TG mice: expansion of type II collagen-positive fibrochondrocytes into the posterior and medial process of the calcaneus and at the PFL attachment. C, Control mice. Cellular alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity of the enthesis is confined to a narrow zone of mineralized fibrochondrocytes (MFC) and absent in unmineralized fibrocartilage (UMFC). D, FGF23-TG mice. Expansion of cellular AP activity colocalizes with fibrochondrocytes shown in B. E, Control mice. von Kossa staining of calcium phosphate mineral predominantly corresponds with bone mineral shown in C. F, FGF23-TG mice: von Kossa staining of bone mineral and fibrocartilage mineral shown in D. Red arrows show significant unmineralized osteoid of bone typical of FGF23-mediated phosphate-wasting disorders.

Fig. 3.

Average results of total experiments comparing the percentage of alkaline phosphatase-positive cells of 12-wk-old wild-type control (C57BL/6), FGF23-TG, and Hyp mice, respectively. Data are mean ± sem, and results are significant at the P < 0.01 level.

These data additionally suggest that the expansion of fibrochondrocytes arise during the developmental period of the entheses. At birth, the Achilles tendon is attached to a cartilaginous model of the calcaneus, which is surrounded by a perichondrium. The first evidence of fibrochondrocytes occurs at 2 wk [which are initially derived from the cartilage rudiment of the calcaneus (43)], and the insertion is developmentally mature by 12 wk in mice (28). This indeed appears to be the case, as shown in a survey of the Achilles insertion from 2 to 10 wk (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org) showing the disproportionate increase in total fibrocartilage in Hyp mice as a function of age, in contrast to littermate wild-type mice in which the insertion becomes more refined.

We have previously described the up-regulation of tissue alkaline phosphatase activity in both bone and articular cartilage in Hyp mice. However, in both tissues, mineralization of the matrix is defective (40). We therefore measured mineralization of the entheses using the von Kossa method for phosphate mineral. Staining revealed that cells positive for alkaline phosphatase activity were able to mineralize the extracellular matrix despite a rachitic environment. Mineralization invaded both the Achilles insertion and the plantar fascia ligament (Fig. 2, E and F). From these data we determined that the increase in mineralization was attributable to an expansion of fibrochondrocytes of the mineralizing type and that calcification of the matrix was intact.

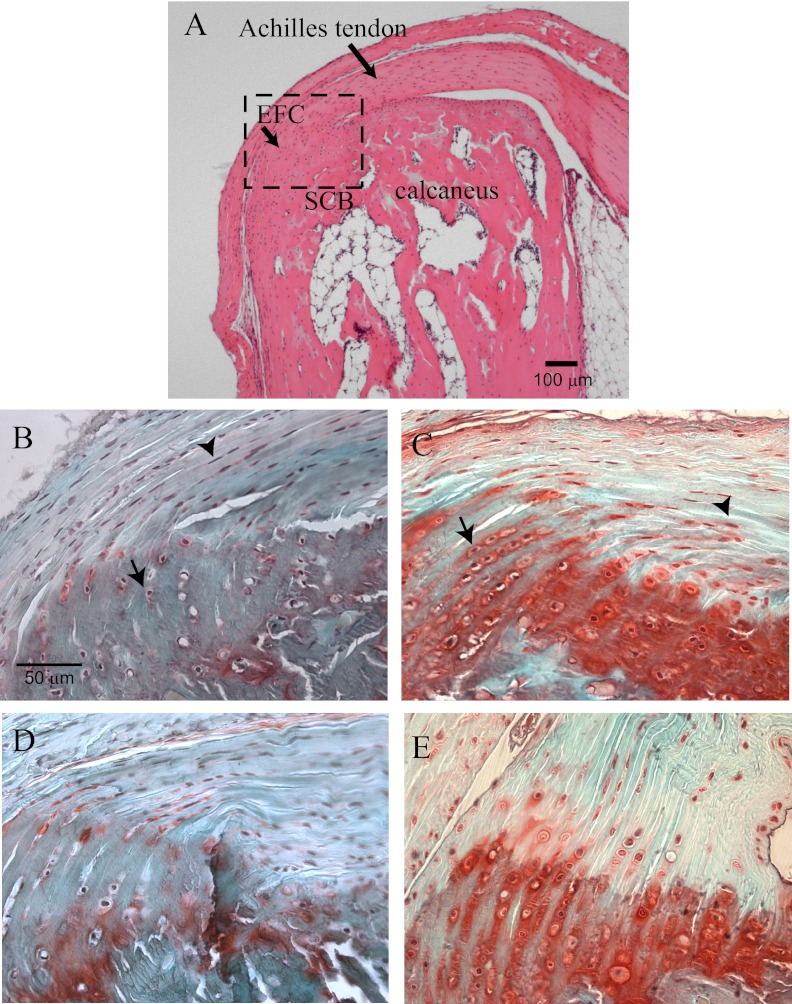

Less than 1% of the extracellular matrix of tendons are proteoglycans and are predominantly smaller molecular weight proteoglycans such as decorin, critical for normal collagen structure and function that underlie the tensile properties of tendon (45, 46). The profile of proteoglycans in the fibrocartilages of wrap-around tendons such as the Achilles organ have been reported (35, 47, 48). Levels of large sulfated proteoglycans like aggrecan dominate and contribute to the material stiffness needed to accommodate compressive forces (43, 49–51). We therefore next examined the expression pattern and the relative levels of sulfated proteoglycans by safranin O staining between control and FGF-TG or Hyp mice. Compared with control mice (Fig. 4, A and C), both Hyp and FGF-TG mice (Fig. 4, B and D) had an expansion of proteoglycan-secreting fibrochondrocytes within the tendinous region. In addition, there was a significant up-regulation of the level of sulfated proteoglycan staining in attachment zone fibrochondrocytes in both Hyp and FGF-TG mice (Fig. 4, B and D).

Fig. 4.

Up-regulation of proteoglycans within the tendinous and fibrocartilaginous zones of the Achilles insertion. A, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of Achilles insertion depicting the region of interest shown in panels B–E at a higher magnification. A, Diagram showing region of interest shown for panels B–E in H&E-stained Achilles insertion including enthesis fibrocartilage (EFC) into the subchondral bone (SCB). B, Safranin O staining of proteoglycans of littermate wild-type mice, Arrowhead, Tendon cells; arrows, fibrochondrocytes. C, Proteoglycan staining of Hyp mice. Arrowhead, Tendon cells; arrows, fibrochondrocytes. D and E, Safranin O staining of proteoglycans of the littermate wild-type and FGF23-TG mice also show an increased proteoglycan expression within the entheses.

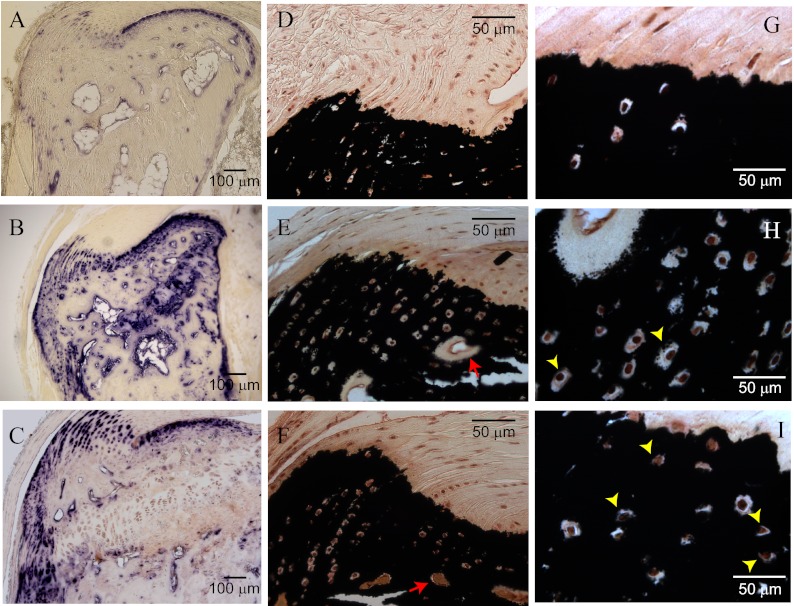

The prevalence and severity of enthesopathy of XLH correlates with age and patients with XLH develop enthesopathy, regardless of treatment status (22, 25, 28). Data presented here suggest that the cellular changes that accompany the expanded calcification of the entheses occur early in the course of the disease and correlates with the period of long bone growth. The primary therapy for XLH targets the period of long bone growth during adolescence to minimize the degree of short stature and to minimize the progression of varus or valgus secondary to rickets and osteomalacia. However, the cellular impact of treatment is unknown. Nor is it known whether the course of treatment contributes to the progression of enthesopathy or, alternatively, minimizes its progression secondary to improving bone mass. Therefore, we treated Hyp mice with the standard therapy for phosphate-wasting disorders at weaning, oral phosphate (1.93 g elemental phosphate per liter water starting at weaning) and calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D3)] from wk 3 to 12 (0.175 μg/kg·d) to facilitate intestinal reabsorption of phosphate and minimize secondary hyperparathyroidism encountered with sole phosphate supplementation (30, 52). Untreated Hyp mice had serum phosphate and calcium levels of 3.9 ± 0.4 and 8.0 ± 1.0 mg/dl, respectively; treated Hyp mice had serum phosphate and calcium levels of 7.9 ± 1.2 and 8.8 ± 0.6 mg/dl, respectively. We found that treatment did not significantly alter hyperplasia of mineralizing fibrocartilage cells in the Achilles insertion at 12 wk (Fig. 5). Shown are representative images obtained from treated (vs. vehicle treated) Hyp mice showing a thickening of alkaline phosphatase positive cells encased in mineral (Fig. 5, A–C). However, and as might be expected with normalization of serum phosphate levels, treatment exacerbated mineralization of the matrix surrounding the lacunae of fibrocartilage cells compared with untreated Hyp Mice (untreated Hyp, 59.1 ± 21.2 μm2; treated Hyp, 32.4 ± 12.4 μm2; Table 2; Fig. 5, D and G, vs. Fig. 5, E and H; and Fig. 5, F and I).

Fig. 5.

Treatment of Hyp mice with standard therapy of phosphate and calcitriol exacerbates mineralization of expanded fibrocartilaginous matrix. A and B, Comparison of alkaline phosphatase activity between control wild-type and Hyp mice show typical mineralizing fibrocartilage hyperplasia. C, Treatment of Hyp mice did not correct hyperplasia; note the same scale with improved calcaneal bone mass. D, von Kossa staining of calcium phosphate mineral predominantly corresponds with mineralizing fibrochondrocytes and bone mineral shown in panel A. E and F, Hyp mice and treated Hyp mice: von Kossa staining of bone mineral and fibrocartilage. Note the improved mineralization of osteoid between untreated and treated Hyp mice, respectively (red arrows). G–I, Higher magnification comparing size of fibrochondrocyte lacunae between control, Hyp, and Hyp-treated mice, respectively; see also Table 2.

Table 2.

Fibrochondrocyte lacunar area and serum chemistry with treatment

| Average lacunar area (μm2) | Serum P (mg/dl) | Serum Ca (mg/dl) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 15.3 ± 11.1 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 10 |

| Hyp | 59.1 ± 21.2a | 3.9 ± 0.4a | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 10 |

| Hyp tx | 32.4 ± 12.4a, b | 7.0 ± 0.5a | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 6 |

P, Phosphate; Ca, calcium; tx, treatment.

P < 0.01 control vs. Hyp.

P < 0.01 Hyp vs. Hyp tx.

Discussion

The period during long bone growth, before growth plate closure, is a major focus of treatment in patients with phosphate-wasting disorders. However, patients suffer lifelong skeletal abnormalities including persistent osteomalacia, osteoporosis and fracture risk, and dental abscesses and are prone to osteophytes secondary to articular cartilage degeneration despite standard treatment with oral phosphate and calcitriol (19). An increasing number of reports have also brought to light the prevalence of mineralizing enthesophytes as a confounding component in the spectrum of XLH morbidities. Like the general aging population, mineralizing enthesophytes are also restricted to fibrocartilaginous insertion sites, with few reports associated with fibrous insertion sites. Even then, the ectopic appearance of fibrocartilage has been reported (52). However, and in contrast to the aging population, the enthesopathy of XLH affects multiple insertion sites and occurs much earlier in life (20–27).

Fibrocartilaginous entheses are most common at attachment sites of the epiphysis of long bones and at the wrist and ankle short bones. At maturity, fibrocartilaginous entheses have four distinct zones of tissue that includes the tendon (and less commonly the ligament) and two narrow zones of fibrocartilage, an unmineralized and a mineralized zone, which intercalates into the zone of subchondral bone. They comprise a group of entheses that must withstand mechanical forces and often change in direction. The Achilles insertion into the calcaneal tuberosity is prototypical in that it is both heavily loaded and is subject to compressive forces as the foot flexes as well as being subject to changes in direction as the foot moves. In addition to the enthesopathy associated with sites of the appendicular skeleton, ectopic ossification of the axial skeleton can be particularly debilitating. Both vertebral osteophytes and calcification of the longitudinal and intervetebral spinal ligaments are painful, limit mobility and contribute to spinal stenosis (29, 53–56) and have also been reported in untreated patients (57, 58).

Data presented here, as well as two other recent reports of families with ARHR1 and ARHR2 displaying severe mineralizing enthesopathy and calcifications of the spinal ligaments (15, 32), suggest the enthesopathy is not unique to XLH and may be a common feature of phosphate-wasting disorders mediated by FGF23. Indeed, there have been no reports of mineralizing enthesopathy in other forms of rickets, such as the nonnutritional vitamin D-dependent form of rickets, suggesting a mechanism that involves factors other than aberrant mechanics or mineralization. Patients with ARHR1 and ARHR2 share a number of phenotypic features including short stature and severe enthesopathy with calcification of the spinal ligaments in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. The ankylosis of the spine resembles that seen in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, but in both forms of ARHR, it involves the posterior rather than the anterior longitudinal ligament. On the other hand, in contrast to patients homozygous for the IVS5–1G>A mutation in DMP1, our family with the M1V mutation did not exhibit the extensive deformity of the long bones. Nevertheless, it would appear that the enthesopathy in ARHR patients is overall significantly more severe than that observed in XLH patients.

We have previously shown that the enthesophytes or bone spurs that form at the patellar and Achilles insertion sites in Hyp mice are not the product of vascularization and osteogenic bone formation, as generally assumed. Instead the enthesopathy is characterized by a significant expansion of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes, which, like articular chondrocytes, are terminally differentiated cells (28). In this report, it is also apparent that cellular changes to the Achilles insertion in both FGF23-TG and Hyp mice occur early and coincidently with the development of the insertion site. The fibrocartilaginous enthesis is a specialized tissue that has evolved as a transitional tissue to meet the challenge of transferring mechanical loads, while dissipating stress, between tissues of very different chemical and structural composition. Normal insertion sites are characterized by a contiguous arrangement of fibrillar collagen fibers between all zones of tendon tissue and the irregular interdigitation of mineralized fibrochondrocytes into subchondral bone, allowing secure anchorage of tendon to bone (36, 47). In addition, the wrap-around geometry of Achilles tendons causes the insertion to experience compressive forces regularly, necessitating expression of large, sulfated proteoglycans-like aggrecan to cushion the contact during muscle contraction (46, 48, 59). The significant increase in sulfated proteoglycans in FGF23-TG and Hyp mice compared with wild-type littermates suggests that, in the hypophosphatemic environment, the entheses are subjected to abnormally high compressive forces.

Furthermore, as observed here, FGF-TG and Hyp mice exhibit an expansion of mineralized fibrochondrocytes at the insertion site, effectively increasing the tendon-to-bone contact area. This may represent an important compensation mechanism used by the body in response to the predicted decrease of elastic modulus in the soft bone of animals with osteomalacia. That is, assuming that force and strain parameters are unchanged, the body may be attempting to spread the load transferred through the tendon over a larger area of bone, lest the same force, applied to an area as small as the wild-type insertion, cause the insertion to pull free from bone tissue with a lowered elastic modulus, as in affected animals. Naturally, this compensation would not be predicted to approach the flexibility, stability, or resiliency of the insertion of a wild-type animal (even with treatment); however, it would offer a significant improvement in terms of reducing the likelihood of total mechanical failure of the insertion. Nonetheless, the expansion of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes would not be expected to completely compensate for the deficient biomechanical properties of bone. Mineralized fibrocartilage lacks the rigidity of bone, and, with significantly less capacity for repair (36), it would be expected that the underlying bone would become more susceptible to microfracture even with treatment. Studies in models of phosphate-wasting disorders are currently underway to measure the biomechanical properties of both tensile and compressive forces of the entheses and will further illuminate our understanding of these potentially adaptive cellular changes.

Although we find that standard therapy for XLH does not significantly impact the hyperplasia of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes, we cannot eliminate the contribution that abnormal mechanical forces play on the tendon-bone interface that results from unmineralized osteoid. Treatment has been reported to considerably improve bone mass in patients and in Hyp mice; osteomalacia persists in patients who have undergone treatment and despite reports to the contrary, we (and others) find that although the expanded rachitic growth plate is very sensitive to phosphate, the bone phenotype improves but still persists (30, 31, 40). This is not surprising because the standard therapy of phosphate and 1,25(OH)2D3 is not optimal, given that both agents directly potentiate FGF23 production in what becomes a vicious cycle, resulting in the inability to completely correct the hypophosphatemia and contributing to persistent osteomalacia (19, 60, 61). Furthermore, we have previously shown that both tenocytes and fibrochondrocytes express FGFR3 and klotho, making them a unique cellular target of FGF23 signaling (28).

Surprisingly little is known about the factors and molecular pathways that regulate the differentiation of fibrochondrocytes, perhaps owing to limited access to a relatively small number of cells that are highly invested into the bone interface. These specialized matrix-secreting chondrocytes arise by transdifferentiation of tenocytes, the fibroblast-like cells of the tendon (44, 62, 63). The appearance of fibrochondrocytes has been shown to be unaltered in response to muscle unloading but does significantly impact the maturation of the enthesis, suggesting that the transdifferentiation of cells does not take place in response to mechanical input (63). It is thus tempting to speculate that a combination of factors, including excess FGF23 and mechanical forces, may both contribute to the enthesopathy of FGF23-dependent phosphate-wasting disorders.

Based on our findings, we conclude that newer interventions targeted at limiting the phosphaturic actions of FGF23 may be required to effectively maintain long-term serum phosphate concentrations and minimize both the toxicities and potential morbidities associated with standard therapies (64). Indeed, an additional and very important finding of these studies is the fact that the fibrochondrocyte lacunae show improved mineralization in the treated Hyp mice, i.e. getting closer to control values. At first glance, this indicates that this is indeed a desired response rather than a negative consequence. The improvement in the mineralization of the lacunae (and of the bone osteoid) should be viewed as an indication that the treatment is working, yet the hyperplasia of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes is unaffected. This is in sharp contrast to normal entheseal phenotype of wild-type animals in which the zone of mineralizing fibrochondrocytes constitutes a very small portion of the insertion. Therefore, treatment does not alter the underlying pathophysiology of the enthesopathy. In fact, the additional mineral deposition at these sites extending into the tendinous region as a bona fide bone spur could potentially aggravate the clinical outcome. Furthermore, calcitriol, which is often difficult to titrate in patients and, as a result, may be associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism and nephrocalcinosis may also further exacerbate the mineralization of the entheses. These findings support the need for better and more targeted therapeutics in the treatment of XLH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients for their time and effort, allowing for additional characterization of the clinical features of ARHR1 described here. We thank Marc Tischkowitz (Department of Medical Genetics, McGill University) for assisting with the collection of the clinical data and arranging for the genetic analysis. We also thank Dr. Peter Amos (Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University) for helpful discussion regarding enthesis biomechanics and Shyam Desai for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Kidney Foundation of Canada (Grants R01 DK-49230; P30 AR46032; CORT P50 AR054086; R01 DK62515; and CTSA UL1 RR024139).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ARHR

- Autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets

- DMP1

- dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR

- FGF receptor

- FGF23-TG

- FGF23 overexpression using a transgene encoding the secreted form of human FGF23 cDNA

- PHEX

- phosphate regulating endopeptidase homolog, X-linked

- XLH

- X-linked hypophosphatemia.

References

- 1. Eicher EM, Southard JL, Scriver CR, Glorieux FH. 1976. Hypophosphatemia: mouse model for human familial hypophosphatemic (vitamin D-resistant) rickets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 73:4667–4671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu S, Guo R, Simpson LG, Xiao ZS, Burnham CE, Quarles LD. 2003. Regulation of fibroblastic growth factor 23 expression but not degradation by PHEX. J Biol Chem 278:37419–37426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bowe AE, Finnegan R, Jan de Beur SM, Cho J, Levine MA, Kumar R, Schiavi SC. 2001. FGF-23 inhibits renal tubular phosphate transport and is a PHEX substrate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 284:977–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, Stubbs JR, Luo Q, Pi M, Quarles LD. 2006. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is a counter-regulatory phosphaturic hormone for vitamin D. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:1305–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu S, Vierthaler L, Tang W, Zhou J, Quarles LD. 2008. FGFR3 and FGFR4 do not mediate renal effects of FGF23. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:2342–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saito H, Kusano K, Kinosaki M, Ito H, Hirata M, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Fukushima N. 2003. Human fibroblast growth factor-23 mutants suppress Na+-dependent phosphate co-transport activity and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production. J Biol Chem 278:2206–2211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. 2006. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature 444:770–77417086194 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brownstein CA, Zhang J, Stillman A, Ellis B, Troiano N, Adams DJ, Gundberg CM, Lifton RP, Carpenter TO. 2010. Increased bone volume and correction of HYP mouse hypophosphatemia in the Klotho/HYP mouse. Endocrinology 151:492–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Schiavi S, Hu MC, Moe OW, Kuro-o M. 2006. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem 281:6120–6123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, Yu X, Rauch F, Davis SI, Zhang S, Rios H, Drezner MK, Quarles LD, Bonewald LF, White KE. 2006. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet 38:1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. 2002. Fibroblast growth factor-23 is the phosphaturic factor in tumor-induced osteomalacia and may be phosphatonin. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 11:385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pagès A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Müller-Barth U, Badenhoop K, Kaiser SM, Rittmaster RS, Shlossberg AH, Olivares JL, Loris C, Ramos FJ, Glorieux F, Vikkula M, Jüppner H, Strom TM. 2006. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet 38:1248–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, Econs MJ. 2001. Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney Int 60:2079–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu X, White KE. 2005. FGF23 and disorders of phosphate homeostasis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 16:221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saito T, Shimizu Y, Hori M, Taguchi M, Igarashi T, Fukumoto S, Fujitab T. 2011. A patient with hypophosphatemic rickets and ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament caused by a novel homozygous mutation in ENPP1 gene. Bone 49:913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holm IA, Econs MJ, T. O. C 2003. Familial hypophosphatemia and related disorders. In: Glorieux F, Juppner H, Pettifor JM, eds. Pediatric bone: biology, diseases. San Diego: Academic Press; 603. –631 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Francis F, Strom TM, Hennig S, Böddrich A, Lorenz B, Brandau O, Mohnike KL, Cagnoli M, Steffens C, Klages S, Borzym K, Pohl T, Oudet C, Econs MJ, Rowe PS, Reinhardt R, Meitinger T, Lehrach H. 1997. Genomic organization of the human PEX gene mutated in X-linked dominant hypophosphatemic rickets. Genome Res 7:573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang L, Du L, Ecarot B. 1999. Evidence for Phex haploinsufficiency in murine X-linked hypophosphatemia. Mamm Genome 10:385–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Holm IA, Jan de Beur SM, Insogna KL. 2011. A clinician's guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res 26:1381–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burnstein MI, Lawson JP, Kottamasu SR, Ellis BI, Micho J. 1989. The enthesopathic changes of hypophosphatemic osteomalacia in adults: radiologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 153:785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polisson RP, Martinez S, Khoury M, Harrell RM, Lyles KW, Friedman N, Harrelson JM, Reisner E, Drezner MK. 1985. Calcification of entheses associated with X-linked hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. N Engl J Med 313:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Siegel BA, Reid IR, Whyte MP. 1989. X-linked hypophosphatemia in adults: prevalence of skeletal radiographic and scintigraphic features. Radiology 171:403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacobson JA, Kalume-Brigido M. 2006. Case 97: X-linked hypophosphatemic osteomalacia with insufficiency fracture. Radiology 240:607–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramonda R, Sfriso P, Podswiadek M, Oliviero F, Valvason C, Punzi L. 2005. [The enthesopathy of vitamin D-resistant osteomalacia in adults]. Reumatismo 57:52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reid IR, Hardy DC, Murphy WA, Teitelbaum SL, Bergfeld MA, Whyte MP. 1989. X-linked hypophosphatemia: a clinical, biochemical, and histopathologic assessment of morbidity in adults. Medicine 68:336–352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van de Wiele C, Dierckx RA, Weynants L, Simons M, Kaufman JM. 1996. Whole-body bone scan findings in X-linked hypophosphatemia. Clin Nucl Med 21:483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yost JH, Spencer-Green G, Brown LA. 1994. Radiologic vignette. X-linked hypophosphatemia (familial vitamin D-resistant rickets). Arthritis Rheum 37:435–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liang G, Katz LD, Insogna KL, Carpenter TO, Macica CM. 2009. Survey of the enthesopathy of X-linked hypophosphatemia and its characterization in Hyp mice. Calcif Tissue Int 85:235–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soehle M, Casey AT. 2002. Cervical spinal cord compression attributable to a calcified intervertebral disc in a patient with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 51:239–242; discussion 242–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glorieux FH, Marie PJ, Pettifor JM, Delvin EE. 1980. Bone response to phosphate salts, ergocalciferol, and calcitriol in hypophosphatemic vitamin D-resistant rickets. N Engl J Med 303:1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sullivan W, Carpenter T, Glorieux F, Travers R, Insogna K. 1992. A prospective trial of phosphate and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 therapy in symptomatic adults with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75:879–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mäkitie O, Pereira RC, Kaitila I, Turan S, Bastepe M, Laine T, Kröger H, Cole WG, Jüppner H. 2010. Long-term clinical outcome and carrier phenotype in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia caused by a novel DMP1 mutation. J Bone Miner Res 25:2165–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miao D, Bai X, Panda DK, Karaplis AC, Goltzman D, McKee MD. 2004. Cartilage abnormalities are associated with abnormal Phex expression and with altered matrix protein and MMP-9 localization in Hyp mice. Bone 34:638–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson DL, Sabbagh Y, Tenenhouse HS, Roche PC, Drezner MK, Salisbury JL, Grande JP, Poeschla EM, Kumar R. 2002. Ontogeny of Phex/PHEX protein expression in mouse embryo and subcellular localization in osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res 17:311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. 2000. The cell and developmental biology of tendons and ligaments. Int Rev Cytol 196:85–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, Bydder G, Best TM, Milz S. 2006. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites ('entheses') in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat 208:471–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu S, Brown TA, Zhou J, Xiao ZS, Awad H, Guilak F, Quarles LD. 2005. Role of matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein in the pathogenesis of X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:1645–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu S, Zhou J, Tang W, Jiang X, Rowe DW, Quarles LD. 2006. Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Hyp mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291:E38–E49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bai X, Miao D, Li J, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. 2004. Transgenic mice overexpressing human fibroblast growth factor 23 (R176Q) delineate a putative role for parathyroid hormone in renal phosphate wasting disorders. Endocrinology 145:5269–5279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liang G, Vanhouten J, Macica CM. 2011. An atypical degenerative osteoarthropathy in Hyp mice is characterized by a loss in the mineralized zone of articular cartilage. Calcif Tissue Int 89:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Benjamin M, Kumai T, Milz S, Boszczyk BM, Boszczyk AA, Ralphs JR. 2002. The skeletal attachment of tendons—tendon “entheses.” Comp Biochem Physiol 133:931–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Bernard B, Bianco P, Bonucci E, Costantini M, Lunazzi GC, Martinuzzi P, Modricky C, Moro L, Panfili E, Pollesello P, et al. 1986. Biochemical and immunohistochemical evidence that in cartilage an alkaline phosphatase is a Ca2+-binding glycoprotein. J Cell Biol 103:1615–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rufai A, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. 1992. Development and ageing of phenotypically distinct fibrocartilages associated with the rat Achilles tendon. Anat Embryol 186:611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gao J, Messner K, Ralphs JR, Benjamin M. 1996. An immunohistochemical study of enthesis development in the medial collateral ligament of the rat knee joint. Anat Embryol 194:399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brown DC, Vogel KG. 1989. Characteristics of the in vitro interaction of a small proteoglycan (PG II) of bovine tendon with type I collagen. Matrix 9:468–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vogel KG. 2004. What happens when tendons bend and twist? Proteoglycans. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 4:202–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. 1998. Fibrocartilage in tendons and ligaments—an adaptation to compressive load. J Anat 193 ( Pt 4):481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Waggett AD, Ralphs JR, Kwan AP, Woodnutt D, Benjamin M. 1998. Characterization of collagens and proteoglycans at the insertion of the human Achilles tendon. Matrix Biol 16:457–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lu XL, Miller C, Chen FH, Guo XE, Mow VC. 2007. The generalized triphasic correspondence principle for simultaneous determination of the mechanical properties and proteoglycan content of articular cartilage by indentation. J Biomech 40:2434–2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lu XL, Mow VC, Guo XE. 2009. Proteoglycans and mechanical behavior of condylar cartilage. J Dent Res 88:244–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu XL, Sun DD, Guo XE, Chen FH, Lai WM, Mow VC. 2004. Indentation determined mechanoelectrochemical properties and fixed charge density of articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng 32:370–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carpenter TO, Keller M, Schwartz D, Mitnick M, Smith C, Ellison A, Carey D, Comite F, Horst R, Travers R, Glorieux FH, Gundberg CM, Poole AR, Insogna KL. 1996. 24,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D supplementation corrects hyperparathyroidism and improves skeletal abnormalities in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets—a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:2381–2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Adams JE, Davies M. 1986. Intra-spinal new bone formation and spinal cord compression in familial hypophosphataemic vitamin D resistant osteomalacia. Q J Med 61:1117–1129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dugger GS, Vandiver RW. 1966. Spinal cord compression caused by vitamin D resistant rickets. J Neurosurg 25:300–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dunlop DJ, Stirling AJ. 1996. Thoracic spinal cord compression caused by hypophosphataemic rickets: a case report and review of the world literature. Eur Spine J 5:272–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Highman JH, Sanderson PH, Sutcliffe MM. 1970. Vitamin-D-resistant osteomalacia as a cause of cord compression. Q J Med 39:529–537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Johnston CC, Jr, Kurlander GJ, Smith DM, Goodman JM, Campbell RL. 1966. Familial vitamin D resistant rickets in untreated adult. Bony proliferation of neural arches with cord compression. Arch Intern Med 117:141–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yoshikawa S, Shiba M, Suzuki A. 1968. Spinal-cord compression in untreated adult cases of vitamin-D resistant rickets. J Bone Joint Surg Am 50:743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vogel KG, Peters JA. 2005. Histochemistry defines a proteoglycan-rich layer in bovine flexor tendon subjected to bending. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 5:64–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kolek OI, Hines ER, Jones MD, LeSueur LK, Lipko MA, Kiela PR, Collins JF, Haussler MR, Ghishan FK. 2005. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link in a renal-gastrointestinal-skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physiol 289:G1036–G1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. 2005. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d metabolism in mice. Endocrinology 146:5358–5364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. 2001. Entheses—the bony attachments of tendons and ligaments. Ital J Anat Embryol 106:151–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomopoulos S, Kim HM, Rothermich SY, Biederstadt C, Das R, Galatz LM. 2007. Decreased muscle loading delays maturation of the tendon enthesis during postnatal development. J Orthop Res 25:1154–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Aono Y, Yamazaki Y, Yasutake J, Kawata T, Hasegawa H, Urakawa I, Fujita T, Wada M, Yamashita T, Fukumoto S, Shimada T. 2009. Therapeutic effects of anti-FGF23 antibodies in hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res 24:1879–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.