Brief summary

Viruses rely on host cell machinery for successful infection, while at the same time evading the host immune response. Characterization of these processes has revealed insights both into fundamental cellular processes as well as the nuances of viral replication. The recent advent of cell-based screening coupled with RNAi technology, has greatly facilitated studies focused on characterizing the virus-host interface and has expanded our understanding of cellular factors that impact viral infection. These findings have led to the discovery of potential therapeutic targets, but there is certainly more to be discovered. In this article we will review the recent progress in this arena and discuss the challenges and future of this emerging field.

Introduction

Viruses are obligate intracellular pathogens with a limited coding capacity and thus require host cell factors for their replication. Understanding how viruses exploit cellular machinery has greatly contributed to our knowledge of fundamental principles of cell biology including transcription factors, DNA replication, mRNA capping, RNA splicing, mRNA transport, vesicular trafficking and translation. This is because viral proteins interact with and regulate their host cell environment to facilitate replication using sophisticated strategies that interface with normal biological processes. The identification of host cell factors has been difficult in large part due to the lack of systematic methods for their identification. Recent technological breakthroughs have allowed for the explosion of new cell-based screening approaches to discover cellular factors involved in viral infection. These include affordable instrumentation for processing in high density microtiter plates (e.g. 384 well), coupled with sensitive readers and off-the-shelf analysis and informatics pipelines. Furthermore, genome sequencing coupled with accurate annotations have allowed for the development of new tools for genomic perturbations. Indeed, the discovery and development of robust RNA interference (RNAi) methodologies has opened the door to systematic loss-of-function screening. Additional robust and affordable unbiased screening methods including the identification of protein-protein interactions (yeast two hybrid, shotgun proteomics) and transcriptomics (microarrays, RNA-seq) can be coupled with cell-based screening technologies to allow for the rapid and systematic discovery of cellular genes that impact viral infection.

Previous reviews have focused on the description of particular RNAi screens targeting viral pathogens [1–6] and thus we will focus this review on recent advances in the field of high throughput cell based screens, outlining some of the technological limitations inherent in the system, and suggest some of the alternate approaches which can complement RNAi screens. Furthermore, we will discuss where the field can continue to make important contributions not only in understanding virus biology but also in identifying novel drug targets against virus infections.

Cell-based screening: Genetic versus chemical screening

The vast majority of antiviral therapeutics on the market inhibit a viral protein with catalytic activity. This is in large part due to the fact that viruses encode essential enzymes distinct from cellular genes making them amenable to specific therapeutic targeting. By applying high-throughput small molecule screening technologies, target-based enzymatic assays identify specific drugs that inhibit these essential viral proteins,. The growth of these small molecule libraries (>2M compounds) in the pharmaceutical industry has led to the development of robust screening technologies with decreasing cost. While these target-based biochemical assays were the choice du jour for many years, it has become clear that for many complex diseases, the best target protein for therapeutic intervention is unknown. Compound screening using cell-based assays readily provides tool compounds, but the path to a therapeutic or even the target is difficult. For studies with viruses, that have a limited coding capacity, it can be reasonably straightforward to determine if a given compound targets a viral protein. But if the compound does not function in this manner, the identification of the cellular target is less straightforward. With that said, recent studies have successfully used this strategy to discover important new targets. Using a small molecule library, REDD1 as a factor restricting influenza virus and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection, nieman pick C1 (NPC1) as a cellular receptor for Ebola virus and Protein kinase C ε (PKCε) as a factor required for Rift valley fever virus infection were identified [7–9]. Although the development of therapeutics using small molecule-based screening has been successful, reverse genetic screens overcome many of the limitations of small molecule screening as the gene-of-interest is revealed directly by the sequence of the perturbant in the well.

Loss of function vs gain of function

There are two basic approaches that can be applied in genetic screens. First, there are gain-of-function strategies where ectopic expression of cDNAs can probe gene function. While these tools initially relied on shotgun cloned cDNA libraries, the recent development of fully sequenced, full-length, arrayed cDNA libraries (e.g. MGC collection) has expanded the utility of these approaches. Second, the recent advent of RNAi methodologies has allowed for robust loss-of-function screening. There are a number of RNAi tools that can be used for this: small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) and long double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) which are commercially available and the most common reagents. Long dsRNAs are widely used in insect systems providing robust knock down and low off-target effects (reviewed in [10–13]. Unfortunately, due to the induction of type I interferon responses, long dsRNAs cannot be used in vertebrate systems. Rather, siRNAs and shRNAs which knockdown genes in a sequence specific manner are used in mammalian systems (reviewed in [14,15].

Genome-wide RNAi screen vs targeted small-scale screens

Genome-wide screening provides us with the most comprehensive and unbiased view of the cellular factors that impact viral infection. However, while these genome-wide screens are the most comprehensive, there are some cases in which more targeted small-scale screens can provide powerful insights. Firstly, genome-wide screens are costly, difficult to execute, and thus are typically performed only in duplicate using simple assays (typically add and read). In contrast, small-scale screens can provide insight into gene families (eg druggable genes, kinases) or focus on a particular biology (eg vesicular trafficking, lipid synthesis). Furthermore, they can be performed more robustly with more complex assays. To date, a number of small scale screens have been performed to identify candidates regulating diverse viruses. To identify possible druggable targets for HCV, siRNA screens were conducted using a human kinase library, which identified factors required for entry (e.g., EGFR, EPHA2) and those involved in replication (e.g. PI4KIIIalpha) [16,17]. Genome-wide RNAi screening by Tai et al. (using a sub-genomic replicon) and Brass et al. (using infectious HCV) also identified PI4KIIIalpha as an essential component in HCV replication but failed to identify EGFR and EPHA2[18,19]. Similarly, using a human druggable genome RNAi library, host factors involved in enterovirus (poliovirus, PV and coxsackie virus B, CVB) and Borna disease virus infection were identified revealing novel druggable candidates such as adenylate cyclases, LMTK2 (for PV and CVB), and ADAM17, cathepsin L (for BDV)[20,21]. In contrast, other groups have applied RNAi screening targeting specific cellular pathways which have led to the discovery of new genes involved in infection including Ars2 as antiviral against multiple RNA viruses [22–26]. A targeted membrane trafficking gene library revealed 7 genes including PI4KIIIalpha identified by others in larger screens as important for hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication [16,18,19,27]. Also, screening a sub-library against genes associated with pathways that have been shown to be critical for replication of other viruses revealed the role of fatty acid biosynthesis (FASN and ACACA), ER stress (ATF6, XBP1) and actin polymerization (CDC42 and DIAPH1) in dengue virus infection [28].

General workflow for arrayed cell-based screens

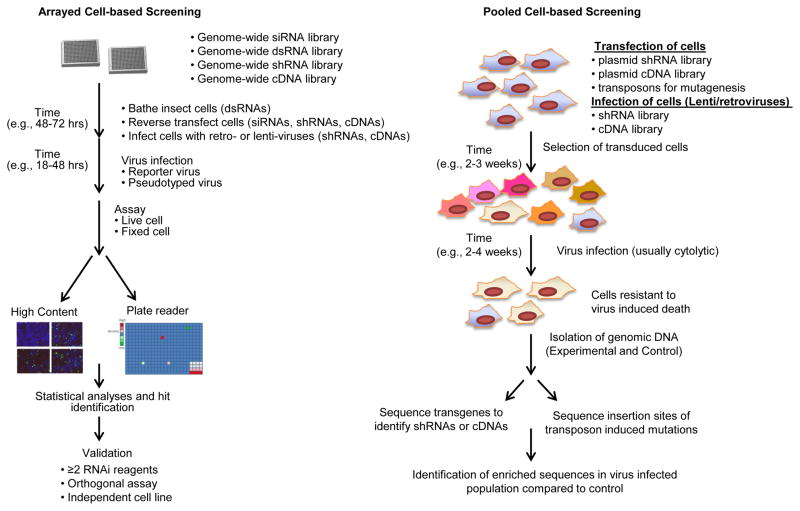

For a detailed description of the general protocol for RNAi screening, please refer to other more comprehensive reviews on this topic [29–33]. The general workflow for arrayed cell based screening is briefly outlined in Figure 1A. There are a variety of reagents available for RNAi screening, and these should be selected as appropriate for the cell type chosen and assay length. Long dsRNAs are potent and are routinely used in insect cell screens. siRNAs are potent, but require transfection, and are transient necessitating a short assay window. In contrast, shRNAs are delivered either in plasmid form or packaged into viruses (lenti- or retroviral) and can be delivered for long-term knock-down if the cells are selected for antibiotic resistance. In all of these cases, post-transduction, the cells must be challenged with the appropriate virus (or viral component) and an end-point must be chosen for assay read-out, typically using a plate-based whole-well read-out (eg luciferase) or image-based high-content read-out (eg. viral antigen production).

Fig. 1.

General workflow for arrayed cell based screening.

There are a number of important considerations in performing and optimizing cell-based screening. Once the virus of interest is identified, the appropriate cell-type must be chosen. Because these assays require robust differences, easily transfectable cell lines with stable properties are most readily adapted (e.g. HeLa, 293T, U2OS); however, since infected cells in vivo are more complex and specialized, attempts to screen in more relevant cell types are part of the future of screening. Indeed, a recent screen in polarized endothelial cells revealed novel aspects of enterovirus infection [20]. One important question that must be addressed prior to selecting the appropriate cell type is the biology that one is interested in. For example, is the screen meant to identify genes that impact a particular step in the lifecycle? If one can focus the assay on the biology interested in, then it’s more likely to reveal genes of interest. Generally, investigators have relied on the use of virally-expressed reporters because they are the most robust readouts; however, many viruses cannot be readily reverse engineered, necessitating the use of antibodies or more indirect read-outs. Normalization of cell number is an important consideration since many perturbants will impact the health of the cells. Indeed, the optimization of the screening assay will in part dictate the biology queried. The statistical criteria used both to optimize the assay (Z′>0.5 is standard) and to identify ‘hits’ is also an important consideration. A positive control which blocks infection can be used to optimize the screen for identifying required factors, while a positive control that leads to increased infection can be used to identified factors restricting infection. Further, different analysis algorithms will impact hit detection; in depth description of statistical analyses used in the RNAi screen can be found in [34]. Optimally, screens should have a low false negative and false positive rate. This is difficult to achieve, and the choice of cut-offs is largely based on decisions which lead to either a higher false negative or higher false positive rate. In order to minimize false negatives, more false positives may be tolerated in primary screens, but this increases the work and costs in the confirmation stage. Thus, a thorough, large and expensive hit triage plan is in many cases the mark of a good screen. Nevertheless, these choices contribute to the low overlap between seemingly similar screens [35–37]. Unfortunately, there is no absolute guideline to follow since these choices are somewhat subjective. However, combining statistical criteria with biological criteria (e.g. robust Z score with p<0.05 and a 2-fold cutoff) should help to guide data analysis to identify a reasonable primary gene list.

Performing the screen itself is of course just the beginning. As with any high-throughput platform, validation of the resulting gene list is essential. Ideally, for the secondary validation of RNAi screens, at a minimum more than one RNAi reagent should show a consistent phenotype. Furthermore, the use of an orthogonal assay in an independent cell type will remove much of the noise in these gene lists. Of course, the high confidence gene set should be used to generate hypotheses which are further explored, eventually leading to new mechanistic insight into virus-host interactions.

Cell-based screens and viruses

The initial genome-wide RNAi screens largely used viral infection as a read-out and focused on the identification of cellular factors required for infection [18,19,38–51]. These are listed in Table 1. A number of recent reviews have discussed these screens [3–6,35]. Surprisingly, in total, all of these screens report only 52 restriction factors. This may be partly due to the assay format used for these screens. For example, in the screen by Panda et al., the average percent infection was 60%, skewing the assay for discovery of factors that facilitate infection [45]. With that said, there have been some cell-intrinsic factors identified in genome-wide RNAi screens including IFITM1-3 which restricts influenza [42], and MCT4 which restricts WNV [51], suggesting that in fact restriction factors do exist but the assays have to be tuned to identify them. Subsequently, the importance of IFITM3 in vivo was demonstrated in mice where the IFITM3 mutant mice showed increased virus replication [52]. IFITM3 was also shown to be responsible for protection against influenza in humans as a single nucleotide polymorphism in IFITM3 allele impairs its ability to restrict influenza virus [52]. Since typical RNAi screens rely on depletion of the basal transcriptome and many antiviral factors are induced by viral infection, it may be difficult to identify such genes using simple RNAi approaches. Rather, ectopic expression may more robustly identify restriction factors. Early studies using cDNA libraries identified restriction factors including Zinc finger protein ZAP as a restriction factor against retroviruses [53]. And recently two groups took advantage of the fact that Interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) are likely antiviral effectors and screened ectopic expression of ISGs for those that restrict virus infection [54,55]. Collectively these studies, identified many novel antiviral regulators, and perhaps surprisingly, Schoggins et al., identified six ISGs that facilitate virus infection suggesting complex biological functions of type I interferons [54].

Table 1.

Genome-wide screens

| Virus | RNAi library (# genes) (Company) | Cell Type | Duration of RNAi | Infection length | Assay read out | Statistical analysis | Primary list | Type of secondary validation | Validated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-IIIB | 4siRNA/gene (21121 genes) Dharmacon | TZM-bl HeLa cells expressing CD4, CCR5 |

72h | 48h part1 24h part2 | IF and HCS for part1 and Beta-gal, plate reader for part2 | Z score | 386 VSF | Deconcolution of primary list | 273 VSF (≥1 siRNA) | Brass et al |

| VSV-G pseudotype HIV | 6 siRNA/gene and 2siRNA per well (19628 genes) Quiagen, Ambion | HEK 293T | 48h | 24h | Luciferase, plate reader | Redundant siRNA activity, ontology | 800 VSF | Deconvolution, Decision matrix based on microarray, protein interaction | 295 VSF | Konig et al. |

| HIV-HXB2 | 3 siRNA/gene (19709 genes) In house | P4/R5 HeLa derived |

24h | 48h | Beta-gal, plate reader | Strictly standardized mean difference | 390 VSF | Deconvolution | 232 Total 205 VSF 1 VRF |

Zhou et al. |

| HIV-NL4-3 | shRNA (54509 transcript and EST) System Biosciences | Jurkat | 3 weeks | 4 weeks | Microarray based barcoding detection | >2 fold enrichment over background | 252 VSF | Yeung et al. | ||

| HCV Genotype 1b replicon |

4 siRNA/gene (21094 genes) Dharmacon | Huh7/Rep/Feo replicon cell line | 72h | Luciferase, plate reader | Z score | 236 VSF | Deconvolution | 96 VSF | Tai et al. | |

| HCV JFH-1 |

Pool of 4 siRNA (19470 siRNA) Dharmacon |

Huh 7.5.1 | 72h | 48h part1 48 h part2 |

IF, HCS for part1 and 2 | Plate mean based comparison | 521 total 407 VSF and 114 VRF) |

Deconvolution | 262 Total 237 VSF 25 VRF |

Li et al. |

| WNV | Pool of 4 siRNA (21,121 genes) Dhamacon |

HeLa | 72h | 24h | IF, HCS | Z-Score | Deconvolution | 305 Total 283 VSF 22 VRF |

Krishnan et al | |

| VSV | 2siRNA per well, 2 wells per gene (22909 genes)Qiagen |

HeLa | 52h | 18h | GFP, HCS | Sum rank | 173 VSF | siRNA from Dharmacon, ≥3 independent siRNA scored as hit | 72 VSF | Panda et al. |

| Influenza PR8 |

Pool of 4 siRNA (17877 genes) Dharmacon |

U2OS | 72h | 12h | IF, HCS for part1 | Plate mean | 334 total 312 VSF 22 VRF | Deconvolution | 133 Total 129 VSF 4 VRF |

Brass et al. |

| Influenza WSN | 6 siRNA/gene and 2siRNA per well (19628 genes) Qiagen, Invitrogen, IDT | A549 | 48h | 12,24,36h | Luciferase, plate reader | Redundant siRNA activity, ontology | 624 VSF | Deconvolution | 295 VSF | Konig et al. |

| Influenza WSN | 4 siRNA per gene (23000 genes) Qiagen | A549 | 48h | 24h part1 16h part2 | IF, HCS for part1 and Luciferase, plate reader for part2 | Z score | 287 VSF | Deconvolution | 168 VSF | Karlas et al. |

| Papilloma virus | 4 siRNA per gene (21121 genes) Dharmacon | C33A cells expressing BPV E2 and IL2α | 72h | Luciferase, plate reader | Z score | 511 VSF | Deconvolution | 311 1 siRNA and 130 ≥ 2 siRNAs | Smith et al. | |

| SV40 | 200000 shRNA, (47400 human transcripts) System Biosciences | HeLa E6 cells | 2d,5d,14d | At 14d post shRNA transduction | Cell proliferation, visual selection | Not reported | Not reported | Goodwin et al. | ||

| Influenza VSVG pseudotyped |

dsRNA (13071 genes) Ambion | Drosophila DL1 | 48h | 24h | Luciferase, plate reader | Plate mean | 176 VSF | Independent dsRNA | 110 VSF | Hao et al. |

| DENV Drosophila adapted Dengue-2 | 22632 dsRNA DRSC | Drosophila D.mel 2 cells | 48h | 72h | IF, HCS | Sum rank | 218 VSF | Independent dsRNA | 116 VSF | Sessions et al. |

| DCV | 21000 dsRNA DRSC | Drosophila S2 | 72h | 24h | IF, HCS | Visual difference | 210 VSF | Independent dsRNA | 112 VSF | Cherry et al. |

Abbreviations: Drosophila C virus, DCV; Dengue virus, DENV;, Vesicular stomatitis virus, VSV; Hepatitis C virus, HCV; West Nile virus, WNV; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; Simian virus 40, SV40; Virus susceptibility factor, VSF; Virus resistance factor, VRF; Immunofluorescence staining, IF; high content screening, HCS; Drosophila RNAi Screening Center, DRSC.

New technologies are also providing additional methods to identify host factors that are required for infection. Indeed pooled library screening has become more robust with the advent of high-throughput sequencing. The workflow for these screens is depicted in Figure 1B. Although the pooled shRNA screens are in general lengthier compared to siRNA screens, they offer durable gene knockdown and can be used in hard to transfect cells. Furthermore, insertional mutagenesis in populations and then challenging with viruses followed by high-throughput sequencing of insertion sites can reveal interrupted genes that likely confer resistance expanding our knowledge of host factor required for virus-induced cytotoxicity. While historically, this has been difficult due to the diploid redundancy of genomes, the development of a haploid cell system has been pioneered to identify factors required for influenza virus[56] and more recently, NPC1 as a cellular receptor for Ebola virus [57]. Another technical development is of random homozygous gene perturbation (RHZP) that can deplete both copies of genes in a diploid genome, this system was used to identify genes required for a number of viruses including influenza and HIV [58–63]. Using this system, Murray et al., identified Rab9 as a factor required for infection of several enveloped viruses such as Marburg virus, measles virus, HIV and Ebola virus [59]. Furthermore, a number of cytoskeletal associated proteins, insulin growth factor II (IGF-II) pathway and a putative cell surface protein OL-16 were identified as factors required for reovirus infection [61,63].

Comparative phenotype profiling

To gain additional insight into these host factor dependencies, an effort has been made to determine the spectrum of viruses within a family and between families that hijack a given cellular factor or process. This analysis is complicated by the fact that there is seemingly only a modest overlap between RNAi screens against the same virus (reviewed in [4–6,36]; however, this has been overcome in some cases when the comparisons are made within the same group. Coyne et al. performed a comparative screen between poliovirus and coxsackievirus B (CVB) infections of polarized endothelial cells and found more than 70% overlap between the host factor dependency [20]. Panda et al., compared their validated gene set and found that 35% of the validated genes that promote VSV infection are also required by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) [45]. Furthermore, there was high overlap among flavivirus dependencies [51]. But perhaps the most surprising finding is that the COPI complex has been identified and validated as required for many of the viruses tested including influenza, VSV, LCMV, HPIV3, HCV, Drosophila C virus (DCV) and poliovirus [18,42–45,64].

The future: more sophisticated assays and phenotypes

The initial virus RNAi screens largely relied on simple read-outs focusing on either a simple reporter or antigen expressed during viral replication, thereby monitoring many steps in the viral life cycle simultaneously. However, as the technology becomes more robust, the assays and the complex cell biological interactions between viruses and hosts will be more thoroughly explored. In fact some recent genome-wide RNAi screens set the foundation to reveal complex phenotypes. A high-content screen by Orvedahl et al., identified cellular genes which regulate Sindbis induced virophagy but not cellular autophagy by looking at co-localization between SINV capsid protein and an autophagic marker [65]. Another, approach involved a synthetic lethal RNAi screen wherein the authors screened for genes whose depletion in multiple cancer cell lines led to increased virus-induced cytotoxicity by a rhabdovirus maraba virus, identifying the ER stress response[66]. Zhao et al. performed a genome-wide siRNA screen in the presence of interferon, scoring genes that when depleted led to increased infection, and validated 93 genes including several new genes that are required for this antiviral pathway [67].

The future: combining cell-based screens with other ‘omics approaches

The explosion of genomic technology has opened the door to more comprehensive mapping of interactions. Functional genomics including protein-protein interactions and transcriptional profiling can be combined with cell-based screening strategies to elucidate the ‘systems biology’ of virus-host interactions. In a recent article Shapira, et al., combined yeast two hybrid analysis and gene expression profiling to generate a network of host proteins interacting with influenza virus proteins [68] which generated a directed gene set which they used for RNAi screening and led to the discovery of WNT signaling playing a regulatory role in influenza infection. Likewise, Konig et al., analyzed gene expression profiles and yeast two-hybrid analysis and integrated these results with the results obtained in their genome-wide RNAi screen and developed comprehensive map of regulators of HIV infection [39]. Thus, proteomics can be used to generate a candidate set to be tested with RNAi screening. This approach has been applied to discover host factors incorporated into Ebola virions that play functional roles in viral infection [69].

Another increasingly used strategy takes advantage of the NCI60 cell line panel for which there is available microarray data. By correlating gene expression patterns with viral infectivity, genes predictive for Adeno associated virus 5 infection and ebola virus infection were tested using RNAi, leading to the identification of novel genes important for virus infection [70,71].

Challenges and the future of cell-based screening in viral-host discovery

While the last decade has certainly seen an explosion in the use of cell-based genomic screening, there are certainly areas in need of improvement. First and foremost is the need to increase the robustness and validation of gene lists from cell-based screens. This would be aided by more potent and selective RNAi reagents, since the technology is fraught with weak silencing and off-target effects [72–74]. Second, more sophisticated and user-friendly statistical models that take into account the non-normal distribution of data, and the need to superimpose prior biological knowledge on the data will improve the results. Third, as the instrumentation improves and more diverse add-and-read assays are developed, this will facilitate more complex assays, probing individual steps in the viral lifecycle, and important aspects of innate antiviral restriction. Furthermore, as genomic screening methodology has become more standardized, defined requirements for publication is needed. The MIARE (Minimum Information About an RNAi Experiment) and MIACA (Minimum Information about a cellular assay) guidelines are being recognized as information standards. Collaborative efforts between different agencies and laboratories will help to streamline data presentation and validation methods in order to establish best practices for data analysis from complementary screens. Indeed, the lack of public repositories for this primary and secondary data has made the comparative analysis of these data sets difficult. Model organisms including C. elegans and Drosophila have already generated such databases and this should be a priority going forward (e.g. GenomeRNAi and NCBI pubchem database). However, even if the primary data sets are more robust and available on the web, criteria for validation of primary screen data should also be established. Many use the criteria of ≥2 independent RNAi reagents as the gold standard. While this is certainly a minimum, we would suggest that validation requires an orthogonal assay and independent cell line, a condition that will greatly improve the robustness of screen-derived gene lists. Indeed, identification of mechanism-of-action should be the goal of these studies. Altogether, no single approach can reveal the ‘system’ at play and therefore, the integration of different ‘omics’ technologies will allow us to have an unprecedented insight into virus-host interactions. While many challenges remain, improved methodology combined with advancing technology promise to yield significant breakthroughs in our understanding of virus-host interactions.

Highlight.

Various cell based approaches to uncover virus-host interactions are reviewed.

Recent discoveries of some genes and pathways using different cell based screening approaches discussed.

Comparisons of strengths and weakness of some of the cell-based screening strategies were assessed.

Integration of multiple high-throughput ‘omics’ approaches may open new avenues.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank C. Coyne and M. Tudor for critically reading the manuscript and helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. (R01AI074951, U54AI057168 and R01AI095500) to SC. S.C. is a recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cherry S. What have RNAi screens taught us about viral-host interactions? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch AJ. The use of RNAi-based screens to identify host proteins involved in viral replication. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:303–311. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pache L, Konig R, Chanda SK. Identifying HIV-1 host cell factors by genome-scale RNAi screening. Methods. 2011;53:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stertz S, Shaw ML. Uncovering the global host cell requirements for influenza virus replication via RNAi screening. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meliopoulos VA, Andersen LE, Birrer KF, Simpson KJ, Lowenthal JW, Bean AG, Stambas J, Stewart CR, Tompkins SM, van Beusechem VW, et al. Host gene targets for novel influenza therapies elucidated by high-throughput RNA interference screens. FASEB J. 2012;26:1372–1386. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-193466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Kawaoka Y. Cellular networks involved in the influenza virus life cycle. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.008. A comprehensive review on host factor involvement in Influenza infection. This review did pair-wise comparisons between published genome-wide screens and sheds light on critical host factor involvement in influenza life cycle. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Mata MA, Satterly N, Versteeg GA, Frantz D, Wei S, Williams N, Schmolke M, Pena-Llopis S, Brugarolas J, Forst CV, et al. Chemical inhibition of RNA viruses reveals REDD1 as a host defense factor. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:712–719. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.645. Using a chemical library, these authors identified a small molecule that reversed influenza cytotoxicity and provied the evidence that the mechanism of action of this drug is through upregulation of host gene. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cote M, Misasi J, Ren T, Bruchez A, Lee K, Filone CM, Hensley L, Li Q, Ory D, Chandran K, et al. Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection. Nature. 2011;477:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filone CM, Hanna SL, Caino MC, Bambina S, Doms RW, Cherry S. Rift valley fever virus infection of human cells and insect hosts is promoted by protein kinase C epsilon. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakal C. Drosophila RNAi screening in a postgenomic world. Brief Funct Genomics. 2011;10:197–205. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry S. Genomic RNAi screening in Drosophila S2 cells: what have we learned about host-pathogen interactions? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumuller RA, Perrimon N. Where gene discovery turns into systems biology: genome-scale RNAi screens in Drosophila. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2011;3:471–478. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N. Drosophila genome-wide RNAi screens: are they delivering the promise? Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:141–148. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Q, van der Laan LJ, Janssen HL, Peppelenbosch MP. A dynamic perspective of RNAi library development. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao DD, Vorhies JS, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J. siRNA vs. shRNA: similarities and differences. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiss S, Rebhan I, Backes P, Romero-Brey I, Erfle H, Matula P, Kaderali L, Poenisch M, Blankenburg H, Hiet MS, et al. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lupberger J, Zeisel MB, Xiao F, Thumann C, Fofana I, Zona L, Davis C, Mee CJ, Turek M, Gorke S, et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:589–595. doi: 10.1038/nm.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Brass AL, Ng A, Hu Z, Xavier RJ, Liang TJ, Elledge SJ. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16410–16415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Coyne CB, Bozym R, Morosky SA, Hanna SL, Mukherjee A, Tudor M, Kim KS, Cherry S. Comparative RNAi screening reveals host factors involved in enterovirus infection of polarized endothelial monolayers. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.01.001. A comparative study for host factor requirement using two enteroviruses using the in vitro blood brain barrier model. This study identified host proteins co-opted by both poliovirus and coxsackie virus B in cells which recapitulates properties of blood brain barrier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemente R, Sisman E, Aza-Blanc P, de la Torre JC. Identification of host factors involved in borna disease virus cell entry through a small interfering RNA functional genetic screen. J Virol. 2010;84:3562–3575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02274-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabin LR, Zhou R, Gruber JJ, Lukinova N, Bambina S, Berman A, Lau CK, Thompson CB, Cherry S. Ars2 regulates both miRNA- and siRNA- dependent silencing and suppresses RNA virus infection in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;138:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espeseth AS, Fishel R, Hazuda D, Huang Q, Xu M, Yoder K, Zhou H. siRNA screening of a targeted library of DNA repair factors in HIV infection reveals a role for base excision repair in HIV integration. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavorgna A, Harhaj EW. An RNA interference screen identifies the Deubiquitinase STAMBPL1 as a critical regulator of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 tax nuclear export and NF-kappaB activation. J Virol. 2012;86:3357–3369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06456-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel S, Heger T, Mancini R, Herzog F, Kartenbeck J, Hayer A, Helenius A. Role of endosomes in simian virus 40 entry and infection. J Virol. 2011;85:4198–4211. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02179-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moser TS, Jones RG, Thompson CB, Coyne CB, Cherry S. A kinome RNAi screen identified AMPK as promoting poxvirus entry through the control of actin dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000954. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger KL, Cooper JD, Heaton NS, Yoon R, Oakland TE, Jordan TX, Mateu G, Grakoui A, Randall G. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902693106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heaton NS, Perera R, Berger KL, Khadka S, Lacount DJ, Kuhn RJ, Randall G. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010811107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coyne CB, Cherry S. RNAi screening in mammalian cells to identify novel host cell molecules involved in the regulation of viral infections. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;721:397–405. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-037-9_25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherry S. RNAi screening for host factors involved in viral infection using Drosophila cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;721:375–382. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-037-9_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma S, Rao A. RNAi screening: tips and techniques. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:799–804. doi: 10.1038/ni0809-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramadan N, Flockhart I, Booker M, Perrimon N, Mathey-Prevot B. Design and implementation of high-throughput RNAi screens in cultured Drosophila cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2245–2264. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Echeverri CJ, Perrimon N. High-throughput RNAi screening in cultured cells: a user’s guide. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:373–384. doi: 10.1038/nrg1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Birmingham A, Selfors LM, Forster T, Wrobel D, Kennedy CJ, Shanks E, Santoyo-Lopez J, Dunican DJ, Long A, Kelleher D, et al. Statistical methods for analysis of high-throughput RNA interference screens. Nat Methods. 2009;6:569–575. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1351. This article describes about different statistical approaches that can be applied to the RNAi dataset for hit identification. Also in this article, different quality control metrices and data normalization methods are described. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goff SP. Knockdown screens to knockout HIV-1. Cell. 2008;135:417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Bushman FD, Malani N, Fernandes J, D’Orso I, Cagney G, Diamond TL, Zhou H, Hazuda DJ, Espeseth AS, Konig R, et al. Host cell factors in HIV replication: meta-analysis of genome-wide studies. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000437. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000437. Using published data from nine genome-wide studies, these authors conducted a meta-analysis of host factors required for HIV infection. Pair-wise comparion between RNAi screens revealed genes most likely to be authentic required factor for HIV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Barrows NJ, Le Sommer C, Garcia-Blanco MA, Pearson JL. Factors affecting reproducibility between genome-scale siRNA-based screens. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:735–747. doi: 10.1177/1087057110374994. This article sheds light on factors that influence reproducibility in two near-identical siRNA screens and compares different statistical analyses for hit identification. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, Yan N, Engelman A, Xavier RJ, Lieberman J, Elledge SJ. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konig R, Zhou Y, Elleder D, Diamond TL, Bonamy GM, Irelan JT, Chiang CY, Tu BP, De Jesus PD, Lilley CE, et al. Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou H, Xu M, Huang Q, Gates AT, Zhang XD, Castle JC, Stec E, Ferrer M, Strulovici B, Hazuda DJ, et al. Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeung ML, Houzet L, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT. A genome-wide short hairpin RNA screening of jurkat T-cells for human proteins contributing to productive HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19463–19473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, Ryan BJ, Weyer JL, van der Weyden L, Fikrig E, et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. Using a genome-wide RNAi screen, identified a new family of restriction factors broadly antiviral against disparate RNA viruses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karlas A, Machuy N, Shin Y, Pleissner KP, Artarini A, Heuer D, Becker D, Khalil H, Ogilvie LA, Hess S, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies human host factors crucial for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konig R, Stertz S, Zhou Y, Inoue A, Hoffmann HH, Bhattacharyya S, Alamares JG, Tscherne DM, Ortigoza MB, Liang Y, et al. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panda D, Das A, Dinh PX, Subramaniam S, Nayak D, Barrows NJ, Pearson JL, Thompson J, Kelly DL, Ladunga I, et al. RNAi screening reveals requirement for host cell secretory pathway in infection by diverse families of negative-strand RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19036–19041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113643108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cherry S, Doukas T, Armknecht S, Whelan S, Wang H, Sarnow P, Perrimon N. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals a specific sensitivity of IRES-containing RNA viruses to host translation inhibition. Genes Dev. 2005;19:445–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1267905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao L, Sakurai A, Watanabe T, Sorensen E, Nidom CA, Newton MA, Ahlquist P, Kawaoka Y. Drosophila RNAi screen identifies host genes important for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2008;454:890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature07151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sessions OM, Barrows NJ, Souza-Neto JA, Robinson TJ, Hershey CL, Rodgers MA, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G, Yang PL, Pearson JL, et al. Discovery of insect and human dengue virus host factors. Nature. 2009;458:1047–1050. doi: 10.1038/nature07967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith JA, White EA, Sowa ME, Powell ML, Ottinger M, Harper JW, Howley PM. Genome-wide siRNA screen identifies SMCX, EP400, and Brd4 as E2-dependent regulators of human papillomavirus oncogene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3752–3757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914818107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodwin EC, Lipovsky A, Inoue T, Magaldi TG, Edwards AP, Van Goor KE, Paton AW, Paton JC, Atwood WJ, Tsai B, et al. BiP and multiple DNAJ molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum are required for efficient simian virus 40 infection. MBio. 2011;2:e00101–00111. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00101-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnan MN, Ng A, Sukumaran B, Gilfoy FD, Uchil PD, Sultana H, Brass AL, Adametz R, Tsui M, Qian F, et al. RNA interference screen for human genes associated with West Nile virus infection. Nature. 2008;455:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature07207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Everitt AR, Clare S, Pertel T, John SP, Wash RS, Smith SE, Chin CR, Feeley EM, Sims JS, Adams DJ, et al. IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature. 2012;484:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao G, Guo X, Goff SP. Inhibition of retroviral RNA production by ZAP, a CCCH-type zinc finger protein. Science. 2002;297:1703–1706. doi: 10.1126/science.1074276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. This study used a cDNA based screen and tested involvement of ISGs in antiviral response. Identified several broad acting ISGs as well as virus specific ISGs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Aliyari R, Lu S, Cheng G. Systematic identification of type I and type II interferon-induced antiviral factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4239–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114981109. This study employed a cDNA based screening strategy to identify novel antiviral effectors to type I and type II interferons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Carette JE, Guimaraes CP, Varadarajan M, Park AS, Wuethrich I, Godarova A, Kotecki M, Cochran BH, Spooner E, Ploegh HL, et al. Haploid genetic screens in human cells identify host factors used by pathogens. Science. 2009;326:1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1178955. This study established a haploid genetic screen and demonstraed its utility in virus-host interactions by identifying factors requried for Influenza virus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature. 2011;477:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sui B, Bamba D, Weng K, Ung H, Chang S, Van Dyke J, Goldblatt M, Duan R, Kinch MS, Li WB. The use of Random Homozygous Gene Perturbation to identify novel host-oriented targets for influenza. Virology. 2009;387:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murray JL, Mavrakis M, McDonald NJ, Yilla M, Sheng J, Bellini WJ, Zhao L, Le Doux JM, Shaw MW, Luo CC, et al. Rab9 GTPase is required for replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, filoviruses, and measles virus. J Virol. 2005;79:11742–11751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11742-11751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li WB, Zhu J, Hart B, Sui B, Weng K, Chang S, Geiger R, Torremorell M, Mileham A, Gladney C, et al. Identification of PTCH1 requirement for influenza virus using random homozygous gene perturbation. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:259–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Organ EL, Sheng J, Ruley HE, Rubin DH. Discovery of mammalian genes that participate in virus infection. BMC Cell Biol. 2004;5:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dziuba N, Ferguson MR, O’Brien WA, Sanchez A, Prussia AJ, McDonald NJ, Friedrich BM, Li G, Shaw MW, Sheng J, et al. Identification of Cellular Proteins Required for Replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012 doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63•.Sheng J, Organ EL, Hao C, Wells KS, Ruley HE, Rubin DH. Mutations in the IGF-II pathway that confer resistance to lytic reovirus infection. BMC Cell Biol. 2004;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-5-32. These authors used a gene trap insertional mutagenesis technique and identified novel genes involved in reovirus infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cherry S, Kunte A, Wang H, Coyne C, Rawson RB, Perrimon N. COPI activity coupled with fatty acid biosynthesis is required for viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orvedahl A, Sumpter R, Jr, Xiao G, Ng A, Zou Z, Tang Y, Narimatsu M, Gilpin C, Sun Q, Roth M, et al. Image-based genome-wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors. Nature. 2011;480:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66•.Mahoney DJ, Lefebvre C, Allan K, Brun J, Sanaei CA, Baird S, Pearce N, Gronberg S, Wilson B, Prakesh M, et al. Virus-tumor interactome screen reveals ER stress response can reprogram resistant cancers for oncolytic virus-triggered caspase-2 cell death. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.005. Using a rhabdovirus induced cell death as a marker, this study identify several novel pathways that sensitizes tumor cells to selective oncolysis. This study demonstrates the utility of genome-wide RNAi screens to search for novel modulator of virotherapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Zhao H, Lin W, Kumthip K, Cheng D, Fusco DN, Hofmann O, Jilg N, Tai AW, Goto K, Zhang L, et al. A functional genomic screen reveals novel host genes that mediate interferon-alpha’s effects against hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol. 2012;56:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.026. Functional genomics was used along with IFN treatment to discover novel antiviral molecules for HCV. Identified several new genes including SART1 as novel antiviral effector of IFN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shapira SD, Gat-Viks I, Shum BO, Dricot A, de Grace MM, Wu L, Gupta PB, Hao T, Silver SJ, Root DE, et al. A physical and regulatory map of host-influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 2009;139:1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.018. A combination of gene expression and RNAi was used to converge on host factors reqired for influenza virus infection. Identified several new genes and pathways in influenza virus infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spurgers KB, Alefantis T, Peyser BD, Ruthel GT, Bergeron AA, Costantino JA, Enterlein S, Kota KP, Boltz RC, Aman MJ, et al. Identification of essential filovirion-associated host factors by serial proteomic analysis and RNAi screen. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2690–2703. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70•.Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, Martins I, Scudiero D, Monks A, Chiorini JA. Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction. Nat Med. 2003;9:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm929. This article used the microarray data for a panel of cancer cell line and by a corelative analysis identified AAV-5 receptor. This shows the use of gene expression data to identify important regulator of virus infection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kondratowicz AS, Lennemann NJ, Sinn PL, Davey RA, Hunt CL, Moller-Tank S, Meyerholz DK, Rennert P, Mullins RF, Brindley M, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) is a receptor for Zaire Ebolavirus and Lake Victoria Marburgvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8426–8431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krueger U, Bergauer T, Kaufmann B, Wolter I, Pilk S, Heider-Fabian M, Kirch S, Artz-Oppitz C, Isselhorst M, Konrad J. Insights into effective RNAi gained from large-scale siRNA validation screening. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:237–250. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fellmann C, Zuber J, McJunkin K, Chang K, Malone CD, Dickins RA, Xu Q, Hengartner MO, Elledge SJ, Hannon GJ, et al. Functional identification of optimized RNAi triggers using a massively parallel sensor assay. Mol Cell. 2011;41:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huesken D, Lange J, Mickanin C, Weiler J, Asselbergs F, Warner J, Meloon B, Engel S, Rosenberg A, Cohen D, et al. Design of a genome-wide siRNA library using an artificial neural network. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nbt1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]