Abstract

Interactions between the embryonic pial basement membrane (PBM) and radial glia (RG) are essential for morphogenesis of the cerebral cortex, as disrupted interactions cause cobblestone malformations. To elucidate the role of dystroglycan (DG) in PBM-RG interactions, we studied the expression of DG protein and Dag1 mRNA (which encodes DG protein) in developing cerebral cortex, and analyzed cortical phenotypes in Dag1 CNS conditional mutant mice. In normal embryonic cortex, Dag1 mRNA was expressed in the ventricular zone, which contains RG nuclei whereas DG protein was expressed at the cortical surface on RG endfeet. Breaches of PBM continuity appeared during early neurogenesis in Dag1 mutants. Diverse cellular elements streamed through the breaches to form leptomeningeal heterotopia that were confluent with the underlying residual cortical plate and contained variably truncated RG fibers, many types of cortical neurons, and radial and intermediate progenitor cells. Nevertheless, layer-specific molecular expression appeared normal in heterotopic neurons, and axons projected to appropriate targets. Dendrites, however, were excessively tortuous and lacked radial orientation. These findings indicate that DG is required on RG endfeet to maintain PBM integrity and suggest that cobblestone malformations involve disturbances of radial glia structure, progenitor distribution, and dendrite orientation in addition to neuronal “overmigration.”

Keywords: Dystroglycan, cerebral cortex, cobblestone malformation, lissencephaly, leptomeningeal heterotopia

INTRODUCTION

Neuronal overmigration defects are a group of malformations characterized by ectopic migration of neurons beyond the glia limitans into the meningeal spaces and cobblestone lissencephaly (1–5). Depending on the extent and severity of the defects, neuronal overmigration can manifest pathologically as a nodular, polymicrogyric, or narrow residual cortex (6). In syndromes of cobblestone malformations with congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD), such as muscle-eye-brain disease, Walker-Warburg syndrome, and Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy, the defect is not with neurons but with signaling interactions between the pial basement membrane (PBM) and radial glia (RG) processes (7–12). Direct PBM-RG interactions are necessary to maintain PBM integrity, which is in turn essential to smoothly delimit the brain surface and maintain the glia limitans (13). Deficient PBM-RG signaling leads to ruptures in the PBM, thus opening a permissive environment for neuronal overmigration (13).

PBM-RG signaling is mediated by extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoproteins, particularly laminin, binding to transmembrane receptors expressed on RG endfeet (14). The key laminin receptors transducing this interaction include integrins and a brain form of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex. Generally, in the human cobblestone malformations associated with CMDs, ECM receptor signaling is attenuated as a result of deficient glycosylation of α-dystroglycan (α-DG), the laminin-binding subunit of dystroglycan (DG), a key glycoprotein component of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (15–20). Extensive glycosylation is essential for α-DG activities including laminin binding (14, 18, 22). Thus, whereas most cobblestone malformations in humans are linked to mutations in protein glycosylation genes, the key effect is to perturb functions of α-DG related to PBM-RG signaling. Accordingly, syndromes of cobblestone malformations with CMD are considered subtypes of dystroglycanopathy, a broad group of CMDs and limb-girdle muscular dystrophies, which may or may not be associated with brain and ocular malformations (OMIM#253800). The pathogenesis of cobblestone malformations has been studied in several mouse models produced by targeted mutation of genes involved in PBM-RG signaling mediated by integrins and DG. Some of these models have revealed surprisingly complex effects, involving multiple neurodevelopmental abnormalities in addition to neuronal overmigration and laminar disorganization. For example, in mice with a laminin mutation that interfered with binding to nidogen (an ECM-organizing molecule), the developing cerebral cortex showed ectopic RG progenitor proliferation, widespread retraction of RG end feet, focal RG fiber extension into heterotopia, gaps in the distribution of Cajal-Retzius (CR) cells, and spontaneous hemorrhages (23). Some of the same defects were also reported in mutants lacking β1-integrin, α6-integrin, glycosyltransferases that post-translationally modify dystroglycan, or signaling molecules such as FAK, a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, and ILK, a nonreceptor serine/threonine kinase, both of which are activated by integrin signaling (7–9, 22, 24–28).

In the present study, our goal was to investigate the pathogenesis of cobblestone malformations in dystroglycanopathy. Towards this goal, we studied mice with conditional inactivation of the DG gene, Dag1, in the embryonic CNS. This was accomplished by Cre-mediated recombination, using Nestin-Cre expressed in central neural stem cells to inactivate a floxed Dag1 allele in the embryonic brain and spinal cord (29). Conditional inactivation was necessary because complete Dag1 null mutants die during early gastrulation stages (30). Previous studies, using Gfap-Cre or Mox2-Cre to inactivate floxed Dag1 in RG progenitors or epiblast derivatives, respectively, have shown that adult mice lacking central DG indeed develop a severe cobblestone malformation characterized by abnormal cortical layering, meningeal heterotopia and fusion of the interhemispheric fissure (14, 31). These previous studies confirmed the importance of DG in brain development, but many questions have remained. The most fundamental of these is which cell types in the embryonic cortex express DG? Given the presumed role of DG in PBM-RG signaling, it has been assumed that DG is expressed by RG cells, but this has never been conclusively demonstrated. Other questions are, what are the effects of central DG deficiency on progenitor cells and RG fibers in the embryonic cortex? and how are the distribution and connections of cortical pyramidal neurons and interneurons affected?

In the present study, we verified that Dag1 mRNA is indeed expressed by RG cells in the embryonic ventricular zone (VZ), whereas DG protein is localized to RG endfeet in contact with the PBM. We also found that Dag1 inactivation led to ectopic proliferation of RG progenitors and intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs), as well as proliferation of progenitors within the VZ and subventricular zone (SVZ), despite RG fiber anomalies, and overmigration of all cortical neuron types into the leptomeninges. Despite severe dyslamination and abnormal dendrite orientation, ectopic pyramidal neurons established axonal connections with distant cortical and subcortical targets, consistent with the view that axon pathfinding does not require laminar organization or DG signaling. Our findings reveal that the pathogenesis of cobblestone malformation in dystroglycanopathy is more complex than previously understood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Nestin-Cre/dystroglycan null mice were generated as previously described (29), by breeding nestin-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratories) to Dag1 floxed mice (14). Expression of Cre-recombinase in nestin-Cre expressing cells, including neurogenic progenitors of the cerebrum, begins around E10.5 (25, 32). Breeders used to produce embryos and pups for these studies were male nestin-Cre+/Dag1L/+ and female Dag1L/L. DG null offspring were born in the expected Mendelian ratio. For timed-pregnancy matings, noon of the day that the vaginal plug was observed was considered E0.5. Pregnant dams were injected with 40 mg/kg bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) several days (migration studies) or 3 hours (proliferation studies) prior to death. Animal use procedures were approved by the University of Iowa IACUC.

Antibodies

The following rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used: anti-laminin (1:1000) and anti-γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, 1:2000) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); anti-Tbr1 (1:2500), anti-Tbr2 (1:2000) from the lab of R.F. Hevner (Seattle, WA), anti-βDG (1:25) [AP83 from the lab of K.P. Campbell (Iowa City, IA) (33)]; anti-Er81 (1:1500) from the lab of T. Jessell (New York, NY); anti-Rorβ (1:2000) from the lab of Henk Stunnenberg (Nijmegen, Netherlands); anti-phosphohistone-H3 (1:400) from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); anti-CDP (Cux1, 1:1000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-Dlx (1:75) from the lab of Jhumku D. Kohtz (Chicago, IL); anti-Dab1 (1:400) from the lab of Jonathan Cooper (Seattle, WA).

Mouse monoclonal antibodies used were anti-reelin (1:1000) from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); anti-neuronal-specific nuclear protein (NeuN, 1:1000), anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, 1:2000), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1000) from Chemicon (Temecula, CA); anti-α-DG (1:400, clone IIH6C4) from Upstate Biotechnology; anti-β-DG (1:50, clone 7D11), anti-Pax6 (1:2000), RC2 (1:25, ascites), anti-nestin (rat-401; 1:100) from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa City, IA).

Rat monoclonal antibodies used were anti-BrdU (1:200) from Accurate (Westbury, NY) and anti-CTIP2 (1:1000) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Immunohistochemistry

Brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 4% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline and embedded in OCT. Coronal, 12-µm cryostat sections of the cerebral cortex were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT) in blocking solution (phosphate buffered saline [PBS] containing 5% normal goat serum, 2% bovine serum albumin, and 1% Triton-X). Sections were briefly boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) up to 3 times for antigen retrieval and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at RT for 2 hours. Sections tested for BrdU staining were treated with 2N HCL at 37°C for 30 minutes prior to sodium citrate boils. Sections were counterstained with 0.01% DAPI (Sigma) or TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes) to label nuclei.

TUNEL Analysis

Coronal, 12-µm tissue sections were reacted using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol except for the permeabilization step, which was previously shown not to affect sensitivity. Sections were counterstained with DAPI to label nuclei.

In Situ Hybridization

A digoxigenin-labeled 1182 base pair mDag1 cDNA for riboprobes was subcloned from an mDag1 full-length cDNA clone (Accession #BC007150), using Pst1 sites to excise cDNA spanning part of the 3’ translated and untranslated regions. In situ hybridization was performed as previously described using 12-µm coronal sections (34).

Retrograde Axon and Radial Glial Basal Process Tracing

Embryos and brains from postnatal mice were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS with 4% sucrose. Brains were removed from the skull, dissected appropriately for the specific experiment, and then injected with the lipophilic carbocyanine tracer, DiI (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) and left to incubate in the dark at RT for between 1 day and 10 weeks, depending on the specific experiment. Brains were then embedded in 4% agarose in PBS and coronal 50- to 100-µm sections were made on a vibratome. Some sections were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies and counterstained with DAPI and TO-PRO-3, as described above.

Microscopy and Image Analysis

Sections were examined and digital images were made by epifluorescence microscopy (Nikon E600), laser scanning confocal microscopy (Bio-Rad Radiance LS2000), bright-field and Apotome epifluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axioimager Z1, Jena, Germany). Color inversion of DiA labeling and contrast, sharpness, and brightness of images were enhanced using Adobe Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). For in situ hybridization experiments with immunofluorescence, bright-field images of mDag1 signal were pseudocolored using Adobe Photoshop CS2.

RESULTS

Dag1 Is Expressed by Radial Glia in the Embryonic Ventricular Zone

Although the importance of DG in brain development has been confirmed in previous studies, the cell types in the embryonic cortex that express DG have not been well established. We examined Dag1 mRNA expression during early (E12.5), middle (E14.5 and E15.5), and late (E18.5) neurogenesis. Dag1 mRNA expression was low at E12.5 but was significantly higher at E15.5 and E18.5 (Fig. 1A-C). At all 3 time points, Dag1 mRNA expression was restricted to the VZ, except for a small amount of expression in the cortical plate (CP) at E15.5 and E18.5 during late stages of neurogenesis, consistent with data posted elsewhere (see Brain Gene Expression Map databank, accession # NM_010017, www.stjudebgem.org). Dag1 mRNA colocalized in ventricular zone cells with transcription factor Pax6, a marker of mainly RG (Fig. 1D). Pax6 is also expressed in some newly generated IPCs in the ventricular zone (35, 36).

Figure 1.

Dystroglycan (DG) is expressed by radial glia during neurogenesis. In Dag1+/+ (WT) brains, Dag1 mRNA expression is weak and restricted to the ventricular zone (VZ) at E12.5 (A) and E15.5 (B) and is mostly in the VZ, but also sporadically in cortical plate cells, at E18.5 (C). Dag1 mRNA is expressed in Pax6-positive radial glia (RG) soma in the VZ at E15.5 (D, E), but not at the pial basement membrane (PBM) where β-dystroglycan protein (β-DG) is expressed (E, arrowheads). β-DG is restricted to the glia limitans at the outermost aspect of the basal cortex at P0.5 (F, arrowheads; higher magnification in G). At E18.5, β-DG colocalizes with RC2-positive RG endfeet (H,arrow). Using high-magnification confocal microscopy, α-dystroglycan protein (α-DG) consistently colocalizes with the laminin-positive basement membrane (BM) at E12.5 (I), E14.5 (J), E15.5 (K), and E18.5 (L). (M-X) In Dag1 conditional KO (DG−/−) brains, Dag1 mRNA is absent at E12.5 (M), E15.5 (N), and E18.5 (O) and is not expressed in Pax6-positive RG soma (P). β-DG protein expression is irregular at E15.5 (Q, arrowheads) and absent at P0.5 (R, higher magnification in S). At E18.5, β-DG is not expressed in RC2-positive RG endfeet (T, arrow). α-DG colocalizes with the BM at E12.5 (U). By E14.5, α-DG is nearly absent whereas the BM remains mostly intact (arrowheads) with only small disruptions (arrow) (V). α-DG is entirely absent and there is widespread disruption of the BM at E15.5 (W, arrowheads). At E18.5, only small fragments of the BM remain (X, arrowheads). VZ, ventricular zone; BM, basement membrane; BV, blood vessel; WT, Dag1+/+; DG −/−, Dag1 cKO. Scale bars: A, C, D, M, O, P, 25 µm; B, E, F, N, Q, R, 50 µm; G-L, S-X, 12.5 µm.

The protein product of Dag1 is post-translationally processed into α-dystroglycan (α-DG) and β-dystroglycan (β-DG), 2 non-covalently linked subunits of the transmembrane dystrophin glycoprotein complex (37). Given the presumed role of DG in PBM-RG signaling, we examined the distribution of α-DG and β-DG in RG during neocortical histogenesis. β-DG was localized to the endfeet of RG basal processes at the outer surface of the neuroepithelium at the PBM and in association with meningeal and cortical blood vessels at E15.5 (Fig. 1E). The latter finding is most likely due to DG expression by vascular endothelial cells or (at later ages) astrocytes (38). There was no detectable β-DG expression within the remaining extent of the cortex, including the ventricular zone where Dag1 mRNA was located (Fig. 1E). At P0.5, β-DG expression appeared as a thin line of immunoreactivity predominantly at the PBM (Fig. 1F, G). β-DG expression colocalized with the terminal endfeet of RG basal processes, identified by antigen RC2 expression, where they attach to the PBM (Fig. 1H). Using high magnification confocal microscopy, α-DG protein expression was likewise consistently found to be limited to the RG endfeet-PBM interface throughout neurogenesis (as well as cerebral blood vessels) (Fig. 1I-L).

PBM-RG Interactions Mediated by DG Are Necessary for PBM Integrity

As expected, Dag1 mRNA expression was undetectable in E12.5, E15.5, and E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains, due to conditional loss of Dag1 expression by all nestin-expressing cells beginning at E10.5, including Pax6-positive RG in the neocortex (Fig. 1M-O). β-DG protein was present in association with meningeal blood vessels but was completely absent from RG basal processes by E18.5 (Fig. 1Q-T). In Dag1 cKO brains, α-DG protein immunoreactivity was similar to that observed in Dag1+/+ mice at E12.5, likely reflecting earlier expression of Dag1 by RG (or neuroepithelial cells) prior to the onset of nestin-Cre expression around E10.5, but weakened throughout the neurogenic period and was completely absent from the RG-PBM interface by E18.5 (Fig. 1U-X). Following a temporal pattern similar to the loss of dystroglycan protein from RG endfeet, the PBM developed gaps and became increasingly disrupted in Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 1U-X).

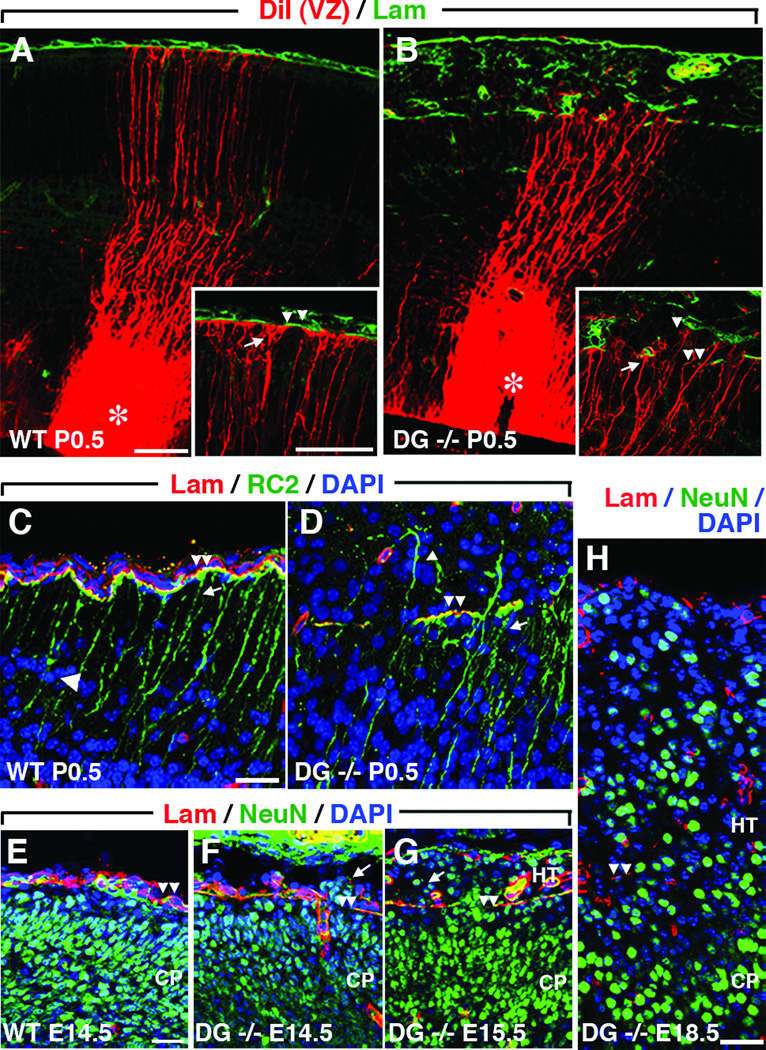

To investigate the effects of DG loss on RG basal process morphology and attachment to the PBM, we injected P0.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO cortical ventricular zones with the lipophilic carbocyanine dye, DiI. Immunoreactivity for nestin and for RC2, an intermediate filament-associated protein expressed only in RG, was also used to examine basal process morphology (39). All DiI-, nestin- (data not shown) and RC2-labeled RG basal processes in P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains terminated on intact PBM (Fig. 2A, C). In contrast, despite PBM disruptions at P0.5, RG basal processes in Dag1 cKO brains remained attached to residual islands of PBM (Fig. 2B, D). However, even in areas where RG-PBM attachment persisted at P0.5, RG basal processes lost the orderly, parallel radial arrangement that was characteristic of basal processes in Dag1+/+ brains and instead became severely disorganized (Fig. 2B, D). Furthermore, some RG basal processes extended beyond the original PBM into the meninges and often attached to ectopic fragments of PBM, thus contributing to the formation of leptomeningeal heterotopia (Fig. 2B, inset). Also, many NeuN-positive neurons were closely associated with RG basal processes below layer I in the CP of Dag1+/+ brains (Fig. 2C, single arrowhead), consistent with the normal migration of newborn pyramidal neurons along RG fibers during cortical histogenesis (40, 41). Neurons were similarly associated with RG fibers of Dag1 cKO brains; this association persisted ectopically into layer I (the marginal zone [MZ]) and the leptomeninges (Fig. 2D, single arrowhead).

Figure 2.

Basement membrane (BM) disintegration leads to radial glia (RG) fiber abnormalities and heterotopia (HT). (A) In a wild type (WT) Dag1+/+ brain, RG fibers (arrows) extend to the BM (arrowheads) (Higher magnification inset). (B) In a Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) brain, RG fibers attach to intact areas of the BM (arrow) and frequently extend into meningeal spaces through breaches in the BM (double arrowheads) where some fibers remain attached to ectopic BM (single arrowhead) (higher magnification in inset). (C) RC2-positive RG basal processes (arrow) terminate at the BM (arrowheads) and most neurons (single arrowhead) are closely associated with RG fibers in a P0.5 Dag1+/+ brain. (D) In a Dag1 cKO brain, some RG fibers (arrow) attach to intact BM (double arrowheads) whereas other RG fibers with closely associated neurons (single arrowhead) extend into the meninges (MG) through gaps in the BM. (E) The distribution of NeuN-positive cortical neurons is smoothly delimited at the glia limitans to the neuroepithelium by intact BM (arrowheads) in an E14.5 Dag1+/+ brain. (F) Small neuronal HT (arrows) are present directly above gaps in the BM (arrowheads) in an E14.5 Dag1 cKO brain. (G, H) Greater numbers of cortical neurons (arrow) are present in meningeal spaces above intact and disrupted (arrowheads) BM in a Dag1 cKO E15.5 brain (G) and by E18.5, the HT are large and confluent with small, underlying remnants of BM (arrowheads) (H). VZ, ventricular zone; CP, cortical plate. Scale bars: A, B, 50 µm; A, B insets, 50 µm; C, D, 25 µm; E-H, 100 µm.

PBM Disintegration Provides a Permissive Environment for Neuronal Overmigration

Intact PBM in Dag1+/+ brains smoothly delimited the brain surface and established the glia limitans below which CP neurons remained throughout embryogenesis (Fig. 2E). However, where breaches of the PBM arose in Dag1 cKO brains, there were ectopic clusters of neurons (heterotopia) in the meninges as early as E14.5 (Fig. 2F). As PBM defects became more widespread at E15.5 and most of the PBM was lost by E18.5, greater numbers of ectopic neurons accumulated beyond the glia limitans, resulting in a supracortical layer of neural tissue that was confluent with the underlying residual cortex (Fig. 2G, H). Displaced neurons and glia, either in intracerebral (e.g. periventricular), intracranial but extracerebral (e.g. meningeal) or extracranial locations (e.g. pulmonary), may be associated with various familial and spontaneous cerebral malformation disorders or fetal alcohol syndrome due to abnormal neuronal migration or as tumors in humans and laboratory rodents and are referred to as either neuroglial ectopia or heterotopia (6, 14, 42–47). Hereafter, we will refer to the supracortical accumulation of neurons and glia in Dag1 cKO brains as leptomeningeal heterotopia and displaced neurons or glia as heterotopic if they are within the leptomeninges or ectopic if they are in any abnormal location.

Proliferation of Heterotopic Progenitor Cells

Cerebrocortical pyramidal neurons are produced by 2 main types of progenitor cells, RG and IPCs, which are derived from RG (36). RG express transcription factor Pax6 and are restricted to the VZ (31). IPCs are produced by RG in the VZ, migrate into the SVZ, and express transcription factor Tbr2 (36). We classified RG or IPCs as ectopic if Pax6-positive nuclei or Tbr2-positive nuclei, respectively, were superficial to the cortical subplate. The subplate was defined as the lamina of the dorsal cortex immediately apical to the cell-dense CP (layer VI) and basal to the cell-sparse intermediate zone (IZ). At E14.5, when only small and infrequent disruptions of the PBM were present in Dag1 cKO brains, few ectopic RG or IPCs were observed in cortical slices of either Dag1 cKO brains or Dag1+/+ brains and there was no apparent difference in VZ thickness between these genotypes (Fig. 3E-G).

Figure 3.

Ectopic proliferating progenitor cells in the cortical plate and heterotopia of Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) brains. (A-G) As expected, Pax6-positive radial glia (RG) and Tbr2-positive intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs) are in the ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ), respectively, of E15.5 wild type (WT), Dag1+/+ and Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) (DG −/−) brains (A, B). There are, however, frequent ectopic Pax 6-positive RG (C, double arrowheads), Tbr2-positive IPCs (B, C, single arrow), and recently-born, Pax6-positive/Tbr2-positive IPCs (C, single arrowhead) that are present singly (B) and in large clusters (C) in the cortical plate and heterotopia (HT) above disrupted BM (B, double arrowheads) of E15.5, E18.5, and P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains (B, C, E, F). The VZ of Dag1 cKO brains (B, G) frequently appears slightly thinner than Dag1+/+ brains (A, G) at E15.5 and E18.5 but not at E14.5 or P0.5 (A, B, G). At P0.5, clusters of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes (double arrowheads) are present in heterotopia while heterotopic Pax6-positive radial glia (arrow) are GFAP-negative (D). (H-W) In E15.5 Dag1 cKO brains, heterotopic RG (I, K, single arrowhead), IPCs (N, O, single arrowhead), and heterotopic Pax6-positive/Tbr2-positive recently-born IPCs (Q, R, S, single arrow and arrowhead) are present above disrupted BM (K, O, S, double arrowheads) and frequently have condensed chromatin (mitotic figures) (H, L, P, arrowhead, and inset) and express PH3 (J, K, M, O, single arrowhead). Heterotopic RG (T, arrowhead), Tbr2-positive IPCs (U, arrowhead) and Tbr2- heterotopic cells (U, arrow) are acutely labeled with BrdU in E15.5 Dag1 cKO brains. Many heterotopic RG (V, arrows) and most heterotopic IPCs (W, arrows) express PCNA in E15.5 Dag1 cKO brains. CP, cortical plate. Scale bars: A, B, 50 µm; C, D, H-S, V, W, 25 µm; T, U, 12.5 µm. Y-axis, average cell number/coronal section, X-axis = time point (E, F); Y-axis = average VZ thickness (um), X-axis = time point (G).

Ectopic Pax6-positive radial glia, Tbr2-positive IPCs and Pax6-positive/Tbr2-positive cells (newly generated IPCs), located mostly in meningeal heterotopia, were common in E15.5 and E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains but were very rare in E15.5 and E18.5 wild type (WT) brains (Fig. 3A-C, E, F). Ectopic progenitor cells were present as single cells or in mixed clusters and varied widely in total numbers among different Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 3B, C, E, F,). No ectopic Pax6-positive cells in P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains expressed the astrocytic marker GFAP (Fig. 3D), but there were small clusters of GFAP-positive Pax6- astrocytic cells detected in meningeal heterotopia of P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains, consistent with previous findings (14).

The VZ of E15.5 and E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains was slightly thinner than that in Dag1+/+ brains, which may have been a result of RG overmigration from the VZ to ectopic locations or, possibly, apoptosis of RG in the VZ (Fig. 3A, B, G). Using the TUNEL method, we detected no increase of apoptotic cells in the VZ of E14.5, E15.5, or E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains (data not shown). At P0.5, the number of ectopic RG and IPCs in Dag1 cKO brains declined relative to E15.5 and E18.5 (Fig. 3E, F). This may have been a result of terminal differentiation of ectopic progenitors and reduced migration of additional progenitors from the VZ and SVZ; apoptosis of ectopic progenitors may have contributed to this decline as well, as rare (1–3 per 12-µm coronal section) apoptotic cells were seen in P0.5 Dag1 cKO heterotopia or CPs (data not shown).

Using multiple markers of mitotically-active cells, including expression of the phosphorylated form of histone-H3 (PHH3), chromatin condensation, acute BrdU incorporation, and expression of PCNA, we investigated whether ectopic RG and IPCs in Dag1 cKO brains were mitotically active despite being located outside of their normal progenitor niches (VZ and SVZ) (48, 49). In E15.5 and E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains, frequent ectopic RG and IPCs in the CP and heterotopia had condensed chromatin (mitotic figures) and expressed PH3, a marker of proliferating cells in G2 or M phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 3H-O). Ectopic Pax6/Tbr2 double-labeled cells, representing newly differentiating IPCs (36), were also relatively frequent in E15.5 and E18.5 Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 3D, arrow). These cells often showed mitotic chromatin (Fig. 3P-S). Many ectopic RG and IPCs were labeled with BrdU, a thymidine analog incorporated into DNA during S phase, after pregnant dams were injected 3 hours prior to euthanasia (Fig. 3T, U). In E15.5 Dag1 cKO brains, nearly half of ectopic RG (15/33, 45%) and two-thirds of ectopic IPCs (18/28, 64%) expressed PCNA (Fig. 3V, W).

Marked Dyslamination and Heterotopic Distribution of Diverse Cortical Neurons

We used layer and subtype-specific mRNA and protein expression of CP neurons to investigate the pathogenesis of dyslamination and heterotopia formation in Dag1 cKO brains (50). Upon completion of migration, CR cells normally reside in the embryonic MZ (postnatal layer I) immediately below the PBM where they produce and secrete reelin, a glycopeptide that is essential for proper lamination of radially migrating neurons (51, 52). In E14.5, E16.5, and P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains, CR cells were mostly horizontally oriented in a monolayer within the cell sparse MZ (Fig. 4A, C, E). Between E14.5, E16.5, and P0.5 in Dag1 cKO brains, increasing numbers of CR cells accumulated in meningeal heterotopia above gaps in the CR cell monolayer in the MZ (Fig. 4B, D, F, G). Deep to these CR cell layer gaps, the laminar pattern of the CP was disrupted and columns of cells extended through the gaps into heterotopia (Fig. 4D). Individual ectopic CR cells were scattered individually or in small numbers throughout meningeal heterotopia, but occasionally they formed clusters or, remarkably, formed monolayers along the outermost aspect of the meningeal heterotopia that resembled layer I of normal CPs (Fig. 4F, G).

Figure 4.

Cajal-Retzius (CR) cells and CTIP2-positive layer V neurons migrate through early basement membrane (BM) breaches into meningeal spaces. (A-G) Reelin-positive CR cells form a monolayer in the marginal zone (MZ, layer I) directly below intact pial basement membrane (BM) in wild type (WT) Dag1+/+ E14.5 (A, arrows), E16.5 (C), and P0.5 (E) brains. CR cells (B, arrow) migrate through small BM gaps in E14.5 Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) (DG−/−), brains. In E16.5 Dag1 cKO brains, many cortical plate (CP) neurons migrate into meningeal heterotopia (HT) through large gaps (double arrowheads) in the CR cell layer (D). At P0.5, most CR cells are in meningeal HT above disrupted BM (F, G, double arrowheads) and are arranged randomly (F, single arrowhead) in clusters (F, single arrow), and less frequently in single layers (G, single arrow) resembling layer I of WT cortical plates (CP). (H-M) Intact BM overlays layer V CTIP2-positive neurons in Dag1+/+ brains at E14.5 (H), E15.5 (J), and E18.5 (L). Between E14.5 (I), E15.5 (K), and E18.5 (M), CTIP2-positive neurons progressively accumulate in superficial CP layers and meningeal heterotopia of Dag1 cKO brains above disrupted BM. VZ, ventricular zone; SVZ, subventricular zone; IZ, intermediate zone. Scale bars: A, B, E–K, 25 µm; C, D, 50 µm; L, M, 100 µm.

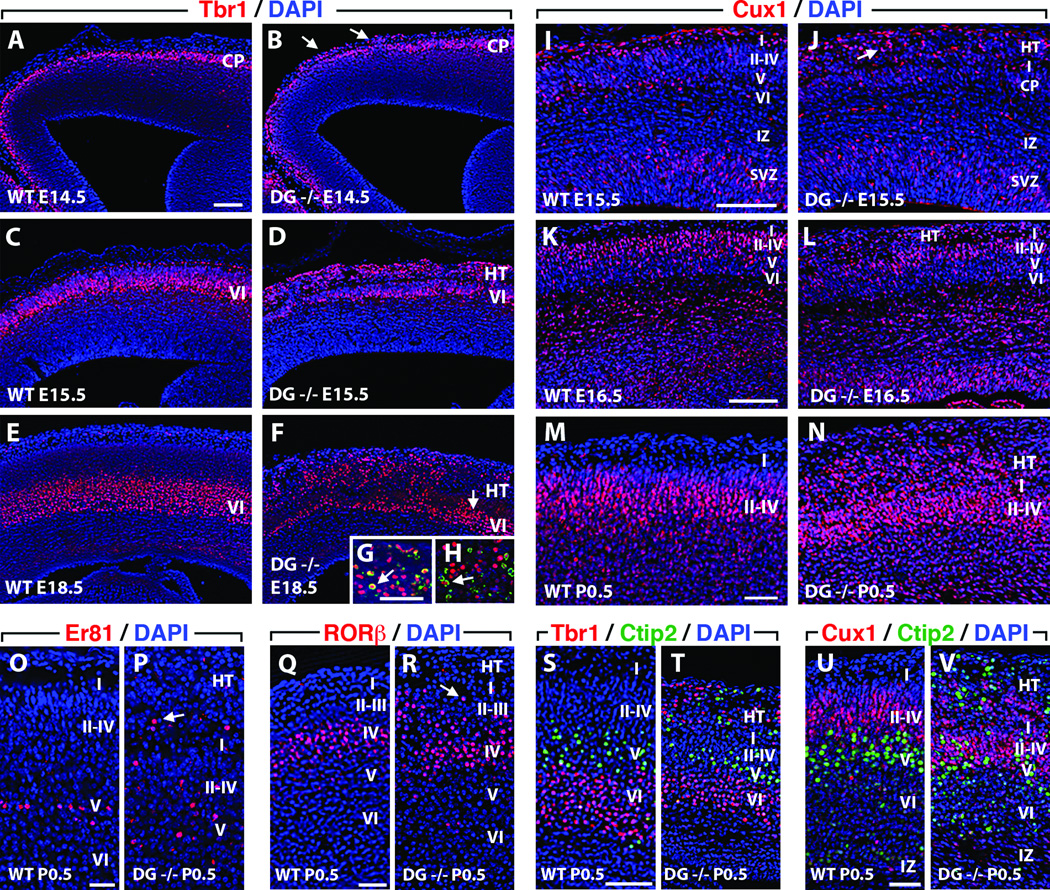

In both Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains, cells immunoreactive for CTIP2, a transcription factor expressed in early-born, subcerebral projection neurons, were present in layer V at E14.5, E15.5, and E18.5 (Fig. 4H-M) (53). However, in Dag1 cKO brains only, CTIP2-positive cells were also present in more superficial CP layers as well as in meningeal heterotopia, with a concurrent reduction of CTIP2-positive cells in layer V (Fig. 4I, K, M). Projection neurons and CR cells expressing Tbr1, a T-box transcription factor, were present in the subplate, layer VI, and the MZ of E14.5, E15.5, and E18.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 5A-F) (54). In Dag1 cKO brains, Tbr1-positive cells were also present in meningeal heterotopia overlying areas of the CP with substantial thinning of layer VI (Fig. 5B). The numbers of heterotopic Tbr1-positive cells and CTIP2-positive cells increased significantly in Dag1 cKO brains between E14.5 and E18.5, especially from E14.5 to E15.5 (Figs. 4I, K, M; 5B, D, F). Tbr1-positive cells and CTIP2-positive cells, with birth dates between E11.5 and E15.5 (55), were born both prior to and following significant disruption of the PBM in Dag1 cKO brains. Many E12.5 (Fig. 5G), and occasional E15.5 (Fig. 5H) BrdU-labeled Tbr1-positive cells were present in the heterotopia of P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains, suggesting that projection neurons born before and after PBM breakdown migrated into meningeal heterotopia.

Figure 5.

Marked dyslamination and expansion of heterotopia (HT) during late neurogenesis are associated with overmigration of deep and superficial cortical plate (CP) neurons. (A-H) The Tbr1-positive CP layer VI in Dag1+/+ brains progressively expands between E14.5 (A), E15.5 (C), and E18.5 (E). In addition to CP layer VI, small numbers of heterotopic Tbr1-positive neurons are present in Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) (Dag1−/−) E14.5 brains (B, arrows). Many more heterotopic Tbr1-positive neurons are present at E15.5 (D) compared to E14.5 (B) and the thickness of Tbr1-positive cells in layer VI (D) appears much reduced at E15.5 in Dag1 cKO brains compared to wild type (WT) Dag1+/+ brains (C). Despite substantial expansion of meningeal HT, few additional heterotopic Tbr1-positive neurons are present in Dag1 cKO E18.5 brains (F) compared to E15.5 brains (D), and many areas in layer VI still have large numbers of appropriately-laminated Tbr1-positive cells at E18.5 (F, arrow). (I-N) Many early-born Tbr1-positive/BrdU-positive (E12.5) neurons (arrow) are present in Dag1 cKO P0.5 HT despite birth dates several days prior to BM disruption (G, HT). Although occasional late-born Tbr1-positive/BrdU-positive (E15.5) neurons (arrow) are present in Dag1 cKO P0.5 HT, many late-born Tbr1-positive neurons are appropriately laminated in CP layer VI despite BM disruption prior to their birth and migration (H, layer VI). (I-N) Many late-born Cux1-positive neurons are present in layers II-IV in Dag1+/+ brains at E15.5 (I), E16.5 (K) and P0.5 (M). Small numbers of heterotopic Cux1-positive neurons are present in Dag1 cKO E15.5 brains (J, arrows) whereas slightly more and substantially more are present at E16.5 (L) and P0.5 (N), respectively. Despite widespread BM disruption prior to their birth and migration through the CP, many Cux1-positive neurons are appropriately laminated in layers II-IV at P0.5 (N). (O, P) Er81-positive neurons are restricted to the deep aspect of layer V in P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains (O) but are present in layers I-V and heterotopia (arrow) in Dag1 cKO brains (P). (Q, R) Rorβ-positive neurons are only present in layer IV in P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains (Q) but are distributed throughout layers I-IV (arrow) in Dag1 cKO brains (R). (S, T) CTIP2-positive neurons are mostly limited to layer V and are superficial to earlier-born Tbr1-positive neurons in layer VI in P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains (S) but Tbr1-positive neurons are also admixed with CTIP2-positive neurons in layers I-V and heterotopia in Dag1 cKO brains (T). (U, V) Cux1-positive neurons in layers II-IV are superficial to earlier-born CTIP2-positive neurons in layer V in Dag1+/+ brains (U) but are also admixed with Cux1-positive cells in layers I-IV and HT in Dag1 cKO brains (V). IZ, intermediate zone; SVZ, subventricular zone. Scale bars: A-F, 200 µm; I-N, 100 µm; G, H, O–V, 50 µm.

Most superficial layer neurons, including layer II-IV cells, had birth dates between E13.5 and E16.5 (55), and, therefore, were born and migrated into the CP after significant disruption of the PBM had occurred in Dag1 cKO brains. In E15.5, E16.5, and P0.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains, cells expressing the transcription factor Cux1 were present in layers II-IV (Fig. 5I-N). Cux1-positive cells also accumulated in meningeal heterotopia of Dag1 cKO brains, particularly between E16.5 and P0.5, despite reduced heterotopic migration of early-born neurons (CTIP2-positive and Tbr1-positive) during this time period (Fig. 5J, L, N).

Individual CP layers contain multiple subtypes of projection neurons, and at the same time, specific projection neuron subtypes may normally be present in single or multiple CP layers (55). For example, Er81-positive cells include all layer V subcerebral and many layer V corticocortical projection neurons, whereas CTIP2-positive expression is limited to layer V subcerebral projection neurons (56,57). Also, Rorβ expression is restricted to layer IV neurons, whereas Cux1 is expressed by neurons in layers II-IV (58, 59). We investigated dyslamination of different neuronal subtypes in Dag1 cKO brains that normally have similar or overlapping laminar fates but unique molecular expression patterns. We compared the distribution of neurons defined by either Er81-positive or Rorβ-positive expression to that of CTIP2-positive and Cux1-positive neurons, respectively. In P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains, Er81-positive neurons were in the deep (apical) aspect of layer V (Fig. 5O) but in Dag1 cKO brains, few Er81-positive neurons laminated appropriately in layer V and most were in layers I-IV and heterotopia (Fig. 5P). Interestingly, fewer Er81-positive neurons laminated appropriately in Dag1 cKO brains compared to another layer V neuronal subtype, CTIP2-positive cells (Fig. 4M). All Rorβ-positive neurons in P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains were in layer IV (Fig. 5Q). Although most Rorβ-positive neurons laminated appropriately in layer IV of P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains, they were also frequently present in layers I-III (Fig. 5R) and heterotopia (data not shown) in a comparable pattern to Cux1-positive cells, which are likewise late-born neurons.

In normal CP development, deeper layers form before and beneath more superficial layers in an inside-out pattern based on birth date and molecular phenotype (55, 60, 61). In P0.5 Dag1+/+ brains, CTIP2-positive cells in layer V were above Tbr1-positive cells in layer VI with little overlap (Fig. 5S). In contrast, Tbr1-positive cells were mixed with CTIP2-positive cells in layer V, and both Tbr1-positive and CTIP2-positive cells were present in more superficial CP layers as well as meningeal heterotopia in P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 5T). Similarly, Cux1-positive cells in layers II-IV were above layer V CTIP2-positive cells in Dag1+/+ brains (Fig. 5U), but both were admixed in superficial CP layers and meningeal heterotopia without respect to normal laminar pattern in P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 5V). Nevertheless, despite the large number of neurons from each of the CP layers that aberrantly migrated in.5 Dag1 cKO brains, there was a surprising degree of appropriate lamination within the mutant CP, and only rarely were CP projection neurons present in deeper than normal laminae of the cortex for their specific molecular expression phenotype (Figs. 5B, D, F, J, L, N, P, R, T, V). In this regard, neuronal “overmigration” accurately depicts this aspect of the Dag1 cKO cortical phenotype.

Unlike projection neurons, interneurons are produced in the ventral telencephalon and migrate tangentially into the dorsal telencephalon through the MZ, IZ, and SVZ before migrating radially to establish laminar positions alongside projection neurons of similar birth dates (62–67). Dlx transcription factors are specifically expressed by cortical interneurons during the embryonic and postnatal periods (63). In E15.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO cortex, Dlx-positive interneurons similarly migrated in streams from the ventral telencephalon to the CP in tangential migratory streams from the ganglionic eminences (Fig. 6A, B). Within the dorsal cortex, most Dlx-positive interneurons were widely distributed among cortical layers, with greatest abundance in the IZ, SVZ, and (admixed with CR cells) in the MZ. In Dag1 cKO cortex, some Dlx-positive cells also migrated into meningeal heterotopia (Fig. 6C, D). In E18.5 Dag1+/+ lateral neocortex, many Dlx-positive interneurons were still migrating to dorsal telencephalon through the MZ, IZ, and SVZ, and some interneurons accumulated in layer V (Fig. 6E). In contrast, many Dlx-positive interneurons in E18.5 Dag1 cKO lateral cortex were located not only in these zones, but also in heterotopia overlying gaps in the MZ monolayer of reelin-positive CR cells (Fig. 6F). Compared to E15.5 brains, many more Dlx-positive interneurons had migrated into the dorsal cortex and were in layers I, V, VI, VZ and SVZ in both Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 6G,H). Dlx-positive interneurons were also in the heterotopia of P0.5 Dag1 cKO brains (Fig. 6H). Accumulation of Dlx-positive interneurons within meningeal heterotopia throughout the neurogenic period is consistent with the hypothesis that interneurons migrate to similar locations during the same period of time as projection neurons with the same birth dates and therefore are similarly susceptible to conditions that facilitate overmigration (67).

Figure 6.

Interneurons migrate into meningeal heterotopia (HT). (A, B) In Dag1+/+ wild type (WT) and Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) (Dag1−/−) E15.5 brains, Dlx-positive interneurons migrate similarly from the ventral telencephalon to the cortical plate in tangential migratory streams (arrows) from the ganglionic eminences (GE). (C, D) Within the dorsal cortex, most Dlx-positive interneurons are in the marginal zone (MZ), intermediate zone (IZ), and subventricular zone (SVZ) but are also present in heterotopia (HT) of Dag1 cKO brains (D). (E, F) In Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO E18.5 brains, interneurons are tangentially migrating through lateral cortices in the IZ, SVZ, layer V, and the MZ (containing reelin-positive CR cells). In Dag1 cKO brains but not Dag1+/+ brains, many interneurons in the lateral cortex are in HT (arrows) overlying gaps in the reelin-positive CR cell monolayer (arrowheads) in the MZ (F). (G, H) By P0.5, many more interneurons are in the dorsal cortex compared to E15.5 in both Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains. Most interneurons are in layer V, layer VI, the ventricular zone (VZ), SVZ, and mixed with CR cells in layer I (G, H); however, large numbers of interneurons are also in HT of Dag1 cKO brains (G). St, striatum. Scale bars: A, B, E, F, 100 µm; C, D, G, H, 50 µm.

Heterotopic Pyramidal Neurons Establish Appropriate Axonal Projections

We used retrograde axon tracing with DiI to investigate cortical pyramidal neuron morphology and efferent axonal projections. As expected, DiI injections into the thalamic ventroposterior lateral nucleus (VPLN) resulted in retrograde labeling of corticothalamic neurons with somata in layer VI of the somatosensory cortex in both Dag1 +/+ and Dag1 cKO P7.5 brains (Fig. 7A, B); however, ectopic neurons in superficial CP layers and meningeal heterotopia of Dag1 cKO brains also established connections with the VPLN (Fig. 7B). DiI injections into the corpus callosum labeled neurons in all layers of P7.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains, with the greatest abundance of callosal neurons in upper layers II-IV (Fig. 7C, D). Many neurons in Dag1 cKO meningeal heterotopia also made callosal projections (Fig. 7D). DiI injections into the cerebral peduncles of P7.5 Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains retrogradely labeled neurons in layer V, but in addition, many neurons in Dag1 cKO heterotopia were labeled from these injections (Fig. 7E-I). In P7.5 Dag1+/+ brains, pyramidal neurons had parallel arrangement of apical dendrites that terminated with tufts in layer I (Fig. 7A, E, G). The dendrites of heterotopic subcerebral projection neurons in P7.5 Dag1 cKO brains were frequently oriented abnormally, with tortuous apical dendrites. In some cases, apical dendrites ran parallel to the surface of the heterotopia (Fig. 7H), or projected downward (towards the ventricle) and therefore opposite to the normal orientation of apical dendrites (Fig. 7I).

Figure 7.

Ectopic pyramidal neurons project to appropriate cortical and subcortical targets but have abnormal dendritic orientation. (A, B) In the somatosensory cortex of wild type (WT) Dag1+/+ and Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) (Dag1−/−) brains, layer VI neurons with thalamic projections are retrogradely-labeled by DiI injections in the thalamic ventroposterior lateral nucleus (VPLN); however, ectopic layer VI neurons in superficial CP layers and heterotopic layer VI neurons (B, arrow) in Dag1 cKO brains also established thalamic connections despite severe dyslamination. (C, D) In Dag1+/+ and Dag1 cKO brains, neurons in all cortical plate (CP) layers with commissural projections are retrogradely labeled by DiI injections in the corpus callosum. In Dag1 cKO brains, many heterotopic neurons (D, arrow) also have commissural projections and are retrogradely labeled by DiI injections in the corpus callosum. (E, F) In Dag1+/+ brains and Dag1 cKO brains, layer V neurons with subcerebral projections (to the brainstem and spinal cord) are retrogradely labeled by DiI injections in the cerebral peduncles. Many ectopic layer V neurons in superficial CP layers and heterotopia (HT) (F, arrow) also have subcerebral projections. (G-I) layer V pyramidal neurons in Dag1+/+ brains have parallel, radially oriented apical dendrites ending in tufts in layer I (G). Heterotopic neurons in Dag1 cKO brains often have abnormally-oriented and tortuous apical dendrites, which occasionally are bent against the outer edge of the HT (H), or are inverted (I). Scale bars: A–F, 200 µm; G, I, 100 µm.

DISCUSSION

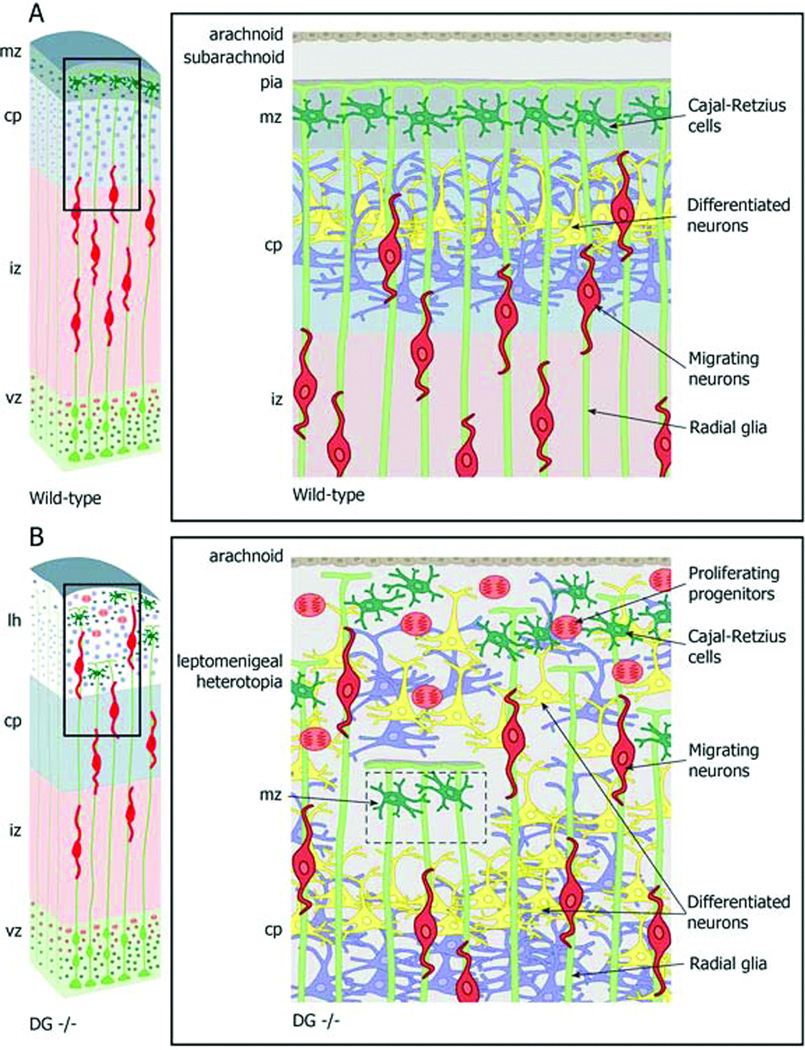

The complex process of neocortical development involves proliferation of progenitor cells in the dorsal and ventral telencephalon, long-distance migration of post-mitotic neurons from progenitor zones into the CP, lamination of neurons according to birth date and molecular phenotype, and establishment of connections with cortical and subcortical targets (54, 60, 62, 68–70). Because PBM-RG signaling interactions are mediated by DG and have been shown to be essential for normal morphogenesis of the cerebral cortex, we investigated the expression of DG protein and Dag1 mRNA in the developing neocortex. We used Dag1 conditional knockout brains to investigate which aspects of normal neocortical development are affected by disrupted PBM-RG interactions and the pathogenesis of cobblestone lissencephaly. We found that the disruption of PBM-RG interactions due to Dag1 mutation caused perturbations that altered the distribution and migration of progenitors and neurons, but had little effect on the layer-specific (molecular) differentiation of pyramidal and nonpyramidal neuron types, or on axon growth and targeting to thalamus, contralateral cortex, and cerebral peduncles. Our data provide a more complete understanding of the pathogenesis underlying cobblestone lissencephaly in some of the dystroglycanopathies. Key features of this developmental pathology are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Summary of abnormal neurogenesis in Dag1 conditional knockout (cKO) model of dystroglycanopathy. (A) In wild type (WT) brains (A), neurons generated in the ventricular zone (vz) and subventricular zone (svz) by radial glia and intermediate progenitor cells migrate through the intermediate zone (IZ) into the cortical plate (CP) along the basal processes of radial glia. Radial glia basal processes terminate as foot processes on the pial basement membrane (PBM). Differentiated neurons form an inside-out laminar pattern in the cortical plate below reelin-producing Cajal-Retzius cells in the marginal zone (MZ) and the PBM. (B) In dystroglycan (DG) null brains, neurons generated in the VZ and SVZ migrate through the IZ into the CP and into the leptomeninges through discontinuities in the PBM. Proliferating heterotopic progenitor cells produce autochthonous heterotopic neurons. Radial glia basal processes extend into the leptomeninges through discontinuities in the PBM. There is profound cortical disorganization and formation of leptomeningeal heterotopia (lh) containing migrating neurons, differentiated neurons, Cajal Retzius cells, and proliferating progenitor cells. Residual intact PBM overlies small areas of normal CP.

Consistent with previous findings in all cell types where dystroglycan is expressed as a major extracellular matrix receptor and is localized along the membrane where it contacts the basement membrane, Dag1 mRNA expression colocalized with RG soma in the VZ during the neurogenic period whereas DG protein was limited to RG basal process endfeet where they interact with the PBM and establish the glia limitans. RG are the only cell type that directly interface with the PBM during development and the localization of DG in RG end feet during neocortical histogenesis provides a basis for understanding the pathogenesis of neuronal migration disorders when DG absence results in the loss of necessary RG-PBM interactions. Absence of α- and β-DG from RG basal processes in Dag1 cKO brains resulted in disarrayed and truncated RG fibers with subsequent loss of PBM throughout embryonic development. RG basal processes normally provide a scaffold for some radially migrating projection neurons and interneurons (40, 71,72), and the PBM normally compartmentalizes cortical neurons within the neocortical epithelium. Disarrayed RG fibers, breaches in the PBM, and RG fibers that extended into the meninges apparently facilitated overmigration of diverse cellular elements, including progenitor cells, CR cells, projection neurons, and interneurons, beyond the glia limitans and into meningeal spaces. Although the relative contribution of each remains unclear, progressive PBM disintegration, neuronal overmigration, and aberrant repair of the cortical surface throughout the embryonic period resulted in severe dyslamination and leptomeningeal heterotopia that were confluent with underlying residual cortices.

CR cells migrated into the meninges soon after the PBM began to break down, leaving widespread gaps in the CR cell layer within the MZ. Reelin, which is produced by CR cells in the MZ, is an important positioning cue for radially migrating neurons and is necessary for establishment of the normal “inside-out” laminar pattern of the cortical plate (73). Overmigration of cortical plate neurons into the meninges may have been further facilitated by ectopic reelin within the developing meningeal heterotopia or by reduced reelin levels within the MZ, although it is unclear whether reelin acts as a “stop signal” during migration. Despite CR cells occasionally being distributed along the basal aspect of heterotopia, CP neurons rarely formed a laminar pattern in heterotopia. Instead, neurons with molecular phenotypes of different CP layers were typically admixed in heterotopia with no discernible pattern.

Neurons from all cortical plate layers migrated into inappropriately-superficial cortical plate layers and into the meninges of Dag1 cKO brains. Although not investigated in this study, the Dag1 cKO brain could be used in future studies to examine the molecular mechanistic basis for neuronal overmigration following PBM disruption. Early-born neurons migrated into heterotopia soon after PBM discontinuities developed. However, by late embryogenesis, most heterotopic neurons expressed molecular phenotypes of late-born neurons destined for superficial CP layers. There was significant retention of normal CP lamination with early-born neurons even after widespread PBM disintegration was present in Dag1 cKO brains. It is likely that cortical neurons have a window of opportunity for aberrant migration, if permissive conditions such as loss of PBM integrity exist, before becoming permanently settled in their laminar position. The time points when PBM disruptions first develop and the rate at which they progress in cobblestone lissencephaly likely impact the total number of neurons that migrate abnormally. Earlier or more rapid disintegration of the PBM may result in more extensive CP laminar disorganization and heterotopia formation because greater numbers of neurons may not yet have become fixed in their CP laminar position. A comparison of Gfap-Cre and Nestin-Cre Dag1 cKO mice supports this hypothesis, i.e. Gfap-Cre cKO mice lose DG approximately 2 to 3 days later than Nestin-Cre cKO mice and have less extensive cortical heterotopia. (74).

The clinical severity of neurological deficits among humans with cobblestone lissencephaly varies widely; and this clinical heterogeneity appears to be associated at least in part with different known or unknown genetic mutations that result in hypoglycosylation of DG (75). Although not established in this study, we hypothesize that clinical phenotypic variability might be associated with mechanistic differences in DG hypoglycosylation that affect the rate and timing of PBM disruption and, therefore, the extent of cortical dysgenesis in cobblestone lissencephaly. This hypothesis could be further explored with comparative studies of mouse models of DG hypoglycosylation. Molecular and neuropathological findings from a recent study of 65 fetal human cases provide support for this hypothesis (6). Interestingly, despite widespread disruption of the PBM, disarray of RG basal processes, and loss of many CR cells from the MZ of Dag1 cKO brains by E16.5, many upper layer neurons successfully laminated in the cortical plate after this time point. This suggests that factors other than PBM integrity, an orderly radial glial migratory scaffold, and normal spatial gradients of MZ reelin may contribute to appropriate lamination of some projection neurons.

Cortical projection neurons establish commissural and corticofugal connections with specific targets based on their molecular identity, which is normally highly correlated with laminar position (70). The development of appropriate cortical connections involves axon pathfinding mediated by extrinsic molecular signals in addition to reciprocal interactions with cortical afferent axons (70). Within the heterotopia of Dag1 cKO brains, some pyramidal neurons showed altered polarity including abnormally oriented or bent apical dendrites, closely resembling the morphology of neocortical neurons in humans with Walker-Warburg syndrome and cobblestone lissencephaly (76). Despite severe dyslamination and abnormal dendrite orientation, heterotopic pyramidal neurons established axonal connections with distant cortical and subcortical targets or projections within appropriate white matter tracts. This is consistent with the view that axon pathfinding does not require laminar organization. Extrinsic axonal pathfinding cues and intrinsic signals in ectopic cortical projection neurons were apparently sufficient for proper cortical projections independent of final laminar or heterotopic position. The plasticity of the developing cerebral cortex, as demonstrated by successful axon guidance despite extensive cortical dyslamination and abnormal dendrites of individual ectopic projection neurons in Dag1 cKO brains, may also account in part for the high degree of retained neurological function in some humans with cobblestone lissencephaly (75).

PBM disintegration in Dag1 cKO brains resulted in formation of meningeal neuronal heterotopia containing proliferating progenitor cells. Thus, the dystroglycanopathies with brain malformations are not only neuronal migration disorders, but also progenitor migration disorders. Expression of the transcription factors Pax6 and Tbr2 is limited to radial glia and IPCs, the progenitors of glutamatergic neurons, in the dorsal telencephalon of normal mice. RG and IPCs are normally restricted to the VZ and SVZ, respectively, during neocortical histogenesis. Ectopic Pax6-positive and Tbr2-positive cells in Dag1 cKO brains were frequently immunoreactive for PCNA and PHH3 and incorporated BrdU, markers of proliferating cells, but were not immunoreactive for GFAP, a marker of astrocytic terminal differentiation. These ectopic Pax6-positive and Tbr2-positive cells were likely RG and IPCs that had lost both apical (ventricular) and basal (pial) attachments and migrated away from the VZ and SVZ. Remarkably, apical attachment and exposure to local extrinsic cues within the neurogenic niches of the VZ and SVZ were therefore not essential for ectopic RG and IPCs to maintain proliferative progenitor phenotypes; however, the mechanism by which these phenotypes persist under these conditions and whether they eventually differentiate into terminal phenotypes remains unclear.

Mitotically active ectopic progenitor cells in superficial CP layers and heterotopia of Dag1 cKO brains presumably produced ectopic glutamatergic neurons and thus contributed in part to dyslamination and expansion of heterotopic meningeal neuronal populations. Late in neurogenesis, most progenitor cells in normal murine neocortices are committed to produce upper layer neurons such as Cux1-positive cells (77). It is possible that ectopic progenitor cells in Dag1 cKO brains, which were first detected relatively late in neurogenesis, produced mostly ectopic projection neurons expressing molecular markers of upper cortical plate layers such as Cux1 due to their lineage restriction. This may partially contribute to the disparity in the number of early-born compared to late-born ectopic neurons that accumulated within meningeal heterotopia during late embryogenesis.

In summary, we verified that Dag1 mRNA is expressed by RG cells in the embryonic ventricular zone (VZ) while DG protein is localized to RG endfeet in contact with the PBM, indicating that DG protein must be transported along the RG fiber to achieve this localization. We also found that Dag1 inactivation led to disintegration of the PBM, RG fiber abnormalities, formation of heterotopia by aberrant migration of diverse cortical neuronal cell types into the meningeal space, and heterotopic proliferation of RG and IPC progenitor cells. Our findings demonstrate that DG expression on RG end feet is essential for multiple processes of neocortical histogenesis to occur normally. However, we also show that other developmental processes, such as establishment of appropriate axonal projections, can occur despite severe dyslamination and abnormal dendritic orientation. This study provides evidence that the pathogenesis of cobblestone malformation in dystroglycanopathy is associated with severe dyslamination of CP layers with aberrant migration of diverse cell types that are influenced by the timing and extent of PBM disruptions. It also demonstrates that cortical dysgenesis involves not only overmigration of neurons, but also disturbances of RG morphology, progenitor distribution, and pyramidal neuron orientation.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH 5 T32 RR07019 (T.D.M.), NIH R01 NS050248-04 (R.F.H.), NIH R21 NS041407 (S.A.M. and A.P.O.), and NIH U54 NS053672 (S.A.M., K.P.C. and A.P.O). K.P.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank the investigators and laboratories listed in the Materials and Methods section for providing antibodies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cormand B, Pihko H, Bayes M, et al. Clinical and genetic distinction between Walker-Warburg syndrome and muscle-eye-brain disease. Neurology. 2001;56:1059–1069. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haltia M, Leivo I, Somer H, et al. Muscle-eye-brain disease: a neuropathological study. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:173–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuyama Y, Osawa M, Suzuki H. Congenital progressive muscular dystrophy of the Fukuyama type-clinical, genetic, and pathological considerations. Brain Dev. 1981;3:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(81)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang T, Atefy R, Sheen V. Malformations of cortical development. Neurologist. 2008;14:181–191. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31816606b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golden JA. Cell migration and cerebral cortical development. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:22–28. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devisme L, Bouchet C, Gonzales M, et al. Cobblestone lissencephaly: neuropathological subtypes and correlations with genes of dystroglycanopathies. Brain. 2012;135:469–482. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Ball SL, Yang Y, et al. A genetic model for muscle-eye-brain disease in mice lacking protein O-mannose 1,2-N-acetylclucosaminyltransferase (POMGnT1) Mech Dev. 2006;123:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiyonobu T, Sasaki J, Nagai Y, et al. Effects of fukutin deficiency in the developing mouse brain. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu H, Yang Y, Eade A, et al. Breaches of the pial basement membrane and disappearance of the glia limitans during development underlie the cortical lamination defect in the mouse model of muscle-eye-brain disease. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:168–183. doi: 10.1002/cne.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobyns WB, Pagon RA, Armstrong D, et al. Diagnostic criteria for Walker-Warburg Syndrome. Am J Med Genetics. 1989;32:195–210. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320320213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santavuori P, Somer H, Sainio K, et al. Muscle-eye-brain disease (MEB) Brain Dev. 1989;11:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(89)80088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuyama Y, Osawa M, Suzuki H. Congenital progressive muscular dystrophy of the Fukuyama type – clinical, genetic, and pathological considerations. Brain Dev. 1981;3:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(81)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano I, Funahashi M, Takada K, et al. Are breaches in the glia limitans the primary cause of the micropolygyria in Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD)?-pathological study of the cerebral cortex of an FCMD fetus. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s004010050431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore SA, Saito F, Chen J, et al. Deletion of brain dystroglycan recapitulates aspects of congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2002;418:422–425. doi: 10.1038/nature00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michele DE, Barresi R, Kanagawa M, et al. Post-translational disruption of dystroglycan-ligand interactions in congenital muscular dystrophies. Nature. 2002;418:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nature00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim DS, Hayashi YK, Matsumoto H, et al. POMT1 mutation results in defective glycosylation and loss of laminin-binding activity in alpha-DG. Neurology. 2004;62:1009–1011. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115386.28769.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schachter H, Vajsar J, Zhang W. The role of defective glycosylation in congenital muscular dystrophy. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:291–300. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000033626.65127.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grewal PK, Hewitt JE. Glycosylation defects: a new mechanism for muscular dystrophy? Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(Rev Iss 2):R259–R264. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beltran-Valero de Bernabe D, Currier S Steinbrecher A, et al. Mutations in the O-mannosyltransferase gene POMT1 give rise to the severe neuronal migration disorder Walker-Warburg Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1033–1043. doi: 10.1086/342975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida A, Kobayashi K, Manya H, et al. Muscular dystrophy and neuronal migration disorder caused by mutations in a glycosyltransferase, POMGnT1. Dev Cell. 2001;1:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Reeuwijk J, Janssen M, van den Elzen C, et al. POMT2 mutations cause alpha-dystroglycan hypoglycosylation and Walker Warburg syndrome. J Med Genet. 2005;42:907–912. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.031963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry MD, Campbell KP. A role for dystroglycan in basement membrane assembly. Cell. 1998;95:859–870. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henry MD, Satz JS, Brakebusch C, et al. Distinct roles for dystroglycan, beta1 integrin and perlecan in cell surface laminin organization. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1137–1144. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halfter W, Dong S, Yip Y-P, et al. A critical function of the pial basement membrane in cortical histogenesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6029–6040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06029.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graus-Porta D, Blaess S, Senften M, et al. β1-class integrins regulate the development of laminae and folia in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Neuron. 2001;31:367–379. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beggs HE, Schahin-Reed D, Zang K, et al. FAK deficiency in cells contributing to the basal lamina results in cortical abnormalities resembling congenital muscular dystrophies. Neuron. 2003;40:501–514. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niewmierzycka A, Mills J, St-Arnaud R, et al. Integrin-linked kinase deletion from mouse cortex results in cortical lamination defects resembling cobblestone lissencephaly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7022–7031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1695-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georges-Labouesse E, Mark M, Messaddeq N, et al. Essential role of α6 integrins in cortical and retinal lamination. Curr Biol. 1998;8:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satz JS, Philp AR, Kusano H, et al. Visual impairment in the absence of dystroglycan. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13136–13146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0474-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson RA, Henry MD, Daniels KJ, et al. Dystroglycan is essential for early embryonic development: disruption of Reichert’s membrane in Dag1-null mice. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:831–841. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satz JS, Barresi R, Durbeej M, et al. Brain and eye malformations resembling Walker-Warburg syndrome are recapitulated in mice by dystroglycan deletion in the epiblast. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10567–10575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2457-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, et al. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duclos F, Straub V, Moore SA, et al. Progressive muscular dystrophy in alpha-sarcoglycan-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1461–1471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bulfone A, Martinez S, Marigo V, et al. Expression pattern of the Tbr2 (eomesodermin) gene during mouse and chick brain development. Mech Dev. 1999;84:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gotz M, Stoykova A, Gruss P. Pax6 controls radial glia differentiation in the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:1031–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Englund C, Fink A, Lau C, et al. Pax6, Tbr2, and Tbr1 are expressed sequentially by radial glia, intermediate progenitor cells, and postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:247–251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt KH, Crosbie RH, Venzke DP, et al. Biosynthesis of dystroglycan: processing of a precursor propeptide. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaccaria ML, Di Tommaso F, Brancaccio A, et al. Dystroglycan distribution in adult mouse brain: a light and electron microscopy study. Neurosci. 2001;104:311–324. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misson JP, Edwards MA, Yamamoto M, et al. Identification of radial glial cells within the developing murine central nervous system: studies based upon a new immunohistochemical marker. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1988;44:95–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:61–83. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kriegstein AR, Noctor SC. Patterns of neuronal migration in the embryonic cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muzumdar D, Michaud J, Ventureya EC. Anterior cranial base glioneuronal heterotopia. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00381-005-1222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Intracranial extracerebral glioneuronal heterotopia. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosci. 2005;102:105–112. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.102.1.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kershisnik MM, Kaplan C, Craven CM, et al. Intrapulmonary neuroglial heterotopia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:1043–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juric-Sekhar G, Kapur RP, Glass IA, et al. Neuronal migration disorders in microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type I/III. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eriksson SH, Thom M, Heffernan J, et al. Persistent reelin-expressing Cajal-Retzius cells in polymicrogyria. Brain. 2001;124:1350–1361. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.7.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komatsu S, Sakata-Haga H, Sawada K, et al. Prenatal exposure to ethanol induces leptomeningeal heterotopia in the cerebral cortex of the rat fetus. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:22–26. doi: 10.1007/s004010000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, et al. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKeever PE. Insights about brain tumors gained through immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization of nuclear and phenotypic markers. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:585–594. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hevner RF. Layer-specific markers as probes for neuron type identity in human neocortex and malformations of cortical development. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:101–109. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180301c06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D’Arcangelo G, Nakajima K, Miyata T, et al. Reelin is a secreted glycoprotein recognized by the CR-50 monoclonal antibody. J Neurosci. 1997;17:23–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00023.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammond V, Howell B, Godinho L, et al. Disabled-1 functions cell autonomously during radial migration and cortical layering of pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8798–8808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08798.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arlotta P, Molyneaux BJ, Chen J, et al. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hevner RF, Shi L, Justice N, et al. Tbr1 regulates differentiation of the preplate and layer 6. Neuron. 2001;29:353–366. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hevner RF, Daza RAM, Rubenstein JLR, et al. Beyond laminar fate: toward a molecular classification of cortical projection/pyramidal neurons. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:139–151. doi: 10.1159/000072263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molnar Z, Cheung AFP. Towards the classification of subpopulations of layer V pyramidal projection neurons. Neurosci Res. 2006;55:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoneshima H, Yamasaki S, Voelker CCJ, et al. ER81 is expressed in a subpopulation of layer 5 neurons in rodent and primate neocortices. Neurosci. 2006;137:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaeren-Wiemers N, Andre E, Kapfhammer JP, et al. The expression pattern of the orphan nuclear receptor Rorβ in the developing and adult rat nervous system suggests a role in the processing of sensory information and in circadian rhythm. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:2687–2701. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nieto M, Monuki ES, Tang H, et al. Expression of Cux-1 and Cux-2 in the subventricular zone and upper layers II-IV of the cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:168–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Angevine JB, Sidman RL. Autoradiographic study of cell migration during histogenesis of cerebral cortex in the mouse. Nature. 1961;192:766–768. doi: 10.1038/192766b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rakic P. Neurons in rhesus monkey visual cortex: systematic relation between time of origin and eventual disposition. Science. 1974;183:425–427. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4123.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pleasure SJ, Anderson S, Hevner R, et al. Cell migration from the ganglionic eminences is required for the development of hippocampal GABAergic interneurons. Neuron. 2000;28:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, et al. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ang ESBC, Jr, Haydar TF, Gluncic V, et al. Four-dimensional migratory coordinates of GABAergic interneurons in the developing mouse cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5805–5815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05805.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fairen A, Cobas A, Fonseca M. Times of generation of glutamic acid decarboxylase immunoreactive neurons in mouse somatosensory cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1986;251:67–83. doi: 10.1002/cne.902510105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peduzzi JD. Genesis of GABA-immunoreactive neurons in the ferret visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1988;8:920–931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-00920.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hevner RF, Daza RAM, Englund C, et al. Postnatal shifts of interneuron position in the neocortex of normal and reeler mice: evidence for inward radial migration. Neurosci. 2004;124:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gotz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pilz D, Stoodley N, Golden JA. Neuronal migration, cerebral cortical development, and cerebral cortical anomalies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1–11. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Price DJ, Kennedy H, Dehay C, et al. The development of cortical connections. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:910–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Misson JP, Austin CP, Takahashi T, et al. The alignment of migrating neural cells in relation to the murine neopallial radial glial fiber system. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:221–229. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poluch S, Juliano SL. A normal radial glial scaffold is necessary for migration of interneurons during neocortical development. Glia. 2007;55:822–830. doi: 10.1002/glia.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, et al. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Satz JS, Ostendorf AP, Hou S, et al. Distinct functions of glial and neuronal dystroglycan in the developing and adult mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14560–14572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3247-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Godfrey C, Clement E, Mein R, et al. Refining genotype-phenotype correlations in muscular dystrophies with defective glycosylation of dystroglycan. Brain. 2007;130:2725–2735. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Judas M, Sedmak G, Rados M, et al. POMT1-Associated Walker-Warburg syndrome: A disorder of dendritic development of neocortical neurons. Neuropediatrics. 2009;40:6–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frantz GD, McConnell SK. Restriction of late cerebral cortical progenitors to an upper-layer fate. Neuron. 1996;17:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]