Abstract

Many Studies suggest that changes in sympathetic nerve activity in the central nervous system might have a crucial role in blood pressure control. The present paper discusses evidence in support of the concept that the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) might be linked to sympathetic nerve activity in hypertension. The amount of neurotransmitter release from sympathetic nerve endings can be regulated by presynaptic receptors located on nerve terminals. It has been proposed that alterations in sympathetic nervous activity in the central nervous system of hypertension might be partially due to abnormalities in presynaptic modulation of neurotransmitter release. Recent evidence indicates that all components of the RAS have been identified in the brain. It has been proposed that the brain RAS may actively participate in the modulation of neurotransmitter release and influence the central sympathetic outflow to the periphery. This paper summarizes the results of studies to evaluate the possible relationship between the brain RAS and sympathetic neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system of hypertension.

1. Introduction

There is increasing evidence to suggest that sympathetic nervous activity in both central and peripheral nervous systems may play a major role in the regulation of blood pressure, and that hypertension is accompanied characteristically by increased sympathetic nervous activity in both humans and animal models [1, 2]. Pharmacologic studies have demonstrated that depletion of central and peripheral catecholamine stores could prevent or attenuate the development of hypertension [3, 4]. The concept on the release of sympathetic neurotransmitters from nerve endings has been considerably refined by the demonstration of multiple presynaptic receptors, which were shown to either facilitate or inhibit their release [5, 6]. The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) including angiotensin receptors is widely distributed in the brain [7–9]. It is proposed that the RAS facilitates the sympathetic nervous system and that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition and angiotensin receptor blockade are antiadrenergic [10, 11]. However, the interaction between the brain RAS and sympathetic nervous system are not fully understood. In the present paper, we discuss the relationship between the brain RAS and sympathetic neurotransmitter release and further evaluate the role of RAS in the regulation of sympathetic nerve activity in the central nervous system of hypertension.

2. Amount of Norepinephrine Release in the Central Nervous System of Hypertension

Augmented norepinephrine (NE) release and catecholamine synthesis as well as tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression have been reported at central sites related to blood pressure regulation in adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [12, 13]. In a study presented earlier, Qualy and Westfall [14] observed that stimulation-evoked NE release from paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus in hypertensive rats was significantly increased in comparison with normotensive rats. We have been demonstrating that the stimulation-evoked NE release from hypothalamic slices was significantly greater in SHR than in normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats, suggesting that the release of NE from the hypothalamus may contribute to the elevated sympathetic nerve activity in hypertension [15–22]. It was also demonstrated that, by using electrophysiological method, higher discharge rates were detected in neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of neonatal SHR [23]. On the other hand, the stimulation-evoked NE release in the slices of whole medulla oblongata was not significantly different between SHR and WKY rats [24–29]. Recently, Teschemacher et al. [30] demonstrated that although overall electrophysiological characteristics of C1 and A2 catecholaminergic neurons in the brain were compatible between SHR and WKY rats, the angiotensin II- (Ang II-) induced Ca2+-mobilization was reduced in A2 neurons of SHR. Because A2 neurons are a part of an antihypertensive circuit, the reduced sensitivity of the A2 cells to Ang II might further compromise their homeostatic role in SHR. There might be regional differences in the amount of NE release in the central nervous system of hypertensive models.

In human hypertensive subjects, Esler et al. [31] studied the brain NE release and its relation to peripheral sympathetic nervous activity by using transmitter washout method. They showed that overall NE overflow into the internal jugular vein was significantly increased in subjects with essential hypertension compared with normotensive subjects. The finding indicated that central sympathetic tone might be activated in essential hypertension, although precise mechanisms regulating central sympathetic neurotransmitter release in human hypertension is not fully understood.

3. Role of Renin-Angiotensin System in the Regulation of Norepinephrine Release in the Central Nervous System

3.1. Angiotensin II

It was shown that angiotensin I (Ang I) and Ang II injected to the central nervous system significantly elevated blood pressure [32]. Davern and Head [33] showed that the chronic subcutaneous infusion of Ang II caused rapid and marked neuronal activation in circumventricular organs, such as subfornical organ, the nucleus of the solitary tract, paraventricular nucleus, and supraoptic nucleus. In an in vitro study presented earlier, Garcia-Sevilla et al. [34] demonstrated that Ang II facilitated in a concentration-dependent manner the potassium-evoked NE release in the rabbit hypothalamus, which was antagonized by saralasin. The result indicated that the increase in NE release might be mediated through presynaptic angiotensin facilitatory receptors on noradrenergic nerve terminals. It was also shown that Ang II increased the potassium-evoked NE release from slices of rat parietal cortex, and that the effect was blocked by saralasin, but not by the Ca channel blocker, nimodipine [35]. Moreover, the facilitative action of Ang II on NE release might be pronounced in the hypothalamus of SHR compared with normotensive rats [36]. In a microdialysis study, Qadri et al. [37] showed that intracerebroventricular administration of 100 ng of Ang II increased blood pressure and NE release in anterior hypothalamus of conscious rats, which was antagonized by the Ang II receptor blocker. By using the similar method, Stadler et al. [38] also reported that Ang II led to significant dose-dependent increases of NE release in the paraventricular nucleus.

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that function and signaling of the angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors are quite different from the angiotensin type 2 (AT2) sites and that these receptors may exert opposite effects on blood pressure regulation [39]. Gelband et al. [40] demonstrated that neuronal AT1 receptors might have a pivotal role in NE neuromodulation, and that evoked NE neuromodulation might involve AT1 receptor-mediated, losartan-dependent, rapid NE release, inhibition of potassium-channels and stimulation of Ca2+-channels. Furthermore, they proposed that AT1 receptor-mediated enhanced neuromodulation might involve the Ras-Raf-MAP kinase cascade and lead to an increase in NE transporter, tyrosine hydroxylase, and dopamine β-hydroxylase mRNA transcription. On the other hand, neuronal AT2 receptors might signal via a Gi-protein and be coupled to activation of PP2A and PLA2, and stimulation of potassium-channels. Nap et al. [41] showed that prejunctional AT1 receptors might belong to the AT1B receptor subtype because AT1B receptor inhibition by high concentrations of PD 123319 could suppress the Ang II-augmented noradrenergic transmission. Gironacci et al. [36] demonstrated that Ang-(1-7), which is synthesized by angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), significantly decreased the potassium-induced NE release in the hypothalamus of SHR by stimulating the AT2 receptors. In addition, they showed that the inhibitory effect of Ang-(1-7) on NE release was blocked by the nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor and the bradykinin (BK) B2 receptor antagonist. The finding indicated that Ang-(1-7) reduced NE release from the hypothalamus of SHR via the AT2 receptors, acting through a BK/NO-mediated mechanism. Recent findings have also revealed that the Mas oncogene may act as a receptor for Ang-(1-7) [42–44]. It is strongly suggested that activation of the ACE2-Ang-(1-7)-Mas axis might act as a counterregulatory system against the ACE-Ang II-AT1 receptor axis [42–44].

Bourassa et al. [45] demonstrated that AT1 receptor binding in both RVLM and caudal ventrolateral medulla as well as dorsomedial medulla was increased in SHR compared with normotensive rats. Conversely, expression of the novel, non-AT1, non-AT2, Ang II and III binding site, which was recently discovered, might be decreased in the RVLM and dorsomedial medulla of SHR [45]. They proposed that increased AT1 receptor binding in the RVLM might contribute to the hypertension of SHR, whereas reduced radioligand binding to the novel, non-AT1, non-AT2, angiotensin binding site in the RVLM of SHR might indicate a role for this binding site to reduce blood pressure via its interactions with Ang II and III.

In this context, the facilitative effect of Ang II on NE release might be an important factor in the excitation of sympathetic tone in the central nervous system, although further studies should be performed to assess more thoroughly the precise roles of the different types of Ang II receptors in the regulation of central sympathetic nerve activity in hypertension.

3.2. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

All components of the RAS have been identified in the brain, and the brain RAS might actively participate not only in blood pressure elevation, but also in target organ damages [7–9, 46]. It is proposed that the inhibition of brain ACE activity may be associated with blood pressure reduction induced by ACE inhibitors (ACEIs). Captopril, a widely accepted ACEI, may block the conversion of Ang I to Ang II and has been used as an effective antihypertensive agent in both human and experimental hypertension [47, 48]. Several studies have provided evidence that the distribution of the target sites for ACEIs might be widespread [49, 50]. It was demonstrated that captopril administered centrally significantly lowered blood pressure in intact conscious SHR [51]. Intracerebroventricular administration of captopril significantly suppressed the pressor responses to Ang I given by the same route in SHR [52]. Baum et al. [53] also observed the attenuation of pressor responses to intracerebroventricular Ang I by ACEI in conscious rats. It was shown that oral administration of captopril caused the inhibition of brain ACE activities [50, 54, 55]. It was demonstrated that the ACE activities in various tissues 1 hour after oral administration of several ACEIs and that captopril significantly reduced the ACE activities in aorta, heart, kidney, lung, and brain. Berecek et al. [56] showed that chronic intracerebroventricular injection of captopril attenuated the development of hypertension in young SHR in association with a depression in whole animal reactivity to vasoactive agents and an increased baroreflex sensitivity. It was also observed that central administration of captopril produced a significant depression in vascular reactivity to vasoconstrictor agents in the isolated perfused kidney of SHR in vivo [57]. The findings propose the hypothesis that central action of captopril might be, at least in part, related to vascular relaxation.

The different structures of ACEIs may influence their tissue distribution and routes of elimination. Cushman et al. [55] examined the effects of various ACEIs on brain ACE activity in SHR. They showed that not only captopril, but also zofenopril produced a modest, short-lasting inhibition of ACE activity in the SHR brain. On the other hand, fosinopril, lisinopril, and SQ 29,852 had delayed but long-lasting inhibitory actions, and ramipril and enalapril showed no effects. More studies are necessary to determine the distribution, binding activity to ACE, and metabolism of each ACEI in the brain.

In an in vitro study presented previously, we showed that captopril significantly inhibited the stimulation-evoked NE release in slices of rat hypothalamus and medulla oblongata [58], as well as in peripheral tissues, such as rat mesenteric arteries [59]. It might be possible that the inhibition of NE release by captopril might be partially due to a reduction in Ang II formation in the central nervous system. The modulation of central NE release by captopril might reduce the sympathetic outflow to the periphery, which could partially explain the hypotensive effects of the ACEI. Recently, Bolterman et al. [60] showed that captopril selectively lowered Ang II, oxidative stress, and endothelin in SHR. On the other hand, it was demonstrated that captopril had an asymmetrical effect on the angiotensinase activity in frontal cortex and plasma of SHR [61]. It might be possible that multiple neuroendocrine actions of ACEIs in the brain could, at least in part, contribute to their blood pressure-lowering efficacy in both human and experimental hypertension.

3.3. Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

It was shown that Ang II administered intracerebroventricularly at a dose that induces drinking behavior in rats significantly increased potassium-stimulated release of NE in the hypothalamus [62]. It can be suggested that Ang II is important primarily in pathological states and that NE plays a substantial role in the brain Ang II-induced drinking response. Furthermore, losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), significantly inhibited the potassium-stimulated NE release in the hypothalamus, acting via the AT1 receptor subtype [62]. Averill et al. [63] showed that losartan attenuated the pressor and sympathetic overactivity induced by Ang II and L-glutamate (an excitatory amino acid) in RVLM of SHR. Huang et al. [64] showed that central infusion of an AT1 receptor blocker prevented sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats on high salt diet.

Previous studies have reported only a limited ability of systemic ARB to cross the blood brain barrier [65–69]. Gohlke et al. [65] reported that orally applied AT1 receptor blocker candesartan suppressed the central responses of Ang II in a dose- and time-dependent manner in conscious rats, indicating that the AT1 receptor blocker might effectively inhibit the centrally mediated action of Ang II upon peripheral application. It was also shown that peripherally administered candesartan markedly decreased AT1 binding areas outside (subfornical organ and area postrema) and inside (paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and nucleus of the solitary tract) the blood-brain barrier [66, 67]. Unger [68] proposed that candesartan might be the most effective ARB in crossing the blood-brain barrier. On the other hand, Pelisch et al. [69] demonstrated that CV-11974, the active form of candesartan, was undetectable in brain tissue after oral candesartan treatment, suggesting that candesartan may not cross the intact blood-brain barrier in its active form, or may reach the brain at undetectable levels. They proposed the possibility that undetectable levels of ARB in the brain tissue would be enough to modulate the brain RAS. Further studies are required to determine the relationship between the molecular characteristics of ARBs and their properties to cross the blood-brain barrier [69].

In human hypertensive subjects, Esler [70] proposed that the ability of ARBs to antagonize neural presynaptic angiotensin AT1 receptors appears to differ markedly between the individual agents in this drug class. Recently, Krum et al. [71] examined whether ARBs inhibited central sympathetic outflow in human subjects. Using the whole body NE spillover method in humans with essential hypertension, they demonstrated that eprosartan and losartan did not materially inhibit central sympathetic outflow or act presynaptically to reduce NE release at existing rates of nerve firing. They concluded that sympathetic nervous inhibition might not be a major component of the blood pressure-lowering action of ARBs in subjects with essential hypertension.

On the other hand, de Champlain et al. [72] showed that the hypotensive action of valsartan may be mediated in part by an inhibition of the sympathetic baroreflex in patients with essential hypertension. It was also demonstrated that valsartan not only decreased blood pressure, but also shifted the baroreflex set point in hypertensive subjects [73]. Additional studies are necessary to determine the potential effects of ARBs on sympathetic nerve activity in the central nervous system of both human and experimental hypertension.

3.4. Direct Renin Inhibitors

Recent years have seen the development of the nonpeptide, orally long-term effective direct renin inhibitor (DRI), aliskiren, which may block the initial stages of the RAS and exert a sustained antihypertensive action in hypertensive subjects [74–76].

With regard to the influences of aliskiren on central sympathetic nervous system, Huang et al. [64] examined whether central infusion of aliskiren prevented sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats on high salt diet. Intracerebroventricular infusion of aliskiren markedly inhibited the increase in Ang II levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and in blood pressure caused by intracerebroventricular infusion of rat renin. In Dahl-salt sensitive rats, high salt intake increased resting blood pressure, enhanced pressor and sympathoexcitatory responses to air stress, and desensitized arterial baroreflex function. All of these effects were significantly prevented by intracerebroventricular infusion of aliskiren. These results indicated that intracerebroventricular infusions of aliskiren were effective in preventing salt-induced sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in Dahl-salt sensitive rats. Because the ARB also exerted similar effects [64], the result strongly confirms the idea that renin in the brain plays an important role in the salt-induced hypertension.

In a clinical study, it was shown that aliskiren significantly reduced sympathetic hyperactivity and blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [77]. However, Fogari et al. [78] reported that the increase in plasma NE evoked by Ca channel blocker, amlodipine, was not reduced by aliskiren addition in hypertensive subjects. It is strongly suggested that DRI might directly inhibit sympathetic neurotransmitter release, and that the hypotensive action of DRI might largely depend on its inhibitory effect on the sympathetic nerve activity in the central nervous system.

3.5. (Pro)renin Receptor

Recent evidence indicates that the (pro)renin receptor (PRR), which is a newly discovered member of the brain RAS, might contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension [79–82]. Li et al. [83] demonstrated that PRR protein was highly expressed in neurons and upregulated in the subfornical organ and the periventricular nucleus in Ang II-dependent hypertensive mice. In addition, they found that PRR knockdown in the brain significantly decreased blood pressure in renin-angiotensinogen transgenic hypertensive mice, which was associated with a decrease in sympathetic tone and improvement of spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity. Furthermore, PRR knockdown was associated with downregulation of the AT1 receptors. It is proposed that PRR blockade in the central nervous system might represent a novel approach for the treatment of neurogenic hypertension.

3.6. Mineralcorticoid Receptor

It has been shown that aldosterone as well as Ang II might act within the central nervous system and cause the sympathetic hyperactivity to increase blood pressure [84–87]. Huang et al. [84] proposed that brain aldosterone-mineralcorticoid receptor (MR)-ouabain pathway might have a pivotal role in Ang II-induced neuronal activation and pressor responses. The sympathoexcitatory effect of aldosterone was blocked by intracerebroventricular of MR antagonist [86]. It was also shown that central infusion of aldosteone synthase inhibitor prevented sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension by central sodium loading [88]. In a clinical study, Raheja et al. [89] showed that MR blockade by spironolactone prevented chlorthalidone-induced sympathetic activation in hypertensive subjects. Blockade of MR receptors and inhibition of aldosterone synthesis in the central nervous system might lead to a reduction in systemic blood pressure, although it remains unclear whether MR receptor blockers might exert greater antihypertensive effects than other RAS inhibitors.

3.7. Oxidative Stress

The involvement of oxidative stress is implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertension. It was demonstrated that superoxide anions in the RVLM, which might generate hydroxyl radicals, were increased in SHR-SP (stroke prone), suggesting that increased oxidative stress would lead to enhancing the central sympathetic outflow [90, 91]. Recent evidence indicates the possible link between Ang II and NADPH oxidase-derived oxidative stress in the central nervous system [92, 93]. Mertens et al. [93] proposed that AT1 receptors might activate the NADPH oxidase complex which could be the most important source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and suggested that the produced superoxide anion would be converted into H2O2 by superoxide dismutase or combine with NO to generate peroxynitrite, thereby decreasing NO-bioavailability and promoting lipid and protein oxidation. Additional studies are necessary in order to further unravel the implications of oxidative stress in the Ang II-induced neurotoxicity in the brain.

4. Renin Angiotensin System and Other Neurotransmitter Release in the Central Nervous System

4.1. Dopamine Release

There is increasing evidence to suggest that dopaminergic nerve activity in the central nervous system may play a crucial role in the regulation of blood pressure [94–102]. Recent evidence has suggested a functional interaction between brain angiotensin mechanisms and dopamine neurons, although the influences of the RAS on central dopaminergic activities in hypertension are controversial [94–102].

It has been demonstrated that ACE is localized throughout the brain and, importantly, is found in neurons of striatum and nigrostriatal tract [48]. In addition, there has been increasing evidence in favor of the involvement of nigrostriatal dopaminergic systems in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Linthorst et al. [95] reported that substantia nigra lesions caused a profound attenuation of the development of hypertension in SHR. Brown et al. [103] showed that the Ang II-induced dopamine release was completely blocked by the AT1 receptor antagonist, losartan, but not by the AT2 receptor antagonist, PD 123177, suggesting that Ang II acting via the AT1 receptor subtype might facilitate the release of dopamine, in the rat striatum. By using the microdialysis method, Mendelsohn et al. [104] showed that administration of Ang II into the rat striatum caused an increase in the release of dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), a dopamine metabolite, and proposed that dopamine release was under a tonic facilitative influence of Ang II.

On the other hand, it has been proposed that the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system may mediate baroreflex sensitivity in rats because both striatal dopamine release and baroreflex responses produced by phenylephrine and carotid occlusion were attenuated by lesions of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway [105]. It has also been reported that centrally administered Ang II increased exploratory behavior in rats and that this effect was antagonized by the dopamine receptor antagonist sulpiride. The finding indicated that Ang II potentiated central dopaminergic effects and dopamine-mediated behavioral responses [106]. Banks et al. [107] demonstrated that the ACE inhibitor captopril inhibited apomorphine-induced oral stereotypy in rats. The observation suggests that a decrease in Ang II formation caused by the ACE inhibitor could block nigrostriatal output. In an in vitro study, we examined the effects of captopril on the release of dopamine, and further determined a possible role of RAS in the regulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the central nervous system [108]. We showed that captopril inhibited the release of dopamine in the rat striatum in a dose-dependent manner [108]. Although the mechanisms underlying the neurosuppressive effects of captopril remain to be elucidated, the finding suggests that the inhibition of dopaminergic neurotransmission may be related to the central action of the ACEI.

Jenkins et al. [109] observed that AT1 receptors have been identified on dopamine containing cells in the substantia nigra and striatum of human brain using receptor autoradiography. Mertens et al. [110] showed that AT1 and AT2 receptors might exert an opposite effect on the modulation of DA synthesis in the striatum. Speth and Karamyan [111] demonstrated that the novel, non-AT1, non-AT2 binding site for angiotensin peptides as a mediator of nontraditional actions of Ang II, could have a role in the stimulation of dopamine release from the striatum.

Several studies have been made to elucidate the possible link between the brain RAS and the dopaminergic cell death in Parkinson's disease [93, 112, 113]. One hypothesis is that AT1 receptors might play a pivotal role in Parkinson's disease. As mentioned above, the stimulation of AT1 receptors might lead to the activation of the NADPH oxidase complex and the generation of ROS [92, 93]. Mertens et al. [93] proposed that AT2 receptor agonists alone or in combination with AT1 receptor blockers might effectively improve the pathological conditions in Parkinson's disease. It was also shown that chronic treatment of ACEI increased striatal dopamine content in the MPTP-mouse [112]. On the other hand, it was demonstrated that administration of PRR blocker significantly decreased 6-hydroxydopamine-induced dopamine cell death in the cultures, suggesting that the potential neuroprotective strategies for dopamine neurons in Parkinson's disease should address not only Ang II but also PRR signaling [113].

In this context, it can be speculated that the striatal dopaminergic system may actively participate in the control of blood pressure and behavioral responses, although further studies should be performed to assess the precise role of the RAS in the regulation of central dopaminergic nerve activity and its modulation by the RAS inhibitors.

4.2. Acetylcholine Release

Previous studies have shown that the central cholinergic system may also actively participate in blood pressure control [114–123]. Buccafusco and Spector [114] demonstrated that cholinergic stimulation of the central nervous system by direct receptor agonists produced pressor responses involving activation of central muscarinic receptor sites. It was shown that pressor responses induced by intracerebroventricular injection of Ang II were significantly blocked by hemicholinium-3 (an inhibitor of Ach synthesis), which may indicate a possible interaction between the cholinergic nervous system and the RAS in the brain [115]. Vargas and Brezenoff [116] also reported that the decrease in Ach content of the hypothalamus, striatum, and brainstem caused by hemicholinium-3 was associated with a reduction in systemic blood pressure in SHR. In an in vitro study, we have shown that captopril significantly inhibited the stimulation-evoked Ach release in rat striatum [108]. The finding may propose the hypothesis that the inhibition of central cholinergic activity could contribute, at least in part, to the hypotensive mechanisms of captopril.

Recently, the possible link between the brain RAS and the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease has been documented. Tota et al. [124, 125] observed that perindopril and candesartan significantly ameliorated the scopolamine-induced impairment in memory, cerebral blood flow, and cholinergic function in mice. In addition, they suggested that activation of AT1 receptors might be involved in the scopolamine-induced amnesia and that AT2 receptors could contribute to the beneficial effects of the RAS inhibitors. The findings might propose the idea that inhibition of the brain RAS in hypertensive subjects would be neuroprotective against Alzheimer's disease, although further studies are necessary to assess more thoroughly the relationships between the RAS and central cholinergic nerve activity and their roles in the regulation of blood pressure and neurological functions.

4.3. Vasopressin Release

Brain RAS also modulates the cardiovascular and fluid-electrolyte homeostasis by interacting hypothalamic-pituitary axis and vasopressin release [126, 127]. It was shown that the angiotensinogen-deficient rats had lower plasma levels of vasopressin and an altered central vasopressinergic system [128, 129]. It was also demonstrated that PRR receptor knockdown significantly reduced AT1 receptors and vasopressin levels in the renin-angiotensinogen double-transgenic hypertensive mice [83], suggesting that the brain RAS might have a pivotal role in the regulatory mechanisms of vasopressin neurotransmission.

4.4. Glutamate/GABA (γ-Aminobutyric Acid) Release

The role of the brain RAS on glutamate/GABA neurotransmission has also been described [130–132]. It was shown that bilateral microdialysis of the AT1 receptor blocker, ZD7155, into the RVLM significantly decreased glutamate and increased GABA levels [130]. In contrast, administration of AT2 receptor blocker, PD 123319, increased glutamate and decreased GABA levels within the RVLM [131]. Fujita et al. [132] demonstrated that administration of candesartan suppressed ischemia-induced increases in the extracellular glutamate with a concomitant reduction in the production of ROS in the retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury model of the rat, indicating that candesartan might protect neurons by decreasing extracellular glutamate after reperfusion and by attenuating oxidative stress via a modulation of the AT1 receptor signaling. These findings suggested that the RAS might have a crucial role in the regulation of cardiovascular and neurological functions by modulating glutamate/GABA release in the brain.

5. Conclusion

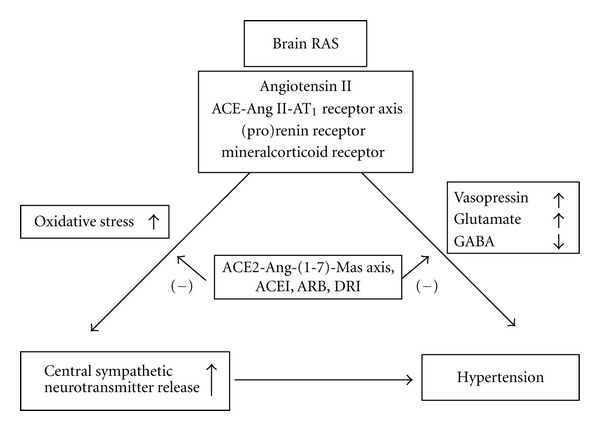

All components of the RAS have been identified in the central nervous system, and the brain RAS may regulate blood pressure by modulating sympathetic nerve activity. It has been proposed that the RAS may have a stimulatory influence on the sympathetic nervous system. The brain RAS may augment presynaptic facilitation of sympathetic neurotransmitter release and enhance the central sympathetic outflow. In the present paper we discussed the relationship between the brain RAS and sympathetic neurotransmitter release in hypertension (Figure 1). Ang II strongly potentiates sympathetic neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system. In contrast, the inhibitors of the RAS, such as ACEIs, ARBs, and DRIs might suppress sympathetic hyperactivity in the brain. The release of vasopressin, glutamate, and GABA could also be altered by the RAS inhibition. Although the clinical significance of the modulation of central sympathetic neurotransmitter release by the RAS inhibitors is not fully understood, the current findings may be consistent with the idea that the neurosuppressive effect could partially contribute to their hypotensive action in hypertension.

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstration of the possible relationship between the brain RAS and sympathetic neurotransmitter release in hypertension. RAS: renin-angiotensin system, ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme, ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker, DRI: direct renin inhibitor, GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid, (–): inhibition.

Clearly, more studies are required to further evaluate the precise role of the brain RAS in the control of sympathetic nerve activity, blood pressure, and neurological functions. In addition, better knowledge of the cellular mechanisms in the brain RAS could provide useful information concerning the development of a more specific and more physiological approach to hypertensive research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan (nos. 15590604, 18590658, 20590710, and 23590901), the Uehara Memorial Foundation (2005), the Takeda Science Foundation (2006), the Salt Science Foundation (2007), and the Mitsui Foundation (2008).

References

- 1.Julius S. Autonomic nervous system dysregulation in human hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 1991;67(10):3B–7B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90813-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasparov S, Teschemacher AG. Altered central catecholaminergic transmission and cardiovascular disease. Experimental Physiology. 2008;93(6):725–740. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haeusler G, Finch L, Thoenen H. Central adrenergic neurones and the initiation and development of experimental hypertension. Experientia. 1972;28(10):1200–1203. doi: 10.1007/BF01946170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vapaatalo H, Hackman R, Anttila P, Vainionpää V, Neuvonen PJ. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on spontaneously hypertensive rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 1974;284(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00499968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer SZ. Presynaptic autoreceptors regulating transmitter release. Neurochemistry International. 2008;52(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuda K, Masuyama Y. Presynaptic regulation of neurotransmitter release in hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1991;18(7):455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1991.tb01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganten D, Speck G. The brain renin-angiotensin system. A model for the synthesis of peptides in the brain. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1978;27(20):2379–2389. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bader M, Peters J, Baltatu O, Müller DN, Luft FC, Ganten D. Tissue renin-angiotensin systems: new insights from experimental animal models in hypertension research. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2001;79(2):76–102. doi: 10.1007/s001090100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baltatu OC, Campos LA, Bader M. Local renin-angiotensin system and the brain—a continuous quest for knowledge. Peptides. 2011;32(5):1083–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diz DI, Arnold AC, Nautiyal M, Isa K, Shaltout HA, Tallant EA. Angiotensin peptides and central autonomic regulation. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2011;11(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balt JC, Mathy MJ, Pfaffendorf M, Van Zwieten PA. Sympatho-inhibitory properties of various AT1 receptor antagonists. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20(5):S3–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacak K, Yadid G, Jakab G, Lenders JWM, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. In vivo hypothalamic release and synthesis of catecholamines in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1993;22(4):467–478. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reja V, Goodchild AK, Phillips JK, Pilowsky PM. Tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in ventrolateral medulla oblongata of WKY and SHR: a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction study. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2002;98(1-2):79–84. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qualy JM, Westfall TC. Release of norepinephrine from the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus of hypertensive rats. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1988;254(5, part 2):H993–H1003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.5.H993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuda K, Yokoo H, Goldstein M. Neuropeptide Y and galanin in norepinephrine release in hypothalamic slices. Hypertension. 1989;14(1):81–86. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide on [3H]norepinephrine release in medulla oblongata of spontaneously hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;191(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Effects of neuropeptide Y on norepinephrine release in hypothalamic slices of spontaneously hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;182(1):175–179. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Effects of Bay K 8644, a Ca2+ channel agonist, on [3H]norepinephrine release in hypothalamus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;194(1):111–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Calcitonin gene-related peptide in noradrenergic transmission in rat hypothalamus. Hypertension. 1992;19(6):639–642. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Modulation of noradrenergic transmission by neuropeptide Y and presynaptic α2 adrenergic receptors in the hypothalamus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Japanese Heart Journal. 1992;33(2):229–238. doi: 10.1536/ihj.33.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Synergistic effects of BAY K 8644 and bradykinin on norepinephrine release in the hypothalamus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1995;22(supplement 1):S54–S57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Role of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in the regulation of norepinephrine release in hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2001;38(1):S27–S31. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200110001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura T, Kumagai H, Kawai A, et al. Rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons of neonatal Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2002;40(4):560–565. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032043.64223.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuda K, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Neuropeptide Y and galanin enhance the inhibitory effects of clonidine on norepinephrine release from medulla oblongata of rats. American Journal of Hypertension. 1990;3(10):800–802. doi: 10.1093/ajh/3.10.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Norepinephrine release and neuropeptide Y in medulla oblongata of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1990;15(6):784–790. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.6.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Modulation of norepinephrine release by galanin in rat medulla oblongata. Hypertension. 1992;20(3):361–366. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Glutamatergic regulation of [3H]-noradrenaline release in the medulla oblongata of normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension. 1994;12(5):517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, et al. Effects of β-endorphin on norepinephrine release in hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2000;36(6):S65–S67. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200000006-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I. Role of α2-adrenergic receptors and cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase in the regulation of norepinephrine release in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2003;42(supplement 1):S81–S85. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teschemacher AG, Wang S, Raizada MK, Paton JFR, Kasparov S. Area-specific differences in transmitter release in central catecholaminergic neurons of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):351–358. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esler MD, Lambert GW, Ferrier C, et al. Central nervous system noradrenergic control of sympathetic outflow in normotensive and hypertensive humans. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 1995;17(1-2):409–423. doi: 10.3109/10641969509087081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fink GD, Haywood JR, Bryan WJ, Packwood W, Brody MJ. Central site for pressor action of blood-borne angiotensin in rat. The American Journal of Physiology. 1980;239(3):R358–R361. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1980.239.3.R358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davern PJ, Head GA. Fos-related antigen immunoreactivity after acute and chronic angiotensin II-induced hypertension in the rabbit brain. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1170–1177. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.086322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Sevilla JA, Dubocovich ML, Langer SZ. Angiotensin II facilitates the potassium-evoked release of 3H-noradrenaline from the rabbit hypothalamus. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1979;56(1-2):173–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Rogers J, Henderson G. Effects of angiotensin II on [3H]noradrenaline release and phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis in the parietal cortex and locus coeruleus of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1987;49(5):1541–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gironacci MM, Valera MS, Yujnovsky I, Peña C. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibitory mechanism of norepinephrine release in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):783–787. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143850.73831.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qadri F, Badoer E, Stadler T, Unger T. Angiotensin II-induced noradrenaline release from anterior hypothalamus in conscious rats: a brain microdialysis study. Brain Research. 1991;563(1-2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stadler T, Veltmar A, Qadri F, Unger T. Angiotensin II evokes noradrenaline release from the paraventricular nucleus in conscious rats. Brain Research. 1992;569(1):117–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90377-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steckelings UM, Paulis L, Namsolleck P, Unger T. AT2 receptor agonists: hypertension and beyond. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2012;21(2):142–146. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328350261b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelband CH, Sumners C, Lu D, Raizada MK. Angiotensin receptors and norepinephrine neuromodulation: implications of functional coupling. Regulatory Peptides. 1998;73(3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)11050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nap A, Balt JC, Mathy MJ, Pfaffendorf M, Van Zwieten PA. Different AT1 receptor subtypes at pre- and postjunctional sites: AT1A versus AT1B receptors. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2004;43(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Devil and angel in the renin-angiotensin system: ACE-angiotensin II-AT1 receptor axis vs. ACE2-angiotensin-(1–7)-Mas receptor axis. Hypertension Research. 2009;32(7):533–536. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwai M, Nakaoka H, Senba I, Kanno H, Moritani T, Horiuchi M. Possible involvement of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and Mas activation in inhibitory effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade on vascular remodeling. Hypertension. 2012;60(1):137–144. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.191452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira AJ, Bader M, Santos RA. Therapeutic targeting of the angiotensin-converting enzyme2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas cascade in the renin-angiotensin system: a potent review. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patients. 2012;22(5):567–574. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.682572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourassa EA, Fang X, Li X, Sved AF, Speth RC. AT1 angiotensin II receptor and novel non-AT1, non-AT2 angiotensin II/III binding site in brainstem cardiovascular regulatory centers of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Brain Research. 2010;1359:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baltatu O, Silva JA, Ganten D, Bader M. The brain renin-angiotensin system modulates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2000;35(1, part 2):409–412. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plosker GL, McTavish D. Captopril: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy after myocardial infarction and in ischaemic heart disease. Drugs & Aging. 1995;7(3):226–253. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199507030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strittmatter SM, Lo MM, Javitch JA, Snyder SH. Autoradiographic visualization of angiotensin-converting enzyme in rat brain with [3H]captopril: localization to a striatonigral pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81(5):1599–1603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unger T, Schull B, Rascher W, Lang RE, Ganten D. Selective activation of the converting enzyme inhibitor MK 421 and comparison of its active diacid form with captopril in different tissues of the rat. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1982;31(19):3063–3070. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen ML, Kurz KD. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in tissues from spontaneously hypertensive rats after treatment with captopril or MK-421. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1982;220(1):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hutchinson JS, Mendelsohn FAO. Hypotensive effects of captopril administered centrally in intact conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats and peripherally in anephric anaesthetized spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1980;7(5):555–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1980.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unger T, Kaufman-Buehler I, Schoelkens B, Ganten D. Brain converting enzyme inhibition: a possible mechanism for the antihypertensive action of captopril in spontaneously hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1981;70(4):467–478. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baum T, Becker FT, Sybertz EJ. Attenuation of pressor responses to intracerebroventricular angiotensin I by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and their effects on systemic blood pressure in conscious rats. Life Sciences. 1983;32(12):1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen ML, Kurz K. Captopril and MK-421: stability on storage, distribution to the central nervous system, and onset of activity. Federation Proceedings. 1983;42(2):171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cushman DW, Wang FL, Fung WC, Harvey CM, DeForrest JM. Differentiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors by their selective inhibition of ACE in physiologically important target organs. American Journal of Hypertension. 1989;2(4):294–306. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berecek KH, Okuno T, Nagahama S, Oparil S. Altered vascular reactivity and baroreflex sensitivity induced by chronic central administration of captopril in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1983;5(5):689–700. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berecek KH, Shier DN. Alterations in renal vascular reactivity induced by chronic central administration of captopril in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension A. 1986;8(7):1081–1106. doi: 10.3109/10641968609045476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Effects of captopril on [3H]-norepinephrine release in rat central nervous system. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1995;22(9):610–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuda K, Shima H, Kuchii M, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Effects of captopril on neurosecretion and vascular responsiveness in hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension A. 1987;9(2-3):375–379. doi: 10.3109/10641968709164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bolterman RJ, Manriquez MC, Ortiz Ruiz MC, Juncos LA, Romero JC. Effects of captopril on the renin angiotensin system, oxidative stress, and endothelin in normal and hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2005;46(4):943–947. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000174602.59935.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Segarra AB, Prieto I, Banegas I, et al. Asymmetrical effect of captopril on the angiotensinase activity in frontal cortex and plasma of the spontaneously hypertensive rats: expanding the model of neuroendocrine integration. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;230(2):423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stancheva S, Alova L, Stefanova M. Effect of peptide and nonpeptide antagonists of angiotensin II receptors on noradrenaline release in hypothalamus of rats with angiotensin II-induced increase of water intake. Pharmacological Reports. 2009;61(6):1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Averill DB, Tsuchihashi T, Khosla MC, Ferrario CM. Losartan, nonpeptide angiotensin II-type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist, attenuates pressor and sympathoexcitatory responses evoked by angiotensin II and L-glutamate in rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Research. 1994;665(2):245–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang BS, White RA, Bi L, Leenen FH. Central infusion of aliskiren prevents sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats on high salt intake. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;302(7):R825–R832. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00368.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gohlke P, Von Kügelgen S, Jürgensen T, et al. Effects of orally applied candesartan cilexetil on central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20(5):909–918. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200205000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishimura Y, Ito T, Hoe K, Saavedra JM. Chronic peripheral administration of the angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonist candesartan blocks brain AT1 receptors. Brain Research. 2000;871(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishimura Y, Ito T, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 blockade normalizes cerebrovascular autoregulation and reduces cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2000;31(10):2478–2486. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Unger T. Inhibiting angiotensin receptors in the brain: possible therapeutic implications. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2003;19(5):449–451. doi: 10.1185/030079903125001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pelisch N, Hosomi N, Ueno M, et al. Systemic candesartan reduces brain angiotensin II via downregulation of brain renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension Research. 2010;33(2):161–164. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esler M. Differentiation in the effects of the angiotensin II receptor blocker class on autonomic function. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20(5):S13–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krum H, Lambert E, Windebank E, Campbell DJ, Esler M. Effect of angiotensin II receptor blockade on autonomic nervous system function in patients with essential hypertension. American Journal of Physiology. 2006;290(4):H1706–H1712. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00885.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Champlain J, Karas M, Assouline L, et al. Effects of valsartan or amlodipine alone or in combination on plasma catecholamine levels at rest and during standing in hypertensive patients. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2007;9(3):168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.05938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Struck J, Muck P, Trübger D, et al. Effects of selective angiotensin II receptor blockade on sympathetic nerve activity in primary hypertensive subjects. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20(6):1143–1149. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200206000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Angeli F, Reboldi G, Mazzotta G, Poltronieri C, Verdecchia P. Safety and efficacy of aliskiren in the treatment of hypertension: a systematic overview. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2012;11(4):659–670. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.696608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dusing R, Brunel P, Baek I, Baschiera F. Sustained decrease in blood pressure following missed doses of aliskiren or telmisartan: the ASSERTIVE double-blind, randomized study. Journal of Hypertension. 2012;30(5):1029–1040. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328351c263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Qasem AA, et al. Effect of aliskiren treatment on endothelium-dependent vasodilation and aortic stiffness in essential hypertensive patients. European Heart Journal. 2012;33(12):1530–1538. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Siddiqi L, Oey PL, Blankestijn PJ. Aliskiren reduces sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(9):2930–2934. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Mugellini A, et al. Effect of aliskiren addition to amlodipine on ankle edema in hypertensive patients: a three-way crossover study. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2011;12(9):1351–1358. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.580276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nguyen G, Delarue F, Burcklé C, Bouzhir L, Giller T, Sraer JD. Pivotal role of the renin/prorenin receptor in angiotensin II production and cellular responses to renin. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109(11):1417–1427. doi: 10.1172/JCI14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nguyen G. Renin, (pro)renin and receptor: an update. Clinical Science. 2011;120(5):169–178. doi: 10.1042/CS20100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burcklé CA, Danser AHJ, Müller DN, et al. Elevated blood pressure and heart rate in human renin receptor transgenic rats. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):552–556. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000199912.47657.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shan Z, Shi P, Cuadra AE, et al. Involvement of the brain (pro)renin receptor in cardiovascular homeostasis. Circulation Research. 2010;107(7):934–938. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li W, Peng H, Cao T, Sato R, et al. Brain-targeted (pro)renin receptor knockdown attenuates angiotensin II-dependent. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1188–1194. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.190108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang BS, Ahmadi S, Ahmad M, White RA, Leenen FHH. Central neuronal activation and pressor responses induced by circulating ANG II: role of the brain aldosterone-“ouabain” pathway. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2010;299(2):H422–H430. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00256.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xue B, Beltz TG, Yu Y, et al. Central interactions of aldosterone and angiotensin II in aldosterone- and angiotensin II-induced hypertension. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2011;300(2):H555–H564. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00847.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang ZH, Yu Y, Kang YM, Wei SG, Felder RB. Aldosterone acts centrally to increase brain renin-angiotensin system activity and oxidative stress in normal rats. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2008;294(2):H1067–H1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01131.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leenen FHH, RuzickaW M, Floras JS. Central sympathetic inhibition by mineralcorticoid receptor but not angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade. Are prescribed doses too low? Hypertension. 2012;60(2):278–280. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huang BS, White RA, Ahmad M, Jeng AY, Leenen FHH. Central infusion of aldosterone synthase inhibitor prevents sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension by central Na+ in Wistar rats. American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2008;295(1):R166–R172. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90352.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raheja P, Price A, Wang Z, et al. Spironolactone prevents chlorthalidone-induced sympathetic activation and insulin resistance in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):319–325. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kishi T, Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Ito K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Increased reactive oxygen species in rostral ventrolateral medulla contribute to neural mechanisms of hypertension in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 2004;109(19):2357–2362. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128695.49900.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hirooka Y. Oxidative stress in the cardiovascular center has a pivotal role in the sympathetic activation in hypertension. Hypertension Research. 2011;34(4):407–412. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu F, Havens J, Yu Q, et al. The link between angiotensin II-mediated anxiety and mood disorders with NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative stress. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacology. 2012;4(1):28–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mertens B, Vanderheyden P, Michotte Y, Sarre S. The role of the central renin-angiotensin system in Parkinson's disease. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2010;11(1):49–56. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Linthorst ACE, De Lang H, De Jong W, Versteeg DHG. Effect of the dopamine D2 receptor agonist quinpirole on the in vivo release of dopamine in the caudate nucleus of hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;201(2-3):125–133. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90335-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Linthorst ACE, Van Giersbergen PLM, Gras M, Versteeg DHG, De Jong W. The nigrostriatal dopamine system: role in the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Brain Research. 1994;639(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Alterations in catecholamine release in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Japanese Heart Journal. 1991;32(5):701–709. doi: 10.1536/ihj.32.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Facilitatory effects of diltiazem on dopamine release in the central nervous system. Focus on interactions with D2 autoreceptors and guanosine triphosphate binding proteins. American Journal of Hypertension. 1992;5(9):642–647. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.9.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Effects of verapamil and diltiazem on dopamine release in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1993;20(10):641–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1993.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Modulation of [3H]dopamine release by neuropeptide Y in rat striatal slices. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;321(1):5–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Effects of galanin on dopamine release in the central nervous system of normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. American Journal of Hypertension. 1998;11(12):1475–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Badoer E, Wurth H, Turck D, et al. Selective local action of angiotensin II on dopaminergic neurons in the rat hypothalamus in vivo. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 1989;340(1):31–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00169203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jenkins TA, Chai SY, Mendelsohn FAO. Effect of angiotensin II on striatal dopamine release in the spontaneous hypertensive rat. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 1997;19(5-6):645–658. doi: 10.3109/10641969709083176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brown DC, Steward LJ, Ge J, Barnes NM. Ability of angiotensin II to modulate striatal dopamine release via the AT1 receptor in vitro and in vivo. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118(2):414–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mendelsohn FAO, Jenkins TA, Berkovic SF. Effects of angiotensin II on dopamine and serotonin turnover in the striatum of conscious rats. Brain Research. 1993;613(2):221–229. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lu SF, Young HJ, Lin MT. Nigrostriatal dopamine system mediates baroreflex sensitivity in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;190(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11489-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Georgiev V, Gyorgy L, Getova D, Markovska V. Some central effects of angiotensin II. Interactions with dopaminergic transmission. Acta Physiologica et Pharmacologica Bulgarica. 1985;11(4):19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Banks RJA, Mozley L, Dourish CT. The angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors captopril and enalapril inhibit apomorphine-induced oral stereotypy in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;58(4):799–805. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Captopril inhibits both dopaminergic and cholinergic neurotransmission in the central nervous system. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1998;25(11):904–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jenkins TA, Allen AM, Chai SY, Mendelsohn FAO. Interactions of angiotensin II with central catecholamines. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 1995;17(1-2):267–280. doi: 10.3109/10641969509087070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mertens B, Vanderheyden P, Michotte Y, Sarre S. Direct angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation decreases dopamine synthesis in the rat striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(7):1038–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Speth RC, Karamyan VT. Brain angiotensin receptors and binding proteins. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2008;377(4–6):283–293. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jenkins TA, Wong JYF, Howells DW, Mendelsohn FAO, Chai SY. Effect of chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on striatal dopamine content in the MPTP-treated mouse. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73(1):214–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Valenzuela R, Barroso-Chinea P, Villar-Cheda B, et al. Location of prorenin receptors in primate substantia nigra: effects on dopaminergic cell death. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2010;69(11):1130–1142. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181fa0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Buccafusco JJ, Spector S. Role of central cholinergic neurons in experimental hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1980;2(4):347–355. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Buccafusco JJ, Serra M. Role of cholinergic neurons in the cardiovascular responses evoked by central injection of bradykinin or angiotensin II in conscious rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1985;113(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vargas HM, Brezenoff HE. Suprression of hypertension during chronic reduction of brain acetylcholine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension. 1988;6(9):739–745. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Effects of verapamil on [3H]acetylcholine release in the striatum of spontaneously hypertensive rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;216(2):319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90378-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Effects of nicardipine on the release of acetylcholine in the rat central nervous system. Japanese Circulation Journal. 1993;57(10):993–999. doi: 10.1253/jcj.57.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Masuyama Y, Goldstein M. Effects of diltiazem on [3H]-acetylcholine release in rat central nervous system. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1994;21(7):533–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Masuyama Y. Inhibitory effects of verapamil on [3H]-acetylcholine release in the central nervous system of Sprague-Dawley rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1994;21(7):527–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Goldstein M, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. Glutamatergic regulation of [3H]acetylcholine release in striatal slices of normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neurochemistry International. 1996;29(3):231–237. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(96)00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I, Masuyama Y. The release of acetylcholine and its dopaminergic regulation in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1999;34(supplement 4):S53–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tsuda K, Tsuda S, Nishio I. Role of protein kinase C in the regulation of acetylcholine release in the central nervous system of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2003;41(supplement 1):S57–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tota S, Nath C, Najmi AK, Shukla R, Hanif K. Inhibition of central angiotensin converting enzyme ameliorates scopolamine induced memory impairment in mice: role of cholinergic neurotransmission, cerebral blood flow and brain energy metabolism. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;232(1):66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tota S, Hanif K, Kamat PK, Najmi AK, Nath C. Role of central angiotensin receptors in scopolamine-induced impairment in memory, cerebral blood flow, and cholinergic function. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2012;222(2):185–202. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Campos LA, Bader M, Baltatu OC. Brain renin-angiotensin system in hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure. Frontiers in Physiology. 2011;2, article 115 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Baltatu O, Campos LA, Bader M. Genetic targeting of the brain renin-angiotensin system in transgenic rats: impact on stress-induced renin release. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2004;181(4):579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schinke M, Baltatu O, Böhm M, et al. Blood pressure reduction and diabetes insipidus in transgenic rats deficient in brain angiotensinogen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(7):3975–3980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Campos LA, Couto AS, Iliescu R, et al. Differential regulation of central vasopressin receptors in transgenic rats with low brain angiotensinogen. Regulatory Peptides. 2004;119(3):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Patel D, Böhlke M, Phattanarudee S, Kabadi S, Maher TJ, Ally A. Cardiovascular responses and neurotransmitter changes during blockade of angiotensin II receptors within the ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience Research. 2008;60(3):340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tedesco A, Ally A. Angiotensin II type-2 (AT2) receptor antagonism alters cardiovascular responses to static exercise and simultaneously changes glutamate/GABA levels within the ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience Research. 2009;64(4):372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fujita T, Hirooka K, Nakamura T, et al. Neuroprotective effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1-R) blocker via modulating AT1-R signaling and decreased extracellular glutamate levels. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2012;53(7):4099–4110. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]