Abstract

Background:

It is not clear if the role of antipsychotics in long-term clinical and functional recovery from schizophrenia is correlated. The pattern of use is a major aspect of pharmacotherapy in long-term follow-ups of schizophrenia. The aim of this study was to examine patterns of antipsychotic usage in patients with longstanding psychosis and their relationship to social outcomes.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study on a cohort from a long-term outcome study. Participants were 116 first episode schizophrenia patients from Mumbai, India, who had more than 80% compliance, as reported by relatives. Patients were assessed on antipsychotic medication use and on clinical and functional parameters.

Results:

There was a high compliance rate (72%). Most patients (77%) used atypical antipsychotics; only 10 (8.6%) patients were taking typical antipsychotics. There were no among-drug differences in the percentage of patients meeting the recommended dose: Clozapine (200–500 mg), Riseperidone (4.0–6.0 mg), Olanzapine (10–20 mg), Quetiapine (400–800 mg), Aripiprazole (15–30 mg), Ziprasidone (120–160 mg); an equivalent dosage of Chlorpromazine (300–600 mg) did not differ amongst any atypical antipsychotic subgroup. Also, we did not find any significant differences in recovery on Clinical Global Impression Severity scale (CGIS), Quality of Life (QOL), or Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) between groups of antipsychotic drugs.

Conclusion:

This study shows that most patients suffering from schizophrenia, in a long-term follow-up, use prescribed atypical antipsychotics within the recommended limits. Also, the chlorpromazine equivalence dosages do not differ across antipsychotic medications. The outcomes on clinical and functional parameters are also similar across all second-generation antipsychotics.

Keywords: Antipsychotics, long-term outcome, prescribing, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a complex neurobehavioral disorder affecting about 1% of the general population. Medications are the main form of treatment in schizophrenia and consist primarily of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics. These drugs have several short-term, as well long-term advantages, and help to reduce symptomologies and increase adherence.[1] Despite these factors, outcomes in schizophrenia continue to be limited, and regardless of effective treatments, many patients with schizophrenia do not improve and do not become symptom free. Hegarty et al. (1994) conducted a meta-analysis from 100 years of outcome literature gathered from 1885 to 1985, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.[2] They attributed this to inconsistencies in the parameters of defining outcome and lack of effective treatments available at that time. Responses to antipsychotic drugs have been far better in short-term rather than in long-term recovery[3] and it is still not known if atypical antipsychotics have long-term effects that improve the outcome.[4,5] It is generally accepted that all antipsychotics are equally effective but differ only in terms of their safety profile.[6]

Prescribing patterns of antipsychotics has seen a major shift in the last two decades, from first generation to second generation, with the majority of patients suffering from schizophrenia being treated with second-generation antipsychotics (although first-generation drugs are reported to be equally effective as the second-generation drugs, preference for prescribing second-generation drugs continues).[7] With all these factors under consideration, the role of antipsychotics in long-term recovery of schizophrenia still remains questionable as it is not yet clear if effect of these medications is correlated with levels of clinical and functional recovery. Therefore, understanding the pattern of use of antipsychotic medications is a major aspect of pharmacotherapy with respect to long-term follow-ups of schizophrenia.

The objective of this study was to examine the pattern of antipsychotic usage in patients with longstanding psychosis and its relationship to social outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants were consenting subjects, recruited from a 10-year follow-up study. These individuals had been diagnosed with schizophrenia as per DSM IV, had been taking treatment consistently, and had a high level of compliance (>80% compliance from self-reports of patients and relatives). This was a cross-sectional study in a naturalistic clinical setting, and was conducted in a non-governmental Psychiatric Treatment Centre in Mumbai, India (licensed center as per Indian Mental Health Act 1987). Local independent ethics committee approved the study. We screened 161 patients who had completed 10 years of treatment in a long-term follow-up study of first episode schizophrenia, and 116 (72%) were recruited based upon more than 80% treatment compliance, as per relatives’ and patients’ information which meant they were highly compliant. Out of the 116 patients, 89 (77%) used atypical antipsychotics; 81 (69.8%) used a single medication and 35 (30.1%) used more than one [21 (18.1%) used two and 14 (12%) used three] atypical antipsychotics. Eleven (9.4%) patients were not taking any medications.

The mean age of subjects was 39.2 years (SD=7.9; range 22–58). 74% of these subjects were males living in catchments with families and belonged to the middle-class socioeconomic group. These patients were assessed on parameters of psychopathology and functioning using Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS),[8] Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),[9] Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF),[10] and the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL-BREF).[11] We defined clinical outcomes as “improved” and “much improved” using the Clinical Global Impression Severity scale (CGIS).[12] Parameters of social outcome, namely, independent living and family burden, are based on a score of more than 3, on a scale of 1–5 (1 being minimal improvement and 5 being greatest improvement). Chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalent dose was calculated as per guidelines.[13,14]

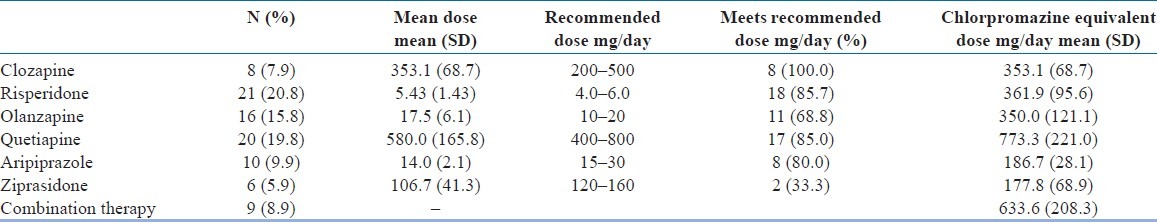

Forty (24.8%) patients were repeatedly hospitalized during the course of the 10 years, and 18 (12.9%) were hospitalized during the 2 years prior to the end of the study. As revealed in the clinical history, 31 (26.7%) patients showed a range of suicidal ideation, crisis, or attempts during the 2 years prior to the end of the study. About 40 (24%) of the patients had significant persisting or residual symptoms despite treatment. Those taking a single second-generation antipsychotic drug, 6 months prior to the end of the study, were analyzed by: type of medication, dosage, chlorpromazine equivalent dosage, and their correlation with parameters of clinical and functional outcome. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1. The frequencies and percentages of atypical antipsychotics are presented in Table 1; thus, our methods and results are descriptive in nature.

Table 1.

Atypical antipsychotic use

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study reports that there was high compliance (72%) to treatment regimens and there were no among-drug differences in the percentage of patients meeting the recommended dose (P=0.056, Fisher's exact test). As seen in Table 1, the chlorpromazine equivalent dosage also did not differ amongst any atypical antipsychotics subgroup.

One of the findings of this study was a high compliance rate (72%) to treatments. This was found using criteria of more than 80% compliance, as per self-report of the patients and their relatives. Self-report is, by far, the most unreliable, but most frequently used measure of compliance.[15] Thus, the results of this study need to be interpreted with caution. High compliance has been reported in other studies as well.[16] The expert consensus guidelines on adherence reported a maximum compliance as 71%, which was determined by most of the experts who participated.[17] In one study by Velligan et al. (2003)[18,19] it was reported that when adherence was defined as 80%, 3 months later, only 40% were adherent based upon pill count. A possible explanation for this high compliance rate may be that these subjects were having closer follow-ups, most of which were accompanied by family members, and they themselves were paying for the medications. Moreover, these patients have undergone long-term care, have suffered repeated hospitalization, and have seen the benefit of continuing medications. It is likely that all these factors might have resulted in a relatively higher compliance. Perception of the authority figure of doctors in Indian culture, monitoring opportunity by the relatives, and number of patients living in the family might also have contributed to this. Many other studies have examined compliance; however, these have been in a short-term treatment setting. Compliance in long-term treatment is still not very clear.

In the present study, the majority of patients (77%) were treated with atypical antipsychotics. In the last two decades, there has been a shift in prescribing antipsychotics. Several factors are held responsible for this change, some of which include: a lower reported incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and Tardive Dyskinesia (TD), intensive focus on research and education about atypical antipsychotics, as well as the presence of a strong market force of companies and physicians choosing to try something new in the hopes of maximizing outcomes.[20] A number of studies have shown that second-generation antipsychotics were the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic medication.[21,22] A recent study by Monshat et al. (2010)[23] observed that second-generation antipsychotic medications were the most widely used agents (79% in 2004, 99% in 2007) of all other types of antipsychotics. Another study by Hollingsworth et al. (2010)[20] conducted in Australia also confirmed that the proportion of prescribed atypical antipsychotics increased from 61% in 2002 to 77% in 2007.

Our study shows that the majority of patients (77%) rely on second-generation antipsychotics to treat chronic schizophrenia and 30.1% of patients were taking more than one second-generation antipsychotic. This is parallel to the findings reported in the literature. A study by Kontis et al. (2010)[21] reported that despite consistent recommendations for antipsychotic monotherapy (the use of one antipsychotic agent), antipsychotic polypharmacy (the use of two or more antipsychotic agents) and the administration of excessive doses (higher than 1000 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents) is a common practice in the treatment of schizophrenia.[24] Conversely, the therapeutic and adverse effects of this practice include cognitive deficits which further contribute to poor outcomes. Surveys of prescribing antipsychotic agents in psychiatric services internationally have identified the relatively frequent and consistent use of combined antipsychotics, as the use of polypharmacy is usually done for people with established schizophrenia, with a prevalence of up to 50% in some clinical settings;[25] however, in one of our studies from India, it was found that 84% of physicians preferred to prescribe a single antipsychotic drug (Clozapine) while 16% preferred combination with conventional antipsychotics.[26] A common reason for prescribing more than one antipsychotic is to gain a greater or more rapid therapeutic response than what has been achieved with antipsychotic monotherapy, but the evidence on the risks and benefits for such a strategy is equivocal. Our results are comparable to the prevailing literature that about 30–40% of patients use more than one (up to three or four) antipsychotic medications, particularly with respect to long-term treatments. We also found that the mean dosage of antipsychotics were within the normal recommended limits. It has been suggested that in maintenance of antipsychotic therapies, the optimal dosage range is 300–600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents daily.[27] In this study, all medications except Quetiapine (773 mg/ day of CPZ equivalent) were within these recommended limits.

The more chronic stages of schizophrenia are associated with higher antipsychotic doses and diminished clinical response.[28,29] Chronic populations include a larger proportion of refractory patients who may be receiving higher doses.[30] In chronic refractory patients, the role of antipsychotics continues to be undermined. It is recommended that a maintenance dose of antipsychotics should generally be 50% of the dose which provides clinical recovery.[31] From this perspective, the mean dosage appears to be marginally high. This may be because the patient population was having significantly higher instances of recovery from psychopathology and physicians were using high doses in the hopes of maintaining the recovery. This pattern of prescribing needs to be reviewed. A study by Harrow and Jibe (2007)[30] reported from a series of 64 schizophrenic patients followed up 5 times over 15 years that a larger percentage of schizophrenic patients, who were not on antipsychotics, showed periods of recovery and better global functioning.[32] These longitudinal data suggest that not all schizophrenic patients need to use antipsychotic medications continuously throughout their lives. Respective mean dosages of antipsychotics do not show any significant differences, suggesting that all antipsychotics are equally effective.[31] Our findings regarding actual dose or chlorpromazine equivalent dosage are in line with the published data which state that all atypical antipsychotics were found to be equally effective.

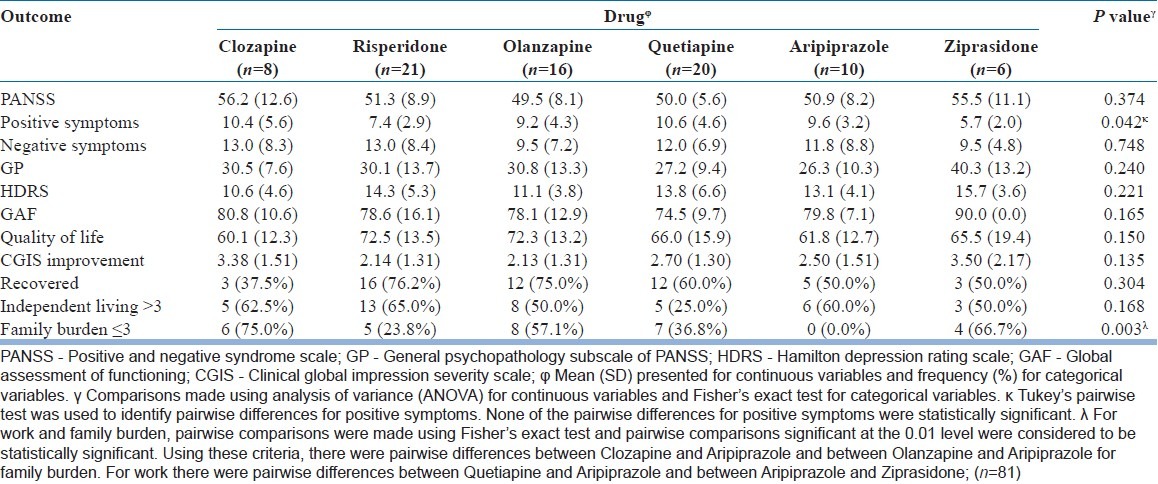

In the present study, we did not find any significant difference in recovery on the CGIS, QOL, or GAF between groups of different antipsychotic drugs Table 2. Restoration of quality of life is considered the sought-after treatment goal in the management of schizophrenia, since expectations have increased after the advent of newer drugs. This is in line with the current literature that atypical antipsychotics do not differ across clinical or social parameters.[32] However, few studies have demonstrated that antipsychotic medications significantly differed in beneficial impact on productivity level in the long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia. With regards to our study, the best example of this comes from the usage of Clozapine, but due to small sample size, it is not possible to address this complex question. We used an empirical scale which has been standardized and successfully used earlier in our study (a score of 1 being no burden and a score of 5 being maximum burden). Based on this outcome parameter, this study reflects that a significantly lesser burden was caused by Clozapine.

Table 2.

Ten-year outcomes by drugs for subjects on atypical antipsychotic monotherapy

As stated previously, some medications, particularly Clozapine, have demonstrated some effects of reducing the family burden by improving the overall outcome of patients. Antipsychotics also did not differ in the parameter of independent living. Geographic and cultural factors have also been described amongst patient's independent living capacity, which could account for inconsistencies within different social outcomes, which partially explains our findings.

Limitations

The present study has some methodological limitations which make it difficult to interpret the data and derive specific conclusions. There are inherent problems because the study was not designed to answer the question of dosing and effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics; it only represents findings of a cross-sectional assessment. The comparison between medications and outcome needs to be read with caution, as the results merely represent the distribution of medications on outcome.

CONCLUSION

The present study shows that most patients of schizophrenia, in long-term follow-ups, use prescribed atypical antipsychotics within the recommended limits. Also, their chlorpromazine equivalent dosages do not differ across antipsychotic medications. Although the mean actual dose and chlorpromazine equivalent dosage are within the recommended limits, individually these dosages are on the upper limits of treatment maintenance among the Indian population. The outcome on clinical and functional parameters is also similar across all second-generation antipsychotics; however, more research is necessary to understand the prescribing patterns of antipsychotics in long course of schizophrenia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Refer Kane JM, Correll CU. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:345–57. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/jkane. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, Waternaux C, Oepen G. One hundred years of schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1409–16. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Shah N, Bureau Y. Redefining outcome measures in schizophrenia: Integrating social and clinical parameters. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:120–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336662e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley PF. Factors that influence treatment success in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 3):4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam DA, Janicak PG. The role of psychopharmacotherapy in improving the long-term outcome of schizophrenia. Essent Psychopharmacol. 2005;6:127–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Möller HJ. Novel antipsychotics in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2004;5:9–19. doi: 10.1080/15622970410029902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakos M, Lieberman J, Hoffman E, Bradford D, Sheitman B. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: A review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:518–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO (MNH7PSF/93.9) Geneva: WHO; 1993. WHO-BREF World Health Organization. WHOQoL Study Protocol. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy W. Clinical Global Impression (CGI) ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:663–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:192–208. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000117422.05703.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goff DC, Hill M, Freudenreich O. Treatment adherence in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:e13. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9096tx6cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samalin L, Guillaume S, Auclair C, Llorca PM. Adherence to guidelines by French psychiatrists in their real world of clinical practice. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:239–43. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182125d4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crossley N. A Constante M, Efficacy of atypical v. typical antipsychotics in the treatment of early psychosis: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:434–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velligan DI, Lam F, Ereshefsky L, Miller AL. Psychopharmacology: Perspectives on medication adherence and atypical antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:665–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: Adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 4):1–46. quiz 47-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ, Nissen LM, Robinson M, Hall WD. Patterns of antipsychotic medication use in Australia 2002-2007. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:372–7. doi: 10.3109/00048670903489890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontis D, Theochari E, Kleisas S, Kalogerakou S, Andreopoulou A, Psaras R, et al. Doubtful association of antipsychotic polypharmacy and high dosage with cognition in chronic schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:1333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes TR, Paton C. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia: Benefits and risks. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:383–99. doi: 10.2165/11587810-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monshat K, Carty B, Olver J, Castle D, Bosanac P. Trends in antipsychotic prescribing practices in an urban community mental health clinic. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18:238–41. doi: 10.3109/10398561003681327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrivastava A, Shah N. Perscribing practices of clozapine in India: Results of opinion survey of psychiatrists. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:225–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.55097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiden P, Aquila R, Standard J. Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs and Long- Term Outcome in Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 11):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieberman JA. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia: Efficacy, safety and cost outcomes of CATIE and other trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:e04. doi: 10.4088/jcp.0207e04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keefe RS, Bilder RM, Davis SM, Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Gold JM, et al. Neurocognitive Working Group. Neurocognitive effects of antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in the CATIE Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:633–47. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remington G, Kapur S. Antipsychotic dosing: How much but also how often? Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:900–3. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrow M, Jibe TH. Factors Involved in Outcome and Recovery in Schizophrenia Patients Not on Antipsychotic Medications: A 15-Year Multifollow-Up Study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:406–14. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuss P, Tessier C. Antipsychotic medication, functional outcome and quality of life in schizophrenia: Focus on amisulpride. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:787–801. doi: 10.1185/03007990903576953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Essali A, Adams C. Evidence of clozapine's effectiveness in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:990–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]