Abstract

GW182 binds to Argonaute (AGO) proteins and has a central role in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Using lentiviral shRNA-induced GW182 knockdown in HEK293 cells, this study identifies a new role of GW182 in regulating miRNA stability. Stably knocking down GW182 or its paralogue TNRC6B reduces transfected miRNA-mimic half-lives. Replenishment of GW182 family proteins, as well as one of its domain Δ12, significantly restores the stability of transfected miRNA-mimic. GW182 knockdown reduces miRNA secretion via secretory exosomes. Targeted siRNA screening identifies a 3′–5′ exoribonuclease complex responsible for the miRNA degradation only when GW182 is knocked down. Immunoprecipitation further confirms that the presence of GW182 in the RISC complex is critical in protecting Argonaute-bound miRNA.

Keywords: GW182, microRNA, Argonaute proteins

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have become a principal focus in many biological processes owing to their potent ability to moderate target messenger RNA function. Maintaining proper levels of cellular miRNA is important for normal cellular activities. Although different mechanisms have been reported to regulate each step of the miRNA biogenesis process, the understanding of mature miRNA turnover is lagging behind [1]. Several recent studies begin to shed light on this issue by demonstrating that particular mature miRNAs show dynamic and distinct turnover rates during the cell cycle [2, 3]. In contrast, global transcriptional arrest reveals that the majority of miRNA remain stable, with a few exceptions, suggesting a protective mechanism against decay under quiescent condition [4]. Argonaute (AGO) directly associate with miRNAs and might protect miRNA from being degraded from ribonuclease. In fact, AGO have been shown to positively correlate with mature miRNA levels [5]. A recent report directly shows that AGO increased miRNA abundance owing to enhanced mature miRNA stability [6].

GW182 and its longer isoform TNGW1 serve as downstream repressors of AGO for gene silencing [7]. Three studies simultaneously report that GW182 can directly interact and recruit the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex through carboxy-terminal-conserved W motifs independent of PABP interaction [8, 9, 10]. Thus, GW182 functions as a coordinative platform that disrupts circularized mRNA by interacting with PABP to initiate translational interference. As GW182 binds to AGO to have a central role in miRNA-mediated gene silencing, an interesting question is whether the AGO–GW182 interaction also has a role in protecting AGO-associated mature miRNA on top of their silencing function. Here, we have identified a new function of GW182 in protecting mature miRNA from being degraded by interacting with AGO.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Knockdown of GW182 impaired miRNA stability

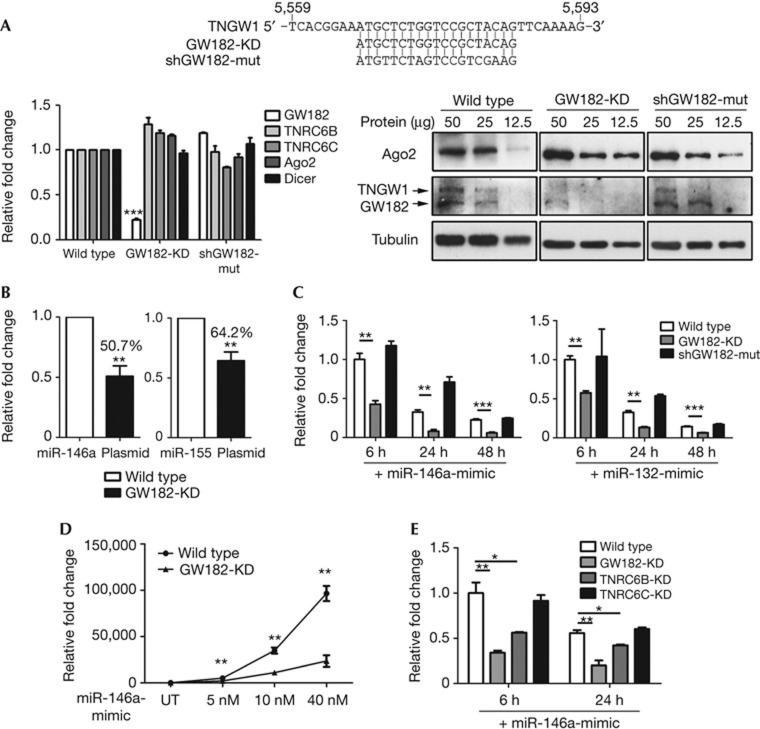

A lentiviral-based short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) strategy was used to generate stable GW182-knockdown cells (GW182-KD) and a negative control shGW182-mut cell line (Fig 1A). GW182-KD showed a specific and effective reduction of GW182 mRNA (79%) without affecting its paralogues, TNRC6B and TNRC6C, Ago2 and Dicer. In contrast, shGW182-mut had no significant changes. Compared with wild-type 293 in western blot analysis, GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells showed elevated Ago2 protein levels (Fig 1A, compare lanes with 12.5 μg protein); this increase in Ago2 levels from transfection of siRNA was reported [11]. In contrast, both GW182 and TNGW1 proteins were effectively knocked down in GW182-KD, but not in shGW182-mut cells (compare lanes with 50 or 25 μg protein).

Figure 1.

Knockdown of GW182 and TNRC6B impaired miRNA stability. (A) Stable HEK293 cell line derived from lentiviral shRNA showed effective and specific knockdown of GW182. Top panel shows GW182/TNGW1 sequence for shRNA. A negative control lentiviral construct was also generated with mismatched mutations (shGW182-mut). The two stable lines were referred as GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells. Left: GW182-KD cells demonstrated knockdown of GW182 by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR without affecting mRNA of TNRC6B, TNRC6C, Ago2 and Dicer. Right: cell lysates were loaded at 50, 25 and 12.5 μg total protein for semiquantitative western blot analysis. (B) Transfected plasmid-encoded miRNA levels reduced in GW182-KD cells compared with wild type by quantitative PCR. Plasmid-encoding pre-miR-146a and pre-miR-155 were transfected in both wild-type HEK293 and GW182-KD cells for 24 h. (C) Transfected miRNA levels via miRNA-mimic also reduced in GW182-KD compared with wild type and shGW182-mut control. Synthetic miR-146a- and miR-132-mimic were transfected into wild-type, GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells and RNA samples harvested 6, 24 and 48 h later. The miRNA levels in wild type with 6-h transfection were normalized to 1. (D) Transfected miR-146a after 24 h showed more rapid elimination in 5, 10 and 40-nM transfection concentrations in GW182-KD cells compared with wild type. (E) Stability of transfected miRNA was most significantly affected in GW182-KD and TNRC6B-KD, but not in TNRC6C-KD cells. The miR-146a level in wild type with 6 h transfection was normalized to 1. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. AGO, Argonaute; miRNA, microRNA; shRNA, short-hairpin RNA.

Levels of miR-146a or miR-155 were significantly lower (50.7 and 64.2%, respectively) in GW182-KD cells compared with wild type (normalized to 1, Fig 1B) when they were transfected with their respective expression plasmids. In separate experiments, luciferase reporters used in previous study [12] were transfected in both wild-type and GW182-KD cells demonstrating that they had comparable transfection efficiency (data not shown). This observation led us to consider the role of GW182 in regulating miRNA stability.

To directly evaluate the mature miRNA levels, 40 nM of miR-146a-mimic and miR-132-mimic were transfected into wild-type, GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells seeded in equal cell number. Cells were harvested at 6, 24 and 48 h to analyse for miRNA levels by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig 1C). miR-146a levels in GW182-KD cells were 42.7% compared with the level in wild type at 6 h, 24.3% at 24 h and 25.5% at 48 h. Similar results were observed with transfection of miR-132-mimic. On the basis of this data, the half-life of miR-146a was determined to be 15.3 and 9.0 h in wild-type and GW182-KD cells, respectively. Correspondingly, the half-life of miR-132 was 11.9 h in wild-type and 8.8 h in GW182-KD cells. As GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells showed elevated Ago2 protein levels (Fig 1A), the reduced miRNA level in GW182-KD cells could not be explained by the increased Ago2 levels. These data suggested a direct role of GW182 in maintaining miRNA stability.

Synthetic miRNA-mimics were primarily used in subsequent studies to evaluate the impact of GW182 knockdown on miRNA levels. miRNA-mimics are used in similar studies to monitor the dynamic changes of miRNA during different cellular activity and proved to be faithfully recapitulating endogenous miRNA activity [2]. Transfected miRNA-mimics offered a boosted signal for easy detection, as well as potentially saturating compensatory GW182 paralogues. miR-146a-mimic transfection was also performed in concentrations of 5, 10 and 40 nM for 24 h, and significant lower levels (41.4, 31.8 and 24.4%, respectively) were observed in GW182-KD cells compared with wild type in all three concentrations tested (Fig 1D). As the levels of transfected miRNA were lower as early as 6 h comparing GW182-KD with wild type, its levels in two earlier time points were also examined (supplementary Fig S1A online). miR-146a levels were comparable at 2 h but became significantly reduced at 4 h comparing GW182-KD with wild type, suggesting the miRNA degradation began from 2 h post transfection. Taken together, these data demonstrated that GW182 knockdown significantly reduced mature miRNA levels.

To examine how GW182 knockdown influenced endogenous miRNA expression, levels of 12 endogenous miRNA were analysed in RNA samples collected from wild-type HEK293, GW182-KD and shGW182-mut cells. Seven out of twelve miRNAs show significantly lower levels in GW182-KD compared with shGW182-mut cells. Interestingly, levels of these seven miRNA (CT: 21–32) were generally higher than levels of the five showing no statistical difference (CT: 26–36, supplementary Fig S2 online). Thus, the stability of high-abundance endogenous miRNAs appeared more sensitively regulated by GW182. These data are consistent with the data from the analysis using miRNA-mimics.

In mammals, there are three paralogues of GW182 with gene names TNRC6A, B and C. These paralogues shared broad functional similarities in terms of AGO interaction and miRNA-mediated repression in tethering functional assays [13, 14, 15]. Transient knockdown of individual paralogue caused partial derepression of reporter activity, also implying their functional redundancy [15]. To investigate whether TNRC6B and TNRC6C also have a role in regulating miRNA stability, lentiviral shRNA-based stable TNRC6B knockdown (6B-KD) and TNRC6C knockdown (6C-KD) cells were also established. MiR-146a-mimic was again transfected into wild-type, GW182-KD, 6B-KD and 6C-KD cells for 6 and 24 h. TNRC6B, but not TNRC6C, was also required for miRNA stability in these two time points (Fig 1E). The 6B-KD and 6C-KD cells had 30.8 and 43.7% knockdown for TNRC6B and TNRC6C mRNA, respectively (supplementary Fig S1B online). The functional differences among GW182 and its paralogues have not been observed so far in different functional assays [14, 15].

Replenishment of GW182 restored miRNA stability

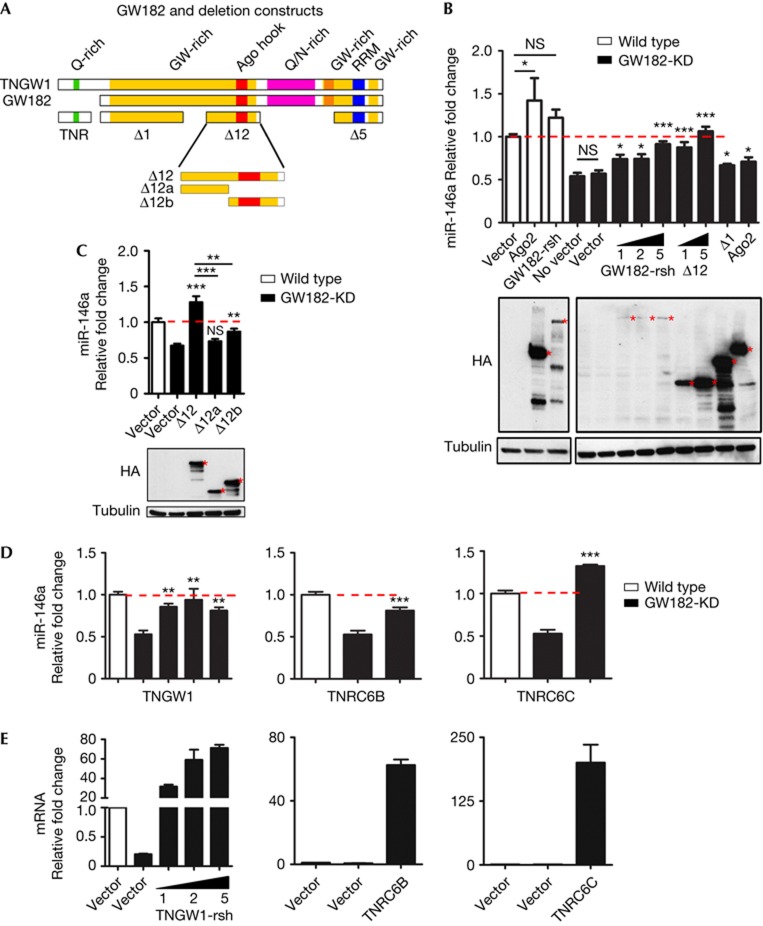

As knockdown of GW182 and TNRC6B reduced miRNA stability, complementation experiments were performed to confirm this new role of GW182. Transfections of 5 μg NHA vector, NHA-Ago2 and NHA-GW182 were introduced into wild-type cells by nucleofection for 16 h, followed by transfection of miR-146a-mimic. Total RNA was harvested 6 h later for miR-146a quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR analysis (Fig 2B, open bars). miR-146a levels in wild-type cells transfected with vector alone were normalized to 1. miR-146a level increased 42.2% when co-transfected with NHA-Ago2, consistent with the observation that elevated Ago2 enhanced miRNA level [5]. NHA-GW182 transfection only mildly increased the transfected miR-146a level and was not statistically significant compared with the NHA vector control in wild-type cells. The transfected miR-146a level in GW182-KD cells without plasmid transfection (no vector) showed reduced level (53.9%) compared with wild type, consistent with the data already shown in Fig 1C. The transfected miR-146a level in vector-alone transfection did not show any significant difference compared with no-vector control in GW182-KD cells (Fig 2B). In contrast, the transfected miR-146a level in GW182-KD cells was restored to comparable levels as in wild-type cells with the expression of a GW182 construct that was specifically mutated to be resistant to the lentiviral shRNA (GW182-rsh), in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 2B, 1 μg, 74.0%; 2 μg, 74.1%; and 5 μg, 91.4% compared with 56.9% for vector alone). Interestingly, transfection of the previously defined repression domain Δ12 also strongly restored transfected miR-146a levels comparable to full-length GW182 (1 μg, 87.4%; 5 μg, 106 versus 56.9% for vector alone). Another GW182 fragment Δ1 showed mild restoration of miR-146a level (5 μg, 66.7 versus 56.9%). Transfection of Ago2 also showed mild restoration (5 μg, 70.8 versus 56.9%) and this might imply that GW182 was a limiting factor in this reaction. All transfected constructs were monitored in western blot, ruling out the effects caused solely by differential protein expression (Fig 2B).

Figure 2.

Replenishment of GW182 and its paralogues restored the shortened miRNA stability. (A) Schematic map shows TNGW1, GW182 and their truncated fragments. (B) Re-expression of GW182 and its silencing domain Δ12 in GW182-KD cells restored miRNA stability in a dose-dependent manner. Expression of transfected proteins were monitored by blotting with anti-HA antibodies. Recombinant proteins are indicated with red asterisks. (C) Fragments of Δ12 rendered less effective in the same complementation assay as in B. (D) Re-expression of GW182-longer isoform TNGW1, TNRC6B or TNRC6C in GW182-KD cells restored miRNA level. (E) Efficient expression of transfected TNGW1, TNRC6B and TNRC6C were monitored by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR analysis of respective mRNA. Comparisons were with vector alone in GW182-KD cells except otherwise indicated by more lines. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. AGO, Argonaute; HA, haemagglutinin; miRNA, microRNA; NS, not significant.

As Δ12 was able to restore the stability of the transfected miRNA, two Δ12 fragments, Δ12a and Δ12b, were nucleofected in GW182-KD cells for a direct comparison with Δ12 (Fig 2C). Neither Δ12a nor Δ12b exerted comparable complementary effects as Δ12, indicating the importance of integrity for the whole Δ12 fragment, although Δ12b showed significant complementary effect compared with vector alone. The Δ12 activity might exert its ability to bind to Ago2, as it possesses two predefined Ago2-binding regions [16]. The principal GW182-silencing domain represented by the C-terminal domain Δ5 was only mildly effective in restoring stability of the transfected miR-146a in GW812-KD cells (data not shown). Note that although Δ5 has a strong silencing function, it has low or no AGO-binding ability [12].

Re-expression of TNGW1 in GW182-KD cells by transfection of a shRNA-resistant GFP-TNGW1 construct in increasing amounts (TNGW1-rsh 1, 2 and 5 μg) also restored transfected miR-146a levels, peaking at the 2 μg level (Fig 2D). Units of 5 μg of GFP-TNRC6B or GFP-TNRC6C transfected by nucleofection into GW182-KD cells for cross-complementation analysis each restored the stability of transfected miR-146a (Fig 2D). The expression levels of TNGW1, TNRC6B and TNRC6C were monitored by qPCR (Fig 2E). Collectively, re-expression of GW182 and its paralogues TNRC6B and TNRC6C, as well as one of its middle repression domains, Δ12, could significantly restore the stability of transfected miRNA levels in GW182-KD cells. These data strongly support the hypothesis that GW182 regulates miRNA levels by binding to Ago2, and all three TNRC6 paralogues still seem functionally redundant. Note that no ‘rescue’ of representative endogenous miRNA levels (miR-16 and miR-132 examined) was detected in GW182-rsh, TNRC6B, TNRC6C or Δ12 complemented cells. Owing to the nature of the experimental design, the miRNA pools in stably cultured GW182-KD cells were most likely in steady-state, unless new miRNA transcription took place, adding back only GW182 that was not sufficient to revive endogenous miRNA levels.

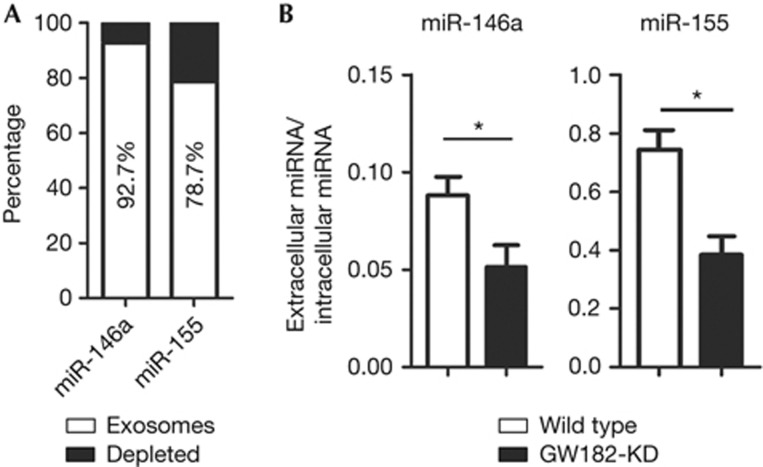

Reduced miRNA in GW182-KD cells not secreted

In GW182-KD cells, two possible pathways for the reduction of transfected miRNA are either secreted into extracellular space via exosomes or degraded intracellularly by cytoplasmic ribonucleases. Extracellular secreted miRNAs are protected by exosomes shed from almost all cell types and GW182 might be involved in this process [17]. Elevated miRNA secretion via exosomes can be taken up by recipient cells and demonstrated to silence reporter mRNA [18, 19]. However, it is disadvantageous to use a miRNA-mimic to evaluate miRNA secretion rates in GW182-KD cells owing to their persistence in the media and interference with secreted miRNA measurements. Thus, plasmids expressing miR-146a and miR-155 were transfected into wild-type cells to examine the export of these miRNAs. Consistent with a previous study [18], both miR-146a and miR-155 secretions by exosomes increased in the culture medium (supplementary Fig S3A online). To further confirm that miRNA was secreted via exosomes, an established differential ultracentrifugation protocol [20] was applied to transfected HEK293 cells media for exosomes purification. Two exosomes markers, CD63 and Rab5b [21], were used to confirm the successful purification (supplementary Fig S3B online). Upregulation of either miR-146a or miR-155 did not increase exosomal CD63 or Rab5b suggesting that the miRNA expression plasmids did not increase non-specific exosomal export. RNA was extracted from both the exosomes fraction and the supernatant depleted of exosomes derived from HEK293 cells. The majority of extracellular miRNA was copurified with exosomes (Fig 3A, miR-146a: 92.7 versus 7.3%; miR-155: 78.7 versus 21.3%). Both HEK293 and GW182-KD cells were transfected with miR-146a and miR-155 plasmids (Fig 3B). Relative fold change of both intracellular and extracellular miR-146a and miR-155 in GW182-KD and wild-type cells was determined and the ratios of extracellular to intracellular miRNA were calculated. In both transfections, GW182-KD cells showed a reduced ratio compared with wild type, demonstrating that the knockdown of GW182 decreased miRNA secretion via exosomes (Fig 3B). Note that the percentage of miRNA in the exosomal fraction was low (0.1% for miR-146a and 1% for miR-155) and this was consistent with data from a report evaluating the miRNA level in secretory microvesicles compared with their cellular content in monocytes [19].

Figure 3.

Knockdown of GW182 reduced miRNA secretion via exosomes. (A) A majority of secreted miR-146a and miR-155 in cell culture media was copurified with secretory exosomes. Total RNA was extracted from exosomes fraction and supernatant that was depleted of exosomes and analysed for the respective miRNA. (B) Knockdown of GW182 reduced miRNA secretions. Wild-type and GW182-KD cells were transfected with 2 or 5 μg of miR-146a and miR-155 expression plasmids. Both whole cells and culture media were harvested 24 h post transfection and subjected to total RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. *P<0.05. miRNA, microRNA.

Our data from cells with elevated endogenous miRNA confirmed the secretion of miRNA mainly via exosomes. However, our data using miRNA expression plasmids showed a relatively low ratio between extracellular and intracellular miRNA. Therefore, the results indicate that the miRNA secretion via exosomes is not a principal miRNA turnover channel. Reduced secretion in GW182-KD cells is consistent with the notion that GW182 might have a role in miRNA secretion via exosomes. However, GW182 was not detected in the exosomes fraction in our experiments so far. Further experiments are certainly required to elucidate whether there is a role for GW182, as well as other RISC components, in miRNA secretion. In summary, these results demonstrated that the reduced miRNA level in GW182-KD cells was an intracellular event and not owing to elevated secretion.

miRNase affecting miRNA stability

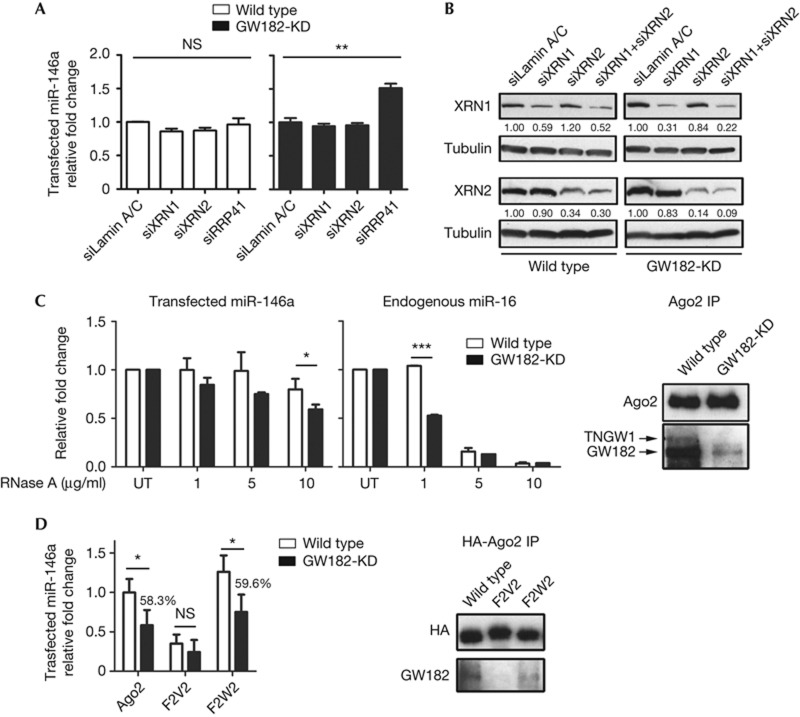

Previous studies identified different exoribonuclease responsible for miRNA degradation in Arabidopsis [22], Caenorhabditis elegans [23] and humans [4] described as ‘miRNase’ [24]. To identify the ribonuclease that has a role in GW182-KD cells, the effect on siRNA knockdown of the three principal ribonucleases (5′-3′ exoribonuclease XRN1, XRN2 and 3′-5′ exoribonuclease complex component RRP41) were examined in GW182-KD cells. First, siRNA for XRN1, XRN2 and RRP41 were transfected into wild-type and GW182-KD cells. After 48 h, miR-146a-mimic was transfected, and RNA was harvested after another 6 h of analysis. miR-146a levels remained unchanged in wild-type cells with all three individual knockdowns compared with levels in cells transfected with two controls (siLamin A/C, Fig 4A, and siGFP, not shown). Remarkably, the miR-146a level in GW182-KD cells transfected with siRRP41 was 51.4% higher than the same levels in siLamin A/C. These data implied that the miRNA was protected from degradation by the AGO-GW182 complex in wild-type cells and knockdown of these nucleases showed no effect. However, in GW182-KD cells, AGO-precipitated miRNAs were more sensitive to degradation, primarily by the RRP41-dependent 3′–5′-exoribonuclease complex; this is consistent with a previous report showing the role of this exoribonuclease as miRNase in mammalian cells [4]. Furthermore, mRNA qPCR analysis revealed only RRP41 mRNA, but not XRN1 or XRN2, was significantly elevated by 52.6% in GW182-KD cells (supplementary Fig S4A online). Interestingly, RRP41 mRNA levels did not reduce back to level in wild type but even increased when GW182 or Δ12 was added (supplementary Fig S4B online). This supports that adding back GW182 protected miRNA even when RRP41 levels increased. To rule out the potential false-negative effect caused by the functional redundancy of XRN1 and XRN2, double knockdown of XRN1 and XRN2 was also performed. The success of both single and double knockdown was confirmed by western blot (Fig 4B). Double knockdown of XRN1 and XRN2 did not significantly increase levels of transfected miRNA as observed in RRP41 knockdown (supplementary Fig S4C online). These data together strongly suggest that exosome complex have a primary role in miRNA degradation in GW182-KD cells.

Figure 4.

GW182 protected loaded miRNA decay by binding with AGO. (A) Exoribonuclease complex was responsible for miRNA degradation in GW182-KD cells. (B) Demonstration of the effective knockdown of XRN1 and XRN2 by western blot. (C) miRNA proved prone to degradation without GW182 in an Ago–RISC complex. Ago2 IP was performed in both wild-type and GW182-KD cells transfected with miR-146a-mimic and subjected to RNase A treatment. (D) AGO constructs showed decreased miRNA association in the absence of GW182. Ago2 wild type, F2V2 and F2W2 pull down were blotted by HA and GW182 antibodies. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. AGO, Argonaute; HA, haemagglutinin; IP, immunoprecipitation; miRNA, microRNA; NS, not significant.

Knocking down RRP41, in global transcription blocking study, results in significant and specific stabilization of certain miRNA [4]. Interestingly, the levels of GW182 and GW/P bodies fluctuated during the cell cycle, suggesting the delicate control of GW182 level in specific cellular states [25]. Although the changing levels of GW182 have not been examined in great detail, it is clear that the expression in GW182 is relatively low compared with other genes, such as Ago2. Thus a subtle change of GW182 might have a significant impact on miRNA stability.

GW182 protected AGO-precipitated miRNA from decay

To further confirm that GW182 protected AGO-bound miRNA from ribonuclease, immunoprecipitation (IP) of Ago2 was performed with monoclonal anti-Ago2 using lysates from wild-type and GW182-KD cells transfected with miR-146a-mimic for 6 h. Western blot analysis demonstrated the successful Ago2 pull down and efficient knockdown of both TNGW1 and GW182 in GW182-KD cells (Fig 4C). Both miR-146a and miR-16 precipitated from GW182-KD cell lysates showed increased sensitivity to RNase A treatments compared with those from wild-type lysates (Fig 4C). miR-146a level from GW182-KD cell lysate was 25.3% lower than that from wild type treated with 10 μg/ml RNase A. In contrast, compared with the wild type, the endogenous miR-16 level from GW182-KD lysate was reduced 49.5% using only 1 μg/ml RNase A. The difference in sensitivity was likely owing to the high number of transfected miR-146a compared with endogenous miR-16. However, both synthetic and endogenous miRNAs showed the same trend of higher sensitivity to RNase treatment in the absence of GW182. Thus, these data supported the role of GW182 in protecting miRNA by binding to Ago2.

To provide more evidence that the AGO–GW182 interaction is critical for AGO-bound miRNAs, a set of Ago2 constructs with differential GW182-binding abilities was employed. Two Ago2 constructs harbouring mutations on two conserved phenylalanines (Phe470 and Phe505) in the MID domain to valines (F2V2; poor miRNA loading and GW182 binding) or tryptophans (F2W2; retained miRNA loading and GW182 binding) were first studied for their mRNA cap-binding ability [26]. NHA-tagged Ago2 wild-type and mutated plasmids were transfected into wild-type and GW182-KD cells for 24 h. miR-146a-mimic was then transfected for an extra 6 h. Cell lysates were harvested for HA-Ago2 IP and associated RNAs were extracted for miRNA analysis. F2V2 showed significantly lower miRNA association from both wild-type and GW182-KD cells (Fig 4D) in agreement that this construct was defective in miRNA loading. Ago2 wild type and F2W2 showed comparable miRNA loading. Importantly, however, both Ago2- and F2W2-bound miRNA from GW182-KD cell lysate showed significantly lower levels compared with that from wild-type lysate (Fig 4D, 58.3 and 59,6%, respectively). No significant difference was observed for F2V2-bound miRNA from wild-type and GW182-KD cells. As previous studies suggested that AGO loading is dispensable to GW182 [27], our data suggested that GW182 protected loaded miRNAs only in Ago2 constructs with normal miRNA loading capacity. Western blot confirmed the precipitated Ago2 constructs and their putative interactions with endogenous GW182 (Fig 4D).

Previous studies have shown that AGO can bind to miRNA through its MID and PAZ domains [28]. Different Drosophila Ago1 mutations/deletions show that miRNA loading and AGO–GW182 interaction are uncoupled as two separate events [27, 29]. As the knockdown of GW182 did not affect miRNA loaded onto AGO, the reduced Ago2- and F2W2-bound miRNA from GW182-KD cell lysate IP might be owing to a lack of GW182 protection from endogenous miRNase. Thus, the absence of GW182 did not alter the miRNA loading onto AGO proteins or AGO association with miRNAs, but might make them more accessible and vulnerable to ribonuclease.

It remains possible that reduced miRNA levels in GW182-KD cells could be owing to completed digestion or 3′-end trimming. The Taqman qPCR assay employed could not distinguish the two possibilities owing to the assay design. Importantly, however, either possibilities support a model where GW182 interacts with Ago2 through its amino-terminal AGO-binding domain and protects the 3′ end of AGO-loaded miRNA from being degraded by a 3′–5′ exoribonuclease complex (supplementary Fig S5 online).

METHODS

Lentiviral constructs. ShRNA sequence against GW182/TNGW1 common region and negative control shGW182-mut are shown in Fig 1A. ShRNA sequence against TNRC6B and TNRC6C was selected from a previous report [15]. All shRNA sequences were fused with miR-30 stem-loop backbone structure and cloned into lentiviral vector pTYF-EF carrying GFP and puromycin-resistant markers. ShRNA expression was driven by Pol III-specific H1 promoter. HEK293 cells were transduced with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 20–40 in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. Forty-eight hours post transduction, cells were transferred to 2.5 μg/ml puromycin selection medium for culture.

Statistics. All data were from at least three independent experiments. PCR data are expressed as mean±s.e.m, and Student t-test was used for statistics.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health and the Andrew J. Semesco Foundation for financial support; Maurice Swanson, Alexander Ishov, Minoru Satoh and Hyun-Min Jung for stimulating discussions; Ranjan Batra for the advice with the Nucleofector device. We apologize for works not cited in this paper owing to limited space.

Author contributions: B.Y., L.-J.C. and E.K.L.C. designed the study. B.Y., L.B.L. and Y.-C.C. all designed and performed experiments. B.Y., L.-J.C. and E.K.L.C. analysed the experimental results. B.Y. and E.K.L.C. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Kai ZS, Pasquinelli AE (2010) MicroRNA assassins: factors that regulate the disappearance of miRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 5–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HW, Wentzel EA, Mendell JT (2007) A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science 315: 97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissland OS, Hong SJ, Bartel DP (2011) MicroRNA destabilization enables dynamic regulation of the miR-16 family in response to cell-cycle changes. Mol Cell 43: 993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bail S, Swerdel M, Liu H, Jiao X, Goff LA, Hart RP, Kiledjian M (2010) Differential regulation of microRNA stability. RNA 16: 1032–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs S, Haber DA (2007) Dual role for argonautes in microRNA processing and posttranscriptional regulation of microRNA expression. Cell 131: 1097–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J, Diederichs S (2011) Argonaute proteins regulate microRNA stability: increased microRNA abundance by Argonaute proteins is due to microRNA stabilization. RNA Biol 8: 1149–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Lian SL, Moser JJ, Fritzler ML, Fritzler MJ, Satoh M, Chan EK (2008) Identification of GW182 and its novel isoform TNGW1 as translational repressors in Ago2-mediated silencing. J Cell Sci 121: 4134–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JE, Huntzinger E, Fauser M, Izaurralde E (2011) GW182 proteins directly recruit cytoplasmic deadenylase complexes to miRNA targets. Mol Cell 44: 120–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekulaeva M, Mathys H, Zipprich JT, Attig J, Colic M, Parker R, Filipowicz W (2011) miRNA repression involves GW182-mediated recruitment of CCR4-NOT through conserved W-containing motifs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1218–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian MR et al. (2011) miRNA-mediated deadenylation is orchestrated by GW182 through two conserved motifs that interact with CCR4-NOT. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1211–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannath A, Wood MJ (2009) Localization of double-stranded small interfering RNA to cytoplasmic processing bodies is Ago2 dependent and results in up-regulation of GW182 and Argonaute-2. Mol Biol Cell 20: 521–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao B, Li S, Jung HM, Lian SL, Abadal GX, Han F, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK (2011) Divergent GW182 functional domains in the regulation of translational silencing. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 2534–2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillat D, Shiekhattar R (2009) Functional dissection of the human TNRC6 (GW182-related) family of proteins. Mol Cell Biol 29: 4144–4155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaretti D, Tournier I, Izaurralde E (2009) The C-terminal domains of human TNRC6A, TNRC6B, and TNRC6C silence bound transcripts independently of Argonaute proteins. RNA 15: 1059–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipprich JT, Bhattacharyya S, Mathys H, Filipowicz W (2009) Importance of the C-terminal domain of the human GW182 protein TNRC6C for translational repression. RNA 15: 781–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto K, Wakiyama M, Yokoyama S (2009) Mammalian GW182 contains multiple Argonaute-binding sites and functions in microRNA-mediated translational repression. RNA 15: 1078–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings DJ, Ciaudo C, Erhardt M, Voinnet O (2009) Multivesicular bodies associate with components of miRNA effector complexes and modulate miRNA activity. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1143–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T (2010) Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem 285: 17442–17452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y et al. (2010) Secreted monocytic miR-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol Cell 39: 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A (2006) Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter 3: Unit 3 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logozzi M et al. (2009) High levels of exosomes expressing CD63 and caveolin-1 in plasma of melanoma patients. PLoS One 4: e5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran V, Chen X (2008) Degradation of microRNAs by a family of exoribonucleases in Arabidopsis. Science 321: 1490–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Grosshans H (2009) Active turnover modulates mature microRNA activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 461: 546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans H, Chatterjee S (2010) MicroRNases and the regulated degradation of mature animal miRNAs. Adv Exp Med Biol 700: 140–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Jakymiw A, Wood MR, Eystathioy T, Rubin RL, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK (2004) GW182 is critical for the stability of GW bodies expressed during the cell cycle and cell proliferation. J Cell Sci 117: 5567–5578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriakidou M, Tan GS, Lamprinaki S, De Planell-Saguer M, Nelson PT, Mourelatos Z (2007) An mRNA m7G cap binding-like motif within human Ago2 represses translation. Cell 129: 1141–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Helms S, Fritzsch C, Fauser M, Izaurralde E (2009) A C-terminal silencing domain in GW182 is essential for miRNA function. RNA 15: 1067–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, Simard MJ (2008) Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Okada TN, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2009) Characterization of the miRNA-RISC loading complex and miRNA-RISC formed in the Drosophila miRNA pathway. RNA 15: 1282–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.