Abstract

Dense-core granules (DCGs) are organelles found in neuroendocrine cells and neurons that house, transport, and release a number of important peptides and proteins. In neurons, DCG cargo can include the secreted neuromodulatory proteins tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and/or brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which play a key role in modulating synaptic efficacy in the hippocampus. This function has spurred interest in DCGs that localize to synaptic contacts between hippocampal neurons, and several studies recently have established that DCGs localize to, and undergo regulated exocytosis from, postsynaptic sites. To complement this work, we have studied presynaptically-localized DCGs in hippocampal neurons, which are much more poorly understood than their postsynaptic analogs. Moreover, to enhance relevance, we visualized DCGs via fluorescence labeling of exogenous and endogenous tPA and BDNF. Using single-particle tracking, we determined trajectories of more than 150 presynaptically-localized DCGs. These trajectories reveal that mobility of DCGs in presynaptic boutons is highly hindered and that storage is long-lived. We also computed mean-squared displacement curves, which can be used to elucidate mechanisms of transport. Over shorter time windows, most curves are linear, demonstrating that DCG transport in boutons is driven predominantly by diffusion. The remaining curves plateau with time, consistent with motion constrained by a submicron-sized corral. These results have relevance to recent models of presynaptic organization and to recent hypotheses about DCG cargo function. The results also provide estimates for transit times to the presynaptic plasma membrane that are consistent with measured times for onset of neurotrophin release from synaptically-localized DCGs.

Keywords: Dense-core granule, presynaptic, transport, neuromodulator, hippocampus

INTRODUCTION

Dense-core granules (DCGs) are organelles found in neuroendocrine cells and neurons that store, transport, and regulate the release of, a number of important peptides and proteins. In neurons, DCG cargo often includes neuromodulatory proteins that play a key role in modulating synaptic efficacy in the hippocampus. One notable example is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which elicits long-lasting enhancement of neurotransmitter release from hippocampal neurons and which also augments synaptic area by stimulating the growth of dendritic spines (Lessmann et al., 1994, Levine et al., 1995, Li et al., 1998, Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2001, Tyler and Pozzo-Miller, 2003). Another notable example is tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which activates signaling pathways that influence synaptic plasticity and also can activate BDNF (Zhuo et al., 2000, Pang et al., 2004).

Despite their importance, DCGs that localize to synaptic contacts between hippocampal neurons are only partially understood; this is particularly true of presynaptically-localized DCGs. Distribution within synapses is fairly well understood; for example, electron micrographs reveal that a subset of pre- and postsynaptic sites in mammalian neurons is populated with DCGs that typically are not docked at the plasma membrane (Chieregatti and Meldolesi, 2005, Shakiryanova et al., 2005, Cifuentes et al., 2008). Moreover, unlike synaptic vesicles (SVs), synaptically-localized DCGs are not preferentially distributed at specialized sites, such as the active zone (Cifuentes et al., 2008).

Relative to distribution, transport of presynaptically-localized DCGs is poorly understood. In mammalian neurons, mobility results are limited to observation of visually immobile, axonal DCGs in hippocampal neurons that are proximal to postsynaptic density-95-rich regions (Matsuda et al., 2009). These may represent presynaptically-localized DCGs; however, the presynaptic identity of the organelles is not certain and the mobility data are very limited. More substantive data exist for micron-scale transport of DCGs in presynaptic boutons of the larval Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Shakiryanova et al., 2005). For this system, DCGs are immobile in resting boutons but become more mobile when boutons are stimulated with high KCl. Although intriguing, it is unclear if these results are applicable to submicron-scale transport of DCGs in the small presynaptic boutons of hippocampal neurons. Resolving this issue served as motivation for part of our work.

Additional motivation for our work comes from several recent studies that specifically implicate presynaptically-derived regulated secretory proteins in molecular processes and events at synapses. For example, presynaptic BDNF has been proposed to influence early phases of presynaptic long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus (Zakharenko et al., 2003, Lu et al., 2008) and also to influence postsynaptic LTP in the dorsal striatum (Jia et al., 2010). Presynaptic tPA has been proposed to play a role in (1) potentiation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated signaling, (2) activation of postsynaptic matrix metalloproteinase 9, and (3) homeostasis in the central nervous system (Benchenane et al., 2004, Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2004, Wilczynski et al., 2008). These studies clearly underscore the need to enhance understanding of DCGs and their cargo at presynaptic sites in mammalian neurons.

Motivated by both the paucity of data on, and the apparent biological significance of, presynaptic DCGs and their cargo, we have carried out high-resolution, experimental studies of the transport and storage of these organelles in hippocampal neurons, and we have complemented these experiments with associated theoretical analysis. Presynaptic boutons in hippocampal neurons are small and thus somewhat difficult to study; however, this attribute is balanced by a low DCG density, which allows mobility to be studied using high-resolution, single-particle tracking (SPT). To facilitate our transport and storage studies, we constructed DNAs encoding fluorescent chimeras of two particularly pertinent cargo proteins, tPA and BDNF, and we effectively expressed these chimeras in mature neurons. To date, we have used our chimeras, in conjunction with SPT and high-resolution fluorescence microscopy, to determine (1) rates and mechanisms of submicron transport of presynaptically-localized DCGs, (2) the time span of DCG storage at presynaptic sites, and (3) the probability that a bouton contains a DCG that houses tPA and/or BDNF. We find that, over shorter timescales, the majority of presynaptically-localized DCGs in hippocampal neurons undergo highly hindered submicron diffusion or submicron-scale corralled motion. Moreover, we find that DCGs are stored long term in boutons, where they house exogenous and endogenous tPA and BDNF with high probability. These data have relevance to recent models of presynaptic organization as well as aspects of DCG cargo function and release.

METHODS

Cell Culture

Hippocampal neurons from 18-day-old embryonic rats were cultured on 18-mm diameter round glass #1 cover slips, as described previously (Kaech and Banker, 2006).

Viral Infection and Electroporation

Expression vectors, including those encoding tPA-mCherry, BDNF-mCherry, enhanced blue fluorescent protein 2 (EBFP2), Venus, and 5×GFP (a protein consisting of five EGFPs connected by amino acid linkers) were constructed using standard subcloning techniques.

Two methods were used to introduce these (and similar) DNAs into hippocampal neurons. DNA encoding tPA and/or BDNF chimeras was introduced into mature (two to four weeks in vitro) hippocampal neurons using a replication defective herpes simplex virus (Ho, 1994). Cells then were imaged 16-24 hours after viral infection, mitigating concerns about long-term expression of exogenous neuromodulators. DNAs encoding other proteins were introduced into freshly isolated hippocampal neurons using electroporation, following Amaxa's instructions for its rat nucleofector kit (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). The neurons then were allowed to express the electroporated genes for times ranging from a few days to several weeks before viral infection and imaging.

Labeling of SV Clusters and Endogenous Neuromodulators

We used two different approaches to detect presynaptic vesicle clusters. Our first approach was used for fixed samples and involved immunostaining cells using a polyclonal rabbit antibody against the endogenous presynaptic protein synapsin-1 (Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), following a protocol similar to that described previously (Lochner et al., 2006). This primary antibody was labeled with one of two secondary antibodies, a goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 or a goat anti-rabbit Cascade Blue (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR).

Our second approach was used for living samples and involved electroporating cells with DNA encoding a green SV protein chimera, synaptophysin-EGFP. Moreover, if we wanted to confirm the presence of synapses in living neurons, we adopted a co-culture approach and electroporated synaptophysin-EGFP into one set of neurons and a soluble blue fluorescent protein, EBFP2, into a second set of neurons. EBFP2 and other soluble fluorescent proteins fill cells and delineate overall neuronal shape, including spines. A 50/50 mix of the two cell types was then plated onto cover slips. This approach yielded cover slips on which fluorescent cells had labeled SV clusters or labeled spines, but not both.

Immunostaining also was used to localize endogenous neuromodulators in hippocampal neurons. In the case of tPA, we affinity purified a goat anti-tPA antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA), following a protocol provided by Dr. David Wells (Yale University). In the case of BDNF, we used a sheep anti-BDNF antibody (Millipore) that our group and other groups have used previously to detect endogenous BDNF in hippocampal neurons (Swanwick et al., 2004, Lochner et al., 2008). These primary antibodies were labeled with donkey anti-goat Cy3 and donkey anti-sheep Alexa 594 antibodies, respectively (Invitrogen).

Imaging

Multi-color, conventional wide-field imaging of fixed neurons was used to study protein distribution throughout cells. Wide-field images of fixed cells were collected on an Olympus microscope (Olympus, Lake Success, NY) under the control of DeltaVision software (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA).

Two-color confocal and two or three-color conventional wide-field movies of living neurons were analyzed to study the trafficking and retention of chimera-containing DCGs at presynaptic sites. Confocal images of living neurons were generated using a multi-line krypton-argon laser, an acousto-optic tunable filter that facilitates rapid wavelength switching, and a custom-built microscope that includes a Yokogawa CSU-10 spinning disk confocal head and a perfect focus system that provides continuous Z-drift compensation during live-cell imaging. Conventional wide-field images of living neurons were collected using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 Microscopy System with a Dual Camera Module (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). This microscope also has continuous Z-drift compensation during live-cell imaging.

Methodology for mounting samples depended on whether the neurons were live or fixed. In the case of live imaging, cover slips containing hippocampal neurons were mounted in a chamber in Hanks-based imaging medium augmented with 10 mM HEPES and 0.6% glucose. The chamber was maintained at 34°C. For fixed imaging, cover slips containing neurons were mounted in elvanol and sealed to a slide with clear nail polish.

Methodology for acquiring images also depended on whether the neurons were live or fixed. Time-lapse images of shorter-term DCG transport in living cells were generated by taking images of the same focal plane every several hundred milliseconds. Time-lapse images of long-term DCG storage at presynaptic sites were generated by taking images of the same focal plane every 30 seconds for times that spanned a few hours. Most static images of DCG distribution in fixed cells were generated by optically sectioning cells in 0.2 μm focal increments (Hiraoka et al., 1991, Scalettar et al., 1996) and deblurring these images using a constrained iterative deconvolution algorithm (Scalettar et al., 1996) to improve image clarity.

Data Analysis

Localization of DCGs to presynaptic sites

To determine if DCGs containing tPA and/or BDNF localize presynaptically, we needed to visualize both presynaptic sites and any resident DCGs. To achieve the first end, we visualized SV clusters either by expressing a fluorescent SV protein (synaptophysin) chimera or by immunostaining against the presynaptic protein, synapsin-1. Moreover, to ensure that stained clusters were components of a synapse, we often simultaneously visualized postsynaptic dendritic spines labeled with 5×GFP, Venus, or EBFP2. SV clusters adjacent to a spine were classified as a synapse. To achieve the second end, DCGs containing red chimeras were assigned to the presynaptic side of a synapse if they colocalized with an SV cluster or were observed immediately adjacent to a cluster. Moreover, to avoid misclassifying a DCG as presynaptic due to resolution limits, we analyzed synapses in which the postsynaptic cell did not express a tPA or BDNF chimera, thereby ruling out a postsynaptic origin. We have previously used a similar method to assign DCGs to the postsynaptic side of hippocampal synapses (Lochner et al., 2006).

Co-localization of neuromodulators in individual DCGs at presynaptic sites

We quantified colocalization of tPA and BDNF chimeras in individual DCGs at presynaptic sites using a standard overlap assay that involved visually identifying presynaptic DCGs containing both tPA and BDNF chimeras, similar to past work (Lang et al., 1997, Lochner et al., 1998, Barg et al., 2002, Brigadski et al., 2005).

Tracking

DCGs were tracked in two dimensions (x,y) in background-subtracted movies using ImageJ. Tracking involved manually surrounding a DCG in a given frame with an appropriate (usually circular) shape and calculating the center of mass of the fluorescence distribution in the shape using ImageJ. Tracking was continued as long as the DCG could be identified unambiguously.

Classification of modes of motion

Lateral DCG motion was characterized quantitatively by computing the mean-squared displacement, <r2>, of DCGs as a function of time, t, and fitting to models that describe Brownian diffusion, anomalous diffusion, directed motion, and corralled diffusion as follows (Saxton and Jacobson, 1997, Abney et al., 1999):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Here, r is displacement, D is the diffusion coefficient, v is speed, <rc2> is corral size squared, and brackets < > denote averaging, which was performed as described previously (Abney et al., 1999). Of greatest relevance to our studies is the fact that Brownian diffusion produces a linear relationship between <r2> and t, whereas corralled diffusion produces a nonlinear relationship between <r2> and t that plateaus at long times. Here we report Brownian diffusion coefficients D, which were computed from fits to Eq. 1 as described previously (Abney et al., 1999). We also report corral sizes <rc>1/2 and short-term diffusion coefficients for corralled motion. The former were obtained from fits to Eq. 4 using the program Logger Pro 3 (Vernier, Beaverton, OR) and the latter from initial slopes of curves that fit Eq. 4.

In Eq. 4, corral size refers to the radius of the region in which an infinitesimally small (point) particle is free to diffuse. When applied to a DCG of finite radius, corral size can be interpreted either as the distance by which a corral radius exceeds a DCG radius or as the length of a tether the ties a DCG to a fixed point (Steyer and Almers, 1999, Jordan et al., 2005).

Consistent with past work, DCGs were classified as nearly immobile using two criteria (Burke et al., 1997, Lang et al., 2000, Silverman et al., 2005). Most commonly, we classified a DCG as nearly immobile if its associated Brownian diffusion coefficient was ≤ ~5 × 10-4 μm2/s. Less commonly, we classified a DCG as nearly immobile if its root mean square displacement, <r2>1/2, after several seconds was less than or equal to that of a nearly immobile Brownian diffusor.

Quantification of data statistics

Statistical data are reported as a mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), where the SEM was computed from data pooled from “n” different cells or axons. Statistical similarities and differences between data were analyzed using the Student's t-test function in Excel and are reported in terms of “p” values (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). For the t-test analysis, we adopted standard criteria and assumed that two data sets are statistically different if p < 0.05 and are statistically similar if p > 0.05.

RESULTS

DCGs Containing tPA and/or BDNF are Housed in a Substantial Subpopulation of Presynaptic Boutons

As a prelude to our studies of transport and storage, we determined the probability that a presynaptic bouton houses at least one DCG containing tPA and/or BDNF. Postsynaptic localization of DCGs containing tPA and/or BDNF is fairly well understood (Hartmann et al., 2001, Lochner et al., 2006, Lochner et al., 2008) but does not necessarily provide valid insight into presynaptic localization because DCGs can be asymmetrically distributed between axons and dendrites (Benson and Salton, 1996, Zhang et al., 2011). Thus, we evaluated presynaptic localization independently.

We assayed presynaptic localization by visualizing signals generated by chimeras and by visualizing signals generated by antibody-tagged native proteins and compared the results. We adopted both approaches because they have complementary strengths: chimeras produce robust signals with low background whereas antibody staining detects native protein.

Presynaptic localization of tPA is essentially undocumented in the literature, and thus we first assayed for the presence of tPA-mCherry in boutons. Fig. 1A-B show subregions of 21-DIV (days in vitro) hippocampal neurons that express either 5×GFP or tPA-mCherry and that are immunostained against synapsin-1. SV clusters apposed to dendritic spines reveal the presence of synapses. Moreover, tPA-mCherry-containing DCGs that colocalize with SV clusters apposed to spines reveal tPA that resides presynaptically. This presynaptic assignment can also credibly be applied to tPA-mCherry-containing DCGs that localize immediately adjacent to SV clusters because DCGs typically localize next to clusters in electron micrographs (Crivellato et al., 2005, Yakovleva et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

DCGs containing tPA or BDNF localize to presynaptic sites. Representative deblurred three-color fluorescence image (A) of dendritic processes (green), SV clusters (blue) present in axons of their synaptic partners, and tPA-containing DCGs (red). The boxed region in (A) is enlarged in (B), and several tPA-containing DCGs that colocalize with presynaptic sites are identified with arrowheads. Analogous images (C-F) from hippocampal neurons expressing BDNF-mCherry. BDNF-containing DCGs that colocalize with presynaptic sites are identified with arrowheads. The lowest arrowhead in (C) points to a DCG localized to a shaft synapse. Scale Bar = 10 μm for A. Scale Bar = 2 μm for B-F.

Resolution limitations on light microscopy can complicate classifying a DCG as pre- or postsynaptic. Consequently, to strengthen the conclusion that a DCG was presynaptic, we analyzed only synapses involving postsynaptic cells that did not express chimeric DCG cargo. Thus, the images in Fig. 1 were derived from postsynaptic cells that lacked somatic fluorescence.

BDNF has been better studied than tPA in many neuronal subdomains, including putative presynaptic sites of hippocampal neurons (Swanwick et al., 2004, Matsuda et al., 2009). Nevertheless, we independently conducted studies of presynaptically-localized BDNF to generate data that met the same relatively stringent requirements that we imposed on our data for tPA. Fig. 1C-F show subregions of 21-DIV hippocampal neurons that express either Venus or BDNF-mCherry and that are immunostained against synapsin-1. BDNF-mCherry-containing DCGs also colocalize with, and localize near, SV clusters apposed to spines, revealing BDNF that resides presynaptically.

Fig. 1C (lowest arrowhead) further reveals that BDNF colocalizes with SV clusters apposed to dendritic shafts. We also have observed tPA localize similarly. These results suggest that tPA and BDNF localize to shaft synapses, which can be precursors to spine synapses. This observation raises the possibility that these two neuromodulators are recruited to sites of synaptic formation before a spine has developed.

Most significantly, we quantified our presynaptic localization results and computed localization probabilities. Quantification revealed that 51 ± 5% of presynaptic sites contain at least one chimera-labeled DCG. Moreover, tPA is present in 87 ± 3% of presynaptic DCGs, and thus the probability of finding a tPA-containing DCG in a bouton is 0.44 ± 0.04 (n = 9 cells, 192 SV clusters, 126 DCGs). The analogous result for BDNF is 0.42 ± 0.04.

We also assayed for copackaging of tPA and BDNF at presynaptic sites. Copackaging has potential biological relevance because it may lead to corelease of tPA and BDNF in response to high-frequency electrical stimuli, and it also may facilitate putative interactions between tPA and BDNF that elicit changes in synaptic efficacy (Pang et al., 2004, Nagappan et al., 2009).

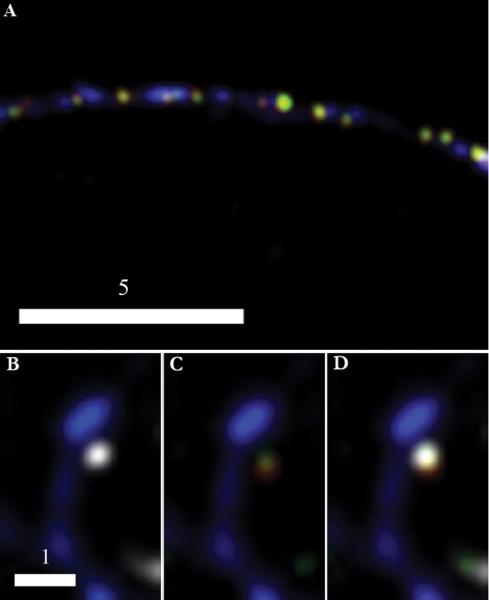

We determined if tPA and BDNF are copackaged in boutons using two approaches. Fig. 2A is a representative image obtained using the simpler (three-color) imaging approach; the image shows DCGs containing both tPA-EYFP and BDNF-mCherry that overlap with SV clusters tagged with a secondary antibody conjugated to Cascade Blue. Fig. 2B-D show complementary versions of a representative image obtained using the more stringent and challenging (four-color) imaging approach. Similar to the image in panel A, a DCG containing tPA-EYFP and BDNF-mCherry colocalizes with an SV cluster immunostained with a secondary antibody tagged with Alexa Fluor 647, which emits in the far red. In addition, these overlapping structures are apposed to a spine filled with EBFP2.

Fig. 2.

BDNF-mCherry and tPA-EYFP are copackaged in presynaptic DCGs. Deblurred fluorescence image (A) of an axon from a 14-DIV hippocampal neuron showing colocalization of tPA-EYFP (green) and BDNF-mCherry (red) within DCGs that, in turn, colocalize with SV clusters (blue) immunostained against synapsin-1 using a Cascade Blue secondary. DCGs containing tPA and BDNF appear yellow. Images (B-D) of a synapse between fixed 21-DIV hippocampal neurons. DCG proteins are tagged as in (A) and the SV cluster (white) again is immunostained against synapsin-1, but with a secondary, Alexa Fluor 647, that emits in the far red. The spine (blue) is labeled using an EBFP2 fill. For clarity, the spine is shown first with the SV cluster (B) and then with the two overlapping DCG proteins (C). All stained components are shown together in (D). Scale Bar = 5 μm for A. Scale Bar = 1 μm for B-D.

We quantified data obtained from these (and similar) images and found that tPA and BDNF are copackaged in 69 ± 5% of presynaptic sites that contain a labeled DCG (n = 9 cells, 192 SV clusters, 126 DCGs).

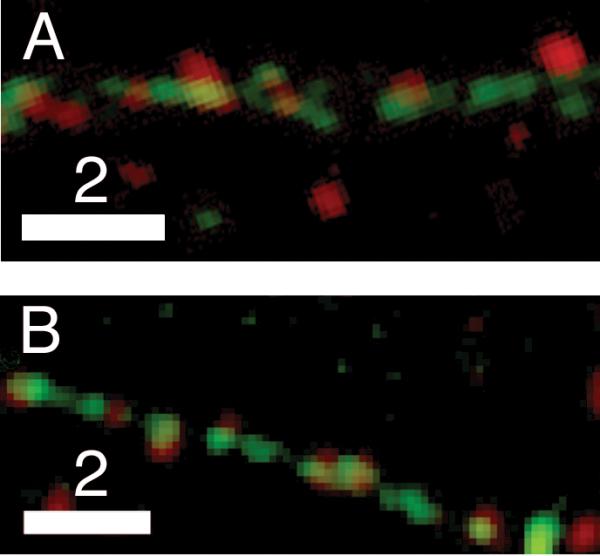

Unlike transport, localization of neuromodulators to presynaptic sites also can be studied by using immunofluorescence to visualize the distribution of endogenous proteins in fixed cells. When possible, we also used immunofluorescence to map distribution, because the endogenous neuromodulators are our real interest. Fig. 3 shows representative examples of our immunofluorescence images, and the associated legend contains a discussion of our quantitative results for endogenous localization probabilities, which are 0.41 ± 0.04 (BDNF) and 0.39 ± 0.07 (tPA). The key result in the legend is that endogenous tPA and BDNF localize to presynaptic sites with frequencies that are statistically indistinguishable from those of their chimeric analogs.

Fig. 3.

Endogenous neuromodulators localize to presynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons. Dual-color image showing that puncta stained by an antibody against endogenous BDNF (red) (A) are present in presynaptic clusters (green) along axons of fixed 7-DIV hippocampal neurons expressing synaptophysin-EGFP. Analogous image of endogenous tPA (red) (B) in fixed 10-DIV hippocampal neurons expressing synaptophysin-EGFP (green). Quantification of data obtained from these types of images revealed that the probability that a bouton houses a DCG containing endogenous BDNF is 0.41 ± 0.04 (n = 171 SV clusters, 65 DCGs). The analogous result for endogenous tPA is 0.39 ± 0.07 (n = 382 SV clusters, 171 DCGs). Each of these endogenous localization probabilities is statistically indistinguishable from its analogous exogenous localization probability. Specifically, results from the Student's t-test yielded large p values for both BDNF (p = 0.40 > 0.05) and tPA (p = 0.49 > 0.05). Scale Bar = 2 μm for A and B.

In past work, several groups (including ours) also have used immunostaining to compare levels of expression of endogenous and exogenous neuromodulators. These analyses reveal that, on average, exogenous neuromodulators are expressed at levels that are ~2–5× endogenous levels (Kolarow et al., 2007, Lochner et al., 2008, Matsuda et al., 2009) and that the density of DCGs containing exogenous neuromodulators is less than twice that of DCGs containing endogenous neuromodulators. We tend to find exogenous protein chimeras expressed at the lower end of this range, perhaps because we image neurons quickly after viral delivery of DNAs encoding the chimeras. The important conclusion from these studies is that overexpression of chimeras is modest and thus is unlikely to introduce major artifacts into our results, such as extensive labeling of DCGs that do not contain endogenous neuromodulators.

Presynaptic DCGs Undergo Hindered Submicron Diffusion and Corralled Motion

After demonstrating that DCGs containing tPA and/or BDNF are present in a significant fraction of presynaptic sites, we conducted a dynamic analysis to determine rates and mechanisms of DCG transport and if DCG localization at presynaptic sites is long or short lived. We generated two types of data to address these issues in resting neurons. First, we produced two-color movies of neurons expressing synaptophysin-EGFP and either BDNF-mCherry or tPA-mCherry. Two representative movies are provided as supplemental data (see Supplemental movies 1–2). Second, we produced three-color movies of neurons expressing synaptophysin-EGFP and BDNF-mCherry or tPA-mCherry apposed to neurons expressing EBFP2. Using these movies, we tracked DCGs at SV clusters stained with synaptophysin-EGFP and determined transport mechanisms for DCGs that were localized to the cluster and not simply transiting along the axon (n = 5 axons, 158 DCGs).

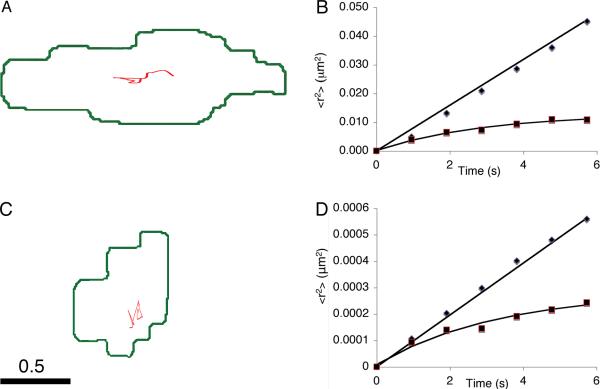

Over timescales of tens of seconds, presynaptic DCGs typically generate trajectories that conform to the Brownian diffusion model. Fig. 4A-B show a representative trajectory and plots of <r2> versus t obtained from DCGs at presynaptic sites. One of the plots is linear, demonstrating that the transport of the associated DCG was Brownian diffusion. Quantification showed that this is the dominant shorter-term transport mode; 74 ± 11% of presynaptic DCGs undergo Brownian diffusion. Moreover, this diffusion is slow. For example, the linear data in Fig. 4B yielded a value for D, 2.0 × 10-2 μm2/s, that is ~0.4% that of a sphere of diameter 100 nm (comparable to a neuronal DCG) in water. In the Discussion, we connect hindrance of mobility, and the existence of corrals, to the ultrastructural organization of presynaptic termini (Siksou et al., 2011) and crowding in the cytoplasm (Luby-Phelps et al., 1987).

Fig. 4.

DCGs at presynaptic sites undergo very slow Brownian diffusion and corralled motion. Trajectory (A) of a relatively mobile presynaptic DCG and associated plots (B) of <r2> versus t deduced from two relatively mobile presynaptic DCGs. One plot (◆) is linear, consistent with Brownian diffusion, and one (■) is nonlinear, consistent with corralled motion. Trajectory (C) and associated plots (D) of <r2> versus t deduced from nearly immobile presynaptic DCGs. In panels B and D, the Brownian data were divided by 10 to facilitate displaying two data sets on the same graph. In panels A and C, DCGs are represented by points localized at their center of mass and thus do not extend over a representative fraction of the cluster. Scale bar = 0.5 μm.

We also observed trajectories for presynaptic DCGs that were consistent with corralled diffusion. For example, Fig. 4B also shows an <r2> versus t plot that is nonlinear and was fit by the corralled diffusion model with a corral size = 113 nm. Quantification showed that 21 ± 9% of presynaptic DCGs undergo corralled motion.

Although hindered, the motion analyzed in Fig. 4B is more rapid and extensive than that of most presynaptic DCGs. Fig. 4C-D show a representative trajectory and plots of <r2> versus t obtained from very hindered presynaptic DCGs. Again, one plot is linear, demonstrating that the transport was Brownian diffusion, but the associated D is ~1.0% that of the Brownian diffusor in Fig. 4B. The other plot is nonlinear and fits the corralled motion model, but the associated corral size is ~16% that of the corralled DCG in Fig. 4B. Quantification showed that the average short-term Brownian diffusion coefficient is 4.9 ± 0.6 × 10-4 μm2/s and that the average radius of a corral that confines shorter term transport is 44 ± 7 nm. Moreover, corral radii range from ~15 – 113 nm. In the Discussion, we compare these data to analogous results for SVs.

As a control, we also quantified transport of DCGs in processes and found that the very slowly mobile fraction is 7 ± 2% (n = 4 axons, 356 DCGs), similar to past work (Lochner et al., 2006). We similarly tracked SV clusters in living neurons and verified, as reported in the literature (Jordan et al., 2005), that boutons are very immobile (D ≤ 10-5 μm2/s), and we verified that instrument drift did not affect our results. In light of these controls, we conclude that presynaptically-localized DCGs in hippocampal neurons are very slowly mobile on the submicron distance scale and over time windows that span tens of seconds.

To this point, our analysis of localization and transport has assumed implicitly that puncta represent single DCGs. Given the resolution limitations on conventional wide-field and confocal fluorescence microscopy, it is possible that some puncta instead represent clusters containing a few DCGs. However, we do not think that clustering is the norm, or that it would significantly impact most of our results, for reasons given in the Discussion.

Storage of DCGs at Presynaptic Sites is Long-lived

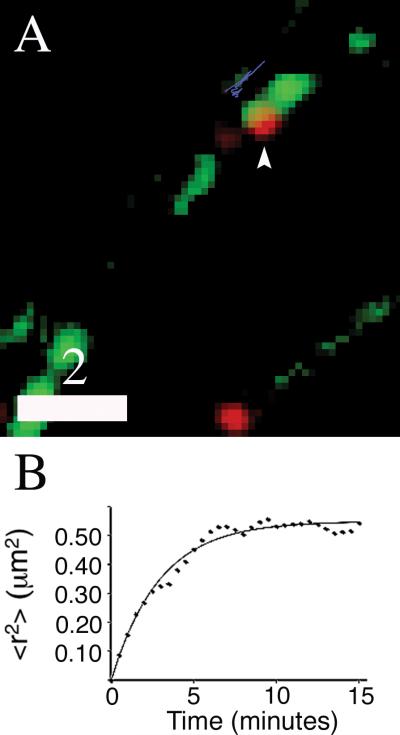

In the Discussion, we use our short-term diffusion data and diffusion theory to predict that DCGs can escape from presynaptic boutons in ~10 minutes, suggesting that DCG retention at presynaptic sites might not be very long-lived. In light of this possibility, we experimentally monitored long-term colocalization of DCGs with presynaptic markers in living neurons. To this end, we imaged resting hippocampal neurons every 30 seconds for a few hours and determined if DCGs remained colocalized with presynaptic markers over this long time window. At the end of long-term imaging, we assayed neuron viability by collecting a short movie and determining if DCGs continued to undergo fast transport along processes.

Long-term imaging revealed long-lived retention of DCGs at presynaptic sites. Fig. 5A shows a representative image of a presynaptically-localized DCG that remained in a relatively large bouton (cluster dimensions ~1.7 μm × 0.8 μm) throughout a 90 minute imaging experiment, and Fig. 5B shows an associated <r2> versus t plot obtained by tracking this DCG. For small t, the mean-squared displacement plot is linear, implying that transport is well described by Brownian diffusion. The associated short-term Brownian diffusion coefficient was extracted from the initial slope of the plot and is ~6 × 10-4 μm2/s. In contrast, for t > ~5 minutes, the plot begins to deviate from linearity significantly and to approach a plateau. This suggests that, after several minutes, <r2> is large enough for the DCG to begin to “feel” the presence of a confining corral. Curve fitting yielded a large corral radius, ~0.75 μm, for this longer-term motion. The associated corral diameter, 1.5 μm, is comparable to the cluster length, suggesting DCG confinement by the edges of the bouton instead of some small substructure.

Fig. 5.

DCGs remain localized at presynaptic sites for a few hours. Two-color image (A) of 17-DIV hippocampal neurons expressing BDNF-mCherry (red) and synaptophysin-EGFP (green). A DCG that colocalized with an SV cluster for at least 90 minutes is identified with an arrowhead, and the trajectory of the DCG for a 15-minute time window is shown in blue, slightly offset from the SV cluster. Plot of <r2> versus t (B) obtained from tracking the DCG in panel A for 15 minutes. The line in panel B is a fit to the corralled diffusion model. Scale bar = 2.0 μm. Supplemental Movie 1. Visualization of DCG transport in the soma, along processes, and in boutons of mature neurons. Deblurred time-lapse movie showing transport of DCGs in a 17-DIV hippocampal neuron expressing synaptophysin-EGFP (green) and BDNF-mCherry (red).

DISCUSSION

The experiments described here were directed at determining (1) rates and mechanisms of submicron transport of presynaptically-localized DCGs, (2) the time span of DCG storage at presynaptic sites, and (3) the frequency of tPA and BDNF storage within presynaptically-localized DCGs. Here we discuss our results and their implications beginning, as we did in Results, with localization.

Attributes and Significance of Presynaptically-localized DCGs and their Cargo

Previous studies have demonstrated that tPA and BDNF are present in, and undergo regulated secretion from, DCGs that localize to postsynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons (Hartmann et al., 2001, Kojima et al., 2001, Brigadski et al., 2005, Lochner et al., 2006, Kolarow et al., 2007). In contrast, evidence bearing on analogous attributes of presynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons is comparatively limited. Intriguingly, however, two relatively recent studies suggest that presynaptic BDNF is relevant to LTP (Zakharenko et al., 2003, Jia et al., 2010). In addition, an increasing body of data suggests that presynaptically-localized DCGs house proteins that become imbalanced, and thus impair synaptic function, in brains afflicted with neurological disorders, particularly Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia (Willis et al., 2011). These possibilities underscore the potential importance of presynaptic DCGs and their cargo, and the link to LTP, in particular, motivated us to launch an avenue of research aimed at elucidating presynaptic localization of tPA and BDNF as well as attributes of their carrier organelles.

Our double and triple-label studies of the distribution of endogenous and exogenous tPA demonstrate – for the first time – that tPA-containing DCGs are present in ~44% of presynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons. BDNF similarly localizes to ~42% of these sites. These relatively high localization probabilities are consistent with the hypothesis that presynaptically-derived tPA and BDNF play a significant role in molecular events and processes at synapses, including those underlying LTP (Zakharenko et al., 2003, Benchenane et al., 2004, Fernandez-Monreal et al., 2004, Wilczynski et al., 2008).

Our triple- and quadruple-label experiments further demonstrate that chimeric tPA and BDNF are copackaged in ~69% of presynaptic sites that contain a labeled DCG. This extensive copackaging could facilitate tPA-mediated activation of BDNF (Pang et al., 2004), and it further suggests that tPA and BDNF undergo corelease, consistent with recent Western data demonstrating corelease in response to high-frequency electrical stimuli (Nagappan et al., 2009).

In contrast, at first glance, extensive copackaging may seem inconsistent with recent data demonstrating release of BDNF alone in response to low-frequency electrical stimuli (Nagappan et al., 2009). One possible explanation is that lower frequencies induce exocytosis of DCGs containing BDNF (but not tPA), and this leads to the release of BDNF alone. In contrast, higher frequencies induce exocytosis of DCGs containing tPA and BDNF that leads to the release of both proteins. In support of this possibility, distinct subpopulations of DCGs in PC12 cells are preferentially triggered to undergo exocytosis by different types of cation-mediated stimulation, depending on the type of synaptotagmin harbored by the DCG (Zhang et al., 2011); however, it is unclear if differential recruitment also occurs in response to different electrical stimuli and/or in neurons.

Another possible explanation has somewhat stronger experimental backing. In particular, relatively recent data show that, at lower frequencies, exocytosis of neuronal SVs and neuroendocrine DCGs occurs preferentially via an “incomplete fusion” mechanism (Wu, 2004, Fulop et al., 2005, Elhamdani et al., 2006, Scalettar, 2006). In this mechanism, the vesicle does not flatten completely into the plasma membrane; instead it establishes continuity with the extracellular space via a fusion pore, while maintaining some of its integrity and shape. Significantly, incomplete fusion leads to different rates and extents of release of distinct cargo proteins from the same DCG, based in part on size (Holroyd et al., 2002, Taraska et al., 2003, Fulop et al., 2005).

Given the attributes of incomplete and full fusion exocytosis and the frequency-dependence of tPA release, it seems plausible that incomplete fusion of DCGs is induced preferentially at hippocampal synapses by low-frequency stimuli, similar to SVs. Incomplete fusion, in turn, leads to extensive secretion of BDNF and minimal secretion of tPA, consistent with their disparity in size. In contrast, complete fusion is induced preferentially by high-frequency stimuli and leads to full release of cargo (Fulop et al., 2005).

Attributes and Significance of the Transport of Presynaptically-localized DCGs

We studied the trafficking of DCGs at presynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons for two primary reasons. First, trafficking mechanisms both influence and shed light on exocytosis. Second, recent qualitative transport data suggest that release of BDNF from axons occurs predominantly from DCGs that are relatively immobile, motivating interest in determining the mobility of presynaptically-localized DCGs (Matsuda et al., 2009).

To facilitate comparison with other data, we adopted a standard low mobility criterion and classified organelles diffusing at rates corresponding to D ≤ ~5 × 10-4 μm2/s as nearly immobile (Sako and Kusumi, 1994, Burke et al., 1997, Lang et al., 2000, Silverman et al., 2005). Based on this criterion, 77 ± 5% of the DCGs that colocalize with SV clusters in hippocampal neurons are nearly immobile. This result, in conjunction with the axonal BDNF release data (Matsuda et al., 2009), suggests that most presynaptic DCGs are in a state that is conducive to exocytosis.

What is the molecular source of the very hindered diffusion and corralled motion of presynaptic DCGs? One plausible candidate is the dense network of filaments identified in recent fast freezing and/or electron tomographic studies of the ultrastructure of presynaptic boutons in hippocampal neurons (reviewed in (Siksou et al., 2011)). This network contains actin filaments, as well as other constituents that have yet to be identified (reviewed in (Dillon and Goda, 2005)). The filamentous network could significantly hinder DCGs if it tethers them transiently (Steyer and Almers, 1999, Johns et al., 2001). Consistent with this possibility, myosin Va has been proposed to tether DCGs dynamically to the actin cytoskeleton (Rudolf et al., 2011). The network also could retard (or corral) DCGs if it acts as a major barrier to their movement (Luby-Phelps et al., 1987, Kao et al., 1993, Dix and Verkman, 2008). Consistent with this second possibility, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) data reveal that diffusion of nonbinding tracer particles in cell cytoplasm is hindered increasingly as tracer radius increases (Luby-Phelps et al., 1987). In addition, these data, like ours, indicate that diffusion in crowded cellular environments is very impeded for Brownian particles, like neuronal DCGs, with radii > ~50 nm. Finally, filaments, in conjunction with motors, could facilitate active transport of DCGs (reviewed in (Bridgman, 2004)), but our data suggest that this is rare in boutons of hippocampal neurons.

DCGs are Stored Long-term in Boutons

Our short-term transport data reveal that presynaptically-localized DCGs diffuse very slowly. In light of this, it might be tempting to assume that DCGs necessarily remain in boutons for long periods of time. However, our short-term diffusion coefficients do not guarantee long-term retention because hippocampal boutons are very small. To illustrate this, we invoke two expressions for the mean escape time of a Brownian particle. The first, t ≈ V/4Da, is an expression for the mean time that it takes the particle to escape from a volume V via an aperture of radius a (Berezhkovskii et al., 2002). This expression has been used previously to compute mean escape times from dendritic spines (Schuss et al., 2007), and we use it to estimate escape times from terminal boutons. The second, t ≈ 4R3/6Da, is an expression for the mean escape time from a sphere of radius R containing two apertures (Vazquez and Dagdug, 2011), and we use it to estimate escape times from en passant boutons, which possess two apertures. For excitatory hippocampal boutons in culture, V ~0.13 μm3 (which implies R ~0.3 μm), and the aperture is an axonal shaft with a ~0.085 μm (Shepherd and Harris, 1998). Using these values, and the mean diffusion coefficient presented in Results, D ~5 × 10-4 μm2/s, we find t ~13 minutes and ~7 minutes, respectively. A time on the order of minutes also is obtained from the expression for mean-squared displacement, which provides an estimate of the time required for a Brownian particle to explore a region of space (Berg, 1983).

One potential problem with this method of estimate is that motion over longer timescales can diverge from predictions based on short-term behavior, especially in spatially constrained domains (reviewed in (Saxton and Jacobson, 1997)). For example, compartmentalization in biological membranes leads to an apparent slowing of lipid motion with increasing observation time (Sako and Kusumi, 1994, Murase et al., 2004). In addition, mean escape models assume that particles are points, and this also could lead to discrepancies between theory and experiment. In light of these possibilities, we studied long-term storage experimentally and found that DCGs in resting hippocampal neurons remain localized at presynaptic sites for time windows of a few hours, at a minimum. Long-term retention of DCGs in boutons is consistent with the critical synaptic functions of their neuromodulatory cargo.

Implications for DCG Exocytosis

Our submicron transport data also can be used to estimate the mean time required for a presynaptically-localized DCG to traverse the distance to the surface of a bouton. To calculate this mean transit time, we invoked an expression for the mean time that a Brownian particle takes to collide with a wall on the surface of a limiting sphere of radius R. This expression is t = R2/15D (Levskaya et al., 2009), and we use it here to predict the mean time required for a presynaptically-localized DCG to collide with the plasma membrane of a “spherical” bouton. Inserting the values given in the previous section yields t ~12 s.

There are two important attributes of this prediction. First, it is in approximate agreement with the ~10-30 s delay in onset of neurotrophin release from postsynaptically-localized DCGs (Brigadski et al., 2005), which, notably, are constrained within a volume comparable to that of a bouton (Papa et al., 1995, Schikorski and Stevens, 1997, Boyer et al., 1998). Second, it is short relative to the timescale of release of DCG cargo proteins from hippocampal neurons, which is many minutes (Hartmann et al., 2001, Brigadski et al., 2005, Lochner et al., 2006). This latter attribute suggests that transport to the plasma membrane does not limit rates of protein release from presynaptically-localized DCGs. Consistently, interactions between protein cargo and the DCG core have been found to have a dominant effect on rates of protein release from synaptically-localized DCGs in hippocampal and cortical neurons (Brigadski et al., 2005, de Wit et al., 2009).

The Origins of Puncta

In most studies of fluorescently labeled DCGs, puncta are assumed to represent individual organelles (see e.g., (Silverman et al., 2005, Kolarow et al., 2007, Kwinter et al., 2009)). Given the resolution limitations on fluorescence microscopy, it is possible that some puncta instead represent clusters containing a few DCGs. We do not think that clustering is the norm for the following reasons. First, if clustering were the norm, we would expect to observe some moving puncta split into subpuncta, unless all of the DCGs in clusters are extremely tightly bound. We also would expect to see the reverse (fusion) process. However, we have never observed splitting or fusion. A somewhat related argument against clustering (repetitive all-or-none movement of DCGs) was advanced by the authors of a study of postsynaptic secretion of BDNF-EGFP from hippocampal neurons (Kolarow et al., 2007). Second, if clustering were the norm, we would expect it to show up in electron micrographs. However, this is not the case (Crivellato et al., 2005, Yakovleva et al., 2006).

Importantly, clustering also would not impact our most significant results, even if it were the norm. For example, it would not negate localization of DCGs containing tPA or BDNF to presynaptic sites, nor is it likely to have much impact on our transport results because spheres cluster into structures with effective radii that do not differ markedly from that of a single sphere (Hoffmann et al., 2009). Thus, translational diffusion coefficients should not be markedly altered by clustering.

Comparison with Past Dynamic Studies of Presynaptically-localized DCGs

To our knowledge, we have conducted the first thorough study of DCG transport at presynaptic sites in hippocampal (and mammalian) neurons. We also are aware of only one other thorough study of DCG transport at presynaptic sites (Shakiryanova et al., 2005). This is a FRAP study of the micron-scale motion of DCGs containing fluorescent chimeras in larval Drosophila NMJs, which are large and enriched in DCGs. In this work, spots with a diameter of ~1 μm were bleached in resting boutons of Drosophila and there was little recovery of fluorescence in 15 minutes, which is indicative of significant hindrance of DCG motion over micron-sized distance scales. SPT similarly shows that DCGs in resting hippocampal neurons remain spatially constrained within entire boutons for ~2 hours (at a minimum).

SPT has markedly better spatial resolution than FRAP (Saxton and Jacobson, 1997), and thus our studies provide a novel view of transport of presynaptically-localized DCGs over submicron distances. This advance is key for hippocampal neurons in which submicron-scale motion must precede exocytosis from boutons. In boutons of hippocampal neurons, DCGs are mobile, but diffuse very slowly, over this shorter distance scale. At present, it is unclear whether DCGs in boutons of Drosophila are similarly mobile over submicron distances.

Comparison with SV Localization and Mobility in Boutons

Motivated by an interest in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying SV exocytosis and recycling, SV dynamics in boutons of hippocampal neurons has been fairly extensively studied using techniques ranging from FRAP to SPT. Here we compare our results for DCGs to those obtained for undocked SVs.

DCGs and SVs in boutons exhibit similar dynamics but dramatically different localization. Specifically, it is well established that transport of SVs in resting hippocampal synapses, like transport of DCGs, is very highly hindered (Jordan et al., 2005, Lemke and Klingauf, 2005). Moreover, SVs and presynaptically-localized DCGs are constrained by corrals of similar radii. For example, over a time window of tens of seconds, SVs are constrained by corrals with total radius (<rc>1/2 + organelle radius) lying in the range from ~75 – 125 nm (Jordan et al., 2005). The analogous result for presynaptically-localized DCGs is ~65 – 163 nm. The similarity in these ranges suggests that corrals reflect real physical attributes of boutons.

The primary difference between SV and DCG transport in boutons is that SV transport over shorter time windows is predominantly corralled, whereas DCG transport is not. These organelles also differ significantly in their distribution. For example, it is well established that hundreds of SVs can be present at a synapse (Harris and Sultan, 1995) and that SVs localize near active zones (Burns and Augustine, 1995). In contrast, our images, and electron micrographs (Drake et al., 1994, Crivellato et al., 2005, Yakovleva et al., 2006, Cifuentes et al., 2008), typically show only one or two DCGs on either side of a synapse and that DCGs localize throughout boutons (Pickel et al., 1995).

CONCLUSIONS

We have studied the transport, storage, and cargo of presynaptically-localized DCGs in hippocampal neurons. Our results demonstrate very slow, submicron-scale mobility of presynaptic DCGs in hippocampal neurons. Our results also demonstrate long-term storage of DCGs and their cargo, notably both tPA and BDNF, in boutons of hippocampal neurons. These results link transport to several important attributes of synaptically-localized DCGs, including delayed onset of protein release and long-term retention of neuromodulatory cargo.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Movie 2. Visualization of DCG transport within SV clusters. Deblurred time-lapse images showing the slow movement of several BDNF-mCherry-containing DCGs (red) localized at presynaptic vesicle clusters labeled with synaptophysin-EGFP (green). Also shown is the rapid transport of several DCGs that do not localize presynaptically.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Gary Banker, Dr. Stephanie Kaech Petrie, Barbara Smoody, and Julie Luisi Harp of Oregon Health & Science University for advice, some constructs, and extensive support with the culture of hippocampal neurons. We also thank Dr. James Abney for a critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 2 R15 GM061539-02 (to B.A.S.), 3 R15 NS40425-03 (to J.E.L.), and MH 66179 (to Dr. Gary Banker of Oregon Health & Science University).

REFERENCES

- Abney JR, Meliza CD, Cutler B, Kingma M, Lochner JE, Scalettar BA. Real-time imaging of the dynamics of secretory granules in growth cones. Biophys J. 1999;77:2887–2895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barg S, Olofsson CS, Schriever-Abeln J, Wendt A, Gebre-Medhin S, Renstrom E, Rorsman P. Delay between fusion pore opening and peptide release from large dense-core vesicles in neuroendocrine cells. Neuron. 2002;33:287–299. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchenane K, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Fernandez-Monreal M, Touzani O, Vivien D. Equivocal roles of tissue-type plasminogen activator in stroke-induced injury. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DL, Salton SR. Expression and polarization of VGF in developing hippocampal neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;96:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezhkovskii AM, Grigoriev IV, Makhnovskii YA, Zitserman VY. Kinetics of escape through a small hole. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2002;116:9574–9577. [Google Scholar]

- Berg H. Random Walks in Biology. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer C, Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Comparison of hippocampal dendritic spines in culture and in brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5294–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05294.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman PC. Myosin-dependent transport in neurons. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:164–174. doi: 10.1002/neu.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigadski T, Hartmann M, Lessmann V. Differential vesicular targeting and time course of synaptic secretion of the mammalian neurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7601–7614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1776-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NV, Han W, Li D, Takimoto K, Watkins SC, Levitan ES. Neuronal peptide release is limited by secretory granule mobility. Neuron. 1997;19:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Augustine GJ. Synaptic structure and function: dynamic organization yields architectural precision. Cell. 1995;83:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieregatti E, Meldolesi J. Regulated exocytosis: new organelles for non-secretory purposes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:181–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes F, Montoya M, Morales MA. High-frequency stimuli preferentially release large dense-core vesicles located in the proximity of nonspecialized zones of the presynaptic membrane in sympathetic ganglia. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:446–456. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crivellato E, Nico B, Ribatti D. Ultrastructural evidence of piecemeal degranulation in large dense-core vesicles of brain neurons. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005;210:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Toonen RF, Verhage M. Matrix-dependent local retention of secretory vesicle cargo in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:23–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon C, Goda Y. The actin cytoskeleton: integrating form and function at the synapse. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:25–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix JA, Verkman AS. Crowding effects on diffusion in solutions and cells. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:247–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Terman GW, Simmons ML, Milner TA, Kunkel DD, Schwartzkroin PA, Chavkin C. Dynorphin opioids present in dentate granule cells may function as retrograde inhibitory neurotransmitters. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3736–3750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03736.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhamdani A, Azizi F, Artalejo CR. Double patch clamp reveals that transient fusion (kiss-andrun) is a major mechanism of secretion in calf adrenal chromaffin cells: high calcium shifts the mechanism from kiss-and-run to complete fusion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3030–3036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5275-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Benchenane K, Leveille F, Cacquevel M, Plawinski L, MacKenzie ET, Bu G, Buisson A, Vivien D. Is tissue-type plasminogen activator a neuromodulator? Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulop T, Radabaugh S, Smith C. Activity-dependent differential transmitter release in mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7324–7332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2042-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Sultan P. Variation in the number, location and size of synaptic vesicles provides an anatomical basis for the nonuniform probability of release at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1387–1395. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00142-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Heumann R, Lessmann V. Synaptic secretion of BDNF after high-frequency stimulation of glutamatergic synapses. Embo J. 2001;20:5887–5897. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka Y, Swedlow JR, Paddy MR, Agard DA, Sedat JW. Three-dimensional multiple-wavelength fluorescence microscopy for the structural analysis of biological phenomena. Semin Cell Biol. 1991;2:153–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DY. Amplicon-based herpes simplex virus vectors. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;43(Pt A):191–210. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Wagner CS, Harnau L, Wittemann A. 3D Brownian diffusion of submicron-sized particle clusters. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3326–3334. doi: 10.1021/nn900902b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd P, Lang T, Wenzel D, De Camilli P, Jahn R. Imaging direct, dynamin-dependent recapture of fusing secretory granules on plasma membrane lawns from PC12 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16806–16811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222677399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Gall CM, Lynch G. Presynaptic BDNF promotes postsynaptic long-term potentiation in the dorsal striatum. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14440–14445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3310-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns LM, Levitan ES, Shelden EA, Holz RW, Axelrod D. Restriction of secretory granule motion near the plasma membrane of chromaffin cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:177–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan R, Lemke EA, Klingauf J. Visualization of synaptic vesicle movement in intact synaptic boutons using fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2005;89:2091–2102. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HP, Abney JR, Verkman AS. Determinants of the translational mobility of a small solute in cell cytoplasm. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Takei N, Numakawa T, Ishikawa Y, Suzuki S, Matsumoto T, Katoh-Semba R, Nawa H, Hatanaka H. Biological characterization and optical imaging of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-green fluorescent protein suggest an activity-dependent local release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurites of cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolarow R, Brigadski T, Lessmann V. Postsynaptic secretion of BDNF and NT-3 from hippocampal neurons depends on calcium calmodulin kinase II signaling and proceeds via delayed fusion pore opening. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10350–10364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwinter DM, Lo K, Mafi P, Silverman MA. Dynactin regulates bidirectional transport of dense-core vesicles in the axon and dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2009;162:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Wacker I, Steyer J, Kaether C, Wunderlich I, Soldati T, Gerdes HH, Almers W. Ca2+-triggered peptide secretion in single cells imaged with green fluorescent protein and evanescent-wave microscopy. Neuron. 1997;18:857–863. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Wacker I, Wunderlich I, Rohrbach A, Giese G, Soldati T, Almers W. Role of actin cortex in the subplasmalemmal transport of secretory granules in PC-12 cells. Biophys J. 2000;78:2863–2877. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke EA, Klingauf J. Single synaptic vesicle tracking in individual hippocampal boutons at rest and during synaptic activity. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11034–11044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2971-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Heumann R. BDNF and NT-4/5 enhance glutamatergic synaptic transmission in cultured hippocampal neurones. Neuroreport. 1994;6:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ES, Dreyfus CF, Black IB, Plummer MR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rapidly enhances synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons via postsynaptic tyrosine kinase receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8074–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YX, Zhang Y, Lester HA, Schuman EM, Davidson N. Enhancement of neurotransmitter release induced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10231–10240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner JE, Honigman LS, Grant WF, Gessford SK, Hansen AB, Silverman MA, Scalettar BA. Activity-dependent release of tissue plasminogen activator from the dendritic spines of hippocampal neurons revealed by live-cell imaging. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:564–577. doi: 10.1002/neu.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner JE, Kingma M, Kuhn S, Meliza CD, Cutler B, Scalettar BA. Real-time imaging of the axonal transport of granules containing a tissue plasminogen activator/green fluorescent protein hybrid. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2463–2476. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner JE, Spangler E, Chavarha M, Jacobs C, McAllister K, Schuttner LC, Scalettar BA. Efficient copackaging and cotransport yields postsynaptic colocalization of neuromodulators associated with synaptic plasticity. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:1243–1256. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Christian K, Lu B. BDNF: a key regulator for protein synthesis-dependent LTP and long-term memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby-Phelps K, Castle PE, Taylor DL, Lanni F. Hindered diffusion of inert tracer particles in the cytoplasm of mouse 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:4910–4913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda N, Lu H, Fukata Y, Noritake J, Gao H, Mukherjee S, Nemoto T, Fukata M, Poo MM. Differential activity-dependent secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from axon and dendrite. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14185–14198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase K, Fujiwara T, Umemura Y, Suzuki K, Iino R, Yamashita H, Saito M, Murakoshi H, Ritchie K, Kusumi A. Ultrafine membrane compartments for molecular diffusion as revealed by single molecule techniques. Biophys J. 2004;86:4075–4093. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagappan G, Zaitsev E, Senatorov VV, Jr., Yang J, Hempstead BL, Lu B. Control of extracellular cleavage of ProBDNF by high frequency neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1267–1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807322106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, Woo NT, Sakata K, Zhen S, Teng KK, Yung WH, Hempstead BL, Lu B. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. 2004;306:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa M, Bundman MC, Greenberger V, Segal M. Morphological analysis of dendritic spine development in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00001.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Chan J, Veznedaroglu E, Milner TA. Neuropeptide Y and dynorphin-immunoreactive large dense-core vesicles are strategically localized for presynaptic modulation in the hippocampal formation and substantia nigra. Synapse. 1995;19:160–169. doi: 10.1002/syn.890190303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf R, Bittins CM, Gerdes HH. The role of myosin V in exocytosis and synaptic plasticity. J Neurochem. 2011;116:177–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako Y, Kusumi A. Compartmentalized structure of the plasma membrane for receptor movements as revealed by a nanometer-level motion analysis. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1251–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton MJ, Jacobson K. Single-particle tracking: applications to membrane dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalettar BA. How neurosecretory vesicles release their cargo. The Neuroscientist. 2006;12:164–176. doi: 10.1177/1073858405284258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalettar BA, Swedlow JR, Sedat JW, Agard DA. Dispersion, aberration and deconvolution in multi-wavelength fluorescence images. J Microsc. 1996;182:50–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1996.122402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Quantitative ultrastructural analysis of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5858–5867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05858.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuss Z, Singer A, Holcman D. The narrow escape problem for diffusion in cellular microdomains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16098–16103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakiryanova D, Tully A, Hewes RS, Deitcher DL, Levitan ES. Activity-dependent liberation of synaptic neuropeptide vesicles. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nn1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM, Harris KM. Three-dimensional structure and composition of CA3-->CA1 axons in rat hippocampal slices: implications for presynaptic connectivity and compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8300–8310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08300.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siksou L, Triller A, Marty S. Ultrastructural organization of presynaptic terminals. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MA, Johnson S, Gurkins D, Farmer M, Lochner JE, Rosa P, Scalettar BA. Mechanisms of transport and exocytosis of dense-core granules containing tissue plasminogen activator in developing hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3095–3106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4694-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyer JA, Almers W. Tracking single secretory granules in live chromaffin cells by evanescent-field fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1999;76:2262–2271. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick CC, Harrison MB, Kapur J. Synaptic and extrasynaptic localization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the tyrosine kinase B receptor in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2004;478:405–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.20295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraska JW, Perrais D, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Nagamatsu S, Almers W. Secretory granules are recaptured largely intact after stimulated exocytosis in cultured endocrine cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337526100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WJ, Pozzo-Miller L. Miniature synaptic transmission and BDNF modulate dendritic spine growth and form in rat CA1 neurones. J Physiol. 2003;553:497–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler WJ, Pozzo-Miller LD. BDNF enhances quantal neurotransmitter release and increases the number of docked vesicles at the active zones of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4249–4258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04249.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez M, Dagdug L. Unbiased diffusion to escape through small windows: assessing the applicability of the reduction to effective one-dimension description in a spherical cavity. J Mod Phys. 2011;2:284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski GM, Konopacki FA, Wilczek E, Lasiecka Z, Gorlewicz A, Michaluk P, Wawrzyniak M, Malinowska M, Okulski P, Kolodziej LR, Konopka W, Duniec K, Mioduszewska B, Nikolaev E, Walczak A, Owczarek D, Gorecki DC, Zuschratter W, Ottersen OP, Kaczmarek L. Important role of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in epileptogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:1021–1035. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis M, Leitner I, Jellinger KA, Marksteiner J. Chromogranin peptides in brain diseases. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:727–735. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0648-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG. Kinetic regulation of vesicle endocytosis at synapses. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovleva T, Bazov I, Cebers G, Marinova Z, Hara Y, Ahmed A, Vlaskovska M, Johansson B, Hochgeschwender U, Singh IN, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hurd YL, Kaneko T, Terenius L, Ekstrom TJ, Hauser KF, Pickel VM, Bakalkin G. Prodynorphin storage and processing in axon terminals and dendrites. FASEB J. 2006;20:2124–2126. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6174fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Patterson SL, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin SO, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Morozov A. Presynaptic BDNF required for a presynaptic but not postsynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal CA1-CA3 synapses. Neuron. 2003;39:975–990. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wu Y, Wang Z, Dunning FM, Rehfuss J, Ramanan D, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Release Mode of Large and Small Dense-Core Vesicles Specified by Different Synaptotagmin Isoforms in PC12 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Holtzman DM, Li Y, Osaka H, DeMaro J, Jacquin M, Bu G. Role of tissue plasminogen activator receptor LRP in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:542–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00542.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Movie 2. Visualization of DCG transport within SV clusters. Deblurred time-lapse images showing the slow movement of several BDNF-mCherry-containing DCGs (red) localized at presynaptic vesicle clusters labeled with synaptophysin-EGFP (green). Also shown is the rapid transport of several DCGs that do not localize presynaptically.