Abstract

Traditionally, professionals working with intimate partner violence (IPV) survivors view a victim through a disciplinary lens, examining health and safety in isolation. Using focus groups with survivors, this study explored the need to address IPV consequences with an integrated model and begin to understand the interconnectedness between violence, health, and safety. Focus group findings revealed that the inscription of pain on the body serves as a reminder of abuse, in turn triggering emotional and psychological pain and disrupting social relationships. In many cases, the physical abuse had stopped but the abuser was relentless by reminding and retraumatizing the victim repeatedly through shared parenting, prolonged court cases, etc. This increased participants’ exhaustion and frustration, making the act of daily living overwhelming.

Keywords: domestic violence, trauma, physical and mental health comorbidities

Pain is a common and debilitating concern among those experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV; Wuest et al., 2010). Survivors, especially those with pain, often suffer from depression and other psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Campbell, 2002; Campbell, Kub, Belknap, & Templin, 1997; Campbell et al., 2002; Coker et al., 2002; Dienemann et al., 2000; Stein & Kennedy, 2001). Much research has focused on PTSD (Abbott, Johnson, Koziol-Mclain, & Lowenstein, 1995; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006) and depression (McCauley et al., 1995; Petersen, Gazmararian, & Clark, 2001; Stein & Kennedy, 2001) among women experiencing IPV. However, little is known about how these disorders may intersect to further stigmatize survivors, compromise their functioning, and/or prevent them from seeking help to alleviate IPV.

Background

The morbidity and mortality associated with IPV rank it as a significant national public health issue. A joint initiative of the Violence Against Women Office and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a lifetime IPV prevalence rate for women to be 21.1% (National Institute of Justice & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998). Recent studies in healthcare settings have shown that women report lifetime abuse and physical abuse at 44% and 34% respectively (Thompson et al., 2006). Numerous studies have also documented the physical and mental health toll that IPV takes upon victims of IPV (Devries et al., 2011; Dichter, Cerulli, & Bossarte, 2011; Fisher, Zink, & Regan, 2011; Rhodes et al., 2009). These health consequences range from medical morbidities, such as increased risk for poor sexual health (Humphreys, 2011), gastrointestinal-related discomfort and disease, as well as increased pain and pharmaceutical prescription use (Bonomi, Anderson, Rivara, & Thompson, 2009; Cerulli, Edwardson, Duda, Conner, & Caine, 2010). IPV can also cause or exacerbate mental health burden, including but not limited to depression (Flicker, Cerulli, Swogger, Cort, & Talbot, 2011) and PTSD (Dutton, 2009; Campbell et al., 1997). Studies conducted in the U.S. have documented IPV costs at over $8 billion for morbidity and mortality associated with assaults, rapes, and stalking, as well as lost productivity. (Max, Rice, Finklestein, Bardwell, & Leadbetter, 2004). While legal and medical professions have been implementing interventions for over 2 decades to reduce the prevalence of IPV, the morbidity remains high. Such interventions include screening for IPV in medical settings, mandatory arrest, pro-prosecution, and specialty courts.

Mandatory arrest of perpetrators arose in the mid 1980s as a result of a randomized control trial that led policymakers to believe that arrest would reduce future violence (Sherman, 1992). However, after the policy was implemented across the country, studies done to estimate the generalizability of this trial’s finding demonstrated that for some women, primarily minority women with unemployed partners, this intervention could have negative consequences including future retaliatory violence (Sherman). Nationally, pro-prosecution policies shortly followed the mandatory arrest trends that included moving forward with a prosecution, even in the absence of a victim being willing to testify. As a result, victims lost the power to “drop” a case and could be subpoenaed against their will. For many victims, this lack of control over their case processing left them feeling powerless with the court system (Herman, 2003).

Helping professionals, who may have been well intended, took actions that often resulted in exacerbating victims’ mental health burdens (Herman, 2003; Mills, 1998). While these policies have been studied with mixed results, the majority have examined the safety outcomes for women using re-arrest and re-assault as markers. Few studies to date have examined women’s future physical or mental health as a result of their abuse – even in the absence of continued harassment and emotional abuse, which often occurs under the radar screen of the criminal justice system.

Medical personnel routinely observe the physical and psychological results of IPV, with the former the easiest to ascertain. Estimates suggest that 12–25% of all women evaluated in healthcare emergency departments are there due to IPV injuries (Abbott et el., 1995). Percentages have differed little across demographic groups (Abbott et al.). Physicians cannot consider IPV identification based on injury alone, as that has low predictive power of identifying IPV survivors (Gazmararian et al., 1996). Studies have reported that females experiencing IPV attempt suicide more often than non-IPV affected women with rates as high as 35% of abused women reporting previous suicide attempts (Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). While the significant physical and mental health burdens associated with IPV have been well explored, little research has examined the extent to which victims experience these manifestations long after the violence has stopped, with the exception of Bonomi and colleagues (2010) who examined the health of IPV victims at least 5 years after the violence ended. Their findings documented increases in physical and mental health symptoms, healthcare utilization, and healthcare costs (Fishman, Bonomi, Anderson, Reid, & Rivara, 2010) for women victims and their children as compared to women without IPV experience (Rivara et al., 2007a, 2007b). These findings were consistent in studies with victims found outside the health system, as IPV victims from court also report greater medical service use (Cerulli, Edwardson, Duda, Conner, & Caine, 2010). However, little research has focused on survivors’ pain experiences in connection with their healing after the violence has stopped. This gap remains long after studies have documented increased chronic pain and pain medication prescriptions among IPV victims compared to the general population (Wong, Wester, Mol, Romkens, & Lagro-Janssen, 2007).

Abused women report more headaches, back pain, pelvic pain, abdominal pain and chronic pain than nonabused women (Campbell et al., 2002), and the differences are not always accounted for by abuse-related injuries. Previous research has documented that approximately half of women with chronic pelvic pain report physical or sexual abuse experiences (Poleshuck et al., 2005), as do women who are diagnosed with fibromyalgia. In one study, fibromyalgia patients reported a prevalence rate of 57% for prior sexual and physical abuse histories (Alexander et al., 1998), which far exceeds the rates in the general population. Additionally, abused women had greater use of pain medications than nonabused patients. Among 537 women veterans, those who were raped or physically assaulted during their service were also more likely to report problems with pain (Sadler, Booth, Nielson, & Doebbeling, 2000). These findings are consistent across multiple venues.

Women in obstetrics and gynecology practices who reported physical or sexual abuse in the past year also reported experiencing higher prevalence of frequent physical symptoms, severe physical symptoms, physician visits, and overall poorer self-reported health status compared to women who reported no abuse in the previous year (Kovac, Klapow, Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003). In a study comparing 66 women with current or past abusive relationships to 114 women with no history of abusive relationships, the women exposed to abuse reported significantly higher rates of pelvic pain (Shei, 1990). In a 2007 study in the Netherlands, IPV survivors’ pain was the most common healthcare complaint for all age categories (Wong et al., 2007).

Among 63 gynecology patients with chronic pelvic pain, those who reported IPV in the past year endorsed significantly more difficulties with depression and anxiety (Poleshuck et al., 2005). Furthermore, among 242 low-income gynecology patients, those with depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to report physical and emotional abuse in the past year (Poleshuck, Giles, & Xin, 2006).

These foundational studies reinforce that IPV, pain, and depression frequently co-occur and are associated with significant difficulties. Interestingly, the IPV injury severity or frequency are not associated with the pain symptoms. What is unclear is how these issues may intersect to prevent access to care or perhaps adherence to treatment. IPV survivors’ experiences with depression, physical pain, PTSD, and other difficulties suggest the need for interdisciplinary treatment options. This study fills that gap in the literature. The specific aims were to understand IPV survivors’ perceptions regarding pain and depression and explore the feasibility of a mind-body intervention specifically designed by and for IPV survivors.

Theoretical Model

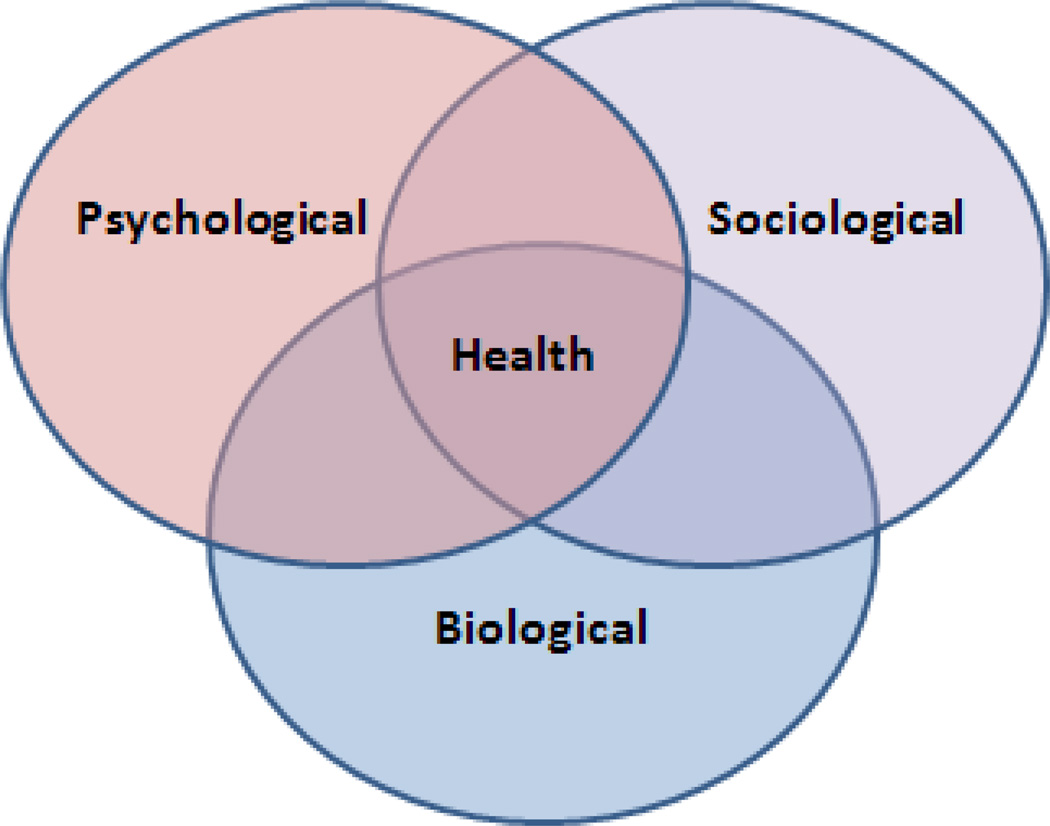

The intersection between pain, depression, and IPV must be further explored. To explore the intersection of IPV, depression, and pain, this study utilized the biopsychosocial model to understand the textured nature of victims’ experiences. Psychiatrist George Engel (1977) introduced the biopsychosocial model as an alternative to the biomedical model, which Engel found to be too exclusionary and reductionistic. The biomedical model tends to view disease solely in terms of biophysical causes and consequences, overlooking the social and psychological implications of illness and excluding mental health complaints from the realm of traditional medicine. Engel’s more expansive biopsychosocial model (see Figure 1) links several dimensions of a person’s life in conceptualizing illness: (a) biological (i.e. genetics, organic causes of disease), (b) psychological (i.e., emotional and behavioral processes), and (c) social (i.e., a patient’s family, friends, and support network). The biopsychosocial model, drawing its roots from systems theory, argues that a profound connection exists between mind and body.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial model.

The biopsychosocial model has evolved into both a philosophy of clinical care and a blueprint for practice; in the words of psychotherapist and writer David Seaburn, “Physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and relational health are all parts of a whole” (Seaburn, Lorenz, Gunn, Gawinkski, & Mauksch, 1996, p. 3). The model is a way of understanding how suffering, disease, and illness are connected across multiple levels of organization, from the societal to the molecular. On a practical level, it conceptualizes the patient’s subjective experience as an essential factor in accurate diagnosis, positive health outcomes, and humane care. A healthcare provider must understand the context of the patient’s life in order to address the root cause of illness. The context of the patient’s life is also important in understanding potential roads to recovery, as well as hurdles the patient might encounter. The biopsychosocial model serves two distinct functions. It is both a philosophy of clinical care and a practical clinical guide. Physicians can understand how suffering, disease, and illness are affected by multiple levels of organization. The model provides patients the opportunity to reveal the context of their lives, which is essential in the accurate diagnosis of their disease and to their health outcomes (Engel, 1980).

This paper is the foundation for a portfolio of research that seeks to implement a new integrated intervention that can address the three intersecting issues of victims’ experiences. It is possible that the bifurcation of service into the realm of medicine and law is responsible for the lingering effects of violence on women. This study defines IPV as physical, psychological, emotional, economic, and sexual abuse by an intimate partner.

Method

Using a framework approach (Pope, Ziebland, & Mays, 2000) coupled with the principles embedded in a community-based participatory research approach (Israel, Enge, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 2001), we explored IPV survivors’ experiences of pain and depression via focus groups. A survivor-informed process evolved as a result of conversations between the research team and SAFER (Survivors Advocating for Effective Reform). The SAFER leadership noted that their members were suffering physical and emotional pain long after their court cases ended. Even after some women’s partners were incarcerated, the physical and emotional pain continued. After partnering on methodological discussions, the research team applied for a grant to the Mind Body Center at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry to conduct a study as a first step in the creation of an intervention to address the unmet needs of survivors. Patient-informed interventions are more successful than those conceived and created in the absence of insight from the target of the intervention (Sormanti, Pereira, El-Bassel, Witte, & Gilbert, 2001).

We recruited a diverse group of women with personal experiences of IPV from a local battered woman’s shelter, the domestic violence docket at family court, and community support groups that service women exposed to IPV. Some of the groups were part of social service agencies, while others were loosely affiliated groups of women supporting each other. One of the focus groups was conducted at a reentry house for women leaving prison. Nationally, incarcerated women frequently report both childhood and intimate partner violence histories. Additionally, they are an underserved population with comorbid conditions. All participants were 18 years or older and English speaking. None of the participants were currently in violent relationships or cohabitating with their former abusive partners. However, many were co-parenting.

For those recruited from community sites, agency staff read an oral announcement in women’s groups the week prior to the focus group. In this way, women could choose not to attend the following week. For those recruited from court, flyers were displayed in a safe waiting room, women’s restrooms, and the childcare center. The flyers had a hangtag listing the study telephone number, which was answered by study personnel.

An attorney with a Ph.D. in criminal justice and 27 years of IPV service experience facilitated the focus groups. A clinical psychologist with ample experience working with IPV victims co-facilitated all but one group. The protocol was utilized in each group and read aloud by the facilitators. Participants received an information letter describing the study and a gift card as a thank you for participation. The groups were recorded with a digital audio recorder with a back up recorder should the primary equipment fail. Once the focus groups were completed, a transcriptionist converted the wave file to a de-identified word transcript to code the data. The University of Rochester Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study.

The facilitators utilized prompts that included but were not limited to the following: “To what extent do you believe IPV victims experience pain in their lives on a daily basis?” and “To what extent to you believe IPV victims experience feeling sad or down? How do these feelings relate or not to relate to their pain?” Once the transcripts were provided, an interdisciplinary team comprised of the attorney and clinical psychologist who conducted the focus groups, an information analyst, and a marriage and family therapy graduate student, led by an anthropologist with expertise in qualitative analysis, reviewed the transcripts.

Team members worked independently to sort data across conceptual categories provided by the biopsychosocial framework. Using a consensus approach, the team finalized categorization and expanded the model to include emotional consequences. Primary themes within each category were those themes identified across all the focus groups. However, important secondary themes were critical for some focus groups and appear linked to their particular settings.

To ensure the internal validity of the data, researchers worked with community contacts to organize a respondent verification session with members of the target community. These are women who had experienced IPV but who were not necessarily participants in the study focus groups (Barbour, 2001). We asked respondent members to comment on the accuracy of the data and the credibility of researchers’ interpretations.

Results

Sample Description

We recruited a diverse sample of 31 female participants. Seventy-four percent (n = 23) were White, and 26% (n = 8) were Black. The majority of the women had received education beyond high school (n = 22, 61%), with 13% having received high school diplomas or the equivalent (n = 4). Five of the participants (16%) had not received a high school degree. Despite being poor, 77% (n = 24) had health insurance of some type (private, Medicaid, Medicare) and were able to seek treatment for medical and mental health conditions if they chose.

Expansion of the Biopsychosocial Model

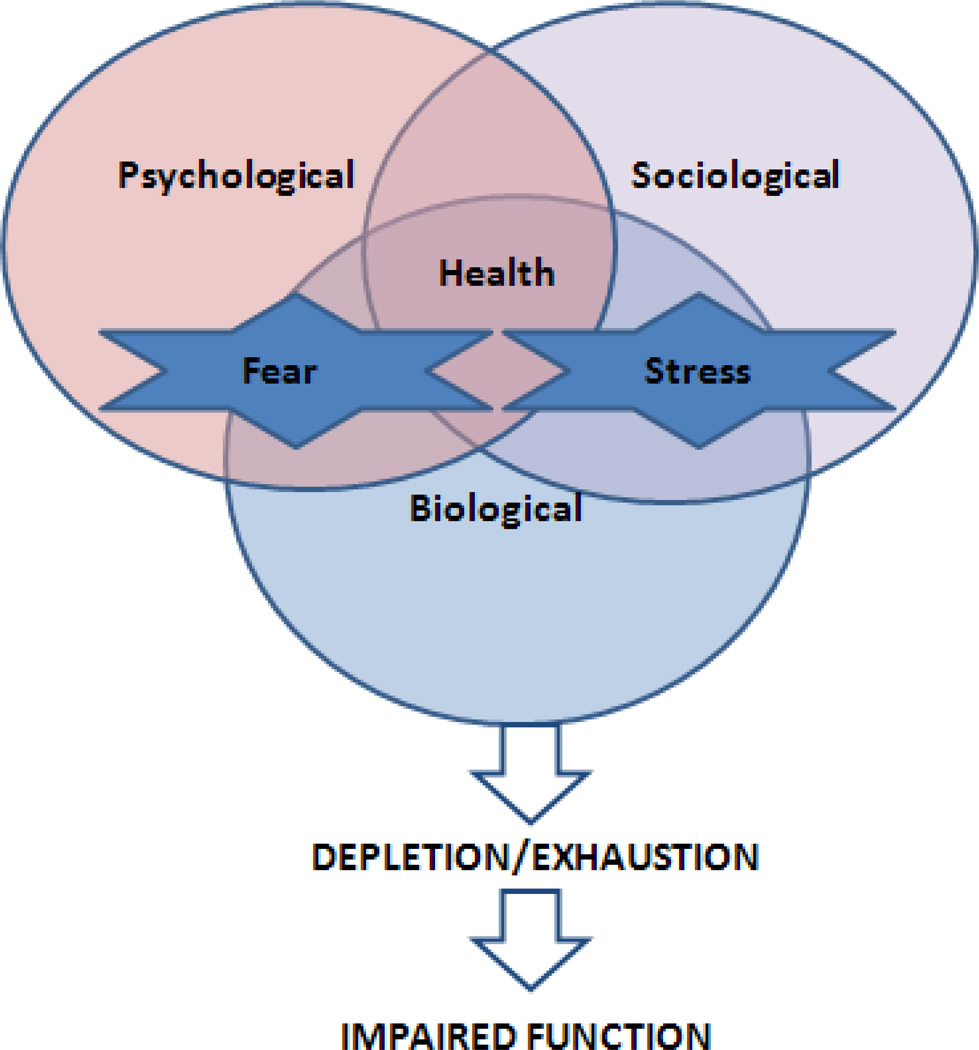

Women described the impact of IPV in ways that reflected the biopsychosocial model, in that they described their pain in both physical and emotional language, and could articulately describe physical, emotional, and social pain resulting from the trauma of abusive relationships. Moreover, they described their symptoms as leading to unrelenting exhaustion, which ultimately led to impaired function. These issues of exhaustion and fatigue were directly related to their safety concerns. Accordingly, we viewed these themes as IPV-specific elaborations of the biopsychosocial model and added them to our conceptualization (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adapted biopsychosocial model to incorporate fear and stress.

Physical Symptoms

Across all five focus groups, women experienced physical symptoms that primarily included pain. They described feeling continuously achy with muscle pain, which was often diagnosed as fibromyalgia. The women described their constant fatigue, and many had been diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. Physical symptoms included headaches, injuries, weight issues, immune dysfunction, and breathing problems. Less frequently described but notable, a few of the women had experienced heart issues. Examples from the interviews follow:

The physical fights from you know the time I got pregnant until I got divorced my body is done. My eardrums been broken, my nose has been broken, like I’m just physically done, exhausted.

… I’ve had a couple instances of abuse, but when I was married to my ex-husband he kicked me in my stomach when I was pregnant. And sometimes, depending on what the scenario is, it’s like I can feel him doing it all over again, like I can actually feel the baby in my stomach moving. So your brain can be very tricky and I can feel those things all over again.

There was also another experience I had a couple months ago where I ran into my ex in the store so it was totally, you know, unexpected. Fortunately I only saw him from afar. But again, I had this reaction internally. It wasn’t a conscious thing, it was automatic and as I was driving home, I started having spasms in my back, intense sharp pain and spasms. And I knew it was related.

I have Hepatitis C. The reason it’s pertinent to my domestic violence is because the person that gave it to me was my abuser. He knew that he had it, and I was with him for months. I ended up pregnant. When I was about 5 months pregnant I found out, and he told me, he admitted to me that he had it. That he had known he had it. He got diagnosed when he was in prison prior to us meeting.

… Yeah the actual violence that’s where it came from. So I had to get stitches and all that. I did start having back problems after that so I just thought maybe it was just back problems. I didn’t think that, you know, it was from that…so I think it’s from that because I used to be kicked in the back and stuff so it could’ve came from that.

I got hit in the back with a baseball bat, so my back is really sore now and then. Um not like severe pain. There’s nothing like no bones are broken…but like, if I sleep on my stomach the whole night through my back will be really sore in the morning.

Well it’s incredibly stressful. I know for myself I suffer from chronic pain. I’ve got a laundry list of medical conditions. And on days where I’m stressed out about something like this, the pain is worse.

Psychological Symptoms

Women also described frequent psychological symptoms that included depression, anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, and flashbacks. These symptoms, similar to the physical symptoms, lasted beyond the abuse and criminal prosecution of their perpetrators. The unrelenting pain and psychological consequences led many of the women to consider suicide as a reasonable alternative to a life plagued by nightmares and constant stress. Despite having support from social service agencies, friends, and families, the women still experienced being overwhelmed and one woman described her experiences as “an emotional hangover.” To some extent, fear may play a pivotal role in these physical and psychological symptoms. Despite reporting that they were now safe from physical harm by their perpetrators, the women reported constant, invasive fear and vulnerability regarding their perpetrators. Even for those with perpetrators behind the walls of prison, they reported that their perpetrators could harass them, evade criminal prosecution, and moreover, the threat of their release always loomed.

The following quotations illustrate these themes:

I agree with that too, and for me, I’ll be goin’ along fine and all of the sudden…I’ll have a very intrusive thought of a past experience and it’ll just, it’ll whip me…[I]t’ll drain all my energy for that second or that half an hour or maybe an hour, so that I’m pretty much unfunctionable.

And even if there’s, God forbid, a week or two of reasonable calm, there’s always a sense of waiting for another shoe is going to drop.

And it was just it, it just doesn’t end. And that was something that I had thought when I left for the final time… it would be over and we went through all when he was arrested…I thought it would be over. When we went through everything in court I thought it would be over. When he was sentenced I thought it would be over. It just never is.

Just even though he again seems to be tampering down to mostly below radar stuff, he continues to be a full-time job just managing him and managing our margin of safety and having to deal with you know normal things…like Mom, we don’t have anymore Cheerios. You know, and again a normal rational sane person should be able to say, Oh okay, let’s put Cheerios on the grocery list. But there are days where just you know stringing those two thoughts together are too hard.

But the feeling like, um for the PTSD is…when I hear fire trucks or ambulances, a fire drill in a building, if there’s too much yelling in a room, you know or… just somebody comes up and scares me, it immediately sets me into a panic mode and I have like these little episodes I call ‘em. And…I get like a sharp pain in my head and I just I start crying and I can actually sometimes if it’s a bad one I can go back and feel, re-feel what was done to me.

I’ve been out of this relationship for about 15 years but when I look at my life when I was in it and it was for about 7 or 8 years…it was constant crisis. So I’m in this crisis mode all the time just trying to get through the day.

The physical and psychological consequences took their toll on the women’s bodies. Their experiences of an inability to function daily in making decisions such as what to eat for breakfast continued the cycle of abuse leading to disappointment and frustration. The perpetrators’ abuse reached into the daily workings of their lives long after the abuse ceased, leaving the victims to bear extreme financial hardship and a lack of social networks. Isolation and loneliness continued to plague the victims. Examples of the immeasurable consequences follow:

He still, he turned off one of the phones in the house yesterday even though I’ve got a contempt order pending in the court. I mean it just never stops.

No matter how many safeguards I put up in place, he always finds a way, he always finds a way.

And I don’t even remember what it’s like to not live in pain anymore. And I look at the fact I’m 27 years old and I’m gonna spend the rest of my life in pain that’s going to get worse. That’s enough to make anybody drive a car off a bridge. And so it’s just simply coping with every single day there is going to be that…every single day you meet those people who are, shall we say, less then sensitive to the fact you can’t do this or you’ve lost friendships because they can’t cope with the fact that you know you may have to cancel on them because you weren’t planning on it being 15 degrees today and you hurt.

Like when you find yourself in a violent, abusive relationship you know sometimes you click into survivor mode. That’s what you have to do. You have to retaliate and be angry and fight back in order to survive, you know. So. I mean I found myself getting angry about situations because I couldn’t be angry at the time, you know what I mean.

And I know when I sleep I’m very tense cause when I wake up I’m like a bundle of pain and nerves. And I’ve gone to massage therapists and they’re like, oh my God I’ve never seen anyone with so many knots before in my life. Because I think I hold a lot of stress when I sleep.

While the descriptions of the victims’ experiences were common across groups, there were some secondary themes that emerged that were not consistent across groups, but nonetheless important. In particular, the group that was comprised of women who had recently been released from a state prison for felony offenses expressed feelings of rage and anger.

Discussion

Participants discussed the chronic abuse leading to pain over time, despite interventions to seek safety and stop the abuse. The inscription of pain on their bodies served as constant reminders of abuse, in turn triggering continual emotional and psychological pain and disrupting social relationships. In many cases, the physical abuse had stopped, but the abuser was relentless in keeping the abuse alive by reminding and retraumatizing the victim, sometimes using other people to do so. Many women reported that pain sensations often served as triggers for retraumatization of their abuse experiences, because it reminded them of when the initial pain occurred. Thus, the ongoing experience of pain left women feeling vulnerable to their abusers, even if the abusers were no longer in their lives. This increased participants’ frustration and made the act of daily living overwhelming.

Given the breadth of physical symptoms, which ranged from pain, gastrointestinal distress, immune-related disorders, and neurological complaints, IPV survivors interacted with numerous professionals who attempted to ameliorate the symptoms without perhaps addressing the underlying issue of ongoing stress. Due to the ongoing nature of emotional abuse, the neglect of self by constantly putting others first (including parents and children), victims could not achieve peace within their bodies. Their constant discomfort was a reminder of their past, wherein their minds and bodies were the crime scene for which they remain the victim.

Even after the relationship terminated, victims had to continue to develop survival skills such as hypervigilence. Additionally, the women still faced the frustration of learning to cope with the loss of their lives before the abuse – lives free of physical, emotional, and sexual violence. Their current lives had lasting pain, both emotional and physical. The frustration continued with being unable to create a new identity or return to their former selves. For women who had experienced childhood abuse, their sense of shame and hopelessness made help-seeking seem overwhelming and useless. While the women expressed emergent consistent themes, differences among the groups also surfaced.

There were clear distinctions between the focus group participants based on their location and the recruitment strategy used. While all participants had suffered abuse, the reentry program for women recently released from prison or jail expressed a different lens on the intersection of IPV, depression, and pain. These participants experienced chronic poverty, life on the streets, humiliation, and structural violence throughout their lives. Their emotional pain may have originated in part from losses due to unexpected deaths, separation from children, and having to recreate their lives in the absence of having their hierarchy of needs met at a basic level (i.e., shelter, food, and social support). Yet, their struggles with anger and rage were expressed as often as their needs for basic survival tools such as shelter and financial resources. The other groups did not express this connection between pain and anger, thus suggesting the possibility of a different breaking point for women who have been incarcerated. Perhaps because they have experienced so much abuse, their victimization history leads to both pain and anger. While more attention is being focused on IPV victims’ use of violence, little research has focused on the rage and anger that many victims may experience in the aftermath of their violence experiences. While men and women have been found to initiate violence in relationships equally often, men use more significant aggression and experience less fear and anger than women, suggesting that women are victimized and distressed by these emotions more often (Hamberger, 2005).

Another interesting secondary theme that emerged among the reentry group was shame. For some participants, this stemmed from their recent convictions and incarcerations, which left them in disrupted family relationships. Shame also surfaced for those who had experienced severe child sexual abuse. These comorbid experiences of IPV and childhood abuse could have a cumulative effect and lead to feelings of shame, as well as loneliness, even after the isolation and violence has ceased.

While this study provides a framework for moving forward to create interventions, the findings cannot be generalized widely. This single jurisdiction study was comprised of participants who self-selected into a study to tell their stories. The data is comprised of self-report with no external review for validity.

Despite study limitations, we see these findings as having important implications for future research. The findings demonstrate a need for tailored interventions for IPV survivors experiencing overlapping concerns of depression and pain long after the violence ends. We aim to use these results toward developing and testing an integrated intervention that will target the unique and overwhelming needs of women with IPV, depression, and pain. Survivors will continue to play an important role in the future research, which implements and evaluates these new interventions.

Conclusion

IPV survivors often suffer from co-occurring pain and depression. Lower income minority women are especially at increased risk for IPV, depression, and pain. Yet little has been known about survivors’ interest in managing their pain and depression following interventions to seek safety (court, shelter). This study, based on community-based participatory research principals (Israel et al., 2001), sought to understand IPV survivors’ experiences with pain and depression and obtain information about the feasibility of mind-body interventions among IPV survivors.

Prior to embarking in a pilot study for a clinical trial of an intervention (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001), an important first step is seeking community consultants. Sormanti and colleagues (2001) suggested focus groups as an important initial step in intervention research where the actual target of the intervention can provide important information and become “meaningful collaborators” in all stages of the process (p. 311). Given the nature of data suggesting the comorbidity of IPV, pain, and depression, it is important to provide IPV survivors the opportunity to help co-create an intervention.

Participants were willing to share their experiences and offer suggestions. For many victims, court remedies, such as protection orders, were not enough to ameliorate their burdens. Many of these women shared children in common with the perpetrator and had to have ongoing contact, sometimes court-ordered, which left them vulnerable to future abuse. This recurring psychological abuse, under the “legal” radar, can trigger emotions and physical responses, often rooted in fear. Such encounters leave victims exhausted, aching, and overwhelmed, which only increases feelings of frustration. Perhaps by addressing the lingering effects of IPV, the depression caused by the cyclical nature of the problem, and the physical and emotional pain, survivors can begin to piece back their lives – to not simply be safer, but happier as well.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by NIMH K01MH75965-01 (Cerulli), K23MH079347-02 (Poleshuck), and a University of Rochester Mind Body Center Grant. The authors wish to thank the survivors who were willing to share their stories with us. To create effective interventions, it is important to have the client’s voice included in the early stages of planning. The quote in the title is attributed to author Dorothy Parker in response to phone calls that interrupted her train of thought while writing. We thought it appropriate to the lives of the women in this study as their attempts to move forward with their life and work were often interrupted by continued harassment from their abusers and/or the lingering trauma of the relationship.

Contributor Information

Catherine Cerulli, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York

Ellen Poleshuck, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York

Christina Raimondi, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York.

Stephanie Veale, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York.

Nancy Chin, Department of Community and Preventative Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York

References

- Abbott J, Johnson R, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR. Domestic violence against women. Incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(22):1763–1767. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.22.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RW, Bradley LA, Alarcon GS, Triana-Alexander M, Aaron LA, Alberts KR, Stewart KE. Sexual and physical abuse in women with fibromyalgia: Association with outpatient health care utilization and pain medication usage. Arthritis Care and Research. 1998;11(2):102–115. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7294):1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research. 2009;44(3):1052–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Kub J, Belknap RA, Templin T. Predictors of depression in battered women. Violence Against Women. 1997;3:217–293. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(10):1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C, Edwardson E, Duda J, Conner K, Caine E. Protection order petitioner's health care utilization. Violence Against Women Journal. 2010;16(6):679–690. doi: 10.1177/1077801210370028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, Kiss L, Schraiber LB, Deyessa N WHO Multi-Country Study Team. Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: Evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Bossarte RM. Intimate partner violence victimization among women veterans and associated heart health risks. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(4):190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann J, Boyle E, Baker D, Resnick W, Wiederhorn N, Campbell J. Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21(5):499–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA. Pathways linking intimate partner violence and posttraumatic disorder. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2009;10(3):211–224. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel G. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Zink T, Regan SL. Abuses against older women: Prevalence and health effects. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(2):254–268. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman PA, Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Rivara FP. Changes in health care costs over time following the cessation of intimate partner violence. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(9):920–925. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1359-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker SM, Cerulli C, Swogger M, Cort N, Talbot N. Depression and posttraumatic symptoms among women experiencing intimate partner violence: Relations to coping strategies, social support, and ethnicity. Violence Against Women Journal. doi: 10.1177/1077801212448897. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(24):1915–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK. Men's and women's use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples: Toward a gender-sensitive analysis. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:131–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. The mental health of crime victims: The impact of legal intervention. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(2):159–166. doi: 10.1023/A:1022847223135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys J. Sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, and intimate partner violence. Health Care for Women International. 2011;32(1):23–38. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.529211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Enge E, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Education for Health. 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovac SH, Klapow JC, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Differing symptoms of abused versus nonabused women in obstetric-gynecology settings. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(3):707–713. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Fo Wong S, Wester F, Mol S, Romkens R, Lagro-Janssen T. Utilisation of health care by women who have suffered abuse. British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57:396–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max W, Rice D, Finklestein E, Bardwell R, Leadbetter S. The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the united states. Violence and Victims. 2004;19(3):259–272. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.3.259.65767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, Derogatis LR. The "battering syndrome": Prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995;123(10):737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills LG. Mandatory arrest and prosecution policies for domestic violence: A critical literature review and the case for more research to test victim empowerment approaches. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1998;25:306–318. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Justice, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. 1998 Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/172837.pdf.

- Petersen R, Gazmararian J, Clark KA. Partner violence: Implications for health and community settings. Women's Health Issues. 2001;11(2):116. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburua E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15(5):599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck E, Dworkin R, Howard F, Foster D, Shields C, Tu X. Multidimensional assessment of the roles of physical and sexual abuse in women with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2005;50:91–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck E, Giles DE, Xin T. Chronic pain and depressive symptoms among financially disadvantaged women's health patients. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15:182–193. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analyzing qualitative data. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Houry D, Cerulli C, Straus H, Kaslow NJ, McNutt LA. Intimate partner violence and comorbid mental health conditions among urban male patients. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(1):47–55. doi: 10.1370/afm.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Thompson CD. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2007a;32(2):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, Thompson RS. Intimate partner violence and health care costs and utilization for children living in the home. Pediatrics. 2007b;120(6):1270–1277. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville B, Carroll K, Onken L. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage 1. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler AG, Booth BM, Nielson D, Doebbeling BN. Health-related consequences of physical and sexual violence. Military Women and Violence. 2000;96:473–480. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaburn DB, Lorenz A, Gunn W, Gawinksi B, Mauksch L. Models of collaboration: A guide for mental health professionals working with health care practitioners. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shei B. Psychosocial factors in pelvic pain. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1990;69(67):71. doi: 10.3109/00016349009021042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman L. The variable effects of arrest on criminal careers: The Milwaukee Domestic Violence Experiment. Criminology. 1992;83(1):137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman LW. Policing domestic violence. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Pereira L, El-Bassel N, Witte S, Gilbert L. The role of community consultants in designing an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13(4):311–328. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.4.311.21431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Kennedy C. Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;66:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Dimer JA, Carrell D, Rivara FP. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(6):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Wilk P, Campbell JC, Lent B, Smye V. Pathways of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Women's Health. 2010;19(9):1665–1674. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]