Abstract

The transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling pathway is a key player in metazoan biology, and its misregulation can result in tumor development. The regulatory cytokine TGFβ exerts tumor-suppressive effects that cancer cells must elude for malignant evolution. Yet, paradoxically, TGFβ also modulates processes such as cell invasion, immune regulation, and microenvironment modification that cancer cells may exploit to their advantage. Consequently, the output of a TGFβ response is highly contextual throughout development, across different tissues, and also in cancer. The mechanistic basis and clinical relevance of TGFβ’s role in cancer is becoming increasingly clear, paving the way for a better understanding of the complexity and therapeutic potential of this pathway.

A Pathway Used and Abused

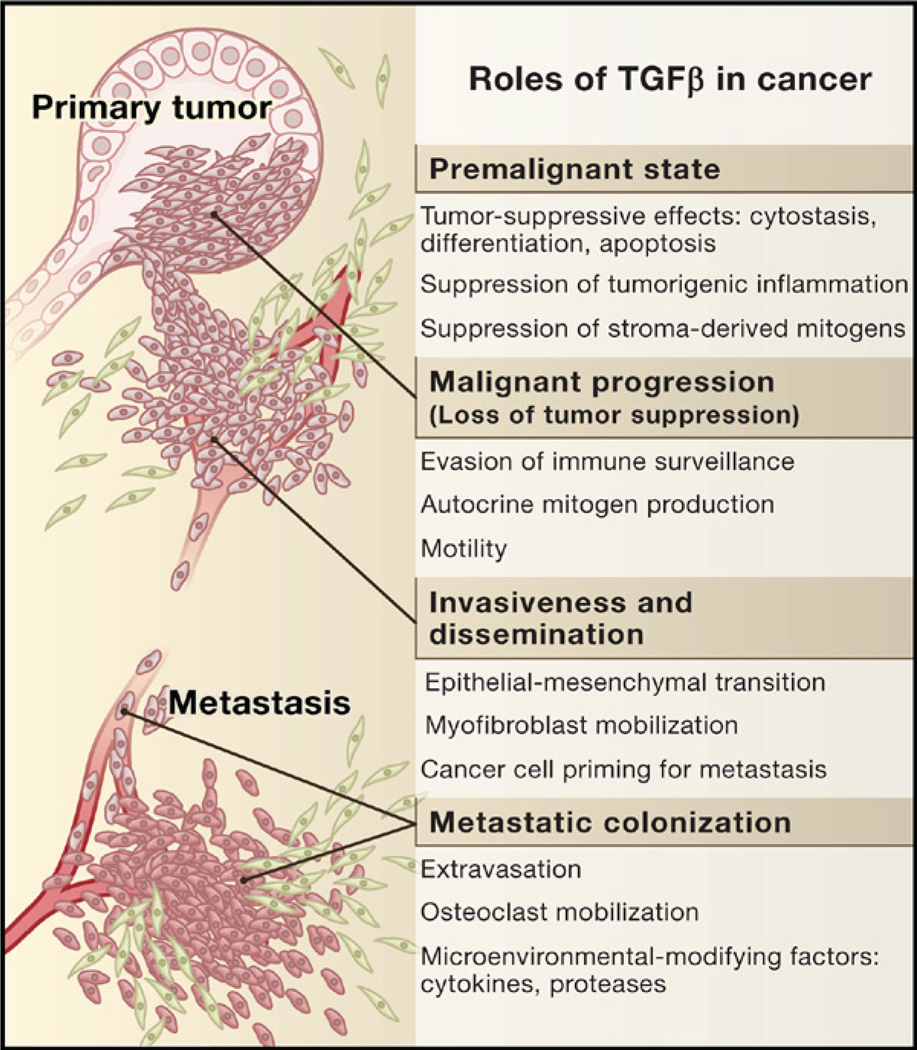

A newcomer in a cytokine family whose members regulate organism development, the regulatory cytokine transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) made its debut with the rise of the vertebrates. TGFβ evolved to regulate the expanding systems of epithelial and neural tissues, the immune system, and wound repair. Tied to these crucial regulatory roles of TGFβ are the serious consequences that result when this signaling pathway malfunctions, namely tumorigenesis. Virtually all human cell types are responsive to TGFβ. TGFβ maintains tissue homeostasis and prevents incipient tumors from progressing down the path to malignancy by regulating not only cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival, and adhesion but also the cellular microenvironment. But as genetically unstable entities, cancer cells have the capacity to avoid or, worse yet, adulterate the suppressive influence of the TGFβ pathway. Pathological forms of TGFβ signaling promote tumor growth and invasion, evasion of immune surveillance, and cancer cell dissemination and metastasis (Figure 1). How can a tumor-suppressor pathway be so radically turned on its head? The answer lies in the points of disruption in TGFβ signaling and the context in which these disruptions occur.

Figure 1. The Role of TGFβ in Cancer.

In normal and premalignant cells, TGFβ enforces homeostasis and suppresses tumor progression directly through cell-autonomous tumor-suppressive effects (cytostasis, differentiation, apoptosis) or indirectly through effects on the stroma (suppression of inflammation and stroma-derived mitogens). However, when cancer cells lose TGFβ tumor-suppressive responses, they can use TGFβ to their advantage to initiate immune evasion, growth factor production, differentiation into an invasive phenotype, and metastatic dissemination or to establish and expand metastatic colonies.

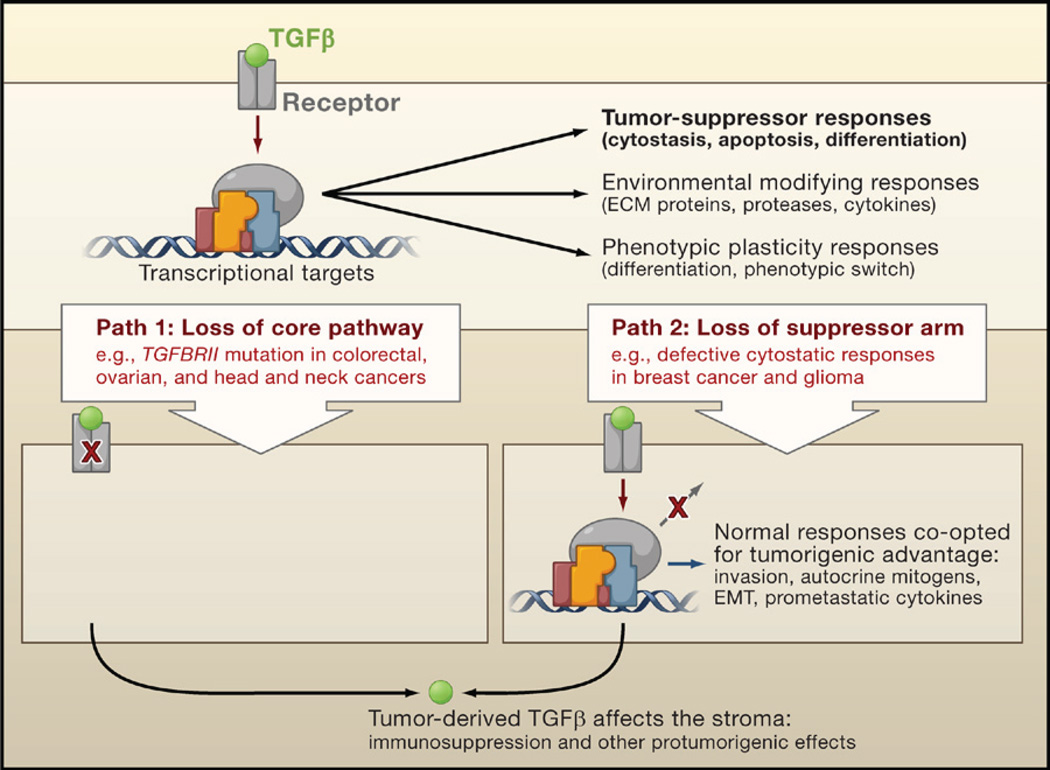

Malignant cells can circumvent the suppressive effects of TGFβ either through inactivation of core components of the pathway, such as TGFβ receptors (Figure 2, Path 1), or by downstream alterations that disable just the tumor-suppressive arm of this pathway (Figure 2, Path 2). If the latter mode of circumvention is used, cancer cells can then freely usurp the remaining TGFβ regulatory functions to their advantage, acquiring invasion capabilities, producing autocrine mitogens, or releasing prometastatic cytokines. Thus, beheading of the TGFβ pathway by receptor inactivation can eliminate tumor suppression, whereas amputation of just the growth-inhibitory arm of this pathway not only abolishes growth suppression but also creates added potential for tumor progression. Also relevant to cancer development are the effects of TGFβ on the tumor stroma. TGFβ is a key enforcer of immune tolerance, and tumors that produce high levels of this cytokine may be shielded from immune surveillance. On the other hand, defective TGFβ responsiveness in immune cells can lead to chronic inflammation and the production of a protumorigenic environment. Tumor-derived TGFβ may recruit other stromal cell types such as myofibroblasts (at the invading tumor front) and osteoclasts (in bone metastases), thus furthering tumor spread.

Figure 2. TGFβ and Tumor Progression.

TGFβ induces tumor-suppressive effects that cancer cells must circumvent in order to develop into malignancies. Cancer cells can take two alternative paths to this end: (1) decapitate the pathway with receptor-inactivating mutations or (2) selectively amputate the tumor-suppressive arm of the pathway. The latter path allows cancer cells to extract additional benefits by co-opting the TGFβ response for protumorigenic purposes. In both cases, cancer cells can use TGFβ to modulate the microenvironment to avert immune surveillance or to induce the production of protumorigenic cytokines.

A dual role of TGFβ in cancer has long been noted, but its mechanistic basis, operating logic, and clinical relevance have remained elusive. What causes TGFβ signaling to be altered in cancer? What steps in tumor progression may benefit from a faulty TGFβ pathway? When does TGFβ act as a metastatic signal? And, most importantly, how can any of this knowledge be used to treat cancer? A combination of improved model systems, new tools for mechanistic dissection, and diligent mining of clinical data is providing fresh answers. Focusing on this progress, this review pays particular attention to new insights that are relevant to cancer in humans.

Operating Logic of the TGFβ System

The human TGFβ family comprises more than 30 factors that can be divided into two distinct branches. Factors such as activin, nodal, lefty, myostatin, and TGFβ are clustered in one family branch, and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), anti-muellerian hormone (AMH, also known as MIS), and various growth and differentiation factors (GDFs) are grouped into the other branch (Derynck and Akhurst, 2007; Roberts and Wakefield, 2003; Shi and Massagué, 2003). Activins, nodals, BMPs, AMH/MIS, and GDFs are key regulators of embryonic stem cell differentiation, body axis formation, left-right symmetry, and organogenesis. Roles of these cytokines in the adult organism, besides those mentioned for TGFβ, include regulation of gonadal function by activins and GDF9, inhibition of muscle development by myostatin, and bone growth and repair by BMPs. TGFβ family members display diverse spatial and temporal expression patterns. TGFβ1, for example, is expressed in many cell types, whereas myostatin is expressed in just a few. The spectrum of temporal diversity in TGFβ expression is exemplified by AMH (brief developmental expression) and BMP2 (sustained expression throughout the organism’s lifetime).

Basics of the TGFβ System

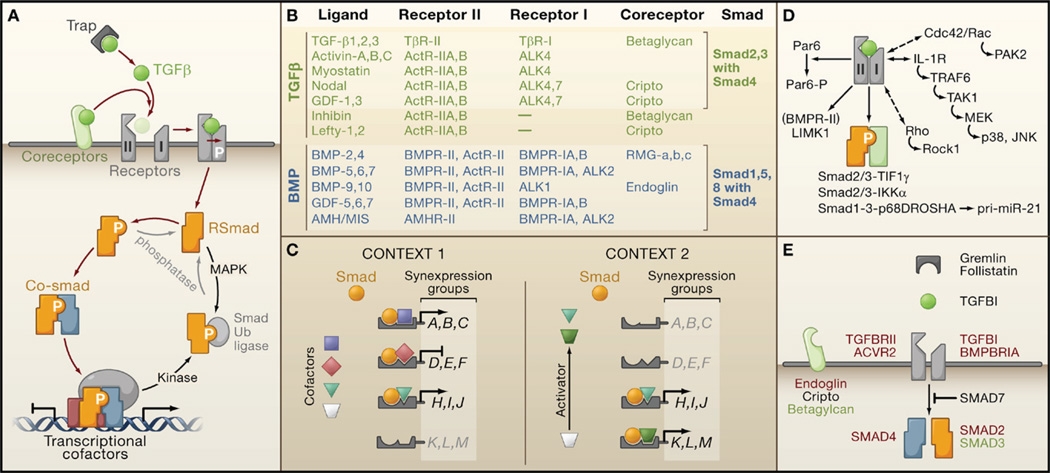

Most members of this cytokine family exist in variant forms (e.g., TGFβ1, β2, and β3). The bioactive cytokine molecule is a dimer composed of a polypeptide chain that is cleaved from a precursor by enzymes such as furins and other convertases. The active TGFβ dimer signals by bringing together two pairs of receptor serine/threonine kinases known as the type I and type II receptors, respectively (Figure 3A). On binding TGFβ, the type II receptors phosphorylate and activate the type I receptors that then propagate the signal by phosphorylating Smad transcription factors. Receptors of the TGFβ branch of the cytokine family phosphorylate Smads 2 and 3, whereas those of the other branch such as BMP receptors phosphorylate Smads 1, 5, and 8 (Figure 3B). Once activated, the receptor substrate Smads (RSmads) shuttle to the nucleus and form a complex with Smad4, a binding partner common to all RSmads (Shi and Massagué, 2003).

Figure 3. Organization of TGFβ Signaling and Weak Links in Cancer.

(A) Ligand traps and coreceptor molecules control the access of TGFβ family ligands to signaling receptors. The ligand assembles a tetrameric complex of receptor serine/threonine kinases types I and II. Receptor-II phosphorylates and activates receptor-I, which then phosphorylates and activates Smad transcription factors (RSmads). Activated RSmads bind Smad4 and further build transcriptional activation and repression complexes to control the expression of hundreds of target genes in a given cell. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and other protein kinases phosphorylate Smads for recognition by ubiquitin ligases and other mechanisms of inactivation. Phosphatases have been identified that reverse these phosphorylation events.

(B) An abridged chart of ligand-receptor-coreceptor-Smad relationships in the TGFβ (green) and BMP (blue) branches of the TGFβ family.

(C) Distinct combinations of transcription partner cofactors in different contexts (e.g., different cell types or conditions) determine the set of genes targeted by specific activated Smads. Each Smad-cofactor combination coordinately regulates a synexpression group of target genes. Smad signaling serves as a node for integrating regulatory signals that impinge on partner cofactors (e.g., Activator signal in Context 2).

(D) Alternative modes of TGFβ signaling include Smad4-independent RSmad signaling (via interactions with TIF1γ, IKKα, p68DROSHA), Smad-independent receptor-I signaling (via small G proteins and MAPK pathways), and direct receptor-II signaling (via Par6, and via LIMK1 in the case of BMPR-II).

(E) Core TGFβ pathway components that are affected by mutation (red), overexpression (black), or downregulation (green) in human cancers.

Smad proteins possess DNA-binding activity, but the Smad4-RSmad complexes must associate with additional DNA-binding cofactors in order to achieve binding with high affinity and selectivity to specific target genes (Figure 3A). These Smad partners are drawn from various families of transcription factors, such as the forkhead, homeobox, zinc-finger, bHLH, and AP1 families (Feng and Derynck, 2005; Massagué et al., 2005). Each Smad4-RSmad-cofactor combination targets a particular set of genes, which is determined by the presence of cognate binding sequence element combinations in the regulatory regions of target genes. Activated Smad complexes additionally recruit transcriptional coactivators, corepressors, and chromatin remodeling factors. Through this combinatorial interaction with different transcription factors, a common TGFβ stimulus can activate or repress hundreds of target genes at once.

Contextual Pleiotropy and Signal Coordination

Built into this mode of TGFβ action are three cardinal features of TGFβ signaling, namely, pleiotropy, coordination, and context dependence. The pleiotropic action of this pathway is based on the large set of transcription factors that can interact with activated Smads to target a large number of functionally diverse genes (Figure 3C). A series of surface hydrophobic patches and pockets on the Smad protein make it particularly suitable for such interactions (Shi and Massagué, 2003). Coordinated regulation of different genes is achieved by their sharing of enhancer element configurations that are recognized by a particular Smad-cofactor complex. Within a TGFβ transcriptional program, this feature defines “synexpression groups” of coordinately regulated genes (Gomis et al., 2006a; Niehrs and Pollet, 1999; Silvestri et al., 2008). Cells of different types or exposed to different conditions express different repertoires of Smad transcriptional partners, thus linking their TGFβ response to their cellular context. This operating logic allows for the remarkable plasticity of the TGFβ pathway and sets the stage for the severe consequences of its misguided activity in cancer.

Noncanonical TGFβ Signaling Pathways

Variant signaling branches and Smad-independent pathways coexist with the canonical Smad pathway in the response to TGFβ (Figure 3D). Smad4 is essential for many but not all TGFβ-regulated transcriptional responses. Indeed, ablation of SMAD4 in the mammary gland, liver, or pancreas of mice does not derail the development of the targeted organ even though the disruption of TGFβ family receptors does (Bardeesy et al., 2006; Li et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2005a). The existence of RSmad-dependent but Smad4-independent signaling functions is supported by the identification of TIF1γ (transcription intermediate factor 1γ, also known as TRIM33) as a TGFβ signal mediator. TIF1γ interacts with receptor-activated Smad2/3 in competition with Smad4 and participates in TGFβ-induced erythroid differentiation through as yet unknown targets (He et al., 2006). TIF1γ can also act as a Smad4 inhibitor (Dupont et al., 2005). Similarly, TGFβ-activated Smad2/3 in mouse keratinocytes binds to IκB kinase α (IKKα) to control expression of the Myc oncogene antagonist MAD1 and keratinocyte differentiation (Descargues et al., 2008). In a remarkable new finding, BMP-activated Smad1 and TGFβ-activated Smad2/3 bind to p68, a component of the microRNA (miRNA) processing complex DROSHA, to target the primary miR-21 transcript (pri-miR-21) for miR-21 production in vascular smooth muscle cells (Davis et al., 2008). The miRNA miR-21 induces a contractile cell phenotype by downregulating the suppressor PDCD4.

Smad-independent modes of TGFβ signaling also include the interaction of the TGFβ receptor complex with the interleukin-1 receptor-effector module called IL1R-TRAF6-TAK1, leading to the activation of JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades (Lu et al., 2007). Through as yet unknown intermediates, the TGFβ receptor can also engage the Rho-Rock1 signaling module (Bhowmick et al., 2001), as well as the Cdc42/Rac1-PAK2 complex (Suzuki et al., 2007). The type II receptors can signal through substrates other than the type I receptors. In epithelial cells, TβR-II phosphorylates Par6, freeing it from a preformed Par6-TβR-I complex. This allows Par6 to trigger the dissolution of tight junctions in the context of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (Ozdamar et al., 2005). The BMP type II receptor can also signal through non-type I receptor substrates: Its unique C-terminal domain modulates the actin cytoskeleton regulatory kinase LIMK1 (Foletta et al., 2003). Many of these noncanonical TGFβ signaling pathways have been investigated in cultured cells, but their relevance to human cancer remains to be established.

Points of Disruption in the TGFβ Pathway in Cancer

Under pressure to avoid tumor-suppressive effects, some cancer cells accumulate inactivating mutations in the TGFβ receptors and the Smad proteins (Figure 3E), a pathway for which detailed accounts of the components have been made (Feng and Derynck, 2005; Massagué et al., 2005; Shi and Massagué, 2003; Taylor and Wrana, 2008). A growing body of evidence also implicates the BMP pathway as a target of disruption in cancer. What follows is an abridged overview highlighting the points of disruptions in these pathways in cancer.

Signaling Receptors

Seven type I receptors and five type II receptors paired in different combinations provide the receptor system for the entire TGFβ family (Figure 3B). The cytoplasmic region of these receptors contains a serine/threonine kinase domain. A short segment (the GS domain) just N-terminal to the kinase domain in the type I receptors provides a switch for kinase activation. In the basal state, the GS domain presses against the active center of the kinase, repressing catalytic competence. Ligand-dependent phosphorylation by a type II receptor switches the GS domain from a repressor element into a docking site for substrate Smad proteins. Most members of the TGFβ family share several type I and type II receptors, but TGFβ is an exception. Among the type II receptors, only TβRII can bind to TGFβ. Furthermore, only TβRI can be incorporated into this TβRII-TGFβ complex (Groppe et al., 2008; Shi and Massagué, 2003).

What alterations are found at the level of the TGFβ receptors in cancer? Biallelic inactivation of TGFBRII by mutations that truncate the receptor protein or inactivate its kinase domain occur in colon, gastric, biliary, pulmonary, ovarian, esophageal, and head and neck carcinomas (for a detailed listing of known mutations, see Levy and Hill, 2006). TGFBRII mutations are highly represented in tumors with microsatellite instability, a pathological condition caused by mutations in replication mismatch repair genes. The TGFBRII coding region contains a 10-base poly-adenine repeat prone to replication errors that insert or delete one or more adenines. These poly(A) errors remain unrepaired in tumors with microsatellite instability, yielding mutant TGFBRII alleles that encode inactive receptors. This mode of TGFBRII mutation is frequently seen in the inactivation of the second TGFBRII allele. Poly(A) tract TGFBRII mutations accumulate in a majority of sporadic gastrointestinal and biliary carcinomas with microsatellite instability, as well as in lung adenocarcinomas and gliomas. These mutations are also almost universally present in colon cancer patients with inherited mutations in mismatch repair genes. Interestingly, breast tumors and endometrial tumors with microsatellite instability do not accumulate TGFBRII mutations. Biallelic mutations in a poly(A) tract of the activin type II receptor ACVR2 occur in colon tumors with microsatellite instability alongside TGFBRII mutations, suggesting that ACVR2 also plays a role in tumor suppression (Levy and Hill, 2006).

Other mutation types such as frameshift and missense mutations in the TGFBRI coding region are present in subsets of ovarian, esophageal, and head and neck cancers. A common hypomorphic allele, TGFBRI*6A, is associated with increased risk in certain types of cancers (Kaklamani et al., 2004). Receptor alterations can also occur at the epigenetic level. Decreased expression of TGFBRI or TGFBRII occurs frequently in lung, gastric, prostate, and bladder cancers. In gastric cancer, this defect is linked to methylation of the TGFBRI promoter. Finally, germline mutations in the BMP type I receptor BMPRIA occur in a subset of Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome (JPS) cases, an autosomal dominant disorder with predisposition to gastrointestinal polyps and cancer (Levy and Hill, 2006, and references therein).

Coreceptors and Ligand Traps

Various membrane proteins enhance binding of ligands to the receptors (Figure 3A) (Shi and Massagué, 2003). The membrane-anchored proteoglycan betaglycan (also called TGFβ type III receptor) binds and presents TGFβ to the TGFβ type II receptor. Betaglycan also mediates the binding of the activin antagonist, inhibin, to activin receptors. The betaglycan-related protein, endoglin (ENG), functions as a BMP9 coreceptor. Inherited mutations in Endoglin cause hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome that also includes early-onset JPS (Sweet et al., 2005).

A structurally diverse group of proteins (ligand traps) that “trap” TGFβ family members to limit their access to membrane receptors play critical roles during morphogenesis of the embryo and in the adult (De Robertis and Kuroda, 2004; Massagué and Chen, 2000). For example, the cleaved proregion of the TGFβ precursor called the latency-associated protein (LAP) sequesters TGFβ in a complex that is anchored to the extracellular matrix by the latent TGFβ-binding proteins (LTBP1-4). A different set of proteins (noggin, chordin, gremlin, follistatin, DAN/cerberus, and Bmper) trap BMPs, whereas activins are trapped by follistatins and nodals by DAN/cereberus. Follistatin overexpression is implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis (Rodgarkia-Dara et al., 2006) and breast cancer bone metastasis (Kang et al., 2003b). Similarly, Gremlin-1 has been linked to skin basal cell carcinoma and other cancers (Sneddon et al., 2006).

Receptor Regulated Smad Proteins

RSmads act as a node for the integration of diverse signaling pathways. In the basal state, RSmads undergo constant nucleocytoplasmic shuttling involving direct interactions with nuclear pore proteins as well as with importins and exportins (Xu, 2006). RSmad phosphorylation by type I receptors occurs at two C-terminal serine residues and triggers the accumulation of RSmads in the nucleus. Cellular stress pathways and receptor tyrosine kinases activate MAPKs, which phosphorylate a linker region that joins the Smad N-terminal and C-terminal domains (MH1 and MH2 domains, respectively). Phosphorylation of these sites in Smad1 enables the binding of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Smurf1, which bars Smad1 interaction with nucleoporins and leads to Smad1 polyubiquitination and degradation (Sapkota et al., 2007). Linker phosphorylation of Smad2/3 may similarly enhance the binding of other ubiquitin ligases. The protein PPM1A may act as a Smad C-terminal phosphatase, whereas the proteins SCP1–3 function as linker and Smad1 C-terminal phosphatases (Lin et al., 2006; Sapkota et al., 2006). Thus, the opposing actions of TGFβ receptor kinases and Smad phosphatases keep Smad proteins in a rapid activation-deactivation cycle, tying signal flow to receptor activity.

Despite their crucial function in connecting signaling pathways, RSmad mutations are infrequent in cancer. Intragenic mutations in SMAD2 occur in a small proportion of colorectal cancers (Sjoblom et al., 2006), and loss of Smad3 expression has been noted in gastric cancer and T cell lymphoblastic leukemia (Levy and Hill, 2006). SMAD2 is located on chromosome 18q21, a region that suffers loss of heterozygosity in pancreatic and colon cancers. However, the minimal deleted region in 18q21 also includes SMAD4/DPC4 (Deleted in Pancreatic Carcinoma locus 4), which is a well-established tumor suppressor (see below).

Co-Smads

In contrast to SMAD2 and SMAD3, SMAD4/DPC4 is a notable target of inactivation in cancer (reviewed in Levy and Hill, 2006). In pancreatic cancers, chromosome 18q21 deletions invariably affect SMAD4, and deletion or inactivating mutations disrupt the other allele. SMAD4 mutations, present in more than half of pancreatic carcinomas, are close in prevalence to mutations in KRAS, p53, and p16INK4A (Jaffee et al., 2002). SMAD4 is also mutated in more than half of sporadic colorectal tumors without microsatellite instability (but not in tumors with microsatellite instability), in a high proportion of esophageal tumors, and with less frequency in other cancers (Sjoblom et al., 2006). Germline SMAD4 mutations also occur in a subset of JPS cases. However, Smad4 inactivation in tumors is generally a late event linked to progression to overt carcinoma (see below). Interestingly, tumor-associated missense mutations in SMAD4 cluster in the MH1 and MH2 domains of the protein and have thus proven to be highly informative in structural and functional studies of Smad4.

Smad Antagonists

Every step of the TGFβ pathway is tightly controlled by specialized factors, several of which also suffer alterations in human cancers. Smad6 and Smad7 are inhibitory Smads that negatively control TGFβ pathway activity in response to feedback loops and antagonistic signals (Massagué et al., 2005). Smad6 competes with Smad4 for binding to receptoractivated Smad1, and Smad7 recruits Smurf to TGFβ and BMP receptors for inactivation. Overexpression of Smad7 and suppression of TGFβ signaling has been reported for endometrial carcinomas and thyroid follicular tumors (Cerutti et al., 2003; Dowdy et al., 2005). In immune cells of the colonic mucosa, Smad7 overexpression is associated with chronic inflammation, which predisposes the tissue to becoming cancerous (see below). Perhaps related to this defect, a genome-wide association study revealed that certain common alleles of SMAD7 are associated with colorectal cancer (Broderick et al., 2007).

Smad function is also directly inhibited by transcriptional repressors such as Ski and SnoN (Ski-like). SKI and SKIL suffer deletions as well as amplifications in colorectal and esophageal cancers, raising the possibility that these genes act as oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes depending on the context (Zhu et al., 2007). In acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), transcriptional repressors encoded by the chimeric genes AML1/ EVI-1 from a 3:21 translocation and AML1/ETO from an 8:21 translocation interact with Smad3 and suppress TGFβ signaling (Letterio, 2005).

Sources of TGFβ in Tumors

In normal, unstressed tissue, sustained basal release of TGFβ by local sources may suffice for the maintenance of homeostasis. However, under conditions of tissue injury, TGFβ is abundantly released by blood platelets and various stromal components to prevent runaway regenerative cell proliferation and inflammation. Such conditions occur in tumors as well. Indeed, TGFβ is frequently present in the tumor microenvironment, initially as a signal to prevent premalignant progression, but eventually as a factor that malignant cells may use to their own advantage. The presence of TGFβ has been documented in many subsets of tumors (commonly assayed by Smad2 C-terminal phosphorylation; Xie et al., 2002), indicating that this cytokine is prominently associated with cancer.

Sources of TGFβ in tumors vary and include the cancer cells themselves as well as various cells of the tumor stroma, with each source leading to context-dependent functional consequences. Tumors are infiltrated by leukocytes, macrophages, and bone marrow-derived endothelial, mesenchymal, and myeloid precursor cells. The presence of these tumor-infiltrating cells coincides with TGFβ secretion and is thus a suspected source of the accumulation of TGFβ1 at the invasion front of the tumor (Yang et al., 2008). The presence of TGFβ1 in this location is associated with tumor progression (Dalal et al., 1993). Specialized local sources of TGFβ are also important in the context of metastasis. The bone matrix stores TGFβ, which becomes mobilized during osteolytic metastasis (Kingsley et al., 2007). Activation of latent TGFβ is a complex process involving diverse enzymatic and nonenzymatic activities that are likely to vary in different tumors.

Tumor Suppression by TGFβ

The frequent disruption of TGFβ and BMP receptors and of Smad4 in cancer reflects the relevance of the tumor suppressive roles of these pathway components. However, these roles are highly contextual, both in terms of the tumor stage and suppressor mechanism that are targeted by these pathways.

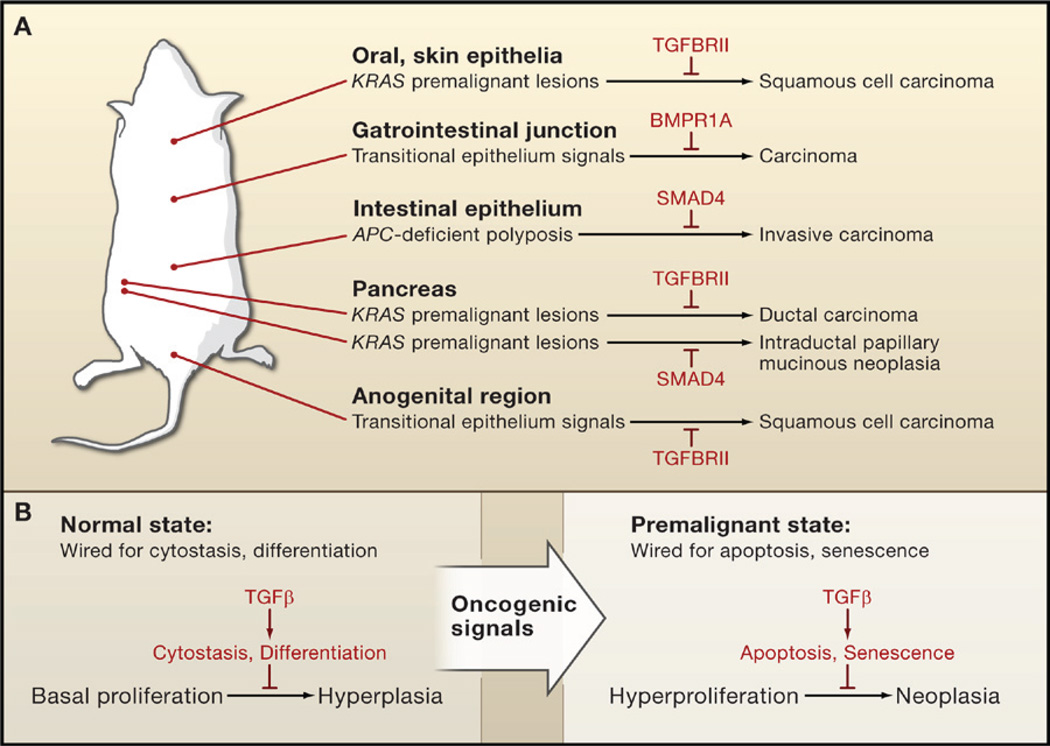

Suppression of Premalignant Progression

Despite the occurrence of TGFβ receptor mutations in cancer, tissue-specific inactivation of TGFBRII alone in mouse models seldom leads to spontaneous tumor formation. Targeted deletion of TGFBRII in the mouse mammary epithelium resulted in excessive lobular-alveolar cell proliferation (hyperplasia; Forrester et al., 2005). However, no developmental or pathological changes were apparent upon deletion of TGFBRII in the epithelia of the oral cavity, esophagus, forestomach (Lu et al., 2006), pancreas (Ijichi et al., 2006), intestine (Muñoz et al., 2006), or skin (Guasch et al., 2007) of mice. Also, no disruption of normal development or spontaneous tumor formation was apparent upon tissue-restricted SMAD4 ablation in the mouse liver (Wang et al., 2005b) or pancreas (Bardeesy et al., 2006), although Smad4 deficiency in mouse mammary glands did cause spontaneous squamous cell carcinomas involving transdifferentiation of mammary epithelium to squamous epithelium (Li et al., 2003). Indeed, the role of TGFβ in constraining epithelial growth only becomes readily apparent under conditions of tissue injury or oncogenic stress. Skin wounds heal faster, with a rapid rate of keratinocyte proliferation and migration, in SMAD3 null mice (Ashcroft et al., 1999) and mice with targeted deletion of TGFBRII in basal keratinocytes of stratified epithelia (Guasch et al., 2007). Moreover, deficiencies in TGFBRII or SMAD4 strongly accelerate the malignant progression of neoplastic lesions initiated by oncogenic stimuli (Figure 4A). Ablation of TGFBRII favors carcinoma conversion of intestinal polyps initiated by inactivation of the APC (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli) gene or chemical mutagenesis (Biswas et al., 2004; Muñoz et al., 2006). The same is observed for mammary tumors initiated by polyoma virus middle-T oncogene (PyMT) (Forrester et al., 2005) and premalignant lesions initiated by KRAS oncogene in the pancreas (Ijichi et al., 2006), the oral and esophageal epithelium (Lu et al., 2006), or the skin (Guasch et al., 2007). Heterozygous inactivation of SMAD4 does not cause carcinomas on its own but potentiates the progression of intestinal polyps to carcinoma in APC-deficient mice with loss of the remaining wild-type SMAD4 allele (Takaku et al., 1998). Likewise, KRAS-induced premalignant pancreatic lesions progress to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia when combined with deletion of SMAD4 (Bardeesy et al., 2006). Intriguingly, a constitutively activated TGFBRI transgene has an inhibitory effect on mammary tumors driven by the oncogene ErbB2/HER2, possibly reflecting a stifling of malignant conversion by the TGFβ receptor (Muraoka et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 2003). These findings are consistent with the fact that somatic mutation of SMAD4 in pancreatic cancer and of TGFBRII or SMAD4 in colorectal cancer emerge during the adenoma to carcinoma transition (Jaffee et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2008).

Figure 4. Blocking Premalignant Progression by Tumor-Suppressor Proteins.

(A) TGFβ and BMP suppress the progression of premalignant states in mouse models. Genetic ablation of TGFβ or BMP receptor genes (TGFBRII and BMPR1A, respectively) or SMAD4 alone does not normally lead to carcinoma formation. However, inactivation of these pathways allows carcinoma progression in transitional epithelia and in premalignant lesions caused by oncogene (KRAS) activation or tumor-suppressor gene (APC) inactivation.

(B) Influence of the context on choice of TGFβ tumor-suppressor response. Cells under normal conditions are generally wired for cytostatic or differentiation responses to TGFβ; a loss of TGFβ signaling in this context causes elevated but still regulated cell proliferation (hyperplasia). In contrast, premalignant cells and other hyperproliferative cell states are wired for apoptotic and senescence responses; a loss of TGFβ signaling in this context enables tumor progression (neoplasia).

Contextual Choice of Tumor-Suppressor Effects

A detailed analysis of the effect of TGFBRII ablation in stratified epithelia of mice has shed light on the circumstances that engage TGFβ as an enforcer of epithelial homeostasis and a suppressor of tumor progression (Guasch et al., 2007). Under wild-type conditions, the antiproliferative effects of TGFβ on epithelial cells counter the effects of local mitogenic stimulation. In the absence of TGFBRII, TGFβ-independent apoptosis limits hyperplasia. However, under conditions of intense mitogenic stimulation, such as those that occur naturally in the transitional epithelia of the anogenital region or pathologically as a result of KRAS oncogene expression, the TGFβ pathway engages proapoptotic mechanisms to offset the elevated rate of cell proliferation. Thus, TGFβ triggers cytostasis or apoptosis depending on the intensity of the proliferative signals (Figure 4B). In the absence of TGFBRII, transitional epithelia and premalignant cells generate squamous cell carcinomas. Similarly, mice with a targeted disruption of BMPR1A develop polyps in the intestinal epithelium but carcinomas in the gastrointestinal transitional zone (Bleuming et al., 2007).

The dependence of TGFβ apoptotic responses on contextual determinants is also apparent in the mammary epithelium. In mouse mammary glands, TGFβ expression occurs in virgin female mice and well into pregnancy without causing apoptosis. It subsides during late pregnancy and lactation. Weaning triggers a sharp surge in TGFβ3 expression, which participates in the massive wave of apoptosis that drives involution (Nguyen and Pollard, 2000). Expression of a constitutively active TGFBRI transgene in the mammary epithelium causes apoptosis only during late pregnancy (Siegel et al., 2003). Interestingly, primary epithelial cell cultures from late-pregnancy glands respond to TGFβ with cytostasis, not with apoptosis. Apoptosis also occurs in hyperplastic lesions of TGFBRII null mammary epithelium (Forrester et al., 2005). Thus, the competence to mount an apoptotic response to TGFβ is tied to conditions of intense proliferative activity and to as yet unknown environmental cues.

Cell-Autonomous Tumor-Suppressor Mechanisms

Insights into the mechanisms that mediate TGFβ-dependent cytostasis, differentiation, or apoptosis are provided by the molecular dissection of this pathway in model cell systems and the ongoing validation of these findings in mouse models and human tumor tissue samples.

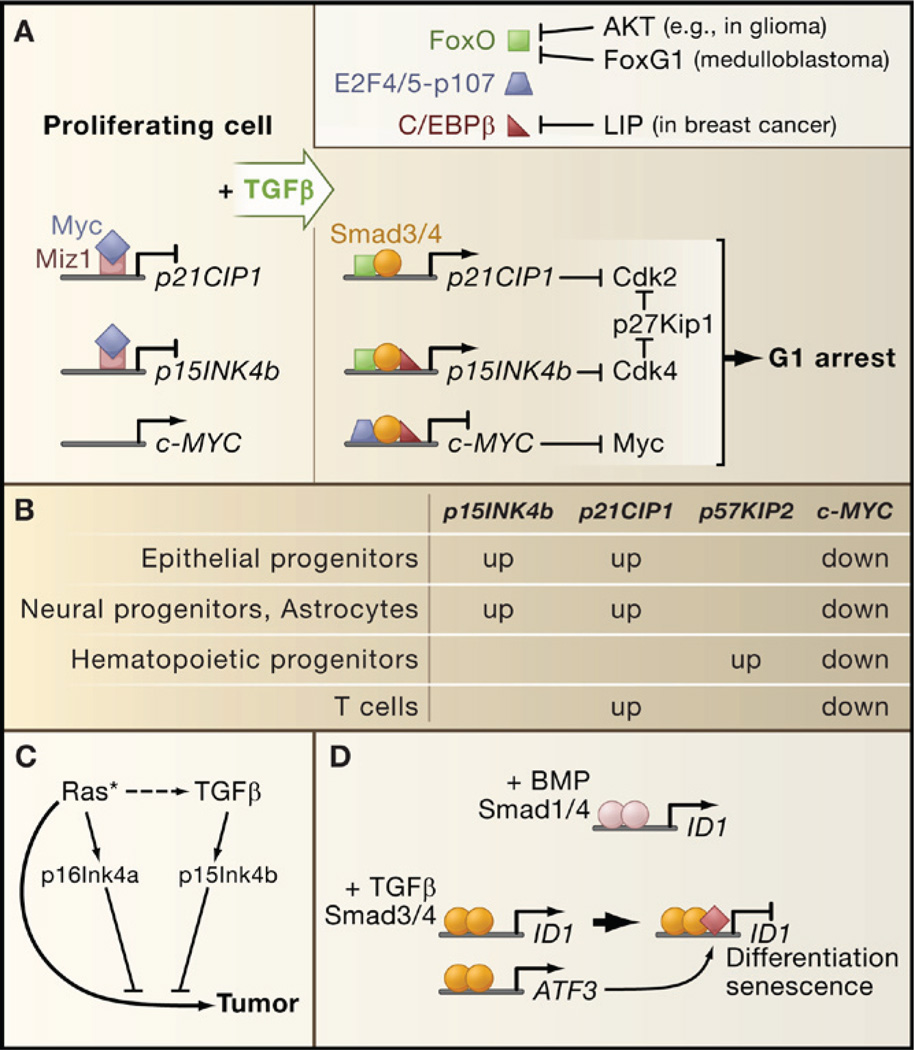

Cytostatic Mechanisms

TGFβ inhibits progression of cell cycle phase G1 through two sets of events: mobilization of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors and suppression of c-Myc (Figure 5A). In epithelial cells, TGFβ induces expression of p15Ink4b, which inhibits cyclinD-cdk4/6 complexes, and of p21Cip1, which inhibits cyclinE/A-cdk2 complexes. Smad3/4 complexes with FoxO transcription factors to target the p15INK4b and p21CIP1 promoters for transcriptional activation (Gomis et al., 2006b; Seoane et al., 2004). Induction of these genes also requires Sp1 (Pardali et al., 2000). Another CDK inhibitor, p27Kip1, undergoes mobilization from an inactive state bound to cyclin D-cdk4 to an active state that is displaced from these complexes by p15Ink4b to target cyclin E/A-cdk2 (Figure 5B). TGFβ stimulates expression of p21Cip1 in T cells (Wolfraim et al., 2004), of p57Kip2 in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (Scandura et al., 2004), and of p15Ink4b and p21Cip1 in astrocytes and neural progenitor cells (Rich et al., 1999; Seoane et al., 2004) (Figure 5B). Thus, the particular CDK inhibitors involved in a TGFβ cytostatic response depend on the cell type.

Figure 5. Tumor-Suppressive Transcriptional Responses to TGFβ.

(A) A TGFβ-activated Smad complex in epithelial cells represses c-MYC expression (right panel) and facilitates the induction of CDK inhibitory genes (left panel). Smad-FoxO complexes target p15INK4b and p21CIP1 for transcriptional induction, leading to CDK inhibition. The resulting surge of p15Ink4b releases p27Kip1 from a latent Cdk4-bound state to inhibit CDKs further. FoxO factors can be inhibited by the antagonistic family member FoxG1 or by Akt-mediated phosphorylation in tumors with a hyperactive PI3K-Akt pathway. Overexpression of the C/EBPβ isoform LIP in metastatic breast cancer inhibits C/EBPβ, a common partner of c-MYC and p15INK5b regulatory Smad complexes.

(B) Different cell types engage different CDK inhibitor in their TGFβ cytostatic response, whereas c-MYC downregulation is a general feature of the response.

(C) p16INK4a induction by endogenous sensors of hyperactive Ras (or other oncogenic signals) collaborates with p15INK4b to mediate tumor suppression.

(D) ID1 repression creates conditions for terminal differentiation and senescence. Differential effects of BMP and TGFβ on ID1 expression are based on the ability of TGFβ-activated Smads to recruit the transcriptional repression factor ATF3 to the ID1 regulatory region. Expression of ATF3 itself is induced by the Smad pathway.

c-MYC is a key transcriptional inducer of cell growth and division. In keratinocytes and mammary epithelial cells, c-MYC downregulation is mediated by a TGFβ-induced protein complex containing Smad3/4, p107, E2F4/5, and C/EBPβ (Chen et al., 2002; Gomis et al., 2006b). Smad3/4 and E2F4/5 recognize a proximal element in the c-MYC promoter and p107 is thought to recruit corepressors. Interestingly, C/EBPβ is required for repression of c-MYC by this complex and for activation of p15INK4b by a Smad3/4-FoxO complex (Gomis et al., 2006b). Thus, C/EBPβ coordinates the p15INK4b and c-MYC responses to TGFβ. Additional coordination is provided by the transcription factor Miz-1, which in proliferating cells recruits c-Myc as a repressor to the transcriptional start regions of the p15INK4b and p21CIP1 promoters (Seoane et al., 2002; Staller et al., 2001) (Figure 5A).

As cotransducers of Smad signals, FoxO, E2F4/5, and C/EBPβ integrate multiple inputs into the TGFβ cytostatic program. Signals that regulate C/EBPβ can influence the effects of TGFβ on c-MYC and p15INK4b expression, whereas signals that inhibit FoxO activity, such as Akt-mediated phosphorylation or FoxO interaction with the inhibitory factor FoxG1, inhibit p15INK4b and p21CIP1 induction (Seoane et al., 2004).

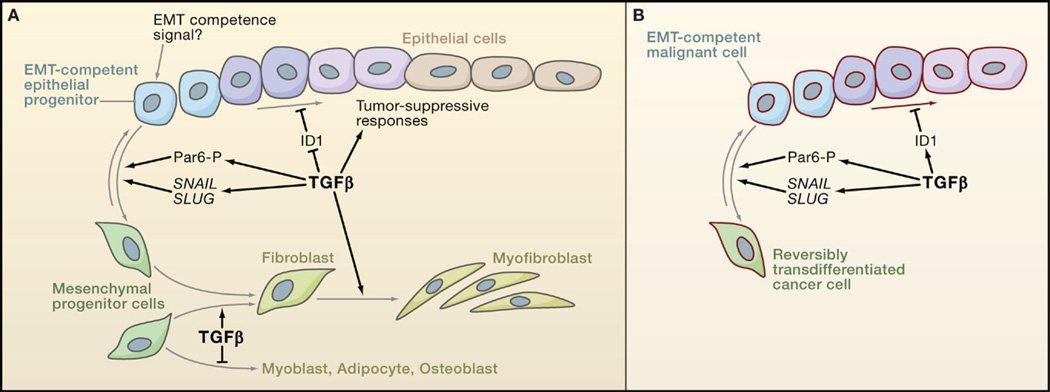

Cell Differentiation and Senescence

TGFβ and other members of its family have a major influence on cell lineage determination and terminal differentiation. Whereas certain effects of TGFβ on differentiation can be co-opted for tumor progression (see below), others suppress tumorigenesis by driving precursor cells into a less proliferative state. TGFβ promotes the differentiation of mesenchymal precursors into fibroblasts and myofibroblasts at the expense of adipocyte, myocyte, and osteoblast fates (Figure 6) (Derynck and Akhurst, 2007). BMP promotes differentiation of mesenchymal precursors toward the osteoblast lineage and of neural precursors into astroglia. BMP signaling in skin and intestinal epithelia is required for stem cell maintenance but also for progenitor cell differentiation (He et al., 2004; Kobielak et al., 2007). BMPR1A ablation studies suggest that when stem cells transit into a progenitor state, BMP interferes with Wnt signaling to promote differentiation. Failure of this mechanism could be the basis for intestinal polyp formation in JPS patients with BMPR1A mutations.

Figure 6. Anti- and Protumorigenic Effects of TGFβ on Cell Differentiation.

(A) TGFβ favors epithelial differentiation into less proliferative states partly through the downregulation of Inhibitor of Differentiation/DNA binding 1 (ID1). But because of as yet unknown determinants, epithelial progenitor cells can instead become competent to undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in response to TGFβ. TGFβ functions through the transcription factors SNAIL and SLUG and through phosphorylation of the cell-cell contact regulator Par6 to stimulate EMT. TGFβ also stimulates the differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells toward fibroblast and myofibroblast lineages, at the expense of adipocyte and musculoskeletal lineages.

(B) Carcinoma cells may avert differentiation into a less proliferative state by switching the ID1 response to TGFβ from repression to activation, as observed in breast cancer cells. Carcinoma progenitor cells that are competent to undergo EMT in response to TGFβ yield highly motile, invasive mesenchymal derivatives, whose presence in tumors is associated with metastatic dissemination.

TGFβ also modulates differentiation through the regulation of Id proteins (Inhibitor of Differentiation/DNA binding) that negatively regulate cell differentiation by interfering with prodifferentiation bHLH transcription factors (Ruzinova and Benezra, 2003). In mouse embryonic stem cells, BMP-activated Smad-Stat3 complexes induce ID1 expression to stimulate self-renewal (Ying et al., 2003). In epithelial and endothelial cells in culture, BMP stimulates and TGFβ downregulates ID1 expression (Kang et al., 2003a; Korchynskyi and ten Dijke, 2002) (Figure 5D). BMP-induced binding of Smad1 to the ID1 promoter supports transcriptional activation, whereas TGFβ signaling through Smad3 induces the expression of the repressor ATF3, which is then recruited by Smad3 to the ID1 promoter (Kang et al., 2003a). ID1 enhances Ras-driven mammary tumorigenesis in mice by bypassing senescence (Swarbrick et al., 2008). In a xenograft model using a Ras-transformed human breast epithelial cell line, TGFβ suppressed tumor formation by these cells through downregulation of ID1, thereby imposing a less proliferative phenotype (Tang et al., 2007). These findings suggest that ID1 downregulation mediates cell differentiation and senescence as tumor-suppressive responses to TGFβ.

Proapoptotic Mechanisms

In physiological settings, TGFβ triggers apoptosis depending on cell-autonomous and environmental factors whose molecular identity remains unknown. The nature of these determinants needs to be defined and replicated in model systems in order to properly delineate TGFβ proapoptotic mechanisms that suffer disruption in cancer. Although the mechanism of TGFβ-induced apoptosis in vivo remains to be established, candidates include several Smad-dependent and -independent mechanisms observed in cell lines (reviewed in Pardali and Moustakas, 2007). These mechanisms include the induction of the death-associated protein kinase DAPK, which triggered apoptosis in a hepatoma cell line, the signaling factor GADD45b, which triggered apoptosis in hepatocytes, and the death receptor FAS and the proapoptotic effector BIM, which triggered apoptosis in gastric carcinoma cell lines. Induction of the 5′ inositol phosphatase SHIP interfered with activation of the PI3K-Akt prosurvival pathway. Smad interaction with Akt and TGFβ receptor interactions with the p38 MAPK activator DAXX have also been proposed as mediators of proapoptotic effects.

Tumor Suppression through the Stroma

In addition to its direct growth-inhibitory effects on target cells, TGFβ can restrict epithelial cell proliferation and tumor formation by blocking the production of paracrine factors in stromal fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. These observations bring growing attention to the notable role of the stroma in tumor development.

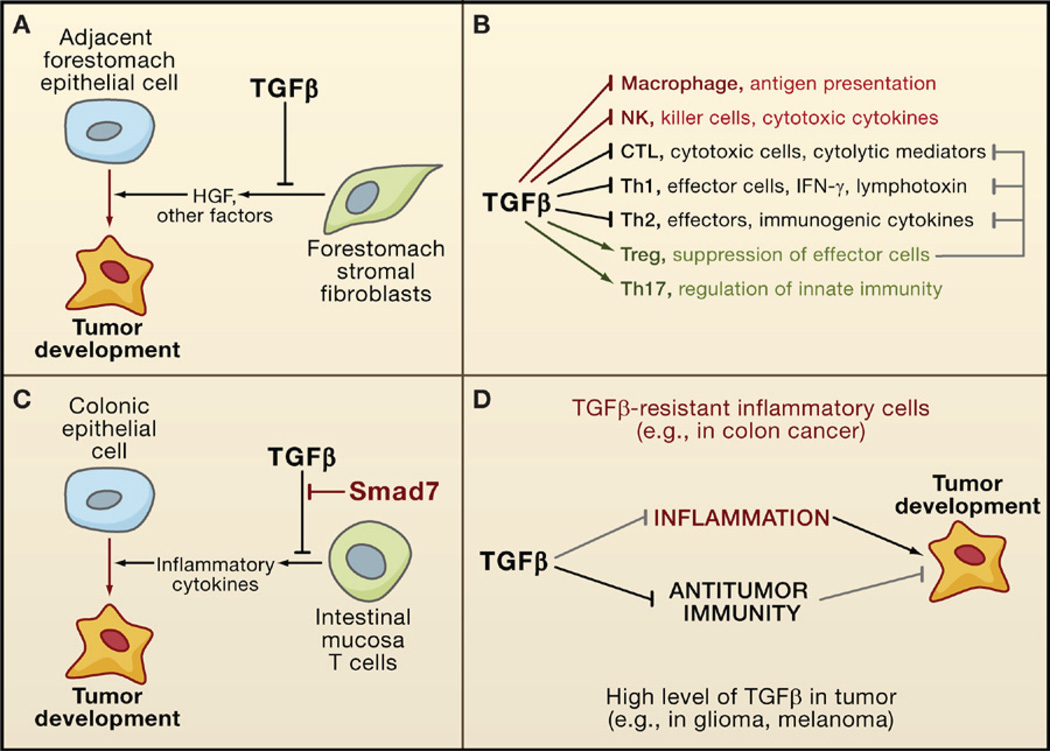

Suppression of Fibroblast-Derived Mitogens

Epithelial interactions with adjacent stroma are important in guiding tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis. A role for TGFβ in such interactions emerged from work in mice with defective TGFβ signaling in stromal fibroblasts. Expression of a dominant-negative TGFBRII transgene in the mammary stroma increased the lateral branching of adjacent mammary ducts. Building on this observation,Bhowmick et al. (2004) generated mice with a targeted deletion of TGFBRII in fibroblasts. Such loss of TGFβ signaling in the prostate and the forestomach resulted in hyperplasia of the adjacent epithelia with progression to prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and gastric squamous carcinoma, respectively (Figure 7A). These effects were accompanied by an elevated expression of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in the TGFBRII-defective fibroblasts and activation of the HGF receptor Met in adjacent epithelial cells. By constraining the expression of mitogenic factors in stromal fibroblasts, TGFβ limits the paracrine stimulation of epithelial proliferation and suppresses tumor development.

Figure 7. Anti- and Protumorigenic Effects of TGFβ in the Stroma.

(A) TGFβ suppresses tumor emergence in certain epithelial tissues (e.g., the forestomach epithelium) by inhibiting the production of cell survival and motility factors such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF).

(B) TGFβ acts as a major enforcer of immune tolerance by inhibiting the development and functions of nearly all major components of the innate (red) and adaptive (black) immune system. Some of these effects are exerted through the activation of regulatory T cells (Treg; green) that constrain the function of other lymphocytes (gray).

(C) By imposing limits on the inflammatory response, TGFβ can avert the protumorigenic effect that could derive from chronic inflammation, as observed in colonic epithelial cells. However, T cells in some patients with inflammatory bowel disease (a colon cancer-prone condition) overexpress Smad7 and are not sensitive to TGFβ.

(D) In some types of cancer, a defective TGFβ response in inflammatory cells can lead to excessive inflammation, favoring tumor progression. In other types of cancer, tumor-derived TGFβ can suppress antitumor immune responses, which also favors tumor progression.

Suppression of Tumorigenic Inflammation

TGFβ is a key suppressor of destructive immune and inflammatory reactions, as first shown by the lethal multifocal inflammatory disease arising in TGFβ1-deficient mice and mice with a conditional deletion of TGFBRII in the hematopoietic system (reviewed in Li et al., 2006; Rubtsov and Rudensky, 2007). Smad3-deficient mice also have a phenotype of impaired immune regulation with excessive expansion of T cell populations, defective mucosal immunity, and chronic inflammation. As an immunosuppressive cytokine, TGFβ inhibits the development, proliferation, and function of both the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune system. Targets of TGFβ include CD4+ effector T cells (Th1 and Th2), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), dendritic cells, NK cells, and macrophages (Figure 7B). Additionally, TGFβ stimulates the generation of regulatory T cells (Treg), which inhibit effector T cell functions, and IL17-producing Th17 cells, which regulate NK cells and macrophages.

By curtailing the activities of macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and effector T cells, TGFβ suppresses inflammation to promote immune tolerance. Tolerance is particularly important in the intestinal mucosa, where reactions to commensal flora and to food antigens must be restrained (Becker et al., 2006). Breakdown of mucosal immune tolerance underlies the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) that are associated with an increased risk for colon cancer. Malfunctions in TGFβ signaling are suspected to be a root cause of these conditions. TGFβ1-defective mice and Smad3-deficient mice develop precancerous colon lesions with submucosal inflammation, which frequently progress to colon carcinoma (Engle et al., 2002; Maggio-Price et al., 2006). Inflammation and tumor formation in these animals required their removal from a germ-free environment or infection with the bacteria Helicobacter. Remarkably, T cells isolated from colon samples of patients with inflammatory bowel disease are poorly responsive to TGFβ because of the expression of high levels of Smad7 (Monteleone et al., 2004) (Figure 7C). Dense infiltrates of proinflammatory cells are also present in the nonpolypous intestinal mucosa of JPS patients with SMAD4 germline mutations. Notably, the selective ablation of SMAD4 in the T cell compartment leads to a JPS-like phenotype in mice, which results in gastrointestinal tumors that are heavily infiltrated with plasma cells. In contrast, deletion of SMAD4 in the intestinal epithelium alone does not lead to spontaneous tumor formation (Kim et al., 2006; SMAD4+/− mice do develop intestinal tumors, but this requires a primed, APC-defective genetic background; Takaku et al., 1998). TGFβ can also suppress gastrointestinal inflammatory activity by stimulating the expression of the prostaglandin-degrading enzyme 15-PGDH, which antagonizes the proinflammatory action of COX2 (Yan et al., 2004).

Failure of Tumor-Suppressor Mechanisms

We have seen that mutational inactivation of core pathway components occurs in large subsets of colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, gastric, and head and neck carcinomas. However, breast cancers, prostate cancers, gliomas, melanomas, and hematopoietic neoplasias are a different story. These cancers preferentially disable the tumor-suppressive action of TGFβ by losing the tumor-suppressive arm of the signaling pathway. A striking example of this preference is provided by breast cancers with microsatellite instability, which rarely progress when TGFBRII is lost. TGFβ receptor mutations surely occur in these tumors, but the resulting clones must be at a disadvantage compared to clones that lose the tumor-suppressive arm of the TGFβ pathway.

Defective Cytostatic Gene Responses

Tumor-derived cell lines contain a variety of alterations that disable cytostatic Smad cofactors. However, some of these alterations may be the result of adaptation to growth in vitro because they are also found in certain cell lines derived from normal tissue. To obviate this concern, recent studies have focused on short-term cultures of patient-derived cancer cell samples. Breast cancer cells from pleural fluids of patients with metastatic disease expressed normal TGFβ receptor and Smad functions but showed a partial or complete loss of cytostatic response to TGFβ in all cases (Gomis et al., 2006b). Half of the samples in this study lacked p15INK4b induction and c-MYC repression despite retaining other TGFβ gene responses. This defect was associated with overexpression of the dominant-negative C/EBPβ isoform LIP, which binds and inhibits the transcriptional active isoform LAP (Figure 5A). Independent studies have established an association between a high LIP:LAP ratio and tumor aggressiveness in breast cancer (Zahnow et al., 1997).

Patient-derived metastatic breast cancer cells were also uniformly aberrant in the ID1 response to TGFβ, which was induced instead of repressed (Padua et al., 2008). ID1 expression is part of a lung metastasis gene-expression signature that is associated with relapse in estrogen receptor negative (ER−) breast cancer patients (Minn et al., 2005). In xenograft assays in mice using human breast cancer cell lines, the proteins Id1 and Id3 were essential for tumor reinitiation after the cells entered the lung parenchyma (Gupta et al., 2007). Therefore, the ID1 response to TGFβ switches from tumor suppressive to prometastatic in breast cancer.

Loss of Cytostatic Genes

A subset of gliomas sustain homozygous deletion of p15INK4b, eliminating this mediator of TGFβ tumor-suppression action (Jen et al., 1994). The p15INK44b locus on chromosome 9p21 encodes two additional cell cycle inhibitors, p16INK4a and ARF, whose functional and clinical relevance as tumor suppressors is well established. A tumor-suppressor role for p15INK4b has been demonstrated in mouse models, in which ablation of p15INK4b increased the rate and diversity of tumors that develop in mice that are null for p16INK4a or for p16INK4a and ARF (Krimpenfort et al., 2007). Loss of p15INK4b in the mice specifically promoted the emergence of skin squamous cell and basal carcinomas, as well as intestinal carcinomas. Thus, deleterious mitogenic signals may trigger tumor-suppressor responses by activating p16INK4a through internal sensors and by activating p15INK4b through TGFβ (Figure 5C). A loss of p15INK4b would weaken TGFβ tumor-suppression activity, which, combined with a loss of p16INK4a, would lead to tumor progression. A loss of responsiveness to TGFβ may also be embedded in the pleiotropic consequences of oncogene activation. For example, oncogenic Ras signaling may inhibit Smads through linker phosphorylation, whereas the overexpression c-MYC or Cyclin D1 in certain cancers may blunt the effect of TGFβ-induced CDK inhibitors.

Tumorigenic Effects of TGFβ: Tumor Growth, Invasion, and Immune Evasion

Cancer cells that lose the tumor-suppressive arm of the TGFβ pathway accrue tumorigenic effects that directly enhance tumor growth and invasion. However, regardless of how they avert the tumor-suppressive action, cancer cells can benefit from tumor-derived TGFβ by using it as a shield against antitumor immunity.

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a well-coordinated process during embryonic development and a pathological feature in neoplasia and fibrosis (Thiery, 2003). Cells undergoing EMT lose expression of E-cadherin and other components of epithelial cell junctions. Instead, they produce a mesenchymal cell cytoskeleton and acquire motility and invasive properties. EMT is key in gastrulation and in the genesis of the neural crest, the somites, the heart, and craniofacial structures. It is driven by a set of transcription factors including the zinc-finger proteins Snail and Slug, the bHLH factor Twist, the zinc-finger/homeodomain proteins ZEB-1 and -2, and the forkhead factor FoxC3.

The competence of epithelial precursor cells to undergo EMT becomes manifest in response to cues that prominently feature TGFβ (Figure 6A). As such, TGFβ-induced EMT is observed in transformed epithelial progenitor cells with tumor-propagating ability (Figure 6B) (Mani et al., 2008). EMT-like processes contribute to tumor invasion and dissemination owing to the cell junction-free, motile phenotype that they confer. Carcinoma cells with mesenchymal traits have been observed in the invasion front of carcinomas and may reflect a series of interconnected features: that carcinomas are propagated by transformed progenitor cells, that progenitor cells are competent to undergo EMT, that EMT is triggered by cues at the invasion front, and that EMT augments the disseminative capacity of these cells. That said, not all cells that undergo EMT are tumorpropagating cells, and not all tumor-propagating cells are necessarily competent to undergo EMT.

TGFβ is a potent inducer of EMT (first reported in mouse heart formation and palate fusion, in some mammary cell lines, and in mouse models of skin carcinogenesis; Derynck and Akhurst, 2007; Thiery, 2003). A role of TGFβ-induced EMT in human cancer is suggested by the gene expression analysis of tumor-propagating breast cancer cell populations expressing the cell surface markers CD44+/CD24lo(Shipitsin et al., 2007). The common gene expression pattern of these cells from different cancer patients suggested the presence of an active TGFβ pathway. Furthermore, treatment with a TβR-I kinase blocker induced these cells to adopt a more epithelial phenotype. Thus, CD44+/CD24lo breast cancer cells may represent a tumor cell population that has undergone EMT. In human carcinomas, cells with features characteristic of EMT have been observed in the invasion front, a location that is rich in stromal TGFβ and other cytokines that may cooperate in EMT induction.

TGFβ promotes EMT by a combination of Smad-dependent transcriptional events and Smad-independent effects on cell junction complexes. Smad-mediated expression of HMGA2 (high-mobility group A2) induces expression of Snail, Slug, and Twist (Thuault et al., 2006). Independent of Smad activity, TβRII-mediated phosphorylation of Par6 promotes the dissolution of cell junction complexes (Ozdamar et al., 2005). In mouse tumors and cell lines, TGFβ-induced EMT is Smad dependent and enhanced by Ras signaling (Derynck and Akhurst, 2007). TGFβ can also enhance cell motility by cooperating with HER2 signals, as observed in breast cancer cells overexpressing HER2 (Seton-Rogers et al., 2004).

Myofibroblast Generation

The mobilization of myofibroblasts is another significant component of the proinvasive action of TGFβ. TGFβ stimulates the generation of myofibroblasts from mesenchymal precursors (De Wever and Mareel, 2003) (Figure 6). Myofibroblasts have features of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells and are highly motile. Their presence in tumor stroma, partly as what are called “cancer-associated fibroblasts,” facilitates tumor development (Allinen et al., 2004; De Wever and Mareel, 2003). In culture, myofibroblasts guide the invasion of colon cancer cells into a collagen matrix, a process that requires the continuous presence of TGFβ. Myofibroblasts produce matrix metalloproteases, cytokines (e.g., IL-8, VEGF), and chemokines (e.g., CXCL12) to promote cancer cell proliferation, tumor invasion, and neoangiogenesis.

Production of Autocrine Mitogens

TGFβ can promote tumor cell proliferation by stimulating the production of autocrine mitogenic factors. The loss of the TGFβ tumor suppressor arm in glioma, owing to PI3K hyperactivation, loss of p15INK4b, or mutational inactivation of RB, allows glioma cells to profit from TGFβ-induced mitogen production. Glioma cell cultures proliferate in response to TGFβ through the induction of platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGF-B) (Jennings and Pietenpol, 1998). The competence of glioma cells to express PDGF-B in response to TGFβ depends on the methylation state of the PDGF-B gene (Bruna et al., 2007). Hypomethylation of PDGF-B enables TGFβ- and Smad-dependent transcription induction and is associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients. Epigenetic regulation of the PDGF-B gene therefore dictates the ability of TGFβ to stimulate glioma cell proliferation.

Evasion of Immunity

When the immunosuppressive effects of TGFβ outweigh the tumor-suppressive benefits of its anti-inflammatory action, a net protumorigenic advantage may result (Figure 7D). T cell-specific expression of a dominant-negative form of TGFBRII prevented the growth of inoculated melanoma or thymoma in mice (Gorelik and Flavell, 2000). CD8+ T cells were identified as a critical target of TGFβ in this model. TGFβ acting through the Smad pathway in CD8+ CTLs represses the production of cytolytic factors including the pore-forming protein perforin, the caspase-activating secreted factors granzyme A and B, and the proapoptotic cytokines Fas-ligand and IFN-γ (Thomas and Massagué, 2005). In human glioma patients, TGFβ decreases the expression of the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D in CD8+ T cells and NK cells and represses the expression of the NKG2D ligand MICA (Friese et al., 2004). Knockdown of TGFβ synthesis in a glioma cell line prevented NKG2D downregulation and enhanced glioma cell killing by CTL and NK cells. Thus, glioma development may thrive on both the immunosuppressive action of TGFβ and the TGFβ-induced production of PDGF.

TGFβ in Distal Metastasis

In addition to the role of TGFβ in local invasion, growing evidence implicates TGFβ in the promotion of distal metastasis. Metastasis proceeds through a series of steps whereby cancer cells enter the circulatory system, disseminate to distal capillary beds, enter a parenchyma by extravasation, adapt to the new host microenvironment, and eventually grow into lethal tumor colonies in those distal organs (Fidler, 2003; Gupta and Massagué, 2006). Metastasis follows characteristic organ distribution patterns that reflect distinct colonization aptitudes of cancer cells from different origins, different tumor-efferent circulation patterns, and distinct compatibilities between disseminated cells and the organ that they encounter. Beyond the proliferative, survival, and invasive functions of a malignant state, metastasis requires extravasation and colonization functions that come into play once malignant cells disseminate. Such functions may be acquired in the primary tumor but become selected mainly during seeding and colonization of largely hostile tissue microenvironments. Studies in model systems have described a broad range of potential and sometimes contradictory TGFβ effects on metastasis. Those with demonstrated clinical relevance are highlighted here.

TGFβ and Metastatic Relapse

Clinical correlations between pre- or postoperative plasma levels of TGFβ and metastatic disease have been reported in many studies on colorectal, prostate, bladder, breast, pancreatic, or renal cancers and on myeloma and lymphoma. A high level of TGFβ1 immunostaining in infiltrating breast carcinoma has long been associated with metastasis (Dalal et al., 1993). Indeed, in ER− breast tumors, low expression of TGFBRII is associated with a favorable outcome (Buck et al., 2004). Furthermore, the treatment of mammary tumor-bearing mice with radiation or chemotherapy caused an increase in circulating TGFβ1 levels and lung metastasis, which could be prevented by administration of a TGFβ blocker (Biswas et al., 2007). These observations point at a potential link between TGFβ production and metastatic disease. However, TGFβ signaling has shown disparate effects on metastasis in mouse models. The expression of activated a TGFBRI transgene in mouse mammary tumors driven by ErbB2/HER2 oncogenes enhanced metastasis of these tumors to the lungs (Muraoka et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 2003). However, a targeted deletion of TGFBRII in PyMT-driven tumors did the same (Forrester et al., 2005). Similarly, a dominant- negative form of TGFBRII inhibited metastasis of human prostate cancer cells when implanted in the mouse prostate (Zhang et al., 2005) but promoted metastasis as a transgene in mouse prostate tumors driven by SV40 large T antigen (Tu et al., 2003). How can this contextual role of TGFβ be explained at the molecular level and ascertained in human cancer?

One possible approach is based on classifying human tumors according to their TGFβ response status and searching for associations with clinical outcome. To this end, a TGFβ gene response signature was defined using human epithelial cell lines and turned into a bioinformatics classifier tool (Padua et al., 2008). In different clinical cohorts, approximately 40% of human breast tumors show a TGFβ gene response signature, and this status coincided with a high expression of TGFβ1, TGFβ2, LTBP1, SMAD3, and SMAD4. Interestingly, a TGFβ gene response signature status was associated with lung relapse but not bone relapse. It was also associated with ER− but not ER+ primary tumors. The contextual role of TGFβ in this case is a function of the tumor subtype (ER− versus ER+ breast tumors) and the site of relapse (lungs versus bones). Of course, this argues against a generic, noncontextual effect of TGFβ (e.g., increased cancer cell motility or invasiveness) playing a major role in breast cancer metastasis.

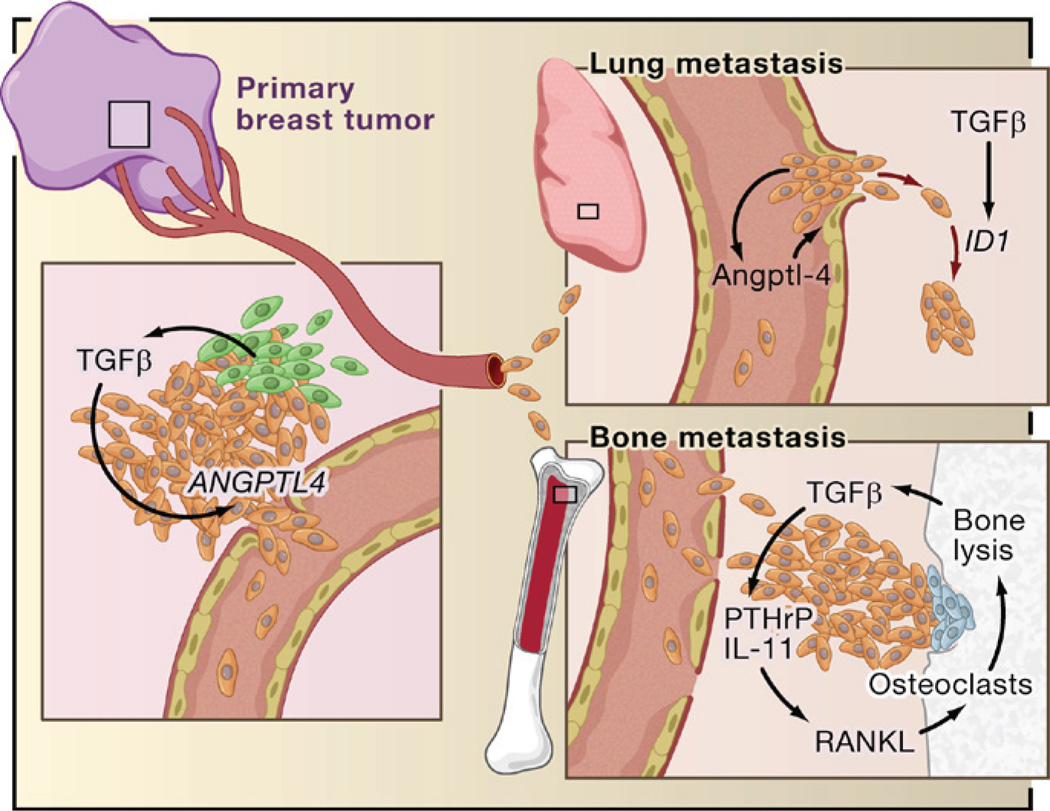

Priming Tumor Cells for Distal Metastasis

Investigation of the biologically selective, context-dependent mechanism implied by these observations led to the finding that TGFβ in the breast tumor microenvironment primes cancer cells for subsequent pulmonary metastasis (Padua et al., 2008). Blocking TGFβ signaling with a dominant-negative form of TGFBRI or SMAD4 knockdown in an ER− human breast cancer cell line decreased the ability of these cells to generate lung metastases when implanted as mammary tumors in mice. Central to this process was the induction of angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) by TGFβ via the Smad signaling pathway. TGFβ in the primary tumor induced the expression of Angptl4 in departing cancer cells, empowering these cells to disrupt lung capillary walls and seed pulmonary metastases (Figure 8). Tumor cell-derived Angptl4 disrupted vascular endothelial cell-cell junctions, increased the permeability of lung capillaries, and facilitated the transendothelial passage of tumor cells. This function of Angptl4 could explain why it does not provide an advantage for seeding bone metastasis: The capillary walls in the bone marrow are already fenestrated to facilitate the passage of hematopoietic cells. TGFβ-induced Angptl4 does not act alone, but functions in the context of other prometastatic genes that constitute a lung metastasis signature (LMS) in ER− tumors (Minn et al., 2005). ER− breast tumors that are positive for both the TGFβ gene response signature and LMS are associated with the highest risk of relapse through lung metastases. Thus, the TGFβ gene response signature provides not only a tool to discern the contextual role of TGFβ in different tumor subtypes but also a potential way to select patients for TGFβ blocking therapy.

Figure 8. Roles of TGFβ in Breast Cancer Metastasis.

Based on recent reports, TGFβ derived from infiltrating mesenchymal or myeloid precursor cells (green) or from the cancer cells themselves (brown) in ER− breast tumors induces the expression of genes including Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4; primary breast tumor inset). Cancer cells entering the circulation with elevated Angptl4 production have an advantage in seeding lung metastasis because of this cytokine’s ability to disrupt vascular endothelial junctions when the cells lodge in lung capillaries (lung metastasis inset). After entering the pulmonary parenchyma, ER− breast cancer cells may respond to local TGFβ with induction of Inhibitor of Differentiation/DNA binding 1 (ID1), which acts in this context as a tumor-reinitiating gene. The entry of circulating tumor cells into the bone marrow does not benefit from Angptl4 because these capillaries are naturally fenestrated to allow the constant passage of cells (bone metastasis inset). However, TGFβ released by osteoclasts (blue) from rich stores in the bone matrix acts on the growing cancer cells to stimulated the production of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and interleukin- 11. These factors act on osteoblasts to release RANK ligand (RANKL) and other mediators of osteoclast moblization, perpetuating the osteolytic metastasis cycle.

TGFβ and Metastatic Colonization

Once distant metastases take hold, local production of TGFβ can profoundly affect the growth of these lesions. In mouse models, the osteoclastic activity triggered by cancer cells in the bone marrow leads to the release of TGFβ from rich bone matrix stores. TGFβ may then stimulate the cancer cells to release osteolytic cytokines, thus perpetuating a prometastatic cycle (Kingsley et al., 2007) (Figure 8). Metastatic breast cancer cells in the bone microenvironment are engaged in Smad-dependent transcription, as shown by a noninvasive imaging reporter in mice (Kang et al., 2005). Indeed, blocking TGFβ signaling by overexpressing the inhibitor Smad7 or a dominant-negative form of the TGFβ receptor deters the formation of osteolytic metastases by human breast cancer (Yin et al., 1999), melanoma (Javelaud et al., 2007), and renal carcinoma cell line xenografts (Kominsky et al., 2007). One of the mediators of TGFβ osteolytic action is parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) (Kingsley et al., 2007). TGFβ stimulates PTHrP secretion without appearing to increase PTHrP mRNA levels. PTHrP stimulates the production of RANK ligand (RANKL) in osteoblasts, which in turn promotes the differentiation of osteoclast precursors and bone resorption. Administration of anti-PTHrP neutralizing antibodies inhibits TGFβ-dependent osteolytic bone metastasis in mice (Kakonen et al., 2002).

Additional mediators include a set of genes that modulate bone metastasis in mice by human ER− breast cancer cells (Kang et al., 2003a). Among these genes, interleukin-11 (IL-11) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) are TGFβ target genes. CTGF is an extracellular mediator of invasion and angiogenesis, whereas IL-11 stimulates the production of the osteoclastogenic factors RANKL and GM-CSF in osteoblasts. Induction of IL-11 and CTGF expression by TGFβ is mediated by the Smad pathway (Kang et al., 2005) and has been confirmed in malignant cells isolated from patients with metastatic breast cancer (Gomis et al., 2006b).

The role of TGFβ in metastatic colony expansion may not be limited to bone metastasis. A majority of metastases to lung, liver, and brain in breast cancer patients stain positive for phospho-Smad2, suggesting a widespread activation of this pathway in metastasis by locally released TGFβ. In breast cancer cells that have entered the pulmonary parenchyma, TGFβ may facilitate tumor reinitiation through an aberrant induction of ID1 expression (Padua et al., 2008).

Therapeutically Targeting TGFβ: Challenges and Opportunities

With growing clinical evidence that TGFβ acts as a tumor-derived immunosuppressor, an inducer of tumor mitogens, a promoter of carcinoma invasion, and a trigger of prometastatic cytokine secretion, there is growing interest in TGFβ as a therapeutic target. In spite of the sobering concerns that apply to targeting a pleiotropic cytokine pathway, anti- TGFβ compounds have been developed that show efficacy in preclinical studies, and clinical trials with several of these compounds are underway (for more detailed commentaries, see Arteaga, 2006; Bierie and Moses, 2006; Wrzesinski et al., 2007). Inhibitors of the TGFβ pathway developed to date encompass several classes. These include inhibitors of TGFβ production (antisense oligonucleotides) that can be engineered into immune cells or delivered directly into tumors. They also include inhibitors of ligand-receptor interactions such as anti-TGFβ antibodies, anti-receptor antibodies, TGFβ-trapping receptor ectodomain proteins, and small-molecule inhibitors that target TGFβ receptor kinases. Members of each of these inhibitor classes have entered clinical trials for efficacy not only against cancers (glioma, melanoma, breast cancer) but also against fibrosis, scarring, and other conditions that result from excessive TGFβ activity.

Therapeutic targeting of the TGFβ pathway in tumors such as glioma, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma is based on the rationale that TGFβ exerts strong immunosuppressive effects in these tumors. Thus, blocking TGFβ function might empower the immune system against the tumor. Blocking TGFβ action may also have additional tumor-specific benefits. For example, TGFβ inhibition in gliomas may curtail the production of autocrine survival factors, such as PDGF. Blocking TGFβ in ER− breast cancer, on the other hand, might prevent primary or metastatic tumors from seeding and reseeding metastasis. Finally, in osteolytic bone metastasis, blocking TGFβ might interrupt the cycle of TGFβ-induced osteoclastogenic factors and halt tumor growth. Although these examples show the great potential of the pathway as a therapeutic target, there are potential negative consequences, as well. Inhibition of TGFβ might lead to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune reactions, although this problem has not yet materialized in the preclinical or clinical trials of systemic TGFβ blockers. Inhibition of TGFβ receptor function might also lead to runaway compensatory mechanisms by other activators of the Smad pathway, similar to what occurs in individuals with inactivating mutations in TGFBRI or TGFBRII (Loeys et al., 2006). Lastly, inhibition of TGFβ signaling might enhance the progression of premalignant lesions. Of course, this would be a lesser concern in cancer patients whose malignancies are thriving on TGFβ. Reassuringly however, systemic administration of TGFβ blockers has not been reported to increase spontaneous tumor development in animal models.

Progress in delineating the protumorigenic effects and mechanisms of TGFβ in specific tumor types and in different stages of cancer progression is essential for determining when and how anti-TGFβ targeted therapy might be feasible. The recent development of TGFβ gene expression prognostic tools and TGFβ response biomarkers may provide the means to select patients for anti-TGFβ intervention in addition to a way to assess effective pharmacological targeting of this pathway. Analysis of the TGFβ signaling pathway in experimental models and human samples has brought much needed clarity to the role and relevance of TGFβ in human cancer, bringing this once obscure problem to the cusp of clinical tractability.

Acknowledgments

I thank all current and former members of my laboratory for their dedication and S. Acharyya, G. Gupta, D. Nguyen, D. Padua, S. Tavazoie, and A. Zaromytidou for their comments. J.M. is supported by the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allinen M, Beroukhim R, Cai L, Brennan C, Lahti-Domenici J, Huang H, Porter D, Hu M, Chin L, Richardson A, et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga CL. Inhibition of TGFbeta signaling in cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft GS, Yang X, Glick AB, Weinstein M, Letterio JL, Mizel DE, Anzano M, Greenwell-Wild T, Wahl SM, Deng C, Roberts AB. Mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated wound healing and an impaired local inflammatory response. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:260–266. doi: 10.1038/12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeesy N, Cheng KH, Berger JH, Chu GC, Pahler J, Olson P, Hezel AF, Horner J, Lauwers GY, Hanahan D, DePinho RA. Smad4 is dispensable for normal pancreas development yet critical in progression and tumor biology of pancreas cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3130–3146. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Fantini MC, Neurath MF. TGF-beta as a T cell regulator in colitis and colon cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, Washington MK, Neilson EG, Moses HL. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick NA, Ghiassi M, Bakin A, Aakre M, Lundquist CA, Engel ME, Arteaga CL, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation through a RhoAdependent mechanism. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:27–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: The molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Chytil A, Washington K, Romero-Gallo J, Gorska AE, Wirth PS, Gautam S, Moses HL, Grady WM. Transforming growth factor beta receptor type II inactivation promotes the establishment and progression of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4687–4692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Guix M, Rinehart C, Dugger TC, Chytil A, Moses HL, Freeman ML, Arteaga CL. Inhibition of TGF-beta with neutralizing antibodies prevents radiation-induced acceleration of metastatic cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1305–1313. doi: 10.1172/JCI30740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleuming SA, He XC, Kodach LL, Hardwick JC, Koopman FA, Ten Kate FJ, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP, Offerhaus GJ, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling suppresses tumorigenesis at gastric epithelial transition zones in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8149–8155. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick P, Carvajal-Carmona L, Pittman AM, Webb E, Howarth K, Rowan A, Lubbe S, Spain S, Sullivan K, Fielding S, et al. A genome- wide association study shows that common alleles of SMAD7 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1315–1317. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruna A, Darken RS, Rojo F, Ocana A, Penuelas S, Arias A, Paris R, Tortosa A, Mora J, Baselga J, Seoane J. High TGFbeta- Smad activity confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and promotes cell proliferation depending on the methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MB, Fritz P, Dippon J, Zugmaier G, Knabbe C. Prognostic significance of transforming growth factor beta receptor II in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:491–498. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0320-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti JM, Ebina KN, Matsuo SE, Martins L, Maciel RM, Kimura ET. Expression of Smad4 and Smad7 in human thyroid follicular carcinoma cell lines. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2003;26:516–521. doi: 10.1007/BF03345213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CR, Kang Y, Siegel PM, Massagué J. E2F4/5 and p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFbeta receptor to c-myc repression. Cell. 2002;110:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal BI, Keown PA, Greenberg AH. Immunocytochemical localization of secreted transforming growth factor-beta 1 to the advancing edges of primary tumors and to lymph node metastases of human mammary carcinoma. AmJPathol. 1993;143:381–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Lagna G, Hata A. SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature. 2008;454:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature07086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis EM, Kuroda H. Dorsal-ventral patterning and neural induction in Xenopus embryos. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:285–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.011403.154124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. J. Pathol. 2003;200:429–447. doi: 10.1002/path.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Akhurst RJ. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descargues P, Sil AK, Sano Y, Korchynskyi O, Han G, Owens P, Wang XJ, Karin M. IKKalpha is a critical coregulator of a Smad4-independent TGFbeta-Smad2/3 signaling pathway that controls keratinocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2487–2492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712044105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy SC, Mariani A, Reinholz MM, Keeney GL, Spelsberg TC, Podratz KC, Janknecht R. Overexpression of the TGF-beta antagonist Smad7 in endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;96:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Zacchigna L, Cordenonsi M, Soligo S, Adorno M, Rugge M, Piccolo S. Germ-layer specification and control of cell growth by Ectodermin, a Smad4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2005;121:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle SJ, Ormsby I, Pawlowski S, Boivin GP, Croft J, Balish E, Doetschman T. Elimination of colon cancer in germ-free transforming growth factor beta 1-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6362–6366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: The ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foletta VC, Lim MA, Soosairajah J, Kelly AP, Stanley EG, Shannon M, He W, Das S, Massagué J, Bernard O. Direct signaling by the BMP type II receptor via the cytoskeletal regulator LIMK1. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester E, Chytil A, Bierie B, Aakre M, Gorska AE, Sharif-Afshar AR, Muller WJ, Moses HL. Effect of conditional knockout of the type II TGF-beta receptor gene in mammary epithelia on mammary gland development and polyomavirus middle T antigen induced tumor formation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2296–2302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]