Abstract

Four oligofructans (neokestose, 1-kestose, nystose, and an un-identified pentofructan) occurred in the vascular tissues and phloem sap of mature leaves of Agave deserti. Fructosyltransferases (responsible for fructan biosynthesis) also occurred in the vascular tissues. In contrast, oligofructans and fructosyltransferases were virtually absent from the chlorenchyma, suggesting that fructan biosynthesis was restricted to the vascular tissues. On a molar basis, these oligofructans accounted for 46% of the total soluble sugars in the vascular tissues (sucrose [Suc] for 26%) and for 19% in the phloem sap (fructose for 24% and Suc for 53%). The Suc concentration was 1.8 times higher in the cytosol of the chlorenchyma cells than in the phloem sap; the nystose concentration was 4.9 times higher and that of pentofructan was 3.2 times higher in the vascular tissues than in the phloem sap. To our knowledge, these results provide the first evidence that oligofructans are synthesized and transported in the phloem of higher plants. The polymer-trapping mechanism proposed for dicotyledonous C3 species may also be valid for oligofructan transport in monocotyledonous species, such as A. deserti, which may use a symplastic pathway for phloem loading of photosynthates in its mature leaves.

Plant growth depends on the supply of photosynthates via the phloem to sink organs. The process of photosynthate delivery from photosynthetic cells to the phloem of source organs (phloem loading) is an important determinant of such growth, and numerous studies have been conducted to understand its mechanism (Giaquinta, 1983; van Bel, 1993). In species for which Suc is the only transported sugar, phloem loading may occur by co-transport of Suc and protons from the apoplast (i.e. apoplastic loading; Giaquinta, 1983; van Bel, 1993; Grusak et al., 1996). For other species, however, RFO and other carbohydrates in addition to Suc are transported in the phloem (Turgeon et al., 1975; Ziegler, 1975; Fisher, 1986; Flora and Madore, 1993). In many of these species, such as Coleus blumei, Cucurbita pepo, and Olea europaea, phloem loading is not sensitive to the inhibitor of active Suc transport, p-chloromercuriphenylsulfonic acid; therefore, such a mechanism of apoplastic phloem loading may not apply to such species. Because the Suc concentration in the photosynthetic cells is often lower than or similar to that in the phloem for these species, symplastic phloem loading of Suc via plasmodesmata would also not occur.

To resolve this dilemma of symplastic phloem loading, Turgeon (1991) has proposed a polymer-trapping model for loading of Suc and RFO, in which Suc in the photosynthetic cells diffuses via plasmodesmata down its concentration gradient to the bundle-sheath cells and then to intermediary cells (specialized companion cells), where raffinose and stachyose are synthesized. Raffinose and stachyose then diffuse from the intermediary cells to sieve tubes down their concentration gradients but cannot diffuse back into bundle-sheath cells because the channel size of plasmodesmata between intermediary cells and bundle-sheath cells is too small for their passage. This polymer-trapping model is supported by ultrastructural studies, the concentration of RFO in the intermediary cells, immunolocalization of enzymes responsible for RFO synthesis, and other physiological evidence (van Bel, 1993; Haritatos and Turgeon, 1996). However, it is not clear whether such a model can also apply to species that transport oligosaccharides other than RFO (such as fructans) or to monocotyledonous species.

Fructans are soluble polymers of Fru with a terminal Glc residue. They function as the main storage carbohydrates in 15% of flowering plant species, including many economically important crops (Pollock and Cairns, 1991; Pilon-Smits et al., 1996; Wiemken et al., 1996). Fructans also play roles in osmoregulation during drought (Spollen and Nelson, 1994; Wiemken et al., 1996) and can act as protectants against dehydration imposed by drought or freezing (Wiem-ken et al., 1996). Despite the important functions and wide distribution of oligofructans in flowering plants, virtually no information is available concerning oligofructan transport in higher plants.

Fructans are synthesized and stored in the stems of agaves (Aspinall and Gupta, 1959; Dorland et al., 1977; Bhatia and Nandra, 1979). The main function of fructans in the stems of such CAM plants is storage, as for C3 and C4 plants, and they may also act as osmoprotectants during drought. However, it is unknown whether fructans occur in the phloem of agaves. When we studied source-sink photosynthate partitioning for the CAM species Agave deserti, preliminary observations indicated that oligofructans occur in the phloem sap and vascular tissues of mature leaves. Such findings raise important questions about where these oligofructans are synthesized and how they are loaded into the phloem of mature leaves. For example, is the phloem loading of photosynthate apoplastic or symplastic?

The present study was initiated to determine the cellular site(s) for oligofructan biosynthesis and distribution and to test whether the polymer-trapping model (Turgeon, 1991) can also explain phloem loading of oligofructans in mature source leaves of the monocotyledon A. deserti. Thus, the distribution of mono- and oligosaccharides among different tissues of mature source leaves of A. deserti was examined to see whether oligofructans are specifically located in the phloem. The activities of enzymes responsible for fructan biosynthesis and hydrolysis were analyzed to determine the site(s) of fructan biosynthesis. The concentration gradients of mono- and oligosaccharides along the phloem-loading pathways from photosynthetic cells to the sieve tubes/companion cells were estimated to establish a possible loading mechanism for photosynthates in mature leaves of A. deserti.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty plants of Agave deserti Engelm. (Agavaceae) with 10 to 12 unfolded leaves averaging 28 cm in length were maintained in 14-L pots in a greenhouse at the University of California, Los Angeles. The mean total daily PPFD was 38 mol m−2 d−1, corresponding to a mean instantaneous value of 800 μmol m−2 s−1, and the daily maximum/minimum air temperatures averaged 28/16°C, respectively (North and Nobel, 1995). The plants were watered twice weekly with 0.1-strength Hoagland solution. Two months before the experiments, the plants were transferred to Conviron E-15 environmental growth chambers (Controlled Environments, Pembina, ND) with daily maximum/minimum air temperatures of 25/15°C, respectively. The photoperiod was 12 h, with a total daily PPFD of about 35 mol m−2 d−1. The plants were again watered twice weekly with 0.1-strength Hoagland solution. Such conditions are near the optimum for the growth of A. deserti (Nobel, 1988).

Tissue Harvest and Phloem Sap Collection

Mature leaves of A. deserti have chlorenchyma layers about 1 mm thick on both the upper and lower surfaces, with 1 to 2 mm of water-storage parenchyma in between, which allows for ready separation and collection of these two tissues. To assess diurnal changes of carbohydrates and malate in the chlorenchyma and in the water-storage parenchyma, 0.1 to 0.5 g of each tissue was harvested individually at various times of the day from the middle of mature source leaves of A. deserti using a razor blade. One-half of the harvested chlorenchyma or water-storage parenchyma was immediately frozen using dry ice and stored at −70°C, and the other half was dried at 80°C for 48 h to determine water content.

To obtain the vascular tissues, which in mature leaves occur as longitudinal veins extending from the leaf base to the tip without direct lateral vascular connections, sections with a width of about 1 mm were cut transversely across the middle of mature leaves. These sections, which contained the chlorenchyma, water-storage parenchyma, and vascular tissues, were frozen on dry ice and then dehydrated in a freeze-drying system (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) prior to storage at −70°C. A syringe needle of about 0.35 mm in diameter was inserted into the vascular strand area, which is readily visible under a stereomicroscope. Cores of vascular tissues, which were contaminated with a small amount of chlorenchyma and water-storage parenchyma, were collected by repeating such insertions and were weighed with a microbalance (ATI Cahn, Boston, MA). The dissected vascular tissues were stored at −70°C for measurements of metabolites and enzyme activities.

Phloem sap was collected with severed stylets of the scale insect Ovaticoccus californicus McKenzie, which naturally infests mature leaves of A. deserti, using a method similar to that developed for Opuntia ficus-indica (Wang and Nobel, 1995). Colonies of the insects that infested the middle region of mature leaves were gently wiped away with tissue paper soaked in 80% ethanol, leaving the severed stylets protruding from the leaf surface, and mineral-oil-filled wells were constructed covering the areas containing the severed stylets. Phloem sap was collected once every 2 to 3 h to minimize microorganism contamination. In many cases, phloem sap exuded naturally from the leaf surfaces that may have been previously punctured by the insects; such droplets of semidry phloem sap were also collected.

Chemical Analysis of Metabolites

To extract solutes, the frozen samples of the chlorenchyma or water-storage parenchyma were pulverized together with dry ice, ground in 0.5 mL of methanol:chloroform:water (12:5:3, v/v), and extracted at 25°C with 5 mL of distilled water. After the samples were heated to 95°C for 3 min to inactivate enzymes and then centrifuged, the decanted supernatant was passed through C18 sample preparation cartridges (Alltech Associates, Deerfield, IL) presaturated with distilled water to remove lipophilic materials; the eluate was further cleaned by passage through a 0.2-μm nylon filter. The final filtrate was collected for metabolite analysis. To measure starch content (Wang and Nobel, 1996), the insoluble portions of tissue extract were resuspended and then centrifuged three times with methanol:chloroform:water (12:5:3, v/v) and twice with distilled water to remove pigments, lipids, and remaining solutes. The remaining precipitates were mixed with 2 mL of distilled water and then heated at 100°C for 2 h to suspend the starch, which was hydrolyzed with amyloglucosidase (EC 3.2.1.3) at 55°C overnight; the released Glc was quantified using Glc oxidase (EC 1.1.3.4; Sturgeon, 1990). Soluble proteins in the chlorenchyma or water-storage parenchyma were also extracted at 0 to 2°C, according to procedures developed for O. ficus-indica (Wang and Nobel, 1996).

The metabolites in the dissected vascular tissues of freeze-dried samples were extracted at 60°C with 0.2 mL of HPLC grade water for 30 min. The supernatant extracted from the sections was then passed through 50 μL of the C18 sample-preparation cartridge material and a 0.2-μm nylon filter. Soluble proteins in the vascular tissues were extracted at 0 to 2°C with 0.2 mL of 50 mm Mops-KOH (pH 7.5), 2 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mg mL−1 polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (insoluble), 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mm PMSF (Wang and Nobel, 1996).

Oligofructans and other sugars were separated by HPLC at 24.0 ± 0.5°C using a Microsorb Amino column (Rainin Instrument, Emeryville, CA) with acetonitrile:water (70:30, v/v) as the mobile phase and were detected by differential refractometry (Frehner et al., 1984), which can separate oligofructans up to a DP of 8. Individual sugars and fructans were identified and quantified by comparing them with known concentrations of Fru, Glc, Suc, 1-kestose, and nystose (1-kestose and nystose were obtained from TCI America, Portland, OR; other reagents were from Sigma) and with published standard chromatograms (Cairns and Pollock, 1988; Pollock and Lloyd, 1994). The malate concentration was quantified spectrophotometrically (Wang and Nobel, 1996) using malic dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.37). The soluble proteins were quantified by the method of Bradford (1976) using BSA as a standard, with a slight modification for microscale analysis. The osmolality of the phloem sap collected under mineral oil was measured with a vapor pressure osmometer (model 5500, Wescor, Logan, UT), and the concentrations of sugars, oligofructans, and malate of the phloem sap were determined as described above.

Measurement of Enzyme Activities

To measure fructosyltransferase activity, 0.5 to 1.0 g of frozen chlorenchyma or 50 mg of dissected vascular tissues was ground at 0 to 2°C with 1 to 2 mL of 50 mm citric acid, 5 mm DTT, 5 mm ascorbic acid, 2 mm EDTA, and 1 mm PMSF at pH 5.5 (Lüscher and Nelson, 1995). After the sample was centrifuged, ammonium sulfate was added to 35% saturation to the decanted supernatant for 15 min to precipitate proteins. After the sample was centrifuged a second time, the supernatant was decanted and ammonium sulfate was added to 60% saturation for 20 min to precipitate fructosyltransferases. Again, the sample was centrifuged and the enzyme pellet was resuspended in 50 to 100 μL of the solution used for extraction and dialyzed overnight at 2 to 4°C against 20 mm His (pH 5.5). After dialysis, 20 μL of the dialyzed protein solution, free of sugars, was transferred to microcentrifuge tubes containing 80 μL of 25 mm Mes (pH 5.5) and 125 mm Suc or 63 mm 1-kestose. The sample was incubated at 27°C for 2 to 3 h, and the reaction was stopped by heating to 90°C for 3 min. The sample was centrifuged again, proteins in the supernatant were removed with a membrane filter, and the solution was injected onto an HPLC column to separate and quantify mono- and oligosaccharides. The fructosyltransferase activity was calculated as the amount of oligofructans produced per minute per milligram of protein.

To measure the activity of fructan hydrolases, about 20 mg of semidry phloem exudate collected without using mineral oil wells was dissolved in 20 μL of 50 mm Mes (pH 5.5) and dialyzed at 2 to 4°C overnight against the Mes buffer. After dialysis, the desalted phloem exudate was transferred to microcentrifuge tubes containing 80 μL of 50 mm Mes (pH 5.5) and 63 mm 1-kestose or nystose. After the sample was incubated at 30°C for 3 h (Pontis, 1990), the reaction was stopped by heating to 90°C for 3 min. The sample was centrifuged, proteins in the supernatant were removed by passage through a membrane filter, and the solution was analyzed by HPLC to separate and quantify mono- and oligosaccharides. The activity of fructan hydrolases was calculated as the amount of Fru, Suc, and 1-kestose released per minute per milligram of protein.

Suc synthase (EC 2.4.1.13) and acid and alkaline invertases (EC 3.2.1.26) in the chlorenchyma and the vascular tissues were extracted with 5 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, 5 mg mL−1 BSA, and 1 mm PMSF, and their activities were determined as for O. ficus-indica (Wang and Nobel, 1996). For phloem sap, the enzyme activities were determined after the sap was dialyzed against 50 mm Mops-KOH (pH 7.2) plus 2 μm leupeptin and 1 mm PMSF. The activity of alkaline invertase was measured by quantifying the amount of Glc released after 50 μL of the enzyme solution (extracted from the chlorenchyma or the vascular tissues) and dialyzed phloem sap was mixed with 100 μL of 50 mm Mops-KOH (pH 7.5) plus 150 mm Suc at 25°C for 30 min. All data are presented as means ± se (n = 4 plants, unless specified otherwise).

RESULTS

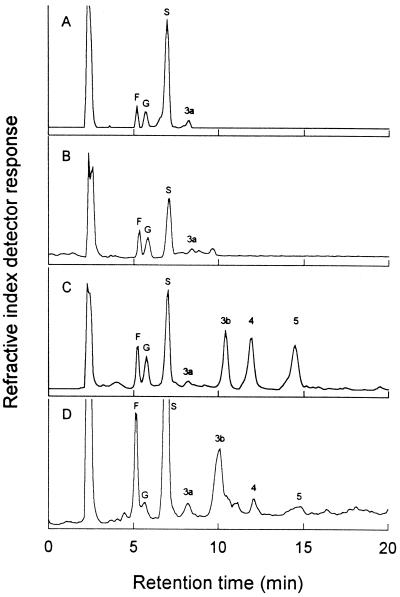

Suc was the predominate sugar in the chlorenchyma of mature green (source) leaves of A. deserti and only one fructan occurred, neokestose (DP 3), which was barely detectable (Fig. 1A). On a molar basis, Suc accounted for 66%, Glc plus Fru accounted for 32%, and neokestose accounted for only 2% of total soluble sugars in the chlorenchyma (Table I). Neokestose was also only barely detectable in the water-storage parenchyma (Fig. 1B). On a molar basis, it accounted for only 3% of total soluble sugars for the water-storage parenchyma, whereas Suc accounted for 44%. The concentrations of individual sugars, particularly Suc, and the osmolality were lower in the water-storage parenchyma than in the chlorenchyma; also, total soluble sugars accounted for 22% of the osmolality in the chlorenchyma and 9% in the water-storage parenchyma (Table I).

Figure 1.

HPLC profiles of mono- and oligosaccharides in the various tissues (A, chlorenchyma; B, water-storage parenchyma; and C, vascular) and in the phloem sap (D) of mature leaves of A. deserti. F, Fru; G, Glc; and S, Suc. Numbers indicate the DP: 3a, neokestose; 3b, 1-kestose; 4, nystose; and 5, an unidentified pentofructan.

Table I.

Concentrations of mono- and oligosaccharides in different tissues and in the phloem sap of mature leaves of A. deserti

| Sample | Fru | Glc | Suc | Neokestose | 1-Kestose | Nystose | Pentofructan | Osmolality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mOsm | |||||||

| Chlorenchyma | 15 ± 2 | 17 ± 2 | 65 ± 8 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | nda | nd | nd | 445 ± 7 |

| Water-storage parenchyma | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 14 ± 2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | nd | nd | nd | 342 ± 36 |

| Vascular tissuesb | 32 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 | 55 ± 9 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 27 ± 4 | 31 ± 4 | 35 ± 5 | 469 ± 52 |

| Phloem sap | 89 ± 12 | 15 ± 2 | 199 ± 15 | 9.6 ± 1.9 | 46 ± 5 | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 11 ± 1 | 482 ± 45 |

Samples were harvested 4 to 5 h after the beginning of the light period. Data are means ± se; n = 4 plants.

nd, Not detected.

Included vascular parenchyma cells, phloem parenchyma cells, sieve tubes, and companion cells, and was contaminated with a small amount of chlorenchyma and water-storage parenchyma.

At least four oligofructans occurred in the vascular tissues of mature leaves of A. deserti in addition to the sugars Glc, Fru, and Suc (Fig. 1C). On a molar basis, neokestose, 1-kestose (DP 3), nystose (DP 4), and an unidentified pentofructan together accounted for 46% of total soluble sugars in such tissues, almost twice as high as the Suc concentration (Table I). Total soluble sugars in the vascular tissues accounted for 45% of the osmolality. These four oligofructans also occurred in the phloem sap of mature leaves (Fig. 1D), where they accounted for 19% of total soluble sugars; Fru accounted for 24%, and Suc accounted for 53% (Table I). Total soluble sugars in the phloem sap accounted for about 78% of its osmolality. The concentration of Suc was 3.6 times lower, that of nystose was 4.9 times higher, and that of pentofructan was 3.2 times higher in the vascular tissues than in the phloem sap (Table I).

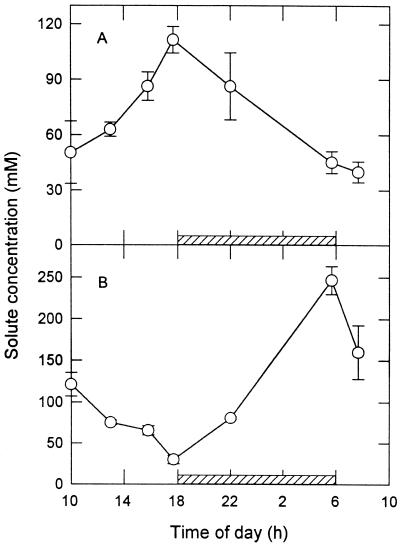

Suc and malate concentrations changed diurnally in a reciprocal manner. Specifically, the Suc concentration in the chlorenchyma gradually increased during the daytime, reaching a maximum of 112 mm at dusk, and then gradually decreasing to a minimum of 45 mm immediately after darkness (Fig. 2A). The malate concentration in the chlorenchyma gradually decreased throughout the daytime, reaching a minimum of 30 mm, and then increased to a maximum of 247 mm at the end of the night (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Daily changes of Suc concentration (A) and malate concentration (B) in the chlorenchyma of A. deserti. Hatched bars indicate nighttime. The data are means ± se for n = 4 plants.

The activity of fructosyltransferases was not detected in the chlorenchyma but was substantial in the vascular tissues (Table II). On a total soluble protein basis, the activity of fructan hydrolases was 18 times higher in the phloem sap compared with that of fructosyltransferases in the chlorenchyma. The total soluble protein content in mature leaves averaged 0.097 ± 0.010 mg g−1 phloem sap (n = 4 plants) compared with 5.40 ± 0.02 mg g−1 fresh weight for the chlorenchyma (n = 5 plants). Thus, on a fresh weight basis, the fructan hydrolase activity was about 3 times higher in the chlorenchyma than in the phloem sap, accounting for less than 5% of the Suc hydrolyzed in the phloem. For the chlorenchyma, Suc synthase is the major enzyme responsible for cytosolic Suc breakdown, because its activity was about 3.5 times higher than that of acid invertase plus alkaline invertase (Table II). No acid or alkaline invertase activity was detected in the phloem sap.

Table II.

Enzyme activities in various regions of mature leaves of A. deserti

| Enzyme | Sample | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| nmol mg−1 protein min−1 | ||

| Fructosyltransferases | Chlorenchyma | nda |

| Vascular tissues | 14.6 ± 2.0 | |

| Fructan hydrolases | Phloem sap | 260 ± 27 |

| Suc synthase | Chlorenchyma | 14.1 ± 1.5 |

| Acid invertase | Chlorenchyma | 3.0 ± 3.0 |

| Phloem sap | nd | |

| Alkaline invertase | Chlorenchyma | 1.1 ± 1.0 |

| Phloem sap | nd |

Data are means ± se; n = 4 plants.

nd, Not detected.

DISCUSSION

Fructan biosynthesis was apparently restricted to the vascular tissues in mature leaves of A. deserti. In particular, fructans were virtually absent from the chlorenchyma and the water-storage parenchyma but accumulated in the vascular tissues. Coincident with the high concentrations of oligofructans in the vascular tissues was the substantial activity of fructosyltransferases (responsible for fructan biosynthesis), whereas fructosyltransferase activity was not detected in the chlorenchyma. The fact that oligofructans accumulated only in the vascular tissues and were nearly absent from both the chlorenchyma and the water-storage parenchyma suggests that back diffusion of these fructans from the vascular tissues (such as from phloem parenchyma cells) to the photosynthetic cells is extremely low despite a substantial concentration gradient, consistent with the polymer-trapping hypothesis (Turgeon, 1991).

Suc was the major carbon source for nocturnal malate production in mature leaves of A. deserti. The nocturnal decrease of Suc was 66 mm, which sustained the nocturnal malate production of 217 mm (equivalent to 54 mm Suc, because one Suc can be used to synthesize four malates; Carnal and Black, 1989). Nocturnal production of other organic acids, such as citric acid (Kluge and Ting, 1978), can also utilize Suc, suggesting that little extra Suc is available for fructan synthesis, consistent with the small amount of fructans in the chlorenchyma.

The particular cell type in the vascular tissues that is responsible for fructan biosynthesis in mature leaves of A. deserti is unclear. In Turgeon's polymer-trapping model the sites for the synthesis of RFO in Coleus blumei and Cucurbita pepo (dicotyledonous species using the C3 photosynthetic pathway) are intermediary cells (specialized companion cells with numerous plasmodesmata connected to the bundle-sheath cells; Turgeon, 1991). For A. deserti, a monocot using the CAM pathway, intermediary cells as found in dicots are unlikely. Moreover, for the minor veins of C. blumei and C. pepo, the bundle-sheath cells are directly associated with the intermediary cells (Turgeon et al., 1975; Fisher, 1986), but no such bundle-sheath cells were observed in the vascular strands of A. deserti (N. Wang and P.S. Nobel, unpublished observations). Therefore, the sites for oligofructan synthesis and accumulation in mature leaves of A. deserti may be phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells to be identified in the future.

The fructans in the phloem sap of A. deserti were apparently not from contamination with microorganisms. When the phloem sap of O. ficus-indica is contaminated with microorganisms, the activity of invertases often lead to equal amounts of Glc and Fru after Suc is hydrolyzed (N. Wang and P.S. Nobel, unpublished observations). Also, 6-kestose, a common end product of acid invertase action on oligofructans (Cairns, 1993; Lüscher and Nelson, 1995), was virtually absent from the phloem sap of A. deserti, consistent with the lack of invertase activity there. On a whole-tissue basis, the Suc concentration in the chlorenchyma (mesophyll cells) averaged about 70 mm over 24 h. The volume of cytosol in mesophyll cells is about 5% of the total cell volume for C3 and CAM species (Lüttge et al., 1982; Winter et al., 1994; Haritatos et al., 1996), and about 26% of the cell Suc pool is in the cytosol for Suc-storage species (Winter et al., 1994) such as A. deserti, the mature leaves of which contained virtually no starch (N. Wang and P.S. Nobel, unpublished observations). Thus, the Suc concentration in the cytosol of mesophyll cells of mature leaves of A. deserti could be about 350 mm, about 1.8 times higher than in the phloem sap, similar to the 1.5 times higher Suc concentration in the cytosol of mesophyll cells in mature leaves of Cucumis melo than in their sieve tubes/intermediary cells (Haritatos et al., 1996).

The vascular tissues of A. deserti collected with a fine syringe needle were always contaminated with small amounts of chlorenchyma and water-storage parenchyma (which had little detectable oligofructans); therefore, the concentration of oligofructans in individual phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells is higher than the average measured concentration in the vascular tissues. If we assume that the total soluble sugars in the phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells also accounted for about 78% of the osmolality, just as for the phloem sap, sugar concentrations in these cells can be estimated from the sugar concentrations in the vascular tissues by multiplying by 1.75 (78/45%). Based on such a calculation, sugar concentration gradients along the phloem-loading pathway from the chlorenchyma to the sieve tubes/companion cells can be approximated. In particular, Suc, 1-kestose, nystose, a pentofructan, and Glc could diffuse from the chlorenchyma or from phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells into the sieve tubes/companion cells, whereas the situation for Fru is unclear because the Fru concentration in the cytosol of chlorenchyma cells in mature leaves of A. deserti is unknown. In any case, such findings are in contrast with those for plants with apoplastic loading pathways, such as Zea mays (Bush, 1993), in which Suc is the only sugar in the phloem sap (Ohshima et al., 1990). However, such findings are similar to those from plants with symplastic loading pathways, including the CAM species Xerosicyos danguyi, in which substantial amounts of oligosaccharides, such as raffinose and stachyose, are present in the companion cells in addition to Suc (Madore et al., 1988; van Bel, 1993).

Therefore, like the cucurbit X. danguyi, A. deserti may use a polymer-trapping mechanism (Turgeon, 1991) for symplastic loading of photosynthates in its mature leaves. Suc in photosynthetic cells may diffuse via plasmodesmata to vascular parenchyma cells and then to phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells. After Suc enters such cells, it may be converted by fructosyltransferases to 1-kestose and higher DP fructans such as nystose and pentofructan. Because the channel size of plasmodesmata between the vascular parenchyma and the phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells may pass Suc but restrict the diffusion of oligofructans such as 1-kestose, nystose, and a pentofructan, oligofructan concentrations can increase in the phloem parenchyma cells or other types of vascular cells. These oligofructans may then diffuse from such cells to the sieve tubes/companion cells via plasmodesmata. To our knowledge, this provides the first evidence that oligofructans are synthesized and transported in the phloem of mature leaves of higher plants. The polymer-trapping mechanism that operates in dicotyledonous C3 species may also be valid for oligofructan transport in monocotyledonous species such as A. deserti.

Abbreviations:

- DP

degree of polymerization

- RFO

raffinose-family oligosaccharides

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Office of Health and Environmental Research, U.S. Department of Energy, Program for Ecosystem Research (grant no. DE-FG03-93ER61686).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aspinall GO, Gupta PC. The structure of the fructosan from Agave vera-cruz Mill. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:718–722. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia IS, Nandra KS. Studies on fructosyl transferase from Agave americana. Phytochemistry. 1979;18:923–927. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush DR. Proton-coupled sugar and amino acid transporters in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1993;44:513–542. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ. Evidence for the de novo synthesis of fructan by enzymes from higher plants: a reappraisal of the SST/FFT model. New Phytol. 1993;123:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns AJ, Pollock CJ. Fructan biosynthesis in excised leaves of Lolium temulentum L. I. Chromatographic characterization of oligofructans and their labeling patterns following 14CO2 feeding. New Phytol. 1988;109:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Carnal NW, Black CC. Soluble sugars as the carbohydrate reserve for CAM in pineapple leaves. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:91–100. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorland L, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG, Satyanarayana N. Oligosaccharides isolated from Agave vera-cruz. Carbohydrate Res. 1977;54:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG. Ultrastructure, plasmodesmata frequency, and solute concentration in green areas of variegated Coleus blumei Benth. leaves. Planta. 1986;169:141–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00392308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora LL, Madore A. Stachyose and mannitol transport in olive (Olea europaea L.) Planta. 1993;189:484–490. [Google Scholar]

- Frehner M, Keller F, Wiemken A, Matile P. Localization of fructan metabolism in the vacuoles isolated from protoplasts of Jerusalem artichoke tubers (Helianthus tuberosus L.) J Plant Physiol. 1984;116:197–208. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(84)80089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaquinta RT. Phloem loading of sucrose. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1983;34:347–387. [Google Scholar]

- Grusak MA, Beebe DU, Turgeon R (1996) Phloem loading. In E Zamski, A Schaffer, eds, Photoassimilate Distribution in Plants and Crops: Source to Sink Relationships. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 209–227

- Haritatos E, Felix K, Turgeon R. Raffinose oligosaccharide concentrations measured in individual cell and tissue types in Cucumis melo L. leaves: implications for phloem loading. Planta. 1996;198:614. doi: 10.1007/BF00262649. -622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritatos E, Turgeon R (1996) Symplastic phloem loading by polymer trapping. In HG Pontis, GL Salerno, EJ Echeverria, eds, Sucrose Metabolism, Biochemistry, Physiology and Molecular Biology. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 216–224

- Kluge M, Ting IP. The metabolic pathway of CAM. In: Kluge M, Ting IP, editors. Crassulacean Acid Metabolism. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1978. pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher M, Nelson CJ. Fructosyltransferase activities in the leaf growth zone of tall fescue. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1419–1425. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttge U, Smith JAC, Marigo G (1982) Membrane transport, osmoregulation, and the control of CAM. In IP Ting, M Gibbs, eds, Crassulacean Acid Metabolism. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 69–91

- Madore MA, Mitchell DE, Boyd CM. Stachyose synthesis in source leaf tissues of the CAM plant Xerosicyos danguyi H. Humb. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:588–591. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.3.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS (1988) Environmental Biology of Agaves and Cacti. Cambridge University Press, New York

- North GB, Nobel PS. Hydraulic conductivity of concentric root tissues of Agave deserti Engelm. under wet and drying conditions. New Phytol. 1995;130:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima T, Hayashi H, Chino M. Collection and chemical composition of pure phloem sap from Zea mays L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1990;31:735–737. [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits EAH, Ebskamp MJM, Weisbeek PJ, Smeekens SCM (1996) Fructan accumulation in transgenic plants: effects on growth, carbohydrate partitioning and stress resistance. In HG Pontis, GL Salerno, EJ Echeverria, eds, Sucrose Metabolism, Biochemistry, Physiology and Molecular Biology. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 88–99

- Pollock CJ, Cairns AJ. Fructan metabolism in grasses and cereals. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock CJ, Lloyd EJ. The metabolism of fructans during seed development and germination in onion (Allium cepa L.) New Phytol. 1994;128:601–605. [Google Scholar]

- Pontis HG. Fructans. In: Dey PM, Harborne JB, editors. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. London: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Spollen WG, Nelson CJ. Response of fructan to water deficit in growing leaves of tall fescue. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:329–336. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon RJ. Monosaccharides. In: Dey PM, Harborne JB, editors. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. London: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon R (1991) Symplastic phloem loading and the sink-source transition in leaves: a model. In JL Bonnemain, S Delrot, WJ Lucas, J Dainty, eds, Recent Advances in Phloem Transport and Assimilate Compartmentation. Quest Editions, Nantes, France, pp 18–22

- Turgeon R, Webb JA, Evert RF. Ultrastructure of minor veins in Cucurbita pepo leaves. Protoplasma. 1975;83:217–232. [Google Scholar]

- van Bel AJE. Strategy of phloem loading. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1993;44:253–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Nobel PS. Phloem exudate collected via scale insect stylets for the CAM species Opuntia ficus-indica under current and doubled CO2 concentrations. Ann Bot. 1995;75:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Nobel PS. Doubling the CO2 concentration enhanced the activity of carbohydrate-metabolism enzymes, source carbohydrate production, photoassimilate transport, and sink strength for Opuntia ficus-indica. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:893–902. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemken A, Sprenger N, Boller T (1996) Fructan—an extension of sucrose by sucrose. In HG Pontis, GL Salerno, EJ Echeverria, eds, Sucrose Metabolism, Biochemistry, Physiology and Molecular Biology. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 179–189

- Winter H, Robinson DG, Heldt HW. Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in spinach leaves. Planta. 1994;193:530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler H. List of sugars and sugar alcohols in sieve-tube exudates. In: Zimmerman MH, Milburn JA, editors. Transport in Plants. I. Phloem Transport. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1975. pp. 480–503. [Google Scholar]