Abstract

Objectives

We sought to examine associations between initiation of beta-blocker therapy and outcomes among elderly patients hospitalized for heart failure.

Background

Beta-blockers are guideline-recommended therapy for heart failure, but their clinical effectiveness is not well-understood, especially in elderly patients.

Methods

We merged Medicare claims data with OPTIMIZE-HF records to examine long-term outcomes of eligible patients newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy. We used inverse probability-weighted Cox proportional hazards models to determine the relationships between treatment and mortality, rehospitalization, and a combined mortality–rehospitalization endpoint.

Results

Observed 1-year mortality was 33%, and all-cause rehospitalization was 64%. Among 7154 patients hospitalized with heart failure and eligible for beta-blockers, 3421 (49%) were newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy. Among patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD; n = 3001), beta-blockers were associated with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68–0.87) for mortality, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.80–0.99) for rehospitalization, and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.79–0.96) for mortality–rehospitalization. Among patients with preserved systolic function (n = 4153), beta-blockers were associated with adjusted hazard ratios of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.84–1.07) for mortality, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.90–1.06) for rehospitalization, and 0.98 (95% CI, 0.91–1.06) for mortality-rehospitalization.

Conclusions

In elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure and LVSD, incident beta-blocker use was clinically effective and independently associated with lower risks of death and rehospitalization. Patients with preserved systolic function had poor outcomes, and beta-blockers did not significantly influence the mortality and rehospitalization risks for these patients.

Keywords: Adrenergic beta-Antagonists, Heart Failure, Mortality, Patient Readmission

Introduction

Heart failure is the most common discharge diagnosis for Medicare beneficiaries, and over half of patients admitted for heart failure will be readmitted within 6 months (1, 2). Although outcomes for heart failure are poor, advances in understanding of heart failure over the past 2 decades have led to important advances in therapy. One major advance is the clinical trial evidence for beta-blockers, which are now a cornerstone of heart failure treatment (3).

Among patients with heart failure and reduced systolic function who are enrolled in randomized clinical trials, beta-blockers confer a 10% to 40% reduction in mortality and hospitalization within 1 year (4–6). Patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials tend to be relatively young, have relatively few comorbid conditions, and are not representative of the general heart failure population encountered in clinical practice (7). Moreover, patients’ care in clinical trials may be significantly better compared to the general population of patients with heart failure. Thus, there is limited data on the effectiveness and safety of beta-blockers in non-clinical trial populations of patients with systolic dysfunction, and there are almost no data for patients with preserved systolic function.

A number of studies have found that evidence-based heart failure therapies are underused, especially in the elderly (8–11). Although current guidelines recommend that populations underrepresented in heart failure clinical trials—including elderly patients, women, racial/ethnic minorities, and patients with comorbid conditions—should be treated like the broader population in the absence of specific evidence to the contrary, some physicians may be hesitant to do so without additional evidence of effectiveness in these populations (3–6, 12).

Given the limited evidence and the uncertainty, we sought to measure the clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in a broad group of eligible elderly patients with heart failure who were newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy and discharged after a heart failure hospitalization.

Methods

Data Sources

We merged data from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) and from enrollment files and inpatient claims from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). OPTIMIZE-HF was a national registry and performance-improvement program for patients hospitalized with heart failure (13–16). This nationwide patient registry was used to gather data on various patient characteristics with a Web-based information system. In an approach similar to Joint Commission case ascertainment of heart failure hospitalizations, eligibility for OPTIMIZE-HF required patients to be adults hospitalized for an episode of new or worsening heart failure as the primary cause of admission or with significant heart failure symptoms that developed during a hospital stay with a primary discharge diagnosis of heart failure. Similar to other national cardiovascular registries and quality-reporting initiatives, data regarding medical history, signs and symptoms, medications, and diagnostic tests were collected via a Web-based registry. The registry also includes data on contraindications, intolerance, and other reasons for not prescribing therapy. All regions of the United States are represented in the registry, and a variety of institutions participated, from community hospitals to large tertiary medical centers. The OPTIMIZE-HF protocol was approved by each participating center’s institutional review board or by a central institutional review board. Automated electronic data checks were used to prevent out-of-range entries and duplicate patients. A source data verification audit of a random 5% of the first 10 000 records collected showed better than 99% concordance on 53% of the fields (118/223) and 95% concordance on 91% of the fields (205/223). Fields with less than 95% concordance were not used in this analysis.

The CMS files include all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of heart failure (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 428.x, 402.x1, 404.x1, 404.x3). We matched patients in the OPTIMIZE-HF registry to Medicare enrollment and inpatient data according to date of birth, sex, admission date, discharge date, and hospital site. Of the 36 165 hospitalizations involving patients aged 65 years and older, we matched 29 301 (81%) to CMS claims, representing 25 901 unique patients. OPTIMIZE-HF patients linked to Medicare claims had similar demographic characteristics and outcomes as other Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure (17). For example, compared to 925 161 non-OPTIMIZE-HF fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, OPTIMIZE-HF patients were not different from non-OPTIMIZE-HF patients with respect to age (79.5 vs 79.8 years), sex (44.0% vs 42.5% male), or race (89.1% vs 88.6% non-black).

The institutional review board of the Duke University Health System approved this study.

Analysis Population

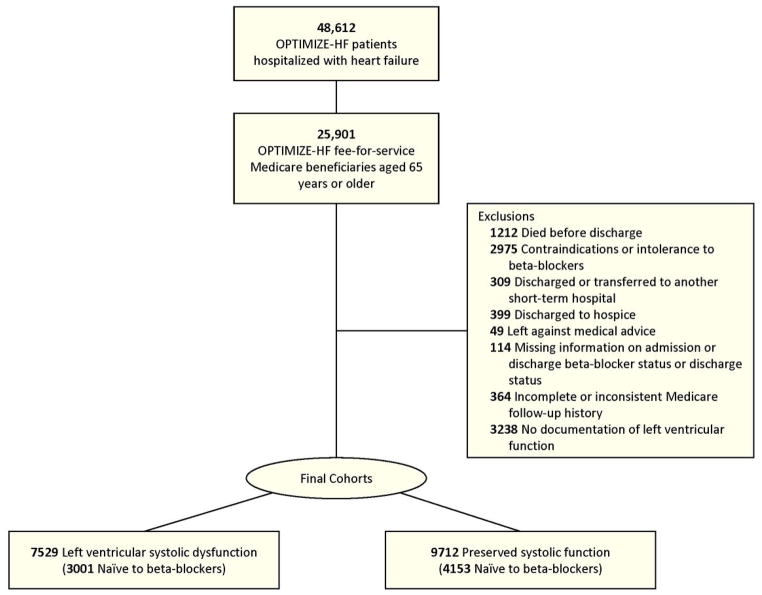

After exclusion of 1212 patients who died before discharge, the merged data set included 24 689 patients with heart failure aged 65 and older who were discharged alive from the hospital and for whom Medicare data were available (Figure 1). For patients with multiple hospitalizations recorded in the registry, we used information from the earliest hospitalization. We included only patients documented as eligible for beta-blocker therapy. We successively excluded patients who had a documented contraindications or intolerance to beta-blockers (n = 2975), who were discharged or transferred to another short-term hospital (n = 309) or hospice (n = 399), or who left against medical advice (n = 49) (18). We also excluded patients who were missing information on admission beta-blocker status, discharge beta-blocker status, or discharge status (n = 114) and patients with incomplete or inconsistent Medicare follow-up history (n = 364).

Figure 1.

Derivation of Analysis Populations Eligible for Beta-Blocker With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction and Preserved Systolic Function

From the remaining patients, we created 2 analysis cohorts. The first cohort—those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD)—included patients with either documented left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40% or qualitative documentation of LVSD (n = 7529). The second cohort—those with preserved systolic function—included patients with either documented LVEF ≥ 40% or qualitative documentation of preserved systolic function (n = 9712). We excluded patients without documentation of left ventricular function (n = 3238).

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were time to death, time to first rehospitalization, and time to death or first rehospitalization within 1 year after hospital discharge. We obtained dates of death from the CMS enrollment files and data regarding hospital admissions from the CMS inpatient files. We did not count subsequent admissions for rehabilitation as rehospitalizations in this analysis.

Primary Analyses

The primary analysis estimated the effect of newly initiated beta-blocker therapy vs no beta-blocker therapy on mortality and all-cause rehospitalization at 1 year in eligible patients with heart failure who were naïve to beta-blockers at hospital admission. There were 3001 patients in the LVSD cohort and 4153 patients in the preserved systolic function cohort. We analyzed the 2 cohorts separately. In sensitivity analyses, we replicated the primary analysis in all eligible patients regardless of whether they were taking beta-blockers before admission. That is, we included both patients newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy and those who were continuing beta-blocker therapy. We also explored whether findings for clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers differed between patients with LVEF of 40% to 49% compared to the overall cohort with preserved systolic function.

In the LVSD and preserved systolic function cohorts, we also evaluated whether there was heterogeneity in the findings regarding beta-blocker effectiveness. Specifically, we examined whether the effectiveness of beta-blockers was the same for patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized baseline characteristics by treatment group using percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. For comparisons by treatment group, we used chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. We summarized observed mortality using a Kaplan-Meier estimator and rehospitalization using the cumulative incidence function (19). We estimated the unadjusted relationship between treatment and outcome using a Cox proportional hazards model in which treatment group was the only variable. We estimated the adjusted relationship between treatment and outcome using an inverse probability-weighted Cox proportional hazards model (20, 21). The weights in this model were based on propensity to receive treatment (Supplemental Appendix). Specifically, we used logistic regression models to estimate the propensity to receive any beta-blocker at discharge (vs no beta-blocker) as a function of age at admission, sex, race, ischemic heart failure status, LVEF, systolic blood pressure, smoking within the prior year, rales, or lower extremity edema at admission; serum sodium level, serum creatinine level, and hemoglobin level at admission; other discharge medications (ie, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker [ARBs]); in-hospital procedures (ie, angiography, mechanical ventilation, implantable cardioverter defibrillator); and history of diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, atrial arrhythmia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, reactive airway disease, anemia, peripheral vascular disease, thyroid abnormality, prior cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack, depression, or renal insufficiency. To assess the heterogeneity of effect by subgroup, we included treatment-by-subgroup interactions in separate inverse probability-weighted Cox proportional hazards models. Because this approach resulted in additional statistical comparisons, we required P < .01 for the interactions to be considered statistically significant.

Results

In the primary analysis of the LVSD cohort (n = 3001), which included patients with heart failure and LVSD who were eligible for beta-blockers and naïve to beta-blockers at admission, 1800 patients (60.0%) were newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort by discharge beta-blocker status. Patients discharged on beta-blockers were slightly younger and had less atrial arrhythmia and renal insufficiency compared to eligible patients discharged without beta-blockers.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Eligible Patients With Heart Failure*

| Variable | Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction | Preserved Systolic Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Beta-Blocker (n = 1800) | No Beta-Blocker (n = 1201) | P Value | Beta-Blocker (n = 1621) | No Beta-Blocker (n = 2532) | P Value | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 78.0 (72.0–84.0) | 80.0 (74.0–85.0) | < .001 | 80.0 (74.0–86.0) | 81.0 (75.0–87.0) | .01 |

| Male sex | 985 (54.7) | 671 (55.9) | .54 | 555 (34.2) | 863 (34.1) | .92 |

| Race | .70 | .004 | ||||

| African American | 231 (12.8) | 162 (13.5) | 218 (13.4) | 256 (10.1) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 11 (0.6) | 13 (1.1) | 17 (1.0) | 21 (0.8) | ||

| Caucasian | 1448 (80.4) | 951 (79.2) | 1297 (80.0) | 2097 (82.8) | ||

| Native American | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) | ||

| Other | 62 (3.4) | 38 (3.2) | 42 (2.6) | 57 (2.3) | ||

| Unknown | 44 (2.4) | 34 (2.8) | 41 (2.5) | 96 (3.8) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 60 (3.3) | 38 (3.2) | .80 | 43 (2.7) | 64 (2.5) | .80 |

| Heart failure details | ||||||

| Ejection fraction | .003 | < .001 | ||||

| < 30% | 1145 (63.6) | 700 (58.3) | — | — | ||

| 30% to 39% | 655 (36.4) | 501 (41.7) | — | — | ||

| 40% to 49% | — | — | 653 (40.3) | 872 (34.4) | ||

| ≥ 50% | — | — | 968 (59.7) | 1,660 (65.6) | ||

| Ischemic etiology | 883 (49.1) | 632 (52.6) | .06 | 559 (34.5) | 752 (29.7) | .001 |

| Comorbid conditions and clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 652 (36.2) | 433 (36.1) | .93 | 597 (36.8) | 924 (36.5) | .83 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 514 (28.6) | 336 (28.0) | .73 | 446 (27.5) | 657 (25.9) | .27 |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 542 (30.1) | 403 (33.6) | .05 | 532 (32.8) | 930 (36.7) | .01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 451 (25.1) | 326 (27.1) | .20 | 415 (25.6) | 755 (29.8) | .003 |

| Pulmonary reactive airway disease | 64 (3.6) | 38 (3.2) | .56 | 78 (4.8) | 98 (3.9) | .14 |

| Anemia | 239 (13.3) | 186 (15.5) | .09 | 311 (19.2) | 507 (20.0) | .51 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 258 (14.3) | 174 (14.5) | .91 | 206 (12.7) | 316 (12.5) | .83 |

| Thyroid abnormality | 248 (13.8) | 217 (18.1) | .001 | 277 (17.1) | 487 (19.2) | .08 |

| Prior cerebrovascular accident or TIA | 271 (15.1) | 208 (17.3) | .10 | 268 (16.5) | 441 (17.4) | .46 |

| Depression | 158 (8.8) | 99 (8.2) | .61 | 163 (10.1) | 280 (11.1) | .31 |

| Smoker within the past year | 240 (13.3) | 134 (11.2) | .08 | 147 (9.1) | 202 (8.0) | .22 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 244 (13.6) | 213 (17.7) | .002 | 227 (14.0) | 392 (15.5) | .19 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 117 (105.0–131.0) | 118 (106.0–131.0) | .20 | 128 (113.0–144.0) | 128 (114.0–143.0) | .99 |

| Rales | 1172 (65.1) | 761 (63.4) | .33 | 1073 (66.2) | 1572 (62.1) | .007 |

| Lower extremity edema | 1110 (61.7) | 737 (61.4) | .87 | 1039 (64.1) | 1676 (66.2) | .17 |

| Serum sodium level < 135 mmol/L | 340 (18.9) | 229 (19.1) | .90 | 332 (20.5) | 489 (19.3) | .36 |

| Serum creatinine level < 2 mg/dL | 1503 (83.5) | 929 (77.4) | < .001 | 1361 (84.0) | 2107 (83.2) | .53 |

| Hemoglobin level < 9 g/dL | 58 (3.2) | 52 (4.3) | .11 | 112 (6.9) | 171 (6.8) | .85 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

In the preserved systolic function cohort (n = 4153), which included patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function who were eligible for beta-blockers and naïve to beta-blockers at admission, 1621 patients (39.0%) were discharged on beta-blocker therapy. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort by discharge beta-blocker status. Patients discharged on beta-blockers were more often of non-white race and had a higher frequency of ischemic heart failure than patients not discharged without beta-blockers. Eligible patients discharged without beta-blockers had higher median LVEF and higher prevalence of atrial arrhythmia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2 shows the discharge therapies for the two cohorts. In general, patients discharged on beta-blocker therapy in both cohorts were more likely to be taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs, antiplatelet agents, lipid-lowering agents, and aldosterone antagonists. Inpatient cardiac catheterization rates were higher in both cohorts for patients discharged on beta-blocker therapy.

Table 2.

Discharge Therapy and Procedures for Eligible Patients With Heart Failure and Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction*

| Variable | Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction | Preserved Systolic Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Beta-Blocker (n = 1800) | No Beta-Blocker (n = 1201) | P Value | Beta-Blocker (n = 1621) | No Beta-Blocker (n = 2532) | P Value | |

| Discharge medications | ||||||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 1383 (76.8) | 747 (62.2) | < .001 | 1046 (64.5) | 1373 (54.2) | < .001 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 328 (18.2) | 129 (10.7) | < .001 | 150 (9.3) | 181 (7.1) | .02 |

| Antiplatelet | 1081 (60.1) | 604 (50.3) | < .001 | 920 (56.8) | 1111 (43.9) | < .001 |

| Digoxin | 681 (37.8) | 452 (37.6) | .91 | 330 (20.4) | 581 (22.9) | .05 |

| Diuretic | 1515 (84.2) | 994 (82.8) | .31 | 1290 (79.6) | 2051 (81.0) | .26 |

| Lipid-lowering agent | 635 (35.3) | 364 (30.3) | .005 | 511 (31.5) | 653 (25.8) | < .001 |

| In-hospital procedures | ||||||

| Coronary angiography | 368 (20.4) | 83 (6.9) | < .001 | 146 (9.0) | 99 (3.9) | < .001 |

| ICD placement | 64 (3.6) | 15 (1.2) | < .001 | 36 (2.2) | 39 (1.5) | .11 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 368 (20.4) | 83 (6.9) | < .001 | 146 (9.0) | 99 (3.9) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Values are expressed as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

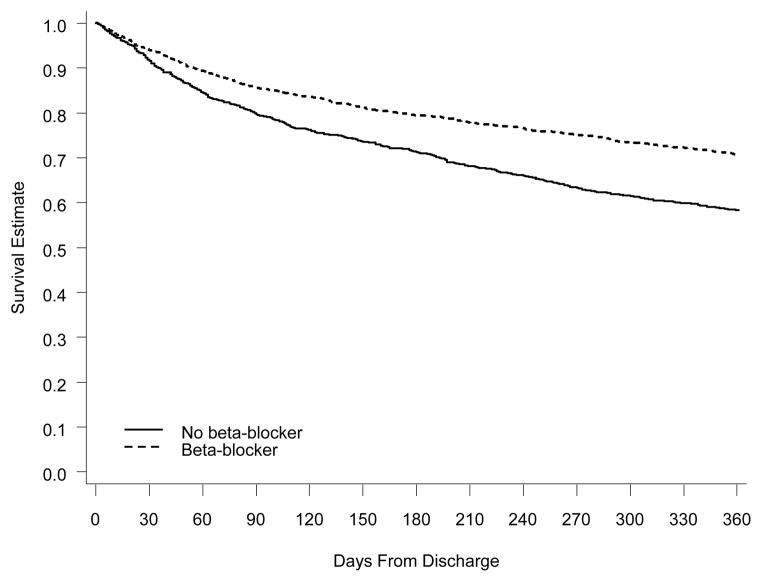

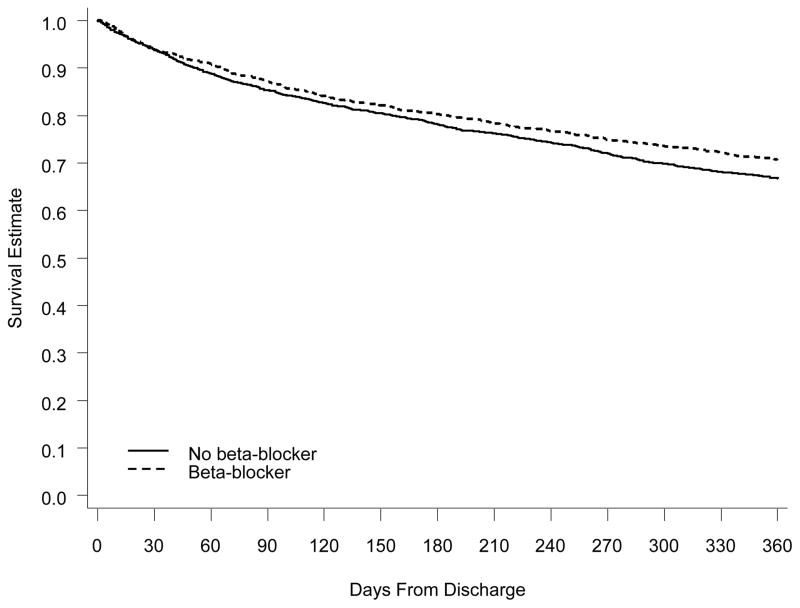

Observed 1-year mortality for all patients who were eligible for and naïve to beta-blockers at admission was 32.8%, and the 1-year all-cause rehospitalization rate was 64.3%. In the LVSD cohort, 1-year mortality was 34.3% and the 1-year rehospitalization rate was 63.2%. In the preserved systolic function cohort, 1-year mortality was 31.7% and the rehospitalization rate was 65.0%. One-year survival for eligible patients initiated on beta-blocker therapy compared to eligible patients not initiated on beta-blocker therapy at discharge is shown in Figure 2 for patients with LVSD and in Figure 3 for patients with preserved systolic function.

Figure 2. One-Year Survival for Eligible Patients With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction on Beta-Blocker Therapy vs Patients Not on Beta-Blocker Therapy at Discharge.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves at 1 year. The solid line represents eligible patients who were not on beta-blocker therapy at discharge. The dashed line represents eligible patients who were on beta-blocker therapy at discharge.

Figure 3. One-Year Survival for Eligible Patients With Preserved Systolic Function on Beta-Blocker Therapy vs Patients Not on Beta-Blocker Therapy at Discharge.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves at 1 year. The solid line represents eligible patients who were not on beta-blocker therapy at discharge. The dashed line represents eligible patients who were on beta-blocker therapy at discharge.

In both cohorts, the discrimination of the propensity model was moderate, indicating that the treatment groups were similar enough to be adjusted using propensity weights (22). The c statistics for the propensity models were 0.67 in the LSVD cohort and 0.63 in the preserved systolic dysfunction cohort. In both models, the most important variables, defined as those with the highest Wald chi-square values, included other discharge therapies (ie, antiplatelet therapy, ACE inhibitor or ARB) and within-hospital angiography. After weighting observations by their propensity for treatment received, none of the factors listed in Table 1 or Table 2 differed significantly between treatment groups in either cohort.

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted results for incident beta-blocker therapy at discharge compared to no beta-blocker therapy for both cohorts. In the LVSD cohort, we observed a protective effect of beta-blocker therapy on mortality and on the combined endpoint of mortality and rehospitalization. After adjustment, the hazard rate for mortality was 23% lower for patients newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy, compared to those eligible but not discharged on beta-blocker therapy. For the combined endpoint, the adjusted hazard rate was 13% lower for patients newly initiated on beta-blocker therapy. After adjustment, incident beta-blocker therapy at discharge did not have a statistically significant effect on the hazard of rehospitalization among patients with LVSD. Among patients with preserved systolic function, incident beta-blocker therapy at discharge did not have a statistically significant effect on mortality, rehospitalization, or the combined endpoint after adjustment.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Initiation of Beta-Blocker Therapy vs No Beta-Blocker Therapy

| Population and Outcome | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Unadjusted | Inverse-Weighted | |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction (n = 3001) | ||

| Mortality | 0.65 (0.57–0.73) | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) |

| Readmission | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) |

| Combined | 0.79 (0.72–0.86) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) |

| Preserved systolic dysfunction (n = 4153) | ||

| Mortality | 0.87 (0.77–0.97) | 0.94 (0.84–1.07) |

| Readmission | 0.96 (0.88–1.03) | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) |

| Combined | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

In sensitivity analyses, we explored outcomes in subgroups of patients with LVSD, including patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, and diabetes mellitus. Table 4 shows the relatively homogeneous findings for mortality in these subgroups. Based on α = 0.01 as a significant interaction, adjusted hazard ratios for beta-blocker therapy showed no significant heterogeneity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency and in patients aged 65 to 74 years and 75 years and older. The findings were similar for rehospitalization and the combined endpoint of mortality and rehospitalization in these subgroups. We performed subgroup analyses of patients with preserved systolic function (Supplemental Appendix). We also examined 937 patients with a measured ejection fraction of 40% to 49%. In this group, 454 (48%) patients initiated beta-blocker therapy at discharge. The unadjusted and inverse-weighted hazard ratios for initiation of beta-blocker therapy compared to no beta-blocker were similar. The adjusted hazard ratios were 0.95 (95% CI, 0.75–1.20) for mortality, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.78–1.07) for rehospitalization, and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.78–1.04) for mortality/rehospitalization.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses of Subgroups in Patients With Heart Failure and Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction

| Subgroup | No. of Events | Unadjusted HR (95% CI)* | P Value for Interaction | Inverse-Weighted HR (95% CI)* | P Value for Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | .008 | .02 | |||

| No (n = 2224) | 734 | 0.59 (0.51–0.68) | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) | ||

| Yes (n = 777) | 301 | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | ||

| Renal insufficiency | .31 | .22 | |||

| No (n = 2544) | 806 | 0.68 (0.59–0.78) | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | ||

| Yes (n = 457) | 229 | 0.59 (0.45–0.76) | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | .57 | .94 | |||

| No (n = 1916) | 629 | 0.63 (0.54–0.73) | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | ||

| Yes (n = 1085) | 406 | 0.68 (0.56–0.82) | 0.76 (0.64–0.94) | ||

| Age | .96 | .87 | |||

| 65–74 y (n = 966) | 231 | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | ||

| ≥ 75 y (n = 2035) | 804 | 0.67 (0.59–0.77) | 0.78 (0.68–0.90) | ||

| All-cause readmission | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | .52 | .69 | |||

| No (n = 2224) | 1360 | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | ||

| Yes (n = 777) | 538 | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | ||

| Renal insufficiency | .69 | .76 | |||

| No (n = 2544) | 1563 | 0.83 (0.75–0.92) | 0.89 (0.81–0.99) | ||

| Yes (n = 457) | 335 | 0.79 (0.64–0.98) | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | .45 | .40 | |||

| No (n = 1916) | 1145 | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) | ||

| Yes (n = 1085) | 753 | 0.78 (0.78–0.90) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | ||

| Age | .07 | .13 | |||

| 65–74 y (n = 966) | 608 | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | 0.80 (0.68–0.94) | ||

| ≥ 75 y (n = 2035) | 1290 | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | ||

| Combined mortality and readmission | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | .23 | .23 | |||

| No (n = 2224) | 1573 | 0.77 (0.70–0.85) | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | ||

| Yes (n = 777) | 613 | 0.86 (0.73–1.00) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | ||

| Renal insufficiency | .43 | .37 | |||

| No (n = 2544) | 1795 | 0.81 (0.74–0.89) | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) | ||

| Yes (n = 457) | 391 | 0.74 (0.61–0.90) | 0.79 (0.64–0.96) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | .74 | .63 | |||

| No (n = 1916) | 1330 | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) | 0.88 (0.79–0.99) | ||

| Yes (n = 1085) | 856 | 0.77 (0.67–0.88) | 0.84 (0.73–0.96) | ||

| Age | .16 | .24 | |||

| 65–74 y (n = 966) | 660 | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | 0.80 (0.69–0.94) | ||

| ≥ 75 y (n = 2035) | 1526 | 0.83 (0.75–0.92) | 0.90 (0.82–1.00) | ||

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Hazard ratios are for 1-year outcomes of β-blocker vs no β-blocker at discharge.

Discussion

This study of clinical effectiveness addresses important questions about heart failure and beta-blockers by linking a large contemporary heart failure registry containing data on clinical characteristics, treatment eligibility, and contraindications and intolerance with long-term outcome data from Medicare claims. The registry includes a broad cohort of patients (including elderly patients) with heart failure from a variety of settings and from all regions of the United States. The registry contains far more detailed information on patient characteristics, presenting symptoms, treatments, and outcomes than has been available in other administrative data sets or registries. We confined the analysis to patients who were eligible for beta-blocker therapy and who did not have documented contraindications, intolerance, or other reasons for not receiving beta-blockers. We found that beta-blockers were clinically effective in patients with LVSD, a population that is older and has more comorbid conditions than populations usually enrolled in randomized clinical trials. Moreover, although patients with preserved systolic function had substantial morbidity and mortality after hospitalization for heart failure, in marked contrast to patients with LVSD, we did not find a substantial benefit of beta-blocker therapy in this cohort.

In comparison with clinical trials, in which the median age was 65 years (4–6, 12), the median age in our study was 78 years, and the patients had significant comorbidity. Beta-blockers were prescribed at discharge for nearly 80% of all eligible patients with LVSD, a striking finding given the prevalence of comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency, and peripheral vascular disease, which are often perceived by practitioners as barriers to beta-blocker therapy. The overall risk in this study population is further highlighted by the 1-year mortality rate of 33%. In contrast, the COPERNICUS trial, which enrolled patients with LVEF < 25%, had an overall mortality rate of 14% during a mean follow-up of 10 months (6). The observed 1-year mortality benefit in this study is especially remarkable, given that eligible patients who were discharged without beta-blocker therapy may have subsequently started treatment and patients discharged on beta-blockers may have discontinued therapy or been nonadherent.

Our findings also highlight the risks of decompensation and cardiovascular and noncardiovascular hospital admissions among patients with failure. We found an all-cause rehospitalization rate of over 60% in the first year. Previous clinical trials that included patients with severe heart failure had rehospitalization rates of less than 30% within 1 year (6). We found a significant reduction in the combination of mortality and all-cause rehospitalization with beta-blocker therapy for patients with heart failure and LVSD, although the major effect was on mortality alone.

We also found that elderly patients with heart failure and preserved systolic dysfunction had very high mortality and morbidity, with a 1-year mortality rate of 32% and a 1-year rehospitalization rate of 65%. Despite the alarming risk, clinical trial data regarding treatment for patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function are sparse. Beta-blockers may be beneficial in patients with preserved systolic function who also have other indications, such as coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension. However, we found no association between beta-blocker therapy at discharge and clinical outcomes in the first year of follow-up in patients admitted with preserved systolic function. There are several possible explanations for the lack of benefit of beta-blockers in this cohort, including the heterogeneity of the population and poor understanding of pathophysiology. The single randomized trial of beta-blockers that included patients with preserved systolic function did not find a mortality benefit in the subgroup of patients with LVEF ≥ 40% (23). Thus, our findings among patients enrolled in OPTIMIZE-HF are consistent with the existing clinical trial evidence. More studies are needed to address this high-risk population and to prospectively test new therapies that could improve outcomes.

Our study strengthens the findings of previous studies by including important clinical characteristics, such as LVEF, and prospective data on eligibility for treatment, including contraindications and intolerance. Go et al (24) analyzed medical records from 2 health care systems to assess the comparative effectiveness of beta-blockers on the risk of rehospitalization for heart failure. After adjustment for risks of admission and propensity to receive beta-blockers, they did not find significant differences in rehospitalization within 12 months for patients on atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, carvedilol, or other beta-blockers. Because the study had limited data on beta-blockers primarily studied in clinical trials and did not have data on LVEF, the importance of evidence-based beta-blockers vs non-evidence-based beta-blockers could not be determined. The striking difference by left ventricular function in the association of beta-blocker therapy with postdischarge outcomes in our study highlights the importance of accurate documentation of left ventricular function for studies of effectiveness in patients with heart failure. The difference also makes it unlikely that observations of improved outcomes in patients with LVSD were simply a result of lower-risk patients being treated with beta-blockers or residual confounding, since these would have applied equally to patients with preserved systolic function.

Our analysis has some limitations. First, hospitals participating in OPTIMIZE-HF are self-selected and may not be representative of national care patterns and clinical outcomes. Second, the follow-up data included were derived from the subset of patients in the registry who were enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare. Third, eligibility for beta-blocker therapy is based on documentation in the medical record and is thus dependent on the accuracy of this documentation. Some patients may have had contraindications or intolerances that were not documented. Fourth, we did not assess exposure to beta-blockers after hospital discharge, and patients discharged without beta-blocker therapy may have started treatment and those discharged with beta-blocker therapy may have discontinued or not fully adhered to therapy after discharge. A prior analysis of OPTIMIZE-HF showed that in a prespecified 10% sample of patients with 60 to 90 days of follow-up, 95% of eligible patients discharged on beta-blocker therapy remained on therapy (25). Any drop-off in beta-blocker therapy would diminish the likelihood of finding a significant difference in postdischarge clinical outcomes, making the findings of a significant difference in survival based on discharge use of beta-blocker therapy more remarkable. Also, we did not assess health-related quality of life, functional capacity, patient satisfaction, or other outcomes that may be of interest; beta-blockers may or may not be associated with these outcomes in clinical practice. Also, we did not have data ascertaining causes of death and rehospitalization. Some studies have suggested that there are differences in mode of death between heart failure patients with reduced and preserved systolic function (26).

The association between beta-blocker therapy and outcomes may be confounded by socioeconomic factors that are not included in the multivariable and propensity models. There may also be other unmeasured confounders that, had they been adjusted for, would have strengthened or weakened the association between beta-blocker use and clinical outcomes. This study was observational, and randomized controlled trials are the best methods for establishing or comparing efficacy of treatment. However, it is unlikely that additional randomized comparisons for beta-blockers either broadly or in special populations, such as patients with preserved systolic function, will be conducted. Thus, our data serve as one of the few resources for improving understanding of clinical effectiveness in patients hospitalized for heart failure.

Conclusions

In an elderly population hospitalized for heart failure, incident beta-blocker therapy at discharge was associated with significantly improved risk and propensity-adjusted survival for patients with LVSD in the first year of follow-up. These findings extend the results of randomized clinical trials of beta-blockers conducted in selected outpatients with chronic systolic heart failure to a diverse cohort of patients hospitalized with heart failure and LVSD. Patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function have poor outcomes, and beta-blockers do not substantially influence the risk of death or rehospitalization in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr Hernandez is a recipient of an American Heart Association Pharmaceutical Roundtable grant (0675060N). Drs Curtis and Schulman were supported in part by grant 1R01AG026038-01A1 from the National Institute on Aging and grant 5U01HL66461-05 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr Fonarow holds the Eliot Corday Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine and Science at the David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles.

We thank Damon M. Seils, MA, of Duke University for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation. Mr Seils did not receive compensation for his assistance apart from his employment at the institution where the study was conducted.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- CI

confidence interval

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVSD

left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- OPTIMIZE-HF

Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) Lancet. 1999;353:2001–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1651–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1682–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DS, Mamdani MM, Austin PC, et al. Trends in heart failure outcomes and pharmacotherapy: 1992 to 2000. Am J Med. 2004;116:581–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezekowitz J, McAlister FA, Humphries KH, et al. The association among renal insufficiency, pharmacotherapy, and outcomes in 6,427 patients with heart failure and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee DS, Tu JV, Juurlink DN, et al. Risk-treatment mismatch in the pharmacotherapy of heart failure. JAMA. 2005;294:1240–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel P, White DL, Deswal A. Translation of clinical trial results into practice: temporal patterns of beta-blocker utilization for heart failure at hospital discharge and during ambulatory follow-up. Am Heart J. 2007;153:515–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2004;148:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Influence of a performance-improvement initiative on quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: results of the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1493–1502. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2217–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis LH, Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Schulman KA. Validity of a national heart failure quality of care registry: comparison of Medicare patients in OPTIMIZE-HF versus non-OPTIMIZE-HF hospitals. Circulation. 2007;115:e595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.822692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Carvedilol use at discharge in patients hospitalized for heart failure is associated with improved survival: an analysis from Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Am Heart J. 2007;153:82.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1998;16:1141–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anstrom KJ, Tsiatis AA. Utilizing propensity scores to estimate causal treatment effects with censored time-lagged data. Biometrics. 2001;57:1207–18. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Adjusted survival curves with inverse probability weights. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, Hume AL, Mor V. Principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:841–53. doi: 10.1002/pds.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS) Eur Heart J. 2005;26:215–25. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Go AS, Yang J, Gurwitz JH, Hsu J, Lane K, Platt R. Comparative effectiveness of beta-adrenergic antagonists (atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, carvedilol) on the risk of rehospitalization in adults with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:690–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Prospective evaluation of beta-blocker use at the time of hospital discharge as a heart failure performance measure: results from OPTIMIZE-HF. J Card Fail. 2007;13:722–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.06.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henkel DM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Roger VL. Death in heart failure: a community perspective. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2008;1:91–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.107.743146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.