Abstract

Phosphorylation of membrane proteins is a central regulatory and signaling mechanism across cell compartments. However, the recognition process and phosphorylation mechanism of membrane-bound substrates by kinases are virtually unknown. cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) is a ubiquitous enzyme that phosphorylates several soluble and membrane-bound substrates. In cardiomyocytes, PKA targets phospholamban (PLN), a membrane protein that inhibits the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). In the unphosphorylated state, PLN binds SERCA, reducing the calcium uptake and generating muscle contraction. PKA phosphorylation of PLN at S16 in the cytoplasmic helix relieves SERCA inhibition, initiating muscle relaxation. Using steady state kinetic assays, NMR spectroscopy, and molecular modeling we show that PKA recognizes and phosphorylates the excited, membrane detached R state of PLN. By promoting PLN from a ground state to excited state, we obtained a linear relationship between rate of phosphorylation and population of the excited state of PLN. The conformational equilibrium of PLN is crucial to regulate the extent of PLN phosphorylation as well as SERCA inhibition.

INTRODUCTION

Protein phosphorylation is a central mechanism in cell signaling and regulation. Inhibitory proteins are reversibly phosphorylated to cycle between active and inactive states1. These different states are characterized by conformational and dynamic transitions that are essential for stability and function2, 3. Muscle proteins are salient examples of these structure-dynamics-function correlations. The rhythmic contraction and relaxation of the heart muscle, for instance, are orchestrated by protein complexes that regulate calcium homeostasis, and phosphorylation is the driving force to control these cyclic events4.

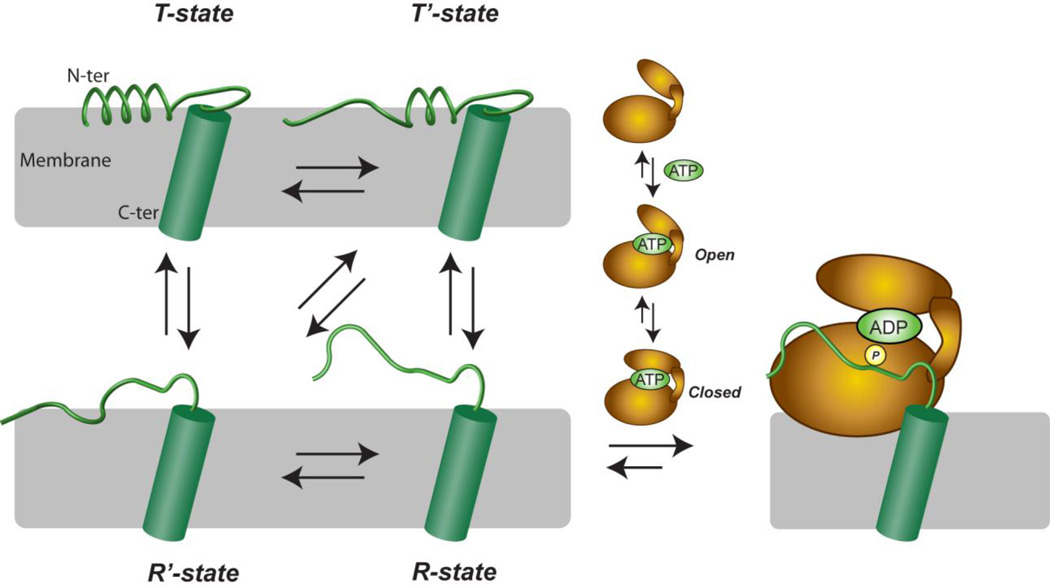

In muscle cell membranes, protein kinases target peripheral membrane proteins or small membrane proteins involved in regulatory complexes, initiating signaling events that cross the membrane bilayer,4. This is the case of phospholamban (PLN), a reversible inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA)5, 6. SERCA is a 110 kDa membrane-embedded ATP-driven calcium pump and is regulated by intramembrane interaction with PLN. In its storage form, PLN exists in a pinwheel pentameric assembly that de-oligomerizes upon interaction with SERCA5, 7. PLN comprises multiple dynamic domains: the inhibitory domains include the transmembrane segment (domain II) and the juxtamembrane domain Ib8–12, while the regulatory elements include a short dynamic loop and an amphipathic helix (domain Ia) that interacts reversibly with the membrane and contains the PKA recognition sequence13, 14. Domain Ia of PLN exists in at least four conformational states: T-state (membrane attached and helical), T'-state (membrane attached, partially helical), R'-state (membrane attached, unfolded) and R-state (membrane detached, unfolded).6, 11, 15. PLN phosphorylation at Ser 16 by PKA in domain Ia is sufficient to reverse SERCA inhibition and increase the enzyme affinity for calcium that is pumped into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, initiating muscle relaxation16. Disruptions in this phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle lead to pathologies such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)17.

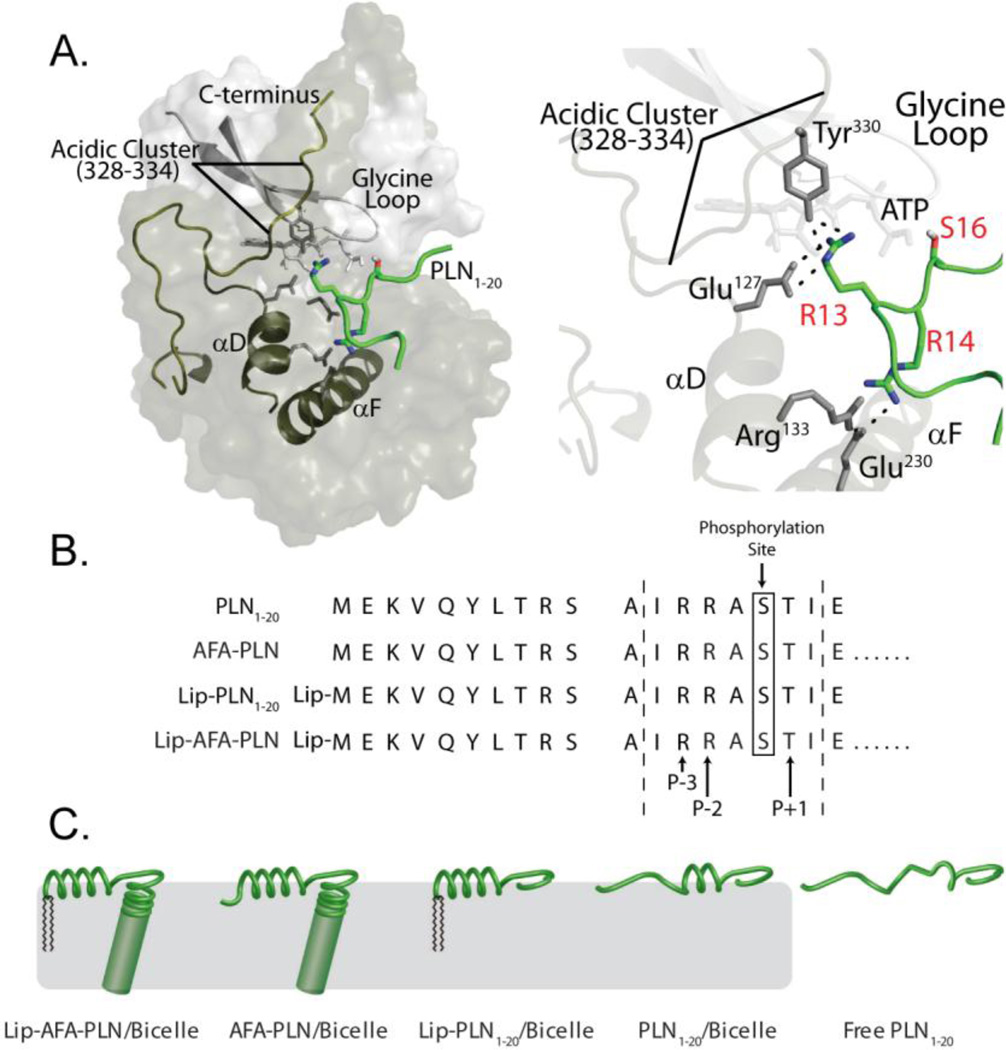

Once unleashed from its tetrameric assembly by cyclic-adenosine monophosphate18, the monomeric catalytic subunit of PKA (PKA-C) recognizes, binds, and phosphorylates PLN. The molecular mechanisms of PLN recognition by PKA are still elusive. Recent NMR and X-ray data on PKA-C in a ternary complex with nucleotide and the cytoplasmic domain of PLN suggest that binding by PKA-C may involve an unfolding of PLN domain Ia (Figure 1A)2. This result is striking given that in several membrane mimics the most populated state for the full-length PLN is folded, with the majority of the recognition sequence in close proximity with the lipid membrane7–9, 12, 19, 20.

Fig. 1.

A) Crystal structure of PKA-C bound to PLN1–20 showing the key contacts between substrate (green) and enzyme (grey) within the binding groove. B) Primary structures and C) cartoon representations of the different analogs used to mimic the T and R states of PLN.

To gain insights into the recognition mechanism of PKA-C for PLN, we used a combination of steady state kinetic assays, NMR, and molecular modeling. We show that PKA-C preferentially binds and phosphorylates a membrane detached and unfolded conformation of PLN, corresponding to the excited R state of this protein15. Using a series of PLN variants in different lipid environments, we tuned the extent that domain Ia of PLN interacts with the membrane. We found a linear correlation between the catalytic efficiency of phosphorylation and the population of membrane detached and unfolded domain Ia of PLN. Molecular modeling from NMR data shows that the kinase binds an extended conformation of PLN in solution. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the conformational equilibrium of PLN is an important requirement for efficient phosphorylation by PKA and activation of SERCA.

RESULTS

PKA-C selects an extended conformation of PLN

To understand if PKA-C has a preference for the different conformational states of PLN, we prepared several PLN analogs which mimicked different populations of the ground and excited states of the cytoplasmic domain Ia (Figure 1B,C). The first PLN analog was obtained by synthetic incorporation of dialkyl 1', 3'-dioctadecyl-N-succinyl-L-glutamate (Lip) to the N-terminus of full-length PLN. This analog has been shown to skew the equilibrium toward the well-folded, membrane associated T-state, anchoring domain Ia to the lipid membrane21. On the other hand, to mimic the membrane detached, unfolded R-state, we synthesized a peptide corresponding to the cytoplasmic domain Ia (PLN1–20) and studied it in the absence of any membrane mimicking environment. Under these conditions, PLN1–20 is an intrinsically disordered polypeptide as probed by circular dichroism, NMR chemical shifts, and nuclear spin relaxation measurements2 (Figure S1). To mimic the gradual progression from a full T-state to the R-state, synthetic and recombinant versions of full-length PLN with no lipidation, as well as a lipidated peptide corresponding to domain Ia of PLN (Lip-PLN1–20) were used. Finally, since full-length PLN reconstituted in dodecylphosphocholine micelles has been well characterized by our laboratory, we also included this form in our studies.

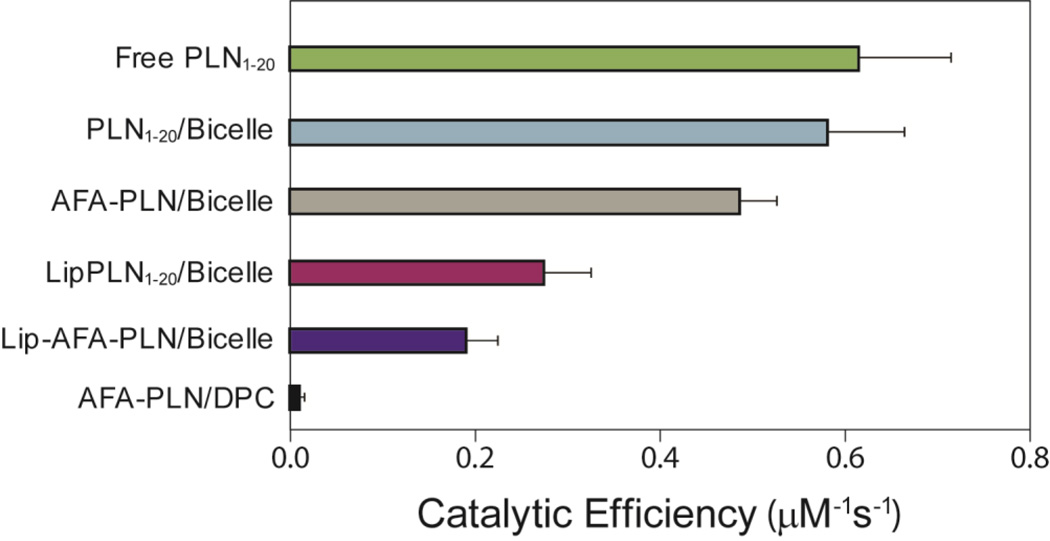

For each of the PLN analogs, PKA-C catalyzed steady-state phosphorylation assays were performed and the Michaelis-Menten constants were measured. Although all reactions eventually reached completion and displayed similar values for kcat (Table S1), the Km values for the reactions differed significantly. Specifically, PLN1–20 in the absence of membranes was phosphorylated with a high catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km ~0.6 µM−1s−1), while full-length PLN in DPC micelles was phosphorylated with a low catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km ~0.06 µM−1s−1). A variety of intermediate catalytic efficiencies were measured for the phosphorylation of PLN analogs in different conditions as reported in Figure 2. The trend in catalytic efficiencies agrees qualitatively to an increasing population of R-state in PLN.

Fig. 2.

Structure-function correlations for PLN analogs. The catalytic efficiency of the kinase increases with the increase of the R-state population. The errors were propagated from least-squares fitting analysis. Each data point in the Michaelis-Menten plot represented an average of triplicate measurements.

To provide a more quantitative analysis for the T-state population of the PLN analogs, the degree of folding for each was characterized using NMR. As reported previously2, the PLN peptide constitutes a good mimic of the cytoplasmic domain of full-length PLN as verified by chemical shift indices (CSI) and secondary structure propensity (SSP) values. Our laboratory has shown that the cytoplasmic domain of PLN is mainly α-helical (~4% R-state)22 in DPC micelles15. CSI and secondary structure propensity scores for PLN1–20 in the presence of DPC micelles agreed well with those findings, indicating that the peptide forms a stable α-helix (Figure S1). In fact, only small differences were detected between the cytoplasmic regions of both constructs. The latter demonstrates that PLN1–20 closely mimics the cytoplasmic region of the full-length protein.

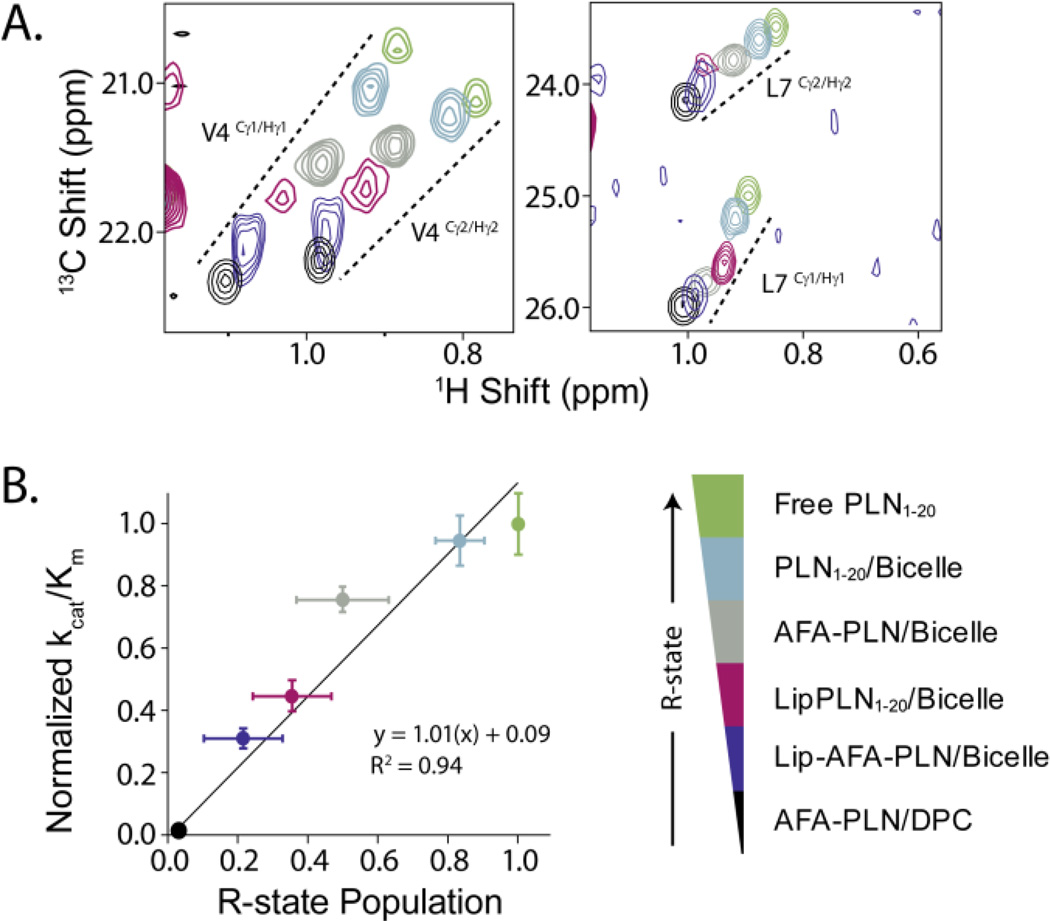

Our laboratory has shown that the chemical shifts of methyl-bearing sidechains of the PLN cytoplasmic domain provide excellent probes for the T- and R-states of the protein15. Using these probes, we measured the chemical shift positions of the methyl groups for each of the PLN analogs under similar conditions as the steady-state assays. The methyl groups showed a linear trend between the PLN1–20 free in solution (100% R-state15) and PLN in DPC micelles (~4% R-state22, (Figure 3A). The other analogs represented different intermediates between these two extremes, illustrating that these species gradually shift the population of the R-state toward the T-state (Figure 3A). Validating this trend in folding, CD spectroscopy measurements on PLN1–20 based analogs revealed a gradual increase in α-helical content in the presence of bicelles and, in particular, when lipidated. We therefore used the position of the methyl resonances as reporters for the extent of unfolding to quantify the R-state for these analogs (Figure 3B). As expected, the comparison of PLN and Lip-PLN in isotropic bicelles showed a decrease in the R-state for Lip-PLN, consistent with the trends observed by CD spectroscopy.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative relationship between the extent of R-state and phosphorylation efficiency. A) Selected regions of the methyl-TROSY NMR spectra for the different PLN analogs display a linear trend in the chemical shifts from the T to R state. B) Linear relationship between the population of Rstate of the PLN analogs and their respective phosphorylation kinetics. Errors in % R-state reflect the spread of populations estimated from the position of 12 chemical shifts. 13C and 1H chemical shifts from residues V4, L7, and I12 were used as probes of the R-state population.

A quantitative relationship between the efficiency of phosphorylation and the population of the membrane detached state (full R-state) of PLN was identified when we plotted kcat/KM against the population of R-state (Figure 3B). Notably, the extent of unfolded R-state is linearly correlated with increased phosphorylation efficiency. These results demonstrate that PKA-C preferentially binds and phosphorylates the membrane detached conformation of PLN.

Molecular modeling of PLN1–20 bound to PKA-C

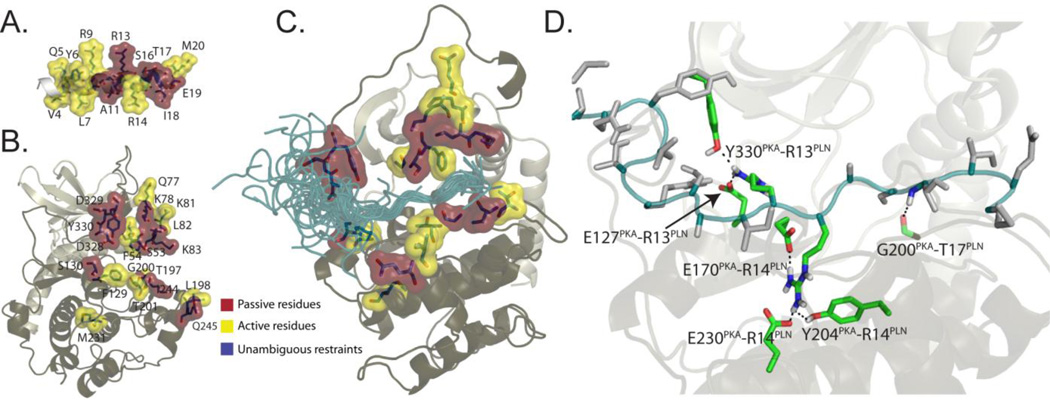

To investigate how PKA-C recognizes and binds PLN and to characterize the protein-protein interface, we used a combination of NMR, mutagenesis, and sequence homology data to model the complex between enzyme and substrate. Chemical shift perturbation profiles in both the substrate and enzyme were analyzed to provide harmonic distance restraints for the molecular model of the complex. Perturbations in PLN1–20 resonances were almost exclusively localized to the recognition region for PKA-C upon titration with the enzyme. These perturbations were used as restraints for modeling the molecular complex. As for our previous titrations with Kemptide23, residues perturbed in PKA-C upon titration with PLN1–20 are located in the immediate vicinity of the substrate binding groove as well as residues in remote regions of the enzyme. Substantial chemical shift perturbations are observed in the glycine-rich (residues 50–55), DFG (residues 185–187), activation (residues 190–197), and P + 1 (residues 198–205) loops. Distal sites are also affected: residues 30, 31, and 36 which lie toward the N-terminus, and residues 145, 146, 148, and 156 of the E Helix. Perturbations are also apparent for residues 163 and 164 of β6, 271 in the loop connecting H and I helices as well as residue 315 near the C-terminus.

In the membrane-free conformation, the PLN1–20 peptide is mostly unstructured, with chemical shifts displaying characteristics of an intrinsically disordered polypeptide24–26. The negative [1H,15N]-heteronuclear nuclear Overhauser effect (H-X NOE) values and the uniformity of the R2/R1 ratios indicate that in solution PLN1–20 is flexible, monomeric, and reorients relatively fast27. When bound to PKA-C, the substrate does not show a defined secondary structure (α-helical or β-sheet conformations), as demonstrated by the relatively small changes in the chemical shift perturbation plot as well as the chemical shift indices for the13Cα/13Cβ resonances (Fig. S2), supporting the previously published crystallographic structure2.

In addition to the chemical shift perturbation-derived restraints, we used the coordinates from crystal structure of PKA-C in the closed conformation to model the complex. Since PLN1–20 has sequence similarity with protein kinase inhibitor (PKI), the endogenous PKA-C inhibitor, we aligned the PLN recognition sequence in the PKA-C binding groove as defined by the crystal structure (1ATP) bound to PKI5–24 and ATP28. We oriented the side chain of the phosphorylation site (S16) of PLN1–20 toward the γ-phosphate of the ATP molecule. Chemical shift perturbations for PKA-C indicated that many areas distal to the binding site were perturbed by allosteric effects. Therefore, the crystal structure of PKA-C bound to PKI5–24 was used to filter out these long range effects, considering only those residues in PKA-C with large chemical shifts (greater than the median value) and within 10 Å radius in the binding pocket defined by PKI5–24 (Figure 4B). The PKA-C crystal structure depleted of PKI5–2429 was used as the initial structure and held fixed during simulated annealing calculations. The NMR data were implemented as harmonic distance restraints30. PLN1–20 was modeled starting from a helical conformation8, 12 and was allowed to be fully flexible during the docking protocol. The final model of the complex is reported in Fig. 4C. The ensemble of the PLN1–20 conformers is in an extended conformation within the enzyme binding pocket. Taken with the kinetics experiments, this model supports the hypothesis that the enzyme selects an extended conformation from the ensemble of states sampled by PLN. This extended conformation has its recognition sequence fully accessible and detached from the membrane surface.

Fig. 4.

Hybrid X-ray and NMR-based molecular model of the complex between PLN1–20 and PKA-C. Active (red) and passive (yellow) residues are indicated for A) PLN1–20 and B) PKA-C. C) Twenty lowest conformers generated with HADDOCK30. D) Atomic details of the interactions observed between PKA-C and PLN1–20 based on the molecular model

DISCUSSION

Based on phosphorylation kinetic assays, NMR data, and molecular modeling, we propose a recognition model for PLN as reported in Figure 5. Since both PLN and PKA-C undergo conformational equilibria between ground and excited states2, 3, 11, 15, 31, the recognition model exemplifies the recently theorized extended conformational selection model, where the two binding partners affect each other, with a mutual adjustment process and changing both energy landscapes32. In fact, PLN exists in equilibrium between four major conformational states, driven by the reversible binding of the cytoplasmic domain Ia to the membrane. The T-state (L-shaped configuration), with domain Ia adsorbed on the membrane surface is the most populated and represents the ground state of PLN, while the remaining three states (T’, partially unfolded in domain Ib, R’ partially unfolded at the N-terminus and in the C-terminal part of domain Ia, and an R-state, which has domain Ia and Ib unfolded) are less populated and represent the excited states. In the ground state, PLN is less accessible to the protein kinase and is poorly phosphorylated, whereas the excited R-state comprises an ensemble of conformations from which PKA-C selects the extended conformation that molds into the substrate binding site. On the other hand, PLN binding drives PKA-C conformational equilibrium toward the closed state of the enzyme as probed by both X-ray and NMR spectroscopy2, 3.

Fig. 5.

Extended conformational selection model for PLN recognition by PKA-C. Both PKA-C and PLN have been shown to undergo conformational exchanges. PKA-C undergoes a global change which opens and closes its active site upon interaction with the nucleotide. This likely facilitates efficient binding of PLN, shown previously2. PLN also undergoes conformational fluctuations11, 15. Unfolding of the cytoplasmic portion of PLN and detachment from the membrane facilitates the recognition and subsequent phosphorylation by PKA-C

The folding/unfolding transitions of PLN are relatively fast11 and the phosphorylation efficiency is proportional to the population of the most excited state (R), in which the helix of domain Ia is melted. In contrast, for the most helical construct studied, (PLN in DPC micelles), the conformational equilibrium is skewed toward the full T-state and the phosphorylation efficiency is drastically lower.

The overall phosphorylation efficiency trends for both the peptide and full-length protein mirror one another, demonstrating that the cytoplasmic portion of the protein is a good model for the full protein. This latter result supports the selection of the peptide to model the molecular complex of PKA-C/ATP/PLN1–20. Using chemical shift changes which occurred upon formation of the Michaelis complex for both PKA-C and PLN1–20, sequence homology with the high affinity inhibitor peptide of PKA-C, and results from mutations, we modeled the PKA-C/PLN1–20 complex. This complex indicates that PKA-C binds an unfolded conformation of PLN. Initial molecular dynamics simulations (data not shown) indicate that this complex is stable, with the recognition sequence of PLN1–20 confined to the active site of the enzyme and regions outside of this remaining relatively mobile. This matches well with our previous nuclear spin relaxation measurements of the bound peptide, which indicated high mobility across the substrate backbone, with the exception of the recognition sequence which was more ordered2.

The conformational dynamics of the cytoplasmic domain of PLN is reminiscent of the binding-and-folding model proposed for amphipathic helices of membrane proteins33, 34. According to this model, interactions with the membrane bilayer surface (likely driven by electrostatic residues) causes the amphipathic peptide to insert and fold onto the membrane with the hydrophobic face pointing toward the hydrocarbon region of the membrane bilayer and the hydrophilic face toward the lipid headgroup/water interface. In addition to regulating the extent of PLN interaction with the membrane bilayer, a similar binding-and-folding mechanism is probably present between PLN and SERCA in the inhibitory complex8. As suggested by NMR and electron paramagnetic resonance studies, phosphorylation probably shifts the conformational equilibrium toward a non-inhibitory state of PLN, affecting the stability of domains Ia and Ib. We are currently investigating this hypothesis.

The reversible folding of domain Ia is likely part of a more general class of regulation mechanisms that are mediated by amphipathic domains35, 36. For instance, a parallel can be made with the autoinhibitory process that takes place in Vav, a multidomain protein that is negatively regulated by its DH domain37. In Vav, autoinhibition is reversibly modulated by a folding/unfolding equilibrium of the amphipathic DH-helix, which fluctuates between a protein free and bound conformation. This equilibrium is shifted toward the unfolded state upon phosphorylation at Tyr174. Phosphorylation efficiency was correlated with unfolding of this amphipathic domain. Another example is LOV-238, 39. As for Vav, LOV also contains a region which can switch between an amphipathic α-helix and an unfolded conformational state. The conformational equilibrium of this region dictates the inhibitory strength of the protein. These results mirror the current study with PLN, where the catalytic efficiency of the kinase is linearly correlated with the population of the unfolded excited state, which exposes the phosphorylation site to the protein kinase.

This current study demonstrates that the modulation of the cytoplasmic domain to different states affects the ability of PLN to adapt to its binding partner, PKA-C. The ability to interact with other proteins through a population shift highlights the scaffolding capability PLN has for a number of known binding partners: PKA-C, protein phosphatase-1, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, SERCA, HS1-associated protein X-1, and A-kinase anchoring protein 18δ. The coupling of conformational plasticity of the PLN cytoplasmic domain and its interactions with cytosolic proteins (for example, PKA-C) also demonstrates the importance of dynamics for signaling processes to occur efficiently and transiently to facilitate multiple functional interactions40–44. This appears to be particularly important for the case studied here, where a protein links signaling between the cytosolic and membranous environments of the cell.

Finally, this work underscores the role of the complex conformational fluctuations that PLN undergoes to cater to the phosphorylation process by PKA-C and ultimately SERCA regulation. Future studies on the localization of PKA (i.e., role of N-terminal myristoylation and AKAP binding) will elucidate how regulatory domains such as domain Ia of PLN are integrated into macromolecular complexes to achieve signal specificity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) from bovine heart and pyruvate kinase (PK) from rabbit muscle were purchased from Sigma (Solon, OH, USA). Adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP), phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), magnesium chloride, and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Expression and purification of PLN and PLN1–20

PLN1–20 was expressed in E. coli cells as a fusion system with maltose binding protein (MBP) and a 6-histidine tag to facilitate purification45, 46. The cells were grown overnight at 30 °C in LB (Luria Broth) rich media. At OD600 ~ 1.0, cells were transferred into M9 minimum media, containing 15N-labeled NH4Cl or 13C-labeled glucose for uniformly 15N or 13C labeled NMR samples. IPTG (Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside) (0.5 mM) was added to induce fusion protein expression at 37 °C for 5 hours. The pelleted cells were lysed in phosphate buffer (pH = 8.0) in the presence of 6 M guanidine. The cell lysate was separated by centrifugation (18,000 rpm at 4 °C for 40 minutes). The purification of the fusion protein was carried out using Ni2+-NTA resin. The eluted fusion protein was then dialyzed and cleaved with Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease, which separated the PLN1–20 from MBP and the 6-his tag. The final purification was achieved by reversed-phase HPLC using a C-18 column (Vydac). After HPLC purification, approximately 2 mg of PLN1–20 were obtained from 150 mg of fusion protein. The mass of the purified PLN1–20 (2472.8 Da) was confirmed by electrospray ionization time-of-flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectroscopy. The full length PLN was expressed and purified as reported previously46.

Peptide synthesis

The peptide synthesis was performed using standard Fmoc chemistry on an Applied Biosystems Pioneer or CEM Liberty/Discover microwave synthesizer, starting with Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-PEG-PS resin (0.4 g, 0.5 mmol/g). Side chain protecting groups were 2,2,5,78-pentamethylchroman-6-sulfonyl (Pmc) for arginine, Nω-triphenylmethyl (Trt) for asparagine and glutamine, tert-butyl etster (OtBu) for glutamic acid, and tert-butyl ethers (tBu) for serine, threonine, and tyrosine. Addition of the lipid moiety was performed using standard coupling reagents and dialkyl 1', 3'-dioctadecyl-N-succinyl-L-glutamate to the unprotected N-terminal methionine residue47. Cleavage of the resin-bound peptide was done using Reagent K (82.5% trifluoroacetic acid, 5% phenol, 5% thioanisole, 2.5% 1,2-ethandiol, and 5% water) for 3 hours at 298 K. The resin mixture was washed three times (2 ml each) using the same cocktail and filtrate was collected. The peptide was precipitated overnight at 273 K in 80 ml of diethyl ether, then collected by centrifugation and washing the pellet 3 times with 30 ml of diethyl ether. The crude peptide was then purified by preparative HPLC using a Waters C18 reversed-phase cartridge (2.5 × 10 cm, 15 µm 300 Ǻ) with 0.1% TFA and CH3CN as eluents and detection at 220 nm. A linear gradient of 100:0 to 70:30 over 30 minutes at 5 ml/min was used. The purity of pooled fractions was >97% as determined by analytical HPLC using a Vydac C18 column (0.46 × 25 cm) and confirmed by ESI-TOF; for the analog PLN1–20, calculated 2252.65 m/z, found 2252.73m/z. Stock solutions were prepared in water/acetonitrile and lyophilized. The concentrations of these solutions were verified by amino acid analysis.

Kinetic Assays

The steady-state enzymatic rates of phosphorylation for PLN analogs were measured spectrophotometrically at 299 K following the procedure by Cook et al48. Briefly, the oxidation of NADH by pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase is coupled to the production of ADP, which occurs during the PKA-C catalyzed phosphoryl transfer. The reaction rates were monitored at 340 nm using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax Plus384 equipped with a 96-well microplate reader. The reaction solutions contained 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 20 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 5.0 mM ATP, 1.0 mM PEP, 0.2 mM NADH, 12 units LDH, and 4 units PK. For the kinetic assays with lipid bicelles, PEP, NADH, LDH and PK were added after bicelle formation. Stock solutions of 2 mM PLN1–20 were prepared fresh and used immediately. To determine the linear region of PKA-C concentration, PLN1–20 was kept at 300 µM, while PKA-C was varied between 2–728 nM. The reactions were initiated by the addition of PKA-C, which was equilibrated in a solution containing 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 20 mM DTT, and 10 mM MgCl2. No differences in the reaction rates were observed when the substrate was used to initiate these reactions. The measurements were performed in triplicate for each peptide concentration. Rates reflecting the small decrease in absorbance due to intrinsic NADH oxidation were measured and did not exceed ~2% of any reaction studied.

The values of kcat and KM were determined using nonlinear least-squares fitting of the initial velocities versus substrate concentration according to:

| (1) |

Where v is the initial velocity, [S] is the concentration of substrate, Vmax is the maximum velocity for the reaction, and KM is the Michaelis-Menten constant. The value of kcat was taken as Vmax divided by the total PKA-C concentration. Fitting of equation 1 to the kinetics data was performed using the software, Origin 7.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian Inova operating at 800 MHz equipped with an HCN probe. The temperature of the experiments was held constant at 27 °C. Samples were prepared in 20 mM KH2PO4, 180 mM KCl, 1 mM NaN3, 10 mM DTT, and 5% v/v D2O (pH 6.5) at concentrations of ~0.3–0.8 mM. Data were processed with the software NMRPIPE49 and visualized and analyzed using SPARKY50. Populations of the R-state (pR-state) were quantified using:

| (2) |

where Ωx, ΩT-state, and ΩR-state are the chemical shift of sample X, PLN in DPC, and PLN1–20, in aqueous buffer, respectively. The mean of pR-state was determined from six methyl groups in the protein (originating from V4, L7, and I12) which were observed in [1H/13C]-HMQC spectra. Due to poor sensitivity for the bicelle bound states, amide spectra could not be used to estimate the population.

Molecular Modeling

The three dimensional model of the PKA-C/ATP/PLN1–20 complex was generated using HADDOCK 2.030. As an initial configuration, the coordinates from the crystallographic ternary complex of PKA-C/ATP/PKI5–24 (1ATP) was used and depleted of PKI5–2428. The coordinates of the enzyme were kept fixed during the docking of PLN1–20 using simulated annealing. Restraints based on NMR chemical shift were implemented as ambiguous interaction restraints (AIR). Specifically, active residues were categorized as those which had solvent accessibility >50%, chemical shifts perturbations were greater than the median, and within 10 Å from the binding pocket of the enzyme. Active residues indentified were S53, K78, L82, K83, S130, L198, G200, Q245, D328, D329, and Y330. Solvent accessible residues within 3 Å of the active residues were categorized as passive. Active and passive residues were defined for the PLN1–20 using the same criteria. An AIR was satisfied when any atoms of active residues in one molecule were within 4 Å of an active or passive residue of the docking partner. Also, the canonical recognition sequence of PLN1–20 (P−3 to P+1 site) was aligned to match the corresponding positions of PKI5–24 in the binding groove of the 1ATP structure28. Based on this alignment, five additional distance restraints were used: three hydrogen bonds from the R14 guanidinium group of PLN1–20 to E170, Y204, and E230 of PKA-C, one hydrogen bond from S16 of PLN1–20 to S53 of PKA-C, and one hydrogen bond involving the carboxyl group of T17 and the backbone amide of G200 in PKA-C. The hydrogen bond distances (from N or O heteroatoms to hydrogen atoms) were incorporated as NOE distance restraints using a flat well potential with 1.5 (4 Å) as lower (upper) bound distances. PLN1–20 was set to be flexible, with the exception of the residues occupying P−3 to P+1 sites of PKA-C, consistent with results based on NMR dynamics measurements2. The backbone conformation of PKA-C was kept fixed, while full flexibility was allowed for sidechains. The initial structures of PKA-C and peptide were subjected to rigid-body docking and subsequent structure refinement using the docking protocol from HADDOCK with adjusted weighting factors30. A total of 2000 initial structures of the complex were generated after rigid body docking, and the 200 lowest intermolecular energy structures were optimized by simulated annealing, followed by refinement in explicit water using the Tip3 water model30. These structures were then clustered according to their pairwise root-mean square deviations (RMSD) with respect to the conformation of PKI in 1ATP crystal structure. The 20 lowest energy structures were selected for the final analysis.

Supplementary Material

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH Grants GM72701 to GV, T32DE007288 to LRM, and predoctoral fellowship 10PRE3860050 from the Midwest Affiliate American Heart Association to MG. NMR instrumentation at the University of Minnesota High Field NMR Center (NSF BIR-961477), the University of Minnesota Medical School. Modeling and calculations were carried out at the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson LN. The regulation of protein phosphorylation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:627–641. doi: 10.1042/BST0370627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masterson LR, Cheng C, Yu T, Tonelli M, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Dynamics connect substrate recognition to catalysis in protein kinase A. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:821–828. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masterson LR, Shi L, Metcalfe E, Gao J, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Dynamically committed, uncommitted, and quenched states encoded in protein kinase A revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:6969–6974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102701108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:566–577. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traaseth NJ, Ha KN, Verardi R, Shi L, Buffy JJ, Masterson LR, Veglia G. Structural and Dynamic Basis of Phospholamban and Sarcolipin Inhibition of Ca(2+)-ATPase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3–13. doi: 10.1021/bi701668v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verardi R, Shi L, Traaseth NJ, Walsh N, Veglia G. Structural Topology of Phospholamban Pentamer in Lipid Bilayers by a Hybrid Solution and Solid-State NMR Method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016535108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamoon J, Mascioni A, Thomas DD, Veglia G. NMR solution structure and topological orientation of monomeric phospholamban in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2589–2598. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mascioni A, Karim C, Zamoon J, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Solid-state NMR and rigid body molecular dynamics to determine domain orientations of monomeric phospholamban. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9392–9393. doi: 10.1021/ja026507m. ja026507m [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metcalfe EE, Zamoon J, Thomas DD, Veglia G. (1)H/(15)N heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy shows four dynamic domains for phospholamban reconstituted in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biophys. J. 2004;87:1205–1214. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.038844. 87/2/1205 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traaseth NJ, Veglia G. Probing excited states and activation energy for the integral membrane protein phospholamban by NMR CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traaseth NJ, Shi L, Verardi R, Mullen DG, Barany G, Veglia G. Structure and topology of monomeric phospholamban in lipid membranes determined by a hybrid solution and solid-state NMR approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:10165–10170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904290106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmerman HK, Collins JH, Theibert JL, Wegener AD, Jones LR. Sequence analysis of phospholamban. Identification of phosphorylation sites and two major structural domains. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13333–13341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmerman HK, Jones LR. Phospholamban: protein structure, mechanism of action, and role in cardiac function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:921–947. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustavsson M, Traaseth NJ, Karim CB, Lockamy EL, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Lipid-Mediated Folding/Unfolding of Phospholamban as a Regulatory Mechanism for the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maclennan DH. Interactions of the calcium ATPase with phospholamban and sarcolipin: structure, physiology and pathophysiology. J. Muscle Res. Cell. Motil. 2004;25:600–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt JP, Kamisago M, Asahi M, Li GH, Ahmad F, Mende U, Kranias EG, MacLennan DH, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure caused by a mutation in phospholamban. Science. 2003;299:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1081578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. cr000226k [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traaseth NJ, Buffy JJ, Zamoon J, Veglia G. Structural dynamics and topology of phospholamban in oriented lipid bilayers using multidimensional solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13827–13834. doi: 10.1021/bi0607610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traaseth NJ, Verardi R, Torgersen KD, Karim CB, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Spectroscopic validation of the pentameric structure of phospholamban. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:14676–14681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701016104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karim CB, Zhang Z, Howard EC, Torgersen KD, Thomas DD. Phosphorylation-dependent conformational switch in spin-labeled phospholamban bound to SERCA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.051. S0022-2836(06)00250-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zamoon J, Nitu F, Karim C, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Mapping the interaction surface of a membrane protein: unveiling the conformational switch of phospholamban in calcium pump regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:4747–4752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406039102. 0406039102 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masterson LR, Mascioni A, Traaseth NJ, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Allosteric cooperativity in protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:506–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709214104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Equilibrium NMR studies of unfolded and partially folded proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 1998:499–503. doi: 10.1038/739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for elucidation of structure and dynamics in disordered states. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:258–271. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3607–3622. doi: 10.1021/cr030403s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay LE, Torchia DA, Bax A. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knighton DR, Zheng J, Eyck LFT, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Structure of a Peptide Inhibitor Bound to the Catalytic Subunit of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate-Dependent Protein Kinase. Science. 1991;253:414–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1862343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buechler JA, Toner-Webb JA, Taylor SS. Carbodiimides as probes for protein kinase structure and function. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:487–500. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00165-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ha KN, Traaseth NJ, Verardi R, Zamoon J, Cembran A, Karim CB, Thomas DD, Veglia G. Controlling the inhibition of the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase by tuning phospholamban structural dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37205–37214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csermely P, Palotai R, Nussinov R. Induced fit, conformational selection and independent dynamic segments: an extended view of binding events. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability : Physical principles. Annual Review Biophysics Biomolecular Structures. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engelman DM, Chen Y, Chin CN, Curran AR, Dixon AM, Dupuy AD, Lee AS, Lehnert U, Matthews EE, Reshetnyak YK, Senes A, Popot JL. Membrane protein folding: beyond the two stage model. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:122–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01106-2. S0014579303011062 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson JE, Cornell RB. Amphitropic proteins: regulation by reversible membrane interactions (review) Mol. Membr. Biol. 1999;16:217–235. doi: 10.1080/096876899294544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornell RB, Taneva SG. Amphipathic helices as mediators of the membrane interaction of amphitropic proteins, and as modulators of bilayer physical properties. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2006;7:539–552. doi: 10.2174/138920306779025675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li P, Martins IR, Amarasinghe GK, Rosen MK. Internal dynamics control activation and activity of the autoinhibited Vav DH domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao X, Rosen MK, Gardner KH. Estimation of the available free energy in a LOV2-J alpha photoswitch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nash AI, Ko WH, Harper SM, Gardner KH. A conserved glutamine plays a central role in LOV domain signal transmission and its duration. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13842–13849. doi: 10.1021/bi801430e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velyvis A, Yang YR, Schachman HK, Kay LE. A solution NMR study showing that active site ligands and nucleotides directly perturb the allosteric equilibrium in aspartate transcarbamoylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:8815–8820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703347104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boehr DD, Nussinov R, Wright PE. The role of dynamic conformational ensembles in biomolecular recognition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kern DZER, E R. The role of dynamics in allosteric regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selvaratnam R, Chowdhury S, VanSchouwen B, Melacini G. Mapping allostery through the covariance analysis of NMR chemical shifts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:6133–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017311108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhabha G, Lee J, Ekiert DC, Gam J, Wilson IA, Dyson HJ, Benkovic SJ, Wright PE. A dynamic knockout reveals that conformational fluctuations influence the chemical step of enzyme catalysis. Science. 2011;332:234–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1198542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masterson LR, Bortone N, Yu T, Ha KN, Gaffarogullari EC, Nguyen O, Veglia G. Expression and purification of isotopically labeled peptide inhibitors and substrates of cAMP-dependant protein kinase A for NMR analysis. Protein Expr. Purif. 2009;64:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buck B, Zamoon J, Kirby TL, DeSilva TM, Karim C, Thomas D, Veglia G. Overexpression, purification, and characterization of recombinant Ca-ATPase regulators for high-resolution solution and solid-state NMR studies. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;30:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lockwood NA, Tu RS, Zhang Z, Tirrell MV, Thomas DD, Karim CB. Structure and function of integral membrane protein domains resolved by peptide-amphiphiles: application to phospholamban. Biopolymers. 2003;69:283–292. doi: 10.1002/bip.10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cook PF, Neville ME, Vrana KE, Hartl FT, Roskoshi R. Adenosine Cyclic 3'5'-Monophosphate Dependent Protein Kinase: Kinetic Mechanism for the Bovine Skeletal Muscle Catalytic Subunit. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5794–5799. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California; [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.