Abstract

Most couples begin marriage intent on maintaining a fulfilling relationship, but some newlyweds soon struggle while others continue to experience high levels of satisfaction. Do these diverse outcomes result from an incremental process that unfolds over time, as prevailing models suggest, or are they a manifestation of initial differences that are largely evident at the start of the marriage? Using eight waves of data collected over the first 4 years of marriage (N = 502 spouses, or 251 newlywed marriages), we tested these competing perspectives first by identifying three qualitatively distinct relationship satisfaction trajectory groups and then by determining the extent to which spouses in these groups were differentiated on the basis of (a) initial scores and (b) 4-year changes in a set of established predictor variables, including relationship problems, aggression, attributions, stress, and self-esteem. The majority of spouses exhibited high, stable satisfaction over the first four years of marriage, whereas declining satisfaction was isolating among couples with relatively low initial satisfaction. Across all predictor variables, initial values afforded stronger discrimination of outcome groups than did rates of change in these variables. Thus, readily-measured initial differences are potent antecedents of relationship deterioration, and studies are now needed to clarify the specific ways in which initial indices of risk come to influence changes in spouses’ judgments of relationship satisfaction.

Keywords: Longitudinal, marriage and close relationships, marital satisfaction

Nearly all newly married couples seek to maintain a stable and fulfilling relationship. Many couples achieve this goal, but the fact that divorce peaks in the first few years of marriage (Bramlett & Mosher, 2001) indicates that many others struggle to say connected. Given similar initial aspirations, why do couples go on to experience such dramatically different outcomes?

One of two theoretical perspectives is typically adopted to answer this question. The dominant approach suggests that marital satisfaction develops over time as a function of the gradual accumulation of small changes in marital processes that arise as couples negotiate differences of opinion, normative developmental challenges, and unexpected stresses. An alternative approach focuses not on changes in relationship processes over time, but on initial differences that characterize partners from the outset of the marriage. Here, marital processes and judgments about the quality of the relationship are assumed to be downstream manifestations of early risk, which is assumed to be essentially intact and evident in the beginning of marriage. Given the importance of reconciling these two views for understanding, predicting, and preventing relationship distress, the current study examined the extent to which initial differences and incremental changes in key relationship variables served to distinguish couples who experienced distinct patterns of change in relationship satisfaction in the first four years of marriage.

Identifying Patterns of Change in Newlyweds’ Marital Satisfaction over Time

Clarifying the dependent variable itself may be a crucial first step in testing different explanations for how relationships change. Although the average spouse appears to be highly satisfied at the outset of marriage before gradual declines in happiness set in (e.g., Kurdek, 1998; VanLaningham, Johnson, & Amato, 2001), alternative approaches to studying change in satisfaction suggest that this mean pattern may mask distinct types of satisfaction trajectories. Using cluster analysis, Belsky and Hsieh (1998) found that although ten percent of spouses exhibited the expected pattern of high initial levels of love followed by gradual declines from year 5 to year 8 of marriage, approximately half of spouses were in a “stays good” group, in which their high levels of love remained stable. Another forty percent were in “stays bad” or “bad-to-worse” groups, characterized by low levels of love that remained stable or declined. Recent work has extended these findings by using group-based mixed modeling (e.g., Nagin, 1999) to examine distinct sets of trajectory patterns over time. A study of 232 newlywed couples in their first marriages found that although the mean pattern of change over the first four years of marriage was one of decline, this effect obscured important variability in patterns of couples’ satisfaction (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010): the majority of spouses exhibited high levels of satisfaction and minimal, if any, declines over the first four years of marriage, whereas moderate-to-large declines in satisfaction were isolated to a small subset of the sample that began with relatively low levels of initial satisfaction. Twenty-year patterns of marital happiness among continuously married individuals similarly indicate that the majority of spouses reported high, stable levels of marital happiness over time; again, change was isolated among approximately 20% of spouses who began with lower levels of marital happiness (Kamp Dush, Taylor, & Kroeger, 2008; Anderson, Van Ryzin, & Doherty, 2010). These findings suggest that there are distinct patterns of change in marital satisfaction, and that starting values and rates of change are closely linked, such that high initial levels foreshadow stable high trajectories while lower initial levels precede more rapid declines in satisfaction.

The first aim of the present study was to replicate these findings using another newlywed sample and another satisfaction measure to confirm that meaningful variability in patterns of change in global satisfaction can be identified among newlyweds. To address this aim, mixture-modeling techniques (Nagin, 1999) were applied to 8 waves of marital satisfaction collected over 4 years from 502 newlywed spouses in 251 marriages to identify groups of spouses with similar trajectories of global satisfaction1. Based on prior research (e.g., Anderson et al., 2010; Lavner & Bradbury, 2010), we predicted that (a) the majority of newlywed couples would show high, stable levels of satisfaction over time, (b) declines in satisfaction would be observed primarily among those individuals with moderate or low levels of initial satisfaction, with these declines being most severe among the individuals with the lowest initial satisfaction, and (c) rates of divorce would be highest among partners with lower average levels of satisfaction and faster rates of decline.

Accounting for Variability in Marital Satisfaction over Time: Exploring Initial Differences versus Changing Processes

If, in fact, qualitatively distinct satisfaction trajectories can be identified, a critical question is why partners follow these different pathways. Existing work suggests that initial differences in multiple domains of functioning underlie newlyweds with different marital trajectories. Specifically, in a 4-year study, spouses who went on to experience less satisfying marital trajectories were characterized by global deficits in interpersonal communication, aggressive behavior, stress, and difficult personality traits six months into marriage, whereas individuals with stable, satisfied trajectories were characterized by global strengths in these domains (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010). Similarly, initial differences in the strength of the romantic relationship (e.g., feelings of love and ambivalence, expressions of negativity) distinguished newlyweds who went on to have satisfied relationships after thirteen years of marriage from those newlyweds who went on to have less satisfied relationships (Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001). These findings support an initial differences model in which troubled relationships should be distinguishable on the basis of risk in multiple domains early in couples’ marital trajectories.

An alternate view suggests, however, that different marital trajectories are due to differential incremental changes in how spouses experience their marriages over time. For example, social exchange theory posits that “relationships grow, develop, deteriorate, and dissolve as a consequence of an unfolding social-exchange process, which may be conceived as a bartering of rewards and costs both between the partners and between members of the partnership and others" (Huston & Burgess, 1979, p. 4). Even social ecological models, which notably draw attention to how the external context affects relationships, emphasize a gradual process whereby “minor stresses originating outside the relationship and spilling over into marriage are particularly deleterious for close relationships as these stresses lead to mutual alienation and slowly decrease relationship quality over time” (Randall & Bodenmann, 2009, p. 108). Consistent with these views, changes in aggression predict changes in relationship satisfaction (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007), as do changes in stress (Karney, Story, & Bradbury, 2005). Thus, in contrast to the initial differences model, the incremental change model suggests that different marital trajectories should be due to differential changes in risky processes over time.

Given these competing theoretical perspectives regarding why spouses eventually differ in their satisfaction, our second aim was to examine trajectories of risk in relation to the different marital satisfaction that we expected to identify under our first aim. Multiwave assessment of risk is necessary to test whether changes in these predictor variables track changes in relationship outcomes in the manner proposed by incremental change models, or whether newlyweds with different marital trajectories differ more in initial risk.

Because we sought an inclusive set of risk variables to test the relative contributions of their intercepts and slopes to relationship change, we drew on the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) to identify a set of time-varying risk factors. The VSA model posits that changes in relationship satisfaction are governed by the quality of couple interaction and their cognitive appraisals, the stresses couples encounter, and the traits partners bring to marriage. Tapping each of these dimensions, risk factors in this study thus included relationship problems, verbal aggression, negative attributions, acute stress, and self-esteem.

If, in fact, initial differences underlie different marital outcomes, early risk in each of these domains should distinguish partners with different marital trajectories (replicating Lavner & Bradbury, 2010). If, however, different marital trajectories are due more to differential changes in risk factors over time, then individuals with different marital trajectories should differ in their slopes of these variables over time2. Specifically, groups marked by declining satisfaction should exhibit increasing levels of risk over time, whereas groups marked by stable satisfaction should exhibit stable or declining levels of risk over time. For example, groups declining in satisfaction should show increased verbal aggression, and groups maintaining satisfaction should show stable or decreased verbal aggression.

Method

Participants

Two studies were conducted in a central Florida community surrounding a major state university (Ns = 82 couples and 169 couples). In both studies, couples were recruited with (a) advertisements in community newspapers and bridal shops and (b) invitations sent to eligible couples who had completed marriage license applications in the county. All couples were screened for eligibility in a telephone interview. Inclusion required that this was the first marriage for each partner; the couple had been married less than 6 months; each partner was at least 18 years of age; each partner spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires); couples did not have children; and wives were not older than 35. Eligible couples, after providing oral consent, were scheduled for an initial laboratory session.

Participants were of comparable age across samples, with spouses in their mid-20s and husbands being slightly older than wives on average (Table 1). The majority of participants were Caucasian (> 80%) and Christian (> 60%). Accordingly, we combined the samples because all couples met identical selection criteria; the studies used highly similar procedures, measures, and designs; and doing so afforded more power and likely elimination of small, spurious subgroups.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Age |

Years of education |

Full-time employed |

Full-time student |

Yearly income |

Caucasian |

Christian |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse | M | SD | M | SD | (%) | (%) | Mdn. | SD | (%) | (%) |

| Sample 1 (N = 82 Couples) | ||||||||||

| Husband | 25.12 | 3.32 | 16.43 | 2.22 | 40% | 54% | $5K–$10K | $4.83K | 83% | 59% |

| Wife | 23.67 | 2.77 | 16.35 | 1.77 | 39% | 50% | $5K–$10K | $4.41K | 89% | 59% |

| Sample 2 (N = 169 Couples) | ||||||||||

| Husband | 25.53 | 4.13 | 16.48 | 2.33 | 59% | 35% | $5K–$10K | $7.21K | 94% | 66% |

| Wife | 23.84 | 3.60 | 16.32 | 2.01 | 45% | 43% | $0K–$5K | $5.41K | 86% | 63% |

Note. The relatively low income level of participants reflects the fact that a large proportion were full-time students at the baseline assessment.

Procedure

Before their laboratory session, participants were mailed questionnaires to complete at home and bring with them to their appointment, with a letter instructing partners to complete all questionnaires independently. Upon arriving at the session, spouses completed a written consent form approved by the local human subjects review board, and then participated in problem-solving discussions and completed additional measures. Couples were then paid for participating (Sample 1 = $50, Sample 2 = $70).

At approximately 6-month intervals subsequent to the initial assessment, couples were re-contacted by telephone and mailed questionnaires, along with postage-paid return envelopes and a letter of instruction reminding couples to complete forms independently. This procedure was used at all follow-up procedures except at Time 5. At the Time 5 assessment, couples completed questionnaires at home and brought them to the laboratory where they engaged in a variety of tasks beyond the scope of the present study. After completing each phase, couples were mailed a check for participating (Study 1 = $40, Study 2 = $40–$50).

Measures

Marital satisfaction

Marital satisfaction was assessed eight times over the 4 years of each study, once every 6 months. To ensure that global sentiments toward the relationship were not confounded with the level of agreement about specific problem areas (see Fincham & Bradbury, 1987), we used a version of the Semantic Differential (SMD; Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957), a measure of marital satisfaction that assesses global evaluations of the relationship exclusively. This measure asks spouses to rate their perceptions of their relationship on 7-point scales between 15 pairs of opposing adjectives (e.g., bad–good, dissatisfied–satisfied), yielding scores from 15 to 105 such that higher scores reflected more positive satisfaction with the relationship. For both samples, coefficient alpha was > .90 for husbands and for wives across all phases of the study.

Relationship problems

The severity of partners’ relationship problems was assessed eight times over the 4 years, once every 6 months, using a modified version of the Marital Problems Inventory (Geiss & O’Leary, 1981). This measure lists 19 potential problem areas in a marriage (e.g., trust, making decisions) and asks participants to rate each item on a scale from 1 (not a problem) to 11 (major problem). Preliminary analyses indicated that a composite measure formed by summing each spouses’ ratings of each item had high internal consistency (α > .85 for husbands and wives in both samples across all assessments). Thus, we summed specific problem ratings into an overall index of problem severity that could range from 19 to 209.

Verbal aggression

Verbal aggression (e.g., insulting, threatening, saying something to spite the other) was assessed eight times over the 4 years of each study, once every 6 months, using the 6-item Verbal Aggression subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). Each item was rated on a 3-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once, and 2 = twice or more) and summed to create a total measure of verbal aggression. For both samples, coefficient alpha was at least .65 for husbands and .70 for wives across all phases of the study.

Negative attributions

Relationship attributions were assessed eight times over the 4 years of each study, once every 6 months, using the Relationship Attribution Measure (Fincham & Bradbury, 1992). This measure presents spouses with four negative events that are likely to occur in all marriages (e.g., “Your spouse does not pay attention to what you are saying”). For each event, spouses were asked to rate their agreement, on 7-point scales, with several statements reflecting two subscales. The causal attribution subscale examined the perceived locus, globality, and stability of the cause of the negative partner behavior. The responsibility attribution subscale captured the extent to which spouses considered their partners’ behaviors as intentional, selfishly motivated, and blameworthy (see Bradbury & Fincham, 1990, for definitions of these dimensions). Preliminary analyses indicated that a composite index formed by summing across all items from both subscales had good internal consistency (α ~.90 for husbands and for wives across all time points). Thus, all 24 items were combined, resulting in a single score for each spouse with ranging from 24–168. Higher scores indicated more negative attributions.

Acute stress

We assessed external stress at the first six assessments (i.e., every 6 months for the first three years of marriage) by having couples complete a version of the Life Experiences Survey (Sarason, Johnson, & Siegel, 1978), designed to assess life events in the previous 6 months. Sixty-five negative, stressful events were selected, with an emphasis on concrete events likely to occur in a young, married population. Events were grouped to represent nine domains: marriage, work, school, family and friends, finances, health, personal events, living conditions, and legal problems. For each event, spouses were asked to indicate whether the event occurred (0 = no, 1 = yes). To be included in the final composite score, however, the event could not represent a likely consequence of marital satisfaction or marital distress, excluding 14 items (e.g., sexual difficulties). Thus, the measure tapped only those stressors external to (i.e., unlikely to be caused by) the marriage. The final stress score, which could range from 0 to 51, was computed by adding together the number of events that the spouse reported had occurred.

Self-esteem

We assessed spouses’ self-esteem eight times over the four years using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Rosenberg, 1965). Scores on the measure can range from 4 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem (sample item: “I take a positive attitude toward myself”). Internal consistency was high for husbands and wives (α > .80).

Descriptive statistics (M, SD, and N) for all variables at each time point are presented in Tables 2 (husbands) and 3 (wives). In general, consistent with the low risk nature of the sample, spouses tended to report low-to-moderate levels of risk. Risk factors were only weakly intercorrelated with each other (median samplewide correlation = .23; Table 4) and with initial satisfaction (median correlation = .29 for husbands and .34 for wives; Table 4). Study retention was relatively high: accounting for couples who divorced over the course of the study, approximately 90% of couples provided satisfaction data at the final assessment.

Table 2.

Husbands’ Satisfaction and Risk Across Eight Waves of Measurement: Descriptive Statistics (N = 251)

| Time |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Marital satisfaction | ||||||||

| M | 95.81 | 91.90 | 92.17 | 92.44 | 92.23 | 91.88 | 90.19 | 91.45 |

| SD | 9.80 | 13.52 | 13.49 | 12.76 | 14.46 | 14.92 | 15.34 | 13.69 |

| N | 250 | 239 | 235 | 217 | 203 | 172 | 185 | 191 |

| Relationship problems | ||||||||

| M | 51.48 | 52.59 | 49.71 | 50.11 | 50.40 | 51.09 | 55.03 | 49.74 |

| SD | 22.88 | 25.27 | 23.37 | 23.26 | 26.50 | 25.91 | 29.46 | 23.68 |

| N | 248 | 238 | 235 | 217 | 204 | 172 | 184 | 187 |

| Verbal aggression | ||||||||

| M | 5.06 | 4.53 | 4.60 | 4.46 | 4.33 | 4.34 | 4.04 | 3.80 |

| SD | 4.06 | 3.92 | 3.80 | 3.87 | 4.12 | 3.95 | 4.04 | 3.81 |

| N | 249 | 234 | 209 | 191 | 183 | 155 | 92 | 86 |

| Negative attributions | ||||||||

| M | 79.65 | 79.93 | 80.51 | 78.47 | 78.83 | 82.51 | 80.23 | 81.14 |

| SD | 19.38 | 21.48 | 23.15 | 24.81 | 23.49 | 25.73 | 25.96 | 24.63 |

| N | 251 | 228 | 210 | 193 | 184 | 155 | 173 | 175 |

| Acute stress | ||||||||

| M | 4.56 | 3.72 | 3.27 | 2.96 | 2.61 | 2.94 | — | — |

| SD | 3.48 | 3.26 | 2.80 | 2.22 | 2.59 | 2.60 | — | — |

| N | 251 | 230 | 211 | 191 | 197 | 162 | — | — |

| Self-esteem | ||||||||

| M | 34.53 | 35.10 | 35.30 | 35.94 | 36.29 | 35.41 | 35.27 | 36.26 |

| SD | 4.82 | 4.67 | 4.52 | 3.98 | 3.91 | 4.80 | 5.70 | 4.52 |

| N | 251 | 229 | 210 | 191 | 182 | 155 | 146 | 139 |

Notes: 37 couples dissolved their relationships by the final assessment. Acute stress was not assessed at Time 7 or 8. Verbal aggression was not assessed in the first sample at Time 7 or 8.

Table 3.

Wives’ Satisfaction and Risk Across Eight Waves of Measurement: Descriptive Statistics (N = 251)

| Time |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Marital satisfaction | ||||||||

| M | 97.66 | 93.88 | 94.27 | 94.58 | 94.00 | 92.71 | 91.15 | 93.19 |

| SD | 9.81 | 13.40 | 14.00 | 12.81 | 13.79 | 15.88 | 16.38 | 14.91 |

| N | 251 | 240 | 234 | 219 | 208 | 177 | 189 | 190 |

| Relationship problems | ||||||||

| M | 47.30 | 48.13 | 49.01 | 46.66 | 46.38 | 49.88 | 48.49 | 47.69 |

| SD | 22.18 | 22.03 | 24.12 | 21.67 | 22.73 | 24.59 | 23.56 | 23.31 |

| N | 247 | 238 | 234 | 219 | 208 | 177 | 190 | 189 |

| Verbal aggression | ||||||||

| M | 6.53 | 5.52 | 6.17 | 5.59 | 5.32 | 5.15 | 4.68 | 4.47 |

| SD | 4.59 | 4.38 | 4.32 | 4.23 | 4.18 | 4.06 | 4.16 | 4.10 |

| N | 250 | 236 | 211 | 197 | 191 | 158 | 94 | 86 |

| Negative attributions | ||||||||

| M | 77.17 | 77.03 | 79.49 | 77.44 | 79.48 | 79.72 | 81.02 | 81.74 |

| SD | 21.26 | 22.62 | 22.55 | 23.03 | 25.07 | 23.93 | 25.39 | 25.42 |

| N | 251 | 230 | 211 | 198 | 192 | 159 | 172 | 178 |

| Acute stress | ||||||||

| M | 5.31 | 4.66 | 4.33 | 3.89 | 3.51 | 3.73 | — | — |

| SD | 4.09 | 3.55 | 3.56 | 3.52 | 3.31 | 2.73 | — | — |

| N | 251 | 231 | 211 | 197 | 203 | 166 | — | — |

| Self-esteem | ||||||||

| M | 33.46 | 33.96 | 34.00 | 35.00 | 34.86 | 34.84 | 35.75 | 35.59 |

| SD | 5.37 | 5.59 | 5.46 | 5.25 | 5.10 | 4.81 | 4.99 | 4.88 |

| N | 251 | 231 | 211 | 198 | 189 | 159 | 149 | 140 |

Notes: 37 couples dissolved their relationships by the final assessment. Acute stress was not assessed at Time 7 or 8. Verbal aggression was not assessed in the first sample at Time 7 or 8.

Table 4.

Correlations at Time 1 Among Husbands and Wives (N = 251 couples)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husbands | |||||

| 1. Relationship satisfaction | — | ||||

| 2. Relationship problems | −0.62** | — | |||

| 3. Verbal aggression | −0.29** | 0.33** | — | ||

| 4. Negative attributions | −0.37** | 0.44** | 0.23** | — | |

| 5. Stressful life events | −0.19** | 0.37** | 0.19** | 0.21** | — |

| 6. Self-esteem | 0.26** | −0.27** | −0.22** | −0.14* | −0.23** |

| Wives | |||||

| 1. Relationship satisfaction | — | ||||

| 2. Relationship problems | −0.75** | — | |||

| 3. Verbal aggression | −0.34** | 0.40** | — | ||

| 4. Negative attributions | −0.42** | 0.40** | 0.19** | — | |

| 5. Stressful life events | −0.27** | 0.29** | 0.23** | 0.11 | — |

| 6. Self-esteem | 0.27** | −0.30** | −0.24** | −0.05 | −0.23** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Results

Identifying Different Satisfaction Trajectories

Analytic Plan

We used semiparametric group-based mixed modeling (Nagin, 1999) to identify distinct marital satisfaction trajectories over the newlywed years. As with traditional longitudinal methods, this approach models the relationship between time and outcome with a polynomial function, including linear and quadratic terms. Unlike hierarchical and growth-curve modeling, which assume a continuous distribution of trajectories within the population and describe how growth varies continuously, this group-based approach assumes that the population consists of a number of groups with different trajectories and seeks to identify them (Nagin, 1999). As it is unlikely that the population falls into truly distinct groups, the patterns should be viewed as the best approximation of generally distinct experiences (Kamp Dush et al., 2008).

The optimal number of groups, the shape of the trajectory of each group, and the proportion of the sample belonging to each group were derived from the data, not from a priori predictions. We determined the number of groups that best fit the data by evaluating models with more groups and evaluating fit using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), with greater (less negative) values indicating better fit. The BIC values are greater as the sample size increases. It is important to note that the BIC favors models with fewer groups. We established a priori that we would choose the number of groups at which the BIC value was the greatest, provided that the smallest group constituted at least 10% of the sample (approximately 25–26 individuals). We set this standard at twice that of previous samples (i.e., 13 individuals; Lavner & Bradbury, 2010) in order to reduce measurement error and to have sufficient group sizes to be able to conduct growth curve analyses comparing the risk factors over time between groups. Parameters defining the shape of the trajectory were left free to vary across groups, and these coefficients were then used to calculate each individual’s probability of group membership (posterior probability). Individuals were assigned to the trajectory group with which their posterior probability was greatest (Nagin, 1999). Once an individual was categorized as belonging to a certain trajectory group, he or she was assumed to have a similar pattern to all other individuals in that group. Individuals in a trajectory group might have trajectories that do not exactly match the overall group trajectory, however, even if they followed approximately the same developmental course (Nagin & Tremblay, 2005).

We estimated models using SAS Proc Traj (Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 2001). This procedure accommodated missing data; missing data were assumed to be missing at random, and we thus estimated trajectories using all available SMD observations. We separately estimated trajectories for husbands and wives. We estimated models with intercept, linear, and quadratic coefficients, which we removed when analyses indicated they were not significant for particular groups.

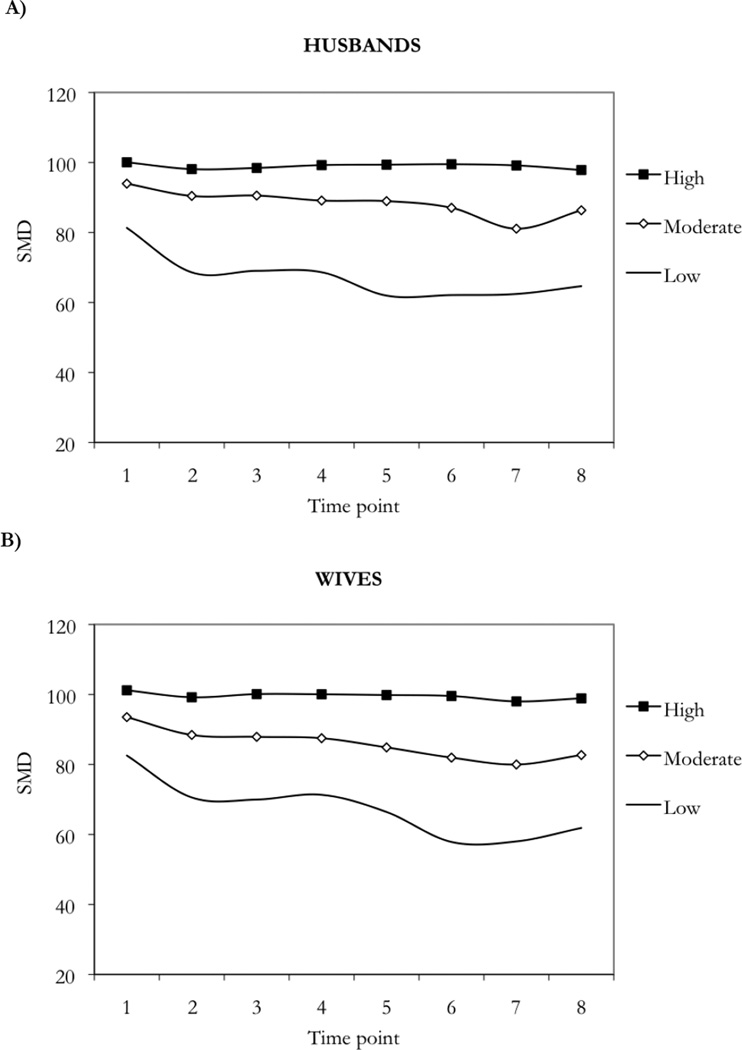

Husbands’ Satisfaction Trajectory Groups

We began by estimating models with one trajectory group to identify the common trajectory for husbands. As expected, the graph showed a significant linear decline over the 4 years. We then calculated BIC values for two groups to determine whether a multitrajectory approach was justified by providing a better fit to the data. The BIC values increased from one-group (BIC = −6,808.41) to two-group (BIC = −6,401.21) models, which indicates that a single trajectory did not provide the best fit to the data. We increased group number until best fit was achieved. The BIC values continue to increase for the three-group (BIC = −6,339.75) and four-group (−6,284.32) models, but the smallest group fell below the 10% threshold for the four-group model at 6.3%. Accordingly, we adopted the three-group model.

Table 5 shows the parameter estimates, and Figure 1A shows the observed trajectories. The three groups are consistent with the initial differences model. The largest group of husbands (“High Satisfaction”; 58%) had significant intercepts (intercept = 98.83), but slopes that did not differ significantly from zero, indicating that their satisfaction remained stable over time, at a high level. Significant declines were isolated to the other two groups. There was a moderately-sized group of husbands (29%) that began with moderately high initial satisfaction (intercept = 94.19) before experiencing a small but significant linear decline in satisfaction; this trajectory arguably represents what has been characterized as the common marital trajectory (Anderson et al., 2010). Lastly, there was a group of husbands (13%) who began with relatively low levels of initial satisfaction (intercept = 86.24) and then experienced a substantial decline in satisfaction characterized by significant linear and quadratic terms, indicating that their declines in satisfaction flattened out over time. An omnibus F-test indicated that the three groups differed in their initial satisfaction, F(2, 247) = 85.58, p < .001, and follow-up post-hoc comparisons indicated that each of the groups differed significantly from the others (all p < .001). Rates of marital dissolution over the four years also differed significantly among the trajectory groups, χ2(2, N = 251) = 10.49, p < .01, ranging from 12% in the high satisfaction group and 13% in the moderate satisfaction group to 33% in the low satisfaction group.

Table 5.

Satisfaction Trajectory Parameter Estimates (N = 251 couples)

| Parameter Estimates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | % | Intercept | Linear | Quadratic |

| Husbands (N = 251) | |||||

| Low | 33 | 13 | 86.24 | −1.31 | 0.02 |

| Medium | 72 | 29 | 94.19 | −0.20 | |

| High | 146 | 58 | 98.83 | ||

| Wives (N = 251) | |||||

| Low | 26 | 10 | 86.58 | −1.05 | |

| Medium | 52 | 21 | 93.66 | −0.27 | |

| High | 173 | 69 | 100.88 | ||

Note: All parameter estimates significant at p < .001.

Figure 1.

Observed marital satisfaction trajectories

Wives’ Satisfaction Trajectory Groups

We repeated the same procedures for wives, beginning with a one-group model. As with the husbands, the wives’ common trajectory showed a significant linear decline over the first 4 years. The BIC values increased from one-group (BIC = −6,918.36) to two-group (BIC = −6,601.84) models, indicating that a single trajectory did not provide the best fit to the data. Accordingly, we continued increasing group number until best fit was achieved. The BIC values continued to increase for the three-group model (BIC = −6,531.97), but decreased for the four-group model (BIC = −6540.26). The smallest group in the four-group model also fell significantly below the 10% cutoff at less than 1%. Accordingly, as with the husbands, the three-group model provided the best fit to the data.

Table 5 shows the parameter estimates, and Figure 1B shows the observed trajectories. The three groups yielded by the model were very similar, though not identical, to the husbands’ groups3. Again, the largest group of wives (69%) had significant intercepts (intercept = 100.88), but slopes that did not differ significantly from zero, indicating that their satisfaction remained stable over time, at a high level. The second-largest group of wives (21%) consisted of individuals who began with a moderately high initial level of satisfaction (intercept = 93.66) but then experienced small but significant linear declines over time. The third group of wives (10%) began with low levels of satisfaction (intercept = 86.58) and then experienced large linear declines in satisfaction. As with the husbands, an omnibus F-test indicated that the groups differed significantly in their initial satisfaction overall, F(2, 248) = 73.83, p < .001, and follow-up post-hoc comparisons indicated that each of the groups differed significantly from the others (all p < .001). Rates of dissolution also differed significantly among the trajectory groups, χ2(2, N = 251) = 22.78, p < .001, and ranged from 11% in the high satisfaction group and 12% in the moderate satisfaction group to 46% in the low satisfaction group.

Overall, although the average marital trajectory was one of declining satisfaction, the majority of spouses actually exhibited stable satisfaction over the newlywed years. Changes in satisfaction were isolated among the subset of spouses who started with lower levels of satisfaction, with the greatest declines occurring among those spouses who started with the lowest satisfaction4.

Understanding Initial Risk and Changes in Risk over Time

Analytic Plan

The second aim of the study was to examine whether the groups differed in initial risk and in changes in risk over time. We did so using growth curve analytic techniques and the HLM 7.0 computer program (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2010). Growth curve analytic techniques allow for a two-level process in data analysis. Level 1 allows for the estimation of within-subject trajectories of change (growth curve) for a variable, described by two parameters: an intercept (initial level of the variable) and a slope (rate of change over time). Level 2 allows for the examination of between-subjects differences in these parameters using individual-level predictors.

We analyzed husbands’ and wives’ data simultaneously within the same equations (as opposed to nesting spouses within couples; Atkins, 2005). Time was estimated as number of months since the couple’s wedding date and was uncentered so the intercept terms (Bw00 and Bh00) can be interpreted as the initial value six months into marriage. We used the following equations to test for differences in the intercept and linear slope of each risk variable by trajectory group membership:

These equations include separate intercepts and slopes for men and women, and sex-specific variance components at Level 2. Sex-specific trajectory group membership was included at Level 2 as a predictor of intercepts and slopes (e.g., husbands’ groups predicted their own intercepts and slopes), and was coded such that the reference group was the Moderate Satisfaction group (coded as 0), the Low Satisfaction group was −1, and the High Satisfaction group was 1.

We ran five separate models in which each risk variable (relationship problems, verbal aggression, negative attributions, acute stress, self-esteem) served as the outcome measure. Results are shown in Table 6; coefficients represent values for those individuals who were in the Moderate Satisfaction groups.

Table 6.

Summary of Multilevel Models Comparing Trajectories of Risk By Husbands’ and Wives’ Satisfaction Trajectory Groups (N = 251 couples)

| Risk Factor | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient x Group (SE) |

t-ratio | Effect size r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepts | ||||

| Husbands | ||||

| Relationship problems | 59.15 (1.49) | −19.06 (1.65) | −11.55*** | 0.59 |

| Verbal aggression | 5.50 (0.26) | −1.31 (0.30) | −4.41*** | 0.27 |

| Negative attributions | 82.93 (1.27) | −8.82 (1.49) | −5.89*** | 0.35 |

| Acute stress | 4.61 (0.23) | −0.87 (0.27) | −3.18** | 0.20 |

| Self-esteem | 34.28 (0.32) | 1.31 (0.38) | 3.47*** | 0.21 |

| Wives | ||||

| Relationship problems | 58.13 (2.12) | −18.58 (2.34) | −7.93*** | 0.45 |

| Verbal aggression | 7.37 (0.33) | −1.71 (0.36) | −4.75*** | 0.29 |

| Negative attributions | 83.52 (1.34) | −12.03 (1.53) | −7.89*** | 0.45 |

| Acute stress | 5.95 (0.33) | −1.49 (0.35) | −4.20*** | 0.26 |

| Self-esteem | 31.99 (0.46) | 2.80 (0.51) | 5.47*** | 0.33 |

| Slopes | ||||

| Husbands | ||||

| Relationship problems | 0.92 (0.29)** | −1.01 (0.31) | −3.24** | 0.20 |

| Verbal aggression | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.13 (0.07) | −1.97+ | 0.12 |

| Negative attributions | 1.06 (0.27)*** | −1.37 (0.33) | −4.20*** | 0.26 |

| Acute stress | −0.40 (0.06)*** | 0.14 (0.06) | 2.21* | 0.14 |

| Self-esteem | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.21 (0.08) | 2.81** | 0.18 |

| Wives | ||||

| Relationship problems | 1.04 (0.47)* | −0.92 (0.52) | −1.78+ | 0.11 |

| Verbal aggression | −0.17 (0.06)** | −0.08 (0.07) | −1.26 | 0.08 |

| Negative attributions | 1.08 (0.34)** | −0.52 (0.38) | −1.36 | 0.09 |

| Acute stress | −0.41 (0.08)*** | 0.13 (0.08) | 1.61 | 0.10 |

| Self-esteem | 0.29 (0.07)*** | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.09 | 0.01 |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Notes: df = 249 in each model. All intercepts were significant p < .001 because the lowest possible score on each measure was higher than zero, so these statistics are not reported. For the slopes, a 1-unit change in time represents 6 months of marriage. Trajectory group was coded -1 for Low, 0 for Moderate, and 1 for High, so Column 1 represents values for the Moderate Satisfaction group. The t-ratio is for the interaction term, which tests whether the groups differ significantly from one another. Effect size r = sqrt [t2/(t2 + df)].

Initial differences in risk by trajectory group

Consistent with the initial differences model, there were significant differences in intercepts by trajectory group for every risk factor (all p < .01; see Table 6). Effect size r ranged from 0.20 to 0.59 for husbands (median = .27) and 0.26 to 0.45 for wives (median = 0.33), suggesting these differences were moderate-to-large in size (Cohen, 1988). Replicating previous findings (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010), members within a group exhibited relative initial strengths or deficits across all domains of functioning: whereas relatively high initial levels of relationship problems, verbal aggression, negative relationship attributions, and acute stress, and relatively low initial levels of self-esteem characterized the most distressed groups, the opposite pattern was observed for the stable, high satisfaction groups. The moderate satisfaction groups fell between the other two groups.

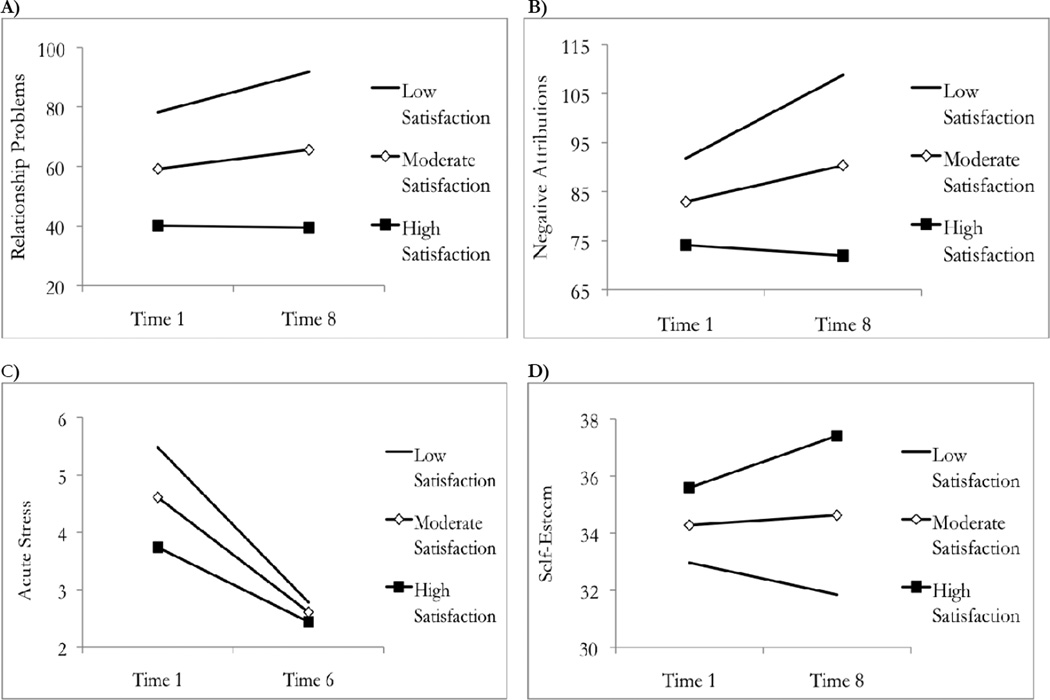

Changes in risk by trajectory group: Results for husbands

We then turned to understanding change over time to determine whether differences in the pattern of risk over time also distinguished among trajectory groups. For the husbands, changes in four of the five variables (relationship problems, negative attributions, acute stress, and self-esteem) were moderated by trajectory group membership (Table 6), indicating that the pattern of change differed by trajectory group. The fifth variable (verbal aggression) differed marginally by trajectory group over time. Effect size r estimates ranged from 0.12 to 0.26 (median = 0.18), indicating that these effects were small in magnitude.

The specific patterns of difference for the four variables moderated by trajectory group were somewhat varied (see Figure 2). Consistent with the incremental change model, relationship problems and negative attributions increased for spouses in the low satisfaction group at a greater rate than husbands in the moderate satisfaction group, whereas they remained stable for husbands in the high satisfaction group (confirmed through post-hoc analyses). In contrast, acute stress declined for all husbands and did so at faster rates for husbands in the low satisfaction group. Self-esteem increased for husbands in the high satisfaction group, but remained stable in the moderate and low satisfaction groups (confirmed through post-hoc analyses).

Figure 2.

Husbands’ relationship problems, negative relationship attributions, acute stress, and self-esteem differed initially and over time between trajectory groups

Changes in risk factors across trajectory groups: Results for wives

Among wives, trajectory group membership did not significantly moderate the pattern of change over time for any of the risk variables (Table 6), although relationship problems differed marginally between trajectory groups (p < .10). Together, these findings indicate that wives’ groups tended to change over time at similar rates, regardless of their satisfaction trajectories. Effect size r estimates ranged from 0.01 to 0.11 (median = 0.09), consistent with the lack of significant group effects (Table 6). Examining the specific direction of these changes, all wives exhibited more relationship problems and more negative attributions. They also exhibited improvements in their verbal aggression, acute stress, and self-esteem, however, regardless of their trajectory group.

Discussion

We used eight assessments of marital satisfaction to examine whether gradual declines in satisfaction best characterized newlyweds’ marital trajectories over the first several years of marriage. High intercepts and negative linear slopes did characterize the average satisfaction trajectories for husbands and for wives, but the majority of spouses – 58% of husbands and 69% of wives – exhibited high, stable satisfaction trajectories over the first four years of marriage. Consistent with predictions and prior work (Kamp Dush et al., 2008; Lavner & Bradbury, 2010), declines were isolated to partners who began their marriages with lower levels of satisfaction, with the most severe declines limited to a subset of spouses who began with the lowest initial levels of satisfaction. As predicted, this combination of low initial levels and rapidly declining satisfaction put these partners at increased risk for poor marital outcomes: over the first four years, spouses in the low satisfaction groups had rates of marital dissolution that were three to four times higher than spouses in the moderate and high satisfaction groups. Moderate and high satisfaction groups did not differ in their divorce rates, consistent with the idea that factors other than satisfaction underlie dissolution in low-distress couples (Amato & Hohmann-Marriott, 2007; Lavner & Bradbury, 2012).

More importantly, we sought to determine what distinguished spouses who experienced these different satisfaction trajectories. We tested an initial differences model, in which initial differences in multiple domains were expected to distinguish between different satisfaction groups, against an incremental change model, in which changes over time in multiple domains were expected to account for differences between different satisfaction groups. Consistent with an initial differences model, moderate-to-large intercept differences were found between trajectory groups in each of the domains examined here, including relationship problems, verbal aggression, negative relationship attributions, acute stress, and self-esteem. Spouses in different trajectory groups exhibited relative strengths or deficits across multiple domains, with spouses with the lowest satisfaction trajectory exhibiting relatively high initial levels of relationship problems, verbal aggression, relationship attributions, and acute stress, and relatively low levels of self-esteem. The reverse was true for spouses with the most satisfied marital trajectories. These findings document consistent initial differences across multiple domains of relationship, individual, and external functioning among spouses who go on to experience different satisfaction trajectories.

Limited evidence was found to support an incremental change model in which differences in patterns of change in these predictor variables distinguished among trajectory groups. Husbands with different satisfaction trajectories could be distinguished on the basis of their relationship problems and relationship attributions over time, though the magnitude of these effects was small. Differences between husbands’ outcome groups were also found for acute stress and for self-esteem, but not in expected directions (e.g., stress uniformly decreased, and more so in the less satisfied groups). For wives, changes in risk over time did not significantly distinguish partners with different satisfaction trajectories, and the general patterns of some changes were inconsistent with the observed trajectories (e.g., self-esteem, acute stress, and verbal aggression improved, even among increasingly dissatisfied wives). On the whole, our longitudinal analyses lend specificity to the change processes that matter, while suggesting that overall there were relatively few differences in patterns of change over time between partners who experienced markedly different satisfaction trajectories.

Before discussing the implications of these results, we first outline several caveats. First, as with much of the research examining newlywed marriage, the sample as a whole was disproportionately Caucasian, middle-class, and well-educated, suggesting that they were relatively low-risk (cf. Karney et al., 1995). As a result, the relative percentages of spouses with high, moderate, and low satisfaction trajectories is likely to be less positive in a higher-risk sample. We eagerly await replication with more diverse samples to test this idea and move toward a better population estimate of different trajectory groups and their base rates. Nonetheless, the limited variability in the sample likely served to minimize between-person differences, suggesting that the differences we found would probably be larger in a more diverse sample. Second, with regard to the semiparametric modeling approach adopted here, the number of trajectory groups in a sample is not immutable (Nagin & Tremblay, 2005). Sample sizes and number of assessments are likely to affect the number of groups and the shape of each group’s trajectory. Third, because each trajectory group summarizes the average trend of the individuals in it (Nagin & Tremblay, 2005), individual trajectories may not match the group trajectory, even if they follow approximately the same developmental course. In the same way that it is important to exercise caution regarding the representativeness of the derived subgroups to the population, so, too, is it necessary to recognize that these subgroups of satisfaction do not fully capture the complexity of the individual trajectories. The satisfaction groups were, however, consistently different in each of the other predictor domains studied here, increasing confidence that the trajectory groupings did indeed capture distinct marital experiences. Fourth, although the trajectory groups we identified did resemble groups that others have reported using different methods and samples (e.g., Belsky & Hsieh, 1998; Lavner & Bradbury, 2010), they were not exactly the same. These discrepancies were most likely due to different measures: Lavner and Bradbury’s (2010) analyses with a very similar sample yielded five trajectory groupings on the basis of spouses’ reports on the Marital Adjustment Test (MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959), a measure that has been criticized for combining assessments of global sentiments toward the marriage with ratings of specific problems areas (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987). As a result, it is possible that the number of trajectory groupings identified previously was inflated due to variability in specific relationship characteristics assessed by this instrument (e.g., disagreements about recreation, finances, or in-laws) rather than variability in change in global sentiments toward the marriage. Despite these differences, the substantive meaning of the findings did not differ across studies: both showed stability in satisfaction among the majority of couples, with declines and elevated divorce rates isolated to spouses who began with lower levels of satisfaction.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present findings advance understanding of why marriages eventually achieve different outcomes. The results reported here indicate initial differences are far-reaching and do more to explain differences in partners’ subsequent satisfaction trajectories than do changes over time. Such consistent variability so early in marriage (the initial assessment occurred when couples had been married for less than 6 months) suggests that the individual differences in satisfaction and the other domains observed here likely arise well before the start of the marriage. This variability could be reflected in couples’ courtship patterns (e.g., Surra, 1985), suggesting that the newlywed period may not truly be “the beginning” of a unique stage of relationship development but rather a continuation of processes and patterns of interacting that have already been established through years of dating and the engagement5. Differences in these patterns might stem from characteristics of the partners themselves, and specifically the extent to which each possesses more or less attractive traits (e.g., Buss & Barnes, 1986): given that some couples are composed of riskier individuals than others, it is perhaps not surprising that between-couple differences would exist even very early on. Thus, greater attention to premarital factors – and theoretical linkages with these earlier stages of relationship development – may help us understand the roots of this initial variability.

In contrast, changes in risk over time did little to distinguish couples with different trajectories. These findings are surprising in light of leading theories of relationship functioning emphasizing the gradual accumulation of negative processes. Despite the prevalence of this view, however, there has been relatively little longitudinal data testing these key tenets: studies typically rely on data from the first assessment to predict longitudinal change in satisfaction, assuming that this information captures an unfolding process (e.g., increasingly negative interactions) rather than acknowledging that it actually captures initial differences (e.g., Karney & Bradbury, 1997). Even those studies that have examined risk longitudinally have tended to focus more on how fluctuations in one’s own risk affects one’s satisfaction (e.g., decreased satisfaction under times of increased stress; Karney et al., 2005) than on whether changes in risk indeed map onto observed changes in satisfaction at a between-person level. Thus, by identifying distinct patterns of satisfaction over time and characterizing the changes in risk associated with these different satisfaction groupings, we were better able to empirically test which changes do indeed correspond with observed changes in satisfaction and which simply mark risk in these spouses.

In conclusion, the early years of marriage are a time of continued happiness for many newlyweds, and declining satisfaction is isolating among a minority who began with comparatively low satisfaction. These different marital trajectories appear to be due more to stable initial differences in a variety of domains, ranging from verbal aggression to acute stress, than to changes in those domains over time. Future research and theory will benefit from doing more to acknowledge and examine this initial variability, rather than focusing on explaining changes which in fact do not occur for the majority of couples.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation to Justin A. Lavner, and by a Research Development Award from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Florida, Institute of Mental Health Grant MH59712, and an award from the Fetzer Institute to Benjamin R. Karney.

Footnotes

We have published other articles using these datasets (e.g., McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008), but this is the first to (1) examine different patterns of marital satisfaction over time and (2) test whether initial differences versus changing processes distinguish different satisfaction trajectories.

The one exception to the incremental change model might be self-esteem, as intrapersonal variables are typically thought of as being more stable (e.g., Kelly & Conley, 1987).

Cross-tabulations of husbands’ group membership and wives’ group membership indicated a high degree of overlap: spouses were in the same trajectory group in 70% of couples (n = 175). In 21% of couples (n = 53), wives were in a higher satisfaction group than their husbands and in 9% of couples (n = 23), husbands were in a higher satisfaction group than their wives. Lavner and Bradbury (2010) similarly showed that wives tended to have higher satisfaction group assignments than husbands.

To ensure that the satisfaction trajectory groupings did not simply reflect demographic differences, we explored demographic differences among the groups using one-way ANOVAs, finding no significant differences among husbands’ or wives’ groups for age, education, income, ethnicity, religion, premarital cohabitation, how long they knew each other before getting married, or whether they became parents during the course of the study (all p > .01). As such, the trajectory groupings in Figures 1A and 1B do not appear to be the result of demographic differences in group membership, consistent with Lavner and Bradbury (2010).

In exploratory analyses, we examined whether the period of time couples knew each other pre-marriage significantly predicted the intercept and slope for each of the five risk variables. The only significant pattern of results was that wives who had been together for longer periods of time experienced less steep declines in verbal aggression over time (p < .05). Overall, however, given the broad pattern of non-significant results, these analyses indicated that couples’ risk trajectories appear to be independent of the length of time a given couple knew each other before marriage. This suggests that couples’ courtships are likely to be meaningful because of their quality, not because of their duration.

References

- Amato PR, Hohmann-Marriott B. A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:621–638. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JR, Van Ryzin MJ, Doherty WJ. Developmental trajectories of marital happiness in continuously married individuals: A group-based modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:587–596. doi: 10.1037/a0020928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC. Using multilevel models to analyze couple and family treatment data: Basic and advanced issues. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:98–110. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K. Patterns of marital change during the early childhood years: Parent personality, coparenting, and division-of-labor correlates. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. Attributions in marriage: Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:3–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. First marriage dissolution, divorce, and remarriage: United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Barnes M. Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:559–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. The assessment of marital quality: A reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49:797–809. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. Assessing attributions in marriage: The Relationship Attribution Measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:457–468. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss SK, O’Leary KD. Therapist ratings of frequency and severity of marital problems: Implications for research. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1981;7:515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Burgess RL. Social exchange in developing relationships: An overview. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, George LJ. The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:237–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp Dush CM, Taylor MG, Kroeger RA. Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations. 2008;57:211–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1075–1092. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Davila J, Cohan CL, Sullivan KT, Johnson MD, Bradbury TN. An empirical investigation of sampling strategies in marital research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:909–920. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Story LB, Bradbury TN. Marriages in context: Interactions between chronic and acute stress among newlyweds. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Conley JJ. Personality and compatibility: A prospective analysis of marital stability and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:27–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. The nature and predictors of the trajectory of change in marital quality over the first 4 years of marriage for first-married husbands and wives. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:494–510. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Bradbury TN. Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1171–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Bradbury TN. Why do even satisfied newlyweds eventually go on to divorce? Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0025966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Trajectories of change in physical aggression and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:236–247. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital adjustment prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, O’Mara EM, Karney BR. Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: “Don’t sweat the small stuff”.… but it is not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:631–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental trajectory groups: Facts or a useful statistical fiction? Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2005;43:873–904. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. The measurement of meaning. Urbana: University of Illinois Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, Bodenmann G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon RT. HLM7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;4:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA. Courtship types: Variations in interdependence between partners and social networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:357–375. [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, Amato PR. Marital happiness, marital duration, and the U-shaped curve: Evidence from a five-wave panel study. Social Forces. 2001;79:1313–1341. [Google Scholar]