Abstract

The enzyme 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase (4CL) is important in providing activated thioester substrates for phenylpropanoid natural product biosynthesis. We tested different hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa × Populus deltoides) tissues for the presence of 4CL isoforms by fast-protein liquid chromatography and detected a minimum of three 4CL isoforms. These isoforms shared similar hydroxycinnamic acid substrate-utilization profiles and were all inactive against sinapic acid, but instability of the native forms precluded extensive further analysis. 4CL cDNA clones were isolated and grouped into two major classes, the predicted amino acid sequences of which were 86% identical. Genomic Southern blots showed that the cDNA classes represent two poplar 4CL genes, and northern blots provided evidence for their differential expression. Recombinant enzymes corresponding to the two genes were expressed using a baculovirus system. The two recombinant proteins had substrate utilization profiles similar to each other and to the native poplar 4CL isoforms (4-coumaric acid > ferulic acid > caffeic acid; there was no conversion of sinapic acid), except that both had relatively high activity toward cinnamic acid. These results are discussed with respect to the role of 4CL in the partitioning of carbon in phenylpropanoid metabolism.

The enzyme 4CL (EC 6.2.1.12) catalyzes the formation of CoA thioesters of hydroxycinnamic acids by a two-step reaction mechanism that involves the hydrolysis of ATP (Gross and Zenk, 1974). These thioesters serve as substrates for a number of important reactions within plant phenylpropanoid metabolism. Depending on the species and tissue, formation of hydroxycinnamate esters and amides often involves CoA derivatives of 4-coumaric, caffeic, and/or ferulic acid, whereas flavonoid and stilbene biosynthesis requires cinnamoyl and/or 4-coumaroyl CoA esters as the substrates (Hahlbrock and Scheel, 1989; Dixon and Paiva, 1995; Holton and Cornish, 1995). The biosynthesis of salicylic acid from cinnamic acid may occur via oxidation of a cinnamoyl-CoA intermediate (Ryals et al., 1996), and within virtually all higher plants, generation of lignin monomers is presumed to require the conversion of 4-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and sinapic acid to the corresponding CoA esters in preparation for side-chain reduction (Whetten and Sederoff, 1995).

In keeping with this metabolic demand for different hydroxycinnamoyl CoA esters, 4CL preparations from plants are normally found to be able to use a number of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives as substrates (Gross and Zenk, 1974; Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1975, 1977; Grand et al., 1983; Lozoya et al., 1988; Voo et al., 1995; Lee and Douglas, 1996). It has also been proposed, however, that different isoforms of 4CL might possess different patterns of substrate preference, and characterization of 4CL isoforms from some plants supports this (Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1975; Ranjeva et al., 1976; Wallis and Rhodes, 1977; Grand et al., 1983). Such diversity could conceivably enable particular 4CL isoforms to efficiently supply an appropriate mixture of substrate(s) for specific metabolic sequences. However, in other plants in which they have been purified, no evidence for such catalytically distinct 4CL isoforms has emerged (Lozoya et al., 1988; Voo et al., 1995), and two divergent tobacco 4CL enzymes produced in recombinant form in Escherichia coli showed no differences in their substrate-utilization profiles (Lee and Douglas, 1996).

Poplar (Populus spp.) is a useful model for the study of phenylpropanoid metabolism and lignin biosynthesis in trees (Douglas, 1996). Several genes encoding enzymes of phenylpropanoid metabolism and lignin biosynthesis have been cloned from poplar species, including PAL (Subramaniam et al., 1993; Osakabe et al., 1995), C4H (Ge and Chiang, 1996; Kawai et al., 1996), bispecific caffeic acid-O-methyltransferase (COMT; Bugos et al., 1991; Dumas et al., 1992), and CAD (van Doorsselaere et al., 1995b). The monomer composition of angiosperm lignin, including that of poplar, varies according to cell type and stage of tissue development (Campbell and Sederoff, 1996). The lignin in poplar secondary xylem (wood) is composed primarily of guaiacyl units, presumed to be derived from coniferyl alcohol and feruloyl-CoA, and syringyl units, presumed to be derived from syringyl alcohol and sinapoyl-CoA. It has been possible to alter the composition of this lignin by antisense suppression of caffeate 3-O-methyltransferase and CAD activity (van Doorsselaere et al., 1995a; Baucher et al., 1996) in transgenic poplar trees.

4CL has been investigated in poplar at the enzyme level, but the role of 4CL in directing carbon flow in the biosynthesis of different lignin monomers is unclear. The cloning of poplar 4CL genes has not been reported except in the abstract form (Allina and Douglas, 1994). Grand et al. (1983) reported that three partially purified 4CL isoforms isolated from Populus euramericana demonstrated different substrate-preference patterns. Although each isoform could act on 4-coumaric acid and ferulic acid, form I preferentially used 5-hydroxyferulic acid and sinapic acid, whereas form III preferred caffeic acid. These 4CL isoforms were hypothesized to help determine lignin monomer composition in different tissues, based on their potential to supply the appropriate hydroxycinnamic acid intermediates (Grand et al., 1983). These results, however, appear to conflict with those of other studies (Kutsuki et al., 1982; Meng and Campbell, 1997) in which unfractionated 4CL preparations from P. euramericana and Populus tremuloides were able to use 4-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, and 5-hydroxyferulic acid, but not sinapic acid.

To clarify the properties of 4CL in poplar, and to evaluate the potential of poplar 4CL genes to alter lignin subunit composition by genetic-engineering approaches, we have undertaken a study of 4CL in the poplar hybrid clone H11, derived from a cross between Populus trichocarpa and Populus deltoides (Bradshaw and Stettler, 1993). Similar hybrids are of commercial interest on the west coast of North America, and form part of a three-generation pedigree (Bradshaw et al., 1994). Our results confirm that multiple 4CL isoforms are present in poplar tissues, and that 4CL is encoded by a gene family in poplar. However, we found no evidence for differences in the substrate-utilization profiles of the partially purified native 4CL isoforms or of two isoforms expressed in recombinant form, and we were unable to identify any isoform with detectable activity against sinapic acid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clonally propagated individuals of poplar hybrid (Populus trichocarpa Torr. & Gray × Populus deltoides Marsh) H11 were used for organ and tissue isolation. Harvested material was immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. Secondary xylem was isolated from 4- to 6-year-old trees grown in the field at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver). Trees were harvested in May 1995, debarked, and developing xylem was scraped off the stems using razor blades. Young leaves (0.5–2 cm in length) were harvested from H11 plants maintained in growth chambers at 23°C in a 16-h light/8-h dark regime. Old (fully expanded) leaves and green (nonwoody) stems were harvested from the same plants. The H11 cell cultures and elicitor treatments were as described previously (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992). Polygalacturonic acid lyase elicitor was added to suspension-cultured cells 5 d after subculturing.

cDNA Library Screening

Approximately 106 plaque-forming units from a λZAPII (Stratagene) H11 young-leaf cDNA library (Subramaniam et al., 1993) were screened using a probe generated from a 1.5-kb poplar 4CL cDNA previously isolated from this library (Douglas et al., 1992). Filters were washed at low stringency (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS, at 65°C) as described by Sambrook et al. (1989).

Sequence Analysis

Both strands of 4CL cDNA clones 4CL-2, 4CL-9, and 4CL-B2 were sequenced using the T7 Sequencing kit (Pharmacia) or by the University of British Columbia Nucleic Acid-Protein Service Unit using the PRISM Ready Reaction DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Predicted amino acid sequences, molecular weights, and pI values were analyzed using the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group software (Madison, WI).

Nucleic Acid Methods

Standard molecular biology techniques were used as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). Poplar genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves as described previously (Subramaniam et al., 1993), and total RNA was extracted using the method of Hughes and Galau (1988). High-stringency washes for Southern blots were at 0.2× SSC, 0.1% SDS, at 65°C; low-stringency washes were at 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS, at 65°C. For northern blots, 10 μg of RNA was separated on 1.2% agarose gels containing formaldehyde, rinsed with water for 45 min, and stained with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. The RNA was blotted overnight onto Hybond-N (Amersham), and blots were washed at 0.5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, at 65°C after hybridization. Parallel hybridization of the probes to Southern blots of 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 plasmids indicated that hybridization to the heterologous cDNA was at least 10-fold lower than to the homologous cDNA under these washing conditions. To demonstrate evenness of loading between lanes, the blots were stripped and rehybridized with a probe for a pea rRNA gene (Jorgensen et al., 1982). DNA fragments were radioactively labeled using the Random Primers DNA Labeling System (GIBCO-BRL).

Construction of Chimeric 4CL-216

PCR was used to create a chimeric, 4CL-2-like full-length cDNA clone. Two 4CL-specific primers, primer A (5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCTCTTTCATTCTCTGTTCCAGA-3′) and primer B (5′-AACTTGTTGTGCCACAC-3′), were used to amplify a predicted 670-bp PCR fragment from H11 genomic DNA. Amplified fragments were digested with SpeI and NotI and cloned into Bluescript KS (Stratagene). Any 4CL-9-like clones were eliminated by digestion with SacI, which cuts 4CL-9 in the amplified region. Ten PCR clones, similar to 4CL-2 on the basis of restriction digests, were fully sequenced in one direction. PCR fragment A16 was used to replace a NotI-SpeI restriction fragment at the 5′ end of 4CL-2 to create 4CL-216.

Expression of Recombinant 4CL in Baculovirus-Infected Insect Cells

4CL-9 and 4CL-216 cDNA inserts were isolated by digestion with PstI or NotI and XhoI, respectively. The XhoI site was made blunt by filling in with Klenow polymerase. Baculovirus vector pVL1392 (Webb and Summers, 1990) was digested with PstI or NotI and SmaI. The respective cDNA inserts were ligated with digested pVL1392 to create the plasmids pVL1392::4CL9 and pVL1392::4CL216. These plasmids (2 μg) were mixed with 0.25 μg of AcNPV viral DNA (BaculoGold, PharmIngen, San Diego, CA) and transfected into 2 × 106 Sf9 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD; accession no. CRL-1711). Recombinant baculovirus particles were plaque purified, and two of each recombinant virus were chosen for production of high-titer virus stocks. Viral titers were calculated either by plaque assays or by end-point dilution (Summers and Smith, 1987) and were tested for production and activity over time. A single virus stock expressing each recombinant protein was selected for further use.

Poplar Protein Extraction and Partial Purification of 4CL

The following buffers were used in various steps of partial 4CL purification from poplar extracts: A, 0.2 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 14 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 30% (v/v) glycerol; and B, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 14 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5% (v/v) glycerol. All steps were carried out at 4°C. Protein extraction was as described by Knobloch and Hahlbrock (1977) with some modifications. Poplar tissue was homogenized in liquid N2. The powder was mixed with buffer A and Dowex AG 1-X2 Resin (0.1 g of resin per g of tissue in 2 mL of buffer A; Bio-Rad), rotated for 20 min, filtered, and centrifuged to remove resin and debris. 4CL activity was precipitated from the supernatant with solid (NH4)2SO4 (40–80% saturation), dissolved in a minimal volume of buffer B, and the sample desalted by chromatography on a Sephadex G-50 column. The cell extract was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter and applied to a HR5/5 Mono-Q anion-exchange FPLC column (Pharmacia). Fractions were eluted using a nonlinear gradient from 0 to 0.5 m KCl in buffer B with a flow rate of 0.5 or 1 mL/min. The gradient was established using 0% 1 m KCl for 2 mL, 0 to 7% for 5 mL, 7% for 5 mL, 7 to 10% for 15 mL, 10% for 5 mL, 10 to 30% for 30 mL, and 30 to 50% for 5 mL. Fractions (1 mL) were collected, and glycerol was added immediately to 24% (v/v) and stored at −20°C.

Insect Cell Extracts and Purification of Recombinant 4CL

Cultured insect cells (1 × 108) were infected at a multiplicity of infection of one and harvested approximately 48 h after infection. Cells were centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was washed twice with Dulbecco's PBS (without MgCl2 or CaCl2; Sigma-Aldrich) and resuspended in 4.2 mL of 200 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8. The cells were lysed using a 15-mL homogenizer (Wheaton Science Products, Millville, NJ), and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 min at 4°C. Glycerol (30%, v/v) and 14 mm 2-mercaptoethanol were added to the supernatant and samples were stored at −20°C. Infected cells used for subsequent purification of 4CL enzyme activity by FPLC were prepared as described above, but were resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8. Protein content of cell extracts was quantified with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit using BSA as a standard. To purify recombinant 4CL, insect cell extracts were subjected to FPLC under conditions identical to those used with poplar extracts.

4CL Enzyme Assays

4CL activity was measured at room temperature using a spectrophotometric assay (Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1977) to measure formation of CoA esters of various phenolic acids, as previously described (Lee and Douglas, 1996). Phenolic acid substrates were used at concentrations of 0.2 mm, except for determination of Km values, in which case they were used in concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.6 mm. In some experiments the formation of the appropriate CoA esters in reaction mixtures was examined by HPLC chromatography of reaction products (D. Lee, S. Wang, J. Grandmaison, C. Douglas, and B. Ellis, unpublished data).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblots

Protein samples were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels (Laemmli, 1970) and either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or blotted onto nylon membranes (PVDF, Schleicher & Schuell). Blots were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat powdered milk and reacted with antisera raised against parsley 4CL (Ragg et al., 1981) at a 1:5000 dilution, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase at a 1:500 dilution (GIBCO-BRL). Alkaline phosphatase activity was visualized using nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate as the substrates (GIBCO-BRL).

RESULTS

Separation of 4CL Isoforms

Three different poplar tissue types were examined for their 4CL activity profiles: developing xylem, young leaves, and cell-suspension cultures treated with an Erwinia carotovora polygalacturonic acid-lyase preparation (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992). The highest 4CL-specific activity was detected in crude extracts of the developing xylem (Table I), consistent with the strong commitment to lignification in this tissue. Concentration of the extracted proteins by precipitation between 40 and 80% ammonium sulfate saturation was followed by fast-protein liquid anion-exchange chromatography, which resolved different 4CL isoforms. However, 4CL activity in all tissue extracts was unstable, and whereas inclusion of 24% glycerol in the buffers allowed better recovery, most of the activity (70–99%) was lost after completion of these two fractionation steps.

Table I.

Partial purification of 4CL isoforms from poplar tissues

| Tissue (Starting Material) | Purification Step | Protein | Total Activity | Specific Activity | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | mg | pkat | pkat/mg | -fold | |

| Xylem (40) | Crude extract | 192 | 50144 | 261 | 1.0 |

| (NH4)2SO4 ppt. | 12 | 5764 | 480 | 1.8 | |

| Mono-Q peak Ia | 0.04 | 132 | 3300 | 12.6 | |

| Mono-Q peak II | 0.04 | 220 | 5500 | 21 | |

| Elicited cell culture (60) | Crude extract | 61.6 | 2152 | 35 | 1.0 |

| (NH4)2SO4 ppt. | 14 | 356 | 25 | 0.7 | |

| Mono-Q peak I | 0.12 | 269 | 2241 | 64 | |

| Young leaves (50) | Crude extract | 4 | 80 | 2 | 1.0 |

| (NH4)2SO4 ppt. | 2 | 66 | 33 | 1.7 | |

| Mono-Q peak I | 0.08 | 27 | 338 | 16.9 | |

| Mono-Q peak II | 0.12 | 27 | 225 | 11.3 |

Peaks I and II refer to activity in Mono-Q column peak fractions (Fig. 1); Mono-Q data are from pooled fractions from each peak.

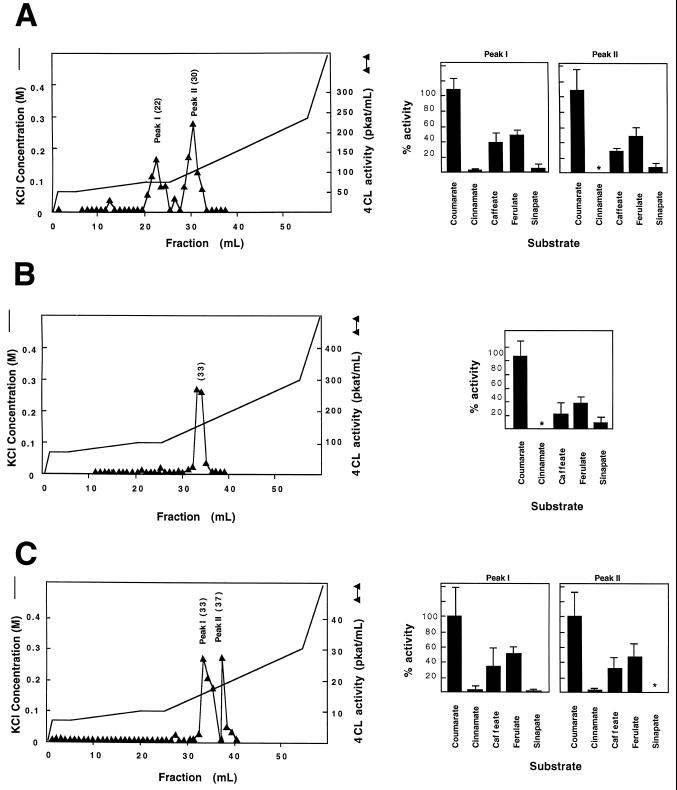

The FPLC activity profiles obtained for each tissue source were different, and together provided evidence for at least three physically distinct 4CL forms in this poplar genotype (Fig. 1). Using 4-coumaric acid as a substrate, two 4CL activity peaks were resolved in both the xylem and in the young leaf extracts, whereas the elicited cell cultures yielded a single peak. The activity in the young leaves was relatively low, but still reproducible. The observed elution positions for all peaks were consistent between runs to within 1 to 2 mL. Based on their chromatographic behavior, therefore, peak I in the xylem extracts and peak II in the young leaf extracts appear to represent two distinct isoforms of poplar 4CL. The elution times of peak II in the xylem extract, peak I in the young leaf extract, and the single peak observed in the elicited culture were distinct from the two identified above and, thus, appear to represent at least one additional 4CL isoform. Alternatively, these three peaks of activity could represent as many as three additional isoforms that elute at similar positions (fractions 30–33).

Figure 1.

Native poplar H11 4CL isoforms. Proteins from developing secondary xylem (A), elicitor-treated cell culture (B), and young leaves (C) of clone H11 were extracted and separated by FPLC on an anion-exchange column. 4CL activity using 4-coumarate as a substrate was assayed in 1-mL fractions eluted using the nonlinear KCl gradient indicated. The fractions from each peak with the highest activities are noted in brackets. The substrate specificity of each isoform was tested using a pool of the fractions with highest activity (graphs on right), using hydroxycinnamate substrates at 0.2 mm. Error bars represent the sd of the average of three replicates. Asterisks indicate the absence of detectable activity. The average enzyme activities using 4-coumarate as a substrate, which were taken as 100%, are as follows: A, xylem peak I, 95.8 pkat/mL; xylem peak II, 153.0 pkat/mL; B, elicited cells, 166.0 pkat/mL; and C, young leaves peak I, 9.3 pkat/mL; young leaves peak II, 7.4 pkat/mL.

Unfortunately, our inability to stabilize the extracted activity precluded more extensive physical characterization of the native enzymes. We recovered insufficient fractionated enzyme activity to allow extensive kinetic analyses of the tissue-derived enzymes. Instead, the substrate-specificity profile of each of the 4CL activity peaks detected in the different tissue types was compared by assaying the highest-activity fractions with a range of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives at a fixed concentration. This comparison demonstrated that all of the chromatographically resolved peaks had similar catalytic preferences (Fig. 1). 4-Coumaric acid was always used most efficiently, followed by ferulic acid and caffeic acid. The trace of activity, apparently detected with cinnamic acid and sinapic acid as the substrates, was within the noise limits of the spectrophotometric assay and could not be confirmed by HPLC analysis of reaction products.

Cloning and Characterization of 4CL cDNAs

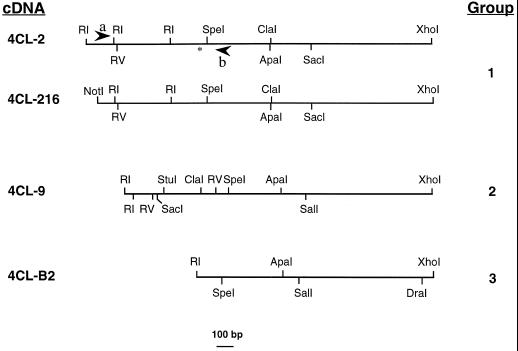

To study the properties of poplar 4CL enzymes in more depth, and to investigate the nature of the poplar 4CL gene family, we isolated 4CL cDNA clones from an H11 young leaf cDNA library (Subramaniam et al., 1993). Previous screening of the library with potato 4CL cDNA (Becker-André et al., 1991) as a probe identified a 1.5-kb poplar 4CL cDNA (4CL-B2; Douglas et al., 1992). Use of 4CL-B2 as a hybridization probe in further low-stringency screening of the cDNA library identified 16 additional putative 4CL clones. Restriction enzyme digests allowed all clones, including the original 4CL-B2, to be placed into three groups, as shown in Figure 2. Each group contained clones of different lengths; the longest clones within each group, 4CL-9, 4CL-2, and 4CL-B2, were 1950, 2200, and 1500 bp, respectively (Fig. 2). Group 3 clones appeared to be quite similar to those in group 2 except for the presence of a unique DraI site at the 3′ end. Southern-blot analysis (not shown) showed that all clones within groups 2 and 3 strongly cross-hybridized at high stringency, but that there was much less cross-hybridization between group-2/3 clones and group-1 clones under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Restriction maps of poplar 4CL cDNA clones. RI, EcoRI; RV, EcoRV. Arrowheads represent placement of 4CL-specific primers (a and b) used to amplify a 670-bp H11 genomic DNA fragment to replace the 5′ end of 4CL-2, which contained an erroneous stop codon. The asterisk represents the approximate position of that stop codon.

The three longest clones of each class (4CL-2, 4CL-9, and 4CL-B2) were fully sequenced. 4CL-2 and 4CL-9 contained in-frame putative Met start codons (in 4CL-2 this was preceded by an in-frame stop codon) and had the potential to encode complete 4CL proteins; 4CL-B2 was a partial clone and contained an open reading frame of 400 amino acids. The overall nucleotide identity between 4CL-9 and 4CL-B2 was 98%, but there was some divergence between 3′ untranslated regions and several gaps were required for sequence alignment. The identity between the predicted amino acid sequences of these two clones was 96%. With such a high degree of identity, it is possible that 4CL-9 and 4CL-B2 are allelic. 4CL-9 contained a single open reading frame with the potential to encode a protein of 548 amino acids. 4CL-2 contained two open reading frames, each having extensive similarity to known 4CL proteins. However, the open reading frames were interrupted by an in-frame stop codon at amino acid position 170 (660 bp), generated by a potential single-base-pair frame-shift mutation. We hypothesized that 4CL-2 either represented an mRNA transcribed from a nonfunctional pseudogene or that the frame shift was an artifact of the cloning process.

To determine if the stop codon in 4CL-2 was a cloning artifact, we used 4CL-specific primers (shown in Fig. 2) to PCR amplify the H11 genomic DNA flanking both sides of the region containing the 4CL-2 stop codon. The 10 4CL-2-like PCR products cloned and sequenced all showed a high degree of sequence similarity to 4CL-2 but not to 4CL-9, and none contained the frame-shift-generated stop codon found in 4CL-2. This suggests that the original 4CL-2 stop codon was an artifact of cloning. However, none of the 4CL-2-like clones was identical in nucleotide sequence to 4CL-2, possibly because of errors in PCR amplification. We chose PCR fragment A16 to replace the 5′ sequence of 4CL-2 because it was the most similar in sequence to the original 4CL-2 clone. This replacement resulted in a single Ala-to-Pro amino acid substitution at position 198 of the original 4CL-2 sequence, within a conserved region of 4CL proteins. All 4CL sequences known at the time contained a conserved Pro at this position. This new chimeric clone, 4CL-216, was used in all subsequent work as a representative of 4CL-2-like genes.

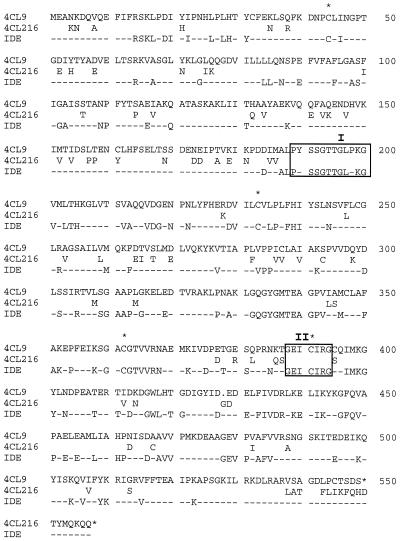

Clones 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 were 87% identical at the nucleic acid level and 86% identical at the amino acid level. Both clones showed significant similarity to 4CL genes from other plants, and were most similar to GM4CL14 from soybean (Uhlmann and Ebel, 1993) and Nt4CL19 from tobacco (Lee and Douglas, 1996) (data not shown). Figure 3 shows a comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences of the proteins encoded by clones 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 and the location of amino acid residues conserved in all 4CL gene sequences. The predicted amino acid sequences of 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 contain domains typical of predicted 4CL proteins, in particular a postulated AMP-binding site, catalytic domain, and conserved Cys residues.

Figure 3.

Amino acid sequence comparison of 4CL-9, 4CL-216, and other known 4CL sequences. The full predicted amino acid sequence of 4CL-9 is given; amino acids in 4CL-216 are shown only where they differ from 4CL-9. Amino acids identical in all known 4CL sequences, including those of 4CL-216 and 4CL-9, are shown (IDE). A gap introduced to maximize the alignment is indicated by a dot in the 4CL-9 sequence. Conserved regions I (AMP-binding site) and II (putative catalytic site) are boxed; conserved Cys residues and the putative stop codons are indicated by asterisks.

4CL Genomic Organization

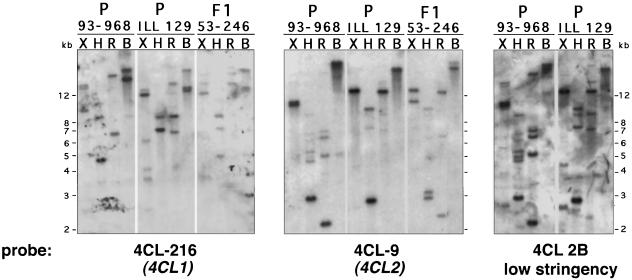

To assess the size of the potential 4CL gene family in poplar, and to examine the relationships between the genes from which clones 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 were derived, we performed Southern-blot analysis using genomic DNA from clones of parental and F1 hybrid poplar clones that are part of a three-generation pedigree (Bradshaw et al., 1994). This allowed us to follow the inheritance of 4CL-specific restriction fragments so that allelic DNA polymorphisms could be distinguished from duplicate genes.

The same blot containing restriction-digested DNA from these clones was hybridized sequentially to the 4CL-216, 4CL-9, and 4CL-B2 probes (Fig. 4). Except for EcoRV, none of these enzymes cut into either cDNA, but any of the enzymes could potentially cut within the 4CL genes. High-stringency hybridization to the 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 probes revealed that each probe hybridized strongly to a distinct set of restriction fragments in parental clones 93-968 and ILL129, and that the F1 hybrid individual 53-246 contained combinations of these fragments. This indicates that the two clones were derived from separate genes, each present in the parental genotypes. Additional, more weakly hybridizing fragments were also present. Some of these fragments could be attributed to cross-hybridization of the respective probes to fragments that strongly hybridized to the other probe, but others were distinct from these. These fragments were more easily seen after low-stringency hybridization to the 4CL-B2 probe (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Genomic Southern-blot analysis of 4CL genes in parental and hybrid poplar genotypes in a controlled cross. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from parental genotypes P. trichocarpa 93-968 and P. deltoides ILL129 and F1 progeny 53-246 was cut with the four enzymes indicated and a Southern blot was prepared. The blot was hybridized sequentially to the cDNA probes indicated. X, XbaI; H, HindIII; R, EcoRV; and B, BamHI. Migration of size markers (in kilobases) is shown.

The restriction fragments that hybridized strongly to 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 in the parental clones appeared to represent single genes, as judged by inheritance of the fragments in the F1 hybrid. Depending on the digest, one to three parental fragments hybridized strongly to each probe; where there were multiple predominant fragments, only one was inherited in clone 53-246, suggesting that they represent allelic restriction fragment-length polymorphisms. For example, of the XbaI fragment doublet in clone 93-968 that hybridized to 4CL-216 and a doublet of a different size that hybridized to 4CL-9, only one of the respective fragments was inherited in 53-246; of the two BamHI fragments in 93-968 that hybridized to 4CL-216, only one was detected in 53-246. In the case of EcoRV digests, the expected additional restriction fragments derived from cutting within the genes were not detected, possibly because of the small regions of overlap between such genomic fragments and the cDNA-derived probes.

These data indicate that cDNA clones 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 are derived from two single genes. To distinguish the cDNA clones from the genes they represent, the clones (and their encoded proteins) are referred to as 4CL-216 and 4CL-9, whereas the respective genes are designated 4CL1 and 4CL2. The presence of additional, weakly cross-hybridizing restriction fragments strongly suggests that there are additional divergent 4CL genes in the poplar genome not represented by either of these two cDNA clones.

Expression of 4CL Genes

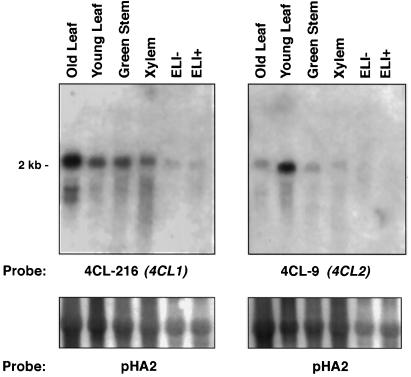

To examine the developmentally regulated and inducible expression patterns of the cloned poplar 4CL genes, duplicate northern blots were prepared using RNA isolated from various H11 tissues and from an H11 suspension-cell culture, in which phenylpropanoid gene expression is activated by elicitor treatment (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992). The blots were hybridized with 4CL-216 (4CL1) or 4CL-9 (4CL2) under conditions that allowed little cross-hybridization between the genes (not shown). Figure 5 shows that steady-state 4CL2 mRNA levels were highest in young leaves, with lower levels seen in old leaves, green stem, and developing secondary xylem. In comparison, the highest 4CL1 mRNA level was seen in old leaves, with lower levels in young leaves, green stem, and xylem. 4CL1 expression in green stem and xylem appeared to be stronger than 4CL2 expression in these tissues. Because there was some cross-hybridization between the probes, it is possible that some of the apparent low levels of 4CL2 expression in old leaves, green stem, and xylem is attributable to 4CL1 transcripts, and that some of the 4CL-216 hybridization to young-leaf RNA is attributable to cross-hybridization 4CL2 transcripts. In summary, it appears that both genes are expressed in the same tissues, but that 4CL2 is preferentially expressed in young leaves and 4CL1 is preferentially expressed in old leaves, green stem, and xylem. Unexpectedly, neither gene was expressed in response to elicitor treatment, although similar blots loaded with the same RNA samples and hybridized to poplar PAL and C4H probes showed that the expression of these genes was strongly stimulated by the elicitor treatment (N. Mah and C. Douglas, unpublished data).

Figure 5.

Northern-blot analysis of poplar 4CL mRNA levels. Total RNA (10 μg) from different tissues and organs was separated on duplicate formaldehyde agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and hybridized to either 4CL-216 or 4CL-9 cDNA probes. ELI+, Elicitor-treated tissue culture cells; ELI−, untreated control cells. The membranes were stripped and rehybridized with an rRNA probe (pHA2) to demonstrate evenness of loading.

Recombinant 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 Proteins

To study the properties of the proteins encoded by 4CL-216 and 4CL-9, we generated recombinant proteins using a baculovirus-expression system. In a typical experiment, 50-mL spinner flasks of Sf9 insect cells infected with 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 baculovirus constructs yielded 7.8 and 6.7 mg of total protein, respectively. The 4CL specific activities of the respective crude extracts toward 4-coumaric acid were 4.7 and 17.1 pkat/μg protein. Fast-protein liquid anion-exchange chromatography of the extracts yielded single peaks of 4CL activity toward 4-coumaric acid, and recombinant 4CL-9 activity reproducibly eluted earlier in the KCl gradient than recombinant 4CL-216 (data not shown). Approximately 18 and 45% of the original activity in Sf9 crude extracts was recovered in the most active fractions of 4CL-216 and 4CL-9. These pooled fractions had specific activities of 55.6 and 126 pkat/μg protein, respectively, corresponding to 117 and 408 μg of protein.

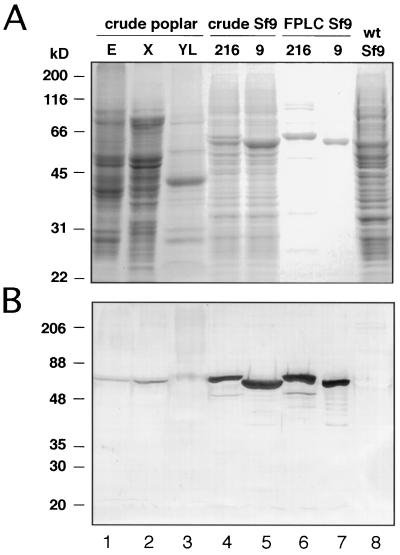

To verify the authenticity of the recombinant virus-produced proteins, and to assess the purity of FPLC-purified 4CL-216 and 4CL-9, the pooled peak FPLC fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE in parallel with crude Sf9 and poplar extracts, and immunoblots reacted with a parsley 4CL-specific antiserum (Ragg et al., 1981). Figure 6A shows that FPLC resulted in an efficient enrichment of the putative recombinant 4CL proteins in a single step (compare lanes 4 and 5 with lanes 6 and 7). A parallel immunoblot showed that these proteins strongly cross-reacted with the 4CL antiserum, and that they migrated with mobilities similar to those of 4CL proteins in poplar tissue extracts (Fig. 6B, lanes 1–3), with apparent molecular weights of approximately 60,000. No 4CL protein was detected in the Sf9 insect cells containing the wild-type baculovirus (Figs. 6, A and B, lane 8). It is interesting that recombinant 4CL-216 reproducibly migrated somewhat more slowly than 4CL-9, although the predicted size of the 4CL-216 protein was only nine amino acid residues (1235 D) larger than that of 4CL-9. The reasons for this are unknown.

Figure 6.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of recombinant 4CL proteins. SDS-PAGE gel (A) and an immunoblot of a parallel gel (B) reacted with antiserum specific to parsley 4CL (Ragg et al., 1981). Crude extracts (20 μg) of Sf9 cells infected with 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 baculovirus constructs, and 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 (1 μg each) FPLC-purified from infected Sf9 cells, were loaded as shown. wt Sf9, Wild-type (uninfected) Sf9 cells. Crude poplar extracts were derived from elicitor-treated cells (E), differentiating xylem (X), and young leaves (YL). Molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left.

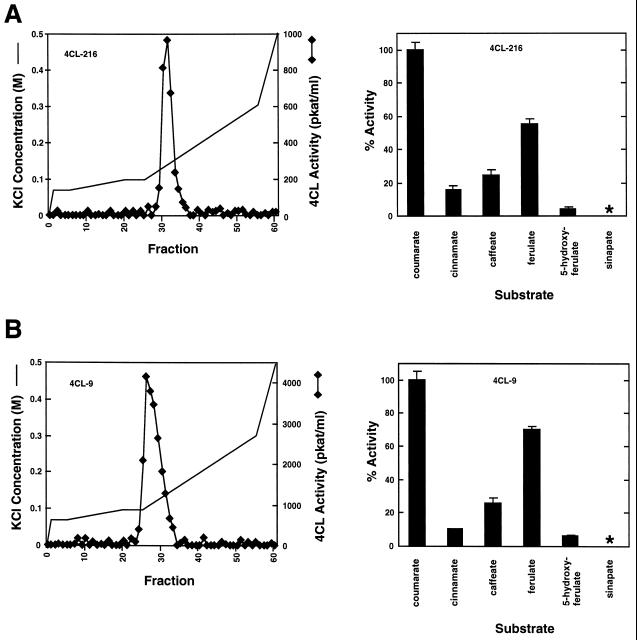

The FPLC-purified recombinant proteins were tested for their abilities to use different hydroxycinnamic acids as substrates. Figure 7 shows the substrate-utilization profiles obtained using these substrates at a concentration of 0.2 mm. The two recombinant proteins showed a similar pattern of substrate usage, with a strong preference for 4-coumaric acid and decreasing activities toward ferulic acid, caffeic acid, cinnamic acid, and 5-hydroxyferulic acid. Both recombinant proteins had undetectable activity with sinapic acid. Thus, these enzymes are indistinguishable from each other in their abilities to differentially use these substrates. With the exception of the activity toward cinnamic acid, these substrate-utilization profiles were very similar to those obtained using partially purified native proteins (Fig. 1).

Figure 7.

Substrate-utilization profiles of recombinant 4CL. A, Recombinant 4CL-216; B, recombinant 4CL-9. 4CL enzyme activity (right-hand graphs) was measured using FPLC-purified 4CL-216 or 4CL-9 (left-hand graphs) and 0.2 mm concentrations of hydroxycinnamic acids. Results are averages of three trials; error bars represent sd values. Asterisks indicate the absence of detectable activity. Results are reported as a percentage of the activity against 4-coumaric acid, which was 32.0 pkat/μg protein for 4CL-216 and 119.2 pkat/μg protein for 4CL-9 in the experiment shown.

Purified recombinant 4CL-9 protein was used to determine the kinetic properties of this enzyme. For unknown reasons, the yields of active recombinant 4CL-216 after chromatography were too low to make large-scale purification of the protein and determination of its kinetic properties practical. Table II lists the apparent Km, Vmax, and Vmax/Km values for 4CL-9, determined using 4-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and cinnamic acid as the substrates, all of which fit the Michaelis-Menten equation. Activity toward caffeic acid did not follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics, so the Km and Vmax values could not be calculated. Insufficient 5-hydroxyferulic acid was available for kinetic analysis, and no activity was detectable against sinapic acid. The Km values showed that the enzyme had the highest affinity for 4-coumaric acid, and had a 10-fold lower affinity for cinnamic acid. The Vmax/Km values confirmed that 4CL-9 was most catalytically efficient against 4-coumaric acid, followed by ferulic acid and cinnamic acid.

Table II.

Kinetic properties of recombinant 4CL-9

| Substrate | Km | Relative Km | Vmax | Vmax/Km | Relative Vmax/Kma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | nkat/mg | nkat/mg/μm | |||

| 4-Coumarate | 80 ± 9b | 1 | 353 ± 36 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 1 |

| Ferulate | 102 ± 6 | 1.3 | 190 ± 11 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.43 |

| Cinnamate | 1048 ± 43 | 13.1 | 125 ± 3 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.025 |

| Sinapate | ncc | — | nc | — | — |

Values are relative to the 4-coumarate value (taken as one).

Results are an average of three trials ± sd.

nc, No conversion detected.

DISCUSSION

Native Poplar 4CL Isoforms Share Common Substrate Specificities

4CL converts hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives to activated thioesters that are important substrates for the biosynthesis of lignin, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamate esters, and other phenylpropanoids. We report here the separation of 4CL isoforms from different poplar tissues using FPLC. At least three, and possibly more, forms of the enzyme were resolved using 4-coumarate as a substrate to screen fractions for 4CL activity (Fig. 1). We observed no evidence for differential substrate preferences among these poplar 4CL isoforms, and none showed any significant ability to use sinapic acid as a substrate. These results are in contrast to those of Grand et al. (1983), who reported that three partially purified Populus euramericana 4CL isoforms have different substrate preferences, and that one 4CL form had activity against sinapic acid. However, our findings are consistent with those of other studies that have failed to detect 4CL activity toward sinapic acid in unfractionated preparations from the xylem of P. euramericana and Populus tremuloides (Kutsuki et al., 1982; Meng and Campbell, 1997). We cannot rule out the possibility that a sinapic acid-utilizing 4CL isoform exists, which is inactive against sinapic acid under the conditions we used to assay 4CL activity. As well, such activity could be the result of posttranslational modification of the protein. To further explore these possibilities, the catalytic properties of recombinant proteins expressed from cloned poplar 4CL genes could be investigated.

Poplar 4CL Genes

Several lines of evidence suggest that 4CL is encoded by a moderately sized gene family in the poplar clones we investigated, consistent with the existence of a minimum of three 4CL isoforms in clone poplar H11, as demonstrated in Figure 1. Two 4CL cDNAs, predicted to encode proteins sharing 86% amino acid identity, were isolated from poplar clone H11, an F1 hybrid from a P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides cross. Southern-blot analysis using DNA from the first two generations of a similar cross (Bradshaw et al., 1994) showed that these two cDNAs represent two different genes, 4CL1 and 4CL2, both of which are present in the parents of the hybrid clone. Additional restriction fragments that weakly cross-hybridize to these cDNA clones are present in the parental and hybrid genomes, suggesting that the poplar 4CL gene family includes divergent members in addition to 4CL1 and 4CL2

Northern-blot analysis provided evidence that the two 4CL genes we identified are differentially expressed. Although there appeared to be some overlap in their expression patterns, 4CL1 RNA was most abundant in young leaves, whereas 4CL2 RNA was most abundant in old leaves and somewhat more highly expressed in green stem and xylem than 4CL1. However, neither gene was activated after elicitor treatment of H11 suspension-cultured cells, in contrast to PAL and C4H genes (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992; Subramaniam et al., 1993; N. Mah and C. Douglas, unpublished data). Earlier studies using a heterologous 4CL probe indicated that 4CL gene expression is elicitor activated in these cells (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992). Furthermore, 4CL enzyme activity is strongly induced by elicitor treatment of these cells (Moniz de Sá et al., 1992) and results in accumulation of a single 4CL isoform (Fig. 1B). These data are consistent with the existence of one or more 4CL gene family members that encode elicitor-activated 4CL form(s), distinct from those encoded by 4CL1 and 4CL2.

Recombinant 4CL Proteins

The baculovirus-expressed proteins encoded by 4CL-216 (encoded by the 4CL1 gene) and 4CL-9 (encoded by the 4CL2 gene) were very active both in crude insect cell extracts and in FPLC-purified fractions. Because recombinant tobacco 4CL proteins previously expressed in Escherichia coli are also active (Lee and Douglas, 1996), it is evident that plant-specific modifications of the 4CL protein are not required for its enzymatic activity. The purified recombinant 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 proteins had substrate-utilization profiles similar to each other and to those of the native 4CL isoforms (Fig. 7). In particular, neither of the purified recombinant proteins exhibited any detectable activity with sinapic acid. Thus, we have been unable to obtain evidence from expression of these recombinant proteins that would suggest the presence of poplar 4CL isoforms with distinct substrate-utilization profiles, or the existence of a sinapate-utilizing form of the 4CL enzyme in poplar. However, because we have not cloned the additional, apparently divergent poplar 4CL gene(s), we cannot completely exclude the possibility that 4CL isoforms encoded by such genes could have distinct substrate-utilization profiles when expressed in recombinant form or under other special conditions.

Kinetic analysis of recombinant 4CL-9 (Table II) indicated that the relative ability of the enzyme to use differently substituted cinnamic acids was similar to that of partially purified native forms. Reported Km values for purified or partially purified 4CL proteins (Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1975, 1977; Grand et al., 1983; Voo et al., 1995) range from 6.8 to 32 μm for 4-coumaric acid and from 9.1 to 130 μm for ferulic acid. Thus, the affinities of recombinant 4CL-9 for these substrates (about 80 and 100 μm, respectively), were, on average, several times lower than those reported for these native enzymes. In contrast, the apparent affinity of recombinant 4CL-9 toward cinnamic acid was higher than that reported for most native 4CL enzymes, and was only about 13-fold lower than the value for 4-coumaric acid (relative Km; Table II). This is in contrast to reported affinities of native 4CL forms for cinnamic acid, which range from 40- to 260-fold lower than the affinities for 4-coumaric acid (Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1975, 1977; Voo et al., 1995).

The Vmax/Km value of recombinant 4CL-9 for cinnamic acid was 40-fold lower than this value for 4-coumaric acid (relative Vmax/Km; Table II). In contrast, Vmax/Km values are from 100- to >1000-fold lower for cinnamic acid than for 4-coumaric acid when measured using purified pine, parsley, and soybean 4CL proteins (Knobloch and Hahlbrock, 1975, 1977; Voo et al., 1995). Thus, recombinant 4CL-9 had a greater relative catalytic activity toward cinnamic acid than any plant-derived 4CL enzyme examined to date. Unfortunately, no data are available from this or other studies concerning the kinetic properties of native poplar 4CL proteins toward cinnamic acid.

4CL-9 activity against cinnamic acid seems to be specific to the recombinant form of 4CL. Whereas recombinant 4CL-9 and 4CL-216 readily converted cinnamic acid to the corresponding CoA ester at efficiencies of about 20% of that of 4-coumaric acid (Fig. 7), the partially purified native 4CL isoforms had little or no activity against cinnamic acid under identical assay conditions (Fig. 1). A similar phenomenon was recently described by Lee and Douglas (1996), who showed that two recombinant tobacco 4CL proteins expressed in E. coli have the ability to use cinnamic acid as a substrate but that such 4CL activity was lacking in tobacco stem extracts. In tobacco, a factor or factors in stem tissue, likely to be proteinaceous, has the ability to inhibit the cinnamate-utilizing property of recombinant 4CL-9 without affecting its ability to use other substrates (Lee and Douglas, 1996). A similar activity capable of specifically inhibiting the cinnamate-utilizing activities of recombinant 4CL-216 and 4CL-9 proteins seems to exist in poplar xylem protein extracts (S. Allina, B. Ellis, and C. Douglas, unpublished data). It is interesting to note that the substrate-utilization profile of the pine 4CL enzyme is altered during formation of compression wood (Zhang and Chiang, 1997). These results could be explained by posttranslational modification(s) to 4CL that affect its activity.

4CL and Carbon Flow in Phenylpropanoid Metabolism

The data presented here and other recent data suggest that the mechanisms by which 4CL participates in the regulation of phenylpropanoid carbon flow should be reexamined. Angiosperm lignin, including that of poplar, is composed of both guaiacyl and syringyl subunits that are based on coniferyl and sinapyl alcohol subunits, respectively. However, our data show that 4CL isoforms that directly produce sinapoyl-CoA are unlikely to exist in poplar. Based on kinetic analysis of 4CL-9 and the substrate-utilization profiles of 4CL-216, 4CL-9, and native poplar 4CL isoforms, poplar 4CL enzymes appear to be typical of those described for many plants (Wallis and Rhodes, 1977; Lozoya et al., 1988; Voo et al., 1995; Lee and Douglas, 1996) with activity against 4-coumaric acid > ferulic acid > caffeic acid, and no activity against sinapic acid. It is possible that sinapoyl-CoA in poplar and other plants is made via an alternative pathway involving hydroxylation and methoxylation of the CoA esters of hydroxycinnamic acids (Ye at al., 1994). The absence of activity against sinapic acid, coupled with the apparent absence of catalytically distinct 4CL isoforms in poplar and other plants (Lozoya et al., 1988; Voo et al., 1995; Lee and Douglas, 1996), makes it unlikely that the differential expression of 4CL gene family members encoding enzymes with different substrate-utilization profiles is a mechanism used in poplar, or most other plants, to partition carbon into guaiacyl and syringyl lignin, or into other phenylpropanoid end products. However, there is evidence from tobacco (Lee and Douglas, 1996), pine (Zhang and Chiang, 1997), and now poplar that modification of 4CL enzyme activity, resulting in changes in its substrate-utilization profile, could be important in carbon partitioning. The availability of abundant, catalytically active recombinant 4CL will facilitate future work on the nature of such possible modifications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Elizabeth Molitor for her initial work in the cloning of poplar 4CL-B2, Nancy Mah for expert technical assistance, and Clint Chapple for the gift of 5-hydroxyferulic acid. We are also grateful to Grant McKegney and Sandy Stewart for help with the baculovirus expression system and Maurizio Vurro for preparation of polygalacturonic acid-lyase.

Abbreviations:

- 4CL

4-coumarate:CoA ligase

- C4H

cinnamate-4-hydroxylase

- CAD

cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase

- FPLC

fast-protein liquid chromatography

- PAL

Phe ammonia-lyase

Footnotes

LITERATURE CITED

- Allina SM, Douglas CJ. Isolation and characterization of the 4-coumarate: CoA ligase gene family in a poplar hybrid (abstract No. 852) Plant Physiol. 1994;105:S-154. [Google Scholar]

- Baucher M, Chabbert B, Pilate G, van Doorsselaere J, Tollier MT, Petitconil M, Cornu D, Monties B, Van Montagu M, Inze D and others. Red xylem and higher lignin extractability by down-regulating a cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase in poplar. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1479–1490. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-André M, Schultze-Lefert P, Hahlbrock K. Structural comparison, modes of expression, and putative cis-acting elements of the two 4-coumarate:CoA ligase genes in potato. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8551–8559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw H, Jr, Villar M, Watson B, Otto K, Stewart S, Stettler R. Molecular genetics of growth and development in Populus. III. A genetic linkage map of a hybrid poplar composed of RFLP, STS, and RAPD markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1994;89:167–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00225137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw HD, Jr, Stettler RF. Molecular genetics of growth and development in Populus. I. Triploidy in hybrid poplars. Theor Appl Genet. 1993;86:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00222092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugos RC, Chiang VLC, Campbell WH. cDNA cloning sequence analysis and seasonal expression of lignin-bispecific caffeic acid 5-hydroxyferulic acid O-methyltransferase of aspen. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:1203–1215. doi: 10.1007/BF00028736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MM, Sederoff RR. Variation in lignin content and composition. Mechanisms of control and implications for the genetic improvement of plants. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:3–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Paiva NL. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1085–1097. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas CJ. Phenylpropanoid metabolism and lignin biosynthesis: from weeds to trees. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas CJ, Ellard M, Hauffe KD, Molitor E, Moniz de Sá M, Reinold S, Subramaniam R, Williams F (1992) General phenylpropanoid metabolism: regulation by environmental and developmental signals. In HA Stafford, RK Ibrahim, eds, Recent Advances in Phytochemistry, Vol 26. Plenum Press, New York, pp 63–89

- Dumas U, van Doorsselaere J, Gielen J, LeGrand M, Fritig B, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Nucleotide sequence of a complementary DNA encoding O-methyltransferase from poplar. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:796–797. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.2.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L, Chiang V. A full length cDNA encoding trans-cinnamate 4-hydroxylase from developing xylem of Populus tremuloides (accession no. U47293) (PGR 96-075) Plant Physiol. 1996;112:861. [Google Scholar]

- Grand C, Boudet A, Boudet AM. Isoenzymes of hydroxycinnamate:CoA ligase from poplar stems: properties and tissue distribution. Planta. 1983;158:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF01075258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GG, Zenk MH. Isolation and properties of hydroxycinnamate:CoA ligase from lignifying tissue of Forsythia. Eur J Biochem. 1974;42:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Physiology and molecular biology of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1989;40:347–469. [Google Scholar]

- Holton TA, Cornish EC. Genetics and biochemistry of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1071–1083. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes WD, Galau G. Preparations of RNA from cotton leaves and pollen. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1988;6:253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen A, Cuellar E, Thompson F. Modes and tempos in the evolution of nuclear-encoded ribosomal RNA genes in legumes. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book. 1982;81:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai S, Mori A, Shiokawa T, Kajita S, Katayama Y, Morohoshi N. Isolation and analysis for cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase homologous genes from a hybrid aspen, Populus kitakamiensis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1586–1597. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch K-H, Hahlbrock K. Isoenzymes of p-coumarate:CoA ligase from cell suspensions of Glycine max. Eur J Biochem. 1975;52:311–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch K-H, Hahlbrock K. 4-Coumarate:CoA ligase from cell suspension cultures of Petroselinum hortense. Hoffm. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;184:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsuki H, Shimada M, Higuchi T. Distribution and roles of p-hydroxycinnamate:CoA ligase in lignin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Douglas CJ. Two divergent members of a tobacco 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase (4CL) gene family. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:193–205. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoya E, Hoffmann H, Douglas CJ, Schulz W, Scheel D, Hahlbrock K. Primary structure and catalytic properties of isoenzymes encoded by the two 4-coumarate:CoA ligase genes in parsley. Eur J Biochem. 1988;176:661–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Campbell WH. Facile enzymatic synthesis of caffeoyl CoA. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:605–608. [Google Scholar]

- Moniz de Sá M, Subramaniam R, Williams FE, Douglas CJ. Rapid activation of phenylpropanoid metabolism in elicitor-treated hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa Torr and Gray × Populus deltoidesMarsh) suspension-cultured cells. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:728–737. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe Y, Osakabe K, Kawai S, Katayama Y, Morohoshi N. Characterization of the structure and determination of mRNA levels of the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family from Populus kitakamiensis. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;28:1133–1141. doi: 10.1007/BF00032674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragg H, Kuhn D, Hahlbrock K. Coordinated regulation of 4-coumarate:CoA ligase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase mRNAs in cultured plant cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:10061–10065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjeva R, Boudet AM, Faggion R. Phenolic metabolism in Petunia tissues. IV. Properties of p-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase isozymes. Biochemie. 1976;58:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(76)80125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals JA, Neuenschwander UH, Willits MG, Molina A, Steiner HY, Hunt MD. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1809–1819. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam R, Reinold S, Molitor EK, Douglas CJ. Structure, inheritance, and expression of hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa × Populus deltoides) phenylalanine ammonia-lyase genes. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:71–83. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MD, Smith GE (1987) A manual of methods for baculovirus vectors and insect cell culture procedures. Tex Agric Exp Stn Bull No. 1555

- Uhlmann A, Ebel J. Molecular cloning and expression of 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase, an enzyme involved in the resistance of soybean (Glycine maxL.) against pathogen infection. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1147–1156. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorsselaere J, Baucher M, Chognot E, Chabbert B, Tollier M-T, Petit-Conil M, Leplé J-C, Pilate G, Cornu D, Monties B and others. A novel lignin in poplar trees with reduced caffeic acid/5-hydroxyferulic acid O-methyltransferase activity. Plant J. 1995a;8:855–864. [Google Scholar]

- van Doorsselaere J, Baucher M, Feuillet C, Boudet AM, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Isolation of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase cDNAs from two important economic species: alfalfa and poplar. Demonstration of a high homology of the gene within angiosperms Plant Physiol Biochem. 1995b;33:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Voo KS, Whetten RW, O'Malley DM, Sederoff RR. 4-Coumarate:coenzyme A ligase from loblolly pine xylem. Isolation, characterization, and complementary DNA cloning. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:85–97. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis PJ, Rhodes MJC. Multiple forms of hydroxycinnamate:CoA ligase in etiolated pea seedlings. Phytochemistry. 1977;16:1891–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Webb NR, Summers MD. Expression of proteins using recombinant baculoviruses. Technique. 1990;2:173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Whetten R, Sederoff R. Lignin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1001–1013. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye ZH, Kneusel RE, Matern U, Varner JE. An alternative methylation pathway in lignin biosynthesis in Zinnia. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1427–1439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X-H, Chiang V. Molecular cloning of 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase in loblolly pine and the roles of this enzyme in the biosynthesis of lignin in compression wood. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:65–74. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]