Abstract

In the spring of 1957, an outbreak of severe disease was documented in people living near the Kyasanur Forest in Karnataka state, India, which also affected wild nonhuman primates. Collection of samples from dead animals and the use of classical virological techniques led to the isolation of a previously unrecognized virus, named Kyasanur Forest disease virus (KFDV), which was found to be related to the Russian spring-summer encephalitis (RSSE) complex of tick-borne viruses. Further evaluation found that KFD, which frequently took the form of a hemorrhagic syndrome, differed from most other RSSE virus infections, which were characterized by neurologic disease. Its association with illness in wild primates was also unique. Hemaphysalis spinigera was identified as the probable tick vector. Despite an estimated annual incidence in India of 400–500 cases, KFD is historically understudied. Most of what is known about the disease comes from studies in the late 1950s and early 1960s by the Virus Research Center in Pune, India and their collaborators at the Rockefeller Foundation. A report in ProMED in early 2012 indicated that the number of cases of KFD this year is possibly the largest since 2005, reminding us that there are significant gaps in our knowledge of the disease, including many aspects of its pathogenesis, the host response to infection and potential therapeutic options. A vaccine is currently in use in India, but efforts could be made to improve its long-term efficacy.

Keywords: Kyasanur Forest disease, Alkhurma virus, tick-borne encephalitis, flavivirus

I. Introduction

In February, 2012, ProMED cited reports in The Hindu (www.thehindu.com) of an on-going outbreak of Kyasanur Forest disease (KFD) in Tirhahalli and Hosanager taluks (counties) in the Shimoga district of India, with 176 suspected and 38 confirmed cases since the beginning of the year (REF). These reports serve as a reminder that KFD is a significant public health problem in that region, and that outbreaks occur with some frequency. It has been estimated that an average of 400–500 cases of KFD occur per year in India (Pavri, 1989; Work et al., 1957). From 2003 through late March 2012 there were 3263 suspected cases, with 823 confirmed cases and 28 deaths, a 3.4% case fatality rate (CFR) (Table 1). Similar diseases have been reported in China and Saudi Arabia since 1995, and there is serological evidence of KFDV infection in other parts of India.

Table 1.

Incidence of KFD in Karnataka State, India, through March 24, 2012. Data kindly provided by Dr. Sulochana

| Year | Total villages |

Total cases |

Hospitalized cases |

Confirmed cases* |

Confirmed deaths |

NHP deaths |

NHP cases confirmed* |

Arthropod/ tick pools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 218 | 953 | 725 | 306 | 11 | 132 | 11 | 112 |

| 2004 | 121 | 568 | 311 | 153 | 5 | 86 | 8 | 134 |

| 2005 | 179 | 661 | 521 | 63 | 7 | 53 | 4 | 113 |

| 2006 | 123 | 354 | 246 | 99 | 2 | 54 | 3 | 166 |

| 2007 | 23 | 76 | 30 | 14 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 112 |

| 2008 | 29 | 112 | 31 | 36 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 139 |

| 2009 | 57 | 179 | 139 | 64 | 1 | 72 | 1 | 133 |

| 2010 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 117 |

| 2011 | 20 | 41 | 17 | 19 | 1 | 35 | 4 | 278 |

| 2012 | 141 | 314 | 294 | 69 | 1 | 27 | 2 | 130 |

| Total | 917 | 3263 | 2314 | 823 | 28 | 529 | 33 | 1434 |

Despite the frequent occurrence of KFD in its endemic area, relatively little is known about its pathogenic mechanisms or the host response to infection. There is also some debate regarding its typical manifestations, beyond an acute febrile illness. As discussed below, KFD was initially described as a type of viral hemorrhagic fever, but overt bleeding does not occur in all cases. Also, in contrast to related flaviviruses in the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) serocomplex, KFDV rarely causes severe neurologic illness. Because may virologists are unfamiliar with the disease, the goal of this article is to review the history of KFD and highlight the importance of the disease and others caused by closely related flaviviruses.

II. History

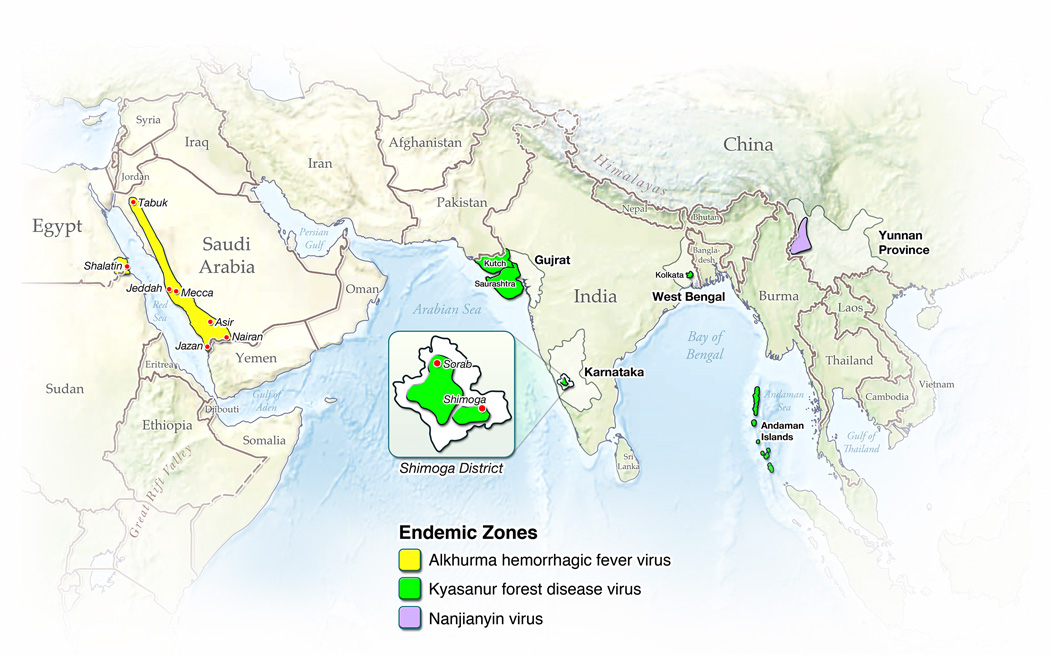

KFDV was first isolated during an outbreak of febrile disease in 1957 in people living in the Kyasanur forest area of the Shimoga district in the Karnataka (then Mysore) state of India (Work and Trapido, 1957; Work et al., 1957) (Figure 1). Reports of a large number of deaths among local nonhuman primates (NHPs) provided the first evidence of an epizootic of unknown etiology. When investigators from the Virus Research Center in Pune arrived, district health officials reported that there had been a number of cases of severe febrile illness in residents of villages close to forested areas where dead monkeys had been found (Work, 1958). Although retrospective reports suggested that the outbreak had begun in early 1956, the description in March, 1957 provided the first clear identification of a previously undocumented disease (Work, 1958).

Figure 1.

Geographic areas where KFDV and related viruses have been reported. KFD routinely occurs in the highlighted area of the Shimoga district in India.

Initial serologic studies indicated that the novel illness was caused by a virus related to the Russian spring-summer encephalitis (RSSE) complex of arboviruses, now known as the tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) serocomplex of flaviviruses, which are typically associated with a neurologic syndrome. However, clinical descriptions suggested that the new disease resembled Omsk hemorrhagic fever (OHF), a member of the RSSE complex first described in 1948, which is characterized by hemorrhagic, rather than neurologic abnormalities (Chumakov, 1948; Work, 1958) (Table 2). In the early 1950s, serologic surveys found that a RSSEV-related agent was circulating in Bombay (now Gujarat) State in Western India, northwest of Mumbai (Smithburn et al., 1954) (Figure 1), but those studies could not conclusively identify the virus.

Table 2.

Summary of basic characteristics of viruses from the tick-borne encephalitis complex that are significant human pathogens.

| Virus | Endemic zone | General features of disease in humans | Approximate case fatality rate (%) |

Known animal reservoir(s) |

Principal tick vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western-subtype TBEV |

Northeastern Europe | Typically sudden onset, with a bi-phasic illness. Neurological abnormalities can develop during the second phase, but are usually not severe. Neurologic sequelae |

0.5–2 | Rodents | Ixodes ricinus |

| Siberian-subtype TBEV |

Siberia/Central Asia | Typically a bi-phasic illness with evidence of neurological disease in patients who progress to the second phase. Sequelae are uncommon. Has been associated with persistent infection in humans and nonhuman primates. |

1–3 | Rodents | Ix. persulcatus |

| Far-eastern-subtype TBEV |

Central Asia/Far-east Asia |

Severe disease than can be bi-phasic, but often progresses directly to neurologic disease. Sequelae are common in survivors. |

5–20 | Rodents | Ix. persulcatus |

| Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus |

Omsk/Novosibirsk Oblasts, south-central Russia |

Generally mild or sub-clinical, but can result in hemorrhagic fever and death. Neurologic disease is rare. |

0.5–3 | Muskrats, water voles |

Dermacentor reticulatus |

| Powassan virus | Canada, United States, Russia |

Generally mild or sub-clinical. Severe disease characterized by encephalitis. |

20 | Rodents | Ix. spp |

| Langat virus | Malyasia | Generally apathogenic in humans. | Unknown | Unknown | Ix. granulatus |

| Louping ill virus | Europe | Generally apathogenic in humans. | 0 | Goats, sheep, hares, rodents |

Ix. ricinus |

| Kyasanur Forest disease virus |

India | Frequently a bi-phasic disease that can result in fatal hemorrhagic fever. Neurological abnormalities are seen, but are not manifested as meningitis or |

3–5 | Rodents |

Hemaphysalis spinigera |

| Alkhurma virus | Saudi Arabia, Egypt | Resembles KFD. | 1–25 | Unknown |

Ornithodoros savignyi |

The 1957 outbreak in the Kyasanur Forest coincided with the observation of high mortality in the local NHP population, including red-faced bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata) and black-faced (Hanuman) langurs (Semnopithecus entellus, previously known as Presbytis entellus). The occurrence of a fatal disease in wild primates initially raised concern that yellow fever virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus that causes severe hemorrhagic disease, had been introduced into India. Fortunately, this was not the case. Virus isolations were made in suckling mice inoculated with serum or tissues from a black-faced langur found moribund in the forest (Bhatt et al., 1966; Work and Trapido, 1957). The identification of KFDV provided the first conclusive evidence that a tick-borne flavivirus was circulating in India.

The factors responsible for the appearance of a new viral infection were not clear. In the 1950s, there had been a significant increase in the human population in the Sagar taluk within the Shimoga district (Boshell, 1969), resulting in significant changes in the local ecosystem, including deforestation and new land-use practices for farming and timber harvesting (Boshell, 1969). Although impossible to prove, it appears that encroachment by humans into the primal forest may have led to exposure to new pathogens, such as KFDV. However, although there is no documented evidence of the disease before the 1956–57 outbreak, the virus might already have been circulating in the area, only occasionally affecting humans. Similarly, deaths of local NHPs may not have been recognized as a new disease, or may have been ascribed to a different cause. Boshell indicates that earlier incidents of increased mortality in local NHPs were assumed to be caused by plague or, in 1918, by the influenza pandemic (Boshell, 1969).

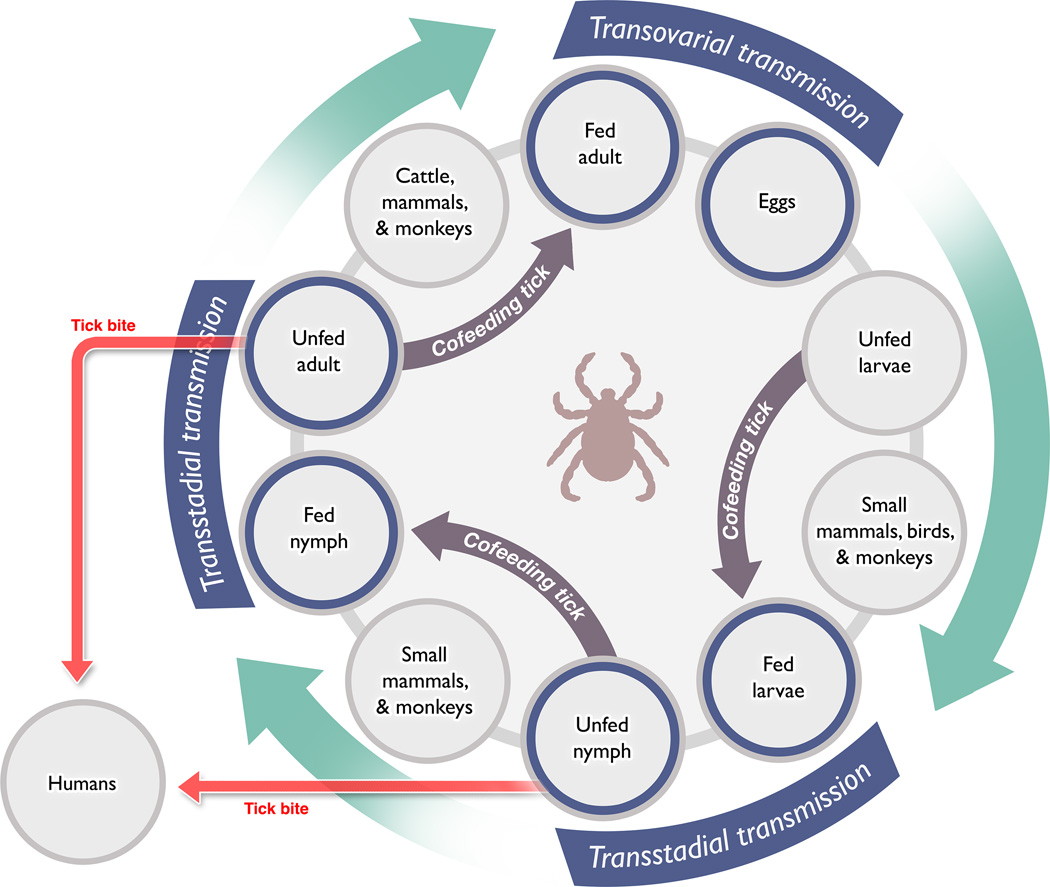

Following the determination that KFDV was related to the tick-borne flaviviruses, researchers began to collect local arthropods in an effort to identify the vector. Hemaphysalis spp. ticks were recovered from some dead or moribund primates, and analysis identified H. spinigera as the likely vector, following isolation of virus from some larvae and nymphs of this species (Figure 2) (Trapido et al., 1959; Work, 1958). Subsequent experimental work found that several other Hemaphysalis species were competent vectors or potential reservoirs, as KFDV was isolated from the ticks, and experimental transmission was demonstrated (Bhat and Naik, 1978; Bhat et al., 1975; Boshell and Rajagopalan, 1968; Singh and Bhatt, 1968; Singh et al., 1968; Singh et al., 1963; Singh et al., 1964; Varma et al., 1960). Several other genera of local ticks have also been shown to be capable of transmitting KFDV, including members of the Argas, Dermacentor, Hyalomma, Ixodes, Ornithodoros and Rhipicephalus genera (Bhat and Naik, 1978; Bhat et al., 1978; Bhat et al., 1975). There is no evidence that mosquitoes are a competent vector for KFDV or for other tick-borne flaviviruses.

Figure 2.

The generalized transmission cycle of KFDV in ticks, with an indication of potential animal reservoirs. Infection of large mammals, wild primates and humans is unlikely to generate a sufficiently high level of viremia for transmission to ticks. Co-feeding has been shown to transmit viruses from infected to uninfected ticks, and is the most likely route of tick-to-tick transmission.

Small mammals, especially rodents, have long been considered reservoirs for the tick-borne flaviviruses, meaning that they can become infected by a virus and develop a low-level viremia, sufficient for transmission to a blood-feeding arthropod, without becoming ill. A reservoir species is critical for the maintenance of many viruses which circulate between the vector and the reservoir. Rodents are ideal maintenance hosts, because their generation time is short, so that there is nearly always a large population of naïve animals. In the case of the TBEV serocomplex, a mammalan reservoir is perhaps less critical to viral maintenance than previously thought, because the pathogens can be maintained through transstadial and trans-ovarial transmission in ticks. There is also increasing evidence that co-feeding of ticks on a mammalian host provides a more efficient means of virus transmission among ticks than taking a blood meal from a viremic animal (Randolph, 2011) (Figure 2). Vertical transmission of some viruses also occurs in mosquitoes, but their short life-span could limit the ability of a virus to be maintained solely in mosquito populations. In contrast, ticks may live for several years. A number of studies have evaluated the potential for small mammals to support KFDV infection and participate in its maintenance. These studies were performed as serosurveys of wild-caught animals or as experimental laboratory infections, as summarized by Pattnaik (Pattnaik, 2006). No single small animal species stands out as a likely reservoir for KFDV, further supporting the notion that the virus is maintained in ticks.

Epizootics of KFD are largely sustained in local NHP populations, where black-faced langurs and red-faced bonnet macaques succumb to infection. Outbreaks in wild primates were reported from 1957–1964 (Goverdhan et al., 1974) and 1964–1973 (Sreenivasan et al., 1986); the first report focused largely on epizootics within the established region of KFD endemicity, while the latter expanded its known range. In both cases, it appeared that black-faced langurs were more susceptible to the virus, with confirmed evidence of infection in half of the animals necropsied (Sreenivasan et al., 1986). Most epizootics occurred in the dry season from December to May, correlating with an increase in the Hemaphysalis tick population (Rajagopalan et al., 1968a, b).

Since the identification of KFD in 1957, its estimated incidence in India has been 400–500 cases per year (Pavri, 1989; Work et al., 1957). Between 2003 and late March, 2012 there were 3263 reported human cases, 823 of which were laboratory-confirmed, with a CFR of 3.4% (Table 1). Large numbers of human infections were reported in 2003–4, but a significant decline occurred in 2007 and again in 2010–2011. The frequency of cases in 2003–11 can be correlated with the number of confirmed KFD- infected NHPs (Table 1). From January through late March, 2012 there were 314 reported cases of KFD, of which 69 were confirmed, with 1 death (a confirmed CFR of 1.4%). Rapid diagnostic methods based on nested RT-PCR, real-time RT-PCR and IgM capture ELISA have recently been described (Mourya et al., 2012).

KFD was thought for many years to be endemic to a relatively localized region within Karnataka state, with a principal focus in the Shimoga district. However, serological evidence obtained since the 1950s suggests that KFDV or related viruses are present in other areas of India, including parts of Kutch district, the Saurashtra region in Gujarat state, and in parts of West Bengal state, in forested regions west of Kolkata (previously Calcutta) (Pattnaik, 2006; Sarkar and Chatterjee, 1962). Serological evidence of KFDV has also been found in the Andaman Islands, particularly Little Andaman, where surveys in 1988–89 indicated the presence of KFDV or a closely related tick-borne flavivirus (Padbidri et al., 2002). Variants of KFDV have also been reported in Saudi Arabia and China (see below).

III. Clinical features

Initial descriptions of KFD focused largely on its hemorrhagic component, and did not identify significant signs of neurological disease (Work et al., 1957). The presumption that KFD was a type of viral hemorrhagic fever was based on findings in two fatal cases, which showed hemorrhage and consolidation in the lungs and significant bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract (See first KFD case summary in sidebar) (Work, 1958). These observations suggested that the new disease resembled some other recently identified acute febrile conditions, including some caused by TBE serocomplex viruses. In particular, KFD resembled OHF, which had recently been described as a hemorrhagic disease with limited evidence of encephalitis, and which differed from other members of the TBE serocomplex, which were associated with meningoencephalitis (Chumakov, 1948; Work, 1958). In one report of 7 cases of KFD, the syndromes ranged from a nonspecific febrile illness to a fatal hemorrhagic disease, compounded by dehydration (Work et al., 1957). One patient apparently survived due to the provision of intravenous fluids.

Evaluation of additional patients with KFD suggested evidence of neurologic disease, including tremors, nuchal rigidity, disorientation and confusion, but analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and postmortem examination did not reveal a clear indications of meningitis or encephalitis (Work et al., 1957). Subsequent studies focusing on the neurologic aspects of KFDV infection suggested that the virus might be more closely related to louping ill virus, a flavivirus which primarily infects sheep, but can also cause disease in humans (Davidson et al., 1991; Rivers and Schwentker, 1934; Webb and Rao, 1961). However, there may have been some confusion at the time between louping ill and what is now known as Western subtype or Central European TBE, which is seen in large parts of eastern Europe.

Since the initial KFD outbreak, more complete reports of its clinical features have been published, including some laboratory-acquired infections with known exposure times and circumstances (See Sidebar). They generally describe a biphasic illness, not unlike TBE, but with some hemorrhagic manifestations not seen in TBE. Initial signs and symptoms typically begin 3–8 days after exposure, with the sudden onset of fever, chills, headache and myalgia (Pavri, 1989; Webb and Rao, 1961). The initial phase may also be characterized by local or generalized lymphadenopathy, suffusion of the conjunctiva, photophobia, petechial hemorrhages on the mucous membranes and bleeding from the nose, mouth or gastrointestinal tract (Pavri, 1989; Work, 1958). However, there is no evidence of significant disruption of the hematopoetic system or loss of vascular integrity.

Most patients begin to recover after 14 days, but in some cases, a 7–14 day period of remission is followed by a second phase dominated by neurologic manifestations, which may include severe headache, mental disturbance, tremors, rigidity, photophobia, eye pain and defective vision (Anonymous, 1983). In one study, generalized convulsions occurred in 24 patients, associated with a poor outcome (Adhikari Prabha, 1993). However, neither clinical indications nor postmortem studies have provided any clear evidence of meningitis or encephalitis (Adhikari Prabha, 1993; Work, 1958). Patients recovering from KFD are generally lethargic for several weeks, and some continue to have hand tremors or unsteadiness, which eventually resolves (Wadia, 1975; Work, 1958; Work et al., 1957). Long-term sequelae are rare.

IV. Pathologic findings

Gross and microscopic examination of tissues from fatal KFD cases have found evidence of a largely non-specific disease process, with prominence of macrophages and lymphocytes in the liver and spleen, moderate parenchymal degeneration in the liver and kidneys and evidence of erythrophagocytosis in the spleen. Some have shown hemorrhagic pneumonia (Iyer et al., 1959; Pavri, 1989). As indicated previously, in the few reports that describe neurological disease, it may best be described as aseptic meningitis (Wadia, 1975). Several postmorem studies have found no abnormalities in the brain or spinal cord, while others have described cerebral edema or minimal infiltration of inflammatory cells (Adhikari Prabha, 1993; Pavri, 1989; Work et al., 1957). There are no clinical or laboratory findings suggesting that encephalitis is a significant component of KFD.

V. KFDV infection of NHPs

A. Natural infection

The evaluation of KFDV infection in NHPs has only been performed through necropsies of animals found sick or dead in the forest; no studies have described the natural course of illness. Postmortem findings resembled the nonspecific disease seen in humans (Work, 1958). The liver architecture was well preserved, but areas of necrosis were more pronounced than in humans; infiltrates of inflammatory cells, including hypertrophic or multinucleated cells of reticuloendothelial origin, and eosinophilic inclusions were also apparent. Abnormalities in other organs were limited to focal inflammatory infiltrates. In contrast to human cases, the brains of two fatally infected monkeys showed clear evidence of encephalitis (Work, 1958).

B. Experimental infections of NHPs

Rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) infected with KFDV did not become ill, though most animals became viremic, and all of them developed neutralizing antibodies to the virus (Work, 1958). Further studies found that red-faced bonnet macaques (M. radiata), which develop KFD under natural circumstances, were quite susceptible to experimental infection. Clinical features seen in both humans and M. radiata included bradycardia, hypotension, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, lymphopenia and anemia, which were thought to result from erythrophagocytosis or lymphophagocytosis (Webb and Chaterjea, 1962; Webb and Rao, 1961) (Kenyon et al., 1992; Webb and Chaterjea, 1962). As in humans, the principal histologic abnormalities at necropsy were in the liver and kidneys (Iyer et al., 1959; Webb and Burston, 1966; Work et al., 1957). In a 1992 study, all 7 bonnet macaques developed diarrhea by day 4 and died by day 9 postinfection, but none showed clear evidence of hemorrhage (Kenyon et al., 1992). Together with human studies, these data indicate that bleeding is not a standard feature of KFD.

M. radiata infected with KFDV may develop neurologic disease more frequently than humans, but it is not considered a major component of the disease, and findings have been inconsistent within and between studies. In one report, perivascular cuffing was seen in the brain of a macaque at necropsy, but there was no necrosis indicative of viral encephalitis (Work et al., 1957). In another study, one of 9 infected animals died 22 days postchallenge, similar to the time course of humans with biphasic KFD, and changes consistent with encephalitis were seen at necropsy (Webb and Burston, 1966). None of the others showed histologic evidence of neurologic disease.

C. Experimental studies in rodents

In early studies of KFD, suckling mice were used for the propagation and identification of virus through the intracerebral (IC) inoculation of serum or tissues from wild primates or patients (Work, 1958; Work et al., 1957). At that time, the use of suckling mice was a standard means of cultivating most arboviruses and for generating viral antigen to be used for development of virus specific antibodies and diagnostic tools (e.g., hemagglutination inhibition assays). Sub-adult mice infected with KFDV via the subcutaneous (SC) or intraperitoneal (IP) routes also developed disease (Work, 1958). Further studies using Swiss albino mice found that 2–3 day old mice challenged IC succumbed to disease in 4–6 days, while 3–4 week old mice died in 5–7 days (Nayar, 1972). Unlike humans and NHPs, adult mice infected IC or IP developed histologic signs of encephalitis (Nayar, 1972). Adult mice challenged IP died within 9 days, and many developed paralysis, as seen in other murine TBEV infections; this model has therefore been used to assess KFD vaccine efficacy (Mansharamani and Dandawate, 1967) (Nayar, 1972).

Unlike humans and NHPs, suckling and adult mice infected with KFDV do not develop histologic abnormalities in the liver or spleen (Nayar, 1972). The laboratory mouse is therefore not an ideal model for evaluating KFD pathogenesis, because the disease in these animals does not mimic the human condition. Wild-caught rodents or other species, such as hamsters, may turn out to be a better model for studying KFD. However, some wild-caught rodents may be potential natural reservoirs for the virus, and might not develop disease (Pattnaik, 2006).

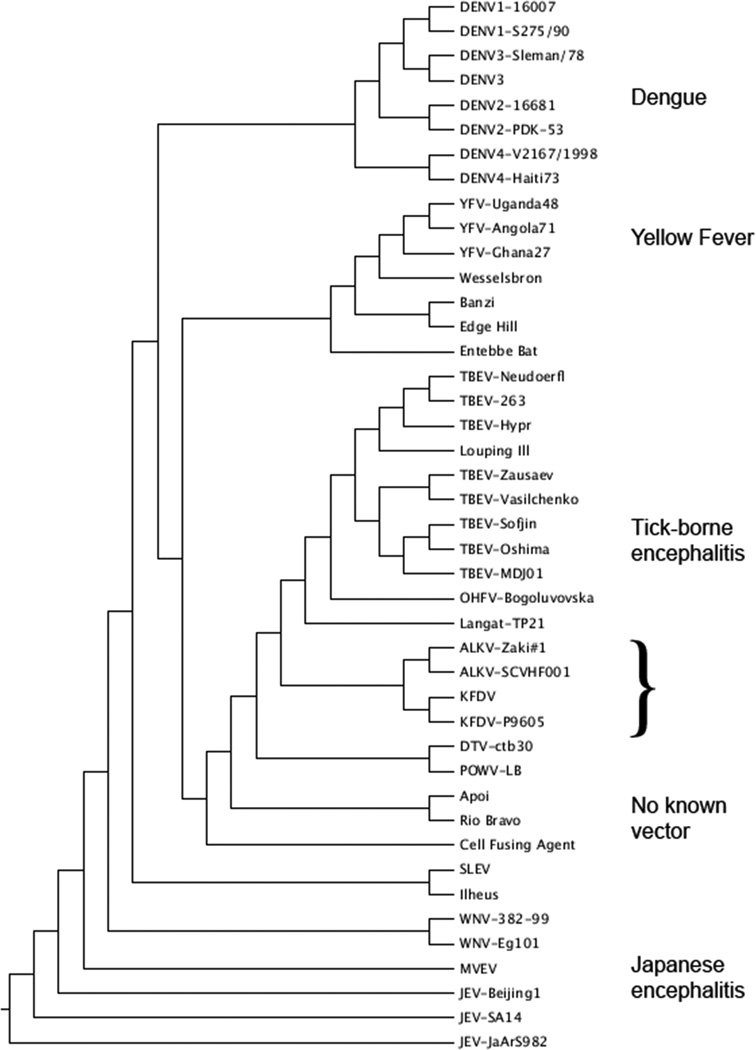

VI. Related viruses

Kyasanur Forest disease virus is member of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. The flaviviruses are genetically divided into two major clades, those transmitted by mosquitoes and those transmitted by ticks. The mosquito-vectored viruses are further subdivided into three serocomplexes of closely related viruses: yellow fever, dengue and Japanese encephalitis, which includes West Nile virus (Gubler et al., 2007). Tick-borne viruses in the TBEV serocomplex are closely related, with less than 30% nucleotide sequence divergence (Lin et al., 2003). They range from agents that have not been associated with human disease, such as Langat and louping ill viruses, to those that cause severe human disease (Table 2).

The TBEV group is made up in turn of 3 subgroups, defined genetically and by clinical presentation (LaSala and Holbrook, 2010). The Western subtype of TBEV (formerly known as Central European encephalitis virus) causes neurological disease with a relatively low CFR, while the Far Eastern subtype causes the most severe severe illness, with the highest CFR and frequency of neurological sequelae. The Siberian subtype of TBEV shows a more intermediate level of virulence, but it has been associated with chronic infections (LaSala and Holbrook, 2010). Powassan virus is found in parts of the United States and Canada, where it is an uncommon cause of encephalitis (LaSala and Holbrook, 2010).

Like KFDV, Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (OHFV) can cause hemorrhagic disease in humans. However, OHF cases are more frequently associated with overt bleeding from mucous membranes and prominent development of petechial hemorrhages (Ruzek et al., 2010). Significant neurological signs are uncommon, and patients rarely develop sequelae associated with neurologic disease. Mortality rates for OHF have been reported from 0.4–2.5%; those who recover have few, if any, long-term sequelae (Ruzek et al., 2010). OHF occurs in the Omsk, Novosibirsk, Tjumen and Kurgan regions of south-central Russia. Since 1988, nearly all human cases have been seen in the Novosibirsk region. Although the frequency of officially identified cases has declined significantly since the disease was first recognized in the mid-1940s, subclinical infections may still occur (Ruzek et al., 2010).

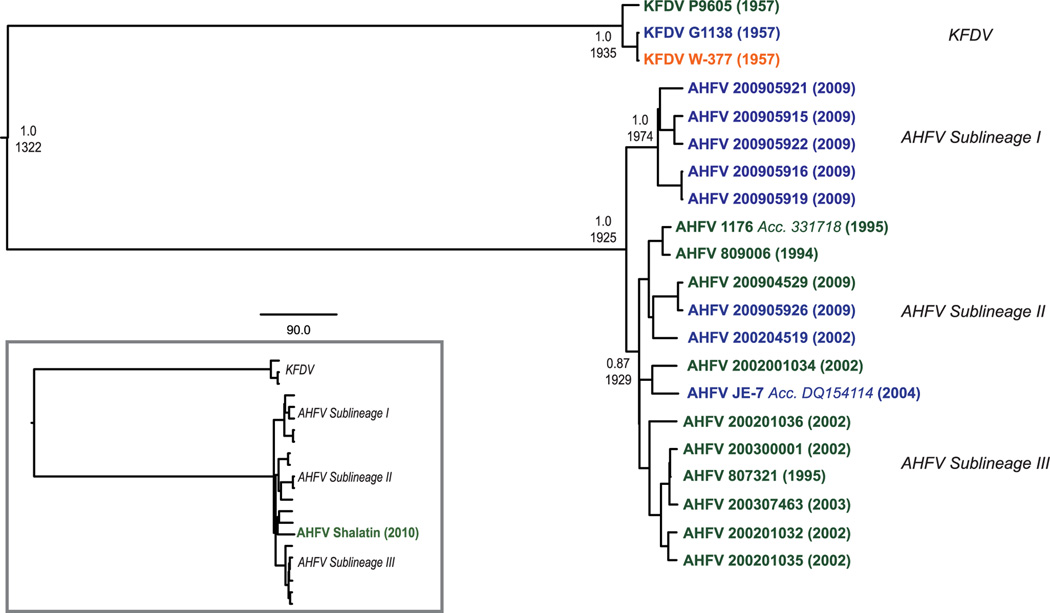

In 1995, a variant of KFDV, subsequently named Alkhurma HF virus (AHFV), was isolated from patients in a disease outbreak near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in which there were 10 cases and 2 deaths (Zaki, 1997) (Figure 1). Eight of the patients worked with sheep. The virus was subsequently isolated from Ornithodoros savignyi, a tick that is associated with camels and their resting places, and the camel tick Hyalomma dromedarii (Charrel et al., 2007) (Mahdi et al., 2011). Since the initial outbreak, cases OF AHF have been confirmed in Jeddah, Makkah and Najran, Saudi Arabia, where they are largely seen in individuals who work with or butcher sheep or camels (Alzahrani et al., 2010; Madani, 2005; Madani et al., 2011; Mahdi et al., 2011). Serosurveys of soldiers reporting to Jazan province suggest that AHF is more widespread than previously thought, with serological evidence of the virus in Tabuk, Asir and AsSharqiyah provinces (Memish et al., 2011). AHFV has also been detected outside of Saudi Arabia, near the border between Egypt and Sudan, and in exported cases in Italy in 2010; the latter had all visited the town of Shalatin (alt. Shalateen), Egypt, which has a large camel market and is likely to have a large number of ticks (Carletti et al., 2010; Ravanini et al., 2011).

AHF resembles KFD in its clinical features. Initial reports of the disease in Jeddah and Makkah suggested an approximately 25% CFR, but a more recent report of cases near Najran found that the mortality rate was considerably lower (Madani, 2005; Zaki, 1997)(Madani et al., 2011). As with many viral infections, the incidence and CFR may be confounded by the limited number of known cases, unreported mild illnesses and the occurrence of subclinical infections. AHFV was initially thought to be an exported variant of KFDV, but recent genetic analysis has identified three sublineages of AHFV, and indicates that KFDV and AHFV diverged from a common ancestor approximately 700 years ago (Dodd et al., 2011) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic trees showing the relationships among the flaviviruses and the relationship between KFDV and AHFV, with their approximate time of divergence from a common ancestor.

A. Maximum likelihood tree of the flaviviruses, based on full genome sequences available in Genbank.

B. Maximum likelihood tree showing the relationship of KFDV and AHFV, adapted from Dodd et al. (Dodd et al., 2011).

In 1989, a virus was isolated from a patient suffering from an acute febrile illness in the Chinese province of Yunnan, which abuts the northeastern border of Burma (Figure 1). Subsequent analysis indicated that this “Nanjianyin virus” was nearly identical to some strains of KFDV (Wang et al., 2009). However, it was also identical to a reference strain used in the study, suggesting laboratory contamination (Mehla et al., 2009). Surveys carried out from 1987–1990 in Yunnan province indicated a relatively high (~20%) prevalence of KFDV-seropositive individuals in 6 counties and a lower (~4%) prevalence in 3 other counties (Wang et al., 2009). These data indicate that KFDV (aka Nanjianyin virus) or a closely related tick-borne flavivirus may circulate in parts of southwestern China.

VII. Vaccines

The first KFD vaccine was a formalin-inactivated, mouse-brain preparation of RSSEV produced by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research at the request of the Indian Council of Medical Research, with the assistance of the Rockefeller Foundation (Aniker et al., 1962). RSSEV was known to be closely related antigenically to KFDV, and was therefore hypothesized to provide cross-protection. The RSSEV vaccine protected mice against KFDV challenge, and was more efficacious than another vaccine prepared from KFDV isolates (Aniker et al., 1962).

Over the course of 15 months in 1958–59, the formalin-inactivated RSSEV vaccine was provided to people within the KFD endemic area, beginning with government personnel, followed by people at the edge of the known endemic zone who were unlikely to have pre-existing immunity, and finishing with people in villages where KFD had occurred (Aniker et al., 1962; Shah et al., 1962). The vaccine was inoculated SC on a three-dose schedule at 0, 7 and 42 days, though logistical challenges extended the schedule significantly in some areas. More than 10,000 people received at least one dose, and nearly 5000 received all 3 doses, with no reports of complications (Aniker et al., 1962). Of the 1270 government employees vaccinated, 795 were tested for an antibody response, as determined by complement fixation, hemagglutination inhibition and passive transfer challenge studies in mice.

Investigators found that the RSSEV vaccine did not stimulate a strong response against KFDV, and it did not stimulate an anamnestic response in people who had previously been exposed to the virus (Pavri et al., 1962). Epidemiologic studies performed after the campaign also suggested that the vaccine did not prevent KFD, as the incidence of disease in vaccinated villagers was not significantly lower than in unvaccinated people (Shah et al., 1962). However, the authors admitted that, because the vaccine program was not a clinical study, but an effort to control the disease, the analysis was not well controlled, and reporting bias and the small total case numbers limited its value (Aniker et al., 1962; Shah et al., 1962).

A subsequent effort to produce a vaccine based on KFDV, rather than RSSEV, was moderately effective. A formalin-inactivated vaccine produced by the Haffkine Institute in Bombay (now Mumbai) in chick embryo fibroblasts was given to 87 volunteers at the Virus Research Centre in Poona, following a two-dose schedule (Banerjee et al., 1969). Of 58 workers lacking previous immunity, 50% developed neutralizing antibodies against KFDV (Banerjee et al., 1969). Field testing in 56 villages in Sagar and Sorab taluks found that, of 1989 people vaccinated, 60% seroconverted. Over the next 4 years, only one case of KFD was documented in a vaccinated individual (Upadhyaya et al., 1979).

A formalin-inactivated, chick embryo fibroblast vaccine, developed in the early 1990s, is currently licensed and available in India. It is given in a two-dose schedule, followed by routine boosts. It was initially field-tested in about 90,000 people, of whom approximately 61,000 received both doses (Dandawate et al., 1994). It was well tolerated and was relatively protective, as only 24 members (0.027%) of the vaccinated group contracted KFD during the two-year study (1990–1992), compared to 325 members (0.86%) of an unvaccinated population (n=37,373). The current vaccine strategy used in India includes a two-dose vaccine at an interval of one month. The initial series is followed by a booster at 6–9 months and subsequent boosters every 5 years.

TBE vaccines licensed in Europe and Russia are highly effective in protecting against TBE, and should also provide cross-protection against KFD, due to the antigenic cross-reactivity between these viruses (Fritz et al., 2012; Holbrook et al., 2004; Orlinger et al., 2011). However, early vaccination efforts with the RSSEV vaccine suggest that such antigenic similarity may not be not sufficient to provide protective immunity. The licensed vaccines could be tested in India, as they are well tolerated and provide protective immunity against TBEV for at least 5 years (Lehrer and Holbrook, 2009).

VIII. Summary

KFD is a historically understudied tick-borne disease that affects hundreds of people each year in India. Seroprevalence studies and the identification of the closely related AHFV in Saudi Arabia suggest that the geographic range of KFD-like viruses may be much broader than previously thought, raising the possibility that the transport of infected ticks by birds or in shipments of infected animals could introduce KFDV into new environments. Fortunately, deaths from KFD are relatively rare, and survivors recover completely, presumably developing life-long protective immunity. The recent outbreak in India should serve as a reminder that a number of arboviruses have presented significant health concerns for many years, yet little is known about them, and there are no therapeutic options for combating these diseases.

Highlights.

Kyasanur Forest disease (KFD), caused by a tick-borne flavivirus, is seen in a limited area of India.

The disease affects both wild primates and humans living near forested areas.

KFD is characterized by hemorrhagic fever, with a case fatality rate in the range of 1–3%.

Viruses related to KFDV have been identified in China and Saudi Arabia.

A formalin-inactivated vaccine is in use, but no effective therapies have been identified.

Examples of KFD cases.

The following summaries were adapted from published reports, as indicated. Case 1 is typical of the fatal hemorrhagic form of KFD, while Case 2 is a patient with neurologic signs and symptoms. Case 3 is a laboratory-acquired infection that provides an example of a biphasic febrile illness, with evidence of neurologic involvement.

Case 1 (Iyer et al., 1959)

A 55 year-old male villager who walked through the forest daily on the way to his fields became abruptly ill with fever, headache and back pain. Dead monkeys had been reported during the previous month, and a dead langur monkey was found at the edge of his village.

The fever continued, and on day 3 of illness he developed diarrhea with black stools, conjunctivitis and a productive cough with sputum, which did not contain blood. Two days later there was evidence of fresh blood in his stools, and he was admitted to hospital.

Physical examination revealed an afebrile but listless patient who was drowsy and appeared seriously ill. He complained of a persistent headache, and his speech was thick and slow. The superficial lymph nodes were not palpable. There were petechiae on the hard palate. Rhonchi and crepitations were heard over both lungs on auscultation. The cardiovascular system was normal. There was generalized tenderness on pressure over the abdomen, and the spleen was palpably enlarged. The neck was supple and mobile. The neurological examination was normal.

Examination of the blood on the day following hospital admission revealed 5200 leukocytes per mm3 with 82% granulocytes, 14% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes and 1% eosinophils. Lumbar puncture the next day brought showed clear fluid under moderate tension, which was normal by microscopic and chemical analysis.

Treatment consisted of supportive measures, with the administration of intravenous glucose in normal saline and vitamin K. The patient continued to pass tarry stools until day 7, when he became irrational and increasingly dyspneic. The heart rate increased to 132 bpm, and the radial pulse became imperceptible. Injections of coramine and hypertonic glucose in saline failed to arrest his rapid deterioration, and the patient expired.

At autopsy, blood-stained fluid was present in both pleural cavities, and there was patchy consolidation of both lungs, with hemorrhage in the right middle lobe. Microscopic examination showed extensive consolidation, with alveoli distended by a mixed exudate of erythrocytes, leukocytes and plasma. In some areas, the exudates consisted entirely of fresh blood. The bronchiolar epithelium appeared denuded, and there was an inflammatory infiltrate of the bronchiolar walls. The spleen was congested; microscopic examination showed depletion of malpighian follicles and marked prominence of the sinusoids. Reticulum cells were very prominent, with evidence of active erythrophagocytosis. Both kidneys were swollen, and on sectioning disclosed poor corticomedullary differentiation and discoloration of the pyramids. Areas of necrosis and degeneration were seen on microscopic examination. The lumen of the intestines contained a large quantity of blood. The brain showed a few petechial hemorrhages in the basis ponti, but was otherwise normal.

Case 2 (Webb and Rao, 1961)

A 55 year-old woman was hospitalized four days after the onset of illness, complaining of fever, myalgia, pain in the abdomen, dryness in the throat, vomiting and constipation. She had been in an area where dead monkeys were seen, and had been bitten by ticks. On examination, her temperature was 102°F, pulse 82/min, blood pressure 90/55. She appeared ill and dehydrated. She had conjunctival injection and generalized muscle tenderness. The blood pressure was at its lowest (80/50) on the 7th day, but by day 19 had risen to 120/85; the temperature returned to normal on day 8, but myalgia continued through day 12.

The patient was discharged free of symptoms on the 19th day after onset, but was readmitted on day 25, mentally alert, but complaining of severe headache and fever. Her temperature was 101°F; pulse 96, blood pressure 100/60. On physical examination, abnormalities were confined to the central nervous system. The right arm displayed cog-wheel rigidity, accompanied by a coarse tremor when voluntary movement was attempted. The other limbs were normal, and no sensory abnormalities were detected. The next day, she had a severe headache, but remained alert. Tremor now involved both arms and the right leg. Her headache was severe. Lumbar puncture revealed clear fluid, with 6 mononuclear cells/mm3 and 40 mg% protein. The next day, her temperature was still elevated, but she felt better, and the headache and limb tremors appear to be resolving. On day 29, her temperature was normal, but severe headache returned and continued for four more days. The patient’s condition gradually improved through day 47, when she was discharged, still experiencing bradycardia, low blood pressure and mild giddiness. One month later she was fit and had returned to work.

Case 3 (Wadia, 1975)

A 25-year-old technician at the Viral Research Centre accidentally broke a culture tube of KFDV, spilling it onto his hands. Three days later he developed body aches, joint pain and fever with rigors, and 6 days postexposure he was hospitalized with severe headache and back and body aches. Clinical examination revealed an obviously sick person with suffused conjunctivae. There was no neck rigidity or muscle weakness, but the reflexes were difficult to elicit, and the plantar reflex was extensor on the left. The WBC count was 5300 /mm3 with 61% polymorphs, 34% lymphocytes and 3% monocytes. A lumbar puncture was normal on the day of admission and when repeated 5 days later. An EEG was abnormal, with diffuse slow activity in all leads. A blood sample collected on the 1st day was inoculated into mice, which became sick on the 3rd day post-challenge, and KFDV was recovered. No virus was isolated from the CSF.

The patient continued to have body pain and headaches for the first 4 days of his hospital stay; he developed hemorrhagic patches on his back and a sore throat. His temperature returned to normal on day 7, and he was discharged on day 13, still complaining of weakness and abnormal taste. Five days later, he was readmitted, appearing severely ill, with a 2-day history of fever, headache and insomnia. The neurologic exam was normal, except that both plantar responses were extensor. A lumbar puncture on day 19 of illness (the 4th after the recurrence of fever) showed 95 cells per mm3, with 50% lymphocytes and 50% polymorphs; the protein was 25 mg%, chloride 700 mg% and sugar 65 mg%. The patient’s general symptoms improved rapidly, but the fever continued intermittently for 5 days, then resolved. After discharge, he complained of persistent fatigue for the first month, but eventually made a full recovery.

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the willingness of Dr. Sulochana of the Virus Diagnostic Laboratory, Shimoga, India to provide data on the recent incidence of Kyasanur Forest disease, and the assistance of Dr Sudhanshu Vrati, Dean of the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute in Gurgaon, India. He also thanks Dr. D. T. Mourya of the National Institute of Virology, Pune, India for his careful reading of the final manuscript, and Fabian de-Kok Mercado for preparing Figures 1 and 2.

MRH is an employee of the Battelle Memorial Institute under its prime contract with NIAID No. HHSN272200200016I. The information presented here is the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent views or policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services or the Battelle Memorial Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adhikari Prabha MR, Prabhu MG, Raghuveer CV, Bai M, Mala MA. Clinical study of 100 cases of Kyasanur Forest disease with clinical correlation. Indian J. Med. Sci. 1993;47:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani AG, Al Shaiban HM, Al Mazroa MA, Al-Hayani O, Macneil A, Rollin PE, Memish ZA. Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever in humans, Najran, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1882–1888. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aniker SP, Work TH, Chandrasekharaiya T, Murthy DP, Rodrigues FM, Ahmed R, Kulkarni KG, Rahman SH, Mansharamani H, Prasanna HA. The administration of formalin-inactivated RSSE virus vaccine in the Kyasanur Forest disease area of Shimoga District, Mysore State. Indian J Med Res. 1962;50:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Ocular manifestations of Kyasanur forest disease (a clinical study) Indian journal of ophthalmology. 1983;31:700–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Dandawate CN, Bhatt PN, Rao TR. Serological response in humans to a formolized Kyasanur Forest disease vaccine. Indian J Med Res. 1969;57:969–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat HR, Naik SV. Transmission of Kyasanur forest disease virus by Haemaphysalis wellingtoni Nuttall and Warburton, 1907 (Acarina :Ixodidae) Indian J Med Res. 1978;67:697–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat HR, Naik SV, Ilkal MA, Banerjee K. Transmission of Kyasanur Forest disease virus by Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides ticks. Acta Virol. 1978;22:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat HR, Sreenivasan MA, Goverdhan MK, Naik SV. Transmission of Kyasanur Forest Disease virus by Haemaphysalis kyasanurensis trapido Hoogstraal and Rajagopalan 1964 (Acarina: Ixodidae) Indian J Med Res. 1975;63:879–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt PN, Work TH, Varma MG, Trapido H, Murthy DP, Rodrigues FM. Kyasanur forest diseases. IV. Isolation of Kyasanur forest disease virus from infected humans and monkeys of Shimogadistrict, Mysore state. Indian J Med Sci. 1966;20:316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshell J. Kyasanur Forest disease: ecologic considerations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18:67–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshell J, Rajagopalan PK. Preliminary studies on experimental transmission of Kyasanur Forest disease virus by nymphs of Ixodes petauristae Warburton 1933, infected as larvae on Suncus murinus and Rattus blanfordi. Indian J Med Res. 1968;56:589–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carletti F, Castilletti C, Di Caro A, Capobianchi MR, Nisii C, Suter F, Rizzi M, Tebaldi A, Goglio A, Passerini Tosi C, Ippolito G. Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever in travelers returning from Egypt 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1979–1982. doi: 10.3201/eid1612101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrel RN, Fagbo S, Moureau G, Alqahtani MH, Temmam S, de Lamballerie X. Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus in Ornithodoros savignyi ticks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:153–155. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.061094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov MP. Results of the study made on Omsk hemorhagic fever (OH) by an expedition of the Institute of Neurology. Vestn Akad Med Navk SSR. 1948;2:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dandawate CN, Desai GB, Achar TR, Banerjee K. Field evaluation of formalin inactivated Kyasanur forest disease virus tissue culture vaccine in three districts of Karnataka state. Indian J Med Res. 1994;99:152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MM, Williams H, Macleod JA. Louping ill in man: a forgotten disease. J Infect. 1991;23:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(91)92756-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd KA, Bird BH, Khristova ML, Albarino CG, Carroll SA, Comer JA, Erickson BR, Rollin PE, Nichol ST. Ancient ancestry of KFDV and AHFV revealed by complete genome analyses of viruses isolated from ticks and mammalian hosts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz R, Orlinger KK, Hofmeister Y, Janecki K, Traweger A, Perez-Burgos L, Barrett PN, Kreil TR. Quantitative comparison of the cross-protection induced by tick-borne encephalitis virus vaccines based on European and Far Eastern virus subtypes. Vaccine. 2012;30:1165–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverdhan MK, Rajagopalan PK, Narasimha Murthy DP, Upadhyaya S, Boshell MJ, Trapido H, Ramachandra Rao T. Epizootiology of Kyasanur Forest Disease in wild monkeys of Shimoga district, Mysore State (1957–1964) Indian J Med Res. 1974;62:497–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ, Kuno G, Markoff L. Flaviviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1153–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook MR, Shope RE, Barrett A. Use of recombinant E protein domain III-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for differentiation of tick-borne encephalitis serocomplex flaviviruses from mosquito-borne flaviviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:4101–4110. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4101-4110.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer CG, Laxmana Rao R, Work TH, Narasimha Murthy DP. Kyasanur Forest Disease VI. Pathological findings in three fatal human cases of Kyasanur Forest Disease. Indian J Med Sci. 1959;13:1011–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon RH, Rippy MK, McKee KT, Jr, Zack PM, Peters CJ. Infection of Macaca radiata with viruses of the tick-borne encephalitis group. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:399–409. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSala PR, Holbrook MR. Tick-borne Flaviviruses. In: AW,P,J,S,A,W, editor. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2010. pp. 221–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer AT, Holbrook MR. Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines. In: Barrett ADT, Stanberry LR, editors. Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. London: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 713–718. [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Li L, Dick D, Shope RE, Feldmann H, Barrett ADT, Holbrook MR. Analysis of the complete genome of the tick-borne flavivirus Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus. Virology. 2003;313:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani TA. Alkhumra virus infection, a new viral hemorrhagic fever in Saudi Arabia. J Infect. 2005;51:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madani TA, Azhar EI, Abuelzein el TM, Kao M, Al-Bar HM, Abu-Araki H, Niedrig M, Ksiazek TG. Alkhumra (Alkhurma) virus outbreak in Najran, Saudi Arabia: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics. J Infect. 2011;62:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi M, Erickson BR, Comer JA, Nichol ST, Rollin PE, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Kyasanur Forest Disease virus Alkhurma subtype in ticks, Najran Province, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:945–947. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansharamani HJ, Dandawate CN. Experimental vaccine against Kyasanur Forest disease (KFD) virus from tissue culture source. II. Safety testing of the vaccine in cortisone sensitized Swiss albino mice. Indian J Pathol Bacteriol. 1967;10:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehla R, Kumar SR, Yadav P, Barde PV, Yergolkar PN, Erickson BR, Carroll SA, Mishra AC, Nichol ST, Mourya DT. Recent ancestry of Kyasanur Forest disease virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1431–1437. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.080759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish ZA, Albarrak A, Almazroa MA, Al-Omar I, Alhakeem R, Assiri A, Fagbo S, MacNeil A, Rollin PE, Abdullah N, Stephens G. Seroprevalence of Alkhurma and other hemorrhagic fever viruses, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:2316–2318. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Mehla R, Barde PV, Yergolkar PN, Kumar SRP, Thakarea IP, Mishra AC. Diagnosis of Kyasanur Forest diseae by nested RT-PCR, real-time RT-PCR and IgM capture ELISA. J. Virol. Methods. 2012;186:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayar M. Histological changes in mice infected with Kyasanur Forest disease virus. Indian J Med Res. 1972;60:1421–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlinger KK, Hofmeister Y, Fritz R, Holzer GW, Falkner FG, Unger B, Loew-Baselli A, Poellabauer EM, Ehrlich HJ, Barrett PN, Kreil TR. A tickborne encephalitis virus vaccine based on the European prototype strain induces broadly reactive cross-neutralizing antibodies in humans. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1556–1564. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padbidri VS, Wairagkar NS, Joshi GD, Umarani UB, Risbud AR, Gaikwad DL, Bedekar SS, Divekar AD, Rodrigues FM. A serological survey of arboviral diseases among the human population of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33:794–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattnaik P. Kyasanur forest disease: an epidemiological view in India. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:151–165. doi: 10.1002/rmv.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavri K. Clinical, clinicopathologic, and hematologic features of Kyasanur forest disease. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1989;11:S854–S859. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_4.s854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavri KM, Gokhale T, Shah KV. Serological response to Russian springsummer encephalitis virus vaccine as measured with Kyasanur Forest disease virus. Indian J Med Res. 1962;50:153–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan PK, Patil AP, Boshell J. Ixodid ticks on their mammalian hosts in the Kyasanur Forest disease area of Mysore State, India, 1961–64. Indian J Med Res. 1968a;56:510–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan PK, Patil AP, Boshell J. Studies on Ixodid tick populations on the forest floor in the Kyasanur Forest disease area. (1961–1964) Indian J Med Res. 1968b;56:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph SE. Transmission of tick-borne pathogens between co-feeding ticks: Milan Labuda's enduring paradigm. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanini P, Hasu E, Huhtamo E, Crobu MG, Ilaria V, Brustia D, Salerno AM, Vapalahti O. Rhabdomyolysis and severe muscular weakness in a traveler diagnosed with Alkhurma hemorrhagic fever virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:254–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers TM, Schwentker FF. Louping Ill in Man. J Exp Med. 1934;59:669–685. doi: 10.1084/jem.59.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek D, Yakimenko VV, Karan LS, Tkachev SE. Omsk haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2010;376:2104–2113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar JK, Chatterjee SN. Survey of antibodies against arthropod-borne viruses in the human sera collected from Calcutta and other areas of West Bengal. Indian J Med Res. 1962;50:833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah KV, Aniker SP, Murthy DP, Rodrigues FM, Jayadeviah MS, Prasanna HA. Evaluation of the field experience with formalin-inactivated mouse brain vaccine of Russian spring-summer encephalitis virus against Kyasanur Forest disease. Indian J Med Res. 1962;50:162–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KR, Bhatt PN. Transmission of Kyasanur Forest disease virus by Hyalomma marginatum isaaci. Indian J Med Res. 1968;56:610–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KR, Goverdhan MK, Rao TR. Experimental transmission of Kyasanur forest disease virus to small mammals by Ixodes petauristae, I. ceylonensis and Haemaphysalis spinigera. Indian J Med Res. 1968;56:594–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KR, Pavri K, Anderson CR. Experimental Transovarial Transmission of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus in Haemaphysalis spinigera. Nature. 1963;199:513. doi: 10.1038/199513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KR, Pavri KM, Anderson CR. Transmission of Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus by Haemaphysalis turturis Haemaphysalis papuana kinneari and Haemaphysalis minuta. Indian J Med Res. 1964;52:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithburn KC, Kerr JA, Gatne PB. Neutralizing antibodies against certain viruses in the sera of residents of India. J Immunol. 1954;72:248–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasan MA, Bhat HR, Rajagopalan PK. The epizootics of Kyasanur Forest disease in wild monkeys during 1964 to 1973. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:810–814. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapido H, Rajagopalan PK, Work TH, Varma MG. Kyasanur Forest disease. VIII. Isolation of Kyasanur Forest disease virus from naturally infected ticks of the genus Haemaphysalis. Indian J Med Res. 1959;47:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya S, Dandawate CN, Banerjee K. Surveillance of formolized KFD virus vaccine administration in Sagar-Sorab talukas of Shimoga district. Indian J Med Res. 1979;69:714–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma MG, Webb HE, Pavri KM. Studies on the transmission of Kyasanur Forest disease virus by Haemaphysalis spinigera newman. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1960;54:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(60)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadia RS. Neurological involvement in Kyasanur Forest Disease. Neurol India. 1975;23:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang H, Fu S, Wang H, Ni D, Nasci R, Tang Q, Liang G. Isolation of kyasanur forest disease virus from febrile patient, yunnan, china. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:326–328. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb HE, Burston J. Clinical and pathological observations with special reference to the nervous system in Macaca radiata infected with Kyasanur Forest Disease virus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1966;60:325–331. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(66)90296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb HE, Chaterjea JB. Clinico-pathological observations on monkeys infected with Kyasanur Forest disease virus, with special reference to the haemopoietic system. Br J Haematol. 1962;8:401–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1962.tb06544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb HE, Rao RL. Kyasanur forest disease: a general clinical study in which some cases with neurological complications were observed. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1961;55:284–298. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(61)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work T. Russian spring-summer encephalitis virus in India. Kyasanur Forest disease. Prog. Med. Virol. 1958;1:248–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work TH, Trapido H. Summary of preliminary report of investigations of the virus research centre on an epidemic disease affecting forest villagers and wild monkeys in Shimoga district, Mysore. Indian J. Med. Sci. 1957;11:340–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work TH, Trapido H, Narashima Murthy DP, Laxmana Rao R, Bhatt PN, Kulkarni KG. Kyasanur Forest Disease III: A preliminary report on the nature of the infection and clinical manifestations in human beings. Indian J Med Sci. 1957;11:619–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki AM. Isolation of a flavivirus related to the tick-borne encephalitis complex from human cases in Saudi Arabia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:179–181. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]