Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of resveratrol on growth and function of granulosa cells. Previously, we have demonstrated that resveratrol exerts profound pro-apoptotic effects on theca-interstitial cells.

Design

In vitro study.

Setting

Research laboratory.

Animal(s)

Immature Sprague-Dawley female rats.

Intervention(s)

Granulosa cells were cultured in the absence or presence of resveratrol.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

DNA synthesis was determined by thymidine incorporation assay; apoptosis by activity of caspases 3/7, cell morphology by immunocytochemistry, steroidogenesis by mass spectrometry, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression by PCR and Western blots.

Result(s)

Resveratrol induced a biphasic effect on DNA synthesis, whereby a lower concentration stimulated thymidine incorporation, and higher concentrations inhibited it. Additionally, resveratrol slightly increased the cell number and modestly decreased the activity of caspases 3/7 with no effect on cell morphology or progesterone production. However, resveratrol decreased aromatization and VEGF expression, whereas AMH expression remained unaltered.

Conclusion(s)

Resveratrol, by exerting cytostatic but not cytotoxic effects together with antiangiogenic actions mediated by decreased VEGF in granulosa cells, may alter the ratio of theca-to-granulosa cells and decrease vascular permeability, and hence be of potential therapeutic use in conditions associated with highly vascularized theca-interstitial hyperplasia and abnormal angiogenesis, such as those seen in women with PCOS.

Keywords: Apoptosis, granulosa cells, proliferation, resveratrol, steroidogenesis, AMH, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) is a natural polyphenol synthesized by several plants as a phytoalexin when under attack by pathogens such as bacteria or fungi. This bioflavonoid is naturally found in mulberries, peanuts, several species of medicinal plants and is present in the skin of grapes and thus in red wine (1). Resveratrol possesses a broad spectrum of pharmacological and therapeutic properties such as anti-carcinogenic, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory, as well as cardioprotective and neuroprotective effects (2–5). In several cancer cell lines and primary cell culture systems, resveratrol has been shown to exert anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties (6, 7). However, little is known regarding the role of resveratrol in such vital biological functions as reproduction and ovarian function.

Recently, we have demonstrated that resveratrol inhibits ovarian theca-interstitial cell growth by decreasing DNA synthesis and inducing pro-apoptotic effects as evidenced by an increase in activity of executioner caspases 3 and 7, DNA fragmentation and the presence of morphological changes consistent with apoptosis (7). Furthermore, we have shown that a resveratrol-induced suppressive effect on theca cell proliferation was partly abrogated by the addition of mevalonic acid, farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, indicating a role of the mevalonate pathway in resveratrol-induced inhibition of theca-interstitial cell growth (8). These effects may be relevant to potential use of this compound in treatment of clinically important conditions associated with ovarian theca-interstitial hyperplasia such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age, affecting 6.6–8% of women in this age group (9). It is characterized by enlarged ovaries, highly vascularized stroma, leading to increased androgen production and disrupted folliculogenesis contributing to infertility (10). Granulosa cells are involved in key physiological processes such as follicle growth, steroidogenesis and angiogenesis (11). Previously, it has been shown that granulosa cells from subjects with PCOS are characterized by reduced apoptotic activity and increased cell proliferation (12). Additionally, granulosa cells from women with PCOS respond to FSH stimulation by producing more estradiol than normal granulosa cells, indicating that the inherent capacity of these cells to respond to FSH is retained (13). In polycystic ovaries, an increase in anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) output by granulosa cells from preantral and small antral follicles has been reported, and this observation may be due to aberrant activity of the granulosa cells in PCOS patients (14–16). Finally, increased serum levels and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in polycystic ovaries has been associated with increased ovarian stromal blood flow and may contribute to the loss of intraovarian autoregulatory mechanisms (10).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the biological effects of resveratrol on granulosa cells, in comparison to our previous work on theca cells. To this end, we studied actions of resveratrol on granulosa cell proliferation, apoptosis, steroidogenesis and expression of AMH and VEGF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Reagents

The collection and purification of ovarian granulosa cells were performed as described previously (17). The cells were counted, and viability, as assessed by the trypan blue exclusion test, was routinely in the 40%–45% range, comparable to findings of others (18, 19). The granulosa cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated plates for up to 48 h at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in humidified air in serum-free McCoy’s 5A culture medium supplemented with 1% antibiotic/antimycotic mix, 0.1% BSA and 2mM L-glutamine. The cells were incubated without (control) or with resveratrol (10–50 μM) and supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml). In the experiments evaluating steroidogenesis, testosterone (0.5 μM) was added to serve as a substrate for aromatase. The doses of resveratrol were selected based on our previous studies evaluating rat theca-interstitial cell proliferation (7, 8). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) except for ovine FSH, which was obtained from the National Hormone & Pituitary Program at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Torrance, CA). All treatments and procedures were carried out in accordance with accepted standards of human animal care as outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Davis.

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were incubated for 24 and 48 h in 96-well fibronectin-coated plates at a density of 35,000 cells/well. DNA synthesis was determined through a thymidine incorporation assay. Radiolabeled [3H] thymidine (1 μCi/well) was added to the cells 24 h before the culture was stopped. Subsequently, the cells were harvested with a multiwell cell harvester (PHD Harvester; Cambridge Technology, Inc., Watertown, MA) and radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter, Wallac 1409 (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT).

Cell viability assays

The total number of viable cells was estimated using a CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) two hours before the end of the culture period. Cells were incubated for 24 and 48 h in 96-well fibronectin-coated plates at a density of 35,000 cells/well. Fluorescence was determined with the use of a microplate reader (Fluostar Omega, BMG, Durham, NC). To validate the assay, a standard curve with a known number of cells was generated and a linear correlation was verified (r2 = 0.99, P<0.001).

Caspase-3/7 activity assay

The measurement of apoptosis in granulosa cells was performed using the Apo-ONE® Homogeneous Caspase-3/7 Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated in 96-well fibronectin-coated plates at a density of 20,000 cells/well at different time points (3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h). Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using a microplate reader (Fluostar Omega, BMG Lab Technologies, Durham, NC) at excitation wavelength 485 nm and emission wavelength 520 nm. Caspase-3/7 activity was expressed per number of total viable cells.

DAPI nuclear and F-actin staining

Approximately 16,000 granulosa cells/well were seeded in duplicate in 8-well culture slides (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) at different time points (24–48 h) and then subjected to DAPI and F-actin staining as previously described (20). Slides were examined under an Olympus BX61 fluorescent microscope at 40 X magnification (Olympus America, Melville, NY).

Total RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Cells were seeded in 24-well fibronectin-coated plates at a density of 400,000 cells/well and incubated for 24–48 h. RNA was isolated using the MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the KingFisher robot (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). Reverse transcription of total RNA to cDNA was performed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit for rt-PCR (Applied Biosystems, CA). PCR reactions were set up in 28-μl volumes, consisting of 5 μl cDNA, 4.5 μl forward and 4.5 μl reverse 900 nM primers and 14 μl of 2X SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems).

Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using the ABI 7300 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed using SDS 1.4 software (Applied Biosystems). The relative amount of target mRNA was expressed as a ratio normalized to hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT). The primer sequences were as follows: rat CYP19 forward (5′-ACC ATC ATG GTC CCG GAA A-3′) and reverse (5′-AGG CCC ATG ATC AGC AGA AG-3′); rat AMH forward (5′-GCT GCT GCT AGC GAC TAT G-3′) and reverse (5′-AGA TGT AGG CTA GCA ACT G-3′); rat VEGF forward (5′-ACA GAA GGG GAG CAG AAA GCC CAT-3′) and reverse (5′-CGC TCT GAC CAA GGC TCA CAG T-3′); rat HPRT forward (5′-TTG TTG GAT ATG CCC TTG ACT-3′) and reverse (5′-CCG CTG TCT TTT AGG CTT TG-3′). Since SYBR Green detects double stranded DNA including primer dimers, contaminating DNA, and PCR product from misannealed primer, a dissociation curve was run. By viewing a dissociation curve, we ensured that the desired amplicon was detected.

Mass Spectrometry

Quantitation of steroids was performed using a novel Turbulent Flow Chromatography (TFC) HPLC-MS/MS method that allowed the simultaneous detection of progesterone and estradiol. The method has been described in detail previously (21). Briefly, quantitation was done using selective reaction monitoring (SRM) mode to monitor protonated precursor → product ion transition of m/z 315.2 → 97.1 for progesterone, 255.2 → 158.6 for estradiol. The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) for progesterone were 50 and 125 pg/mL and estradiol 100 and 250 pg/mL.

Intra-assay accuracy and precision were determined at concentrations of 400 and 800 pg/mL. Accuracy of the progesterone and estradiol analysis were within 5.3 ± 0.9% and 7.5 ± 1.1%, respectively, and precision was within 103 ± 2.5% and 101 ± 1.0% of the nominal value.

Western blot analysis

Cells were cultured for 48 h and at the end of treatments, cell lysates were prepared as previously described (22). Protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). For immunoblot analysis, 50 μg of protein was resolved in 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. Blots were blocked using blocking buffer (LI-COR Biosciences), incubated with primary antibodies to AMH (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), VEGF (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and β-actin (1:40,000; Sigma Aldrich), washed and incubated with the secondary antibodies: donkey anti-goat (1:5,000; LI-COR Biosciences) and donkey anti-mouse (1:40,000; LI-COR Biosciences). Target proteins were detected with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) and band intensities normalized to β-actin.

Activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase

The assay evaluating activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR) was performed as described previously (8). Briefly, the microsomal fraction of granulosa cells was isolated and the conversion of [3-14C]-HMG-CoA to [14C]-mevalonic acid and lactone was determined.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 9.0 software (SAS, Cary, NC). Data are presented as the mean ±SEM. Means were compared by analysis of variance followed by post-hoc testing using Tukey’s HSD Test or Dunnet Test. When appropriate, data were logarithmically transformed. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

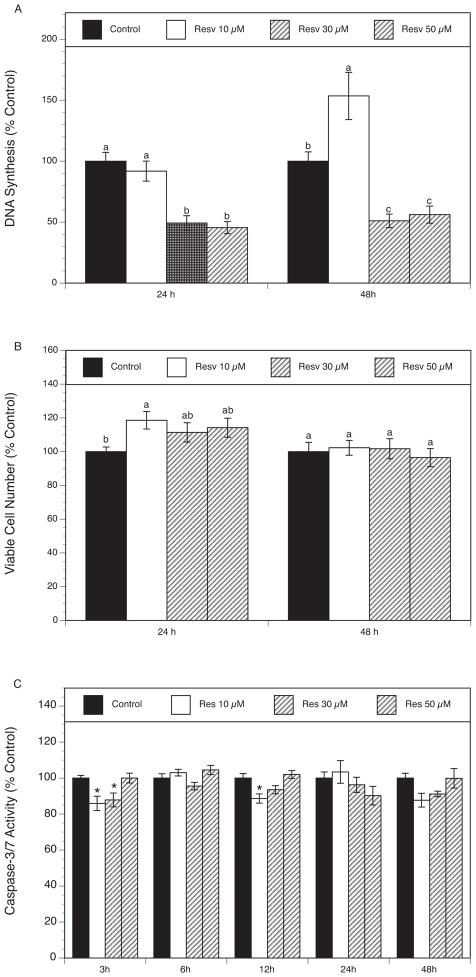

Effects of resveratrol on DNA synthesis

To determine whether resveratrol affects DNA synthesis, rat granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in the absence or presence of increasing doses of resveratrol (10–50 μM). As shown in Figure 1A, exposure to resveratrol ranging from 30–50 μM induced a significant inhibitory effect on DNA synthesis at 24 h, by up to 55 % (P <0.001) at the highest concentration. However, at 48 h, resveratrol displayed a biphasic action, whereby a lower concentration of resveratrol (10 μM) stimulated thymidine incorporation by 54% (P <0.01), whereas higher concentrations (30 and 50 μM) decreased it, respectively, by 49% (P <0.05) and 44% (P <0.05).

Fig. 1.

(A) Effect of resveratrol (10–50 μM) on proliferation. Granulosa cells were cultured in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) for 24 and 48 h in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Proliferation was evaluated by determination of DNA synthesis (by thymidine incorporation). Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from two independent experiments (each with N=8). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(B) Effect of resveratrol (10–50 μM) on cell viability. Granulosa cells were cultured in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) for 24 and 48 h in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Cell viability was evaluated by estimation of the number of viable cells using MTS assay. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from two independent experiments (each with N=8). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(C) Effect of resveratrol (10–50 μM) on activity of executioner caspases 3 and 7. Granulosa cells were cultured in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) for 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Caspase-3/7 activity was determined using Apo-ONE Homogeneous Caspase-3/7 Assay. Caspase activity was calculated per number of viable cells (determined by MTS assay). Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=8); * denotes means significantly different from control (P <0.05).

Effects of resveratrol on cell viability

To investigate the effect of resveratrol on cell viability, the MTS assay was performed after treatment of granulosa cells with or without various concentrations of resveratrol (10–50 μM) for 24 and 48 h. As presented in Figure 1B, resveratrol had no significant effect on the number of viable cells at either time point, except for a modest increase by 19% (P <0.04) induced by 10 μM resveratrol at 24 h.

Effects of resveratrol on caspase activation

To determine whether apoptosis has any role in the inhibitory effect of resveratrol on the growth of granulosa cells, caspases 3/7 activity was measured in the absence or in the presence of resveratrol (10–50 μM) at various time points (3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h). These experiments included early time points to account for possible early actions of resveratrol that may have cumulative long-term effects on ultimate end-points such as the number of viable cells. As can be seen in Figure 1C, resveratrol at the lower concentration (10 μM) modestly protected granulosa cells from caspases 3/7 activation at the time points of 3 and 12 h, respectively, by 14% (P< 0.05) and 11% (P< 0.01). The caspases inhibition was no longer evident after 24 or 48 h of exposure to resveratrol.

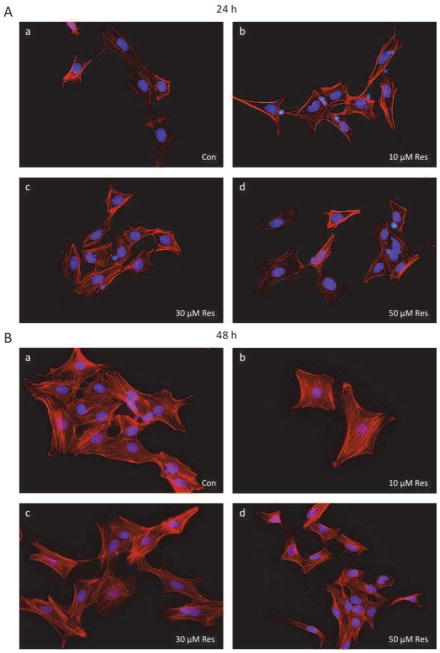

Effects of resveratrol on cell morphology

The effects of resveratrol on the nuclear morphology and cytoskeleton of granulosa cells are presented in Figure 2. In the apoptotic process, the cell undergoes disassembly, which is characterized by cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing, and lack of preservation of organelle ultrastructural integrity (23, 24). As illustrated in Figure 2, after 24 and 48-h exposure to increasing doses of resveratrol (10–50 μM), the shape of the granulosa cells appeared unaltered, with large oval-shaped nuclei and well organized F-actin fibers.

Fig 2.

Effect of resveratrol (10–50 μM) on cell morphology. Granulosa cells were cultured for 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol, then fixed, stained and visualized under a fluorescent microscope (40x magnification) as described in Material and Methods. Nuclear staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and F-actin was used to observe morphological changes. Control (a), Resveratrol 10 μM (b), Resveratrol 30 μM (c), Resveratrol 50 μM (d).

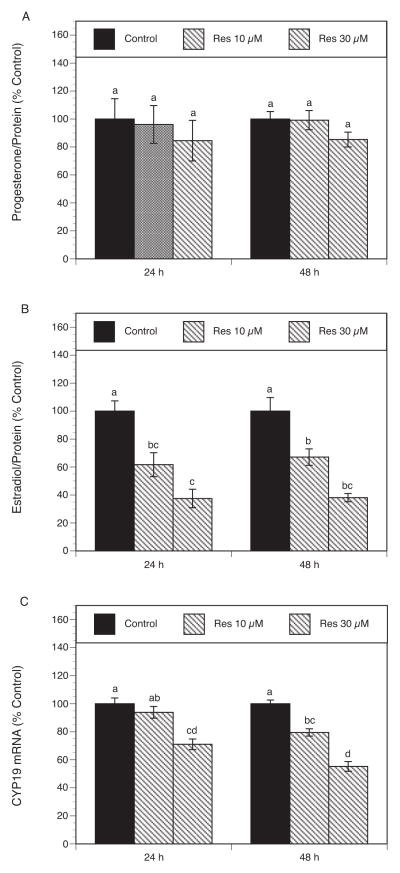

Effects of resveratrol on steroidogenesis

To determine the effect of resveratrol on steroid production, granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in the absence and the presence of resveratrol (10–30 μM). To account for resveratrol-related effects on the cell number, the production of steroids was expressed as percentage control per unit of protein content in individual cultures. As presented in Figure 3A, resveratrol had no significant effect on progesterone levels at any of the tested concentrations and time points. However, resveratrol induced a dose-dependent decrease in estradiol levels at both time points: resveratrol (10–30 μM) induced a significant inhibitory effect on estradiol production, respectively, by 38% (P <0.001) and 62% (P <0.001) at 24 h and by 33% (P <0.05) and 63 % (P <0.001) at 48 h (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Effect of resveratrol (10–30 μM) on progesterone (A) and estradiol (B) production. Granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Progesterone and estrogen levels were determined using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=4). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(C) Effect of resveratrol on CYP19 mRNA expression. Granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and mRNA expression was determined using quantitative real-time PCR reactions and normalized to HPRT mRNA levels. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=4). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

To evaluate the effect of resveratrol on aromatase mRNA expression in the same set of experiments, quantitative rt-PCR reactions were performed. Aromatase cytochrome P450 (encoded by the CYP19 gene) is the key enzyme required for the biosynthesis of estrogens from C19-steroid precursors and is expressed in granulosa cells (25). As shown in Figure 3C, resveratrol induced a concentration-dependent decrease in CYP19 mRNA expression. After 48 h incubation, resveratrol at both tested concentrations significantly decreased CYP19 transcripts, respectively, by 20% (P <0.05) and 45% (P <0.001).

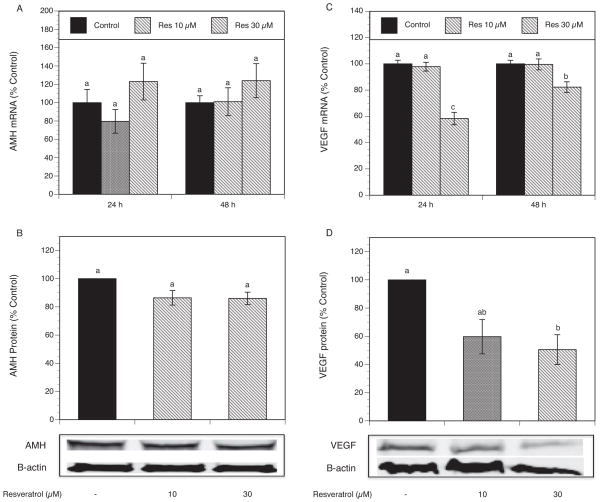

Effects of resveratrol on AMH mRNA and protein expression

Because AMH plays a significant role in controlling the gonadotropin-independent stages of ovarian follicle development, further experiments were carried out in order to determine whether resveratrol (10–30 μM) exerts any effect on AMH mRNA expression by granulosa cells at 24 and 48 h. As shown in Figure 4A, resveratrol had no significant effect on AMH mRNA levels at any of the tested concentrations.

Fig. 4.

(A) Effect of resveratrol (10–30 μM) on AMH mRNA expression. Granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and mRNA expression was determined using quantitative real-time PCR reactions and normalized to HPRT mRNA levels. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=4). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(B) Effect of resveratrol (10–30 μM) on AMH protein expression. Granulosa cells were cultured for 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. AMH protein level was determined by Western blot analysis and normalized to β-actin. One of three representative blots is shown. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=1). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(C) Effect of resveratrol (10–30 μM) on VEGF mRNA expression. Granulosa cells were cultured for 24 and 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. Total cellular RNA was isolated, and mRNA expression was determined using quantitative real-time PCR reactions and normalized to HPRT mRNA levels. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=4). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

(D) Effect of resveratrol (10–30 μM) on VEGF protein expression. Granulosa cells were cultured for 48 h in chemically defined media supplemented with FSH (30 ng/ml) and testosterone (0.5 μM) in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol. VEGF protein level was determined by Western blot analysis and normalized to β-actin. One of three representative blots is shown. Results are presented as a percentage of control. Each bar represents mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (each with N=1). Means with no superscripts in common are significantly different (P <0.05).

To examine whether the absence of changes in AMH mRNA expression induced by resveratrol was reflected at the protein level, the cells were treated without (control) or with resveratrol (10–30 μM) for 48 h. As presented in Figure 4B, no changes in AMH protein expression were observed after resveratrol treatment.

Effects of resveratrol on VEGF mRNA and protein expression

Since vascular VEGF is a key pro-angiogenic factor involved in the regulation of follicle growth and development of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), quantitative rt-PCR reactions were performed to evaluate whether resveratrol (10–30 μM) has any effect on VEGF mRNA expression after 24 and 48 h incubation. As shown in Fig 4C, resveratrol 30 μM significantly decreased VEGF mRNA expression at 24 and 48 h, respectively, by 42% (P <0.001) and 18% (P <0.05).

To evaluate whether the resveratrol-induced decrease in VEGF mRNA levels correlates with a reduction in protein expression, the cells were cultured with or without resveratrol (10–30 μM) for 48 h. As presented in Fig 4D, Western blot analysis showed that resveratrol 30 μM decreased VEGF protein expression by 49% (P <0.03) compared to control.

Effects of resveratrol on HMGCR activity

In a previous study on theca cells, we observed that resveratrol inhibited HMGCR activity (8). Since HMGCR may affect growth and function of cells, we studied HMGCR activity in granulosa cells in the absence (control) or in the presence of resveratrol at 30 and 50 μM or simvastatin (1 μM; positive control). Simvastatin significantly reduced HMGCR activity by 41% (P<0.001); however, resveratrol had no effect (HMGCR activity being at 110±3 and 100±1% of control, respectively, for resveratrol at 30 and 50 μM).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have demonstrated that in cultures of granulosa cells, resveratrol exerts effects greatly differing from its pro-apoptotic actions on theca-interstitial cells (7). Specifically, in granulosa cells resveratrol: a) induces a biphasic effect on DNA synthesis, whereby a lower concentration stimulates thymidine incorporation and higher concentrations decrease it; b) slightly increases the number of viable cells; c) modestly decreases early caspase activation, and does not affect cell morphology; d) does not alter progesterone levels but decreases estrogen production and aromatase mRNA expression in a concentration-dependent fashion; e) has no effect on AMH expression; f) decreases VEGF mRNA and protein expression; and g) does not affect HMGCR activity.

Over the past decade, resveratrol has emerged as a prominent chemopreventive agent that interferes with signaling pathways regulating cell proliferation and survival (26). Indeed, this bioflavonoid has been shown to inhibit cell growth of different primary (7, 27, 28) and human cancer cell lines (29–31). The underlying mechanisms of resveratrol-induced inhibition of cell proliferation may be due to its ability to inhibit both ribonucleotide reductase and DNA polymerase activities (32, 33), two key enzymes involved in DNA synthesis, leading to cell growth inhibition at the S/G2 phase transition of the cell cycle (34, 35). However, the effects of resveratrol on cell growth are not universally inhibitory and vary depending on the concentration, duration of the treatment and the cell type. In the present study, resveratrol exerted an inhibitory effect on granulosa cell DNA synthesis at 24 h, however, when treatment exposure was extended to 48 h, we observed a biphasic effect of resveratrol on DNA synthesis: at 10 μM resveratrol increased thymidine incorporation but reduced it at higher concentrations. A comparable biphasic effect of resveratrol on cell proliferation has been previously reported in LNCaP cells (36), whereby low concentrations of resveratrol (5–10 μM) stimulated and high concentrations (15–30 μM) inhibited DNA synthesis. It has been suggested that this late increase in thymidine incorporation may be due to the cells entering the S phase of the cell cycle involving signaling pathways that act over several hours (36). This resveratrol-induced biphasic effect on rat granulosa cell growth contrasts with our previous observations in rat theca-interstitial cells, whereby resveratrol showed a potent dose-dependent inhibitory effect on cell growth after 48 h (7). Moreover, in the same study, resveratrol also decreased the number of viable theca cells, in contrast with the modest increase in granulosa cell viability observed in the present work. Taken together, these findings suggest that resveratrol has distinctly different effects on proliferation of cells in the theca and granulosa compartments.

Apoptosis or programmed cell death occurs in several physiological and pathological situations (37). Typical apoptosis consists of four events at the execution stage: caspase activation, internucleosomal DNA cleavage, chromatin condensation, and apoptotic formation (38). In the present study, we observed a modest decrease in caspase-3/7 activity and an absence of morphological changes consistent with apoptosis, suggesting that resveratrol not only does not induce apoptosis but may even protect rat granulosa cells from apoptosis. Previous studies have reported contradictory results regarding the role of resveratrol in apoptosis: resveratrol has been shown to prevent apoptosis in several cell types, including rat embryonic cells and human erythroleukemia K562 cells (39, 40), whereas a pro-apoptotic effect of resveratrol has been demonstrated in both primary and cancer cell lines (7, 41, 42). Interestingly, divergent effects of resveratrol on apoptosis may occur in different cell types within the same organ. In the ovary, our previous in vitro study demonstrated that resveratrol increases the activity of executioner caspases 3 and 7, increases DNA fragmentation and induces progressive concentration- and time-dependent morphological changes in rat theca-interstitial cells (7). In contrast, the present study shows that resveratrol has a minimal effect on granulosa cell apoptosis. Since resveratrol exerts different effects on apoptosis in two cellular compartments of the follicle, it is likely that it may alter the balance between the relative number of theca and granulosa cells.

Proper regulation of apoptosis and proliferation is essential to sustain tissue homeostasis. In light of the present findings, one may speculate that the overall anti-proliferative effect of resveratrol on granulosa cells is not related to its pro-apoptotic properties, suggesting that resveratrol affects granulosa cell growth by exerting mainly cytostatic, but not cytotoxic effects. This observation may be of relevance to ovarian folliculogenesis, whereby the bidirectional crosstalk between the oocyte and its surrounding granulosa cells (both cumulus and mural) is crucial for normal follicle development (43–45).

According to the two-cell-two-gonadotropin theory, FSH is responsible for estrogen production in granulosa cells by aromatization of androgens synthesized in theca cells (46). In the present study, resveratrol had no effect on progesterone levels and induced a concentration-dependent decrease in estradiol production and aromatase mRNA expression in granulosa cells. This finding is in agreement with previous studies, whereby resveratrol induced an inhibitory effect on aromatase gene expression and activity in placental cells (47), breast cancer cells (48) and in human granulosa-luteal cells (49). Although the underlying mechanisms of resveratrol-induced inhibition of aromatase is still poorly understood, it has been suggested that both binding to estrogen receptors and/or a modulation of cell signaling pathways may be involved (50). This resveratrol-induced inhibitory effect on aromatization is in sharp contrast with a previous study, whereby stimulation of steroidogenesis by a hydroxylated resveratrol analog was shown in a swine granulosa cell model (51). These marked discrepancies on granulosa cell steroidogenesis between the parent compound and the hydroxylated resveratrol analog may be due to the fact that the hydroxyl group could act at a proximal point of the steroid biosynthetic pathway, thus stimulating both progesterone and estradiol production.

AMH, a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family, was identified as a factor that causes regression of the Müllerian ducts during male fetal development (52). In females, AMH is produced by granulosa cells of ovarian follicles and acts as a marker of granulosa cell differentiation. AMH mRNA expression has been detected in granulosa cells of primary follicles immediately after their formation in neonatal rats and mice, as well as in granulosa cells of all secondary preantral stage follicles and small antral follicles. AMH starts to diminish during further folliculogenesis from the small antral follicle stage onwards (53). In the present study, resveratrol had no effect on either AMH mRNA or protein expression in granulosa cells, suggesting that it did not induce differentiation/maturation of these cells.

VEGF, a potent angiogenic mitogen, is an important mediator during the normal ovarian cycle and has been shown to increase the permeability of blood vessels (54). In addition, VEGF has been shown to play a prominent role in the pathophysiology of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), a condition frequently associated with polycystic ovaries, whereby VEGF mediates increased vascular permeability and endothelial migration at least partly through modulation of vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin function (55). In the present study, resveratrol decreased both VEGF mRNA and protein expression in granulosa cells. Similarly, a resveratrol-induced decrease in VEGF expression has been demonstrated in several human cancer cell lines (56–58). Additionally, Basini et al. demonstrated that the treatment of swine granulosa cells with two resveratrol analogs, hydroxylated and methylated forms, also decreased VEGF output (51). These observations may be relevant to the treatment of several gynecological disorders, as abnormalities in ovarian angiogenesis contribute to OHSS seen in women with PCOS, to disorders of ovulation, to subfertility and to endometriosis.

The most interesting findings of this study pertain to the inhibitory effects of resveratrol on production of estrogen and VEGF by isolated granulosa cells. An important next logical step will be to evaluate actions of resveratrol in vivo, in particular on steroidogenesis, as well as to study effects of resveratrol on animal models of OHSS. One may hypothesize that administration of resveratrol in vivo may reduce aromatization and improve OHSS. However, it is also possible that resveratrol may have adverse effects on folliculogenesis; hence, an enthusiasm for potential therapeutic value of resveratrol needs to be tempered until in vivo studies are completed.

Keeping in mind the above cautionary comments, it is possible that the present findings may have clinical relevance to conditions associated with highly vascularized ovaries, with thecal hyperplasia, and altered growth and function of granulosa cells, such as seen in PCOS. Previously, an increase of granulosa cell proliferation has been shown in early-growing follicles in both anovulatory and ovulatory PCOS patients (12, 59). In addition, differences in the rate of cell death and proliferation in granulosa cell populations have been reported in PCOS (12). Thus, we speculate that resveratrol may alter the ratio of theca-to-granulosa-cells, by inducing anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic actions on theca cells and exerting a cytostatic, but not cytotoxic effect, on granulosa cells. On the other hand, an over-expression of VEGF has been shown in the dense hyperthecotic stroma of polycystic ovaries, which is associated with increased ovarian stromal blood flow (54). Thus, the resveratrol-induced suppressive effect on VEGF expression may be of potential relevance in treating disorders related to increased vascular permeability and simultaneous over-expression of VEGF, such as seen in OHSS.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that resveratrol exerts a cytostatic, but not cytotoxic effect on rat granulosa cells. The present study also shows that resveratrol inhibits granulosa cell aromatization and decreases VEGF expression in granulosa cells. These actions may be of clinical relevance to conditions associated with highly vascularized theca-interstitial hyperplasia and abnormal angiogenesis, such as those seen in women with PCOS. Furthermore, these effects on granulosa cells also provide a rationale for new therapeutic approaches to prevent and/or treat OHSS and other gynecologic conditions with excessive VEGF expression and/or activity.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This study was supported by grant R01-HD050656 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to AJD).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nassiri-Asl M, Hosseinzadeh H. Review of the pharmacological effects of Vitis vinifera (Grape) and its bioactive compounds. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2009;23:1197–204. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labinskyy N, Csiszar A, Veress G, Stef G, Pacher P, Oroszi G, et al. Vascular dysfunction in aging: potential effects of resveratrol, an anti-inflammatory phytoestrogen. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:989–96. doi: 10.2174/092986706776360987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penumathsa SV, Maulik N. Resveratrol: a promising agent in promoting cardioprotection against coronary heart disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:275–86. doi: 10.1139/Y09-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yousuf S, Atif F, Ahmad M, Hoda N, Ishrat T, Khan B, et al. Resveratrol exerts its neuroprotective effect by modulating mitochondrial dysfunctions and associated cell death during cerebral ischemia. Brain research. 2009;1250:242–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athar M, Back JH, Kopelovich L, Bickers DR, Kim AL. Multiple molecular targets of resveratrol: Anti-carcinogenic mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;486:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Duleba AJ. Effects of resveratrol on proliferation and apoptosis in rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. Molecular human reproduction. 2010;16:251–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Sokalska A, Ortega I, Duleba AJ. Resveratrol inhibits the mevalonate pathway and potentiates the antiproliferative effects of simvastatin in rat theca-interstitial cells. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1252–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peitsidis P, Agrawal R. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in women with PCO and PCOS: a systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 20:444–52. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yada H, Hosokawa K, Tajima K, Hasegawa Y, Kotsuji F. Role of ovarian theca and granulosa cell interaction in hormone productionand cell growth during the bovine follicular maturation process. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1480–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das M, Djahanbakhch O, Hacihanefioglu B, Saridogan E, Ikram M, Ghali L, et al. Granulosa cell survival and proliferation are altered in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:881–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erickson GF, Magoffin DA, Cragun JR, Chang RJ. The effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factors-I and -II on estradiol production by granulosa cells of polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:894–902. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-4-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pigny P, Merlen E, Robert Y, Cortet-Rudelli C, Decanter C, Jonard S, et al. Elevated serum level of anti-mullerian hormone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to the ovarian follicle excess and to the follicular arrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5957–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durlinger AL, Visser JA, Themmen AP. Regulation of ovarian function: the role of anti-Mullerian hormone. Reproduction. 2002;124:601–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pellatt L, Hanna L, Brincat M, Galea R, Brain H, Whitehead S, et al. Granulosa cell production of anti-Mullerian hormone is increased in polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:240–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan HY, Shimada M, Liu Z, Cahill N, Noma N, Wu Y, et al. Selective expression of KrasG12D in granulosa cells of the mouse ovary causes defects in follicle development and ovulation. Development. 2008;135:2127–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.020560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiber JR, Nakamura K, Erickson GF. Progestins inhibit FSH-stimulated steroidogenesis in cultured rat granulosa cells. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 1980;19:165–73. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(80)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, Hsueh AJ, Erickson GF. LH stimulation of estrogen secretion by cultured rat granulosa cells. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 1981;24:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(81)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Duleba AJ. Effects of resveratrol on proliferation and apoptosis in rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. Molecular human reproduction. 2010;16:251–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortega I, Cress AB, Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Sokalska A, Moeller BC, et al. Simvastatin Reduces Steroidogenesis by Inhibiting Cyp17a1 Gene Expression in Rat Ovarian Theca-Interstitial Cells. Biol Reprod. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.094714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Sokalska A, Ortega I, Duleba AJ. Resveratrol inhibits the mevalonate pathway and potentiates the antiproliferative effects of simvastatin in rat theca-interstitial cells. Fertility and sterility. 2011;96:1252–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki Y, Tsuruga M, Zhou D, Fujita Y, Shang X, Dang Y, et al. Cytoskeletal disruption accelerates caspase-3 activation and alters the intracellular membrane reorganization in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259:64–78. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White SR, Williams P, Wojcik KR, Sun S, Hiemstra PS, Rabe KF, et al. Initiation of apoptosis by actin cytoskeletal derangement in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:282–94. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.3.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czajka-Oraniec I, Simpson ER. Aromatase research and its clinical significance. Endokrynol Pol. 61:126–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Resveratrol modulation of signal transduction in apoptosis and cell survival: a mini-review. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iijima K, Yoshizumi M, Hashimoto M, Kim S, Eto M, Ako J, et al. Red wine polyphenols inhibit proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and downregulate expression of cyclin A gene. Circulation. 2000;101:805–11. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.7.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawada N, Seki S, Inoue M, Kuroki T. Effect of antioxidants, resveratrol, quercetin, and N-acetylcysteine, on the functions of cultured rat hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 1998;27:1265–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alkhalaf M, Jaffal S. Potent antiproliferative effects of resveratrol on human osteosarcoma SJSA1 cells: Novel cellular mechanisms involving the ERKs/p53 cascade. Free radical biology & medicine. 2006;41:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui J, Sun R, Yu Y, Gou S, Zhao G, Wang C. Antiproliferative effect of resveratrol in pancreatic cancer cells. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 24:1637–44. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YA, Rhee SH, Park KY, Choi YH. Antiproliferative effect of resveratrol in human prostate carcinoma cells. J Med Food. 2003;6:273–80. doi: 10.1089/109662003772519813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fontecave M, Lepoivre M, Elleingand E, Gerez C, Guittet O. Resveratrol, a remarkable inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:277–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun NJ, Woo SH, Cassady JM, Snapka RM. DNA polymerase and topoisomerase II inhibitors from Psoralea corylifolia. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:362–6. doi: 10.1021/np970488q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragione FD, Cucciolla V, Borriello A, Pietra VD, Racioppi L, Soldati G, et al. Resveratrol arrests the cell division cycle at S/G2 phase transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:53–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider Y, Vincent F, Duranton B, Badolo L, Gosse F, Bergmann C, et al. Anti-proliferative effect of resveratrol, a natural component of grapes and wine, on human colonic cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;158:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuwajerwala N, Cifuentes E, Gautam S, Menon M, Barrack ER, Reddy GP. Resveratrol induces prostate cancer cell entry into s phase and inhibits DNA synthesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2488–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen GM. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J. 1997;326 (Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh CK, Kumar A, Hitchcock DB, Fan D, Goodwin R, Lavoie HA, et al. Resveratrol prevents embryonic oxidative stress and apoptosis associated with diabetic embryopathy and improves glucose and lipid profile of diabetic dam. Mol Nutr Food Res. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacCarrone M, Lorenzon T, Guerrieri P, Agro AF. Resveratrol prevents apoptosis in K562 cells by inhibiting lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase activity. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:27–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clement MV, Hirpara JL, Chawdhury SH, Pervaiz S. Chemopreventive agent resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes, triggers CD95 signaling-dependent apoptosis in human tumor cells. Blood. 1998;92:996–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsieh TC, Wu JM. Differential effects on growth, cell cycle arrest, and induction of apoptosis by resveratrol in human prostate cancer cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1999;249:109–15. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eppig JJ. Oocyte control of ovarian follicular development and function in mammals. Reproduction. 2001;122:829–38. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilchrist RB, Ritter LJ, Myllymaa S, Kaivo-Oja N, Dragovic RA, Hickey TE, et al. Molecular basis of oocyte-paracrine signalling that promotes granulosa cell proliferation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3811–21. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eppig JJ, Wigglesworth K, Pendola FL. The mammalian oocyte orchestrates the rate of ovarian follicular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2890–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052658699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hillier SG, Whitelaw PF, Smyth CD. Follicular oestrogen synthesis: the ‘two-cell, two-gonadotrophin’ model revisited. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 1994;100:51–4. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Leung LK. Pharmacological concentration of resveratrol suppresses aromatase in JEG-3 cells. Toxicol Lett. 2007;173:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Lee KW, Chan FL, Chen S, Leung LK. The red wine polyphenol resveratrol displays bilevel inhibition on aromatase in breast cancer cells. Toxicol Sci. 2006;92:71–7. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitehead SA, Lacey M. Phytoestrogens inhibit aromatase but not 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) type 1 in human granulosa-luteal cells: evidence for FSH induction of 17beta-HSD. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:487–94. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rice S, Mason HD, Whitehead SA. Phytoestrogens and their low dose combinations inhibit mRNA expression and activity of aromatase in human granulosa-luteal cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2006;101:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basini G, Tringali C, Baioni L, Bussolati S, Spatafora C, Grasselli F. Biological effects on granulosa cells of hydroxylated and methylated resveratrol analogues. Mol Nutr Food Res. 54(Suppl 2):S236–43. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Behringer RR, Finegold MJ, Cate RL. Mullerian-inhibiting substance function during mammalian sexual development. Cell. 1994;79:415–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baarends WM, Hoogerbrugge JW, Post M, Visser JA, De Rooij DG, Parvinen M, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone and anti-mullerian hormone type II receptor messenger ribonucleic acid expression during postnatal testis development and in the adult testis of the rat. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5614–22. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamat BR, Brown LF, Manseau EJ, Senger DR, Dvorak HF. Expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human granulosa and theca lutein cells. Role in corpus luteum development. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:157–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villasante A, Pacheco A, Ruiz A, Pellicer A, Garcia-Velasco JA. Vascular endothelial cadherin regulates vascular permeability: Implications for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:314–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang R, Zhang H, Zhu L. Inhibitory effect of resveratrol on the expression of the VEGF gene and proliferation in renal cancer cells. Mol Med Report. 4:981–3. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu HB, Zhang HF, Zhang X, Li DY, Xue HZ, Pan CE, et al. Resveratrol inhibits VEGF expression of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through a NF-kappa B-mediated mechanism. Hepatogastroenterology. 57:1241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trapp V, Parmakhtiar B, Papazian V, Willmott L, Fruehauf JP. Anti-angiogenic effects of resveratrol mediated by decreased VEGF and increased TSP1 expression in melanoma-endothelial cell co-culture. Angiogenesis. 13:305–15. doi: 10.1007/s10456-010-9187-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stubbs SA, Stark J, Dilworth SM, Franks S, Hardy K. Abnormal preantral folliculogenesis in polycystic ovaries is associated with increased granulosa cell division. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4418–26. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]