Abstract

Context:

Maternally inherited 3-kb STX16 deletions cause autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib (PHP-Ib) characterized by PTH resistance with loss of methylation restricted to the GNAS exon A/B.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to search for the 3-kb STX16 deletion and to establish haplotypes for the GNAS region for two PHP-Ib patients and their families.

Setting:

The study was conducted at a research laboratory and tertiary care hospitals.

Patients:

The index cases presented at the ages 8 and 9.5 yr, respectively, with hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and elevated PTH.

Interventions:

There were no interventions.

Results:

DNA analyses of the index cases revealed an isolated loss of the GNAS exon A/B methylation and the 3-kb STX16 deletion. In the first family, the patient's healthy mother and sister showed no genetic or epigenetic abnormality, yet microsatellite analysis of the GNAS region indicated that both siblings share the same maternal allele, with the exception of an allelic loss for marker 261P9-CA1 (located within STX16), leading to the conclusion that a de novo mutation had occurred on the maternal allele. In the second family, three siblings of the index case are also affected, and an analysis of their DNA revealed the 3-kb STX16 deletion, which was also found in the healthy mother and a maternal uncle. Analysis of the siblings of the deceased maternal grandfather and some of their descendants excluded the 3-kb STX16 deletion, but haplotype analysis of the GNAS region suggested that he had acquired the mutation de novo.

Conclusions:

De novo 3-kb STX16 deletions, reported only once previously, are infrequent but should be excluded in all cases of PHP-Ib, even when the family history is negative for an inherited form of this disorder.

Pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) is characterized by resistance toward PTH, which is either isolated or associated with resistance toward additional hormones such as TSH, GHRH, and calcitonin that mediate their actions through Gαs-coupled receptors. PHP type Ia (PHP-Ia) is caused by maternally inherited, heterozygous inactivating mutations in those GNAS exons that encode the α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gαs) (1, 2). Besides Gαs, the GNAS complex locus gives rise to several differently spliced transcripts. These alternative gene products include mRNA encoding the extra-large Gαs (XLαs) or the neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55) as well as the A/B transcript (also referred to as 1A) and the antisense transcript (3–5); note that the A/B-derived mRNA may be translated according to recent evidence (6). XLαs, A/B, and antisense transcripts are exclusively derived from the paternal allele on which their promoters are nonmethylated, whereas the NESP55 transcript is expressed only from the maternal allele on which its promoter is nonmethylated. The promoter giving rise to Gαs does not undergo parent-specific methylation. However, in certain tissues, such as the proximal renal tubules, the thyroid, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, and the pituitary, this ubiquitously expressed signaling protein is derived predominantly from the maternal allele, leading to the deficiency of this signaling protein and thus to hormonal resistance if this allele carries a mutation (3–5, 7, 8).

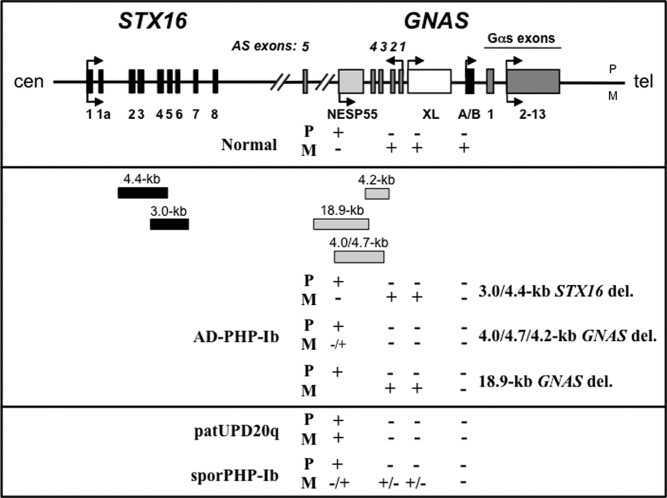

Individuals affected by PHP-Ia show, in addition to hormonal resistance, features of Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO), which can include a round face, short stature, brachydactyly, sc ossifications, and mental retardation (1, 2). Some of these AHO features do not depend on the parental origin of the mutation and are thus observed after maternal (PHP-Ia) or paternal inheritance (pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism). Mild AHO features have also been observed in some PHP-Ib patients, particularly in patients with the sporadic variant of this disorder, who frequently show, in addition to PTH-resistant hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia, resistance toward TSH and calcitonin (9–13). The most common form of autosomal dominant PHP-Ib (AD-PHP-Ib) is caused by maternally inherited, heterozygous deletions in the STX16 gene, which is located approximately 220 kb upstream of GNAS exon A/B (14, 15). STX16 is not an imprinted gene, but 3-kb and 4.4-kb deletions within this gene are associated with a loss of methylation restricted to GNAS exon A/B (Fig. 1); paternal inheritance of these deletions does not lead to obvious laboratory or clinically abnormalities (14, 15). AD-PHP-Ib caused by maternally inherited deletions involving NESP55 can also be associated with loss of methylation at exon A/B alone (16), but most deletions within GNAS lead to broad, typically complete loss of all maternal methylation imprints (17, 18); in contrast, sporadic PHP type Ib (PHP-Ib) patients often show incomplete epigenetic changes at this locus (12, 19–23).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the GNAS locus and the syntaxin 16 (STX16) gene. Upper panel, Exons are indicated by boxes; introns by lines; arrows show direction of transcription. P, Paternal; M, maternal; cen, centromeric; tel, telomeric. Normal parent-specific methylation pattern at the four GNAS differentially methylated regions (DMRs) is shown. +, Methylated DMR; −, nonmethylated DMR. Middle panel, Reported deletions shown as gray (GNAS) and black (STX16) boxes with the sizes of the different deletions on top. GNAS methylation pattern for DNA from patients with different forms of AD-PHP-Ib: STX16 deletions, deletions within GNAS, and GNAS deletion extending centromeric. Lower panel, GNAS methylation pattern for DNA from patients with paternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 20q (patUPD20q) and sporadic PHP-Ib (sporPHP-Ib).

Although 48 families have been described, in which maternally inherited 3-kb STX16 deletions are associated with PHP-Ib, only one individual was previously suspected to have a de novo mutation because the mother did not carry the mutation (24). Here we describe a sporadic PHP-Ib case and a multigenerational AD-PHP-Ib kindred in whom evidence for de novo 3-kb STX16 deletions could be obtained.

Patients and Methods

Patients

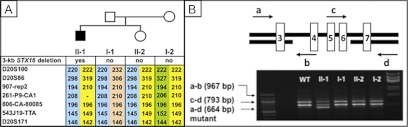

In the first family (no. 62), the index case (62/II-1) presented at the age of 9.5 yr with convulsions, and he was found to have hypocalcemia (1.55 mmol/liter), elevated serum phosphorus (2.56 mmol/liter), and elevated serum PTH level (403 pg/ml) (Fig. 2). There was no evidence for AHO and no family history for PHP.

Fig. 2.

A, Pedigree of family 62 and haplotype analysis: isolated loss of the GNAS exon A/B methylation was observed for patient 62/II-1, whereas his mother 62/I-2, his father 62/I-1, and his sister 62/II-2 revealed no epigenetic changes (black symbols, affected; white symbols, unaffected). Microsatellite analysis showed that the patient shares the same maternal allele with his unaffected sister, with the exception of marker 261P9-CA1, which is located within STX16 region; patient 62/II-1 is apparently hemizygous for allele 208, which he had inherited from his father, whereas his sister 62/II-2 had obtained allele 208 from her father 62/I-1 and allele 210 from her mother 62/I-2. These findings are consistent with an allelic loss for patient 62/II-1, which must have occurred de novo on the maternal allele. B, Scheme showing portions of the STX16 gene and the locations of primers (a, b, c, and d; arrows) used for multiplex PCR analysis to identify the heterozygous 3-kb STX16 microdeletion comprising exons 4–6. The shortest amplicon, amplified by primers a and d, was present only on the maternal allele of patient 62/I-2.

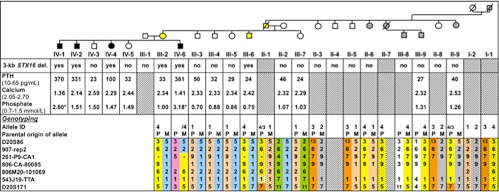

In the second family (no. 27), the index case (27/IV-6) presented with low calcium (1.41 mmol/liter), elevated serum phosphorus (3.18 mmol/liter), and elevated serum PTH level (381 pg/ml) at the age of 8 yr without evidence for AHO (14). He has five siblings, three of whom also showed biochemical evidence for PTH resistance, although only one older brother was clinically symptomatic (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The genetic analysis of family 27 revealed the 3-kb STX16 deletion in the index case 27/IV-6 and his three affected siblings (27/IV-1, 27/IV-2, and 27/IV-4) as well as their healthy mother (27/III-2) and their healthy maternal uncle (27/III-6). Microsatellite analysis of the GNAS region showed that the family members 27/IV-6, 27/III-2, and 27/III-6 were apparently hemizygous for marker 261P9-CA1, suggesting the loss of a parental allele, which is consistent with the identified 3-kb deletion. The deduced GNAS haplotype for 27/II-1 combined with exclusion of the 3-kb STX16 deletion in those members of the family, who are carriers of the disease-associated allele no. 4, suggested that 27/II-1 had been carrier of a de novo STX16 deletion, presumably on his paternal allele. Black symbols, affected; white symbols, unaffected; yellow and gray symbols, carriers of the disease-associated allele with or without the 3-kb STX16 deletion, respectively; asterisk, determined during childhood, normal range for this age group: 1.20–1.80 mmol/liter.

Methods

Lymphocyte DNA was extracted from both patients and the mother using standard methods after obtaining informed consent (14). The study was approved by Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board. GNAS methylation analysis was carried out as described (14) using bisulfite-modified genomic DNA. The 3-kb deletion within STX16 was analyzed by multiplex PCR analysis as described (11). Several microsatellite markers located of the chromosome 20q13.3 region were analyzed to generate haplotypes for both families (14, 25).

Results

In family 62, methylation analysis of the index case 62/II-1 revealed isolated loss of GNAS exon A/B methylation, consistent with the diagnosis of PHP-Ib; normal GNAS methylation patterns were observed for his healthy parents and sister (data not shown). Analysis of genomic DNA revealed the 3-kb STX16 deletion for the patient but not in his mother 62/I-2, his father 62/I-1, or his sister 62/II-2 (Fig. 2). Microsatellite analysis of the GNAS region showed that the patient shared the same maternal allele with his unaffected sister, with the exception of marker 261P9-CA1. Although the patient was apparently hemizygous for allele 208, which he had inherited from his father, his sister was heterozygous for this marker 261P9-CA1 (paternal allele 208, maternal allele 210). The mother 62/I-2 was also heterozygous for this marker (alleles 206 and 210), which is located within the STX16 region. Heterozygosity for the mother at marker 261P9-CA1 and lack of evidence for a maternally inherited allele at this marker in the patient 62/II-1 suggested an allelic loss and indicated that the identified mutation had occurred de novo on the maternal allele.

In family 27, genetic analysis revealed the 3-kb STX16 deletion in the index case 27/IV-6 and his three equally affected siblings (27/IV-1, 27/IV-2, and 27/IV-4) as well as in their healthy mother (27/III-2) and a healthy maternal uncle (27/III-6) but not in other maternal uncles or aunts (Fig. 3). Analysis of all other available members of the extended family revealed no evidence for the 3-kb deletion. Microsatellite analysis of the GNAS region showed that the index case 27/IV-6 and his healthy mother 27/III-2 were apparently hemizygous for different alleles of marker 261P9-CA1 (located within the STX16 region), which suggested the loss of a parental allele consistent with the identified 3-kb deletion. Because 27/III-2 and 27/III-6 are both healthy carriers of the 3-kb STX16 deletion, both had presumably inherited the allele no. 4 from their deceased father 27/II-1. Haplotype analyses of the siblings 27/III-3, 27/III-4, 27/III-5, and 27/III-7, and their healthy mother 27/II-2, who were not carriers of the deletion, allowed deduction of the alleles for 27/II-1. He is predicted to have carried alleles no. 1 and no. 4, an allele assignment that is consistent with the alleles established for his available siblings or their descendants, none of whom carries the 3-kb STX16 deletion. The parents of 27/II-1 are predicted to have been carriers of either allele no. 1 or allele no. 4.

The deduced GNAS haplotype for 27/II-1 combined with exclusion of the 3-kb STX16 deletion in those of his siblings, who are healthy carriers of the disease-associated allele no. 4, suggested that this deceased maternal grandfather of the index case 27/IV-6 had been carrier of a de novo STX16 deletion. Because he had no history of symptoms suggestive of hypocalcemia, it is likely that the mutation had occurred on his paternal allele.

Discussion

A maternally inherited 3-kb deletion within STX16 is the most common cause of AD-PHP-Ib, characterized by isolated loss of methylation at the exon A/B differentially methylated region of GNAS. Here we described two PHP-Ib kindreds in which compelling evidence for de novo 3-kb STX16 deletions was obtained, which appears to be a relatively rare occurrence because only one such mutation has been previously reported among 48 reported families with AD-PHP-Ib (Table 1) (9, 11, 13, 14, 19–21, 24, 26–34). When including patient 62/II-1 described in this report (note that several members of family 27 had been previously reported (14), the predicted de novo mutation rate for the 3-kb STX16 deletion of 6.1% (three of 49) is lower than the rates described for other autosomal dominant diseases, including Marfan syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, Carney complex, and CHARGE (the association of coloboma, heart defect, choanal atresia, retardation, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies) (25–57%) (35–39). It may, however, be higher because clinical consequences of the 3-kb STX16 deletion and associated epigenetic changes can remain silent for several generations if this mutation resides on the paternal allele. Consequently, there may be many more carriers of the STX16 deletion in the general population, and the de novo mutation rate could thus be substantially higher. Based on the analysis of only those PHP-Ib patients, who carry the deletion on the maternal allele, the de novo mutation rate would be estimated at 4.1% (two of 49); however, for several published, apparently sporadic PHP-Ib cases with the 3-kb deletion, parents were not available for genetic testing, thus allowing no conclusions regarding the possible lack of inheritance of the genetic mutation (see Table 1). Furthermore, if de novo 3-kb STX16 deletions occur with equal frequency on the maternal and the paternal allele, but the latter become clinically apparent after one or several generations, the rate of new mutations may be twice as high. However, this rate would still be lower than that estimated for other autosomal dominant diseases.

Table 1.

Families with AD-PHP-Ib due to the 3-kb STX16 deletion

| Total number of reported families | Documented de novo deletion | Unknown when deletion first evolved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16a | 3 | 14 | |

| 1 | 27 | ||

| 1 | 32 | ||

| 5 | 19 | ||

| 5 | 20 | ||

| 1 | 9 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 24 | |

| 3 | 1 | 34 | |

| 1 | 11 | ||

| 1 | 31 | ||

| 1 | 30 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 29 | |

| 2 | 1 | 26 | |

| 2 | 1 | 28 | |

| 1 | 13 | ||

| 4 | 2 | 21 | |

| 1b | 33 | ||

| 2a | 2 | This report | |

| Total: 49 | 3 | 9 |

The number of previously published unrelated families is provided, in which at least one member is affected by PHP-Ib and carries a maternally inherited STX16 deletion. For one case, no mutation could be identified in both parents, leading to the conclusion that a de novo mutation had occurred; however, for several PHP-Ib cases without a family history of the disease, the carrier status of the parents is unknown.

The affected members of family 27 had been included in a previous report (14), but this family was counted only once. Family 62 has not previously been reported.

The mother, brother, and sister of the patient had hypocalcemia, but only the patient was analyzed for the mutation.

PHP-Ib is caused by methylation and imprinting defects at the maternal GNAS locus with subsequent loss of Gαs protein expression in renal proximal tubules. At least two distinct types of epigenetic/genetic defects have been described in AD-PHP-Ib, which lead to indistinguishable clinical and laboratory phenotypes. These familial forms of PHP-Ib are caused by maternally inherited, heterozygous deletions within or upstream of the GNAS locus, which are associated either with a loss of all maternal GNAS methylation imprints or with a loss of exon A/B methylation alone (see Fig. 1) (14–18). Maternally but not paternally inherited deletions of STX16 lead to AD-PHP-Ib; the de novo mutation in family 62 thus occurred on the maternal allele as shown by the allelic loss of microsatellite marker 261P9-CA1. In contrast, the de novo mutation in family 27 did not lead to clinical and epigenetic phenotypes until two generations later, i.e. the healthy male 27/II-1 transmitted the disease-associated allele to his healthy daughter 27/III-2 and his healthy son 27/III-6, but led to clinical and laboratory abnormalities only in the three affected children of the female 27/III-2, thus highlighting again the parent-of-origin-specific transmission of the disease.

Our current findings and review of the literature indicates that de novo 3-kb STX16 deletions are fairly infrequent, although this deletion occurs between two almost perfect repeats comprising 391 bp (14). Despite its apparent rarity, the 3-kb STX16 deletion should be excluded in all PHP-Ib cases without an apparent family history because the disease can be silent for generations. Identification of this most frequent cause of AD-PHP-Ib does allow precise genetic counseling without the need for extensive epigenetic evaluation of the GNAS locus and will exclude the sporadic form of PHP-Ib that, in addition to PTH resistance, appears to be associated more frequently with resistance toward other hormones and with some AHO features (9–13, 19–24).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the investigated AD-PHP-Ib kindreds for participating in this research study.

This work was supported by Research Grants R01 DK073911 (to M.B.) and R37 DK46718 (to H.J.) from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. S.T. was a recipient of a grant from the Fulbright Scholarship Program.

Disclosure Summary: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- AD-PHP-Ib

- Autosomal dominant PHP-Ib

- AHO

- Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy

- DMR

- differentially methylated regions

- Gαs

- α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein

- NESP55

- neuroendocrine secretory protein 55

- PHP

- pseudohypoparathyroidism

- PHP-Ia

- PHP type Ia

- PHP-Ib

- PHP type Ib.

References

- 1. Levine M. 2005. Hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism. In: DeGroot L, Jameson J, eds. Endocrinology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1611–1636 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weinstein L, Yu S, Warner DR, Liu J. 2001. Endocrine manifestations of stimulatory G protein α-subunit mutations and the role of genomic imprinting. Endocr Rev 22:675–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wroe SF, Kelsey G, Skinner JA, Bodle D, Ball ST, Beechey CV, Peters J, Williamson CM. 2000. An imprinted transcript, antisense to Nesp, adds complexity to the cluster of imprinted genes at the mouse Gnas locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:3342–3346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peters J, Wroe SF, Wells CA, Miller HJ, Bodle D, Beechey CV, Williamson CM, Kelsey G. 1999. A cluster of oppositely imprinted transcripts at the Gnas locus in the distal imprinting region of mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:3830–3835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayward BE, Moran V, Strain L, Bonthron DT. 1998. Bidirectional imprinting of a single gene: GNAS1 encodes maternally, paternally, and biallelically derived proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15475–15480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Puzhko S, Goodyer CG, Kerachian MA, Canaff L, Misra M, Jüppner H, Bastepe M, Hendy G. 2011. Parathyroid hormone signaling via Gαs is selectively inhibited by an NH2-terminally truncated Gαs: implications for pseudohypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res 26:2473–2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williamson CM, Ball ST, Nottingham WT, Skinner JA, Plagge A, Turner MD, Powles N, Hough T, Papworth D, Fraser WD, Maconochie M, Peters J. 2004. A cis-acting control region is required exclusively for the tissue-specific imprinting of Gnas. Nat Genet 36:894–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu S, Yu D, Lee E, Eckhaus M, Lee R, Corria Z, Accili D, Westphal H, Weinstein LS. 1998. Variable and tissue-specific hormone resistance in heterotrimeric Gs protein α-subunit (Gsα) knockout mice is due to tissue-specific imprinting of the Gsα gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:8715–8720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Nanclares GP, Fernández-Rebollo E, Santin I, García-Cuartero B, Gaztambide S, Menéndez E, Morales MJ, Pombo M, Bilbao JR, Barros F, Zazo N, Ahrens W, Jüppner H, Hiort O, Castaño L, Bastepe M. 2007. Epigenetic defects of GNAS in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism and mild features of Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2370–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mariot V, Maupetit-Méhouas S, Sinding C, Kottler ML, Linglart A. 2008. A maternal epimutation of GNAS leads to Albright osteodystrophy and parathyroid hormone resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unluturk U, Harmanci A, Babaoglu M, Yasar U, Varli K, Bastepe M, Bayraktar M. 2008. Molecular diagnosis and clinical characterization of pseudohypoparathyroidism type-Ib in a patient with mild Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy-like features, epileptic seizures, and defective renal handling of uric acid. Am J Med Sci 336:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mantovani G, de Sanctis L, Barbieri AM, Elli FM, Bollati V, Vaira V, Labarile P, Bondioni S, Peverelli E, Lania AG, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A. 2010. Pseudohypoparathyroidism and GNAS epigenetic defects: clinical evaluation of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy and molecular analysis in 40 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanchez J, Perera E, Jan de Beur S, Ding C, Dang A, Berkovitz GD, Levine MA. 2011. Madelung-like deformity in pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E1507–E1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Hendy GN, Indridason OS, Josse RG, Koshiyama H, Körkkö J, Nakamoto JM, Rosenbloom AL, Slyper AH, Sugimoto T, Tsatsoulis A, Crawford JD, Jüppner H. 2003. Autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib is associated with a heterozygous microdeletion that likely disrupts a putative imprinting control element of GNAS. J Clin Invest 112:1255–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linglart A, Gensure RC, Olney RC, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. 2005. A novel STX16 deletion in autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib redefines the boundaries of a cis-acting imprinting control element of GNAS. Am J Hum Genet 76:804–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richard N, Abeguilé G, Coudray N, Mittre H, Gruchy N, Andrieux J, Cathebras P, Kottler ML. 2012. A new deletion ablating NESP55 causes loss of maternal imprint of A/B GNAS and autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E863–E867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bastepe M, Fröhlich LF, Linglart A, Abu-Zahra HS, Tojo K, Ward LM, Jüppner H. 2005. Deletion of the NESP55 differentially methylated region causes loss of maternal GNAS imprints and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. Nat Genet 37:25–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chillambhi S, Turan S, Hwang DY, Chen HC, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. 2010. Deletion of the noncoding GNAS antisense transcript causes pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and biparental defects of GNAS methylation in cis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3993–4002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu J, Nealon JG, Weinstein LS. 2005. Distinct patterns of abnormal GNAS imprinting in familial and sporadic pseudohypoparathyroidism type IB. Hum Mol Genet 14:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linglart A, Bastepe M, Jüppner H. 2007. Similar clinical and laboratory findings in patients with symptomatic autosomal dominant and sporadic pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib despite different epigenetic changes at the GNAS locus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 67:822–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zazo C, Thiele S, Martín C, Fernández-Rebollo E, Martinez-Indart L, Werner R, Garin I, Group SP, Hiort O, Pérez de Nanclares G. 2011. Gsα activity is reduced in erythrocyte membranes of patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism due to epigenetic alterations at the GNAS locus. J Bone Miner Res 26:1864–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernández-Rebollo E, Pérez de Nanclares G, Lecumberri B, Turan S, Anda E, Pérez de Nanclares G, Feig D, Nik-Zainal S, Bastepe M, Jüppner H. 2011. Exclusion of the GNAS locus in PHP-Ib patients with broad GNAS methylation changes: evidence for an autosomal recessive form of PHP-Ib? J Bone Miner Res 26:1854–1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pérez-Nanclares G, Romanelli V, Mayo S, Garin I, Zazo C, Fernandez-Rebollo E, Martínez F, Lapunzina P, de Nanclares GP. 2012. Detection of hypomethylation syndrome among patients with epigenetic alterations at the GNAS locus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E1060–E1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Linglart A, Maghnie M, Cisternino M, Corbetta S, Lania AG, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A. 2007. Genetic analysis and evaluation of resistance to thyrotropin and growth hormone-releasing hormone in pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:3738–3742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bastepe M, Pincus JE, Sugimoto T, Tojo K, Kanatani M, Azuma Y, Kruse K, Rosenbloom AL, Koshiyama H, Jüppner H. 2001. Positional dissociation between the genetic mutation responsible for pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and the associated methylation defect at exon A/B: evidence for a long-range regulatory element within the imprinted GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet 10:1231–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kinoshita K, Minagawa M, Takatani T, Takatani R, Ohashi M, Kohno Y. 2011. Establishment of diagnosis by bisulfite-treated methylation-specific PCR method and analysis of clinical characteristics of pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1b. Endocr J 58:879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laspa E, Bastepe M, Jüppner H, Tsatsoulis A. 2004. Phenotypic and molecular genetic aspects of pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib in a Greek kindred: evidence for enhanced uric acid excretion due to parathyroid hormone resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5942–5947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maupetit-Méhouas S, Mariot V, Reynès C, Bertrand G, Feillet F, Carel JC, Simon D, Bihan H, Gajdos V, Devouge E, Shenoy S, Agbo-Kpati P, Ronan A, Naud-Saudreau C, Lienhardt A, Silve C, Linglart A. 2011. Quantification of the methylation at the GNAS locus identifies subtypes of sporadic pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. J Med Genet 48:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin HY, Lee BH, Choi JH, Kim GH, Kim JK, Lee JH, Yu J, Yoo JH, Ko CW, Lim HH, Chung HR, Yoo HW. 2011. Clinical characterization and identification of two novel mutations of the GNAS gene in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism and pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75:207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cavaco BM, Tomaz RA, Fonseca F, Mascarenhas MR, Leite V, Sobrinho LG. 2010. Clinical and genetic characterization of Portuguese patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib. Endocrine 37:408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turan S, Akin L, Akcay T, Adal E, Sarikaya S, Bastepe M, Jüppner H. 2010. Recessive versus imprinted disorder: consanguinity can impede establishing the diagnosis of autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib.. Eur J Endocrinol 163:489–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mahmud FH, Linglart A, Bastepe M, Jüppner H, Lteif AN. 2005. Molecular diagnosis of pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib in a family with presumed paroxysmal dyskinesia. Pediatrics 115:e242–e244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Todorova-Koteva K, Wood K, Imam S, Jaume JC. 2012. Screening for parathyroid hormone resistance in patients with non-phenotypically evident pseudohypoparathyroidism. Endocr Pract 1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freson K, Izzi B, Labarque V, Van Helvoirt M, Thys C, Wittevrongel C, Bex M, Bouillon R, Godefroid N, Proesmans W, de Zegher F, Jaeken J, Van Geet C. 2008. GNAS defects identified by stimulatory G protein α-subunit signalling studies in platelets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4851–4859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dietz H. 2011. Marfan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, BT, Dolan CR, Stephens K, eds. GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stratakis C, Horvath A. 2010. Carney complex. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington [Google Scholar]

- 37. Terzi YK, Oguzkan-Balci S, Anlar B, Aysun S, Guran S, Ayter S. 2009. Reproductive decisions after prenatal diagnosis in neurofibromatosis type 1: importance of genetic counseling. Genet Couns 20:195–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vuorela P, Ala-Mello S, Saloranta C, Penttinen M, Pöyhönen M, Huoponen K, Borozdin W, Bausch B, Botzenhart EM, Wilhelm C, Kääriäinen H, Kohlhase J. 2007. Molecular analysis of the CHD7 gene in CHARGE syndrome: identification of 22 novel mutations and evidence for a low contribution of large CHD7 deletions. Genet Med 9:690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernández L, Lapunzina P, Pajares IL, Criado GR, García-Guereta L, Pérez J, Quero J, Delicado A. 2005. Higher frequency of uncommon 1.5–2 Mb deletions found in familial cases of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 136:71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]