Abstract

Diabetes affects more than 300 million individuals globally, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. As the incidence and prevalence of diabetes continue to escalate with the force of an approaching tsunami, it is imperative that we better define the biological mechanisms causing both obesity and diabetes and identify optimal prevention and treatment strategies that will enable a healthier environment and calmer waters. New guidelines from the American Diabetes Association/European Association of the Study of Diabetes and The Endocrine Society encourage individualized care for each patient with diabetes, both in the outpatient and inpatient setting. Recent data suggest that restoration of normal glucose metabolism in people with prediabetes may delay progression to type 2 diabetes (T2DM). However, several large clinical trials have underscored the limitations of current treatment options once T2DM has developed, particularly in obese children with the disease. Prospects for reversing new-onset type 1 diabetes also appear limited, although recent clinical trials indicate that immunotherapy can delay the loss of β-cell function, suggesting potential benefits if treatment is initiated earlier. Research demonstrating a role for the central nervous system in the development of obesity and T2DM, the identification of a new hormone that simulates some of the benefits of exercise, and the development of new β-cell imaging techniques may provide novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers of early diabetes detection for optimization of interventions. Today's message is that a diabetes tsunami is imminent, and the only way to minimize the damage is to create an early warning system and improve interventions to protect those in its path.

Diabetes affects 25.8 million Americans, increases cardiovascular (CV) mortality and stroke incidence by 2- to 4-fold, and remains the leading cause of blindness before age 70, end-stage renal disease, and nontraumatic lower extremity amputation in the United States (1). An astounding 11.3% of adults in the United States, or more than one in 10, have diabetes (1), and globally, 346 million people have diabetes (2). In the United States alone, the societal cost of diabetes was estimated to be $174 billion dollars in 2007 (3). Unfortunately, the number of people diagnosed continues to increase; in fact, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the crude prevalence of diagnosed diabetes increased by 176% over the last three decades (4). Because diabetes prevalence is increasing in both children (5) and adults (4), it is imperative that we optimize treatment methods while simultaneously developing public health strategies aimed at preventing the further spread of this pandemic.

Over recent years, various changes have occurred that will likely influence clinical diabetes care. There have been an increasing number and variety of antihyperglycemic agents introduced to the clinician's armamentarium, new data regarding the benefits vs. risks of tight glycemic control, increasing concerns regarding drug safety, and increasing discourse about personalized medicine and “patient-centered” care. New clinical practice guidelines have been shaped by these changes as well as several recent clinical trials.

New Clinical Guidelines

ADA/EASD 2012 position statement: management of T2DM—a patient-centered approach

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association of the Study of Diabetes (EASD) published a new position statement in 2012 entitled “Management of Type 2 Diabetes: A Patient Centered Approach” (6, 7). The new guidelines include treatment nuances that recommend a personalized approach to each individual patient. The main glycemic target remains the same, recommending a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target of less than 7% with preprandial glucose of less than 130 mg/dl and a postprandial glucose of less than 180 mg/dl. However, the recommendations have changed for specific populations. These recommendations include more stringent targets (HbA1c goal, 6.0–6.5%) for younger, healthier patients (if attainable without significant hypoglycemia) and less strict targets (HbA1c goal, 7.5–8.0%) for older individuals with more comorbidities, or for those who are more prone to have hypoglycemia. The approach of the committee was to encourage physicians to critically evaluate the risk-to-benefit ratio for each patient rather than provide a prescriptive algorithm for all patients.

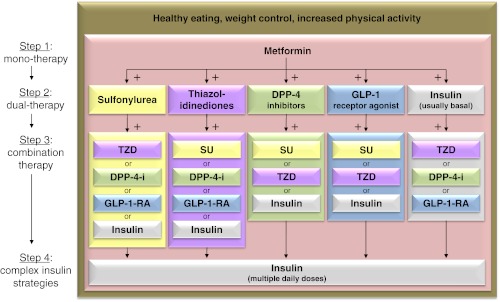

The therapeutic guidelines were based largely on a review of a recent meta-analysis of studies of antidiabetes medications. This thorough meta-analysis examined 140 head-to-head trials and 26 observational studies of monotherapy and combination therapy and included intermediate and long-term clinical outcomes (8). The study found that most medications decreased HbA1c level by about 1%, and most two-drug combinations generally produced similar reductions. Evidence continues to support metformin as a first-line agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Most two-drug combinations similarly reduce HbA1c levels, but some increased the risk for hypoglycemia and other adverse events. Thus, in the 2012 ADA/EASD position statement, metformin remains as the first-line treatment for T2DM (Fig. 1) (6). The next step in treatment depends on the specific needs of the patient and incorporates five different medication choices as add-on therapy to metformin treatment. For example, if weight loss is desired, then glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors should be considered as the initial add-on medication. If hypoglycemia avoidance is the most important consideration for a particular patient, then thiazolidinediones (TZDs), GLP-1 receptor agonists, or DPP-4 inhibitors would each be good next-choice medications to add on to metformin treatment. If cost is a critical factor, sulfonylureas or insulin should be considered. The third step includes a variety of combination therapies, as shown in Fig. 1. If at presentation a patient's HbA1c is elevated to levels of more than 10–12%, the recommendation is to consider initiating treatment with multidrug combination therapy, and if a patient's glucose control is extremely poor, initial treatment with insulin is indicated. Basal insulin should be started first, followed by the addition of short-acting, meal-time insulin to the largest meal of the day, and eventually to all meals of the day resulting in basal-bolus therapy. For example, one combination therapy recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) could include the use of metformin, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, and basal insulin (9). In summary, the committee's message is acknowledging and emphasizing the role of lifestyle before metformin in some patients with modest diabetes, calibration of treatment targets to meet the specific needs of each patient, harmonization of five dual options with metformin, the recognition of the role of initial combination therapy with the endorsement of triple therapy when required, and the inclusion of a variety of different insulin preparations and regimens in diabetes treatment.

Fig. 1.

The ADA/ESAD 2012 Position Statement algorithm on antihyperglycemic therapy in T2DM (abbreviated figure). The guidelines emphasize taking a personalized approach to each patient; focusing initially on lifestyle changes in patients with mild diabetes, progressing to metformin, then other oral and injectable medications, and eventually to insulin to ensure glycemic control. DPP-4-I, DPP-4 inhibitor; GLP-1-RA, GLP-1 receptor agonist; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione. [Adapted from S. E. Inzucchi et al.: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 35:1364–1379, 2012 (6), with permission. © American Diabetes Association.]

The Endocrine Society: practice guidelines for the management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in noncritical care setting

In January 2012, The Endocrine Society put forth clinical practice guidelines for the management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in a noncritical care setting (10). They recommend that all patients who are admitted to the hospital should be screened for diabetes. If the patient does not have a history of diabetes and their blood glucose (BG) is less than 140 mg/dl, then point of care BG monitoring should be set according to the patient's clinical status. If the patient's BG is greater than 140 mg/dl with no prior history of diabetes, then point of care BG monitoring should be conducted for 24–48 h, and a HbA1c should be checked. If the patient has a prior history of diabetes, then continued BG monitoring is recommended throughout the hospitalization. The glycemic targets for a majority of these patients include a preprandial BG below 140 mg/dl and random BG below 180 mg/dl. Glycemic targets should be modified according to patients' clinical status; for patients who achieve and maintain glycemic control without hypoglycemia, a lower target range may be reasonable. For patients with a terminal illness and/or with a limited life expectancy or at high risk for hypoglycemia, a higher BG target range of less than 200 mg/dl may be reasonable. To avoid hypoglycemia, diabetes therapy should be reassessed and modified when BG values are 100 mg/dl or less.

Clinical Trials

The Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS)

Several clinical trials published last year provide insight into the necessity of diabetes prevention and early treatment interventions. A decade ago, the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) (11) found that in individuals at high risk for developing T2DM, lifestyle intervention reduces the incidence of diabetes by more than half and metformin treatment reduced the incidence of diabetes by one third compared with placebo. The follow-up study, the DPPOS (12), examined whether regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation during the 3-yr DPP study has a carryover affect to reduce the long-term risk of diabetes over the next 6 yr, during the follow-up period. DPPOS included 1990 participants from the original DPP cohort of 3234 patients. The study found that diabetes risk was 56% lower in patients who returned to normal glucose tolerance (NGT) vs. those who do not return to NGT (hazard ratio, 0.44; 95% confidence interval, 0.37–0.55; P < 0.0001) regardless of whether they were in the metformin or lifestyle intervention group. Individuals who did not revert at any time to NGT had a progressive rise in the development of diabetes. Thus, it appears that individuals at high risk for developing diabetes benefit most if an early intervention is effective in normalizing their BG levels, whereas individuals who do not respond to early intervention are more likely to continue to progress to develop diabetes. Identifying early interventions for high-risk individuals who do not respond to metformin or lifestyle may thus be important in decreasing the emergence and rate of disease progression.

The ORIGIN trial

The question remains whether early aggressive intervention in people with prediabetes will not only benefit progression to diabetes but also reduce morbidity and mortality. The ORIGIN (Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention) trial addressed the question whether patients with dysglycemia and at high risk for CV disease would benefit from early intervention with basal insulin therapy aimed at reducing CV outcomes. ORIGIN, the largest diabetes clinical trial ever conducted, included 12,537 patients, mean age 63.5 yr old, from 40 different countries (13). They had dysglycemia (defined as impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or newly diagnosed T2DM by oral glucose tolerance test or with a history of prior diabetes on oral antidiabetes medication) with high CV risk (defined as prior stroke, myocardial infarction, revascularization, the presence of proteinuria, left ventricular hypertrophy, more than 50% stenosis of a major artery, etc.). The hypothesis was that normalization of fasting glucose levels would reduce the risk of CV outcomes long term (CV outcomes were defined as CV death, nonfatal stroke, revascularization, or heart failure). The intervention was glargine titrated to lower fasting plasma glucose (FPG) to 95 mg/dl or less vs. standard-of-care treatment. This treatment strategy effectively reduced FPG by about 30 mg/dl into the normal range (median HbA1c was lowered to 6.4%) for more than 6 yr. Nevertheless, there was no discernable effect on CV outcomes. Early treatment with glargine insulin did, however, slow progression of dysglycemia, with 28% less progression to diabetes in prediabetic patients, and did not appear to alter cancer incidence. However, more aggressive insulin treatment was associated with modest weight gain, as would be expected, and a modest increase in hypoglycemia. Thus, early and aggressive basal insulin therapy for patients with prediabetes cannot be recommended for prevention of CV complications. It remains to be established whether other therapeutic approaches would be more successful.

Recent bariatric surgery trials

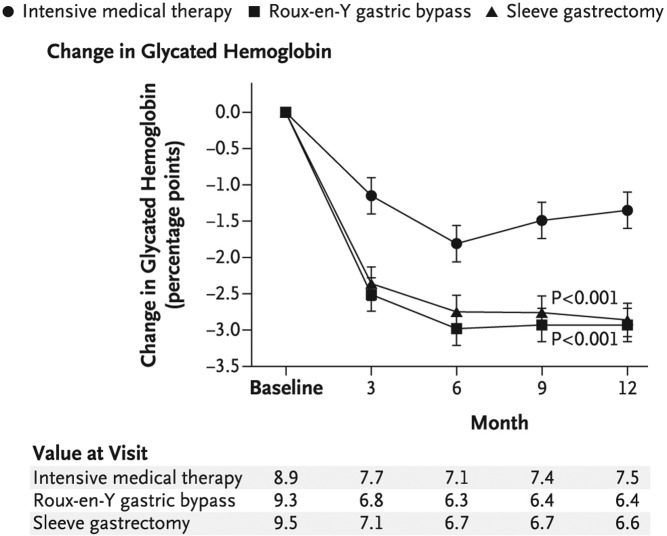

The gaps in effective medical treatment of obesity and T2DM have opened the door to a more invasive therapeutic approach, namely bariatric surgery. Two single-center, randomized bariatric surgery trials were published in the New England Journal of Medicine this year. The studies compared bariatric surgery vs. conventional medical treatment (diet/lifestyle modifications and diabetes treatment provided by a health-care team) in poorly controlled obese patients with long-standing T2DM. In the European study (14), patients with diabetes (n = 60) aged 30–50 with morbid obesity (BMI, ∼45 kg/m2), an average HbA1c of 8.7 ± 1.45%, and disease duration of approximately 6 yr were randomized to one of three treatment groups: medical therapy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), or biliopancreatic diversion. At 2 yr, the percentage diabetes remission (defined as FPG <100 mg/dl and HgbA1c <6.5% without pharmacotherapy) was as follows: no remission in the medical therapy group (BMI, 43.1 kg/m2; HbA1c, 7.7%), 75% remission in the gastric-bypass group (BMI, 29.3 kg/m2; HbA1c, 6.4%; P = 0.003 vs. medical therapy group), and 95% remission in the biliopancreatic-diversion group (BMI, 29.2 kg/m2; HbA1c, 5.0%; P < 0.001 vs. medical therapy group). In the American study (15), the patients with diabetes (n = 150) were less obese (BMI, ∼36 kg/m2) with a HbA1c of 9.2% and a disease duration of approximately 8.5 yr. The patients were randomized to three treatment groups: medical therapy, RYGB, or sleeve gastrectomy. One year after the intervention, the percentage of diabetes remission (defined as a HbA1c < 6.0% without medication) was 12% in the medical treatment group (BMI, 34.4 kg/m2; HbA1c, 7.5%), 42% in the gastric-bypass group (BMI, 26.8 kg/m2; HbA1c, 6.4%; P < 0.002 vs. medical therapy), and 37% in the sleeve-gastrectomy group (BMI, 27.2 kg/m2; HbA1c, 6.6%; P < 0.008 vs. medical therapy) (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that 28% of the sleeve gastrectomy group did, in fact, require antidiabetes medications.

Fig. 2.

Medical therapy vs. RYGB and sleeve gastrectomy. Marked improvement in HbA1c in the RYGB and sleeve gastrostomy treatment groups during the study period. P values are for the comparison between each surgical group and the medical-therapy group and were calculated from a repeated-measures model that considers data over time. [Reproduced from P. R. Schauer et al.: Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 366:1567–1576, 2012 (15), with permission. © Massachusetts Medical Society.]

These randomized, controlled studies demonstrate a rapid improvement in glucose metabolism, and in many cases reversal of diabetes, with only a modest number of surgical complications reported over a period of 1–2 yr. Notably however, many questions still remain to be answered. We do not know the length of time that diabetes remission will persist in patients who undergo these procedures. Initially, the results of bariatric surgery are quite dramatic, but in many cases, these effects tend to wane over time (16, 17). Because these are short-term studies, we have yet to determine the long-term beneficial effects of weight loss and diabetes remission balanced with the potential long-term detrimental effects that may emerge over time, such as hypoglycemia and nutritional deficiencies (16, 17). Moreover, the long-term effects on other clinical outcomes, such as CV disease, are not known. Additionally, it is not known how overweight, rather than obese, patients with T2DM may benefit from bariatric surgery, nor do we know the risk-to-benefit ratio for the increasing number of adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery (18). Finally, we have yet to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for the dramatic effect of bariatric surgery on diabetes, i.e. the relative contribution of changes in food intake per se and various other biological changes induced by different types of surgery. Thus, although bariatric surgery results in dramatic resolution of diabetes, many questions still need to be addressed.

The TODAY study

Although the prevalence of overweight/obese children has not changed in recent years (as assessed by NHANES data from 1999–2000 to 2007–2008), the incidence of prediabetes/diabetes in this population has tripled (5). Thus, examining early and aggressive interventions for adolescents with recently diagnosed T2DM is critical. The Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) trial addressed whether early initiation of combination therapy in youth-onset T2DM would be more effective in sustaining glycemic control than standard therapy with metformin (19). This multicenter trial randomized 699 obese (BMI ≥ 85th percentile) youth, ages 10 to 17 yr, with short-duration T2DM (<2 yr) and compared three treatment regimens: 1) metformin 1 g twice per day; 2) metformin 1 g twice per day and rosiglitazone 4 mg per day; and 3) metformin 1 g twice per day and intensive lifestyle management. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a HbA1c of 8.0% or greater for at least 6 months or metabolic decompensation, defined as the inability to wean off from temporary insulin therapy. The youth enrolled averaged 14 yr of age, were obese (average BMI, 34.9 kg/m2) and mostly minorities, and close to half were underprivileged adolescents. Regrettably, nearly half (45.6%) of the enrolled youth failed treatment over a period of 3.9 yr. Perhaps even more striking, the average time to treatment failure was a mere 11.5 months. Treatment with metformin plus rosiglitazone had a statistically lower failure rate than metformin alone (P = 0.006), but treatment with metformin plus lifestyle and metformin plus rosiglitazone was not statistically different (Table 1). As one might expect with drug-combination treatment, metformin plus rosiglitazone improved both insulin secretion and sensitivity. The modest benefit of adding a TZD may, however, be offset by the greater weight increases seen in adolescents taking rosiglitazone; long term, the consequences of this observed weight gain could be more detrimental than those observed in this relatively short-duration study. These data have clinical implications for youth with T2DM: treatment failure occurs quite rapidly, multiple medications will often be required early in the course of treatment, and the role of intensive lifestyle interventions appears to be limited (at least in this trial). The message from this study is quite serious, if not alarming. Pathophysiological differences (e.g. greater underlying β-cell function defects or much greater insulin resistance) in adolescents who develop T2DM may contribute to accelerated treatment failure. Puberty is known to “induce” profound insulin resistance within the realm of normal physiology (20) and perhaps predisposes youth to more rapid progression to disease. Thus, early screening of obese children at high risk for developing T2DM (perhaps with a HbA1c or postmeal glucose) with implementation of aggressive treatments may be more likely to prevent the development of T2DM and effectively achieve and sustain long-term treatment goals. Finally, the TODAY study is a solemn call to action for public policy initiatives targeting obesity prevention in children as well as a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms driving obesity.

Table 1.

Rates of treatment failure in the TODAY study

| Treatment arm | Failure rate (%) | Median time to failure (months) |

|---|---|---|

| Metformin + rosiglitazone (n = 230) | 38.6 | 12.0 |

| Metformin + lifestyle (n = 234) | 46.6 | 11.8 |

| Metformin alone (n = 232) | 51.7 | 10.3 |

Nearly half (45.6%) of adolescents enrolled in the TODAY study failed treatment within the 3.9-yr follow-up period, with the mean time to failure being a striking period of only 11.5 months. For primary outcome: metformin alone vs. metformin and lifestyle (P = 0.17); metformin alone vs. metformin and rosiglitazone (P = 0.006); metformin and lifestyle vs. metformin and rosiglitazone (P = 0.15) (19).

The Abatacept trial and the Protégé trial

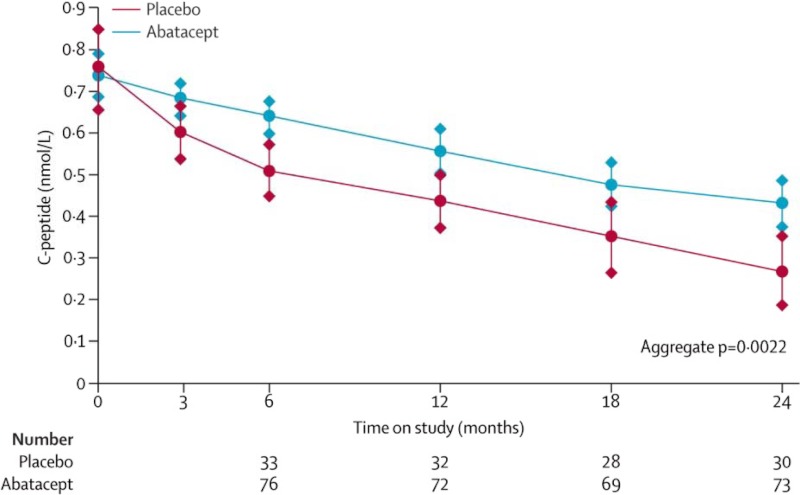

The goal of reversing new-onset type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and/or dampening of β-cell destruction once it begins has been explored in two recent clinical trials published in the Lancet employing immunosuppressive medications anti-CTLA-4 (i.e. abatacept) and anti-CD3 (i.e. teplizumab) monoclonal antibodies (21, 22). The TrialNet Abatacept Study was a double-blinded, randomized, multicenter trial involving young patients (average age, 13–14) with newly diagnosed T1DM (∼3 months duration). Patients received either abatacept 10 mg/kg (maximum 1000 mg per dose) or placebo on d 1, 14, 28, and monthly for a total of 27 infusions over 2 yr. The primary outcome was C-peptide response (21). The study found that abatacept slowed the reduction of β-cell function by about 9.6 months, with 59% higher C-peptide area under the curve (AUC) responses at 2 yr (Fig. 3). The Protégé Trial was a multicenter trial that included young adults (average age, 18 yr) from the United States, Europe, Israel, and India with diabetes of 8–9 months duration. Patients were randomized to receive: 1) 14-d full-dose teplizumab; 2) 14-d low-dose teplizumab; 3) 6-d full-dose teplizumab; or 4) placebo (22). There was no statistically significant difference in primary outcomes (i.e. reduction in insulin dose by 50% and lowering of HbA1c to < 6.5%) between treatment groups. However, the 14-d full-dose teplizumab group showed improvement in β-cell preservation (delaying loss of insulin secretion), particularly in specific populations tested, including the U.S. patients and young children aged 8–11. Taken together, it appears that anti-CTLA-4 and anti-CD3 help preserve β-cell function in patients with recent-onset T1DM (the loss of insulin secretion was delayed about 9 months with CTLA-4 and about 16 months with anti-CD3 full therapy); however, the effect was insufficient to reverse disease. This raises the question whether these immunotherapies could be more effective if instituted before disease onset. Certainly, new biomarkers for detection of the early stages of T1DM, before the development autoantibodies, are needed for these and other prevention trials.

Fig. 3.

Delayed decline in C-peptide AUC with abatacept in young patients recently diagnosed with T1DM. Population mean of stimulated C-peptide 2-h AUC mean over time for each treatment group. The estimates are from the analysis of covariance model adjusting for age, sex, baseline value of C-peptide, and treatment assignment. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. [Reproduced from T. Orban et al.: Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 378:412–419, 2011 (21), with permission. © Elsevier.]

On the horizon

Investigating mechanisms of obesity and T2DM: the role of the brain

Data have accumulated in recent years, suggesting that there may be biological drivers of obesity; specifically, whether differences in brain biology in obese individuals may result in differences in eating behaviors (23, 24). Indeed, peripheral glucose levels have been found to influence neural responses in motivation-reward brain regions in response to visual food cues differently in obese and lean individuals. In both lean and obese individuals, mild hypoglycemia (BG, ∼67 mg/dl) has recently been reported to increase activation in striatal-limbic (motivation and emotion) brain regions, and in turn increase craving for foods (23). In lean individuals, euglycemia (BG, ∼92 mg/dl) increased activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (executive control) and resulted in less food craving; meanwhile, obese individuals did not demonstrate increased prefrontal cortex activation with euglycemia, suggesting that obese subjects may have less executive control over the desire for food at a normal BG level. These findings provide evidence that modest changes in BG levels modulate central nervous system (CNS) control over motivation for food and suggest a loss of the glucose-related restraining influence in obesity (23). Another study investigated whether differences in activation of reward-motivation neural pathways are acquired or predetermined. Lean adolescents of two obese parents were found to demonstrate greater activation in the striatum in response to receipt of palatable food, compared with lean adolescents of two lean parents (25). Thus, the risk of future obesity may be driven by early-onset changes in the susceptibility of motivation/reward neuronal circuits to food cues and taste. Based on these and other recent studies (23–25), it is intriguing to speculate that biological alterations involving the CNS are likely affecting eating behaviors and the current obesity epidemic.

With regard to diabetes, traditionally it has been thought that this disease arises from the combined effects of impaired pancreatic insulin secretion and insulin resistance in classical target tissues. It is now becoming recognized that insulin resistance is also associated with changes in the CNS, which likely contribute to the pathogenesis of T2DM. Interestingly, targeted insulin-receptor knockout in muscle and fat of mice is not sufficient to cause diabetes (26). However, when insulin receptors are also knocked out of glucose transporter 4-expressing neurons (which are particularly expressed in subcortical and hypothalamic regions) some of these mice develop florid diabetes, suggesting that central insulin resistance might be an important driver of diabetes development (26). To investigate this concept further, insulin receptors were selectively reduced in the ventral medial hypothalamus using a gene knockdown approach in lean, nondiabetic adult rats (27). The ventral medial hypothalamus insulin receptor knockdown rats developed insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and increased glucagon levels and demonstrated a 40–50% reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Intriguingly, all of this occurred in the absence of weight gain. Although, of course, there are no direct human data, as in the knockout and knockdown animals, with regard to CNS insulin receptors, there is evidence that insulin resistance in the brain occurs in the setting of peripheral insulin resistance in humans (28). Based on these and other studies (26, 27, 29), it seems likely that the brain remarkably plays a much more significant role in the development of diabetes and obesity than has previously been imagined. Taken together, these studies may have important therapeutic implications for both obesity and diabetes. If indeed the brain has a significant role in the development of these important health problems, then novel therapeutic or preventive interventions will need to take into account potential new targets in the CNS.

A new treatment: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors for the pharmacotherapy of T2DM

In April 2012, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency issued a positive opinion on dapagliflozin, the first in class of the SGLT-2 inhibitors (30). These medications inhibit the SGLT-2 in proximal renal tubules, which account for more than 90% of glucose reabsorption by the kidneys (31). Blockade of this transporter causes dose-dependent glucosuria and the lowering of BG (31). Additionally, dapagliflozin may contribute to weight loss by inducing urinary glucose loss (32). The medication's most common side effects are hypoglycemia (when used with sulfonylurea or insulin), dyslipidemia, dysuria, polyuria, genital or urinary tract infection, and gastrointestinal side effects (23–26). Because of concerns regarding increased incidence of bladder and breast cancer in trials (33, 34), the drug has not been granted approval in the United States. Notably, there are several other SGLT-2 inhibitors currently in phase III trials, including empagliflozin and canagliflozin. Certainly, long-term studies of potential adverse effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors are needed; however, this class of medications offers potential benefits for a wide spectrum of diabetic patients.

A new biomarker: detection of early stage T1DM

As described, immunotherapies have been found to delay the decline of β-cell function in patients with recent-onset T1DM; however, the effect of these interventions has been insufficient to reverse disease progression. Thus, it is important to consider whether these immunotherapies would be more effective if instituted before disease onset. New biomarkers for detection of early stage T1DM, before the development autoantibodies, are in development and will hopefully enable earlier interventions. One potential new approach to address this issue uses magnetic nanoparticles. The magnetic nanoparticle, ferumoxtran 10, is an ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide, which readily crosses leaky endothelial cells and is internalized by resident phagocytes (such as monocytes, macrophages, and oligodendroglial cells) (35) and can be imaged using magnetic resonance imaging (36). Two days after systemic injection of ferumoxtran 10, the nanoparticles accumulate in immune cells that are detected in pancreatic islets of individuals with T1DM (36). Further development of such novel techniques may enable earlier detection of islet-autoimmunity in T1DM, thereby enabling earlier interventions with immunosuppressive medications. This is essential for future preventative measures, such as antidiabetes vaccines.

A new hormone: irisin

In January 2012, the Spiegelman lab (37) published a manuscript in Nature describing a new polypeptide hormone, which they named irisin, for Iris, the messenger goddess of Greek mythology (38). Briefly, exercise stimulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) coactivator-1 α expression in muscle, has been found to have beneficial effects on muscle mitochondria, facilitating cellular metabolism (39). Subsequently, PPAR-γ coactivator-1 α stimulates the expression of the Fndc5, a gene that encodes a type 1 membrane protein which, when cleaved from the membrane, is released into circulation as the polypeptide irisin (37). When irisin is overexpressed in animals overfed with a high-fat diet, there is an increase in uncoupling protein 1, browning of adipose tissue, an increase in oxygen consumption, small decreases in body weight, and improved glucose tolerance. Thus, irisin provides a signal that alters adipose cell biology, leading to increased rates of energy expenditure. It is intriguing to speculate that irisin-like compounds may become therapeutic targets for human metabolic diseases, such as obesity and T2DM. Perhaps this hormone might serve as the chemical means to derive some of the metabolic benefits of exercise.

Conclusion

Today's message is that a diabetes tsunami is rapidly approaching. The number of children and adolescents with diabetes is increasing at rates never before seen, and the capacity of current therapeutic interventions to slow its progression in youth appears to be very limited. Our relative failure to effectively manage diabetes, once it develops, underscores the need to minimize the imminent damage by creating an early warning system to protect those in its path and to focus on disease prevention. To accomplish this goal, we will need to: 1) better understand the basic biology of both obesity and diabetes, including the brain-obesity-diabetes connection; 2) create better biomarkers for the early detection of both T1DM and T2DM in high-risk individuals to enable β-cell preservation early in disease progression or, ideally, before disease onset; and 3) use this information to develop, through research and public policy efforts, more effective and timely lifestyle and therapeutic interventions for both diabetes and obesity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R37-DK20495 and K12-DK094714 and by Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant UL1-RR024139 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science.

Disclosure Summary: R.S. has provided consultation for Janssen Pharmaceutical, Merck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Pfizer Inc., U.S. Pharmaceuticals Group, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Mannkind, and McKinsey. A.M.J. assists ManPower who provides contractors for the Pfizer New Haven Clinical Research Unit.

Footnotes

- AUC

- Area under the curve

- BG

- blood glucose

- CNS

- central nervous system

- DPP-4

- dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- FPG

- fasting plasma glucose

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide-1

- HbA1c

- glycated hemoglobin

- NGT

- normal glucose tolerance

- RYGB

- Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- SGLT-2

- sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

- T1DM

- type 1 diabetes

- T2DM

- type 2 diabetes

- TZD

- thiazolidinedione.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization 2011. World Health Organization: diabetes fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/index.html

- 3. American Diabetes Association 2008. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care [Erratum (2008) 31:1271] 31:596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012. Diabetes data and trends. Data from the National Health Interview Survey. Statistical analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Diabetes Translation. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/prev/national/figage.htm

- 5. May AL, Kuklina EV, Yoon PW. 2012. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adolescents, 1999–2008. Pediatrics 129:1035–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. 2012. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 35:1364–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, Peters AL, Tsapas A, Wender R, Matthews DR. 2012. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 55:1577–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, Segal JB, Wilson LM, Chatterjee R, Marinopoulos SS, Puhan MA, Ranasinghe P, Block L, Nicholson WK, Hutfless S, Bass EB, Bolen S. 2011. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med 154:602–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amylin Pharmaceuticals 2012. Byetta (exenatide) Injection and Bydureon (excenatide extended-release for injectable suspension). U.S. fact sheet [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, Kosiborod M, Maynard GA, Montori VM, Seley JJ, Van den Berghe G. 2012. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:16–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. 2002. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perreault L, Pan Q, Mather KJ, Watson KE, Hamman RF, Kahn SE. Effect of regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation on long-term reduction in diabetes risk: results from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 379:2243–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, Díaz R, Jung H, Maggioni AP, Pogue J, Probstfield J, Ramachandran A, Riddle MC, Rydén LE, Yusuf S. 2012. Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med 367:319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, Nanni G, Pomp A, Castagneto M, Ghirlanda G, Rubino F. 2012. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 366:1577–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, Thomas S, Abood B, Nissen SE, Bhatt DL. 2012. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 366:1567–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah M, Simha V, Garg A. 2006. Long-term impact of bariatric surgery on body weight, comorbidities, and nutritional status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4223–4231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C. 2010. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:4823–4843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Inge TH, Krebs NF, Garcia VF, Skelton JA, Guice KS, Strauss RS, Albanese CT, Brandt ML, Hammer LD, Harmon CM, Kane TD, Klish WJ, Oldham KT, Rudolph CD, Helmrath MA, Donovan E, Daniels SR. 2004. Bariatric surgery for severely overweight adolescents: concerns and recommendations. Pediatrics 114:217–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeitler P, Hirst K, Pyle L, Linder B, Copeland K, Arslanian S, Cuttler L, Nathan DM, Tollefsen S, Wilfley D, Kaufman F. 2012. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 366:2247–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amiel SA, Sherwin RS, Simonson DC, Lauritano AA, Tamborlane WV. 1986. Impaired insulin action in puberty. A contributing factor to poor glycemic control in adolescents with diabetes. N Engl J Med 315:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orban T, Bundy B, Becker DJ, DiMeglio LA, Gitelman SE, Goland R, Gottlieb PA, Greenbaum CJ, Marks JB, Monzavi R, Moran A, Raskin P, Rodriguez H, Russell WE, Schatz D, Wherrett D, Wilson DM, Krischer JP, Skyler JS. 2011. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 378:412–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sherry N, Hagopian W, Ludvigsson J, Jain SM, Wahlen J, Ferry RJ, Jr, Bode B, Aronoff S, Holland C, Carlin D, King KL, Wilder RL, Pillemer S, Bonvini E, Johnson S, Stein KE, Koenig S, Herold KC, Daifotis AG. 2011. Teplizumab for treatment of type 1 diabetes (Protégé study): 1-year results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 378:487–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Page KA, Seo D, Belfort-DeAguiar R, Lacadie C, Dzuira J, Naik S, Amarnath S, Constable RT, Sherwin RS, Sinha R. 2011. Circulating glucose levels modulate neural control of desire for high-calorie foods in humans. J Clin Invest 121:4161–4169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jastreboff AM, Sinha R, Lacadie C, Small DM, Sherwin RS, Potenza MN. 15 October 2012. Neural correlates of stress- and food-cue-induced food craving in obesity: association with insulin levels. Diabetes Care 10.2337/dc12-1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. 2011. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. J Neurosci 31:4360–4366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin HV, Ren H, Samuel VT, Lee HY, Lu TY, Shulman GI, Accili D. 2011. Diabetes in mice with selective impairment of insulin action in Glut4-expressing tissues. Diabetes 60:700–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paranjape SA, Chan O, Zhu W, Horblitt AM, Grillo CA, Wilson S, Reagan L, Sherwin RS. 2011. Chronic reduction of insulin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamus produces glucose intolerance and islet dysfunction in the absence of weight gain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301:E978–E983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anthony K, Reed LJ, Dunn JT, Bingham E, Hopkins D, Marsden PK, Amiel SA. 2006. Attenuation of insulin-evoked responses in brain networks controlling appetite and reward in insulin resistance: the cerebral basis for impaired control of food intake in metabolic syndrome? Diabetes 55:2986–2992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sandoval DA, Obici S, Seeley RJ. 2009. Targeting the CNS to treat type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:386–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) 2012. Summary of opinion (initial authorisation): Forxiga (dapagliflozin). London: European Medicines Agency [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nair S, Wilding JP. 2010. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors as a new treatment for diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. List JF, Woo V, Morales E, Tang W, Fiedorek FT. 2009. Sodium-glucose cotransport inhibition with dapagliflozin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:650–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burki TK. 2012. FDA rejects novel diabetes drug over safety fears. Lancet 379:507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones D. 2011. Diabetes field cautiously upbeat despite possible setback for leading SGLT2 inhibitor. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10:645–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leung K. 2004. Ferumoxtran. Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD). 2004–2012. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK23402/ date accessed: September 16, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gaglia JL, Guimaraes AR, Harisinghani M, Turvey SE, Jackson R, Benoist C, Mathis D, Weissleder R. 2011. Noninvasive imaging of pancreatic islet inflammation in type 1A diabetes patients. J Clin Invest 121:442–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Boström EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Højlund K, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. 2012. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 481:463–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reynolds G. 2012. Exercise hormone may fight obesity and diabetes. New York Times, January 11, 2012; http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/11/exercise-hormone-helps-keep-us-healthy/

- 39. Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. 2003. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev 24:78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]