Abstract

Schistosomiasis is one of the foremost health problems in developing countries and has been estimated to account for the loss of up to 56 million annual disability-adjusted life years. Control of the disease relies almost exclusively on praziquantel (PZQ) but this drug does not kill juvenile worms during the early stages of infection or prevent post-treatment reinfection. As the use of PZQ continues to grow, there are fears that drug resistance may become problematic thus there is a need to develop a new generation of more broadly effective anti-schistosomal drugs, a task that will be made easier by having an understanding of why PZQ kills sexually mature worms but fails to kill juveniles. Here, we describe the exposure of mixed-sex juvenile and sexually mature male and female Schistosoma mansoni to 1 μg/mL PZQ in vitro and the use of microarrays to observe changes to the transcriptome associated with drug treatment. Although there was no significant difference in the total number of genes expressed by adult and juvenile schistosomes after treatment, juveniles differentially regulated a greater proportion of their genes. These included genes encoding multiple drug transporter as well as calcium regulatory, stress and apoptosis-related proteins. We propose that it is the greater transcriptomic flexibility of juvenile schistosomes that allows them to respond to and survive exposure to PZQ in vivo.

Keywords: Schistosomiasis, schistosoma, praziquantel, microarray, drug resistance, apoptosis

1. Introduction

In terms of global public health, schistosomiasis is probably the single most important water borne disease. By 2003, more than 207 million people were estimated to be infected with Schistosoma spp [1] with a global disease burden recently calculated at between 24 and 56 million disability-adjusted life-years lost [2]. The list of drugs that treat the disease is limited, with praziquantel (PZQ) being the only one that is widely available, relatively cheap and effective against all Schistosoma spp known to infect humans [3].

The anthelmintic properties of PZQ were first reported in 1975 and the drug made available in 1978 (reviewed by [4]). Although highly effective against sexually mature schistosomes in vivo, studies using S. mansoni infected experimental mammals [5,6] as well as in vitro studies [7,8] show that PZQ does not kill 28-day post infection (d.p.i) juvenile schistosomes readily. In addition, Pica-Mattoccia and Cioli have demonstrated that mature (day 49 d.p.i) male schistosomes may by more susceptible than mature females when both are derived from mixed sex mouse infections and exposed to the drug in vitro [7]. This group also showed that, compared to their counterparts derived from mixed-sex infections, males and females had diminished susceptibility to the drug at day 49 d.p.i. when derived from single-sex infections. Despite its long history of clinical and veterinary use, the mechanism of action of PZQ remains poorly defined, as does the reason for its differing efficacy against juvenile and mature worms. Suggested mechanisms of action have included the disruption of ion transport, [9-11], alteration of schistosomal membrane fluidity [12], inhibition of phosphoinositide turnover [13], reduction of schistosomal glutathione concentration [14] and inhibition of nucleoside uptake [15] while specific molecular targets have included myosin light chain [16] and actin [16,17]. None of these proposed modes of action easily explain the differential effects of PZQ on juvenile and mature schistosomes and none have ever been proven definitively.

The present study was carried out to examine the effect of PZQ on the transcriptome of juvenile and mature male and female worms in vitro. Our aim was to gain insights as to why juvenile worms are spared the anthelmintic effects of PZQ and, at the same time, understand which molecular processes may be active in killing mature worms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Schistosoma mansoni

All animal experimentation complied with the policies, regulations and guidelines mandated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of New Mexico.

Schistosome-infected Swiss Webster mice were supplied by Dr. Fred A. Lewis, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) Schistosomiasis Resource Center at the Biomedical Research Institute (Rockville, MD, USA). Worms were harvested by perfusion with RPMI 1640 with Glutamine (Invitrogen, USA) at 28 and 42 d.p.i. Sexually mature male and female worms (42 d.p.i.) were selected by visual inspection after seperation. All juvenile worms (28 d.p.i.) used were of mixed sex. Prior to each experiment, worms were allowed to recover overnight in enriched RPMI 1640 containing 20 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, USA) and 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, USA) at 37 °C. This and all subsequent procedures that required worms to be maintained at 37 °C were performed using a water-jacketed incubator with 5 % CO2.

2.2. Transcriptomic response of S. mansoni to PZQ

Groups of up to 30 juvenile or mature male or female worms were exposed to 1 μg/mL PZQ in 1 % DMSO or 1 % DMSO alone for 1 or 20 h at 37 °C. Schistosomes were harvested immediately after exposure and each group placed in separate 1.5 mL tubes with 600 μL of RLT Buffer (Qiagen, USA) containing 1 % β-mercaptoethanol, homogenized and stored at −80 °C prior to RNA extraction. Each treatment was performed in triplicate.

2.2.1 Total RNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated from the thawed worm preparations using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, eluted with RNase-free distilled water and quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer with ND-1000 3.3 software (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA). RNA integrity was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with a RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, USA).

A reference RNA sample was generated to assist in the normalization of the microarray data [18]. This sample was derived from mature schistosome total RNA supplemented with 0.5 % RNA isolated from mature worms exposed to 1 μg/mL PZQ, 0.5 % RNA isolated from juvenile worms exposed to 1 μg/mL PZQ and 0.5 % RNA isolated from juvenile worms not exposed to PZQ. Spike-in controls (Agilent Technologies, USA) were prepared for signal standardization according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.2.2. Complementary RNA preparation and hybridization to microarrays

Complementary RNA (cRNA) synthesis, amplification and labeling were performed using the Two-Color Low Input Quick Amp Labeling kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Experimental and reference samples were labeled with Cy-5 and Cy-3 (Invitrogen, USA) respectively and combined prior to purification using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, USA). At this stage, only samples meeting the manufacturer’s suggested minimum activity for hybridization were processed further.

The oligonucleotide microarrays used in these studies were designed and described by Gobert et al. [19] and obtained from Agilent Technologies. Each slide has 12,166 S. mansoni features per array with 4 arrays per slide. Technical replicates were always performed on different slides.

Fragmented Cy3/5 labeled cRNA was hybridized to individual arrays in a rotating oven at 65 °C and 10 r.p.m. for 17 h. After hybridization, the slides were washed and stabilized against ozone deterioration in stabilization buffer (Agilent Technologies, USA). The slides were then scanned and extracted using Agilent’s Feature Extraction software by the University of California San Francisco’s Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center, China Basin.

2.2.3. Microarray data analysis

Array data were analyzed using GeneSpring GX version 11 software. Following a baseline transformation to the median of the control for each experimental grouping, features that were not positive, not significant, not above background noise, not uniform, saturated or a population outlier were not considered for analyse s. Only features with a signal in all three replicates for each experimental group were retained and averaged. The signal from these groups was log2 transformed. Analyses of significance compared the PZQ-exposed groups to the control in each grouping using an unpaired, unequal variance t-test. Significant features had to have a p-value < 0.05.

All microarray information contained in this paper is MIAME compliant (http://www.mged.org/Workgroups/MIAME/miame.html) and all data were submitted to Gene Express Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE29535.

2.2.4. Transcript identification

The expressed sequence tag that each array oligonucleotide was designed to represent was accessed through the S. mansoni Genome Index (compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/tgipage.html) and queried using NCBI’s BLASTX program with both the Swissprot and Non-redundant protein sequence databases (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) as well as the KEGG (www.genome.jp) and GO (www.geneontology.org) databases. In addition, GO term associations for each oligonucleotide were generated. Only blast results with an Expect value < 1e-05 were accepted. The four blast results for each feature along with the GO terms and Entrez Gene ID numbers were placed into Excel spreadsheets where they could be searched for specific terms.

2.3. Real-Time PCR

Complimentary DNA was synthesized in a 20 μL reaction according to manufacturer’s specifications using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, USA) with the kit’s anchored-oligo(dT) primer and 100 ng of RNA template derived from the samples generated as described in section 2.2. cDNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer with ND-1000 3.3 software.

Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed to manufacturer’s specifications using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master kit (Roche, USA) on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA). For each treatment, technical duplicates of each biological triplicate were tested. The primer sequences (Table 1) were generated using both Primer3Plus (www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/primer3plus/primer3plus.cgi) and Integrated DNA Technologies OligoAnalyzer tools (www.idtdna.com).

Table 1.

Real-time PCR primers

| Array feature |

Gene annotation | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC7600 | Ferritin | TGTCAATGGAGAAGGCAGTG | TGACCAAGTCCACTTCCAAC |

| TC7830 | AGAT | TGGATTGGGATTTCCTTACGAAG | TGATTGCTTCTGCTGTGAGG |

| TC9859 | SmMRP2 (ABCC1) | TTATGGCGTGCAATAGAATCTG | AGATTTGCTCCACCTTCACC |

| TC9950 | ABCG1 | GTTTAGTCCCTTACCTCGCATC | ATTCACCACAAGCCACTTCC |

| TC10285 | SmBRCP2 (ABCG2) | GCAGCCCTACGAATGACTATG | CCAACCTTACTATCCGCTACAG |

| TC11991 | Dynamin | TGAAGGAACAGATGCACAGG | TCTACGTTCGGCTTCCAAAG |

| TC14236 | SMDR3 (ABCB1) | GGAGTTGAAACGATACCGAGAG | GCAGTAGAACAAAACACAGTCAG |

| TC14689 | SmMDR2 (ABCB1) | CTAGTCGGTTCTAGTGGTTCTG | GAGCATTAGCTTTGATGGCAG |

| TC14697 | Syntenin | CCACTTCCAGCACCATTCG | GTGAAAACCCCTCCACAAATG |

| TC16575 | Heat shock protein | ACTTAATCGGACCATACACGG | GCAAACATTCCACGTCTCAAAC |

| TC16678 | SmGAPDH | GTCATTCCAGCACTAAACGG | CCTTCCCTAACCTACATGTCAG |

| SmMRP1 (ABCC1)a | GCTATTTGGCACGCACTTG | AGCCACCTTCTGAGATGTTC | |

| SMDR1 (ABCB8)a | CTTATTCGGTGCCATTCTGG | TTCGTGAGTCACAACGCATC |

Neither SmMRP1 nor SMDR1 were represented on the array

Real-Time PCR data was first standardized with ABI Prism 7000 SDS software by manual adjustment of the threshold and baseline. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were then exported to Excel spreadsheets where the technical duplicates for each treatment were averaged and the values of the three biological replicates analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method [20] to obtain the relative expression ratio between the target genes and the endogenous control, S. mansoni glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (TC16678). Expression of these normalized transcripts for each treatment were expressed as a mean ± 1 standard deviation and the values of appropriate PZQ and DMSO control groups compared using an unpaired student’s t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Fold change was expressed as the ratio of the mean normalized expression for each PZQ treatment group to that of the appropriate DMSO treated control.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Transcriptional profile of S. mansoni treated with PZQ

The experiments described below compare the transcriptomic profiles of juvenile and adult worms treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ in vitro. The juvenile cohort used was of mixed gender as it is not feasible to separate the sexes at this stage of development based on morphology in the numbers required for these experiments. Adult pairs were separated into males and females as this allowed a comparison of the differences in expression between the least (juvenile) and most (adult male) PZQ sensitive stages [7]. Clearly, this does not allow a completely accurate comparison due to the gender mix of the juveniles; however, we have no reason to believe that the sexes have a differential insensitivity to the drug at this life cycle stage.

In selecting treatment regimes for transcriptome analysis, exposure to 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 or 20 h was chosen for two reasons. Firstly, preliminary experiments suggested that these regimes did not result in any significant numbers of worm deaths that might confound the Secondly, array data (data not shown). exposure to 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 h is very close to the maximum serum concentration of the non-metabolized drug and length of time that this concentration is maintained in humans receiving a clinically relevant dose of the drug [21]. In addition, a 20 h exposure time was employed to exacerbate the PZQ induced transcriptomal response with the aim of maximizing the number of differentially regulated genes detected. As adult female schistosomes are less robust than the males the amount of total RNA and therefore the number of replicate groups that could be generated with these worms was limited. Thus, only the effect of PZQ on transcriptomal changes over 20 h was assessed in adult females using microarrays.

When the number of genes being expressed in each treatment and control group was assessed, the least number (7458) were expressed in the juvenile 20 h DMSO treated control group while the greatest (8332) was in adult males exposed to PZQ for 20 h (Table 2). There was no correlation between the number of genes expressed and treatment regime. No more than 18 features in any control group showed more than a ±2-fold change in expression compared to the reference sample (Table 2). This is significantly fewer than in PZQ treated schistosomes suggesting that very little of the observed variation in the drug treated samples was due to technical differences in sample handling.

Table 2.

Total and differential gene expression in control and PZQ treated S. mansoni

| S. mansoni | PZQ (μg/mL) |

Exposure time (h) |

Total No. of expressed genes |

Total No. of expressed genes showing fold change >±2a |

Total No. of significantly differentially expressed genes (p < 0.05)b |

Total No. of significantly induced genes (p < 0.05)b |

Total No. of significantly down-regulated genes (p < 0.05)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28M+F | 0c | 1 | 8033 | 18 | - | - | - |

| 28M+F | 1 | 1 | 7671 | 87 | 1329 | 736 | 593 |

| 28M+F | 0 | 20 | 7458 | 8 | - | - | - |

| 28M+F | 1 | 20 | 7483 | 868 | 3482 | 1627 | 1855 |

| 42M | 0 | 1 | 7689 | 0 | - | - | - |

| 42M | 1 | 1 | 7685 | 42 | 208 | 58 | 150 |

| 42M | 0 | 20 | 7900 | 4 | - | - | - |

| 42M | 1 | 20 | 8332 | 66 | 1393 | 764 | 628 |

| 42F | 0 | 1 | ND | ND | - | - | - |

| 42F | 1 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 42F | 0 | 20 | 8057 | 1 | - | - | - |

| 42F | 1 | 20 | 7769 | 41 | 1223 | 613 | 610 |

The number of genes showing at least a 2-fold increase or decrease in expression compared to the reference sample.

The number of genes that were significantly differentially expressed (p<0.05) in S. mansoni after PZQ treatment compared to those treated with DMSO.

Control groups received an equivalent volume of DMSO as the PZQ treated groups. 28M+F refers to the 28 d.p.i mixed sex schistosomes; 42M refers to the 42 d.p.i male schistosomes and 42F refers to the 42 d.p.i female schistosomes.

Treatment with PZQ resulted in the significant differential expression of array features in all treatment groups compared to DMSO treated controls ranging from just 208 features in mature males treated with PZQ for 1 h to 3482 features in juveniles treated with PZQ for 20 h (Table 2). Treatment of juvenile schistosomes with PZQ for 1 h significantly altered the response of at least 6-fold more genes than in mature males treated in the same way. Similarly, treatment of juveniles with PZQ for 20 h resulted in approximately 2.5-fold more differentially regulated features than observed in the adult males or females. to PZQ exposure Thus, the trend in this data set is that PZQ insensitive juvenile schistosomes respond in vitro by altering the expression of significantly more genes than their sexually mature PZQ sensitive counterparts. The degree of overlap between the different groups of genes responding to each treatment was evaluated next.

The number of shared genes that were induced or down regulated when comparing any two treatment groups (but not, for example induced in one treatment and down-regulated in its comparator group) ranged from 12 – 85 % of the total number of differentially regulated genes (Table 3). For example, juvenile and adult female schistosomes exposed to PZQ for 20 h differentially regulated an overlapping set of 635 genes. Of these, 541 (85 %) were either commonly induced or down-regulated by both groups leaving only 94 genes that were induced in one group and down – regulated in the other. Conversely, a comparison of juveniles and mature males treated with PZQ for 20 h produced a cohort of 658 genes that were differentially regulated by both groups with only 125 (19 %) commonly induced or down-regulated. Thus, treatment of juveniles and mature females with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 20 h produces a similar transcriptomic signature, but this signature is greatly diminished when mature males are treated with the drug for the same time. The data also reveal that juvenile schistosomes exposed to PZQ for 1 h have only 38 genes that are commonly differentially regulated when compared with mature males treated in the same way. Of these, 23 are commonly induced or down-regulated. Summarizing the data presented in Tables 2 and 3, we observe that juveniles and adults treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 or 20 h express a similar number of genes (Table 2), that the number of genes that are significantly differentially expressed in juveniles is significantly higher (Table 2), and that the magnitude (ie the number of genes) of the overlap in the response between PZQ insensitive juveniles and sensitive mature males is minimal (Table 3). This greater apparent transcriptomic flexibility may allow juveniles exposed to a clinical drug dose to survive PZQ’s lethal effects while mature male worms succumb. In addition, these observations may in part underlie the approximately two-fold reduction in effectiveness of the drug in vitro on adult females compared to males [7]. Interestingly, only 77 of 625 genes (12%) were commonly regulated between the two juvenile groups and we discuss this observation further below.

Table 3.

Overlap in genes differentially expressed as a result of treatment with 1 μg/mL PZQ

|

S. mansoni and length of PZQ exposure |

28M+F 1 h |

28M+F 20 h |

42M 1 h |

42M 20 h |

42F 20 h |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of differentially regulated genes |

1329 | 3482 | 208 | 1393 | 1223 | |

| 28M+F 1 h |

1329 | 625 | 38 | 231 | 166 | |

| 28M+F 20 h |

3482 | 77 (12) | 74 | 658 | 635 | |

| 42M 1 h |

208 | 23 (61) | 62 (84) | 32 | 29 | |

| 42M 20 h |

1393 | 66 (29) | 125 (19) | 18 (56) | 340 | |

| 42F 20 h |

1223 | 74 (32) | 541 (85) | 19 (66) | 69 (20) |

Values in bold represent the total number of differentially regulated genes that were common to the two groups being compared. Values in italics represent the number of genes that were common to the two groups being compared and which were either commonly induced or down regulated in both groups. Values in brackets represent the number of genes that are commonly induced or down-regulated expressed as a percentage of the total number of differentially regulated genes. 28M+F refers to the 28 d.p.i mixed sex schistosomes; 42M refers to the 42 d.p.i male schistosomes and 42F refers to the 42 d.p.i female schistosomes.

3.2. Validation of microarray data

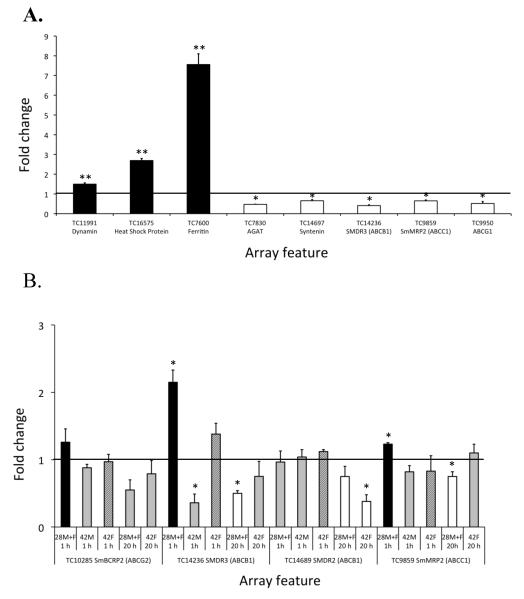

RT-PCR was employed to validate the gene expression data obtained from the microarray analyses and was performed on transcripts expressed by 10 genes. Of the initial group of eight genes tested, three were chosen because the array data suggested that they were significantly and differentially induced (array features TC7600, TC16575 and differentially down-regulated (TC7830, TC9859, TC9950, TC14236 and TC14697) in juvenile worms treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 20 h compared to the appropriate controls (Fig 1A). All gene transcripts tested showed statistically significant induction or down-regulation in RT-PCR that was in agreement with the array data. The expression of TC9859 TC11991) and 5 because they were significantly and and TC14236 as well as 2 additional genes (TC10285 and TC14689) in juvenile and adult worms treated with PZQ for 1 or 20 h was also analyzed (Fig. 1B). Again, there was broad agreement between the microarray and RT-PCR data. Only 2 of 16 data points for which there was corresponding microarray data demonstrated a conflicting result between assays. Microarray data suggested that feature TC10285 was marginally but significantly induced following treatment of juveniles with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 h but this was not borne out by RT-PCR. On the other hand, TC14689 was significantly down-regulated after 20 h treatment as assessed by array analysis but not RT-PCR. The genes shown in Fig 1B were selected for RT-PCR analysis as they encode multidrug resistance proteins that may play a role in removing PZQ from schistosome cells, thus lessening its efficacy. This aspect of the data will be discussed in more detail in section 3.3.2 below. Overall, however, we found that the array data were well supported by RT-PCR.

Fig. 1. RT-PCR expression data for S. mansoni treated with PZQ.

A. The mean change in expression (fold change) of 8 array features in transcripts derived from juveniles treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 20 h compared to the appropriate DMSO treated control. B. The change in mean expression (fold change) of 4 array features in juvenile (28M+F), adult male (42M) and adult female (42F) worms over the 4 treatment regimes indicated on the x-axis. A fold change of >1 indicates an increase in transcript abundance. In each figure (∎) indicates features that were significantly induced in the corresponding microarray analysis, (◻) indicates features were significantly down-regulated, ( ) indicates features that were not differentially expressed and (

) indicates features that were not differentially expressed and ( ) indicates female worms for which there was no microarray data. Statistical differences in fold change between normalized PZQ and DMSO treated samples were assessed and significant outcomes indicated above each bar by an asterix (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01). All error bars represent +1 standard error of the mean.

) indicates female worms for which there was no microarray data. Statistical differences in fold change between normalized PZQ and DMSO treated samples were assessed and significant outcomes indicated above each bar by an asterix (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01). All error bars represent +1 standard error of the mean.

3.3. Analysis of gene expression

In order to gain a more detailed insight into the differential sensitivity to PZQ of juvenile and mature schistosomes, the effect of the drug on the expression of specific genes was analyzed using two approaches. Initially, a broad examination of those genes that underwent the most extreme degree of differential regulation was performed. This was followed by an analysis of much narrower scope that focused on groups of genes that are potentially pertinent to the differential effect of PZQ.

3.3.1. Extreme differential gene expression

The selection of a microarray feature as being ‘extremely’ differentially regulated was arbitrarily set at a differential level of expression of a ±5-fold change in at least one treatment group relative to the same feature in the appropriate untreated control (Table 4). All 20 of the features selected belong to the juvenile 20 h treatment group and all of the selected genes showed induction. None of these features showed extreme expression in the mature male or female treatment groups. Together, these data underpin our previous observation that there is a very different transcriptomal response in juveniles exposed to PZQ for 1 h compared to those exposed for 20 h (Table 2), and that juvenile responses differ from those of adults.

Table 4.

Extreme differentially regulated genes following treatment of S. mansoni with 1 μg/mL PZQ

| 28M+F | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ exposure time (h) | 1 | 20 | |

| Array feature | Homolog | ||

|

|

|||

| TC16575 | Hsp | 28.45a | |

| TC13647 | Splice leader | −2.80 | 21.38 |

| TC15710 | Hsp interacting protein | 19.20 | |

| TC7164 | Hypothetical protein | −4.16 | 17.54 |

| TC17814 | Merlin | 14.41 | |

| TC8197 | Hsp70-interacting protein | 11.67 | |

| TC18298 | Unknown | 9.62 | |

| TC18423 | Unknown | 7.69 | |

| TC7600 | Ferritin | −2.47 | 7.44 |

| TC11284 | SAM domain containing protein | 7.16 | |

| TC16585 | Hsp70 | 2.24 | 6.70 |

| TC15413 | Integrator 6 subunit | 6.67 | |

| TC18105 | Putative NC2 | 6.38 | |

| TC14611 | Rab6-interacting protein | 6.08 | |

| TC12603 | Suppressor of MAP2K1 | 6.06 | |

| TC16220 | Cytohesin-related GNEP | 5.82 | |

| TC18396 | Unknown | 5.36 | |

| TC7341 | Retrovirus Polymerase | 5.24 | |

| TC8843 | Unknown | 5.23 | |

| TC10177 | Hypothetical protein | 5.01 | |

Features were included if they showed a fold-change of > 5.00 or < −5.00 in at least one treatment group. Other data points associated with an extreme differentially regulated feature were included for comparison when fold-change was >2.00 or <−2.00. No features out with the juvenile treatment groups met these criteria. Hsp, Heat shock protein; SAM, Sterile alpha motif; NC2, Negative cofactor 2 transcriptional co-repressor; MAP2K1, Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 1; GNEP, Guanine nucleotide exchange protein

Of the 20 features selected, four had no hits in homology matching using BlastN analysis against the S. mansoni genome while another two features matched against hypothetical proteins. Using 454 sequencing and 5′ and 3′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) techniques, the relatively short sequences associated with these TC numbers could not be extended. Four of the sequences were heat shock or heat shock interacting proteins suggesting that relatively long-term exposure to PZQ may elicit a stress response in juvenile but not mature worms. Intriguingly, an array feature associated with a splice leader (SL) was the second most differentially regulated transcript showing a 21-fold induction in juveniles treated for 20 h but significant down-regulation in juveniles treated for 1 h. Splice leaders have been partially characterized in S. mansoni, however, genes that require the addition of an SL do not appear to share any functional characteristics that might explain the significance of the SL addition [22,23]. Davis et al. [23] suggested that trans splicing in flatworms is most likely associated with a property that is conferred on the mRNA or related to a characteristic of the primary transcript or transcription of trans-spliced genes rather than the proteins they encode.

3.3.2. Gene expression analysis

Analysis of the ESTs associated with each microarray feature provided annotation for 7507 expressed genes including 5501 that were significantly expressed. Here, for the sake of brevity, focus was placed on those groups of genes that may play a role in protecting juvenile worms from PZQ or in the downstream events that lead to PZQ initiated adult worm death.

ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC transporter) superfamily members are involved in a diverse array of cellular processes and play a central role in conferring multidrug resistance (MDR) on cells and organisms including helminths [24,25]. MDR transporters include P-glycoproteins (P-gp), multidrug resistance associated proteins (MRP) and breast cancer resistance proteins (BCRP). To date, three S. mansoni ABC transporters have been characterized; Bosch et al. [26] cloned two cDNAs encoding SMDR1 (belonging to the ABC transporter subfamily B8) and the P-gp homologue SMDR2 (represented by array feature TC14689 and belonging to the ABCB1 subfamily), while Kasinathan et al. [27] cloned a cDNA encoding the multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (SmMRP1; ABCC1). Kasinathan and Greenberg [28] identified genes encoding 14 additional ABC transporter sub-classes in the S. mansoni genome. Of this total of 17 sub-classes, 12 were represented on the microarray. Those whose homologues have previously been identified to play a role in drug transport included SMDR1, SMDR2, SmMRP1, a second MRP, named here as SmMRP2 (TC9859; ABCC1), two BCRP homologues named here as SmBCRP1 (TC8681; ABCG2) and SmBCRP2 (TC10285; ABCG2), and a second P-gp homologue, SMDR3 (TC14236; ABCB1). As neither SMDR1 nor SmMRP1 were represented on the array, RT-PCR was used to follow the expression of these genes as well as SmBCRP2, SMDR2, SMDR3 and SmMRP2 in each of the microarray treatment groups in addition to adult female worms treated with PZQ for 1 h (Figs. 1B and 2). A summary of the RT-PCR data suggests that, in agreement with the array data, juvenile worms treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 h had significantly elevated expression of SMDR1, SmMRP1, SmMRP2 and SMDR3 transcripts. SmBCRP2 transcript levels were significantly elevated in the array, but not the RT-PCR data. No assayed MDR genes were induced in adult males or females over either exposure interval though both SMDR3 (Fig 1B) and SMDR1 (Fig 2) were significantly down-regulated in males treated for 1 h when measured by RT-PCR. SMDR2 (Fig 1B) was down-regulated in adult females treated for 20 h. Kasinanthan et al. [28] used RT-PCR to show that juvenile worms express approximately 2.5-fold higher basal levels of SmMRP1 and SMDR2 mRNA than adults. They were also able to demonstrate a significant 2.7 and 1.8-fold induction of SmMRP1 RNA in adult mixed sex and mature males respectively following incubation with 100 nM (0.3 μg/mL) PZQ for 6 h. Messerli et al. [29] found a significant 3.4-fold increase in SMDR2 RNA after exposure of mature males to 100 nM PZQ for 3 h but not 24 or 48 h. Kasinathan et al. [30] have also shown that PZQ is an inhibitor and a substrate of SMDR2 and that both SMDR2 and SmMRP1 RNA levels are elevated in S. mansoni males and females derived from single sex infections compared to paired worms [28]. The latter is an important observation, as, like juveniles, such worms remain relatively insensitive to PZQ. Taken together, these data suggest that juveniles may have reduced sensitivity to 1 h exposure to PZQ in part due to the basal level and/or PZQ-inducible expression of a suite of MDR proteins including SMDR1, SMDR3, SmMRP1 and SmMRP2. Conversely, over 20 h, the expression of SMDR3, SmMRP1 and SmMRP2 are significantly reduced suggesting either a lesser role for these genes in worm survival over longer periods of drug exposure or a sufficiently high basal level of gene expression and/or MDR protein stability to render the drop in gene transcription harmless. This lowering of MDR activity in juveniles treated for 20 h compared to 1 h may help explain the extreme differential gene regulation, including the induction of stress response genes (Table 4) , seen in the former group as well as the fact that although the two groups shared a cohort of 625 genes in their response to PZQ only 77 (12%) were similarly induced or down-regulated (Table 3). While juveniles exposed to PZQ for 20 h have negligible death rates (< 5%) they may be close to their tolerable exposure limit. In support of this we have observed that 35 % of juveniles exposed to 10 μg/mL PZQ for 20 h die as a result (data not shown). Regarding the obvious potential for increased MDR gene expression to play a role in S. mansoni drug resistance, elevated SMDR1 or SMDR2 gene copy number or transcription levels were not associated with S. mansoni resistance to hycanthone or oxamniquine [26]; however, Messerli et al. [29] observed an increase in SMDR2 transcript and protein levels in an Egyptian S. mansoni isolate with reduced sensitivity to PZQ. Interestingly, Kasinathan et al. [31], using RNAi and pharmacological inhibitors, have demonstrated that MDR transporters play important roles in parasite egg production suggesting that these gene products might be targeted to relieve much of the disease pathology.

Fig. 2. RT-PCR expression data for SMDR1 and SmMRP1 transcripts in PZQ treated S. mansoni.

The change in mean expression (fold change) of normalized SMDR1 and SmMRP1 transcripts in juvenile (28M+F), adult male (42M) and adult female (42F) worms treated with 1 μg/mL PZQ for 1 or 20 h when compared with that of the appropriate DMSO treated controls is shown. A fold change of >1 indicates an increase in transcript abundance. Statistical differences in fold change between normalized PZQ and DMSO treated samples were assessed and significant outcomes indicated above each bar by an asterix (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01). All error bars represent +1 standard error of the mean.

Although PZQ has been used routinely in humans for many years, its precise mechanism of action has not been identified. A number of observations concerning the effects of the drug on schistosomes have, however, been reported. When juvenile or mature S. mansoni come into contact with PZQ they immediately undergo an intense muscular paralysis that is accompanied by a rapid influx of Ca2+ [9,32]. The notion that PZQ acts primarily through disruption of ion transport was given further credence by a series of experiments that suggested PZQ alters the function of a voltage-operated Ca2+ channel β subunit whose expression appears to be restricted to platyhelminths (reviewed by [10]). As cytosolic Ca2+ concentration plays such a central role in the control of a diverse array of eukaryotic cell functions and is, therefore, tightly regulated, the effect of the Ca2+ influx on genes with calcium related annotation was also examined. Juveniles exposed to PZQ for 1 or 20 h showed differential expression of up to 100 such genes while mature males exposed for 1 h expressed no more than 5 (data not shown). Clearly, these numbers reflect the overall differential transcriptomic response of juvenile and mature worms to PZQ. Again, as might be expected, a number of the genes that reacted to the influx were those whose products were directly responsible for Ca2+ transport or maintenance of cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis such as homologs of calmodulin (TC16813), neuronal calcium sensor protein (TC12133) and voltage gated calcium ion channel subunits (TC18129 and TC13171).

One significant impact of Ca2+ influx into eukaryotic cells is its role in promoting apoptosis (reviewed by [33,34]). Cells undergoing apoptosis can have a number of distinct morphological features, one of which is membrane blebbing, and a notable outcome of PZQ treatment is the vacuolation and blebbing of worm tegumental and subtegumental structures [35,36]. This has been suggested to disrupt the tegument and expose antigens on the parasite surface leading to the recognition and clearance of the parasite by the host immune system (reviewed by [37]). Xiao et al. [36] compared the in vitro effect of PZQ on the ultrastructure of juvenile and adult Schistosoma japonicum. While 10-30 μg/mL PZQ produced severe blebbing and damage to the mature tegument leading to the death of many worms, the same concentration of drug produced no or less blebbing and no deaths in the juvenile cohort. This suggests that, if vacuolation and blebbing are important to the lethality of PZQ, it may be the Ca2+ mediated differential expression of genes that regulate apoptosis that underlie the different responses of juvenile and mature worms to the drug. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the number of differentially regulated apoptosis regulatory genes was highest in juveniles. Those treated for 1 h had 44 differentially regulated apoptosis genes compared with 3 in the adult males while juveniles treated for 20 h differentially regulated 103 genes compared with 39 and 38 genes in the adult male and female groups respectively. This result may be explained simply by greater level of transcriptional activity in juveniles compared to adults with the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic genes therein being much more dynamic and responsive to treatment with the final outcome falling in favor of the anti-apoptotic response. For example, homologues of genes encoding inhibitors of apoptosis such as Programmed Cell Death 6 Interacting Protein (TC11843), Hepatitis B virus X-interacting protein (TC16195), Bcl2-associated athanogene-1 (TC14883) were induced after 20 h drug exposure while pro-apoptotic genes such as Death Associated Protein Kinase 1 (TC13214) were down regulated. In adults, the lack of this ability to transcriptionally respond to a pro-apoptotic Ca2+ influx may, on the other hand, lead to disruption of the tegument and exposure of the parasite surface antigens to the host immune system. This is clearly highly speculative and as preformed mediators play a major role in the execution of apoptosis, this line of inquiry will be best addressed by studying changes in juvenile and mature worm after exposure to PZQ using histochemical and proteomic analysis.

The results of these studies suggest that when exposed to PZQ, juvenile schistosomes are able to mobilize a transcriptomic response that may ultimately protects them from the fate of their mature counterparts. Why this should be the case remains unknown; however, as the onset of PZQ sensitivity coincides with attainment of sexual maturity and the beginning of fertilized egg production, the energetic cost of reproduction for adult worms may be too great to allow significant transcriptomic flexibility. In juvenile worms, the drug may be maintained at sub-lethal levels by ATP-dependent drug pumps, while perturbations wrought by Ca2+ influx may be countered by increasing the transcription of stress response genes, and possibly by the regulation of those genes that determine whether cells enter an apoptotic state. In conclusion, these experiments suggest that transcriptomic flexibility plays a significant role in allowing juvenile worms to survive exposure to PZQ.

The effect of praziquantel on the transcriptome of Schistosoma mansoni is assessed.

Juvenile worms are able to make a robust transcriptomic response to praziquantel.

Adult male worms have a relatively weak transcriptomal response to praziquantel.

Juveniles express genes whose products may protect them from the praziquantel.

Adult schistosomes may be drug sensitive due to transcriptomal inflexibility.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Fred Lewis and his staff at the NIAID Schistosomiasis Resource Center, Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD for their supply of S. mansoni infected mice through NIAID contract HHSN272201000009I. Technical support was supplied by the Molecular Biology Core Facility of the Dept. of Biology, University of New Mexico. This work was made possible with support from NIH through grant numbers 1R56AI087807-01 and 1RO1AI087807-01A1 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].King CH. Parasites and poverty: the case of schistosomiasis. Acta Tropica. 2010;113:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hagan P, Appleton CC, Coles GC, Kusel JR, Tchuem-Tchuenté L-A. Schistosomiasis control: keep taking the tablets. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].King CH, Mahmoud AAF. Drugs five years later: praziquantel. Ann Int Med. 1989;110:290–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-4-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gönnert R, Andrews P. Praziquantel, a new board-spectrum antischistosomal agent. Z Parasitenk. 1977;52:129–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00389899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sabah AA, Fletcher C, Webbe G, Doenhoff MJ. Schistosoma mansoni: chemotherapy of infections of different ages. Exp Parasitol. 1986;61:294–303. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(86)90184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pica-Mattoccia L, Cioli D. Sex- and stage-related sensitivity of Schistosoma mansoni to in vivo and in vitro praziquantel treatment. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:527–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aragon AD, Imani RA, Blackburn VR, Cupit PM, Melman SD, Goronga T, et al. Towards an understanding of the mechanism of action of praziquantel. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;164:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pax R, Bennett JL, Fetterer R. A benzodiazepine derivative and praziquantel: effects on musculature of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1978;304:309–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00507974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Greenberg RM. Are Ca2+ channels targets of praziquantel action? Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nogi T, Zhang D, Chan JD, Marchant JS. A novel biological activity of praziquantel requiring voltage-operated Ca2+ channel β subunits: subversion of flatworm regenerative polarity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lima SF, Vieira LQ, Harder A, Kusel JR. Effects of culture and praziquantel on membrane fluidity parameters of adult Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol. 1994;109:57–64. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wiest PM, Li Y, Olds GR, Bowen WD. Inhibition of phosphoinositide turnover by praziquantel in Schistosoma mansoni. J Parasitol. 1992;78:753–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ribeiro F, Coelho PMZ, Vieira LQ, Watson DG, Kusel JR. The effect of praziquantel treatment on glutathione concentration in Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol. 1998;116:229–36. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097002291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Angelucci F, Basso A, Bellelli A, Brunori M, Pica-Mattoccia L, Valle C. The anti-schistosomal drug praziquantel is an adenosine antagonist. Parasitol. 2007;134:1215–21. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007002600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gnanasekar M, Salunkhe AM, Mallia AK, He YX, Kalyanasundaram R. Praziquantel affects the regulatory myosin light chain of Schistosoma mansoni. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1054–60. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01222-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tallima H, El Ridi R. Praziquantel binds Schistosoma mansoni adult worm actin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:570–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Novoradovskaya N, Whitfield ML, Basehore LS, Novoradovsky A, Pesich R, Usary J, et al. Universal Reference RNA as a standard for microarray experiments. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gobert GN, McInnes R, Moertel L, Nelson C, Jones MK, Hu W, et al. Transcriptomics tool for the human Schistosoma blood flukes using microarray gene expression profiling. Exp Parasitol. 2006;114:160–72. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Leopold G, Ungethüm W, Groll E, Diekmann HW, Nowak H, Wegner DHG. Clinical pharmacology in normal volunteers of praziquantel, a new drug against schistosomes and cestodes. Eur J Clin Pharm. 1978;14:281–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00560463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rajkovic A, Davis RE, Simonsen JN, Rottman FM. A spliced leader is present on a subset of mRNAs from the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8879–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Davis RE, Hardwick C, Tavernier P, Hodgson S, Singh H. RNA trans-splicing in flatworms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21813–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].James CE, Hudson AL, Davey MW. Drug resistance mechanisms in helminths: is it survival of the fittest? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].James CE, Hudson AL, Davey MW. An update on P-glycoprotein and drug resistance in Schistosoma mansoni. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:538–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bosch IB, Wang Z-X, Tao L-F, Shoemaker CB. Two Schistosoma mansoni cDNAs encoding ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:351–6. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kasinathan RS, Morgan WM, Greenberg RM. Schistosoma mansoni express higher levels of multidrug-associated protein 1 (SmMRP1) in juvenile worms and in response to praziquantel. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;173:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kasinathan RS, Greenberg RM. Pharmacology and potential physiological significance of schistosome multidrug resistance transporters. Exp Parasitol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.03.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Messerli SM, Kasinathan RS, Morgan W, Spranger S, Greenberg RM. Schistosoma mansoni P-glycoprotein levels increase in response to praziquantel exposure and correlate with reduced praziquantel susceptibility. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kasinathan RS, Goronga T, Messerli SM, Webb TR, Greenberg RM. Modulation of a Schistosoma mansoni multidrug transporter by the antischistosomal drug praziquantel. FASEB J. 2010;24:128–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kasinathan RS, Morgan WM, Greenberg RM. Genetic knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of parasite multidrug resistance transporters disrupts egg production in Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;e1425 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pica-Mattoccia L, Orsini T, Basso A, Festucci A, Liberti P, Guidi A, et al. Schistosoma mansoni: lack of correlation between praziquantel-induced intra-worm calcium influx and parasite death. Exp Parasitol. 2008;119:332–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B, Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pinton P, Giorgi C, Siviero R, Zecchini E, Rizzuto R. Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitchondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6407–18. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shaw MK, Erasmus DA. Schistosoma mansoni: changes in elemental composition in relation to the age and sexual status of the worms. Parasitol. 1983;86:439–53. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000050630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xiao SH, Mei JY, Jiao PY. The in vitro effect of mefloquine and praziquantel against juvenile and adult Schistosoma japonicum. Parasitol Res. 2009;106:237–46. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Redman CA, Robertson A, Fallon PG, Modha J, Kusel JR, Doenhoff MJ, et al. Praziquantel: an urgent and exciting challenge. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:14–20. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)80640-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]