Abstract

Buforin II is a histone-derived antimicrobial peptide that readily translocates across lipid membranes without causing significant membrane permeabilization. Previous studies showed that mutating the sole proline of buforin II dramatically decreases its translocation. As well, researchers have proposed that the peptide crosses membranes in a cooperative manner through forming transient toroidal pores. This paper reports molecular dynamics simulations designed to investigate the structure of buforin II upon membrane entry and evaluate whether the peptide is able to form toroidal pore structures. These simulations showed a relationship between protein-lipid interactions and increased structural deformations of the buforin N-terminal region promoted by proline. Moreover, simulations with multiple peptides show how buforin II can embed deeply into membranes and potentially form toroidal pores. Together, these simulations provide structural insight into the translocation process for buforin II in addition to providing more general insight into the role proline can play in antimicrobial peptides.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptide, cell-penetrating peptide, histone, membrane translocation, molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides provide a promising alternative in ongoing efforts to develop new therapeutic options to combat infectious bacteria resistant to conventional antibiotic agents [38]. While many antimicrobial peptides kill bacteria through some type of membrane disruption, an increasing number appear to function through an ability to enter cells and interfere with some intracellular process [9]. These peptides are particularly interesting not only for their antibacterial properties but also for potential uses in transfection and drug delivery. In particular, many researchers have increasingly noted the similarities between antimicrobial peptides and cell-penetrating peptides [10, 33].

Buforin II (BF2) [5] is an antimicrobial peptide derived from histone H2A that is believed to kill bacteria by entering cells in a non-lytic manner and binding to nucleic acids [25, 36]. BF2 membrane translocation is independent of any cellular receptor as the peptide can readily enter both bacterial cells [25, 26] and vesicles containing only lipids in their membrane [16, 17, 37]. Based on analyses of lipid vesicle experiments, previous work has proposed that the peptide crosses the membrane in a cooperative manner that involves the formation of transient toroidal pores that rapidly dissociate, leaving some peptide on both sides of the membrane [16]. Moreover, several studies have shown that mutating the sole proline of BF2 (e.g. P11A or P11L) markedly decreases its ability to translocate across membranes [17, 26]. Although NMR structural work and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy have shown that the proline residue can cause disorder in the N-terminal region of BF2 [18, 40], it is unknown how this disordered structure promotes translocation.

This paper describes a series of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations designed to provide a molecular-level interpretation for experimental BF2 translocation data. Previous simulations considering a single BF2 peptide interacting with membranes made of different lipids gave some insight into BF2•membrane interactions, but those simulations only showed limited membrane entry [8]. Here we significantly extent those simulations to show additional membrane entry and incorporate multiple peptides. The simulations in this paper were performed with two particular goals. First, simulations were used in order to investigate how structural disorder in the N-terminus of BF2 could relate to membrane entry. Second, simulations were used to determine whether it is feasible for BF2 to form toroidal pores, as previously proposed in its translocation mechanism.

MD simulations have provided useful molecular-level insight into the function of a variety of antimicrobial peptides and have been the subject of recent reviews [2–4]. In particular, some recent simulations have used MD simulations to investigate how antimicrobial peptides can form pores across membranes [6, 19–21, 23, 31, 34]. Some of these studies have even shown the process of membrane entry over the course of an explicit MD simulation [6, 20, 31]. However, these studies of antimicrobial peptide pore formation have focused on peptides that operate via a lytic mechanism, such as magainin or melittin. Thus, the simulations of BF2 performed in this work allow a comparison between the pores formed by those lytic peptides and those formed by a non-lytic translocating peptide.

2. Materials and Methods

A summary of simulations performed in this study is given in Table 1 and peptide sequences considered are shown in Table 2. Setup of single BF2 simulations was analogous to that described in Fleming et al. [8], using the F10W variant of BF2 used in previous experimental studies [8, 16, 17, 36, 37], 128 palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) lipids and 3797 SPC water. Simulations of multiple peptides initially placed four BF2 peptides near the headgroup region of the same preequilibrated POPC membrane with either 6412 or 12415 SPC water. Peptides in all simulations were initially in a fully α-helical structure to prevent biasing the peptide towards any particular helical deformation. Na+ and Cl− ions were added to neutralize charge and provide an additional 100 mM salt concentration. A control simulation was performed omitting peptides from a system with 12415 water molecules.

Table 1.

Summary of molecular dynamics simulations performed for this study. All simulations contained 128 POPC lipid molecules.

| simulation | peptides included | number of water | length | simulation details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt 1 | 1 wt BF2 | 3797 | 75 ns | |

| wt 2 | 1 wt BF2 | 3797 | 75 ns | peptide rotated around z- axis from initial position in wt 1 |

| P11A 1 | 1 P11A BF2 | 3797 | 75 ns | |

| P11A 2 | 1 P11A BF2 | 3797 | 75 ns | peptide rotated around z- axis from initial position in P11A 2 |

| wt constrained | 1 wt BF2 | 3797 | 75 ns | constrained to α-helix |

| 4pep 1 | 4 wt BF2 | 6412 | 100 ns | |

| 4pep 2 | 4 wt BF2 | 6412 | 100 ns | 0.20 V/nm potential |

| 4pep 3 | 4 wt BF2 | 6412 | 100 ns | 0.25 V/nm potential |

| 4pep 4 | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 100 ns | |

| 4pep 5 | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 100 ns | 0.10 V/nm potential |

| 4pep 6 | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 75 ns | 0.20 V/nm potential |

| 4pep 7 | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 25 ns | 0.20 V/nm potential |

| 4pep 6 extend | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 25 ns | starting from 72 ns frame of 4pep 6; no potential |

| 4pep 7 extend | 4 wt BF2 | 12415 | 25 ns | starting from 22.6 ns frame of 4pep 7; no potential |

| voltage control | none | 12415 | 100 ns | 0.20 V/nm potential |

Table 2.

Amino acid sequences of peptides in simulations performed for this study. Peptides in simulations included the F10W mutation used in many previous experimental studies of BF2.

| Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| buforin II (BF2) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK |

| P11A | TRSSRAGLQWAVGRVHRLLRK |

Before starting MD simulations, systems were subjected to 150 steps of steepest descents minimization. The systems were then heated gradually to 310 K over 20 ps and the Cα of the peptide were restrained to their initial position with a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol nm2. These restraints were released in gradual steps over the next 1880 ps of the simulations. In the simulation of wild type BF2 restrained to a helical conformation, restraints of 100 kJ/mol•rad2 were placed on all backbone dihedral angles of the peptide throughout the simulation. Single peptide trajectories were extended to 75 ns, and multiple peptide trajectories were extended for 100 ns or until pore formation disrupted the membrane system. MD simulations used a timestep of 2 ps with bonds constrained by the LINCS routine [12] and water geometries constrained by SETTLE [24]. Pressure and temperature were controlled with Berendsen coupling[1]. Simulations were performed under the NPT ensemble with anisotropic pressure coupling to 1 bar in each direction using a time constant (tp) of 1.0 ps. Temperature was maintained at 310 K with a time constant (tt) of 0.1 ps for three separate groups: peptide, lipid, and the water and ions grouped together. PME [7] was used to calculate long-range electrostatics in the simulations, with a grid spacing of 0.10 nm and cubic interpolation. Lennard-Jones energies were cutoff at 1.0 nm. Analyses were performed using tools in the GROMACS suite. Hydrogen bonding was determined using a geometric cutoff of 3.5 Å and an interaction angle of α 30°. Molecular graphics were created using VMD [14].

All minimizations and MD simulations were performed using GROMACS [13], with force field parameters as in Fleming et al. [8]. These parameters were chosen to allow direct comparison with previous simulations of BF2 performed using a variety of different lipid membranes. However, as an additional control two additional simulations of a single BF2 peptide with a POPC membrane were performed using the more recently developed Gromos 54A7 forcefield [28, 29]. These simulations with the alternative force field showed analogous trends for peptide structure and peptide-lipid H-bonds upon membrane entry as those discussed in Figures 2 and 3 (data not shown).

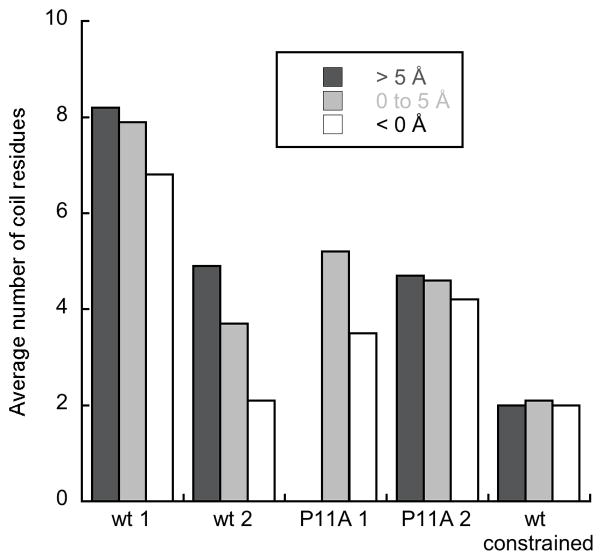

Figure 2.

Average number of N-terminal BF2 residues (residues 1–10) with a coil structure as defined by DSSP [15] for peptides at different depths in the membrane (> 5 Å, dark gray; 0–5 Å, light gray; < 0 Å, white). Data is from simulations containing a single peptide. A depth of zero reflects a peptide located at the average position of the lipid phosphorous atoms, while positive depths reflect peptides more embedded in the membrane. Peptide in the P11A 1 simulation never embedded past 5 Å during the simulation.

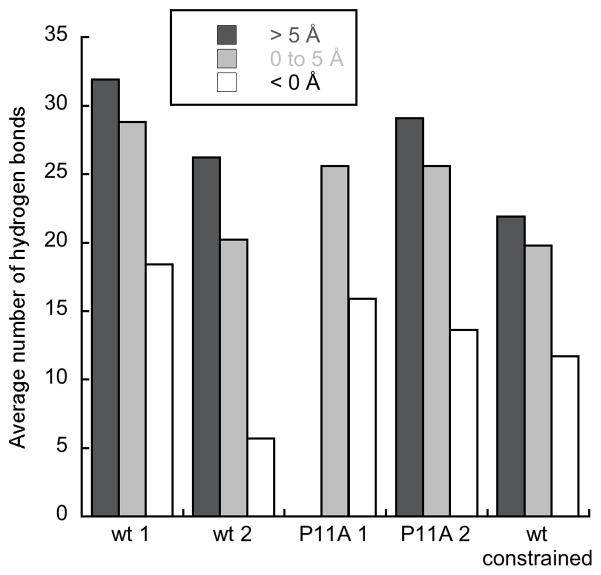

Figure 3.

Average number of peptide•lipid H-bonds for peptides at different depths in the membrane in simulations containing a single peptide (> 5 Å, dark gray; 0–5 Å, light gray; < 0 Å, white). Depth is defined as in Fig. 2.

3. Results

3.1 Simulations with a single peptide

Previous simulations by Fleming et al. compared the membrane interactions of a single BF2 peptide with the surface of membranes made from different lipids, including POPC and POPG [8]. In experimental work, cationic BF2 is not attracted to neutral POPC membranes, although it is attracted to membranes with a negative charge, such as POPG or mixed POPC/POPG membranes [8, 17]. However, MD simulations in Fleming et al. showed that if BF2 is placed at the membrane interface it is able to readily enter pure POPC membranes, despite their neutral charge. In fact, more significant entry was observed into POPC than POPG membranes in those simulations. Together with experimental data showing that BF2 translocates more poorly into pure POPG vesicles than mixed POPC/POPG vesicles [16], these observations from simulations imply that negatively charged lipids are needed to initially attract BF2 to the membrane surface but may actually impede membrane entry once peptides are recruited to the membrane surface. Thus, in order to promote BF2 membrane entry all simulations in this present study used pure POPC membranes with peptides placed at the membrane interface at the beginning of the trajectory. All simulations also began with the peptide in a fully helical conformation in order to reduce any potential bias towards kinked peptide conformations that could arise from starting with an initially deformed peptide conformation.

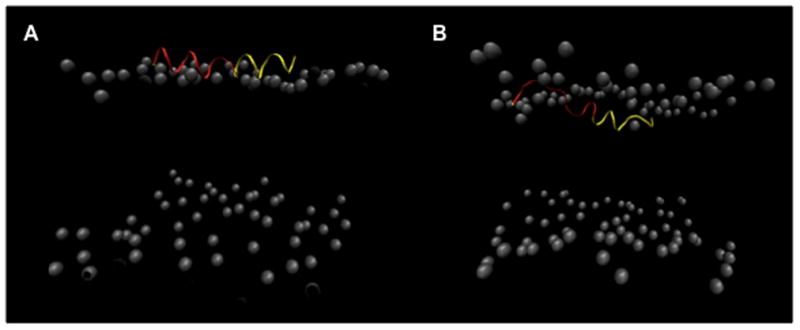

One of the two simulations of wild type BF2 (wt 1) showed marked N-terminal deformation upon membrane entry (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). This deformation allowed the positively charged residues of the peptide to interact more effectively with headgroups during increased membrane entry, drawing some of the headgroups significantly into the hydrophobic region of the membrane. The structural deformation of the N-terminal region was greatest when the peptide entered the membrane more deeply (Fig. 2). The peptide showed less structural deformation (Fig. 2) over the timecourse of the other wild type simulation (wt 2), although deformation still increased with greater membrane entry. Notably, the simulation with greater N-terminal deformation also had distinctly more peptide•lipid H-bonds (Fig. 3). Thus, the extent of structural deformation appeared directly related to the formation of increased lipid interactions.

Figure 1.

Representative frames from simulation (wt 1) of a single wild type BF2 peptide (yellow ribbon) showing increased deformation of the N-terminal region (red) upon membrane entry. Lipid phosphorous atoms are shown as gray spacefilling; phosphorous atoms blocking the peptide in the leftmost image were removed for clarity.

The observation that N-terminal deformation is necessary to maximize lipid interactions upon membrane entry was tested further using simulations with the peptide constrained to a helical structure (wt constrained) or with a P11A mutation known to decrease N-terminal deformation (P11A 1 and P11A 2) [17, 26, 37]. Interestingly, these simulations did not show significantly less membrane entry than those of wild type (data not shown). However, neither P11A simulation showed as much N-terminal deformation upon membrane entry as wt 1 (Fig. 2), and this lack of deformation correlated with decreased lipid interactions as the peptides embedded further into the membrane (Fig. 3). Although the P11A mutant does allow for some deformation from an α-helical structure, essentially no deformation was allowed in the constrained simulation (Fig. 2). Consequently, the constrained simulation showed a particularly pronounced decrease in lipid interactions (Fig. 3), further emphasizing the connection between structural deformation and effective formation of lipid interactions.

3.2 Promoting further membrane entry of peptides in simulations

Overall, our single peptide simulations support the assertion that increased distortion from α-helical structure in the N-terminal region of BF2 promotes peptide•lipid interactions. However, these simulations only demonstrated limited membrane entry, as even the wt 1 simulation showed relatively minimal progress towards translocation. Previous experimental evidence implied that BF2 crosses membranes in a cooperative manner [17]. Thus, additional simulations were run with four peptides in order to observe membrane entry more analogous to that which occurs in translocation. The peptide:lipid ratio in these simulations is relatively similar to that used in previous experimental measurements of BF2 translocation into lipid vesicles [16, 17]. However, no significant membrane entry of peptides beyond that observed for single peptide simulations was observed in a 100 ns trajectory (4pep 1).

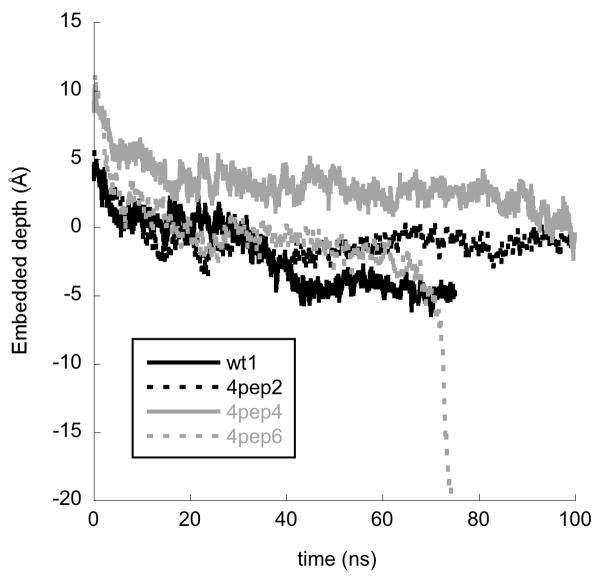

Thus, the simulation was adjusted in two ways to bias the trajectory towards additional membrane entry. First, an electrostatic potential biased entry into the membrane. Since BF2 is polycationic, the peptides would be pulled towards the negative potential on the opposite side of the membrane. No additional entry was observed in 100 ns simulations with a potential up to 0.25 V/nm (4pep 2 and 4pep 3). Based on previous simulations considering pore formation by applied electric potentials [35], using larger potentials could compromise membranes regardless of peptide function. Instead, membrane hydration was increased (from an approximately 1:50 to 1:97 lipid:water ratio) since increased hydration was observed to improve entry and toroidal pore formation in simulations of TAT peptides [11]. Since increased hydration alone did not significantly improve progress towards translocation in a 100 ns simulation (4pep 4), simulations were performed with increased hydration and an applied potential. Although an applied potential of 0.10 V/nm was not sufficient (4pep 5), a combination of increased hydration and an applied potential of 0.20 V/nm did lead towards membrane entry. The effect of adding 0.20 V/nm potential alone, increased hydration alone and both 0.20 V/nm potential and increased hydration on membrane entry is shown in Fig. 4. Two simulations (4pep 6 and 4pep 7) were performed with increased hydration and a 0.20 V/nm potential until formation of a toroidal pore disrupted the membrane in each case. A 100 ns simulation of an identical POPC/water system lacking BF2 peptides (voltage control) remained intact and did not show any aqueous pore formation, showing that the membrane model was stable to these simulation conditions and that pore formation required the presence of BF2 peptide.

Figure 4.

Maximum embedded depth of any peptide during the trajectories of BF2 simulations with a single peptide (wt 1), four peptides with 0.20 V/nm applied potential (4pep 2), four peptides with additional hydration (4pep 4) and four peptides with both additional hydration and 0.20 V/nm applied potential (4pep 6). Depth is defined as in Fig. 2.

3.3 Membrane entry and toroidal pore formation in multiple peptide simulations

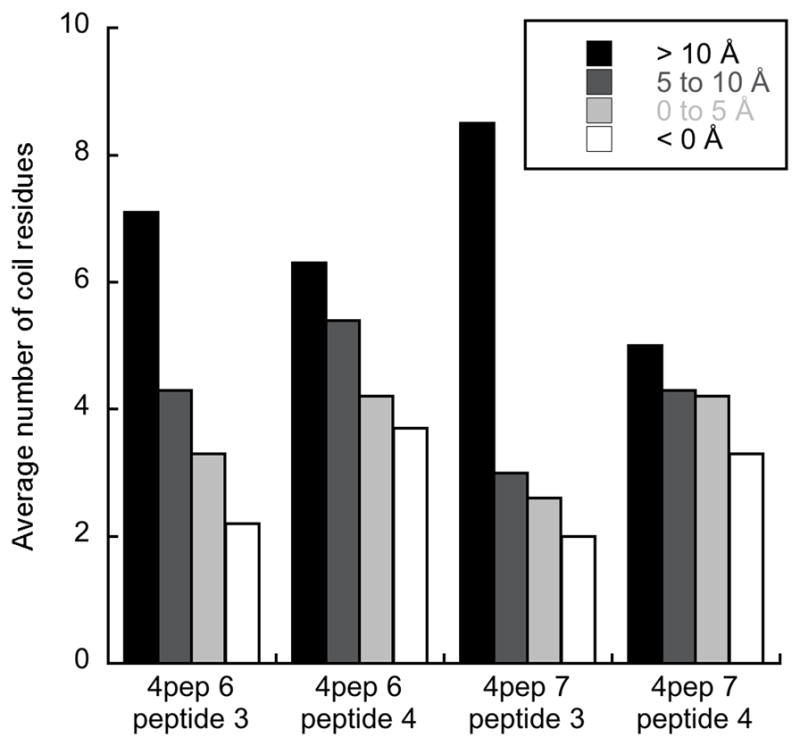

Both simulations with increased hydration and a 0.20 V/nm applied potential (4pep 6 and 4pep 7) had two peptides entering the membrane beyond the headgroup region. Initially, in both simulations all four peptides were placed in identical conformations located above the lipid headgroups. As the simulations progressed, all four peptides remained near the lipid headgroups for the majority of the trajectory. However, eventually one peptide began to enter significantly deeper into the membrane, and a second peptide began to follow it relatively rapidly. Structurally, there was a clear increase in deformation of the N-terminal portion of both these peptides as they increasingly entered the membrane (Fig. 5). Similar to the single peptide simulations, the deformation appeared to facilitate increased lipid interactions as peptides progressed beyond the lipid headgroup region (Fig. 6). Accordingly, these lipids were increasingly pulled into the hydrophobic core of the membrane, allowing positively charged sidechains to remain nearer to the lipid headgroups as the peptide enters the hydrophobic region of the membrane.

Figure 5.

Average number of N-terminal BF2 residues (residues 1–10) with a coil structure as defined by DSSP for peptides at different depths in the membrane (> 10 Å, black; 5–10 Å, dark gray; 0–5 Å, light gray; < 0 Å, white). Data is for simulations containing four peptides under a potential of 0.20 V/nm. Depth is defined as in Fig. 2. Data is only shown for peptides that embedded further than 5 Å into the membrane at some point during the simulation.

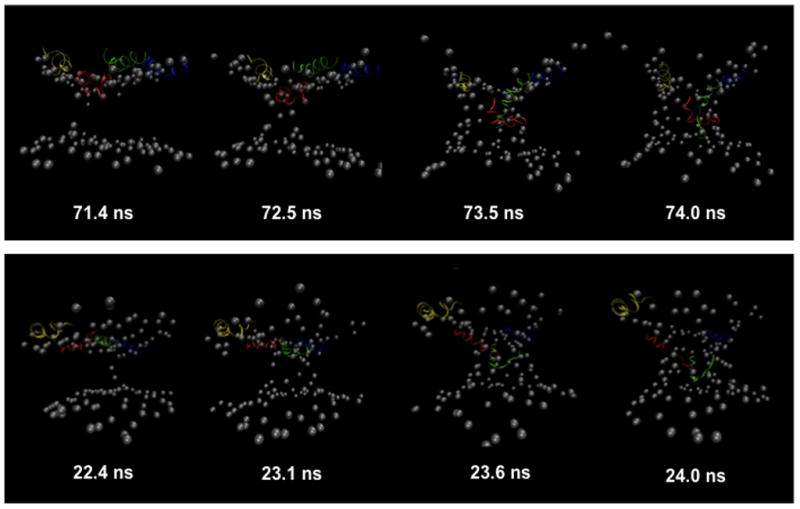

Figure 6.

Selected frames showing the progression of BF2 into the membrane and the formation of toroidal pore structures from simulations with four peptides under 0.20 V/nm potential (4pep 6 top, 4pep 7 bottom). Representations are as in Figure 1, with each peptide given a different color: peptide 1, yellow; peptide 2, blue; peptide 3, green; peptide 4, red. Peptide numbering was done such that the two most embedded peptides in each simulation were peptides 3 and 4 (red and green).

The entry of headgroups into the lipid membrane eventually led to the formation of a toroidal pore in both simulations (Fig. 6). In both cases, one peptide primarily started the formation of the pore, with at least one other peptide in the close vicinity at the surface of the membrane near the top of the forming aqueous pore. As the first peptide entered the membrane, adjacent lipid headgroups were drawn into the hydrophobic region. A similar deformation arose on the other leaflet, and headgroups from each leaflet eventually came into contact, forming a connection across the membrane. After pore formation had begun, a second peptide entered the pore. The peptides in the pore region interacted with both the lipid headgroups that had been pulled into the transmembrane region and water molecules in the pore. The pore formation for BF2 was similar to the process of “disordered” toroidal pore formation observed in simulations of magainin, melittin and BPC194, in which one peptide initially entered the membrane and deformed the headgroup region, followed by other peptides forming additional peptide•lipid interactions leading to formation of a toroidal pore [6, 20, 31]. As with BF2, none of these simulations showed the formation of a regular or symmetric pore structure during the simulations. Interestingly, the N-terminal region of melittin shows an lack of α-helical structure analogous to that observed here for BF2 during pore formation despite its generally helical structure when bound to the membrane surface [31].

Once pores formed in BF2 simulations they led to severe membrane disruption on a relatively short (e.g. 1–2 ns) timescale. This is not particularly surprising given the relatively small size of the membrane patch and the magnitude of the applied potential. However, additional 25 ns simulations without an applied potential (4pep 6 extend and 4pep 7 extend) were started from frames taken from both 4pep 6 (72 ns) and 4pep 7 (22.6 ns). Both these frames were chosen as they were near the beginning of aqueous pore formation in the simulations. An aqueous pore remained across the membrane throughout these extended simulations, showing the ability of BF2 to stabilize a toroidal membrane pore in the absence of a biasing potential. However, the peptides did not make additional progress towards translocation through the pore during these simulations.

4. Discussion

The simulations presented in this study provide molecular-level insight into the role played by proline in the membrane translocation mechanism of BF2 and provide support for the formation of toroidal pores in the BF2 translocation mechanism. In BF2, proline causes a deformation of α-helical structure that helps the peptide to embed more deeply into the membrane. These observations are consistent with previous experimental work considering the translocation of BF2 proline mutants. As observed in many studies [17, 26, 37], removing the proline (e.g. P11A BF2) significantly reduces translocation. However, moving the proline one turn towards the Nor C-terminus (P11A/G7P or P11A/V15P BF2) partially restores translocation [37]. Thus, it appears that having some deformation resulting from proline moved to a different position in the peptide is preferable for translocation than the absence of any proline. However, the wild type peptide appears to have the proline and the resulting structural deformation in an ideal position for effective translocation. Consistent with these observations, replacing proline a single residue away from its wild type position (P11A/V12P BF2) effectively maintains the normal translocation behavior of BF2, as this mutant would not significantly alter the propensity for helical deformation in the N-terminal region [37].

Since BF2 causes relatively little membrane leakage, it is hypothesized to translocate by forming very transient toroidal pores that rapidly disassemble, leading some peptides to end up on the other side of the membrane [16]. The observation of toroidal pores in the simulations presented here are consistent with this assertion. The pores observed in BF2 simulations were structurally similar to those seen for lytic antimicrobial peptides, such as magainin and melittin. However, in the absence of a biasing potential they did not form spontaneously in a similar timeframe used in simulations of those lytic peptides. The need for a biasing potential to induce pore formation on the simulation timescale may result from the relative instability of any transient toroidal pores formed by BF2, as suggested by previous studies [16], although our current simulations do not give direct insight into the lifetime of BF2 toroidal pores. The transient nature of this pore would be necessary for the peptide to exhibit membrane translocation with minimal permeabilization, as observed in experimental studies [17].

It is important to note that the observation of toroidal pores in our simulations do not preclude other possibilities for translocation. In light of this, it is interesting to consider recent simulations of the cell-penetrating peptide TAT [11, 39]. In one set of simulations, TAT was observed to translocate across membranes through the formation of toroidal pores [11]. However, more recent simulations using a larger membrane patch showed no pore formation under a similar timescale [39]. Instead, the TAT peptide appeared to form larger-scale curvature of the membrane that could be the early steps in of a micropinocytotic pathway. These changes in curvature would only be notable in a larger membrane system than used in our current study. Thus, future work considering a larger membrane patch may provide additional information to support or refine the hypothesis of BF2 translocation through a toroidal pore mechanism. Nonetheless, the simulations described here are consistent in size to those used that provided significant insight into the formation of pores in other antimicrobial peptide systems [6, 20, 23, 31].

While these results provide direct insight into the role structural deformations caused by proline in BF2, it will be particularly interesting to investigate whether proline plays a similar role in the translocation of other peptides. For example, recent work has found that the presence of proline enhances the translocation of some, but not all, histone-derived antimicrobial peptides [27]. Moreover, proline residues are prevalent in several antimicrobial peptides [22, 32], and the ability of proline residues to disrupt structure may play a similar role in these systems. In particular, many members of the proline-rich antimicrobial peptide family appear to function via a mechanism in which they enter cells without causing membrane lysis, analogous to BF2 [30]. More generally, numerous studies have emphasized the importance of α-helical structure for antimicrobial peptide function, since several peptides adopt a helical structure upon interacting with membranes. However, these simulations emphasize the importance of non-helical structures as peptides assume their active conformation inside membranes.

Highlights.

Performed molecular dynamics simulations of buforin II membrane entry

First pore-forming simulations for a non-lytic antimicrobial peptide

Showed relationship between membrane entry, helical deformation and lipid interaction

Observed toroidal pore formation proposed in previous experimental studies

Considered changes to MD simulation conditions necessary to promote membrane entry

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH/NIAID) award R15AI079685 and a Research Corporation Cottrell College Science Award. D.E.E. is a Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar.

Abbreviations

- BF2

buforin II

- HDAP

histone-derived antimicrobial peptide

- MD

molecular dynamics

- POPC

palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine

- POPG

palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylglycerol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bocchinfuso G, Bobone S, Mazzuca C, Palleschi A, Stella L. Fluorescence spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations in studies on the mechanism of membrane destabilization by antimicrobial peptides. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2281–301. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0719-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolintineanu DS, Kaznessis YN. Computational studies of protegrin antimicrobial peptides: a review. Peptides. 2011;32:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond PJ, Khalid S. Antimicrobial and cell-penetrating peptides: structure, assembly and mechanisms of membrane lysis via atomistic and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Protein Pept Lett. 2010;17:1313–27. doi: 10.2174/0929866511009011313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho JH, Sung BH, Kim SC. Buforins: Histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptides from toad stomach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1564–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirac AD, Moiset G, Mika JT, Kocer A, Salvador P, Poolman B, et al. The molecular basis for antimicrobial activity of pore-forming cyclic peptides. Biophys J. 2011;100:2422–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darden TD, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming E, Maharaj NP, Chen JL, Nelson RB, Elmore DE. Effect of lipid composition on buforin II structure and membrane entry. Proteins. 2008;73:480–91. doi: 10.1002/prot.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hale JD, Hancock RE. Alternative mechanisms of action of cationic antimicrobial peptides on bacteria. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5:951–9. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques ST, Melo MN, Castanho MA. Cell-penetrating peptides and antimicrobial peptides: how different are they? Biochem J. 2006;399:1–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herce HD, Garcia AE. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest a mechanism for translocation of the HIV-1 TAT peptide across lipid membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20805–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comp Chem. 1997;18:1463–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–47. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD—Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Molec Graphics. 1996;14:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi S, Chikushi A, Tougu S, Imura Y, Nishida M, Yano Y, et al. Membrane translocation mechanism of the antimicrobial peptide buforin 2. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15610–6. doi: 10.1021/bi048206q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi S, Takeshima K, Park CB, Kim SC, Matsuzaki K. Interactions of the novel antimicrobial peptide buforin 2 with lipid bilayers: proline as a translocation promoting factor. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8648–54. doi: 10.1021/bi0004549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan Y, Ye Y, Kozlowska J, Lam JK, Drake AF, Mason AJ. Structural contributions to the intracellular targeting strategies of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:1934–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langham AA, Ahmad AS, Kaznessis YN. On the nature of antimicrobial activity: a model for protegrin-1 pores. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4338–46. doi: 10.1021/ja0780380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Antimicrobial peptides in action. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12156–61. doi: 10.1021/ja062927q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manna M, Mukhopadhyay C. Cause and effect of melittin-induced pore formation: a computational approach. Langmuir. 2009;25:12235–42. doi: 10.1021/la902660q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markossian KA, Zamyatnin AA, Kurganov BI. Antibacterial proline-rich oligopeptides and their target proteins. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2004;69:1082–91. doi: 10.1023/b:biry.0000046881.29486.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mihajlovic M, Lazaridis T. Antimicrobial peptides in toroidal and cylindrical pores. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:1485–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto S, Kollman PA. SETTLE: An analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithms for rigid water models. J Comp Chem. 1992;13:952–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CB, Kim HS, Kim SC. Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II: buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:253–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park CB, Yi KS, Matsuzaki K, Kim MS, Kim SC. Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: the proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:8245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150518097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavia KE, Spinella SA, Elmore DE. Novel histone-derived antimicrobial peptides use different antimicrobial mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:869–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poger D, Mark AE. On the validation of molecular dynamics simulations of saturated and cis-monounsaturated phosphatidylcholine lipid bilayers: A comparison with experiment. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:325–36. doi: 10.1021/ct900487a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poger D, van Gunsteren WF, Mark AE. A new force field for simulating phosphatidylcholine bilayers. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:1117–25. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scocchi M, Tossi A, Gennaro R. Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides: converging to a non-lytic mechanism of action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2317–30. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0721-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sengupta D, Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Toroidal pores formed by antimicrobial peptides show significant disorder. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:2308–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sitaram N. Antimicrobial peptides with unusual amino acid compositions and unusual structures. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:679–96. doi: 10.2174/092986706776055689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Splith K, Neundorf I. Antimicrobial peptides with cell-penetrating peptide properties and vice versa. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:387–97. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thogersen L, Schiott B, Vosegaard T, Nielsen NC, Tajkhorshid E. Peptide aggregation and pore formation in a lipid bilayer: a combined coarse-grained and all atom molecular dynamics study. Biophys J. 2008;95:4337–47. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tieleman DP, Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Simulation of pore formation in lipid bilayers by mechanical stress and electric fields. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6382–3. doi: 10.1021/ja029504i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uyterhoeven ET, Butler CH, Ko D, Elmore DE. Investigating the nucleic acid interactions and antimicrobial mechanism of buforin II. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1715–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie Y, Fleming E, Chen JL, Elmore DE. Effect of proline position on the antimicrobial mechanism of buforin II. Peptides. 2011;32:677–82. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yesylevskyy S, Marrink SJ, Mark AE. Alternative mechanisms for the interaction of the cell-penetrating peptides penetratin and the TAT peptide with lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2009;97:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yi GS, Park CB, Kim SC, Cheong C. Solution structure of an antimicrobial peptide buforin II. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]