Abstract

Previous studies have shown that injured dorsal column sensory axons extend across a spinal cord lesion site if axons are guided by a gradient of neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) rostral to the lesion. Here we examined whether continuous NT-3 delivery is necessary to sustain regenerated axons in the injured spinal cord. Using tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) lentiviral gene delivery, NT-3 expression was tightly controlled by doxycycline administration. To examine axon growth responses to regulated NT-3 expression, adult rats underwent a C3 dorsal funiculus lesion. The lesion site was filled with bone marrow stromal cells, tet-off-NT-3 virus was injected rostral to the lesion site, and the intrinsic growth capacity of sensory neurons was activated by a conditioning lesion. When NT-3 gene expression was turned on, cholera toxin β-subunit-labeled sensory axons regenerated into and beyond the lesion/graft site. Surprisingly, the number of regenerated axons significantly declined when NT-3 expression was turned off, whereas continued NT-3 expression sustained regenerated axons. Quantification of axon numbers beyond the lesion demonstrated a significant decline of axon growth in animals with transient NT-3 expression, only some axons that had regenerated over longer distance were sustained. Regenerated axons were located in white matter and did not form axodendritic synapses but expressed presynaptic markers when closely associated with NG2-labeled cells. A decline in axon density was also observed within cellular grafts after NT-3 expression was turned off possibly via reduction in L1 and laminin expression in Schwann cells. Thus, multiple mechanisms underlie the inability of transient NT-3 expression to fully sustain regenerated sensory axons.

Introduction

Neurotrophic factor delivery to injured axons or neuronal cell bodies is one means to promote neuronal survival, prevent neuronal atrophy, and enhance axonal growth after spinal cord injury (SCI) (Markus et al., 2002; Tuszynski and Lu, 2008). Axonal regeneration can be guided along a gradient of neurotrophic factors established by neurotrophin gene transfer distal to a spinal cord lesion site. For example, ascending sensory axons cross a dorsal column lesion site filled with a cellular graft along a gradient of NT-3 (Taylor et al., 2006). This regenerative response is further enhanced when neurotrophin gene delivery is combined with conditioning lesions of the peripheral branch of sensory axons to enhance the growth capacity of dorsal root ganglion neurons (Costigan et al., 2002; Neumann et al., 2002; Qiu et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2004; Alto et al., 2009; Kadoya et al., 2009; Blesch et al., 2012).

To stimulate axonal regeneration by growth factor gene delivery, the majority of studies conducted to date used constitutively active promoters for neurotrophin gene delivery, leading to persistent high neurotrophic factor expression (Tuszynski et al., 1996; Blesch and Tuszynski, 2003). Whether axons remain dependent on high levels of growth factors once they have extended across a lesion site or whether high neurotrophin levels are only necessary for active growth is mostly unknown.

During the development of the nervous system, growth factors act as chemoattractive cues and contribute to the establishment of accurate neural circuits (Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996; Tucker et al., 2001; Ma et al., 2002; Markus et al., 2002; Marotte et al., 2004). A reduction in growth factor levels and a lack of connectivity with target neurons or tissues in the periphery results in axonal pruning. If similar mechanisms were to exist in the injured adult CNS, one would predict that regenerated axons that fail to reinnervate their target and to reestablish functional synapses would also be pruned following a decline in growth factors. To test this hypothesis, we previously investigated responses of axons extending into a graft of genetically modified fibroblasts expressing the neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) under the control of a tetracycline-responsive regulatable promoter (Gossen and Bujard, 1992; Gossen et al., 1994, 1995; Blesch and Tuszynski, 2007). Surprisingly, these studies indicated that transient growth factor delivery to a site of SCI is sufficient to sustain regenerated axons in a lesion/graft site (Blesch and Tuszynski, 2007). Based on these findings one would a priori expect that transient neurotrophin gene delivery distal to a site of SCI is also sufficient to sustain axons regenerated beyond a lesion site. However, Schwann cells migrating into a lesion site can provide trophic support and may sustain axons within cellular grafts after exogenous growth factor expression is turned off. Beyond a lesion site, Wallerian degeneration, inflammatory responses, and changes in the extracellular matrix generate an inhospitable, inhibitory environment that differs substantially from a growth-permissive cellular graft at an injury site.

We therefore examined responses of axons that have regenerated across a lesion site into the host spinal cord using a tetracycline-regulated expression system to transiently deliver neurotrophin-3 (NT-3). Surprisingly, the number of ascending dorsal column sensory axons that extend into and beyond a cervical lesion site declines after NT-3 expression is turned off. Hence, transient neurotrophin factor provision is insufficient to sustain all regenerated axons after adult SCI.

Materials and Methods

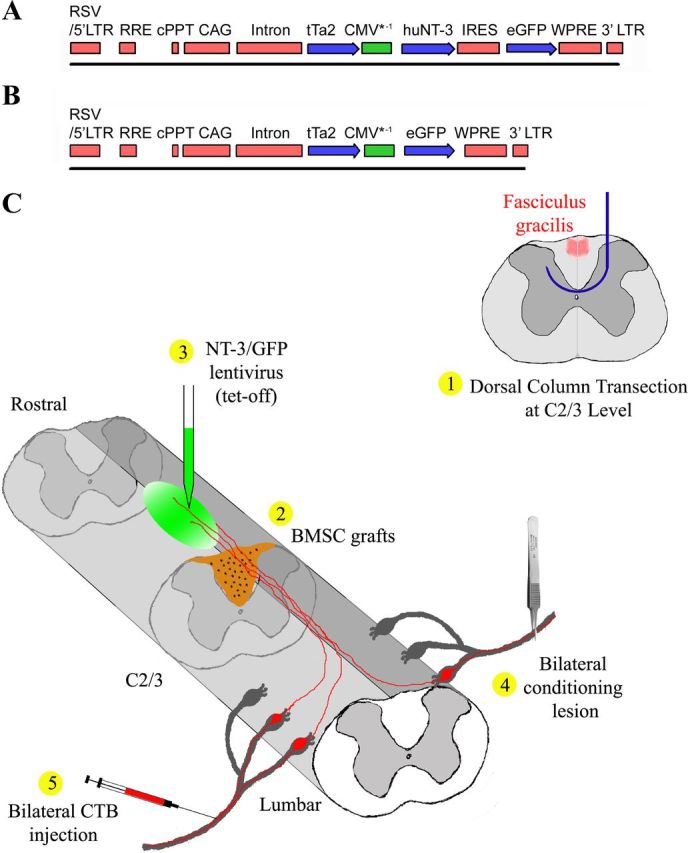

Cloning and production of lentiviral vectors

A tetracycline regulated lentiviral vector was constructed by PCR amplification of the rtTA2sM2 cDNA from pUHrT62-1 (Urlinger et al., 2000). The amplicon was digested with XhoI and cloned into the XhoI site of pUDH10–3 upstream of the Tet response element. The resulting vector was digested with NheI/XhoI and the rtTA2sM2-CMV* gene fragment was cloned into the NheI site of pCDH CAG attR1/2 WPRE (Blesch, 2004), replacing the CAG promoter. The regulation of this vector was found to be insufficient (data not shown) and we therefore constructed the tet-off lentiviral vector used in the current study. The rtTA2sM2 cDNA was removed via NheI/XhoI digestion and replaced with the coding sequence for the tTA2 cDNA (Clontech). Vectors for the tetracycline regulated expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and NT-3 were obtained using the Gateway recombinase system (Invitrogen). The GFP cDNA was digested with EcoRI/XhoI and cloned into the EcoRI/XhoI-digested pENTR2b (Invitrogen). To obtain an NT-3- internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-GFP expression construct, a NotI/BglII fragment containing the IRES-GFP from pIRES2-GFP (Clontech) was cloned into the NotI/BamHI-digested pENTR2b. A BamHI/EcoRI fragment containing the NT-3 cDNA was cloned into the BamHI/EcoR sites upstream of the IRES. GFP and NT-3-IRES-GFP, respectively, were recombined into the pCDH-TetOFF-attR1/2-PRE lentiviral plasmid backbone, replacing the attR1/2-ccd recombination sites (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrations of tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) lentiviral vector constructs and the experimental procedure. A, B, A sin lentiviral vector is used for the regulated expression of (A) NT-3 and (B) GFP. Regulated gene expression is driven by the CMV*-1 promoter. The coding sequence for the tetracycline transactivator tTa2s is driven by the constitutively active CAG promoter. Note that the NT-3 virus also contains a GFP expression cassette via an IRES to allow for the detection of NT-3 producing cells. cPPT, central poly-purine tract; WPRE, Woodchuck post-transcriptional response element. C, Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure: 1, a wire knife (blue) was used to transect dorsal column sensory axons (red) at C2/3 level; 2, immediately after dorsal column transections, BMSC (brown) were grafted into the lesion site; 3, tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) lentiviral vectors expressing NT-3 or GFP (green) were injected into the midline of dorsal white matter 2.5 mm rostral to the lesion site; 4, subsequently, rats underwent bilateral conditioning lesions of the sciatic nerve; and 5, three days before perfusion, CTB was injected into the sciatic nerves bilaterally to transganglionically label ascending sensory tracts (red).

Third-generation lentiviral vector plasmids with a split genome packaging system were used for the production of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-based lentivirus pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G as previously described (Blesch, 2004). High titer stocks of HIV vectors were prepared by ultracentrifugation. All elements for tet-regulated gene expression were contained in a single lentivirus (Fig. 1A,B). Titers of GFP-expressing virus were determined by infection of HEK293T cells using serial dilutions. GFP-expressing colonies were quantified for each dilution to determine infectious units (IU) per milliliter after 48 h. Vector stocks were also assayed for p24 antigen levels using an HIV-1 p24-specific ELISA kit (DuPont) as described previously (Taylor et al., 2006). NT-3 vector preparations contained 100–275 μg/ml p24 and 1.5–2.4 × 108 IU/ml. Control vector preparations contained 100 μg/ml p24 and 2 × 108 IU/ml.

Characterization of NT-3 and GFP expression in vitro

HEK 293T cells were seeded into 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) in DMEM/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After 24 h, the medium was changed and tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus (corresponding to 20 and 40 ng p24 per well, respectively) was added to each well in quadruplicates. Half of the wells were treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline to turn gene expression off. Untransfected cells served as negative controls. Twenty-four hours later, medium was replaced with serum-free CD293 medium (Invitrogen) with or without doxycycline and supernatants were collected for ELISA 24 h later. Cells were photographed under epifluorescent illumination.

NT-3 protein levels were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (NT-3 Emax ImmunoAssay System; Promega). Briefly, 50 μl of the anti-NT-3 polyclonal antibody coating solution (1:500) was added to each well of a 96-well ELISA plate and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, 50 μl of serially diluted test samples and NT-3 standards were added. The plate was incubated for 6 h at room temperature with shaking. Plates were washed, anti-NT-3 monoclonal antibody (1:4000; 50 μl/well) was added, incubated at 4°C overnight, and after an additional wash step, 50 μl of the diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-Mouse IgG (1:100) was added and incubated for 2.5 h. Wells were incubated with o-phenylenediamine as HRP substrate for signal detection, the reaction was stopped, and the absorbance was recorded on a plate reader.

Isolation of bone marrow stromal cells

Syngeneic rat primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) were isolated from tibias and femurs of adult Fischer 344 rats as previously described (Azizi et al., 1998). Briefly, Fischer 344 adult female rats were anesthetized with a combination (3 ml/kg) of ketamine (25 mg/ml), xylazine (1.3 mg/ml), and acepromazine (0.25 mg/ml) and decapitated, and tibias and femurs were dissected. After removing the end of each bone, 5–10 ml of α-MEM (Invitrogen) was injected into the central canal of the bones to extrude marrow. Cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 20% FBS and antibiotics. Nonadherent cells were removed by changing media after 24 h. Cells were passaged twice, then frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Before grafting, cells were thawed and cultured in the same media as above.

Animal subjects and surgical procedures

A total of 81 adult female Fischer 344 rats weighing 150–200 g were used. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Society for Neuroscience guidelines on animal care were strictly followed. Animals were divided into groups based on virus injections, doxycycline treatment, and survival time (Table 1). Twenty-eight rats were used for in vivo measurements of NT-3 protein by ELISA. Fifty-three rats underwent surgery for histological evaluation. A total of four rats were excluded from histological analysis due to insufficient virus spread from the injection site toward the lesion based on GFP expression or poor labeling of ascending sensory axons (n = 1, tet-off-NT-3, −Dox 4 weeks; n = 1, tet-off-NT-3, −Dox 4 weeks/ +Dox 6 weeks; n = 2, tet-off-NT-3, −Dox 10 weeks). Subject numbers stated in the Results and Table 1 are the final numbers of animals evaluated for each group.

Table 1.

Experimental groups

| Lenti-tet-off | Histological analysis |

NT-3 ELISA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene regulation | Animals | Gene regulation | Animals | |

| NT-3 | −Dox 4 weeks | n = 8 | −Dox 4 weeks | n = 3 |

| +Dox 4 weeks | n = 9 | +Dox 4 weeks | n = 3 | |

| −Dox 4 weeks, +Dox 6 weeks | n = 10 | −Dox 2 weeks | n = 4 | |

| −Dox 10 weeks | n = 4 | −Dox 2 weeks, +Dox 3 d | n = 4 | |

| −Dox 2 weeks, +Dox 1 week | n = 4 | |||

| −Dox 2 weeks, +Dox 2 weeks | n = 4 | |||

| GFP | −Dox 2 weeks | n = 3 | ||

| +Dox 2 weeks | n = 3 | |||

| −Dox 4 weeks | n = 6 | −Dox 4 weeks | n = 3 | |

| +Dox 4 weeks | n = 6 | +Dox 4 weeks | n = 3 | |

| −Dox 4 weeks, +Dox 6 weeks | n = 4 | |||

Surgeries.

Animals were anesthetized as described above and underwent a laminectomy at C2-C3 spinal level. Dorsal funiculus lesions were made at the caudal aspect of C3 using a David Kopf Instruments microwire device as previously described (Lu et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2006). After fixation in a spinal stereotaxic unit, a small dural incision was made. The wire knife was lowered into the spinal cord to a depth of 1.1 mm ventral to the dorsal cord surface and 1.1 mm to the left of the midline. The tip of the wire knife was extruded, forming a 2.25 mm wide arc that was raised to the dorsal surface of the cord, transecting the dorsal funiculus including the ascending (sensory) and descending (corticospinal) axon tracts. To ensure complete axotomy of the entire dorsal column, spinal tissue was compressed against the microwire knife surface using a microaspiration pipette until all visible white matter was transected. Immediately following the lesion, 2 μl (∼75,000 cells/μl) of BMSC was pressure injected (Picospritzer II; General Valve) through a small hole in the dura mater into the lesion site.

Immediately following cell grafting, lentivirus expressing NT-3-GFP or GFP was injected superficially through pulled glass capillaries 2.5 mm rostral to the lesion site into the spinal cord at the midline at a depth of 0.5 and 1.0 mm (1.25 μl at each depth), at a rate of 0.5 μl/min (Taylor et al., 2006). Pipettes were left in place for 1 min after the injection and were then slowly withdrawn. To confirm that variations between virus batches do not influence experimental outcomes, at least two different batches of concentrated lentivirus were used in all groups. Immediately following vector injection, all rats unless otherwise noted, received bilateral conditioning lesions, in which the sciatic nerve was crushed at mid-thigh level with a jeweler's forceps for 15 s (Fig. 1C).

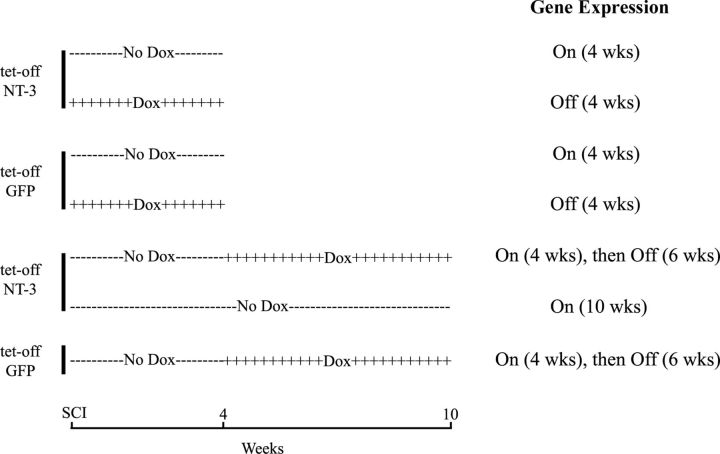

To turn gene expression off, doxycycline (Sigma) was administered in the animals' drinking water (1 mg/ml in 5% sucrose) starting either 1 d before surgeries or at the time indicated and continued for the time period specified in Table 1; to turn gene expression on, animals received drinking water without doxycycline (5% sucrose only). To determine whether NT-3 gene regulation affects axonal regeneration, animals were either treated with doxycycline for 4 weeks (gene expression off) or animals received drinking water without doxycycline (gene expression on) for the entire experimental period (Fig. 2). Subsequently, we examined whether transient NT-3 gene expression was sufficient to sustain regenerated axons. Animals injected with tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus were either untreated (gene expression turned on) for 4 weeks, or untreated for 4 weeks and then treated with doxycycline for 6 weeks (NT-3 expression first on then off) or untreated (no doxycycline) for 10 weeks (gene expression on). In addition, one group of animals received tet-off-GFP lentivirus and survived for 10 weeks, with gene expression turned on for 4 weeks (no doxycycline treatment) followed by doxycycline treatment for 6 weeks (GFP expression off) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Survival and treatment of animal for histological analysis. Survival without doxycycline treatment is indicated by minus symbols (−−−), and treatment with doxycycline in the drinking water is indicated by plus symbols (++++). To examine effects of regulatable NT-3 gene delivery on axonal regeneration, NT-3 and GFP, respectively, are continuously turned on or off for 4 weeks. To determine whether transient NT-3 gene delivery is sufficient to sustain regenerated axons, gene expression was first turned on (no doxycycline) for 4 weeks followed by doxycycline treatment for 6 weeks (−−−followed by++++).

In vivo NT-3 and GFP expression.

In vivo expression of NT-3 was examined in rat spinal cords using an NT-3-specific ELISA and GFP expression was visualized by immunolabeling. Tetracycline-regulated tet-off-NT-3 or tet-off-GFP lentivirus was injected into the spinal cord 2.5 mm rostral to a dorsal column lesion filled with BMSC as described above. Half of the animals were not treated with doxycycline (gene expression on) and half of the animals was treated with doxycycline (1 mg/ml) in the drinking water (gene expression off) (n = 3–6 per group; Table 1). After 2 weeks, some animals injected with tet-off GFP (n = 3, −Dox; n = 3, +Dox) were perfused and the cervical spinal cords were cut in the sagittal plane (30 μm section) and processed for GFP immunolabeling (see below, Tissue Processing). A different set of animals was transcardially perfused with 100 ml ice-cold 0.1 mPBS after 4 weeks. The fresh cervical spinal cord was dissected, frozen on dry ice, and the dorsal half of a 5 mm spinal cord segment located just rostral to the lesion site was used for NT-3 ELISA. Samples were lysed by sonication in lysate buffer (PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 1 mm PMSF, and 1 μl/ml aprotinin). ELISA was processed as described above. To measure the kinetics of NT-3 expression, a separate group of animals was injected with tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus as described above. A cellular graft was not included in these animals. Animals were either untreated for 2 weeks, or untreated for 2 weeks and then treated with doxycycline for 3 d, 1 week, and 2 weeks (n = 4 per group), respectively. At the end of the survival period, NT-3 levels were measured by ELISA as described above.

Transganglionic tracing of ascending sensory axons

Animals that were used for immunohistochemical analysis of sensory axon regeneration received injections of 1% cholera toxin β-subunit (CTB; 2 μl per side, List Biological Laboratories) bilaterally into the sciatic nerve at mid-thigh level 3 d before perfusion.

Tissue processing

Rats were killed by an overdose of anesthesia and transcardially perfused with 100 ml of cold 0.1 m PBS, followed by 300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Cervical spinal cords were removed, postfixed overnight, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. Sagittal sections were cut on a cryostat set at 30 μm intervals. Every seventh section was mounted on glass slides for Nissl staining, and remaining sections were processed for immunolabeling and histological analysis. All sections were processed free floating.

Immunohistochemistry

Every seventh section was triple labeled for CTB using streptavidin-HRP light-level immunohistochemistry followed by GFP and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) fluorescent immunolabeling. Goat antibody to CTB (1:80,000; List Biological Laboratories) was used to detect ascending sensory axons, a monoclonal antibody to GFAP (1:1000, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) was used to label astrocytes and rabbit anti-GFP (1:750; Invitrogen) was used to label vector-transduced cells as described previously (Taylor et al., 2006). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 15 min. Sections were blocked with 5% horse serum for 1 h at room temperature and then were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against CTB. After washing in TBS, sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:200; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 1 h incubation in avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Elite kit; 1:100, Vector Laboratories) at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine (0.05%) with nickel chloride (0.04%) was used as chromagen, with reactions sustained for 0.5–10 min at room temperature. Sections were subsequently fluorescently labeled for GFP and GFAP. Nonspecific labeling was blocked in TBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 and 5% donkey serum (blocking solution), and sections were incubated in primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4°C overnight at the following dilutions: rabbit anti-GFP (1:750; Invitrogen) and mouse anti-GFAP (1:1000; Millipore). After washing, sections double labeled for GFP and GFAP were incubated for 2.5 h with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (1:150; Invitrogen) and donkey anti-mouse Alexa 594 (1:200; Invitrogen). For other immunofluorescent labeling, the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFAP (1:750; Dako), mouse anti-neurofilament 200 (NF200; 1:500, Sigma), rabbit anti-S-100 (1:1000; Dako), mouse anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) (1:250; Millipore), mouse anti-MAP2 (1:2000; Millipore), rabbit anti-NG2 (1:200; Millipore), and mouse anti-SV2 (1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Sections double labeled for NF200 and GFAP were incubated with donkey anti-mouse Alexa 594 (1:200; Invitrogen) and anti-rabbit Alexa 647 (1:200; Invitrogen). Sections triple labeled for CTB, S-100, and GFAP were incubated with donkey anti-goat Alexa 594, anti-rabbit Alexa 350, and anti-mouse Alexa 647 (1:200). Sections triple labeled for CTB, MAG, and GFAP were incubated with donkey anti-goat Alexa 594, anti-mouse Alexa 350, and anti-rabbit Alexa 647 (1:200; Invitrogen). Sections triple labeled for CTB, MAP2, and GFAP were incubated with donkey anti-goat Alexa 594, anti-mouse Alexa 350, and anti-rabbit Alexa 647 (1:200). Sections triple labeled for CTB, NG2, and SV2 were incubated with donkey anti-goat Alexa 594, anti-rabbit Alexa 647, and anti-mouse Alexa 405 (1:200). Labeled sections were mounted and coverslipped with Cytoseal 60 mounting media (Richard Allen Scientific). Photographs were taken using a MicroFire digital camera (Optronics) connected to an Olympus AX-70 microscope. For confocal imaging, an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope was used.

Lesion completeness

Lesion completeness was evaluated by inspecting every seventh 30-μm-thick spinal cord section immunolabeled for GFAP by an examiner blinded to group identity. An incomplete interruption of GFAP-labeled astrocytes at the lesion site, in particular at the most dorsal aspect, would have indicated an incomplete lesion. In addition, the medulla was sectioned sagittally at 30 μm intervals and every seventh section was checked for CTB labeling in the nucleus gracilis at 200× and 400× magnification. Two intact animals that received CTB injections bilaterally into the sciatic nerve served as positive control. All lesions were found to be complete in all rats based on these criteria.

Quantification of axon profiles, Schwann cells, and graft/lesion size

To determine the number of CTB-labeled axons that extended into and beyond the dorsal column lesion site, one of seven serial 30 μm sagittal spinal cord sections triple labeled for CTB, GFAP, and GFP were examined under fluorescence and transmission light microscopy by an observer blinded to group identity. The outline of grafts was identified by GFAP immunolabeling. A virtual line perpendicular to the dorsal surface of the spinal cord was set in the middle of the grafts using a calibrated eyepiece. CTB-labeled axons crossing the midline were counted at 400× magnification as regenerated axons within the grafts. The rostral lesion border was defined as the region in which GFAP-labeled astrocytic cell bodies were found rostral to the lesion. Because this border was often irregular, a dorsoventral line representing the lesion edge was defined as the most rostral extent of the lesion site. A calibrated eyepiece with a scale was used to delineate regions including rostral lesion border, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1200, and 1600 μm rostral to a dorsoventral line defined as rostral lesion border. CTB-labeled axonal profiles crossing these lines and within GFAP-labeled areas were quantified at 400× magnification. Thus each axon was counted only once at each distance. CTB-labeled axonal profiles normally emerged on 3–4 sections in one series and the number of axons detected in all sections of one series was added for each animal for statistical analysis. Lesion/graft size was quantified in the same sections measuring the rostrocaudal extent of the lesion devoid of GFAP-labeling in three sections containing the largest graft and CTB-labeled axons. A calibrated eyepiece with a scale was aligned to the middle of the dorsal white matter and the distance between rostral and caudal GFAP-labeling was measured at 200× magnification. The values obtained from three sections per animal were averaged for statistical analysis.

Axon density within the graft was measured in NF-labeled sections using National Institutes of Health (NIH) ImageJ. One in 14 sections was double labeled for NF200 and GFAP and on average three sections containing a graft were quantified blindly. Grayscale photographs were acquired at 100× magnification using epifluorescent illumination and appropriate wavelength filters. Photographs of GFAP immunolabeling were used to identify and outline the graft area and the density of NF labeling was quantified in this area. Thresholding values on images were chosen such that only immunolabeled axons were measured. Nonspecific staining or labeling artifacts were edited from images. For each animal, total labeled pixels were obtained by summing labeled pixels on three individual sections, as well as total grafted area. Axon density was determined by dividing the total number of labeled pixels by the total graft area used for quantification. To confirm these results, axon profiles within the graft were also counted using the same method used for CTB-labeled axons described above in the center of the graft resulting in the same group differences (data not shown).

Schwann cell density within the graft was also measured using NIH ImageJ. One in 14 sections in randomly selected animals (3–4 per group) was triple labeled for CTB, S-100, and GFAP. Grayscale photographs were taken at 100× magnification using a fluorescent microscope. To discriminate S-100-labeled astrocytes from Schwann cells, grafts devoid of GFAP labeling were outlined in the photographs of GFAP labeling. The outlined GFAP-negative area was subsequently used in photographs of S-100 labeling. Labeling densities were calculated as described above.

For NG2 density measurements, sections were imaged by confocal microscopy using a 10× objective. All sections were imaged in the z-plane showing the strongest labeling intensity using identical confocal settings (laser intensity, gain, offset). Labeling density in the lesion site was quantified using ImageJ measuring lesion extent and labeled pixels to obtain percent labeling density. Rostral to the lesion site, a fixed area of 1 mm rostrocaudal × 0.4 mm dorsoventral within the dorsal column white matter was quantified.

Schwann cell culture and Western blots

To examine potential changes in the expression growth-promoting molecules in Schwann cells such as L1 and laminin in response to NT-3, Schwann cells were cultured with or without addition of NT-3. Primary Schwann cells were isolated from the sciatic nerve of adult F344 rats as described previously (Weidner et al., 1999). Cells (passage 4) were cultivated in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 U of penicillin G; 100 μg/ml streptomycin, Gemini BioProducts), pituitary extract (Clonetics), and forskolin (2 μm, Sigma) in 0.5% poly-d-lysine-coated flasks. For Western blots, cells were split (4.0 × 105 cells/ T25 flask) and cultivated without pituitary extract and forskolin. The medium was supplemented with NT-3 (10 ng/ml) in three flasks and three flasks were cultivated without NT-3 for 5 d. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4/0.5% SDS/150 mm NaCl/1% NP-40/1% sodium deoxycholic acid/2 mm EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitor mix (Sigma) at 4°C. After clearing at 13,000 rpm for 15 min, supernatants were normalized for protein content using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Lysates containing 20 μg protein were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer for 5 min and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked in TBS–Tween 20 (TBST) containing 5% dry nonfat milk for 1 h followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C in primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer as follows: mouse anti-L1 (1:1000; Abcam), mouse anti-laminin (1:1000; Millipore), rabbit anti-β-actin (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology). The membranes were washed in TBST and incubated for 90 min with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500;Cell Signaling Technology). Reactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's instructions (ECLplus; GE Healthcare). The density of scanned Western blots was quantified using ImageJ and densities of L1 and laminin immunoreactive protein bands were normalized to β-actin protein levels.

Statistics

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Data were compared by unpaired t tests or ANOVA and Fisher's post hoc tests. A significance criterion of p < 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Gene expression is tightly regulated in vitro and in vivo

Tetracycline-regulated lentiviral (tet-off) vector constructs were generated for the regulated expression of NT-3-GFP and GFP. All elements for tet-regulated gene expression are contained in a single lentivirus (Fig. 1). NT-3 and GFP are transcribed in the absence of doxycycline. Following administration of doxycycline, NT-3 and GFP gene expression are turned off.

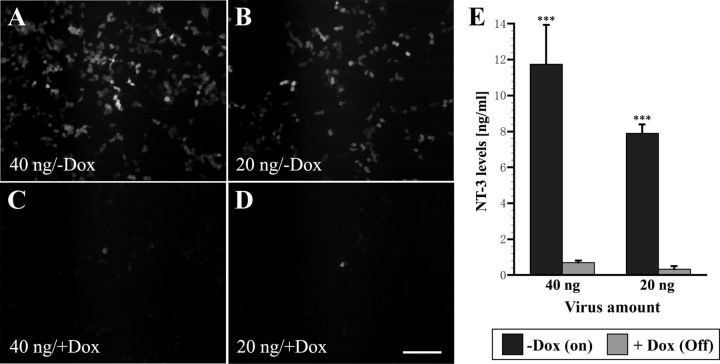

Regulation of gene expression was first examined in vitro in 293T cells transduced with tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus, which coexpresses GFP via an internal ribosome entry site. At 48 h post-transfection, numerous GFP-expressing cells were visible. Doubling the amount of virus further increased the number of GFP-positive cells. In contrast, very few GFP-positive cells were detected when cells treated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 48 h (Fig. 3A–D). For more quantitative measurement of gene regulation, NT-3 expression was examined by ELISA. Serum-free cell culture supernatants were harvested from virus-transduced 293T cells after transduction with virus (equivalent to 20 or 40 ng p24 protein). ELISA indicated that NT-3 protein levels in supernatants from cells that were not treated with doxycycline were significantly higher than the amount of NT-3 found in supernatants of cells treated with doxycycline (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3E). Comparison of NT-3 expression in cells transduced with three independent batches of virus demonstrated that NT-3 levels could be regulated on average 17.4-fold and ranged from 14.9- to 21-fold (Table 2).

Figure 3.

In vitro characterization of tet-off-NT-3 virus-transduced cells. A–D, GFP fluorescence is easily detected 48 h after transfection of 293T cells with (A) 40 ng and (B) 20 ng virus without doxycycline (−Dox) treatment, whereas only occasional GFP-positive cells are present in (C, D) wells treated with doxycycline (+Dox, 1 μg/ml). E, ELISA indicates that NT-3 levels in supernatants of cells without doxycycline are significantly higher than NT-3 levels in supernatants from cells treated with doxycycline. Scale bar, 200 μm. ***p < 0.001; ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test.

Table 2.

In vitro NT-3 levels of three independent batches of tet-off NT-3 lentivirus (ng/ml)

| Batch | Virus amount (ng by p24) | Dox | NT-3 (ng/ml) | Fold regulation (average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | − | 6.9 | 14.9 |

| + | 0.4 | |||

| 40 | − | 7.6 | ||

| + | 0.6 | |||

| 2 | 20 | − | 8.5 | 21 |

| + | 0 | |||

| 40 | − | 12.7 | ||

| + | 0.6 | |||

| 3 | 20 | − | 8.2 | 16.5 |

| + | 0.5 | |||

| 40 | − | 14.9 | ||

| + | 0.9 |

To determine whether NT-3 and GFP expression could also be regulated in vivo, lentivirus was injected into the cervical spinal cord and half of the animals were treated with doxycycline (1 mg/ml) in the drinking water to turn gene expression off. Immunolabeling for GFP in animals injected with tet-off-GFP virus demonstrated that only animals that were not treated with doxycycline showed strong GFP expression, whereas very limited and in most cases no GFP expression could be detected in the spinal cord of animals treated with doxycycline (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 4.

NT-3 and GFP expression are regulated in vivo by doxycycline administration. A, Animals that were injected with tet-off-GFP lentivirus and were untreated (−Dox) show strong GFP immunolabeling, whereas (B) only very limited and in most cases no GFP expression can be found in the spinal cord of animals treated with doxycycline for 2 weeks (+Dox, 1 mg/ml in the drinking water). C, Regulated NT-3 expression 4 weeks after tet-off-NT-3 or tet-off-GFP lentivirus injection was measured by ELISA in dissected spinal cords. Tet-off NT-3-injected animals that were not treated with doxycycline (NT-3, −Dox) show significantly higher NT-3 levels in the spinal cord than animals that were treated with doxycycline (NT-3, +Dox), and animals that received GFP virus. NT-3 levels in doxycycline-treated animals with tet-off-NT-3 virus are not significantly different from GFP virus-injected control animals. D, Kinetics of NT-3 protein levels following doxycycline administration in animals that received tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus injections. NT-3 levels are highest in animals that were not treated with doxycycline for 2 weeks (−Dox, 2 weeks). NT-3 expression decreases significantly after treatment with doxycycline for just 3 d (−/+Dox, 2 weeks/3 d). There is an additional slight but insignificant decline in NT-3 levels in the subsequent 4–11 d of doxycycline treatment (−/+Dox, 2 weeks/1 wk and −/+Dox, 2 weeks/2 weeks). NT-3 levels were measured in 5 mm spinal cord segments rostral to the lesion site. Scale bar, 500 μm. ***p < 0.001, NS p > 0.05; ANOVA, followed by Fisher's post hoc test.

NT-3 expression in the dorsal half of the spinal cord in a 5 mm segment rostral to the lesion site was analyzed by ELISA 4 weeks after virus injection. The highest NT-3 protein levels were detected in animals that received injection of tet-off-NT-3 virus in the absence of doxycycline. In contrast, NT-3 protein levels were significantly lower in doxycycline-treated animals that received tet-off-NT-3 virus and in control animals that received tet-off-GFP virus regardless of the doxycycline treatment (all p < 0.0001). The latter three groups did not differ significantly in the amount of NT-3 (Fig. 4C). Thus, NT-3 expression can be turned off in tet-off-NT-3 virus-injected animals to levels that are indistinguishable from control animals.

To determine the kinetics of NT-3 gene regulation in vivo, animals were injected with tet-off-NT-3 virus as described above. Animals were untreated (no doxycycline) for the first 2 weeks to turn gene expression on. Gene expression was then turned off for 3 d, 1 week, or 2 weeks by doxycycline administration. After 3 d of doxycycline administration, NT-3 expression was already significantly reduced (Fig. 4D; p < 0.001). NT-3 protein levels declined slightly more after 7 and 14 d of doxycycline treatment, but NT-3 levels were not statistically different when comparing animals treated with doxycycline for 3 d, 1 week, or 2 weeks. Thus, NT-3 expression is rapidly turned off following doxycycline administration.

Regulated NT-3 expression promotes axon growth across a lesion site

To examine axon regeneration in response to regulated NT-3 delivery, animals received dorsal funiculus lesions, the lesion site was filled with bone marrow stromal cells, and tet-off-NT-3 or tet-off-GFP lentivirus was injected rostral to the lesion site. Immediately after the lesion, animals underwent bilateral conditioning lesions of the sciatic nerve.

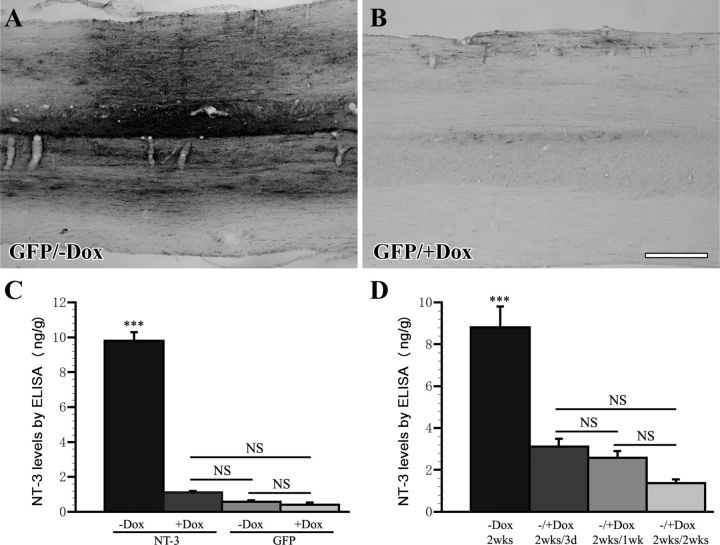

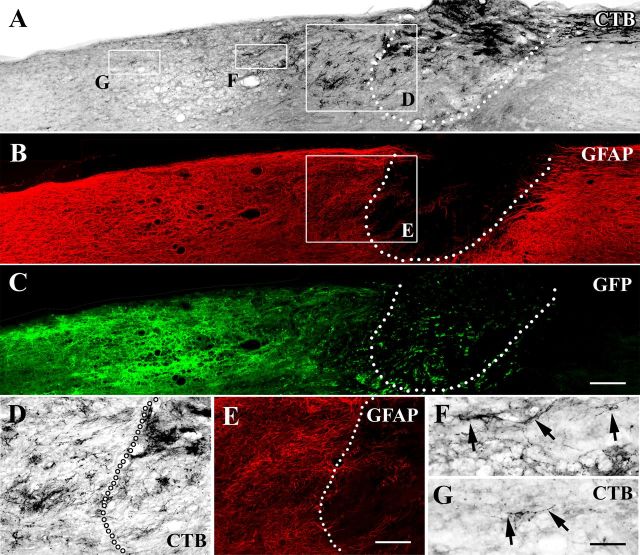

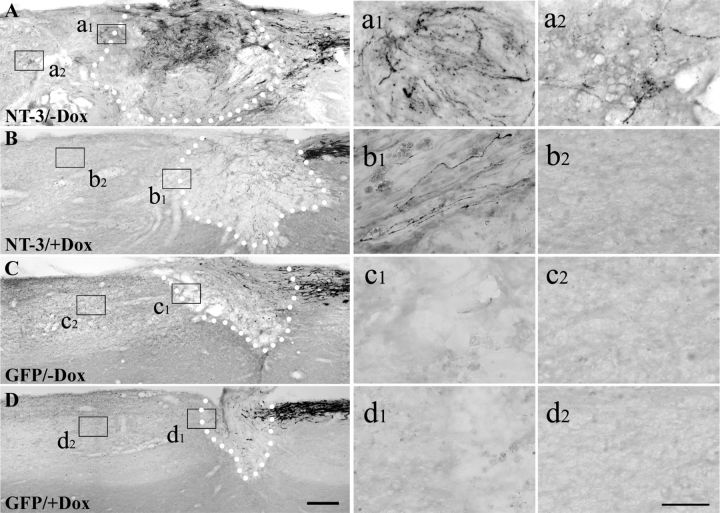

Four weeks postlesion, transganglionic tracing with CTB identified numerous ascending sensory axons penetrating the graft and extending across the rostral lesion border identified by GFAP immunolabeling when NT-3 gene expression was turned on (−Dox) (Figs. 5, 6A). Regions of axonal growth correlated with the topography of NT-3 expression recognized by GFP immunolabeling (lenti-tet-off-NT-3 constructs coexpress GFP via an internal ribosome entry site) (Fig. 5A–C). CTB-labeled axons crossing the rostral host/graft interface extended for an average maximum distance of 1.5 mm (Figs. 6A, 7C). In contrast, only occasional axons could be detected rostral to the lesion site in animals that received tet-off-NT-3 virus and were treated with doxycycline to turn gene expression off (+Dox; Fig. 6B). Similarly, virtually no axons were detected beyond the lesion site in animals that received injections of tet-off-GFP lentivirus regardless of doxycycline treatment (Fig. 6C,D).

Figure 5.

Injured sensory axons regenerate across the graft/lesion site when NT-3 expression is turned on. Triple immunolabeling for (A) CTB, (B) GFAP, and (C) GFP in a sagittal section of an animal that received lenti-tet-off-NT-3 injection 4 weeks postinjury (gene expression turned on). A, CTB-labeled ascending sensory axons extend into the cellular graft and beyond the rostral host/graft interface identified by (B, E) GFAP immunolabeling. C, NT-3 virus transduced cells identified by GFP immunolabeling are observed mostly rostral to the lesion site. D–G, Higher magnification of areas boxed in A and B shows that (D) regenerated CTB-labeled axons cross the (E) rostral border and (F, G) extend into the rostral host spinal cord (arrows). Dotted lines in A–E indicate the host/graft interface. Rostral is to the left, dorsal to the top. Scale bars: (in A) A–C, 200 μm; (in E) D, E, 100 μm; (in G) F, G, 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Axonal growth of CTB-labeled ascending sensory axons in response to regulated NT-3 expression 4 weeks postinjury. A, Numerous axons grow across the rostral host/graft border and extend into the spinal cord when NT-3 gene expression is turned on (−Dox). B, In contrast, few CTB-labeled axons penetrate the graft and grow across the lesion/graft border if NT-3 gene expression is turned off (+Dox). C, D, Axons are hardly observed beyond the rostral lesion border in animals that received GFP virus and were either (C) untreated or (D) treated with doxycycline. Dotted lines indicate the host/graft interface. Higher magnification of boxed areas in A–D are shown in a1–d1 (rostral host/graft interface) and a2–d2 (rostral to the lesion site). Scale bars: (in D) A–D, 200 μm; (in d2) a1–d2, 50 μm.

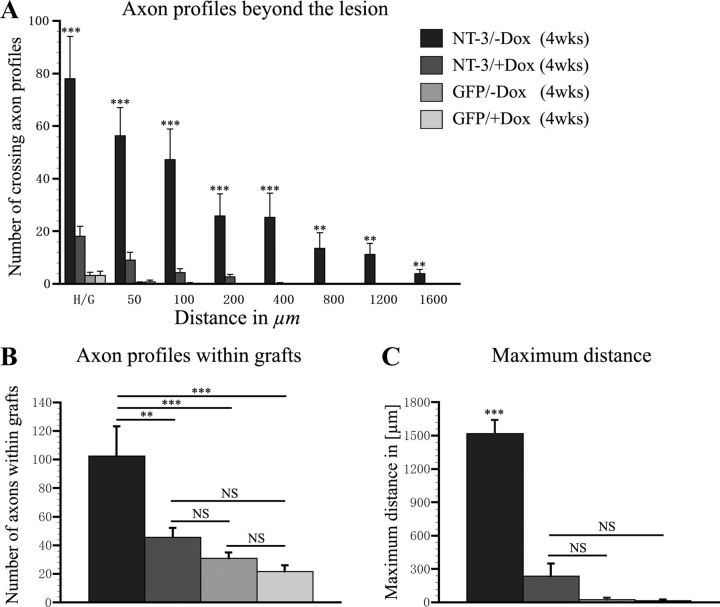

Figure 7.

Quantification of regenerated CTB-labeled sensory axon profiles within and rostral to the lesion site. A, The number of axonal profiles crossing a virtual line at the rostral host/graft interface (H/G; 0 μm) and at different distances beyond the interface (50–1600 μm) was quantified in one of seven sagittal sections. Animals that received tet-off-NT-3 virus and received no doxycycline (−Dox) exhibit significantly more axonal profiles beyond the rostral lesion border than animals that were treated with doxycycline to turn NT-3 expression off (+Dox) and control animals that received GFP virus with or without doxycycline treatment. B, Similarly, significantly more axonal profiles are present within cellular grafts in animals that received tet-off NT-3 virus when gene expression is turned on compared with all other groups. C, The maximum average distance of axon growth is also significantly higher in animals that received tet-off NT-3 virus when gene expression is turned on (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS p > 0.05; ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test).

Quantification of axon numbers within cellular grafts demonstrated significantly more axons when NT-3 expression was turned on (tet-off-NT-3; −Dox) compared with animals that were treated with doxycycline (tet-off-NT-3, +Dox; p < 0.01). The number of axons in the graft in the latter group was not different from GFP control groups (Fig. 7B). Rostral to the lesion site, the number of axonal profiles was significantly higher at all distances examined in animals with continuous NT-3 expression compared with doxycycline-treated animals injected with tet-off-NT-3 virus (NT-3 expression off) and GFP control animals (Fig. 7A). Similarly, the maximum distance of regenerated axons was significantly higher when NT-3 expression was turned on (p < 0.001 in comparison with all other groups). No statistically significant differences were detected when comparing the maximum distance of axonal regeneration between GFP control animals and doxycycline-treated animals that received tet-off-NT-3 virus (Fig. 7C).

Together, NT-3 expression can be turned off to levels that are insufficient to induce significant biological responses in vivo.

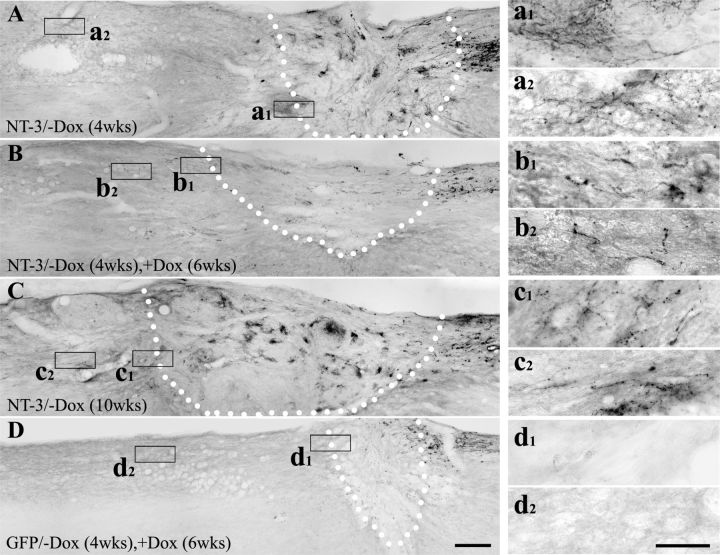

Responses of regenerated axons to transient NT-3 delivery

Next we examined whether transient NT-3 expression influences axons regenerated into and beyond the lesion site by turning NT-3 expression on (−Dox) for 4 weeks and then off (+Dox) for 6 weeks. As demonstrated above, NT-3 expression for 4 weeks enhanced growth of many fine CTB-labeled axon profiles into the lesion/graft site and many axons extended beyond the lesion into the host spinal cord (Fig. 8A). When NT-3 expression was subsequently turned off for 6 weeks, the number of CTB-labeled regenerated axons declined within the lesion site and in the rostral spinal cord (Fig. 8B). The decline in the number of axons in animals with transient NT-3 expression was not due to the extended time postlesion. Turning NT-3 expression continuously on for 10 weeks resulted in numerous CTB-labeled axons within and beyond the lesion site (Fig. 8C). Occasionally, CTB-labeled axons beyond the lesion site were associated with blood vessels as previously reported (Blesch et al., 2012), but numerous axons were also detected without direct contact to vascular profiles both in animals with continuous NT-3 expression and in animals with transient NT-3 expression. As expected, very few labeled axons were observed within the lesion in animals with transient GFP expression, and no axon extended across the rostral interface (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8.

Immunolabeling for regenerated CTB-labeled sensory axons after transient NT-3 expression. Many regenerating axons are found beyond the lesion site when NT-3 gene expression is turned on (−Dox) for (A) 4 weeks and (C) 10 weeks. B, Fewer CTB-labeled regenerated axons are observed in the graft and in the rostral spinal cord when NT-3 expression is turned on (−Dox) for 4 weeks and then turned off (+Dox) for 6 weeks. D, As expected, very few CTB-labeled axons extend into the graft and beyond the graft in animals received transient GFP gene delivery. Dotted lines indicate the host/graft interface. Higher magnification of boxed areas in A–D are shown in a1–d1 (rostral host/graft interface) and a-2–d2 (rostral to the lesion site). Scale bars: (in D) A–D, 200 μm; (in d2) a1--d2, 50 μm.

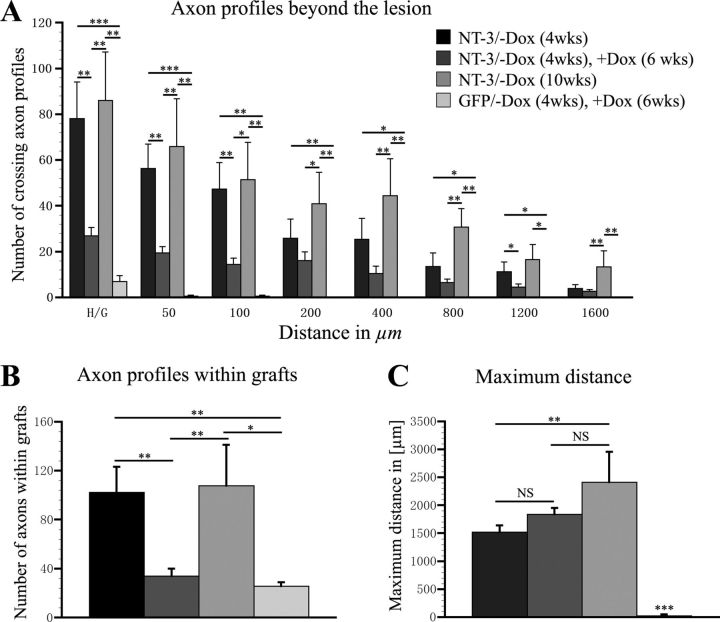

Quantification of CTB-labeled axonal profiles demonstrated a clear pattern of axonal responses to transient NT-3 delivery (Fig. 9). The number of regenerated axons declined within the lesion site and at all distances examined beyond the lesion site when comparing animals that were not treated with doxycycline for 4 weeks (NT-3 expression turned on) to animals that were first untreated (NT-3 expression turned on for 4 weeks) and then treated with doxycycline for 6 weeks to turn NT-3 expression off. Close to the lesion site, ∼65–70% of regenerated axons were lost within the 6 week time period without NT-3 expression (p < 0.01). Between 400–1200 μm beyond the lesion site regenerated axon numbers declined by ∼50%. Indeed, comparing axon numbers within the graft or beyond the lesion site between animals with transient GFP and transient NT-3 expression, no significant differences were detected. Thus, axon numbers are severely reduced approaching the number found in GFP control animals. Interestingly, the number of axonal profiles 1600 μm beyond the lesion site and the maximum growth distance was similar after 4 weeks of NT-3 expression and transient NT-3 expression (4 weeks on followed by 6 weeks off) (Fig. 9C). Ten weeks of continuous NT-3 expression significantly enhanced growth at all distance points compared with GFP control animals. As expected, only occasional axons extended beyond the lesion site in animals that received tet-off-GFP lentivirus surviving for 10 weeks (4 weeks −Dox followed by 6 weeks +Dox).

Figure 9.

Quantification of CTB-labeled axon profiles after transient NT-3 gene expression. A, The number of axonal profiles crossing the rostral host/graft interface (H/G; 0 μm) and increasing distances (50–1600 μm) beyond the lesion was quantified in one of seven sagittal sections. Compared with animals that received tet-off-NT-3 virus and no doxycycline for 4 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks), a decrease in the number of axons is evident when NT-3 expression is turned on for 4 weeks and then turned off for 6 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks, +Dox, 6 weeks). B, Animals with transient NT-3 expression also exhibit significantly fewer CTB-labeled axons within the graft compared with animals with continuous NT-3 expression for 4 weeks or 10 weeks. C, In contrast, no significant difference is observed in the average maximum distance of axon growth between animals with continuous NT-3 gene expression for 4 weeks and animals with transient NT-3 expression. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, NS p > 0.05; ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test.

Thus, particularly axons in the immediate vicinity of the lesion site seem to be affected by a reduction in NT-3 levels, whereas some axons that had regenerated for longer distances were sustained over the 6 week period when NT-3 expression was turned off.

Responses of NF-labeled axons and graft size

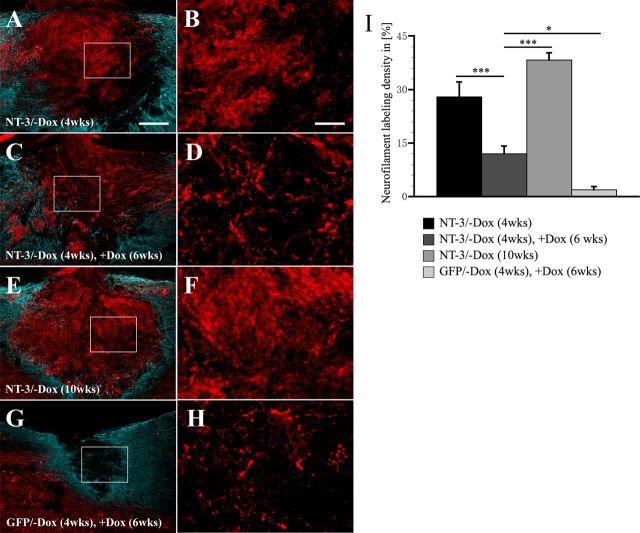

To determine whether the observed decline in axon numbers was only specific for ascending sensory neurons or also true for other NT-3 responsive axonal populations, the density of NF200-labeled axons was quantified within the lesion site. Four weeks after NT-3 gene delivery, NF200-labeled axons densely penetrated the lesion/graft site in animals injected with tet-off-NT-3 lentivirus when NT-3 expression was turned on (no doxycycline treatment; Fig. 10A,B). In contrast, fewer NF-labeled axons were observed in animals that were treated with doxycycline to turn NT-3 expression off, and in animals that received tet-off-GFP lentivirus regardless of doxycycline treatment (data not shown). Consistent with the decline in the number of CTB-labeled sensory axons, the density of NF200-labeled axons was also reduced after discontinuing NT-3 expression (Fig. 10C,D). Animals with transient NT-3 expression (4 weeks on, followed by 6 weeks off) exhibited a significantly lower density of NF-labeled axons in the lesion site than animals with continuous NT-3 gene delivery for 4 weeks (p < 0.01) or 10 weeks (p < 0.001; Fig. 10I). Even fewer NF200-labeled axons could be detected in animals with transient GFP expression (Fig. 10G,H). To exclude potential influences of lesion size on these quantification (see below), we repeated measurements of NF-labeled axons, counting the number of axons crossing a line perpendicular to the surface of the spinal cord in the center of the lesion size. These data fully confirmed our measurements of axonal density (data not shown).Together, these data not only confirm the decline in the number of CTB-labeled axons but also exclude the possibility that the reduction in NT-3 expression merely influenced the transport of the transganglionic tracer CTB.

Figure 10.

Quantification of NF-labeling density in the graft/lesion site after transient NT-3 expression. Axons (red) within the grafts are surrounded by astrocytes identified by GFAP-labeling (blue). A, B, Grafts are densely penetrated by NF-labeled axons if NT-3 gene expression is turned on for 4 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks). C, D, Axon density declines when NT-3 gene expression is turned on (−Dox) for 4 weeks and subsequently turned off (+Dox) for 6 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks, +Dox, 6 weeks). E, F, Only if NT-3 expression is continuously turned on for 10 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 10 weeks), NF-labeled axons are sustained within the lesion site. G, H, Very few axons extend into the lesion site of animals injected with tet-off-GFP virus when gene expression is turned on for 4 weeks and subsequently turned off for 6 weeks (GFP/−Dox, 4 weeks, +Dox, 6 weeks). B, D, F, H, Shows higher magnifications of areas boxed in A, C, E, and G, respectively. I, Quantification of NF-labeling density indicates a significant reduction in axon density when NT-3 gene expression is turned off. Scale bars: (in A) A, C, E, G, 200 μm; (in B) B, D, F, H, 50 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test.

The duration of NT-3 gene expression also influenced lesion size. Comparing the lesion size between tet-off Lenti-GFP virus-injected groups, we did not observe any significant difference between tet-off Lenti-GFP-injected animals that survived for 4 weeks or 10 weeks and were untreated or treated with doxycycline. Thus, doxycycline has no influence on lesion extent. Animals that received tet-off NT-3 lentivirus and were treated with doxycycline to turn gene expression off were also not significantly different from GFP virus-injected control animals. In contrast, when NT-3 expression was turned on for 4 weeks, the rostrocaudal lesion extent increased by 56–78% compared with GFP control animals. Importantly, the lesion extent was nearly identical in these animals when compared with animals with transient NT-3 expression (4 weeks turned on followed by 6 weeks without NT-3 expression). Longer periods of NT-3 expression for 10 weeks resulted in an additional 44% increase in lesion extent.

Together, long-term NT-3 expression results in gradual increase in lesion size. As the number of CTB-labeled axons in the lesion site was quantified at the center of the graft, and at different distances rostral to the lesion, the increase in lesion/graft size did not influence the quantification of regenerated axons. Indeed, the largest number of axons beyond the lesion site was found in animals with 10 weeks of NT-3 expression despite a significant increase in the lesion site.

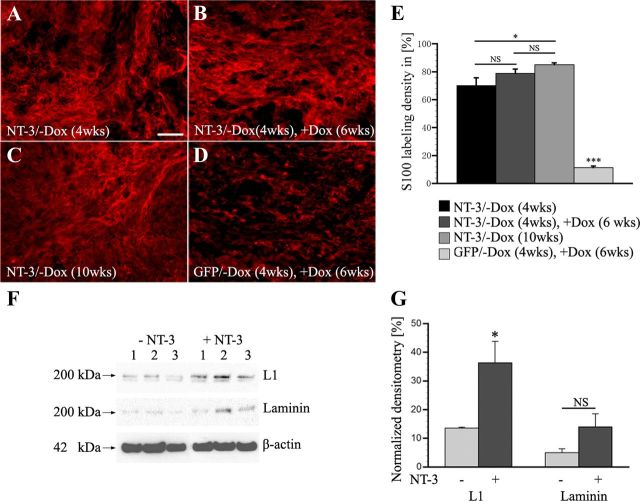

Schwann cells are sustained in the lesion site despite a decline in NT-3 levels and axonal retraction

To examine whether the number of Schwann cells infiltrating the lesion site would also decline in response to regulated NT-3 expression and thereby indirectly contribute to the observed decline in the number of regenerated axons, the density of S-100-labeled Schwann cells was quantified within the lesion/graft area (Fig. 11). Schwann cells were found in the graft/lesion site of all animals but the extent of infiltration varied among groups.

Figure 11.

Schwann cell density and protein expression after regulated NT-3 delivery. A, Numerous S-100-labeled Schwann cells are found within grafts after 4 weeks of NT-3 expression. A similar density of Schwann cells is detected after (B) an additional 6 weeks of doxycycline administration to turn NT-3 expression off. In animals with (C) 10 weeks of continuous NT-3 expression, Schwann cell density appears to further increase, whereas very few Schwann cells are found in the graft of animals with (D) transient GFP expression. E, Quantification of Schwann cell density indicates no significant (NS, p = 0.16) difference between animals with NT-3 expression turned on for 4 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks) and animals with transient NT-3 expression (NT-3/−Dox, 4 weeks, +Dox, 6 weeks). Continuous NT-3 expression for 10 weeks (NT-3/−Dox, 10 weeks) results in a slight increase in Schwann cell density compared with animals with 4 weeks of NT-3 expression (p < 0.05). Scale bar: 100 μm. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0001, NS p > 0.05; ANOVA followed by Fisher's post hoc test. F, Western blot of Schwann cells cultivated with or without NT-3 for 5 d. Levels of L1 are significantly upregulated (unpaired t test, p < 0.05) by NT-3 (10 ng/ml). Laminin protein levels are also higher in the presence of NT-3 but differences did not reach significance. G, Graph shows levels of L1 and laminin relative to β-actin levels in the presence and absence of NT-3.

Numerous S-100-labeled Schwann cells infiltrated the graft when NT-3 expression was turned on for 4 weeks (Fig. 11A). This high Schwann cell density did not decline when NT-3 expression was subsequently turned off for 6 weeks by administration of doxycycline (Fig. 11B). If NT-3 expression was continued for a total of 10 weeks, Schwann cell numbers slightly increased (Fig. 11C), whereas very few Schwann cells are found in the graft of animals with transient GFP expression (Fig. 11D). Quantification of Schwann cell density indicated no significant difference (p = 0.16) comparing animals with 4 weeks NT-3 expression and animals with transient NT-3 expression. Continuous NT-3 expression for 10 weeks resulted in a slight but significant (p < 0.05) increase in Schwann cell density compared with animals with 4 weeks of NT-3 expression, indicating a long-term effect of NT-3 provision (Fig. 11E). Based on these data, indirect effects mediated by a decline in the number of Schwann cells in the lesion site do not appear to underlie the decline in the number of regenerated axons in the lesion site.

To examine whether a decline in NT-3 might influence the expression of cell adhesion or extracellular matrix molecules and thereby contribute to the decline in axon numbers, Schwann cells were cultivated with or without NT-3 in vitro and processed for Western blotting. As previously shown for NGF (Seilheimer and Schachner, 1987), exposure to NT-3 significantly increased expression of L1 (Fig. 11F,G). Laminin protein levels were also increased but differences did not reach significance. Thus, a decline in in vivo NT-3 levels may also indirectly affect axon density by influencing Schwann cell gene expression.

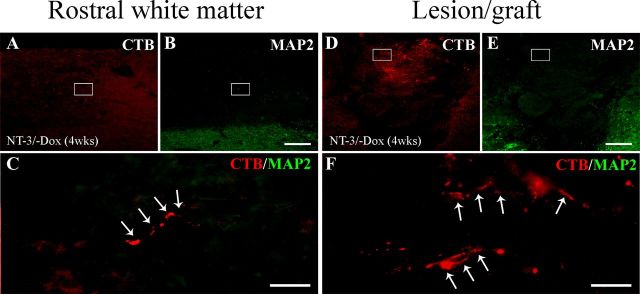

Regenerated axons do not form axodendritic synapses and are not remyelinated

Although a significant decline in the number of regenerated axons beyond the lesion site was detected, some axons were sustained. We therefore examined whether myelination or formation of synapses might contribute to the retention of some regenerated axons in animals with transient NT-3 expression.

Although numerous Schwann cells were found in the lesion site after transient NT-3 delivery (Fig. 11), triple immunolabeling for CTB, GFAP, and S-100 or MAG revealed only occasionally partially myelinated CTB-labeled axons (data not shown). Thus, remyelination does not appear to contribute to the retention of some regenerated axons.

To determine whether regenerated axons might be in contact with MAP2-labeled dendritic processes, sections were triple immunolabeled for CTB, MAP2, and GFAP. We evaluated axodendritic synapse formation of CTB-labeled regenerated axons within the graft and up to 1200 μm rostrally. MAP-2 labeling was not detected in the lesion/graft site and CTB-labeled sensory axons beyond the lesion site were never associated with MAP2-labeled processes in animals with continuous NT-3 expression for 4 weeks (Fig. 12) or in animals with transient NT-3 gene expression (data not shown). Thus, axodendritic contacts beyond the lesion site do not appear to support regenerated axons that are sustained following a decline in NT-3 expression.

Figure 12.

Regenerated sensory axons do not form axodendritic contacts. Double immunolabeling of CTB-labeled regenerated sensory axons (red, arrows) and MAP2-labeled dendrites (green) (A–C) rostral to the lesion site and (D–F) within the lesion site indicates a lack of dendrites in the vicinity of regenerated axons after 4 weeks of NT-3 expression. C, F, High magnification of boxed regions in A and B and D and E, respectively. Scale bars: A, B, D, E, 200 μm; C, F, 50 μm.

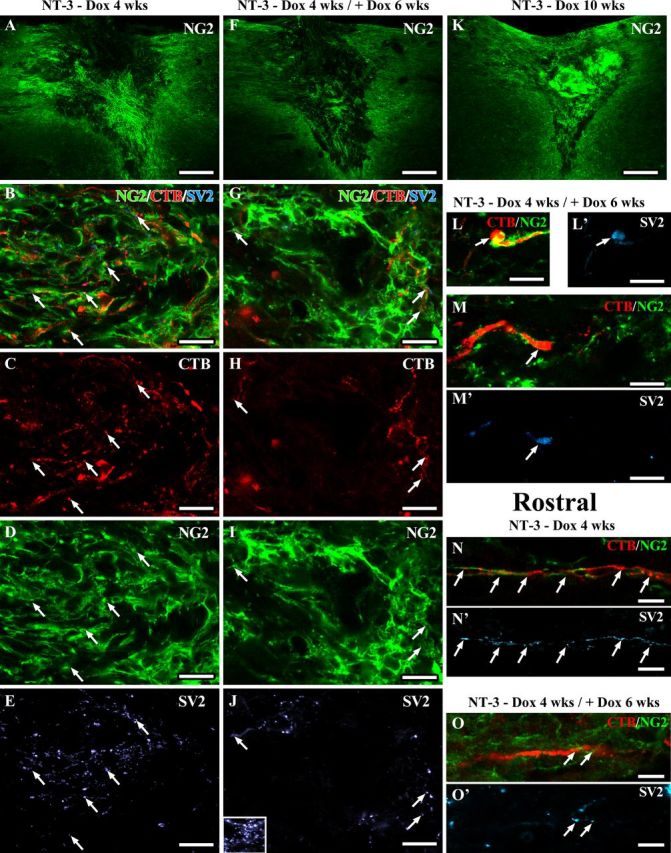

Recent studies suggest that NG2+ glia can stabilize injured sensory axons by expressing a high level of laminin and fibronectin (Busch et al., 2010). In addition, contacts between axons and NG2+ glial progenitors can differentiate into electrically coupled synapses. To examine the association between regenerated axons and NG2+ cells, a series of sections from randomly selected animals were triple immunolabeled for CTB, NG2, and the presynaptic marker SV2. As expected NG2 labeling was present within and surrounding the graft of all animals with NT-3 expression (Fig. 13). Surprisingly, quantification of NG2 labeling density within the lesion site showed lower density in animals with transient NT-3 expression (4 weeks on followed by 6 weeks off) compared with animals analyzed after 4 weeks of NT-3 expression. When NT-3 expression was turned off, NG2 labeling density declined by 60 ± 6% (p = 0.01). In contrast, in animals with continuous NT-3 expression for 10 weeks, NG2-labeling slightly increased in the lesion site by 35 ± 13% from 4 to 10 weeks (p = 0.17). Rostral to the lesion site, NG2 labeling was more variable. Animals with transient NT-3 expression and animals with continuous NT-3 expression for 10 weeks showed a reduction in labeling density when compared with animals with 4 weeks of NT-3 expression (to 68 ± 20% and 45 ± 8%, respectively; ANOVA p = 0.21).

Figure 13.

Regenerated sensory axons associate with NG2+ glia and form synapse-like contacts. Confocal images of sections triple immunolabeled for CTB-labeled sensory axons (red), NG2+ cells (green), and the presynaptic marker SV2 (light blue). Low-magnification overview of NG2 labeling in and around the lesion site shows higher NG2 labeling in the graft of animals with (A) 4 weeks or (K) 10 weeks of NT-3 expression compared with animals with (F) transient NT-3 expression (six weeks after reduction of NT-3 levels). Numerous regenerated axons are closely associated with NG2+ cells in (B–M) the graft and in (N–O) the rostral white matter. NG2 and CTB- and SV2-labeling density is higher in (A–E) grafts of animals with continuous NT-3 expression for 4 weeks compared with(F–J) animals with transient NT-3 expression. Inset in J shows SV2 labeling in gray matter as positive control. Arrows indicate SV2 labeling colocalizing with CTB-labeled axons adjacent to NG2+ glia. L, M, Six weeks after reduction of NT-3 expression, SV2-labeling is particularly strong in CTB-labeled axons with an end bulb-like appearance surrounded by NG2+ glia. SV2 labeling is also present in (N, O) regenerated CTB-labeled sensory axons associated with NG2+ glia rostral to the lesion site. Scale bars: A, F, K, 226 μm; B–E, G–M, 10 μm; N–O, 5 μm.

Colocalization of NG2 and CTB and SV2 showed that many CTB-labeled axons were in close contact with NG2+ cells. Interestingly, a high density of punctuate SV2 labeling was observed within the lesion/graft site when NT-3 expression was turned on. SV2 labeling partially colocalized with CTB-labeled axons that were in close proximity to NG2+ glia. Upon doxycycline treatment and reduction of NT-3 expression, SV2 labeling declined consistent with the observed reduction in the number of axons in the graft/lesion site and the reduction in NG2 labeling. Many but not all CTB-labeled axonal profiles that had regenerated beyond the lesion site and were sustained after transient NT-3 expression were also closely associated with NG2+ cells and contained punctuate SV2 labeling. However, CTB-labeled axons in the absence of SV2 and associated NG2 were also observed. CTB-labeled axonal enlargements resembling retraction bulbs were sometimes engulfed by NG2+ cells and colocalized with dense SV2 labeling. Together, these data suggest that a decline in NG2+ glia and axoglial synapses may also contribute to the retraction of regenerated axons.

Discussion

In the adult injured spinal cord, sensory axon regeneration in response to NT-3 gene delivery has been shown to depend on the spatial distribution of NT-3 expression. Regenerating axons specifically associate with regional and localized sources of NT-3 (Taylor et al., 2006) and can reinnervate their original target, the nucleus gracilis, if axons are chemotropically guided to their target area (Alto et al., 2009). We now present the first evidence that growth and persistence of regenerating sensory axons is also influenced by the temporal availability of NT-3.

Using a tetracycline-regulated (tet-off) expression system, NT-3 levels can be regulated in vitro and in vivo by doxycycline administration and kinetics of NT-3 gene regulation indicate a rapid decline of NT-3 protein levels following doxycycline administration. Robust axonal regeneration is observed within cellular grafts and beyond the lesion site if NT-3 expression is turned on for 4 weeks, consistent with previous data using constitutive NT-3 gene delivery (Taylor et al., 2006; Alto et al., 2009; Blesch et al., 2012). In contrast, very little axonal growth is evident when NT-3 is turned off, and axon growth is not significantly different from doxycycline treated or untreated GFP control animals. Importantly, the majority of CTB-labeled regenerated sensory axons, in particular those regenerated for short distances into and across the lesion, are not sustained when NT-3 expression is first turned on for 4 weeks and then turned off for 6 weeks. Only some axons that regenerated over a longer distance are preserved after turning NT-3 expression off. Similarly, examining responses of NF200-labeled axons representing a wider spectrum of NT-3-responsive projections, a dramatic reduction in the density of axonal profiles is observed within the graft once NT-3 expression is turned off. Together, these findings indicate that transient NT-3 expression is insufficient to sustain all NT-3 responsive axons that have extended into and beyond a site of SCI.

These findings are surprising for two reasons: (1) Our previous studies have demonstrated that axons, which extend into cellular BDNF-producing grafts become independent of high BDNF levels and can be sustained when BDNF is turned off (Blesch and Tuszynski, 2007) and (2) axonal responses to declining NT-3 levels would be expected to occur independent of regeneration distance. Indeed, one might predict that a decline in growth-promoting signals would affect all axons that have extended beyond the lesion site due to the inhibitory environment in the lesioned spinal cord, and would not or to a lesser degree affect axons present in the more favorable environment of the graft/lesion site. Beyond the lesion site, abundant growth inhibitory factors including chemorepellents (McKeon et al., 1991), inhibitory extracellular matrix (Silver and Miller, 2004), myelin-associated inhibitors (Filbin, 2003), and activated macrophages (Horn et al., 2008; Busch et al., 2009, 2011) create an environment that favors axonal dieback. Within the lesion site, the presence of numerous Schwann cells favors axonal growth. Schwann cells can produce low levels of neurotrophic factors, including NGF, BDNF, and NT-3 (Heumann et al., 1987; Funakoshi et al., 1993; Naveilhan et al., 1997), extracellular matrix, and cell adhesion molecules that support axonal growth. We therefore speculated that the large number of Schwann cells that continue to fill the lesion site after transient BDNF delivery contributed to a lack of axonal dieback following a decline in BDNF levels in our previous studies (Blesch and Tuszynski, 2007). However, the current study indicates that merely the presence of Schwann cells is insufficient to support axons that have extended into the lesion site. Despite the continuous presence of a comparable number of Schwann cells in the lesion site, a decline in CTB and NF200-labeled axons is observed in the lesion site indicating that the decline in regenerated axons in the grafts is not due to a change in Schwann cell infiltration. However, our in vitro data indicate that NT-3 can regulate expression of extracellular matrix and cell adhesion molecules in Schwann cells confirming previous studies of Schwann cell responses to NGF (Seilheimer and Schachner, 1987). Thus, indirect effects may also influence axonal growth. Differences in Schwann cell responses and in axonal populations responding to BDNF and NT-3 might be one explanation for the decline in axon numbers that was observed in the current and not in our previous study. Alternatively, a tighter regulation in gene expression at the lesion site in the current study may have influenced the different outcomes.

Regulatable NT-3 virus was injected 2.5 mm rostral to the lesion site to generate a gradient of NT-3 protein when gene expression is turned on with highest NT-3 concentrations at the virus injection site and declining levels toward the lesion (Taylor et al., 2006). Once transgene expression is turned off, an overall 5- to 10-fold reduction in NT-3 levels is achieved (Fig. 4). Residual NT-3 expression from a slight leakiness of the tet-off system is likely to be highest at the virus injection site, where the largest number of transduced cells are found and lowest within and close to the lesion site. Indeed, GFP-positive cells indicating virus-transduced NT-3 expressing cells were not detected in the lesion site upon doxycycline administration but some lightly labeled GFP-positive cells could be detected close to the virus injection site. Thus, a nearly complete shut off in NT-3 expression might underlie the decline in the number of regenerated axons observed within and close to the lesion site. Closer to the virus injection site, leakiness in the tetracycline-regulated expression might provide some residual NT-3, which is insufficient to induce axonal regeneration but sufficient to sustain regenerated axons.

In summary, even an otherwise favorable environment (Schwann cells in the graft/lesion site) appears to be insufficient to sustain regenerated axons once neurotrophin levels severely decline, and despite an inhospitable environment (distal host tissue), persisting low neurotrophin levels are sufficient to sustain some regenerated axons.

The decline in NT-3 expression may have also resulted in pruning of collaterals within and close to the lesion site whereas some axon shafts were sustained. NT-3-mediated axon growth via collateral branching has been reported for other axonal populations including corticospinal axons (Schnell et al., 1994; Grill et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2006). High levels of NT-3 might induce regeneration and formation of collateral branches by injured sensory axons whereas declining NT-3 levels would result in degeneration of axon collaterals. Indeed, many axonal profiles penetrating the graft in the first 4 weeks when NT-3 expression was turned on appeared to have a small diameter and fine morphology extending radially without rostrocaudal orientation. Once NT-3 expression was turned off for 6 weeks, remaining CTB-labeled axons appear to have a larger caliber and many axons were located in the most dorsal aspect of the spinal cord.

Although regenerated axons did not form axodendritic synapses indicated by an absence of MAP2/CTB colocalization, the presynaptic marker SV2 was detected in CTB-labeled axons within and beyond the lesion site. Synapse-like contacts between NG2+ glia and axons have been shown during development (Kukley et al., 2007; Ziskin et al., 2007), in the adult hippocampus (Bergles et al., 2000) and after demyelinating lesion (Etxeberria et al., 2010). During the differentiation of NG2+ glia into oligodendrocytes, these neuron-NG2 synapses are lost as oligodendrocytes mature (for review, see Mangin and Gallo, 2011). NG2+ glia may also stabilize injured sensory axons by expressing a high level of laminin and fibronectin (Busch et al., 2010) and axon-glia synapses could provide one additional mechanism influencing the persistence of regenerated axons after NT-3 expression is turned off. Influences of NT-3 on NG2-expressing glia have previously been reported. Continuous expression of NT-3 in grafts of bone marrow stromal cells results in cellular hypertrophy in the lesion site and dense NG2 immunolabeling. In these studies, ascending sensory axons also colocalized with NG2-expressing cells, most likely Schwann cells, within the graft. (Lu et al., 2007). The increase in lesion/graft size after continued NT-3 expression observed in the present study might be due to continuous infiltration and/or proliferation of Schwann cells. Proneurotrophin-mediated neural cell death as a result of high neurotrophin expression and insufficient processing could also have contributed to loss of CNS tissue (Lee et al., 2001). In addition to their role in cell death, proneurotrophins have recently been shown to induce growth cone collapse and retraction (Deinhardt et al., 2011). While we have no evidence for proneurotrophin-mediated axon retraction, declining NT-3 levels and accompanying cellular changes might change the ratio of pro-NT-3 to mature NT-3 and thereby contribute to a decline in the number of regenerated axons.

For axonal regeneration to become meaningful, the formation of new axodendritic synapses is required. During nervous system development, an initial phase involving neuronal genesis and generation of axonal projections is followed by a regressive phase, in which appropriate nascent axons are activated and enforced by neuronal activity whereas synaptically inappropriate axons or branches are pruned to match physiological requirements (Raff et al., 2002; Luo and O'Leary, 2005; Nikolaev et al., 2009). These naturally occurring events help to refine and ultimately sculpt neuronal circuitry. In the adult injured spinal cord, the retraction of regenerated axons after reduction of high NT-3 levels mimics axonal pruning events during development. The distance of sensory axon regeneration after C3 lesions is insufficient to reach the original target (nucleus gracilis), and axons are exclusively found in dorsal column white matter or within cellular grafts, areas devoid of dendritic processes. Functional recovery is therefore unlikely but was not assessed in the present study. Assuming that similar mechanisms are active in the developing and regenerating nervous system, the formation of new axodendritic synapses might be required for regenerated axons to become independent of elevated neurotrophin levels and to prevent disuse-related degeneration. Future studies using regulated expression in the target of dorsal column sensory axons, the nucleus gracilis, might be able to address this question.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS054883), Wings for Life, and the European Community (IRG268282) (A.B.) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (161456) (S.H.).

References

- Alto LT, Havton LA, Conner JM, Hollis ER, 2nd, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Chemotropic guidance facilitates axonal regeneration and synapse formation after spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1106–1113. doi: 10.1038/nn.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi SA, Stokes D, Augelli BJ, DiGirolamo C, Prockop DJ. Engraftment and migration of human bone marrow stromal cells implanted in the brains of albino rats–similarities to astrocyte grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3908–3913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergles DE, Roberts JD, Somogyi P, Jahr CE. Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nature. 2000;405:187–191. doi: 10.1038/35012083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A. Lentiviral and MLV based retroviral vectors for ex vivo and in vivo gene transfer. Methods. 2004;33:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Cellular GDNF delivery promotes growth of motor and dorsal column sensory axons after partial and complete spinal cord transections and induces remyelination. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:403–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.10934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Transient growth factor delivery sustains regenerated axons after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10535–10545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1903-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesch A, Lu P, Tsukada S, Alto LT, Roet K, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Tuszynski MH. Conditioning lesions before or after spinal cord injury recruit broad genetic mechanisms that sustain axonal regeneration: superiority to camp-mediated effects. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Horn KP, Silver DJ, Silver J. Overcoming macrophage-mediated axonal dieback following CNS injury. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9967–9976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1151-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Hawthorne AL, Bai L, Miller RH, Silver J. Adult NG2+ cells are permissive to neurite outgrowth and stabilize sensory axons during macrophage-induced axonal dieback after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:255–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3705-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Hamilton JA, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Cutrone R, Lehman N, Deans RJ, Ting AE, Mays RW, Silver J. Multipotent adult progenitor cells prevent macrophage-mediated axonal dieback and promote regrowth after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:944–953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3566-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Zhou L, Shine HD. Expression of neurotrophin-3 promotes axonal plasticity in the acute but not chronic injured spinal cord. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1254–1260. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan M, Befort K, Karchewski L, Griffin RS, D'Urso D, Allchorne A, Sitarski J, Mannion JW, Pratt RE, Woolf CJ. Replicate high-density rat genome oligonucleotide microarrays reveal hundreds of regulated genes in the dorsal root ganglion after peripheral nerve injury. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt K, Kim T, Spellman DS, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Neubert TA, Chao MV, Hempstead BL. Neuronal growth cone retraction relies on proneurotrophin receptor signaling through Rac. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra82. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria A, Mangin JM, Aguirre A, Gallo V. Adult-born SVZ progenitors receive transient synapses during remyelination in corpus callosum. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:287–289. doi: 10.1038/nn.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbin MT. Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi H, Frisén J, Barbany G, Timmusk T, Zachrisson O, Verge VM, Persson H. Differential expression of mRNAs for neurotrophins and their receptors after axotomy of the sciatic nerve. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:455–465. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Bonin AL, Freundlieb S, Bujard H. Inducible gene expression systems for higher eukaryotic cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1994;5:516–520. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Müller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill R, Murai K, Blesch A, Gage FH, Tuszynski MH. Cellular delivery of neurotrophin-3 promotes corticospinal axonal growth and partial functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5560–5572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05560.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heumann R, Lindholm D, Bandtlow C, Meyer M, Radeke MJ, Misko TP, Shooter E, Thoenen H. Differential regulation of mRNA encoding nerve growth factor and its receptor in rat sciatic nerve during development, degeneration, and regeneration: role of macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:8735–8739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn KP, Busch SA, Hawthorne AL, van Rooijen N, Silver J. Another barrier to regeneration in the CNS: activated macrophages induce extensive retraction of dystrophic axons through direct physical interactions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9330–9341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya K, Tsukada S, Lu P, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Filbin MT, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Combined intrinsic and extrinsic neuronal mechanisms facilitate bridging axonal regeneration one year after spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2009;64:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukley M, Capetillo-Zarate E, Dietrich D. Vesicular glutamate release from axons in white matter. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:311–320. doi: 10.1038/nn1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. 2001;294:1945–1948. doi: 10.1126/science.1065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Yang H, Jones LL, Filbin MT, Tuszynski MH. Combinatorial therapy with neurotrophins and cAMP promotes axonal regeneration beyond sites of spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6402–6409. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1492-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]