Summary

Background and objectives

The association between mortality and physical activity based on self-report questionnaire in hemodialysis patients has been reported previously. However, because self-report is a subjective assessment, evaluating true physical activity is difficult. This study investigated the prognostic significance of habitual physical activity on 7-year survival in a cohort of clinically stable and adequately dialyzed patients.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A total of 202 Japanese outpatients who were undergoing maintenance hemodialysis three times per week at the hemodialysis center of Sagami Junkanki Clinic (Japan) from October 2002 to February 2012 were followed for up to 7 years. Physical activity was evaluated using an accelerometer at study entry and is expressed as the amount of time a patient engaged in physical activity on nondialysis days. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess the contribution of habitual physical activity to all-cause mortality.

Results

The median patient age was 64 (25th, 75th percentiles, 57, 72) years, 52.0% of the patients were women, and the median time on hemodialysis was 40.0 (25th, 75th percentiles, 16.8, 119.3) months at baseline. During a median follow-up of 45 months, 34 patients died. On multivariable analysis, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality per 10 min/d increase in physical activity was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.66–0.92; P=0.002).

Conclusions

Engaging in habitual physical activity among outpatients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis was associated with decreased mortality risk.

Introduction

The mortality rate among hemodialysis (HD) patients is very high despite continual improvements in dialysis technology. To date, specified determinants of mortality in maintenance HD patients include older age, body mass, comorbid conditions, and markers of nutrition and inflammation (1–4). Previous studies have established the strong benefits of increased habitual physical activity on mortality in the general population, older patients with cardiovascular disease, and patients with CKD (5–8). Although an association of physical activity with mortality in HD patients has been previously reported (9–12), these studies based their definitions of physical activity on self-report questionnaires. Because self-reports are subjective assessments, it is difficult to provide a firm basis for elucidating the association between the true status of habitual physical activity and survival in HD patients.

Measuring habitual physical activity with an accelerometer during patients’ routine daily activities is recommended by Tudor-Locke et al. and Johansen et al. (13,14). This simple method, which is validated and widely used in sports and preventive medicine (13,15), accurately assesses habitual physical activity. Recent studies that measured the habitual physical activity of HD patients with accelerometers or pedometers (14,16–18) have shown that physical activity is significantly lower in HD patients than in age-matched healthy controls (16,17) and that physical activity in HD patients declines gradually (19). Kutsuna et al. reported that maintaining a high level of physical activity in daily living for HD patients is important for preventing the deterioration of walking ability (20). Additionally, increasing physical activity improves exercise tolerance and quality of life (21,22). However, the association between the true status of habitual physical activity and mortality remains unclear in HD patients.

In this study, we investigated the prognostic significance of habitual physical activity, which was evaluated using an accelerometer, on survival in a cohort of clinically stable and adequately dialyzed patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Clinically stable outpatients seen at the Department of HD Center at Sagami Junkanki Clinic from October 2002 to February 2012 were assessed for their eligibility to be included in this prospective study. Patients were undergoing maintenance HD therapy three times a week, which is most common in Japan according to data from the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. Patients were excluded from our study if they had been hospitalized within 3 months before the study; had recently sustained a myocardial infarction or angina pectoris; had uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmias, hemodynamic instabilities, uncontrolled hypertension, or renal osteodystrophy with severe arthralgia; or needed assistance in walking from another person. This study was approved by the Kitasato University Allied Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee. The physicians obtained oral consent from all patients.

Demographic and Clinical Factors

Information on demographic factors (age, sex, time on HD), physical constitution (body mass index [BMI]), primary kidney disease, and comorbid conditions (cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus) was collected at study entry. Serum albumin levels and serum C-reactive protein levels were obtained from patient hospital charts. To quantify comorbid illnesses in this study, we used a comorbidity index developed for dialysis patients (composed of primary causes of ESRD; atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, dysrhythmia, and other cardiac diseases; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; gastrointestinal bleeding; liver disease; cancer; and diabetes). This score was calculated using the method previously described and performed in analysis of survival in HD patients (23).

Habitual Physical Activity

A uniaxial accelerometer (Lifecorder; Suzuken Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) was used to measure patients’ habitual physical activity. The device obtains objective information on physical activity patterns because it can continuously measure the intensity, duration, and frequency of activities. The accuracy and reliability of the instrument have been reported in previous studies (24,25). The vector magnitude in the vertical direction that was recorded for every 2-minute period was digitally divided into 11 grades of 0, 0.5, or 1–9, with each grade reflecting the intensity of the physical activity, as described elsewhere (26). Briefly, grades 0 and 0.5 represent such activities as reading, eating, or standing, and grades 1–9 represent activities range from gentle walking to running in succession. The monitor does not capture such activities as use of a stationary cycle. Such activities were confirmed via interview at each patient visit.

In this study, habitual physical activity was evaluated at study entry using an accelerometer; it was calculated as the sum of time patients were engaged in physical activity of grade 1 or higher intensity. The accelerometer also recorded the number of steps. The instrument was worn around the waist, and it measured motion as the acceleration of the body. Patients were instructed to wear the accelerometer continuously during their waking hours for 7 days and to avoid getting it wet, such as during bathing. Patients were asked to maintain their typical weekly schedules. To ensure that the measurement periods were typical of their weekly activity patterns, we excluded data obtained when patients traveled or had acute illness.

Before the analysis, the accelerometer data were inspected to ensure that there were no obvious errors, such as a failure to acquire data or if the patient forgot to wear the accelerometer. The measurements from 4 nondialysis days during the week were analyzed.

Statistical Analyses

Data were presented as median (25th, 75th percentiles) or number (percentage) and were tested by Mann-Whitney U test or chi-squared test. We used the physical activity time as the index of physical activity because it was easily generalizable to daily practice. Rather than dividing physical activity of grade 1 or higher intensity into several groups using quartile or tertile, we evaluated them together on the basis of our clinical practice, where most of the HD patients were involved in light-intensity activities (grade 1–3). A multivariable analysis was performed by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the independent prognostic effect of physical activity time on survival after adjustment for confounders. Within the present study population, there were 34 all-cause deaths, which allowed for a maximum of three variables to be included in the multivariable regression model. To avoid overfitting, all potential confounding factors of physical activity time (which include age, sex, BMI, time on HD, comorbidity score, and serum albumin and serum C-reactive protein levels) were reduced to one composite characteristic by applying a propensity score (27). The propensity score was estimated by a multiple linear regression analysis. For the Kaplan-Meier estimate of the survival curves, we truncated the data for the 7-year follow-up period so that the number at risk was not too small. Patients were categorized into two physical activity groups by a physical activity cutoff value of 50 min/d, and the difference between groups was tested using a log-rank test. This cutoff value predicted whether the HD patients could reach the gait speed obtained by age-matched healthy adults in a previous study (20). The 7-year cumulative survival probability was estimated using the life table method with the interval length set at 1 month. P values of 0.05 or less were used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 12.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Habitual Physical Activity

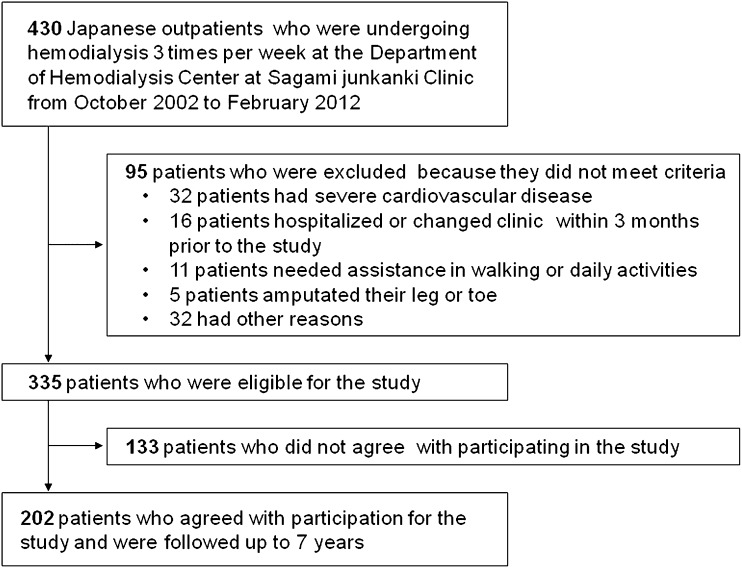

Four hundred thirty Japanese outpatients were assessed for their eligibility for inclusion. Ninety-five patients not satisfying the inclusion criteria were excluded; 133 patients declined to participate in the study. As a result, a total of 202 HD patients were recruited (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection and exclusion process.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The patients consisted of 97 men and 105 women age 35–88 years (median age, 64 years). The time on HD was 40.0 (25th, 75th percentiles, 16.8, 119.3) months at baseline. The most common underlying kidney diseases in the HD patients was GN (33.2%), and the next most common was diabetic nephropathy (32.7%). The comorbidity score was 4.0 (25th, 75th percentiles, 2.0, 7.0). Ninety-nine percent of patients were involved in grade 1–3 physical activity. The duration of physical activity for all patients was 42.7 (25th, 75th percentiles, 22.8, 65.8) min/d. The number of steps was 3925 (25th, 75th percentiles, 2287, 6244). No patients except one ever participated in cycling.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and habitual physical activity at baseline

| Characteristic | Total (n=202) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 64 (57, 72) |

| Women | 105 (52.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.0 (19.0, 23.0) |

| Time on hemodialysis (mo) | 40.0 (16.8, 119.3) |

| Primary kidney disease | |

| GN | 67 (33.2) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 66 (32.7) |

| Hypertension | 17 (8.4) |

| Polycystic renal disease | 7 (3.5) |

| Other nephropathies | 45 (22.3) |

| Comorbid condition | |

| Cardiac diseasea | 100 (49.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 78 (38.6) |

| Comorbidity score | 4.0 (2.0, 7.0) |

| Laboratory values | |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (3.7, 4.1) |

| Serum C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.3) |

| Physical activity time (min/d) | 42.7 (22.8, 65.8) |

| <10 | 18 (8.9) |

| ≤10 and <30 | 44 (21.8) |

| ≤30 and <50 | 65 (32.1) |

| ≤50 and <70 | 30 (14.9) |

| ≤70 and <90 | 24 (11.9) |

| ≥90 | 21 (10.4) |

| Number of steps | 3925 (2287, 6244) |

Values are expressed as median (25th, 75th percentiles) or number (percentage) of patients.

History of coronary disease, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, or other cardiac diseases.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients according to physical activity time (<50 min/d and ≥50 min/d). The patients in the ≥50 min/d group were significantly younger than those in the <50 min/d group (P<0.001). The comorbidity score in the ≥50 min/d group was significantly lower than that in the other group (P=0.03). Other baseline characteristics did not significantly differ between groups.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in patients exercising <50 min/d and ≥50 min/d

| Characteristic | Physical Activity Time | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <50 min/d (n=127) | ≥50 min/d (n=75) | ||

| Age (yr) | 67 (59, 74) | 62 (55, 67) | <0.001 |

| Women | 64 (50.4) | 41 (54.7) | 0.56 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.1 (19.1, 23.5) | 20.9 (18.8, 22.7) | 0.30 |

| Time on hemodialysis (mo) | 38.0 (15.7, 115.0) | 46.0 (19.8, 127.8) | 0.36 |

| Primary kidney disease | 0.21 | ||

| GN | 36 (28.3) | 31 (41.4) | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 47 (37.0) | 19 (25.3) | |

| Hypertension | 10 (7.9) | 7 (9.3) | |

| Polycystic renal disease | 3 (2.4) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Other nephropathies | 31 (24.4) | 14 (18.7) | |

| Comorbid condition | |||

| Cardiac diseasea | 63 (49.6) | 37 (49.3) | 0.97 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (40.2) | 27 (36.0) | 0.56 |

| Comorbidity score | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 0.03 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (3.7, 4.1) | 3.9 (3.7, 4.1) | 0.18 |

| Serum C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.09 |

Values are expressed as median (25th, 75th percentiles) or number (percentage) of patients.

History of coronary disease, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, or other cardiac diseases.

Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Patient Survival

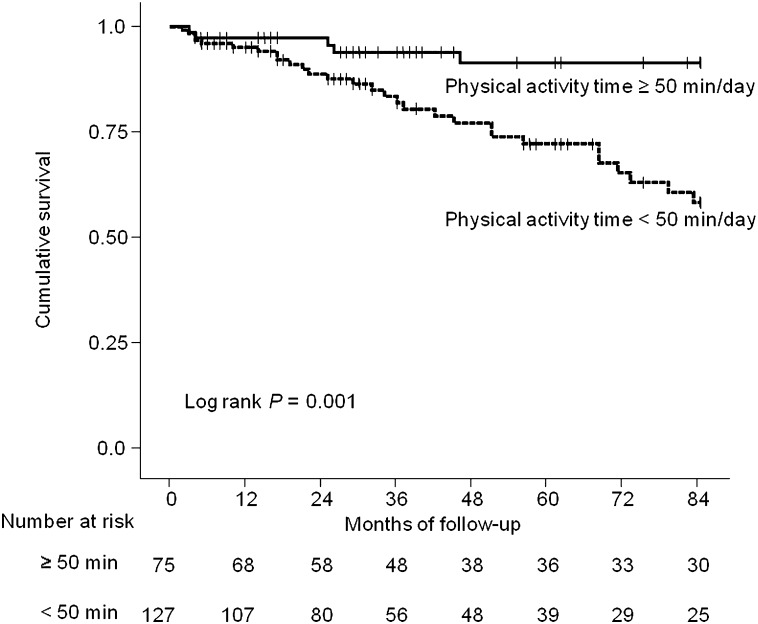

Patients were followed for up to 7 years. The overall follow-up durations ranged from 2 to 84 months (mean, 45 months). A total of 34 patients were dead at the end of the follow-up: 19 of cardiovascular disease, 5 of infection, 2 of cancer, 1 of cerebral vascular disease, 1 of gastroenterologic disease, and 6 of unknown causes. The 7-year cumulative survival rates were 93.3% in the ≥50 min/d group and 77.2% in the <50 min/d group. More than half of patients in each group were alive at the end of follow-up. Twenty-five percent of the patients with lower physical activity time died after 51 months. On the other hand, the mortality rate of patients with greater physical activity time at the end of the follow-up was less than 25%. This finding indicates superior survival in patients with greater physical activity time (P=0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival for 202 hemodialysis patients. Patients with physical activity time above the median value of 50 min/d (thick dark line) at baseline had significantly better survival than those with lower values (dotted line) (P=0.001 by log-rank test).

Effect of Physical Activity Time on Survival with Multivariable Analysis

With a Cox proportional hazards model, the crude hazard ratio (HR) of physical activity time increased per 10 min/d was 0.72 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62–0.85; P<0.001), which indicated that maintaining physical activity at a higher level was associated with reduction in all-cause mortality (Table 3). After adjustment for the effect of age, sex, BMI, time on HD, comorbidity score, and serum albumin and C-reactive protein levels, the HR changed to 0.78 (95% CI, 0.65–0.93; P=0.006). An analysis with the propensity score, performed to adjust for the effect of physical activity time by transforming all other confounding variables into a single estimator, revealed that after the adjustment, greater physical activity time still conferred a significant survival benefit (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66–0.92; P=0.002).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis for the effects of physical activity time on survival

| Variable | Units of Increase | Univariable Analysisa | Multivariable Analysis: Model 1b | Multivariable Analysis: Model 2c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Physical activity time | 10 min/d | 0.72 (0.62–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.65–0.93) | 0.006 | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | 0.002 |

| Age | 1 yr | 1.08 (1.04–1.11) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.04 | – | – |

| Women (versus men) | – | 0.67 (0.34–1.32) | 0.24 | 0.84 (0.40–1.76) | 0.65 | – | – |

| Body mass index | 1 kg/m2 | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.25 | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | 0.49 | – | – |

| Time on hemodialysis | 1 mo | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.65 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.36 | – | – |

| Comorbidity score | 1 | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | <0.001 | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 0.11 | – | – |

| Serum albumin | 0.1 g/dl | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | 0.22 | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 0.23 | – | – |

| Serum C-reactive protein | 0.1 mg/dl | 1.09 (1.05–1.12) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.05–1.13) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Propensity score | – | – | – | – | – | 0.63 (0.47–0.85) | 0.002 |

Analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Unadjusted by clinicopathologic factors on survival.

Adjusted by age, sex, body mass index, time on hemodialysis, comorbidity score, and levels of serum albumin and C-reactive protein.

Adjusted by applying a propensity score, which is a conditional probability of expressing physical activity time given by other clinicopathologic factors.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we examined all-cause mortality in a cohort of 202 HD patients. After an observation period lasting as long as 7 years, 16.8% of the patients had died; cardiovascular disease was the leading cause of death. The main finding of this study is the significant effect of habitual physical activity measured at study entry on mortality in HD patients, independent of age, sex, BMI, time on HD, comorbid conditions, and markers of nutrition and inflammation. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing the correlation between mortality and habitual physical activity evaluated using an accelerometer rather than self-report questionnaires. On the basis of our findings, HD patients spending more time on physical activity on nondialysis days had a lower mortality risk.

Some earlier studies reported the association of physical activity with survival. Tentori et al. reported that mortality risk among HD patients who regularly exercised was 27% lower than that of patients who did not exercise (28). Stack et al. also found that HD patients who exercised 2–3 or 4–5 times per week had an approximately 30% lower mortality than those who exercised 0–1 time per week (12). Furthermore, Beddhu et al. reported that the death rate of inactive patients with CKD was about 40% higher than that of active patients (8). Our findings agree with those of these studies.

Several possible reasons may explain these results. First, physical activity may help reduce mortality in HD patients, partly through improving the prognoses of their comorbid conditions. Multiple lines of evidence from previous observational studies of large-scale populations have suggested that increased physical activity is strongly and inversely associated with mortality from cardiovascular causes (5–7). The main cause of death in the HD population is cardiovascular disease, as found in this study. Previous studies have shown that HD patients engaging in physical activity or participating in low-intensity walking exercise improved their risk factors for cardiovascular disease (hypertension, arterial stiffness, plasma triglyceride and high-density LDL cholesterol levels, dysfunction of the cardiac autonomic system, and reduced maximal oxygen consumption) (21,29–32).

Second, a strong correlation between poor sleep quality and sedentary lifestyle has been previously reported (28,33). Recently, a positive effect of aerobic exercise on sleep quality has been described in HD patients (34). Poor sleep quality has been suggested as contributing to the higher mortality in a large international sample of HD patients (33). Thus, it remains a possibility that the patients with less habitual physical activity in our study might have a sleep problem that subsequently increases the risk for death compared with the patients who exercised more.

Third, maintaining a higher level of physical activity among HD patients might prevent deterioration of physical function and being bedridden. In a previous cohort study, the prognosis of bedridden patients undergoing HD was poor compared with that of patients who were not bedridden (35). Increasing the physical activity of HD patients improves their muscle mass and walking ability (20,36,37). In general, patients with low physical function are at increased risk for falls, and falls tend to predict hospitalization or the need for long-term institutional care (38,39).

On the basis of these reasons, HD patients could greatly benefit from engaging in increased physical activity. At the present time, however, interventions to increase their physical activity are not yet included in routine care.

To maintain good health, the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association have stated that it is necessary for adults to perform moderate-intensity exercise for at least 30 min/d 5 times per week (40,41). However, a previous study showed that 42% of HD patients have severe limitations in moderate physical activities (12). Furthermore, the adverse symptoms related to HD, low physical function, or poor adherence to exercise restrict regular exercise in HD patients (42–46). Besides, a previous study showed that physical activity on dialysis days was significantly less than that on nondialysis days (18). The time constraint caused by the 4-hour HD procedure was cited as the most important reason for decreased physical activity; however, many benefits of exercise during dialysis have been reported recently (47,48). In addition, no studies have reported on adverse events caused by intradialytic exercise. In this sense, it should be taken as one option to encourage HD patients to increase their habitual physical activity on nondialysis days as well as dialysis days. In our study, the average duration of physical activity on a nondialysis day was 43 minutes, which corresponds to approximately 4000 steps. This result was markedly lower than that among healthy controls (16,17) and was similar to that of patients with chronic diseases (49). Thus, our results could be generalized to a wide variety of HD patients. This study also offers room for further investigation to determine the target value for HD patients.

We evaluated the habitual physical activity of HD patients using an accelerometer over 1 week, as indicated by other studies using pedometers. This method for investigation leads to a more reliable and objective assessment (5,50). It may be considered a strength of this study. In addition, we adopted physical activity time as an index of habitual physical activity rather than number of steps or energy expenditure. We used physical activity time because it is a simple index and better suited for the setting goals for habitual physical activity in HD patients. In this case, patients need only their wristwatches.

This study had some limitations. First, because it was an observational study, residual confounders remained possible. Thus, further randomized, controlled studies are needed. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify objectively evaluated physical activity time as a strong predictor of survival. Second, because we evaluated habitual physical activity of HD patients only at baseline, we could not evaluate fluctuation of physical activity over time. However, because we recruited clinically stable and adequately dialyzed patients, their physical activity was assumed not to fluctuate dramatically. Third, we excluded patients who needed assistance with walking. As a result, the comorbid conditions in the participants seemed mild. This should be considered in generalizing our study results to more severely limited patients. Moreover, because the activity monitor does not capture activities such as cycling or swimming, physical activity diaries would help validate the accelerometer data. Finally, although we reported that patients with shorter physical activity time experienced a higher mortality risk compared with the others, the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

In conclusion, engaging in habitual physical activity is associated with decreased mortality risk. Future studies of HD patients are needed to determine the potential mechanisms.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the renal staff for their support and the patients for giving their time to complete the research protocol.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Physical Activity in ESRD: Time to Get Moving” on pages 1927–1929.

References

- 1.Yen TH, Lin JL, Lin-Tan DT, Hsu CW: Association between body mass and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial 14: 400–408, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodkin DA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Koenig KG, Wolfe RA, Akiba T, Andreucci VE, Saito A, Rayner HC, Kurokawa K, Port FK, Held PJ, Young EW: Association of comorbid conditions and mortality in hemodialysis patients in Europe, Japan, and the United States: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3270–3277, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper BA, Penne EL, Bartlett LH, Pollock CA: Protein malnutrition and hypoalbuminemia as predictors of vascular events and mortality in ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 61–66, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamada S, Ishii H, Takahashi H, Aoyama T, Morita Y, Kasuga H, Kimura K, Ito Y, Takahashi R, Toriyama T, Yasuda Y, Hayashi M, Kamiya H, Yuzawa Y, Maruyama S, Matsuo S, Matsubara T, Murohara T: Prognostic value of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction at start of hemodialysis therapy on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in end-stage renal disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1793–1798, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC: Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med 314: 605–613, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leon AS, Myers MJ, Connett J: Leisure time physical activity and the 16-year risks of mortality from coronary heart disease and all-causes in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). Int J Sports Med 18[Suppl 3]: S208–S215, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M: Physical activity and mortality in older men with diagnosed coronary heart disease. Circulation 102: 1358–1363, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beddhu S, Baird BC, Zitterkoph J, Neilson J, Greene T: Physical activity and mortality in chronic kidney disease (NHANES III). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1901–1906, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutner NG, Brogan D, Fielding B: Physical and psychosocial resource variables related to long-term survival in older dialysis patients. Geriatr Nephrol Urol 7: 23–28, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutner NG, Lin LS, Fielding B, Brogan D, Hall WD: Continued survival of older hemodialysis patients: Investigation of psychosocial predictors. Am J Kidney Dis 24: 42–49, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Hare AM, Tawney K, Bacchetti P, Johansen KL: Decreased survival among sedentary patients undergoing dialysis: Results from the dialysis morbidity and mortality study wave 2. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 447–454, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stack AG, Molony DA, Rives T, Tyson J, Murthy BV: Association of physical activity with mortality in the US dialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 690–701, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudor-Locke C, Williams JE, Reis JP, Pluto D: Utility of pedometers for assessing physical activity: convergent validity. Sports Med 32: 795–808, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen KL, Painter P, Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV, Carey S, Da Silva M, Chertow GM: Validation of questionnaires to estimate physical activity and functioning in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 59: 1121–1127, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassett DR, Jr, Cureton AL, Ainsworth BE: Measurement of daily walking distance-questionnaire versus pedometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32: 1018–1023, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng AV, Mulligan K, Carey S, Schoenfeld PY, Kent-Braun JA: Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int 57: 2564–2570, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamojska S, Szklarek M, Niewodniczy M, Nowicki M: Correlates of habitual physical activity in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1323–1327, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majchrzak KM, Pupim LB, Chen K, Martin CJ, Gaffney S, Greene JH, Ikizler TA: Physical activity patterns in chronic hemodialysis patients: Comparison of dialysis and nondialysis days. J Ren Nutr 15: 217–224, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansen KL, Kaysen GA, Young BS, Hung AM, da Silva M, Chertow GM: Longitudinal study of nutritional status, body composition, and physical function in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr 77: 842–846, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutsuna T, Matsunaga A, Matsumoto T, Ishii A, Yamamoto K, Hotta K, Aiba N, Takagi Y, Yoshida A, Takahira N, Masuda T: Physical activity is necessary to prevent deterioration of the walking ability of patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial 14: 193–200, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouidi E, Grekas D, Deligiannis A, Tourkantonis A: Outcomes of long-term exercise training in dialysis patients: comparison of two training programs. Clin Nephrol 61[Suppl 1]: S31–S38, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tawney KW, Tawney PJ, Hladik G, Hogan SL, Falk RJ, Weaver C, Moore DT, Lee MY: The life readiness program: A physical rehabilitation program for patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 581–591, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Huang Z, Gilbertson DT, Foley RN, Collins AJ: An improved comorbidity index for outcome analyses among dialysis patients. Kidney Int 77: 141–151, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider PL, Crouter SE, Lukajic O, Bassett DR, Jr: Accuracy and reliability of 10 pedometers for measuring steps over a 400-m walk. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 1779–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crouter SE, Schneider PL, Karabulut M, Bassett DR, Jr: Validity of 10 electronic pedometers for measuring steps, distance, and energy cost. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 1455–1460, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumahara H, Schutz Y, Ayabe M, Yoshioka M, Yoshitake Y, Shindo M, Ishii K, Tanaka H: The use of uniaxial accelerometry for the assessment of physical-activity-related energy expenditure: A validation study against whole-body indirect calorimetry. Br J Nutr 91: 235–243, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin DB: Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med 127: 757–763, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tentori F, Elder SJ, Thumma J, Pisoni RL, Bommer J, Fissell RB, Fukuhara S, Jadoul M, Keen ML, Saran R, Ramirez SP, Robinson BM: Physical exercise among participants in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): Correlates and associated outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3050–3062, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deligiannis A, Kouidi E, Tourkantonis A: Effects of physical training on heart rate variability in patients on hemodialysis. Am J Cardiol 84: 197–202, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg AP, Geltman EM, Gavin JR, 3rd, Carney RM, Hagberg JM, Delmez JA, Naumovich A, Oldfield MH, Harter HR: Exercise training reduces coronary risk and effectively rehabilitates hemodialysis patients. Nephron 42: 311–316, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustata S, Chan C, Lai V, Miller JA: Impact of an exercise program on arterial stiffness and insulin resistance in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2713–2718, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagberg JM, Goldberg AP, Ehsani AA, Heath GW, Delmez JA, Harter HR: Exercise training improves hypertension in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 3: 209–212, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, Fissell R, Andreucci VE, Fukuhara S, Kurokawa K, Rayner HC, Furniss AL, Port FK, Saran R: Sleep quality predicts quality of life and mortality risk in haemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 998–1004, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afshar R, Emany A, Saremi A, Shavandi N, Sanavi S: Effects of intradialytic aerobic training on sleep quality in hemodialysis patients. Iran J Kidney Dis 5: 119–123, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugaya K, Hokama A, Hayashi E, Naka H, Oda M, Nishijima S, Miyazato M, Hokama S, Ogawa Y: Prognosis of bedridden patients with end-stage renal failure after starting hemodialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol 11: 147–150, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowicki M, Murlikiewicz K, Jagodzińska M: Pedometers as a means to increase spontaneous physical activity in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Nephrol 23: 297–305, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majchrzak KM, Pupim LB, Sundell M, Ikizler TA: Body composition and physical activity in end-stage renal disease. J Ren Nutr 17: 196–204, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattin RW, Lambert Huber DA, DeVito CA, Rodriguez JG, Ros A, Bacchelli S, Stevens JA, Waxweiler RJ: The incidence of fall injury events among the elderly in a defined population. Am J Epidemiol 131: 1028–1037, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tinetti ME, Williams CS: Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 337: 1279–1284, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, Macera CA, Castaneda-Sceppa C, American College of Sports Medicine. American Heart Association : Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 116: 1094–1105, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A, American College of Sports Medicine. American Heart Association : Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 116: 1081–1093, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Padilla J, Krasnoff J, Da Silva M, Hsu CY, Frassetto L, Johansen KL, Painter P: Physical functioning in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol 21: 550–559, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Painter P, Carlson L, Carey S, Paul SM, Myll J: Physical functioning and health-related quality-of-life changes with exercise training in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 482–492, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams A, Stephens R, McKnight T, Dodd S: Factors affecting adherence of end-stage renal disease patients to an exercise programme. Br J Sports Med 25: 90–93, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li M, Li L, Fan X: Patients having haemodialysis: Physical activity and associated factors. J Adv Nurs 66: 1338–1345, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonner A, Wellard S, Caltabiano M: The impact of fatigue on daily activity in people with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Nurs 19: 3006–3015, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheema B, Abas H, Smith B, O’Sullivan A, Chan M, Patwardhan A, Kelly J, Gillin A, Pang G, Lloyd B, Singh MF: Progressive exercise for anabolism in kidney disease (PEAK): A randomized, controlled trial of resistance training during hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1594–1601, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JL, Godfrey S, Ng TT, Moorthi R, Liangos O, Ruthazer R, Jaber BL, Levey AS, Castaneda-Sceppa C: Effect of intra-dialytic, low-intensity strength training on functional capacity in adult haemodialysis patients: A randomized pilot trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1936–1943, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le Masurier GC, Sidman CL, Corbin CB: Accumulating 10,000 steps: Does this meet current physical activity guidelines? Res Q Exerc Sport 74: 389–394, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young EW, Albert JM, Satayathum S, Goodkin DA, Pisoni RL, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Kurokawa K, Bommer J, Piera L, Port FK: Predictors and consequences of altered mineral metabolism: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int 67: 1179–1187, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]