Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to identify characteristics associated with high and low levels of HPV knowledge among women presenting for HPV vaccination.

METHODS

Surveys were administered to women presenting for HPV vaccination at two distinct clinics, a private obstetrics and gynecology office with predominantly privately-insured patients and a resident clinic with primarily Medicaid-insured patients. Nine outcome measures were collected in addition to open-ended response questions regarding motivation for vaccination.

RESULTS

46 women were recruited from the resident clinic and 39 women were recruited from the private clinic. Knowledge scores differed significantly between the two recruitment sites: mean score of 19.7 at the resident clinic compared to a mean score of 24.9 at the private clinic (P<.0001, power= 80%). After controlling for age, zip code poverty prevalence, educational attainment, and parental educational attainment, clinical site was no longer independently associated with knowledge score. Rather, having attended at least one year of college was the only measured item independently associated with a higher HPV knowledge score. Reported condom use, having a regular sexual partner, history of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test, and having received a Pap test within the past year were not independently associated with knowledge score. Themes for motivation to vaccinate include protection from cervical cancer and prevention of HPV infection.

CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge of HPV among women presenting for vaccination was significantly associated with educational attainment of some college. Common themes of low knowledge include the viral etiology of cervical cancer, the clinical presentation of HPV infection and the lack of complete protection against cervical cancer with the HPV vaccine.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, Papillomavirus Vaccines, Uterine Cervical Neoplasms, Condylomata Acuminata, Health Education, Attitude to Health, Public Assistance, Vaginal Smears, Oncogenic Viruses

Introduction

The FDA licensed the quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, Gardasil, on June 8, 2006 for protection against (HPV)-types 6, 11, 16, 18 for females aged nine – 26 years and on September 9, 2009 the vaccine was also approved for males the same age. Gardasil is highly effective in protecting against HPV subtypes 6 and 11, which cause 90% of genital warts and HPV subtypes 16 and 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancer. Subsequently, the CDC recommended routine HPV vaccination for females aged 11–12 years, with catch-up vaccination for females aged 13–26 yearsi. Gardasil is generally considered to be cost-effective although there is some controversy over the economic impact of vaccinating women in “catch-up programs” up to 26 years of age.ii According to the Institute of Medicine, Gardasil is considered a Level II vaccine, meaning the vaccine incurs a small cost (less than US$10,000) for each quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained.iii Each QALY is equivalent to a year in good health, and the value of a year in ill health is discounted. Despite the proven efficacy of the HPV vaccine, multiple obstacles, including cost and social stigma surrounding sexually transmitted diseases, hinder its widespread implementation. From a 2007 survey, The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that only 10% of all eligible women aged 18–26 years and 25.1 % of adolescents aged 13–17 have received at least one dose of the vaccineiv. The CDC does not have data on children aged 9–13. Newer information from 2008 estimates that 35.7% of adolescents have received at least one dose of the vaccine and 17.1% of adolescents have received all three doses but there are no current data on women over the age of 17v.

Studies have quantified HPV knowledge in several very different populations. A small interview-based study (N=40) by RM Mays et al. showed that both adults and adolescents of low socioeconomic background in urban settings lacked considerable knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, and Pap testsvi. Another qualitative study among Hispanic women identified varying amounts of knowledge about cervical cancer and HPV. Most participants understood that cervical cancer is associated with a higher number of sexual partners and that it can be screened for with regular Pap tests. However, most women had little or no knowledge about HPV, its route of transmission or that it causes cervical cancervii. A separate survey-based study of 143 women by Ragin et al.viii examined the general female population’s knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine. This study showed that although most adult women surveyed had heard of HPV (93.6%) and the HPV vaccine (87%), few study participants (18%) were aware that the HPV vaccine protected against cervical cancer and genital warts. A national survey-based study of 1,011 women aged 13–26 showed found that while knowledge varied about the infection itself, women who received the vaccine were more likely to understand that the HPV vaccine protects against cervical cancer (84%) as compared to women who had not been vaccinated (51%).ix College students were more informed and a survey of 177 students found that 97% of them understood that HPV causes cervical cancer.x These studies suggest that there is varied familiarity about HPV and the HPV vaccine across socioeconomic, ethnic, and educational groups but in general, knowledge is lacking.

Although previous research has evaluated HPV knowledge in many populations, no study, to our knowledge, has examined HPV knowledge or motivation for vaccination among women presenting for HPV vaccination. A literature search (MEDLINE; 1950-July 2010; English Language; Search Terms: “attitudes,” “knowledge,” “papillomavirus vaccines”) showed no such study. Elucidating knowledge gaps and their association with specific socioeconomic, ethnic, educational, or health history characteristics among women presenting for HPV vaccination will aid informed decision-making for health care practitioners. Additionally, understanding the reasons why women desire HPV vaccination may also be useful in designing targeted vaccination campaigns to the populations who are found to have the least knowledge about HPV.

Regarding women over 18 years old presenting for HPV vaccination, this study aimed to: a) Validate a knowledge survey assessing the level of knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine and elucidate which areas are the least well understood; b) Compare differences in level of knowledge between patients presenting to two distinct obstetrics and gynecology clinics: privately insured women presenting to a private clinic and publicly insured women presenting to a resident clinic; c) Determine if a patient’s educational attainment, education of parents, having children, residency in a high poverty prevalence zip code, sexual behavior and Pap screening history have an independent association with knowledge; d) Compare open-ended response themes about motivation for HPV vaccination by level of knowledge.

Materials and Methods

This prospective cross-sectional study obtained Institutional Review Board approval from Northwestern University. This study utilized two distinct clinical settings. The private obstetrics and gynecology clinic is affiliated with Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and staffed by private physicians. The private clinic treats primarily insured patients. The resident clinic is staffed by Northwestern University obstetric and gynecology residents and serves predominantly Medicaid-insured patients. Both clinics offer a broad range of outpatient women’s health services, including routine prenatal, postpartum and gynecological care. Most women who received Gardisal vaccination presented for annual exams or another primary complaint, which brought them into to see the gynecologist.

A survey containing knowledge-based questions, demographic information, health screening behaviors, current sexual behaviors, and open-ended questions regarding motivation for vaccination and the definition of HPV was administered from October, 2008 to August 2009 at both the private clinic and the resident clinic. In both clinical settings, a convenience sample of women over age 18 years who presented for HPV vaccination were approached by the clinic staff, invited to participate in the study, and if interested, were given a survey with informed consent. The anonymous survey was a self-administered 5-page, 36 question paper-and-pencil survey. Patients enclosed completed surveys in provided envelopes and returned them to clinic staff. At the time of study participation, patients were already certain of their decision to receive the HPV vaccine; thus it was unlikely that this decision was influenced by administration of the survey. No incentive was used. Each woman paid for the vaccine through Medicaid, private insurance, or from personal funds if it was not covered by her insurance plan.

Exclusion criteria were inability to read and write English or unwillingness to provide informed consent, being under age 18, and previously participating in the study. The inclusion criteria were female sex and presentation to either the private or the resident obstetrics and gynecology clinics for HPV vaccination. Minors were not included in this study given sensitive issues regarding sexual behavior and the study team’s interest in describing HPV vaccination in young adult women, a group more likely to be responsible for their own healthcare decision-making. No upper age limit was established for our study, but no participants were above age 26, which is eldest age for which the vaccine is FDA approved. Lastly, uninsured patients were not seen at either of the two clinic sites and were excluded from the study.

The research team, all of whom have formal training in survey design, developed the survey items and formatting. Due to the small sample size, the survey was not pilot tested. The survey contained four multiple-choice, sixteen true false, and one open-ended knowledge-based question. Knowledge-based questions were developed according to research team expertise and concepts tested in the study by Wetzel, et alxi. The survey had a fourth grade Flesch-Kincaid reading level, which is appropriate for all research participants. The remainder of the survey contained nine patient demographic and characteristic questions, four sexual behavior and screening behavior questions, and one open-ended motivation to vaccinate question. One demographic question asked the participant their five-digit home zip code. Zip codes were then coded into percent of people residing in that zip code living below the federal poverty line as determined by the American Community Survey three-year estimates 2005–2007. The percent of people living below the federal poverty line in a participant’s zipcode was used as a socioeconomic variable.

The research team entered raw data responses into a password-protected Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet. These raw data were then imported into SPSS 17 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A knowledge score was compiled from the four multiple-choice and 16 true-false questions to a total number correct out of 33. Each multiple-choice question had the possibility of more than one correct answer, thus the total score of 33. Scores were based upon number correct out of 33 possible correct answers. Surveys missing more than 50% the knowledge portion responses (N=1) were excluded from analysis of knowledge scores. Frequencies of correct and incorrect answers were tabulated. A Crohnbach’s coefficient alpha analysis of the knowledge scores was conducted to confirm internal reliability and consistency of the score. Statistical difference in mean knowledge score between clinical sites was determined by student’s t-test; alpha was set at <.05. We calculated that a sample size of 28 in each clinic group would have 80% power to detect a difference in means of 3.0 on our 33 item test assuming that the common standard deviation was 4.0 using a two group t-test with a P<.05 two-sided significance level.

Certain survey responses were dichotomized a priori for analysis. Percent of people in a given zip code living below the poverty level was collapsed into two categories: >=20% living below the poverty level and <20% living below the poverty level. Condom use was dichotomized to 1) always using condoms or never had sex and 2) sometimes or never using condoms. Pap test screening history was dichotomized to 1) receiving a Pap test within the past year and 2) no Pap test within the past year.

We performed a multivariate linear regression analysis to determine if HPV knowledge score was associated with the following variables: clinical site, mean age, living in a low poverty prevalence zip code, having attained a year or more of college, having a parent who attained a year or more of college, and having children. A multivariable regression analysis of HPV knowledge scores was performed using the following variables: clinical site, having a self-defined regular sexual partner, always using a condom, having a history of an abnormal Pap test, and having had a Pap test within the past year.

Results

A total of 85 women participated in the study. 77% (46/60) of women who received Gardasil from the resident clinic and 40% (39/103) of women who received Gardasil from the private clinic were enrolled. Demographics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 23 years. 62.3% were receiving their first HPV vaccine shot. 40.0% of participants self-identified as White, 38.8% as African American, and 21.2% as Hispanic or Latino. 30.6% reported a home zip code with more than 20% of residents living below the federal poverty level. 63.5% reported having completed at least some college. All participants presenting to the private clinic (n=36) reported private insurance; 93.5% of participants presenting to the resident clinic reported public insurance. No participants reported being uninsured. Participants recruited from the private clinic differed significantly from those recruited from the resident clinic in terms of age, race, zip code poverty prevalence, personal and parental educational attainment, insurance status, having children, and number. There was no statistically significant difference between clinical sites in terms of reported condom use, a self-defined regular sexual partner, history of abnormal Pap test, and having received a Pap test within the past year. Knowledge scores differed significantly between the two sites: mean score of 24.9 at the private clinic compared to a mean score of 19.7 at the resident clinic (P<.0001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (N=85) Recruited from Private Clinic Compared to Resident Clinic Add overall sample column

| Variable | Total (n=85) | Private (n=39) | Resident (n=46) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 23 (2.16) | 24 (2.0) | 22 (2.3) | 0.02 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n(%) | ||||

| Black | 33 (38.8) | 6 (15.4) | 27 (58.7) | <.0001 |

| Hispanic | 18 (21.2) | 1 (2.6) | 17 (37.0) | |

| White, non-Hispanic, and other | 34 (40.0) | 32 (82.1) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Zip Code Poverty Prevalence, n(%) | ||||

| <20% | 59 (69.4) | 35 (89.7) | 24 (52.2) | <.0001 |

| >=20% | 26 (30.6) | 4 (10.3) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Educational Attainment, n(%) | ||||

| 1 or more years of college | 68 (80.0) | 39 (100) | 29 (63.0) | <.0001 |

| No college | 17 (20.0) | 0 | 17 (37.0) | |

| Parental Educational Attainment, n(%) | ||||

| 1 or more years of college | 54 (63.5) | 34 (87.2) | 20 (43.5) | <.0001 |

| No college | 31 (36.5) | 5 (12.8) | 26 (56.5) | |

| Insurance type, n(%) | ||||

| Private insurance | 42 (49.4) | 39 (100) | 3 (6.5) | <.0001 |

| Medicaid or public insurance | 43 (50.5) | 0 | 43 (93.5) | |

| Do you have children? n(%) | ||||

| Yes | 41 (48.2) | 0 | 41 (89.1) | <.0001 |

| No | 44 (51.8) | 39 (100) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Today you received: n(%) | ||||

| First HPV vaccine shot | 53 (62.4) | 13 (33.3) | 40 (87.0) | <.0001 |

| Second or third shot | 32 (37.6) | 26 (66.7) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Sexual and Screening Behaviors | ||||

| Condom Use, n(%) | ||||

| Always using condoms or never had intercourse | 18 (21.2) | 11 (28.2) | 7 (15.2) | 0.14 |

| Sometimes or never use condoms | 67 (78.8) | 28 (71.8) | 39 (84.8) | |

| Have a regular sexual partnera n(%) | ||||

| Yes | 72 (85.7) | 30 (76.9) | 42 (91.3) | 0.15 |

| No | 12 (14.3) | 8 (20.5) | 4 (8.7) | |

| History of Abnormal Pap Smeara n(%) | ||||

| Yes | 30 (35.7) | 14 (35.9) | 16 (34.8) | 0.65 |

| No | 54 (64.3) | 25 (64.1) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Had a Pap Smear within past year n(%) | 52 (61.2) | 36 (92.3) | 36 (78.3) | 0.07 |

| Knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, and the vaccineb mean (SD) | 22.1 (3.88) | 24.9 (3.6) | 19.7 (4.1) | <.0001 |

One participant did not respond

Knowledge score is number of answers correct out of 33 answers.

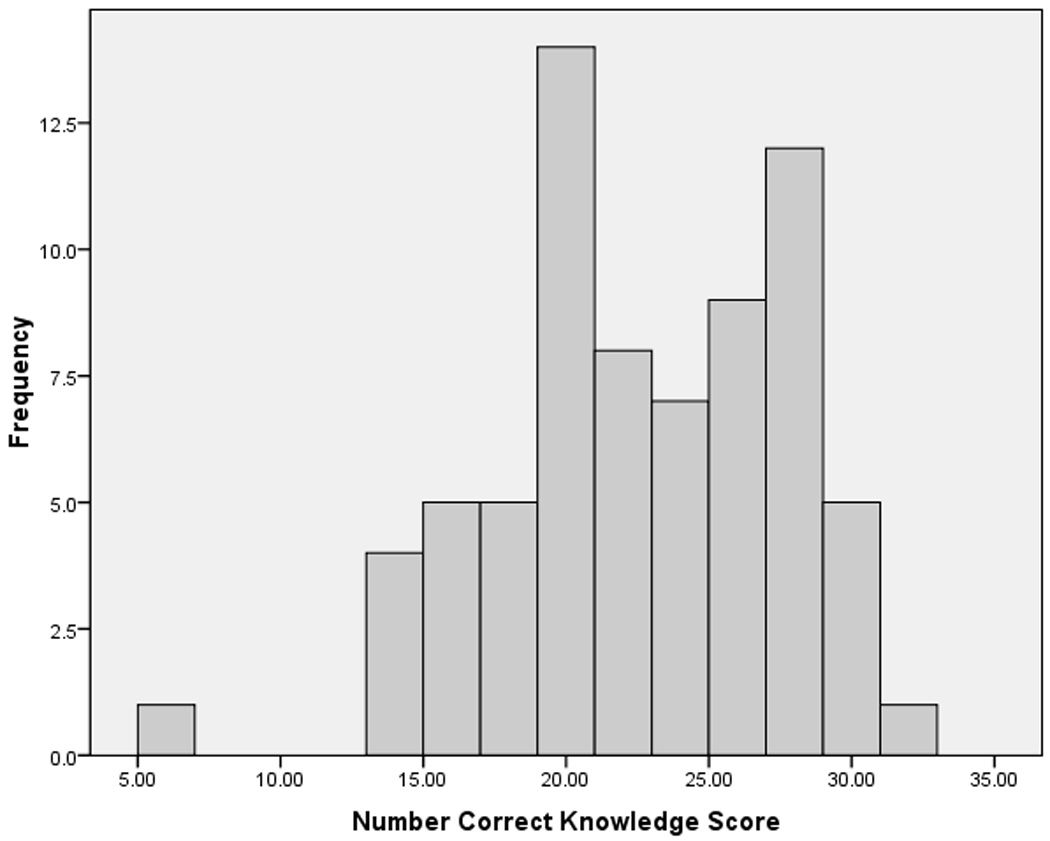

The mean knowledge score for all participants was 22.1 with a standard deviation of 4.6. The distribution of these scores is demonstrated in Figure 1. Knowledge scores followed a normal distribution. The knowledge scale had a Crohnbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.77. No knowledge questions were excluded in the tabulation of the final score. The five knowledge items most commonly answered incorrectly are displayed in Table 2. Regression analysis of HPV knowledge scores by responder characteristics, as summarized in Table 3, demonstrated the only measured item independently associated with knowledge score to a level of statistical significance was having attended at least some college (P<.001). Participants who had attended at least one year of college had a mean knowledge score of 23.5 compared to those who had not attended any college with a knowledge score of 16.5 (P<.0001). After controlling for personal educational attainment only parental educational attainment became statistically significant. Clinical site, age, poverty prevalence, and having children were not significantly associated with knowledge score. An important trend was noted among poverty prevalence and knowledge scores: No women who scored in the top quartile of knowledge scores resided in a zip code with greater than 20% of the population living below the poverty line. The women who scored in the lowest quartile of knowledge scores resided in a mixture of poverty prevalence zip codes. Regression analysis of HPV knowledge scores by history of abnormal Pap test, reporting consistent use of condoms, regular sexual partner, and having had a Pap test within the past year demonstrated that none of these variables were independently associated with knowledge score.

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Commonly Missed Survey Items

| Knowledge Item [correct answer] | N (%) Incorrect |

|---|---|

| Most women have abnormal menstrual periods when infected with HPV. [False] | 54 (63.5) |

| Completing the HPV vaccine series completely prevents HPV infection. [False] | 58 (68.2) |

| The HPV vaccine protects you from getting most genital warts. [True] | 63 (74.1) |

| The HPV vaccine prevents you from getting most types of HPV. [False] | 65 (76.5) |

| HPV infection can make it difficult to become pregnant. [False] | 77 (90.6) |

Table 3.

Regression Analysis of HPV Knowledge Scoresa (N=85)

| Variable | B value | Std. Error | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical site | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.29 |

| Age | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.36 |

| Attained at least 1 Year of College | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Parents Attained at least 1 Year of College | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.32 |

| Having No Children | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.45 |

R2=.44. Variables associated with knowledge score at P<.05 are shown in bold.

Discussion

This study assessed knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine among adult women presenting for HPV vaccination. We found that HPV knowledge was highly determined by educational attainment, while surprisingly uninfluenced by age, Pap test screening practices, history of an abnormal pap test, and sexual behaviors. Though zip code poverty-prevalence was not independently associated with HPV knowledge, all of the women with the highest quartile of knowledge scores came from zip code areas with the high incomes. This indicates that while women with low knowledge may reside in zip codes with either high or low incomes, women with high knowledge do not reside in low income zip code areas. This finding indicates the need for more intensive HPV education directed towards women with low educational achievement and from high poverty-prevalence areas.

Several knowledge gaps among women presenting for HPV vaccination were demonstrated in this study. The clinical presentation of HPV infection appears to be poorly understood considering a majority of respondents believed that most women have abnormal menstrual periods and a difficult time conceiving when infected with HPV. A majority of respondents also mistakenly believed that the HPV vaccine would completely protect them against all HPV infection. The possibility that these women will believe they are fully protected after vaccination and thus stop their regular pap test screening practices is a significant concern. Another significant knowledge deficit demonstrated by our study was that most women did not know that the HPV vaccine is highly efficacious in protecting against genital warts. Future education campaigns should emphasize that most women infected with HPV are asymptomatic, that the HPV vaccine only protects against 70% of the HPV infections that cause cervical cancer, and that vaccination also protects against genital warts.

Our study demonstrated that having a history of an abnormal Pap test, having had a Pap test within the past year, always using a condom, and having a regular sexual partner had no independent association with HPV knowledge. In one study of 69,147 women randomly sampled from the general population of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland, having heard of HPV was only weakly correlated with condom use, but more strongly associated with a history of genital warts and educational level.xii Our results were consistent with their finding of association with education level, yet inconsistent with their finding of association with condom use. History of an abnormal Pap test has not been well-examined in the literature as an influence on HPV knowledge. Our findings suggest that certain screening behaviors and sexual practices do not predict greater knowledge about HPV.

Our study had several limitations. As we examined women who were presenting for the HPV vaccine, we are unable to generalize our results to the population of adult women who have chosen not to obtain the vaccine or have not yet committed to vaccination. Also, our number of responses has been limited by the small number of adult women presenting for the vaccine at our clinical sites, requiring that the study continue to collect data for an extended period of time. As a result, we are unable to account for any acquired knowledge between women enrolled early in our study period compared to those recruited at the end of our study period. Importantly, our study excluded minors, a group who makes up most of those presenting for HPV vaccination. We chose to study adult women because we believe they are more likely to act as their own health advocates and to be less influenced by the input of parents and guardians. As a result of this choice, our results cannot be generalized to minors presenting for the HPV vaccine. Furthermore, our results likely reflect the fact that during routine office visits when the health care staff recommends HPV vaccination and during recruitment for the study, participants were briefly informed of the existence of HPV, its route of transmission, consequences of infection and purpose of the vaccine. Lastly, differing literacy levels among participants could have resulted in measurement bias. Women with lower literacy may have had difficulty understanding the survey, leading to lower knowledge scores. It is unknown if these scores then truly reflect their knowledge or are a reflection of the survey design.

Despite these limitations, we believe this study has essential implications for health care delivery and future research. This study lends important information that can be used to tailor educational campaigns and to more effectively implement the HPV vaccine. The specific knowledge gaps described above are areas of needed intervention. The fact that many misguided beliefs about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine remain within a population who has decided to be vaccinated is of serious concern. Currently, the pharmaceutical companies that produce the vaccines perform the majority of vaccination campaigning. Although these companies have a financial incentive to vaccinate as many women as possible, they are not necessarily motivated to educate women. Marketing campaigns have emphasized the efficacy of the HPV vaccine in decreasing the risk of cervical cancer, while downplaying the sexual transmission of HPV.xiii As a result, it is possible that the public is gaining a skewed knowledge of HPV. Future campaigns aimed at increasing knowledge in the gaps noted above would best be performed by public health agencies and organizations in a non-biased fashion, with the goal of increasing patient self-efficacy to pursue vaccination. Clinicians should take responsibility for educating their patients as well. This outreach should teach women that the disease is most commonly asymptomatic. In addition, it should focus on the scope and limits of the Gardasil vaccine, including prevention of genital warts. Special attention should be given to patients who have not attended college, as their knowledge of HPV is likely to be lower.

Further exploration of the implications of knowledge about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine among adult women presenting for vaccination is needed. Our finding that knowledge is not independently associated with poverty, ethnicity, or age contradicts the findings of several previous studies in different populations and should be examined more extensively. In addition, HPV knowledge among adolescents presenting for vaccination should be an area of future research. The impact of a health education intervention targeting the knowledge gaps demonstrated above should be investigated. Lastly, effective educational interventions targeting women who have never attended college or who live in poverty-prevalent areas should be developed and rigorously evaluated.

Acknowledgements

While carrying out this research, Melissa Simon was supported by NIH NICHD K12 WRHR HD050121-04 (PI: ELIAS). We greatly appreciate the participation of the women in our study. We also greatly appreciate the clinic staff for the support of this study during the data collection period.

Biographies

Sara Kennedy, MD MPH, is an obstetrician and gynecologist. She is currently a clinical fellow in Family Planning at the University of California, San Francisco.

Rebekah Osgood, MD, MPH is in her second year of residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University's Prentice Women's Hospital. She obtained her BA from UC Berkeley in Molecular and Cell Biology, and then went on to obtain her MD and MPH from Northwestern University.

Laura Rosenbloom, BS is currently pursing her MD at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. She obtained her BA from Georgetown University in International Health.

Joe Feinglass, Ph.D. is a Research Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine and the Institute for Healthcare Studies at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Dr. Feinglass is a health services researcher with a degree in Public Policy Analysis.

Melissa A. Simon, MD MPH is an Assistant Professor of the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Preventive Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist among the authors.

References

- i.Markowitz L, Dunne E, Saraiya M, Lawson H, Chesson H, Unger E. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR. 2007;5:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ii.Goldie S, Kim J. Health and economic implications of HPV vaccination in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:821–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- iii.Institute of Medicine. Vaccines for the 21st century: a tool for decision-making. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- iv.Centers for Disease Control. Vaccination coverage among U.S. adults. Atlanta, GA: National immunization survey; 2007. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/downloads/nis-adult-summer-2007.txt. [Google Scholar]

- v.Centers for Disease Control. Vaccination coverage among U.S. Teens/Adolescents. Atlanta, GA: National immunization survey; 2008. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nisteen/data/tables_2008.htm. [Google Scholar]

- vi.Mays R, Zimet G, Winston Y, Kee R, Dickes J, Su L. Human papillomavirus, genital warts, Pap smears, and cervical cancer: knowledge and beliefs of adolescent and adult women. Health Care for Women International. 2000;21:361–374. doi: 10.1080/07399330050082218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vii.Vanslyke J, Baum J, Plaza V, Otero M, Wheeler C, Helitzer D. HPV and cervical cancer testing and prevention: Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes among Hispanic women. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:584–596. doi: 10.1177/1049732308315734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.Ragin C, et al. Knowledge of the human papillomavirus and the HPV vaccine- a survey of the general population. Infect Agent Cancer. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-4-S1-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ix.Caskey R, et al. Knowledge and early adoption of the HPV vaccine among girls and young women: Results of a national survey. J Adolescent Health. 2009;45:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- x.Licht J, Murphy A, Hyland B, Fix L, Hawk M. Is use of the human papillomavirus vaccine among female college students related to human papillomavirus knowledge and risk perception? Sex Trans Infect. 2010;86:74–78. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xi.Wetzel C, Tissot A, Kollar LM, Hillard P, Stone R, Kahn J. Development of an HPV educational protocol for adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.Nohr B, et al. Awareness of human papillomavirus in a cohort of nearly 70,000 women from four Nordic countries. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2008;87:1048–1054. doi: 10.1080/00016340802326373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Rothman J, Rothman S. Marketing HPV vaccine: implications for adolescent health and medical professionalism. JAMA. 2009;302:781–786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]