Abstract

Objectives

Questionable occlusal caries (QOC) can be defined as clinically-suspected caries with no cavitation or radiographic evidence of occlusal caries. To our knowledge, its prevalence has not been quantified; this was the objective of this study.

Methods

A total of 82 dentist and hygienist practitioner-investigators from “The Dental Practice-Based Research Network” (DPBRN) participated. When patients presented with at least one unrestored occlusal surface, their number of unrestored occlusal surfaces and QOC were quantified. Information also was recorded about patient characteristics on consented patients who had QOC. Data analysis adjusted for patient clustering within practices.

Results

Overall, 6,910 patients had at least one unrestored occlusal surface, with a total of 50,445 unrestored surfaces. Thirty-four percent of all patients and 11% of unrestored surfaces among all patients had QOC. Patient- and surface-level QOC prevalence varied significantly by region (p<0.001; p<0.03). The highest percent for patient-and surface-level prevalence was in Florida/Georgia (42%; 16%).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the prevalence of QOC in routine clinical practice. These results document a high prevalence overall, with wide variation in prevalence among DPBRN’s five main regions.

Clinical Implications

QOC lesions are common in routine practice and warrant further investigation regarding how best to manage them.

Keywords: practice-based research, questionable lesions, multi-center studies, clinical research, dental caries

Introduction

Despite considerable improvements in oral health1, dental caries remains a significant health problem.2 The prevalence and severity of the disease are higher among individuals of low socioeconomic status and ethnic/racial minorities.3 With the advent of fluoride4–7 the incidence of caries in the overall population has lessened in recent years. The effects of fluoride, though, have led to difficulty in detecting caries on the occlusal surface because fluoride can result in an intact surface with sub-surface demineralization.7–8 There are essentially two types of such lesions. In “hidden caries”, demineralization has progressed to the point where it is detectable radiographically under a seemingly unaffected surface.

In “questionable caries”, which is the focus of this study, the tooth has no cavitation (no continuity break in the enamel) and no radiographic evidence of caries, but the presence of caries is suspected due to roughness, surface opacities, or staining. If the surface is intact and there is no radiographic sign of demineralization, the presence of any lesion will be difficult to detect.9–13

Questionable lesions present practitioners with a difficult diagnostic decision.7,13–15 To date, there have been very few studies regarding the characteristics of these lesions, 8,10,12,16 only one examining their progression,17 and no studies describing their prevalence. As a result there is no firm consensus on their management. The scant evidence available suggests that non-surgical management is the appropriate approach. The relatively slow progression of occlusal caries lesions in general,10,18,19 coupled with the possibility of their arrest or reversal,20 and the success of sealants in stopping progression of frank dentinal caries, all argue for a conservative approach.21

Given the weak evidence that supports this recommendation about clinical management, it is clear that more needs to be known about the epidemiology of questionable occlusal lesions. As a first step, this study examines their prevalence in patients attending dental practices affiliated with The Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN).

The DPBRN is a consortium of dental practices whose purpose is to answer questions raised by dental practitioners in everyday clinical practice and to evaluate the effectiveness of current strategies to prevent, manage, and treat oral diseases and conditions.22–23 TheDPBRN includes dental practitioners (dentists and hygienists) from the United States and Scandinavia; it is currently divided into five main regions: Alabama/Mississippi (AL/MS); Florida/Georgia (FL/GA); private practitioners in Minnesota and dentists who participate in HealthPartners (MN); Kaiser Permanente and Permanente Dental Associates in Washington and Oregon (PDA); and the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (DK; only the country of Denmark participated in this particular DPBRN study). The DPBRN represents a diverse group of both dentists and hygienists with regard to practice types (solo and small group practice, large group practice, public health practice), treatment philosophies, race, ethnicity, workload, age, and gender. PDA is a dentist-owned Professional Corporation that contracts exclusively with Kaiser Foundation Health Plan to provide dentist professional services and jointly manage the Kaiser Permanente Dental Care Program in Washington and Oregon. The practice model is a closed panel large group practice. Traditionally this arrangement might be called an HMO; however, now individual plans and competing insurance products make it more of a blend between a PPO and HMO. Dentists are compensated with a base salary and incentive based pay. In Denmark, dentists get paid on a fee-for-service in private practice. On average, 82% of the costs are paid by the patient and just 18% are covered by the government. However, many adult patients have private insurance which cover part of the patient payment. All dental care is free until the age of 18.

Although DPBRN dentists have substantial diversity, previous analyses have documented that DPBRN dentists have much in common with dentists at large.23 To date, there are more than 1,000 practitioner-investigators enrolled in the network, including 68 hygienists. Specifics regarding DPBRN practitioners have been previously reported.23

The purpose of this study (DPBRN study “Prevalence of questionable occlusal caries lesions”) was to quantify the prevalence of questionable occlusal caries lesions (QOC) and its regional variation, at both the patient-level and surface-level.

Material and Methods

Selection and recruitment process

To become a member of DPBRN, practitioners must first complete a DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire. This questionnaire, which is publicly available at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/DPBRN%20Enrollment%20Questionnaire.pdf, collects information about practitioner, practice, and patient characteristics. DPBRN practitioners were recruited by DPBRN Regional Coordinators through continuing dental education courses sponsored by DPBRN, as well as letters sent to licensed practitioners from the participating regions. To be eligible for this DPBRN study (“Prevalence of Questionable Occlusal Caries Lesions”), practitioners had to complete both the DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire and a questionnaire regarding how they diagnose and treat dental caries (“Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Caries Treatment” questionnaire, also available at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Study%201%20questionnaire%20011906.pdf), attend a DPBRN orientation session or watch a video of it, and complete their training in human subjects protection. The response rate varied by region. For the AL/MS, FL/GA, and DK regions, the response rate was 100%. Thirteen of 20 practitioner-investigators in the MN region and 15 of 30 in the PDA region who expressed interest in the study enrolled. All DK hygienists work under the responsibility of a dentist, but practice independently. The dentist does not control or check all decisions and treatments made by the hygienist

An objective of DPBRN is to investigate dental care as it occurs in routine clinical practice, employing diagnostic and treatment methods as they are used in actual community-based, non-academic clinical practice settings, where almost all of the population receives its dental care. Therefore, although DPBRN makes a point of standardizing the data collection process, it seldom does studies that require standardization or calibration of diagnostic and treatment methods across practices. Consequently, calibration and inter-examiner reliability training was intentionally not conducted for this study.

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional study conducted by DPBRN dentists and hygienists (practitioner-investigators) in their offices. An objective of the study was to determine how commonly these practices faced the diagnostic challenge, QOC, given the diagnostic methods that they normally use in routine practice. Each office maintained a consecutive patient log on approximately 100 patients who presented with at least one unrestored (no sealant or restoration) occlusal surface on a permanent posterior tooth (which includes first and second premolars and first, second, and third molars). Practitioner-investigators were instructed to log patients who presented with at least one unrestored occlusal surface. Based on practices that logged everyone, about 10% of patients had no eligible surfaces. Office personnel recorded the number of unrestored occlusal surfaces and the number, if any, of QOCs on the occlusal surface. Buccal and lingual grooves were not included in this study. Data were collected between September 2008 and December 2010. On average, practices surveyed patients for 2.4 (sd=1.4) months and surveyed on average 55 (sd=39) patients per month.

The definition of a QOC is a tooth with no cavitation (no continuity break in the enamel) and no radiographic evidence of caries, but the presence of caries is suspected due to roughness, surface opacities, or staining. The respective institutional review boards (IRB) in each region approved the study. Any patient with a permanent posterior tooth was eligible. Therefore, the patients were age 6 or older. IRBs approved requiring no informed consent because patient identifiers were not recorded. The patient log can be found at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/2Final_Patient_Log_Study_12_Makhija_Regions_verbal_consent_052309.pdf.

Practitioner-level Variables

Practitioner-level variables for the 82 practitioners who participated in this study were collected from the DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire. In addition to DPBRN region, this form also included questions related to their type of practice, gender, race/ethnicity, and year of graduation.

Statistical Methods

Analyses were conducted at both the patient and surface [tooth] levels; namely, the percent of patients who had at least one QOC, and the percent of unrestored occlusal surfaces that had a QOC. To describe variation by practices within and across regions we calculated the distribution (specifically, the median and interquartile [IQR] range) within each practice by region for the following: 1) number of patients examined, 2) percent of patients who had at least one QOC, 3) number of unrestored occlusal surfaces per patient, and 4) percent of unrestored occlusal surfaces with a QOC per patient. The latter two were calculated at the patient level, then averaged across practices.

Bivariate and adjusted analyses were performed to determine if any significant differences were found between practitioner characteristics (gender, race, year graduated, whether or not pediatric practice) and number of patients, unrestored surfaces and prevalence of QOC at patient and surface level. Adjustment for patient clustering within practices was done using generalized linear models. The corresponding analysis of variance was used to assess statistical significance of differences observed across regions. The statistical tests for differences across regions were weighted by number patients per practice as was calculation of a 95% confidence interval for overall prevalence. One region (DK) had a sufficient number of pediatric practices to compare differences between pediatric practices and general dentistry practices, so we assessed the statistical differences in prevalence based on practice type for this region. We also assessed whether the number of patients examined was associated with prevalence of QOC using Spearman rank correlations and adjusted using linear models. Prevalence was also assessed separately for 26 (32%) practices that surveyed all patients, not just eligible; this percent did not differ by region.

Results

Prevalence of QOC

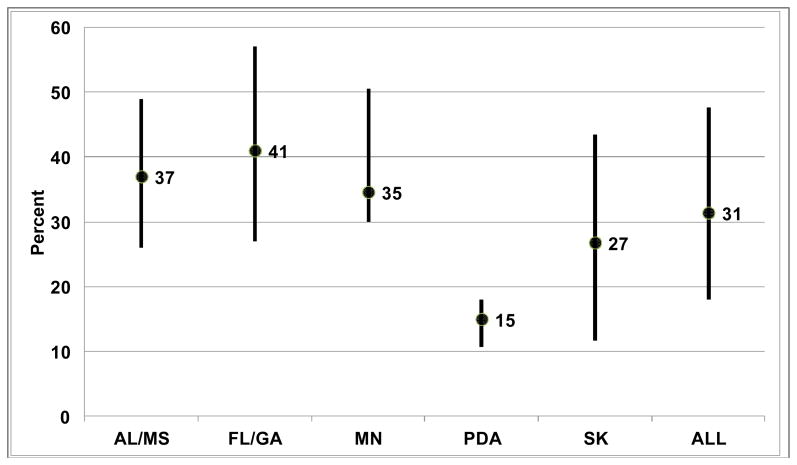

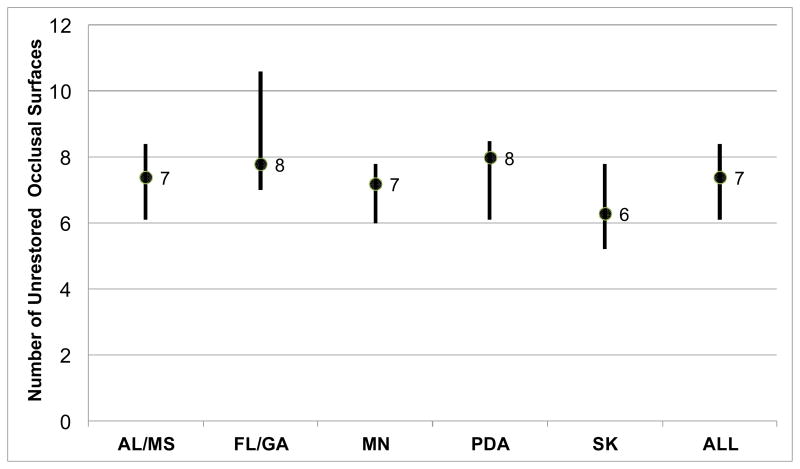

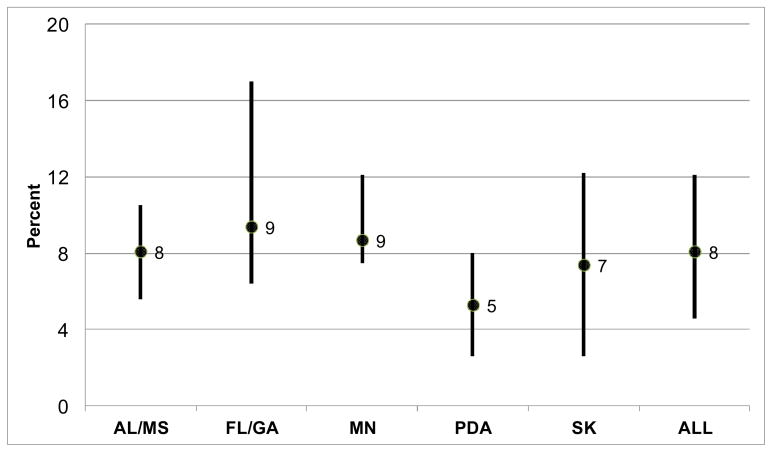

Of 6,910 patients examined who had at least one unrestored occlusal surface, 2,312 presented with at least one QOC, for an overall patient-level prevalence of 33.5% (95% CI: 29.3–37.6%). This prevalence differed across region (P<0.001), and was notably lower in the KP/PDA region (16%) compared to the other regions (31–42%) [Table 1]. The total number of unrestored occlusal surfaces among the examined patients was 50,445, of which 4,809 had a QOC. The mean number of unrestored occlusal surfaces per patient was 7.4 (95% CI: 7.2–7.5). The percent of unrestored occlusal surfaces with a QOC, per patient, was 11% (95% CI: 10.4–11.8%), differing across regions (p=0.03). Again, the lowest regional prevalence observed, 5.5%, was in the KP/PDA region [Table 1]. Among the 26 practices that surveyed all not just eligible patients, the prevalence was 30% (636/2,102).

Table 1.

Prevalence of questionable occlusal lesions (QOC), at patient level and tooth level, by region and overall*

| Region

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL/MS | FL/GA | MN | PDA | DK | Total | |

|

| ||||||

| Patient level | ||||||

| Total number of patients | 890 | 1,526 | 988 | 1,074 | 2,432 | 6,910 |

| Total number of patients with a QOC | 368 | 641 | 379 | 169 | 755 | 2,312 |

| Percentage of patients with a QOC | 41.3 | 42.0 | 38.4 | 15.7 | 31.0 | 33.5 |

|

| ||||||

|

P<0.001

| ||||||

| Tooth (occlusal surface) level | ||||||

| Total number of unrestored occlusal surfaces | 6,910 | 11,105 | 7,435 | 6,934 | 18,061 | 50,445 |

| Total number of above surfaces with QOC | 688 | 1,376 | 689 | 350 | 1,706 | 4,809 |

| Mean number of unrestored occlusal surfaces per patient* | 7.9 | 7.1 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 7.4 |

|

| ||||||

| P=0.14

| ||||||

| Percentage of unrestored surfaces with QOC | 9.9 | 12.4 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 9.4 | 9.5 |

| Mean percentage of unrestored surfaces with a QOC per patient* | 14.8 | 15.7 | 13.4 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 11.1 |

|

| ||||||

| P=0.03 | ||||||

Calculated at patient level. Adjustment for patient clustering within practices was done using generalized linear models.

P-values are for differences across region.

AL/MS: Alabama/Mississippi

FL/GA: Florida/Georgia

MN: Minnesota

PDA: Permanente Dental Associates (Washington and Oregon)

DK: Scandinavia (Denmark)

Neither the number of patients, number unrestored surfaces per patient, prevalence of QOC at patient level or surface leveled differed in bivariate analyses by practitioner gender, race, year graduated or whether or not the practice was pediatric. In adjusted analyses, including all these characteristics as well as region, the only significant difference was gender of practitioner and percent of teeth with a QOC lesion/per patient. Female practitioners had a higher percent (15%) compared to their male counterpart (10%; p=0.04).

There was no correlation between number of patients examined and prevalence of QOC. Within Denmark, pediatric practices had a lower prevalence of QOC than general practices (21.6% vs. 35.4%, p=0.08), although the difference was not statistically significant.

Practitioner characteristics

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the practitioner-investigators who participated in this study, by region. The largest group of practitioners was from the DK region (25/82; 31%) and the smallest from the AL/MS region (10/82; 12%). Overall, there were 14 dental pediatric practitioners, and 68 general practitioners. Of the 82 practitioners, 12 (15%) were hygienists from DK (all hygienists who participated in this study were from DK). With regard to gender, a majority of the practitioners were male in all regions, with the exception of the DK region, which was made up of 76% female practitioners (19/25). Race and ethnicity were combined into two responses of Non-Hispanic White (NHW): Yes” or “No”. Overall, 84% (68/82) of the practitioners were NHW, with all practitioners in the MN and DK regions in this category. When asked about the year of graduation from school, 40% (33/82) responded they graduated between 1981–1995. The PDA region had the largest percent of those who graduated after 1995 (9/15; 60%) and the smallest percent in the FL/GA region (2/19; 11%).

Table 2.

Practitioner characteristics (%), by region

| Region

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AL/MS n=10 |

FL/GA n=19 |

MN n=13 |

PDA n=15 |

DK n=25 |

Total n=82 |

|

| ||||||

| Type of practice | ||||||

| General Practice | 7 (70) | 18 (95) | 13 (100) | 14 (93) | 16 (64) | 68 (83) |

| Pediatric Dentistry | 3 (30) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 9 (46) | 14 (17) |

|

| ||||||

| Gender of practitioner | ||||||

| Male | 8 (80) | 15 (79) | 8 (62) | 10 (67) | 6 (24) | 47 (57) |

| Female | 2 (20) | 4 (21) | 5 (38) | 5 (33) | 19 (76) | 35 (43) |

|

| ||||||

| Race/ethnicity of practitioner | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White-Yes | 8 (80) | 15 (79) | 13 (100) | 8 (53) | 25 (100) | 69 (84) |

| Non-Hispanic White-No | 2 (20) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 7 (47) | 0 (0) | 13 (16) |

|

| ||||||

| Practitioner’s year of graduation | ||||||

| 1980 or before | 4 (40) | 8 (42) | 5 (39) | 1 (7) | 7 (28) | 25 (30) |

| 1981–1995 | 6 (60) | 8(42) | 6 (46) | 5 (33) | 8 (32) | 33 (40) |

| After 1995 | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 2 (15) | 9 (60) | 10 (40) | 22 (27) |

| missing | - | 1 (5) | - | - | - | 1(3) |

Discussion

These results suggest that the prevalence of QOC is substantial and that there are significant regional variations. Prevalence at the patient level ranges from 16%–42% among the 5 regions, with an overall prevalence of 34%. As the practices surveyed on average 55 patients per month who had an unrestored occusal surface, this would translate to seeing 19 QOCs per month. At the surface level it ranges from 6%–16%, with an overall prevalence of 11%. This high overall patient- and surface-level prevalence suggests that practitioners encounter QOC very commonly during their routine clinical practice.

Dental care has slowly evolved from a time of restoring all caries, regardless of size, to “early detection and management”.21 Past literature has not investigated the prevalence of QOCs, so the evidence from this study should be important in informing future studies. Future studies and analyses should describe characteristics of these lesions, including the patient’s caries risk as assessed by the clinician, how the QOC were diagnosed and treated, as well as their long-term outcomes. If more information can be gathered about these patients, their treatment, and their treatment outcomes, better guidelines can be developed to manage these lesions properly in a non-invasive manner. Hamilton et al.17 studied questionable occlusal lesions over a two-year observation period, with one-half of the originally identified questionable lesions followed with no intervention except when the lesion was deemed to have progressed to a definitive caries lesion with dentinal involvement. At the end of this two-year observation period, only 16% of these lesions progressed into the dentin, showing that conservation of tooth structure is possible. To determine if caries penetrated into the dentin, a bitewing radiograph was taken. Once the caries was removed, an impression of the occlusal surface was taken (which was weighed) to measure the amount of lost tooth structure. Knowing how often these lesions occur and how they are diagnosed and treated can lead to improvement of the practitioners’ ability to appropriately manage them. Our results indicate QOCs are common in everyday practice. Therefore, their proper treatment would have significant public health impact. Nonsurgical measures such as sealants or other nonsurgical treatment could be more impactful than early surgical treatment, if effective, consistent with findings from previous studies. 8,9,17

There were some limitations with this study. This study investigated diagnosis and treatment as delivered in routine, “real world” clinical practice and therefore made no attempt to standardize or calibrate that diagnosis or treatment. An objective of DPBRN is to observe daily clinical practice, using diagnostic methods that are used in actual clinical practice where almost all of the population receives its dental care. Therefore, it is possible there are differences in diagnosis of these lesions between practices. Also, by its nature, PBRN research requires that patients choose to enter the dental care system. Persons who make that choice may have a different prevalence compared to those who do choose not to enter the dental care system.

Practitioners were chosen from each of DPBRN’s five main regions and recent literature suggests that although DPBRN dentists have substantial diversity, they have much in common with dentists at large.23 The time to complete this study varied among the practices, which could affect the sample population. However, this patient sample is representative of the practices in the network based on previous DPBRN studies.24–25 Each practice was trained specifically for this study so as to standardize the data collection process, but no effort was made to standardize diagnostic or treatment methods for QOC – indeed, such standardization would not be desirable because an objective of the study was to determine how commonly these practices faced this diagnostic challenge given the diagnostic methods that they normally use in routine practice. One of the criteria for participating in this study was to complete an “Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Caries Treatment” questionnaire which included photographs of scenarios and how the practitioner-investigator would intervene. A future plan is to produce a manuscript that has analyzed the results of this questionnaire and the results of this study.

It is interesting to note that both the AL/MS and FL/GA regions, in which the solo practice or small group practice (SGP) of 3 or fewer dentists predominates, had similar patient- and surface-level prevalence of QOC. However, in the MN and PDA regions, which largely comprised dentists in a large group practice (LGP) of 4 or more dentists, their prevalence varied greatly (of the thirteen practitioners who participated in the MN regions, two practiced in community clinics, three were in private practice, and eight were from HealthPartners). This difference may be related to graduation year, which could affect the diagnosis of QOC, since past literature has shown that dentists in PDA graduated at a later date compared to other regions.26–28 Another explanation could be the fact that Minneapolis (MN), and some of Oregon, (PDA) has fluoridated water, which may impact the number of questionable lesions found in the area.30 The DK regional patient- and surface-level prevalence was similar to the overall prevalence and consisted of a mix of all types of practices (SGP, LGP, and Public Health Practice) as well as both dentists and hygienists. In Denmark, it was found that pediatric practices had a lower prevalence of QOC than general practices. In addition to the age differences in patient populations between these practices, the lower prevalence could be due to the fact that patients receive free dental care until the age of 18 and many of the posterior surfaces have sealants31 and are therefore not eligible to have a QOC. In addition, Danish pediatric practices only treat patients up to the age of 18 in contrast to general practitioners. The age difference in the patient populations could also explain the differences in results.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the prevalence of QOC in routine clinical practice. The results suggest wide variance in prevalence in DPBRN’s five regions, both at the patient- and surface-level. The high frequency at which these lesions are identified poses a diagnostic challenge to the practitioner and has important implications for treatment decisions and the potential for overtreatment. Strong evidence regarding the progression of QOC is necessary to help guide clinical decision making for this type of lesions.

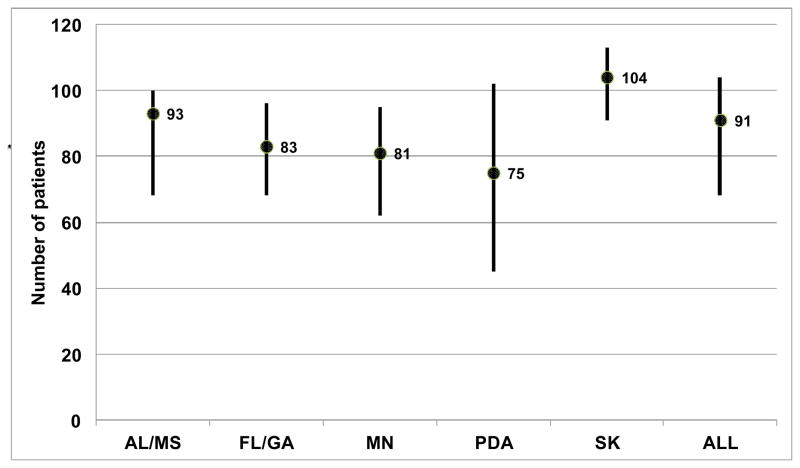

Figure 1. Distribution* of number of eligible patients examined per practice, by region.

*Median and inter-quartile ranges

Figure 2. Distribution* of percentage of patients† examined with a questionable occlusal caries (QOC) lesion, by region.

*Median and inter-quartile ranges; P<0.001 differences across regions, adjusted for clustering within practices, weighted by number of patients surveyed at the practice.

Figure 3. Distribution* of number of unrestored occlusal surfaces per patient†, by region.

*Median and inter-quartile ranges

†Among those with at least one unrestored occlusal surfaceand calculated at the patient level

Figure 4. Distribution* of percentage of unrestored occlusal surfaces with a questionable caries lesion, by region†.

*Median and inter-quartile ranges; P<0.05 differences across regions, adjusted for clustering within practices.

†Among those with at least one unrestored occlusal surface, calculated at the patient level.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by NIH grants U01-DE-16746, U01-DE-16747, and U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Brown LJ, Wall TP, Lazar V. Trends in total caries experience: Permanent and primary teeth. JADA. 2000;131:223–231. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2010/073.pdf.

- 3.Schoenberg NE, Gilbert GH. Dietary implications or oral health increments among African-American and white older adults. Ethnicity & Health. 1998;3:59–70. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1998.9961849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basting RT, Serra MC. Occlusal caries: Diagnosis and noninvasive treatments. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White JM, Eakle WS. Rationale and treatment approach in minimally invasive dentistry. JADA. 2000;131:13s–19s. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitts NB. Are we ready to move from operative to non-operative/preventive treatment of dental caries in clinical practice? Caries Res. 2004;38:294–304. doi: 10.1159/000077769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lussi A. Comparison of different methods for the diagnosis of fissure caries without cavitation. Caries Res. 1993;27:409–416. doi: 10.1159/000261572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton JC, Dennison JB, Stoffers KW, et al. A clinical evaluation of air abrasion treatment of questionable carious lesions: a 12-month report. JADA. 2001;132:762–769. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawle RF, Andlaw RJ. Has occlusal caries become more difficult to diagnose? Br Dent J. 1988;164:209–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ketley CE, Holt RD. Visual and radiographic diagnosis of occlusal caries in first permanent molars and in second primary molars. Br Dent J. 1993;174:364–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitts NB. Diagnostic tools and measurements-impact on appropriate care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:24–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouellet A, Hondrum SO, Pietz DM. Detection of occlusal carious lesions. Gen Dent. 2002;50:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pine CM, Bosch JJ. Dynamics of and diagnostic methods for detecting small carious lesions. Caries Res. 1996;30:381–388. doi: 10.1159/000262348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidd EAM, Ricketts DNJ, Pitts NB. Occlusal caries diagnosis: A changing challenge for clinician and epidemiologists. JJ Dent. 1993;21:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(93)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weerheijm KL, de Soet JJ, de Graaf J, et al. Occlusal hidden caries: A bacteriological profile. J Dent Child. 1990;57:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meiers J, Jensen M. Management of the questionable carious fissure: invasive vs noninvasive techniques. JADA. 1984;108:64–68. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton JC, Dennison JB, Stoffers KW, et al. Early treatment of incipient carious lesions: a two-year clinical evaluation. JADA. 2002;133:1643–1651. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balevi B. The management of suspicious or incipient occlusal caries: a decision tree analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36(5):392–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho JC, Thylstrup A, Ekstrand KR. Results after 3 years of non-operative occlusal caries treatment of erupting permanent first molars. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakhshandeh A, Qvist V, Ekstrand K. Sealing occlusal caries lesions in adults referred for restorative treatment: 2–3 years of follow-up. Clin Oral Investig. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0549-4. in print. (Epub 2011 Apr 9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bader JD, Shugars DA. The evidence supporting alternative management strategies for early occlusal caries and suspected occlusal dentinal caries. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2006;6:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert GH, William OD, Rindal DB, et al. The creation and development of The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA. 2008;139:74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, et al. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Gen Dent. 2009;57:270–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makhija SK, Gordan VV, Gilbert GH, Litaker MS, et al. Practitioner, patient and carious lesion characteristics associated with type of restorative material: findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA. 2011;142:622–632. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Retrieved January 4, 2012, from http://www.dentalpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Patient%20Characteristics%20of%20Enrolled%20QOC_010312.pdf.

- 26.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, et al. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:26–35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for occlusal primary caries among dentists in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA. 2010;141:171–184. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Heft MW, et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries based on radiographic images: findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent. 2009;57:654–663. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordan VV, Garvan CW, Richman J, et al. How dentists diagnose and treat defective restorations: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Oper Dent. 2009;34:664–673. doi: 10.2341/08-131-C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maupomé G, Gullion CM, Peters D, et al. A comparison of dental treatment utilization and costs by HMO members living in fluoridated and nonfluoridated areas. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:224–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekstrand KR, Martignon S, Christiansen ME. Frequency and distribution patterns of sealants among 15-year-olds in Denmark in 2003. Community Dent Health. 2007;24:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]