Abstract

The development of inhibitors against Abl has changed the landscape for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and cancer in general. Beginning with the monumental discovery and approval of imatinib for CML, a second generation of inhibitors, nilotinib and dasatinib, has now gained approval for the treatment of CML. Notably, these second-generation inhibitors are active against many of the mutations in the Abl kinase that confer resistance to imatinib. However, resistance remains a major problem, and new inhibitors such as ponatinib and GNF2/GNF5 have been developed, with activity towards the common gatekeeper T315I mutation. We review here the mechanisms of Abl inhibition with an emphasis on structural elements that are important for the selectivity and design of new molecules. In particular, we focus on how changes in the conformation of the P-loop, the activation loop, the DFG motif, and other structural elements of Abl have been instrumental in developing an understanding of inhibitor binding.

Keywords: BCR-ABL, X-ray crystal structure, imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, ponatinib

Introduction

Although the hypothesis that chromosomal abnormalities might play a crucial role in neoplasia was put forward more than a century ago by von Hansemann in 1880, the first experimental evidence in support of this hypothesis was provided by Nowell and Hungerford in 1960,1 who discovered a chromosomal abnormality consistently associated with human chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Nowell and Hungerford1 analyzed samples derived from 7 patients suffering from what was known at that time as chronic granulocytic leukemia. Each patient harbored a similar “minute chromosome,” and none showed any other chromosomal abnormality.1 Extensive analyses of clinical samples from CML patients have shown that this disease provides a paradigm of the genetic lesions associated with cancer because over 95% of the cases involve such an abnormality. We now know that this abnormal chromosome results from a reciprocal translocation between chromosome 9 at band q34 and chromosome 22 at band q11. The resulting hybrid chromosome has been named the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, in honor of the city in which it was discovered. Molecular cloning studies conducted in the 1980s showed that this translocation fuses the breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) gene with the Abl gene and creates the BCR-ABL oncogene,2 whose expression is responsible for more than 90% of CMLs.3 The discovery of the Ph chromosome and its encoded BCR-ABL oncogene were remarkable “firsts” as they paved the way for monumental advances in both basic and clinical research of CML and the study of cancer in general. At a minimum, BCR-ABL showed the research community that cellular homologs of viral oncogenes (in this case, v-abl) could be linked to a human disease state. Furthermore, the Ph chromosome proved, for the first time, that a chromosomal translocation could be linked to a given disease and even serve as a marker. Together, these findings laid the foundation for the development of one of the most successful targeted therapeutics of all time, imatinib (Gleevec, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ). Clinical studies suggest that the overall survival rate for newly diagnosed chronic-phase patients treated with imatinib at 5 years is 89%. Remarkably, an estimated 93% of imatinib-treated patients remain free from disease progression to the accelerated phase or blast crisis.4 Basic and clinical studies with imatinib have yielded a wealth of information, which include crystal structures of the ABL kinase domain in complex with imatinib, and important insights into the mechanisms of imatinib resistance.5 A number of studies indicate that the mechanism that accounts for the majority of imatinib-resistant leukemias, in vivo, is mutation of the BCR-ABL gene itself. Mutations within the kinase domain are the most common, and more than 90 such mutations that result in imatinib resistance have been described.6 Of these, the mutation that results in the substitution of a threonine residue with isoleucine at amino acid position 315 (T315I) appears to be most common and also most dangerous as it appears to be resistant to some of the second-generation drugs that inhibit most other mutations. In this review, we describe the development of imatinib and the derivation of second-generation inhibitors for the treatment of CML, which have greatly benefited by crystallographic studies that have provided a rational approach for the synthesis of these new molecules.

Kinase Domain: Active versus Inactive

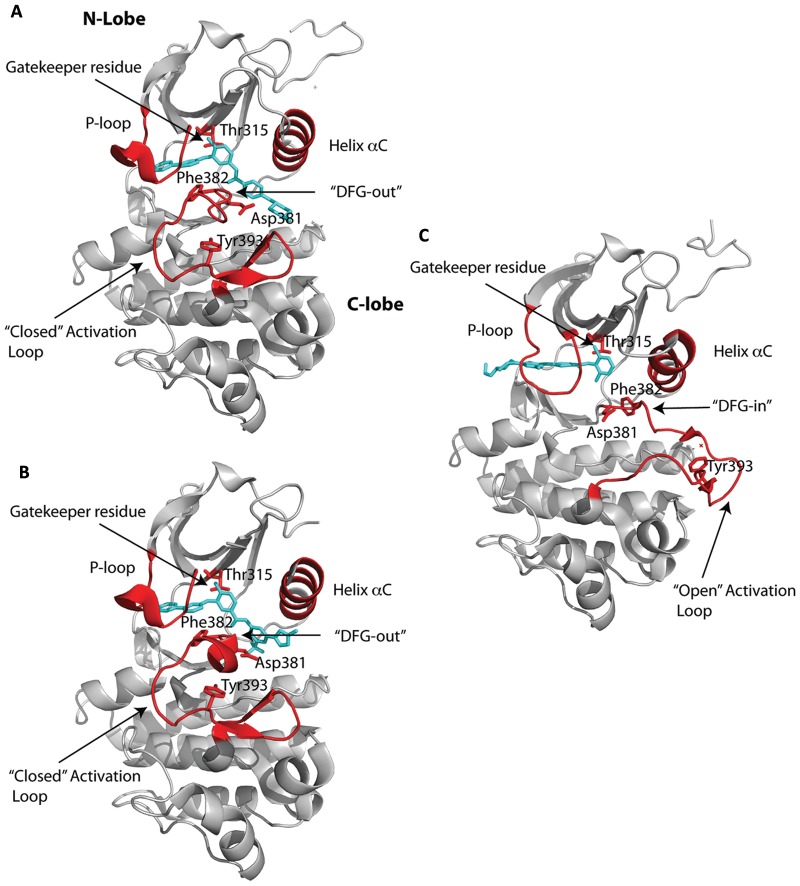

The first crystal structure of a protein kinase was solved in 1991 by Taylor and colleagues7 of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). The PKA structure has served as a template for understanding the architecture of other kinases,8 including the Abl kinase.9 Thus, with reference to PKA, the catalytic domain of Abl is bilobal, comprising an N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) and a larger C-terminal lobe (C-lobe) (Fig. 1). The ATP molecule binds a deep cleft between the 2 lobes, and the peptide substrate binds primarily to the C-lobe. The N-lobe includes a 5-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β1-β5) and an α-helix (αC), whereas the C-lobe is predominantly α-helical and includes long helices that span the width of the catalytic core (Fig. 1). The loop between strands β1 and β2 in the N-lobe is glycine rich (GXGXΦG; Φ in Abl is Tyr253) and is known as the “P-loop” (or G-loop). The P-loop is highly flexible and drapes over the β- and γ-phosphates of the bound ATP molecule. The γ-phosphate also interacts with the “catalytic loop” (in the C-lobe), which is essential for catalysis and also supplies the catalytic base (Asp363 in Abl) for the phosphoryl transfer reaction. The adenine of bound ATP makes 2 hydrogen bonds with the main chain atoms of the “interlobe connector” (or the hinge) linking the N- and C-lobes. A residue at the back of the ATP binding pocket is termed the “gatekeeper” and is an important determinant of inhibitor binding and specificity.10 Abl has a threonine (Thr315) at the gatekeeper position (Fig. 1), which is commonly replaced by an isoleucine (T315I) in patients who develop a resistance to imatinib.11

Figure 1.

ATP-competitive inhibition. Crystal structures of the Abl kinase domain in complex with ATP competitors: (A) imatinib, (B) nilotinib, and (C) dasatinib. The inhibitors are shown in cyan bound to the cleft between the N- and C-lobes of the kinase domain. The P-loop, activation loop, DFG motif, and helix αC are highlighted in red. Also highlighted in red are key residues, namely Thr315, the gatekeeper residue; Asp381 and Ph382, which comprise the first 2 residues of the DFG motif; and Tyr393 in the activation loop that is phosphorylated to activate the kinase. Note that imatinib and nilotinib bind to the inactive state of the kinase domain with the activation loop in the “closed” conformation and the DFG motif in the “in” conformation. By contrast, dasatinib binds the active state of the kinase with the activation loop in an “open” conformation and the DFG motif in the “out” conformation.

The most flexible segment in a kinase is the “activation loop” that stems from the C- lobe and that plays a central role in the activation of the kinase (Fig. 1). The loop is centrally located and contains a conserved “DFG” motif (Asp381-Phe382-Gly383 in Abl) at its N-terminus, while the middle portion contains the tyrosine (Tyr393 in Abl) or serine/threonine that is phosphorylated for the activation of a kinase (Fig. 1). In the active state, the activation loop is in an open or extended conformation, wherein the aspartate of the DFG motif points “in” towards the ATP binding site and coordinates to the catalytic Mg2+ ion(s) and the C-terminal portion of the loop forms part of the platform for peptide substrate binding. This open or extended conformation of the activation loop is very similar in all activated kinases.

In contrast, the activation loop can adopt different conformations in inactive kinases. Indeed, the majority of Abl inhibitors bind to the inactive state of the kinase. This was first shown by Kuriyan and colleagues in their structure of the catalytic domain of the Abl kinase bound to a variant of imatinib that lacked the piperazinyl group.9 Up until then, the in vivo potency of drugs such as imatinib was thought to derive from binding to the active state of the kinase. The structure revealed the opposite. The drug bound to the inactive state of Abl, in which the activation loop folds in towards the ATP binding site (Fig. 1A), the middle portion of the loop (containing Tyr393) blocks peptide substrate binding, and Asp381 of the DFG motif rotates away from the active site, unable to coordinate to the catalytic metal (Fig. 1A). This “DFG-out” conformation of the activation loop lends to a “specificity pocket” beyond the gatekeeper residue, bordered by the activation loop on one side and helix αC on the other and varying in size between different inactive kinases. Altogether, the structure suggested the possibility of developing specific protein kinase inhibitors targeted to the characteristic inactive conformation(s) of each kinase.

From long molecular dynamics simulations,12 the DFG flip from “in” to “out” appears to be the result of protonation of the aspartate following catalysis: aiding in ADP release, a rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle. Molecular dynamics simulations also point to the existence of other “intermediate” states in Abl where, for example, the DFG motif is “in” but helix αC is displaced “out,” resulting in a salt bridge between Glu286 and Arg386.12 These intermediates may offer new opportunities for inhibitor design against Abl. Also, from bioinformatics analysis, the active state of a kinase appears to be solidified in part by conserved patterns of hydrophobic residues or “spines” connecting the N- and C-lobes.8,13 Intriguingly, the gatekeeper Thr315 in Abl lies at the tip of one such hydrophobic spine, and substitution by bulkier isoleucine has been suggested to lock the spine in the active form of Abl.14

Inhibitors

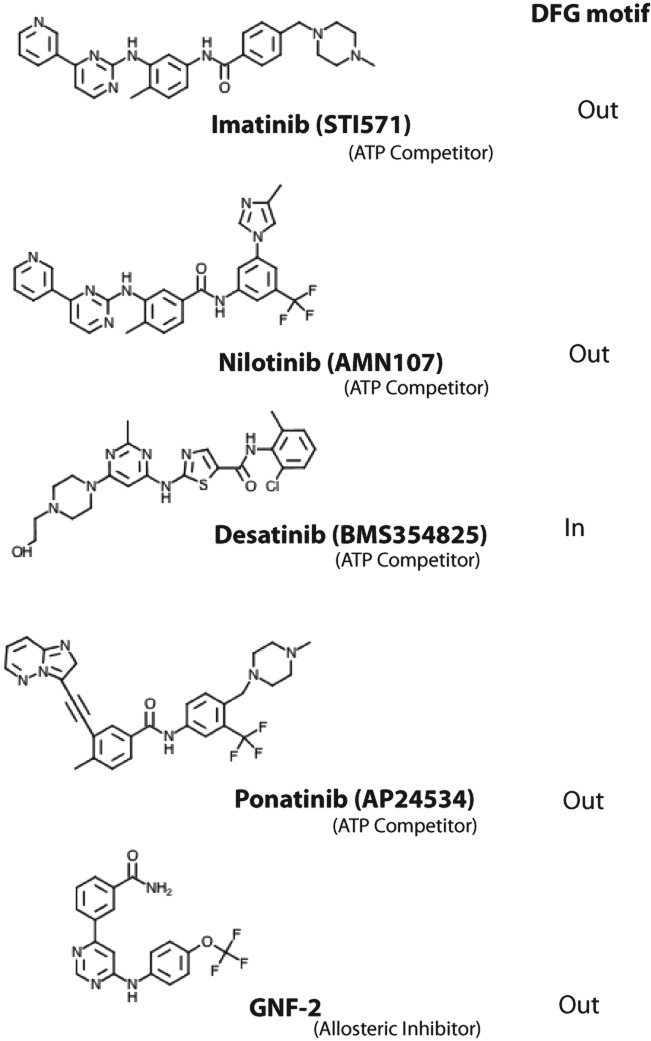

The successful development of imatinib as a Bcr-Abl inhibitor has changed the landscape for CML treatment.15 Resistance to imatinib, however, due to mutations in the kinase domain has prompted a search for inhibitors capable of overriding the mutations. Nilotinib and dasatinib are more potent inhibitors and have gained regulatory approval for second-line use in CML patients who develop a resistance to imatinib (Figs. 1 and 2).16-20 However, all 3 drugs are resistant to the T315I mutation. Recent efforts in CML treatment have thus been geared to the development of inhibitors that can overcome this common gatekeeper mutation. Among the drugs that show activity towards T315I are ponatinib (AP2453, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) (Fig. 2) and SGX393 (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN).21,22 Like imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, ponatinib and SGX393 are ATP competitors but designed to accommodate the T315I side chain. Another approach to overcoming the T315I mutation is to target regions of Bcr-Abl outside of the ATP binding site. ON44580 (Onconova Therapeutics, Newtown, PA) has shown promise in this regard as it appears to bind to the substrate binding surface rather than the ATP binding site.23 GNF2/GNF-5 (Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is an example of an allosteric inhibitor that binds to the myristoyl pocket near the C-terminus of the Abl kinase domain and transmits structural changes to the ATP binding site (Fig. 2).24 At present, imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib are the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs for the treatment of CML.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the ATP competitors imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, and ponatinib, as well as the allosteric inhibitor GNF-2.

Imatinib (STI-571)

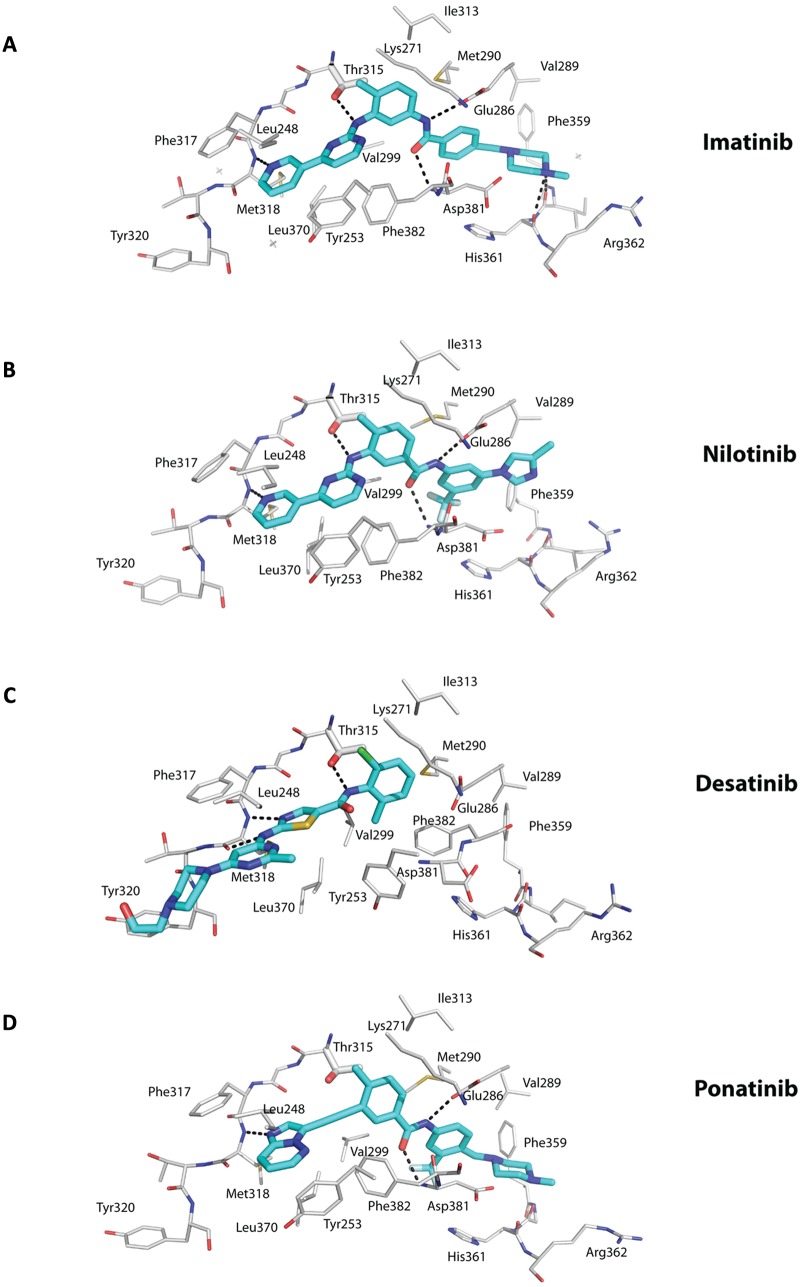

Crystal structures of Abl with imatinib were reported soon after the initial structure with a variant of imatinib that defined the DFG-out mode of inhibitor binding.9,25,26 Imatinib binds between the N- and C-lobes and spans almost the entire width of the kinase (Fig. 1A). The central phenyl ring of imatinib lies flush against the gatekeeper Thr315 residue, while the “leftmost” (pyridine and pyrimidine) and “rightmost” (benzamide and piperazine) groups are splayed at an approximately 120° angle and fit into the adenine and specificity pockets, respectively (Fig. 1A). As with the imatinib variant, the kinase is an inactive conformation, wherein the activation loop folds in towards the active site and the middle of the loop precludes peptide substrate binding. The DFG motif is in the DFG-out mode, whereby Phe382 swings towards the ATP binding site and Asp381 points away from the active site (Fig. 1A). Most of the interactions between the drug and the protein are van der Waals or hydrophobic in nature, with approximately 1,200 Å2 of surface area buried at the interface (Fig. 3A). The P-loop folds over the pyridine and pyrimidine rings in a “kinked” conformation as opposed to the extended conformation in active kinases (Fig. 1). In particular, Tyr253 from the kinked P-loop and Phe382 from the activation loop form part of the hydrophobic cage, along with residues such as Leu248, Phe317, and Leu370, around the adenine pocket (Fig. 3A). As such, the pyridine and pyrimidine groups of imatinib are effectively shielded from the solvent. By contrast, the benzamide and piperazine groups are more exposed to the solvent, with the most prominent van der Waals contacts coming from Val289 and Met290 on helix αC, Asp381 of the DFG motif, and Ile360 and His361 on the catalytic loop (Fig. 3A). There are a total of 6 hydrogen bonds between imatinib and Abl, involving the pyridine N and the main chain amide of Met318, the amino group of pyrimidine and the side chain hydroxyl of Thr315, the amide NH and the main chain carbonyl of Glu286, the amide CO and the main chain amide of Asp381, and the protonated piperazine and the main chain carbonyls of Ile360 and His 361 (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Interactions between the ATP competitors and the active site. The ATP competitors Imatinib (A), Nilotinib (B), Desatinib (C), and Ponatinib (D) are shown in cyan (carbon) and elemental colors (blue for N, red for O, yellow for S, gray for Fl, and green for Cl). The protein residues are shown in gray (carbons) and elemental colors. Hydrogen bonds are depicted in dashed lines. Note that imatinib and nilotinib bind the inactive state of Abl in a similar manner, including a hydrogen bond with the main chain amide of interlobe residue Met318, a hydrogen bond with the gatekeeper residue Thr315, hydrophobic interactions with Phe382 from the DFG motif in the “out” conformation, and hydrophobic interactions with Tyr253 from a kinked or collapsed P-loop, among others. Dasatinib lies more towards the “mouth” of the active site and lacks the pharmacore elements to enter the specificity pocket. As a consequence, the kinase is in the active state with the DFG motif in the “in” conformation. Ponatinib is characterized by a carbon-carbon triple bond (ethynyl linkage) between the methylphenyl and purine groups. There is a hydrogen bond to Thr315, and there is no steric interference when Thr315 is mutated to isoleucine.

Curiously, imatinib binds with much lower affinity to the Src kinase, even though the residues lining the adenine and specificity pockets are almost the same as in Abl.27 The inactive state of c-Src differs from that of Abl in that the DFG motif does not flip out but, instead, helix αC swings out, away from the active site.28,29 As such, it had been assumed that the low affinity of imatinib for Src is the direct result of its inability (or a higher free energy cost) to adopt the Abl-like inactive conformation.9,27 From more recent crystal structures, however, it now seems that differences in interactions between the P-loop and the pyridine group of imatinib may be a more critical component of Abl/Src selectivity.30

Imatinib-Resistant Mutations

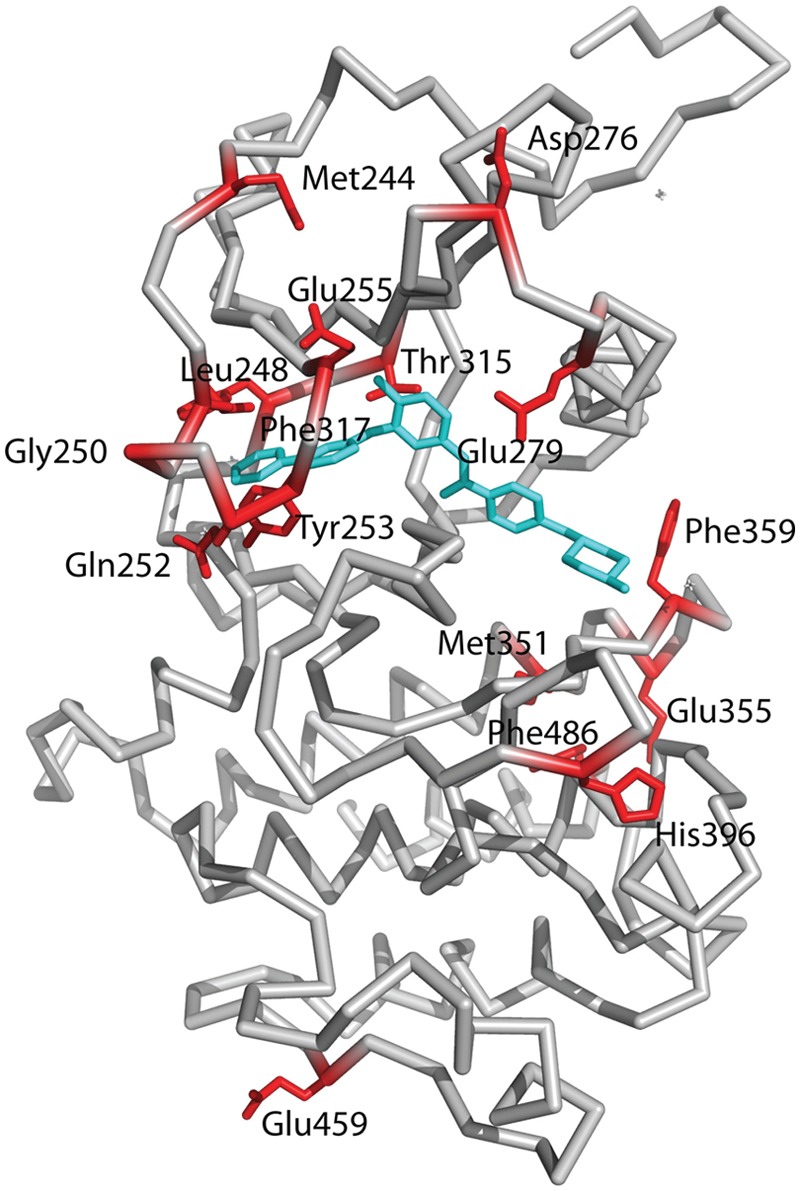

Over a third of CML patients develop a resistance to imatinib, due mainly to mutations within the Bcr-Abl kinase domain. Indeed, more than 90 different types of mutations, affecting more than 55 amino acids, have now been identified.6,31-34 Based on the structures, some of these mutations affect amino acids that directly interact with imatinib, while others appear to affect the ability of Bcr-Abl to acquire the inactive conformation for imatinib binding. The most common mutations map at or near the gatekeeper residue (T315I, F317L), the P-loop (M244V, G250E, Q252H/R, Y253F/H, E255K/V), the activation loop (H396R), and the C-lobe (M351T, E355G, F359V/C/I, F486S) (Fig. 4). Substitution of Thr315 by isoleucine is expected to sterically interfere with imatinib binding and also result in the loss of a hydrogen bond with the drug (Fig. 3A). As noted above, Thr315 lies at the tip of a hydrophobic “spine” that links the N- and C-lobes and stabilizes the active kinase conformation. Thus, a T315I mutation, in addition to steric hindrance, also appears to lock the hydrophobic spine in the active form of the Abl kinase.14 A less common T315A mutation is less sensitive to imatinib binding, resulting in the loss of the hydrogen bond between the aminopyrimidine and the hydroxyl group of Thr315 (Fig. 3A). Phe317 is near the gatekeeper Thr315 and stacks partially on the pyridine ring of imatinib. Thus, a F317I mutation may weaken imatinib binding via the loss of π-π interactions. In addition to T315I, mutations in the P-loop are most frequently associated with poor prognosis in CML patients,35,36 although this conclusion is under some debate.37 Upon imatinib binding, the P-loop adopts a kinked conformation that allows Tyr253 to interact with the inhibitor (Fig. 3A). The Y253H/F substitutions would thus break the hydrogen bonds that the Tyr253 hydroxyl establishes with imatinib, while mutations G250E, Q252H/R, and E255K may destabilize the distorted P-loop conformation required for imatinib binding. Similarly, the His396R mutation in the activation loop, close to activating Tyr393, may perturb a putative hydrogen bond with Asp414 and stacking interactions with Phe401 that appear to be required to maintain the activation loop in a closed conformation. Met351 and Glu355 lie on a helix in the C-lobe that is close to the interlobe interface (Fig. 4). As such, the M351T and E355G mutations may disturb the relative orientation of N- and C-lobes required for imatinib binding. Phe359 makes direct van der Waals contacts with the piperazine ring of imatinib, and substitution by valine (F359V) would disrupt these interactions.

Figure 4.

Mapping of residues on the Abl kinase domain that are commonly mutated in imatinib resistance. Most of the residues map close to the imatinib binding site, including Th315, the gatekeeper residue; Leu248, Gly250, Gln252, and Tyr252 that map to the P-loop; Met351, Glu355, and Phe359 that map to the activation loop; and Glu279 that maps to helix αC. Some residues such as Asp276 and Glu459 map further away from the imatinib binding site, and it is not clear how they confer resistance to imatinib.

Nilotinib (AMN107)

Nilotinib is a more potent (>20-fold) inhibitor of Bcr-Abl and exhibits activity towards the majority of imatinib-resistant mutations.17,18 Nilotinib was developed from imatinib to incorporate alternative groups to N-methylpiperazine for binding Abl while retaining the elements to make hydrogen bonds with Glu286 and Asp381 (Fig. 3B).17,38 As with imatinib, nilotinib binds to the inactive conformation of Abl, wherein the activation loop adopts the closed conformation and Asp381 and Phe382 are in the DFG-out mode (Fig. 2B).17,38 The P-loop folds over the adenine pocket in the kinked conformation, and a cage of hydrophobic residues (Leu248, Tyr253, Phe317, Phe320, and Leu370) encloses the pyridine and pyrimidine groups. In addition, as with imatinib, hydrogen bonds are made between the pyridine N and Met318, the amino group of pyrimidine and Thr315, and the amide groups with Glu286 and Asp381 (Fig. 3B). As such, the majority of nilotinib-Abl interactions overlap with those in the imatinib-Abl complex (Fig. 3A and 3B). The higher binding affinity of nilotinib for Abl derives from van der Waals interactions with the unique trifluoromethyl and imidazole substituents on the phenyl ring (Figs. 2B and 3B).17,38

Despite the similarities to imatinib, nilotinib is active against many of the mutants resistant to imatinib, including L248V, G250E, Q252H, and F317L. How does one then explain activity towards these mutations? It has been suggested that nilotinib derives a greater proportion of its binding affinity from the interactions made with the trifluoromethyl and imidazole substituents.17 Thus, mutations that cluster around the pyridine and pyrimidine groups appear to have less of an overall effect on nilotinib binding. However, nilotinib is also less sensitive to mutations on the C-lobe (e.g., M315T, E355G, and F486S). This may reflect the fact that the imidazole group in nilotinib is involved in less stringent interactions with the C-lobe when compared to the methylpiperazine group in imatinib.17 One key mutation against which nilotinib is inactive is T315I,17 the gatekeeper mutation, reflecting the similarities in interactions over this region (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Dasatinib (BMS-354825)

Dasatinib is unusual in that it binds to the activated state of Abl, wherein the activation loop is in an open, extended conformation (Fig. 3C).39 Moreover, the DFG motif is “in” with Asp381 oriented towards the ATP binding site. Unlike imatinib and nilotinib, dasatinib does not protrude into the specificity pocket, leaving the activation loop “free” to adopt the extended conformation.39 Thus, dasatinib binds primarily in the adenine pocket of Abl. That is, the aminothiazole group occupies the adenine pocket, while the pyrimidine and piperazine groups extend beyond the interlobe connector and are solvent exposed (Figs. 1C and 3C). In all, dasatinib is smaller than imatinib and makes fewer interactions, and yet, it is a more potent inhibitor of Bcr-Abl. It has been suggested that the increase in binding affinity of dasatinib over imatinib may derive from an ability to recognize multiple states of Bcr-Abl.39 That is, when dasatinib is modeled in the inactive state of Abl, there do not appear to be any major steric clashes to prevent binding. However, from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) studies, dasatinib appears to bind primarily to the active state of Abl.40 Since the active state of a kinase is thought to be more restricted in conformation than the inactive state, it is possible that the higher affinity of dasatinib for Abl derives from a lower entropic penalty on binding to the active state. Like nilotinib, dasatinib is sensitive against most of the imatinib-resistant mutations, with the notable exception of the gatekeeper T315I mutation.16 The activity of dasatinib towards the P-loop mutations (M244V, G250E, Q252H/R, Y253F/H, and E255K/V) is explained by the fact that the P-loop in the dasatinib-Abl complex is extended and not well ordered, rendering these mutations as less important.39 Also, other mutations that affect the ability of Abl to acquire inactive conformation for imatinib binding are less relevant since dasatinib binds almost exclusively to the active conformation (Figs. 1C and 3C).

Ponatinib (AP24534)

Ponatinib was designed to overcome the T315I gatekeeper mutation.21 The key feature of the drug is a carbon-carbon triple bond (ethynyl linkage) between the methylphenyl and purine groups that can accommodate the isoleucine side chain without steric interference (Figs. 2D and 3D). Also, there is no loss of a hydrogen bond when Thr315 is mutated to isoleucine (Fig. 3D). Otherwise, ponatinib binds to Abl in an imatinib/nilotinib-like (DFG-out) mode and makes similar interactions, including hydrogen bonds with the main chain carbonyl of Met318, side chain of Glu286, and main chain amide of Asp381 (Fig. 3D).21 Also, the drug makes intimate van der Waals contacts with Tyr253 due to the kinked or compact conformation of the P-loop and with Phe382 due to the DFG-out mode of the activation loop. In addition to the gatekeeper T315I/A mutation, ponatinib is active against many of the other imatinib-resistant mutations, including M244V, G250E, Q252H, Y253F/H, E255K/V, F317L, M351T, and F359V, among others.21 The activity of ponatinib towards these mutations invokes a similar rationale as for nilotinib, whereby the drug makes multiple points of contact so that mutation of a residue has less effect on the overall binding affinity of the drug.21

GNF-2/GNF-5

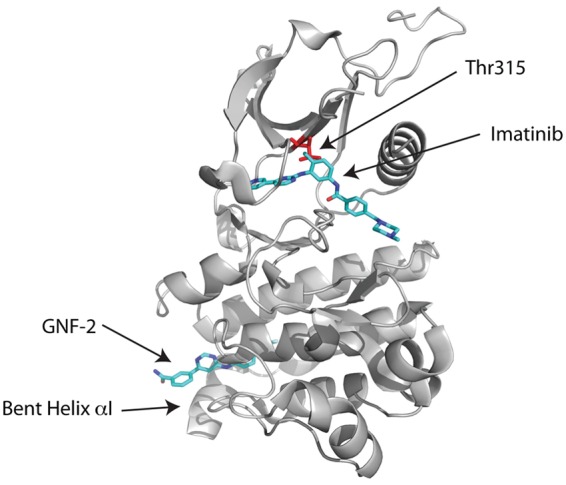

GNF-2 and its analog GNF-5 offer an alternative strategy to overcome the gatekeeper T315I mutation. Unlike imatinib/nilotinib/dasatinib/ponatinib, GNF-2/GNF-5 is an allosteric inhibitor of Bcr-Abl that enters the myristate binding pocket at the base of the C-lobe in the Abl kinase domain (Figs. 2E and 5). A crystal structure of the GNF-2/imatinib/Abl ternary complex has been determined24 and shows GNF-2 binding to the myristate site in an extended conformation in an analogous manner to the myristoyl group in the myristoylated peptide/imatinib/Abl ternary complex structure.41 Moreover, as in the myristoylated peptide/imatinib/Abl ternary complex, the binding of GNF-2 induces a sharp bend in the C-terminal helix (αI) of the kinase domain that appears to favor the inactive conformation (Fig. 5). Imatinib is bound to the ATP site in much the same manner as in the imatinib/Abl binary complex with its central phenyl ring apposed against Thr315 (Fig. 5). A key question then is how GNF-2/GNF-5 can act cooperatively with an ATP competitor such as nilotinib, bound to a site approximately 30 Å away from the myristate site, to suppress the T315I mutation? The answer appears to lie, at least partially, in the dynamics of the Abl kinase domain. From hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry,24 the binding of GNF-5 causes a dynamic perturbation of residues near Thr315 that allows ATP-competitive inhibitors to tolerate isoleucine at this position. How this long-range effect is transmitted from the myristate to the ATP pocket is somewhat mysterious, and the “networks of connectivity” between the 2 sites remain to be characterized.

Figure 5.

Allosteric inhibition. Crystal structure of the Abl kinase domain in complex with imatinib and GNF-2. GNF-2 binds to the myristate site and induces a bend in the C-terminal helix (αI) in the C-lobe of the kinase domain. Although the GNF-2 binding site is far away from the imatinib binding site, the binding of GNF-2 causes a dynamic perturbation of residues near Thr315 that allows imatinib to tolerate isoleucine at this position.

Conclusions

The remarkable success of imatinib has spurred the development of new drugs that target not only Abl but also other kinases in cancer. Structural biology has played a key role in the development of these new drugs that target not only the ATP binding site but also other sites on the kinases. The development of imatinib and second- and third-generation BCR-ABL inhibitors has exemplified how the ingenuity of collaborating chemists, oncologists, and structural biologists allowed us to keep pace with the mutations that arise in tumors as a result of “selective” pressures put upon them during treatment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: E.P.R. is a stockholder, board member, and consultant for Onconova Therapeutics.

Funding: The author(s) received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: E.P.R. was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL080666).

References

- 1. Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. A minute chromosome in human granulocyte leukemia. Science. 1960;142:1497 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heisterkamp N, Stam K, Groffen J, de Klein A, Grosveld G. Structural organization of the bcr gene and its role in the Ph’ translocation. Nature. 1985;315(6022):758-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shah NP, Sawyers CL. Mechanisms of resistance to STI571 in Philadelphia chromosome-associated leukemias. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7389-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Druker BJ. Translation of the Philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood. 2008;112(13):4808-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eck MJ, Manley PW. The interplay of structural information and functional studies in kinase drug design: insights from BCR-Abl. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(2):288-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hochhaus A, La Rosee P, Muller MC, Ernst T, Cross NC. Impact of BCR-ABL mutations on patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(2):250-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knighton DR, Zheng J, Ten Eyck LF, et al. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protien kinase. Science. 1991;253:407-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kornev AP, Taylor SS. Defining the conserved internal architecture of a protein kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804(3):440-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289(5486):1938-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu Y, Shah K, Yang F, Witucki L, Shokat KM. A molecular gate which controls unnatural ATP analogue recognition by the tyrosine kinase v-Src. Bioorg Med Chem. 1998;6(8):1219-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293(5531):876-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shan Y, Seeliger MA, Eastwood MP, et al. A conserved protonation-dependent switch controls drug binding in the Abl kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(1):139-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kornev AP, Haste NM, Taylor SS, Eyck LF. Surface comparison of active and inactive protein kinases identifies a conserved activation mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(47):17783-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Azam M, Seeliger MA, Gray NS, Kuriyan J, Daley GQ. Activation of tyrosine kinases by mutation of the gatekeeper threonine. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(10):1109-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Sawyers CL. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305(5682):399-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, et al. Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(2):129-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2542-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2531-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lombardo LJ, Lee FY, Chen P, et al. Discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methyl- phenyl)-2-(6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazin-1-yl)-2-methylpyrimidin-4- ylamino)thiazole-5-carboxamide (BMS-354825), a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical assays. J Med Chem. 2004;47(27):6658-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(5):401-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Hare T, Eide CA, Tyner JW, et al. SGX393 inhibits the CML mutant Bcr-AblT315I and preempts in vitro resistance when combined with nilotinib or dasatinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(14):5507-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jatiani SS, Cosenza SC, Reddy MV, et al. A non-ATP-competitive dual inhibitor of JAK2 and BCR-ABL kinases: elucidation of a novel therapeutic spectrum based on substrate competitive inhibition. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(4):331-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang J, Adrian FJ, Jahnke W, et al. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature. 2010;463(7280):501-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manley PW, Cowan-Jacob SW, Buchdunger E, et al. Imatinib: a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 5:S19-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagar B, Bornmann WG, Pellicena P, et al. Crystal structures of the kinase domain of c-Abl in complex with the small molecule inhibitors PD173955 and imatinib (STI-571). Cancer Res. 2002;62(15):4236-43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seeliger MA, Nagar B, Frank F, Cao X, Henderson MN, Kuriyan J. c-Src binds to the cancer drug imatinib with an inactive Abl/c-Kit conformation and a distributed thermodynamic penalty. Structure. 2007;15(3):299-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu W, Harrison SC, Eck MJ. Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature. 1997;385(6617):595-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levinson NM, Kuchment O, Shen K, et al. A Src-like inactive conformation in the abl tyrosine kinase domain. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(5):e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seeliger MA, Ranjitkar P, Kasap C, et al. Equally potent inhibition of c-Src and Abl by compounds that recognize inactive kinase conformations. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2384-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B, et al. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(2):117-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nardi V, Azam M, Daley GQ. Mechanisms and implications of imatinib resistance mutations in BCR-ABL. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11(1):35-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Azam M, Latek RR, Daley GQ. Mechanisms of autoinhibition and STI-571/imatinib resistance revealed by mutagenesis of BCR-ABL. Cell. 2003;112(6):831-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cowan-Jacob SW, Guez V, Fendrich G, et al. Imatinib (STI571) resistance in chronic myelogenous leukemia: molecular basis of the underlying mechanisms and potential strategies for treatment. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2004;4(3):285-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Branford S, Rudzki Z, Walsh S, et al. Detection of BCR-ABL mutations in patients with CML treated with imatinib is virtually always accompanied by clinical resistance, and mutations in the ATP phosphate-binding loop (P-loop) are associated with a poor prognosis. Blood. 2003;102(1):276-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soverini S, Colarossi S, Gnani A, et al. Contribution of ABL kinase domain mutations to imatinib resistance in different subsets of Philadelphia-positive patients: by the GIMEMA Working Party on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(24):7374-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Jones D, et al. Frequency and clinical significance of BCR-ABL mutations in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib mesylate. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1767-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cowan-Jacob SW, Fendrich G, Floersheimer A, et al. Structural biology contributions to the discovery of drugs to treat chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63(Pt 1):80-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tokarski JS, Newitt JA, Chang CY, et al. The structure of dasatinib (BMS-354825) bound to activated ABL kinase domain elucidates its inhibitory activity against imatinib-resistant ABL mutants. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vajpai N, Strauss A, Fendrich G, et al. Solution conformations and dynamics of ABL kinase-inhibitor complexes determined by NMR substantiate the different binding modes of imatinib/nilotinib and dasatinib. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18292-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nagar B, Hantschel O, Young MA, et al. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Cell 2003;112(6):859-871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]