Abstract

Ameloblastic carcinoma (AC) is a rare malignant lesion with characteristic histologic features and clinical behavior that dictates a more aggressive surgical approach than that of a simple ameloblastoma. The tumor cells resemble the cells seen in ameloblastoma, but they show cytologic atypia. Direct extension of the tumor, lymph node involvement, and metastasis to various sites (frequently the lung) have been reported. Wide local excision is the treatment of choice. Regional lymph node dissection should be considered and performed selectively. Literature shows that radiotherapy and chemotherapy is of limited value for the treatment of AC. A case of AC of maxillary region is presented here. Clinical/histological characteristics of this tumor and current knowledge on the classification of odontogenic malignancies are also discussed.

Keywords: Ameloblastic carcinoma, malignant ameloblastoma, malignant transformation in ameloblastoma

INTRODUCTION

Ameloblastomas are reported to constitute about 1–3% of all jaw tumors and cysts,[1] and it is the most frequently reported odontogenic tumor. This neoplasm is generally recognized as a locally invasive tumor that demonstrates considerable tendency to recur but rarely behaves aggressively or shows metastatic dissemination. The malignant variant of ameloblastoma has been the subject of considerable discussion and controversy for many years. It is a consensus that any ameloblastoma that metastasizes is malignant, even if the tumor shows benign histological features. Malignancies associated with ameloblastoma have been designated by a variety of terms,[2,3] including malignant ameloblastoma, ameloblastic carcinoma (AC), metastatic ameloblastoma, and primary intra-alveolar epidermoid carcinoma (PIOC). Of these, two have frequently been used interchangeably, and the difference between malignant ameloblastoma and AC should be known. The latter reveals malignant histopathological features independent of the presence of metastasis,[4] whereas malignant ameloblastomas metastasize as well-differentiated benign cells.[5] We here present a rare case of maxillary AC and a discussion on its characterization.

CASE REPORT

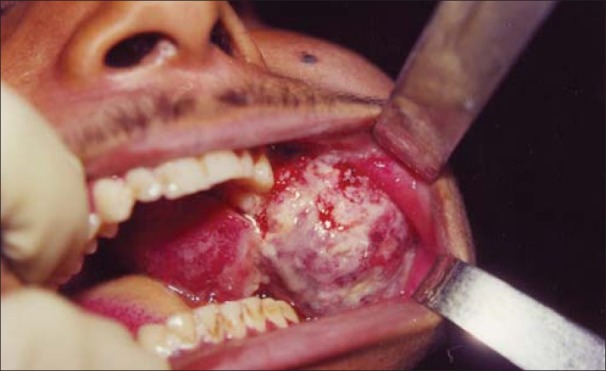

An 18-year-old male presented in the Maxillofacial Surgery Department with a 1-year history of left cheek swelling, which had suddenly started increasing in size over the last few weeks. He reported discharge from his nasal passage. Swelling was present over left cheek region, extending superiorly from zygomatic arch to body of mandible inferiorly. The swelling was firm, non-tender, not cystic, not warm, and not attached to overlying skin. Intra-orally, an ulcerated mass was seen measuring 5 × 4 × 3.5 cm, involving cheek mucosa, upper vestibule in molar region, and left hard and soft palate with faucial pillars [Figures 1 and 2]. There was an associated burning sensation and fetid odor. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy or mass in the neck.

Figure 1.

Preoperative frontal view

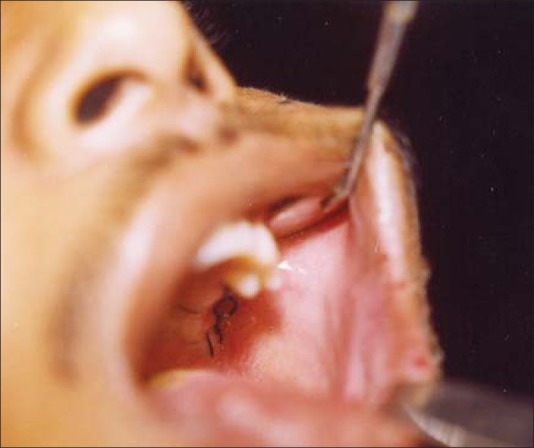

Figure 2.

Preoperative intraoral view

Extra-oral plain radiographs revealed a multilocular radiolucency of the left posterior maxilla with ill-defined margins.

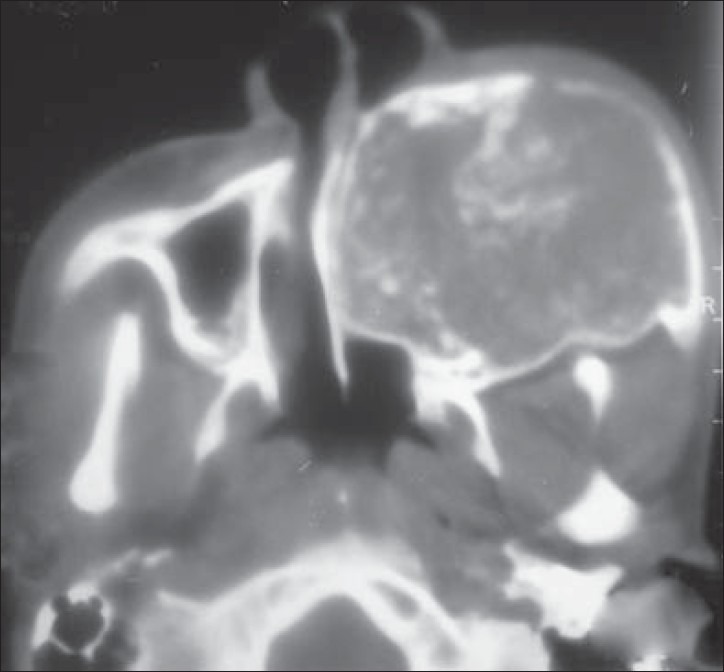

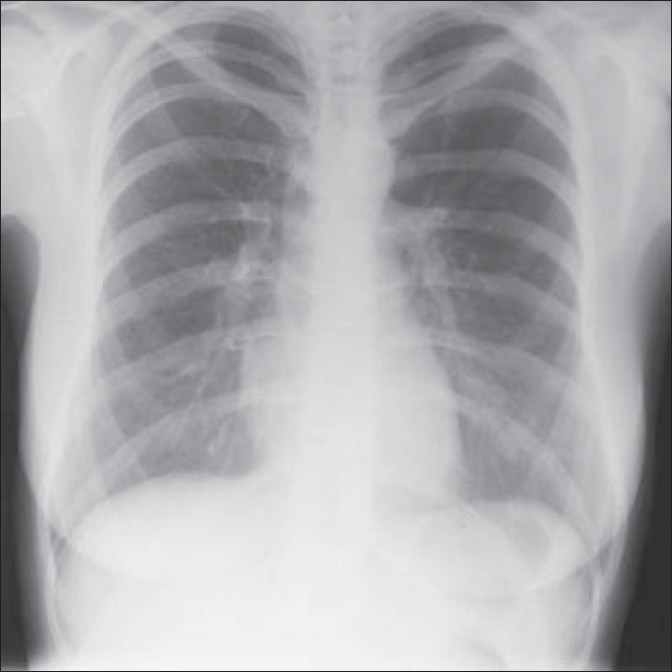

Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass involving the left posterior maxilla, infiltrating the left maxillary sinus, nasal cavity with left turbinates and meatus, and extending towards the orbital floor. Nasal septum was deviated to the right. On the palate, the mass extended almost to the midline [Figures 3 and 4]. Chest X-ray [Figure 5] and ultrasonogram neck failed to reveal any metastatic disease. An incisional biopsy was done and the initial report indicated AC. After routine work-up, the patient was operated under general anesthesia for composite block resection with left subtotal maxillectomy. Left orbital floor tissues were sent for frozen section and were free of any disease; hence, only orbital floor was removed and the patient was put on close follow-up.

Figure 3.

Preoperative CT scan showing medial extent

Figure 4.

Preoperative CT scan in coronal view

Figure 5.

Chest X-ray

The resected specimen measured 6×5×4 cm. Histopathology reported that neoplastic cells formed nests of cells with distinctive features of ameloblastic differentiation, showing peripheral palisading of basaloid cells coupled with the typical stellate reticulum arrangement. Areas of clear cell differentiation were present. The degree of mitotic activity, presence of necrotic foci, and infiltrative characteristics of the tumor supported the malignant nature of this ameloblastic neoplasm. The excisional biopsy report confirmed the incisional biopsy of AC. Post-operative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged home after 1 week [Figures 6 and 7].

Figure 6.

Postoperative frontal view

Figure 7.

Postoperative intraoral view

DISCUSSION

Numerous classifications[6–8] have been given and modified time and again for odontogenic epithelial malignancies. However, in 1984, Slootweg and Müller[6] emphasized that ameloblastoma may exhibit malignant features other than metastasis also and suggested the new classification system for malignant tumors with features of ameloblastoma, based on other characteristics of malignancy:

Type 1: PIOC ex odontogenic cyst

-

Type 2:

- Malignant ameloblastoma

- AC, arising de novo, ex ameloblastoma or ex odontogenic cyst

-

Type 3: PIOC arising de novo

- Non-keratinizing

- Keratinizing

The current classifications, however, did not consider benign histopathological features at the primary site and malignant features at the metastatic tumor site. Over years of controversies, it was accepted that the term AC should be used to designate lesions that exhibit histologic features of both ameloblastoma and carcinoma. The tumor may metastasize and histologic features of malignancy may be found in the primary tumor, the metastases, or both. The term malignant ameloblastoma should be confined to those ameloblastomas that metastasize despite an apparently typical benign histology in both the primary and the metastatic lesions.

Most of the studies conducted until now for malignancy in ameloblastoma were on mandibular cases because maxillary AC are very rare, and mostly single-case report studies have been published for the same. In 2009, Kruse et al.[9] based on 60 years of evidence-based literature review of malignancy in maxillary ameloblastomas recommended and presented a novel classification.

Type 1: Malignant ameloblastoma

-

(a)

Metastasis with features of an ameloblastoma (well differentiated)

-

(b)

Metastasis with malignant features (poorly differentiated)

Type 2: AC arising from an ameloblastoma

-

(a)

Without metastasis

-

(b)

Metastasis with features of an ameloblastoma (well differentiated)

-

(c)

Metastasis with malignant features (poorly differentiated)

Type 3: AC with unknown origin histology

-

(a)

Without metastasis

-

(b)

Metastasis with features of an ameloblastoma (well differentiated)

-

(c)

Metastasis with malignant features (poorly differentiated)

This novel classification considers the unknown origin as well as primary ameloblastomas with metastases and their histopathological features of malignancy without previous evidence of malignancy in the primary localization.[9] It separates AC arising in ameloblastoma and arising de novo into different groups.

AC is an extremely rare, aggressive malignant epithelial odontogenic tumor with a poor prognosis. Its incidence is greater than that of malignant ameloblastoma by a 2:1 ratio. Two-thirds of these tumors arise from the mandible while one-third originate in the maxilla.[6] It occurs in a wide range of age groups; no sex or race predilection has been noted. This lesion may present as a cystic lesion with benign clinical features or as a large tissue mass with ulceration, significant bone resorption, and tooth mobility. Perforation of the cortical plate, extension into surrounding soft tissue, and numerous recurrent lesions and metastasis, usually to cervical lymph nodes, can also be associated.[6] Both pathways, hematogenous as well as lymphatic, seem to be possible although the latter is rare. The most common site for a distant metastasis is the lung (70–85%), followed by bone, liver, and brain.[5,10,11] This high percentage emphasizes the importance to detect pulmonary metastases either by conventional radiographs, CT, or positron emission tomography scans as well as the need for long-term follow-up.[6,9,10] Distant metastasis can occur even in the absence of a local or regional recurrence.[3] Distant metastasis is usually fatal and may appear as early as 4 months or as late as 12 years postoperatively.[5] In the reviewed cases of maxillary AC,[9] 34.6% revealed metastases and 23.1% revealed local recurrences. In only one case, neck lymph nodes were involved. In 26.9% cases, pulmonary metastases occurred.

Carcinoma arising centrally within the mandible and the maxilla is an uncommon but complex problem. The first step in the staging process must be the exclusion of metastasis or invasion of bone by tumor from adjacent soft tissue or paranasal sinus. The neoplasm may be derived from a number of different sources, such as those of odontogenic origin, including ameloblastoma, odontogenic cysts or epithelial odontogenic rests, as well as entrapped salivary gland epithelium or epithelium entrapped along embryonic fusion sites.

Whether AC originates from an ameloblastoma or represents a separate entity is still controversially discussed. They may arise de novo or from a pre-existing odontogenic lesion.[6–9] The differential diagnosis of AC should include primary intra-alveolar epidermoid carcinoma, acanthomatous and keratinizing type of typical ameloblastoma, carcinomas in the jaws metastasizing from other locations, squamous cell carcinoma arising from odontogenic cyst, squamous odontogenic tumor, etc.

In cases where it originates from recurrent ameloblastoma, diagnosis may be simple because most lesions will have malignant transitional area coexisting with benign areas.

However, when it arises de novo, it has to be differentiated from other PIOC, central high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma or tumors with origin from bony invasion from adjacent tissue based on typical histologic features of ameloblastoma like peripheral palisading, reverse polarity, and stellate reticulum-like structures.[3,8]

The two types of typical ameloblastoma, acanthomatous ameloblastoma and kerato-ameloblastoma, must also be considered in the differential diagnosis of AC. The former one exhibits varying degrees of squamous metaplasia and even keratinization of the stellate reticulum portion of the tumor islands; however, peripheral palisading is maintained and no cytologic features of malignancy are found. The latter is a rare variant of ameloblastoma that contains prominent keratinizing cysts that raises a doubt and distracts the pathologist from the otherwise ameloblastomatous feature.[3,6,8]

Carcinomas in the jaws metastasizing from primary locations such as the lung, the breast and the gastrointestinal tract may mimic AC and must always be ruled out clinically by locating their primary site.[7–9]

An additional consideration in the differential diagnosis is the squamous cell carcinoma arising in the lining of an odontogenic cyst. The tumor cells resemble the cells seen in ameloblastoma but they show cytologic atypia and, moreover, they lack the characteristic arrangement seen in ameloblastoma.

Considering all the differential diagnosis, the term AC can be applied to our case, which showed focal histologic evidence of malignant disease including cytologic atypia and mitoses with indisputable features of classic ameloblastoma.

The treatment of AC is controversial, but the recommended surgical treatment usually requires jaw resection with 2- to 3-cm bony margins and consideration of contiguous neck dissection, both prophylactic and therapeutic. In cases with maxillary AC, a neck dissection should only be performed in the presence of clinically positive lymph nodes.[9] The characteristic histologic features and behavior of this tumor dictates more aggressive surgical approach than that of a simple ameloblastoma. It is well accepted that maxillary ameloblastomas should be treated as radically as possible due to the spongy maxillary bone architecture. This structure may facilitate the spread of the tumor and may lead to infiltration of adjacent vital structures. In contrast to this, the speed of growth in the mandible is decelerated due to the thick and compact bone structure.[9] A surgical resection with 10–15 mm margin free of tumor is recommended, even though the extent of the resection may have to be limited related to adjacent pivotal anatomical structures near the maxilla. However, at the same time especially in these kinds of locations, it is of utmost importance to be as radical as possible to control recurrence and potential degeneration into AC. Same ideology of being radical with conservation of important structures was used in our case.

Role of radiation therapy stands debatable but it is said that adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy improves the likelihood of local control, especially if margins are close or microscopically positive.[12] Regular follow-up and CT or magnetic resonance imaging controls, in particular in maxillary ameloblastomas, are broadly accepted for early detection of recurrence among clinicians. They can recur locally 0.5 to 11 years after definitive therapy.[5,11]

Reconstruction of the post-resection defect should be done in same way like any head or neck carcinoma resection. Sufficient time should be allotted before reconstruction because of potential tumor recurrence.

CONCLUSION

It is possible that ameloblastoma shows a variety of histologic and biologic behaviors ranging from benignity to frank malignancy. Cases of ameloblastoma should thus be studied carefully, correlating their histologic pattern with biologic behavior to detect subtle changes in histology that may predict aggressive behavior. For successful management of AC, a wide surgical resection with meticulous follow-up is essential because recurrence and metastasis in the lung and regional lymph nodes have been reported. Because of the rarity of these lesions, larger clinical series and longer periods of follow-up would help to establish the best therapeutic option for these tumors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2002. pp. 611–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mubeen K, Shakya HK, Jigna VR. Ameloblastic carcinoma of mandible.A Rare Case Report with Review of Literature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2010;2:e83–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arotiba JT, Mohammed AZ, Adebola RA, Adeola DS, Ajike SO, Rafindadi AH. Ameloblastic carcinoma: Report of a case. Niger J Surg Res. 2005;7:222–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward BB, Edlund S, Scuiba J, Helman JI. Ameloblastic carcinoma (primary type) of anterior maxilla: Case report with review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1800–3. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.06.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhir K, Sciubba J, Tufano RP. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:736–41. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slootweg PJ, Müller H. Malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:168–76. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elzay RP. Primary intraosseus carcinoma of the jaws: Review and update of odontogenic carcinomas. Oral Surg. 1982;54:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avon SL, McComb J, Clokie C. Ameloblastic Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:573–6a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruse AL, Zwahlen RA, Grätz KW. New classification of maxillary ameloblastic carcinoma based on an evidence-based literature review over the last 60 years. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:31. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson JM, Sonnet JR, Schlesinger C, Ord RA. Pulmonary metastasis of ameloblastoma: Case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:170–6. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce RA, Jackson IT. Ameloblastic carcinoma.Report of an aggressive case and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19:267–71. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillip M, Morris CG, Werning JW. Radiotherapy in treatment of ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma. J HK Coll Radiol. 2005;8:157–61. [Google Scholar]