Abstract

Mitochondria play an important role in sperm cell maturation and function. Here, we examined whether (and how) changes in sperm redox milieu affect the functional status of sperm mitochondria, that is, sperm functionality. Compared with the control, incubation in Tyrode's medium for 3 h, under noncapacitating conditions, decreased sperm motility, the amount of nitric oxide (•NO), the number of MitoTracker® Green FM (MT-G) positive mitochondria, and the expression of complexes I and IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. In turn, superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimic (M40403) treatment restored/increased these parameters, as well as the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, manganese SOD, and catalase. These data lead to the hypothesis that M40403 improves mitochondrial functional state and motility of spermatozoa, as well as •NO might be involved in the observed effects of the mimic. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 170–178.

Human Sperm Mitochondrial Function

In sperm cells, mitochondria play an important role in spermatogenesis, differentiation, acrosome reaction, oocyte fusion, and fertilization (5). It was firmly demonstrated recently that mitochondrial functionality is positively correlated with human sperm fertilization ability and quality (7). The major determinants of sperm mitochondrial functionality are the activity and expression of components of the electron transport chain (ETC), as well as mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (5). Thus, it is not surprising that any disruption of the mitochondrial ETC or MMP is associated with decreased sperm motility, reduced sperm fertilization potential, and, subsequently, male infertility (5).

Conversely, mitochondria represent major production sites and targets for reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively) (5). During the last decade, the multiple regulatory effects of nitric oxide (•NO) on mitochondrial function have become evident. The roles of ROS/RNS in reproduction have rapidly expanded with evidence accumulating which show that, in physiological concentrations, in particular, the superoxide anion radical (O2•−) and •NO seem to be crucial in regulating sperm capacitation and acrosome reactions, two processes required for sperm to acquire fertilizing ability (1). However, the molecular basis of ROS/RNS actions on sperm functionality, in particular their influence on the functional status of sperm mitochondria (MMP and expression of respiratory chain components), is still unknown.

Innovation.

Recent studies suggest the importance of reactive species and mitochondrial activity in the acquisition of sperm fertilizing potential; however, the underlying molecular mechanisms are still unknown. The current study showed, for the first time, that the superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimic, M40403, might improve a molecular basis of sperm mitochondrial function, as well as increase motility, and, thus, probably have positive effects on the functionality of spermatozoa. Significantly, we found that M40403 increases sperm nitric oxide (•NO) content, which implies •NO involvement in the observed effects of the drug. This leads to the hypothesis that the utilization of a redox modulator, M40403, is a promising pharmacological approach for the improvement of sperm function during assisted fertilization and for the treatment of infertile states accompanied by mitochondrial impairments and/or disturbed sperm redox state.

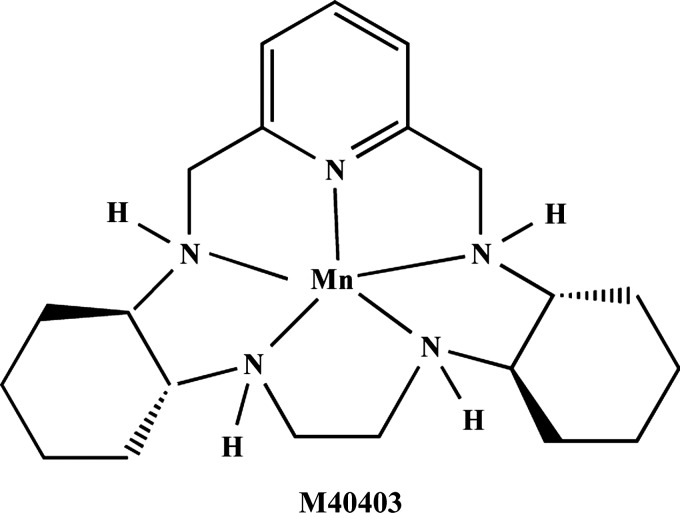

To examine the role of O2•− and •NO in reproduction, the use of compounds that modulate the activity of enzymes involved in their generation/removal have proved useful (1). However, the use of native enzymes in clinical trials is limited, and synthetic enzyme mimics have emerged as promising candidates. Mn II pentaazamacrocyclic complexes represent potent, low-molecular-mass mimics of superoxide dismutase (SOD) with marked protective effects in inflammation, stroke, atherosclerosis, and hypertension. A representative of this class of mimics—M40403 (Fig. 1) is selective for O2•−, lacks peroxidase/catalase activity, and does not react with •NO (4). Thus, we used M40403 in the present study to remove O2•− only; hence, M40403 can be used as a tool that increases the bioavailability of •NO through the scavenging of O2•−. Due to the important implications of redox status in male (in)fertility we aimed at examining the effects of M40403 on (i) •NO content within sperm cells; (ii) mitochondrial functional status, monitored using the cationic fluorescent probe MitoTracker® Green FM (MT-G) and expression of ETC components; (iii) sperm motility; and (iv) expression of sperm enzyme systems that produce/remove •NO, O2•−, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

FIG. 1.

Structure of M40403.

SOD Mimic and Human Sperm Mitochondrial Function

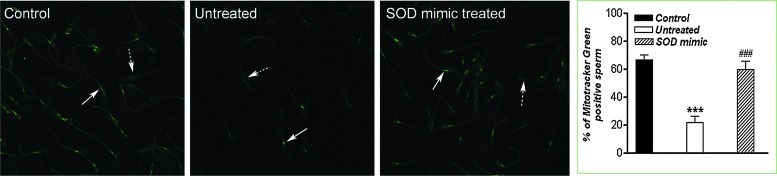

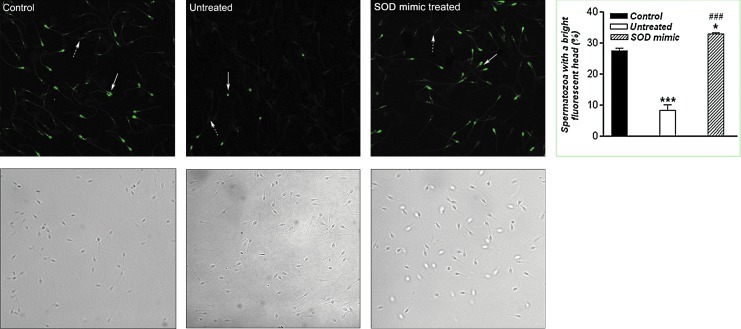

To assess the MMP of human sperm, the percentage of MT-G positive sperm was scored by counting 200 cells per coverslip in four different fields. The results of MT-G staining of sperm cells are shown in Figure 2. When compared with the control, the percentage of MT-G positive sperm decreased after 3 h of incubation in Tyrode's medium (p<0.001), while treatment with M40403 restored the population of MT-G positive sperm.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of MT-G-positive sperm cells. After the appropriate incubations, spermatozoa were loaded with MT-G (20 μM) in Tyrode's medium, incubated for 20 min, and evaluated by a dual-channel confocal microscope. MT-G-positive (arrow) and MT-G-negative (dotted arrow) spermatozoa were observed. The values represent the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) for five samples per group. For each sample, 200 cells were evaluated in three different fields, and representative staining was shown. Compared with the control, ***p<0.001; compared with the untreated group, ###p<0.001. Magnification: ×63, orig. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.) MT-G, MitoTracker Green FM.

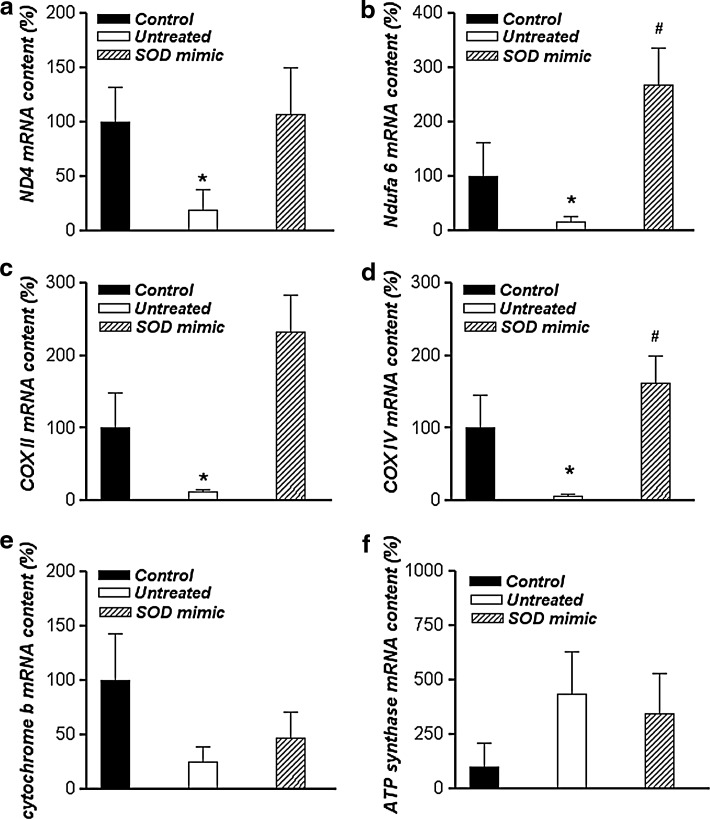

The changes in mRNA levels of ETC components in spermatozoa are presented in Figure 3. After incubation in Tyrode's medium for 3 h, mRNA levels of ND4 (Fig. 3a) and Ndufa6 (Fig. 3b), components of complex I and subunits II and IV of the cytochrome c oxidase complex (COX II and COX IV, respectively) (Fig. 3c, d), were significantly decreased compared with the control (p<0.05). Conversely, M40403 treatment significantly increased the gene expression of both Ndufa6 and COX IV (p<0.05) when compared with the untreated group. Transcript levels of cytochrome b (Fig. 3e) and ATP synthase (Fig. 3f) were unchanged.

FIG. 3.

Changes in mRNA level of respiratory chain components. Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression of ND4 and Ndufa6 components of electron transport chain complex I (a and b, respectively) and subunits II and IV of COX (c and d, respectively) cytochrome b (e) and ATP synthase (f) in sperm cells. Results are given as mean±SEM for all genes normalized to GAPDH transcription (n=30, 10 per group). Compared with the control, *p<0.05; Compared with the untreated group, #p<0.05. COX, cytochrome c oxidase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

The percentage of motile sperm cells followed the same pattern of change as the percentage of MT-G positive spermatozoa (Table 1): Incubation in Tyrode's medium for 3 h significantly decreased the percentage of motile sperm when compared with the control (p<0.001), while in the M40403-treated group, this percentage returned to the control level.

Table 1.

Sperm Motility

| Control group | Untreated group | SOD mimic-treated group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of motile spermatozoa (mean±SEM) | 90±4.2 | 68±3.8a | 83±4.5b |

Comparison with the control group, p<0.001.

Comparison with the untreated group, p<0.001.

SOD, superoxide dismutase; SEM, standard error of the mean.

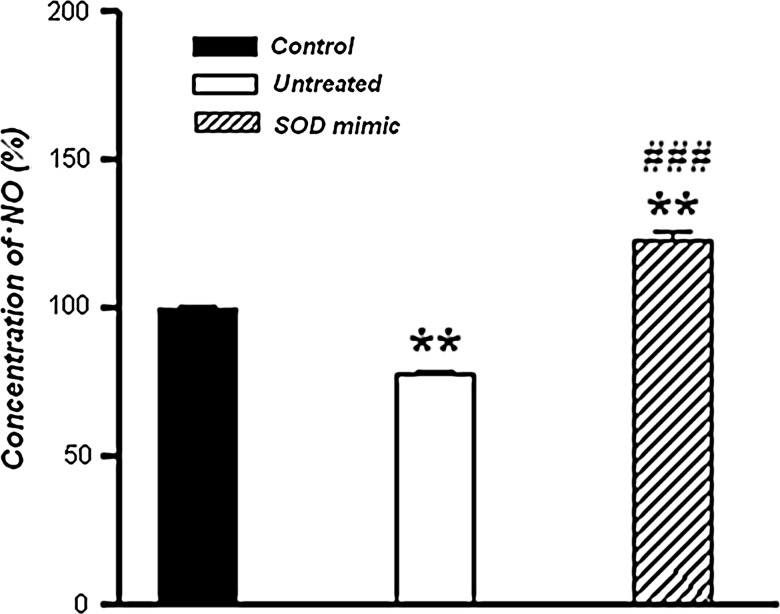

M40403 and Level of •NO in Sperm Cells

The level of •NO, measured using an amperometric sensor, after incubation in Tyrode's medium for 3 h was significantly decreased (p<0.01) in sperm cells when compared with the control (Fig. 4). However, in the M40403-treated group, the concentration of •NO was higher than in the control (p<0.01) and the untreated group (p<0.001).

FIG. 4.

Detection of •NO. Concentration of •NO in sperm cells incubated in Tyrode's medium supplemented or not with 50 μM M40403 SOD mimic, evaluated immediately or after 3 h of incubation. •NO content was assessed electrochemically, by the inNO-II •NO measurement system, using the amino-700 sensor electrode. Relative •NO concentrations are presented as percentages of the control, which was taken as 100%. Data represent the mean±SEM (n=30, 10 per group). Compared with the control, **p<0.01; compared with the untreated group, ###p<0.001. SOD, superoxide dismutase; •NO, nitric oxide.

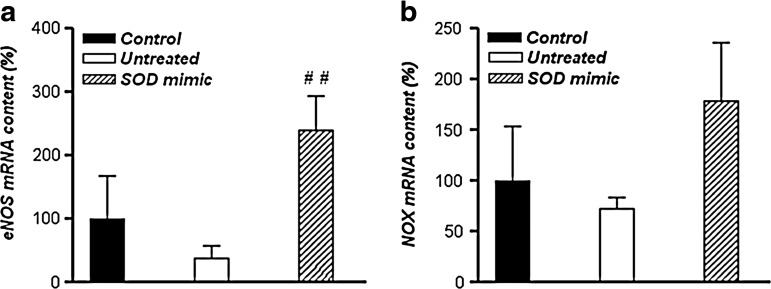

The localization and production of •NO, assessed by diamino-fluorescein-2-diacetate (Daf2-DA), is shown in Figure 5. •NO-specific fluorescence was not only located in sperm mitochondria, but also in the head and flagellum. Analogous to the amperometric measurements, incubation in Tyrode's medium for 3 h significantly decreased (p<0.001) the percentage of spermatozoa with a bright head (stained positively for •NO), as compared with those with a pale head. However, the percentage of spermatozoa with bright heads (stained positively for •NO) increased after the incubation of sperm cells in Tyrode's medium supplemented with 50 μM M40403 for 3 h (p<0.05, when compared with the control and p<0.001 when compared with the untreated sample).

FIG. 5.

Localization and measurement of •NO in spermatozoa. At the end of appropriate incubations, spermatozoa were loaded with diamino-fluorescein-2-diacetate (10 μM) in Tyrode's medium and evaluated by a dual-channel confocal microscope. The upper frame shows the fluorescence image, and the lower frame shows the same field viewed by phase contrast. The proportions of spermatozoa with a bright head (arrow), as compared with those with a pale head (dotted arrow) was evaluated. The results of a representative experiment are shown. The values represent the mean±SEM for five samples per group. For each sample, 200 cells were evaluated in three different fields, and representative staining was shown. Compared with the control, *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; compared with the untreated group, ###p<0.001. Magnification: ×63, orig. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars.)

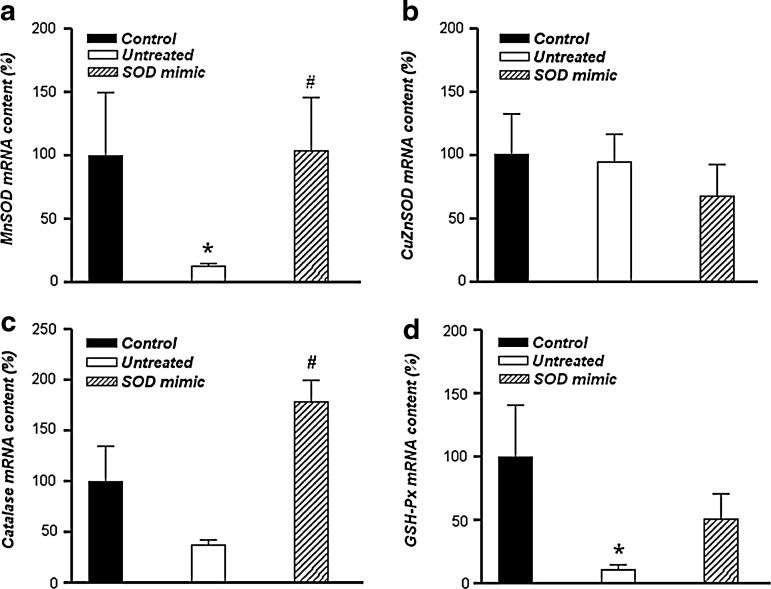

The incubation of spermatozoa in Tyrode's medium did not influence mRNA levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (Fig. 6a) or NADPH oxidase (NOX) (Fig. 6b) when compared with the control. However, M40403 significantly increased the mRNA level of eNOS compared with the untreated group (p<0.01). On the other hand, incubation in Tyrode's medium, with or without added mimic, did not influence the expression of the neuronal isoform of NOS in sperm cells (results not shown), while the gene expression of inducible NOS in the samples was not detected.

FIG. 6.

Gene expression of eNOS and NOX. Changes in eNOS (a) and NOX (b) transcript levels in spermatozoa incubated in Tyrode's medium supplemented or not with 50 μM M40403 SOD mimic, evaluated immediately or after 3 h of incubation. Results are given as mean±SEM for all genes normalized to GAPDH transcription (n=30, 10 per group). Compared with the untreated group, ##p<0.01. NOX, NADPH oxidase.

Antioxidative Defense of M40403-Treated Samples

Gene expression of manganese SOD (MnSOD) (Fig. 7a) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) (Fig. 7d) in the untreated group was lower than in the control (p<0.05), while the expression of catalase and copper, zinc SOD (CuZnSOD) (Fig. 7b, c) was unchanged. Treatment with M40403 SOD mimic, however, increased the mRNA levels of MnSOD and catalase, compared with the untreated group (p<0.05), but did not have an impact on the mRNA content of CuZnSOD or GSH-Px. Immunocytochemistry analyses confirmed the presence of these enzymes in spermatozoa (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Changes in mRNA levels of enzymes involved in antioxidative defense. mRNA expression of MnSOD (a), CuZnSOD (b), catalase (c), and GSH-Px (d) in sperm cells incubated in Tyrode's medium supplemented or not with 50 μM M40403 SOD mimic, evaluated immediately or after 3 h of incubation. Results are given as mean±SEM for all genes normalized to GAPDH transcription (n=30, 10 per group). Compared with the control, *p<0.05; compared with the untreated group, #p<0.05. MnSOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; CuZnSOD, copper, zinc SOD; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase.

Open Questions

The present study demonstrates that the incubation of human spermatozoa in Tyrode's medium for 3 h, under noncapacitating conditions, decreased the amount of sperm •NO, sperm motility, percentage of MT-G-positive mitochondria, expression of ETC components—complex I and IV, and spermatozoa antioxidative defense—MnSOD and GSH-Px. The most important finding in this work was that the administration of M40403 SOD mimic for 3 h increased •NO amount, restored sperm motility, and the population of MT-G-positive mitochondria, as well as the expression of complex I and IV of mitochondrial ETC within sperm cells. These effects were accompanied by the up-regulation of mRNA expression of eNOS, MnSOD, and catalase.

It is known that sperm samples with a higher percentage of active mitochondria have higher fertilization potential and that the determination of mitochondrial activity by MT-G staining might be a good method for selection of the most potent/functional spermatozoa in assisted fertilization (7). These data along with the observed results of sperm MT-G staining lead to the hypothesis that M40403 SOD mimic could improve the functional status of sperm mitochondria and, subsequently, sperm quality. In line with this is M40403-stimulated increase of mRNA expression of the nucleus encoded subunits of both ETC components—complex I and IV, in relation to the untreated group. Considering that the expression of mitochondrial ETC proteins is related to metabolic rate and sperm quality, the physiological significance of this finding rests in the suggestion that M40403 might increase the mitochondrial energy producing potential. Besides, the data indicate that changes in spermatozoa redox state, after treatment with the SOD mimic, may affect the transcription of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins. In addition, in accordance with the hypothesized improvement in the functional status of sperm mitochondria and so, the fertilizing ability of spermatozoa by M40403 is, here detected in an increase in sperm motility, which is a crucial parameter of semen fertility (9).

Although the precise mechanism of this SOD mimic-acting remains to be elucidated, an interesting finding in this study was the increase in the •NO level in spermatozoa caused by M40403. This finding implies the involvement of •NO in the observed effects of the drug. It is well-known that •NO and its precursors increase the motility of spermatozoa by increasing energy production originating in the mitochondrial compartment (8) and that •NO regulates various mitochondrial functions (1). Thus, in future studies, designed to define the precise mechanism behind the increase in the population of MT-G-positive sperm cells and motile spermatozoa, potential •NO involvement warrants further consideration.

•NO and O2•− play decisive roles in regulating multiple functions within the male reproductive system either separately or through mutual interactions (1). •NO rapidly reacts with O2•−, with a three-fold higher rate constant than that of the dismutation reaction catalyzed by SOD (2). Thus, an increased level of •NO in mimic-treated sperm cells may be due to the decreased bioavailability of O2•− by the action of M40403. However, the increased amount of •NO in the M40403-treated group was accompanied by an increased expression of eNOS mRNA. Therefore, the increase in •NO bioavailability after M40403 treatment may also depend, at least partly, on the drug-elicited induction of eNOS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the stimulatory effect of this class of SOD mimics on both •NO content and eNOS gene expression has been reported in sperm cells in vivo. Although many questions regarding the mechanisms of SOD mimic acting remain open, the data allow us to hypothesize that M40403 could be used as a molecular tool which manipulates the sperm-redox state, by removing O2•− and stimulating •NO production.

Modulation of the spermatozoa redox environment by the SOD mimic was further demonstrated here by the increase in catalase and MnSOD mRNA levels, compared with the untreated group. These data addressed, for the first time, the effect of M40403 SOD mimic on sperm antioxidative enzyme gene expression. The observed increase in catalase mRNA expression seems quite understandable and could be considered as the adaptive phenotype of the enzyme directed to accommodate elevated H2O2 production, due to the SOD mimic. On the other hand, the induction of gene expression of the mitochondrial-specific O2•− removing enzyme by M40403 raised a new hypothesis that some necessity of maintaining an optimal level of endogenous MnSOD in sperm mitochondria exists. Despite the fact that all SOD isoenzymes catalyze the same reaction, the function of isoforms in cell physiology is different, and often one SOD cannot compensate for another, suggesting that the subcellular location of SOD is crucial in the physiological functions of these enzymes. In line with this was the unchanged transcript level of CuZnSOD after M40403 treatment observed in the present study. Concepts that developed from the current study include the presence of co-ordinated regulation of mRNA expression of MnSOD and catalase by M40403, and the determination of the mechanism of this class of SOD mimic on spermatozoa antioxidative defense expression require additional studies. Further research along these lines is now in progress.

Results from the present study shed new light on this class of SOD mimic, which affects sperm mitochondrial functional state and motility, and, thus, the functionality of spermatozoa led to the hypothesis that M40403 could be considered a promising pharmacological tool for the improvement of sperm function during assisted fertilization and for the treatment of infertile states accompanied by mitochondrial impairments and/or disturbed sperm-redox state. These results contribute to the knowledge of redox processes in reproductive biology and could assist in the development of new pharmacological strategies that treat infertility, by selective production/removal of certain reactive species, using novel redox modulators.

Notes

M40403 synthesis

The synthesis and purification of M40403 were carried out following a previously published procedure (6).

Sperm preparations and treatments

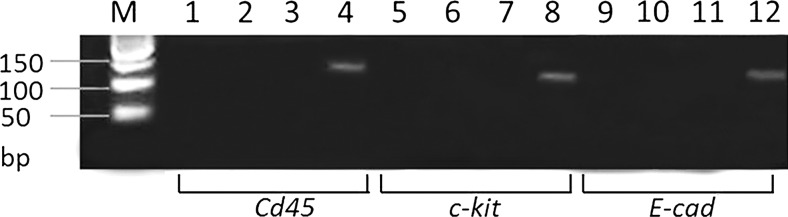

The ethics committee of the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics “Narodni Front” and of the Institute for Biological Research at the University of Belgrade approved the study. Thirty patients, who had signed an informed consent, were recruited from couples applying for reproductive technology procedures at the Artificial Reproductive Technology Department of the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics “Narodni front,” Belgrade, Serbia. Characteristics of native semen samples are summarized in Table 2. Of these couples, women suffered from infertility, while the male semen samples were classified as normospermic, according to criteria established by the World Health Organization. Semen samples were obtained after 3–5 days of abstinence. To eliminate debris such as nonsperm cells and dead spermatozoa, the samples were purified by centrifugation using Cook density gradients (40% and 80%) (Cook® Medical, Inc.). After centrifugation, the upper and interface layers containing the dead cells and other somatic contaminants were aspirated off, leaving the sperm enriched fraction (80% gradient layer). All 80% gradient layer fractions were then washed in 5 ml of modified Tyrode's medium (consisting of 117.5 mM NaCl, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4, 8.6 mM KCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM glucose, 0.25 mM Na pyruvate, and 19 mM Na lactate) devoid of bovine serum albumin, centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min, and divided into three groups consisting of 10 patients. The pellets (spermatozoa) were than collected, resuspended to a final concentration of 40×106 cells/ml in the required volume of modified Tyrode's medium, and supplemented or not with 50 μM M40403. One group was evaluated immediately after resuspension in Tyrode's medium and served as the control. For the other two groups (untreated and SOD mimic treated group, respectively) the spermatozoa were resuspended in Tyrode's medium supplemented or not with 50 μM M40403 SOD mimic and evaluated after incubation in an atmosphere of 6% CO2 for 3 h at 37°C. The dose of M40403 has been used, according to Salvemini et al. (6). In addition, we examined the potent toxicity and optimal dose of the complex by incubating spermatozoa with 25, 50, or 100 μM M40403, for 3 h. The dose of 50 μM was clearly nontoxic to cells, based on unchanged sperm viability, number, and morphology after treatment. Before sample processing, sperm purity was confirmed using bright phase microscopy and by the absence of mRNA amplification in testicular germ cells, endothelial cells, or leukocytes (Fig. 8).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Native (Before Processing by Density Gradient) Semen Samples

| Parameters | Average (of 30 samples) | Min/max | Normal values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of donors (years) | 35 | 30/37 | |

| Volume of semen (ml) | 3.0 | 2.2/3.4 | >2 |

| Semen pH | 7.5 | 7.2/7.9 | 7.2–8.0 |

| Sperm concentration (106/ml) | 61.3 | 30/83 | ≥20 |

| Motility (%) | 72 | 68/98 | ≥50 |

| Normal morphology (%) | 46.1 | 50/72 | ≥30 |

| Number of leukocytes | 0.5 | 0/3 | <6 |

| Number of erythrocytes | (−) absent | (−) absent | (−) absent |

FIG. 8.

Purity of mRNA samples. Agarose gel showing the PCR product for specific markers of leukocytes (CD45), germ cells (c-kit), and epithelial cells (E-cad) used as positive controls in lines 4, 8, and 12, respectively. Each sperm sample from all examined groups was examined for the presence of CD45, c-kit, and E-cad. PCR products of all samples per each group are coupled and loaded onto lines: 1, 5, 9—control group; 2, 6, 10—untreated group; 3, 7, 11—SOD mimic-treated group; Each of the examined samples showed the absence of RNA from contaminating cells (lines 1–4, CD45; 5–8, c-kit; 9–12, E-cad). Monocytes and endometrial epithelial cells were used as positive markers of CD45 and E-cad, respectively. Human semen samples contaminated by testicular germ cells were used as positive controls for the c-kit.

At the end of the incubation, spermatozoa were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min. The pellets from all 30 patients (n=10 per group) were used to measure •NO and mRNA contents. For Daf2-DA and MT-G staining, five sperm aliquots per group were used. Depending on the experiment, sperm pellet aliquots were diluted differently. All steps in each experiment are explained in greater detail in the appropriate section next.

Motility assessment

Sperm motility was determined by assessing at least 400 sperms in each semen sample. Each spermatozoon was categorized as belonging to one of the three motility categories (progressive, nonprogressive, and immotile), using techniques for assessment and quality control according to the World Health Organization. For comparisons in this study, the percentages of motile sperm (the sum of the two categories of motile sperm) were used.

Measurement of •NO

•NO production in the sperm suspension of 40×106 cells/ml was measured in real-time, electrochemically, by the inNO-II nitric oxide measurement system, using the amino-700 sensor electrode (Innovative Instruments) (n=30, 10 per group). The sensor was calibrated by the conversion of nitrite to •NO in an acidic solution containing potassium iodide, as suggested by the manufacturer (Innovative Instruments). The sensor was polarized in an aqueous solution for a minimum of 12 h before calibration or implantation in the sperm suspension.

Daf 2-DA staining for detection of •NO

After washing and centrifugation at 2000 g for 10 min, spermatozoa (n=5 per group) were resuspended at a concentration of 10×106 cells/ml in Tyrode's medium. Daf 2-DA was added to the suspension for a final concentration of 10 μM and incubated in an atmosphere of 6% CO2 at 37°C for 30 min as described by de Lamirande et al. (1). The sperm cells were then mounted with Mowiol® 4-88 (Polysciences Europe GmbH) as an anti-fading agent, and observed under a Carl Zeiss LSM510 confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). Overall, 200–300 cells were evaluated for each sample in this experiment.

MT-G staining

Mitochondrial function was monitored using MT-G (Molecular Probes, Inc.), the cationic fluorescent probe, which accumulates in mitochondria depending on the transmembrane electrochemical gradient, according to Sousa et al. (7). These authors showed that (i) this probe stains human sperm mitochondria according to MMP; (ii) all sperm samples exhibit two subpopulations: MT-G positive and MT-G negative; and (iii) MT-G staining is negligible. For this examination, five samples per group were used, and the pellet was resuspended at 20×106 cells/ml in Tyrode's medium containing 20 nM MT-G and incubated at 37°C for 20 min in an atmosphere containing 6% CO2, as previously described (7). After incubation, sperm cells were mounted with Mowiol® 4-88 (Polysciences Europe GmbH) as an anti-fading agent, and observed under a Carl Zeiss LSM510 confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). The percentage of stained sperm cells was determined by counting 200 cells per coverslip in four different fields, and representative staining is shown.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

For the analysis of mRNA expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain components and antioxidative defense enzymes, sperm aliquots (200 μL) containing 20×106 cells/ml from all 30 patients (n=10 per group) were incubated. After incubation and centrifugation at 2000 g for 10 min, the cells were resuspended in 1 ml TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). The extraction of RNA was carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Then, one microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using an iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio Rad Laboratories). Real-time PCR was preformed using SYBR Green technology on the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The sequences and cycle protocols of the used primers (Metabion International AG) are listed in Table 3. The reaction optimization and content of the mastermix has been previously described (3). Results were normalized to the expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), to compensate for variations in input RNA amount and the efficiency of reverse transcription. The amplified sperm mRNA was not contaminated with mRNA from testicular germ cells, endothelial cells, or leukocytes as primers to c-kit (germ cells), E-cadherin (epithelial cells), and CD45 (leukocytes) did not amplify these transcripts in isolated sperm mRNA (Fig. 8).

Table 3.

Primer Sequences and Cycling Conditions

| Gene | Sequence | Cycle number |

|---|---|---|

| ND4 | ||

| Forward | 5′-ACA AGC TCC ATC TGC CTA CGA CAA-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTA TGA GAA TGA CTG CGC CGG TGA-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 58°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| Ndufa 6 | ||

| Forward | 5′-CAA GAT GGC GGG GAG CGG-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GTA TAG TGA GTT TAT TTG TGC TC-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 59°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| COX II | ||

| Forward | 5′-TGC CCT TTT CCT AAC ACT CAC AA-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CGC CGT AGT CGG TGT ACT CG-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 59°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| COX IV | ||

| Forward | 5′-AGG TGG CCC ATG TCA AGC AC-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CAT GAT AAC GAG CGC GGT GA-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 59°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| Cytochrome b | ||

| Forward | 5′-TCC TCC CGT GAG GCC AAA TAT CAT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-AAA GAA TCG TGT GAG GGT GGG ACT-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 59°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| ATP synthase | ||

| Forward | 5′-AGC TCA GCT CTT ACT GCG G-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GGT GGT AGT CCC TCA TCA AAC T-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 56°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| Catalase | ||

| Forward | 5′-CTC GTG GGT TTG CAG TGA AAT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-TCA GGA CGT AGG CTC CAG AAG-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 56°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| GSH-Px | ||

| Forward | 5′-CCA GTC GGT GTA TGC CTT CTC-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GAG GGA CGC CAC ATT CTC G-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 56°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| MnSOD | ||

| Forward | 5′-CCT CAC ATC AAC GCG CAG AT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CGT TCA GGT TGT TCA CGT AGG-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 56°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| CuZnSOD | ||

| Forward | 5′-AGG GCA TCA TCA ATT TCG AGC-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GCC CAC CGT GTT TTC TGG A-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 56°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| NOX-4 | ||

| Forward | 5′-CTC AGC GGA ATC AAT CAG CTG TG-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-AGA GGA ACA CGA CAA TCA GCC TTA G-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 58°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| eNOS | ||

| Forward | 5′-TTG GCG GCG GAA GAG GAA GGA GT-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CAA AGG CGC AGA AGT GGG GGT ATG-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 59°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| iNOS | ||

| Forward | 5′-ACG TGC GTT ACT CCA CCA ACA A-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5’-CAT AGC GGA TGA GCT GAG CAT T-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 45″ at 58°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| nNOS | ||

| Forward | 5′-TTG GGG GCC TGG GAT TTC TGG-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-CGT TGG CAT GGG GGA GTG AGC-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 45″ at 55°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

| GAPDH | ||

| Forward | 5′-CCA GTG CAA AGA GCC CAA AC-3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′-GCA CGG ACA CTC ACA ATG TTC-3′ | 40 |

| Cycle protocol | 15″ at 95°C, 15″ at 58°C, 30″ at 72°C | |

MnSOD, manganese superoxide dismutase; COX, cytochrome c oxidase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NOX, NADPH oxidase.

Statistics

Analysis of variance was used for within-group comparisons. If the F test showed an overall difference, Tukey's test was applied to evaluate the significance of the differences. Statistical significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Abbreviations Used

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- CuZnSOD

copper, zinc SOD

- Daf2-DA

diamino-fluorescein-2-diacetate

- ETC

electron transport chain

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSH-Px

glutathione peroxidase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- MT-G

MitoTracker Green FM

- •NO

nitric oxide

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- O2•−

superoxide anion radical

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia, Grant no. 173054. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article. M.R.F. and I.I.-B. acknowledge support from an intramural grant (Emerging Field Initiative-Medicinal Redox Inorganic Chemistry) at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

References

- 1.de Lamirande E. Lamothe G. Villemure M. Control of superoxide and nitric oxide formation during human sperm capacitation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1420–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huie RE. Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jovic M. Stancic A. Nenadic D. Cekic O. Nezic D. Milojevic P. Micovic P. Buzadzic B. Korac A. Otasevic V. Jankovic A. Vucetic M. Velickovic K. Golic I. Korac B. Mitochondrial molecular basis of sevoflurane and propofol cardioprotection in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement with cardiopulmonary bypass. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29:131–142. doi: 10.1159/000337594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muscoli C. Cuzzocrea S. Riley DP. Zweier JL. Thiemermann C. Wang ZQ. Salvemini D. On the selectivity of superoxide dismutase mimetics and its importance in pharmacological studies. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:445–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramalho-Santos J. Varum S. Amaral S. Mota PC. Sousa AP. Amaral A. Mitochondrial functionality in reproduction: from gonads and gametes to embryos and embryonic stem cells. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:553–572. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvemini D. Wang ZQ. Zweier JL. Samouilov A. Macarthur H. Misko TP. Currie MG. Cuzzocrea S. Sikorski JA. Riley DP. A nonpeptidyl mimic of superoxide dismutase with therapeutic activity in rats. Science. 1999;286:304–230. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sousa AP. Amaral A. Baptista M. Tavares R. Caballero Campo P. Caballero Peregrín P. Freitas A. Paiva A. Almeida-Santos T. Ramalho-Santos J. Not all sperm are equal: functional mitochondria characterize a subpopulation of human sperm with better fertilization potential. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanislavov R. Nikolova V. Rohdewald P. Improvement of seminal parameters with Prelox: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Phytother Res. 2009;23:297–302. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang MJ. Ou JX. Chen GW. Wu JP. Shi HJ. O WS. Martin-Deleon PA. Chen H. Does prohibitin expression regulate sperm mitochondrial membrane potential, sperm motility, and male fertility? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:513–519. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]