A gradient of PI(4,5)P2 formed by phospholipid synthesis, diffusion, and regulated turnover is crucial for filamentous growth.

Abstract

Membrane lipids have been implicated in many critical cellular processes, yet little is known about the role of asymmetric lipid distribution in cell morphogenesis. The phosphoinositide bis-phosphate PI(4,5)P2 is essential for polarized growth in a range of organisms. Although an asymmetric distribution of this phospholipid has been observed in some cells, long-range gradients of PI(4,5)P2 have not been observed. Here, we show that in the human pathogenic fungus Candida albicans a steep, long-range gradient of PI(4,5)P2 occurs concomitant with emergence of the hyphal filament. Both sufficient PI(4)P synthesis and the actin cytoskeleton are necessary for this steep PI(4,5)P2 gradient. In contrast, neither microtubules nor asymmetrically localized mRNAs are critical. Our results indicate that a gradient of PI(4,5)P2, crucial for filamentous growth, is generated and maintained by the filament tip–localized PI(4)P-5-kinase Mss4 and clearing of this lipid at the back of the cell. Furthermore, we propose that slow membrane diffusion of PI(4,5)P2 contributes to the maintenance of such a gradient.

Introduction

The phosphoinositide bis-phosphate PI(4,5)P2 is a minor constituent of cellular membranes that is essential for polarized growth, and in particular, membrane traffic and actin cytoskeleton organization in a range of organisms (Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006; Strahl and Thorner, 2007; Vicinanza et al., 2008; van den Bout and Divecha, 2009; Kwiatkowska, 2010; Saarikangas et al., 2010). An asymmetric distribution of PI(4,5)P2 has been observed in several organisms (Kost et al., 1999; El Sayegh et al., 2007; Martin-Belmonte et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2008; Fooksman et al., 2009; Fabian et al., 2010; Garrenton et al., 2010); however, its requirements and roles are unclear. Furthermore, these asymmetries have been, in general, restricted to specific locations and gradients of PI(4,5)P2 over long distances have not been observed. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mss4p is the sole PI(4)P-5-kinase that generates PI(4,5)P2 and is localized to the plasma membrane (PM; Desrivières et al., 1998; Homma et al., 1998). Mss4p and the phosphoinositide-4-kinase Stt4p, which generates PI(4)P at the PM, are essential for viability (Cutler et al., 1997; Desrivières et al., 1998; Homma et al., 1998; Trotter et al., 1998) and are involved in a number of fundamental processes including cell polarity and membrane traffic (Strahl and Thorner, 2007; Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009b).

In diverse fungi including pathogenic species, a morphological transition that is important for virulence can be triggered by numerous external stimuli (Madhani and Fink, 1998; Lengeler et al., 2000; Rooney and Klein, 2002; Biswas et al., 2007; Whiteway and Bachewich, 2007). Although many proteins have been shown to localize to the tip of the protruding filament in the human pathogen Candida albicans (Hazan and Liu, 2002; Zheng et al., 2003; Bassilana et al., 2005; Crampin et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005, 2007; Bishop et al., 2010; Jones and Sudbery, 2010), the role and distribution of lipids in this morphological transition is largely unknown. Previously, it has been shown that C. albicans cell extract PI(4)P-5-kinase activity peaks just before filamentation during the yeast-to-filamentous growth transition (Hairfield et al., 2002), suggesting that PI(4,5)P2 may be critical for this transition.

To examine the roles and distribution of PI(4,5)P2 in the human pathogenic fungi C. albicans, we generated strains in which the expression of either Stt4 or Mss4 could be repressed, as well as a reporter that enabled the quantitative analyses of in vivo PI(4,5)P2 distribution during morphogenesis. In this study we show that cells lacking an asymmetric distribution of PI(4,5)P2 are defective in cell morphogenesis. Our results show that the initiation and maintenance of a PM lipid gradient is critical for cell shape changes of this important human pathogen.

Results

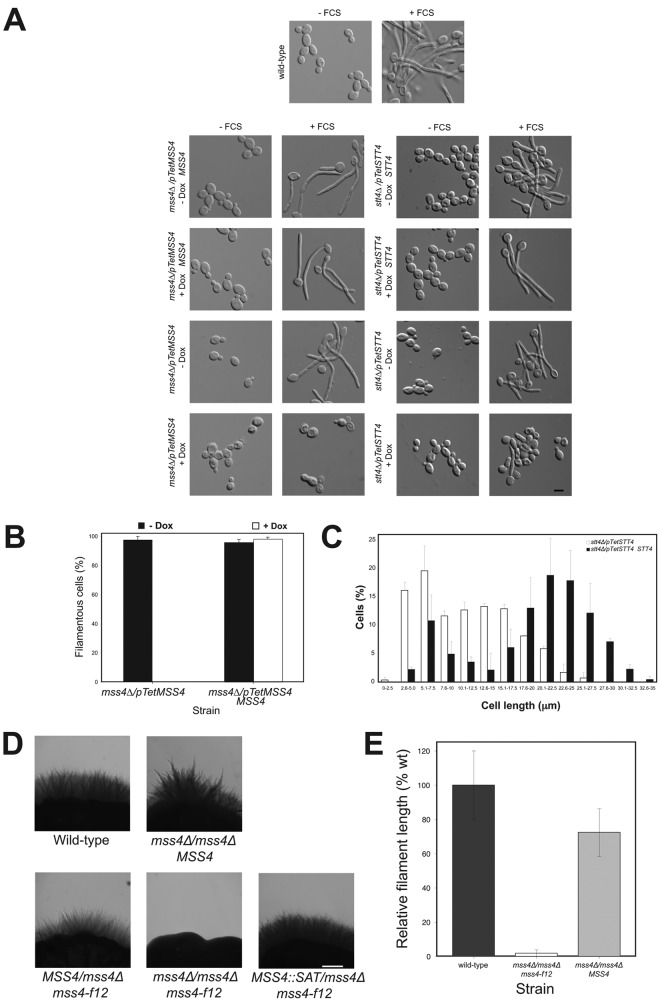

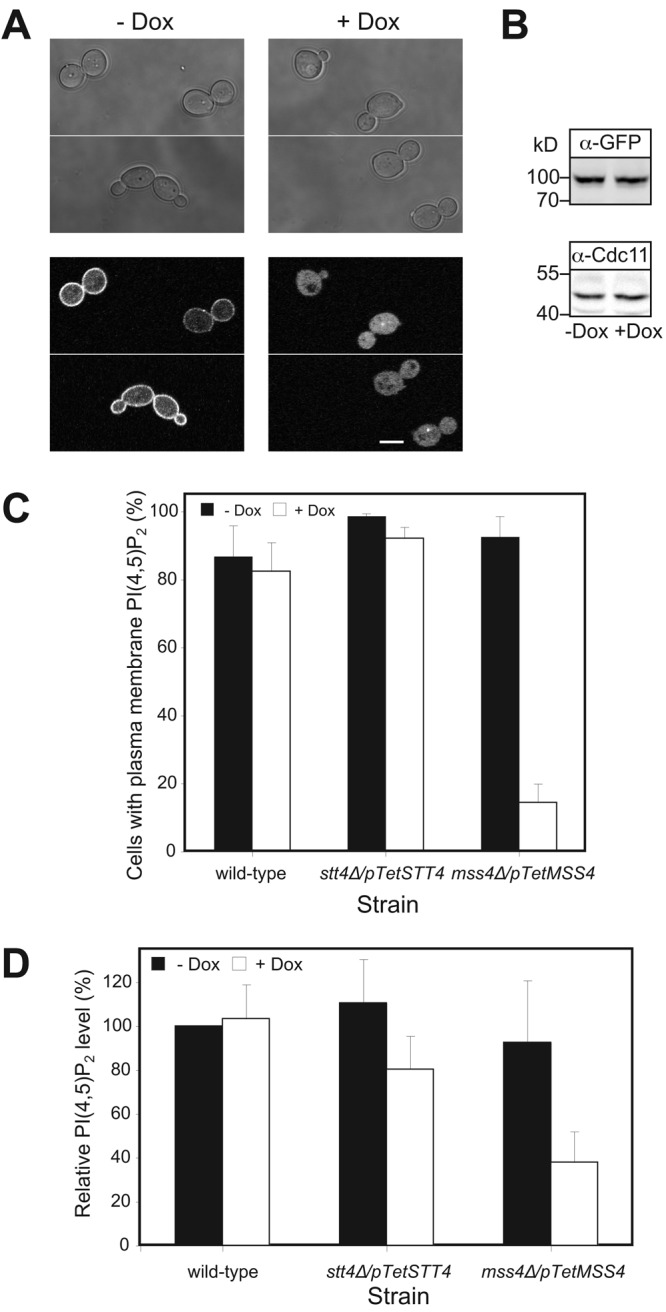

Phosphoinositide phosphates are critical for invasive filamentous growth

Strains in which one copy of either STT4 or MSS4 was deleted and the remaining copy was placed behind the Tet promoter were constructed and verified by PCR (Fig. S1, A and B; and not depicted). In the absence of the repressor doxycycline (Dox), these strains had increased levels of the respective lipid kinase mRNA (Fig. S1 C; four- to eightfold higher levels compared with a wild-type [wt] strain). In the presence of Dox, STT4 and MSS4 transcript levels were reduced 16-fold and fivefold in the stt4Δ/pTetSTT4 and mss4Δ/pTetMSS4 strains (hereafter referred to as stt4 and mss4), respectively, compared with a wt strain. Both stt4 and mss4 strains appeared to grow with a normal morphology irrespective of whether kinase expression was repressed (Fig. 1 A and Fig. S1 D), yet grew somewhat slower than the wt or control strains (reintroduction of respective gene) upon kinase repression (doubling times were 20% slower for stt4 strain and 50% slower for the mss4 strain). In the presence of FCS, however, we observed a striking filamentous growth defect (Fig. 1 A) when either kinase was repressed. This defect was complemented by the reintroduction of a STT4 or MSS4 copy, respectively. Essentially no filamentous cells were detected in the repressed mss4 strain, yet some elongated cells were observed with the stt4 strain in identical conditions (Fig. 1, A and C; and Fig. S1 E), corresponding to short protrusions, roughly the length of the cell body (∼5–7 µm vs. 15–20 µm for the wt). Similarly, in repressed conditions the mss4 strain was completely defective in invasive growth in FCS and agar-containing media, whereas the stt4 strain exhibited a reduced number of shorter invasive filaments (Fig. S1 F). Consistent with these results, we have recently isolated a specific mss4 mutant allele (mss4-f12) in S. cerevisiae, which is defective in haploid invasive growth (unpublished data) and hence we generated a C. albicans strain in which the sole MSS4 copy carried a mutation analogous to this allele, the Ser residue at position 514 was changed to a Pro. This C. albicans mutant (mss4Δ/mss4Δ mss4-f12) was completely defective in invasive growth in FCS and agar-containing media, and reintroduction of a MSS4 copy complemented this defect (Fig. 1, D and E); however, a clear filamentous growth defect in liquid media was not observed. The phenotype of these two C. albicans mss4 mutants is further consistent with the invasive filamentous growth defect of an INP51 (encoding a PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase) mutant, which has perturbed PI(4,5)P2 levels (Badrane et al., 2008). Together our results show that both Stt4 and Mss4 are necessary for filamentous growth.

Figure 1.

Stt4 and Mss4 are required for filamentous growth. (A) Mss4 and Stt4 are necessary for hyphal growth. Indicated strains were incubated in the presence (120 min) and absence of FCS with and without Dox (ni.ex. = 5). (B) Quantification of hyphal growth defects. Cells were incubated with FCS as above and the percentage of filamentous cells determined (5 times 50 cells). (C) The stt4 mutant elongates, yet is unable to form hyphae. Cells were incubated with FCS as above and lengths determined (ni.ex. = 2; 125 cells each). (D) An mss4 mutant specifically defective in invasive filamentous growth. Indicated strains were incubated on FCS containing agar at 30°C for 8 d (ni.ex. = 3). (E) Quantitation of colony filament length in mss4-f12 mutant cells. Filament length was determined (ni.ex. = 3) and averages shown (wt: 100% = 1.1 mm).

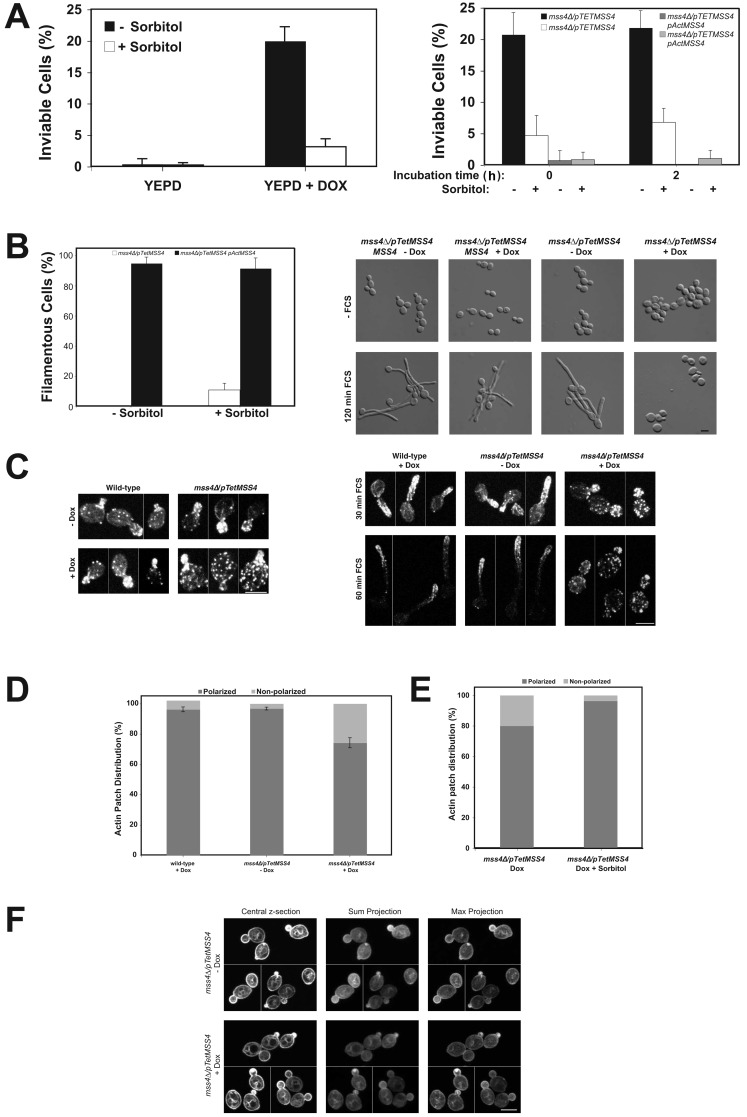

The mss4 filamentous growth defect is not due to perturbation of the actin cytoskeleton or Cdc42 localization

In S. cerevisiae, stt4 and mss4 temperature-sensitive (ts) mutants display abnormal cell morphologies, increased size, and randomly distributed cortical actin patches at the nonpermissive temperature (Desrivières et al., 1998; Homma et al., 1998). Furthermore, PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2 are important for cell wall integrity in this yeast (Yoshida et al., 1994; Cutler et al., 1997; Audhya et al., 2000). Closer inspection of the repressed C. albicans mss4 strain revealed cells with an enlarged and/or aberrant appearance (Fig. 1 A). In this condition, ∼20% of cells were inviable in the presence or absence of FCS (Fig. 2 A), with substantially less inviable stt4 cells (2% ± 2% in the absence of Dox and 8% ± 4% in its presence). In addition, there was an increased number of actin patches in the enlarged mss4 mother cells in both conditions (Fig. 2 C), with an eightfold increase in cells with a nonpolarized actin patch distribution (Fig. 2 D). In contrast, we did not observe any perturbation of the actin cytoskeleton in stt4 cells in the same condition (not depicted). S. cerevisiae stt4ts mutants can be rescued by osmotic support (Yoshida et al., 1994; Cutler et al., 1997; Audhya et al., 2000; Audhya and Emr, 2002), therefore we examined whether sorbitol could remedy the C. albicans mss4 defects. Sorbitol reduced the percentage of inviable cells to ∼5% (Fig. 2 A), as well as the actin cytoskeleton defect (Fig. 2 E), yet we still observed little to no filamentous growth (Fig. 2 B). We next examined whether localization of the critical small G-protein Cdc42 was altered in the C. albicans mss4 strain, as is the case in a S. cerevisiae mss4ts mutant (Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a). In the C. albicans mss4 mutant, GFP-Cdc42 is localized to small buds irrespective of whether this kinase was repressed, similar to wt cells (Fig. 2 F; Hazan and Liu, 2002). The ratio of GFP-Cdc42 signal at the PM to cytoplasm indicated that there was no loss of PM-associated Cdc42 (1.91 ± 0.29 in the absence of Dox vs. 1.81 ± 0.31 in its presence; n = 36). Together, these results indicate that the filamentous growth defect of the mss4 mutant is not due to inviability, perturbation of the actin cytoskeleton, or Cdc42 localization.

Figure 2.

The mss4 filamentous growth defect is not due to perturbation of the actin cytoskeleton or altered Cdc42 localization. (A) Inviability of mss4 mutant is suppressed by sorbitol and unaffected by FCS. The mss4 strain (left) or indicated strains (right) were grown in the presence or absence of Dox, with and without 0.5 M sorbitol, and incubated with FCS for indicated times (right). Average percentage of inviable cells (ni.ex. = 3; n = 4 determinations; 75 cells each [left]; and ni.ex. = 2; 10 times 50 cells each [right]). (B) Inviability of mss4 mutant is not responsible for filamentous growth defect. The percentage of filamentous cells after 2 h in FCS from A (left). Images of indicated cells grown with 0.5 M sorbitol (ni.ex. = 3; right). (C) The actin cytoskeleton is disorganized in mss4 cells. Actin cytoskeleton in indicated strains grown with or without Dox incubated with FCS. Maximum projections (4–8 z-sections [left]; 6–9 z-sections [right]) of representative budding cells from different fields of view (left; ni.ex. = 2). (D) Quantitation of actin patch distribution in budding mss4 cells. Averages indicated with bars showing values (ni.ex. = 2; 150 cells each). (E) Sorbitol restores polarized actin patch distribution in mss4 cells. Actin patch polarity was determined in indicated budding cells (ni.ex. = 2; n = 160 cells in the absence and presence of 0.5 M sorbitol). (F) Cdc42 localization is unaffected in the mss4 mutant. Central, sum, and maximum projections (10 z-sections) of representative mss4 cells expressing GFP-Cdc42 from different fields of view. A cluster of GFP-Cdc42 was apparent within the bud of some cells (+ Dox; ni.ex. = 2).

A steep gradient of PI(4,5)P2 emanates from the germ tube tip

Our results suggest that PI(4,5)P2 is critical for the transition from budding to hyphal growth. Therefore, we examined the in vivo PI(4,5)P2 distribution using a protein domain that specifically binds this lipid as a reporter (Kavran et al., 1998; Stauffer et al., 1998). The rat Plcδ pleckstrin homology (PH) domain fused to GFP localizes to the PM in S. cerevisiae and this localization depends upon Mss4p (Stefan et al., 2002). Recently, it has been shown using this reporter in S. cerevisiae that PI(4,5)P2 localizes preferentially to the mating projection (Jin et al., 2008; Garrenton et al., 2010). As we were unable to detect a substantial fluorescence signal in C. albicans with a codon-optimized PHPlcδ-GFP reporter, we fused another copy of the codon-optimized GFP-PHPlcδ to the N terminus of this reporter. We reasoned that the resulting GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP might enhance the apparent binding affinities for PI(4,5)P2 through avidity effects from GFP dimerization and tandem PH domains (Hammond et al., 2009). Initially, we determined whether this PI(4,5)P2 reporter perturbed C. albicans growth, as has been previously shown in mammalian cells (Raucher et al., 2000). We did not observe any deleterious effect of this reporter in either a wt or mss4 strain. With this optimized reporter, substantial fluorescence signal was observed at the PM (Fig. 3 A). As expected, a marked decrease in the PM signal (14% of cells had a PM signal) and concomitant increase in cytoplasmic signal of this reporter was observed in mss4 strains in which kinase expression was repressed (Fig. 3, A and C). In contrast, the percentage of wt cells with PM signal was unaffected by Dox and similar to that of mss4 cells in nonrepressive conditions. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the reporter levels were similar, irrespective of mss4 repression (Fig. 3 B). To verify that the mss4 strain had altered membrane-associated PI(4,5)P2 levels, we used a mAb, used extensively for PI(4,5)P2 quantitation (Micheva et al., 2001; Faucherre et al., 2005; Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a). It was previously shown in a S. cerevisiae mss4-102 ts mutant there is an ∼40% reduction in the level of PI(4,5)P2 in total cell lysates and 100,000-g fraction (50% of total PI(4,5)P2 was found in the P100 fraction) using this mAb (Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a). We observed a similar decrease in PI(4,5)P2 levels in the C. albicans mss4 strain P100 fraction when MSS4 was repressed (Fig. 3 D).

Figure 3.

Plasma membrane localized PI(4,5)P2 depends on Mss4. (A) The GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP reporter localizes to the PM, dependent on Mss4. Images (top, DIC; bottom, central z-section GFP fluorescence) of representative mss4 cells grown as indicated. (B) Expression level of the PI(4,5)P2 reporter is not affected by reduction of Mss4 level. Immunoblot showing the levels of reporter (α-GFP) and loading control (α-Cdc11), strains and conditions as in A. (C) Quantitation of cells with PM localized PI(4,5)P2. Average percentage of cells with PM localized reporter (ni.ex. = 2–3; 4 determinations, n = 200 cells each) indicated. (D) PI(4,5)P2 levels are reduced in mss4 mutant. PI(4,5)P2 levels from 100,000-g fraction determined in indicated strains using an anti-PI(4,5)P2 mAb (ni.ex. = 2; 4 determinations each).

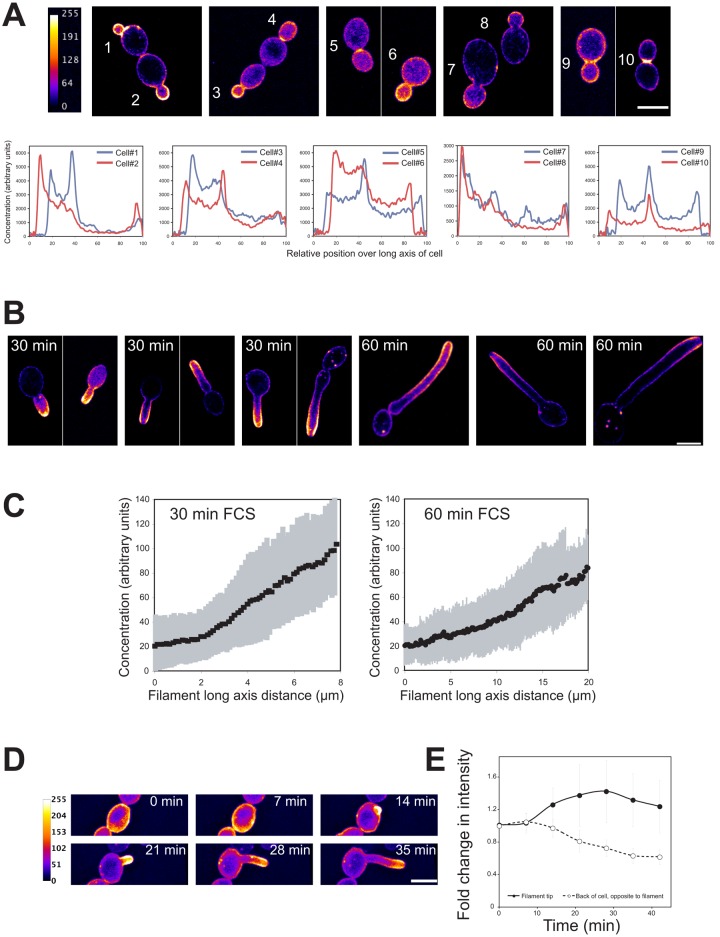

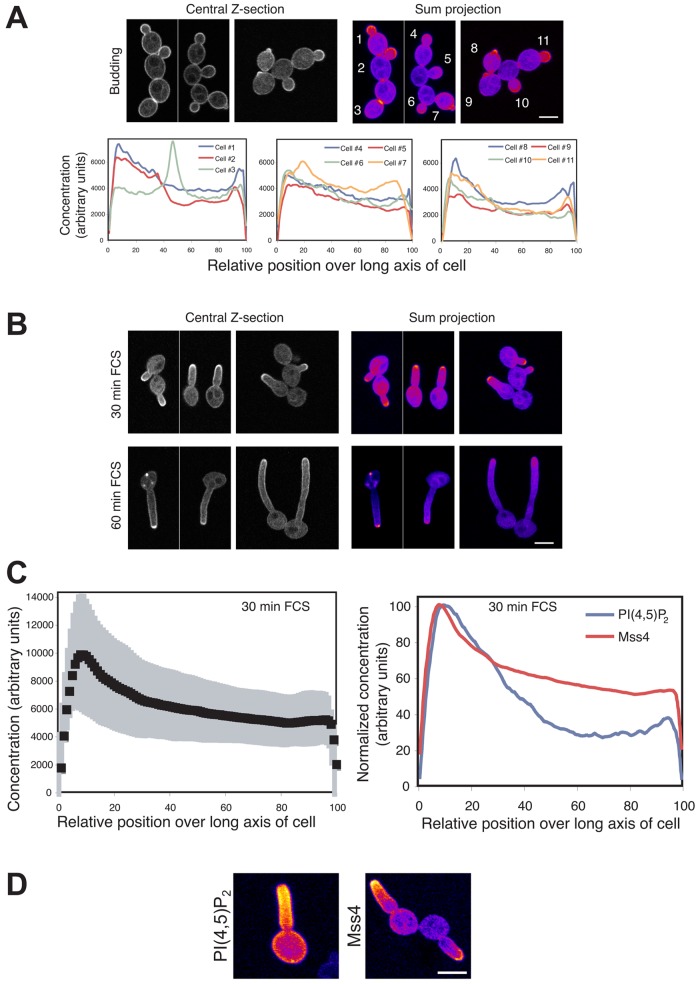

In wt budding cells we observed a striking PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry using this reporter with a strong accumulation in small buds as well as at the site of cell division (Fig. 4 A). We developed two semi-automated Matlab programs, BudPolarity (BP) and HyphalPolarity (HP), to quantify the intensity profile along the major axis of yeast or hyphal form cells, respectively. The latter program was developed for the analyses of cells with nonlinear morphologies such as hyphae. Quantification of the total signal from confocal sum projections revealed a 10–15-fold accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 in small buds with an increased concentration at the tips (Fig. 4 A; cells 1–3). Quantification also revealed a five- to tenfold accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 in medium-sized buds (Fig. 4 A; cells 6–8) and a four- to sixfold accumulation at the site of cell division (Fig. 4 A; cells 4, 5, 9, and 10). In cells with both small and medium buds (cells 1–3, 6–8) there was an abrupt decrease in PI(4,5)P2 concentration after the bud neck, suggesting a diffusion barrier. Time-lapse confocal microscopy revealed that PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry precedes bud emergence (Video 1).

Figure 4.

PI(4,5)P2 is asymmetrically localized in budding and filamentous cells with a steep gradient emanating from the cell tip. (A) PI(4,5)P2 is asymmetrically localized in budding cells. False-colored sum projections (8–12 z-sections) of representative wt budding cells expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter from different fields of view. Signal concentration over the long axis of each cell (in relative units, set to 100, determined by the BP program) starting from the bud (ni.ex. = 4). (B) A steep gradient of PI(4,5)P2 is observed in filamentous cells. Images of representative cells as described in A, incubated with FCS for indicated times from different fields of view (ni.ex. = 5). (C) Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 gradients in cells responding to FCS. Signal concentration (in arbitrary units) was quantified over the cell long axis starting from the cell body using the HP program. Average (n = 25 cells) with SD in gray, individual profiles shown in Fig. S2 A. (D) A PI(4,5)P2 gradient occurs concomitant with germ tube emergence. Time-lapse confocal microscopy of wt cells expressing PI(4,5)P2 reporter in the presence of FCS. Sum projections of 18 deconvolved z-sections. (E) Probe signal increases at germ tube tip concomitant with a decrease at the back of cell. Signal intensity determined in a 1-µm-radius area at the germ tube tip (or where it will form) and at the opposite end of the cells from sum projections as described in D. Average fold change in intensity relative to t = 0 (n = 25 cells). The average slope of the intensity at the back to the cell, −0.0160 ± 0.0037 relative intensity/min was two times greater than that due to photobleaching (determined with GFP-Rac1), −0.0076 ± 0.0017 relative intensity/min (n = 25 cells).

To determine the changes in PI(4,5)P2 distribution during filamentous growth, we examined wt cells responding to FCS for 30 and 60 min. After 30 min small germ tubes were evident, which ranged in length from smaller than the cell body to roughly twice its length (Fig. 4 B). A striking PI(4,5)P2 gradient was observed in these small germ tubes with ∼4–12-fold changes in concentration over the germ tube long axis (Fig. 4 C and Fig. S2 A), with the slope of the gradient varying 10–25 arbitrary concentration units per μm (slope average, 20 units per μm, SD = 8). Little signal was observed in the cell body in contrast to the PI(4,5)P2 gradient, which emanated from the germ tube tip. Although sometimes difficult to discern in sum projections, a small region with reduced signal at the tip of the germ tube (∼1 µm diameter) was observed in all cells. Occasionally, we observed germ tubes growing in the z-axis and wherein a ring of PI(4,5)P2 was observed with reduced signal in the center (two- to threefold reduced compared with ring, yet the center area had an approximately twofold increased signal level compared with the cell body; Fig. S2 B). This reduction in signal at the tip could be due to either a reduced PI(4,5)P2 level or reduced accessibility of the reporter. After 1 h in FCS, a PI(4,5)P2 gradient was still evident, with approximately two- to eightfold changes in concentration over the length of the filament and slopes that varied between 3 and 8 arbitrary concentration units per μm (average of slopes, 6 units per μm, SD = 4; Fig. 4 C and Fig. S2 A). These results indicate that as the hyphal filament elongates, the steepness of the PI(4,5)P2 gradient is reduced, perhaps due to increased effective diffusion, increased hydrolysis, or decreased synthesis. Hence, we examined the initiation of the PI(4,5)P2 gradient using time-lapse microscopy, and Fig. 4 D shows that the PI(4,5)P2 gradient occurs concomitant with germ tube emergence. Quantitation revealed that upon germ tube emergence there is an increase in PI(4,5)P2 levels at the germ tube tip concomitant with a decrease in signal at the back of the cell (Fig. 4 E), suggestive of local PI(4,5)P2 synthesis or recruitment at the tip concomitant with degradation or clearing at the back of cell. All together, these results indicate that a pronounced PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry is generated and maintained during bud growth. Furthermore, during filamentous growth a steep PI(4,5)P2 gradient emanates from the filament tip and descends down the filament.

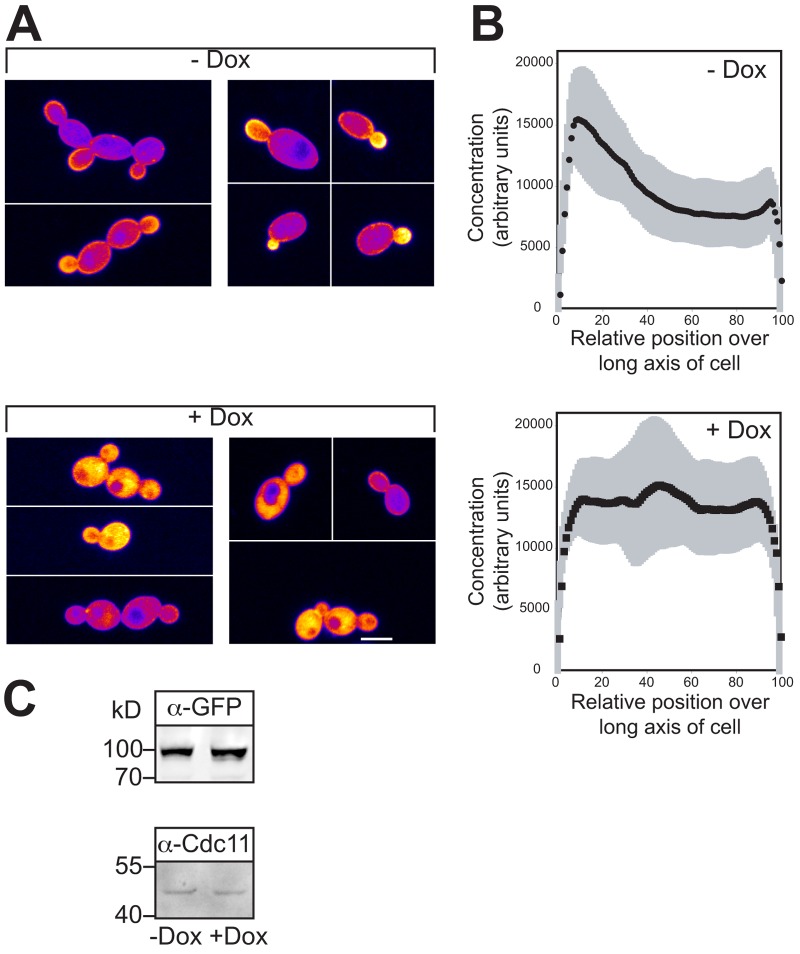

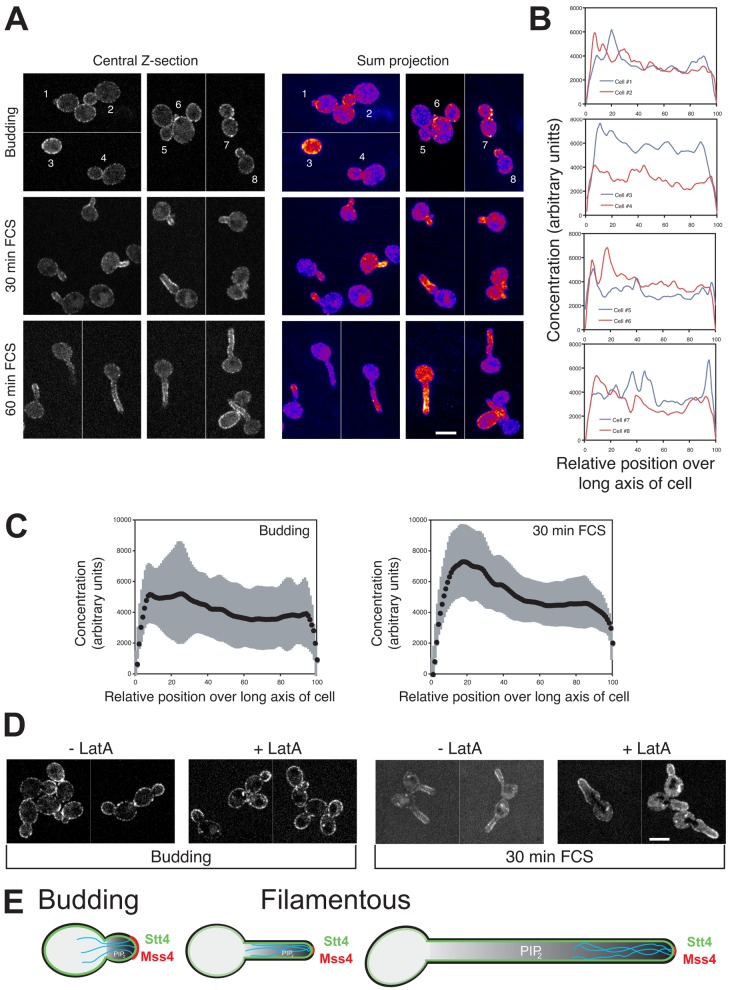

The PI-4-kinase Stt4 and actin are required for the steep PI(4,5)P2 gradient

We tested whether a specific level of PI(4)P or the actin cytoskeleton is required for PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry in budding and filamentous cells. First we investigated whether reduction in Stt4 levels affected the PI(4,5)P2 distribution. In the stt4 strain we did not observe a marked difference in the percentage of cells with PM PI(4,5)P2 when the expression of this kinase was repressed compared either to the absence of repression or wt cells (Fig. 3 C). However, there was an increase in cells with both PM and cytoplasmic signal of approximately threefold when the kinase was repressed (17 ± 4% in the presence of Dox compared with 5 ± 0.9% in its absence). Analyses of the PI(4,5)P2 level in the P100 fraction indicated that there was little decrease in this lipid when Stt4 was repressed (Fig. 3 D). Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 concentration across the cell long axis revealed that in nonrepressive conditions this stt4 strain had asymmetrically distributed PI(4,5)P2, whereas upon repression, a striking loss of asymmetry was apparent (Fig. 5, A and B; and Fig. S3 A). In such conditions, there did not appear to be a decrease in reporter signal (Fig. 5, A and B) or levels (Fig. 5 C). Although there was a decrease in the PM signal, all cells nonetheless had some enrichment of PI(4,5)P2 at the PM (Fig. S3 B). However, only 10% of the cells exhibited a polarized PI(4,5)P2 distribution (n = 100 cells). Furthermore, in the presence of FCS we did not observe a PI(4,5)P2 gradient in the elongated stt4 mutants (not depicted; note this mutant does not form hyphal filaments). All together, these results suggest that sufficient PI(4)P synthesis is necessary for the asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution at the PM, which is critical for filamentous growth.

Figure 5.

Sufficient PI(4)P is necessary for PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry. (A) Asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution requires normal PI(4)P levels. Images of representative cells, as described in Fig. 4 A. Stt4 cells expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter were grown in the presence or absence of Dox (ni.ex. = 3). (B) Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 concentration over long axis of budding cells. Average signal concentration over the long axis of small budded cells from A is shown with SD in gray, as described in Fig. 4 A (n = 15 cells, individual profiles shown in Fig. S3 A). (C) Reduction of Stt4 levels does not affect PI(4,5)P2 reporter levels. Immunoblot showing the levels of the reporter (α-GFP) and loading control (α-Cdc11) in the strains used in A.

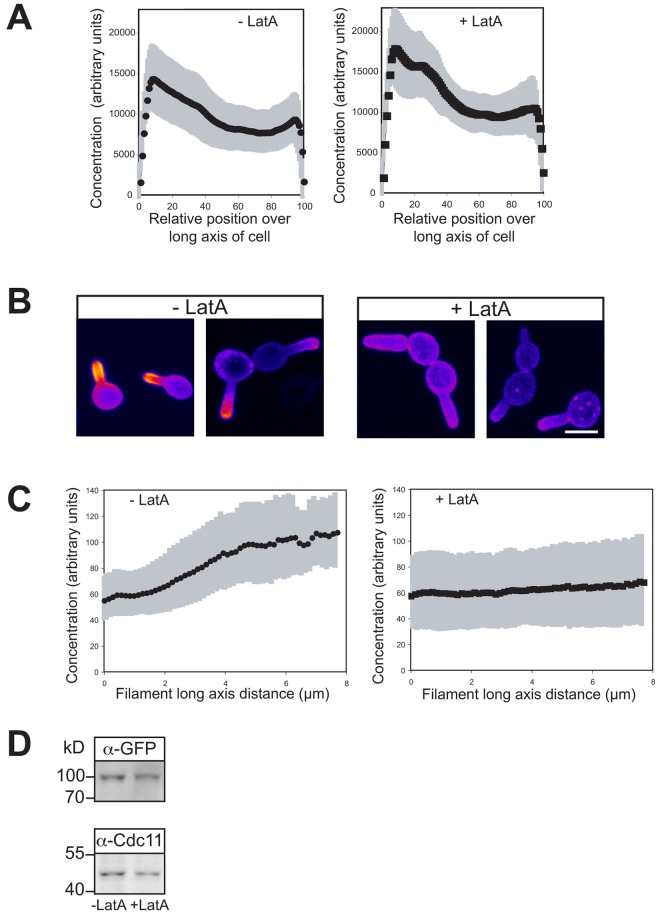

To define the role of the cytoskeleton in the PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry, we examined whether actin and microtubules (MTs) are necessary for this asymmetry in budding and filamentous cells. Preventing actin polymerization with latrunculin A (LatA) blocks filamentous growth (Hazan and Liu, 2002). An asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution was still observed in budding wt cells, with increased accumulation in small buds (Fig. 6 A and Fig. S3 C) subsequent to LatA treatment (which completely disrupted the actin cytoskeleton; Fig. S4, A and B). Furthermore, the percentage of budding cells with a polarized PI(4,5)P2 distribution was similar in the presence (84 ± 11) and absence (90 ± 14) of LatA (n = 50 cells). In contrast, when filamentous cells were treated with LatA, there was a striking loss of the PI(4,5)P2 gradient (Fig. 6, B and C); after 30 min incubation with FCS, a PI(4,5)P2 gradient was observed that disappeared after incubation with LatA (which completely disrupted F-actin; Fig. S4, A and B), yet the level of the PI(4,5)P2 reporter was not substantially altered (Fig. 6 D). Before LatA treatment, 96% of cells had a discernable PI(4,5)P2 gradient, compared with 11% after incubation with LatA (SD = 4.5, n = 100 cells). In addition, LatA did not result in a substantial decrease in PM PI(4,5)P2; the ratio of reporter signal on the PM to the cytoplasm was 2.52 ± 0.34 in the absence of LatA and 2.25 ± 0.37 in its presence (n = 30 cells). These results indicate that the actin cytoskeleton is specifically required during hyphal growth to maintain a PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry, perhaps critical for restricting localization of the lipid kinases or phosphatases or their substrates via membrane traffic.

Figure 6.

The actin cytoskeleton is critical for maintaining PI(4,5)P2 gradient in filamentous cells. (A) F-actin is not required for an asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution in budding cells. Cells (wt) expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter were treated with 200 μM LatA for 15 min. Average signal concentration over the long axis of small budded cells as described in Fig. 4 A (ni.ex. = 3; n = 25 cells) with SD in gray. (B) F-actin is critical for PI(4,5)P2 gradient in hyphae. Sum projections (10 z-sections) of representative cells, as described in Fig. 4 B. Cells as in A were treated with FCS for 30 min and then incubated in the presence or absence LatA as in A (ni.ex. = 5). (C) Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 gradients in cells responding to FCS. Signal concentration over the long axis of each the cell as described in Fig. 4 C. Cells were treated as described in B. Averages (n = 48 cells) shown with SD in gray. (D) Depolymerization of the actin cytoskeleton does not affect PI(4,5)P2 reporter expression levels. Immunoblot showing the levels of the reporter (α-GFP) and loading control (α-Cdc11) in the strains and conditions used in C.

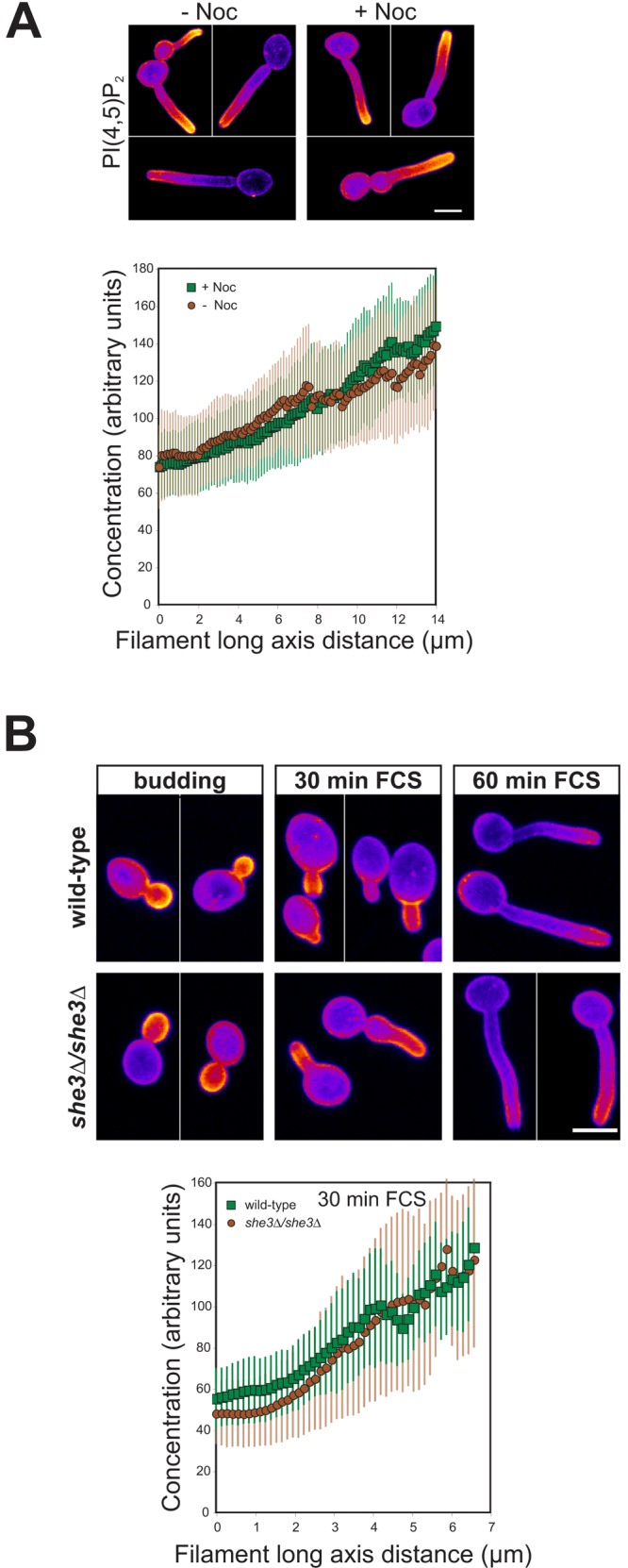

We also investigated whether the PI(4,5)P2 gradient observed in filamentous cells required an intact MT cytoskeleton. wt cells expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter were incubated with FCS for 30 min and then incubated in the presence or absence of nocodazole (Noc). These conditions were sufficient to disrupt the MTs (Fig. S4, C and D), confirmed by perturbation of Tub1-GFP and Kar9-GFP localization (not depicted). Nonetheless, we observed a gradient of PI(4,5)P2 that was indistinguishable to that observed in the absence of Noc, indicating that MTs are not critical for maintaining this gradient (Fig. 7 A).

Figure 7.

Neither the microtubule cytoskeleton nor asymmetrically localized MSS4 mRNA is required for the PI(4,5)P2 gradient in hyphal filaments. (A) The PI(4,5)P2 gradient in hyphal filaments is not affected by Noc. wt cells expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter were incubated for 30 min with FCS; 40 μM Noc was then added and incubated for an additional 30 min. Sum projections of 12 z-sections of representative cells (top), as described in Fig. 4 B (ni.ex. = 5). Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 gradients in cells (bottom). Average signal concentration over the cell long axis as in Fig. 4 C (n = 20 cells) is shown. (B) The She3 adaptor protein is not required for PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry. Strains expressing PI(4,5)P2 reporter where incubated as indicated. Sum projections of 12 z-sections are shown for representative cells (top), as described in Fig. 4 B (ni.ex. = 2). Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 gradients in cells responding to FCS for 30 min (bottom). Average signal concentration over the cell long axis as in Fig. 4 C (n = 25 cells) is shown.

Recently, Elson et al. (2009) identified MSS4 as a She3-associated transcript, which accumulates in C. albicans bud and hyphal tips. As asymmetric mRNA localization has been shown to be actin dependent in S. cerevisiae (Long et al., 1997; Takizawa et al., 1997), we investigated whether She3 was required for the asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution in budding and filamentous cells. Fig. 7 B shows that the asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution is identical in the absence and presence of SHE3, in budding cells and in filamentous cells, suggesting that asymmetric distributed MSS4 mRNA is not critical for a PI(4,5)P2 gradient.

PI(4,5)P2 dynamics at the plasma membrane

We examined the dynamics of PI(4,5)P2 at the PM using fluorescence photobleaching approaches with wt cells expressing the PI(4,5)P2 reporter and the fluorescence recovery curves; t1/2 for recovery and mobile fractions in budding and filamentous cells are shown (Fig. S5, A–D; Table 1). The t1/2 for recovery in cells with small buds was significantly higher (slower recovery) compared with that in filamentous cells (P < 0.0001). However, disruption of the actin cytoskeleton in cells after 30 min incubation with FCS resulted in a slower recovery (increased t1/2) and reduced mobile fraction (P = 0.001 for t1/2 and 0.016 for mobile fractions), similar to that observed in budding cells. As the distribution of PI(4,5)P2 in budding cells suggested that this lipid was unable to diffuse across the bud neck, from the daughter bud to the mother cell, we performed fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) to test this. We either photobleached the entire bud or mother cell in small budded cells and followed the fluorescence signal in the bleach ROI (FRAP) or in the nonbleached part of the cell (FLIP). Fig. S5 E shows there is little loss of fluorescence in one cellular compartment upon complete photobleaching of the other, and conversely little fluorescence recovery in the bud or mother cell after photobleaching, suggesting the PI(4,5)P2 reporter from one compartment does not appreciably move to the other compartment during 45 s. All together, these fluorescence photobleaching results suggest that there is a diffusion barrier at the bud neck that limits the movement of PI(4,5)P2 between the mother and daughter compartments.

Table 1.

PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 dynamics

| Condition | t1/2 (s) | Mobile Fraction | n |

| PI(4,5)P2 | |||

| Budding | 15.8 ± 4.5 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 12 |

| 30 min FCS | 9.6 ± 3.3 | 0.74 ± 0.16 | 22 |

| 30 min FCS + LatA | 13.5 ± 3.3 | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 16 |

| 60 min FCS | 9.5 ± 3.4 | 0.68 ± 0.09 | 12 |

| Mss4 | |||

| Budding | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 11 |

| 30 min FCS | 6.1 ± 2.7 | 0.90 ± 0.11 | 12 |

| 60 min FCS | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 0.82 ± 0.10 | 11 |

FRAP analyses were carried out as described in Fig. S5 and Materials and methods with a circular area of 0.6 µm2 photobleached. For PI(4,5)P2 FRAP analyses, wild-type cells expressing the GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP reporter were used.

Mss4, but not Stt4, is enriched at the tips of hyphal filaments

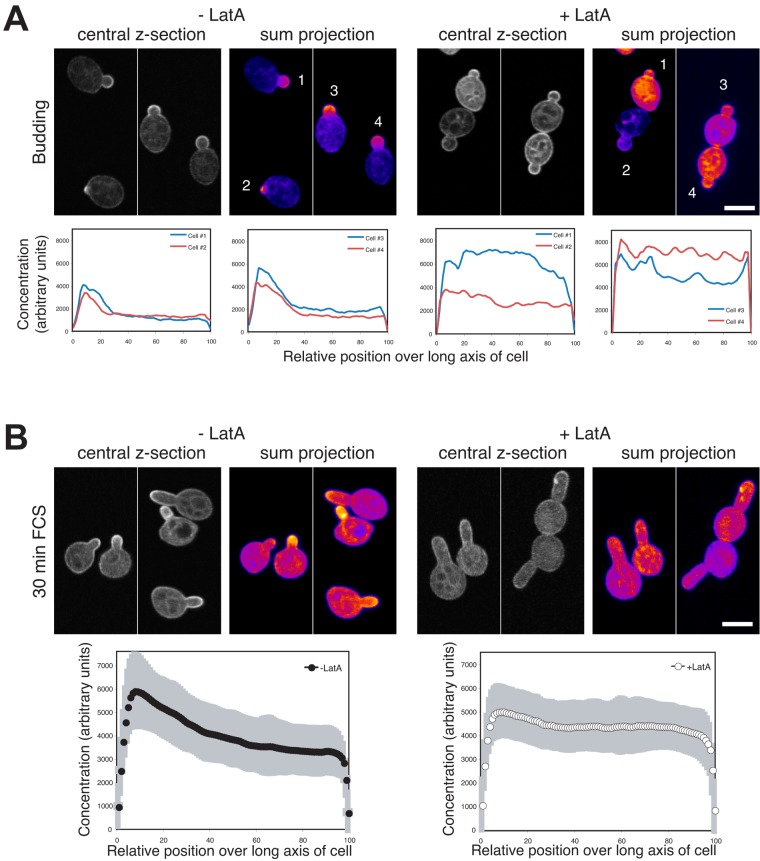

Although the asymmetric distribution of MSS4 mRNA is not required for the PI(4,5)P2 gradient, it was nonetheless possible that the Mss4 protein was localized in a polarized fashion. Therefore, we generated a GFP Mss4 fusion that complemented the filamentous growth of the mss4 mutant in repressive conditions and examined its localization. Fig. 8 A shows that Mss4 localizes to the PM and is highly enriched in small buds. This Mss4 distribution was similar to that of PI(4,5)P2 in budding cells. In cells responding to FCS, Mss4 localized to the tips of the hyphal filaments in a tight cluster (Fig. 8 B). Although the distribution of Mss4 in hyphal cells was highly polarized, we did not observe a gradient as was seen with PI(4,5)P2 in these cells (Fig. 8 B). Furthermore, we confirmed that this polarized distribution of Mss4 did not require She3, as a similar distribution was observed in she3Δ/she3Δ cells (Fig. S4 E). The HP program was not ideal for quantifying Mss4 distribution, as this program determines reporter distribution on the right and left side of the cell and has difficulty bisecting a polarized signal at the cell tip. Hence, we used the BP program to quantify the total cellular signal of straight germ tubes. These analyses revealed an approximate twofold increase in Mss4 concentration at the filament tip followed by a gradual decline in concentration over the filament length (Fig. 8 C, left). We compared the PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 distributions using the BP program, and Fig. 8 C (right) shows the normalized distribution of this kinase and the lipid it generates. For both lipid and kinase the concentration decreases logarithmically, with the PI(4,5)P2 levels decreasing approximately threefold steeper than Mss4. These curves can be approximated by two linear fits, with the slope of the initial line (between x values of ∼10–20 for Mss4 and 10–40 for PI(4,5)P2) being indistinguishable, and thereafter the PI(4,5)P2 slope is approximately twofold steeper than that of Mss4. The maximum Mss4 signal is two relative position units (0.2 µm for a 10-µm hyphae) before the maximum PI(4,5)P2 signal, consistent with the decrease in PI(4,5)P2 levels at the filament tip. To investigate this more directly we generated a yemCherry-based PI(4,5)P2 reporter and examined the distribution of PI(4,5)P2 in cells mixed with those expressing GFP-Mss4. Fig. 8 D shows that there is a small decrease in PI(4,5)P2 signal at the filament tip, in contrast to GFP-Mss4 cells in the same field of view, which is enriched at the filament tip. Together, these results suggest that the asymmetric distribution of PI(4,5)P2 is generated by Mss4, which is restricted to the bud and hyphal filament tip.

Figure 8.

Mss4 localizes to small buds and tips of hyphal filaments. (A) Mss4 is localized in a tight cluster in small buds. A mss4 strain expressing GFP-Mss4 was grown in the presence of Dox. Central z-sections and sum projections (12 z-sections) of representative cells are shown (top) and quantification of Mss4 concentration over long axis of cells (bottom) as described in Fig. 4 A (ni.ex. = 3). (B) Mss4 is localized in a tight cluster at hyphal filament tips. Cells were incubated in the presence of FCS as indicated. Images of representative cells as described in A. (C) Quantification of Mss4 concentration over long axis of filamentous cells. Average signal concentration over the long axis of cells incubated with FCS as described in Fig. 4 A (n = 43 cells from B) shown with SD in gray (left) and comparison of PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 distribution (right) as in Fig. 4 A (n = 43 cells from B and 25 cells from Fig. 4 C). Maximum signals for PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 were normalized to 100%. (D) PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 localization in filamentous cells. wt cells expressing yemCh PI(4,5)P2 reporter or GFP-Mss4 were mixed and then treated with FCS for 30 min. Sum projections (8 z-sections) of representative cells as in Fig. 4 B.

We also examined the dynamics of Mss4 at the PM using FRAP. Table 1 shows that fluorescence recovery and mobile fractions of Mss4 were similar between budding and filamentous cells. Mss4 appeared somewhat more dynamic in cells incubated in FCS for 60 min. These results indicate that despite its polarized distribution, Mss4 at the PM is dynamic, either diffusing in the plane of the membrane and/or coming on and off the membrane.

Given that PI(4,5)P2 distribution was dependent on the actin cytoskeleton, we investigated whether the localization of Mss4 to the PM of small buds and the tip of the germ tubes required F-actin. Mss4 cells grown in repressive conditions expressing GFP-Mss4 were treated with LatA and the distribution of this lipid kinase was examined (Fig. 9). In both cells with small buds and short germ tubes, incubation with LatA completely disrupted the Mss4 asymmetries. In both cell types, while PM Mss4 was still visible subsequent to actin depolymerization (Fig. 9, A and B; central z-sections), we observed a substantial increase in signal associated with internal membranes. Quantification of the ratio of PM to cytoplasmic/internal membrane signal confirmed this observation in cells with germ tubes: ratio of 1.58 ± 0.20 (n = 46 cells) in the absence of LatA and 1.17 ± 0.16 (n = 51 cells) in the presence LatA. These results indicate that an intact actin cytoskeleton is critical for the maintaining of Mss4 to sites of growth in budding and filamenting cells.

Figure 9.

Mss4 enrichment to small buds and hyphal filament tips requires the actin cytoskeleton. (A) F-actin is critical for asymmetric distribution of Mss4 in budding cells. A mss4 strain expressing GFP-Mss4 was grown with Dox in the presence or absence of LatA as in Fig. 6 A. Central z-sections and sum projections (10 z-sections) of representative cells from different fields of view are shown (top) and quantification of Mss4 concentration over long axis of cells (bottom) as in Fig. 4 A. (B) F-actin is required for asymmetric Mss4 distribution in germ tubes. A mss4 strain expressing GFP-Mss4 was treated with FCS and then incubated with LatA as in Fig. 6 B. Images as described in Fig. 9 A (top) and quantification of Mss4 concentration over long axis of cells (bottom) as in Fig. 4 A (n = 50 cells). For Fig. 9 (A and B), ni.ex. = 3.

As Mss4 was localized in a polarized fashion, it was possible that the lipid kinase, Stt4, which generates PM PI(4)P, the substrate for Mss4, also localized to sites of growth. Hence, we generated a GFP-Stt4 fusion, which complemented the filamentous growth of the stt4 mutant in repressive conditions and examined its distribution. The signal for this GFP fusion was quite weak and hence it was necessary to use a spinning-disk confocal microscope. Stt4 localizes to the PM in punctate fashion, similar to what has been observed in S. cerevisiae (Audhya and Emr, 2002; Baird et al., 2008). In budding cells a 10–20% enrichment of Stt4 in small buds was detected (Fig. 10, A–C). In cells incubated with FCS there was an increase in Stt4 levels in the germ tube compared with the cell body, which was not restricted to the filament tip (Fig. 10, A and C). Furthermore, F-actin was not required for the PM distribution of Stt4 (Fig. 10 D). Taken together, these results indicate that these two lipid kinases have distinct PM distributions and requirements.

Figure 10.

Stt4 localizes to punctae on the plasma membrane, independent of the actin cytoskeleton. (A) Stt4 is localized to the plasma membrane. A stt4 strain expressing GFP-Stt4 was grown in the presence of Dox. Central z-sections and false-colored sum projections (21 z-sections) of representative cells grown as indicated are shown (ni.ex. = 3). (B) Quantification of Stt4 concentration over long axis of budding cells. Signal concentration over the long axis of budding cells from A, as described in Fig. 4 A. (C) Average GFP-Stt4 signal concentration over the long axis of budding cells or cells incubated with FCS as described in Fig. 4 A (n = 41 cells from A) is shown with SD in gray. (D) F-actin is not required for plasma membrane distribution of GFP-Stt4. Strains as in A were treated with LatA, described in Fig. 6 A. Central z-sections of representative cells are shown (ni.ex. = 2). (E) Schematic representation of the mechanisms involved in generating and maintaining long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient in filamentous cells. PI(4,5)P2 gradient shown (gray) in cell with actin cables (cyan) and Mss4 (red) and Stt4 (green) indicated.

Discussion

Our results show that PI(4,5)P2 is required for a critical morphology change, the yeast-to-hyphal growth transition in C. albicans. Furthermore, we show that PI(4,5)P2 is asymmetrically distributed in both budding and filamentous cells. In budding cells we observed a prominent accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 in small buds and at the site of cell division, and FRAP studies indicate that a barrier to PI(4,5)P2 diffusion exists at the bud neck. Furthermore, concomitant with filamentous growth we observed a steep gradient of PI(4,5)P2. Our results indicate that the PI-4-kinase Stt4 and the actin cytoskeleton are required for this steep PI(4,5)P2 gradient, which appears to be critical for filamentous growth. We propose that synthesis of PI(4,5)P2 by the filament tip–localized Mss4 PI(4)P-5-kinase, slow diffusion of PI(4,5)P2 in the PM, together with clearing of this lipid at the back of the cell are important for generating and maintaining a stable PI(4,5)P2 gradient over long distances (Fig. 10 E).

PI(4,5)P2 asymmetries and gradients

In response to different external signals, PI(4,5)P2 asymmetries are generated in a range of cell types. These polarized lipid distributions are due in part to site-specific synthesis and degradation of phosphoinositide phosphates. In addition to such an asymmetric PI(4,5)P2 distribution in budding C. albicans cells, we observed a striking, long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient over the length of the hyphal filament. This is, to our knowledge, the first example of such a PI(4,5)P2 gradient. In cells with similar, highly elongated morphologies, i.e., filamentous fungi hyphae, plant pollen tubes, and neuronal axons, such PI(4,5)P2 gradients have not been observed. In Aspergillus nidulans hyphae, PI(4,5)P2 PM distribution is relatively uniform (Pantazopoulou and Peñalva, 2009). In contrast, in tobacco and Arabadopsis pollen tubes PI(4,5)P2 has been observed predominantly at the apical region as well as at the subapical region (Kost et al., 1999; Ischebeck et al., 2008, 2011; Zhao et al., 2010). Interestingly, in these cells there was only partial overlap between the distribution of this lipid and the PI(4)P-5-kinases responsible for its synthesis, with the kinases excluded from the apical region and observed in a subapical ring. We also observed partially overlapping kinase and PI(4,5)P2 distributions in C. albicans hyphal filaments; however, conversely, we observed the kinase at the filament tip and the PI(4,5)P2 gradient subapically. Finally, no detectable concentration gradient of PI(4,5)P2 has been observed in neuronal axons (Micheva et al., 2001; De Vos et al., 2003).

In the fission yeast S. pombe, PI(4,5)P2 appears to be uniformly distributed on the PM with an enrichment at the septum of dividing cells (Zhang et al., 2000). Recent studies in S. cerevisae have revealed a PI(4,5)P2 anisotropy in shmoos (Garrenton et al., 2010), which is likely to be similar to the PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry we observe in C. albicans budding cells. However, in contrast to the PI(4,5)P2 gradient we observed in C. albicans hyphal filaments, a graded decrease in PI(4,5)P2 concentration was not apparent in S. cerevisae (Garrenton et al., 2010), which may be due to the different contributions of endocytosis and exocytosis in these fungi as well as the different Mss4 distributions. In S. cerevisiae, Mss4 is uniformly distributed on the PM (Homma et al., 1998; Audhya and Emr, 2003; Garrenton et al., 2010). Consistent with these differences, the actin cytoskeleton does not appear to be required for the PI(4,5)P2 anisotropy in S. cerevisiae shmoos (Garrenton et al., 2010). Furthermore, the PI(4,5)P2 anisotropy is lost when stt4ts S. cerevisiae shmoos were incubated at the restrictive temperature for 1 h (Garrenton et al., 2010). However, given that this stt4ts mutant exhibits inviability as well as a disorganized actin cytoskeleton at this temperature (Yoshida et al., 1994; Cutler et al., 1997; Audhya et al., 2000), this loss of asymmetry it is difficult to interpret. What processes are critical for the initiation and maintenance of a lipid gradient over 10–20 µm in C. albicans?

Generation and maintenance of long-distance stable PI(4,5)P2 gradient

We examined several different cellular mechanisms that may play a role in generating and maintaining a PI(4,5)P2 gradient. These different mechanisms could function at the level of the Mss4 kinase, its substrate PI(4)P, and/or its product PI(4,5)P2. Our results show that Stt4 is distributed as puncta, at the PM in budding cells with a slight enrichment in the buds. In filamentous cells, even though Stt4 is not concentrated at the hyphal tip as is Mss4, there are increased levels in the hyphal filament. Stt4 is required for asymmetrically localized PI(4,5)P2 in budding cells and the yeast-to-hyphal transition. It also is possible that PI(4)P is localized in a polarized fashion, either via site-specific delivery of PI or PI(4)P via exocytosis, local activation of this PI-kinase, and/or site-specific PI(4)P phosphatases. In C. albicans, it is possible that PI(4)P originating from the Golgi, generated by Pik1, could contribute to the PM PI(4)P. However, in S. cerevisiae the Golgi and PM pools of PI(4)P are functionally distinct (Audhya et al., 2000), suggesting that Golgi-derived PI(4)P, which is generated by Pik1, does not substantially contribute to the PM PI(4)P. Furthermore, in this yeast it has been shown that secretory vesicle–mediated delivery of PI to the PM stimulates PI(4,5)P2 production via Stt4 and Mss4, which is likely to occur at sites of growth and is actin dependent (Routt et al., 2005; Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a). We speculate that nonclassical PI transfer proteins and secretion may be important for C. albicans filamentous growth and lipid asymmetries.

With respect to Mss4, our results show that this PI(4)P-5-kinase is localized to the tip of the bud and germ tube and that this polarized distribution requires an intact actin cytoskeleton. Although MSS4 mRNA has been shown to be asymmetrically distributed in budding and hyphal cells, the distribution of GFP-Mss4 and PI(4,5)P2 was unaffected in a she3 mutant, indicating that MSS4 mRNA distribution is not critical for the polarized localization of this kinase and PI(4,5)P2. Interestingly, GFP-Mss4 distribution in budding cells is dependent on the actin cytoskeleton, whereas we did not detect perturbation of the PI(4,5)P2 asymmetry in budding cells treated with LatA. One can envision, for instance, that sufficient Mss4 is still localized in budding cells treated with LatA or that the critical parameter in budding cells is the diffusion barrier at the bud neck. Irrespective, our results indicate that actin-dependent Mss4 distribution plays an important role in the long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient observed in hyphae.

To maintain a stable lipid gradient over long distances, it is necessary to limit diffusion in the plane of the membrane (McLaughlin et al., 2002; Hilgemann, 2007). The restriction of PI(4,5)P2 lateral diffusion in the PM by the actin cytoskeleton has been proposed to be important for decreasing the diffusion of this lipid. Our FRAP analyses suggest that PI(4,5)P2 mobility in the PM is quite slow (discussed in the following paragraph), and furthermore, the actin cytoskeleton is not required for this reduced mobility; but rather disruption of F-actin further reduces PI(4,5)P2 mobility. It should be noted that LatA treatment will remove both endocytic and exocytic contributions, as well as perturb the distributions of a range of protein, e.g., Mss4. Moreover, our analyses of PI(4,5)P2 distribution in germ tubes using time-lapse confocal microscopy suggest that concomitant with this lipid being generated at the tip of the germ tube, it is cleared from the back of the cell. This clearance could be due to hydrolysis by specific phosphatases or endocytosis. Together our studies indicate that the following processes all contribute to the generation and maintenance of a steep PI(4,5)P2 gradient in hyphae: the actin cytoskeleton, likely to be important for site-specific delivery of PI to the PM, the actin-dependent targeting of Mss4 to the germ tube tip, the clearing of PI(4,5)P2 from the back of the cell, and the decreased diffusion of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 10 E).

Plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 diffusion

Despite local accumulation of PI(4)P-5-kinases, reduced or limited diffusion of PI(4,5)P2 is critical to enable local build-up (McLaughlin et al., 2002; Hilgemann, 2007). If the diffusion coefficient of PI(4,5)P2 were similar to that of mammalian cells, in the range of 0.1–1 µm2/s (Yaradanakul and Hilgemann, 2007; Golebiewska et al., 2008; Hammond et al., 2009), diffusion would be too rapid for accumulation in small buds and the generation of a stable, long-range gradient. Using a similar reporter, Hammond et al. (2009) showed that PI(4,5)P2 diffusion was ∼0.25 µm2/s in HEK cells and 0.05 µm2/s in CHO-M1 cells. Furthermore, this study suggested that over several seconds, exchange of these reporters (between bound and unbound forms) dominates recovery. If our FRAP recovery data reflect exchange of the reporter on and off the plasma membrane, then diffusion of PI(4,5)P2 is likely to be slower to not substantially affect these recoveries. Assuming the observed FRAP t1/2 represents the maximum rate of diffusion, we estimate the apparent diffusion coefficient for PI(4,5)P2 in C. albicans budding cells to be 0.0028 ± 0.0008 µm2/s, a value that is of the same order of magnitude as that estimated for the integral membrane ABC transporter Candida drug resistance protein, Cdr1 (Ganguly et al. 2009). In contrast, this value is substantially slower than the diffusion coefficient for PI(4,5)P2 in mammalian cells and 10–15 times slower than that observed for prenylated GFP in S. cerevisiae (0.030 ± 0.019 µm2/s [Marco et al., 2007] and 0.046 µm2/s [Fairn et al., 2011]), which is similar to what we observed for prenylated GFP in C. albicans (Vauchelles et al., 2010; unpublished data). In addition to reducing the diffusion rate of lipids, “fences” or barriers, which impede diffusion, for example via the cytoskeleton (Hilgemann, 2007), have been proposed and recently been observed in macrophages during phagosome formation (Golebiewska et al., 2011). In budding C. albicans cells we did not observe a difference in PI(4,5)P2 mobility in the mother or bud. However, upon photobleaching one of these compartments there was no substantial loss of signal from the other compartment, suggesting that the PI(4,5)P2 reporter doesn’t move appreciably from one compartment to the other. It has been suggested that septins may serve as a barrier to restrict PI(4,5)P2 diffusion in S. cerevisiae (Garrenton et al., 2010). Indeed, septins have been shown to act as diffusion barriers restricting the distribution of integral and membrane-associated proteins (Barral et al., 2000; Takizawa et al., 2000; Dobbelaere and Barral, 2004; Hu et al., 2010) and to bind phosphoinositide phosphates (Zhang et al., 1999; Casamayor and Snyder, 2003; Tanaka-Takiguchi et al., 2009; Bertin et al., 2010). The barriers to PI(4,5)P2 diffusion we detected in C. albicans are likely to involve the septin cytoskeleton, as a septin ring is observed at the mother–bud neck (Sudbery, 2001; Warenda and Konopka, 2002). Hence, reduced lipid diffusion together and a barrier that impedes diffusion are likely to be important for a long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient in hyphae and increased concentrations of PI(4,5)P2 in small buds, respectively.

Functions of a steep, long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient

We can envision a number of possible functions of such a long-range PI(4,5)P2 gradient. For example, a graded distribution may be important for localizing different signaling proteins, such as those with PH or basic rich domains that are found in proteins involved in cell polarity (Audhya and Emr, 2002; He et al., 2007; Takahashi and Pryciak, 2007; Orlando et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Furthermore, such a gradient may be part of a spatial signal that is involved in the proper placement of the septin and/or actin cytoskeleton. Similarly, given the importance of PI(4,5)P2 for exocytosis and endocytosis in range of organisms including S. cerevisiae (Sun et al., 2005, 2007; He et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008; Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a), such a gradient in hyphae and asymmetric distribution in budding cells may play a central role in dictating the distribution of exocytic and endocytic zones in an actin-dependent fashion on the PM, likely to be critical for filamentous growth. Further analyses of this PI(4,5)P2 gradient and a range of PI(4,5)P2-dependent processes will undoubtedly shed light on lipid dynamics and their function during polarized growth.

Materials and methods

Strain and plasmid construction

Standard methods were used for C. albicans cell culture, molecular and genetic manipulations (see Hope et al., 2008). Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1. Number of independent experiments in which similar results are observed are indicated as ni.ex. To generate Dox-repressible strains, the tetracycline-regulatable transactivator TetR-ScHAP4AD was first introduced into the ENO1 locus of a ade4Δ::hisG/ade2Δ::hisG derivative of BWP17 using pCAITHE5 as described previously (Nakayama et al., 2000). mss4Δ/pTetMSS4 and stt4Δ/pTetSTT4 strains were constructed by first replacing one copy of the respective ORF with HIS1 using homologous recombination with a knockout cassette generated by amplification of pGemHIS1 with MSS4.P1 and MSS4.P2 or STT4.P1 and STT4.P2 primers. A Tetoff promoter was then inserted 3′ of the respective ORF by homologous recombination using pCAU98 plasmid (Nakayama et al., 2000) as a template and primers MSS4.P3 and MSS4.P4 or STT4.P3 and STT4.P4 to amplify a URA3-Tetoff cassette. mss4Δ/mss4Δ strains carrying an additional copy of either MSS4 or mss4-f12 integrated at the RP10 locus were constructed by first replacing one copy of the MSS4 ORF with URA3 using homologous recombination with a knockout cassette generated by PCR amplification of pDDB57 (Wilson et al., 2000) with primers MSS4.P1 and MSS4.P2. The resulting mss4Δ/MSS4 strain was transformed with either pExpArg-pACT1MSS4 or pExpArg-pACT1mss4-f12 (mss4[S514P]) plasmids for integration into the RP10 locus. The remaining genomic MSS4 ORF was replaced with HIS1 using a knockout cassette generated by PCR amplification of pGemHIS1 with MSS4.P1 and MSS4.P2. This resulted in mss4Δ/mss4Δ mss4-f12 and mss4Δ/mss4Δ MSS4 strains. As a control, a wild-type MSS4 copy was reintegrated into these two strains replacing URA3. A MSS4::SAT1 replacement cassette was constructed by PCR amplification from gDNA of the MSS4 promoter and ORF (from 583 bp 5′ of ATG to the stop codon) using primers MSS4.P5 and MSS4.P6 with unique SacI and SacII at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and MSS4 terminator (from 33 bp 3′ of the stop codon to 853 bp 3′ of the stop codon) using primers MSS4.P7 and MSS4.P8 with unique XhoI and ApaI at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, which were then cloned into both sides of the SAT1 flipper cassette of pSFS5 (Sasse et al., 2011) to generate pMSS4-SAT1Flip. Wild-type MSS4 was reintegrated into the URA3 locus using MSS4::SAT1, which was released from pMSS4-SAT1Flip by digestion with SacI and KpnI.

pExpArg constructs were digested with StuI or AgeI for targeted insertion into the RP10 locus. Two independent clones of each strain were generated, confirmed by PCR as well as immunoblotting and microscopy where relevant. The Tub1-GFP strain was generated by homologous recombination using pGFP-URA3 as described previously (Gerami-Nejad et al., 2001).

Mss4 and Stt4 plasmids were constructed by amplification from gDNA and cloning into pCR2.1 TA; MSS4 (851 bp 5′ of the ATG and 173 bp 3′ of the stop codon; MSS4.P9 and MSS4.P10) and STT4 (925 bp 5′ of the ATG and 726 bp 3′ of the stop codon; STT4.P5 and STT4.P6). Primers with a unique BamHI at the 5′end (MSS4.P11) and a unique MluI at the 3′ end (MSS4.P12) were used to amplify the MSS4 ORF, which was subsequently cloned into pExpArg-pACT1GFPRAC1 (generated by cloning the ACT1 promoter into pExpArg-pADH1GFPRAC1), yielding pExpArg-pACT1MSS4. A unique XhoI site was inserted 920 bp 5′ of the ATG by site-directed mutagenesis (Weiner et al., 1994; STT4.P7 and STT4.P8). A XhoI–NotI STT4 fragment was then cloned into pExpArg-pDCK1DCK1 (Hope et al., 2008), yielding to pExpArg-pSTT4STT4.

The mss4-f12 mutant allele was isolated from a screen for invasive growth-defective S. cerevisiae mss4 mutants, which will be described elsewhere. pExpArg-pACT1mss4-f12 plasmid was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using pExpArg-pACT1MSS4 as a template in order to mutate the codon for Ser 514 to one encoding a Pro in addition to the introduction of a silent ApaI site using MSS4.P13 and MSS4.P14.

Five CTG codons from the sequence encoding the Rat Plcδ PH domain (pRS426-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GF; Audhya and Emr, 2002) coding for Leu7, Leu13, Leu48, Leu74, and Leu115 were altered by site-directed mutagenesis (PHPlcδ.P1–10). Using site-directed mutagenesis a unique BglII site was inserted 5′ PHPlcδ ATG codon (PHPlcδ.P11 and PHPlcδ.P12) and a unique PacI site 5′ of the stop codon (PHPlcδ.P13 and PHPlcδ.P14), yielding pRS426-PHPlcδ-B/P. In parallel, the PHPlcδ domain was amplified by PCR with a unique PacI site 5′ of ATG codon and a SacI–KpnI site 5′ of the stop codon (PHPlcδ.P15 and PHPlcδ.P16). A tandem PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ was generated by cloning PacI–KpnI into pRS426-PHPlcδ-B/P, yielding pRS426-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-B/P/S/K. The PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ or PHPlcδ fragment was cloned into pAW6-X (Bassilana et al., 2005) using unique BglII–SacI sites, yielding pAW6-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP or pAW6-PHPlcδ-GFP. A unique RsrII site was inserted 5′ of the PH domain ATG site by site-directed mutagenesis (PHPlcδ.P17 and PHPlcδ.P18) and the PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP or PHPlcδ-GFP fragment was then sublconed using the unique RsrII–MluI sites of pExpArg-pADH1-GFPRsrIIRac1 or pExpArg-pADH1-RsrIIRac (Hope et al., 2008), yielding to pExpArg-pADH1-GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP or pExpArg-pADH1-PHPlcδ-GFP. yemCherry from CIp-ADH1p-mCherry (Keppler-Ross et al., 2008) was PCR amplified with unique SacI and MluI sites 5′ of ATG and 3′ of stop codon, respectively (primers yemCh.P1 and yemCh.P2), and cloned into pExpArg-pADH1-GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP replacing the 3′ GFP, yielding pExpArg-pADH1-GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-yemCh. yemCherry was then amplified by PCR from this plasmid using primers yemCh.P3 and yemCh.P4 and cloned into the unique RsrII site, yielding pExpArg-pADH1-yemCh-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-yemCh.

The MSS4 promoter was amplified from gDNA by PCR (MSS4.P15 and MSS4.P16) and then cloned using the unique NotI–RsrII sites of pExp-pADH1-GFPRsrIIRac1, resulting in pExpArg-pMSS4-RsrIIRac1. The MSS4 ORF was then amplified using pExpArg-pACT1MSS4 as a template (MSS4.P17 and MSS4.P18) and cloned using the unique RsrII–MluI sites of pExpArg-pMSS4-RsrIIRac1, yielding pExpArg-pMSS4-MSS4. Subsequently, GFP was amplified with RsrII sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends (GFP.P1 and GFP.P2) and cloned into pExpArg-pMSS4-MSS4, yielding pExpArg-pMSS4-GFPMSS4. To construct GFP-STT4 fusion, a unique RsrII site was inserted 5′ of the ATG in pExpArg-pSTT4STT4 by site-directed mutagenesis using plasmids STT4.P9 and STT4.P10. Subsequently, GFP was PCR amplified with RsrII sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends (GFP.P1 and GFP.P2) and cloned into pExpArg-pSTT4RsrIISTT4, yielding pExpArg-pSTT4-GFPSTT4. All PCR-amplified products and site-directed mutagenesis products were confirmed by sequencing.

To repress MSS4 or STT4 expression, cells were grown in YEPD media with 20 µg/ml Dox overnight, then back-diluted and grown to mid-log phase (6–8 h). Cultures were also grown with 0.5 M sorbitol overnight, back-diluted, and then grown similarly. For FCS induction in liquid media, strains were incubated in YEPD media containing 50% FCS at 37°C (Bassilana et al., 2005). For time-lapse microscopy, exponentially growing cells were either spotted on YEPD agar pads at 30°C or mixed with an equal volume of FCS and spotted on 25% YEPD agar–75% FCS pads at 37°C (Bassilana et al., 2005).

Propidium iodide and actin staining

Cell inviability was determined using PI staining of cells for 30 min in the dark, followed by cell washing with 2x PBS (Jin et al., 2005). Actin visualization was performed with Alexa Fluor 568–phalloidin as described previously (Hazan and Liu, 2002). For quantitation, only cells with small buds were counted and were scored as polarized if a majority of the patches were in the bud.

qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR analyses of RNA transcript levels were performed as described previously (Bassilana et al., 2005) with primers indicated in Table S1 on an ABI StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Immunoblot analyses and PI(4,5)P2 quantitation

Immunoblot analyses were performed as described previously (Bassilana et al., 2005; Hope et al., 2008). Membranes were probed with anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (1:2,000; Nern and Arkowitz, 2000) or S. cerevisiae anti-Cdc11 polyclonal antibody (sc-7170,1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (luminol-coumaric acid) on an imaging system (Las3000; Fujifilm). Cell Fractionation and PI(4,5)P2 quantitation was performed as described previously (Yakir-Tamang and Gerst, 2009a). Wild-type or mutant cells (25 OD600 of exponentially growing cells) were harvested and lysed with glass beads and 300 µl of lysis buffer (25 mM KPO4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and complete protease inhibitors; Roche). After cell lysis, equivalent amounts of protein from each extract were centrifuged at 1,500 g to remove intact cells and debris, resulting in total cell lysates. This lysate was further centrifuged at 10,000 g and the supernatant further centrifuged at 100,000 g to yield S10 and S100 fractions, respectively. The pellet fractions were solubilized with lysis buffer containing 1% SDS. The 100,000-g pellet fractions were spotted on nitrocellulose membranes an probed with an anti-PI(4,5)P2 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. 915–2052, Assay Designs). For visualization, membranes were then probed with an Alexa Fluor 680 donkey anti–mouse IgG (H+L) conjugate (1:10,000; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) in the dark followed by extensive washing and quantitation using an Odyssey IR imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). PI(4,5)P2 levels were quantitated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Cell imaging and analyses

Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of cells and colony morphology images were captured using a wide-field and a dissection microscope, respectively, as described previously (Bassilana et al., 2005). DIC images of cells were acquired with a microscope (DMR; Leica) with a 1.32 NA 63x Plan-Apo objective, and colony morphology images were acquired with a dissection scope (MZ6; Leica) at 10x. Images were captured with either a charge-coupled device camera (Micromax; Princeton Instruments, Kodak chip) or a camera (Neo sCMOS; Andor Technology). For the former, IPLab (Scanalytics, Inc.) version 3.5 software was used and for the latter, Solis version 4 software (Andor Technology) was used. For analyses of PI(4,5)P2 distribution, a confocal microscope (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss) on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss) with Zeiss software version 3.2 was used (Bassilana et al., 2005). For confocal microscopy a 1.4 NA 63x Plan-Apo objective and 488-nm laser excitation were used. Voxel size ranged from 70 nm × 70 nm × 500 nm to 140 nm × 140 nm × 700 nm and the pinhole was set to 1 airy unit. Localization studies of both PI(4,5)P2 and Mss4 were also performed on the confocal microscope ((LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss) using both 488- and 543-nm laser lines. Time-lapse microscopy on the Zeiss LSM 510 was performed using a PECON chamber (for 30°C) in addition to an IR lamp (for 37°C) with 8 × 1-µm z-sections. Time-lapse live-cell microscopy of GFP-PHPlcδ-PHPlcδ-GFP–expressing cells and GFP-STT4 distribution studies were performed on a spinning-disk laser confocal microscopy system (Revolution XD; Andor Technology) comprised of a fully motorized inverted microscope (model IX-81; Olympus), a confocal spinning-disk unit (model CSU-X1; Yokogawa Corporation of America), motorized XYZ control (piezo), and two iXon897 EMCCD cameras all controlled by iQ2 software (version 2; Andor Technology). A UplanSApo 1.4 NA 100x objective was used with 488-nm laser excitation. An Okolab chamber was used to maintain cells at 37°C. For time-lapse experiments voxel size was 130 nm × 130 nm × 400 nm and z-stacks acquired every 7 min were deconvolved using Huygens Professional software (version 3.7). Sum projections were quantified using ImageJ. Hyphae and colony filament length were measured with ImageJ. Bar is 5 µm in all images of cells and 1 mm in images of colonies. All samples were imaged in aqueous media, either growth media or briefly centrifuged and resuspended in PBS. All sum projections of the PI(4,5)P2 reporter, GFP-Mss4 and GFP-Stt4 are false colored with LUT scale indicated in Fig. 4, A and D. Unless indicated otherwise, all error bars represent SD.

We developed two semi-automatic Matlab programs, BudPolarity (BP) and HyphalPolarity (HP), with an intuitive interface dedicated for the analyses of the intensity profile along the major axis of either yeast or hyphal form cells and its variations along time. For both, 3D images are converted into 2D images by sum projection. Yeast morphology is defined by user-defined intensity threshold. For BP, the straight axis is defined by the major axis of the ellipse fitting the morphology of the yeast. To compare profiles during bud’s growth, axis length has been normalized. Fluorescence intensity is integrated on this axis to follow concentration along this axis. The HP program was created for cells with nonlinear morphologies (i.e., curved). From the morphology image, the program defines membrane and cytoplasm regions (this is done manually and subcellular regions such as organelles can also be defined) and it extracts the best-suited “backbone.” This backbone is built from the longest set of elements of the skeletonized image (i.e., ultimate erosion of morphology image, but does not allow objects to break apart). Linear extrapolation of this set of elements is done to fully split the sample in two parts, i.e., left and right sides of this backbone. From this curved backbone, according to an elastic deformation model, the image of the uncurved yeast is created. Then, it integrates intensity perpendicularly to the yeast axis on its both sides. This results in two concentration profiles (one for each side of the backbone), which were used to confirm profile homogeneity, and the average of these two profiles was used. For the quantification of filaments, all graphs start with the portion of the cell in which the signal is constant. In addition, this program enabled determination of the average intensities of the PM and cytoplasm (defined as all signal interior to the PM). These values were determined from central optical section for each cell analyzed.

FRAP and FLIP experiments were performed essentially as described previously (Bassilana and Arkowitz, 2006; Vauchelles et al., 2010), with images captured every second at 1% maximum laser intensity. Bleaching was performed at 100% laser intensity using 10 × 0.6-ms photobleaching scans on a circular area of 0.6 µm2 that was used for all FRAP experiments. For FRAP studies typically, bud or hyphal tips were photobleached and for FLIP studies either the entire mother or bud was photobleached. The average intensity (I) of the bleached or unbleached area was normalized (Phair et al., 2004) for photobleaching during image acquisition, using the average intensity of the cell with Matlab. Regression analysis to determine the FRAP t1/2 was done using a one-phase exponential association function in Matlab, as follows: Inorm(t) = Ibleach + (Iprebleach – Ibleach)(1 − exp[−kt]), where k is the rate constant and t1/2 is 0.69/k.

To calculate apparent diffusion coefficient, we used the following equation: D = (ω2/4t1/2)γD, where ω is the radius of the bleach ROI, t1/2 is the time to half-maximal recovery, and γD a constant equal to 0.88 for uniform circular photobleaching (Axelrod et al., 1976).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the reduced levels of the phosphoinositide phosphate kinases in the respective stt4 and mss4 mutants and their invasive filamentous growth defects. Fig. S2 illustrates the PI(4,5)P2 gradients in filamentous cells described in Fig. 4. Fig. S3 shows the effects of depleting Stt4p and disrupting the actin cytoskeleton on the PI(4,5)P2 distribution in budding cells described in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. Fig. S4 shows the disruption of the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons described in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively, and the localization of GFP-Mss4 in the she3 mutant. Fig. S5 shows the dynamics of PI(4,5)P2 in budding and filamentous cells using FRAP and FLIP approaches. Table S1 indicates the yeast strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201203099/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Berman, N. Dean, S. Emr, A. Johnson, H. Nakayama, and Y. Wang for reagents; and D. Stone, F. Besse, and S. Munro for comments on the manuscript. We thank J. Hopkins, A. Oprea, R. Conde, and M. Brulin for assistance.

This work was supported by the CNRS, FRM-BNP-Paribas, an ANR-09-BLAN-0299-01 grant and an ARC 4979 grant.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- BP

- BudPolarity

- Dox

- doxycycline

- HP

- HyphalPolarity

- LatA

- latrunculin A

- MT

- microtubule

- ni.ex.

- number of independent experiments in which similar results are observed

- Noc

- nocodazole

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- PM

- plasma membrane

- ts

- temperature sensitive

- wt

- wild type

References

- Audhya A., Emr S.D. 2002. Stt4 PI 4-kinase localizes to the plasma membrane and functions in the Pkc1-mediated MAP kinase cascade. Dev. Cell. 2:593–605 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00168-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya A., Emr S.D. 2003. Regulation of PI4,5P2 synthesis by nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of the Mss4 lipid kinase. EMBO J. 22:4223–4236 10.1093/emboj/cdg397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya A., Foti M., Emr S.D. 2000. Distinct roles for the yeast phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases, Stt4p and Pik1p, in secretion, cell growth, and organelle membrane dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2673–2689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D., Koppel D.E., Schlessinger J., Elson E., Webb W.W. 1976. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16:1055–1069 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85755-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrane H., Nguyen M.H., Cheng S., Kumar V., Derendorf H., Iczkowski K.A., Clancy C.J. 2008. The Candida albicans phosphatase Inp51p interacts with the EH domain protein Irs4p, regulates phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate levels and influences hyphal formation, the cell integrity pathway and virulence. Microbiology. 154:3296–3308 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018002-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird D., Stefan C., Audhya A., Weys S., Emr S.D. 2008. Assembly of the PtdIns 4-kinase Stt4 complex at the plasma membrane requires Ypp1 and Efr3. J. Cell Biol. 183:1061–1074 10.1083/jcb.200804003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y., Mermall V., Mooseker M.S., Snyder M. 2000. Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintenance of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell. 5:841–851 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80324-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassilana M., Arkowitz R.A. 2006. Rac1 and Cdc42 have different roles in Candida albicans development. Eukaryot. Cell. 5:321–329 10.1128/EC.5.2.321-329.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassilana M., Hopkins J., Arkowitz R.A. 2005. Regulation of the Cdc42/Cdc24 GTPase module during Candida albicans hyphal growth. Eukaryot. Cell. 4:588–603 10.1128/EC.4.3.588-603.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin A., McMurray M.A., Thai L., Garcia G., III, Votin V., Grob P., Allyn T., Thorner J., Nogales E. 2010. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. J. Mol. Biol. 404:711–731 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop A., Lane R., Beniston R., Chapa-y-Lazo B., Smythe C., Sudbery P. 2010. Hyphal growth in Candida albicans requires the phosphorylation of Sec2 by the Cdc28-Ccn1/Hgc1 kinase. EMBO J. 29:2930–2942 10.1038/emboj.2010.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S., Van Dijck P., Datta A. 2007. Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:348–376 10.1128/MMBR.00009-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamayor A., Snyder M. 2003. Molecular dissection of a yeast septin: distinct domains are required for septin interaction, localization, and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2762–2777 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2762-2777.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crampin H., Finley K., Gerami-Nejad M., Court H., Gale C., Berman J., Sudbery P. 2005. Candida albicans hyphae have a Spitzenkörper that is distinct from the polarisome found in yeast and pseudohyphae. J. Cell Sci. 118:2935–2947 10.1242/jcs.02414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler N.S., Heitman J., Cardenas M.E. 1997. STT4 is an essential phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase that is a target of wortmannin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 272:27671–27677 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos K.J., Sable J., Miller K.E., Sheetz M.P. 2003. Expression of phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate-specific pleckstrin homology domains alters direction but not the level of axonal transport of mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3636–3649 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrivières S., Cooke F.T., Parker P.J., Hall M.N. 1998. MSS4, a phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase required for organization of the actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15787–15793 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. 2006. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 443:651–657 10.1038/nature05185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere J., Barral Y. 2004. Spatial coordination of cytokinetic events by compartmentalization of the cell cortex. Science. 305:393–396 10.1126/science.1099892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sayegh T.Y., Arora P.D., Ling K., Laschinger C., Janmey P.A., Anderson R.A., McCulloch C.A. 2007. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5 bisphosphate produced by PIP5KIgamma regulates gelsolin, actin assembly, and adhesion strength of N-cadherin junctions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 18:3026–3038 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson S.L., Noble S.M., Solis N.V., Filler S.G., Johnson A.D. 2009. An RNA transport system in Candida albicans regulates hyphal morphology and invasive growth. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000664 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian L., Wei H.C., Rollins J., Noguchi T., Blankenship J.T., Bellamkonda K., Polevoy G., Gervais L., Guichet A., Fuller M.T., Brill J.A. 2010. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate directs spermatid cell polarity and exocyst localization in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:1546–1555 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairn G.D., Hermansson M., Somerharju P., Grinstein S. 2011. Phosphatidylserine is polarized and required for proper Cdc42 localization and for development of cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1424–1430 10.1038/ncb2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucherre A., Desbois P., Nagano F., Satre V., Lunardi J., Gacon G., Dorseuil O. 2005. Lowe syndrome protein Ocrl1 is translocated to membrane ruffles upon Rac GTPase activation: a new perspective on Lowe syndrome pathophysiology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:1441–1448 10.1093/hmg/ddi153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fooksman D.R., Shaikh S.R., Boyle S., Edidin M. 2009. Cutting edge: phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate concentration at the APC side of the immunological synapse is required for effector T cell function. J. Immunol. 182:5179–5182 10.4049/jimmunol.0801797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly S., Singh P., Manoharlal R., Prasad R., Chattopadhyay A. 2009. Differential dynamics of membrane proteins in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387:661–665 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrenton L.S., Stefan C.J., McMurray M.A., Emr S.D., Thorner J. 2010. Pheromone-induced anisotropy in yeast plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate distribution is required for MAPK signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:11805–11810 10.1073/pnas.1005817107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerami-Nejad M., Berman J., Gale C.A. 2001. Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast. 18:859–864 10.1002/yea.738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiewska U., Nyako M., Woturski W., Zaitseva I., McLaughlin S. 2008. Diffusion coefficient of fluorescent phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in the plasma membrane of cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:1663–1669 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiewska U., Kay J.G., Masters T., Grinstein S., Im W., Pastor R.W., Scarlata S., McLaughlin S. 2011. Evidence for a fence that impedes the diffusion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate out of the forming phagosomes of macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22:3498–3507 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hairfield M.L., Westwater C., Dolan J.W. 2002. Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase activity is stimulated during temperature-induced morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 148:1737–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G.R., Sim Y., Lagnado L., Irvine R.F. 2009. Reversible binding and rapid diffusion of proteins in complex with inositol lipids serves to coordinate free movement with spatial information. J. Cell Biol. 184:297–308 10.1083/jcb.200809073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan I., Liu H. 2002. Hyphal tip-associated localization of Cdc42 is F-actin dependent in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 1:856–864 10.1128/EC.1.6.856-864.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Xi F., Zhang X., Zhang J., Guo W. 2007. Exo70 interacts with phospholipids and mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 26:4053–4065 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann D.W. 2007. Local PIP2 signals: when, where, and how? Pflugers Arch. 455:55–67 10.1007/s00424-007-0280-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma K., Terui S., Minemura M., Qadota H., Anraku Y., Kanaho Y., Ohya Y. 1998. Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase localized on the plasma membrane is essential for yeast cell morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15779–15786 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]