Abstract

Background:

The incidence of Mycobacterium marinum infection has been increasing. First-line antituberculous drugs and other common antibiotics are effective for most cutaneous M. marinum infections; however, treatment failure still occurs in some rare cases. We report a case of a 70-year-old man with refractory cutaneous infection caused by M. marinum. Reasons for delayed diagnosis and related factors of the refractory infection are also discussed.

Methods:

Samples of lesional skin were inoculated on Löwenstein–Jensen medium for acid-fast bacilli. Species of mycobacterium were identified by polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis. We then carried out genotyping by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units and sequencing of heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) and 16S rDNA genes.

Results:

Tissue cultures for acid-fast bacilli were positive. PCR-RFLP analysis and sequencing of hsp65 and 16S rDNA genes confirmed the isolated organisms to be M. marinum. Systemic therapy with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and amikacin empirically over 6 months led to complete resolution of skin lesions leaving only some residual scars.

Conclusion:

Key diagnostic elements for M. marinum infections include a high index of suspicion raised by chronic lesions, poor response to conventional treatments, and a history of fish-related exposure. Strong clinical suggestion of M. marinum infection warrants initial empirical treatment. The duration of therapy is usually several months or even longer, especially for elderly patients. Amikacin can be considered in multidrug therapy for treatment of some refractory M. marinum infections.

Keywords: amikacin, clarithromycin, skin infection, Mycobacterium marinum, nontuberculous mycobacteria

Introduction

Mycobacterium marinum, a slow-growing mycobacterium, is considered the most common cause of mycobacterial skin infections. The overall incidence is estimated to be 0.27 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and this number has increased in recent years.1 Although mycobacterial infections are more prevalent in immunocompromised patients, immunocompetent individuals have sometimes been affected. In general, first-line antituberculous drugs and other common antibiotics in monotherapy or multidrug regimens are effective against almost all cutaneous M. marinum infections. However, treatment failure still occurs in less than 20% of cases.1–5 Here, we report a case of a 70-year-old fish tank hobbyist with a refractory cutaneous infection caused by M. marinum who was cured after long-term treatment with clarithromycin, rifampicin, and amikacin. Reasons for delayed diagnosis and therapy recommendations are also reviewed.

A 70-year-old man presented with a 10-month history of deep erythemas, subcutaneous nodules, and skin ulcers on the right upper limb and a 2-month history of ache and tumidness. These lesions had initially appeared 1 month prior as an isolated indolent nodule on the right wrist after a minor laceration to the second digit of his right hand, which was his dominant hand. As the disease progressed, the primary nodule enlarged and multiple nodules developed in an ascending fashion along the path of lymphatic drainage. A skin biopsy of a nodule performed at a local hospital showed infectious granuloma formation with acid-fast bacilli (AFB) identified within the tissue. Routine histopathology examination was repeated 1 month later, and this also produced an infectious granuloma reaction. Tissue cultures indicated that Sporotrichum schenckii could be growing in diseased tissues. The patient was diagnosed with sporotrichosis and prescribed orally administered potassium iodide and itraconazole. After 3 months of treatment, the lesions improved but had not completely healed. At this point, the patient topically applied a nonprescription Chinese herbal preparation, which exacerbated the skin lesions; these became swollen, red, and intensely painful on the whole right upper limb with ulceration of even the partial lesions. The patient was advised to continue antifungal treatment with terbinafine, itraconazole, and potassium iodide for several months. Fresh nodules and erosive papules developed on the dorsum of the right hand during the treatment, followed by diffuse tumidness with deep ulceration. In April 2011 after 8 months of no significant therapeutic effects with antifungal treatment, the patient was transferred to our hospital. Another two biopsies were re-examined before admission, and consistent results were obtained that exhibited granulomatous changes. All special stains, including AFB stains, and tissue cultures were negative for infectious organisms. Since the onset of the disease, the patient did not complain of systemic discomfort. He was in good general condition and did not have a history of hepatitis or tuberculosis. He had not travelled abroad but reported having a fish tank at home.

Dermatological examination revealed a large area of deep erythema and edema with nodules, ulcerations, and crusts on the right upper limb that was abnormally sensitive to the touch. He had a nummular deep ulcer with severe tenderness on the dorsum of the second digit, which limited movement (Figure 1A and B). No axillary lymph node was palpable.

Figure 1.

Skin lesions. (A and B) Before treatment a large area of immersed erythema and edema with nodules, ulcerations, and crusts scattered on the right upper limb was present. A nummular deep ulcer with a severe tenderness presented on the back side of the second digit. (C and D) After 2 months of therapy the skin nodules decreased in size and the ulcer cavity was filled with fresh tissues. (E and F) After 6 months of therapy the lesions subsided, leaving some hyperplastic scars.

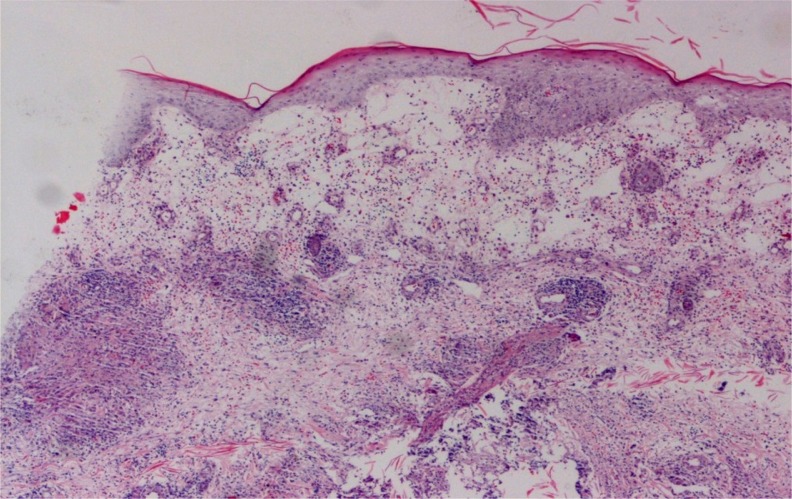

Routine laboratory analysis demonstrated mild anemia and hypoproteinemia. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody test indicated negative results, and no active pulmonary disease was detected by chest radiography. A skin biopsy of a nodule on the patient’s right forearm displayed a neutrophilic and histiocytic granuloma, with no caseous necrosis. Multinucleated giant cells were also observed (Figure 2). All special stains, including AFB and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains, were negative for infectious organisms. Tissue cultures showed that the colonies grew on Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium at 32°C for 10 days (Figure 3). Fungal and other standard bacterial cultures were negative.

Figure 2.

Pathological changes.

Note: A neutrophilic and histiocytic granuloma (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification ×400).

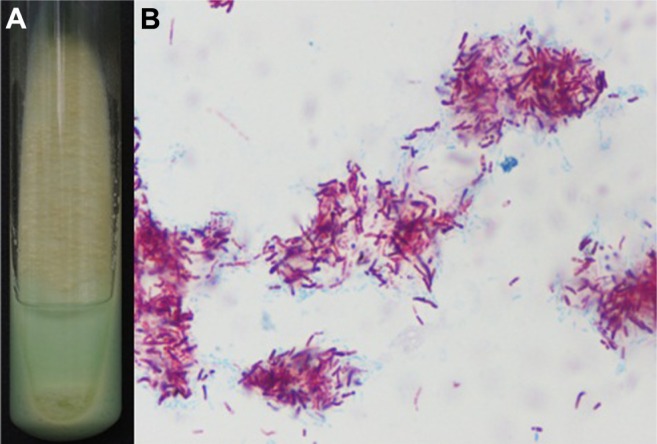

Figure 3.

Pathogenic organism. (A) Mycobacterial cultures from the isolated lesional skin. (B) Smear from the cultured organisms with acid-fast stain.

After identifying a nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection based upon the positive tissue cultures, certain species of NTM were suspected. M. marinum, a relatively common cause of mycobacterial skin infection that can spread in a sporotrichoid manner, was the first to be considered.2 The patient was then treated with orally administered rifampicin (450 mg, once daily), clarithromycin (500 mg, twice daily), and moxifloxacin (400 mg, once daily) for 4 weeks. However, the right upper limb became swollen again, with purulent secretions draining from the ulcer, and new lesions appeared during the treatment.

Because the aggressive infection progressed so rapidly that multiple ulcers resistant to the combined therapy presented one after another, M. ulcerans infection was also suspected. The therapeutic regimen was then altered with the addition of intravenous amikacin (400 mg, once daily) to the antimicrobial regimen and suspension of moxifloxacin. Surprisingly, the skin nodules rapidly decreased in size, and ulcer cavities had fresh tissue within several weeks (Figure 1C and D). The organism was subsequently identified as M. marinum, sensitive to clarithromycin, rifampin, moxifloxacin, and amikacin, and all the four drugs were consistent with the prescribed regimen. With close surveillance of liver and kidney function and other side effects of amikacin, the combined antibiotics were used consistently for 6 months. After this period, the lesions had significantly subsided, leaving hyperplastic and atrophic scars, and new nodules did not recur (Figure 1E and F). A skin biopsy and culture taken at this stage were negative for AFB.

Materials and methods

Identification of mycobacterial isolate

Samples of lesional skin were inoculated on LJ medium and incubated separately at 32°C and 37°C. The ability to grow at different temperatures (25°C and 45°C) and the possible production of pigmentation were tested on the isolated strain. Ziehl–Neelsen staining was used to confirm whether or not the cultured organisms were AFB. In vitro drug susceptibility testing was carried out on the isolated strain by using the microtiter plate method in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines.6

Preparation of template DNA

One loop of bacteria on an LJ medium slope was harvested and suspended in 2 mL of sterile distilled water. Samples were then frozen in liquid nitrogen and transferred to boiling water five times to release mycobacterial DNA. After centrifugation to pellet insoluble debris, the supernatant was used as the DNA template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism and gene sequencing

The infecting strain was identified by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) gene (common to all mycobacteria) as described by Telenti et al.7 The data were analyzed by comparing results to an RFLP database (http://app.chuv.ch/prasite.html).8 The PCR products of the hsp65 and 16S RNA genes were sequenced, and the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) program was used to compare the sequences of the isolated strain with those of other mycobacterial species in GenBank.9

Genotyping by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units

The isolated strain was typed by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit (MIRUs), and locus-specific PCRs for the four more polymorphic loci (1, 5, 9, 33) were used to differentiate the isolated strain.10

Results

Moderate growth of smooth colonies was noted after 10 days of incubation at 32°C. Ziehl–Neelsen staining confirmed the cultured organisms to be AFB (Figure 3). The test of production of pigmentation showed that the isolated AFB was photochromagenic, belonging to Runyon’s group I.11 In vitro susceptibility testing by use of the absolute concentration method demonstrated that the isolated organism was sensitive to clarithromycin, rifampin, moxifloxacin, and amikacin.

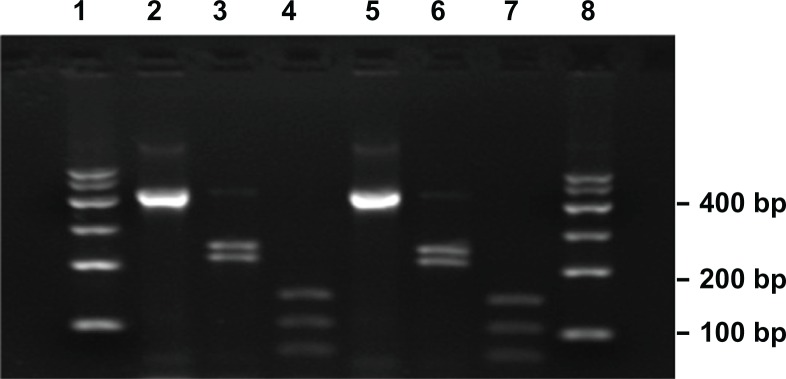

A fragment of 439 bp, encoding mycobacterial 65 kDa hsp, was amplified in the strain isolated from the patient. Digestion of the PCR product yielded two fragments of 245/220 bp with the restriction enzyme BstEII and three fragments of 160/115/80 bp with the restriction enzyme HaeIII (Figure 4). The RFLP pattern of the isolated AFB was identical with M. marinum. Sequencing of the hsp65 gene (439 bp) and 16s rDNA (1428 bp) showed 100% and 99% similarity, respectively, with M. marinum. Locus-specific PCRs for the four more polymorphic loci (1, 5, 9, 33) identified the isolated strain as a genotype [1-3-3-3] that was distinct from the profiles of other reported M. ulcerans.10

Figure 4.

Restriction analyses of the isolated strain amplification products.

Notes: Lanes 1 and 8, DNA size marker (100 bp ladder); lanes 2 and 5, undigested amplification products of the isolated strain and Mycobacterium marinum (439 bp); lanes 3 and 6, BstEII digestion of the isolated strain and M. marinum (245/220 bp); lanes 4 and 7, HaeIII digestion of the isolated strain and M. marinum (160/115/80 bp).

Discussion

M. marinum, a Runyon group I photochromogen, often causes skin infections by direct inoculation through broken skin after exposure to contaminated water in a swimming pool or fish tank; it has an incubation period ranging from 2 to 6 weeks.1,12,13 Fish-related infection cases are gradually increasing due to the popularity of rearing fish at home.14 Infection typically occurs on the dominant hand of fish fanciers, and this infection shows with a sporotrichoid distribution, in which nodules and ulcers spread proximally along the path of lymphatic drainage.2,15,16 Further examination of our patient’s exposure history revealed that he was a right-handed fish fancier and most likely to have been in contact with the organisms in conducting his hobbies associated with fish. As the lesions were suddenly exacerbated right after he topically applied a nonprescription Chinese herbal preparation, it cannot be excluded that the Chinese herbs contained the organisms.

Typical histologic changes are numerous well-formed infectious granulomas.17 In less than 50% of cases, acid-fast organisms are detectable in the biopsy sections.5,14 In our patient, skin biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation with negative results for AFB stains on multiple occasions except the first time. The possibility of a positive result in the biopsy sections may be associated with the course of infection.

Tissue cultures are of particular value in separating NTM from other organisms if specimens are cultured in the appropriate manner. Approximately 90% of cases show positive culture results.5,18 Even so, diagnosis is frequently delayed for weeks or even years. As shown in our patient, the diagnosis was not made until 10 months after initial presentation. The determination of the correct diagnosis remained challenging because the patient presented with sporotrichoid lesions and S. schenckii infection was suggested according to the culture results in the early stage. However, M. marinum infection should have been considered earlier in the course of his disease, especially when re-examined skin biopsies and fungal cultures showed negative results. The reasons for the delayed diagnosis included ignorance of fish-related exposure history, atypical manifestations caused by inappropriate therapies, negative results of cultures due to inappropriate cultivation, and low awareness of mycobacterial skin infection among the clinicians because of its rarity in everyday dermatological practice.

Before the results of species identification and drug susceptibility were available, we empirically treated our patient with rifampicin, clarithromycin, and moxifloxacin as recommended regimen for M. marinum infection.1,3–5,19 With a view to the relatively aggressive clinical course, M. ulcerans was also suspected for which a combined regime of rifampin and amikacin is effective.19,20 In light of these claims, we replaced moxifloxacin with amikacin, accompanied with close surveillance of liver and kidney function and other side effects of amikacin. Although species identification revealed the isolated strain to be M. marinum, in vitro drug susceptibility testing showed the isolated organism was also sensitive to amikacin, and therefore the therapeutic regimen was continued. Interestingly, skin eruptions regressed significantly after 6 months of combined therapy, but the dosage of amikacin (8 mg/kg) was relatively lower than recommendation (15 mg/kg) in consideration of the age of the patient.21

In contrast to clarithromycin, a bacteriostatic inhibitor of microbial protein synthesis, amikacin belongs to the aminoglycosides and is a bactericidal inhibitor of protein synthesis.21 Although it presents activity against M. marinum and has been identified as one of the most active drugs in some in vitro studies, amikacin is not routinely used for M. marinum infection, probably because it can only be administered by injection and is not available for oral administration.20,22,23 The recommended dose of amikacin is 15 mg/kg per day as a single daily dose. Numerous studies have demonstrated that once-daily regimens are as safe or safer than multiple-dose regimens with equal efficacy.21 For older patients or patients who require long-term parenteral therapy, less frequent dosing (eg, every 48 hours) is more appropriate. Some experts recommend that a dose of 8–10 mg/kg two to three times weekly may be necessary, with a maximum dose of 500 mg for patients older than 50 years.19 It is recommended that patients receiving aminoglycosides should be monitored carefully for toxicity, most notably nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, particularly when using for prolonged periods. In addition, aminoglycosides generally should not be used as single agents because of relatively poor tissue penetration and poorer outcomes associated with aminoglycoside monotherapy.21 Our case represented a successful example of treatment with a multiple drug regimen that included rifampin and clarithromycin; additional amikacin can eliminate M. marinum infection with a duration of up to 6 months. These drugs might act synergistically through suppressing mycobacteria RNA synthesis by rifampin and inhibiting protein synthesis by clarithromycin and amikacin.

Generally, strains of M. marinum are susceptible to first-line antituberculous drugs and other common antibiotics, and monotherapy can even eliminate cutaneous infections successfully. Treatment failure is found to be related to deep structure involvement or inappropriate therapies, such as corticosteroid use.1,5 What confused us was the obstinacy of our patient’s localized infection with no significant improvement after 1 month of treatment with combined antibiotics, which the isolated strain were proven to be susceptible to by subsequent drug susceptibility tests. The refractory infection may be attributed to the following factors: (1) The long duration and stubborn symptoms of the case caused by the delayed diagnosis might have contributed to a poor clinical response; (2) the long-term use of inappropriate and irregular therapies, which led to a procrastinated course of infection, might be a risk factor for treatment failure; (3) the age of our patient. Evidence is lacking to show that age is a risk factor for treatment failure because of the scarcity of cases. However, elderly people are more or less immunocompromised, so the response to treatment might be slower.

Conclusion

The purpose of this work was to improve the diagnosis and share the experience in treatment of cutaneous M. marinum infection. When evaluating a patient with evolving subcutaneous nodules, plaques, and ulcerations, especially when there is sporotrichoid spread after trauma but no responses to antifungal agents, the occupation and hobbies of the patient should be considered. A history of fish-related exposure is highly suggestive of M. marinum, and a biopsy and tissue culture of mycobacteria should be requested. As a long period is needed to accurately identify mycobacterial species and receive results of in vitro drug susceptibility testing, a strong clinical suggestion of M. marinum infection warrants initial empirical treatment. The total duration of therapy depends on the patient’s clinical evolution (usually several months). When managing elderly patients with no responses to recommended agents, amikacin might be a good choice for multidrug therapy in a relatively low dosage, and the duration should be prolonged with close surveillance of the side effects.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30972651); Natural Funds of Jiangsu Health Office, PR China (H200638); the special fund for basic research and development of Chinese national scientific research institutes; and the fund for the Key Clinical Program of the Ministry of Health (2010-2012-125). We thank all the medical workers in the ward of our hospital for their cooperation and clinical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, Robert J, Cambau E. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1746–1752. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gluckman SJ. Mycobacterium marinum. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(3):273–276. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner D, Young LS. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical review. Infection. 2004;32(5):257–270. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodiuk-Gad R, Dyachenko P, Ziv M, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: A retrospective study of 25 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(3):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Xu H, Wang H, Zhang C, Zong W, Wu Q. Outbreak of a cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection in Jiangsu Haian, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71(3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards . Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardiae, and Other Aerobic Actinomycetes; Approved Standard. N24-A. 18. Vol. 23. Wayne, PA: NCCLS; 2003. Available from: http://130.185.73.107:60/2/M24-A.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Bottger EC, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(2):175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ena P, Sechi LA, Saccabusi S, et al. Rapid identification of cutaneous infections by nontubercular mycobacteria by polymerase chain reaction-restriction analysis length polymorphism of the hsp65 gene. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40(8):495–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kox LF, van Leeuwen J, Knijper S, Jansen HM, Kolk AH. PCR assay based on DNA coding for 16S rRNA for detection and identification of mycobacteria in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(12):3225–3233. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3225-3233.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stragier P, Ablordey A, Meyers WM, Portaels F. Genotyping Mycobacterium ulcerans and Mycobacterium marinum by using mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):1639–1647. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1639-1647.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runyon E. Anonymous mycobacteria in pulmonary disease. Med Clin North Am. 1959;43:273–290. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)34193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aubry A, Jarlier V, Escolano S, Truffot-Pernot C, Cambau E. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Mycobacterium marinum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(11):3133–3136. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3133-3136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norden A, Linell F. A new type of pathogenic mycobacterium. Nature. 1951;168:826. doi: 10.1038/168826a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(5):343–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(6):491–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25(10):609–613. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philpott JJ, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, Schaefer WB, Mollohan CS. Swimming pool granuloma. A study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158–162. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1963.01590200046008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huminer D, Pitlik SD, Block C, Kaufman L, Amit S, Rosenfeld JB. Aquarium-borne Mycobacterium marinum skin infection. Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(6):698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esteban J, Ortiz-Perez A. Current treatment of atypical mycobacteriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(17):2787–2799. doi: 10.1517/14656560903369363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers HF. Aminoglycosides. In: Laurence L, Lazo John S, Keith L, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arai H, Nakajima H, Kaminaga Y. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium marinum to dihydromycoplanecin A and ten other antimicrobial agents. J Dermatol. 1990;17(6):370–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1990.tb01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders WJ, Wolinsky E. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium marinum to eight antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18(4):529–531. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]