Abstract

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the lung fluke, Paragonimus spp. Lung flukes may be found in various organs, such as the brain, peritoneum, subcutaneous tissues, and retroperitoneum, other than the lungs. Abdominal paragonimiasis raises a considerable diagnostic challenge to clinicians, because it is uncommon and may be confused with other abdominopelvic inflammatory diseases, particularly peritoneal tuberculosis, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Also, subcutaneous paragonimiasis does not easily bring up clinical suspicion, due to its rarity. We herein report 2 cases of abdominal paragonimiasis and 1 case of subcutaneous paragonimiasis in Korea.

Keywords: Paragonimus sp., paragonimiasis, abdominal cavity, subcutaneous tissue

INTRODUCTION

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease, which is caused by the lung flukes of the trematode genus Paragonimus. Human infection occurs by ingestion of raw or incompletely cooked freshwater crab or crayfish infected with the metacercariae. As ranges of the freshwater crab and crayfish have been rapidly reduced, due to pollution of the water bodies with environmental waste, and the infection rate of fresh water crab and crayfish with metacercariae of Paragonimus westermani have been continuously decreased in Korea [1-3], cases of human paragonimiasis have been found in rare occasions. The lung flukes may be found in various organs, such as the brain, peritoneum, subcutaneous tissues, and retroperitoneum, other than the lungs. Abdominal paragonimiasis raises a considerable diagnostic challenge to clinicians, due to its uncommon nature and it may be confused with other abdominopelvic inflammatory diseases, particularly, peritoneal tuberculosis and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Moreover, subcutaneous paragonimiasis does not easily bring up clinical suspicion, due to its rarity. Here, we report 2 cases of abdominal paragonimiasis and 1 case of subcutaneous paragonimiasis, which we have experienced during the past 7 years.

CASES RECORD

Case 1

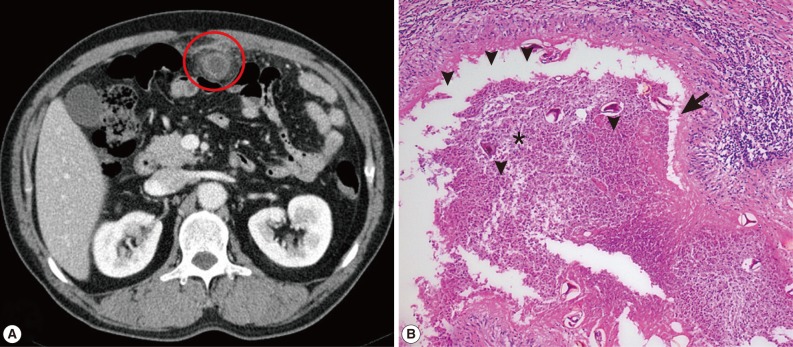

A 48-year-old man was referred to our emergency room for evaluation and treatment of 8-hr history of periumbilical pain and abdominal mass on local abdominal ultrasonograms. He had previously been healthy with no prior medical problems. At the time of admission (June, lived in Kunsan, Jeollabuk-do), body temperature was 37.8℃, and physical examination showed direct tenderness on the periumbilical area with no other specific findings. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 16,100/mm3 with no other abnormal laboratory findings. Chest X-ray was normal and abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a ring-shaped mass lesion, with focal irregular enhancement in the omentum (Fig. 1A). We suspected non-specific intra-abdominal abscess and performed exploratory laparotomy. During the surgery, a 3×2 cm sized mass was recognized in the omentum. Omentectomy for the omental abscess and adjacent small bowel resection were done. Microscopic pathologic examinations revealed the eggs of P. westermani scattered with acute suppurative inflammation and foreign body-type giant cells (Fig. 1B). A retrospective history taking showed that he had frequently consumed 'Kejang' (drunken crab), which was prepared using freshwater crabs. The treatment decided for the patient was praziquantel (25 mg/kg, 3 times daily for 2 days), and the patient recovered uneventfully.

Fig. 1.

CT and microscopic findings of omental paragonimiasis. (A) Abdominal CT showed ring-shaped mass lesion with focal irregular enhancement in the omentum (red circle). (B) Microscopic pathologic examinations revealed the eggs of P. westermani (arrowheads) scattered with acute suppurative inflammations (star) and foreign body-type giant cells (arrow). H&E stain, ×100.

Case 2

A 57-year-old woman visited our hospital to seek treatment of transverse colon cancer (October, lived in Gunsan, Jeollabuk-do). Her vital sign was stable and laboratory findings revealed no abnormalities with normal eosinophil count and normal carcinoembryonic antigen, except anemia (hemoglobin; 9.6 g/dl). The preoperative abdominal CT showed circumferential wall thickening of the proximal transverse colon with adjacent fatty infiltrations. Intraoperative findings showed a small whitish nodule on the omentum, which mimicked an omental seeding nodule. Intraoperative frozen biopsy revealed inflammatory benign lesions. Curative extended right hemicolectomy was performed. Pathologic reports confirmed that there were numerous eggs of P. westermani in the fibrotic and collagenous background on the omentum. She could not recall any history of consuming freshwater crabs or crayfish in the past. She was treated with praziquantel (25 mg/kg, 3 times daily for 2 days), and had recovered uneventfully.

Case 3

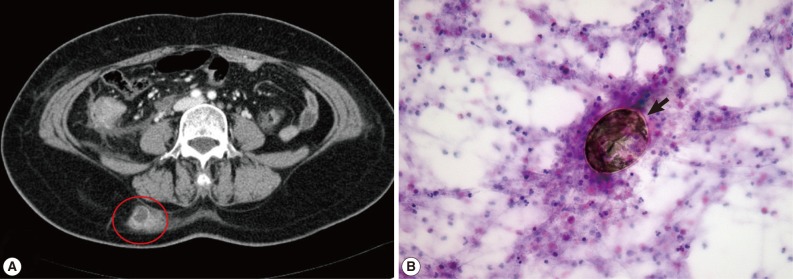

A 58-year-old woman visited our hospital for evaluation and treatment of the right flank pain over 4 days (August, lived in Namwon, Jeollabuk-do). Her vital sign was stable and physical examination revealed no specific signs. Laboratory findings showed no abnormalities, except eosinophilia (14.6%). Abdominal CT revealed localized abscess in the subcutaneous layer of the right back (Fig. 2A). Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) showed the eggs of P. westermani with eosinophil-dominant inflammatory cells (Fig. 2B). ELISA (performed at Seoul Medical Institute) was positive for antibodies against P. westermani in the serum (0.69). Retrospective history results revealed that she had frequently consumed 'Kejang', which was prepared using freshwater crabs. On the basis of these findings, she was treated with praziquantel (25 mg/kg, 3 times daily for 2 days) and her right flank pain was resolved after treatment.

Fig. 2.

CT and microscopic findings of subcutaneous paragonimiasis. (A) CT scan shows localized abscess in the right back (red circle). (B) Fine needle aspiration cytology showed eggs of P. westermani (arrow) with eosinophil-dominant inflammatory cells. The eggs of P. westermani were yellowish-brown, ovoid or elongate, with a thick shell, and often asymmetrical with one end slightly flattened. H&E stain, ×400.

DISCUSSION

When P. westermani metacercariae infect man, they excyst in the duodenum, and then pass through the intestinal wall, peritoneal cavity, diaphragm, and pleural cavity to the lung parenchyma, where they mature to adult flukes [1]. Due to this migratory route, from the intestine to the lungs, ectopic infections can occur at unexpected locations, such as the brain, muscle, omentum, retroperitoneum, and subcutaneous tissues [1,4,5].

The prototype species, P. westermani, is distributed in Korea, Japan, China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. The major source of infection has been presumed to be soy-sauced freshwater crabs (Kejang), in South Korea. However, according to a recent study in South Korea, freshwater crabs may transmit the metacercariae only in rare occasions, and P. westermani metacerariae may be transmitted mainly by crayfish [3]. In our cases, 2 patients had a history of consumption of 'Kejang', but 1 patient could not recall any history of consuming freshwater crabs or crayfish.

The diagnosis of paragonimiasis can be made based on detection of characteristic eggs in the stool, tissues, sputum, or pleural fluid, like our cases. However, the detection procedures in the tissues may be invasive, especially in the abdominal cavity. Thus, ELISA is commonly used for the immunodiagnosis of paragonimiasis, as the overall sensitivity and specificity of the assay were reported to be 90.2% and 100%, respectively [1]. However, ELISA can be used only based on clinical suspicion, which should be made in cases of eosinophilia, with the history of consumption of freshwater crabs or crayfish. Abdominal paragonimiasis may be confused with other abdominopelvic inflammatory diseases, particularly peritoneal tuberculosis (mainly granuloma formation), and peritoneal carcinomatosis [6,7]. In this case, laparoscopic exploration and biopsy can be a useful diagnostic tool to distinguish the difference between abdominal paragonimiasis and peritoneal tuberculosis. In case of a peritoneal nodule, which is combined with cancer, just like our patient (case 2), frozen and permanent biopsy must be done to rule out other inflammatory diseases before decision making and treatment. Also, FNAC can show the eggs of P. westermani at the abscess in the subcutaneous tissue, like our patient (case 3), and can be used as a diagnostic tool [8].

References

- 1.Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1990;28(Suppl):79–102. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1990.28.suppl.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho SY, Kang SY, Kong Y, Yang HJ. Metacercarial infection of Paragonimus westermani in freshwater crabs sold in markers in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol. 1991;29:189–191. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1991.29.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim EM, Kim JL, Choi SI, Lee SH, Hong ST. Infection status of freshwater crabs and crayfish with metacercariae of Paragonimus wertermani in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:425–426. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SA, Lee SH, Ko SH, Kim JG, Park SY, Yoo JY, Nam HW, Ahn YB. A Case of incidentally diagnosed adrenal paragonimiasis. Endocrinol Metab. 2011;26:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho AR, Lee HR, Lee KS, Lee SE, Lee SY. A case of pulmonary paragonimiasis with involvement of the abdominal muscle in a 9-year-old girl. Korean J Parasitol. 2011;49:409–412. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee HJ, Choi YW, Kim SM, Lee TH, Im EH, Huh KC, Na MJ, Kang YW. Familial infestation of Paragonimus westermani with peritonitis and pleurisy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, Kim HJ, Lee JI, Kye BH, Oh SN, Jung CK, Kang WK, Kim JG, Oh ST. A case of intra-abdominal heterotopic paragonimiasis combined with rectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2010;26:157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han SY, Lee WH, Yu JS, Lee SR, An JY, Koh JH, Park Y. A case of pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis with a breast abscess as the ectopic site. Korean J Med. 2011;81:502–507. [Google Scholar]