Abstract

A 94-year-old female with end-stage renal disease presents with fever, fatigue, and hematochezia. She had previously resided in Hunan Province, China, and Myanmar, and she immigrated to Taiwan 30 years ago. Colonoscopy revealed a colonic ulcer. Biopsy of the colonic ulcer showed ulceration of the colonic mucosa, and many Paragonimus westermani-like eggs were noted. Serum IgG antibody levels showed strong reactivity with P. westermani excretory-secretory antigens by ELISA. Intestinal paragonimiasis was thus diagnosed according to the morphology of the eggs and serologic finding. After treatment with praziquantel, hematochezia resolved. The present case illustrates the extreme manifestations encountered in severe intestinal paragonimiasis.

Keywords: Paragonimus westermani, ectopic, colonic ulcer, hematochezia, praziquantel

INTRODUCTION

Paragonimiasis, a food-borne disease that is endemic in Asian, African, North American, and South American countries, is caused by Paragonimus, including prototypic species, Paragonimus westermani [1-4]. The infection is also known as the lung fluke disease or pulmonary distomiasis because this trematode normally infects the lungs of mammals [5]. Regardless of the species responsible for the infection, praziquantel is the drug of choice, and it has a high cure rate [6].

Although the first documented human infection in Taiwan was in a Portuguese traveler [1,2], paragonimiasis is currently very rare on the island [7,8]. We report here a rare case manifestation of ectopic intestinal paragonimiasis with colonic ulcer and hematochezia in an elderly Taiwanese woman.

CASE REPORT

A 94-year-old female patient with hypertension, senile dementia, and chronic glomerulonephritis has been receiving maintenance hemodialysis in a hospital for 1 year and lived in the nursing home nearby. She was born in Hunan Province, China and lived there until the age of 30 years. Then, she moved to Myanmar and lived there for 34 years, before immigrating to Taiwan at the age of 64 years old. She reported no other foreign travel history since living in Taiwan. During her residence in mainland China and Myanmar, she had eaten raw freshwater crabs from nearby lakes or wine-soaked freshwater crabs occasionally made by herself. After immigration to Taiwan, she stopped this practice due to successful promotion of public health education.

The patient presented with fever, fatigue, and malaise for 1 day. Pyuria was present. She was diagnosed with urinary tract infection and treated with intravenous levofloxacine. However, a low grade fever persisted. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the onset of massive hematochezia was noted after session of hemodialysis, during which only heparin was used to rinse the dialyzer. She did not have coffee ground nasogastric tube drainage, vomiting, abdominal pain, or hemodynamic unstability. Lower gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage induced by use of heparin was suspected. After shifting to heparin-free hemodialysis, hematochezia persisted. Colonoscopy showed an ulcer with blood clot adherence at 25 cm from the anal verge (Fig. 1A). Edematous and hyperemic mucosa was present around the ulcer. Biopsy of the ulcer revealed ulceration, necrosis, mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, and granulation tissue formation in the colonic mucosa.

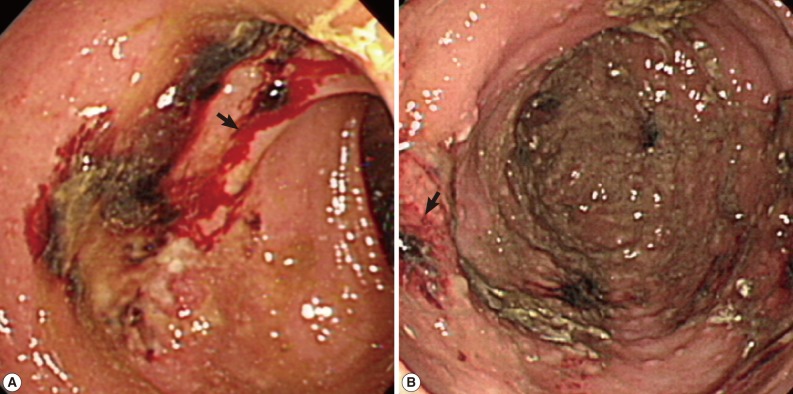

Fig. 1.

(A) A colonoscopy finding that shows an ulcer with blood clot adherence at 25 cm (arrow) from the anal verge. (B) The healed ulcer remained present with some hyperemic mucosa (arrow) around the site of the previous lesion.

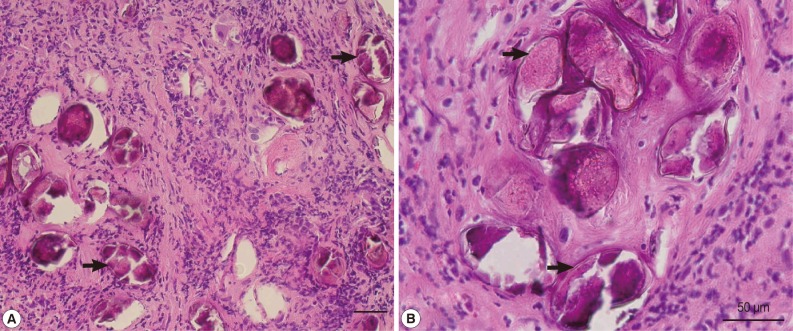

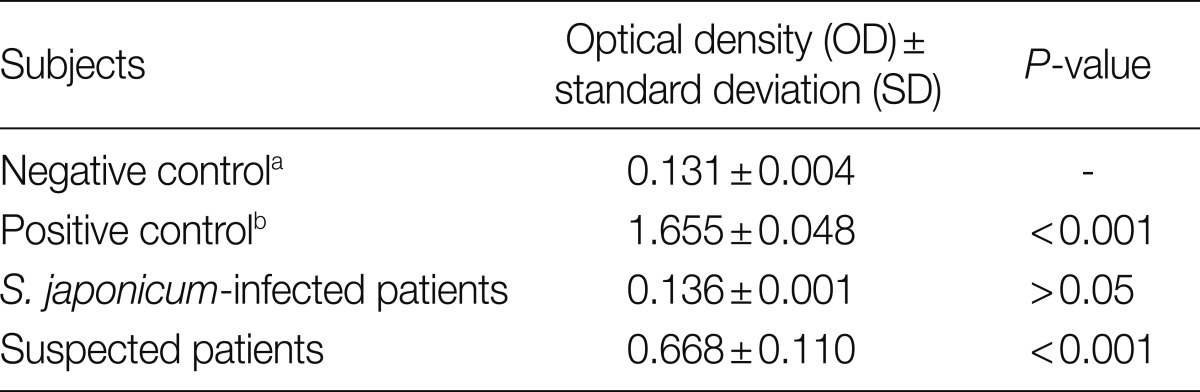

Many helminth eggs with surrounding fibrosis were noted (Fig. 2A), some of which measured around 85 µm in length (Fig. 2B) with morphologic characteristics consistent with P. westermani eggs. Further serodiagnosis indicated that the optical density (OD) values±SD from normal uninfected subjects (negative controls), P. westermani-infected patients (positive controls), Schistosoma japonicum-infected patients, and the present case were 0.131±0.004, 1.655±0.048, 0.136±0.001, and 0.668±0.110, respectively, as assessed by detection of serum IgG antibodies reactive with P. westermani excretory-secretory antigen (PWESA)-based ELISA kit (donated by Dr. Nara, Juntendo University, Japan) (Table 1). According to a method suggested by Richardson et al. [9] and Tijssen [10], sera from subjects whose mean OD values were greater than or equal to the mean OD value+2, 3, or 4 SDs of the negative control subjects were considered to be statistically significant (P<0.05, P<0.01, or P<0.001, respectively). Based on the above findings, colonic paragonimiasis could be diagnosed. Thereafter, treatment with praziquantel (75 mg/kg) in 3 divided doses per day was given in 3 days. Then, hematochezia resolved. The patient did not have chronic cough, hemoptysis, or chest pain before or after the treatment. Two weeks later, heparin was used during hemodialysis and there was no more hematochezia noted. Colonoscopy was repeated 1 month later, indicating the ulcer healed, but there was still some hyperemic mucosa around the site of the previous lesion (Fig. 1B). Follow-up of chest X-ray also showed largely normal findings (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A) A histopathological section showing many helminth eggs deposited in the submucosa of the patient with minimal inflammatory reactions. Paragonimus westermani-like eggs (arrows) are found. Scale bar=50 µm. (B) Higher magnification of P. westermani-like eggs (arrows) in the submucosa. Scale bar=50 µm.

Table 1.

Serum IgG antibody levels reactive to adult Paragonimus westermani excretory-secretory antigens from uninfected normal subjects, P. westermani-infected patients, Schistosoma japonicum-infected patients, and suspected patients as assessed by ELISA

aUninfected normal subjects.

bP. westermani-infected patients.

DISCUSSION

Human paragonimiasis is usually caused by ingestion of raw or undercooked crustaceans that contain infective metacercariae. Therefore, it is more prevalent in areas where eating raw crabs or crayfish exists as culture or folk medicine, such as China, Korea, Japan, and the Philippines [1-6]. However, paragonimiasis is currently very rare in Taiwan [7]. Only sporadic reports of paragonimiasis occur in Taiwan from elderly populations that immigrated from China [8]. According to her past consumption habits, it is highly probable that she acquired the P. westermani infection through ingestion of raw or wine-soaked freshwater crabs in mainland China or Myanmar. Nevertheless, S. japonicum infection should be ruled out because Schistosoma japonicum is still endemic in Hunan Province in mainland China [11]. Serum IgG antibodies from this case showed significantly strong reactivity to PWESA whereas the sera of S. japonicum-infected patients were not reactive to PWESA. Therefore, the possibility for this patient to be S. japonicum infection could be excluded.

In addition, eggs in the tissue sections measured around 85 µm in length which seemed also a supporting evidence to exclude the possibility of S. japonicum eggs; the average length of S. japonicum eggs exceeds 100 µm. Moreover, we performed a PCR assay to detect any presence of P. westermani or S. japonicum DNA from paraffin-embedded tissue several times by using specific primers, with negative results in all tests (data not shown). However, based on the patient's history of raw or wine-soaked freshwater crab consumption, morphologic characteristics of eggs in the inflamed tissue sections, and serologic evidence, the present case was diagnosed as P. westermani infection.

Symptoms of acute paragonimiasis usually occur 2-15 days after ingestion of the infection source when metacercariae are under migration from the gastrointestinal tract through the abdominal cavity and to the pleural cavity. The early syndromes include abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea. Chronic pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis usually presents as chronic cough, blood-tinged sputum or hemoptysis, dypnea, and pleuritic chest pain that worsens after physical exertion [5,6]. Ectpoic paragonimiasis may involve the central nervous system, subcutaneous tissues, urinary tract, liver, pericardium, and gastrointestinal tract [1,2]. Until recently, there is limited documentation of colonoscopic findings of intestinal paragonimiasis [12]. Intestinal paragonimiasis usually manifests as dull abdominal pain and diarrhea without eggs passing in the stool [13]. It is usually mild and self-limiting and rarely reported as cases of paragonimiasis separately [2]. However, ectopic paragonimiasis presenting as a colonic ulcer with massive hematochezia had not been documented. Factors that possibly attribute to the formation of colonic ulcers in paragonimiasis as in this patient include altered immune status with uremia and frequent use of anticoagulant during hemodialysis session. However, the exact mechanism of the formation of colonic ulcer and massive intestinal hemorrhage in this patient is unclear. Furthermore, the underlying mechanism of colonic ulcer caused by chronic intestinal paragonimiasis is also unclear. A possible explanation would be that long-term usage of immunosupressive drugs in the treatment of chronic glomerulonephritis leads to compromised immune functions so as to cause the colon ulcer [13].

As intestinal hemorrhage and colonic ulceration resolved after treatment with praziquantel in addition to the serologic evidence, paragonimiasis is evident in the present case. This case illustrates the extreme manifestations and endoscopic findings of severe intestinal paragonimiasis. It also reminds us that parasitic infections should be considered in elderly patients who had resided in endemic areas.

References

- 1.Procop GW. North American paragonimiasis (caused by Paragonimus kellicotti) in the context of global paragonimiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:415–446. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00005-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q, Wei F, Liu W, Yang S, Zhang X. Paragonimiasis: An important food-borne zoonosis in China. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nawa Y. Re-emergence of paragonimiasis. Intern Med. 2000;39:353–354. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim EM, Kim JL, Choi SI, Lee SH, Hong ST. Infection status of freshwater crabs and crayfish with metacercariae of Paragonimus westermani in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:425–426. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TS, Han J, Shim SS, Jeon K, Koh WJ, Lee I, Lee KS, Kwon OJ. Pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis: CT findings in 31 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:616–621. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shim SS, Kim Y, Lee JK, Lee JH, Song DE. Pleuropulmonary and abdominal paragonimiasis: CT and ultrasound findings. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:403–410. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30366021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JC. The prevalence of Paragonimus westermani in Taipei County. Zhonghua Min Guo Wei Sheng Wu Ji Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1986;19:302–306. (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SC, Jwo SC, Hwang KP, Lee N, Shieh WB. Discovery of encysted Paragonimus westermani eggs in the omentum of an asymptomatic elderly woman. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:615–618. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson MD, Turner A, Warnock DW, Llewellyn PA. Computer-assisted rapid enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the serological diagnosis of aspergillosis. J Immunol Methods. 1983;56:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tijssen P. Practice and Theory of Enzyme Immunoassays. Amsterdam, Netherland: Elsevier; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CW, Chung WJ, Kwon YL, Kim YJ, Kim ES, Jang BK, Park KS, Cho KB, Hwang JS, Kwon JH. Consecutive extrapulmonary paragonimiasis involving liver and colon. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:186–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itoh M, Sato S. Multi-dot enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serodiagnosis of trematodiasis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1990;21:471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ardelean DS, Gonska T, Wires S, Cutz E, Griffiths A, Harvey E, Tse SM, Benseler SM. Severe ulcerative colitis after rituximab therapy. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e243–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]