Abstract

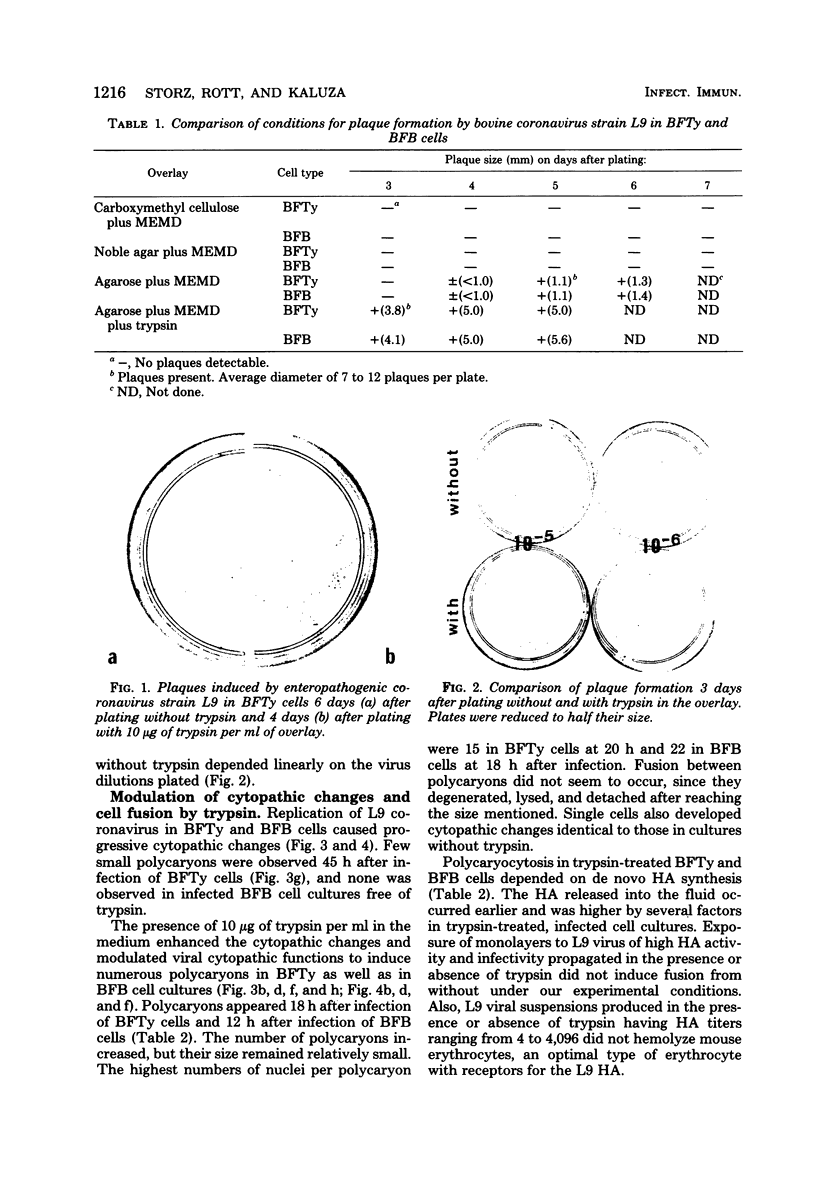

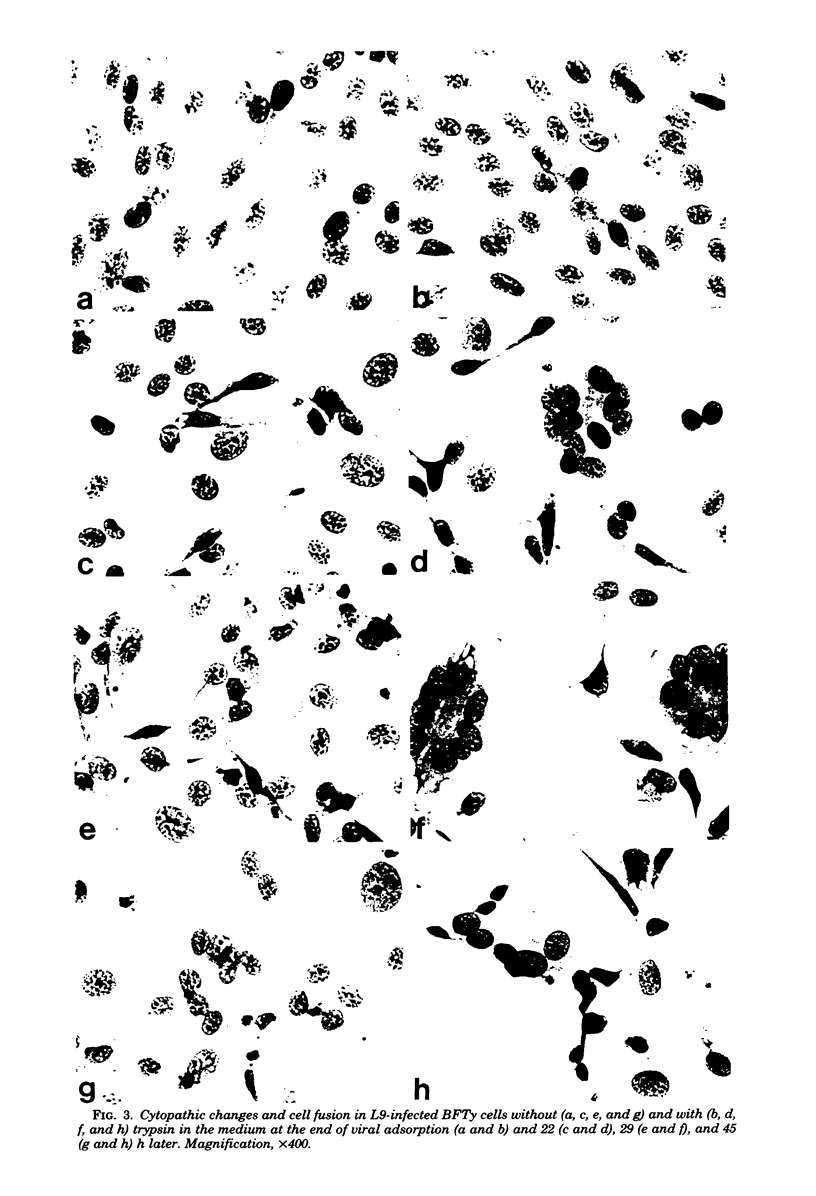

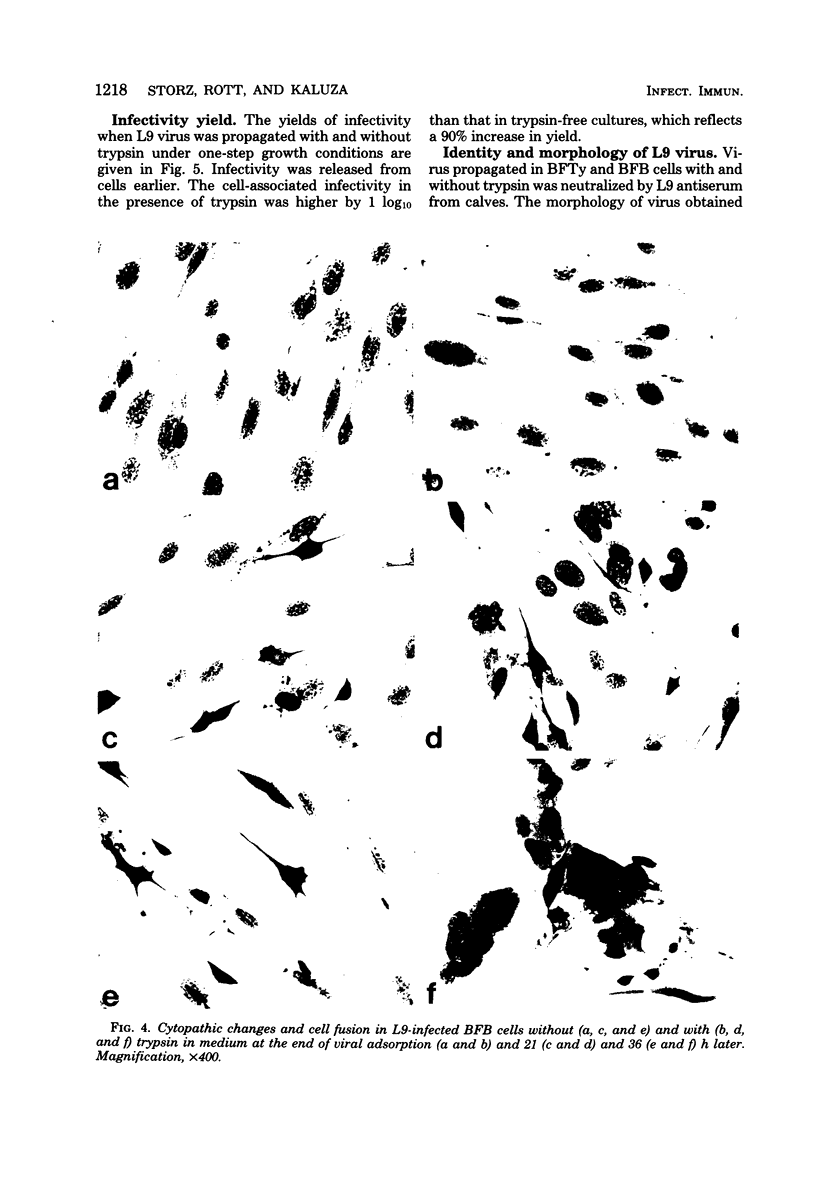

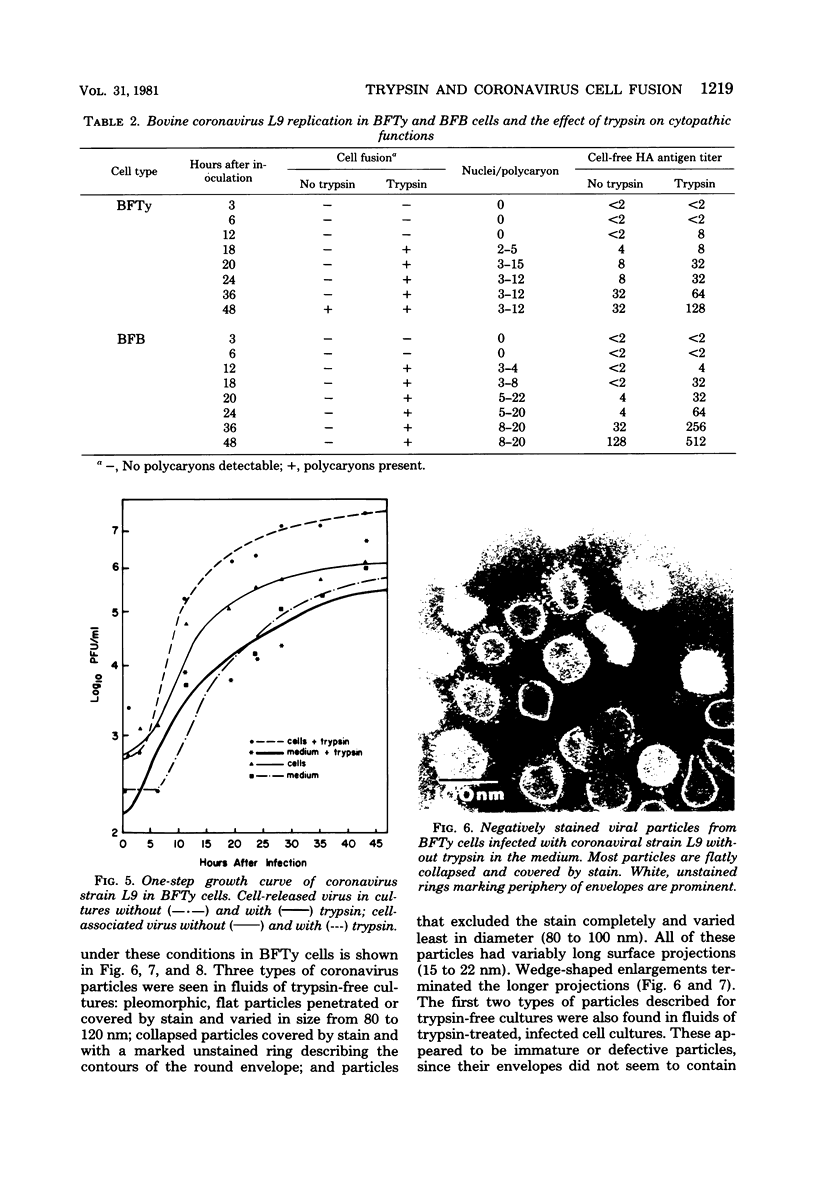

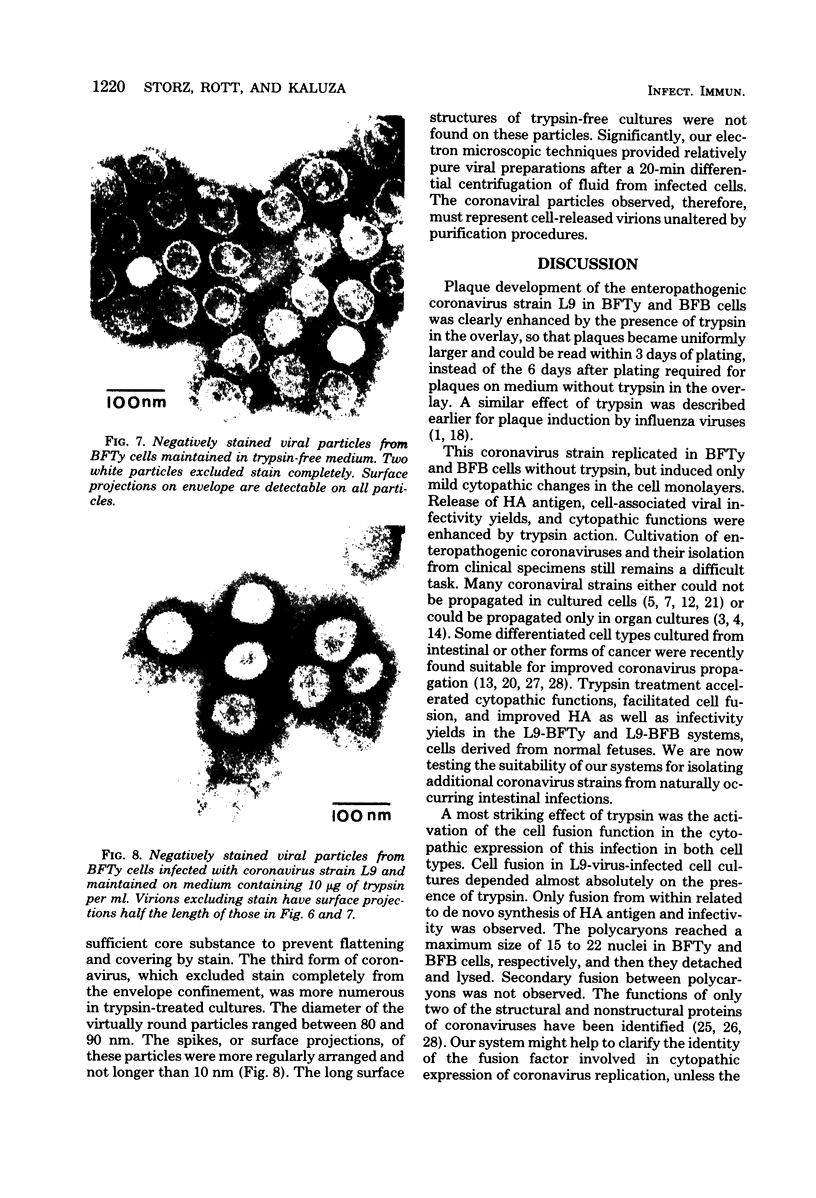

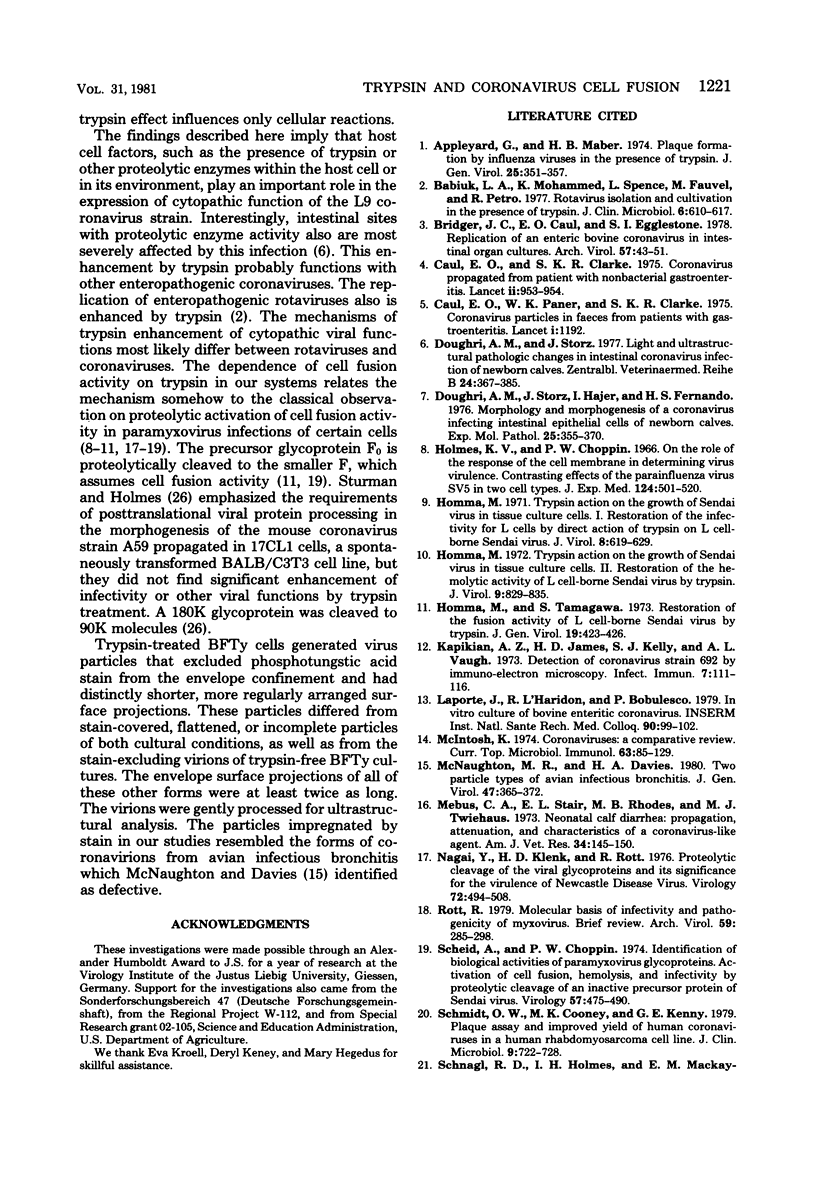

Plaque formation, replication, and related cytopathic functions of the enteropathogenic bovine coronavirus strain L9 in bovine fetal thyroid (BFTy) and bovine fetal brain (BFB) cells were investigated in the presence and absence of trypsin. Plaque formation was enhanced in both cell types. Plaques reached a size with an average diameter of 5 mm within 4 days with trypsin in the overlay, whereas their diameter remained less than 1 mm at this time after plating without trypsin in the overlay. Fusion of both cell types was observed 12 to 18 h after infection when trypsin was present in the medium. Fusion was not observed in infected BFB cell cultures and was rarely observed 48 h after infection of BFTy cells maintained with the trypsin-free medium. The largest polycaryons formed had 15 to 22 nuclei. They then lysed and detached. Cell fusion depended on de novo synthesis of hemagglutinin and infectivity. Fusion from without was not observed. Virus produced under trypsin-enhancing conditions accompanied by cell fusion did not lyse mouse erythrocytes that reacted with L9 coronavirus hemagglutinin. Trypsin-treated, infected BFTy cultures produced coronaviral particles that excluded stain from the envelope confinement. These virions had uniformly shorter surface projections than did the viral forms generated by trypsin-free cell cultures.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Appleyard G., Maber H. B. Plaque formation by influenza viruses in the presence of trypsin. J Gen Virol. 1974 Dec;25(3):351–357. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-25-3-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiuk L. A., Mohammed K., Spence L., Fauvel M., Petro R. Rotavirus isolation and cultivation in the presence of trypsin. J Clin Microbiol. 1977 Dec;6(6):610–617. doi: 10.1128/jcm.6.6.610-617.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridger J. C., Caul E. O., Egglestone S. I. Replication of an enteric bovine coronavirus in intestinal organ cultures. Arch Virol. 1978;57(1):43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF01315636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caul E. O., Clarke S. K. Coronavirus propagated from patient with non-bacterial gastroenteritis. Lancet. 1975 Nov 15;2(7942):953–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caul E. O., Paver W. K., Clarke S. K. Letter: Coronavirus particles in faeces from patients with gastroenteritis. Lancet. 1975 May 24;1(7917):1192–1192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)93176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughri A. M., Storz J., Hajer I., Fernando H. S. Morphology and morphogenesis of a coronavirus infecting intestinal epithelial cells of newborn calves. Exp Mol Pathol. 1976 Dec;25(3):355–370. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(76)90045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughri A. M., Storz J. Light and ultrastructural pathologic changes in intestinal coronavirus infection of newborn calves. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1977;24(5):367–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1977.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K. V., Choppin P. W. On the role of the response of the cell membrane in determining virus virulence. Contrasting effects of the parainfluenza virus SV5 in two cell types. J Exp Med. 1966 Sep 1;124(3):501–520. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma M., Tamagawa S. Restoration of the fusion activity of L cell-borne Sendai virus by trypsin. J Gen Virol. 1973 Jun;19(3):423–426. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-19-3-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma M. Trypsin action on the growth of Sendai virus in tissue culture cells. I. Restoration of the infectivity for L cells by direct action of tyrpsin on L cell-borne Sendai virus. J Virol. 1971 Nov;8(5):619–629. doi: 10.1128/jvi.8.5.619-629.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma M. Trypsin action on the growth of Sendai virus in tissue culture cells. II. Restoration of the hemolytic activity if L cell-borne Sendai virus by trypsin. J Virol. 1972 May;9(5):829–835. doi: 10.1128/jvi.9.5.829-835.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapikian A. Z., James H. D., Kelly S. J., Vaughn A. L. Detection of coronavirus strain 692 by immune electron microscopy. Infect Immun. 1973 Jan;7(1):111–116. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.1.111-116.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnaughton M. R., Davies H. A. Two particle types of avian infectious bronchitis virus. J Gen Virol. 1980 Apr;47(2):365–372. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-47-2-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebus C. A., Stair E. L., Rhodes M. B., Twiehaus M. J. Neonatal calf diarrhea: propagation, attenuation, and characteristics of a coronavirus-like agent. Am J Vet Res. 1973 Feb;34(2):145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Klenk H. D., Rott R. Proteolytic cleavage of the viral glycoproteins and its significance for the virulence of Newcastle disease virus. Virology. 1976 Jul 15;72(2):494–508. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rott R. Molecular basis of infectivity and pathogenicity of myxovirus. Brief review. Arch Virol. 1979;59(4):285–298. doi: 10.1007/BF01317469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A., Choppin P. W. Identification of biological activities of paramyxovirus glycoproteins. Activation of cell fusion, hemolysis, and infectivity of proteolytic cleavage of an inactive precursor protein of Sendai virus. Virology. 1974 Feb;57(2):475–490. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O. W., Cooney M. K., Kenny G. E. Plaque assay and improved yield of human coronaviruses in a human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line. J Clin Microbiol. 1979 Jun;9(6):722–728. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.6.722-728.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnagl R. D., Holmes I. H., Mackay-Scollay E. M. Coronavirus-like particles in Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 1978 Mar 25;1(6):307–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpee R. L., Mebus C. A., Bass E. P. Characterization of a calf diarrheal coronavirus. Am J Vet Res. 1976 Sep;37(9):1031–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz J., Okuna N., McChesney A. E., Pierson R. E. Virologic studies on cattle with naturally occurring and experimentally induced malignant catarrhal fever. Am J Vet Res. 1976 Aug;37(8):875–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz J., Rott R. Uber die Verbreitung der Coronavirusinfektion bei Rindern in ausgewählten Gebieten Deutschlands: Antikörpernachweis durch Mikroimmunodiffusion und Neutralisation. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1980;87(7):252–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman L. S., Holmes K. V. Characterization of coronavirus II. Glycoproteins of the viral envelope: tryptic peptide analysis. Virology. 1977 Apr;77(2):650–660. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90489-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman L. S. I. Structural proteins: effects of preparative conditions on the migration of protein in polyacrylamide gels. Virology. 1977 Apr;77(2):637–649. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90488-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman L. S., Takemoto K. K. Enhanced growth of a murine coronavirus in transformed mouse cells. Infect Immun. 1972 Oct;6(4):501–507. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.501-507.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wege H., Wege H., Nagashima K., ter Meulen V. Structural polypeptides of the murine coronavirus JHM. J Gen Virol. 1979 Jan;42(1):37–47. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-42-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]