Abstract

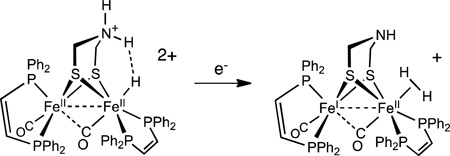

This report compares biomimetic HER catalysts with and without the amine cofactor (adtNH): Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 (1NH) and Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (2; (adtNH)2− = (HN(CH2S)22−, pdt2− = 1,3-(CH2)3S22−). These compounds are spectroscopically, structurally, and stereodynamically very similar but exhibit very different catalytic properties. Protonation of 1NH and 2 each give three isomeric hydrides beginning with the kinetically favored terminal hydride, which converts sequentially to sym and unsym isomers of the bridging hydrides. In the case of the amine, the corresponding ammonium-hydrides are also observed. In the case of the terminal amine hydride [t-H1NH]BF4, the ammonium/amine-hydride equilibrium is sensitive to counteranions and solvent. The species [t-H1NH2](BF4)2 represents the first example of a crystallographically characterized terminal hydride produced by protonation. The NH--HFe distance of 1.88(7) Å indicates dihydrogen bonding. The bridging hydrides [µ-H1NH]+ and [µ-H2]+ reduce near −1.8 V, about 150 mV more negative than the reductions of the terminal hydride [t-H1NH]+ and [t-H2]+ at −1.65 V. Reductions of the amine hydrides [t-H1NH]+ and [t-H1NH2]2+ are irreversible. For the pdt analog, the [t-H2]+/0 couple is unaffected by weak acids (pKaMeCN 15.3) but exhibits catalysis with HBF4•Et2O, albeit with a TOF around 4 s−1 and an overpotential greater than 1 V. The voltammetry of [t-H1NH]+ is strongly affected by relatively weak acids and proceeds at 5000 s−1 with an overpotential of 0.7 V. The ammonium-hydride [t-H1NH2]2+ is a faster catalyst with an estimated TOF of 58,000 s−1 and an overpotential of 0.5 V.

Introduction

In nature, hydrogen is primarily produced and oxidized by the hydrogenase (H2ase) enzymes.2 For example, under fermentative conditions, organisms release accumulated reducing equivalents as H2. This H2 can be captured by other organisms, where it is utilized, via hydrogenases, to reduce oxides such as sulfate.3 These enzymes have attracted attention as proven motifs for the processing of hydrogen.4,5 A key goal in this area is the elucidation of catalytic mechanisms.

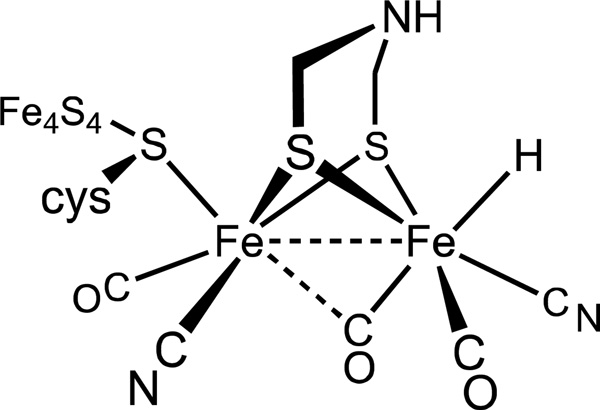

The first step in characterizing catalytic mechanism is understanding the structure of the active sites. Two genetically unrelated H2ases have been identified, they contain Ni and/or Fe thiolate centers, the latter bound to CN− and CO, and are generally rich in Fe-S clusters, emphasizing the central role of electron-transfer.1,6 [FeFe]-H2ases are more active than [NiFe]-H2ases, and they more commonly function as catalysts for H2 production (Table 1).7 In the case of [FeFe]-H2ases, one 4Fe-4S cluster is directly tethered to the diiron active site, the 6Fe ensemble being called the H-cluster. The [FeFe]-H2ases also feature an amino-dithiolate cofactor that bridges the two organoiron centers (Figure 1).8

Table 1.

Activities of [FeFe]- and [NiFe]-Hydrogenases.1

| Reaction | FeFe | NiFe |

|---|---|---|

| H2 Oxidation | 28000 | 700 |

| H2 Production | 6000–9000 | 700 |

Rates quoted in moles of H2 per mole of enzyme per second measured at 30 °C.

Figure 1.

Structure proposed for the active site of [FeFe]-hydrogenase in the Hred state.1

One widely embraced method to mechanistic analysis of the enzymes entails studies on synthetic diiron dithiolato compounds that are structurally similar to the active site.4,9 This approach benefits from many decades of research on organoFe-S clusters.10 Indeed, soon after the structure of the enzymes from C. pasteurianum and D. desulfuricans were reported, the diiron dithiolato dicyanides [Fe2(pdt)(CN)2(CO)4]2− (pdt = 1,3-propandithiolate) were described.11 These species proved to be not very useful in developing functional models however. Since that time, two simplifications have been particularly enabling. First, tertiary phosphine (and other) ligands are used in place of cyanide (and some CO) ligands found in the natural catalysts.12 Second, in place of the appended 4Fe-4S cluster, models usually rely on electrodes to supply and accept electrons. No compromise is required for the amine-dithiolate cofactor (adt), which is incorporated into our models without modification.13

Consensus from the biophysical3 and organometallic4,12 studies points to the intermediacy of iron hydrides in catalytic function of [FeFe]-H2ase. Although much is known about iron hydrides,14 our understanding of diiron dithiolato hydride frameworks is still underdeveloped. CO-rich compounds such as Fe2(SR)2(CO)6 are only protonated by very strong acids,15 hence the requirement that some CO ligands be replaced by more basic donors. In almost all hydride derivatives of diiron dithiolates, the hydride ligand bridges the two metals. This geometry resembles that found in the [NiFe]-H2ases, but biophysical3 and computational studies16 on the [FeFe]-H2ases strongly indicate that the hydride is located at the apical position of a single organoFe center. A number of diiron complexes with terminal hydride ligands have been characterized, although usually only by NMR spectroscopy. The terminal hydride complexes [HFe2(pdt)(CO)4(chel)]+ are often observable by NMR spectroscopy, but above ca. −30 °C they isomerize to bridging hydride complexes (chel = chelating ligands).17,18 The stability of these terminal hydride complexes is enhanced for sterically crowded or very electron-rich diiron dithiolato carbonyls.19,20 Thus, Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (2, pdt = 1,3-propanedithiolate) undergoes protonation, albeit only with strong acids, to give a terminal hydride with a half-life of several minutes at room temperature (dppv = cis-C2H2(PPh2)2). Additionally, this terminal hydride derivative was shown to reduce at a potential ca. 100 mV less negative than the isomeric bridging hydride complex.19

Herein we summarize an extensive investigation of the structural and protonation chemistry of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 (1NH) (adtNH = [(SCH2)2NH]2−), with parallel studies on the Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (2), which lacks the amine cofactor. Overall, the results indicate that the combination of a terminal hydride and the azadithiolate cofactor greatly facilitates reduction of protons to form H2 by diiron complexes. We also describe a rare crystal structure of a terminal hydride of this series of model diiron dithiolato complexes.

Results

Characterization of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2

The main catalyst of interest is Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 (1NH), a greenish-brown, air-sensitive solid that is highly soluble in dichloromethane and toluene. The IR spectra for 1NH (νCO = 1888, 1868 cm−1) and related derivatives Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (2), Fe2(edt)(CO)2(dppv)2, and Fe2(odt)(CO)2(dppv)2 are similar, which indicates that they adopt similar structures and that the donor properties of the dithiolates are similar (edt2− = 1,2-C2H4S22−; odt2− = O(C2H4S)22−).21 Compounds 1NH and 2 are stereochemically nonrigid in two ways: (i) “turnstile rotation” of the Fe(dppv)(CO) subunits and (ii) “flipping” of the dithiolate bridge. With respect to the latter process, the X(CH2S)2Fe rings (X = CH2, NH, O, etc) are subject to a chair-chair equilibration,22 as seen in cyclohexane and piperidine derivatives.23

At −80 °C, the 31P NMR spectrum of 1NH displays four equally intense signals indicating that the two dppv ligands are chemically inequivalent. In contrast, spectra for the related pdt complexes show only a pair of signals at low temperatures, an observation that suggests that pdt is a more flexible dithiolate than adt. Turnstile rotation at the Fe(dppv)(CO) unit is halted on the NMR timescale at −80 °C, but flipping of the dithiolate remains fast. In the adt derivative, both processes are either slow or cease to occur at low temperatures, which may reflect a higher barrier for the flipping of the adt compared to the structurally related pdt derivative.* At −10 °C, this conformational equilibrium becomes rapid on the NMR timescale, and the 31P NMR spectrum simplifies to a broad singlet. The dynamics of the adt and the turnstile rotation of the Fe(CO)(dppv) centers appear to be coupled since both processes change from slow to fast exchange regimes at the same temperature range (see Supplementary Information).

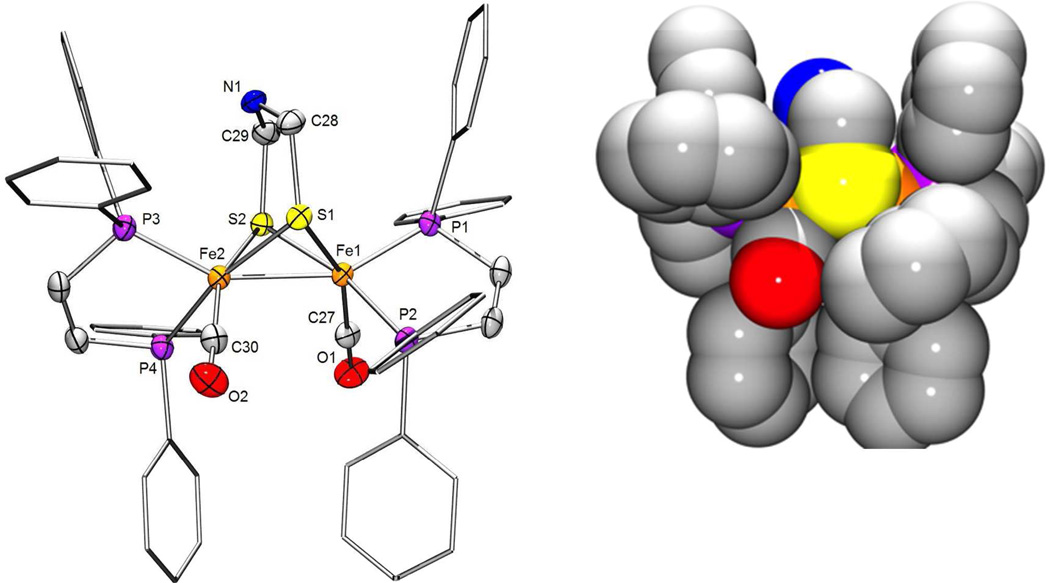

The structure of 1NH was confirmed crystallographically (Figure 2), the details being consistent with the NMR results. Space-filling models show that the phenyl groups protect the Fe-Fe bond, which is relevant to the regiochemistry of the protonation of 1NH and 2.

Figure 2.

Structure of Fe2(adrNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 (1NH). Left: with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 50 % Selected distances (Å): Fe1-Fe2, 2.6027(6); Fe1-C27, 1.7381(30); Fe1-P1, 2.1884(8); Fe1-P2, 2.2108(8); Fe1-S1, 2.2108(8); Fe1-S2, 2.2668(8); Fe2-C30, 1.7508(30); Fe2-P3, 2.1937(9); Fe2-P4, 2.2296(8); Fe2-S1, 2.2785(8); Fe2-S2, 2.2668(8). Right: space-filling model showing that the Ph groups block the Fe-Fe bond (red = O, blue = N, yellow = S, orange = Fe, violet = P).

Isomers of [HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+

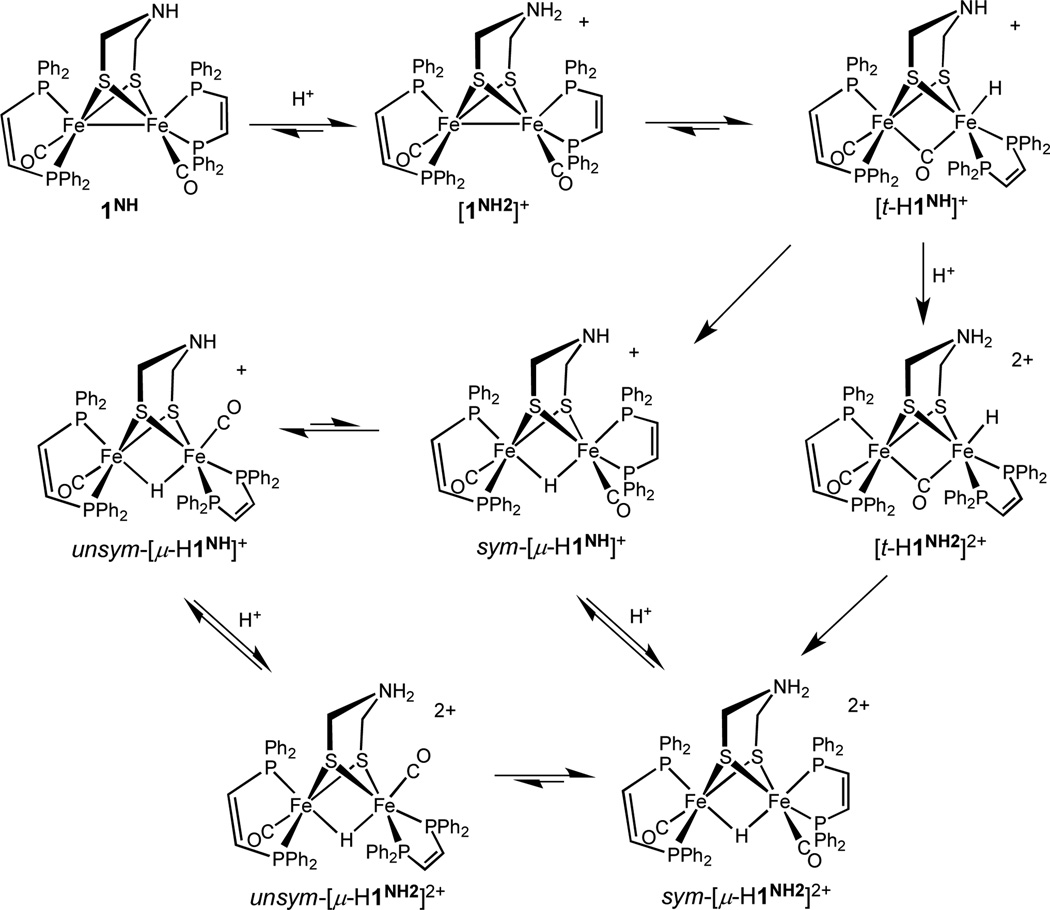

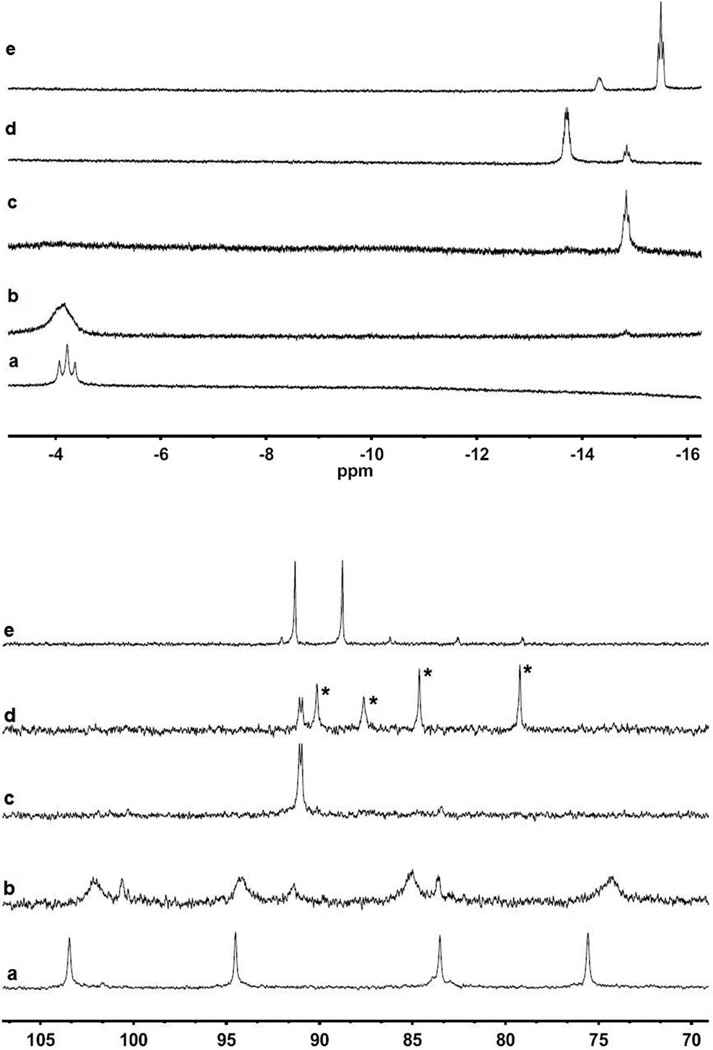

Protonation of 1NH gives three isomeric hydrides as well as ammonium derivatives or combinations of both. Addition of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 to a CH2Cl2 solution of 1NH at −80 °C initially afforded the terminal hydride [t-HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+ ([t-H1NH]+) (BArF4− = B(3,5-C6H3(CF3)2)4−, Scheme 1). Its high field 1H NMR spectrum, a triplet near δ −4.2, indicates a single isomer (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3). Such relatively low field chemical shifts are often associated with terminal hydrides of diiron dithiolates.17–20 The 31P NMR spectrum, which features four equally intense singlets (Table 2), uniquely defines the structure: the diphosphine on the FeH center is dibasal and the diphosphine on the other (“proximal”) Fe center spans apical and basal sites (31P-31P coupling is often weak in such complexes).24

Scheme 1.

Protonation of 1NH and isomerization reactions of the resulting hydrides.

Table 2.

Spectroscopic Properties for 1NH, 2, and Their Protonated Derivatives in CD2Cl2 solution.

| Compound | IR: νCO (cm−1) |

1H NMR: δ Hydride (ppm) |

31P NMR (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2, 1NH | 1888, 1868 | - | 91.2 −70 °C: 102.6, 93.4, 92.2, 88.6 |

| [t-HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H1NH]+ |

1965, 1915 | −4.2 (t) J = 73 Hz |

103.2, 94.5, 84.0, 75.1 |

| [t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, [t-H1NH2]2+ |

1986, 1925 | −4.95 (t) J = 72 Hz |

98, 89, 76, 74 |

| [Fe2(adtNH)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, sym-[µ-H1NH]+ |

not obsv'd | −14.8 (tt) J = 25, 5 Hz |

91.1, 90.9 |

| [Fe2(adtNH)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, unsym-[µ-H1NH]+ |

1948, 1969 | −13.7 (dtd) | 90.1, 87.6, 84.6, 79.2 |

| [Fe2(adtNH2)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, sym-[µ-H1NH2]2+ |

1967, 1985 | −15.6 (tt) J = 20, 5 Hz |

91.3, 88.7 |

| [Fe2(adtNH2)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, unsym-[µ-H1NH2]2+ |

not obsv'd | −14.5 (dtd) | 92.3, 86.0, 82.4, 79.0 |

| Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2, 2 | 1888, 1868 | - | 90.8 −80 °C: 97, 88.5 |

| [HFe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H2]+ |

1965, 1905 | −3.5 (t) J = 78 Hz |

99, 91, 86, 68 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, sym-[µ-H2]+ |

not obsv'd | −15.6 (tt) J = 24, 6 |

89.6, 89.4 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, unsym-[µ-H2]+ |

1951, 1968 | −14.5 (dddd) J = 24, 19,19, 10 |

76.7, 82.7, 84.2, 87.9 |

Figure 3.

1H and 31P NMR spectra of the protonation of 1NH with [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 in CD2Cl2 at various times and temperatures. Spectra a: −80 °C ([t-H1NH]+). Spectra b: sample warmed to −10 °C. Spectra c: sample warmed to 20 °C (sym-[µ-H1NH]+, this spectrum does not change upon recooling to 0 °C). Spectra d: previous sample after standing at 20 °C for 24 h, (sym- and unsym-[µ-H1NH]+, the latter indicated by asterisks). Spectra e: same sample after addition of 1 equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (mainly sym-[µ-H1NH2]2+ and a small amount of the unsym isomer).

The NMR spectrum of [t-H1NH]+ changes at higher temperatures indicative of interconversion between the Fe-H and ammonium tautomers. Above −20 °C, the triplet at δ −4.2 in the 1H NMR spectrum broadens, as do the 31P NMR signals, consistent with exchange between the hydride and ammonium tautomers (Scheme 2). Near room temperature, [t-H1NH]+ converts sequentially to two isomers that feature bridging hydride ligands (“µ-hydrides”, Scheme 1). The first µ-hydride isomer, sym-[µ-H1NH]+, has C2-symmetry (ignoring the adt ligand, which is rapidly flexing and hence effectively planar). In sym-[µ-H1NH]+, each dppv ligand spans one apical and one basal site. Upon re-cooling a solution of sym-[µ-H1NH]+ to 0 °C, the terminal hydride species does not reform. Within minutes at room temperature, sym-[µ-H1NH]+ converts to an unsymmetrical isomer labeled unsym-[µ-H1NH]+. In unsym-[µ-H1NH]+, one diphosphine remains apical-basal and the other is dibasal as indicated by 31P NMR spectrum, which consists of four singlets. After allowing the solution to stand for 12 h at room temperature, a 1:5 equilibrium distribution is reached, favoring unsym-[µ-H1NH]+. The isomerization of ([t-H1NH]+ is similar to that observed for the hydrides of 2.18

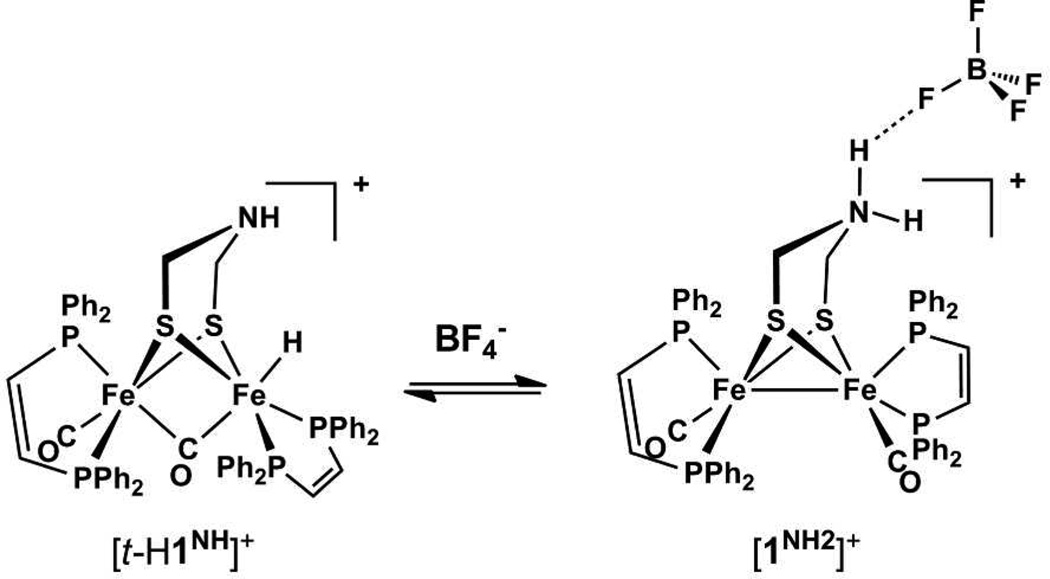

Scheme 2.

Proposed hydrogen-bonding interaction between [1NH2]+ and BF4− resulting in stabilization of the ammonium tautomer.

Addition of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 to a CH2Cl2 solution of [µ-H1NH]+ shifts the νCO pattern about 15 cm−1 to higher energy. This change is indicative of N-protonation to form the ammonium-hydride [µ-H1NH2]2+ (Scheme 1).25 N-protonation is also indicated by the 1H NMR signal for the hydride, which shifts to higher field. The symmetrical isomer, sym-[µ-H1NH2]2+, is the major species in solution, in contrast to the situation for [µ-H2]+ and [µ-H1NH]+.

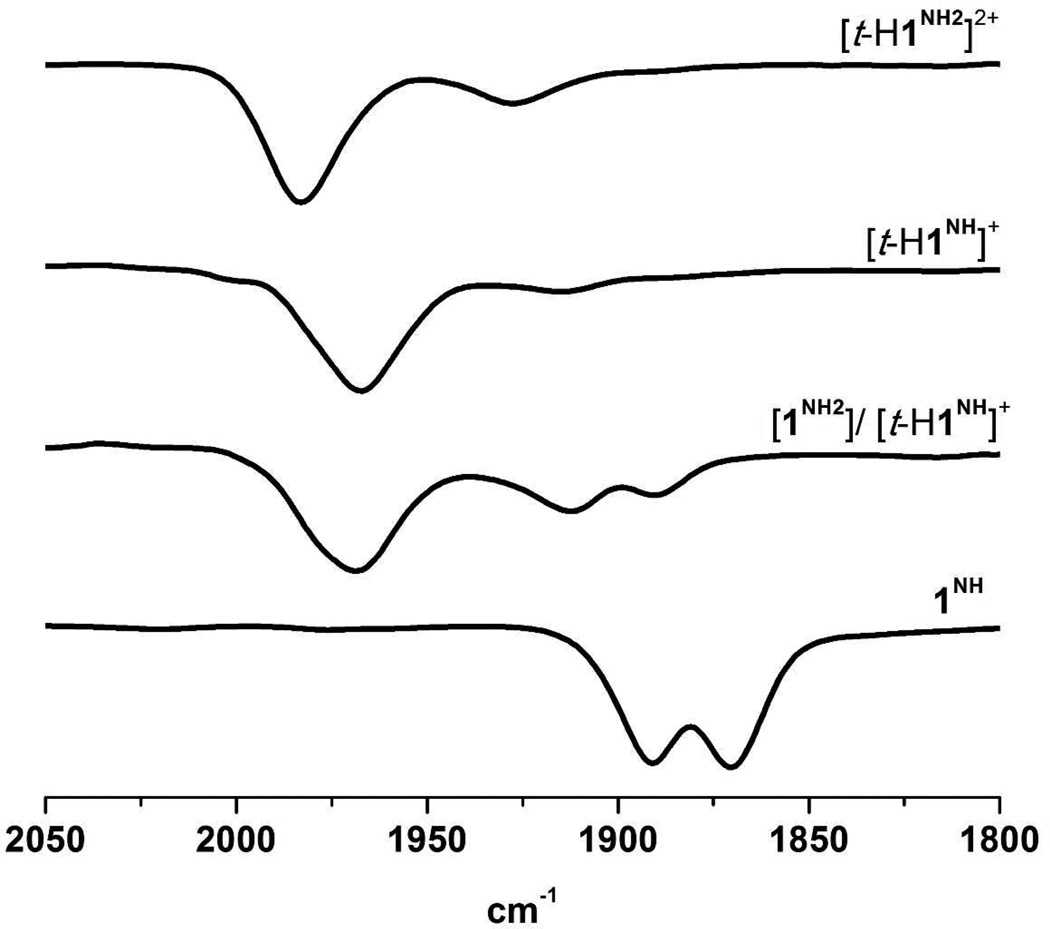

IR spectroscopic measurements on the protonation reactions are consistent with the sequence of reactions proposed in Scheme 1. The main feature of interest is the ca. 70 cm−1 shift in νCOavg upon protonation of 1NH by [H(OEt2)2]BArF4, regardless of the t- vs µ-hydride isomer. IR spectra in the νCO region also distinguish terminal and bridging hydrides. The terminal hydrides shows two well-resolved bands, νCO = 1965 and 1915 cm−1, with the band at lower frequency assigned to the semi-bridging CO. The IR spectra of µ-hydrides show two bands, νCO ~ 1948 and 1969 cm−1.

Protonation of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 with HBF4•Et2O

The identity of the acid affects the course of protonation of 1NH. Thus, treatment of CH2Cl2 solutions with HBF4•Et2O (vs [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 discussed above) afforded not only [t-H1NH]+ but also a second species. The pattern for the νCO bands for the other species is identical to that for 1NH, but the bands are shifted approximately 20 cm−1 to higher energy, characteristic of N-protonation.25,26 The new species is thus assigned as the ammonium tautomer ([1NH2]+, Schemes 1,2). The formation of the tautomer is attributed to the ability of BF4− to participate in hydrogen-bonding (Scheme 2),27 which has been observed previously in complexes of protonated adt ligands.28 The ratio [t-H1NH]+/[1NH2]+ increased from 2:1 to approximately 1:1, in the presence of 10 equiv of [Bu4N]BF4. Over the course of several minutes at room temperature, the [t-H1NH]BF4/[1NH2]BF4 mixture isomerized to the µ-hydrides. Thus, although BF4− stabilizes the ammonium tautomer, the mixture isomerizes in the usual way, forming the µ-hydride species.

The [1NH2]BF4/[t-H1NH]BF4 ratio is also affected by the solvent.

Diprotonation of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2

Relevant to the electrocatalysis discussed below, 1NH undergoes double protonation. Addition of excess of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4, HBF4•Et2O, or CF3CO2H to a CH2Cl2 solution of [t-H1NH]+ gave a new species assigned as the ammonium-hydride [t-H1NH2]2+ (Figures 3 and 4). According to 1H and 31P NMR spectra, [t-H1NH2]2+ is structurally similar to [t-H1NH]+, i.e. a single isomer with both dibasal (distal to the hydride) and apical-basal (proximal) diphosphine ligands (Table 2). As seen for 1NH vs [1NH2]+, N-protonation shifts νCO bands to higher energy by 20 cm−1, compared to that for [t-H1NH]+.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra in the νCO region of 1NH (bottom) and products from its protonation in CH2Cl2. A mixture of the ammonium cation [1NH2]+ and [t-H1NH]+ generated by addition of excess [Bu4N]BF4 to a solution of [t-H1NH]+. The terminal hydride, [t-H1NH]+, formed by protonation of 1 with one equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 at −40 °C. The terminal hydride ammonium dication [t-H1NH2]2+ formed by protonation of 1NH with 2 equiv of HBF4•Et2O at −40 °C.

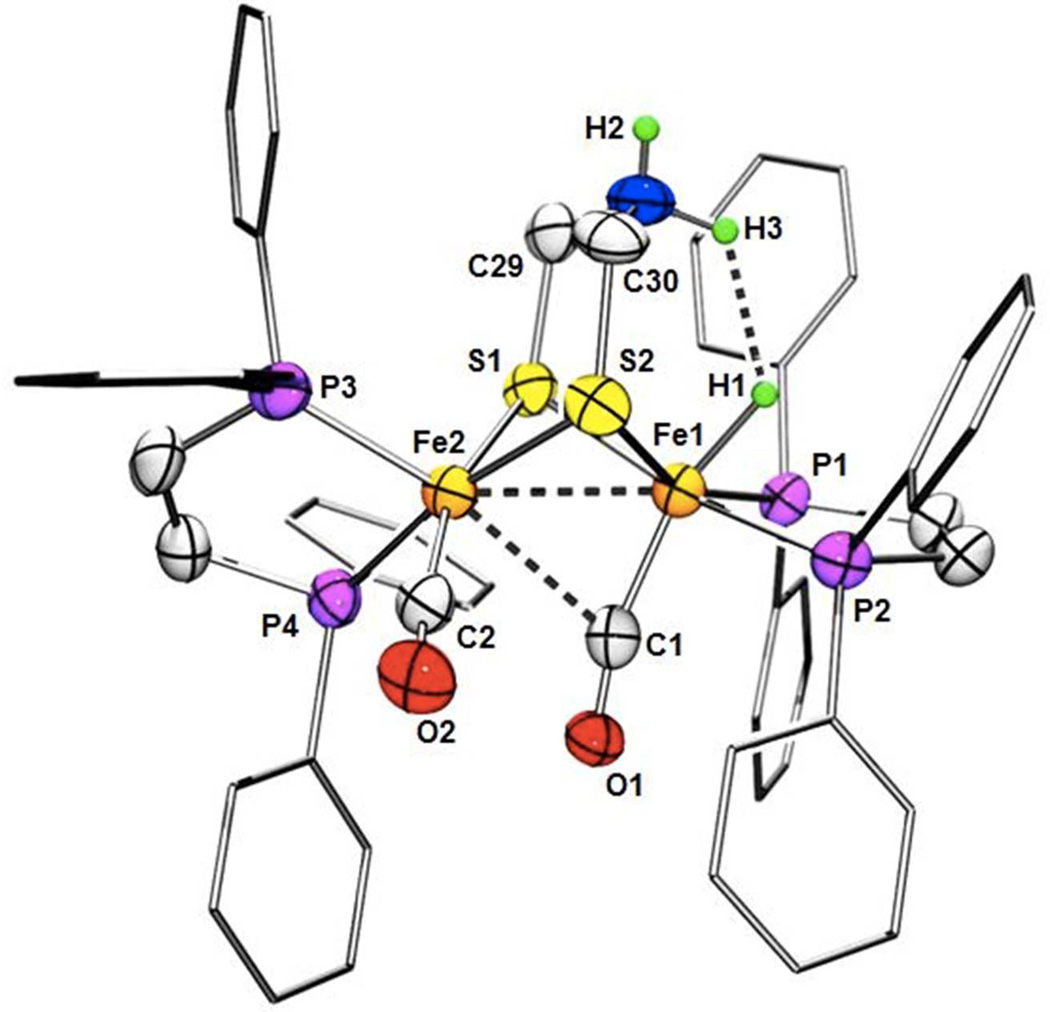

After attempts over the course of several years, single crystals of an ammonium hydride were obtained in the form of the salt [t-H1NH2](BF4)2 (Figure 5). In the dication, two Fe(dppv)(CO) centers are linked in the usual way by a dithiolate. One CO ligand is semi-bridging with an Fe-Fe-C and Fe-C-O angles of 66.68(14) and 166.1(4)°, respectively.29 The dispositions of the dppv groups, being dibasal and apical-basal, conform with the NMR measurements. The crystals are of sufficient quality that the H centers attached to nitrogen and iron were located and refined. Two phenyl groups on the Fe(1)(dppv) center, equivalent to the distal Fe in the active site, form a pocket around the Fe-H and N-H centers. The Fe-H distance of 1.44(4) Å is normal for a ferrous hydride.30 The ammonium center of the dithiolate cofactor adtH+ is adjacent to the Fe-H center. The NH---HFe distance of 1.88(7) Å is shorter than 2.4 Å distance that is twice the van der Waals radius of hydrogen,31 indicative of dihydrogen bonding.

Figure 5.

Structure of [t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(dppv)2](BF4)2, [t-H1NH2](BF4)2. Counter ions and solvent of crystallization are not shown. Selected distances (Å): H1---H2, 1.88(7); Fe1-C1, 1.794(5); Fe1-P2, 2.2141(13); Fe1-P1, 2.2196(12); Fe1-S2, 2.2610(12); Fe1-S1, 2.3009(13); Fe1-Fe2, 2.6155(9); Fe1-H1, 1.44(4); Fe2-C2, 1.769(5); Fe2-P3, 2.2122(14); Fe2-S2, 2.2348(14); Fe2-S1, 2.2564(12); Fe2-P4, 2.2686(14). Angles (°): C1-Fe1-Fe2, 66.68(14); Fe2-Fe1-H1, 130.3(18); S2-Fe1-S1, 83.50(4); S2-Fe2-S1, 85.12(4); O1-C1-Fe1, 166.1(4).

Protonation of Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (xdt = adtNH, pdt) with Weak Acids

Weak acids that do not convert 1NH into detectable levels of [t-H1NH]+ at low temperatures quantitatively give [µ-H1NH]+ near room temperature. Qualitatively, the rate of formation of [µ-H1NH]+ correlates with the strength of the acid. Thus, [HNMe3]BArF4 (pKaMeCN = 17.6)32 rapidly converted 1 to [µ-H1NH]+, whereas the same conversion using [HNEt3]BF4 (pKaMeCN = 18.6)32 required days for full conversion.

Addition of CF3CO2H (pKaMeCN = 12.7)32 to 1NH at −40 °C gave [t-H1NH2]2+. The IR spectrum (νCO = 1986 and 1950 cm−1) of the trifluoroacetate differs from that (νCO = 1986 and 1925 cm−1) obtained by protonation with [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 and HBF4•Et2O, a difference attributed to hydrogen bonding between the trifluoroacetate and the protonated adt ligand. In contrast to the acid-base behavior of 1NH, the pdt derivative, 2, is unaffected by weak acids.

Redox Properties of the Protonated Derivatives of Fe2(xdt)(CO)2(dppv)2 (xdt = adtNH, pdt)

In CH2Cl2 solutions, the µ-hydrides [µ-H1NH]+ and [µ-H2]+ reversibly reduce near −1.8 V. Reduction of the doubly protonated species [µ-H1NH2]2+ occurs about ~ 100 mV positive of the [µ-H1NH]+/0 couple, as observed for other adt-hydrido complexes.33 The terminal hydrides [t-H1NH]+ and [t-H2]+ are redox-active at milder potentials, the pdt derivative [t-H2]+ reducing quasi-reversibly (ip/ic = 1.57) at –1.67 V. Reduction of [t-H2]+ is a 1e− process as indicated by the similarity of the dependence of ip vs ν1/2 for the couples [t-H2]+/0 and [2]0/+.19 We have independently established the stoichiometry of the [2]0/+ couple.34 The amino-hydride [t-H1NH]+ reduces at nearly the same potential (−1.64 V), but the couple is irreversible in contrast to the [t-2H]+/0 couple. The ammonium hydride [t-H1NH2]2+ also reduces irreversibly but at the mild potential of −1.3 V (Table 3). Although the reduction potential is milder, stronger acids are required to generate this doubly protonated species. Finally, both the [t-H1NH]+/0 and the [t-H2]+/0 proved insensitive to the electrolyte, i.e. [Bu4N]BArF4 and [Bu4N]PF6.

Table 3.

Selected Electrochemical Properties of 1 and 2, and Their Protonated Derivatives. The Electrolytes for Measurements: [Bu4N]BArF4 (for 1) and [Bu4N]PF6 (for 2).

| Compound |

E1/2 in CH2Cl2 (V vs Fc+/0) |

assignment | ipc/ipa |

|---|---|---|---|

| [t-HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H1NH]+ |

−1.64 | [t-H1NH]+/0 | irreversible |

| [t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, [t-H1NH2]2+ |

−1.4 | [t-H1NH2]2+/+ | irreversible |

| [Fe2(adtNH)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [µ-H1NH]+ |

−1.86 | [µ-H1NH]+/0 | 1.19 |

| [Fe2(adtNH2)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, [µ-H1NH2]2+ |

−1.77 | [µ-H1NH2]2+/+ | 1.00 |

| [HFe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H2]+ |

−1.67 | [t-H2]+/0 | 2.56 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(µH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+,[µ-H2]+ | −1.8 | [µ-H2]+/0 | 1.07 |

Proton Reduction Catalysis by Fe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2

For comparison with the catalyst that contains the amine cofactor, the catalytic properties of [t-H2]+ and [µ-H2]+ were evaluated. Strong acids such HBF4•Et2O (pKaMeCN = −3)35 are required to protonate 2, readily giving the terminal hydride [t-H2]+, which is stable for many minutes at 0 °C. The [t-H2]+/0 couple at −1.67 V is partially reversible even at scan rates as slow as 25 mV/s. Addition of ClCH2CO2H (pKaMeCN = 15.3)35 has no effect on the electrochemical properties of [t-H2]+. Addition of HBF4•Et2O results in an increase in current for the couple at −1.67 V, indicative of catalysis. The ratio ic/ip increases linearly with [H+] up to 8 equiv of acid, indicating a catalytic pathway that is second order with respect to [H+]. Above this level, ic/ip reached a plateau near 5. The turnover frequency is calculated to be ~5 s−1 (See Supporting Information). The overpotential is estimated to be 1.3 V. Overpotentials represent the difference between the catalytic potential, Ecat, and the standard reduction potential of the acid, E°HA/H2 (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Selected Electrocatalytic Properties of Protonated Derivatives of 1 and 2.

| Catalyst | Acid | Linear Region [H+](mM) |

Plateau Region [H+] (mM) |

(ic/ip)maxa | k (s−1) |

Ecatb (V vs Fc+/0) |

Overpotentialc (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H1NH]+ |

ClCH2CO2H | 50–400 | 600–1200 | 69 | 5000 | −1.49 | 0.71 |

| HFe2(adtNHH)(CO)2(dppv)2]2+, [t-H1NH2]2+ |

CF3CO2H | 20–280 | 370–750 | 167 | 58000 | −1.11 | 0.51 |

| [Fe2(adtNH)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2+, [µ-H1NH]+ |

ClCH2CO2H | 2–50 | 60–90 | 10 | 20 | −1.72 | 0.90 |

| [HFe2(pdt)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [t-H2]+ |

HBF4•Et2O | 1–8 | 10–20 | 5 | 5 | −1.49 | 1.32 |

| [Fe2(pdt)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]+, [µ-H2]+ |

ClCH2CO2H | 2–10 | 14–40 | 3.5 | 3 | −1.78 | 0.95 |

icis the average catalytic current in the plateau region

Ecat was calculated at each acid concentration in the linear region by the method described by Fourmond, et al., considering the effects of homoconjugation for the two carboxylic acids.37 The Ecatvalues listed are averages from each acid concentration in the linear region.

Overpotential = Eo HA/H2 - Ecat, where EoHA/H2 is the standard reduction potential of the acid.37

The catalytic properties of [µ-2H]+ were also examined. Addition of ClCH2CO2H to a solution of [µ-2H]BF4 results in an increase in the current for the −1.8 V couple (See SI). Plots of ic/ip vs [H+] are linear up to 10 equiv of acid, and the rate of catalysis by this derivative is calculated to be ~3 s−1. The overpotential is estimated to be 0.95 V for this very slow process.35

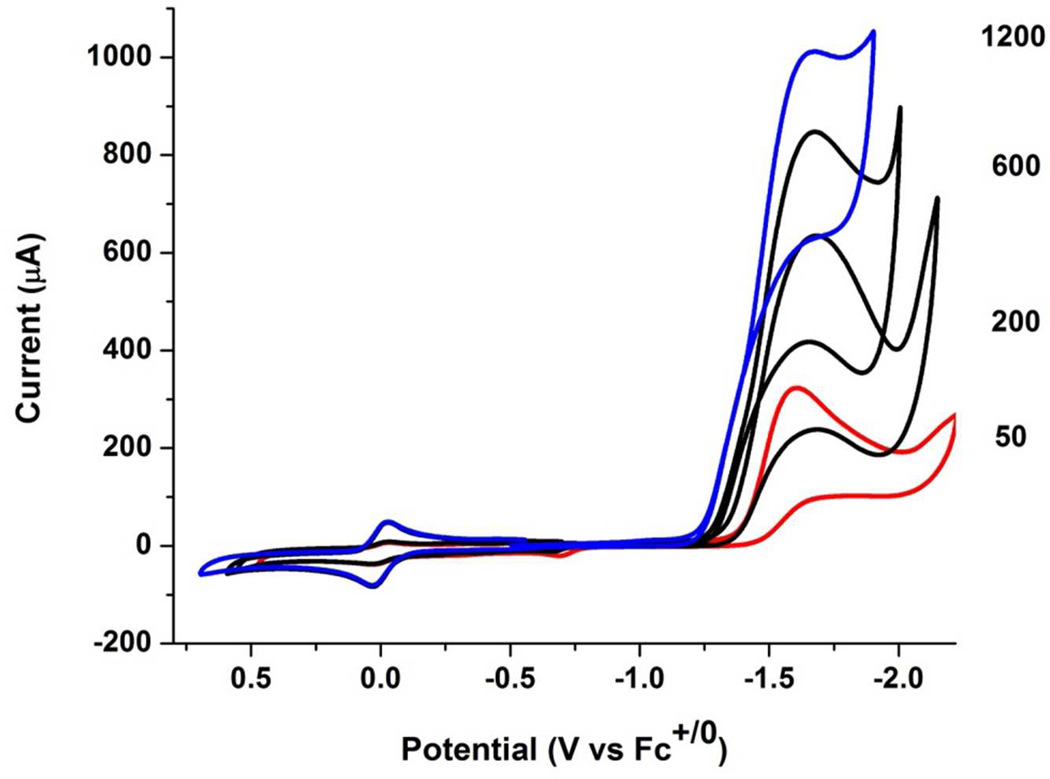

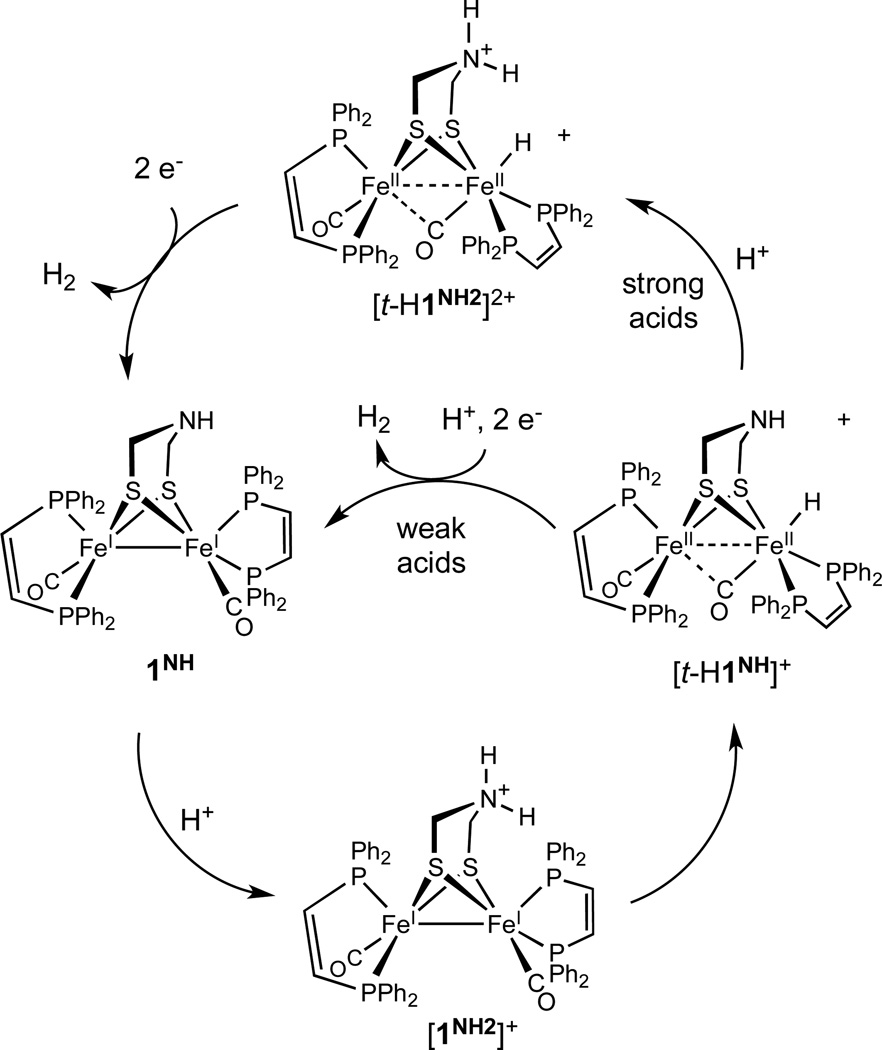

Proton Reduction Catalysis by Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2

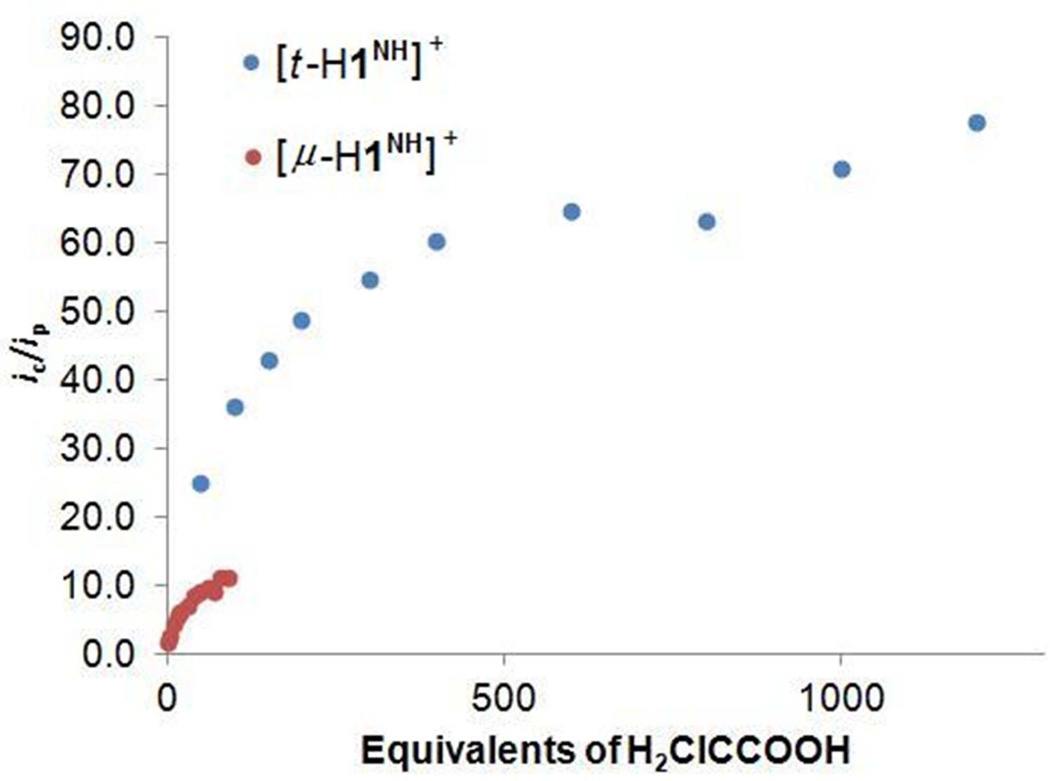

In contrast to the behavior of the pdt complex, the voltammetry of [t-H1NH]+ is strongly affected by relatively weak acids. Experiments employed [Bu4N]BArF4 as the electrolyte to maximize the equilibrium concentration of [t-H1NH]+ vs its tautomer [1NH2]+. When [t-H1NH]+ was generated in-situ from 1NH and one equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4, the current for the [t-H1NH]+/0 couple closely matched the current for the [1NH]0/+ couple, indicating that both events correspond to one-electron couples. Whereas the couple [2H]+/0 is partially reversible, the [t-H1NH]+/0 couple is completely irreversible (Supporting Information). Upon addition of ClCH2CO2H to solutions of 1, the reductive current at −1.64 V sharply increased and ipc shifts to more positive potential (Ecat = −1.43 V), indicative of catalytic proton reduction (Figure 6).35 A plot of ic/ip vs [H+] is linear over the range 50 to 400 equiv. The maximum ic/ip of ~70 corresponds to a rate of 5000 s−1 (Figure 7). Gas chromatographic analysis showed that a 90% yield of hydrogen was produced by bulk electrolysis.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 1.00 mM solution of 1NH (0 °C, 0.125 M [Bu4N]BArF4, CH2Cl2, scan rate = 0.5 V/s, glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag wire pseudo reference electrode, Fc internal standard) recorded with increasing equiv of ClCH2CO2H.

Figure 7.

Graph of ic/ip vs equiv acid for the addition of ClCH2CO2H to a 1.00 mM solution of 1NH, with [Bu4N]BArF4 as supporting electrolyte (blue) and 1.0 M solution of [µ-H1NH]+, with [Bu4N]PF6 as supporting electrolyte (red). Inset: magnified data for [µ-H1NH]+.

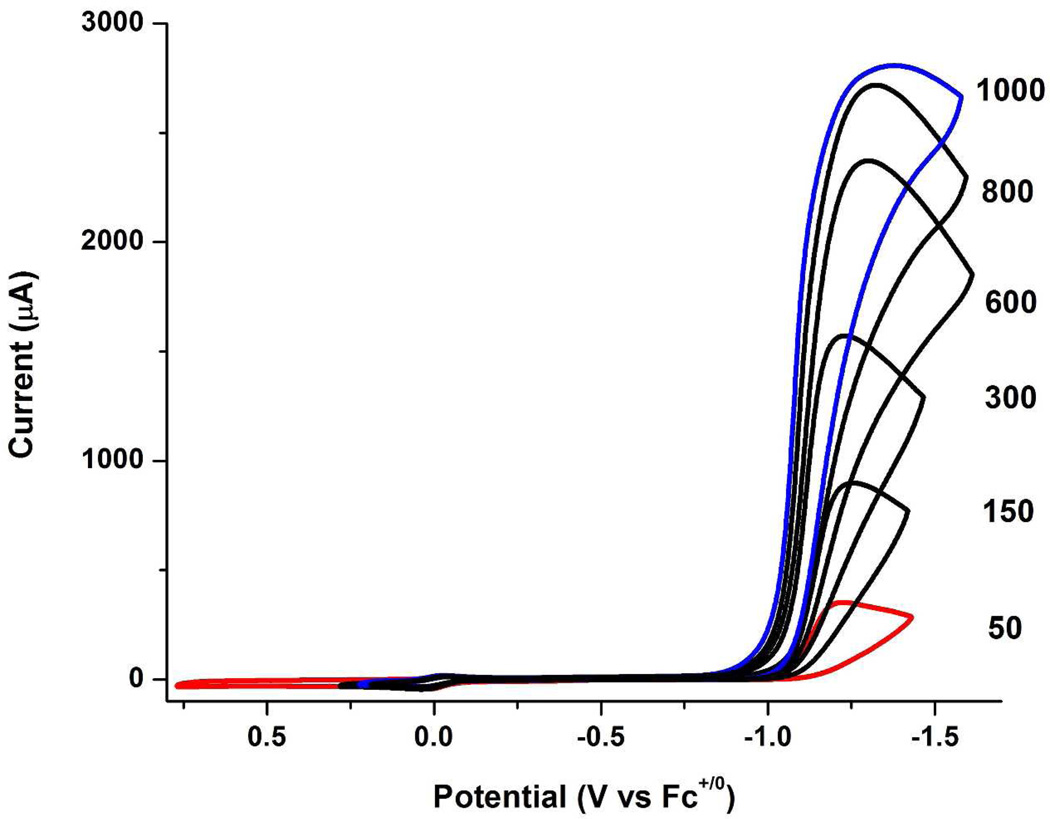

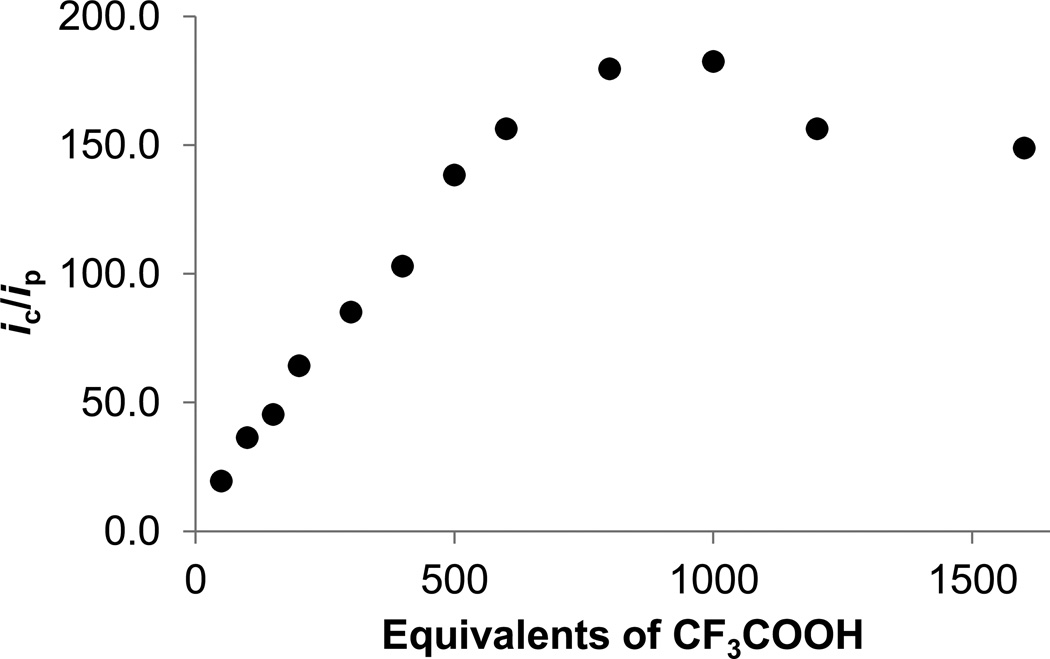

By the standards of synthetic catalysts, [t-H1NH]+ is a fast catalyst, but [t-H1NH2]2+ appears to be even faster. Thus, in the presence of strong acids such as HBF4·Et2O or trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), a catalytic wave is observed at −1.22 V. This lower potential process is assigned to electrocatalysis by [t-H1NH2]2+, the ammonium-terminal hydride that predominates in the presence of such strong acids. Monitoring the current at −1.2 V, the variation of ic/ip vs [TFA] was found to be linear over 20 – 300 equiv. The maximum ic/ip of ~167 corresponds to an estimated turnover frequency of 58,000 s−1 (Figures 8, 9).

Figure 8.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 0.5 mM solution of 1NH (0 °C, 0.125 M [Bu4N]BArF4, CH2Cl2, scan rate = 1.0 V/s, GC working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag wire pseudo reference electrode, Fc internal standard) recorded with increasing equiv of CF3CO2H.

Figure 9.

Dependence of ic/ip on equiv of CF3CO2H added to a 0.5 mM solution of 1NH, with [Bu4N]BArF4 as supporting electrolyte.

Hydrogen evolution by electrolysis is typically subject to substantial isotope effects,36 and this aspect was observed with 1NH. The dependence of the ic/ip vs [ClCH2CO2D] is linear up to 60 equiv of acid, and reaches a plateau at ic/ip of 18, which corresponds to a turnover frequency of 420 s−1. The rate decreased ten-fold, compared to that exhibited in experiments that utilize ClCH2CO2H (maximum ic/ip = 66, k = 4500 s−1). Similarly, when CF3CO2D is substituted for CF3CO2H, k decreases by about 15%, with the maximum ic/ip = 106 and k = 6600 s−1.

Electrocatalysis experiments were conducted with the bridging hydride [µ-H1NH]+ also at 0 °C. At −1.8 V, the current increases with the addition of ClCH2CO2H. A plot of ic/ip vs [H+] is linear over the range 2–50 equiv of ClCH2CO2H, but begins to plateau at 60 equiv, corresponding to an ic/ip of ~10 (Figure 7). The catalytic rate is estimated as 20 s−1. The µ-hydride operates at an overpotential of 0.9 V, which is 0.2–0.4 V higher than the overpotentials for the terminal species.

Conclusions

Hydrogen evolution by biomimetic diiron dithiolates is accelerated by the amine cofactor, to which the hydride ligand must be adjacent. The protonated derivatives of 1NH and 2 exhibit very different catalytic properties, although the neutral complexes are almost indistinguishable spectroscopically. Thus, the adt and pdt ligands have comparable inductive effects resulting in complexes of very similar thermodynamic properties. The crystallographic analysis of [t-H1NH2]2+ provides a unique insight into a probable intermediate in both the evolution and oxidation of hydrogen. The specific point of interest is the short distance between the hydride and the proton on the ammonium cofactor. The implied dihydrogen bonding provides a snapshot of a step in the formation and scission of a dihydrogen molecule at the active site of the [FeFe]-H2ase.

An attractive NHδ+---Hδ− interaction may be relevant to the small separation between the first and second protonation constants, estimated at only 102 in CH2Cl2 solution. In comparison with [t-H1NH]+, the [t-H1NH2]2+ isomerizes to the µ-hydride more slowly, which may result from this interaction.

The basicities of two sites - the terminal Fe center and the amine are closely balanced. In CH2Cl2 solution, Fe is more basic, but the equilibrium shifts in the presence of hydrogen-bond acceptors as demonstrated with the influence of Bu4NBF4 on this equilibrium. The lower basicity of a terminal Fe site vs the Fe-Fe bond is indicated by the conversion of mixtures of ammonium cations and 1NH into [µ-H1NH]+ under conditions where [t-H1NH]+ is undetectable. A sequence of three processes is invoked to explain the formation the µ-hydride under these conditions: (i) N-protonation, albeit unfavorable, (ii) tautomerization of ammonium species to the terminal hydride [t-H1NH]+, and (iii) isomerization of [t-H1NH]+ to [µ-H1NH]+. The pKa of [t-H1NH]+ is estimated at 16, and the pKa of [µ-H1NH]+ is > 18.6 (MeCN scale). Being a stronger acid, [t-H1NH]+ is more easily reduced than is [µ-H1NH]+.

For both the pdt and adt derivatives, the terminal hydrides reduce at potentials that are 100 – 200 mV more positive than the corresponding bridging hydrides. The difference in reduction potentials between the isomeric hydrides is proposed to reflect differences in the localization of the reduction. In the case of the µ-hydride isomer, reduction is likely more delocalized between the two equivalent Fe atoms.38 When the hydride is bound to a single Fe atom, reduction likely occurs at the non-hydride containing Fe atom.39 The crystallographic results presented above indicate how this reduction could induce the formation of a mixed valence dihydrogen complex (eq 1). This scenario underscores the role of electron transfer, perhaps PCET,40 in HER. Upon reduction, hydrogen evolution would produce the mixed valence derivative, analogous to the Hox state of the enzyme (Scheme 3).

|

(1) |

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for proton reduction catalyzed by [t-H1NH]+. Two subcycles are shown for strong and weak acids.

In HER catalyzed by [µ-H1NH]+, it is apparent that 1NH is not regenerated. Otherwise, we would have observed increased rates during the electrolysis since [t-H1NH]+ is such an active catalyst. We conclude therefore that the µ-hydride ligand in [µ-H1NH]+ is a spectator. A related mechanism was invoked by Talarmin for catalysis by [Fe2(pdt)( µ-H)(CO)4(dppe)]+.41

Although the bio-inspired complexes described in this report are highly active proton reduction catalysts,42 challenges remain. These biomimetic catalysts suffer from relatively negative reduction potentials leading to high overpotentials.1 One possible solution involves incorporation of redox-active center to mediate the proton-coupled electron transfer that is implicated for the breaking and making of the H-H bond.40

Experimental

Reactions were typically conducted using Schlenk techniques at room temperature. Most reagents were purchased from Aldrich and Strem. Solvents were HPLC-grade and dried by filtration through activated alumina or distilled under nitrogen over an appropriate drying agent. HBF4·Et2O (Sigma-Aldrich) was supplied as 51–57% HBF4 in Et2O (6.91 – 7.71 M). [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 was prepared by literature methods.43 [Bu4N]PF6 was purchased from GFS Chemicals and was recrystallized multiple times by extraction into acetone followed by precipitation by ethanol. 1H NMR spectra (500 and 400 MHz) are referenced to residual solvent referenced to TMS. 31P{1H} NMR spectra (202 or 161 MHz) were referenced to external 85% H3PO4. FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer. CF3CO2D was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. CCl2HCO2D was prepared by treating the acid in D2O,

Fe2(adtNH)(CO)4(dppv)

A solution of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)644 (175 mg, 0.45 mmol) and dppv (179 mg, 0.45 mmol) in 15 mL of toluene was treated with a solution of anhydrous Me3NO (34 mg, 0.45 mmol) in ca. 5 mL of MeCN. Bubbles appeared, and the reaction mixture darkened. After heating the mixture at reflux for 5 h, the FT-IR spectrum indicated complete conversion to product. Solvent was removed under vacuum, and the product was extracted into 5 mL of CH2Cl2. Addition of 50 mL of hexane precipitated the product. Yield: 0.260 g (80%). FT-IR, 1H NMR, and 31P NMR results matched reported values.24

Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2, (1NH)

A solution of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)4(dppv) (400 mg, 0.55 mmol) in 40 mL of toluene was treated with dppv (872 mg, 2.2 mmol) in 10 mL of toluene. The mixture was irradiated at 365 nm until the conversion was complete (~24 h) as indicated by IR spectroscopy. The solvent was removed in vacuum, and the product was extracted into ~3 mL of toluene. The green product precipitated upon addition of methanol to the toluene extract. The product was then re-extracted into ~2 mL of CH2Cl2, and the product precipitated as an olive-green powder upon the addition of 100 mL of hexanes. Yield: 150 mg (26%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 8.1 – 7.0 (m, 40H, P(C6H5)2), 2.3 (s, 4H, (SCH2)2NH). 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 92. 31P NMR (CD2Cl2, −70 °C): δ 102.6, 93.4, 92.2, 88.6. FT-IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1888, 1868 cm−1. Anal. Calcd for C56H49Fe2O2NP4S2·CH2Cl2·CH3OH (found): C, 58.8 (58.15); H, 4.68 (4.63), N 1.18 (1.10). Diffraction quality crystals were grown at −20 °C from a CH2Cl2 solution of 1 layered with pentane.

[HFe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]BArF4, ([t-H1NH]BArF4), [Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2]BArF4 ([µ-H1NH]BArF4), and [Fe2(adtNH2)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2](BArF4)2 ([µ-H1NH2](BArF4)2)

In a J. Young NMR tube, ~ 0.5 mL of CD2Cl2 was distilled and frozen onto 1NH (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) and [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) in a −78 °C bath. The sample was then thawed and analyzed by NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2, −80 °C): δ −4.2 (t, Fe-H, 2JPH = 73 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR (242 MHz, CD2Cl2, −40 °C): δ 103.2 (s), 94.5 (s), 84.0 (s), 75.1 (s). Selective 31P decoupling of the 1H NMR verified that only the signals at δ 94 and 84 were coupled to the hydride, presumably these correspond to dibasal phosphines attached to the FeH center. At the sample temperature of −10 °C, a triplet of triplets at δ −14.8 (Fe-µH, JPH = 25, 5 Hz) appears in the 1H NMR spectrum, and singlets at δ 91.0 and 90.8 appear in the 31P NMR spectrum, which are assigned to sym-[µ-H1NH]BArF4. Upon warming the sample to 20 °C, signals corresponding to [t-H1NH]BArF4 disappear, and only sym-[µ-H1NH]BArF4 is observed. After ~10 min. at 20 °C, an additional 1H NMR multiplet at δ-13.7 appears, and four 31P NMR singlets appear at δ 88.2, 85.7, 82.7, and 77.3, which are assigned to unsym-[µ-H1NH]BArF4. After ~12 h at room temperature, the ratio of the sym:unsym isomers is 1:5.

Upon addition of a second equiv of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) to the solution, the 1H NMR spectrum showed a triplet of triplets at δ −15.5 (Fe-µH, JPH = 25, 5 Hz) assigned to sym-[µ-H1NH2](BArF4)2 and a multiplet at δ −14.3 assigned to unsym-[µ-H1NH2](BArF4)2. Additionally, in the 31P NMR spectrum signals are observed at 91.3 and 88.7 (sym-[µ-H1NH2](BArF4)2) and at δ 92.3, 86.0, 82.4, and 79.0 (unsym-[µ-H1NH2](BArF4)2). The two isomers are present in a ratio of 5:1 sym:unsym. An IR spectrum of the CD2Cl2 solution features bands at 1967 and 1985 cm−1.

[t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(dppv)2](BArF4)2, [t-H1NH2] (BArF4)2

In a J. Young NMR tube, ~ 0.5 mL of CD2Cl2 was distilled onto 1NH (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) and [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (10 mg, 0.010 mmol). The J. Young tube was then gently warmed to near −78 °C before analysis by low temperature NMR spectroscopy. High field 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2, −40 °C): δ - 4.95 (t, Fe-H, 2JPH = 72 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR (242 MHz, CD2Cl2, −40 °C): δ 98 (s), 89 (s), 76 (s), 74 (s). Decoupling experiments verified that the high field 1H NMR signal is coupled to the 31P NMR signals at δ 89 and 74.

Crystallization of [t-HFe2(adtNH2)(CO)2(dppv)2]BF4)2

Crystals were obtained by treating a CH2Cl2 solution of 1NH, at 0 °C, with two equiv of HBF4·Et2O and layering with cold pentane. Storage at −20 °C gave dark brown crystals.

[Fe2(adtNH)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]BArF4, [µ-H1NH]BArF4

A 10 mL solution of 1NH (35 mg, 0.03 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was treated with a 5-mL solution of [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (33 mg, 0.03 mmol) in CH2Cl2. Within 5 min., the solution color changed from green to brown. After stirring at room temperature for 22 h, the solution was concentrated to ~ 5 mL, and the brown product was precipitated with addition of 20 mL of Et2O. IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 1948, 1969 (sh) cm−1. 1H and 31P NMR data match those described above. Anal. Calcd for C9H62BF24Fe2NO2P4S2·2CH2Cl2·C4H10O (found): C, 51.89 (52.19); H, 3.52 (3.13); N 0.64 (0.76).

Protonation of Fe2(adtNH)(CO)2(dppv)2 with 1.5 equiv of [H(OEt2)2] BArF4

In a J. Young NMR tube CD2Cl2 was distilled onto 1NH (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) and [H(OEt2)2]BArF4 (7.5 mg, 0.0075 mmol). The J. Young tube was then gently warmed to near −78 °C before analysis by low temperature NMR spectroscopy. High field 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2, −40 °C): δ - 4.95 (Fe-H, 2JPH = 72 Hz), −4.2 (Fe-H, 2JPH = 73 Hz).

Effect of [Bu4N]BF4 on Equilibrium between Tautomers [t-H1NH]+ and [1NH2]+

A 7 mM solution of [t-H1NH]BArF4 was prepared by dissolving 1NH (15 mg, 0.014 mmol) and [H(Et2O)2]BArF4 (15 mg, 0.014 mmol) in 2 mL of CH2Cl2, which had been pre-cooled to −78 °C. Aliquots of a 0.6 M [Bu4N]BF4 solution were added to the solution. After each addition, 0.1 mL aliquots were removed and immediately analyzed by IR spectroscopy.

[t-HFe2(pdt)(µ-CO)(CO)(dppv)2]BF4, [t-H2]BF4

A dark green solution of 2 (205 mg, 0.192 mmol) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was treated at −40 °C with HBF4·Et2O (5 mL 0.04 M, 0.2 mmol). The resulting darker green solution was then diluted with 100 mL of cold (−78 °C) Et2O, producing a green precipitate. The precipitate was collected by filtration at −78 °C, washed with 2×10 mL of Et2O, and dried under vacuum, prior to storage at −30 °C. Yield: 140 mg (63%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ −3.5 (t, Fe-H, 2JPH = 76 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 99 (s), 91 (s), 86 (s), 68 (s). Selective 31P decoupled 1H NMR verified that the signals at δ 91 and 86 coupled to the hydride signal. FT-IR (CH2Cl2, cm−1): νCO = 1965, 1905, 1988.

[Fe2(pdt)(µ-H)(CO)2(dppv)2]PF6, [µ-H2]PF6

In a 250-mL Schlenk flask, a dark green solution of 1 (200 mg, 0.187 mmol) in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was treated at room temperature with a solution of 2.0 M HCl in Et2O (0.2 mL, 0.2 mmol). Solvent was removed under vacuum, and the solid was redissolved in MeOH. The product was precipitated as its PF6− salt by addition of ca. 5 mL of a saturated aqueous solution of NH4PF6. The brownish precipitate was then transferred anaerobically onto a Celite plug in a chromatography column where it was washed with 6 × 30 mL of H2O and 6 × 30 mL of Et2O. The product was then extracted off the Celite with CH2Cl2, and solvent removed under vacuum. The product was dissolved with 5 mL of CH2Cl2, which was diluted with 5 mL of MeOH. Addition of 50 mL of hexane to this solution yielded a brown powder, which was collected by filtration and dried. Yield: 170 mg (75%). High-Field 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ - 14.5 (dddd, µ-H, JPH1 = 24, JPH2 = 19, JPH3 = 10 Hz), −15.6 (tt, µ-H, JPH1 = 24, JPH2 = 6 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 89.6 (s), 89.6 (s), δ 76.7 (s), 82.8 (s), 84.2 (s), 87.8 (s). FT-IR (CH2Cl2, cm−1): νCO = 1963, 1951. Anal. Calcd for C57H51F6Fe2O2P5S2 (found): C, 56.45 (56.28); H, 4.24 (4.28); Fe 9.21 (8.79).

Electrochemistry

Electrochemical experiments were carried out on CH Instruments Model 600D Series Electrochemical Analyzer or a BAS-100 Electrochemical Analyzer. Cyclic voltammetry experiments were conducted using a 10-mL one-compartment glass cell with a tight-fitting Teflon top. The working electrode was a glassy carbon (GC) disk (diameter = 3.00 mm). A silver wire was used as a quasi-reference electrode, and the counter electrode was a Pt wire. Ferrocene was added as an internal reference, and each cyclic voltammogram was referenced to this Fc0/+ couple = 0.00 V. iR compensation was applied to all measurements using the CH Instruments or BAS software. Cell resistance was determined prior to each scan, and the correction applied to the subsequently collected cyclic voltammogram. During prolonged experiments, additional solvent was added to compensate for evaporative loss. Between scans, the solution was purged briefly with N2 and the working GC electrode was removed and polished. The duration of typical electrochemical titrations was 30 min. For all experiments, the electrolyte solution was prepared and sparged in the cell, which was fitted with electrodes. A CV of the electrolyte was collected prior to the addition of Fe2 compound, in order to check the purity of the electrolyte. The diiron compound was then dissolved in the electrolyte solution and transferred to the cell.

Due to their tendency to isomerize above 0 °C, [t-H1NH]+, [t-H1NH2]2+, and [t-H2]+ were generated in-situ. The corresponding bridging hydrides were isolated as their BF4− salts prior to electrochemical experiments. All electrochemical experiments were conducted at 0 °C.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM61153). This work was also supported in part by the ANSER Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award Number DE-SC0001059. We thank Danielle Gray for collecting crystallographic data.

Footnotes

The barriers for ring flipping for the Fe2(xdt)(CO)4(dppv) (xdt = pdt ((SCH2)2CH22−), odt ((SCH2)2O2−), and adt ((SCH2)2NH2−) from DNMR studies (coalescence temperatures, K): pdt 42 (225), odt 43.3 (235), adt 55.9 kj/mol (293). The variation reflects increased stiffness of the two C-N bonds in the adt backbone, as a consequence of the interaction of the amine lone pair and the C-S σ* orbitals. M. T. Olsen, unpublished results.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Results from NMR, IR spectra, X-ray crystallographic, and electrochemical analyses. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Maria E. Carroll, School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801

Bryan E. Barton, School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801

Thomas B. Rauchfuss, School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801.

Patrick J. Carroll, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

REFERENCES

- 1.Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4273. doi: 10.1021/cr050195z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cammack R, Frey M, Robson R. Hydrogen as a Fuel: Learning from Nature. London: Taylor & Francis; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontecilla-Camps JC, Amara P, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y, Volbeda A. Nature. 2009;460:814. doi: 10.1038/nature08299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tard C, Pickett CJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2245. doi: 10.1021/cr800542q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1974. doi: 10.1021/ar900110c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bullock RM, editor. Catalysis without Precious Metals. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters JW, Lanzilotta WN, Lemon BJ, Seefeldt LC. Science. 1998;282:1853. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey M. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:153. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020301)3:2/3<153::AID-CBIC153>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silakov A, Wenk B, Reijerse E, Lubitz W. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:6592. doi: 10.1039/b905841a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tschierlei S, Ott S, Lomoth R. Ener. & Envir. Sci. 2011;4:2340. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nametkin NS, Tyurin VD, Kukina MA. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1986;55:439. [Google Scholar]; Linford L, Raubenheimer HG. Adv. Organometal. Chem. 1991;Volume 32:1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt M, Contakes SM, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9736. [Google Scholar]; Le Cloirec A, Davies SC, Evans DJ, Hughes DL, Pickett CJ, Best SP, Borg S. Chem Commun. 1999;2285 [Google Scholar]; Lyon EJ, Georgakaki IP, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:3178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gloaguen F, Lawrence JD, Schmidt M, Wilson SR, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12518. doi: 10.1021/ja016071v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gloaguen F, Rauchfuss TB. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:100. doi: 10.1039/b801796b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton BE, Olsen MT, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16834. doi: 10.1021/ja8057666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakazawa H, Itazaki M. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2011;33:27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews SL, Heinekey DM. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:9746. doi: 10.1021/ic1017328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruschi M, Greco C, Kaukonen M, Fantucci P, Ryde U, De Gioia L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3503. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ezzaher S, Capon JF, Gloaguen F, Petillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Pichon R, Kervarec N. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:3426. doi: 10.1021/ic0703124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton BE, Zampella G, Justice AK, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3011. doi: 10.1039/b910147k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barton BE, Rauchfuss TB. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:2261. doi: 10.1021/ic800030y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Vlugt JI, Rauchfuss TB, Whaley CM, Wilson SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16012. doi: 10.1021/ja055475a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singleton ML, Jenkins RM, Klemashevich CL, Darensbourg MY. C. R. Chim. 2008;11:861. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter A, Zsolnai L, Huttner G. Z. Naturforsch. 1982;37b:1430. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert JB, Featherman SI. Chem. Rev. 1975;75:611. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justice AK, Zampella G, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, van der Vlugt JI, Wilson SR. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:1655. doi: 10.1021/ic0618706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ott S, Kritikos M, Akermark B, Sun L, Lomoth R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1006. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Schwartz L, Eilers G, Eriksson L, Gogoll A, Lomoth R, Ott S. Chem. Commun. 2006:520. doi: 10.1039/b514280f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence JD, Li H, Rauchfuss TB, Benard M, Rohmer MM. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:1768. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010504)40:9<1768::aid-anie17680>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basallote MG, Besora M, Castillo CE, Fernández-Trujillo MJ, Lledós A, Maseras F, Máñez MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6608. doi: 10.1021/ja070939l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das P, Capon JF, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Muir KW. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:8203. doi: 10.1021/ic048772+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsen MT, Bruschi M, De Gioia L, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12021. doi: 10.1021/ja802268p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho NN, Bau R, Mason SA. J. Organometal. Chem. 2003;676:85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Custelcean R, Jackson JE. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:1963. doi: 10.1021/cr000021b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izutsu K. Acid-Base Dissociation Constants in Dipolar Aprotic Solvents. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felton GAN, Mebi CA, Petro BJ, Vannucci AK, Evans DH, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:2681. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Justice AK, De Gioia L, Nilges MJ, Rauchfuss TB, Wilson SR, Zampella G. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:7405. doi: 10.1021/ic8007552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felton GAN, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL, Evans DH. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:9181. doi: 10.1021/ic060984e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MA, Carey AA. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fourmond V, Jacques PA, Fontecave M, Artero V. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:10338. doi: 10.1021/ic101187v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jablonskya A, Wright JA, Fairhurst SA, Peck JNT, Ibrahim SK, Oganesyan VS, Pickett CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18606. doi: 10.1021/ja2087536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lever ABP. Inorg. Chem. 1990;29:1271. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8098. doi: 10.1021/ja201731q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Camara JM, Rauchfuss TB. Nature Chem. 2012;4:26. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ezzaher S, Capon JF, Dumontet N, Gloaguen F, Petillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2009;626:161. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helm ML, Stewart MP, Bullock RM, Rakowski DuBois M, DuBois DL. Science. 2011;333:863. doi: 10.1126/science.1205864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cheah MH, Tard C, Borg SJ, Liu X, Ibrahim SK, Pickett CJ, Best SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11085. doi: 10.1021/ja071331f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brookhart M, Grant B, Volpe AF. Organometallics. 1992;11:3920. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zaffaroni R, Rauchfuss TB, Gray DL, De Gioia L, Zampella G. to be submitted [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.