Abstract

The correlation of discharges between single neurons can be revealing about the computations and network properties of neuronal populations during the performance of cognitive tasks. In recent years, dynamic modulation of neuronal correlations by attention has been revealed during the execution of behavioral tasks. Much less is known about the influence of learning and performing a task itself. We therefore sought to quantify the correlated firing of simultaneously recorded pairs of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of naïve monkeys that were only required to fixate, and to examine how this correlation was altered after learning to perform a working memory task. We found that the trial-to-trial correlation of discharge rates between pairs of neurons (noise correlation) differed across neurons depending on their responsiveness and selectivity for stimuli even before training in a working memory task. After learning to perform the task, correlated firing decreased overall, though effects varied based on the functional properties of the neurons. The greatest decreases were observed comparing populations of neurons that exhibited elevated firing rate during the trial events, those that had more similar spatial and temporal tuning, and more so for pairs of between Fast Spiking (putative interneurons) and Regular Spiking (putative pyramidal) neurons than pairs of Regular Spiking neurons themselves. Our results demonstrate that learning and performance of a cognitive task alters the correlation structure of neuronal firing in the prefrontal cortex.

Keywords: monkey, neurophysiology, principal sulcus, learning

INTRODUCTION

Discharge rates of cortical neurons are highly variable from trial to trial during the presentation of identical sensory stimuli or execution of motor movements to the same targets, a phenomenon that is insightful about the organization of neural circuits (Shadlen & Newsome, 1998; Faisal et al., 2008). Furthermore, trial-to-trial variability is weakly but significantly correlated across neurons (Gawne & Richmond, 1993; Lee et al., 1998; Maynard et al., 1999; Constantinidis & Goldman-Rakic, 2002; Kohn et al., 2009). This correlated variability (commonly referred to as noise correlation or spike-count correlation) has important implications about the nature of information encoding in neuronal populations (Averbeck et al., 2006). It has been argued that correlated noise places limits on the information that can be extracted by pooling responses from multiple neurons (Zohary et al., 1994), although this may also depend on how signals are pooled (Abbott & Dayan, 1999; Romo et al., 2003) and the heterogeneity of the neuronal population (Ecker et al., 2011). Obtaining experimental measures of variability and correlation has in any case been very valuable for the insight it offers on neuronal networks (Cohen & Kohn, 2011).

More recently, it has been recognized that the degree of correlated firing is not a fixed property of neuronal networks (Renart et al., 2010). For example, noise correlation varies dynamically depending on whether the two neurons are pooled together for the same computation (Cohen & Newsome, 2008; 2009). These results indicate that neuronal correlation varies dynamically as a result of cognitive operations, and for this reason it can be an important indicator of neuronal computations and cognitive states.

Virtually all estimates of correlation in areas of the association cortex have been obtained in animals trained to perform a behavioral task (Cohen & Kohn, 2011). In face of the recent findings suggesting modulation of correlation by cognitive factors, the reported values on which models of neuronal organization have been based are likely to have been influenced by the cognitive operations imposed by the task. We were therefore motivated to analyze neuronal recordings in the prefrontal cortex of monkeys before they had been trained to perform the task at all. We compared these with recordings obtained from the same animals after they were trained to perform a working memory task (Meyer et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2011). Importantly, these experiments used identical stimuli presented with the same timing. We were therefore able to quantify the correlation of the prefrontal network absent the effect of mental operations dictated by the task, and to reveal the nature of changes on these variables in the same animals after they had been trained to perform a working memory task.

METHODS

Three male, rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 5–12 kg were used in this study. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health, as reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Measures to minimize animal pain and discomfort included aseptic surgeries under isoflurane anesthesia, postoperative opioid anelgesics, and environmental enrichment under the oversight of the institutional environmental enrichment coordinator.

Neuronal recordings were obtained from the lateral prefrontal cortex of the monkeys (Fig. 1A) before and after training in a working memory task, as described in more detail before (Qi et al., 2011). Recordings were obtained with multiple (up to 8), independently movable tungsten microelectrodes that were advanced into the cortex with a microdrive system (EPS drive, Alpha-Omega Engineering, Nazareth, Israel). We used glass-coated 250 μm diameter electrodes with an impedance of 1 MΩ at 1 kHz (Alpha-Omega Engineering, Nazareth, Israel) and epoxylite-coated 125 μm diameter electrodes with an impedance of 4 MΩ at 1 KHz (FHC Bowdoin, ME). Neural signals were band-pass filtered between 500 Hz and 8 kHz and recorded with a modular data acquisition system at a 25 μs sampling resolution (APM system, FHC, Bowdoin, ME). All neurons isolated during advancement of the electrodes were sampled, with no effort to pre-screen them based on functional properties. Data analysis was performed using the MATLAB computational environment (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

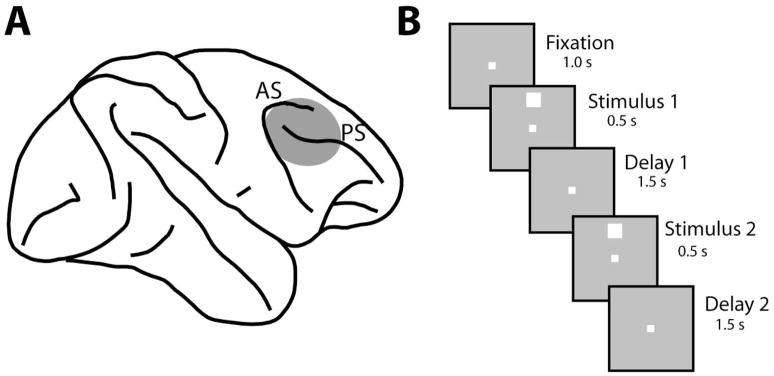

Figure 1.

A) Schematic diagram of the monkey brain with the area of recordings highlighted. Abbreviations: AS, Arcuate Sulcus; PS, Principal Sulcus. B) Successive frames illustrate the sequence of stimulus presentations. Stimuli were white squares presented on a 3×3 grid, with a spacing of 10° from each other. In the pre-training stage the animals were rewarded for maintaining fixation after the end of the second delay period. After training, the animals were presented with two choice targets (not shown) and were required to saccade to a green target if the two stimuli were matching and to a blue target otherwise.

Behavioral Task

Neuronal data were compared at two stages of recordings. In the first stage (prior to working memory training), the monkeys were only required to maintain fixation while stimuli were presented on a screen (Fig. 1B). The stimulus appeared for 500 ms and was followed by a delay period that lasted for 1.5 s. After the delay period, a second white square appeared either at the same location, or a different (typically diametric) location for 500 ms. This was followed by a second 1.5 s delay period. The stimuli analyzed here were 2° white squares that appeared randomly at any of 9 locations arranged on a 3 × 3 grid; the distance between adjacent stimulus locations was 10°. All stimuli were presented using in-house software (Meyer & Constantinidis, 2005). After recordings were obtained in this stage, the animals were trained to perform a spatial working memory task. The stimuli and timing of presentation were identical before and after working memory training, allowing us to compare neuronal properties between stages. A second set of recordings was then obtained, after training had been completed. Data from correct trials only are presented in this paper. Typically 20 trials were recorded for each cue stimulus condition (180 trials from each neuron studied).

Neuron Analysis and Classification

Recorded action-potential waveforms were sorted into separate units using an automated cluster analysis method based on the KlustaKwik algorithm (Harris et al., 2000). A neuron’s spike width was determined by calculating the distance between the two troughs of the average waveform. We distinguished between Fast Spiking (FS – putative interneurons) and Regular Spiking (RS – putative pyramidal) neurons based on previous analysis (Constantinidis & Goldman-Rakic, 2002; Qi et al., 2011); units were classified as FS if they exhibited as spike width of ≤550 μs and RS if they exhibited a spike width of ≥575 μs (see Fig. 2 in Qi et al., 2011). We should note that spike width measured extracellularly is not a precise indicator of neuron type; motor and premotor neurons that project to the cerebrospinal tract have been recently shown to display thin spikes (Vigneswaran et al., 2011).

Nonetheless, we observed systematic differences between pairs of these types of neurons in our prefrontal recordings and errors in classification are likely to dilute differences between the populations of pyramidal neurons and interneurons. Firing rate of all units was determined in each task epoch. We identified neurons that responded to the visual stimuli, evidenced by significantly elevated firing rate in the 500 ms interval of a stimulus presentation, compared to the 1 s interval of fixation (paired t-test, α=0.05). Neurons with significantly elevated or reduced activity in other task epochs were similarly identified. Firing rate comparisons always included the entire interval of the stimulus presentation (which lasted for 0.5 s) or the entire delay period (which lasted for 1.5s). The functional properties of neurons responding to these stimuli have been described in detail elsewhere (Meyer et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2011). In addition, here we examine the correlation of neurons that did not respond to any of the stimuli, based on these statistical criteria.

Noise Correlation

Noise correlation was computed for pairs of neurons recorded simultaneously from separate electrodes, spaced 0.5–1 mm apart from each other. Recordings of neuron pairs selected for analysis were required to contain at least 1000 spikes in total, and no less than 100 spikes in each neuron, to avoid artificially low noise correlation values for neurons with low firing rate, when inadequate numbers of trials are available (Cohen & Kohn, 2011). A total 2678 neurons pairs before training and 1730 pairs after training recorded at distances 0.5–1 mm apart met these criteria. Some neuron pairs after training were obtained from electrodes positioned at distances <0.5 mm or >1 mm from each other (collected for purposes unrelated to this analysis) and these were not used for any of the pre- and post-training comparisons reported here. For each neuron, we computed the mean and standard deviation of firing rate across trials. We performed this calculation separately for the fixation period, stimulus presentation period, and delay period. For the stimulus presentation and delay periods we subtracted the mean value of each stimulus condition from the rate recorded in each trial and divided it by the standard deviation to provide a normalized estimate independent of stimulus (Zohary et al. 1994). We then computed the Pearson correlation coefficient between these normalized firing rate values.

Signal Correlation

The signal correlation represents an estimate of the similarity between the stimulus selectivity of two neurons (Cohen & Kohn, 2011). Signal correlation is defined here as the Pearson correlation coefficient of two neurons’ mean firing rates to the nine spatial stimuli, computed during the period of the first stimulus presentation. To avoid the confound of increased correlation by two neurons activated by the same stimuli with similar time course (Brody, 1998), we computed measures of noise correlation in the fixation period and examined their dependence on signal correlation, which was estimated based on spikes collected from the first stimulus presentation period.

Temporal Correlation

Temporal correlation is an estimate of similarity between the envelope of firing rates of two neurons across the time course of a behavioral trial (Constantinidis et al., 2001). We computed the temporal correlation as follows: Neuronal responses were pooled from all nine spatial stimuli. Averaged discharge rates were then computed in 0.5 s windows, spanning the fixation period, stimulus presentation epoch, delay period, match/nonmatch stimulus, and second delay period. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the responses of two neurons across corresponding time windows provided a measure of the similarity in temporal profile of activation for the neuron pair.

Cross-, Auto-Covariance

The cross-covariance of two neurons recorded simultaneously was computed as the product of their normalized spike counts, obtained from different trials. Across all trial lags, the cross-covariance function is in essence the cross-correlation of the two neurons’ spike count z-scores (Bair et al., 2001). The auto-covariance was calculated in the same fashion, using the product of spike counts of the same neuron, obtained from different trials. Cross and auto-covariance values were obtained separately from each pair, in each of the task epochs. Values from all pairs of neurons in each epoch were then averaged together.

RESULTS

Database

We analyzed neuronal activity from 1324 neurons recorded prior to training and 1351 neurons recorded after training in the working memory task from the prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1A) of three monkeys (Qi et al., 2011). After training, monkeys were required to view two stimuli presented in sequence and to determine whether they appeared at the same location or not (Fig. 1B). They indicated the match or nonmatch status of the stimuli by making an eye movement to a green or blue choice target that appeared after the presentation of the stimuli. Prior to training, the animals viewed the exact same stimuli, presented with an identical time course but no choice targets appeared at the end of the trial, and the monkeys were rewarded merely for maintaining fixation. We analyze here responses to the spatial set of stimuli, which involved white squares appearing at one of nine possible locations, spaced by 10° apart.

Prior to training, 565(43%) neurons responded to any aspect of the task with a significant change in firing rate over the baseline, 315 (24%) neurons responded to the visual stimuli with a significant elevation of firing rate and 232 neurons (18%) exhibited significantly elevated delay period activity. After training, 760 (56%) responded to any aspect of the task, 425 neurons responded to the stimuli (31%) and 449 exhibited delay period activity (33%). Simultaneous recordings from pairs of neurons recorded 0.5–1 mm apart provided a total of 2678 neuronal pairs before and 1730 pairs after training that exceeded the spike number criterion and were included in further analysis. Of these pairs, 950 consisted of neurons both of which exhibited significant responses during an aspect to the task prior to training (35%) and 807 (47%) pairs after training.

Correlated discharges across the time course of a trial

We first sought to investigate the correlated discharges in the naïve animals, prior to training (Fig. 2A). We relied on trial-to-trial correlation of firing rate deviations around the mean firing rate (also known as spike-count correlation or noise correlation) and examined pairs of neurons recorded from different electrodes separated by 0.5–1 mm from each other. Correlation measures decline as a function of distance between two neurons (Lee et al., 1998; Constantinidis & Goldman-Rakic, 2002) and we in fact observed this relationship in recordings obtained from electrodes at shorter than 0.5 and longer than 1 mm distances after training; the average (and standard error) of noise correlation for all pairs of neurons recorded from electrodes 0.2 – 0.5 mm apart was r = 0.080 ± 0.004, from electrodes 0.5 – 1 mm apart r = 0.034 ± 0.002, and from electrodes 1 – 1.5 mm apart, r = 0.030 ± 0.002. The dataset obtained from electrodes 0.5–1 mm apart provided a large number of pairs in both stages of recordings and allowed us to quantify and compare noise correlation in the same distance range before and after training.

Figure 2.

A) Average noise correlation is plotted for neuron pairs with significant responses to visual stimuli. Noise correlation was computed separately for the fixation period, stimulus periods, and delay periods following the stimulus presentation, in recordings conducted prior to (N=950 pairs) and after training (N=807 pairs). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. B) Time course of noise correlation. Gray bars represent the time of stimulus presentations; vertical line, the time of reward in the pre-training condition and the time of choice targets appearance in the post-training condition. Shaded area around each curve represents the standard error of the mean. Noise correlation was computed in 100 ms bin windows; differences in average noise correlation values compared to panel A are due to the difference in integration window. C) Distribution of noise correlation values computed during the stimulus period, for all pairs of neurons before and after training. D) Average noise correlation values are plotted for groups of neurons binned based on the geometric mean of firing rate during the first stimulus presentation period, before and after training.

The average correlation value we computed in the naïve monkeys across the fixation, two stimulus presentations and two delay periods was r = 0.061, for pairs of neurons that responded to the stimuli. Highest values of noise correlation were observed during the two delay periods and lowest values during the stimulus presentation periods (Fig. 2A); the difference between epochs was statistically significant (ANOVA test F4,4745=3.84, p<0.005). This increase in noise correlation towards the end of trial was confirmed when we computed noise correlation in a finer time scale, in successive 100 ms windows that spanned the behavioral trial (Fig. 2B). We should note that prior to training, no eye movement or other motor response was required by the animals at the end of the trial, therefore this increase in noise correlation could not be accounted for by motor preparation. Since the size of the integration window impacts the value of the computed noise correlation (Constantinidis & Goldman-Rakic, 2002; Averbeck & Lee, 2003) – which also explains the slightly lower values between the averages obtained from Fig. 2B and those shown in Fig. 2A – we repeated our epoch comparison by dividing the trial in ten successive windows of equal, 500 ms duration. A significant difference between these windows was again evident (ANOVA test, F9,9490 = 5.19, p<10−5). The estimate of noise correlation was not uniform across our sample; in fact, a wide distribution of values was observed for individual neuronal pairs (Fig. 2C).

After characterizing neuronal noise correlation prior to training, we proceeded to examine how it compares to the same measure obtained after training. It has been argued that decoding of information from population responses suffers as a consequence of correlated firing (Zohary et al., 1994). However neuronal correlations may be adjusted dynamically as a result of cognitive processes and lower levels of correlation have been reported for attended stimuli or stimuli for which a perceptual decision relies upon (Cohen & Newsome, 2008; Cohen & Maunsell, 2009). We therefore tested the effect of learning to execute a working memory task on noise correlations recorded using the same stimuli after training.

Overall, noise correlation declined after training (Fig. 2A). Average noise correlation for the population of neurons that responded to stimuli was r = 0.030 across the five task epochs, which represented a 51% decrease over the pre-training condition. A 2-way ANOVA comparing firing rate across task epochs and training phases revealed a highly significant effect of training (2-way ANOVA, F1,5270 = 26.9, p<10−5). The decrease in noise correlation was not uniform after training, as revealed by a significant interaction between task epoch and phase of training (2-way ANOVA, F4,8775 = 3.06, p<0.05). Large decreases were observed during the two stimulus presentations (62 and 63%), which can be thought of as analogous with the decrease in noise correlation observed for an attended over an unattended stimulus (Cohen & Maunsell, 2009; 2011). However, significantly lower levels of correlation were also observed in the fixation period, prior to the presentation of any stimuli (Tukey post-hoc test, p<0.05).

The non-uniform reduction in noise correlation after training was evident when we computed noise correlation in a time resolved fashion, which revealed a complex time course (Fig. 2B). Noise correlation declined prior to the appearance of either stimulus then rose in the delay period that followed it. In contrast, no such modulation was observed prior to training, although the timing of stimulus presentation was identical, and the timing of stimuli was equally predictable. Comparing the temporal structure of noise correlation across the trial before and after training showed very different envelopes of modulation; the Pearson correlation coefficient of the two time courses was −0.11, a non-significant relationship (t-test, t98 = −1.08, p>0.2). Noise correlation values remained highly variable across individual pairs after training (Fig. 2C).

The overall reduction in noise correlation we observed was present even though overall firing rate was higher after training (Qi et al., 2011), and higher levels of firing rate can inflate the apparent correlation of a pair of neurons (de la Rocha et al., 2007). We tested explicitly the effect of firing rate on noise correlation before and after training by computing the geometric mean of firing rate (square root of the product of the two neurons’ rates) for all pairs of neurons, and examining its relationship with noise correlation. Decreased noise correlation after training was consistently observed for groups of pairs equalized for firing rate (Fig 2D). To discount the effects of firing rate, we performed an analysis of covariance using the geometric mean of firing rate during the first stimulus presentation period as a covariate. This revealed a significant decrease in noise correlation after training (ANCOVA, F1,734 = 9.79, p<0.005). Similar results were obtained when we relied on the firing rate from other task periods to perform this analysis.

Correlation depending on stimulus responsiveness and selectivity

The analysis described so far was based on neurons that responded to stimuli, the subset of neurons whose response properties we examined in detail before and after training (Meyer et al., 2011; Qi et al., 2011). Since we previously determined that a higher percentage of neurons were activated after training (Qi et al., 2011), we wanted to ensure that this reduction in noise correlation levels was not an artifact of a greater percentage of neurons activated in the task. We therefore repeated the Noise Correlation analysis for all pairs of neurons, whether they exhibited task-related responses of any kind, or not (Fig. 3A). When we compared this with analysis in pairs obtained after training (Fig. 3A), a significant decrease in noise correlation was still evident (2-way ANOVA, F1,22030 = 25.6, p<10−5).

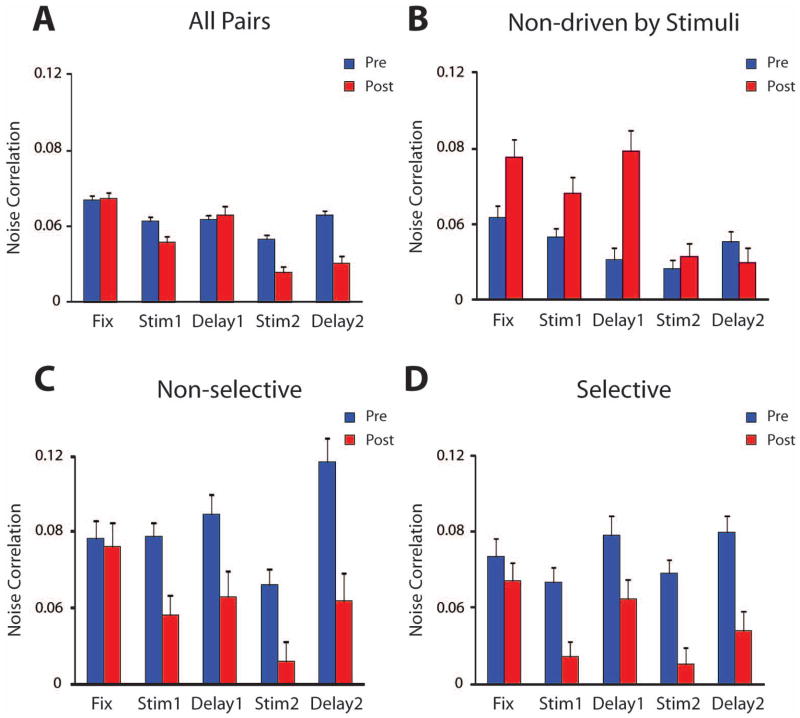

Figure 3.

Average (and standard error of the mean) noise correlation is computed for pairs of neurons with different properties, before and after training. A) All pairs of recorded neurons, whether they responded to the task or not (N=2678 pre; 1730 post-training). B) Pairs of neurons both members of which did not respond to the stimuli at any task period (N=476 pre; 260 post-training). C) Pairs of neurons driven by the stimuli but non-selective for the visual stimuli, in any task period (N=221 pre; 239 post-training). D) Pairs of neurons driven by the stimuli and selective for the nine stimulus locations (ANOVA, p<0.05) are shown (N=209 pre; 226 post-training).

We also examined separately pairs of neurons grouped based on their responsiveness and selectivity to stimuli. Prior to training, pairs of neurons neither member of which responded to any of the stimuli exhibited the lowest values of noise correlation (Fig. 3B), and those pairs whose neurons were not selective to the stimuli (Fig. 3C) exhibited the highest levels, a significant difference between groups (2-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test, p<10−5). These groups were also characterized by differences in firing rate. The population of neurons that was not significantly driven by stimuli exhibited the lowest firing rates (1.0 ± 0.05 sp/s mean and standard error in the fixation period) whereas those that were selective displayed higher firing rates (4.4 ± 0.5 sp/s) compared to neurons that were excited by stimuli (4.1 ± 0.2 sp/s). However a systematic different in noise correlation was present prior to training even when accounting for the effect of firing rate. An analysis of covariance comparing the groups of non-responsive and responsive neurons during the stimulus presentation period (where the disparity in firing rate was greatest) revealed a significant difference in average noise correlation, even after discounting the effect of firing rate (ANCOVA, F1,1423 = 9.67, p<0.005).

Decreases in noise correlation observed after training were not uniform across different groups of neurons. In fact, we found that average values of noise correlation significantly increased after training (2-way ANOVA, F4,3670 = 21.7, p<10−5) for pairs of neurons both members of which were not driven by any event in the task (Fig. 3B). This was true even though the firing rate of the respective populations differed only slightly before and after training (1.0 vs. 1.3 sp/s, respectively). On the other hand, neurons that did respond to the task but were not selective for the nine stimuli (1-way ANOVA, evaluated at the α=0.05 level) exhibited a similar pattern of decrease in noise correlation (Fig. 3C), to the population of neurons with stimulus selectivity (Fig. 3D), with an average 40% and 42% decrease in noise correlation for the two groups, respectively. A similar decrease in noise correlation (55%) was also observed for pairs of neurons consisting of one neuron that exhibited significant selectivity and one that did not (data not shown), which were also included in the population of pairs depicted in Fig. 2A.

Passive Fixation

Since execution of the task affected differentially noise correlation in different epochs and for pairs of neurons activated by different aspects of the task, it was important to also determine if this change was related to learning, or the execution of the task itself. For this reason, we collected data from a control condition after training, presenting the stimuli in a passive manner just as they were presented before training. Passive fixation cannot entirely discount the possibility that the subject is still performing the task mentally to some extent, and this has been a confounding factor of prior studies that relied on this procedure, rather than recording from naïve animals, as we have. Nonetheless, we collected neural activity under conditions of passive fixation as a way to determine the effects of actual execution of the task and as a way of comparing the effects of training with those of passive fixation, commonly used in the literature. In blocks of trials were stimuli were presented passively, monkeys were rewarded simply for maintaining fixation through the end of the second delay period, without choice targets being displayed. The monkeys were not explicitly cued about the passive nature of a trial, however these trials were presented in blocks where the choice targets were always absent. An initial block of passive trials was additionally presented first in order to condition the monkeys before the data collection commenced (Qi et al., 2011). We collected data from the same 165 pairs of neurons in blocks of trials when the animals were executing the task and during passive fixation (Fig. 4A). These pairs were recorded from electrodes spaced 0.2–0.3 mm apart, and overall noise correlation was higher than our sample recorded 0.5–1 mm apart as mentioned above, nonetheless these provide a controlled sample that allowed us to determine the effect of the execution of the task itself, after training. We found that in this sample, the average noise correlation across all epochs was essentially identical in the task-execution (r = 0.112) and passive conditions (r = 0.110). There was no significant difference in the effect of passive vs. active execution (2-way ANOVA, F1,1640 = 0.05, p>0.8) and no significant interaction between the factor of passive and active condition and the factor of task epoch (2-way ANOVA, F4,1640 = 1.93, p>0.1). We also compared noise correlation between the passive and active condition during the second stimulus presentation on trials when it was a match and in trials when it was a nonmatch, which elicit differential mean firing rates in a population of prefrontal neurons (Qi et al., 2012). We observed no significant difference in noise correlation between the match and nonmatch condition in either the active (t-test, t327 = 0.20, p>0.8) or the passive condition (t-test, t327 = 0.24, p>0.8). The results indicate that changes that occurred after training were not dependant on the execution of the task itself, but were associated with the learning that took place in the interim.

Figure 4.

Average noise correlation (and standard error of the mean) is shown for the passive and active condition, after training. A) Average noise correlation for neurons in each task epoch (N=165). B) Average noise correlation during the second stimulus presentation epoch, separately for match and nonmatch stimuli.

Neuron Type

Prior studies have demonstrated that cognitive factors can affect disproportionally the discharges of different neuronal types (Mitchell et al., 2007). We therefore wished to determine whether levels of noise correlation also depended on cell type. We distinguished between Fast Spiking (FS – putative interneurons) and Regular Spiking (RS – putative pyramidal neurons), based on spike width properties, as described previously (Qi et al., 2011). Cell type differentiation based on extracellular recordings is not entirely precise (Vigneswaran et al., 2011), nonetheless we observed systematic differences between pairs of FS and RS neurons. Prior to training, pairs of FS-RS neurons exhibited higher levels of noise correlation (r = 0.092) than RS-RS pairs (r = 0.056), a difference that was highly significant (2-way ANOVA, F1,4690 = 33.4, p<10−5). The population of FS neurons was also characterized by higher mean firing rates (6.1 ± 0.8 sp/s) than RS neurons (3.8 ± 0.2 sp/s). An insufficient number of FS-FS pairs were recorded simultaneously for this analysis and are not included in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

A) Average value of noise correlation (and standard error of the mean) computed separately for pairs of RS units, both members of which were putative pyramidal neurons (N=821 pre; N=653 post-training). B) Average value of noise correlation for FS-RS pairs, consisting of one putative interneuron and one putative pyramidal neuron (N=119 pre; N=147 post-training). C) Average value of noise correlation for RS-RS neuron pairs grouped based on signal correlation. D) Average value of noise correlation for RS-FS pairs grouped based on signal correlation.

After training, we found that noise correlation decreased for both groups of neurons (Fig. 5A, B). However a much greater decrease was observed for FS-RS (an average of 69% across the five task periods) than RS-RS pairs (46%). As a result, the difference in mean noise correlation between RS-RS pairs (r = 0.030) and RS-FS pairs (r = 0.029) was no longer statistically significant (2-way ANOVA, F1,3990 = 0.040, p>0.8). Since the consequences of correlated noise depend on the relative tuning of neurons in a pair, we also examined the noise correlation of FS-RS pairs grouped by the signal correlation of the two neurons in each pair. A decrease in noise correlation after training was evident for all groups of signal correlation. The results indicate that different neuronal types are characterized by different levels of correlation and that these populations are affected differentially by training to perform a cognitive task.

Tuning similarity

The magnitude of noise correlation is also known to depend on the similarity of stimulus responses between two neurons. We have previously shown that noise correlation is highest among pairs of prefrontal neurons with very similar spatial tuning in an Oculomotor Delayed Response Task (Constantinidis et al., 2001). To examine whether the same relationship is present prior to training, or whether this effect is entirely task-dependent, we computed the relationship between noise correlation and signal correlation, the latter being the correlation coefficient for average firing rate to the nine stimulus locations tested (Fig. 6A, C, blue points). To avoid the confound of co-variations in firing rate which can inflate the apparent correlation of neurons with similar responses to the same stimuli (Brody, 1998) we restricted the analysis in the fixation period, recorded prior to the appearance of the stimuli that were used to determine the signal correlation between two neurons. Indeed, we found that a significant relationship between signal correlation and noise correlation was present prior to training (regression analysis, F1,948 = 21.2, p<10−5).

Figure 6.

A) Noise correlation in the fixation period is plotted as a function of signal correlation (which was computed in the stimulus presentation period) for pairs of neurons with significant stimulus responses. Regression lines are shown for pairs of neurons recorded before (blue lines) and after training (red lines). B) Average noise correlation in the fixation period is plotted as a function of temporal correlation (which was computed based on averaged firing rates in successive 0.5 s periods). Regression lines are plotted as in A. C) Average values from panel A; neuron pairs were binned according to signal correlation values. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. D) Average values from panel B. E, F) Noise correlation as a function of both signal and noise correlation, before and after training, respectively. Color value in each bin represents the average noise correlation of neurons with signal and temporal correlation corresponding to this bin. Dark blue color indicates bins with no pairs.

Previous studies have shown that correlation between prefrontal neuronal discharges can also be predicted by the similarity in the neurons’ temporal envelope of activation across the different epochs of a trial (Constantinidis et al., 2002). We examined this relationship by determining the noise correlation as a function of temporal correlation between the averaged neuronal responses during the time course of a trial, relying again on the fixation interval so as to avoid the effect of firing rate co-variation (Fig. 6B, D). Our analysis determined that this relationship was also present before training in a working memory task (regression analysis, F1,948 = 65.1, p<10−5). Considering both the signal and temporal correlations simultaneously (Fig. 6E) confirmed that highest noise correlation was observed for neurons that shared the most similar signal and temporal correlation.

After training, we found the slope of the regression between signal and noise correlation (Fig. 6C) was significantly lower (F-test, F1,1753 = 5.74, p<0.05) than the equivalent slope prior to training. In other words, executing the task reduced disproportionately the correlation among neurons with similar tuning, which are presumably pooled together for a judgment about the location of the stimuli in the task; at the same time, noise correlation increased after training for neurons with the most dissimilar spatial tuning. This effect was accounted mostly be RS-RS pairs of neurons (Fig. 5C); RS-FS pairs (which were less numerous) showed decreases in noise correlation across all groups of signal correlation (Fig. 5D). It is notable that after training we observed a slight but significant decrease in overall stimulus selectivity (Meyer et al., 2011), and the change in correlation structure may be related to that effect. After training, similar spatial tuning accounts for a smaller percentage of shared functional inputs between neurons, which could have an effect of diluting the overall spatial selectivity of neurons.

With regards to the relationship of noise correlation with temporal correlation, the slopes of the two regression lines were very similar (β = 0.079 pre- vs. β = 0.072 post-training, a non-significant difference F-test, F1,1753 = 0.28, p>0.05), although overall levels of noise correlation were lower after training (Fig. 6B, D). Considering both the signal and temporal correlations simultaneously (Fig. 6E–F) confirmed that decreases in noise correlation after training were more pronounced among neurons with more similar tuning (upper right quadrant).

Covariance Structure

In order to examine the time scale of the noise correlation changes after training, we estimated the cross-covariance and auto-covariance of neuronal discharges (Bair et al., 2001). Average cross-covariance across all neuron pairs after training was essentially flat for trial lags other than zero (Fig. 7A–E). In contrast, cross-covariance before training appeared to exhibit some structure for trial lags extending approximately to ±10 trials around zero. In other words, increased firing by a neuron in a trial tended to correlate positively with increased firing rate by the second neuron of the pair, in prior and subsequent trials. This difference was not reflected in the auto-covariance average (Fig. 7F–J). To determine whether this represented a significant difference between the cross-covariance before and after training we computed the average value in the center 20 trials of the cross-covariance diagram (excluding trial 0) on a neuron by neuron basis and compared the equivalent values before and after training. Indeed, we found a significant decrease after training, which was most pronounced in the second stimulus and second delay period (t-test, t1755 = 4.75 and 5.51 respectively, p<10−5 in either case), and least pronounced in the stimulus period, where it failed to reach statistical significance (t-test, t1755 = 1.56, p>0.1). We also compared the cross-covariance structure of neuron pairs recorded in the active and passive condition, after training, however we observed no significant difference in the center 20 trials of the cross-covariance function for the second delay period (paired t-test, t164 = 0.54, p>0.5), or any other period.

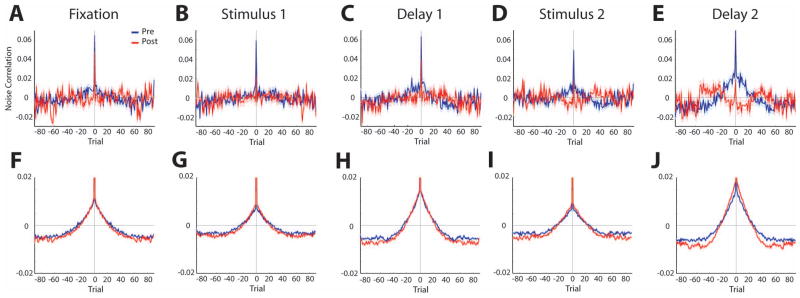

Figure 7.

A–E). Average cross-covariance of noise correlation is plotted as a function of trial number, in the fixation, first stimulus, first delay period, second stimulus, and second delay period, respectively. F-J) Average auto-covariance of noise correlation is plotted in the same fashion, in the same intervals.

Changes in cross-covariance structure are indicative of slow drifts in neuronal responsiveness that span several trials and have been attributed to factors such as fluctuations in alertness or arousal (Cohen & Kohn, 2011). In our dataset, these changes were most pronounced closer to the end of the trial and the impending delivery of reward for the naïve animals and diminished after training when the second stimulus attained a cognitive context on which the response will be based. However, this cross-covariance structure could not account for the entire decrease in noise correlation we observed after training. On average, the difference in the center 20 trials of the cross-covariance diagram represented 38% of the decrease in noise correlation that we detected after training. Subtracting this “slow”, 20-trial average cross-covariance value from the noise correlation value we obtained from each neuron pair, revealed a still significant decrease in correlation after training (t-test, t1755 = 6.0, p<10−5, for the first stimulus presentation period). The results indicate that after training, slow, correlated drifts in neuronal discharge essentially disappear, but that further decreases in noise correlation emerge, resulting in further decreases in correlation among neurons after the animal has been trained to perform the task.

DISCUSSION

Our study quantified the correlation of neuronal discharges in naïve animals, and determined how these relationships between neurons are sculpted by learning and performing a working memory task. In recent years, it has been recognized that cognitive factors such as attention affect the magnitude of neuronal correlation during the execution of behavioral tasks (Cohen & Kohn, 2011). It is thus important to understand how training in a task itself alters the correlation structure of neuronal populations. To address this question, we relied on comparison of neuronal discharges from a large sample of neurons in the same animals during execution of the spatial working memory task, and before they had been trained to perform the task at all, using the same stimuli. Prior to training, we observed differences in the absolute magnitude of noise correlation at different time epochs, and depending on the responsiveness and selectivity of the neurons studied. The effect demonstrates that noise correlation changes commonly observed at different task events may not be dependent on cognitive operations imposed by a task but can be simply driven by the stimuli. After training, overall noise correlation decreased. The magnitude of the changes we report (average of 51% decrease in noise correlation across epochs in Fig. 2A) was comparable to effects previously described between stimulus conditions in trained animals, which demonstrated the effect of cognitive factors on neuronal firing in the first place (Cohen & Maunsell, 2009). The changes in noise correlation were not uniform across our population, but they too varied across task epochs and neuronal populations. Our results have implications for models of cortical functional connectivity, information carrying capacity, and optimal decoding strategies.

Effects of Task Training on Noise Correlation

Theoretical studies have argued that co-variations in firing rate by neurons in a cortical area can limit the ability of downstream neurons to improve signal reliability by averaging responses from multiple neurons (Zohary et al., 1994). This conclusion may depend on the extraction algorithm, as comparing (subtracting) correlated inputs with opposite preferences can in essence overcome the problem of correlated noise (Johnson, 1980; Abbott & Dayan, 1999). In fact, positive correlations have been reported experimentally for neurons of opposite stimulus preference that could be compared during a discrimination decision (Romo et al., 2003). The heterogeneity of the neuronal population pooled may also affect the influence of correlated noise (Ecker et al., 2011). In addition, the absolute value of noise correlation may depend on experimental conditions used to obtain it. For example, a number of studies in area V1 have reported noise correlation values in the range of 0.1–0.2 (Reich et al., 2001; Kohn & Smith, 2005; Smith & Kohn, 2008; Poort & Roelfsema, 2009; Samonds et al., 2009); these stand in contrast with a recent report of near zero correlation values (Ecker et al., 2010), which would suggest that the limitation of pooling neuronal responses may be overestimated. The presence of noise correlation in a neuronal population may not have detrimental effects for all cognitive operations. Recently, noise correlation has been proposed as a mechanism that can increase performance in working memory tasks (Polk et al., 2012). In any case, obtaining experimental measures of noise correlation under different conditions is essential for constraining models of neuronal computations.

Our analysis determined that noise correlation during execution of a working memory task was considerably reduced compared to viewing the same stimuli passively. The result is analogous to lower correlation levels recently observed in area MST of animals that were trained to perform a perceptual discrimination task compared to naïve animals viewing the same stimuli (Gu et al., 2011). On the other hand, a previous study (in area MT) reported no significant difference in noise correlation after training of the same animals, relying on a small sample of neuron pairs recorded from the same electrode (Law & Gold, 2008). As a consequence of the reduced noise correlation we observed in our study, higher levels of information could be extracted by pooling large number of neurons, an effect that can improve selectivity.

Noise correlation reduction was not the only effect we observed after training. We have previously documented that there was an overall increase in mean firing rate after training (Qi et al., 2011) as well as a slight decrease in stimulus selectivity of single neuron firing. We also observed a concomitant decrease in neuronal discharge variability, as quantified by the Fano Factor of single neuron responses (Qi & Constantinidis, 2012), somewhat equivalent to effects of attention, observed in other cortical areas (Cohen & Maunsell, 2009). Collectively, the decrease in neuronal correlation and variability improve stimulus representation after training and may counteract the effects of reduced stimulus selectivity reflected in mean firing rate.

Neuronal tuning and neuron type

Our results revealed that noise correlation varies as a function of the neurons’ responsiveness and selectivity for the stimuli, as well as RS and FS neuron type, and that this effect is present even when stimuli are not incorporated into a behavioral task. As previous studies have shown (Constantinidis & Goldman-Rakic, 2002), a substantial part of the estimated correlation of neuronal populations is due to interactions between pyramidal neurons and interneurons. Since only pyramidal neurons project beyond a cortical area, population averages may overestimate the influence of correlated noise between processing steps. Correlation between RS-FS neurons was also most greatly affected by training, suggesting a possible reorganization of local prefrontal inhibitory circuitry after learning.

Training to perform the task affected differentially neuron pairs based on their type and stimulus responsiveness and selectivity. Previous studies have shown that noise correlation (in trained animals) is influenced by the similarity of neuronal responses, measured by signal correlation, and the temporal envelope of neuronal activation, which we refer to as temporal correlation (Lee et al., 1998; Constantinidis et al., 2001). Our current results demonstrate that this relationship too, is not the consequence of task execution but rather is present prior to training in the task itself.

A big decrease in noise correlation was observed during the stimulus presentation, which the monkey is presumably attending after training in order to perform the cognitive task. A somewhat similar effect has recently been shown in the extrastriate cortex; decreased noise correlation was observed for an attended compared to an unattended stimulus (Cohen & Maunsell, 2009; 2011). However the decrease in correlation we observed was not specifically directed to a stimulus (whose location could not be predicted in our task). Instead, there was an overall decrease in correlation across neurons, even those who were not selective for the stimuli. Computational studies have shown that the degree of correlation between the discharges of two neurons can be reduced dynamically (Renart et al., 2010), and it appears that this process is taking place during the execution of the working memory task. Interestingly, we observed increases in noise correlation among populations of neurons that were not responsive to the stimuli or the task. Increases in noise correlation have been previously described in the context of a feature attention task; when attention in area V4 is directed towards stimuli in a visual display that are non-preferred for the neurons studied (causing decrease in firing rate as result of attention), noise correlation increases (Cohen & Maunsell, 2011). We additionally observed an increase in noise correlation for neurons not responsive to the stimuli used in our experiment. An increase in noise correlation can represent an improvement in information encoding, if it is considered that a comparison of different populations of neurons achieved through subtracting signals of different selectivity will decrease the overall correlated noise in the population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 EY017077. We wish to thank Travis Meyer for his contribution to experiments that generated data analyzed here, and Albert Compte and Ram Ramachandran for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- Abbott LF, Dayan P. The effect of correlated variability on the accuracy of a population code. Neural Comput. 1999;11:91–101. doi: 10.1162/089976699300016827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Latham PE, Pouget A. Neural correlations, population coding and computation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrn1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck BB, Lee D. Neural noise and movement-related codes in the macaque supplementary motor area. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7630–7641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07630.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair W, Zohary D, Newsome WT. Correlated firing in macaque visual area MT: time scales and relationship to behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1676–1697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01676.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody CD. Slow covariations in neuronal resting potentials can lead to artefactually fast cross-correlations in their spike trains. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:3345–3351. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Kohn A. Measuring and interpreting neuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:811–819. doi: 10.1038/nn.2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Attention improves performance primarily by reducing interneuronal correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1594–1600. doi: 10.1038/nn.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Maunsell JH. Using neuronal populations to study the mechanisms underlying spatial and feature attention. Neuron. 2011;70:1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Newsome WT. Context-dependent changes in functional circuitry in visual area MT. Neuron. 2008;60:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Newsome WT. Estimates of the contribution of single neurons to perception depend on timescale and noise correlation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6635–6648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5179-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinidis C, Franowicz MN, Goldman-Rakic PS. Coding specificity in cortical microcircuits: a multiple electrode analysis of primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3646–3655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03646.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinidis C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Correlated discharges among putative pyramidal neurons and interneurons in the primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3487–3497. doi: 10.1152/jn.00188.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinidis C, Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. A role for inhibition in shaping the temporal flow of information in prefrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci. 2002;5:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nn799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rocha J, Doiron B, Shea-Brown E, Josic K, Reyes A. Correlation between neural spike trains increases with firing rate. Nature. 2007;448:802–806. doi: 10.1038/nature06028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker AS, Berens P, Keliris GA, Bethge M, Logothetis NK, Tolias AS. Decorrelated neuronal firing in cortical microcircuits. Science. 2010;327:584–587. doi: 10.1126/science.1179867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker AS, Berens P, Tolias AS, Bethge M. The effect of noise correlations in populations of diversely tuned neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14272–14283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2539-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal AA, Selen LP, Wolpert DM. Noise in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:292–303. doi: 10.1038/nrn2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawne TJ, Richmond BJ. How independent are the messages carried by adjacent inferior temporal cortical neurons? J Neurosci. 1993;13:2758–2771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02758.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Liu S, Fetsch CR, Yang Y, Fok S, Sunkara A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Perceptual learning reduces interneuronal correlations in macaque visual cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Henze DA, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Buzsaki G. Accuracy of tetrode spike separation as determined by simultaneous intracellular and extracellular measurements. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:401–414. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KO. Sensory discrimination: neural processes preceding discrimination decision. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1793–1815. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.6.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Smith MA. Stimulus dependence of neuronal correlation in primary visual cortex of the macaque. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3661–3673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5106-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Zandvakili A, Smith MA. Correlations and brain states: from electrophysiology to functional imaging. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law CT, Gold JI. Neural correlates of perceptual learning in a sensory-motor, but not a sensory, cortical area. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:505–513. doi: 10.1038/nn2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Port NL, Kruse W, Georgopoulos AP. Variability and correlated noise in the discharge of neurons in motor and parietal areas of the primate cortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1161–1170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01161.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard EM, Hatsopoulos NG, Ojakangas CL, Acuna BD, Sanes JN, Normann RA, Donoghue JP. Neuronal interactions improve cortical population coding of movement direction. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8083–8093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08083.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T, Constantinidis C. A software solution for the control of visual behavioral experimentation. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;142:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T, Qi XL, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Stimulus selectivity in dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortex after training in working memory tasks. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6266–6276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6798-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JF, Sundberg KA, Reynolds JH. Differential attention-dependent response modulation across cell classes in macaque visual area V4. Neuron. 2007;55:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk A, Litwin-Kumar A, Doiron B. Correlated neural variability in persistent state networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121274109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poort J, Roelfsema PR. Noise correlations have little influence on the coding of selective attention in area V1. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:543–553. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi XL, Constantinidis C. Variability of prefrontal neuronal discharges before and after training in a working memory task. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041053. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi XL, Meyer T, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Changes in Prefrontal Neuronal Activity after Learning to Perform a Spatial Working Memory Task. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2722–2732. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi XL, Meyer T, Stanford TR, Constantinidis C. Neural correlates of a decision variable before learning to perform a Match/Nonmatch task. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6161–6169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6365-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DS, Mechler F, Victor JD. Independent and redundant information in nearby cortical neurons. Science. 2001;294:2566–2568. doi: 10.1126/science.1065839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renart A, de la Rocha J, Bartho P, Hollender L, Parga N, Reyes A, Harris KD. The asynchronous state in cortical circuits. Science. 2010;327:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1179850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo R, Hernandez A, Zainos A, Salinas E. Correlated neuronal discharges that increase coding efficiency during perceptual discrimination. Neuron. 2003;38:649–657. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samonds JM, Potetz BR, Lee TS. Cooperative and competitive interactions facilitate stereo computations in macaque primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15780–15795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2305-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. The variable discharge of cortical neurons: implications for connectivity, computation, and information coding. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3870–3896. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03870.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Kohn A. Spatial and temporal scales of neuronal correlation in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12591–12603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2929-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneswaran G, Kraskov A, Lemon RN. Large identified pyramidal cells in macaque motor and premotor cortex exhibit “thin spikes”: implications for cell type classification. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14235–14242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3142-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohary E, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Correlated neuronal discharge rate and its implications for psychophysical performance. Nature. 1994;370:140–143. doi: 10.1038/370140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]