Abstract

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a cutaneous infection most commonly associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. EG generally occurs in immunocompromised hosts, such as patients with severe neutropenia. EG presents as erythematous, hemorrhagic, or necrotic macules or plaques most commonly in the perineal or gluteal areas, but can occur elsewhere. EG is a dermatologic emergency in immunocompromised patients and should be included in the differential diagnosis when urologists are asked to evaluate perineal lesions. We describe the case of a highly immunocompromised infant with labial EG to highlight the importance of prompt clinical diagnosis and of multi-disciplinary medical and surgical management.

Keywords: ecthyma gangrenosum, immunocompromised, Pseudomonas

CASE REPORT

An 11 month-old girl with high-risk infant B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in the consolidation phase of chemotherapy was admitted to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia with fever and chemotherapy-associated neutropenia. She had been severely neutropenic (absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <200 cells/uL) for at least seven days prior to admission. Her parents had also noted mild right labial erythema, swelling, and discomfort with diaper changes for three days prior to admission. At time of admission, she had received seven days of daily granulocyte colony stimulating factor (g-csf; filgrastim) injections post-chemotherapy per her ALL treatment protocol, but had not yet demonstrated evidence of white blood cell (WBC) or ANC recovery. In the Emergency Department, the patient had a temperature of 38.4 °C and a normal blood pressure for age. Complete blood count testing revealed a WBC count of 0.4 cells/uL with an ANC of 20 cells/uL, as well as chemotherapy-induced anemia and thrombocytopenia. Blood cultures were obtained, and cefepime and gentamicin were administered as empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage in the setting of severe febrile neutropenia. Following initial examination the subsequent morning by the inpatient Pediatric Oncology physician, clindamycin was added for additional skin flora coverage given the patient’s right labial edema and erythema. No abscess or other lesion was detected at that time. Daily g-csf was continued per her chemotherapeutic protocol. On the second day of hospitalization, a well-circumscribed round blue-grey 8 mm macule was noted on the patient’s inner right labia majora with area of surrounding erythema (Figure 1). Pediatric Dermatology, Pediatric Infectious Diseases, and Pediatric Urology were immediately consulted due to concerns for possible invasive fungal infection versus EG. The lesion was thought to be most consistent with Pseudomonas -associated EG given the central necrosis and perineal location; however, a fungal infection was also possible given the patient’s immunocompromised status. Due to the patient’s age, obtaining an adequate diagnostic labial tissue sample via punch biopsy at the bedside was not possible, so she was taken to the operating room by Pediatric Urology for excisional biopsy. Surgical examination and excision revealed a violaceous lesion measuring 8 mm in diameter and 1 cm in depth that was completely removed. The surrounding tissue was firm and indurated, but non-purulent. The lack of pus was not unexpected given the patient’s severe neutropenia. Samples were sent for Gram staining, potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing for fungus, bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures, and antibiotic sensitivity testing (Figure 2). A vessel loop was placed in the wound to facilitate post-operative drainage. Gram staining was positive for sheets of Gram-negative rods, and the wound culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa within 24 hours. Initial blood cultures obtained in the ED and subsequent daily blood cultures obtained on post-operative days zero, one, and two remained without bacterial growth. Post-operatively, her antibiotics were changed to imipenem and gentamicin for anti-Pseudomonas dual coverage for seven days, followed by an additional seven days of imipenem monotherapy. She had no additional fever following her initial presentation in the ED, and her subsequent hospitalization was otherwise unremarkable. WBC and ANC recovery occurred on post-operative day 4, and the g-csf was discontinued per chemotherapeutic protocol. She was discharged on post-operative day seven in stable health with her surgical wound well-healed and without obvious signs of persistent infection (Figure 3). She has subsequently continued her scheduled anti-ALL chemotherapy without delay.

Figure 1.

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) with central eschar and surrounding erythema and edema of labia majora.

Figure 2.

Intra-operative photo after excisional biopsy of labial lesion

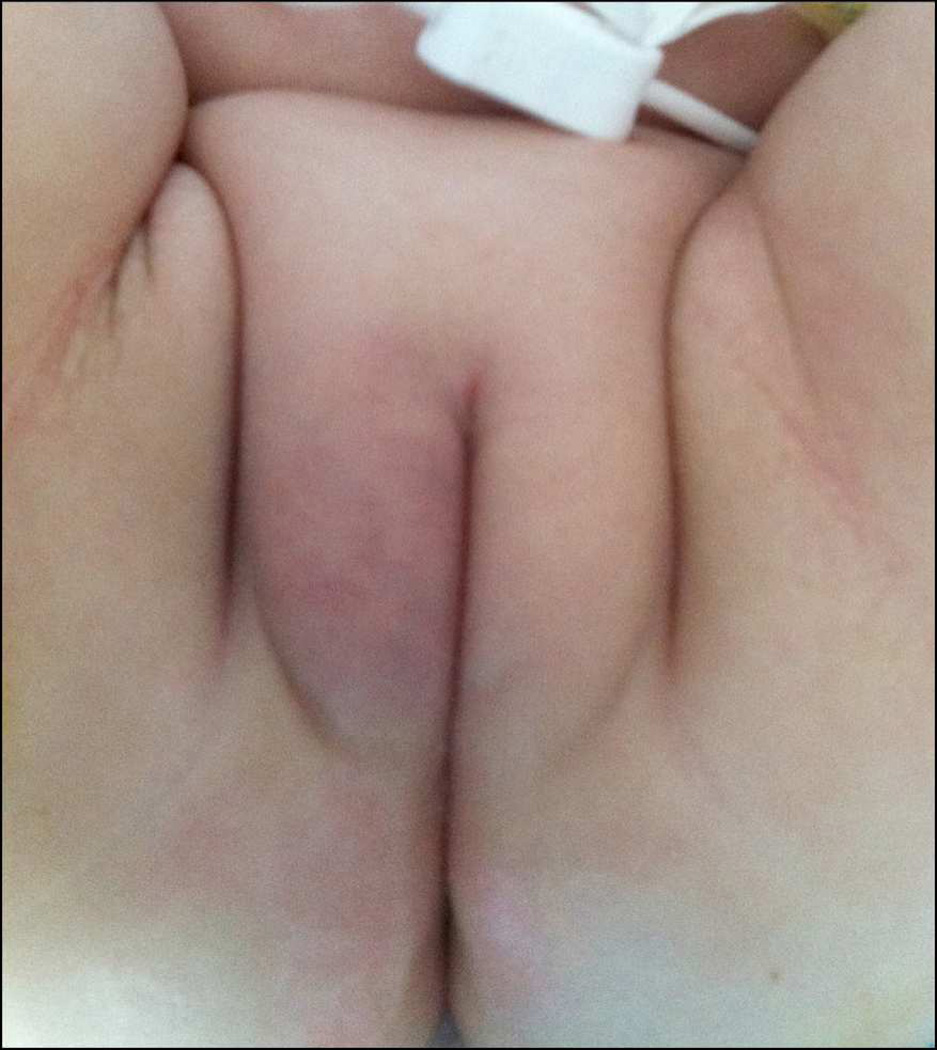

Figure 3.

The patient’s labiae majorae on post-operative day 7 at time of hospital discharge, demonstrating wound healing and no recurrence of infection.

COMMENT

EG is a rare cutaneous lesion classically associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis that occurs most frequently in severely immunocompromised patients.(1–3) It is characterized by erythematous, hemorrhagic, or necrotic macules or plaques most commonly of the perineal or gluteal skin that can rapidly progress into a gangrenous ulcer or eschar.(1) While most commonly caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa EG has also been associated with other bacterial etiologies, including Aeromonas hydrophila Staphylococcus aureus Serratia marcescens Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia and Citrobacter freundii.(3–6) In addition, fungal pathogens have been described in EG, including Aspergillus fumigatus Mucor species, Candida albicans Fusarium solani and Scytalidium dimidiatum.(4, 7) EG can manifest as either solitary or multiple lesions; presentation with a solitary lesion generally results in better prognoses.(6) EG was initially hypothesized to occur via hematogenous spread and vascular seeding of the skin, but more recent studies demonstrate that EG can occur through direct inoculation of the skin without concomitant bacteremia.(8) Patients with EG and associated bacteremia have significantly higher rates of mortality (>23%) than those without bacteremia (<10%).(8, 9) Our patient is classified in the latter category and, fortunately, suffered few adverse consequences given the prompt recognition of probable EG and definitive multi-disciplinary management.

Empiric treatment of suspected EG in immunocompromised patients should include broad-spectrum antibiotics with initial double coverage against Pseudomonas aeruginosa which can be subsequently narrowed based upon bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. Complete surgical excision is not required for diagnosis or treatment of EG. Excision was performed in this case because fungus, which does require complete surgical excision, was on the differential diagnosis. Although mortality is higher if blood cultures are positive for pseudomonas, pseudomonal septicemia does not change management for a patient with EG. All patients require a 14-day course of sensitivity-specific antibiotics.

As with other severe infections in highly immunosuppressed patients, use of gcsf and/or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor may be considered to decrease the duration of neutropenia.(10) Superinfection of these lesions with Staphylococcus or Candida species may also ensue, so frequent reassessment is warranted. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of EG is often not made promptly and has been associated with significantly increased risk of death, possibly due to inadequate and delayed administration of appropriate antibiotics.(2) It is thus critical that urologists consider this diagnosis and are able to identify potential EG when consulted for evaluation and management of perineal lesions, particularly those occurring in immunocompromised patients, as prompt recognition of this dermatologic emergency may be life-saving.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No authors have any financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Gregory Tasian is supported by NIH-5T32HD060550-03. Dr. Sarah Tasian is supported by NIH-K12CA076931.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boisseau AM, Sarlangue J, Perel Y, et al. Perineal ecthyma gangrenosum in infancy and early childhood: septicemic and nonsepticemic forms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(3):415–418. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greene SL, Su WP, Muller SA. Ecthyma gangrenosum: report of clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic aspects of eight cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(5 Pt 1):781–777. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;50(5 Suppl):S114–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.File TM, Jr, Marina OA, Flowers FP. Necrotic skin lesions associated with disseminated candidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115(2):214–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musher DM. Cutaneous and soft-tissue manifestations of sepsis due to gram-negative enteric bacilli. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2(6):854–866. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.6.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis YF, Richman S, Hussain S, et al. Aeromonas hydrophila infection: ecthyma gangrenosum with aplastic anemia. N Y State J Med. 1982;82(10):1461–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal S, Sharma M, Mehndirata V. Solitary ecthyma gangrenosum (EG)-like lesion consequent to Candida albicans in a neonate. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74(6):582–584. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.el Baze P, Thyss A, Vinti H, et al. A study of nineteen immunocompromised patients with extensive skin lesions caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa with and without bacteremia. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71(5):411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YC, Lin TY, Wang CH. Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in previously healthy infants and children: analysis of forty-three episodes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21(11):1049–1052. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregorini M, Castello M, Rampino T, et al. GM-CSF contributes to prompt healing of ecthyma gangrenosum lesions in kidney transplant recipient. J Nephrol. 2012;25(1):137–139. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]