Abstract

Objective

College counseling centers (CCCs) are increasingly being called upon to treat highly distressed students with complex clinical presentations. This study compared the effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for suicidal college students to an optimized control condition, and analyzed baseline global functioning as a moderator.

Method

The intent-to-treat (ITT) sample included 63 college students between the ages of 18 and 25 who were suicidal at baseline, reported at least one lifetime non-suicidal self-injurious (NSSI) act or suicide attempt, and met three or more borderline personality disorder (BPD) diagnostic criteria. Participants were randomly assigned to DBT (n = 31) or an optimized Treatment as Usual (O-TAU) control condition (n = 32). Treatment was provided by trainees, supervised by experts in both treatments. Both treatments lasted 7–12 months and included both individual and group components. Assessments were conducted at pretreatment, 3-months, 6-months, 9-months, 12-months, and 18-months (follow-up).

Results

Mixed effects analyses (ITT sample) revealed that DBT, compared to the control condition, showed significantly greater decreases in suicidality, depression, number of NSSI events (if participant had self-injured), BPD criteria, and psychotropic medication use, and significantly greater improvements in social adjustment. Most of these treatment effects were observed at follow-up. No treatment differences were found for treatment dropout. Moderation analyses showed that DBT was particularly effective for suicidal students who were lower functioning at pretreatment.

Conclusions

DBT is an effective treatment for suicidal, multi-problem college students. Future research should examine the implementation of DBT in CCCs in a stepped care approach.

Although the college years are often thought of as carefree for young adults, nearly half of this population can be diagnosed with at least one mental health disorder in a given year (Blanco et al., 2008). Depression, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), and borderline personality disorder (BPD) features are significant mental health problems among college students. Approximately one third of college students report experiencing depression that affected their ability to function in the past year (American College Health Association (ACHA), 2011). Suicide, a common concomitant of depression, is a leading cause of death among college students (Suicide Prevention Resource Center, 2004). Nearly 20% of college students report seriously considering and over 7% attempting suicide in their lifetime, whereas 6.4% of students report contemplating and 1% attempting suicide in the past year alone (ACHA, 2011). Between 40% and 50% of severely suicidal students report multiple episodes of suicidal ideation (Drum, Brownson, Denmark, & Smith, 2009). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which refers to skin cutting or other forms of intentional self-injury without conscious suicidal intent, has been found to have a 15.3% lifetime and 6.8% past year prevalence rate among college students, with 43% of the self-injurious students indicating six or more NSSI episodes (Whitlock et al., in press). Additionally, approximately 15% of introductory psychology students screen positive for significant BPD features on a personality questionnaire (Trull, 1995), and 4% are deemed to have a probable or definite BPD diagnosis in the general campus population (Taylor, 2005).

Effective treatment of these problems among college students may deflect the trajectory of these severe mental health problems before they become chronic (Zivin, Eisenberg, Gollust, & Golberstein, 2009). College Counseling Centers (CCCs) are the front line for providing mental health services for college students and are increasingly involved in the treatment of severe psychopathology, such as depression, suicidal ideation, and BPD (Benton, Robertson, Tseng, Newton, & Benton, 2003; Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH), 2012), despite limited resources (Gallagher, 2011). The implementation of empirically supported treatments for severe and/or complex mental health problems in CCCs could have significant and long-term public health impact; however, there is a critical lack of studies on the effectiveness of such treatments in these settings (Cooper, 2005; Kitzrow, 2003).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993a,b) is an empirically supported treatment for individuals presenting with complex and severe mental health problems, including BPD, depression, suicidal ideation, and NSSI. DBT produces long term gains for suicidal BPD patients across a variety of domains including BPD symptoms, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, NSSI, and psychiatric hospitalization, and enhances social functioning and global improvements (see Kliem, Kroger, & Kosfelder, 2010 for a recent meta-analysis). Although several DBT studies have focused on middle-aged women meeting full criteria for BPD (e.g., Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991), there is evidence that DBT is feasible and effective with male and female adolescents (Groves, Backer, van den Bosch, & Miller, in press), as well as with other populations (Feigenbaum, 2007).

There are several reasons to investigate the implementation of DBT in the treatment of college students with complex clinical presentations, including suicidal ideation, severe depression, NSSI, and BPD features. First, DBT is a principle-based treatment that is flexible enough to apply to the severe and multi-problem presentations increasingly seen across campuses (Benton et al., 2003). Second, DBT focuses on teaching skills (e.g., emotion regulation, distress tolerance) that are developmentally relevant to college students (Kadison & DiGeronimo, 2004). Third, DBT was designed for chronically suicidal individuals and some experts suggest that chronically suicidal students are more likely to benefit from comprehensive treatment approaches and may actually experience iatrogenic effects with very brief forms of treatment (Jobes, Jacoby, Cimbolic, & Husted, 1997). Fourth, the presentation of college students with BPD traits differs from community BPD samples, and the treatment targets of DBT can be altered to address college students’ specific clinical needs. For example, college students are less likely than community BPD samples to engage in recurrent suicidal threats (Trull, 1995), thus suggesting that DBT treatment for this population may focus more on skills acquisition than stabilization per se. Despite the logic behind its application, there are no treatment outcome studies examining the impact of DBT among college students.

Integrating DBT into CCCs needs to take into account that CCCs are often designed to deliver short-term psychotherapy (CCMH, 2012), frequently rely on trainees as therapists (Minami et al., 2009), and are subject to relatively inflexible breaks and vacations which can interfere with manualized treatment approaches. Thus, research is needed to evaluate whether DBT applied to the treatment of severely distressed college students within a CCC context is effective. Additionally, this research must examine whether treatment outcomes are moderated by individual factors, such as students’ presenting level of global functioning, in order to guide CCCs in terms of who might best benefit from more intensive approaches. To this end, the present study had two aims. The first aim was to compare DBT to an optimized treatment as usual (O-TAU) condition in the treatment of college students meeting three or more BPD diagnostic criteria, and reporting current suicidal ideation and a lifetime history of at least one NSSI and/or one suicide attempt at baseline. The second aim was to analyze students’ baseline level of global functioning as a moderator of treatment effects.

Method

Participants

Participants were 63 college students seeking services at the CCC at a medium sized public university in the Western United States. Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the sample. Participants included in the study were between the ages of 18 and 25, reported suicidal ideation at baseline as evidenced by a score of 1 or higher on Question 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), endorsed at least one act of lifetime NSSI and/or suicide attempt as measured by the Suicide Attempt-Self Injury Interview (SASII; Linehan, Comtois, Brown, Heard, & Wagner, 2006), and met three or more criteria on the BPD section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II, BPD; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams,1997). Participants were excluded based on psychosis, need for inpatient care (as judged by assessor), or prior DBT treatment, and had to refrain from taking part in other psychotherapy during the treatment portion of the study. The local Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Pretreatment

| Variable | Total | DBT | O-TAU | χ2, T-Test, or Fisher’s Exact | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 20.86 (1.92) | 20.42 (1.56) | 21.28 (2.14) | 1.82 | .07 |

| Female (%) | 81.0 | 77.4 | 84.4 | 0.14 | .70 |

| Living in a dorm (%) | 17.5 | 9.7 | 25.0 | 2.57 | .11 |

| Full-Time Student (%) | 74.6 | 74.1 | 75.0 | 0.05 | .94 |

| Born in the U.S. (%) | 84.1 | 87.1 | 81.2 | F.E. | .73 |

| Gay/Lesbian/B/T (%) | 31.7 | 32.3 | 31.2 | 0.008 | .93 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| African American | 3.2 | 6.5 | 0.0 | F.E. | .24 |

| Asian/Asian Amer | 6.3 | 3.2 | 9.4 | F.E. | .61 |

| Hispanic | 11.1 | 3.2 | 18.8 | F.E. | .11 |

| Native American | 4.8 | 9.7 | 0.0 | F.E. | .11 |

| Other | 4.8 | 3.2 | 6.3 | F.E. | 1.00 |

| White | 69.8 | 74.2 | 65.6 | 0.55 | .49 |

| Year in School (%) | |||||

| Freshman | 31.7 | 35.5 | 28.1 | 0.39 | .53 |

| Sophomore | 22.2 | 16.1 | 28.1 | 1.31 | .25 |

| Junior | 15.9 | 19.4 | 12.5 | F.E. | .51 |

| Senior | 25.4 | 25.8 | 25.0 | 0.01 | .94 |

| Graduate Student | 4.8 | 3.2 | 6.2 | F.E. | 1.00 |

| Current Disorder (%) | |||||

| Any Major Depressive Disorder | 81.0 | 87.0 | 75.0 | −1.22 | .22 |

| Any Substance Use Disorder | 36.5 | 38.7 | 34.4 | −0.35 | .72 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 79.4 | 71.0 | 87.5 | 1.62 | .11 |

| Any Eating Disorder | 15.9 | 22.6 | 9.4 | −1.42 | .16 |

Note. F. E. stands for Fisher Exact test.

Randomization and Power

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment conditions using a computerized urn randomization procedure (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994), controlling for gender, presence of NSSI or a suicide attempt within the last eight weeks, and psychotropic medication use at baseline. Prior to conducting the study, a power analysis based on preliminary findings from an ongoing DBT study relying on a similar design (Linehan, Comtois, Murray et al., 2006) and a DBT study with a younger sample (Turner, 2000) showed that 31 participants per condition using an intent-to-treat (ITT) design provided 80% power for d = 0.8 with 15% attrition for primary outcomes (e.g., suicide attempts and NSSI). These assumptions were based on existing DBT studies that had obtained large effect sizes for suicidal behaviors and very low attrition rates (e.g., Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991; Turner, 2000), and our original assumption of lower attrition among college students.

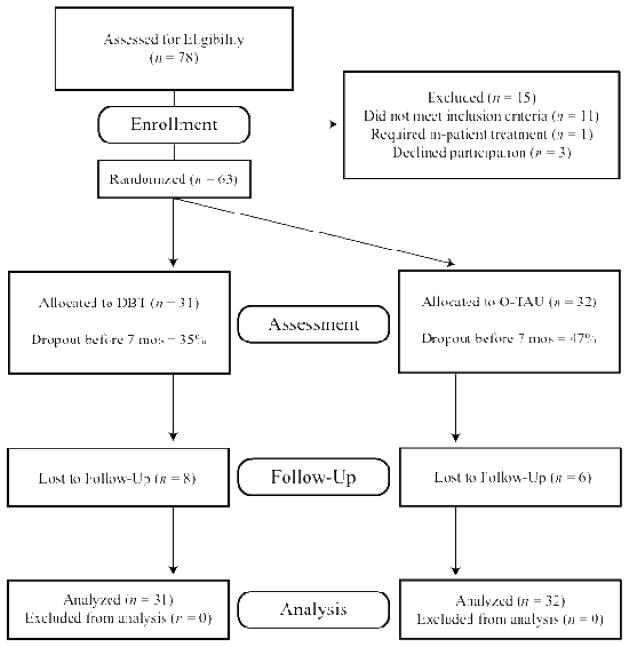

Figure 1 depicts the participant flow through the study. Following randomization to the two conditions, participants completed assessments every three months during the treatment period (upper limit of 12 months) and once again at follow-up (18 months after the pretreatment assessment). Every effort was made to recruit participants for assessments, including dropouts, and financial incentives were offered for the 12- ($25) and 18-month ($75) assessments.

Figure 1.

JARS Participant Flow Chart

Axis-I Diagnostic Interview

Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV

Nonpatient Version (psychotic screen, and Mood, Anxiety, Substance Use, and Eating Disorders modules), (SCID–I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) was used to gauge exclusion criteria and describe the sample. This is a widely used instrument with acceptable interrater reliability (First et al., 2002). Assessors were trained until they reached 95% agreement on diagnostic categories.

Treatment Credibility Questionnaire

At the end of session 1, participants rated the therapy they were receiving on seven items adapted from Borkovec and Nau (1972) that asked how logical, scientific, or potentially helpful the treatment appeared to be. The coefficient alpha was .88 for this study.

Outcome Measures: Interviews

Interviewers

Potential participants were interviewed by independent assessors who were blind to treatment condition and held masters or doctoral degrees in clinical psychology. Assessors were trained by experts on the measures administered. A random sample of 25% of the dependent variables’ videotapes were evaluated by an additional rater to calculate interrater reliability (kappa for categorical measures, intraclass correlations (ICC) for ordinal ratings).

SCID-II, BPD

The SCID-II, BPD (First et al., 1997) served as a screening and secondary outcome measure. It has good psychometric properties and adequate convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity (Ryder, Costa, & Babgby, 2007). This measure was administered three times: baseline, at 12-months, and at 18-months (follow-up), with the timeframe being “last year” for the 12-month assessment and “last six months” for the follow-up assessment. Interrater reliabity was good in this study, with ICCs ranging from .85 to .93.

Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII; Linehan, Comtois, Brown et al., 2006)1

The SASII is a clinician-administered assessment of the frequency and topography of suicide attempts and NSSI. ICCs for the subscales ranged from .87 to .94 for this study. However, only the occurrence (yes/no) and frequency of NSSI were analyzed in the present study because the base rate for NSSI and suicide attempts was too low post-baseline, and the subscales can only be computed when NSSI or suicide attempts are present.

Outcome Measures: Self-Report Questionnaires

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996)

The BDI-II is a well-known measure of depressive symptom severity and has good psychometric properties with this population (e.g., Steer & Clark, 1997). The coefficient alpha was .86 for this study.

Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire (SBQ; Linehan, 1981)

The SBQ includes a scale measuring suicidality (SBQ-23), as well as a table for self-report of NSSI and suicide attempts. On the SBQ table, participants are asked to report the number of self-harming acts across various categories (e.g., cutting, overdosing) and their level of suicidal intent for each incident (e.g., clear intent to die, ambivalent, no intent to die). Events were classified as suicide attempts when the participant indicated ambivalent or clear intent to die and as an NSSI when there was no intent to die. The SBQ-23 total score ranges from 0 to 88, assessing the frequency of suicidal thoughts, and the person’s estimation of the likelihood they would consider, attempt, and die from suicide in the future, across various timeframes (e.g., next month, next 4 months, next year, lifetime). The SBQ-23 has been used in other DBT studies (e.g., Linehan, Comtois, Murray, et al., 2006) and its coefficient alpha was .92 for this study.

Social Adjustment Scale-Self-Report (SAS-SR; Weissman & Bothwell, 1976)

The SAS-SR is a 54-item assessment of functioning across a number of domains, which combine to yield a total score. In this study, the total score yielded a coefficient alpha of .81.

Moderator: Independent Assessors’ Rating

Global assessment of functioning (GAF; Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, & Cohen, 1976)

The GAF is a clinician-rated measure of global functioning evaluated by assessors who were blind to condition. Baseline GAF scores, based on a median split, were used to test for moderation.

Overview of Treatments and Design

Participants were randomly assigned to either DBT or an optimized treatment as usual (O-TAU) condition, relying on supervision by an expert. Treatment and data collection occurred between January 2006 and January 2009.

DBT

The DBT treatment provided as part of this study followed closely the standard outpatient DBT package (Linehan, 1993a,b): 1) weekly 50-minute individual psychotherapy (while student was in town); 2) weekly 90-minute group skills training; 3) skills coaching as needed (via telephone, email, or texting) between sessions to help patients generalize skills as solutions to their difficulties (Linehan, 1993a); 4) weekly 90-minute group supervision/consultation for therapists; and 5) as-needed family interventions (Fruzzetti, Santisteban, & Hoffman, 2007).

There were four modifications to standard DBT (Linehan 1993a,b) in this study. First, we shortened the distress tolerance module to three weeks and combined it with a three-week long validation module utilized in recent DBT studies (e.g., Iverson, Shenk, & Fruzzetti, 2009). Based on satisfaction ratings and exit interviews from pilot work, college students who participated in DBT group skills reported finding parts of the distress tolerance module less helpful to them—possibly because college itself requires a modicum of distress tolerance skills and the traditional distress tolerance module was designed for a severe community sample. Similarly, a validation module was rated as being very helpful, perhaps due to the salience of interpersonal connections for college students, particularly those seeking treatment (CCMH, 2012). This validation module included skills in recognizing different validation levels, validating one’s own reactions, and validating others. Each skill area (emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and distress tolerance/validation) lasted six weeks and was immediately preceded by two weeks of mindfulness training, for a total of three modules, each lasting eight weeks.

Second, as is typical of DBT, therapists relentlessly encouraged attendance and followed up on missed sessions through phone calls and emails, but because students generally left town for extended periods of time, participants had to miss four scheduled consecutive individual appointments without contact with the therapist to be considered a dropout. This may differ from typical community DBT in that clients, even if away for 2–3 months during scheduled university breaks, could still be considered to be in ongoing treatment. Although the “4-miss rule” is usually considered in the context of weekly contact, particularly until client is stabilized, the DBT 4-miss rule is in fact one way to instantiate key DBT principles and targets, to maximize participation in treatment, including, a) avoiding polarizing around missed sessions (balancing the importance of attending with the realities of some missed appointments) and b) taking the therapist out of the role of judge of what might be a “legitimate” vs. “illegitimate” miss (instead, in DBT, when the client misses, we view it as he or she is simply not present and does not benefit, regardless of the reasons for missing; Linehan, 1993a). In this study, finding a way to keep clients connected to treatment while recognizing realistic constraints on physical attendance during university breaks was the dialectical tension. We tried to resolve the tension not only by not implementing a 4-miss rule, but also by using non-traditional means to stay connected with clients. Depending on participant severity, access, and motivation, long-distance sessions via phone or Skype, and email correspondence, were sometimes used during academic breaks.

Third, skills groups ran for 1.5 hours to accommodate class schedules. Fourth, the three eight-week skills modules followed the campus schedule with one module taught in the Spring, one in the Fall, and one in the Summer (modules taught at each time varied depending on the needs of enrolled clients). Optimal treatment in terms of skills trainings involved attending eight group sessions per semester. Thus, only students completing 12 months of treatment received all three skills training modules and some DBT completers were only exposed to 1–2 skills group modules (e.g., may have been gone in the summer or finished treatment early), although skills training was also provided individually on occasion. Students in this sample were only exposed to skills modules once whereas in traditional outpatient DBT that lasts 12 months clients participate in each skills module at least twice (Linehan, 1993b).

We considered a treatment completer someone who stayed in treatment between 7 and 12 months, regardless of number of sessions attended. Although participants were offered up to 12 months of treatment, they were asked to make a commitment to stay in treatment at least 7 months. The 7-month criterion was selected to define completers because in pilot work many students experienced significant improvement in one semester of treatment and did not warrant continued intervention. The 7-month cut-off (instead of only one semester) required students to attend treatment across semesters, thus allowing counselors to ensure the student’s therapeutic progress was stable. A shorter length of treatment has been applied successfully in other DBT studies (e.g., Koons et al., 2001).

Optimized Treatment as Usual (O-TAU)

Linehan, Comtois, Murray et al. (2006) compared DBT to therapy by experts to ensure high allegiance and expert treatment in the control condition. The present design emulated that approach, but because treatment in CCCs is often provided by trainees (Minami et al., 2009), we opted for a supervision by an expert paradigm. DBT supervision was conducted by the first two authors, while a control supervisor was selected who had been named by members of both the Nevada State Board of Psychological Examiners and the Nevada State Psychological Association as an expert in treating BPD and suicidality using a non-cognitive-behavioral approach. The O-TAU supervisor is the author of a psychodynamically oriented book titled Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (Chatham, 1985) that integrates developmental perspectives with object relations theory.

The use of the supervision by experts design controls for the supervisors’ allegiance and general expertise with this population, but does not lend itself to a rigorous comparison of treatments (Linehan, Comtois, Murray et al., 2006). The present comparison reflects a well-trained and supervised (“optimized”) treatment based on a coherent model – a realistic treatment-as-usual condition. As such, it is not technically a comparison of two specific treatments, but one specific one (DBT) and one more general (O-TAU). Thus, the O-TAU condition was not monitored or coded for adherence. To attempt to more closely equate treatment dose (contact time with treatment providers), O-TAU included: 1) once-weekly 50-minute individual therapy (when student was in town); 2) once-weekly 90-minute group therapy (approximately eight weeks per semester); 3) once-weekly 90-minute group supervision for therapists; 4) as needed between-session consultation; and 5) as needed family interventions.

Trainee therapists and their training

Supervisors hired the therapists in their respective conditions based on experience and allegiance to the particular therapeutic orientation. Five DBT and four O-TAU therapists were recruited for the study. Four of the five DBT therapists and three of the four O-TAU therapists were female. All DBT therapists were graduate students in a clinical psychology program. One of the O-TAU psychotherapists was a psychiatry resident, one was a psychology postdoctoral fellow, one was a graduate student in clinical psychology, and one was a Masters-level counseling psychology graduate student.

Trainees in both conditions underwent 30 hours of training in their approach, separately (DBT or O-TAU), prior to beginning to offer treatment. The DBT training followed Linehan books (1993a, b) and the O-TAU training was based on the text authored by the O-TAU supervisor (Chatham, 1985). Interventions for both conditions took place in the same CCC.

Treatment length and type

As noted above, participants were offered up to a year of treatment, and participants who completed 7–12 months of treatment were considered completers. Although both treatment conditions offered weekly individual and group therapy, in DBT, skills groups are inherently part of the treatment and attendance was emphasized whereas in O-TAU all clients were offered group therapy but its emphasis was left up to the clinical judgment of the therapist/supervisor.

Supervision

Both conditions conducted 90-minute weekly group supervision. On average, each therapist maintained a caseload of three clients and conducted one group. Additional individual supervision or phone consultation was provided as needed. In DBT supervision, a brief update on all clients was provided with more in-depth discussions prioritized based on DBT’s hierarchy (e.g., suicidal and NSSI behaviors first). The structure and process of the group supervision in O-TAU was left up to the supervisor.

Analytic Approach for Treatment Outcome

Primary analyses were based on either mixed model analysis of variance (MMANOVA; Schwarz, 1993) or hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2001), which take into account missing data and the spacing between assessments (Verbeke & Mloenberg, 2000). HLM was used if the change appeared linear; otherwise, an MMANOVA approach was used. Appropriate covariance structures were determined by comparison of the −2 Restricted Likelihood, AIC, and AICC.

Normality of all measures was ensured and transformations applied if needed. Denominator degrees of freedom were estimated with the Kenward-Roger’s (1997) approximation. Effect sizes for the MMANOVA and HLM analyses were based on overall F-test statistics (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991) and slope differences (Raudenbush and Liu, 2001), respectively, and interpreted using the cutoffs suggested by Cohen (1992). Pattern-mixture models were used to assess whether or not important estimates were dependent on missing data patterns (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997) or on total number of hours in treatment. To examine moderation, GAF scores were converted into a dichotomous variable using a median split, and the interaction of the effects of treatment with this dichotomous variable was added to primary outcome analyses. The Jacobson, Follette, and Revenstorf (1984) method was used to analyze reliable change and clinical significance of 12-month and follow-up findings for suicidality and depression, taking into account whether or not there is normative data available (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). All dropouts and other missing data were scored as unimproved and included in the denominator of the calculations, providing a full ITT analysis.

Results

Pretreatment Differences and Characterization of the Sample

Randomization was successful with regard to balancing the three covariate variables: 1) gender (22.6% male in DBT, 15.6% in O-TAU; χ2 = .49, p = .48), 2) currently taking a psychotropic medication (41.9% in DBT, 37.5% in O-TAU; χ2 = .12, p = .72), and 3) presence of NSSI or a suicide attempt in the past two months (64.5% in DBT, 65.6% in O-TAU; χ2 = .01, p = .93). Table 1 shows demographic and diagnostic variables at baseline.

Table 2 shows descriptive data for all dependent variables. At baseline, participants presented with an average score on the BDI-II in the severe range (M = 32.63, SD = 10.27) and approximately two thirds (65%) had engaged in either NSSI or a suicide attempt in the past two months. Pre-treatment differences on parametric measures were compared using t-tests or Chi Square/Fisher’s exact test and revealed no significant differences between conditions on any demographic, diagnostic, or pretreatment dependent variable.

Table 2.

Means (and SDs) or Percent Frequencies for All Dependent Variables Across Assessment Points

| Measures | Condition | Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 9 | Month 12 | Month 18 (Follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidality | O-TAU | 32.88 (18.32) | 27.55 (18.83) | 23.84 (17.74) | 27.42 (22.39) | 24.92 (20.19)* | 23.89 (22.83)* |

| (SBQ-23) | DBT | 31.42 (14.64) | 25.36 (19.18) | 23.36 (18.45) | 17.25 (14.84) | 13.64 (12.20) | 10.67 (10.34) |

| Depression | O-TAU | 30.59 (11.38) | 20.33 (12.31) | 20.68 (15.59) | 21.71 (16.89)* | 16.67 (12.87)** | 15.42 (14.61)** |

| (BDI) | DBT | 34.74 (8.67) | 18.95 (12.44) | 18.90 (9.19) | 13.06 (10.29) | 8.86 (8.52) | 7.61 (7.83) |

| Non-Suicidal Self-Injury | O-TAU | 80.6% | 29.0% | 24.0% | 24.0% | 15.4% | 7.1% |

| (SASII; Any Occurrence) | DBT | 66.7% | 42.3% | 22.7% | 5.3% | 8.3% | 13.0% |

| Non-Suicidal Self-Injury | O-TAU | 76.7% | 35.5% | 32.0% | 25.0% | 12.5% | 19.2% |

| (SBQ; Any Occurrence) | DBT | 60.0% | 52.0% | 18.2% | 12.5% | 13.6% | 17.4% |

| Suicide Attempts | O-TAU | 6.3% | 3.2% | 4.0% | 0% | 0% | 7.1% |

| (SASII; Any Occurrence) | DBT | 19.4% | 11.5% | 4.5% | 0% | 0% | 4.3% |

| Suicide Attempts | O-TAU | 12.5% | 6.5% | 4.0% | 0% | 8.3% | 0% |

| (SBQ; Any Occurrence) | DBT | 22.6% | 8.0% | 4.5% | 0% | 0% | 4.3% |

| BPD Criteria | O-TAU | 4.63 (1.74) | 2.73 (1.93)*** | 2.27 (2.13)** | |||

| (SCID-BPD) | DBT | 5.42 (1.65) | 1.17 (1.40) | 1.27 (1.49) | |||

| Social Adjustment | O-TAU | 2.67 (0.39) | 2.38 (0.66) | 2.25 (0.51) | 2.17 (0.55)** | ||

| (SAS-SR Total Score) | DBT | 2.67 (0.43) | 2.27 (0.47) | 2.02 (0.50) | 1.80 (0.38) | ||

| Psychotropic Medication | O-TAU | 37.5% | 54.8% | 52.0% | 52.0%* | 57.7%* | 53.8%** |

| (Any Usage) | DBT | 41.9% | 38.5% | 27.3% | 15.8% | 20.8% | 8.7% |

Note. Between condition significance at each time point relied on one-way ANCOVA:

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Treatment Credibility, Dropout, and Dosage

There were no differences on treatment credibility (DBT: M = 5.19, SD = .95; O-TAU: M = 5.05, SD = .93; t(47) = −.527, p > .10). There were also no differences on treatment dropout and length in treatment: Approximately 35% of the DBT group (11/31) and 47% of the O-TAU group (15/32) dropped out before completing 7 months of therapy (χ2 = .84, p = .35), 19% of the DBT group (6/31) and 12.5% of the O-TAU group (4/32) completed between 7–11 months of therapy (χ2 = .55, p = .45), and 45% of the DBT group (14/31) and 41% of the O-TAU group (13/32) remained in treatment for the entire 12 months (χ2 = .132, p = .76). There was also no difference in the attendance of individual sessions (DBT: M = 24.97, SD = 12.48; O-TAU: M = 20.70, SD = 11.94; t(60) = −1.29, p > .10); however, given the differences inherent to these therapeutic approaches, DBT participants attended significantly more group sessions (DBT: M = 12.48, SD = 10.0; O-TAU: M = 5.0, SD = 6.3; t(60) = −3.52 (60), p < .01, d = 0.90 (0.37–1.41)). Treatment completers in both conditions attended a significantly higher number of sessions than treatment dropouts, in terms of both individual and group sessions (p < .01). The average DBT completer attended 34.00 (SD = 10.46) individual and 17.00 (SD = 9.38) skills group sessions whereas the average O-TAU completer attended 30.00 (SD = 6.76) individual and 6.70 (SD = 6.78) group sessions. Therefore, the same pattern emerged among completers: there was no difference in number of individual sessions (p > .10) but there was a difference in number of groups attended (p < .01).

Adherence to DBT

An independent DBT adherence rater (trained to reliability) reviewed a random sample of approximately 10% of the DBT therapists’ taped individual sessions (81 of 773), randomly selected across the beginning, middle, and end of treatment, using the DBT Expert Rating Scale (Linehan, Lockard, Wagner, & Tutek, 1996)-- the predecessor to the adherence system being used currently by Linehan and colleagues at the University of Washington. Raters were reliable with Linehan’s raters using this scale. The ordinal scales range from 0.0 (non-adhering) to 5.0 (perfect adherence and competence). Studies vary on cutoff scores used to establish adherence in DBT: in some studies a score of 3.8 or higher has been used to indicate minimal adherence (e.g., Koons et al., 2001), while a score of 4.0 has been used in others (e.g., Linehan, Comtois, Murray et al., 2006). In the present study, the average rating for the Acceptance subscale was 3.87 (range = 3.50–4.43, SD = .23), the Change subscale was 3.92 (range = 3.55–4.40, SD = .22), and the Overall DBT Adherence Score was 3.92 (range = 3.57–4.45). Group sessions were not rated for DBT adherence nor were the O-TAU sessions.

Primary Outcomes

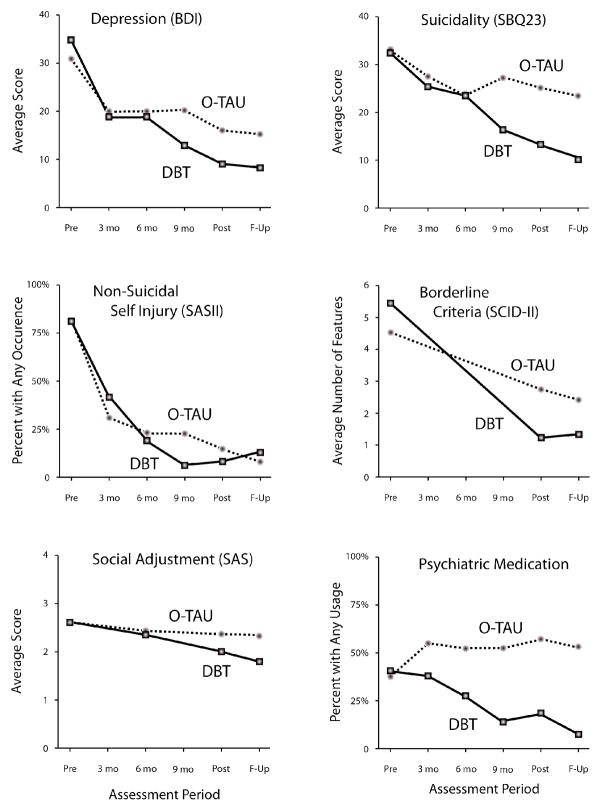

Table 2 provides means and standard deviations for all measures at each assessment point. Three a priori primary outcomes were examined: suicidality, depression, and NSSI. Results are shown graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results for Dependent Variables across Assessment Points in Both Conditions

Suicidality

A HLM analysis revealed that DBT participants showed significantly greater reductions in suicidality as measured by the SBQ-23--frequency of suicidal thoughts, and the person’s estimation of the likelihood they would consider, attempt, and die from suicide in the future--than did O-TAU participants during the treatment period (t(57) = 2.02, p = 0.049, d = 0.53 (0.02–1.03)). Extending time through follow-up showed a similar effect (t(57) = 2.36, p = 0.022, d = 0.63 (0.12–1.13)). Application of the pattern mixture model indicated no significant dependency of the treatment effect on retention (t(59) = 1.39, p = 0.17) and total hours in treatment (t(55) = 1.12, p = 0.26).

Reliable change required difference scores of 12.94 or more on the SBQ-23; 31% of O-TAU participants improved and 16% worsened by the 12-month assessment, 37% improved and 22% worsened at follow up; 32% of DBT participants improved and 0% worsened at 12 months, 48% improved and 0% worsened at follow up. At 12 months, the two conditions did not differ in net gains (subtracting reliable deterioration from improvement) but did so at follow up (χ2 (1) = 7.80, p < .006). This was primarily due to greater deterioration in the O-TAU condition at 12 months and follow up (Fisher’s exact p < .05). Focusing just on those with reliable gains, clinical significance on the SBQ-23, due to the absence of norms, relied on change of one SD or more as the criterion (two SDs yielded a target score below zero). There was no significant difference at 12 months (16% in O-TAU; 29% in DBT) but there was a trend towards a significant difference at follow-up (25% in O-TAU; 45% in DBT; (χ2 (1) = 2.82, p < .094)), suggesting that condition differences may have extended beyond merely greater deterioration in O-TAU.

Depression

A MMANOVA analysis of the BDI-II scores with toeplitz covariance structure revealed a significant effect for time (F (4, 172) = 8.16, p < .0001, d = .78) and for condition (t(54) = 2.78, p < .008, d = .76 (0.24–1.26)). Condition contrasts at fixed time points revealed that the two conditions did not differ significantly (p > .32) until after six months of treatment, when significant differences in favor of DBT emerged (F (1, 168) = 7.33, p < .008, d = .70 (0.18–1.20)). These condition differences continued at 12 months (t(168) = 2.95, p < .004, d = .74 (0.22–1.24)) and follow up (t(168) = 3.19, p < .002, d = .80 (0.28–1.30)). The application of the pattern mixture model indicated no significant dependency of the treatment effect on retention (t(52) = 0.54, p = .59) and total hours in treatment (t(52) = 0.14, p = 0.89).

Reliable changes based on study values required change scores of 10.65 or more on the BDI-II. Approximately 47% of O-TAU participants improved and 0% worsened, both at 12 months and at follow up; 61% of DBT participants improved and 0% worsened at 12 months, 68% improved and 0% worsened at follow-up. The two conditions did not differ in net gains of reliable change. For those showing reliable improvement, using the normative data on the BDI-II (Steer & Clark, 1997), a score of 20 was needed for clinically significant change. DBT was significantly better in generating clinically significant improvement at 12 months (34% in O-TAU; 61% in DBT; (χ2 (1) = 4.57, p < .04, OR = 3.02 (1.08–8.44)) and showed a trend towards significance at follow up (41% in O-TAU; 64% in DBT; (χ2 (1) = 3.60, p < .058, OR = 2.66 (0.99–7.36)).

NSSI

Two different measures were used to examine change in NSSI: an interview conducted by a trained assessor (SASII) and client self-reported frequencies (SBQ). Unlike community populations typically treated in DBT studies (e.g., Linehan et al., 1991), our inclusion criteria did not specify recent and/or frequent NSSI. Therefore, not everyone in our sample had engaged in NSSI, and even among those who had recent NSSI, the lethality (assessed by an independent assessor) was relatively low, with most clients (70%) who reported recent self-injury at baseline receiving a lethality rating of either 1 (very low) or 2 (low) on a 1–6 scale, with higher scores indicating more severity. In fact, both of these NSSI measures showed a preponderance of zeros (> 50%) at each post-baseline measure. Thus, we conducted a zero-inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) model where outcome measures were based on average NSSI over the longitudinal period. There was a 44.4% occurrence of NSSI for DBT and 43.3% for O-TAU (p >.10). But given an occurrence, the mean NSSI count was significantly lower for DBT (1.50 ± 1.12) than for O-TAU (5.23 ± 8.47; t(57) = −2.11, p = 0.04). Virtually identical findings were obtained with the SBQ (t(56) = −3.20, p = 0.002), suggesting that a significant intervention effect, in both measures, is being driven by a lower NSSI count in DBT than O-TAU, when an occurrence happened.

Suicide Attempts

Attempts were also measured via interview and self-report. In both instances, self-harming behaviors that were reported as either ambivalent or with clear intent to die were classified as suicide attempts (as opposed to NSSI). As illustrated in Table 2, however, the post-baseline rate of suicide attempts was too low to warrant separate outcome analyses.

Secondary Outcomes

Borderline Criteria

We performed a piecewise model with two phases of change on the SCID-BPD: baseline to 12-months and 12-months to follow-up. On average, there was a greater reduction for DBT versus O-TAU during treatment (Difference estimate = 0.18, se = .041, t(83) = 4.51, p = .0001, d = 1.19 (0.60–1.67)), but not during the follow-up period (Difference estimate = −.08, se = .088, t(74.3) = −1.01, p = .31, d = 0.27 (−0.247–0.75)).

Social Adjustment

The total score of the SAS-SR (see Figure 2) was analyzed using HLM. Results revealed more improvement for DBT patients compared to those in the O-TAU condition in social adjustment (Difference estimate = 0.019, se = .007, t (107) = 2.62, p = .01, d = 0.69 (0.15–1.16)).

Psychotropic Medication Use

This analysis relied on a dichotomous variable of either no medication (0) or at least one psychotropic medication (1), covarying pretreatment usage. Hierarchical Generalized Linear Model (HGLM), used to address the binary form of the outcome, indicated that DBT clients used significantly fewer psychotropic medications post-baseline (Difference estimate = 0.025, se = .009, t (60.1) = 2.79, p = .007, d = 0.74; see Figure 2).

Moderation Analyses

There was good balance with respect to level of global functioning across treatment assignment where 67.7% of DBT participants fell in the higher functioning range versus 65.5% of O-TAU participants using a median split of pretreatment GAF scores. A significant three-way interaction was found for treatment by time by pretreatment GAF score on the primary dependent variable—suicidality (t(51) = 2.13, p = 0.038)). Contrasts between slopes in the HLM analysis were used to explore this interaction. For higher functioning participants there were no significant differences between conditions at month 12 (Difference estimate = .58, se = .544, t(56.6) = 1.07, p = .29, d = 0.28 (−0.23–0.76)) or at follow-up (Difference estimate = .75, se = .687, t(53.7) = 1.10, p = .28, d = 0.29 (−0.22–0.77)). Among the lower functioning participants, there was a non-significant trend toward a difference in favor of DBT at month 12 (Difference estimate = 1.57, se = .81 t(62.7) = 1.93, p = 0.058, d = 0.51 (−0.02–0.99)) and a significant difference at follow-up (Difference estimate = 2.58, se = 1.05, t(57.7) = 2.45, p = 0.017, d = 0.65 (0.11–1.12). With regard to depression, as measured by the BDI-II, there was no statistically significant moderation effect of global functioning at baseline (t(52) = 0.33, p = 0.75).

Discussion

Despite underfunding, an emphasis on short-term treatment (Gallagher, 2011), and a dependence on trainees as therapists (Minami et al., 2009), CCCs are under a tremendous pressure to provide services for severely distressed college students (Kitzrow, 2003). This expanded role is not just driven by client demand; it has also been raised by the institutional and human costs of tragedies such as the shootings in recent years at Virginia Tech and Northern Illinois University, which in both instances involved students thought to have been suicidal (Schwartz & Kay, 2009).

The present study shows that DBT can be adapted and implemented successfully in CCCs to treat students presenting with a complex, multi-problem, suicidal profile. DBT delivered by trainee therapists with regular supervision successfully, and differentially, impacted suicidality, depression, NSSI count, BPD symptoms, psychotropic medication use, and social adjustment. DBT participants made significant gains, with depression moving from a pretreatment score in the severely depressed range to a follow-up score in the minimal range of scores for the BDI-II. Moreover, none of the DBT clients exhibited reliable worsening in suicidality over the course of treatment whereas this was not the case in the O-TAU condition. This finding suggests that DBT may be a particularly effective and safe treatment for severely distressed clients being treated in the CCC context.

DBT adherence ratings indicate that on average the trainee therapists in this study were sufficiently adherent to DBT treatment strategies and interventions. Because we endeavored to mimic “real world” training and supervision conditions, we did not require therapists to achieve adherence levels prior to taking on research treatment cases. Thus, these mean adherence scores reflect both early sessions, with generally lower adherence scores, and later sessions, with generally higher adherence scores. Overall, mean scores around 3.9 suggest reasonably high levels of learning and adherence, and suggest these can be achieved through moderate levels of training and supervision that could be replicated in other counseling centers.

These positive findings in favor of DBT are unlikely to be due to methodological weaknesses such as a weak control condition, higher expectations by experimental participants, lack of expertise by clinician/supervisor in treating BPD, differential access to treatment, differential training, or differential allegiance to treatment. Both treatments were provided within the same clinic, overseen by expert supervisors with strong allegiance to their particular treatment approach, and delivered by therapists with similar training and supervision intensity.

The O-TAU comparison condition appears to have been effective in its own right. The supervisor was selected based on community recognition of expertise with this population (similar to Linehan, Comtois, Murray et al., 2006), and the O-TAU condition showed significant improvement (within-subjects) on most measures. In depression, for example, the impact of O-TAU and DBT was comparable until about six months of treatment (see Figure 2) and average endpoint depression levels for O-TAU were within one standard deviation of the clinical cutoff of the BDI-II. However, this control condition was optimized. Therapists in this condition were trained and supervised by an expert in suicidality and BPD, who published in this area and had extensive experience supervising trainees with difficult cases. This finding may not generalize to treatment provided by CCC trainees not supervised by suicidality experts.

This study surprisingly obtained higher dropout rates (35%) than some other DBT studies (e.g., Linehan et al., 1991). There are a few possible explanations. First, the natural breaks in treatment at a CCC (e.g., Winter and Summer breaks) may have interrupted treatment enough that it was difficult for participants to reconnect. Second, the sample recruited for this study was, on average, somewhat higher functioning than community DBT studies, with participants not being as likely to be engaging in severe NSSI or suicide attempts, only meeting three or more BPD criteria, and being able to function, at least at baseline, in a college setting. Thus, unlike community samples, these college students may have been able to maintain some functionality in the short-term even when not in treatment. Last, but not least, not all students stopping treatment before 7 months of treatment were in fact clinical dropouts: Some students across both conditions mentioned at the time or later during exit interviews that they felt better and no longer needed the treatment, and some were students who transferred to different schools and were simply unable to continue. We did foresee that there might be a sub-segment of the student population who might recover more rapidly than others—hence our decision to allow participants to terminate therapy within a range of time (7–12 months), as opposed to requiring every student to stay in a comprehensive approach such as DBT for the full year.

In the future, the association between treatment dosage to outcome in DBT should be studied systematically, including randomized trials where participants are assigned to different lengths and/or modalities of DBT treatment. This study’s higher dropout rate and participants’ reduced access to skills groups due to campus schedules has resulted, on average, in relatively fewer number of DBT sessions than that expected for weekly treatments lasting up to one year (i.e, the mean number of individual sessions among DBT treatment completers was 34 (SD = 10)). Thus, although the findings favor DBT, it is possible that the limited number of individual and group sessions completed could have reduced the potency of the DBT treatment.

Moderation analyses suggest that DBT might be particularly effective for complex suicidality among college students who are lower in global functioning (GAF baseline score 50 and below). This is not particularly surprising, as DBT was originally developed to work with lower functioning individuals (Linehan et al., 1991); however, this finding has important implications for matching clients to treatments at CCCs. These findings suggest that a stepped care approach might be viable in which the full outpatient DBT package may only be delivered to those with a lower functioning profile (i.e., college students who present with severe suicidality and depression, BPD features, and lower GAF scores). There may be other opportunities for efficiency that should be explored in research with severe cases in CCCs.

Despite multiple strengths, this study has methodological limitations. It is not possible to conclude from the present study that DBT out-performed psychodynamically oriented therapy, despite the fact that the O-TAU supervisor is well known in this area, because the implementation of the O-TAU intervention, as a psychodynamic approach, was not carefully controlled or monitored for adherence. Moreover, O-TAU and DBT therapists differed somewhat in terms of background and professional affiliation, and it is not known how these differences may have affected results.

Although total number of hours in treatment did not moderate treatment effects, there were significant treatment differences in attendance of group sessions, which emerged as an inherent difference between these approaches. DBT requires clients to participate in both the individual and group components of therapy to remain in treatment. Beyond requiring that O-TAU offer both individual and group treatment (weekly), the study did not impose conditions on how treatment should be carried out, as more intrusive requirements could have fundamentally changed the O-TAU treatment, resulting in essentially developing an ad hoc manualized alternative, which was not the intent of the study design.

Similarly, the present study speaks to the effectiveness of a comprehensive DBT package (individual, group, between-session consultation to the patient, and consultation team for therapists) in treating students presenting to CCCs but cannot address the role of DBT components if applied separately. Most CCC administrators might prefer to offer DBT skills groups only, to keep costs low. However, in comprehensive DBT, the individual therapist plays a major role in promoting group attendance and motivating the student to get back into group after missing session, and ensuring the generalization of skills and having a consultation team for therapists are also essential (Linehan, 1993a). Whether or not DBT group skills training alone can be effective with a severe multi-problem college sample will need to be addressed in future studies. Moreover, this study was powered to ask outcome questions, and although simple moderation analyses were successfully performed analyzing treatment outcome by level of student global functioning, the study was underpowered to address other possible interactions, such as between level of global functioning and participants’ diagnostic and clinical profiles (e.g., comorbid substance abuse) or demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, ethnicity).

There are noteworthy limitations in terms of adherence procedures and the assessment timeline. Although we utilized the DBT adherence system available when this project was first proposed, it is not the most current one, and, although purposeful for other reasons, our study did not require DBT therapists to achieve adherence levels before starting to see clients—a factor that may have influenced mean adherence ratings. Additionally, O-TAU sessions were not rated for DBT adherence and therefore the study failed to address treatment diffusion. Lastly, this study was envisioned as a combination of effectiveness and efficacy elements, requiring some compromise relative to an efficacy-only randomized trial. For example, allowing participants to stay in treatment between 7 and 12 months meant that not all participants completed a post-test treatment assessment at the same time. The use of mixed effects analyses in evaluating treatment effects helped compensate for this design feature as they detect different change patterns across condition and time, instead of relying on differences at specific time points.

Universities are increasingly faced with difficult choices of how to allocate resources but it seems clear that CCCs must find a way to address complex and severe problems of students on campus (Gallagher, 2011). The increase in severity of student problems, and the large institutional and human costs (e.g., lawsuits, publicity, concerns about campus safety) that come from failing to prevent or to treat severe problems means that they cannot be ignored (Schwartz & Kay, 2009). This is a change in the historic role of CCCs (Kitzrow, 2003) and the research and treatment development community need to help CCCs find an effective new posture.

In that context, evidence-based treatments in general offer hope to students and to the institution alike (Cooper, 2005). The transition into adulthood is a particularly unique period, and a time when individuals are likely to experience the onset of mental disorders that might persist (Zivin et al., 2009). Colleges and Universities directly touch the lives of nearly half of the population of the United States (Stoops, 2004). If DBT can effectively treat severe mental health problems, such as suicidality, depression, and NSSI among college students, the public health of the entire population could be impacted over time.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grant R34MH071904 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Principal Investigator: Jacqueline Pistorello). The authors would like to thank Dr. Patricia Chatham in particular, as well as Dr. Grant Miller, Dr. Chad Shenk, Dr. Victoria Follette, Jennifer Villatte, Dr. Karen Erickson, Dr. Larry Pruitt, Dr. Sabrina Darrow, Susan Daflos, Dr. Melanie Watkins, Dr. Michael Katrichak, Katrina Crenshaw, Dr. Lindsay Fletcher, and the faculty and staff at Counseling Services at the University of Nevada, Reno for their support. We also want to thank Dr. Steven C. Hayes for statistical consultation and editing. Lastly, we want to acknowledge the invaluable contribution made by the brave young women and men who consented to participate in this research project.

Footnotes

Special Circumstances: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Pretreatment data from this study were analyzed as part of a dissertation and appear in: Iverson, K. M., Follette, V. M., Pistorello, J., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (in press). An investigation of experiential avoidance, emotion dysregulation, and distress intolerance in young adult outpatients with borderline personality disorder symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Data collected from therapists in this study appears in two additional publications: Miller, G. D., Iverson, K. M., Kemmelmeier, M., MacLane, C., Pistorello, J., Fruzzetti, A. E., et al. (2011). A preliminary examination of burnout among counselor trainees treating clients with recent suicidal ideation and borderline traits. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 344–359; and Miller, G. D., Iverson, K. M., Kemmelmeier, M., MacLane, C., Pistorello, J., Fruzzetti, A. E., et al. (2010). A pilot study of psychotherapist’s trainees’ alpha-amylase and cortisol levels during treatment of recently suicidal clients with borderline traits. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 228–235.

For more information about measures created by Linehan and colleagues, see the Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinics website at: http://depts.washington.edu/brtc/sharing/publications/assessment-instruments

Contributor Information

Jacqueline Pistorello, Counseling Services, University of Nevada, Reno.

Alan E. Fruzzetti, Department of Psychology, University of Nevada, Reno

Chelsea MacLane, Counseling Services, University of Nevada, Reno.

Robert Gallop, Department of Mathematics, Applied Statistics Program, West Chester University.

Katherine M. Iverson, Counseling Services and Psychology Department, University of Nevada, Reno

References

- American College Health Association (ACHA) ACHA-National College Health Assessment II: Reference group executive summary Spring 2011. Hanover MD: American College Health Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown KG. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benton SA, Robertson JM, Tseng W, Newton FB, Benton SL. Changes in counseling center client problems across 13 years. Professional Psychology, Research & Practice. 2003;34:66–72. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.34.1.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu SM, Olfson M. Mental health of college students and their non–college-attending peers: Results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1986;3:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatham PM. Treatment of the borderline personality. New York: Jason Aronson; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SE. Evidence-based psychotherapy practice in college mental health. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2005;20:1–6. doi: 10.1300/J035v20n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) 2011 Annual Report (Publication No STA 12-59) 2012 Retrieved in January, 2012 from http://ccmh.squarespace.com.

- Drum DJ, Brownson C, Denmark A, Smith SE. New data on the nature of suicidal crises in college students: Shifting the paradigm. Professional Psychology, Research & Practice. 2009;40(3):213–222. doi: 10.1037/a0014465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenbaum J. Dialectical behaviour therapy: An increasing evidence base. Journal of Mental Health. 2007;16:51–68. doi: 10.1080/09638230601182094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID–I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Personality Disorders (SCIDII) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti AE, Santisteban DA, Hoffman PD. Dialectical behavior therapy with families. In: Dimeff LA, Koerner K, editors. Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice: Applications across disorders and settings. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 222–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher RP. National survey of counseling center directors. Alexandria, VA: International Association of Counseling Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Groves SS, Backer HS, van den Bosch LMC, Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy with adolescents: A review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00611.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson K, Shenk C, Fruzzetti AE. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for women victims of domestic abuse: A pilot study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:242–248. doi: 10.1037/a0013476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D. Psychotherapy outcome research: Methods for reporting variability and evaluating clinical significance. Behavior Therapy. 1984;15:336–352. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(84)80002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobes DA, Jacoby AM, Cimbolic P, Hustead LAT. Assessment and treatment of suicidal clients in a university counseling center. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1997;44:368–377. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.44.4.368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadison R, DiGeronimo TF. College of the overwhelmed: The campus mental health crisis and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53:983–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzrow MA. The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. The National Association of Student Personnel Administrators Journal. 2003;41:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kröger C, Kosfelder J. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:936–951. doi: 10.1037/a0021015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, Morse JQ, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:371–390. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Unpublished manuscript. Seattle: University of Washington; 1981. Suicidal behaviors questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral therapy of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993b. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner A. Suicide attempt self-injury interview (SASII): Development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:303–312. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of Dialectical Behavior Therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Lockard JS, Wagner AW, Tutek D. Unpublished manuscript. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1996. DBT Expert Rating Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Minami T, Davies DR, Callan Tierney S, Bettman JE, McAward SM, Averill LA, et al. Preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of psychological treatments delivered at a university counseling center. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:309–320. doi: 10.1037/a0015398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear modeling: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Liu X. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of behavioral research, methods, and data analysis. San Francisco: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Costa PT, Bagby R. Evaluation of the SCID-II personality disorder traits for DSM-IV: Coherence, discrimination, relations with general personality traits, and functional impairment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:626–637. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz CJ. The Mixed-Model ANOVA: the truth, the computer packages, the books. American Statistician. 1993;47:48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz V, Kay J. The crisis in college and university mental health. Psychiatric Times. 2009;26:32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Bocca FK. Ensuring balance distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Clark DA. Psychometric characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory–II with college students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 1997;30(3):128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stoops N. Population characteristics (Publication No P20-550) Washington, DC: US. Census Bureau; 2004. Educational attainment in the United States: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Promoting mental health and preventing suicide in college and university settings. Newton, MA: Education Development Center, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. Substance use disorders and Cluster B personality disorders: Physiological, cognitive, and environmental correlates in a college sample. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:515–535. doi: 10.1081/ADA-200068107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:33–41. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM. Naturalistic evaluation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80052-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Spinger-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:1111–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Purington A, Eckenrode J, Barreira J, Abrams GB, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury in a college population: General trends and sex differences. Journal of American College Health. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.529626. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin K, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;117:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]