Abstract

The clinicopathologic heterogeneity of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) is driven by diverse, somatically acquired genetic abnormalities. Recent technological advances have enabled the identification of many new mutations, implicating novel pathways in MDS pathogenesis, including RNA splicing and epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Molecular abnormalities, either somatic point mutations or chromosomal lesions are identified in the vast majority of MDS cases and underlie specific disease phenotypes. As the full array of molecular abnormalities is characterized, genetic variables will likely complement standard morphologic evaluation in future MDS classification schemes and risk models.

Keywords: RNA splicing, cytogenetic, epigenetic

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic disorders characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, peripheral blood cytopenias, and a propensity for leukemic transformation. Morphologic dysplasia identified on examination of the bone marrow is a defining feature of MDS and serves as an important criterion for disease classification. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system currently recognizes seven distinct pathologic subtypes of MDS based on these morphologic features, the percentage of bone marrow cells that are blasts and the number of affected hematatopoietic lineages (Table 1) (1). The rapidly expanding compendium of molecular lesions in MDS offers the possibility of major advances in diagnosis, estimation of prognosis, prediction of therapeutic response, and the development of novel therapies for patients with this disease.

Table 1. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of MDS and MDS/MPN neoplasms.

(1, 148, 149). Cytopenias are defined as hemoglobin < 10g/dL, absolute neutrophil count < 1.8 × 109/L, and platelets < 100 × 109/L.

| Disease | Peripheral blood findings | Bone marrow blood findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

Refractory cytopenias with unilineage dysplasia

|

RCUD | Uni- or bicytopenia | Unilineage dysplasia(≥10% of cells in one myeloid lineage) |

| Blasts < 1% | Blasts <5% | ||

| Ring sideroblasts comprising <15% of erythroid precursors | |||

|

| |||

| Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts | RARS | Anemia | Ring sideroblasts comprising ≥15% of erythroid precursors |

| Blasts absent | Dysplasia limited to erythroid lineage | ||

| Blasts <5% | |||

|

| |||

| Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia | RCMD | Cytopenia(s) | Dysplasia in ≥10% of cells in more than one myeloid lineage |

| Blasts < 1% | Blasts <5% | ||

| No Auer rods | No Auer rods | ||

| Monocytes < 1×109/L | |||

|

| |||

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts-1 | RAEB-1 | Cytopenia(s) | Dysplasia in ≥1 lineage |

| Blasts <5% | Blasts 5–9% | ||

| No Auer rods | No Auer rods | ||

| Monocytes < 1×109/L | |||

|

| |||

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts-2 | RAEB-2 | Cytopenia(s) | Dysplasia in ≥1 lineage |

| Blasts 5–19% | Blasts 10–19% | ||

| +/− Auer rods | +/− Auer rods | ||

| Monocytes < 1×109/L | |||

|

| |||

Myelodysplastic syndrome - unclassified

|

MDS-U | Cytopenias | Unequivocal morphologic dysplasia in <10% cells of at least one lineage when accompanied by a clonal cytogenetic abnormality |

| Blasts < 1% | Blasts <5% | ||

|

| |||

| MDS with isolated del(5q) | — | Anemia | Normal-increased megakaryocytes with hypolobated nuclei |

| Platelet count normal/increased | Blasts <5% | ||

| Blasts < 1% | Isolated del(5q) cytogenetic abnormality | ||

| No Auer rods | |||

|

| |||

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | CMML | Persistent monocytosis > 1×109/L | Dysplasia in one or more myeloid lineages |

If dysplasia absent, diagnosis can be made if:

| |||

| No Philadelphia chromosome or BCR-ABL1 fusion gene | |||

| No rearrangement of PDGFRA or PDGFRB | |||

| Blasts(<20% | |||

|

| |||

| Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm, unclassifiable | MDS/MPN | Clinical, laboratory, morphological features of MDS; <20% bone marrow blasts | |

| and | |||

Prominent myeloproliferative features

| |||

| and | |||

| No prior MDS or MPN; no BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, no rearrangement of PDGFRA/B, no isolated del(5q) or 3q abnormalities | |||

| or | |||

| De novo disease with(mixed(MDS/MPN features that cannot be assigned to another category of MDS, MPN, or MDS/MPN | |||

With recent technical and scientific advances, molecular abnormalities, including copy number abnormalities and point mutations, can now be identified in the vast majority of MDS cases. Metaphase cytogenetic analysis detects chromosomal abnormalities in approximately 50% of cases (2, 3), though abnormalities in nearly 80% of cases are found using sensitive techniques such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarrays or array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) (4). Clinical MDS risk stratification using the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) integrates cytogenetic information, along with bone marrow blast percentage and peripheral blood counts, to distinguish four prognostic subgroups (5). Recent analysis of a large, international data set enabled further refinement of karyotype information, defining 19 distinct cytogenetic categories which classify five prognostic subgroups (2).

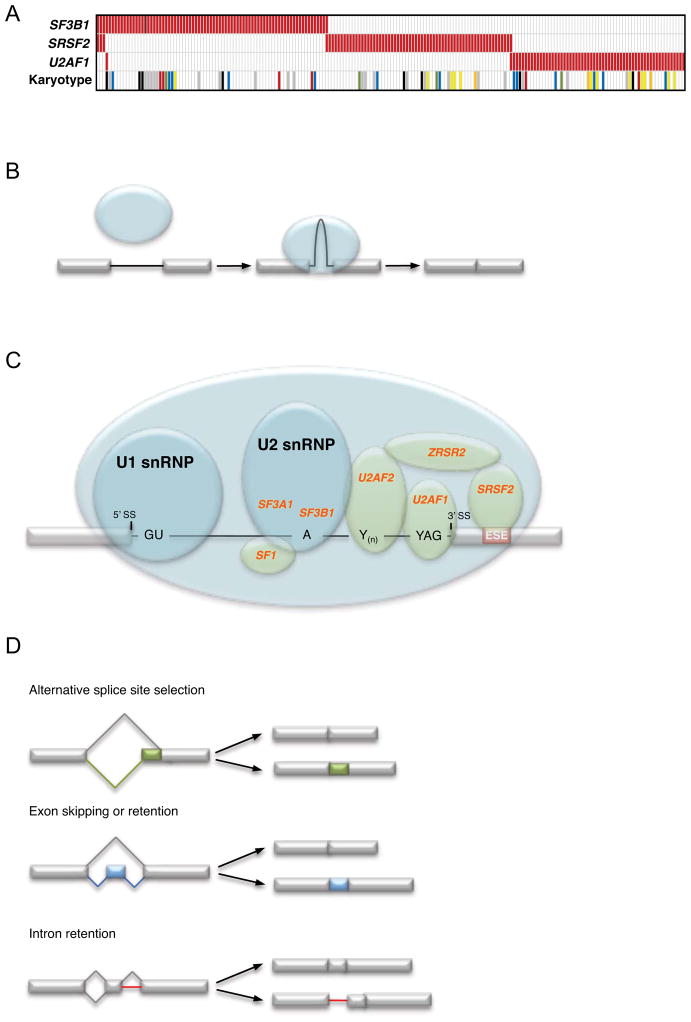

Somatic point mutations can be identified in more than 50% of MDS cases, including a majority of those with a normal karyotype (Figure 1) (6, 7). These emerging genetic data have transformed our understanding of MDS pathophysiology, implicating new biological pathways and providing a new tool to deconstruct the complexity of MDS phenotypes. Recurrent mutations have been identified that alter a number of essential cellular processes including RNA splicing, epigenetic regulation of gene expression, DNA damage response, and tyrosine kinase signaling. Specific mutations in these pathways are, in some cases, tightly associated with distinct morphologic features or clinical phenotypes. For example, mutations in SF3B1 are associated with the presence of ring sideroblasts (6, 8); SRSF2, TET2, and ASXL1 mutations are enriched in the overlap myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms with marked myelomonocytic differentiation (6, 9). Combinations of point mutations and chromosomal abnormalities likely underlie a large portion of the clinicopathologic heterogeneity of MDS.

Figure 1. Somatic mutations in 255 cases of myelodysplastic syndrome with a normal karyotype or a −Y karyotype.

Among cases with a normal karyotype or a −Y karyotype, 72% harbor somatic mutations in at least 1 of 17 genes tested. Each column represents one patient sample, and each row corresponds to mutations in a gene or gene family. TK pathway denotes mutations in genes that activate tyrosine kinase signaling (NRAS, KRAS, BRAF, CBL, and JAK2). Modified from Reference 7 and based in part on Reference 7a, with permission.

RNA SPLICING

Recurrent somatic mutations in components of the spliceosome have recently been identified using whole genome and whole exome sequencing of MDS patient samples (6, 8, 10). As a class, these mutations are remarkably common, affecting 45–85% of MDS, depending on morphologic subtype. Splicing mutations are generally enriched in diseases characterized by morphologic dysplasia, such as MDS, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and AML with myelodysplasia-related changes. By contrast, spliceosome mutations occur at low frequency in myeloid diseases without dysplasia, including de novo AML and the myeloproliferative neoplasms (6). While the molecular consequences of these genetic lesions have not been elucidated, the identification of mutations in genes encoding multiple components of this enzyme complex implicates aberrant splicing in the pathophysiology of a large proportion of MDS cases.

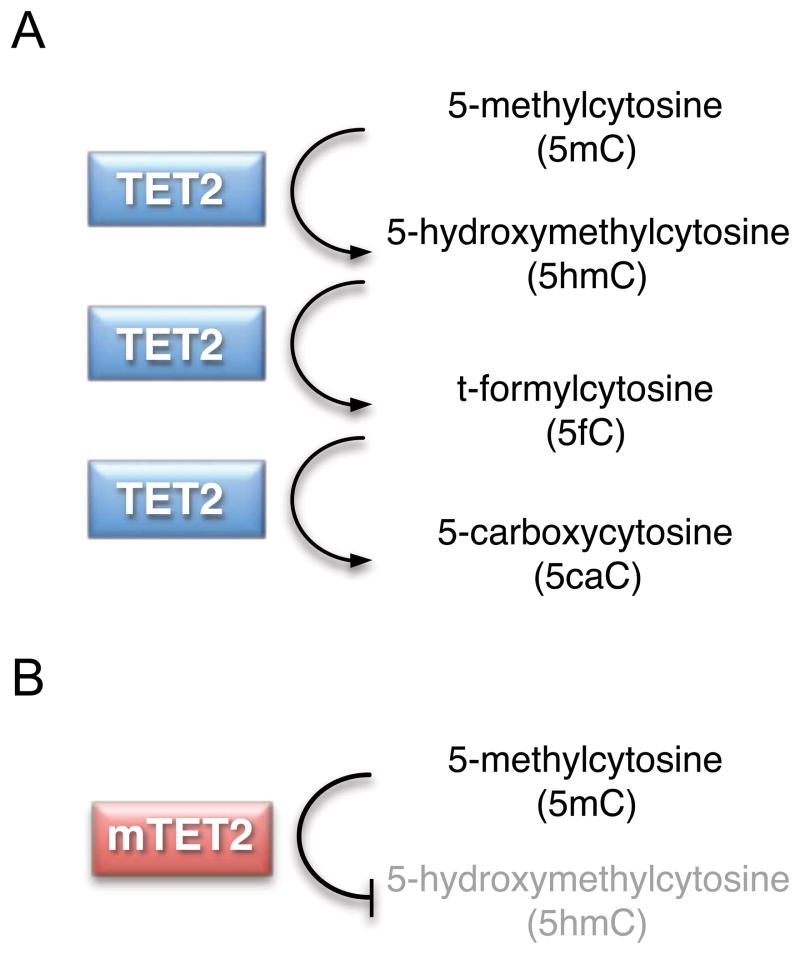

The spliceosome mediates excision of introns and ligation of flanking exons to generate mature mRNAs from precursor mRNA (Figure 2b). Alternative splicing is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism enabling production of multiple mRNA and protein isoforms from a single gene. Deep sequencing of mRNA across human tissues has revealed that 90–95% of multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing, resulting in production of more than 100,000 distinct mRNA species from just 25,000 protein-coding genes (11, 12). Several distinct types of alternative splicing have been identified in normal physiology (Figure 2d). Exon skipping, whereby an exon and its flanking introns are excised together from a transcript, is most common and accounts for 30–40% of alternative splicing events. Other types of alternative splicing events include alternative 5′ or 3′ splice site selection, alternative first or last exon utilization, tandem 3′ UTR creation, and rarely intron retention. Aberrantly spliced mRNA species can be degraded by the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway. Abnormal transcripts that escape NMD-mediated elimination can be translated into mislocalized or dysfunctional proteins that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer and other diseases (13).

Figure 2. Mutations that affect RNA splicing machinery are common in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

(a) Mutations in genes that encode components of the RNA splicing machinery are mutually exclusive and occur in a range of cytogenetic contexts. Each column represents one sample. Mutations are shown as red bars. Specific karyotypic abnormalities are color coded as follows: red, isolated deletion on the long arm of chromosome 5 [del(5q)]; green, −7/del(7q) alone or +1 abnormality; blue, isolated +8; yellow, isolated del(20q); black, complex; white, normal or −Y; orange, unknown. (b) Schematic of RNA splicing showing spliceosome-mediated precursor--messenger RNA processing that causes the excision of an intervening intron and ligation of flanking exons. (c) Selected components of the spliceosome are mutated in MDS. The U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) binds to the 5ʹ splice site (5ʹ SS), and the U2 snRNP binds to the branch point. The U2 auxiliary factor (U2AF), which is composed of U2AF1 and U2AF2 subunits, binds to the 3ʹ splice site (3ʹ SS) and polypyrimidine tract [Y(n)]. Serine- and arginine-rich proteins bind to the exonic splice enhancer (ESE). The genes encoding SF3A1, SF3B1, U2AF1, U2AF2, SF1, SRSF2, and ZRSR2 are mutated in myeloid neoplasms and are shown in red. (d) Various outcomes of alternative splicing occur in normal physiology, including alternative splice-site selection, exon skipping, and intron retention.

The spliceosome consists of core small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and non-snRNP accessory proteins (Figure 2c). Whereas snRNPs are critical to the structural and enzymatic function of the splicesome, non-snRNP proteins are important for structural assembly, splice-site selection, and coordination of selection alternative splicing events. Normal pre-mRNA splicing occurs by a series of well-regulated steps, starting first with identification of appropriate splice sites, followed by assembly of the spliceosome complex and catalysis of cleavage and ligation reactions. Splice site recognition is mediated by specific interactions between spliceosomal components and conserved RNA sequence motifs. The principal cis-acting signals include the 5′ and 3′ splice sites (invariant GU and AG, respectively), a polypyrimidine tract (PPT) just upstream of the 3′ splice site, and an adenine-containing branch point upstream of the PPT. The pattern of alternative splicing is regulated in a tissue-specific fashion by the interaction between trans-acting regulatory proteins and these locus-specific cis-acting RNA sequence elements (14).

Recurrent mutations have been identified in eight different genes involved in the early steps of U2 snRNP assembly/function (SF3A1, SF3B1, ZRSR2, SRSF2) and 3′ splice site recognition, including branch point sequence binding (SF1), polypyrimidine tract binding (U2AF2), 3′ splice site binding (U2AF1). In nearly all instances, mutations in components the splicing machinery are found to be mutually exclusive (Figure 2a) (6). Several genes are subject to recurrent heterozygous missense mutations (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1), while others display diverse mutation types throughout the open reading frame (ZRSR2) (Figure 2c). Further studies will be required to clarify which lesions cause a loss of function, and which cause a gain or alteration of protein function.

SF3B1

SF3B1 is the most frequently mutated spliceosomal gene in MDS, affecting 14–28% of unselected patients (6, 8, 15, 16). Mutations of SF3B1 are strongly associated with the presence of ring sideroblasts. Among MDS patients with ringed sideroblasts, 50–75% have SF3B1 mutations. The presence of an SF3B1 mutation has a 98% positive predictive value for ring sideroblast morphology and, interestingly, the percentage of ring sideroblasts in a given patient is proportional to the SF3B1 mutant allele frequency (15). Together, these data support a causal mechanistic relationship between SF3B1 mutation and the ring sideroblast morphology.

Initial studies found SF3B1 mutations to be independently associated with prolonged overall and leukemia-free survival, while a subsequent series concluded that SF3B1 mutation status provided no additional prognostic information beyond established morphologic risk categories (8, 15, 17). Compared to MDS cases without SF3B1 mutation, MDS with SF3B1 mutation is characterized by higher platelet counts (8, 15–17), lower bone marrow blast count (8, 15, 16), and higher white blood cell count (8, 16).

SF3B1 encodes a subunit of the splicing factor 3b complex, which together with the SF3A complex and the U2 snRNA comprise the U2 snRNP. SF3B1 mutations are heterozygous missense substitutions, predominantly affecting conserved residues within the carboxy-terminal HEAT repeats. Approximately 90% of mutations involve five amino acids, K700 (58%), K666 (11%), H662 (10%), E622 (7%), and R625 (6%). Based on protein structure prediction algorithms, it is suggested that mutated SF3B1 remains structurally intact, though presumably with altered function (8). The nature of SF3B1 dysfunction is unclear, however, as no global splicing abnormalities have been identified in patients with SF3B1 mutations and no experimental model has been reported.

U2AF1

Mutations in U2AF1, a subunit of the U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor (U2AF) that binds the 3′ splice acceptor site, are present in 8–9% of unselected MDS samples (6, 10). In contrast to SF3B1 mutations, U2AF1 mutations are associated with increased rate of progression to AML, despite no difference in median blast count, IPSS or other clinical parameters. U2AF1 mutations are heterozygous missense substitutions within the conserved zinc finger domains, predominantly at codon S34, and less commonly at Q157. Uniparental disomy and mutations or deletions of the remaining allele are uniformly absent. Functional analysis of the U2AF1 S34 allele demonstrated increased splicing activity using in vitro reporter assays (10) and production of aberrant splice products using RNA sequencing and exon arrays (6). In vivo, murine hematopoietic stem cells expressing mutant U2AF1 had reduced competitive repopulation capacity (6).

Several studies have shown MDS-specific splicing patterns in genes known to regulate cell growth and survival, but it is not clear whether these changes are caused by mutations in genes encoding splicing factors (18, 19). The observation that certain mutations display a close association with specific morphologic subtypes, such as SF3B1 mutations with RARS/RARS-T/RCMD-RS and SRSF2 mutations with CMML, suggests unique mechanisms of action or a context-dependence. As a whole, splicing mutations are found in a mutually exclusive pattern and are restricted to genes involved in 3′ splice site recognition and U2 snRNP function. Consequent disruption of 3′ splice site recognition could result in altered exon utilization or activation of cryptic 3′ splice sites, thus creating novel protein isoforms with altered function or ectopic expression of tissue-inappropriate isoforms. Aberrant splicing may also cause quantitative reduction of gene expression via introduction of premature stop codons and activation of nonsense-mediated decay. Moreover, components of the U2 snRNP have been found to interact directly with Polycomb group (PcG) proteins, suggesting a potential role for the splicing machinery in epigenetic regulation of gene expression (20).

EPIGENETICS

Alongside genetic lesions that alter the RNA splicing machinery, mutations in genes encoding epigenetic regulators are among the most common molecular abnormalities in MDS. These lesions alter genes involved in DNA methylation and histone modification. Mutations in epigenetic regulators have the potential to cause widespread alterations in transcriptional programs that can be maintained through cell division, leading to establishment and persistence of the MDS phenotype.

Mutations in several genes involved in DNA methylation are commonly identified in MDS, including DNMT3A and TET2. Cytosine bases are converted to 5-methylcytosine (5mC) by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), primarily in the context of CpG dinucleotides enriched at the site of gene promoters. In this context, cytosine methylation status reduces gene transcription by recruiting methyl CpG binding domain (MBD)-containing repressor complexes or by influencing the binding of transcription factors to promoter elements. By contrast, methylation of intragenic sites is associated with active transcription (21). Patterns of DNA methylation can be maintained through successive rounds of cell division, but shift significantly during cellular differentiation (22).

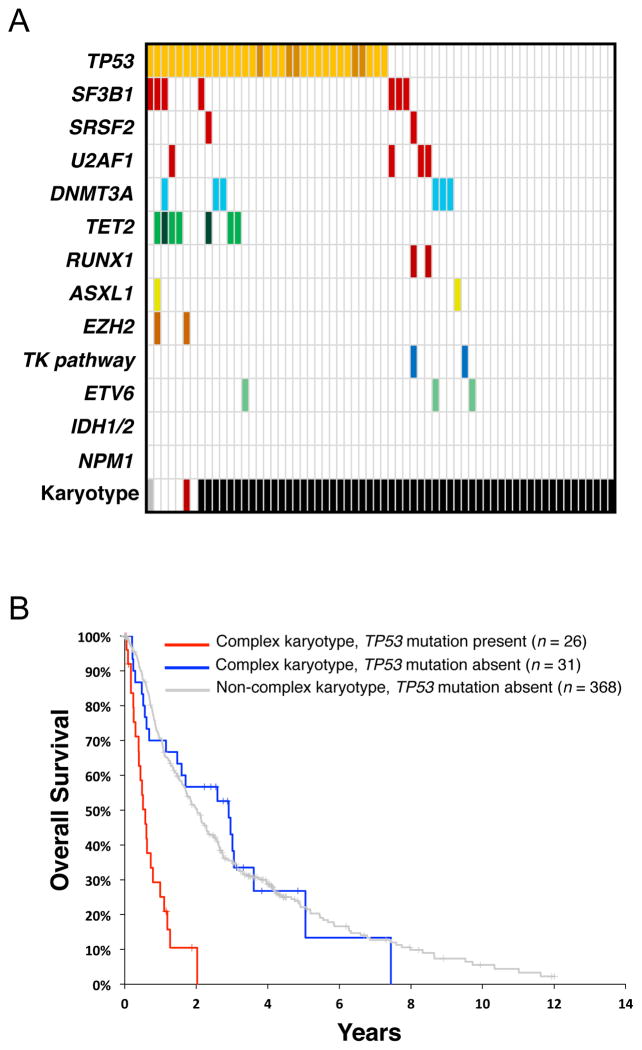

DNMTs have been assigned functional categories based on their de novo (DNMT3A and DNMT3B) or maintenance (DNMT1) methyltransferase activity. These enzymes cooperate to establish initial patterns of methylation and regenerate hemimethylated DNA during replication. 5mC can itself be modified by the 3 paralagous members of the TET family of Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate (2-OG)-dependent dioxygenases (TET1, TET2, and TET3). TET proteins successively oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), t-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC) (Figure 3a) (23). TETs can act on various substrates, including fully and hemimethylated DNA in CG and non-CG contexts (24).

Figure 3.

(A) TET proteins successively oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), t-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC). (B) TET2 mutation (mTET2) results in reduced enzymatic activity and decreased products of 5mC oxidation.

MDS and secondary AML (sAML) are associated with widespread alterations in DNA methylation relative to normal hematopoietic progenitors and de novo AML (25). While these abnormalities are found even in low-risk MDS, the extent of aberrant promoter hypermethylation correlates with disease severity, predicts transformation to sAML (26), and is independently associated with reduced overall survival (27). These observations suggest an important role for aberrant DNA methylation in MDS pathogenesis and serve as rationale for the therapeutic utility of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors.

Two DNMT inhibitors, the nucleoside analogs 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine), are approved for treatment of MDS in the United States. Treatment with these agents yields overall response rates of approximately 40–60% and 5-azacytidine has been shown to prolong overall survival (28, 29). While treatment with DNMT inhibitors induces global promoter hypomethylation (25), the extent of pretreatment promoter hypermethylation does not predict clinical response (27).

DNMT3A

Recurrent mutations in DNMT3A have been found in approximately 22% of de novo AML, 2–8% of unselected MDS, and up to 7% of CMML and primary myelofibrosis (30–33). In MDS, DNMT3A mutations have been associated with worsened survival and a shorter time to leukemic transformation (31, 32). Missense, nonsense, and frameshift mutations have been identified throughout the coding region of the DNMT3A gene, sometimes in the context of copy neutral loss of heterozygosity or compound heterozygosity, suggesting these are loss-of-function mutations (30). However, the most common DNMT3A mutation, found in 30–60% of cases, is a heterozygous arginine-histidine substitution at position 882, which falls within the methyltransferase domain and has been shown to reduce in vitro enzymatic activity (34). This raises the possibility that at least some DNMT3A mutations confer gain of function or dominant negative activity.

Despite an established role for DNMT3A in DNA methylation, murine hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) lacking Dnmt3a show equivalent global levels of 5mC compared to wild-type HSCs (35). Nevertheless, Dnmt3a-deficient HSCs are functionally abnormal, with a distinct bias to self-renewal over differentiation as reflected by enhanced competitive repopulation potential upon serial transplantation and a diminished contribution to lineage-restricted progenitor populations. HSCs lacking Dnmt3a show increased expression of stem cell multipotency-associated genes with concomitant decrease in expression of genes important for differentiation. Closer analysis of locus-specific methylation in Dnmt3−/− HSCs revealed an unexpected combination of hypo- and hypermethylation. Among the most robustly hypomethylated regions in Dnmt3−/− HSCs include Runx1 and Gata3, both of which have increased H3K4 trimethylation, augmented expression, and direct binding by Dnmt3a. Similarly, B cells derived from Dnmt3a-deficient HSCs display hypomethylation and ongoing expression of stem cell-associated genes, such as Runx1. These data suggest that in murine hematopoiesis, Dnmt3a regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation by coordinating repression of the stem cell gene expression program and facilitating differentiation (35).

TET2

TET2 is the most commonly mutated gene in MDS (19–26%) (7, 36, 37) and CMML (42–50%) (38, 39). TET2 mutations are also frequently present in AML, and are enriched in patients with secondary AML, in AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (22–24%), in patients older than age 60 (29%), and in AML with normal cytogenetics (23–30%) (37, 40, 41). In MDS, TET2 mutations are similarly associated with normal cytogenetics and generally co-occur with mutations in other genes (7). While TET2 mutations have emerged as a potentially useful negative prognostic factor in AML with normal cytogenetics (40), there is no clear prognostic significance of these mutations in MDS (7, 36, 39, 42, 43).

TET2 mutations are predicted to result in loss of function, with frequent copy neutral loss of heterozygosity and hemizygous or compound heterozygous mutations. Biochemical studies have demonstrated reduced levels of 5hmC in the genomic DNA of bone marrow cells from patients with TET-mutated malignancies, implicating a compromised catalytic activity of mutant TET2 protein (44). This conclusion is supported by targeted deletion of the Tet2 catalytic domain in mice and introduction of disease-associated catalytic domain mutant TET2 alleles into cell lines, both of which demonstrate that deletion or mutation of TET2 decreases production of 5hmC (Figure 3b) (44–46). Interestingly, patients with low 5hmC levels display a similar clinical phenotype independent of TET2 mutation status, suggesting that 5hmC levels rather than TET2 mutation status, per se, may mediate the observed clinical phenotype.

The functional roles of 5hmC and other TET-dependent products of 5mC oxidation remain incompletely understood. Along with 5mC, 5hmC may be an epigenetic mark that influences gene transcription directly via specific interactions with nuclear factors. TET activity and 5hmC presence appear to be enriched at sites of bivalent histone marks and influence recruitment of Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to target genes (47). Hydroxymethylcytosine may otherwise regulate gene expression indirectly as a demethylation intermediate. Conversion of 5mC to 5hmC could inhibit binding or activity of maintenance methyltransferases, thereby promoting passive, replication-dependent cytosine demethylation. Alternatively, 5hmC may serve as an intermediate species in active, replication-independent demethylation. In this model, 5mC undergoes successive TET-dependent oxidation to 5fC and 5caC, which are then cleaved to cytosine by the base excision repair enzyme, thymine DNA deglycosylase (TDG) (48).

The biologic effect of TET2 inactivation on hematopoiesis has been studied using multiple independent mouse models (45, 46, 49, 50). In each case, inactivation of Tet2 resulted in cell-autonomous expansion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor populations, enhanced HSC self-renewal and replating capacity, and a bias towards myelomonocytic differentiation. Tet2-deficienct mice develop a myeloproliferative phenotype evocative of human CMML, a disease with a high frequency of TET2 mutations. Mice with heterozygous Tet2 deletion (Tet2−/+) exhibit a similar spectrum of hematopoietic abnormalities and a propensity to myeloid malignancies, though with delayed kinetics of onset. Together, these data suggest that reduced TET2 activity in human hematopoietic progenitors may serve an important role in establishing clonal dominance and initiating myeloid transformation.

In patients with TET2-mutated myeloid neoplasms, the mutant allele can be identified in the earliest hematopoietic precursor populations (37, 43). However, monoallelic inactivation in isolation does not appear to compromise functional multipotency, as TET2 mutations or 4q24 microdeletions can be found in both the myeloid neoplastic clone as well as presumably normal lymphocytes (43, 51). Even more provocative is the observation that certain mature lymphoid neoplasms are associated with TET2 mutations, and that in some of these cases the clonal origin may be traced back to a multipotent progenitor (46, 51). Indeed, close examination of Tet2-deficient mice demonstrates dysregulated lymphopoiesis characterized by a reduced number of B cells and an increased T cell compartment that is shifted to immature phenotype. Impaired TET2 function in the earliest hematopoietic precursor may lead to gradual clonal dominance and predisposition to clonally-related multilineage neoplasia.

IDH1/2

Heterozygous missense mutations in two isocitrate dehydrogenase genes (IDH1/2) are found in AML (15–25%)(52, 53) and less frequently in MDS (4–12%) (7, 54) (7, 54, 55). In myeloid neoplasms, IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are mutually exclusive, uniformly monoallelic, and associated with a normal karyotype. IDH1 mutations have been shown to have adverse prognostic value in MDS (7, 54, 55).

IDH1 and IDH2 encode NADP+-dependent enzymes involved in citrate metabolism with subcellular localization to the cytosol and mitochondria, respectively. Mutations mainly affect codon R132 of IDH1 and codons R140 and R172 of IDH2 and result in altered catalytic function. Whereas wild-type IDH proteins convert isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate (αKG), cancer-associated IDH1/2 mutations confer neomorphic enzymatic activity that directly converts α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) (56). 2HG, which is found at high levels in cancers harboring IDH1/2 mutations, is thought to function as an ‘oncometabolite’, inducing alterations genome-wide histone and DNA methylation via competitive inhibition of α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes. AML with IDH1/2 mutations are characterized by a distinct pattern of hypermethylation that is associated with disruption of TET2-mediated 5mC hydroxylation (41). Similarly, reduction of IDH activity or increase of intracellular 2HG interferes with function of histone demethylases and results in increased H3K79 methylation and leukemia-associated HOXA gene expression (57).

EZH2

EZH2 is a member of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), along with EED, SUZ12, and RBBP4, that represses gene expression through trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (58). EZH2 mutations in MDS and other myeloid malignancies cause a loss of enzymatic function (59, 60). Missense mutations cluster in the C-terminal SET domain required for methyltransferase activity, though other mutations (missense, nonsense, splice-site, insertion/deletions, and frame shift) are found throughout the gene, including in the cysteine-rich and protein-protein (EED-binding or SUZ12-binding) interaction domains. By contrast, the heterozygous EZH2 mutations found in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma occur predominantly at Y641 and confer altered enzymatic function as reflected by increased H3K27 trimethylation (61, 62). Disruption of PRC2 in murine bone marrow, via inactivation of Ezh2, Eed, or Suz12, results in augmented hematopoietic stem cell activity, consistent with an early role for loss of EZH2 function in myeloid neoplasia and with recent reports of rare mutations of PRC2 components (EED and SUZ12) and associated factors (JARID2) in myeloid malignancies (63). The disparate biologic effects of EZH2 dysregulation suggest that its function as both oncogene and tumor suppressor is context-dependent and determined by hematopoietic lineage and stage of differentiation.

EZH2 mutations occur in 6% of MDS cases. The gene is located on chromosome 7q, and mutations can be associated with acquired uniparental disomy (UPD) and less commonly 7q deletion (7, 59, 60, 64). EZH2 mutations are more prevalent in lower risk MDS, but are associated with reduced overall survival, independent of other known variables (7). Despite their adverse prognostic impact, however, EZH2 abnormalities are exceptionally rare in AML, suggesting mechanisms other than progression to overt leukemia for their negative clinical effect.

ASXL1

ASXL1 is a homolog of the Drosophila Enhancer of trithorax and polycomb (ETP) group gene Additional sex combs (Asx). The ASXL1 protein contains a C-terminal plant homeo domain (PHD) finger and several nuclear receptor coregulator binding (NR box) motifs. Many proteins that contain PHD fingers are proposed to function as epigenetic “readers” via PHD-dependent binding to trimethylated lysine residues on histones. Asx and its murine homolog Asxl1 regulate homeotic gene expression during embryogenesis by activating or repressing gene expression in a context-dependent manner (65).

ASXL1 is among the most frequently mutated genes in myeloid neoplasms, including MDS (10–20%), CMML (40%), AML (5–30%), and MPN (10%) (7, 66–69). The ASXL1 gene is localized to chromosome 20q11, but falls outside the characterized common deleted region for del(20q) MDS. ASXL1 mutations are more common in MDS with intermediate-risk cytogenetics. By contrast, ASXL1 mutations are 3–5 times more frequent in AML patients older than 60 years of age, are mutually exclusive of mutations in NPM1 in this population and rarely found in combination with FLT3-ITD (68).

In a multivariable analysis, ASXL1 mutations in MDS were associated with reduced overall survival and a shorter time to leukemic transformation, independent of existing clinical parameters (7, 69). In AML, the presence of an ASXL1 mutation is also associated with reduced overall survival, but further predicts a lower rate of complete response to initial therapy (68). The majority of ASXL1 mutations are heterozygous frameshifts or premature stop codons that are predicted to result in a truncated protein lacking the C-terminal PHD finger and nearly all NR box motifs (7, 69). At present, it is unknown whether a stable protein product is expressed from the truncated alleles and if so, whether it mediates a disease phenotype directly via distinct gain of function or dominant-negative activity. Targeted disruption of mouse Asxl1 results in abnormal hematopoiesis marked by progenitor defects in the lymphoid and myeloid lineages, though these mice do not exhibit an overt stem cell defect or morphologic features of dysplasia (70).

TP53

p53, encoded by the TP53 gene on chromosome 17p, is a tumor suppressor that coordinates the response to diverse cellular stresses, including oncogene activation and DNA damage. In response to these stimuli, p53 can induce cell cycle arrest, activate DNA repair pathways and trigger apoptosis, functions mediated largely by its transcription factor activity. TP53 is mutated or deleted in the majority of human cancers, with an incidence of greater than 50% in certain epithelial malignancies including lung and ovarian cancer. The incidence of TP53 abnormalities among hematologic malignancies, however, is relatively low at approximately 10–20% (71).

Loss-of-function somatic mutations in TP53 are present in 4–14% of unselected MDS cases (7, 72, 73) and at least 20–30% in MDS arising after exposure to radiation or alkylating agents (74). TP53 mutations are associated with advanced disease, often marked by severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000), elevated blast count (≥5%), and/or complex karyotype (7, 75). Nearly 80% of patients with TP53 mutations are categorized in the IPSS intermediate 2- and high-risk disease groups (7). Despite this association with high risk clinical features, however, TP53 mutations are still associated with reduced survival after adjusting for IPSS risk group (HR for death = 2.5) (7).

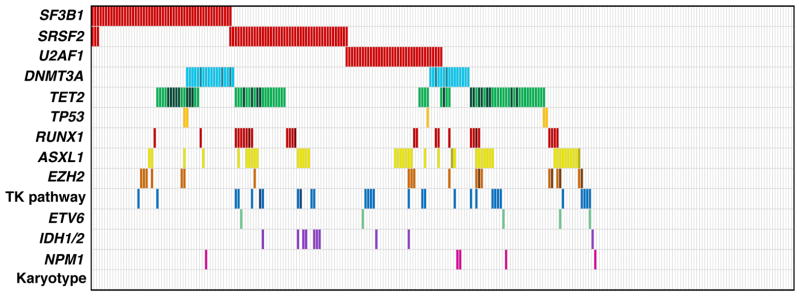

Among MDS patients with complex cytogenetics, nearly half harbor somatic mutations in TP53 (Figure 4a). Indeed, the presence of a TP53 mutation in the context of complex cytogenetics is associated with significantly reduced overall survival (0.58 vs. 2.01 years, P < 0.001). Strikingly, in the absence of TP53 mutation, the overall survival of patients with a complex karyotype is equivalent to that of patients with a non-complex karyotype (2.01 vs. 2.91 years, P = 0.83) (Figure 4b) (7). Adverse prognosis in MDS with complex cytogenetics is also associated with the number of chromosomal abnormalities, as those with >3 lesions have reduced overall survival compared to those with 3 lesions (0.5 vs 1.3 years, P < 0.1) (2).

Figure 4. TP53 mutations are associated with a complex karyotype and reduced overall survival.

(a) A subset of 439 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (7), including those with TP53 mutation (n = 33) or a complex karyotype (n = 57). Each column represents one case, and mutations are represented as colored bars. Specific karyotypes are color coded as in Figure 2. (b) Survival of MDS patients with a complex karyotype, either with (n = 26; red line) or without (n = 31; blue line) TP53 mutations. Survival of MDS patients associated with a noncomplex karyotype and wild-type TP53 (n = 368) is represented as a gray line. TK pathway denotes mutations in genes that activate tyrosine kinase signaling. Modified from Reference 7 with permission.

TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS

Hematopoietic differentiation is driven by the action of transcription factors, which coordinate dynamic programs of lineage-specific gene expression (76). Transcription factors are commonly mutated in hematologic malignancies affecting both lymphoid and myeloid lineages, including MDS. As a whole, these mutations are thought to disrupt normal differentiation and cause aberrant hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, leading to dominance of the mutated clone. RUNX1 and ETV6 are the most commonly mutated transcription factor genes in de novo MDS. Somatic mutations in CEBPA are common in AML, but are very rare in MDS. Germline mutations in GATA2 lead to familial MDS and AML, but somatic mutations are rare.

RUNX1

Among unselected cases of MDS, RUNX1 mutations are identified in 10–20%, with higher rates in patients with prior exposure to chemotherapy or radiation and in those with more advanced disease (7, 77, 78). RUNX1 mutations are associated with severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000), increased bone marrow blasts (>5%), and decreased overall survival independent of IPSS (7, 79). Despite these adverse prognostic features, RUNX1-mutated MDS are rarely found to have concurrent TP53 mutations (7, 80), and are instead associated with activation of RTK-RAS pathway, possibly via mutation of FLT3, NRAS, or NF1 (80). RUNX1 mutations are further associated with distinct cytogenetic features, more often possessing chromosome 7 abnormalities (-7/7q-) in the setting of a normal chromosome 5.

RUNX1, also known as AML1 or CBFA2, is located on chromosome 21q22 and encodes a component of a transcriptional regulatory complex, core-binding factor (CBF). Core-binding factors are heterodimeric transcription factors composed of a DNA-binding α-subunit (RUNX1, RUNX2, or RUNX3) that confers specificity and a non-DNA-binding β-subunit (CBFβ) that regulates heterodimer stability and affinity for DNA. As part of the AML1/ETO (RUNX1/RUNX1T1) translocation, RUNX1 was identified in t(8;21) core-binding factor AML. Though this translocation is rare outside of AML, point mutations in RUNX1 are identified frequently in MDS, AML, and CMML.

The RUNX1 protein contains an N-terminal Runt homology domain that mediates DNA-binding, and a C-terminal transactivation domain that is important for recruitment of transcriptional cofactors. Pathogenic mutations in RUNX1 may be mono- or bi-allelic and, and as a rule, abolish transactivation of target genes (81). Missense mutations predominate and are commonly located in the Runt domain, causing loss of DNA binding with retention of cofactor interactions, resulting in dominant-negative functional activity. Frameshift mutations, by contrast, are found throughout the gene, but usually result in loss of the C-terminal transactivation domain (79).

Disease ontogeny influences the distribution of mutations within the RUNX1 gene. Whereas mutations in de novo MDS/AML are evenly distributed throughout the coding region, nearly all RUNX1 mutations in therapy-related MDS/AML are localized within the N-terminal Runt domain (79). These two classes of RUNX1 mutation, N-terminal missense and C-terminal frameshift, display distinct biological behaviors when expressed during murine hematopoiesis. Mice transplanted with bone marrow expressing a Runt domain-mutated Runx1 develop hepatosplenomegaly, myeloproliferation with increased bone marrow blasts and multilineage dysplasia, and have a high rate of transformation to a leukemic phenotype. In contrast, expression of a C-terminal frameshift mutation results in leukopenia, marked erythroid dysplasia, and a reduced rate of leukemic transformation (82). Recent data support domain-specific contributions to MDS pathogenesis. In a murine model, expression of C-terminal mutant RUNX1 causes accumulation of DNA double-stranded breaks and represses Gadd45a expression, presumably via reduction of DNA damage sensing (83). RUNX1 has been linked to histone modification via regulation of proteasomal degradation of the MLL histone methyltransferase. MDS/AML-associated N-terminal mutations cause loss of H3K4me3 marks within regulatory regions of RUNX1 target gene, PU.1 (84).

Germline mutations in RUNX1 cause familial platelet disorder with propensity to myeloid malignancy (FPD/AML). Individuals with this disease harbor monoallelic RUNX1 mutations, most commonly localized to the N-terminal region, with a clinical phenotype characterized by reduced platelet number and function (85). Approximately one third of patients with FPD/AML will develop AML, often after long latency with a median onset of 33 years of age. Transformation to AML is often associated with multiple somatic lesions, including acquisition of another mutation in the second RUNX1 allele (86).

ETV6

Somatic point mutations in the ETV6 gene (also known as TEL) have been identified in both MDS and AML at a frequency of 1–3%, and heterozygous deletions of the gene also occur rarely (87). In MDS, ETV6 mutations predict poor overall survival independent of the IPSS score, while in AML they are associated with an intermediate risk (7, 88). ETV6 is a transcription factor that is expressed widely throughout hematopoiesis and is required for adult hematopoietic stem cell maintenance (89). ETV6 is the target of multiple translocations in diverse hematologic malignancies, including ETV6-RUNX1 (TEL-AML1) in childhood precursor B cell ALL, ETV6-PDGFRβ in CMML, and rarely ETV6-GOT1 or ETV6-MDS2 in MDS (90). ETV6 abnormalities are thought to contribute to disease pathogenesis by various mechanisms. ETV6 contains a C-terminal DNA-binding (ETS) domain and an N-terminal homodimerization (SAM) domain. When paired with a tyrosine kinase gene, such as ETV6-JAK2, ETV6-PDGFRβ or ETV6-FLT3, the ETV6 SAM domain mediates homodimerization of the fusion oncoprotein, resulting in constitutive kinase activation and consequent neoplastic proliferation (91). Fusions with RUNX1, EVI1, or MN1 alter transcription factor activity and affect the balance differentiation and self-renewal (92, 93). In many ETV6-RUNX1 leukemias, the non-rearranged ETV6 allele is deleted or inactivated, suggesting that wild-type ETV6 possesses tumor suppressor activity (94).

Point mutations in ETV6 are identified throughout the gene and result in a variety of abnormal full-length or truncated proteins. ETV6 mutations often involve the homodimerization or DNA-binding domains and generally result in abrogation of transcriptional repressor function (95). Acquired UPD12p or loss of heterozygosity (LOH) are uncommon in the context of ETV6 mutations, and mutations are generally heterozygous (7, 95). Analysis of primary AML samples, however, reveals that one third of cases show markedly reduced levels of ETV6 protein, despite normal mRNA levels and an absence of mutation or deletion. Wild-type ETV6 may be further inhibited by dominant-negative activity of the mutant ETV6 protein, as suggested by animal models (95).

SIGNALING PATHWAYS

Normal hematopoiesis is critically dependent on appropriate spatiotemporal regulation of growth factors and cytokines that activate intracellular kinase signaling cascades upon binding cell surface receptors. Mutations in these pathways can lead to constitutive signaling activation or hyper-responsiveness to endogenous stimuli. As a consequence, affected clones display enhanced proliferation, decreased apoptosis, or alteration of normal development and growth regulation. Among myeloid malignancies, recurrent gain-of-function mutations in receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases are commonly found in diseases such as AML (FLT3, KIT), chronic eosinophilic leukemia/hypereosinophilic syndrome (PDGFR, FGFR1), and the myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPL, JAK2).

In comparison to AML and MPN, RTK mutations are rare in MDS. For example, FLT3 abnormalities, are at least 10-fold more common in de novo AML (30%) than in MDS (2–3%) (96, 97). This small subset of MDS patients with FLT3 mutations has more advanced disease, more often has complex karyotype and concurrent RAS mutations, and displays a shorter time to leukemic transformation (96). Indeed, FLT3 mutations are substantially more common in secondary AML (sAML) arising in the setting of pre-existing MDS (12%) than in MDS as a whole (97). Similarly, the frequency of KIT mutations, though rare overall, is twice as high in sAML than in MDS (1.5% vs. 0.7%) (97).

RAS FAMILY

A subset of MDS cases bear activating mutations in the RAS family of proto-oncogenes, small guanosine triphosphatases that are activated by cell surface receptors and regulate signaling cascades that are critical for cell growth and survival. NRAS mutations have been identified in approximately 10% of MDS cases, while KRAS mutations are present in only 1–2% (97). NRAS mutations have a strong association with severe thrombocytopenia and increased bone marrow blasts (7), and acquisition of NRAS mutation may presage transformation to acute leukemia (98). While NRAS mutations are associated with inferior outcomes when considered alone (99), they do not provide significant prognostic value independent of the other known clinical variables (7). Downstream members of the RAS/RAF/MEK pathway are rarely mutated in MDS. BRAF mutations are found in <1% of cases with clinical implications that are likely similar to those of NRAS mutations (7, 100).

CBL

CBL encodes a multidomain adaptor protein with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity that negatively regulates RTK signaling by modulating receptor degradation. CBL mutations have been identified in up to 15% of both CMML and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, but less than 3% of MDS and AML (7, 101). CBL mutations are mutually exclusive of other recurrent mutations in signaling pathway components, including FLT3, KIT, NRAS/KRAS/BRAF, and JAK2 (7, 102). Although rare in MDS and AML, they are associated with core binding factor abnormalities, t(8;21) and inv(16) (102).

The majority of CBL mutations affect the linker region between the tyrosine kinase-binding domain and the RING finger domain, resulting in reduced E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (103). Mutations are frequently biallelic and are associated with acquired UPD11q, suggesting tumor suppressor activity of the wild-type CBL allele (104). Further, the most common CBL mutations possess dominant-negative properties, as they have been shown to inhibit the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of wild-type CBL and its paralog CBL-B, and to enhance cellular sensitivity to cytokines and growth factors (TPO, SCF, FLT3-L, and IL-3) (103). This mechanism appears to underlie the myeloproliferative phenotype of Cbl-deficient mice, which is dependent on the presence of exogenous FLT3-ligand.

JAK2

Activating mutations in JAK2, most commonly V617F, occur rarely in MDS, and more commonly in MPNs, including polycythemia vera (>95%), essential thrombocythemia (50%), and myelofibrosis (60%). The clinical phenotype of these mutations is mediated by exaggerated activation of signaling pathways otherwise regulated by hematopoietic growth factors, including erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and G-CSF. Among cases of refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis (RARS-T), approximately 50% possess the JAK2V617F mutation (105) and 70% harbor SF3B1 mutations (8). The presence of concurrent JAK2V617F and SF3B1 mutations, causing myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic features, respectively, thus provides a plausible genetic basis for the composite MDS/MPN overlap phenotype of RARS-T.

Other genes involved in kinase signaling

Mutations in other genes involved in signal transduction pathways occur at low frequency in MDS. PTPN11, which encodes the SHP2 protein tyrosine phosphatase that regulates growth factor-dependent proliferation and differentiation in hematopoietic progenitors, is mutated in 10–15% of JMML and in <1% of MDS (7, 106). Reduced SHP2 expression in CD34+ progenitors promotes proliferation and impairs myeloid and erythroid differentiation (107). Rare somatic mutations in GNAS also occur in MDS (<1%) (7). GNAS encodes the Gsα subunit of a heterotrimeric G-protein coupled receptor and mutations in this gene have been associated with alteration of JAK/STAT signaling and implicated in non-hematopoietic malignancies (108).

CYTOGENETICS

Acquired cytogenetic abnormalities are reported in approximately 40–50% of de novo MDS (2, 3, 5). Disease karyotype is useful for the diagnosis of MDS as a marker of clonality, and is also a powerful predictor of overall and leukemia-free survival that is incorporated into the IPSS score. The specific genes within cytogenetic lesions that contribute to disease pathophysiology have been challenging to identify, but the genetic dissection del(5q) has begun to elucidate the molecular consequences of this heterozygous chromosomal deletion.

Del(5q)

Interstitial deletions of the long arm of chromosome 5 (5q) are the most common chromosomal abnormalities in MDS, identified in 10–15% of patients (3, 90). Patients with del(5q) MDS are clinically heterogeneous, falling into two broad categories based on clinicopathologic features, prognosis, and response to specific therapy. While 5q deletions are uniformly hemizygous, sequencing and CGH analysis have failed to reveal point mutations or microdeletions of the retained 5q alleles (109), nor has copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity been identified at 5q (4, 110). The absence of homozygous genetic inactivation of genes within the 5q common deleted regions (CDRs) suggests that the pathogenesis of MDS with hemizygous 5q deletion may be caused by haploinsufficiency or by silencing of classical tumor suppressors by epigenetic mechanisms.

Some patients with del(5q) display an aggressive disease course marked by increased risk of transformation to acute leukemia and a relatively short overall survival (111). This MDS subtype commonly arises in the context of prior therapy with alkylating agents and/or radiation and is often accompanied by additional cytogenetic abnormalities and TP53 mutation (74, 112). Indeed, patients with del(5q) in the context of multiple other karyotype abnormalities demonstrate a substantially lower likelihood of complete response to lenalidomide therapy compared to those with isolated del(5q) (3% vs. 67%) (113). Beyond chromosomal complexity, factors associated with adverse prognosis include deletion of extreme telomeric and centromeric regions of 5q or heterozygous mutations in the 5q35 genes NPM1 or MAML1 (114). A role for hemizygous deletion or mutation of NPM1 in MDS pathogenesis is suggested by a mouse model, where it functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in the development of multilineage hematopoietic neoplasms (115).

Patients with del(5q) as their sole karyotypic abnormality have a relatively favorable prognosis (5). Included among this lower risk subset are patients with the 5q- syndrome. This syndrome was initially described as a clonal hematopoietic disorder characterized by macrocytic anemia, normal or elevated platelet count, hypolobated micromegakaryocytes, and an isolated del(5q) on initial diagnostic evaluation (116). Bona fide 5q- syndrome has a low bone marrow blast percentage (< 5%), a 2:1 female to male ratio, and a relatively low risk of transformation to AML compared to other MDS (5–16% vs. 30–45%).

A region spanning 1.5 Mb at 5q32-q33 was defined as the CDR for the 5q- syndrome (117). A subset of genes within this region are expressed at haploinsufficient levels in CD34+ cells of patients with del(5q) (118). Systematic functional screening of all candidate genes within the 5q33 CDR provided the first evidence for the importance of haploinsufficient gene expression in the pathogenesis of 5q- MDS (119). Ribosomal protein S14 (RPS14) haploinsufficiency appears to be principally responsible for the characteristic erythroid phenotype of the 5q- syndrome (119). Reduced expression of RPS14 causes selective impairment of erythropoiesis with relative preservation of megakaryopoiesis. Forced expression of RPS14 in hematopoietic progenitors purified from patients with the 5q- syndrome rescues their erythropoietic defect.

RPS14 encodes a core ribosomal protein important for 18S pre-rRNA processing and 40S ribosomal subunit formation. Inherited heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in at least 10 different ribosomal protein genes, including RPS19 and RPS24, cause Diamond-Blackfan Anemia (DBA), a rare congenital syndrome characterized by hypoplastic anemia and severe macrocytosis (120). In both DBA and del(5q) MDS, haploinsufficiency of ribosomal genes impairs pre-rRNA processing, impairs ribosome biogenesis, and activates the p53 pathway (121, 122). Indeed, erythroid precursors display selective induction of p53, activation of p53 target gene expression, and cell cycle arrest (122). Pharmacologic or genetic inactivation of p53 rescues the progenitor defect in mouse models of the 5q- syndrome (122, 123), demonstrating the mechanistic importance of p53 induction in the setting of ribosomal protein haploinsufficiency.

Analysis of the repertoire of noncoding RNA species in bone marrow from MDS patients identified several microRNA (miRNA) with dysregulated expression. Two in particular, miR-145 and miR-146a, are abundantly expressed in normal hematopoietic progenitor populations, show specifically reduced expression in del(5q) MDS, and are localized to chromosome 5q. Depletion of both miR-145 and miR-146a in murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) results in thrombocytosis with megakaryocyte dysplasia mediated in part by up-regulation of miR-145/146a targets TIRAP and TRAF6 and consequent IL-6 secretion (124). Further analysis suggests that mir-145 normally acts via repression of the transcription factor FLI1 to regulate megakaryocyte and erythroid differentiation. Coordinate loss of miR-145 and RPS14 in CD34+ progenitors results in preferential megakaryocyte differentiation, reduced erythroid colony formation, and HSPC expansion, recapitulating key features of the 5q- syndrome. Consistent with this mechanism, patients with del(5q) MDS and decreased miR-145 levels show reciprocally increased expression of FLI1. Forced re-expression of miR-145 in CD34+ cells purified from MDS patients promoted normalization of megakaryocyte/erythroid colony ratio exclusively in cells from patients with hemizygous del(5q), but not in those with 5q diploid karyotype (125).

Current evidence suggests that the clinical phenotype of the 5q- syndrome represents the composite effects of multiple genes within the 5q33 CDR. Most patients, however, harbor deletions of substantially larger regions of chromosome 5q. As such, other genes localized to 5q outside the CDRs likely contribute to the clinical and phenotypic heterogeneity of patients with del(5q). APC, located on 5q23 and deleted in the vast majority of del(5q) MDS, encodes a negative regulator of β-catenin signaling. Mouse models demonstrate that heterozygous inactivation of Apc results in decreased stem cell activity in secondary transplants and a myeloproliferative/MDS phenotype (126).

Lenalidomide is now approved by the FDA for the treatment of low risk MDS with del(5q). Among these patients, lenalidomide induces cytogenetic complete response in 50–60% of patients, with 55–70% achieving transfusion-independence (127, 128). Even in patients with a complete cytogenetic remission, however, the del(5q) clone persists in CD34+CD38−CD90+ stem cells that likely mediate eventual disease progression (129). The presence of rare disease subclones with TP53 mutations in pretreatment biopsies is associated with relative resistance to lenalidomide and may predict reduced duration of treatment response (112, 130).

−7; del(7q)

Chromosome 7 abnormalities, monosomy 7 or interstitial deletion of 7q, are present in approximately 10% of de novo MDS and nearly 50% of MDS arising after exposure to alkylating agents (3, 131). When present as sole abnormalities, chromosome 7 lesions are associated with reduced overall survival compared to normal karyotype. Isolated monosomy 7 is associated with worse prognostic features than interstitial del(7q) (2). Commonly deleted regions at 7q22 and 7q32-34 have been delineated in an attempt to identify key tumor suppressor genes (132). A murine model with conditional deletion of the 7q22 CDR in the hematopoietic system did not have a hematopoietic phenotype (133), Homozygous deletion of MLL5, a histone lysine methyltransferase localized within the 7q22 CDR, results in altered hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis and impaired repopulating capacity (134). While somatic mutations in MLL5 have not been identified in myeloid neoplasms, reduced expression of MLL5 is independently associated with adverse prognosis in AML. EZH2 is localized to 7q36, and EZH2 mutations can occur in the setting of 7q uniparental disomy. Deletions of 7q and some cases of acquired UPD7q, however, are not associated with EZH2 mutations or do not include the EZH2 gene, indicating that one or more additional 7q genes are likely to be important drivers of MDS (59).

+8

Trisomy 8 is present as the sole cytogenetic abnormality in approximately 5% of MDS and is associated with intermediate prognostic risk with median overall survival of 23 months (3, 135). Gain of chromosome 8 appears to represent a late event in MDS pathogenesis, occurring in myeloid-restricted progenitors and not readily detectable in the CD34+ CD38− CD90+ stem cell compartment thought to contain the disease-initiating clone (136). Hematopoietic progenitors harboring +8 express higher levels of antiapoptotic genes and are resistant to experimental apoptotic stimuli, suggesting a possible mechanism of clonal advantage (137). Patients with trisomy 8 MDS often possess an oligoclonal expansion of CD8+ T cells reactive to aneuploid HSPCs and display an increased rate of hematologic response to immunosuppressive therapy (138). Patients with trisomy 8 MDS who respond to immunosuppressive therapy have further been demonstrated to overexpress Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) and generate a T cell anti-tumor response against WT1 epitopes (139).

3q, i(17q)

Abnormalities involving chromosome 3q, including inversions, translocations, and deletions, are identified rarely in MDS, but are now integrated into the latest cytogenetic scoring system as “poor risk” due to their association with short overall survival (2, 3). t(3q) and inv(3q) usually involve the MDS1 and EVI1 locus (MECOM) at 3q26 and result in increased expression of EVI1, which causes increased proliferation and impaired differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (140). In a mouse model, overexpression of the EVI1 transcription factor causes an MDS phenotype (141), at least in part by interfering with the function of the core hematopoietic transcription factors RUNX1, GATA1 and PU.1 (90).

The isochromosome 17q abnormality confers intermediate cytogenetic risk and is associated with a distinctive myeloproliferative/myelodysplastic phenotype with severe anemia, leukocytosis with pseudo Pelger-Huet neutrophils, and a hypercellular bone marrow with micromegakaryocytic hyperplasia (142, 143). While i(17q) is associated with loss of one TP53 allele, the remaining TP53 allele is uniformly unmutated, suggesting a role for additional genes on chromosome 17 (143).

Del(20q), del(12p), del(11q), -Y, i(17q)

Patients with isolated del(20q) and del(12p) are considered to be in the same “good” cytogenetic risk group as those with normal karyotype, with median overall survival of 5–6 years and 6–9 years, respectively. Isolated –Y and del(11q) fall within the most favorable “very good” risk group and are associated with prolonged overall and leukemia-free survival (2, 3). Among these, del(20q) has been most intensely studied, but within the CDR, no gene has been conclusively linked with MDS pathogenesis. The ASXL1 gene, mutated in 10–20% of MDS, is localized to chromosome 20q11 but falls just outside the del(20q) CDR. L3MBTL1, located within the CDR at 20q13, encodes a polycomb protein and has been implicated in genomic instability (144). The ETV6 gene, located at 12p13, and the CBL gene, located at 11q23 are recurrently mutated in MDS and lie within regions that are deleted in some cases of MDS (102, 145).

CONCLUSION

The clinical heterogeneity of MDS reflects the diversity of molecular abnormalities that drive disease pathogenesis. Technological developments have enabled the identification of many new genetic lesions in MDS patients, providing profound insights into disease pathogenesis. The full impact of genetics on MDS, however, has not yet been fully realized. Molecular factors may soon be integrated into diagnostic criteria and clinical management algorithms, as specific mutations are shown to distinguish disease subtypes and provide prognostic information not captured by current risk assessment models. For each individual patient, prognosis and therapeutic response will depend not only on features of a readily identified dominant clone, but also on those of distinct genetic clones that co-exist in the bone marrow.

At present, the diagnosis of MDS relies heavily on accurate assessment of the presence and extent of morphologic dysplasia in the bone marrow. The range of dysplastic features is wide and no unifying finding is present in the majority of cases (146). Interobserver agreement regarding dyshematopoietic features is at times problematic and many patients lack the most distinctive pathologic features, such as ring sideroblasts or an excess of myeloid blasts (147). While morphologic evaluation remains the backbone of diagnostic pathology, the presence of characteristic mutations may clarify the diagnosis of MDS in a patient with refractory cytopenias and borderline morphologic features. Further, sensitive molecular testing of the peripheral blood might prove useful diagnostically, or as a means to monitor response to therapy, without the need for a bone marrow biopsy.

Clinical management of MDS depends critically on the reliable ascertainment of disease prognosis. While minimally symptomatic patients with low-risk disease may be observed expectantly, patients with higher risk disease are treated with disease-modifying medical therapies or with allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which remains the only potentially curative treatment. Optimal timing of transplant requires the balancing of disease-specific prognosis and the risk of transplant-related morbidity and mortality.

MDS classification schemes and risk models are likely to be improved with the inclusion of genetic variables, and ultimately reconfigured into subtypes with a common molecular basis and a more consistent clinical phenotype. With the identification of the full suite of mutations that are recurrently mutated in MDS, insights into disease biology and improved animal models will hopefully accelerate the development of new therapeutic agents. In the future, clinical variables, pathologic features, and genetic information will be integrated for prospective risk stratification and the choice of specific therapies for the treatment of MDS.

Central Points.

Myelodysplastic syndromes are a clinically heterogeneous collection of clonal myeloid neoplasms whose pathogenesis is driven by diverse, somatically acquired genetic abnormalities.

The current diagnosis and classification of MDS rely on accurate assessment of the presence and extent of morphologic dysplasia in the bone marrow. As molecular abnormalities are characterized more fully, genetic variables will be integrated into disease classification schemes and risk models.

Chromosomal abnormalities are present in approximately 50% of de novo MDS; metaphase cytogenetic analysis is the only genetic test currently in routine clinical use. Nineteen distinct cytogenetic categories classifying five prognostic subgroups have been defined.

Somatic point mutations can be identified in over 70% of MDS cases, including the majority of cases with a normal karyotype.

Point mutations are powerful predictors of clinical phenotype, and predict prognosis independent of existing clinical variables.

Among myeloid neoplasms with morphologic dysplasia, mutations in genes encoding components of the RNA splicing machinery are frequently identified and are mutually exclusive.

Mutations affecting epigenetic regulation of gene expression, including DNA methylation and post-translational histone modification, are common in MDS.

Acquired TP53 mutations are associated with a consistent phenotype, including a poor prognosis independent of established clinicopathologic variables, complex karyotype, high bone marrow blast percentage, and thrombocytopenia.

Abbreviations

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- MPN

myeloproliferative neoplasm

- IPSS

International Prognostic Scoring System

- snRNP

small nuclear ribonucleoproteins

- 5mC

5-methylcytosine

- 5hmC

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- 2HG

2-hydroxyglutarate

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- CDR

common deleted region

Glossary

- Pre-mRNA splicing

the process by which pre-mRNAs are converted to mature mRNA by excision of non-coding sequences (introns) and joining of coding sequences (exons)

- Small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNP)

RNA-protein complexes comprising part of the spliceosome and important for catalyzing pre-mRNA processing

- Epigenetic regulators

factors that influence cellular phenotype without affecting the primary nucleotide sequence, often via effects on local transcriptional potential

- Acquired uniparental disomy (also copy neutral loss of heterozygosity)

acquired homozygosity, often associated with duplication of mutations in tumor suppressors or oncogenes and loss of the normal allele

- Ring sideroblast

on iron staining of bone marrow aspirate smear, erythroid precursors containing ≥ 5 iron granules around > 1/3 of the nucleus

Literature Cited

- 1.Brunning R, Orazi A, Germing U, Le Beau M, Porwit A, Baumann I, Vardiman J, Hellstrom-Lindberg E. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. Myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms, overview; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schanz J, Tüchler H, Solé F, Mallo M, Luño E, Cervera J, Granada I, et al. New Comprehensive Cytogenetic Scoring System for Primary Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) and Oligoblastic Acute Myeloid Leukemia After MDS Derived From an International Database Merge. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(8):820–829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6394. A large analysis of chromosomal abnormalities in MDS that defines nineteen distinct cytogenetic categories classifying five prognostic subgroups. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haase D, Germing U, Schanz J, Pfeilstöcker M, Nösslinger T, Hildebrandt B, Kundgen A, et al. New insights into the prognostic impact of the karyotype in MDS and correlation with subtypes: evidence from a core dataset of 2124 patients. Blood. 2007;110(13):4385–4395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gondek LP, Tiu R, O’Keefe CL, Sekeres MA, Theil KS, Maciejewski JP. Chromosomal lesions and uniparental disomy detected by SNP arrays in MDS, MDS/MPD, and MDS-derived AML. Blood. 2008;111(3):1534–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, Sanz M, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89(6):2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, Nowak D, Nagata Y, Yamamoto R, Sato Y, et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478(7367):64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature10496. Reports spectrum of mutations affecting RNA splicing machinery in MDS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. Somatic point mutations (TP53, EZH2, ETV6, RUNX1, ASXL1) predict poor prognosis in MDS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey BA, Abdel-Wahab O, Steensma DP, et al. Validation of a prognostic model and the impact of mutations in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7379 [epub ahead of print on August 6, 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, Malcovati L, Vyas P, Bowen D, Pellagatti A, et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1384–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103283. SF3B1 mutations are strongly associated with the ring sideroblasts morphology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacher U, Haferlach T, Schnittger S, Kreipe H, Kröger N. Recent advances in diagnosis, molecular pathology and therapy of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graubert TA, Shen D, Ding L, Okeyo-Owuor T, Lunn CL, Shao J, Krysiak K, et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(1):53–57. doi: 10.1038/ng.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40(12):1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456(7221):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David CJ, Manley JL. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulation in cancer: pathways and programs unhinged. Genes & Development. 2010;24(21):2343–2364. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Will CL, Lührmann R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(7) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malcovati L, Papaemmanuil E, Bowen DT, Boultwood J, Porta Della MG, Pascutto C, Travaglino E, et al. Clinical significance of SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011;118(24):6239–6246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damm F, Thol F, Kosmider O, Kade S, Löffeld P, Dreyfus F, Stamatoullas-Bastard A, et al. SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: clinical associations and prognostic implications. Leukemia. 2011 doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Hodnefield JM, Knudson RA, Ketterling RP, Garcia-Manero G, Steensma DP, Pardanani A, Hanson CA, Tefferi A. SF3B1 mutations are prevalent in myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts but do not hold independent prognostic value. Blood. 2012;119(2):569–572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maratheftis CI, Bolaraki PE, Giannouli S, Kapsogeorgou EK, Moutsopoulos HM, Voulgarelis M. Aberrant alternative splicing of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) in myelodysplastic hematopoietic progenitor cells. Leuk Res. 2006;30(9):1177–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caudill JS, Porcher JC, Steensma DP. Aberrant pre-mRNA splicing of a highly conserved cell cycle regulator, CDC25C, in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(5):989–993. doi: 10.1080/10428190801971690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isono K, Mizutani-Koseki Y, Komori T, Schmidt-Zachmann MS, Koseki H. Mammalian polycomb-mediated repression of Hox genes requires the essential spliceosomal protein Sf3b1. Genes & Development. 2005;19(5):536–541. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, Lee J-H, LeProust EM, Park I-H, Xie B, Daley GQ, Church GM. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(4):361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454(7205):766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C, Zhang Y. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300– 1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figueroa ME, Skrabanek L, Li Y, Jiemjit A, Fandy TE, Paietta E, Fernandez H, et al. MDS and secondary AML display unique patterns and abundance of aberrant DNA methylation. Blood. 2009;114(16):3448–3458. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Y, Dunbar A, Gondek LP, Mohan S, Rataul M, O’Keefe C, Sekeres M, Saunthararajah Y, Maciejewski JP. Aberrant DNA methylation is a dominant mechanism in MDS progression to AML. Blood. 2009;113(6):1315–1325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L, Kantarjian H, Guo Y, Lin E, Shan J, Huang X, Berry D, et al. DNA Methylation Predicts Survival and Response to Therapy in Patients With Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(4):605–613. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, Kornblith AB, Holland JC, Odchimar-Reissig R, Stone RM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellström-Lindberg E, Santini V, Finelli C, Giagounidis A, Schoch R, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, et al. DNMT3AMutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walter MJ, Ding L, Shen D, Shao J, Grillot M, McLellan M, Fulton R, et al. Recurrent DNMT3A mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2011;25(7):1153–1158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thol F, Winschel C, Ludeking A, Yun H, Friesen I, Damm F, Wagner K, Krauter J, Heuser M, Ganser A. Rare occurrence of DNMT3A mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2011;96(12):1870–1873. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.045559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Wahab O, Pardanani A, Rampal R, Lasho TL, Levine RL, Tefferi A. DNMT3A mutational analysis in primary myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and advanced phases of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2011;25(7):1219–1220. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan X-J, Xu J, Gu Z-H, Pan C-M, Lu G, Shen Y, Shi J-Y, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(4):309–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Challen GA, Sun D, Jeong M, Luo M, Jelinek J, Berg JS, Bock C, et al. Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 2012;44(1):23–31. doi: 10.1038/ng.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langemeijer SMC, Kuiper RP, Berends M, Knops R, Aslanyan MG, Massop M, Stevens-Linders E, et al. Acquired mutations in TET2 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):838–842. doi: 10.1038/ng.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Valle Della V, James C, Trannoy S, Masse A, Kosmider O, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. Mutations in TET2 are common in myeloid neoplasms and present in hematopoietic stem cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Klein H-U, Schindela S, Weiss T, Kazak B, Dicker F, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology reveals a characteristic pattern of molecular mutations in 72.8% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by detecting frequent alterations in TET2, CBL, RAS, and RUNX1. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(24):3858–3865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdel-Wahab O, Mullally A, Hedvat C, Garcia-Manero G, Patel J, Wadleigh M, Malinge S, et al. Genetic characterization of TET1, TET2, and TET3 alterations in myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114(1):144–147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metzeler KH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Margeson D, Becker H, Curfman J, et al. TET2 mutations improve the new European LeukemiaNet risk classification of acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(10):1373–1381. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, Li Y, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kosmider O, Gelsi-Boyer V, Cheok M, Grabar S, Valle Della V, Picard F, Viguié F, et al. TET2 mutation is an independent favorable prognostic factor in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) Blood. 2009;114(15):3285–3291. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AE, Mohamedali AM, Kulasekararaj A, Lim Z, Gäken J, Lea NC, Przychodzen B, et al. Next-generation sequencing of the TET2 gene in 355 MDS and CMML patients reveals low-abundance mutant clones with early origins, but indicates no definite prognostic value. Blood. 2010;116(19):3923–3932. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]