Abstract

Background

The presence of a large cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) has been previously associated with antisocial behavior/psychopathic traits in an adult community sample.

Aims

The current study investigated the relationship between a large CSP and symptom severity in disruptive behavior disorders (DBD; Conduct Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder).

Method

Structural MRI scans of youth with DBDs (N=32) and healthy comparison youth (N=27) were examined for the presence of a large CSP and if this was related to symptom severity.

Results

Replicating previous results, a large CSP was associated with DBD diagnosis, proactive aggression and level of psychopathic traits in youth. However, the presence of a large CSP was unrelated to aggression or psychopathic traits within the DBD sample.

Conclusions

Early brain mal-development may increase the risk of a DBD diagnosis but does not mark a particularly severe form of DBD within patients receiving these diagnoses.

There is a growing literature indicating that many patients with disruptive behavior disorders (DBD), including Conduct Disorder (CD) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), show neurobiological abnormalities (Blair, 2010). This may be particularly the case for those youth showing psychopathic traits (PT); i.e., callous-unemotionality (e.g., lack of guilt and empathy), narcissism (e.g., brags excessively about abilities) and impulsivity (e.g., acts without thinking; Barry et al., 2000). Functional MRI studies support the suggestion of amygdala, caudate and ventromedial prefrontal cortex dysfunction in this population (Finger et al., 2011; Finger et al., 2008; Jones, Laurens, Herba, Barker, & Viding, 2009; Marsh et al., 2008; Passamonti et al., 2010; White et al., in press). However, no previous work has assessed whether this population might show a structural brain abnormality reflective of early neural mal-development.

Interestingly, recent work by Raine and colleagues examined whether adults with a large cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) would show higher levels of psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder (Raine, Lee, Yang, & Colletti, 2010). A large CSP is a marker of abnormal brain development, particularly in regards to midline structures (Bodensteiner & Schaefer, 1990; Sarwar, 1989). The septum pellucidum is one component of the septum. It consists of a deep, midline, limbic structure made up of two translucent leaves of glia separating the lateral ventricles and forms part of the septohippocampal system. A second component of the septum, the septum verum, contains the septal nuclei. At approximately the twelfth week of gestation, a space forms between the two laminae: the CSP. This space begins to close at approximately the twentieth week of gestation and finishes closing shortly after birth (3–6 months postnatally (Sarwar, 1989). The rapid development of the alvei of the amygdala, hippocampus, septal nuclei, fornix, corpus callosum and other midline structures is attributed to fusion of the CSP (Kim et al., 2007; Nopoulos, Krie, & Andreasen, 2000). Disruption in the development of these limbic structures interrupts this posterior-to-anterior fusion and leads to the preservation of the CSP (see Figure 1). The presence of a large CSP is associated with an increased risk of several disorders including post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; May et al., 2004), schizophrenia (Nopoulos, Krie, et al., 2000) and bipolar disorder (Kim et al., 2007). Additionally, Raine and colleagues reported that adults with a large CSP had significantly higher levels of antisocial personality, psychopathy, arrests and convictions relative to those without a large CSP (Raine et al., 2010).

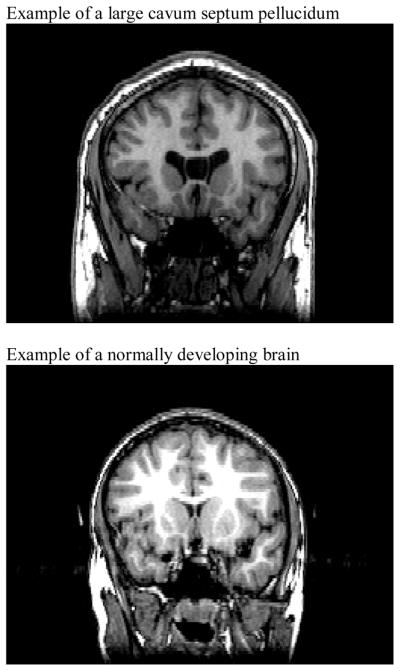

Figure 1.

Coronal images of a Large Cavum Septum Pellucidum and a Normally Developing Brain

The goal of the current study was to examine the relationship between the presence of a large CSP and psychopathic traits/antisocial behavior in youth and to address a limitation of Raine and colleagues study. Namely, it was unclear whether a large CSP was specifically related to psychopathic traits or if a large CSP was simply associated with elevated levels of antisocial behavior, but not specifically psychopathic traits. We therefore made three predictions for the current study. First, we expected to replicate the Raine et al findings indicating a greater likelihood of CSP in youth diagnosed with DBD. Second, we hypothesized that given the greater severity of youth with CD relative to ODD (Burke, Waldman, & Lahey, 2010), youth with a large CSP would be more likely to be diagnosed with CD relative to ODD. Third, we predicted that DBD youth with a large CSP would show significantly higher levels of psychopathic traits and aggression than all other youth.

Method

Participants

The study sample was comprised of 59 adolescents: 32 youths with DBD and 27 healthy comparison youths (Table 1). Youths were recruited through newspaper ads, fliers, and referrals from area mental health practitioners. Informed assent and consent was obtained from participating children and parents. This study was approved by the NIMH IRB.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Youth with DBD and Healthy Controls

| Characteristic | Youth with DBD (N=32) | Healthy Controls (N=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 14.90 (2.08) | 14.38 (2.44) |

| IQa | 95.47 (11.11) | 100.33 (10.65) |

| Measures | ||

| APSD** | 27.41 (6.06) | 6.59 (5.70) |

| ICU (combined)** | 41.78 (13.08) | 17.88 (10.05) |

| Reactive Agg.** | 3.93 (1.91) | 0.84 (0.80) |

| Proactive Agg.** | 2.60 (1.63) | 0.04 (0.20) |

| N % | N % | |

|

|

||

| Gender | 25 male (78%) | 19 male (59%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 20 (63%) | 9 (28%) |

| European American | 9 (28%) | 11 (44%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

| Mixed | 3 (9%) | 5 (16%) |

SD = Standard Deviation

Assessed with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (two-subtest form)

significantly different at p< .05

significantly different at p< .001

All youths and parents completed Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS; Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, & et al., 1997) assessments conducted by a doctoral-level clinician as part of a comprehensive psychiatric and psychological assessment. The K-SADS has demonstrated good validity and inter-rater reliability (kappa >0.75 for all diagnoses; Kaufman et al., 1997). IQ was assessed with the Wechsler Abbrieviated Scale of Intelligence (two-subtest form). Stringent exclusion were implemented to minimize the influence of potential confounds. Exclusion criteria were the presence of pervasive developmental disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, lifetime history of psychosis, depression, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social or separation anxiety disorder, PTSD, neurological disorder, history of head trauma, history of substance dependence, and IQ<70. Two youth with DBD met criteria for substance abuse (both with CD diagnoses). In addition, parents and children completed an assessment battery, which included the Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits (Frick, 2004) and parents completed the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick & Hare, 2001) and a Proactive/Reactive Aggression scale (Dodge & Coie, 1987). Parent and child ratings on the ICU were combined in a manner suggested by the author (Frick, 2004), which has shown improved predictive validity relative to single reporter ratings in adolescents (White, Cruise, & Frick, 2009). The groups did not differ significantly on IQ, age, race/ethnicity or gender (see Table 1). As would be expected, the DBD group had significantly higher APSD, ICU, Reactive Aggression, and Proactive Aggression scores than the healthy control group (Table 1).

Clinical Measures

Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, 2004)

The ICU is a 24-item self-report scale designed to assess callous and unemotional traits in youth. The ICU was derived from the callous-unemotional (CU) scale of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick & Hare, 2001) that has been widely used in various samples of youth. The construct validity of the ICU has been supported in community and juvenile justice samples (Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006; Kimonis et al., 2008; Lawing, Frick, & Cruise, 2010). The ICU has adequate internal consistency (Cronach’s α = .77; Essau et al., 2006)

Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick & Hare, 2001)

The APSD is a 20-item parent-completed rating of callous-unemotional traits and conduct and impulsivity problems (Frick & Hare, 2001), designed to detect psychopathic traits in youth. A three-factor structure has been characterized and comprises the following dimensions: callous-unemotional, narcissism, and impulsivity (Frick & Hare, 2001). There is no established cutoff score for classification of a high level of psychopathic traits (Frick & Hare, 2001). Adequate Cronbach’s alphas for the APSD have been established (α’s > .7; Frick & Hare, 2001).

Reactive/Proactive Rating Scale

These six items were taken from a rating scale developed by Dodge and Coie (Dodge & Coie, 1987). Dodge and Coie found a 3 item reactive aggression scale and a 3 item that proactive aggression scale yielded the best fitting model (Dodge & Coie, 1987) and were found to be useful in distinguishing aggression sub-types in children (Dodge & Coie, 1987) and adolescents (Pellegrini & Bartini, 2001). Coefficient alphas scale have been reported at .91 and .90 for the proactive and reactive aggression scales respectively (Dodge & Coie, 1987).

MRI parameters

Anatomical MRI data was acquired for 51 participants (19 healthy comparison; 32 DBD youth) using a 1.5-T GE Signa and for 8 (8 healthy comparison youth) using a 3.0 MRI scanner. A high-resolution T1-weighed anatomical image was acquired covering the whole brain (3-dimensional spoiled gradient recalled acquisition in a steady state; 1.5-T: repetition time=9 milliseconds; echo time=2.872 milliseconds; 24 cm field of view; 20° flip angle; 128 axial slices; thickness, 1.5 mm; 256×192 matrix; 3.0-T: repetition time=7 milliseconds; echo time=2.984 milliseconds; 24 cm field of view; 12° flip angle; 128 axial slices; thickness, 1.2 mm; 256×192 matrix).

CSP assessment

Following previous work (Raine et al., 2010), anatomical boundaries for CSP were as follows: the genu of the corpus callosum defined the anterior boundary, the body of the corpus callosum defined the superior boundary, the rostrum of the corpus callosum and fornix defined the inferior boundary, and the junction of the splenium of the corpus callosum with the crus of the fornix defined the posterior boundary. The number of coronal 1 mm slices on which the CSP was present was recorded. Following previous work (Rajarethinam, Sohi, Arfken, & Keshavan, 2008), presence of a large CSP was defined as a CSP of 4 mm or greater length. Assessment was performed in the anterior-to-posterior direction in the coronal view, using a simultaneous sagittal view to ensure that consistent anatomical boundaries were maintained. Assessment was conducted by 2 independent raters masked to all other participant data. Inter-rater reliability was high [ICC = 1.000, r = .96]. A coronal illustration of CSP is provided in Figure 1.

Statistical analyses

To test our first prediction, that DBD youth would be more likely to have a large CSP, we conducted a Chi-square analysis comparing the proportion of youth with a large CSP in the DBD group and the healthy comparison group. This prediction would be supported if a significantly greater proportion of the DBD youth were found to have a large CSP relative to the healthy comparison group. To test our second predication, that a large CSP would increase the likelihood of CD relative to ODD diagnoses, we conducted a Chi-square analysis comparing the proportion of DBD youth with CD diagnoses relative to ODD diagnoses in the groups with and without a large CSP. This prediction would be supported if a significantly greater proportion of the DBD youth with a large CSP had diagnoses of CD relative to ODD. To test our third prediction, that DBD youth with a large CSP would show significantly higher rates of psychopathic traits and aggression than DBD youth without a large CSP, we conducted a series of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Our third prediction would be supported if DBD youth with a large CSP were found to have significantly higher levels of psychopathic traits and aggression relative both to healthy individuals and to DBD youth without a large CSP. All analyses, including post-hoc t-tests, were conducted using SPSS 19.

Results

Group differences in incidence of large CSP

To test our first prediction, that DBD would be more likely to have a large CSP, we conducted a Chi-square analysis comparing the proportion of youth with a large CSP in the DBD group and the healthy comparison group. This revealed a significant group difference in incidence of a large CSP [χ2(1, N = 59) = 6.70, p = 0.01]. Indeed, a large CSP was only observed in the patients with DBD (7/32, 22%) and was not seen in the healthy comparison youth. Our second hypothesis, however, was not supported, as the incidence of large CSP was not related to the probability that the participant received a diagnosis of ODD relative to CD (3/11 patients with ODD showed a large CSP, 4/21 patients with CD) [χ2(1, N = 32) = .286, p = .59].

Relationship of CSP with psychopathic traits and aggression

A series of ANOVAs comparing healthy comparison youth, DBD youth without a large CSP and DBD youth with a large CSP were conducted to test our third prediction. Significant main effects for group were observed for the APSD and its subscales, the ICU and both proactive and reactive aggression (see Table 2). A series of post-hoc t-tests revealed for all the ANOVAs that while the youth with DBD and a large CSP did have significantly greater levels of psychopathic traits and aggression relative to healthy youth [t’s ranging from 5.87 to 12.98, p’s <.001], they did not show significantly higher levels of psychopathic traits and aggression relative to DBD youth without a large CSP [t’s ranging from .10–1.28, p’s > .2]. There is a lack of statistical power in these analyses due to the small number of youth with a large CSP. However, it is important to note that the effect sizes seen here were small. Power analysis, using these effect sizes (partial η2 ranging from .001–.056) indicated samples of between 421 and 24,365 youth would be needed for an adequately powered analysis.

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance to Estimate the Impact of DBD and CSP on Psychopathic Traits and Aggression

| Dependent Variable | HC (N=27) | DBD− (N= 25) | DBD+ (N= 7) | F(df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| APSD | 6.59ab (5.7) | 27.28a (5.8) | 27.86b (7.5) | 89.63 | <.001 |

| CU | 1.85ab (2.0) | 7.60a (2.6) | 7.43b (2.7) | 44.72 | <.001 |

| IMP | 2.00ab (1.1) | 7.32a (2.3) | 8.00b (2.2) | 67.23 | <.001 |

| NAR | 1.44ab (1.8) | 9.44a (2.8) | 9.29b (3.6) | 72.97 | <.001 |

| ICU | 17.88ab (10.1) | 40.00a (14.4) | 46.83b (6.9) | 26.53 | <.001 |

| Reactive Aggression | .840ab (.8) | 3.91a (2.1) | 4.00b (1.4) | 28.00 | <.001 |

| Proactive Aggression | .040ab (.2) | 2.39a (1.6) | 3.29b (1.7) | 32.97 | <.001 |

Significantly different means denoted by common letter

HC= healthy comparison

DBD− = youth with disruptive behavior disorder without large cavum septum pellucidum DBD+ = youth with disruptive behavior disorder without large cavum septum pellucidum

SD= Standard Devation, df= degrees of freedom

APSD= Antisocial Process Screening Device, CU= APSD subscale Callous-Unemotional, NAR= APSD subscale Narcissism, IMP= APSD subscale Impulsivity

ICU= Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits

Potential confounds

Given the high rates of comorbidity between DBD and Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Hinshaw, 1987), the relationship between large CSP and ADHD was examined to ensure that ADHD was not confounding the results. A Chi-square analysis was conducted comparing the proportion of youth with and without a large CSP and incidence of ADHD diagnosis. There was no significant difference between the proportion of youth with an ADHD diagnosis presence of a large CSP and receipt of an ADHD diagnosis within the entire sample [χ2(1, N = 59) = 3.11, p= .08] or within the DBD group [χ2(1, N = 32) = .058, p= .81].

Discussion

Main findings

Youth with a large CSP were more likely to meet criteria for a DBD than youth without a large CSP. However, the presence of a large CSP was not higher amongst those with a more severe form of DBD (CD as opposed to ODD). Moreover, DBD youth with a large CSP did not show increased levels of aggression and psychopathic traits relative to other DBD youth.

Implications for developmental psychopathology

The current results support those of Raine et al.’s previous study with an adult community sample (Raine et al., 2010). That study reported that adults with a large CSP had significantly higher levels of antisocial personality, psychopathy, arrests and convictions relative to those without a large CSP (Raine et al., 2010). Similarly, we observed that individuals with a large CSP have a higher risk for aggressive behavior, psychopathic traits and being diagnosed ODD/CD. However, it should be noted that the presence of a large CSP was not associated with a more severe form of DBD (CD versus ODD).

Previous work has shown functional MRI impairments in DBD, particularly in the amygdala, caudate, ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (Crowe & Blair, 2008; Finger et al., 2011; Finger et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2009; Marsh et al., 2008; Passamonti et al., 2010; White et al., in press). Similarly, structural abnormalities in these and connected regions have been reported in youth with DBD and adults with psychopathy (De Brito et al., 2009; Glenn, Raine, Yaralian, & Yang, 2010; Yang, Raine, Narr, Colletti, & Toga, 2009). The current data suggest that at least some of these functional and structural abnormalities in some (but not all) youth with DBD may relate to relatively early abnormalities in brain development given that the CSP closes by 3–6 months of age (Sarwar, 1989).

Currently, the specific causes of large CSP are unclear. However, it has been associated with exposure to alcohol in the womb (Swayze et al., 1997) and the development of associated midline structures (e.g., the septum) is influenced by early malnutrition (Craciunescu, Johnson, & Zeisel, 2010; Mellott, Kowall, Lopez-Coviella, & Blusztajn, 2007). Moreover, there are indications of genetic influences on the probability of a large CSP (May, Chen, Gilbertson, Shenton, & Pitman, 2004). Notably, fetal exposure to alcohol and other narcotics (Streissguth et al., 2004; Wakschlag et al., 2010) as well as early malnutrition (Liu & Raine, 2006) have all been previously associated with an increased risk for aggression and there are genetic influences on the probability of aggression, at least in the context of callous-unemotional traits (Viding, Blair, Moffitt, & Plomin, 2005).

It is interesting in this context to note that while exposure to alcohol/other narcotics and early malnutrition have been associated with an increased risk for aggression, they have not been clearly associated yet with psychopathic or callous-unemotional traits in particular. The current data indicated that a large CSP was associated with an increased risk for presenting with a DBD, but there were no significant differences in psychopathic/callous-unemotional traits between DBD youth with and without a large CSP. Together these data suggest that a large CSP may indicate the presence of early developmental abnormalities, but that the form of these abnormalities may differ across individuals (or perhaps how these abnormalities interact with specific environmental circumstances). This conclusion follows from the growing literature that individuals with conduct problems associated with callous-unemotional traits show a different pathophysiology from those who present with conduct problems in the absence of such traits (Blair, 2010). Moreover, the presence of a large CSP is associated with an increased risk for a variety of disorders including post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; May et al., 2004), schizophrenia (Nopoulos, Krie, et al., 2000) and bipolar disorder (Kim et al., 2007). In short, while a large CSP is a marker of abnormal brain development, it does not appear to specifically indicate any one developmental trajectory given the different pathophysiologies associated with DBDs, PTSD, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Limitations of the current study

There are four limitations to the current study. First is the lack of a group of subjects presenting with ADHD in the absence of DBD. DBD and ADHD are highly co-morbid (Taylor, Schachar, Thorley, & Wieselberg, 1986). However, it should be noted that presence of a large CSP was not associated with an increased risk for ADHD in the present sample. Moreover, previous work has reported that patients with ADHD do not show an increased risk for a large CSP (Nopoulos, Berg, et al., 2000). Second, very strict exclusion criteria were applied to the current sample. While this is a strength of the study as potential confounds are eliminated regarding the pathophysiology of DBD, the current sample would be atypical in clinical settings. Given that a large CSP appears to be a risk factor for a variety of psychiatric conditions, it is possible that a large CSP may be particularly common in patients with significant co-morbidities. Third, the current study does not examine the relative impact of aggressive versus non-aggressive symptoms or covert versus overt aggression. Future work could examine the relationship between large CSP and various sub-types of aggression and antisocial behavior. Fourth, there were very few youth identified in the sample as having a large CSP, which may limit our ability to detect group differences. However, the effect sizes observed in the current analyses were very small (partial etas < .056), mitigating this limitation.

Clinical implications

In conclusion, the current results in a sample of youth with DBD replicate and qualify those of Raine and colleagues’ study with an adult sample (Raine et al., 2010). The current results support the Raine and colleagues suggestion that the presence of a large CSP is associated with increased risk for antisocial behavior and that at least some forms of antisocial behavior have a neurobiological basis. However, by finding no relationship of a large CSP with increased psychopathic traits generally or callous-unemotional traits within the DBD sample, the data qualify the Raine et al results and suggest that while a large CSP is a marker for abnormal brain development, it is not a marker for psychopathy or any other particularly severe variant of antisocial behavior.

This is particularly emphasized when considering that a heightened incidence of large CSP is also found in patients with different disorders such as PTSD (May et al., 2004), schizophrenia (Nopoulos, Krie, et al., 2000) and bipolar disorder (Kim et al., 2007). Given this, it is likely that a variety of different forms of early abnormal brain development may be associated with an increased risk for a large CSP. Alternatively, though, it is possible that there is a common form (or cause) of early brain mal-development that puts the individual at risk for a wide variety of psychiatric conditions and that other environmental or genetic factors determine which form develops. Indeed, it is notable, for example, that fetal exposure to alcohol and other narcotics not only increases the risk for aggression (Streissguth et al., 2004; Wakschlag et al., 2010) but also the risk for schizophrenia (Schlotz & Phillips, 2009).

Finally, it is important to note that a large CSP was only seen in a minority of the patients with DBD. This suggests that early atypical brain development, or at least that associated with a large CSP, is only associated with a fraction of patients with DBD. This supports previous claims of multiple developmental routes to an increased risk for antisocial behavior (Blair, 2010; P. J. Frick & White, 2008). Moreover, this emphasizes the importance of individualized treatment of patients with DBD.

Key Points.

The presence of a large cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) has been associated with antisocial behavior/psychopathic traits in an adult community sample.

This study investigated the relationship between a large CSP and symptom severity in disruptive behavior disorders (DBD; Conduct Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder).

Youth with a large CSP were more likely to meet criteria for a DBD than youth without a large CSP.

DBD youth with a large CSP did not show increased levels of aggression/psychopathic traits relative to other DBD youth.

Early brain mal-development may increase risk for a DBD diagnosis but does not mark a severe form of DBD within these patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research Programs and the National Institute of Mental Health/NIH.

Abbreviations

- CU

callous-unemotional

- CSP

Cavum Septum Pellucidum

- DBD

Disruptive Behavior Disorder

- PT

Psychopathic Traits

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflict declared.

References

- Barry CT, Frick PJ, DeShazo TM, McCoy MG, Ellis M, Loney BR. The importance of callous-unemotional traits for extending the concept of psychopathy to children. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(2):335–340. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. Neuroimaging of psychopathy and antisocial behavior: a targeted review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(1):76–82. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0086-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodensteiner JB, Schaefer GB. Wide cavum septum pellucidum: a marker of disturbed brain development. Pediatr Neurol. 1990;6(6):391–394. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90007-n. 0887-8994(90)90007-N [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Waldman I, Lahey BB. Predictive validity of childhood oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: Implications for the DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):739–751. doi: 10.1037/a0019708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu CN, Johnson AR, Zeisel SH. Dietary choline reverses some, but not all, effects of folate deficiency on neurogenesis and apoptosis in fetal mouse brain. J Nutr. 2010;140(6):1162–1166. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SL, Blair RJR. The development of antisocial behavior: What can we learn from functional neuroimaging studies? Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(4):1145–1159. doi: 10.1017/s0954579408000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito SA, Mechelli A, Wilke M, Laurens KR, Jones AP, Barker GJ, Viding E. Size matters: Increased grey matter in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Brain. 2009;132:843–852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53(6):1146–1158. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Frick PJ. Callous-Unemotional Traits in a Community Sample of Adolescents. Assessment. 2006;13(4):454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger EC, Marsh AA, Blair KS, Reid ME, Sims C, Ng P, Blair RJ. Disrupted reinforcement signaling in the orbitofrontal cortex and caudate in youths with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder and a high level of psychopathic traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(2):152–162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010129. appi.ajp.2010.10010129 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger EC, Marsh AA, Mitchell DG, Reid ME, Sims C, Budhani S, Blair JR. Abnormal ventromedial prefrontal cortex function in children with psychopathic traits during reversal learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):586–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.586. 65/5/586 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick . The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Department of Psychology. University of New Orleans; New Orleans: 2004. Unpublished Ratings Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, Hare . The Antisocial Process Screening Device. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, White SF. The importance of callous-unemotional traits for the development of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2008;49:359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Raine A, Yaralian PS, Yang Y. Increased volume of the striatum in psychopathic individuals. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. On the distinction between attentional deficits/hyperactivity and conduct problems/aggression in child psychopathology. Psychological bulletin. 1987;101(3):443–463. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AP, Laurens KR, Herba CM, Barker GJ, Viding E. Amygdala hypoactivity to fearful faces in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):95–102. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071050. appi.ajp.2008.07071050 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Lyoo IK, Dager SR, Friedman SD, Chey J, Hwang J, Renshaw PF. The occurrence of cavum septi pellucidi enlargement is increased in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(3):274–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Skeem JL, Marsee MA, Cruise K, Munoz LC, Morris AS. Assessing callous-unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the inventory of callous-unemotional traits. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2008;31(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawing K, Frick PJ, Cruise KR. Differences in offending patterns between adolescent sex offenders high or low in callous Äîunemotional traits. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22(2):298–305. doi: 10.1037/a0018707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Raine A. The effect of childhood malnutrition on externalizing behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(5):565–570. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245360.13949.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Mitchell DG, Reid ME, Sims C, Kosson DS, Blair RJ. Reduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):712–720. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071145. appi.ajp.2007.07071145 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May FS, Chen QC, Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Pitman RK. Cavum septum pellucidum in monozygotic twins discordant for combat exposure: relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(6):656–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellott TJ, Kowall NW, Lopez-Coviella I, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal choline deficiency increases choline transporter expression in the septum and hippocampus during postnatal development and in adulthood in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1151:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopoulos P, Berg S, Castellenos FX, Delgado A, Andreasen NC, Rapoport JL. Developmental brain anomalies in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 2000;15(2):102–108. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopoulos P, Krie A, Andreasen NC. Enlarged cavum septi pellucidi in patients with schizophrenia: clinical and cognitive correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(3):344–349. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti L, Fairchild G, Goodyer IM, Hurford G, Hagan CC, Rowe JB, Calder AJ. Neural abnormalities in early-onset and adolescence-onset conduct disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):729–738. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.75. 67/7/729 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Bartini M. Dominance in early adolescent boys: Affiliative and aggressive dimensions and possible functions. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2001;47(1):142–163. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2001.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Lee L, Yang Y, Colletti P. Neurodevelopmental marker for limbic maldevelopment in antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):186–192. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajarethinam R, Sohi J, Arfken C, Keshavan MS. No difference in the prevalence of cavum septum pellucidum (CSP) between first-episode schizophrenia patients, offspring of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;103(1–3):22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar M. The septum pellucidum: normal and abnormal. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10(5):989–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotz W, Phillips DI. Fetal origins of mental health: evidence and mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(7):905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O’Malley K, Young JK. Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25(4):228–238. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayze V, Johnson V, Hanson J, Piven J, Sato Y, Giedd J, Andreasen N. Magnestic Resonance Imaging of Brain Anomalies in Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Pediatrics. 1997;99:232–240. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EA, Schachar R, Thorley G, Wieselberg M. Conduct disorder and hyperactivity: I. Separation of hyperactivity and antisocial conduct in British child psychiatric patients. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149:760–767. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, Blair RJR, Moffitt TE, Plomin R. Evidence for substantial genetic risk for psychopathy in 7-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:592–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Kistner EO, Pine DS, Biesecker G, Pickett KE, Skol AD, Cook EH. Interaction of prenatal exposure to cigarettes and MAOA genotype in pathyways to youth antisocial behavior. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15(9):928–937. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S, Marsh A, Fowler K, Schechter J, Adalio C, Pope K, Blair J. Reduced amygdala responding in youth with Disruptive Behavior Disorder and Psychopathic Traits reflects a reduced emotional response not increased top-down attention to non-emotional features. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081270. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SF, Cruise KR, Frick PJ. Differential correlates to self-report and parent-report of callous-unemotional traits in a sample of juvenile sexual offenders. Behav Sci Law. 2009;27(6):910–928. doi: 10.1002/bsl.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Raine A, Narr KL, Colletti P, Toga AW. Localization of deformations within the amygdala in individuals with psychopathy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:986–994. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]