Abstract

Empathy is a rather elaborated human ability and several recent studies highlight significant impairments in patients suffering from psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression.

Therefore, the present study aimed at comparing behavioral empathy performance in schizophrenia, bipolar and depressed patients with healthy controls. All subjects performed three tasks tapping the core components of empathy: emotion recognition, emotional perspective taking and affective responsiveness. Groups were matched for age, gender, and verbal intelligence.

Data analysis revealed three main findings: First, schizophrenia patients showed the strongest impairment in empathic performance followed by bipolar patients while depressed patients performed similar to controls in most tasks, except for affective responsiveness. Second, a significant association between clinical characteristics and empathy performance was only apparent in depression, indicating worse affective responsiveness with stronger symptom severity and longer duration of illness. Third, self-report data indicate that particularly bipolar patients describe themselves as less empathic, reporting less empathic concern and less perspective taking.

Taken together, this study constitutes the first approach to directly compare specificity of empathic deficits in severe psychiatric disorders. Our results suggest disorder-specific impairments in emotional competencies that enable better characterization of the patient groups investigated and indicate different psychotherapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Empathy, Emotional competencies, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Depression

1. Introduction

While several studies compared neurocognitive functioning between patients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression (e.g., Simonsen et al., 2009, 2010; Zanelli et al., 2010; Tuulio-Henriksson et al., 2011), little is known about the specificity of emotional competencies in these major psychiatric disorders. Addington and Addington (1998) compared emotion recognition performance of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients and observed significantly poorer performance in schizophrenia patients, however patient groups were not matched for age, gender and education. Little is known about disorder-specific deficits in other emotional competencies such as empathic abilities, despite their relevance for successful social interaction. Correctly inferring emotional states and intentions via the observation of others' behavior is a prerequisite for successful social interaction and increase social coherence (De Vignemont and Singer, 2006). As a fundamental interpersonal phenomenon, empathy plays a vital role in all social interactions, and thus, deficits in empathic behavior may lead to social dysfunctions, including those that characterize major psychiatric disorders (Segrin, 2000; Blair, 2005; Henry et al., 2008).

According to most models we differentiate three core components of empathy (Decety and Jackson, 2004): 1) recognizing emotions in facial expressions, speech or behavior (gestic), 2) affectively responding to emotional states of others (affective empathy), and 3) taking over the perspective of another person, though the distinction between self and other remains intact (cognitive empathy, e.g., Ickes, 2003). Please see also Fig. 1 for illustration of the three components.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the three core components of empathy according to Decety and Jackson (2004).

The majority of previous studies in all three patient groups focused on emotion recognition and at least for schizophrenia and bipolar patients studies consistently demonstrated a difficulty of patients to infer the correct emotion from a facial expression (bipolar: e.g., Derntl et al., 2009a; Hoertnagl et al., 2011; schizophrenia: e.g., Schneider et al., 2006; Kohler et al., 2010). In depression, however, given the limited evidence, results are somewhat mixed (Wright et al., 2009; Anderson et al., 2011). According to a recent meta-analysis including 40 studies in depression (Bourke et al., 2010) there is some consistency in that depressed patients show a negative response bias towards sadness, such that neutral or ambiguous stimuli are evaluated as sad.

Regarding cognitive and affective empathy, results are less consistent. While schizophrenia patients show a significant deficit in both abilities (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2007; Bora et al., 2008; Langdon and Ward, 2009), euthymic bipolar patients show no significant impairment (Montag et al., 2010) but report lower levels of cognitive empathy and higher levels of personal distress (Cusi et al., 2010). In depression, Thoma et al. (2011) reported no significant behavioral deficit in cognitive and affective empathy but higher self-reported empathy scores, mainly driven by increased personal distress scores.

Directly comparing patient's performance with controls' in all three components, schizophrenia patients showed a significant general impairment (Derntl et al., 2009b), while bipolar patients exhibited a deficit in emotion recognition and affective empathy (Seidel et al., 2012).

Taken together, previous results indicate emotional dysfunctions in all three major psychiatric disorders, which may be associated with difficulties in social functioning (schizophrenia: Sparks et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2012; bipolar: Hoertnagl et al., 2011; depression: Cusi et al., 2011). It remains unclear, however, if these dysfunctions characterize psychiatric patients in general or whether there are disorder-specific patterns, which in turn could have implications for treatment strategies.

Therefore, the present study is the first attempt to directly compare performance regarding three different core components of empathy in patients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. Based on the previous findings on emotional abilities, we hypothesized worst performance in schizophrenia patients, particularly in emotion recognition (cf. Addington and Addington, 1998). Moreover, we analyzed whether groups show distinct self-report descriptions and investigated the impact of symptom severity on emotional performance.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

We relied on data of 24 schizophrenia patients (SZP; 12 females) meeting the DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (confirmed via structured clinical interview, SCID, Wittchen et al., 1997) that have been published previously (Derntl et al., 2009b). Twenty-four bipolar patients (BDP; 12 females) meeting the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (again confirmed via structured interview, MINI, Sheehan et al., 1998) have been included. A recent publication (Seidel et al., 2012) relies partly on the sample presented here. Additionally, 24 patients fulfilling the criteria for major depression (MDP; 12 females) and 24 healthy controls (CON; 12 females) were recruited and participated in this study. All subjects were matched for age, gender and (premorbid) verbal intelligence as can be seen in Table 1. Exclusion criteria for all subjects were substance abuse within the last six months, no neurological and no (other) psychiatric disorder (as assessed via structured clinical interviews). Schizophrenia patients were recruited from the in- and outpatient units of the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Medical School, RWTH Aachen University, Germany. Bipolar patients were recruited from the in- and outpatient units of the Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic and Psychotherapy, University of Regensburg, Germany, and the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy I, University Hospital Ulm, Weißenau, Germany. Depressed patients were recruited from the in- and outpatient units of the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Medical School, RWTH Aachen University, Germany and the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy I, University Hospital Ulm, Weißenau, Germany. Symptom severity in schizophrenia patients was measured with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay et al., 1987), in bipolar patients affective symptoms were assessed using the Young Mania Rating Scale (Young et al., 1978) and the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979) and in depressed patients the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck et al., 1961) and the 17-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD, Hamilton, 1960) were used. Moreover, all SZP patients received atypical antipsychotic medication except for one patient who was treated with both atypical and typical agents. BDP were taking the prescribed medication to ensure mood stabilization (antidepressant n = 2, neuroleptic n = 3, mood-stabilizer n = 7, antidepressants + neuroleptic n = 3, antidepressant + mood-stabilizer n = 1, mood-stabilizer + neuroleptic n = 6, combination of all three n = 2). Eight DP were unmedicated at the time of testing, the other 14 were all taking antidepressant medication except for one patient who received antidepressants and neuroleptics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic information on schizophrenia (SZP), bipolar (BDP), depressed (MDP) and healthy control participants (CON). Mean values are presented and standard deviations are listed in parentheses. All participants were matched for age, gender, and (premorbid) verbal intelligence and patient samples did not differ in their duration of illness.

| SZP (n = 24) | BDP (n = 24) | MDP (n = 24) | CON (n = 24) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 12:12 | 12:12 | 12:12 | 12:12 | – |

| Age (years) | 40.1 (8.7) | 44.0 (9.8) | 41.1 (10.6) | 39.9 (10.0) | 0.445 |

| Verbal IQ | 107.7 (12.7) | 108.9 (14.5) | 109.0 (13.4) | 111.3 (9.7) | 0.807 |

| Age of onset | 28.9 (9.2) | 37.9 (9.6) | 32.1 (9.8) | – | 0.010 |

| Illness duration | 11.5 (7.6) | 7.8 (5.4) | 8.2 (7.8) | – | 0.148 |

All subjects gave written informed consent prior to the start of the study. Procedures have been approved by local ethics committees in Aachen, Ulm and Regensburg.

All participants completed a test tapping crystallized verbal intelligence (MWT-B, Lehrl, 1996), as a measure of premorbid crystallized verbal intelligence and the German version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI, Davis, 1983; German version: Paulus, 2009) as a self-report measure of empathic abilities.

2.2. Empathy tasks

All participants performed the following three tasks:

2.2.1. Emotion recognition and age discrimination

60 colored Caucasian facial identities (Gur et al., 2002) depicting five basic emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust) and neutral expressions were presented maximally for 4 s. Half of the stimuli were used for emotion recognition, the other half for the age discrimination control task. For emotion recognition subjects had to determine the correct emotion by selecting from two emotion categories. For age recognition, subjects had to judge, which of two age decades was closer to the poser's age.

2.2.2. Emotional perspective taking

Participants viewed 60 pictures each presented for 4 s depicting scenes showing two Caucasians involved in social interaction thereby portraying five basic emotions and neutral scenes (10 stimuli per condition). The face of one person was masked and participants were asked to infer the corresponding emotional expression of the masked face that would fit the emotional situation. Responses were made by selecting between two different emotional facial expressions or a neutral expression presented after each scene. Facial alternatives were taken from the same stimulus set described above. One option was correct and the other was selected at random from all other choices. Again, scores were calculated as percent of items judged correctly and reaction times were assessed.

2.2.3. Affective responsiveness

We presented 150 short written sentences describing real-life situations, which are likely to induce basic emotions (the same emotions as described above), and situations that were emotionally neutral (25 stimuli per condition). Participants were asked to imagine how they would feel if they were experiencing those situations. Stimuli were presented for 4 s and response format was the same as for emotional perspective taking. Response format was kept maximally similar across tasks allowing comparisons between tasks, i.e. differences could be traced back to different task requirements not to different response formats. Similar to both other tasks, percent correct and reaction times were calculated and used for data analysis. Order of tasks was pseudo-counterbalanced in that the emotion recognition task was always presented first. However, the perspective taking task and the affective responsiveness task were counterbalanced in that half of the participants completed the perspective taking task first, the other half the affective responsiveness task.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 and level of significance was set at p = .05. Percent correct was analyzed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE; SPSS command GENLIN) accounting for non-normality of the dependent measures and/or violations of sphericity. For each empathy task, a full-factorial model was computed with emotion as within-subject factor, and group (SZP vs. BDP vs. MDP vs. CON) as between-subject factor. Analyses of emotional perspective taking and affective responsiveness tasks further included performance on emotion recognition and the respective other task as covariates to control for influences of response format on results and influences of the tasks on each other. Emotion recognition as investigated in our study using an explicit emotion recognition task constitutes the basic ability that underlies all higher empathic components, such as perspective taking and affective responsiveness. Therefore we suggested a unidirectional influence since neither perspective taking nor affective responsiveness is possible or adequate, if the corresponding emotion is not recognized correctly. To compare overall performance between the groups, we computed an additional model using GEE with task (3 levels) as within-subject factor, and group as between-subject factor.

Reaction times were analyzed for each task using repeated-measures ANOVAs with emotion as within-subject factor and group as between-subject factor. Moreover, to compare performance across tasks, we performed an additional repeated-measures ANOVA with task as within-subject factor and group as between-subject factor. Whenever violations of sphericity occurred, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected degrees of freedom and p-values are reported. Post hoc comparisons of the ANOVAs are Bonferroni corrected. Results of reaction time analyses are presented in the Supplementary material.

Group differences in the empathy questionnaire were assessed using univariate ANOVAs with group as fixed factor. Correlations between accuracy measures of the empathy paradigms, symptom severity scores, duration of illness, and self-report scores were computed using non-parametric methods (Spearman rank correlation).

3. Results

3.1. Empathy tasks

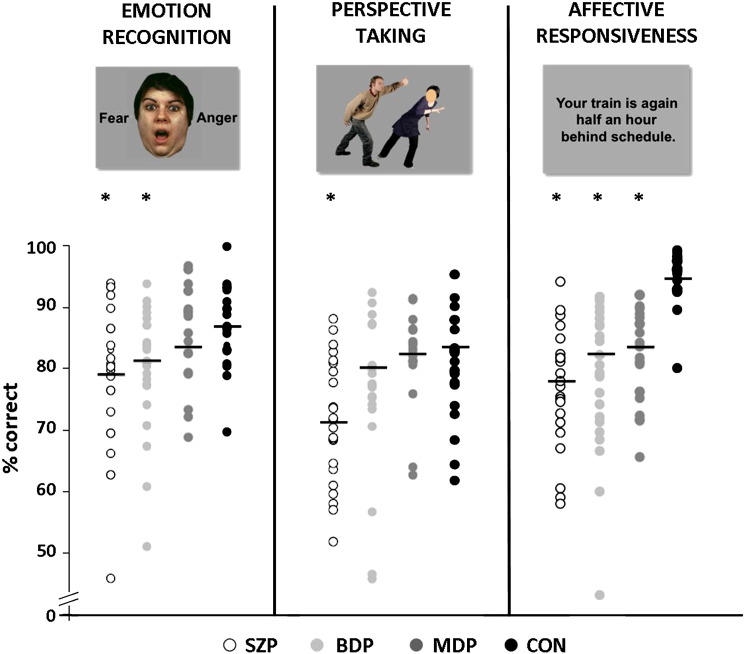

Fig. 2 illustrates mean performance of the four groups in the separate empathy tasks and Table 2 lists mean scores and standard deviations.

Fig. 2.

Performance (percent correct) for the three empathy tasks separately for each group. Direct comparison revealed significant differences between clinical groups and controls. Significant differences are marked with an asterisk. Note that equal performance of participants sometimes might be covered by only one data point.

Table 2.

Emotion-specific and total mean percent correct (and standard deviations in parentheses) for each task and each group.

| Anger | Disgust | Fear | Happiness | Sadness | Neutral | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia patients | |||||||

| Emotion recognition | 78.3 (20.4) | 75.0 (24.5) | 75.8 (23.6) | 93.3 (12.7) | 66.7 (18.3) | 89.2 (16.7) | 79.7 (12.2) |

| Perspective taking | 67.6 (23.9) | 60.9 (18.1) | 64.7 (15.6) | 84.3 (12.4) | 73.4 (22.9) | 76.5 (16.7) | 71.4 (9.8) |

| Affective responsiveness | 66.3 (18.0) | 78.8 (15.6) | 74.6 (15.1) | 91.1 (10.9) | 73.4 (11.0) | 87.0 (14.1) | 78.5 (10.3) |

| Bipolar disorder patients | |||||||

| Emotion recognition | 85.8 (22.4) | 82.5 (17.0) | 80.8 (18.2) | 92.5 (14.2) | 67.5 (22.7) | 86.7 (19.3) | 82.6 (10.1) |

| Perspective taking | 75.5 (18.5) | 64.2 (17.2) | 74.5 (19.8) | 92.9 (11.2) | 78.2 (17.8) | 81.3 (19.0) | 77.8 (12.3) |

| Affective responsiveness | 84.2 (20.2) | 87.1 (15.2) | 81.3 (15.4) | 94.2 (12.5) | 82.3 (15.1) | 89.2 (12.8) | 87.7 (11.9) |

| Major depression patients | |||||||

| Emotion recognition | 86.7 (21.0) | 80.8 (22.4) | 84.2 (16.7) | 91.7 (15.5) | 71.7 (20.4) | 77.5 (27.2) | 82.1 (13.6) |

| Perspective taking | 75.5 (16.7) | 71.7 (13.1) | 80.0 (12.9) | 92.9 (8.1) | 85.0 (13.6) | 87.9 (13.5) | 82.2 (7.3) |

| Affective responsiveness | 89.2 (11.8) | 85.0 (12.7) | 90.0 (9.7) | 89.6 (16.1) | 87.1 (8.3) | 94.2 (12.0) | 89.2 (7.6) |

| Controls | |||||||

| Emotion recognition | 92.5 (14.2) | 80.0 (18.7) | 87.5 (16.5) | 95.8 (10.2) | 76.7 (14.0) | 92.5 (15.4) | 87.4 (6.3) |

| Perspective taking | 74.1 (15.3) | 72.8 (17.2) | 75.9 (15.3) | 95.0 (7.2) | 84.7 (17.9) | 84.6 (16.7) | 82.8 (8.7) |

| Affective responsiveness | 90.8 (13.8) | 94.2 (9.7) | 97.5 (4.4) | 100 (0.0) | 92.5 (7.9) | 99.6 (2.0) | 95.8 (4.2) |

For emotion recognition, GEE accuracy analysis revealed a significant effect of group (Wald-χ2 = 8.694, df = 3, p = 0.034) with CON outperforming SZP (p = 0.017), BDP (p = 0.044) and a similar trend for MDP (p = 0.059). A significant main effect of emotion (Wald-χ2 = 91.252, df = 5, p < 0.001) but no significant emotion-by-group interaction (Wald-χ2 = 19.484, df = 15, p = 0.193) emerged. Post hoc analysis of the significant emotion effect showed highest accuracy for happy conditions (happy vs. disgust/fear/sad: p < 0.001; happy vs. anger: p = 0.008; happy vs. neutral: p = 0.023) followed by neutral, anger, fear, disgust and sad conditions.

Controlling for emotion recognition and affective responsiveness performance, we observed a significant main effect of group (Wald-χ2 = 22.522, df = 3, p < 0.001) with SZP performing worse than CON (p < 0.001), MDP (p < 0.001) and BDP (p = 0.029), while the other three groups did not differ (CON vs. MDP: p = 1; CON vs. BDP: p = 1; MDP vs. BDP: p = 0.702) in emotional perspective taking. A significant main effect of emotion (Wald-χ2 = 154.81, df = 5, p < 0.001) but no significant emotion-by-group interaction (Wald-χ2 = 11.837, df = 15, p = 0.691) emerged. Post hoc analysis of the significant emotion effect showed highest accuracy for happy conditions (happy vs. disgust/fear/sad: p < 0.001; happy vs. anger: p = 0.001, happy vs. neutral: p = 0.007) followed by neutral, anger, disgust, fear and sad conditions.

Controlling for emotion recognition and perspective taking performance, a highly significant group effect (Wald-χ2 = 646.378, df = 3, p < 0.001) occurred for affective responsiveness. CON outperformed SZP (p < 0.001), BDP (p < 0.001) and MDP (p < 0.01). SZP performed worse than BDP (p = 0.008) and MDP (p < 0.001), while BDP and MDP did not differ (p = 0.202). A significant main effect of emotion (Wald-χ2 = 1944.317, df = 5, p < 0.001) and a significant group-by-emotion interaction occurred (Wald-χ2 = 53.879, df = 15, p < 0.001). Emotion-specific post hoc GEE models demonstrated significant group effects for all negative emotions and neutral conditions (all p-values < 0.002) while no group effect occurred for happiness (p = 0.643). SZP performed worse for all emotions compared to CON (all p-values < 0.001) and MDP (all p-values < 0.037), while a significant difference to BDP only emerged for anger, fear, and sad stimuli (all p-values < 0.028). BDP differed from CON in responsiveness to disgust (p = 0.049), neutral (p = 0.037), and sad stimuli (p = 0.003) but not in anger (p = 0.173) or fear processing (p = 0.051). Interestingly, MDP did not differ from CON in the emotion-specific post hoc tests (all p-values > 0.069) but showed significantly better performance than BDP for sad stimuli (p = 0.029), while for all other emotions no significant difference emerged (all p-values > 0.091).

Comparing the overall accuracy across all tasks revealed a significant task effect (Wald-χ2 = 202.376, df = 3, p < 0.001) with lowest accuracy in affective responsiveness and highest in emotional perspective taking. A significant group effect (Wald-χ2 = 45.911, df = 3, p < 0.001) occurred with CON outperforming SZP (p < 0.001) and BDP (p = 0.005). There was only a trend for a difference between MDP (p = 0.059) and CON. SZP performed worse than BDP (p = 0.042) and MDP (p < 0.001) while BDP and MDP (p = 0.306) did not differ. A significant task-by-group interaction was observed (Wald-χ2 = 55.941, df = 9, p < 0.001), mirroring the task-specific analysis presented above.

3.2. Empathy self-report

We observed a significant group difference (F(3,89) = 3.010, p = 0.035) in the self-report empathy sum-score with lower scores in BDP compared to CON (p = 0.009) and MDP (p = 0.019). There was a significant group effect regarding the subscale fantasy (F(3,89) = 3.614, p = 0.016) with SZP showing lower scores than CON (p = 0.005) and BDP (p = 0.008), but no difference compared to MDP (p = 0.071). Regarding the subscale perspective taking, the main effect of group (F(3,89) = 9.828, p < 0.001) was triggered by BDP scoring lower than all other groups (all p-values < 0.001). The group effect regarding personal distress (F(3,89) = 2.937, p = 0.038) was driven by CON scoring lower than all patient groups (SZP: p = 0.010, MDP: p = 0.018, BDP: p = 0.036). For empathic concern, we observed a group difference (F(3,89) = 2.774, p = 0.046) due to BDP scoring lower than CON (p = 0.031) and MDP (p = 0.009). Mean scores are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for the self-reported empathic abilities using the German version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index.

| SZP | BDP | MDP | CON | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPF fantasy | 12.0 (3.0) | 14.8 (3.5) | 13.8 (3.8) | 14.9 (3.1) |

| SPF perspective taking | 14.9 (2.5) | 12.0 (3.6) | 15.7 (2.1) | 15.6 (1.6) |

| SPF empathic concern | 14.7 (2.8) | 13.7 (2.7) | 15.8 (2.5) | 15.4 (1.9) |

| SPF personal distress | 11.9 (2.4) | 11.6 (2.8) | 11.8 (3.2) | 9.8 (2.4) |

| SPF empathy | 42.8 (7.2) | 40.6 (8.1) | 45.3 (5.6) | 45.9 (4.5) |

| SPF total | 30.9 (7.4) | 28.8 (8.7) | 33.5 (5.5) | 36.0 (5.3) |

Note: SPF = Saarbrückener Persönlichkeitsfragebogen by Paulus (2009) (German version of Interpersonal Reactivity Index, IRI, Davis, 1983).

Correlation of behavioral performance (accuracy) and self-report data revealed no significant association in any of the groups (SZP: all p > 0.063; BDP: all p > 0.166; MDP: all p > 0.062; CON: all p > 0.096).

3.3. Clinical characteristics

Symptom severity scores in MDP correlated with accuracy in affective responsiveness (BDI: rho = − 0.482, p = 0.009; HAMD: rho = − 0.412, p = 0.045), however, MADRS scores or YMRS scores in BDP were not correlated to accuracy in any of our empathy tasks (all p-values > 0.061). Correlation analysis with PANSS scores and performance in the empathy tasks revealed no significant results for SZP, too (p > 0.071).

Regarding duration of illness, only MDP showed a significant negative association with affective responsiveness scores (rho = − 0.421, p = 0.029) indicating worse performance with longer duration. However, for both other patient groups no significant association with duration of illness emerged (both p > 0.072).

4. Discussion

This study examined disorder-specificity of emotional deficits in three groups of psychiatric patients compared to healthy controls, all matched for age, gender, and verbal intelligence. Emotional dysfunctions have been reported for different psychiatric conditions and have been associated with social functioning in general. What remains unclear is how specific these dysfunctions are and how they characterize certain patient groups.

To probe disorder-specificity of specific emotional competencies, we applied three tasks measuring emotion recognition, emotional perspective taking, and affective responsiveness in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (SZP), bipolar disorder (BDP), or major depression (MDP) and healthy controls (CON). There were three main findings. First, SZP presented the most severe empathy impairment followed by BDP while MDP performed similar to CON in most tasks, except for affective responsiveness. Second, a significant association between clinical characteristics and empathy performance was only apparent in MDP while no correlations emerged for SZP and BDP. In MDP, affective responsiveness performance was significantly negatively correlated with symptom severity as well as with duration of illness. Third, self-report data indicate that particularly BDP describe themselves as less empathic than all other groups, reporting less empathic concern and less perspective taking. These results have several implications.

4.1. Patients with SZP show the strongest impairment in behavioral empathy performance

Behavioral deficits in specific empathy components, such as emotion recognition, have been reported for all three patient groups (SZP: Schneider et al., 2006; Kohler et al., 2010; BDP: Derntl et al., 2009a; Kohler et al., 2011; MDP: Bourke et al., 2010; Kohler et al., 2011). Previously, we reported a more general emotional deficit in SZP comprising all core components (Derntl et al., 2009b) and a specific deficit in emotion recognition and affective responsiveness in BDP (Seidel et al., 2012). However, in these previous studies we compared patients with matched healthy controls. But only the comparison with other clinical samples who are also medicated, hospitalized, and have comparable duration of illness' can delineate which deficits are specific for which disorder and what may be a general dysfunction in all major psychiatric conditions.

Our results indicate that SZP are characterized by a pronounced impairment in all empathy tasks including general face processing and thus extend previous findings comparing facial affect recognition in SZP and BDP (Addington and Addington, 1998). Notably, SZP show a particular deficit in emotional perspective taking and affective responsiveness when compared to both other clinical samples. Hence, the ability to quickly infer an emotional state of another person by taking the social context and people's behavior into account (here emotional perspective taking) as well as the ability to put oneself in a certain extrinsic emotional condition (here affective responsiveness) seem specifically dysfunctional in SZP. Interestingly, these difficulties are not reflected in reaction times (see supplementary material), as SZP performed similar to CON and showed even faster response times than MDP and BDP across all three tasks. Regarding self-reported empathy, SZP did not differ from MDP in any subscale but showed lower fantasy scores than CON and BDP. Interestingly, SZP did not report a perspective taking impairment paralleling results in first-episode SZP (Achim et al., 2011) but contrasting data from several previous studies on chronic SZP patients (e.g., Smith et al., 2012; for meta-analysis see Achim et al., 2011). All three clinical groups reported higher personal distress levels than CON, mirroring prior results (e.g., Cusi et al., 2010; Achim et al., 2011). Recently, Simonsen et al. (2010) reported a significant discrepancy between clinician-rated psychosocial functioning and self-report data in SZP indicating that patients have poorer insight into their functional level than other patients, resulting in high self-ratings for social functioning. Based on the observed discrepancy between significantly decreased accuracy but preserved reaction time data, unimpaired self-ratings in perspective taking and empathic concern, as well as findings from Simonsen et al. (2010), we speculate that SZP might not be fully aware of their severe empathic deficit which should be further explored in future studies.

Our findings of worse performance in SZP parallel those from studies exploring neurocognitive functioning (attention, executive function, processing speed, memory, etc.) in these patients (cf. Reichenberg et al., 2009; Simonsen et al., 2009, 2010; Zanelli et al., 2010; Harvey, 2011; Tuulio-Henriksson et al., 2011). Those studies also showed stronger impairments in SZP on all cognitive domains compared to patients with affective disorders. These findings support the notion that schizophrenia has the most severe impact on general human abilities, including cognition and emotional functioning.

4.2. Difficulties in affective responsiveness are associated with severity indicators in MDP

MDP seem to be characterized by a significant deficit only in affective responsiveness compared to CON, which was negatively correlated with BDI scores and illness duration. Our data did not show any association between clinical characteristics (symptom severity, age of onset, duration of illness) and behavioral empathy in SZP and BDP, thereby supporting previous findings (SZP: Lee et al., 2004; Brüne, 2005; BDP: Bora et al., 2005; Wolf et al., 2010). The affective responsiveness task targets generation and experience of basic emotions and MDP performed better with less symptom severity. Although we observed impairments in affective responsiveness in SZP and BDP, too, and patient groups showed similar illness duration, their deficits seem less associated with clinical characteristics and thus more state-independent. A similar impact of symptom severity only in the depressed sample (compared to BDP and SCZ) has also been shown for neurocognitive deficits (cf. Tuulio-Henriksson et al., 2011), further supporting the notion that cognitive and socio-emotional impairments in MDP are strongly state-dependent.

4.3. Discrepancy between actual performance and self-report data in BDP

In BDP we observed a more differentiated pattern. BDP showed significantly reduced accuracy in emotion recognition and affective responsiveness compared to CON, while they performed similar to MDP and showed significantly better emotional perspective taking compared to SZP. Hence, our data not only support previous findings on deficient emotion recognition accuracy in BDP (e.g., Derntl et al., 2009a; Hoertnagl et al., 2011), but also indicate that these patients have problems putting themselves in a certain extrinsic emotional condition. However, the unimpaired perspective taking performance indicates that BDP seem to profit from contextual information when interpreting the emotional meaning of a social situation compared to inferring emotions from facial displays only.

Analysis of self-report data revealed that all patients reported higher distress ratings than CON, which has been reported in previous studies (SZP: Montag et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2012; BDP: Cusi et al., 2010, MDP: Cusi et al., 2011). Interestingly, BDP described themselves as less empathic, reporting less empathic concern and less perspective taking. Particularly their self-reported lack of perspective taking compared to both other patient groups stands in strong contrast with their unaffected behavioral performance. BDP showed similar performance as MDP and CON and outperformed SZP. In a previous study by Simonsen et al. (2010), BDP rated their psychosocial functioning worse than clinicians did and authors argue that BDP might be more susceptible to compare themselves with unimpaired peers, thus expecting a higher level of functioning.

Self-report data in general may provide limited access to the exact nature and extent of empathic impairments and are subject to response tendencies. Although important, relying on self-reports only is not sufficient to characterize empathic abilities and deficits, thus behavioral tasks are advantageous here (Dimaggio et al., 2008).

5. Limitations

While this study provides important new insights into disorder-specific emotional competencies, i.e. empathic behavior, several methodological constraints have to be acknowledged. The sample sizes are small preventing, e.g. analysis of the impact of diagnostic subgroups on empathic abilities. Particularly regarding BDP, previous data indicate that BDP types I and II might not only differ in cognitive abilities (Martinez-Aran et al., 2008; Simonsen et al., 2009) but also in emotional capacities (cf. Derntl et al., 2009a). Exploratory analysis revealed no group differences for any of the tasks (all p > .499), however, sample sizes (BPI: n = 13, BPII: n = 11) were far too small and further studies should address this issue in larger samples. A previous meta-analysis also indicated that history of psychotic episodes worsens cognitive performance in bipolar patients (Bora et al., 2010). While we gathered this information in SZP and MDP patients, data from BDP were not complete in this regard thereby preventing analysis of the impact of history of psychotic episodes on emotional performance. Additionally, most patients were medicated and most of them were chronic patients. However, results from a recent meta-analysis showed no significant effect of medication on emotional experience in SZP (Cohen and Minor, 2010). Moreover, several longitudinal studies observed no significant effect of drug treatment on emotion deficits in SZP (e.g., Harvey et al., 2006), thereby suggesting that socio-emotional impairments seem to be quite independent from pharmacological treatment. A recent meta-analysis on social cognition deficits in BDP also reports no significant associations between medication and patient-control effect size differences (Samamé et al., 2012). Contrary, previous studies in MDP show that antidepressants normalize face emotion recognition independent of mood state (Anderson et al., 2011), supporting the hypothesis that antidepressants alter emotional processing rather than having direct effects on mood (Harmer, 2010). Nevertheless, this study was not designed to investigate the impact of medication on empathic abilities and we cannot exclude the influence of medication on the observed performance in our patient samples.

6. Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study highlights that SZP are particularly characterized by a severe impairment in emotional perspective taking and affective responsiveness, when compared with healthy controls and patients suffering from affective disorders (BDP and MDP). Looking at clinical characteristics, we observed a significant association between symptom severity, duration of illness and performance in affective responsiveness in MDP, pointing to a state-dependent dysfunction, while no such relation emerged for BDP and SZP. Regarding self-report data on empathic abilities, BDP rate themselves as significantly less empathic compared to SZP, MDP, and CON thereby reflecting recent findings on a self-report bias regarding psychosocial functioning in this clinical sample.

Taken together, this study showed that analysis of specificity of empathic deficits helps to better characterize emotional deficits in patients suffering from severe psychiatric disorders. Moreover, our data provide input for disorder-specific psychotherapeutic treatment. Consistent with previous reports, our data clearly support the need of specific training programs to improve high-level emotional competencies particularly in SZP going beyond emotion recognition training. In BDP, therapists should encourage patients to correct their negative self-evaluation as regards to empathic competencies especially by relying on accurate perspective taking in complex social situations as a particular resource.

Role of funding source

Funding for this study was provided by the IZKF grant TVN70 to U.H. The IZKF had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

BD and UH designed the study. BD and EMS acquired the data and performed data analysis. BD, EMS, and UH wrote the manuscript and FS helped with discussion and interpretation of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

B.D., F.S. and U.H. were supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG: IRTG 1328; Ha3202/7-1) and authors B.D., E-M.S. and U.H. were supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF: P23533). U.H. and F.S. were also supported by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association (Helmholtz Alliance for Mental Health in an Ageing Society).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.09.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary materials.

References

- Achim A.M., Ouellet R., Roy M.-A., Jackson P.L. Assessment of empathy in first-episode psychosis and meta-analytic comparison with previous studies in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J., Addington D. Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Res. 1998;32(3):171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson I.M., Shippen C., Juhasz G., Chase D., Thomas E., Downey D., Toth Z.G., Lloyd-Williams K., Elliott R., Deakin J.F. State-dependent alteration in face emotion recognition in depression. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):302–308. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Erbaugh J., Ward C.H., Mock J., Mendelsohn M. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R.J. Responding to the emotions of others: dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious. Cogn. 2005;14(4):698–718. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E., Vahip S., Gonul A.S., Akdeniz F., Alkan M., Ogut M., Eryavuz A. Evidence for theory of mind deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2005;112(2):110–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E., Gökçen S., Veznedaroglu B. Empathic abilities in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E., Yücel M., Pantelis C. Neurocognitive markers of psychosis in bipolar disorder : a meta-analytic study. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;127:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke C., Douglas K., Porter R. Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: a review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;44:681–696. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.496359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüne M. Emotion recognition, ‘theory of mind’, and social behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(2–3):135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A.S., Minor K.S. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusi A., Macqueen G.M., McKinnon M.C. Altered self-report of empathic responding in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:354–358. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusi A., Macqueen G.M., Spreng R.N., McKinnon M.C. Altered empathic responding in major depressive disorder: relation to symptom severity, illness burden, and psychosocial outcome. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.H. The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. 1983;51:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- De Vignemont F., Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006;10(10):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Jackson P.L. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2004;3(2):71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl B., Seidel E.M., Kryspin-Exner I., Hasmann A., Dobmeier M. Facial emotion recognition in patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009;48:363–375. doi: 10.1348/014466509X404845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl B., Finkelmeyer A., Toygar T.K., Hülsmann A., Schneider F., Falkenberg D.I., Habel U. Generalized deficit in all core components of empathy in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009;108(1–3):197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimaggio G., Lysaker P.H., Carcione A., Nicolo G., Semerari A. Know yourself and you shall know the other…to a certain extent: multiple paths of influence of self-reflection on mindreading. Conscious. Cogn. 2008;17:778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur R.C., Sara R., Hagendoorn M., Marom O., Hughett P., Macy L., Turner T., Bajcsy R., Posner A., Gur R.E. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2002;115(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C.J. Antidepressant drug action: a neuropsychological perspective. Depress. Anxiety. 2010;27:231–233. doi: 10.1002/da.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.D. Mood symptoms, cognition, and everyday functioning in major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2011;8:14–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.D., Patterson T.L., Potter L.S., Zhong K., Brecher M. Improvement in social competence with short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment: a randomized, double-blind comparison of quetiapine versus risperidone for social competence, social cognition, and neuropsychological functioning. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:1918–1925. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry C., Van den Bulke D., Bellivier F., Roy I., Swendsen J., M'Bailara K., Siever L.J., Leboyer M. Affective lability and affect intensity as core dimensions of bipolar disorders during euthymic period. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159(1–2):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoertnagl C.M., Muehlbacher M., Biedermann F., Yalcin N., Baumgartner S., Schwitzer G., Deisenhammer E.A., Hausmann A., Kemmler G., Benecke C., Hofer A. Facial emotion recognition and its relationship to subjective and functional outcomes in remitted patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(5–6):537–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickes W. Prometheus Books; Amherst, NY: 2003. Everyday mind reading: Understanding what other people think and feel. [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler C.G., Walker J.B., Martin E.A., Healey K.M., Moberg P.J. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36(5):1009–1019. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler C.G., Hoffman L.J., Eastman L.B., Healey K., Moberg P. Facial emotion perception in depression and bipolar disorder: a quantitative review. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188(3):303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon R., Ward P. Taking the perspective of the other contributes to awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35(5):1003–1011. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.H., Farrow T.F., Spence S.A., Woodruff P.W. Social cognition, brain networks and schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2004;34:391–400. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrl S. Der MWT- ein Intelligenztest für die ärztliche Praxis. Prax. Neurol. Psychiatr. 1996;7:488–491. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aran A., Torrent C., Tabares-Seisdedos R., Salamero M., Daban C., Balanza-Martinez V., Sanchez-Moreno J., Manuel Goikolea J., Benabarre A., Colom F., Vieta E. Neurocognitive impairment in bipolar patients with and without history of psychosis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):233–239. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C., Heinz A., Kunz D., Gallinat J. Self-reported empathic abilities in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2007;92(1–3):85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C., Ehrlich A., Neuhaus K., Dziobek I., Heekeren H.R., Heinz A., Gallinat J. Theory of mind impairments in euthymic bipolar patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;123(1–3):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S.A., Asberg M. New depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus C. Der Saarbrücker Persönlichkeitsfragebogen SPF(IRI) zur Messung von Empathie: Psychometrische Evaluation der deutschen Version des Interpersonal Reactivity Index. 2009. http://psydok.sulb.uni-saarland.de/volltexte/2009/2363/

- Reichenberg A., Harvey P.D., Bowie C.R., Mojtabai R., Rabinowitz J., Heaton R.K., Bromet E. Neuropsychological function and dysfunction in schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35(5):1022–1029. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samamé C., Martino D.J., Strejilevich S.A. Social cognition in euthymic bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analytic approach. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012;125:266–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F., Gur R.C., Koch K., Backes V., Amunts K., Shah N.J., Bilker W., Gur R.E., Habel U. Impairment in the specificity of emotion processing in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):442–447. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C. Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000;20(3):379–403. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel E.M., Habel U., Finkelmeyer A., Hasmann A., Dobmeier M., Derntl B. Risk or resilience? Empathic abilities in patients with bipolar disorders and their first-degree relatives. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012;46:382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory S.G., Shur S., Harari H., Levkovitz Y. Neurocognitive basis of impaired empathy in schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(4):431–438. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(S20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen C., Sundet K., Vaskinn A., Birkenaes A.B., Engh J.A., Faerden A., Jónsdóttir H., Ringen P.A., Opjordsmoen S., Melle I., Friis S., Andreassen O.A. Neurocognitive dysfunction in bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorders depends on history of psychosis rather than diagnostic group. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;37(1):73–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen C., Sundet K., Vaskinn A., Ueland T., Romm K.L., Hellvin T., Melle I., Friis S., Andreassen O.A. Psychosocial function in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: relationship to neurocognition and clinical symptoms. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2010;16(5):771–783. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.J., Horan W.P., Karpouzian T.M., Abram S.V., Cobia D.J., Csernansky J.G. Self-reported empathy deficits are uniquely associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012;137(1–3):196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks A., McDonald S., Lino B., O'Donnell M., Green M.J. Social cognition, empathy and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2010;122:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma P., Zalewski I., von Reventlow H.G., Norra C., Juckel G., Daum I. Cognitive and affective empathy in depression linked to executive control. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuulio-Henriksson A., Perälä J., Saarni S.I., Isometsä E., Koskinen S., Lönnqvist J., Suvisaari J. Cognitive functioning in severe psychiatric disorders: a general population study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011;261:447–456. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.U., Zaudig M., Fydrich T. Hogrefe; Göttingen: 1997. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf F., Brüne M., Assion H.J. Theory of mind and neurocognitive functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(6):657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S.L., Langenecker S.A., Deldin P.J., Rapport L.J., Nielson K.A., Kade A.M., Own L.S., Akil H., Young E.A., Zubieta J.K. Gender-specific disruptions in emotion processing in younger adults with depression. Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26(2):182–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R.C., Biggs J.T., Ziegler V.E., Meyer D.A. Rating-scale for mania — reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli J., Reichenberg A., Morgan K., Fearon P., Kravariti E., Dazzan P., Morgan C., Zanelli C., Demjaha A., Jones P.B., Doody G.A., Kapur S., Murray R.M. Specific and generalized neuropsychological deficits: a comparison of patients with various first-episode psychosis presentations. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167:78–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials.