Abstract

Objective

The longer-term efficacy of medication treatments for binge eating disorder (BED) remains unknown. This study examined the longer-term effects of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) either with fluoxetine (CBT+fluoxetine) or with placebo (CBT+placebo) for BED through 12-month follow-up after completing treatments.

Method

81 overweight patients with BED within a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled acute treatment trial allocated to fluoxetine-only, CBT+fluoxetine, and CBT+placebo were assessed before, during, post-treatment, and 6- and 12-months after completing treatments. Outcome variables comprised remission from binge-eating (zero binge-eating episodes for 28 days) and continuous measures of binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology, depression, and weight.

Results

Intent-to-treat remission rates (missing data coded as non-remission) differed significantly across treatments at post-treatment and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. At 12-month follow-up remission rates were: 3.7% for fluoxetine-only, 26.9% for CBT+fluoxetine, and 35.7% for CBT+placebo. Mixed-effects models of all available continuous data (without imputation) at post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups (controlling for baseline scores) revealed the treatments differed on all clinical outcome variables, except for weight, across time. CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ and both were significantly superior to fluoxetine-only on the majority of clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

This represents the first report from any randomized placebo-controlled trial for BED that has reported follow-up data after completing a course of medication-only treatment. CBT+placebo was superior to fluoxetine-only and adding fluoxetine to CBT did not enhance findings compared to adding placebo to CBT. The findings document the longer-term effectiveness of CBT, but not fluoxetine, through 12-months after treatment completion.

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent binge-eating, marked distress, and the absence of inappropriate weight compensatory behaviors. BED is prevalent and associated with obesity and with elevated psychosocial impairment (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007), but differs from obesity and other eating disorders (Grilo, Masheb, & White, 2010). Critical reviews (Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007) and treatment guidelines (NICE, 2004) indicate CBT, the most extensively evaluated treatment for BED, reliably produces robust improvements in binge eating, eating pathology, and psychosocial variables, but fails to produce weight loss (Wilson et al., 2007). Studies have further documented that the effects of CBT are maintained well following treatment for 12-months (Grilo, Masheb, Wilson, Gueorguieva, & White, 2011; Wilfley et al., 2002) and may be durable through 48-months (Hilbert et al., 2012).

CBT, a specialist therapy, is not always readily available and research has identified other treatments for BED including less intensive and readily available pharmacotherapy (Reas & Grilo, 2008). NICE (2004) guidelines note that patients with BED can be informed that SSRI antidepressants can reduce binge eating, may suffice for some patients, but that long-term effects are unknown. Thus, NICE (2004) suggests SSRIs are an acceptable treatment for BED (a recommendation graded methodologically as a “B,” which represents less rigor and support than the grade “A” assigned to CBT as the best-established treatment). Randomized placebo-controlled trials have produced mixed findings for SSRI antidepressants, including fluoxetine and fluoxamine (NICE, 2004; Reas & Grilo, 2008). A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant medication for BED (7 studies with 335 patients) reported a significant but modest effect size (relative-risk of 0.19) for medication versus placebo (Reas & Grilo, 2008). Only two studies have directly compared CBT to antidepressant medication for BED (Grilo et al., 2005; Ricca et al., 2001). In a double-blind placebo-controlled study, Grilo et al. (2005) reported that CBT was significantly more effective than fluoxetine across multiple outcomes including a two-fold advantage for producing remission from binge eating. Ricca and colleagues (2001), in an open-label comparative trial, reported CBT was significantly more effective than either fluoxetine or fluvoxamine at post-treatment and at 12-month follow-up. Remarkably, the Ricca et al (2001) comparative open-label study is the sole published paper containing follow-up data for medication-only treatment for BED. One additional study (Devlin et al., 2007) reported that when administered concurrently with behavioral weight loss, CBT – but not fluoxetine – enhanced binge-eating outcomes through 24-months; this study, however, did not investigate the effects of either CBT or fluoxetine-only.

Thus, no placebo-controlled trial has reported follow-up data for any medication-only treatment for BED (Reas & Grilo, 2008), leading some (Wilson, 2011) to question the basis for recommending such treatments. Treatment guidelines (e.g., NICE, 2004) suggest antidepressant medications are a possible treatment option for BED and the clinical reality is that they are widely prescribed. Longer-term follow-up data for SSRIs for BED is needed to inform important questions about durability of outcomes and whether patients who show a response to acute treatment can discontinue taking the medication without relapsing. In the present paper, we extend our initial report of acute outcomes of fluoxetine and CBT for BED (Grilo et al., 2005) by examining longer-term effects of fluoxetine and CBT either with fluoxetine (CBT+fluoxetine) or with placebo (CBT+placebo) through 12-month follow-up after treatment completion.

Method

Participants

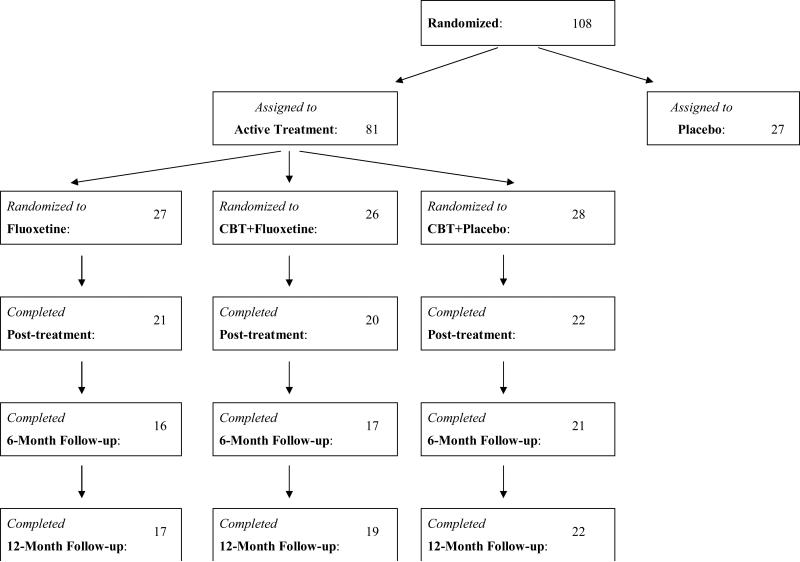

Participants in this report were 81 patients with BED (DSM-IV research criteria) who participated in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial testing CBT and fluoxetine alone and in combination (Grilo et al., 2005). Eligibility required age 18-60 years and between 100% and 200% of ideal weight for height based on 1959 Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tables. Exclusion criteria included any concurrent treatment for eating, weight, or psychiatric problems; medical conditions (diabetes, thyroid problems) that influence eating/weight; severe current psychiatric conditions requiring different treatments (psychosis, bipolar disorder, current substance dependence); and pregnancy or lactation. The study was IRB approved at Yale and all participants provided written informed consent. Figure 1 summarizes flow throughout the study.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants throughout study.

In total, 108 consecutive participants were randomized to one of four treatments in a balanced 2-by-2 factorial design: placebo (N=27), fluoxetine (N=27), CBT+fluoxetine (N=26), or CBT+placebo (N=28). The randomization schedule was computer-generated without restriction created in blocks of eight and maintained by a research pharmacist separate from (blinded) investigators. Only the 81 participants receiving fluoxetine, CBT+fluoxetine, and CBT+placebo interventions were included in the present study. Participants receiving placebo-only were excluded from these analyses because they were offered CBT or interpersonal psychotherapy following post-treatment assessments when the medication double-blind was broken. The 27 excluded participants did not differ from the 81 participants on any demographic or clinical variables (Grilo et al., 2005). Overall, the 81 participants were aged 21 to 59 years (M = 44.2, SD = 8.6), 75.3% (N = 61) were female, 93.8% (N = 76) were Caucasian, and 86.4% (N = 70) attended or finished college. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 36.9 (SD = 8.2).

Diagnostic Assessments and Outcome Measures

Assessments were performed by trained doctoral-level research-clinicians. At baseline, BED was diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) and all were confirmed with the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). The EDE interview focuses on the previous 28 days except for diagnostic items, which are rated for required durations. The EDE assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; i.e., binge eating) and has four subscales and a global score reflecting eating psychopathology. Outcome assessments were administered pre-, during-, and post-treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The Eating Disorder Examination -Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994) has good test-retest reliability (Reas, Grilo, & Masheb, 2006) and converges well with the EDE interview (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) 21-item version is a psychometrically-sound measure of depression levels. BMI was calculated from measured height and measured weights (throughout study).

Treatment Conditions

Medication was administered with minimal clinical management limited to medication adherence and addressing any side-effects. Brief (10 minute) clinical management meetings were held weekly during the first four weekly and bi-weekly thereafter. Participants were told to take three pills each morning for four months. Double-blind medications (prepared in identical capsules) were fixed-dose throughout the study consisting of either fluoxetine (60 mg/day) or placebo. Medication assignment blind was broken after the post-treatment assessment. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was administered in weekly individual 60-minute sessions for four months by doctoral research-clinicians following a manual (Fairburn et al., 1993).

Overview of Analyses

The primary treatment outcome was “remission” from binge eating (defined as zero binge eating episodes during previous 28 days) analyzed using intent-to-treat chi-square analyses with all randomized patients (baseline carried forward in instances of missing data, i.e., missing classified as non-remission) performed at each of the post-treatment and follow-up assessment time-points. Mixed-effects models (SPSS Version 19.0.0) compared treatments on continuous outcome variables, which included: binge-eating frequency (number of OBEs on the EDE-Q), eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE-Q scales and global score), depression (BDI score), and BMI (and weight change). Mixed-effects models were based on the general linear model except for the analysis of OBEs, which used a general estimating equations (GEE) model with negative binomial distribution. Mixed-effects models used all available data (without imputation) at post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up and controlled for baseline scores. Mixed models generated main effects tests for treatment and time, and treatment-by-time interaction, and post hoc comparisons were performed between treatments at each of the assessment time-points.

Results

Of the 81 participants randomized to the three treatments, 66.7% (N=54) completed 6-month and 71.6% (N=58) completed 12-month follow-ups (see Figure 1). The three treatment groups did not differ significantly on any demographic or pretreatment levels of any outcome variable, nor did they differ significantly in treatment completion rates (78% for fluoxetine; 77% for CBT+fluoxetine, and 79% for CBT+placebo) (Grilo et al., 2005). The 58 participants who completed versus the 23 participants who did not complete follow-ups did not differ significantly on any demographic or pretreatment clinical variable (p values = 0.132 – 0.820).

Primary Treatment Outcomes: Remission from Binge Eating

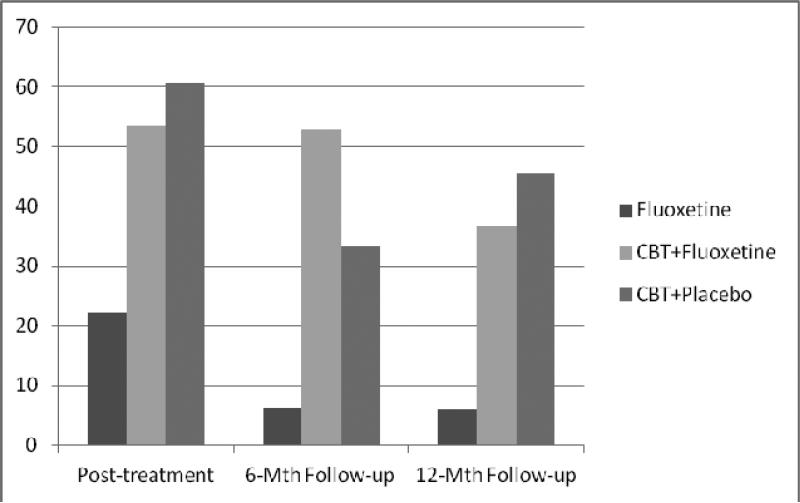

Figure 2-A shows remission rates (defined as zero binge-eating episodes during previous month) for ITT analyses with all randomized patients (baseline carried forward in instances of missing data) across the follow-ups. At 6-month follow-up, remission rates differed significantly across treatments (chi-square (2, N=81) = 8.048, p=0.018): 3.7% (n=1/27) for fluoxetine, 34.6% (n=9/26) for CBT+fluoxetine, and 25% (n=7/28) for CBT+placebo. Posthoc tests revealed that CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ significantly (Fisher's Exact Test p=0.55) but both differed from fluoxetine-only (Fisher Exact Test p=0.005 and p=0.05, respectively). At 12-month follow-up, remission rates differed significantly across treatments (chi-square (2, N = 81) = 8.639, p = 0.012): 3.7% (n = 1/27) for fluoxetine, 26.9% (n = 7/26) for CBT+fluoxetine, and 35.7% (n = 10/28) for CBT+placebo. Posthoc tests revealed that CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ significantly (Fisher's Exact Test p=0.57) but both differed from fluoxetine-only (Fisher Exact Test p=0.024 and p =0.005, respectively).1

Figure 2-A. Remission rates across follow-up assessments (intent-to-treat; N=81).

Percentage of participants receiving the three acute treatments (fluoxetine, CBT+fluoxetine, or CBT+placebo) who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment, 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. Remission is defined as zero binge eating episodes for the previous month based on the Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire. Intent-to-treat analysis for all randomized participants (n=81) with baseline carried forward method for instances of missing data (i.e., missing coded as non-remission).

Analyses revealed similar findings when restricted to participants for whom follow-up data were obtained (i.e., completer analysis). As shown in Figure 2-B, at 6-month follow-up, remission rates differed across treatments (chi-square (2, N=54)=8.385, p=0.015): 6.3% (n=1/16) for fluoxetine, 52.9% (n=9/17) for CBT+fluoxetine, and 33.3% (n=7/21) for CBT+placebo. Posthoc tests revealed that CBT+fluoxetine differed significantly from fluoxetine-only (Fisher Exact Test p=0.007). At 12-month follow-up, remission rates differed across treatments (chi-square (2, N=58) = 7.46, p = 0.02): 5.9% (n=1/17) for fluoxetine, 36.8% (n=7/19) for CBT+fluoxetine, and 45.5% (n=10/22) for CBT+placebo. Posthoc tests revealed CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ significantly (Fisher's Exact Test p=0.75) but both differed from fluoxetine-only (Fisher Exact Test p=0.04 and p =0.01, respectively).

Figure 2-B. Remission rates across follow-up assessments for those who completed assessments.

Percentage of participants receiving the three acute treatments (fluoxetine, CBT+fluoxetine, or CBT+placebo) who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment (N=81), 6-month and (N=54), and 12-month follow-up assessments (N=58). Remission is defined as zero binge eating episodes for the previous month based on the Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire. Data are shown for those who completed the assesments at each time-point without imputation (completer analysis).

Secondary Treatment Outcomes: Continuous Measures

Table 1 summarizes mixed-effects models for the continuous outcome variables for all 81 participants across the three treatments at the three outcome assessment points. Descriptive scores for each variable are estimated marginal means (EMM) and standard errors (SE) derived from the mixed-models using all available data without imputation and controlling for baseline scores. Table 1 also shows the main effects for treatment across time and post hoc comparisons between treatments at each time point (i.e., treatment group by assessment point interactions). Mixed-models analyses revealed the treatments differed significantly on all the clinical variables, except for the two weight variables (BMI and weight change), across time with a consistent pattern: (1) CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ on any variable across time; (2) CBT+fluoxetine was significantly superior to fluoxetine-only on 6 of 9 variables; and (3) CBT+placebo was significantly superior to fluoxetine-only on 7 of 9 variables.2

Table 1.

Clinical Variables Across Treatments at Post-treatment, 6-Month Follow-up, and 12-Month Follow-up.

| Post-treatment | 6-Month Follow-up | 12-Month Follow-up | Main Effect for Treatment Across Time | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine | CBT plus Fluoxetine | CBT plus Placebo | Fluoxetine | CBT plus Fluoxetine | CBT plus Placebo | Fluoxetine | CBT plus Fluoxetine | CBT plus Placebo | CBT+Fluoxetine Versus Fluoxetine | CBT+Placebo Versus Fluoxetine | CBT+Fluoxetine Versus CBT+Placebo | ||||||||||

| Variable | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | EMM | SE | |||

| Binge episodes/month | 10.37a | 1.59 | 4.32b | 1.55 | 2.29b | 0.96 | 11.63a | 2.37 | 3.94b | 1.55 | 5.73b | 1.43 | 10.40a | 1.92 | 4.64b | 1.70 | 4.63b | 1.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.808 |

| Dietary Restraint | 2.49a | 0.25 | 1.60b | 0.26 | 1.45b | 0.25 | 2.88a | 0.31 | 1.70b | 0.30 | 1.56b | 0.28 | 2.40 | 0.30 | 1.90 | 0.29 | 2.37 | 0.27 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.847 |

| Eating Concern | 2.68a | 0.27 | 1.53b | 0.28 | 1.45b | 0.27 | 2.94a | 0.34 | 2.06ac | 0.33 | 1.85bc | 0.30 | 2.93a | 0.33 | 1.94b | 0.32 | 1.99b | 0.30 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.808 |

| Shape Concern | 3.93a | 0.27 | 2.96bc | 0.28 | 3.22ac | 0.27 | 4.45a | 0.34 | 3.24b | 0.33 | 3.74ab | 0.30 | 4.41a | 0.33 | 2.95bc | 0.31 | 3.57bc | 0.29 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.148 |

| Weight Concern | 3.29a | 0.25 | 2.32b | 0.25 | 2.64ab | 0.24 | 3.86a | 0.30 | 2.80b | 0.29 | 2.91b | 0.27 | 3.58a | 0.29 | 2.63bc | 0.28 | 3.03ac | 0.26 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.375 |

| Global Score | 3.09a | 0.22 | 2.14b | 0.23 | 2.19b | 0.22 | 3.52a | 0.27 | 2.50b | 0.26 | 2.50b | 0.24 | 3.32a | 0.26 | 2.40b | 0.25 | 2.73b | 0.24 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.637 |

| Depression (BDI) | 12.57a | 1.36 | 8.26b | 1.39 | 7.41b | 1.34 | 14.44 | 1.67 | 10.73 | 1.64 | 10.19 | 1.49 | 12.88 | 1.63 | 11.17 | 1.57 | 11.43 | 1.49 | 0.058 | 0.030 | 0.821 |

| Body mass index | 35.75 | 0.48 | 35.57 | 0.47 | 35.63 | 0.46 | 36.16 | 0.58 | 36.86 | 0.58 | 35.93 | 0.50 | 36.15 | 0.57 | 35.83 | 0.58 | 34.76 | 0.51 | 0.908 | 0.313 | 0.253 |

| Weight Loss (pounds) | -4.84 | 2.98 | -5.56 | 2.94 | -5.00 | 2.83 | -2.32 | 3.61 | -2.81 | 3.12 | -2.81 | 3.12 | -1.48 | 3.52 | -4.13 | 3.60 | -9.84 | 3.18 | 0.929 | 0.405 | 0.350 |

Note: CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy. EMM = estimated marginal mean calculated using mixed models; SE = standard error. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. Different superscripts indicate the groups differ significantly based on post hoc comparisons (i.e., significant group by assessment time interactions in the mixed models).

Discussion

This study examined the longer-term effects of fluoxetine and CBT either with fluoxetine (CBT+fluoxetine) or with placebo (CBT+placebo) for BED through 12-month follow-up after completing 4-month acute treatments within a randomized placebo-controlled trial (Grilo et al., 2005). This represents the first report from any randomized placebo-controlled trial for BED that has reported follow-up data after completing a course of medication-only treatment for BED. The findings extend our initial acute treatment findings (Grilo et al., 2005) regarding the effectiveness of CBT, but not fluoxetine, for BED to 12-months after treatment completion. Specific comparisons revealed a consistent pattern of findings that CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ on essentially any clinical variable whereas CBT (either with fluoxetine or placebo) was superior to fluoxetine-only on the majority of variables throughout the 12-month follow-up period.

Findings regarding the superiority of CBT+placebo over fluoxetine-only and that adding fluoxetine to CBT did not enhance outcomes compared to adding placebo to CBT are consistent with findings by Ricca et al. (2001). In their open-label trial, Ricca et al. (2001) found CBT was superior to both fluoxetine-only and fluvoxamine-only and the addition of either antidepressant to CBT did not enhance outcomes at either post-treatment or 12-month follow-up. Our findings also parallel those by Devlin et al (2007) that adding fluoxetine to behavioral weight loss did not enhance binge-eating outcomes either at post-treatment or through 24-month follow-up. Our 12-month follow-up findings represent further support for the longer-term durability of CBT for BED (Grilo et al., 2012; Hilbert et al., 2012; Ricca et al., 2001; Wilfley et al., 2002) and support the NICE (2004) guidelines regarding CBT as the best-established treatment. Our findings, however, that only 3.7% of BED participants treated with fluoxetine-only had remission at 12-month follow-up, call into question the advisability of treating BED with fluoxetine-only and run counter to the NICE (2004) guidelines, which were cautiously stated pending follow-up studies.

We observed the following binge remission rates (zero binges during past month) at 12-month follow-up: 3.7% for fluoxetine-only, 26.9% for CBT+fluoxetine, and 35.7% for CBT+placebo. No published follow-up studies have provided remission data for fluoxetine-only for BED so direct comparison is not possible. The observed reductions in frequency of binge-eating and differences between fluoxetine-only and CBT treatments are quite similar to those reported by Ricca et al.(2001) for fluoxetine-only versus CBT-only through 12-month follow-up. Our observed remission rate for CBT+placebo falls between rates reported at 12-month follow-up for CBT-only by randomized controlled trials (21% by Peterson et al. (2009), 33% by Agras et al. (1997), 51% by Grilo et al. (2011), and 59% by Wilfley et al. (2002)). The clear pattern of differences between treatments on continuous outcome variables also supports the superiority of CBT conditions over fluoxetine-only and indicate no advantage to adding fluoxetine to CBT.

None of the treatments produced significant changes in BMI, which represents an area of clinical concern for most patients with BED. CBT and other psychological treatments (Grilo et al., 2011; Wilfley et al., 2002) as well as most medication treatments (Reas & Grilo, 2008) for BED fail to produce meaningful weight losses even over the short term. Fluoxetine does not appear to have weight loss benefits; indeed, we observed that patients treated with CBT+placebo had significantly lower BMI at 12-month follow-up than patients treated with either fluoxetine-only or CBT+fluoxetine. One randomized placebo-controlled trial with obese BED patients found that adding orlistat (an anti-obesity medication) to CBT produced greater, albeit modest, weight loss than adding placebo to CBT and that the effects were maintained for three months after treatments (Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005). Finding ways to produce weight losses in obese patients with BED represents a pressing research need.

Although the lack of meaningful weight loss is disappointing, it is worth noting that participants at 12-month follow-up remained, on average, below their baseline BMI of 36.9. Recent research found that many patients with BED report gaining substantial amounts of weight prior to seeking treatment. Blomquist et al. (2011) found that treatment-seeking patients with BED reported an average 15.1 pound weight gain during the prior year. Thus, perhaps the modest BMI changes represent an important interruption of a steep weight-gain trajectory. Post-treatment binge remission was associated with greater BMI loss through 6-, but not 12-months.

Our findings pertain to persons with BED who participated in a randomized placebo-controlled trial at a university medical center, and may not generalize to different clinical settings, treatment methods, or to persons not willing to take medications or receive CBT. In “real-world” clinical settings, it is possible that participants who showed some response or remission from binge eating with fluoxetine-only would have continued taking the medication which may have changed the observed outcomes at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Most participants were female, white, well-educated, and without diabetes or thyroid problems and the findings may not generalize to more diverse patient groups with different characteristics. Future studies should examine patient characteristics (e.g., self-efficacy) and intervening events (e.g., stressful events) that may be associated with longer-term outcomes of maintenance and relapse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health Grants R01 DK49587 and K24 DK070052.

Footnotes

Exploratory analyses revealed that post-treatment remission from binge eating was associated significantly with greater BMI loss from baseline through 6-month follow-up (t(2)=2.536, p=0.014) but only marginally through 12-month follow-up (t(2)=1.751, p=0.086) while remission from binge-eating at 12-month follow-up was associated significantly with greater BMI loss from baseline through 12-month follow-up (t(2)=2.179, p=0.034).

Post hoc comparisons of treatments at each post-treatment and follow-up time-points revealed consistent patterns: (1) CBT+fluoxetine and CBT+placebo did not differ on any of the variables at any of the time-points; (2) CBT+fluoxetine was significantly superior to fluoxetine on 7 of 9 variables at post-treatment, and on 5 of 9 variables at both the 6-month and 12-month follow-ups; and (3) CBT+placebo was significantly superior to fluoxetine on 5 of 9 variables at post-treatment, on 6 of 9 variables at 6-month follow-up, and on 4 of 9 variables at 12-month follow-up.

Contributor Information

Carlos. M. Grilo, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Department of Psychology, Yale University

Ross D. Crosby, Departments of Biostatistics and Clinical Neuroscience, Neuropsychiatric Research Institute and the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences

G. Terence Wilson, Department of Psychology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Robin M. Masheb, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine.

References

- Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, Eldredge K, Marnell M. One-year follow-up of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obese individuals with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:343–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R. Manual Revised Beck Depression Inventory. Psychol Corp.; NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Blomquist KK, Barnes RD, White MA, Masheb RM, Morgan PT, Grilo CM. Exploring weight gain in year before treatment for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:435–439. doi: 10.1002/eat.20836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Liu L, Walsh BT. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for binge eating disorder: 2-year follow-up. Obesity. 2007;15:1702–09. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. Guilford; NY: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Version. (SCID-I/P) NYSPI; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge-eating disorder: comparative study with overweight and bulimia nervosa. Obesity. 2010;18:499–504. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:675–685. doi: 10.1037/a0025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Bishop M, Stein R, Wilfley DE. Long-term efficacy of psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200:232–237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.089664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope H, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Eating Disorders – Core Interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, related eating disorders. NICE Clinical Guideline No. 9. NICE; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire in binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, et al. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2001;70:298–306. doi: 10.1159/000056270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein R, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Treatment of binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatments of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]