Abstract

HIV/AIDS is a major public health problem in Cameroon and Africa, and the challenges of orphans and vulnerable children are a threat to child survival, growth and development. The HIV prevalence in Cameroon was estimated at 5.1% in 2010. The objective of this study was to assess the burden of orphans and vulnerable children due to HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. A structured search to identify publications on orphans and other children made vulnerable by AIDS was carried out. A traditional literature search on google, PubMed and Medline using the keywords: orphans, vulnerable children, HIV/AIDS and Cameroon was conducted to identify potential AIDS orphans publications, we included papers on HIV prevalence in Cameroon, institutional versus integrated care of orphans, burden of children orphaned by AIDS and projections, impact of AIDS orphans on Cameroon, AIDS orphans assisted through the integrated care approach, and comparism of the policies of orphans care in the central African sub-region. We also used our participatory approach working experience with traditional rulers, administrative authorities and health stakeholders in Yaounde I and Yaounde VI Councils, Nanga Eboko Health District, Isangelle and Ekondo Titi Health Areas, Bafaka-Balue, PLAN Cameroon, the Pan African Institute for Development-West Africa, Save the orphans Foundation, Ministry of Social Affairs, and the Ministry of Public Health. Results show that only 9% of all OVC in Cameroon are given any form of support. AIDS death continue to rise in Cameroon. In 1995, 7,900 people died from AIDS in the country; and the annual number rose to 25,000 in 2000. Out of 1,200,000 orphans and vulnerable children in Cameroon in 2010, 300,000(25%) were AIDS orphans. Orphans and the number of children orphaned by AIDS has increased dramatically from 13,000 in 1995 to 304,000 in 2010. By 2020, this number is projected to rise to 350,000. These deaths profoundly affect families, which often are split up and left without any means of support. Similarly, the death of many people in their prime working years hamper the economy. Businesses are adversely affected due to the need to recruit and train new staff. Health and social service systems suffer from the loss of health workers, teachers, and other skilled workers. OVC due to HIV/AIDS are a major public health problem in Cameroon as the HIV prevalence continues its relentless increase with 141 new infections per day. In partnership with the Ministry of Social Affairs and other development organizations, the Ministry of Public Health has been striving hard to provide for the educational and medical needs of the OVC, vocational training for the out-of- school OVC and income generating activities for foster families and families headed by children. A continous multi-sectorial approach headed by the government to solve the problem of OVC due to AIDS is very important. In line with the foregoing, recommendations are proposed for the way forward.

Keywords: AIDS, AIDS orphans, Cameroon, care, Central Africa, HIV, orphans, OVC effort index, prevalence, support, vulnerable children.

INTRODUCTION

HIV and AIDS have created humanitarian and developmental crisis of unprecedented scale in the developing world where 132 million people have lost one or both parents due to the AIDS pandemic and 25 million children have been orphaned by HIV/AIDS in 2010 [1]. More than two decades into the AIDS pandemic, a cure for the disease has not yet been found and the negative impact of adult AIDS mortality on child welfare has been potentially massive [2]. Moreover, the impact of HIV and AIDS on rural livelihoods is insidious [3]. There is fear that OVC will obtain less education, thereby worsening their own life chances, as well as the long-term economic prospects of their countries [2]. UNICEF [4] indicated that poverty is contributing to low school attendance, low completion rates and low learning outcomes. Similarly, Curley et al., [5] argued that it is difficult to obtain an education if children live in poverty and lack resources and access to opportunities, although education is a key factor to overcoming poverty and AIDS. HIV and AIDS have ushered in the concept of AIDS orphans which is negatively affecting the development and future of African children.

A child made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS is one who is below the age of 18 and meets one or more of the following criteria: has lost one or both parents/caregivers, has a chronically ill parent/caregiver, lives in a household where in the past 12 months at least one adult died or was seriously ill for an extended period of time, lives outside of family care (i.e. lives in an institution or on the streets), faces many problems (increase in poverty due to death of parents, loss of family and identity, lack of adequate adult support, increased risk of labour and sexual exploitation, fewer opportunities for education, loss of access to health care because of poverty, poor nutrition and malnutrition, and homelessness and vagrancy) [1, 2, 5, 6].

The prevalence of HIV in Cameroon was 5.1% in 2010 with significant regional discrepancies; two thirds of those currently infected are youths and 60% of annual infections fall within this category of citizens [7]. The estimated number of people living with HIV and AIDS for 2002 was 920,000, of which 69,000 were children (compared to 22,000 in 1999) between 0-14 years and 860,000 were aged 15-49years including 500,000 women [8]. HIV and AIDS pose serious social, cultural and economic hardship to its victims including orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) [9]. In 1995, 7,900 people died from AIDS in Cameroon; and the annual number rose to 25,000 in 2000. Out of 1,200,000 orphans and vulnerable children in Cameroon in 2010, 300,000(25%) were AIDS orphans [10]. Other orphans and the number of children orphaned by AIDS have increased dramatically from 13,000 in 1995 to 304,000 in 2010 [10]. By 2020, this number is projected to rise to 350,000. OVC due to HIV/AIDS are a major public health problem in Cameroon [9] as the HIV prevalence continues its relentless increase with 141 new infections per day [10]. In this study, we assessed the burden of AIDS orphans in Cameroon where the infection rate is still on the increase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cameroon

Cameroon is situated in Central West Africa, north of the Equator. The country is bounded on the North by Chad; on the South by Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Congo; on the West by Nigeria and on the East by the Central African Republic. Cameroon has a surface area of about 475,442 km2 and a population of about 18 million people with an annual growth rate of about 2.8%[11]. Cameroon is undergoing a demographic transition and about 50% of the population now live in urban areas. Administratively, the country is divided into 10 regions headed by governors. Each region is divided into divisions and subdivisions. Yaounde is the administrative capital while Douala is the economic capital. The average income per capita over the last five years ranges from US$ 600-650 [11].

The strong political will of the Government of Cameroon has been instrumental in the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The health system is decentralised and a multi-sectorial approach was adopted by the government to fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In partnership with other development organizations, the Government has made considerable effort in the fight against HIV/AIDS. For example, the continuous decrease in the prices of ARV in Cameroon: 1999: 700 - 1000$ /patient/month; 2001: 300-600 patients on ART; 2005: 2,5$/patient/month: 15 000 patients on ARV and since May 1st 2007, there is free access to ART [12].

The Ministry of Public Health co-ordinates all health services in the country. The health system is organized into the central, intermediate and peripheral levels [11]. The Central level that outlines policies has three reference health institutions of Category I and three of Category II. At the Intermediary level are ten regional delegations of public health, ten regional Technical Groups for AIDS Control and nine regional hospitals and affiliated health structures which coordinate policy implementation. Peripheral institutions are health districts which implement health policies. In 2002, there were 150 such health districts and 1,388 health centers [13]. Currently there are an estimated 179 health districts in the country. Some health facilities are private institutions and others are faith-based. There is a national emphasis on preventive health services which are available throughout the country to complete this national health structure [11]. The national social insurance scheme in Cameroon does not cover the health service even though private health insurance schemes are timidly being introduced since three years ago; patients have to pay for every aspect of services rendered.

Study Methods

A structured search to identify publications on orphans and other children made vulnerable by AIDS was carried out. A traditional literature review on google, PubMed and Medline using the keywords: orphans, vulnerable children, HIV/AIDS and Cameroon was conducted. To identify potential AIDS orphans publications, we included papers on HIV prevalence in Cameroon, institutional versus integrated care of orphans, burden of children orphaned by AIDS and projections, impact of AIDS orphans on Cameroon, AIDS orphans assisted through the integrated care approach, and comparism of the policies of orphans care in the central African sub-region and Africa.

The key journals reviewed were: Journal of AIDS and HIV Research, Children and Youth Services Review, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome and Human Retroviruses, OCEAC Bulletin, AIDS Information Bulletin, Journal of African Policy Studies, AIDS, British Medical Journal, Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services, Lancet, Lancet Infectious Diseases, Journal of Infectious Diseases, International Journal of Epidemiology, and Bulletin of the World Health Organisation. We also reviewed World Bank publications, UNICEF publications, text books on HIV/AIDS, Ministry of Public Health publications and reports, UNAIDS reports, technical and workshop reports. Demographic and Health Surveys, and conference preceedings were also reviewed. We also accessed and retrieved data from websites. Reference lists for important AIDS orphans publications were also scanned.

We used our working experience on participatory approach among traditional rulers, administrative authorities and health stakeholders on OVC in Yaounde I and Yaounde VI Councils [14,15], Nanga Eboko Health District, Isangelle and Ekondo Titi Health Areas [9], and Bafaka-Balue community [6]. Our working experience on OVC with PLAN Cameroon, the Pan African Institute for Development-West Africa, Save the Orphans Foundation, Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Public Health and the National AIDS Control Committee facilitated our work.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

HIV/AIDS, Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Cameroon

The first AIDS cases were reported in Cameroon in 1985 and in 1995, 2766 cases had been notified with a cumulative number of 8,141 [16]. Similarly the HIV prevalence in Cameroon has progressively risen from 0.4% in 1987 to 1.2% in 1990 [17] and from 4% in 1992 [18] to about 7% in 1997, to 11% in 2000 [19] and in 2008, the national prevalence was 5.5% based on a Demographic and Health Survey carried out in 2004 [20].

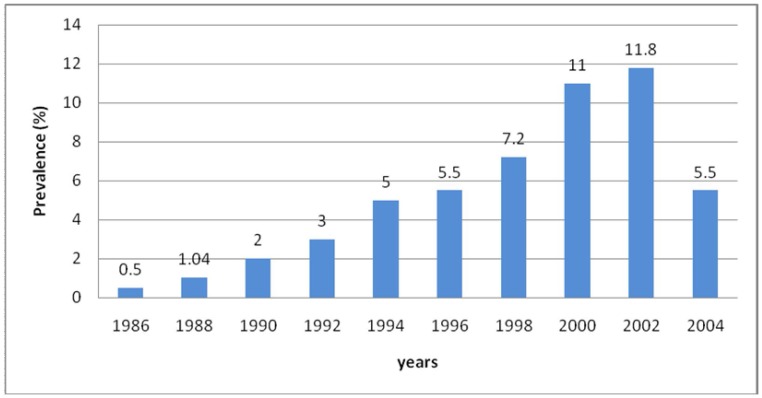

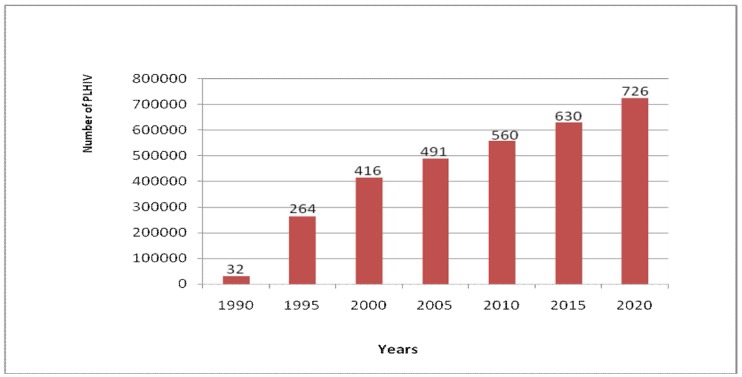

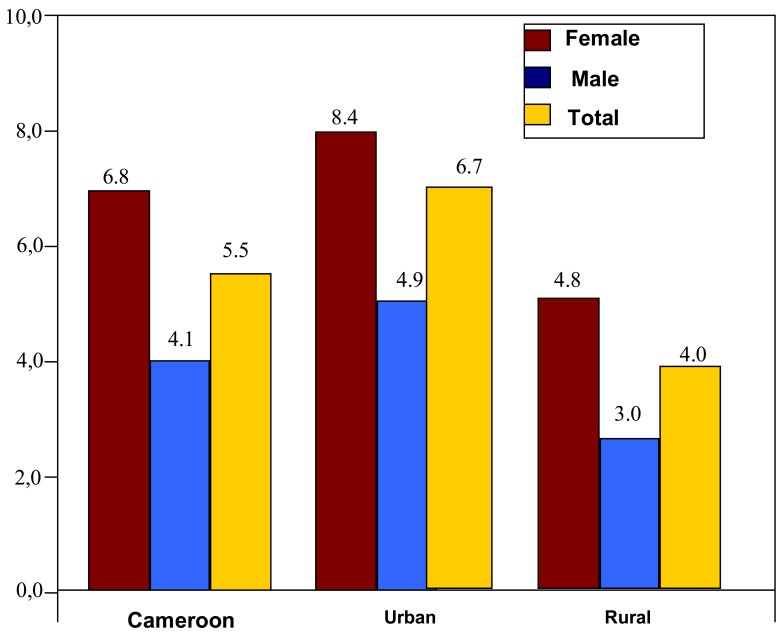

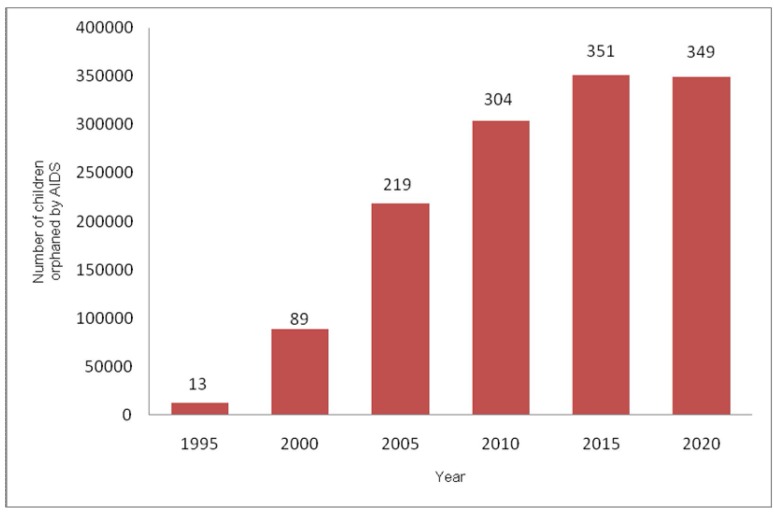

In 2004, a decrease to 5.5% in HIV prevalence was observed. This is explained by the fact that the data from 1987 to 2002 was obtained from sentinel surveillance sites in antenatal clinics throughout the nation, whereas in 2004 it was a demographic and health survey of various strata of the general population, including university students, commercial sex workers, long distance drivers among others [11]. HIV Transmission is mainly heterosexual (90%) with the blood and vertical routes being 5% respectively [11]. Fig. (1) shows the evolution of HIV in Cameroon from 1986 to 2004 [11] while Fig. (2) presents the projection of the total population of people living with HIV from 1990-2020 [10]. Fig. (3) shows the national HIV prevalence and urban/rural variations in Cameroon [21]. Fig. (4) shows the projection of children orphaned by AIDS, under age 18, from 1995-2020 [22].

Fig. (1).

Evolution of HIV prevalence in Cameroon (1986-2004) (Source [11]).

Fig. (2).

Projection of the total population of people living with HIV in Cameroon, 1990-2020 (Source [10]).

Fig. (3).

Urban and rural seroprevalence of HIV in Cameroon in 2006 (Source [21]).

Fig. (4).

Projection of children orphaned by AIDS, under age 18, from 1995-2020, in Cameroon (Source [22]).

Cameroon ‘s adult HIV prevalence (percentage of population ages 15-49 years who are HIV positive) has gone from 0.6% in 1990 to 5.1% in 2010 (Figs. 1, 2) [10]. More women than men are infected with HIV and people living in urban settings are more infected than rural dwellers (Fig. 3). According to the NACC [10], the many factors that contribute to the spread of HIV in Cameroon include multiple sexual partners, low condom use, low status of women (with few economic opportunities and great power differential with men, women do not have the power to demand safer sex), high prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections which facilitate HIV transmission through unprotected sexual relations, and harmful socio-cultural practices. The principal mode of transmission of HIV infection in Cameroon is through sexual intercourse where about 90% of new infections are estimated to occur as a result of sexual relations. Multiple partners and non-use of condoms increase the risks of HIV transmission. About 6 % of new infections were from mother-to-child transmission (in 2010, 7,300 babies were estimated to be born HIV positive due to mother-to-child transmission), and about 4% of new infections come from blood supply and other accidental transmissions [10].

In the earlier years of the AIDS pandemic, more than 70% of infected people were aged between 20 and 39 years [17], the work force of the country. Today, youths are still the most infected and those in the 15-24 year age group are hard hit, with infected girls constituting 10-15%, compared to 4-6.5% boys of the same age. There is no doubt that the socio-economic impact of HIV/AIDS on Cameroon is profound with growing numbers of sectors being affected, and high hospital bed occupancy rampant, resulting in an overstretched medical personnel and an extra burden to the health system. School teachers are reported to be unproductive on several counts and morbidity is high from opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis [11]. Furthermore, there is a rising number of orphans from the HIV pandemic, with 122,670 cases reported in 2005 [23].

Care of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Cameroon

In partnership with the Ministry of Social Affairs and other development partners, the Ministry of Public Health has been striving hard to care for HIV/AIDS orphans and other vulnerable children. The major focus has been on the identification of these OVC. Some of the activities carried out include the provision of psychosocial support like counseling to children and to families or caregivers [24]. There have also been education and training through the sponsorship of children in schools and vocational training and life skills development including nutrition, education to children and their caregivers. Medical care and awareness to ensure adherence to drug regimens prescribed in health facilities are also carried out. Legal support to help link children with legal departments and human rights organizations and to help them obtain a birth certificate has been carried out. Some economic empowerment for sustainability to caregivers through income generating activities have been implemented. Many partner NGOs have been carrying out advocacy training to empower OVC to fight for themselves and their rights and providing material support for necessities such as clothing, shoes, food, etc [24].

A 2009 UNICEF [25] report shows that 525 caretaker families of OVC were supported to start and/or to enhance ongoing income generating activities through financial support. These were mostly petty trade, animal husbandry and production of food crops. Beneficiaries were trained on micro finance mechanisms (loans and savings) and are affiliated to local cooperative and credit unions.

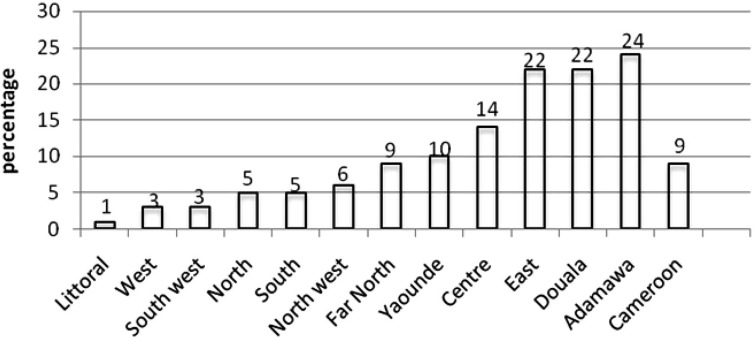

All the examples cited are from isolated projects by different development partners or the government. The 2006 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey [26] shows that only 9% of all OVC on the national territory have been given any form of support. The results presented in Fig. (5) indicate that the Adamawa and East Regions had the highest support while the Littoral, West and South West Regions had less than 3% of OVC benefitting from any form of support.

Fig. (5).

Proportion of Orphans and vulnerable children that benefitted from any type of support (Multiple indicator cluster survey, 2006) in Cameroon per locality.

Impact of AIDS Orphans on Cameroon

The death toll from AIDS continues to rise in Cameroon. AIDS-related deaths profoundly affect families, which often are split up and left without any means of support. Similarly, the death of many people in their prime working years hampers the economy. Businesses are adversely affected due to the need to recruit and train new staff. Health and social service systems suffer from the loss of health workers, teachers, and other skilled workers [10]. Orphans and the number of children orphaned by AIDS-children under age 18 who have lost one or both parents to AIDS-has increased dramatically, rising from 13,000 orphans in 1995 to 304,000 in 2010. By 2020, this number is projected to rise to 350,000 (Fig. 4). Children orphaned by AIDS represented about 25 percent of Cameroon’s total 1,200,000 orphans in 2010 [10].

Providing appropriate support and care for OVC poses challenges for both families and society. In Cameroon, many OVC live outside of family support, and many are marginalised, stigmatised, and discriminated against. Consequently, they are exposed to harmful conditions such as lack of schooling, illiteracy, begging, pedophilia, juvenile delinquency, prostitution, and the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections [10].

The integrated care of orphans and other disadvantaged children in their natural environment in African settings is an old practice but this is different from institutional care of OVC where community link is absent. With the advent of HIV and AIDS and resultant deaths, the number of OVC has increased beyond a rate which the traditional African society cannot cope [9]. It is important that OVC live in their natural environment, hence the need to strengthen the capacity of families and communities to provide quality family-based care and support for OVC. The emerging consensus of opinion is that extended families and communities are the first line of defense in the orphan crisis and that families are almost always the best place for the child. Primary interventions should be centered on building the capacities of families to care for OVC. Residential orphan care is the least desirable option for children because orphan care institutions are inherently anti-community. As a result, institutional care is increasingly under scrutiny and has been branded the last resort in a spectrum of interventions for OVC care [27].

The integrated care of OVC constitute a major part of the UN Convention on the rights of the Child [28] and the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDG) [29]. The integrated care approach helps OVC to cope with the social stigma of the disease and its economic consequences and adapt to their natural environment. Fig. (6) shows two Cameroonian OVC living in an institutional care and in an integrated community scheme. Cameroon’s first strategic plan on HIV and AIDS started in 1986 but it was not until 2006 that OVC were integrated into the policy with assistance from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria [9]. The Government of Cameroon is committed to the integrated care of OVC as demonstrated by the ratification of many treaties including the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child [9].

Fig. (6).

Cameroonian OVC in an integrated care foster family [4] (a) and in an orphanage (b) (Source [38]).

In Africa, a large number of children do not live with their biological parents and are not raised by them; they are often fostered by the extended family. In Senegal, for example, child fostering is very common as 25% of children under age 15 do not live with their biological parents and 35% for children of the 10-14 age group [30]. In Cameroon, the proportion of foster children is estimated at 22% [31]. The placement of children within the kinship network and through connections is a long-standing and frequent practice in Africa. Thus, many children, when they become orphans, did not necessarily live with their biological parents. Even if a child lives with his or her biological parents and if one of them dies, he or she may not be considered an orphan because the traditional rules governing African societies facilitate the care of these children in particular through the movement of these children within the kinship systems. Locoh [31] pointed out that:

”the care of related children has always been a means to handle health crises and to protect children if their parents die. This is the case with the AIDS pandemic. Grandparents—but also uncles, aunts, and older siblings—are in the front line to assume the care of orphans. The movement of children between various related households is not restricted to orphans. It is a very common practice, which makes the child part of the extended family circle and not exclusively raised by his or her biological parents”.

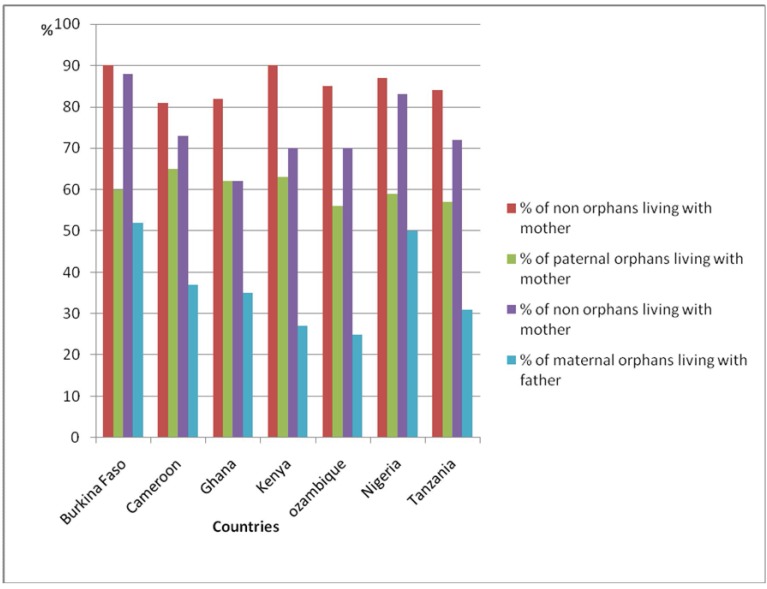

Cameroon OVC Situation Compared with Other African Countries

According to UNAIDS estimates, there were 390000 OVC in Cameroon with an HIV prevalence of 5.5% in 2008 [8]. The care of OVC in Cameroon is a major public health problem. Children without the guidance and protection of their parents are often more vulnerable and at risk of becoming victims of violence, exploitation, trafficking, discrimination and other abuses [9]. The Cameroon OVC situation is similar to that of many African countries (Fig. 7). For example, Zimbabwe has been severely affected by the HIV and AIDS pandemic with approximately 1,200,000 OVC where it is predicted that the number will increase over the next ten years. In response to the problem, a National Orphan Care Policy to support traditional methods of care and discouraged forms of care which removed children from their communities and culture was developed. This policy recommended foster care and adoption as the desired alternatives for children who did not have extended families and explicitly discouraged the use of institutional care. It clearly stated that placing a child in an orphanage should be regarded as a last resort, utilized only after all efforts to secure a better form of care have been exhausted [32]. In Nigeria, community-based approaches for community mobilization and for OVC care and support have been developed over 14 years with support from public and private donors, including USAID; the community mobilization approach, recognized as ‘best practice’, promotes community reflection around OVC needs and concerns and helps communities plan and implement appropriate and sustainable activities to support its children and little external support is needed. The Nigeria OVC care and support approach is based on the Siyawela model, which facilitates the development of support groups for OVC within existing community structures such as primary health clinics, and promotes multi-level OVC care and support through community resource mobilization and local stakeholder participation. Sub-grants are provided to selected community groups to build capacity and scale up care and support to OVC [33].

Fig. (7).

Living situations of orphans and non-orphans in Cameroon and selected African Countries in 2004 (source [37]).

In Zambia, the government, in collaboration with the UN system, NGOs and local communities have defined a minimum package of services for vulnerable children to access education in community schools comprising quality education, health, food and nutrition, school-based agricultural support, income generating activities, HIV and AIDS behaviour change communication strategies, educational materials, recreational activities combined with life skills training, training and empowerment of parent-teacher school committees and psychosocial support [34]. In Mali, AIDS has orphaned 94000 children where they are often raised by grand parents or families headed by them; many children lose their childhood and are forced by circumstances to be producers of income, food and caregivers of sick family members [35]. In Cameroon, the practice of community care of OVC is very common and the government in collaboration with the Global Fund, bilateral and multilateral organizations and NGOs is supporting local communities to enhance their capacity to care for OVC including the creation of income generating activities which is the backbone of community ownership and sustainability. The integrated care of OVC has proven to be feasible in Cameroon [9, 14, 15, 36]. In Cameroon, the support given to orphans and vulnerable include psycho-social counseling, medical care, nutritional needs, educational needs, income generating activities and vocational rehabilitation [9].

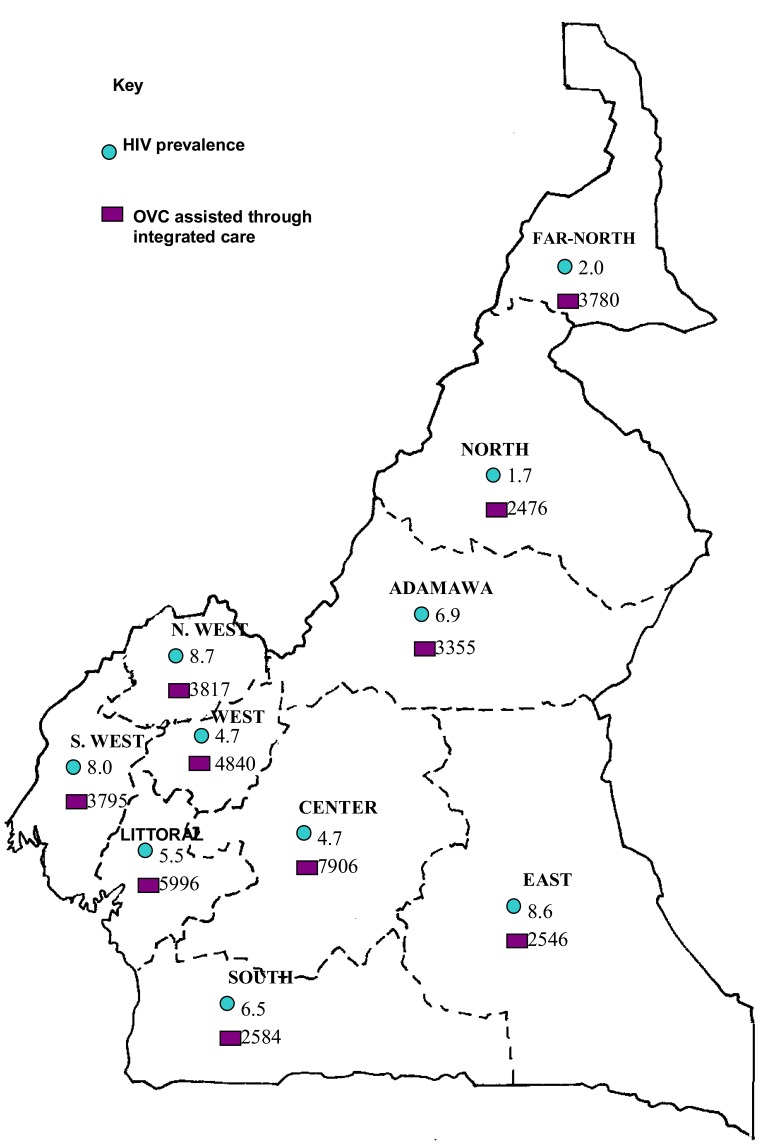

Fig. (6) shows the living conditions of Cameroon OVC in a foster home and in an orphanage [36]. Fig. (7) shows the living situations of orphans and non-orphans in Cameroon and selected African Countries in 2004 [37]. Fig. (8) presents the regional HIV prevalence and number of OVC assisted through the integrated care approach in Cameroon in 2007 [39]. From Fig. (7), the North West, South West and East Regions have the highest HIV prevalence in the country meanwhile, they have the lowest number of OVC assisted through integrated care compared to the Center, West, and Littoral Regions presenting the lowest prevalence but benefiting from an increased number of OVC being taking care. This may be due to the presence of more intervening NGOs with many urban settings in these regions. More efforts is needed to improve on the care of OVC in the other regions in terms of sensitization in order to reduce the HIV prevalence, and decrease the number of OVC being cared for.

Fig. (8).

HIV seroprevalence per Region and the number of OVC assisted through the integrated care approach in Cameroon in 2007 (Source [39]).

The burden of OVC in Cameroon compared with other Central African countries are shown in Tables 1-3 [40,41,42]. Table 1 [40] shows that the OVC programme effort index covers the OVC national situation, an analysis of the consultative process, the coordination plan, the policy, legislative review, monitoring and evaluation plan, needed resources and the programme response to the crisis. The OVC programme effort index consists of 120 simple questions that were asked to task forces on orphaned and vulnerable children in 36 countries. An example of the index can be found in a guide to monitoring and evaluation of the national response for children orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV and AIDS [42]. Compared with other countries in the Central African Sub-Region, the Cameroon national situation is very low with respect to Chad, Gabon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo implying that HIV is more a serious public health problem in these other countries. However, the national action plan for Cameroon on the OVC effort index is lower (36) than that of the Central African Republic (97) and Gabon (81). This means that the national action plan for Cameroon on the OVC effort index is not very aggressive in providing care for AIDS orphans and this has been reflected in a weak policy rating of 8 on the OVC effort index compared to countries like Central Africa Republic (68), Congo (73), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (58). In all the countries compared, the OVC effort index for legislative review and monitoring and evaluation were very low with none scoring above 50%. Without any meaningful legislative review, support to OVC cannot be effective because extended families will continue to grab the property of the children. The major weaknesses of the Cameroon response to the OVC based on the effort index are monitoring and evaluation (5) and resources (25). With limited resources and low monitoring and evaluation, the support given to the OVC may not be well managed or what was designated for OVC may not get to them. This OVC effort index also relates to whether the birth of the child is registered or not.

Table 1.

Government Response to Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Cameroon and the Central African Sub-Region in 2005

| OVC Programme Effort Index (Out of 100) 1999-2004 | Birth Registration (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries in Central Africa | National Situation | Analysis Consultative Process | Coordinating Plan | National Action Plan | Policy | Legislative Review | M & E | Resources | Total OVC Index Score | Total | Urban | Rural |

| Cameroon | 33 | 28 | 60 | 36 | 8 | 18 | 5 | 25 | 27 | 79 | 94 | 73 |

| CAR | 8 | 68 | 20 | 97 | 68 | 30 | 14 | 70 | 47 | 73 | 88 | 63 |

| Chad | 86 | 28 | 0 | 26 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 26 | 25 | 53 | 18 |

| Congo | 13 | 51 | 84 | 65 | 73 | 0 | 17 | 48 | 44 | - | - | - |

| DRC | 59 | 72 | 20 | 59 | 58 | 20 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 34 | 30 | 36 |

| EG | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 7 | 53 | 14 | 32 | 43 | 24 |

| Gabon | 82 | 78 | 30 | 81 | 13 | 0 | 24 | 55 | 45 | 89 | 90 | 87 |

| STP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70 | 73 | 67 |

CAR: Central African Republic, DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo; STP: Sao Tome and Principe; EQ: Equatorial Guinea, M& E: Monitoring and Evaluation.

Source [40].

Note: The OVC programme effort index measures the policy and the programme response to the crisis facing orphans and vulnerable children. It consists of 120 simple questions that were asked to task forces on orphaned and vulnerable children in 36 countries. An example of the index can be found in A Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation of the National Response for Children Orphaned and Made Vulnerable by HIV and AIDS(UNICEF et al., 2005).Based on self- reported responses.

-Indicates no data available.

Table 3.

School Attendance, Female Headed Families and Residence Pattern of Non-Orphans and Orphans in Cameroon and Other Countries in Central Africa in 2005

| School Attendance (10-14 Years Old) | Female Headed Households | Residence Patterns for Non-Orphans and Orphans | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries in Central Africa | % Non-Orphans (Children Living with at Least One Parent) Attending School | % Double Orphans Attending School | Double Orphans/ Non-Orphans School Attendance Ratio | % All Households with Children that are Female Headed | % Households with Orphans that are Female Headed | % Households with Children that are Female Headed taking Care of Orphan(s) | % Non Orphans Living with Mother | % Paternal Orphans Living with Mother | % Non-Orphans Living with Father | % Maternal Orphans Living with Father |

| Cameroon | 85 | 83 | 0.99 | 46 | 23 | 31 | 81 | 72 | 73 | 51 |

| CAR | 54 | 49 | 0.91 | 32 | 14 | 47 | 88 | 69 | 82 | 50 |

| Chad | 61 | 59 | 0.96 | 38 | 18 | 33 | 89 | 68 | 81 | 52 |

| DRC | 70 | 50 | 0.72 | 29 | 13 | 39 | 90 | 72 | 80 | 56 |

| EG | 89 | 85 | 0.95 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 81 | 78 | 56 | 40 |

| Gabon | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77 | 76 | 53 | 52 |

| STP | - | - | - | 46 | 31 | 11 | 88 | 84 | 59 | 43 |

Source [42]: Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys and Demographic and Health Surveys, 1998-2005.

Compared to other Central African countries, the number of AIDS orphans in Cameroon in 2005 was 240000(24%) with respect to Central African Republic (42.4%), Chad(9.5%), and Congo (40.7%) and the 2010 projection are shown in Table 2 [41]. Countries like Chad and Equatorial Guinea may suffer from underreporting of the AIDS orphans crisis. From Table 2, children are defined as maternal (mother is dead) or paternal (father is dead) orphans regardless of the survival status of the other parent. Thus, the estimates of maternal and paternal orphans include double (mother and father are dead) orphans. As shown in Table 2, the total number of orphans equals maternal orphans plus paternal orphans minus double orphans.

Table 2.

Estimated Number of Orphans in Cameroon and the Central African Sub-Region by Country, Type, in 2005 and Projections for 2010.

| Total Orphans, 2005 | Orphans by Type, 2005 | Projections for 2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries in Central Africa | Total Number of Orphans | Number of Orphans Due to AIDS | Maternal Orphans | Paternal Orphans | Double Orphans | Children Orphaned in 2005 | Total Number of Orphans in 2010 |

| Cameroon | 1000000 | 240000 | 540000 | 660000 | 180000 | 120000 | 1100000 |

| CAR | 330000 | 140000 | 180000 | 220000 | 76000 | 38000 | 360000 |

| Chad | 600000 | 57000 | 280000 | 410000 | 84000 | 76000 | 730000 |

| Congo | 270000 | 110000 | 140000 | 180000 | 48000 | 30000 | 300000 |

| DRC | 4200000 | 680000 | 2100000 | 2800000 | 800000 | 450000 | 4600000 |

| EG | 29000 | 5000 | 14000 | 20000 | 5000 | 3000 | 32000 |

| Gabon | 65000 | 20000 | 32000 | 41000 | 8000 | 9000 | 75000 |

Source [41].

Note: Numbers may not add up due to rounding. Children are defined as maternal or paternal orphans regardless of the survival status of the other parent. Thus the estimates of maternal and paternal orphans include double orphans. The total number of orphans = maternal orphans + paternal orphans - double orphans.

Table 3 [42] shows the percentage of double orphans attending school, the percentage of households with orphans that are female headed and the percentage of maternal/paternal orphans living with father/mother in Cameroon compared with other countries in Central Africa. Cameroon has the highest percentage (85%) of double orphans attending school compared to Central African Republic (49%) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (50%). The priority placed on children’s education is clearly evident in Cameroon’s Progressive National Primary Education Policy, with awareness of the importance of sending children to school growing, particularly after independence in 1960. Net primary school enrollment had only increased from 73.6% to 75.2% in 2001 during the MDG baseline years [43]. The government-supported increase to the current 85% enrollment level was facilitated by eliminating primary school fees [44]. The incorporation of HIV/AIDS lessons into the primary school curriculum is intended to contribute in fighting against the pandemic and give the children a future with hope [9, 45].

Other Causes of Death in Sub-Saharan Africa Other than HIV/AIDS

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a new HIV infection every 9seconds and every 13 seconds, somebody dies of AIDS [46]. AIDS is therefore, a major cause of death in Africa including other endemic diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. HIV/AIDS is a major public health concern and cause of death in Africa. Although Africa is home to about 14.5% of the world's population, it is estimated to be home to 67% of all people living with HIV and to 72% of all AIDS deaths in 2009 [47]. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [47] has predicted outcomes for the sub-Saharan region to the year 2025. These range from a plateau and eventual decline in deaths beginning around 2012 to a catastrophic continual growth in the death rate with potentially 90 million cases of infection. AIDS death are perculiar in that they occur on epidemic proportions compared to deaths due to other causes on the continent.

For example, in an extensive study, Jamison et al., [48] have identified the diseases that cause mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. The estimated regional death toll from HIV/AIDS for Sub-Saharan Africa was 2.2 million deaths in 2002 [49]. Armed conflicts resulted in an overall death toll of about 77,000 in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2001 [50]. According to Mather et al., [51], the Global Burden of Diseases 2000 Study estimated that 572,000 deaths were due to cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Williams and colleagues [52] estimated a total of 794,000 deaths due to acute respiratory infection in the region in 2000. Crowcroft and colleagues [53] estimated 170,000 deaths due to whooping cough in the African region in 1999 while Stein and colleagues [54] estimated a total of 452,000 deaths due to measles in the same region in 2000, of which approximately three-quarters were among children under five. Morris et al., [55] estimated that about 20 percent of all under-five deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa were caused by diarrhea. According to WHO [56] estimates, every thirty seconds, a child below five dies from malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. Hill et al., [57] predicted a total of 272,500 maternal deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa for 1995.

Limitations to HIV/AIDS and OVC care in Cameroon

Even though the health care system in Cameroon is decentralised, structural factors limiting the effectiveness of decentralization in access to ARV are evident. Difficulties in the provision of ARV drugs and reagents for CD4 examinations lead to disruptions in supply. There is also the problem of insufficient quantitative and qualitative human resources specifically of highly qualified staff (doctors and social workers) is aggravated by the poor distribution of these workers throughout the country (urban concentration-notably in the economic and administrative capitals of Yaoundé and Douala)[12].

Although there is insufficient number of physicians, no task shifting strategy has been developed by the health ministry. This situation lead in some treatment centers to non- organized and strong task shifting from physicians to nurses which have a negative impact on the quality of care, while well organized task shifting don't have negative impact. There is also a loss of motivation at a human resource level, because of the precariousness of one status, low salaries and difficult working conditions (high work load, insufficient technical means, etc) [12].

The care of AIDS orphans is still a major problem because the Ministry of Public Health still depend much on NGO for the exact number. The provision of educational, nutritional, vocational and medical needs including income generating activities to OVC and their families are still unattended to.

CONCLUSION

Orphans and vulnerable children due to HIV/AIDS are a major public health challenge in Cameroon as the HIV prevalence continues its relentless increase with 141 new infections per day. A continuous multi-sectorial approach headed by the Cameroon government to solve the problem of OVC is very important. These actions require stronger and continual leadership by public and private sector officials. The strong political leadership manifested by the government is essential to mitigate the impact of OVC due to AIDS. The provision of educational, medical, nutritional, vocational and income generating acivities to these unfortunate children will enable them to prevent themselves from HIV and face the future with dignity and hope.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE WAY FORWARD

Partnership with foreign bodies has boosted Cameroon’s fight against HIV, as seen in the decrease in the cost of anti-retroviral drugs and increase free HIV screening over the years [6]. This has helped the country to fight the pandemic by increasing the general life expectancy from 49.85 to 52.9years and favouring economic growth since HIV is more prevalent in youths [6, 43]. Partnership development to improve the quality of life of OVC is very important in child survival [28]. As pointed out by Nsagha and Thompson [6], at the local level, the following government Ministries should be involved in OVC care: Public Health, Basic Education, Social Affairs, Agriculture, Justice, Finance, Youths Affairs, External Relations, Fisheries, Livestock and Animal Industry, Higher Education, Employment and Vocational Training, Small and Medium Size Enterprises, Forestry and Wildlife, Women’s Empowerment and the Family, Environment and Nature Protection, and Labour and Social Security as they all have something to offer in terms of child survival and youth development [6]. At the international level, it would be good establishing continous strong and sustainable working collaborations with the following international bodies: UNICEF, USAID, UNAIDS, WHO, UNESCO, ILO, Save the Children, bilateral and multilateral organizations, NGOs and so forth who have proven their worth in the fight since the HIV and AIDS pandemic emerged about three decades ago [6]. In these partnerships, focus should be placed on women since these are the most vulnerable groups including girls who are more infected than boys.

These OVC need much assistance such as the provision of school materials including acquisition of birth certificates for all children who need them, treatment of all sick children through signing of contracts with health institutions for periodic medical checks and the establishment of school canteens to take care of feeding needs of children, while at school can greatly improve the living conditions of OVC [6].

Previous authors [6] have insisted on the incorporation of HIV/AIDS lessons into the primary school curriculum which can empower OVC to prevent themselves from HIV and nutritional programmes (lunch canteens) and the enhancement of foster families to provide food for OVC which can build the capacity of the children and the families, which no doubt, is a major component of sustainability. Since the writing of wills is not a common practice in Cameroon, and taking into consideration the high rate of mortality due to AIDS, building the capacity of local communities on will writing in order to protect the property of sick parents and OVC from grapping by the extended family would greatly assure the future of OVC. The psychological impact of HIV/AIDS including social stigma is enormous on many OVC and needs to be addressed as this affects their growth, development and survival. The quantification of stigma and stress are new researchable areas in OVC care and HIV/AIDS [6].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

Professor Laporte Ron of the WHO Collaborating Center, The Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, is thanked for the extensive work in proof reading, suggestions, revisions and editing the manuscript. Mr Peter Ngwa and Eric Mofor of AMPHI Documentation, Buea, provided technical assistance in the literature search and the design of the graphics to whom the authors are grateful indeed. This work was funded by the Quarterly Research Allowance from the Ministry of Higher Education in Cameroon that was given to the lead and third authors.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

DSN conceived the study, conducted the literature search and review, drafted the manuscript, revised it and has extensively worked with many organizations on HIV/AIDS OVC. ACZKB, SMN, JCNA, HLFK, DMN and ALN participated in the literature search and substantially revised the manuscript. MTOO and AKN substantially revised the manuscript for academic content. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

This work has no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.GAC. Orphan and Vulnerable Children. Global Action for Children 2010. Available from Available from http://www.globalactionforchildren.org . [Retrieved on 10 December 2010].

- 2.Serey S, Many D, Sopheak M, et al. Addressing the special needs of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC): a case study in Kien Svay district, Kandal province, cambodia. J AIDS HIV Res. 2011;3:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett T, Whiteside A. AIDS in the 21st century: disease and globalization. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2006. pp. 1–416. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNICEF. A human rights-based approach to education for all. New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curley J, Fred S, Han KC. Assets and educational outcomes: Child Development Accounts (CDAs) for orphaned children in Uganda. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2010;32:1585–90. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nsagha DS, Njunda AL, Kamga HLF, Assob JCN, Mokube JA, Weledji EP. The epidemiology of orphans and vulnerable children due to HIV/AIDS in an integrated community care scheme in Bafaka Balue, Ndian Division, Cameroon. 2011. (In press. Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance)

- 7.Comite National de Lutte contre le SIDA. Le Cameroun face au VIH/SIDA. Une Ré#x00E9;ponse ambitieuse, multisectorielle et décentralisée (2003). Yaounde, Cameroon. 2003. pp. 1–30.

- 8.UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2008. Available at: http://www.unaids. Org . [Accessed June 12, 2009].

- 9.Nsagha DS, Thompson RB. Integrated care of orphans and vulnerable children in Ekondo Titi and Isangele Health Areas of Cameroon. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2011;10:161–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National AIDS Control Committee. The impact of HIV and AIDS in Cameroon through 2020. Central Technical Group. 2010. pp. 1–30.

- 11.Mbanya D, Sama M, Tchounwou P. Current status of HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: How effective are control strategies? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2008;5:378–383. doi: 10.3390/ijerph5050378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eboko F. Evaluation of the access to ART and the health care system in Cameroon. WHO meeting on positive synergies between health systems and global health initiatives; 2-3 October 2008; Marseille, France. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministère de la Santé Publique (Cadre conceptuel du DIS viable) 2002.

- 14.Njom Nlend AE, Mbessa Ayissi JP, Nsagha DS. Approche méthodologique pour le recensement des orphelins et enfants vulnérables en milieu urbain au Cameroun (Yaoundé 1 et Yaoundé 6). 4E Conférence Francophone, VIH/SIDA; 29- 31 Mars; Paris-France. 2007a. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Njom Nlend AE, Mbessa Ayissi JP, Nsagha DS, Talom K, Dongmo HET, Elong N, Bela M, Tjeega F. Profil sociodémographique des orphelins et enfants vulnérables en milieu urbain: le cas de la ville Yaoundé. 4E Conférence Francophone, VIH/SIDA; 29-31 Mars; Paris-France. 2007b. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbopi Kéou FX, Mpoudi-Ngollé E, Nkengasong J, et al. Trends of AIDS epidemic in Cameroon, 1986 through 1995. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:89–91. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199805010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia Calleja JM, Mvondo JL, Sam Abbenyi S, et al. Profil de l’épidémie VIH/SIDA au Cameroun. Bull Liais Doc OCEAC. 1992;99:31–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Calleja JM, Abbenyi S. Review of HIV prevalence studies in Cameroon. AIDS Inform Bull. 1993;1:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Public Health. HIV Sentinel Surveillance. Cameroon. 2000.

- 20.Institut National de la Statistique. Enquête Demographique et de Santé Cameroun. Available at: http://www.measuredhs.com/countries/ 2004. [Accessed April 15 2008].

- 21.Elat NJB. Apercu de l’épidémie du SIDA et de la riposte nationale fin 2005. Presentation datelier des formation des personnel sanitaires. 2006.

- 22.The AIDS Impact Model is part of the Spectrum System of Policy Models. For more information, see the Health Policy Initiative website, http://www.healthpolicyinitiative.com. Available at: http://www.healthpolicyinitiative.com/index.cfm?id=softwareDownload&name=Spectrum&file=SpecInstall.zip&site=H PI . [Accessed May 16, 2011].

- 23.Ministry of Public Health. National AIDS Control Committee. Annual Report, Cameroon. 2005.

- 24.Integrated Foundation Development. Supporting Orphans and Vulnerable children with PLAN and the Government [of Cameroon]. Available at: http://idfbamenda.wordpress.com/ourwork/health/ovc/ [Accessed on October 20, 2011].

- 25.UNICEF. Cameroon: HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/cameroon_statistics.html . 2009. [Accessed 23 October 2011].

- 26.Ministry of the Economy, Plan and Regional Development, UNICEF, and the National Institute of Statistics. Cameroun, Suivi de la situation des enfants et des femmes. 2006. pp. 1–355.

- 27.Aubourg DE. Expanding the first line of defense: community-based institutional care for orphans. International Conference on AIDS; 2004; Bangkok, Thailand. 2004. Abstract no. WePeD6612. [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the rights of the child, Publications and information on the work of the United Nations Children's Fund and its advocacy for children's rights, survival, development and protection. Available at: www.unicef.org/crc . 1990. [Accessed May 2, 2007].

- 29.WHO. Millennium Development Goals. Available at: http://www.who.int . [Accessed July 26, 2009].

- 30.Audemard C, Vignikin K. Orphans and vulnerable children due to HIV/AIDS in Sub-saharan Africa. Available at: http://www.ceped.org/cdrom/orphelins_sida_2006/en/biblio/index.html . [Accessed May 27, 2011].

- 31.Locoh T. Fertility Decline and Family Changes in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Afric Policy Stud. 2002;7:17–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell G, Chinake T, Mudzinge D, Maambira W, Mukutiri S. Children in Residential Care: The Zimbabwean Experience. 2004. pp. 1–54.

- 33.Nigeria OVC. Available at: www.change.org/chrifacaf/blog/view/orphans_and_vulnerable_children_OVC_in_nigeria . [Accessed July 20, 2009].

- 34. Zambia OVC. OVC Nutrition and Education Program. Available at: www.pcizambia.org/pciz-ovcnep.html . [Accessed July 21, 2009].

- 35.Mali OEV. Réseau des intervenants auprès des orphelins et autres enfants vulnérable. Available at www.reseauoev.org/fiches/factsheetOpresenting.pdf . [Accessed July 21, 2009].

- 36.Ministry of Public Health, Cameroon. Annual report. National AIDS Control Committee. 2007. pp. 1–92.

- 37.Demographic and Health Survey, 2004. National Multiple Indicators. Cluster Survey registries of vital (birth and death) statistics (1998-2005) by Patrick Mellor of the World Bank's Economic Policy and Debt Department. Available at: Available at: www.hewlett.org . [Accessed June 21, 2009].

- 38.Orphans in Cameroon. Orphan and Destitute Children Program | rudec. Available at: www.rudec.org/orphans . [Accessed July 25, 2009].

- 39.Cameroon Ministry of Public Health. Cameroon National AIDS Control Committee, 2009. Evaluation of the data on the management of orphans and vulnerable children: January 2006- December 2007; pp. 1-132. Available at: Available at: http://www.minsante.cm . [Retrieved on April 5, 2009].

- 40.UNICEF, UNAIDS and the Future Group. National Responses to Orphans and Other Children in sub-Saharan Africa - the OVC Programme Effort Index 2004, September 2004; and Demographic and Health Surveys, 2006

- 41.UNAIDS and UNICEF. Africa’s orphaned and vulnerable generations. Children Affected by AIDS. 2006. pp. 1–52.

- 42.Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys and Demographic and Health Surveys, 1998-2005.

- 43.Tsounkeu M. The Millennium Development Goals in Cameroon: How far from the target in 2005. Available at: http://www.unaids.Org. www.commonwealthfoundation.com/uploads/.../mdg_cam eroon.pdf . [Accessed May 5, 2009].

- 44.United Nations Statistics Division. Millennium Development Goals: Cameroon. Retrieved from http:// indexmundi.com/cameroon/millennium_development_goals.html ; Convention on the Rights of the Child; New York, NY; 2007. [Accessed May 9, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministère de la Santé Publique. Comité National de Lutte Contre le SIDA. Evaluation des statistiques de prise en charge des OEV: Jan 2006 - Déc 2007. Available at: http://www.kwanzaakeepers.com/africa-aids-death-count/africa-aids-death-count.htm . 2009. [Accessed: March 14, 2010]. pp. 1–32.

- 46.Africa death count. women, children & men in sub-Saharan Africa have died of AIDS. Available at: http://www.kwanzaakeepers.co m/africa-aids-death-count/africa-aids-death-count.htm . [Accessed 19 October, 2011].

- 47.UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2010. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf . [Retrieved 2011-06-08].

- 48.Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, et al., editors. Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2nd ed. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO (World Health Organization) and UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) Improved Methods and Assumptions for Estimation of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Its Impact: Recommendations of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimations, Modeling and Projections. AIDS. 2002;16:W1–W14. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200206140-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray CJL, King G, Lopez AD, Tomijima N, Krug EG. Armed Conflict as a Public Health Problem. BMJ. 2002;324:346–49. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7333.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathers CD, Shibuya K, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Global and Regional Estimates of Cancer Incidence and Mortality by Site. I. Application of Regional Cancer Survival Model to Estimate Cancer Mortality Distribution by Site. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams BG, Gouws E, Boschi-Pinto C, Bryce J, Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet. 2002;2:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crowcroft NS, Stein C, Duclos P, Birmingham M. How best to estimate the global burden of pertussis? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:413–8. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein C E, Birmingham M, Kurian M, Duclos P, Strebel P. The global burden of measles in the year 2000-a model that uses country specific indicators. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:8–14. doi: 10.1086/368114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morris SS, Black RE, Tomaskovic L. Predicting the Distribution of Under-Five Deaths by Cause in Countries without Adequate Vital Registration Systems. Int J Epidimiol. 2003;32:1041–51. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.UNICEF. Immunization - Why are children dying? Available at: www.unicef.org/immunization/index_why.html . [Retrieved May 31, 2011].

- 57.Hill K, AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Estimates of Maternal Mortality for 1995. Bull WHO. 2001;79:182–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]