Abstract

Objectives

Little is known about whether public health (PH) enforcement of Ohio's 2007 Smoke Free Workplace Law (SFWPL) is associated with department (agency) characteristics, practice, or state reimbursement to local PH agencies for enforcement. We used mixed methods to determine practice patterns, perceptions, and opinions among the PH workforce involved in enforcement to identify agency and workforce associations.

Methods

Focus groups and phone interviews (n=13) provided comments and identified issues in developing an online survey targeting PH workers through e-mail recruitment (433 addresses).

Results

A total of 171 PH workers responded to the survey. Of Ohio's 88 counties, 81 (43% rural and 57% urban) were represented. More urban than rural agencies agreed that SFWPL enforcement was worth the effort and cost (80% vs. 61%, p=0.021). The State Attorney General's collection of large outstanding fines was perceived as unreliable. An estimated 77% of agencies lose money on enforcement annually; 18% broke even, 56% attributed a financial loss to uncollected fines, and 63% occasionally or never fully recovered fines. About half of agency leaders (49%) felt that state reimbursements were inadequate to cover inspection costs. Rural agencies (59%) indicated they would be more likely than urban agencies (40%) to drop enforcement if reimbursements ended (p=0.0070). Prioritization of SFWPL vs. routine code enforcement differed between rural and urban agencies.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate the importance of increasing state health department financial support of local enforcement activities and improving collection of fines for noncompliance. Otherwise, many PH agencies, especially rural ones, will opt out, thereby increasing the state's burden to enforce SFWPL and challenging widespread public support for the law.

In November 2006, 58% of Ohio voters approved the Smoke Free Workplace Act, making Ohio one of 36 states to pass legislation regarding indoor tobacco exposure in workplaces and the 12th state to protect all citizens from secondhand tobacco smoke exposure in public places and most workplaces.1–4 Implemented on May 3, 2007, the Smoke Free Workplace Law (SFWPL) limits tobacco use in about 280,000 places of employment and public places in Ohio. Private residences, family-owned businesses without non-family employees, certain areas of nursing homes, outdoor patios, and some retail tobacco stores were exempt.4 In 2007, 23.1% of Ohioans were current smokers, which was a significantly higher percentage than for the U.S. population as a whole (19.8%).5

State and local public health (PH) agencies were charged with SFWPL enforcement. Local PH departments (agencies) choosing to enforce SFWPL could be reimbursed $125 by the Ohio Department of Health (ODH) for each completed investigation that had all required notifications filed within 50 calendar days of an initial issuance. Punitive fines to violators ranged from a warning letter to a $100, $500, $1,000, or $2,500 fine for the fifth and subsequent violations.6,7 Inspectors could double fines for intentional violations and assess daily fines for continuing violations. Outstanding obligations could be turned over to the State Attorney General's (AG's) office for collection.8

Upon implementation, several PH agencies opted out, requiring ODH to enforce the law. By July 2009, 41 agencies had opted out, leaving enforcement in 24 of Ohio's 88 counties to ODH.9 Further rule changes allowed agencies to keep 90% of the paid fines to cover enforcement costs. Additionally, administrative hearings for violators were assumed by state offices.

Nonetheless, the actual cost of enforcement, which varies by jurisdiction, is unknown but continues to drive PH agencies to opt out, thereby increasing the burden on ODH.10 Beyond costs, how an agency enforces ordinances can vary depending on the clarity of legislation and associated rules, professional training and expertise, differing views on prioritization and risk, differences in levels of authority, ineffective strategies, political pressures, population size served, and available staff and time for enforcement.11–14 Prioritization and enforcement practices may be greatly influenced by decreasing funding and increased public expectation.15 Moreover, little was known about how these factors influenced PH practice of SFWPL enforcement across Ohio's 88 counties and whether variation in practice is associated with agency characteristics. Knowledge about these variations may provide best practices for agencies to follow or areas in need of action.

Therefore, we used qualitative and quantitative direct assessment of the PH workforce to provide information on the barriers, incentives, practice patterns, fiscal pressures, and opinions on SFWPL enforcement. Furthermore, we examined whether the agency census designations, as rural or urban, and supervisory levels, as administration or direct enforcement staff, may be associated with differences in PH practice and opinions regarding SFWPL.

METHODS

Phase one involved identifying informants through focus groups and phone interviews. Focus groups were attended by either executive (administrative) or direct enforcement workers. Focus group responses were recorded in notes, with audio recordings transcribed by two investigators (David Bruckman and Aiswarya Chandran Pillai). Key informant interviews (administrators only) used only written notes. Session questions were open-ended, and some questions were based on Resnick et al.'s study15 and on suggestions within our PH practice-based research network.16 Attendees were asked whether their agency enforced SFWPL, how they would describe the results of the law, their opinions on the online enforcement registration system, and how well the online system was integrated into their practice. Attendees were asked about the public reaction if the law was repealed; their experiences in speaking with business owners about the law; workplace issues; barriers to enforcement at the business, agency, and political levels; and the apparent effectiveness and effect of the law on businesses. The session ended by asking about perceived differences in how enforcement is prioritized across administrative levels in their agency. Comments from written materials were subjectively coded into key words and issues, and then grouped into domains to develop questions for an online survey.

Phase two involved developing the online survey targeting PH professionals to collect their opinions and descriptions of workplace issues regarding enforcement. Recruitment relied upon refining publicly available e-mail listings from state agency websites to create a contact list. Invitations were e-mailed to executives and any PH staff believed to be involved in tobacco cessation education or enforcement. E-mail addresses were used in the initial recruitment wave. Invitations in state PH and professional association newsletters recruited additional respondents in a second wave. All participants giving informed consent were offered a $10 gift card in compensation.

Survey analysis plan

Voluntary survey responses included agency identification, level of administrative or direct enforcement capacity, and personal characteristics (e.g., gender and smoking history). We used five-level scales of agreement (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly agree) and scales of frequency (1 = always, 2 = usually, 3 = half the time, 4 = occasionally, and 5 = never). Each question allowed respondents to answer “not applicable” or “skip/refused.” We used SurveyMonkey® for survey administration and SAS® for analysis.17,18 We classified respondents as being from urban or rural agencies based on U.S. Census classifications of Ohio counties.19–22 In general, communities with fewer than 50,000 in population were considered rural. We categorized self-reported job level as “administration” or “non-administration,” ranking medical directors and project supervisors into the former category and all others into the latter category. We used nominal Chi-square tests of association to test job class, regions, and other factors against survey responses.23 This article reflects all data beyond preliminary results.24–26

RESULTS: PHASE ONE

In October and November 2010, 13 people (informants) were interviewed in person or by phone, providing the following insights: Ohio PH agencies used registered sanitarians, environmental health supervisors, health educators or project specialists, and contracted inspectors for direct enforcement. In Ohio, registered sanitarians are certified professionals who routinely perform licensing or permitting and inspections of food vendors, pools, schools, and nursing homes. Most sanitarians performed SFWPL enforcement. Educators covered health promotion events and enforcement but left inspections and fines to sanitarians. In general, most informants preferred client education to assessing fines. Some administrators preferred to use non-sanitarians for enforcement because they felt businesses were more likely to work closely with sanitarians that were not identified with SFWPL enforcement.

Their greatest challenge to enforcement was in adhering to the 50-day filing window, second to explaining legal details with frustrated bar and restaurant owners. ODH was seen as responsive to local issues by providing online resources that clarified legal details.27,28

Informants categorized businesses into three groups. First, businesses disinterested in maintaining a smoke-free workplace generally involved veterans' halls, lodges, and adult entertainment sites. Several direct enforcement officers stated that these business owners “considered fines as a cost of doing business.” These businesses would delay entry of inspectors to hide evidence. The second group consistently tried to adhere to regulations, but indoor smoking occasionally occurred among tourists or during crowded seasonal events. The third group was characterized as businesses with adjacent public nonsmoking and private smoking areas. These businesses usually involved group homes and assisted-living facilities.

Nearly all informants noted safety as a priority. Rare threats to personal safety spurred practice change. Informants worked in pairs when inspecting veterans' halls, lodges, and adult private clubs. Informants felt that they could rely on local law enforcement for support, but promptness varied. Most felt that workplaces and restaurants adapted within the year after enactment, with most restaurants having adapted well to the law. All informants acknowledged widespread public acceptance of the law from smokers and nonsmokers.

Informants uniformly perceived that collection of large fines by the State AG's office was unreliable, placing financial pressure on agency budgets. Administrative informants felt the PH benefits were worth the cost of enforcement, while many sanitarian informants believed food and business inspections were more important priorities. We perceived these differences as areas for further study.

After subjective coding and refinement of transcripts and notes, we categorized responses into the following domains:

Public perception of the law

Business response to the law

Workforce issues, including inspector safety

Prioritization of SFWPL vs. other code enforcement

Online enforcement administrative Web-based application

State-level support for local enforcement

Enforcement administration

Fees and local health department finances

Benefits vs. cost and effort at the agency level

RESULTS: ONLINE SURVEY

We developed the online survey from the aforementioned domains and identified 482 e-mail addresses across 128 jurisdictions. Of those e-mail addresses, 49 initially bounced and 433 remained.

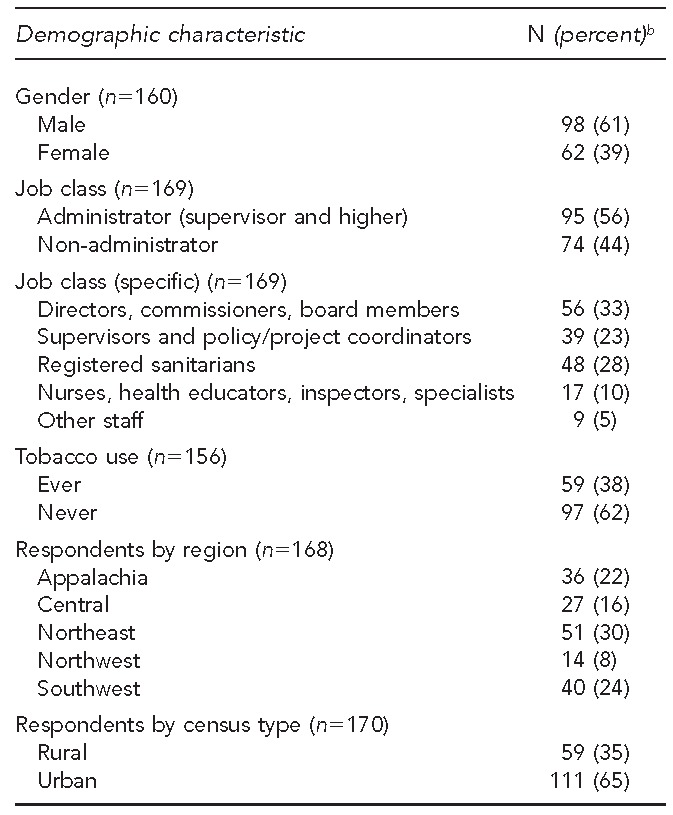

The survey was open for 30 days, from January to February 2010, during which 183 people visited the survey site (42% e-mail response) and 171 (93%) completed the survey. About two-thirds of the respondents (61%) were male and 56% self-identified as administrators. Conversely, most non-administrators were registered sanitarians, representing 28% of all consenting respondents. Current tobacco use was rare (6%, data not shown), far lower than the concurrent state prevalence (20%) (Table 1).5

Table 1.

Profile of respondents (n=171)a to a survey on SFWPL enforcement: Ohio, January–February 2010

a Not all respondents provided answers to each question.

b Not all percentages total 100 due to rounding.

SFWPL = Smoke Free Workplace Law

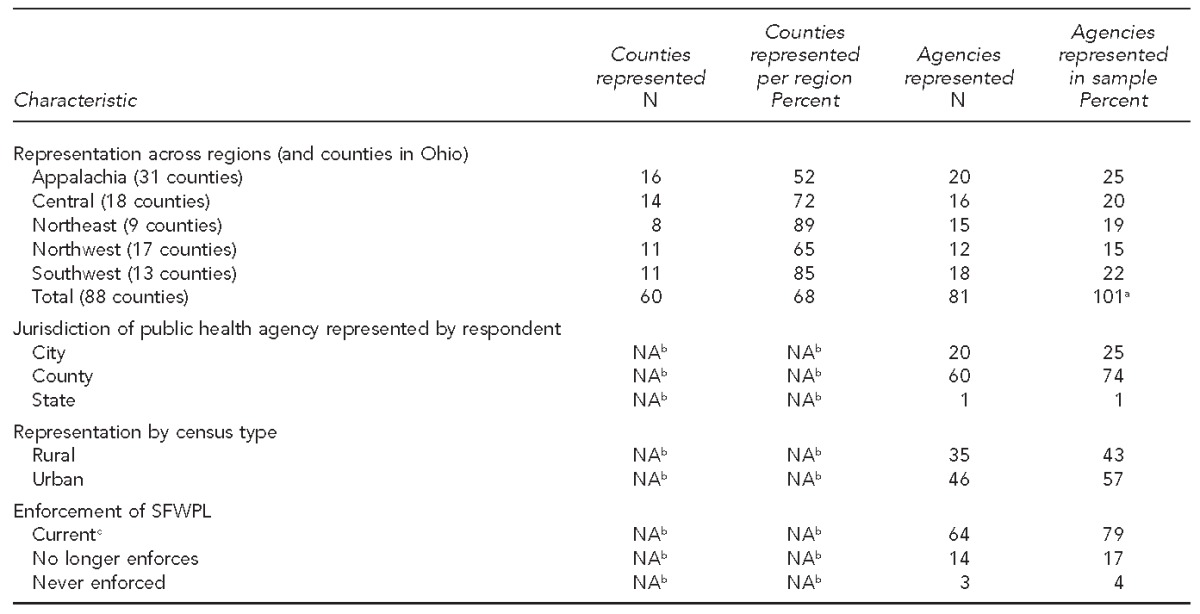

Ohio was well represented by region, county, and population. Almost half of the respondents (47%) were from southwest Ohio and Appalachia, regions comprising 50% of Ohio's 88 counties (Table 2). More than one-third of respondents were from 28 rural counties (data not shown). Table 2 presents data on the 81 jurisdictions represented. Almost two-thirds of Ohio's 128 PH agencies and 88 counties were represented, reflecting 9.48 million residents, or 82% of Ohio's population. Thirty-five agencies (43%) were considered rural jurisdictions. Thirty-six jurisdictions (45%) represented had at least two respondents.

Table 2.

Jurisdictional profile (60 counties and 81 jurisdictional agencies represented) in a survey on SFWPL enforcement: Ohio, January–February 2010

aPercentage does not total 100 due to rounding.

bData regarding jurisdiction, census type, and enforcement reflect the response of the agency's most senior administrative respondent—usually a health commissioner, medical director, or supervising registered sanitarian.

c Current enforcement refers to agencies that have enforced Ohio's SFWPL since its enactment in 2007 or were enforcing SFWPL at the time of the survey.

SFWPL = Smoke Free Workplace Law

NA = not applicable

Enforcement

When surveyed, 64 jurisdictions (79%) indicated they currently enforced SFWPL. Fourteen jurisdictions (17%) enforced in the past but ceded responsibility to ODH. Three jurisdictions (4%) never enforced the law and relied solely on ODH for enforcement (Table 2).

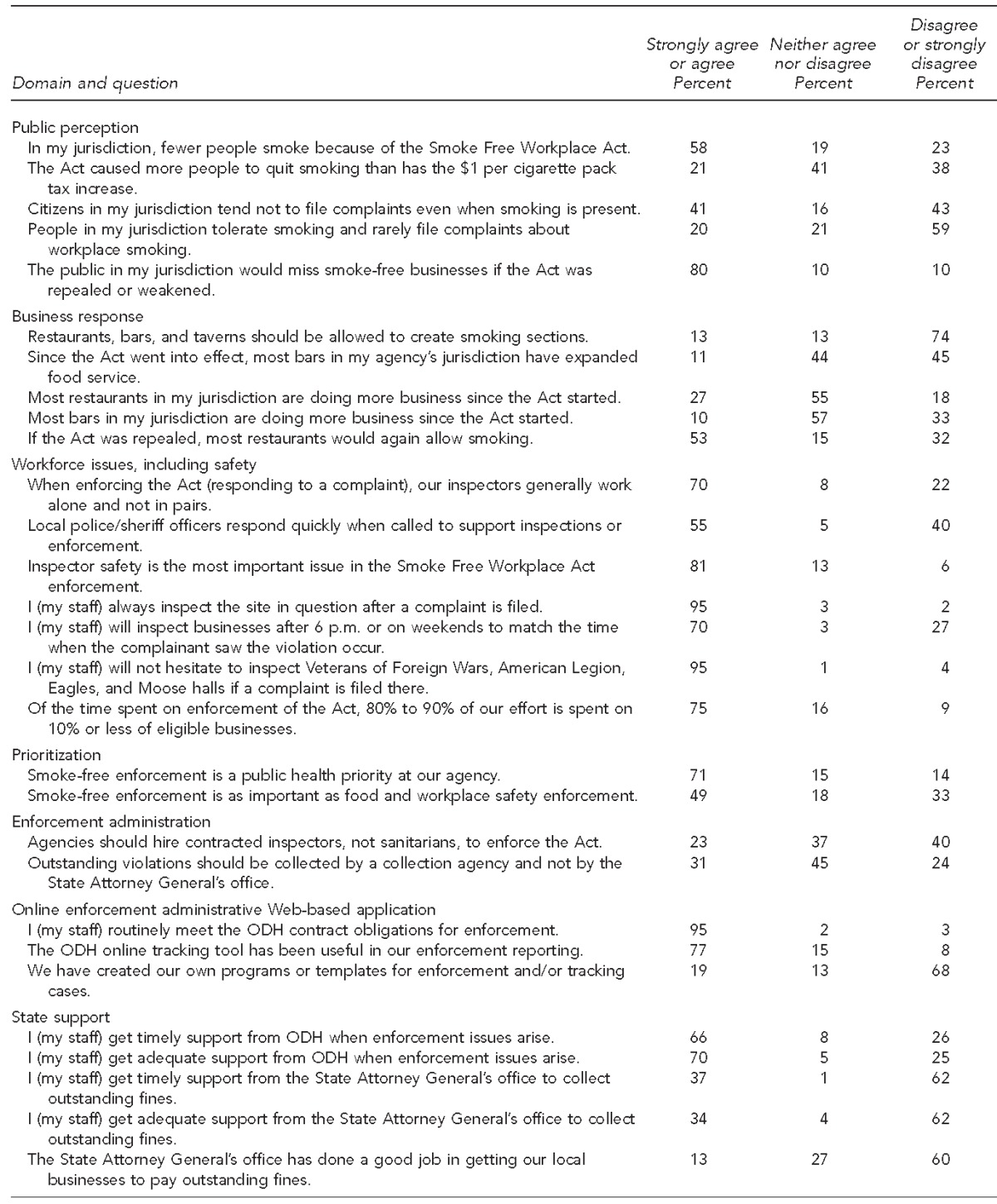

Public perception and business response

Table 3 presents the survey's 40 questions by domain and shows the percentage responding under the agreement/disagreement or frequency scales. Eighty percent of respondents strongly agreed/agreed that their local citizens would regret any weakening or repeal of the current law. A majority of respondents (58%) felt that the law helped reduce the prevalence of smoking within their jurisdiction. However, most respondents (41%) were unsure whether the smoke-free law was a greater deterrent to smoking than was a $1 tax increase on cigarettes.

Table 3.

Results of a survey on SFWPL enforcement with questions categorized by domain (n =171 respondents): Ohio, January–February 2010

SFWPL = Smoke Free Workplace Law

ODH = Ohio Department of Health

Respondents in rural counties were consistent with regard to public responses to smoking. Rural respondents were more likely than their urban counterparts to agree that residents withhold complaints even when smoking is present (56% vs. 34%, p=0.0012, degree of freedom [df]=2), and that residents tolerate smoking and rarely file complaints about workplace smoking (37% vs. 12%, p=0.0024, df=2) (data not shown).

Most respondents (74%) were clearly against weakening the law to allow businesses to create indoor smoking sections (Table 3). More than three-quarters and two-thirds of respondents felt that business among restaurants and bars, respectively, had either increased or stayed unchanged since the act was passed (data not shown).

Workforce issues, inspector safety, and prioritization

Nearly all respondents (95%) stated that they always respond to complaints, regardless of location. As heard in focus groups, three-quarters of respondents stated that most enforcement time was spent on about 10% of businesses (Table 3). More administrators than non-administrators felt it to be true (82% vs. 63%, p=0.054, df=2, data not shown). Seventy percent of respondents indicated that inspections were made routinely after agency business hours if these hours corresponded to the reported time of violation (Table 3).

Inspector safety was considered a priority by 81% of respondents. Seventy percent stated that direct enforcers generally work alone. However, only about half (55%) of respondents felt that law enforcement only arrived promptly when called for assistance. This finding signals a potential discordance between safety and PH workforce in how SFWPL enforcement is -perceived. Responses did not differ by respondent gender, job class, or census type (Table 3).

We saw subtle differences in prioritization by job class and agency census. Seventy-one percent of all respondents agreed that SFWPL enforcement was a priority at their agency, differing significantly by census (agree: 49% rural vs. 80% urban; disagree: 34% rural vs. 6% urban; p<0.0001, df=2, data not shown), but not by job class. Half of all respondents (49%) felt that enforcement was as important as food and other workplace safety code enforcement (Table 3); this response vastly differed across respondents, with 29% of rural respondents vs. 60% of urban agency respondents agreeing (p=0.001, df=2, data not shown).

Online enforcement documentation

Online enforcement documentation using the ODH online tracking tool was considered useful by 77% of respondents, and more favorably among urban (80%) than rural (68%) respondents (p=0.018, df=2, data not shown). Six jurisdictions (19%) developed their own application or software tools for enforcement to track investigations or generate form letters (Table 3).

Regarding state support, two-thirds of respondents (66%) obtained timely and adequate assistance from ODH enforcement staff (Table 3). Administrators felt more favorably toward ODH. Perceived timeliness of support also differed by job class (76% of administrators vs. 51% of non-administrators, p=0.020, df=2, data not shown) and adequacy of assistance (79% of administrators vs. 56% of non-administrators,p=0.032, df=2, data not shown).

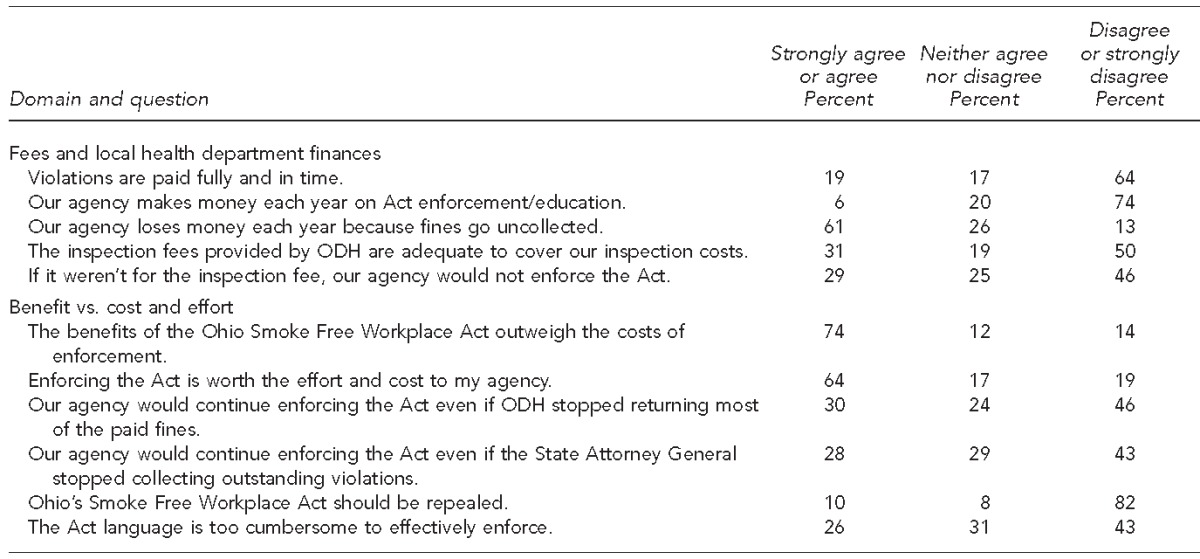

Fees and finances

In general, most agencies indicated they were losing money on enforcement. Nearly two-thirds (60%) of respondents felt that the State AG's office had not done a good job of getting local businesses to pay outstanding fines, consistent across job and agency census levels.

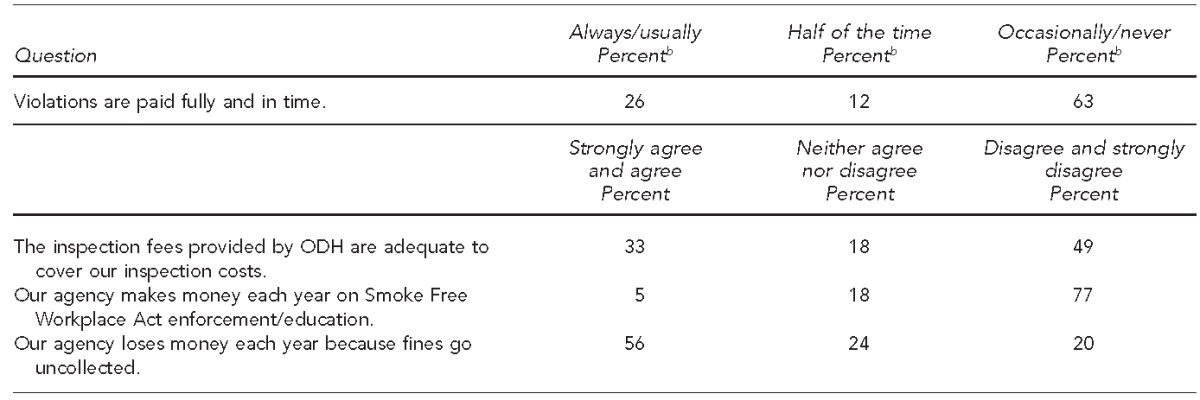

Moreover, questions on enforcement administration reflected the poor recovery of funds. In Table 4, we relied on the highest-ranking administrator per -enforcing agency (n=64) for responses. Only 26% of enforcing jurisdictions indicated they always or usually have violations paid in full, with 63% occasionally or never fully recovering fines. One-third (33%) of enforcing jurisdictions felt that the enforcement reimbursements provided by ODH were adequate to cover inspection costs, while nearly half (49%) of agency leaders felt they were inadequate.

Table 4.

Survey results regarding enforcement administrationa of the Ohio SFWPL

a Fees and fine collection as percentage of jurisdictions enforcing the SFWPL, using the highest-ranking respondent per jurisdiction. Adequate data were provided by 45 of 64 enforcing jurisdictions.

bPercentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

SFWPL = Smoke Free Workplace Law

ODH = Ohio Department of Health

Only 5% of enforcing jurisdictions made money in enforcement and education, with 18% potentially breaking even, and 77% losing money each year (Table 4). Uncollected fines were attributed to 56% of all jurisdictions losing money each year. Of those enforcing jurisdictions losing money, 40% were rural and 60% were urban; two-thirds of them directly attributed the loss to uncollected fines (data not shown). Nearly one-third (31%) of consenting respondents felt that outstanding violations should be collected by an external collections agency rather than through the State AG's office (Table 3).

Regarding benefit vs. cost and effort, 74% of respondents consistently felt that benefits of the law outweighed costs, with another 64% agreeing that enforcement was worth the cost and effort (Table 3). Administrators and urban county respondents (80% for both) were more likely than non-administrators and rural county respondents (66% and 61%, respectively) to agree that the benefits outweighed the cost (p=0.0165 for administrators/non-administrators, p=0.021 for urban/rural, each df=2, data not shown). More urban (74%) than rural (42%) respondents agreed that enforcement was worth the effort and cost to the agency (p=0.0012, df=2, data not shown). Overall, one in four respondents (26%) felt that the law was too cumbersome to enforce (Table 3).

Only 30% of respondents agreed that their agency would continue enforcement if state enforcement reimbursements stopped, while almost half (46%) of respondents indicated they would discontinue enforcement (Table 3). Rural county respondents (59%) were more likely than urban respondents (40%) to discontinue enforcement if state reimbursements ended (p=0.0070, df=2, data not shown) or if AG collection activities ended (p=0.0054, df=2, data not shown).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind on PH workforce issues related to statewide legislation to prevent indoor workplace exposure to tobacco smoke that inquired whether agencies are losing money due to enforcement and education, and to what extent uncollected fines are attributing to the loss. This study also provides qualitative evidence that most of the 64 enforcing PH agencies in the study, both rural and urban, lose money as a result of enforcement of Ohio's SFWPL, primarily due to uncollected fines. One health department reported $248,000 in outstanding fines.29 Statewide, more than $1.8 million remains uncollected.30

These findings reveal that ending state enforcement reimbursement may hamper progress in improving the long-term health of residents and may remove important systems-based prevention of tobacco smoke exposure. This finding is especially true among rural counties, where greater public tolerance for smoking was reported, consistent with tobacco use in Ohio Appalachia (31.5%) exceeding non-Appalachian Ohio counties (26.1%) between 1999 and 2003, and national levels (23.2% during 2000–2002).5,31–33 In addition, workers in rural, smaller agencies appear to favor routine inspection activities over SFWPL enforcement.

Our data reveal an impression among enforcement personnel that local restaurants and bars did generally as well or better since the law went into effect. This finding is supported by other research showing favorable changes in restaurants years after a smoking ban.34 Recent studies using sales tax receipts data from 2003 through 2010 showed that the SFWPL did not have an overall negative economic effect on Ohio restaurants and bars.30,35,36

In May 2012, the Ohio Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the smoke-free law, as well as enforcement by PH entities.37,38 This decision cleared the way for the state to pursue a backlog of uncollected fines.30 To expedite collection, the State AG's office could turn collection over to a private entity.7 Such an option seems prudent, as businesses may be more inclined to pay a collections agency than the state.

Based on our study findings, we suggest increasing state reimbursement for local enforcement. We suggest appending additional charges and interest to outstanding fines managed by the State AG's office, and linking renewal of state liquor licenses contingent on payment of all fines levied under Ohio's SFWPL. At this time, liquor permit renewals are contingent on delay or failure of filing payment of sales or withholding taxes, penalties, and interest due.39

Limitations and strengths

This study had several limitations. For one, as a convenience survey, the results are not fully generalizable to all PH workers in Ohio. Second, the low response rate may have biased inferences. Third, the compressed timeline of the Robert Wood Johnson Quick Strike posed logistical challenges. We had only six weeks between the notice of the award to the funding expiration to set up phase one groups and key informant interviews. Fourth, while we carefully transcribed and coded informant comments, we did not employ software or content methods to extract domains. E-mail lists from PH websites were also incomplete, incorrect, out of date, or missing. Nearly half (66 of 128) of jurisdictions used generic e-mail addresses, thereby limiting direct recruitment of ideal respondents and lowering the response rate. Fifth, statewide lists of registered sanitarians were not publicly available.

The study did benefit from several strengths, however, including its mixed-methods design, use of direct e-mail for recruitment, and the wide response of agencies, both rural and urban, that extended across 82% of Ohio's population. We also benefited from an insightful practice-based research team whose members varied widely in applied and academic interests.

CONCLUSIONS

This study attempted to determine and recognize differences in perceptions of Ohio's SFWPL among the PH workforce and potential impacts on performance. Despite widespread approval of the law among PH officials, differences existed in these perceptions across jurisdiction type (i.e., rural/urban-suburban) and administration levels. These differences manifest in prioritization of indoor SFWPL enforcement compared with food, workplace, and other safety code enforcement, and in the perceived benefits to the cost and effort of enforcement. Overall, three of every four PH agencies that enforce this law lose money, primarily due to unrecovered funds from violators amounting to more than $1.8 million.

Therefore, state fiscal support is critical to continue stable, statewide enforcement by local PH agencies. Loss of state financial support and an ineffective fine collection process will likely cause many PH agencies to opt out of direct enforcement. If they do, it will increase the state's burden to enforce such a law and will challenge widespread public support for the current law. We anticipate a recent Ohio Supreme Court decision in favor of PH activities to enforce this law to improve the recovery of outstanding collections and reduce these pressures on local agencies.37,38

More research will be needed to track opt-out frequencies, recovery of outstanding fines, and changes in code prioritization among enforcing PH agencies, and to compare the incidence of adverse health outcomes among similar occupations between states that do and do not have similar statewide legislation. Associations between per capita PH expenditures across agency jurisdictions may provide useful insights into changes observed.

Footnotes

Preliminary results of this study were presented as slide presentations at the Ohio Public Health Association Public Policy Institute in Columbus, Ohio, in March 2011; at the Public Health Systems and Services Research Keeneland Conference in Lexington, Kentucky, in April 2011; and at the Ohio Combined Public Health Conference in Columbus, Ohio, in May 2011; and as a poster presentation at the 2011 Annual Conference of the American Public Health Association in Washington, D.C., in October 2011.

The Ohio Research Association for Public Health Improvement is supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Quick Strike Research Fund Grant, coordinated by the University of Arkansas Medical School College of Public Health: RWJF ID# 66151 Practice-Based Research Network in Public Health. The Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through CDC cooperative agreement #1-U48-DP-001930.

All research protocols were approved by the CWRU Institutional Review Board, protocol approvals #20100923 (dated October 12, 2010) and #20110102 (dated January 28, 2011).

The findings, conclusions, and comments in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

References

- 1. Ohio Rev. Code, Tit. 37, Ch. 3794 (2006).

- 2.Ohio Department of Health. Smoke-free workplace program. [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/smokefree/sf1.

- 3.American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation. Berkeley (CA): American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation; 2010. [cited 2011 Dec 20]. U.S. tobacco control laws database: research applications. Also available from: URL: http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/USTobaccoControlLawsDatabase2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohio Department of Health. Ohio Smoke-Free Workplace Act. [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.ohionosmokelaw.gov.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System annual survey data: 2007. [cited 2012 Sep 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/surveydata/2007.htm.

- 6. Ohio Rev. Code, Tit. 37, Ch. 3701.06 (2004).

- 7. Ohio Rev. Code, Tit. 37, Ch. 3794.07 (2006).

- 8. Ohio Rev. Code, Tit. 1, Ch. 131.02 (2007).

- 9.Ohio Department of Health. Columbus (OH): ODH; 2009. [cited 2010 Dec 5]. The Ohio Department of Health is enforcing the Smokefree Workplace Law in the areas not listed below. Also available from: URL: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/behsmoke%20free%20enforcement/designeelist.ashx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peck B. State to act on smoking ban locally: Brown County Board of Health unable to enforce. News Democrat. [cited 2011 Dec 12]. Available from: URL: http://newsdemocrat.com/main.asp?SectionID=1&SubSectionID=1&ArticleID=123964&TM=65634.98.

- 11.Gordon LJ. The evolving nature of environmental health and protection. Presented at the School of Public Health Colloquium; 1994 Feb 17; Houston, Texas. [cited 2011 Dec 12]. Also available from: URL: http://sanitarians.org/Gordon/The_Evolving_Nature_of_EHProtection.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LD. The political face of public health. Public Health Rev. 2010;32:155–73. doi: 10.1007/BF03391596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobacco Law Project. St. Paul (MN): Minnesota Department of Health; 2002. [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Minding the store: curtailing the sale of tobacco to Minnesota teens: enforcement practices, challenges and recommendations. Also available from: URL: http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpcd/tpc/youth/documents/tlp_minding_the_store.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein R. New York: Independent Budget Office of New York City; 2003. [cited 2011 Dec 12]. Is everything going to be fine(d)? An overview of New York City fine revenue and collection. Also available from: URL: http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/Fines.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Resnick B, Zablotsky J, Nachman K, Burke T. Examining the front lines of local environmental public health practice: a Maryland case study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:42–50. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000303412.12227.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohio Research Association for Public Health Improvement. Home page. [cited 2012 Jun 23]. Available from: URL: http://www.ohioraphi.org.

- 17.SurveyMonkey, LLC. SurveyMonkey®. Palo Alto (CA): SurveyMonkey, LLC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.2 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (US). Washington: Bureau of the Census; 2000. [cited 2011 Dec 13]. Qualifying urban areas for census 2000: notice. Fed Reg 2002;67:21962. Also available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/geo/www/ua/frmay102.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balistreri K Ohio's rural population. Bowling Green (OH): Bowling Green State University, Center for Family and Development Research; 2004. [cited 2011 Dec 13]. Also available from: URL: http://www.bgsu.edu/downloads/cas/file36245.pdf.

- 21.Ohio Department of Development, Policy Research and Strategic Planning Office. Columbus (OH): Ohio Department of Development; 2008. [cited 2011 Dec 13]. 2008 annual loan grant report for calendar year 2007. Also available from: URL: http://www.development.ohio.gov/cms/uploadedfiles/Research/x108.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohio Department of Development, Policy Research and Strategic Planning Office. Columbus (OH): Ohio Department of Development; 2010. [cited 2011 Dec 13]. Ohio county profiles: Appalachia. Also available from: URL: http://www.development.ohio.gov/research/documents/Appalachia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruckman D. Variation in enforcement of the Ohio Smoke Free Workplace Act by local health departments. Paper presented at the 2011 Public Health Systems & Services Research Keeneland Conference; 2011 Apr 13; Lexington, Kentucky. [cited 2012 Sep 9]. Also available from: URL: http://www.publichealthsystems.org/uploads/docs/2011_Session4A.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruckman D, Chandran Pillai A, Allan T, Campbell R, Borawski EA, Stefanak M, et al. Variation in enforcement of the Ohio Smoke Free Workplace Act by local health departments. Poster session presented at the 2011 Annual Conference of the American Public Health Association; 2011 Oct 31; Washington. [cited 2012 Sep 9]. Available from: URL: http://apha.confex.com/apha/139am/webprogram/Paper235613.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruckman D. Public health workforce perspectives on the Ohio Smoke Free Workplace Law: a public health practice based research network Quick Strike research project. Paper presented at the 2012 Ohio Public Health Combined Conference; 2012 May 16; Columbus, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohio Adm. Code, Ch. 3701–52 (2007).

- 28.Ohio Department of Health. Frequently asked questions concerning the Smoke Free Workplace Law. [cited 2012 Sep 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/behsmoke%20free%20enforcement/faq.ashx.

- 29.Provance J. Budget cut may yield weakened smoke ban. Toledo Blade. 2011. Jun 3, [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.toledoblade.com/State/2011/06/03/Budget-cut-may-yield-weakened-smoke-ban.html.

- 30.McGregor M. Smoking ban violators owe state $1.8M in fines. Springfield News-Sun. 2011. Dec 10, [cited 2011 Dec 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.springfieldnewssun.com/news/springfield-news/smoking-ban-violators-owe-state-1-8m-in-fines-1297383.html.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System annual survey data: 2010. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wewers ME, Ahijevych KL, Dresbach S, Kihm KE, Kuun PA. Tobacco use characteristics among rural Ohio Appalachians. J Community Health. 2000;25:377–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1005127917122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wewers ME, Katz M, Paskett ED, Fickle D. Risky behaviors among Ohio Appalachians. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyes WJ, Marlow ML. The public demand for smoking bans. Public Choice. 1996;88:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein EG, Hood NE. Executive summary: economic impact of Ohio's Smoke Free Workplace Act. 2011. Aug, [cited 2012 Sep 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/web%20team/features/smokefreeexecsummary.ashx.

- 36.Klein EG, Hood N. Columbus (OH): Ohio Department of Health; 2011. [cited 2012 Sep 11]. Analyses of the impact of the Ohio Smoke Free Workplace Act. Also available from: URL: http://www.odh.ohio.gov/∼/media/ODH/ASSETS/Files/web%20team/features/reportsonsmokefreeworkplaceact.ashx. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wymsylo v. Bartec, Inc. Slip Opinion No. 2012-Ohio-2187 (2012).

- 38.Supreme Court of Ohio, Office of Public Information. Columbus (OH): Supreme Court of Ohio; 2012. May 23, [cited 2012 Sep 11]. Supreme Court upholds Ohio's Smoke Free Workplace Law. Also available from: URL: http://www.supremecourt.ohio.gov/PIO/summaries/2012/0523/110019.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohio Department of Commerce, Division of Liquor Control. Liquor permit information and resource directory. [cited 2012 Jun 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.com.ohio.gov/liqr/docs/liqr_ResourceDirectory.pdf.