Abstract

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is a widely used model cyanobacterium for studying photosynthesis, phototaxis, the production of biofuels and many other aspects. Here we present a re-sequencing study of the genome and seven plasmids of one of the most widely used Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substrains, the glucose tolerant and motile Moscow or ‘PCC-M’ strain, revealing considerable evidence for recent microevolution. Seven single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) specifically shared between ‘PCC-M’ and the ‘PCC-N and PCC-P’ substrains indicate that ‘PCC-M’ belongs to the ‘PCC’ group of motile strains. The identified indels and SNPs in ‘PCC-M’ are likely to affect glucose tolerance, motility, phage resistance, certain stress responses as well as functions in the primary metabolism, potentially relevant for the synthesis of alkanes. Three SNPs in intergenic regions could affect the promoter activities of two protein-coding genes and one cis-antisense RNA. Two deletions in ‘PCC-M’ affect parts of clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats-associated spacer-repeat regions on plasmid pSYSA, in one case by an unusual recombination between spacer sequences.

Keywords: CRISPR, genome sequence, plasmid, substrain, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803

1. Introduction

With currently >4000 publications available from PubMedCentral alone, ‘Synechocystis’ is the most widely used photoautotrophic prokaryotic model organism. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is a unicellular cyanobacterium that was isolated from a freshwater pond in Oakland, California.1 The high popularity of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 stems from the two facts that it was the first phototrophic and the third organism overall, for which a complete genome sequence was determined,2 and that it easily takes up exogenous DNA and integrates it into its chromosome by homologous recombination.3–5

Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 is known to occur in several distinct substrains, all going back to the same isolate deposited in the Pasteur Culture Collection.6 Indeed, several studies reported the differences between the genome sequence of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 published in 1996 (called here the ‘GT-Kazusa’ substrain) and the actual sequence found in different laboratories.7–10 A strain history has been proposed by Ikeuchi and Tabata8 with an early branching into the motile PCC strain and the non-motile ATCC 27184 strain. The latter lost motility due to a 1-bp insertion in the spkA gene coding for a eukaryotic-type Ser/Thr protein kinase11 and represents the origin of the glucose-tolerant (GT) strains5 to which also the ‘GT-Kazusa’ substrain belongs.

For decades, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 has served as a simple model in photosynthesis research and to solve fundamental questions in microbial and plant physiology. More recently, cyanobacteria are increasingly being recognized as a promising resource for the production of biofuels such as hydrogen,12 ethanol,13 isobutyraldehyde and isobutanol,14 ethylene15 and alkanes.16 Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is being developed further as a model in these biotechnology- and systems biology-oriented studies. These facts as well as the search for motility-associated genes prompted several re-sequencing studies of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substrains, namely of the substrains GT-S,10 PCC-P, PCC-N, GT-I9 and YF.17 However, these studies have not included the widely used GT and motile ‘Moscow’ substrain, which we here suggest to call ‘PCC-M’. Furthermore, thus far no attention has been paid to the possible sequence variations in the seven plasmids, which constitute a total sequence length of 383 486 bp almost 10% of the total coding capacity of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. This analysis provides new and reliable sequence data for the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substrain ‘PCC-M’, revealing several differences from the published sequence that can be interpreted as the traces of microevolution during cultivation in the laboratory.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Origin of strain, isolation of DNA and PCR analysis

Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substrains ‘Moscow’ here called ‘PCC-M, Kazusa (GT-Kazusa) and Vermaas’ (GT-V) were cultivated by Prof. Annegret Wilde (University of Freiburg, Germany) and maintained as frozen stocks. The ‘PCC-M’ substrain was originally obtained from the laboratory of S. Shestakov (Moscow State University) in 1993 and over the years carefully propagated for motile colonies. The ‘GT-V’ strain originates from the laboratory of W. Vermaas (Arizona State University). Genomic DNA for deep sequencing analysis was isolated from 80 ml cultures harvested on a glass microfiber filter (GF/C, 47 mm i.d. Whatman) by vacuum filtration. The frozen filter was ground in a mixer mill (Dismembrator MM301, Retsch, Germany) and the powder transferred into 1 ml SET buffer on ice (25% (w/v) sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5). One-fourth volume of 0.5 M EDTA, 2% SDS and 1.5 mg proteinase K (Sigma) were added for cell lysis at 50°C overnight. Following phenol/chloroform extraction, one volume of 2-propanol (Roth, Germany) was added for precipitating the DNA at room temperature for 30 min. The precipitate was washed once in H2O/2-propanol 1:1 and once in 2-propanol, followed by 10 min centrifugation at 10 000 g, 4°C. The pellet was washed with 70% EtOH, dried for 10 min and re-suspended in 50 µl H2O. One microlitre of RNase A (Sigma) was added and the tube incubated at 37°C and 260 rpm overnight. RNase was removed by another round of phenolic extraction and precipitation as described above. The DNA was re-suspended in 75 µl H2O, concentration was measured photometrically and DNA quality checked on a gel (0.8% agarose).

Genomic DNA for PCR was isolated from the cell pellet of 1 ml Synechocystis liquid culture. The pellet was washed once with a 1:10 dilution of TE buffer (10 mM Tris HCl pH 8; 1 mM EDTA) and re-suspended in 70 µl of the same buffer. Cells were broken by incubation at 98°C for 10 min. After centrifugation at 14 000 g and 4°C for 5 min, the supernatant was collected and kept on ice. Two microlitres of it were used for PCR. For PCR reactions, Phusion® DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, New England Biolabs) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. To verify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the different substrains, ∼500 bp fragments containing the SNP position were amplified. PCR products were excised from an agarose gel, purified (illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit, GE Healthcare) and sent for Sanger sequencing to GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Germany). For sequencing of the small plasmids, several PCR reactions were performed to get overlapping sequences and contigs were assembled using the software ContigExpress (Vector NTI Advance 11, Invitrogen). Alignments of the sequences were performed using AlignX (Vector NTI Advance 11, Invitrogen).

2.2. Sequencing methods and mapping

Sequencing of genomic DNA was carried out on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx system. Prior to sequencing, the DNA was sheared by ultrasonication (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA), resulting in fragments of 300 bp length on average. For these fragments paired-end sequencing according to the manufacturer's protocol was carried out, resulting in 42 143 495 million 101 nt long reads. These reads were analysed with two methods in order to identify SNPs, deletions and insertions. For the first approach, we used the DNA sequence data assembler algorithm MIRA (Mimicking Intelligent Read Assembly)18 to perform an assembly of the reads using the ‘GT-Kazusa’ genome as the reference. In the assembly process, MIRA generates tables of candidate SNPs, insertions and deletions. We verified these results independently by mapping all sequencing reads to the assembled chromosome and plasmid sequences. This was done using segemehl,19 requiring at least 85% accuracy and reporting only the best hit. It should be noted that segemehl reports co-optimal best hits.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

Sequencing of the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ‘Moscow’ substrain ‘PCC-M’ by Illumina (Solexa) yielded an average 1100-fold coverage of the chromosome and five of the seven plasmids. The existence of the two remaining plasmids was verified individually by PCR. Following assembly of sequences, mapping to the reference strain sequences and annotation, the obtained genome and plasmid sequences were deposited in the GenBank database with the accession numbers CP003265–CP003272.

Altogether, we found 45 differences (36 SNPs and 9 indels >1 bp) between the investigated substrain ‘PCC-M’ and the published sequences of the ‘GT-Kazusa’ chromosome2 and plasmids20 used here as references (Table 1). From these differences, 41 are located in the chromosome and four in the plasmids pSYSA, pSYSM and pCA2.4. For verification, about one-third of these differences were randomly chosen and confirmed independently by PCR and Sanger sequencing of the respective regions in substrain ‘PCC-M’, but no misidentified mutations were found. These DNA regions were, in addition, amplified and compared with the sequences from substrains ‘GT-Kazusa’ and ‘GT-V’ for control and comparison, respectively. The GT ‘GT-V’ was chosen for comparison as is widely used for the dissection and analysis of photosynthetic mutants. Fully segregated PSI, PSII and Chl biosynthesis mutants were successfully generated in this genetic background21,22 and some of these mutants could not be obtained in other substrains.23

Table 1.

Location and effects of SNPs and indels found in ‘PCC-M’ compared with the nucleotide sequence of ‘GT-Kazusa’ in the database

| Event |

Effect |

Locus |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | M | Start | End | Size | Nucl change | Ref →mut | AA change | Result | Locus | Gene name | Product |

| Chromosome | |||||||||||

| 1 | S | 144 507 | 14 4507 | 1 | A → G | GTA → GTG | V → V | - silent - | slr0242 | bcp | Bacterioferritin comigratory protein homolog |

| 2 | I | 386 410 | 386 411 | 102 | 34 additional AAs | slr1084 | Hypothetical protein | ||||

| 3 | S | 489 109 | 489 109 | 1 | T → C | TTA → TCA | L → S | AA change | slr1609 | Acyl-ACP synthetase (AAS) | |

| 4 | D | 527 395 | 527 994 | 600 | a | slr1753 | Hypothetical protein | ||||

| 5 | D | 731 367 | 731 367 | 1 | A → * | AAT → ATT | N → I | Frameshift | sll1574 | spkA | Part of SpkA, cellular motility regulator |

| 6 | I | 781 625 | 781 626 | 154 | 5′ extension of reading frame | IGR_slr2030_slr2031 | rsbU | Serine phosphatase, regulator of sigma subunit | |||

| 7 | S | 831 647 | 831 647 | 1 | C → T | Possible effect on infA promoter | IGR_ssl3441_sll1815 (IGR_adk_infA) | ||||

| 8 | S | 848 078 | 848 078 | 1 | G → A | AGC → AAC | S → N | AA change | slr1898 | argB | N-acetylglutamate kinase |

| 9 | S | 943 495 | 943 495 | 1 | G → A | GTC → ATC | V → I | AA changea | slr1834 | psaA | P700 apoprotein subunit Ia |

| 10 | S | 1 012 958 | 1 012 958 | 1 | G → T | a | IGR_ssl3177_sll1633 | ||||

| 11 | S | 1 070 839 | 1 070 839 | 1 | T → A | AAT → AAA | N → K | AA change | sll1359 | Predicted cytochrome c | |

| 12 | D | 1 200 290 | 1 201 474 | 1185 | ISY203b missing | sll1780 (transposase); slr1862/3 | Hypothetical protein | ||||

| 13 | S | 1 204 616 | 1 204 616 | 1 | G → A | TGT → TAT | C → Y | AA change | slr1865 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 14 | S | 1 364 187 | 1 364 187 | 1 | T → C | TTG → CTG | L → L | - silent -a | sll0838 | pyrF | Orotidine 5′ monophosphate decarboxylase |

| 15 | D | 1 423 340 | 1 423 340 | 1 | A → * | GAC → GCA | D → A | Frameshift, protein truncated | sll1951 | hlyA | Haemolysin |

| 16 | S | 1 812 419 | 1 812 419 | 1 | C → T | GCG → GTG | A → V | AA change | slr1983 | Two-component hybrid sensor and regulator | |

| 17 | D | 2 048 403 | 2 049 585 | 1183 | ISY203e missing | slr1635 (transposase); slr1636 | hypothetical protein | ||||

| 18 | S | 2 092 571 | 2 092 571 | 1 | T → A | TTA → TAA | L → * | AA change, new stop codona | sll0422 | Asparaginase | |

| 19 | S | 2 198 893 | 2 198 893 | 1 | A → G | TTA → TTG | L → L | - silent -a | sll0142 | Probable cation efflux system protein | |

| 20 | D | 2 204 584 | 2 204 584 | 1 | G → * | GGT → GTT | G → V | Frameshift | slr0162 | pilC | Part of PilC, pilin biogenesis protein, twitching motility |

| 21 | S | 2 301 721 | 2 301 721 | 1 | A → G | AAG → GAG | K → E | AA changea | slr0168 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 22 | I | 2 350 285 | 2 350 286 | 1 | * → A | a | IGR_sml0001_slr0363 | ||||

| 23 | I | 2 360 245 | 2 360 246 | 1 | * → C | GCG → GCC | A → A | Frameshifta | slr0364/slr0366 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 24 | S | 2 400 722 | 2 400 722 | 1 | C → A | Possible effect on glcP promoter | IGR_sll0771_slr0774 (IGR_glcP_secD) | ||||

| 25 | D | 2 409 244 | 2 409 244 | 1 | G → * | GGA → GAT | G → D | Frameshifta | sll0762 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 26 | D | 2 419 399 | 2 419 399 | 1 | A → * | AAT → ATG | N → M | Frameshifta | sll0751 (ycf22); sll0752 | ycf22 | Hypothetical protein YCF22 |

| 27 | S | 2 521 013 | 2 521 013 | 1 | T → C | TTT → TCT | F → S | AA change | slr0222 | hik25 | Two-component hybrid sensor and regulator |

| 28 | I | 2 544 045 | 2 544 046 | 1 | * → G | AGG → GAG | R → E | Frameshifta | ssl0787/ssl0788 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 29 | S | 2 602 717 | 2 602 717 | 1 | C → A | CAC → CAA | H → Q | AA change a | slr0468 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 30 | S | 2 602 734 | 2 602 734 | 1 | T → A | ATT → AAT | I → N | AA change a | slr0468 | Hypothetical protein, no conserved domains | |

| 31 | S | 2 748 897 | 2 748 897 | 1 | C → T | a | IGR_slr0210_ssr0332 | ||||

| 32 | S | 3 014 665 | 3 014 665 | 1 | T → C | ACT → ACC | T → T | - silent - | slr0302 | pleD | PleD-like protein |

| 33 | S | 3 098 707 | 3 098 707 | 1 | T → C | TGT → CGT | C → R | AA change | ssr1176 (transposase) | Located in a mobile element (ISY100v3) | |

| 34 | S | 3 110 189 | 3 110 189 | 1 | G → A | IGR_sll0665_sll0666 | Located in a mobile element (ISY523) | ||||

| 35 | S | 3 142 651 | 3 142 651 | 1 | T → C | CTT → CTC | L → L | - silent -a | sll0045 | spsA | Sucrose phosphate synthase |

| 36 | I | 3 194 022 | 3 194 023 | 1 | * → A | Possible effect on slr0534_as3 promoter | IGR_slr0533_slr0534 (IGR_hik10_slt) | ||||

| 37 | D | 3 260 096 | 3 260 096 | 1 | C → * | IGR_sll0529_sll0528 | |||||

| 38 | D | 3 364 288 | 3 364 288 | 1 | A → * | ATT → TTG | I → L | Frameshift | sll1496 | Mannose-1-phosphate guanyltransferase | |

| 39 | S | 3 371 938 | 3 371 938 | 1 | T → A | ATG → AAG | M → K | AA change | slr1564 | sigF | Group 3 RNA polymerase sigma factor |

| 40 | D | 3 400 331 | 3 401 513 | 1183 | ISY203g missing | sll1474 (transposase) | ccaS | sll1473/5 = His-Kinase/ATPase | |||

| 41 | S | 3 423 372 | 3 423 372 | 1 | C → T | CCC → CTC | P → L | AA change | slr0753 | Probable transport protein (anion permease) | |

| Plasmid pCA2.4 | |||||||||||

| 42 | S | 1127 | 1127 | 1 | T → G | CGT → CGG | R → R | - silent -a | repA | Replication initiation factor | |

| Plasmid pSYSA | |||||||||||

| 43 | D | 17 343 | 19 741 | 2399 | ssl7018/19/20/21 [CRISPR 1] | ||||||

| 44 | D | 71 558 | 71 596 | 159 | new CRISPR spacer | CRISPR 2 | |||||

| Plasmid pSYSM | |||||||||||

| 45 | D | 117 269 | 118 451 | 1183 | ISY203j missing | sll5130/32 | Hypothetical protein | ||||

The events are numbered (column #), the type of mutation (M) is indicated as S, substitution, D, deletion or I, insertion, together with the respective start and end positions in the ‘GT-Kazusa’ reference sequence. For each event the respective nucleotide change is indicated on the forward strand, together with the resulting codon modification (Ref. → Mut) and amino acid change, if any. Highlighted in italics are four instances of missing ISY203 copies and in bold all SNPs affecting intergenic spacer regions (IGR).

aIndicate errors in the database.

The number of differences between ‘PCC-M’ and ‘GT-Kazusa’ are almost twice as many as reported by Tajima et al.10 for the GT (GT-S) ‘Kazusa’ strain, where a total of 22 differences from the published sequence were found.10 All but 3 of those 22 differences were also detected in the ‘PCC-M’ strain studied here. The three unique differences in the ‘GT-S’ and 26 differences between ‘PCC-M’ and ‘GT-Kazusa’ underline the existence of lineage splitting in the Synechocystis substrains. Moreover, we found seven SNPs (#5, 13, 15, 16, 27, 32 and 33 in Tables 1 and 2) and one larger indel (#6 in Tables 1 and 2) specifically shared between the ‘PCC-M’ and the ‘PCC-N and PCC-P’ substrains, indicating that ‘PCC-M’ belongs to the ‘PCC’ group of motile substrains.9 ‘PCC-M and PCC-P’ are strains that both exhibit the native positive phototaxis, whereas ‘PCC-N’ strain shows negative phototaxis.24

Table 2.

Comparison of SNPs and indels found in the chromosome of ‘PCC-M’ with sequences from other substrains

| Event |

Comparison of strains: literature + this work |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Event | GT-Kazusa9,10 | GT-S10 | GT-I9 | PCC-P9 | PCC-N9 | PCC-M |

| 1 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 2 | I | — | — | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 3 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 4 | D | √a | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 5 | D | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 6 | I | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 7 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 8 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 9 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 10 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 11 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 12 | D | — | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 13 | S | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 14 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 15 | D | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 16 | S | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 17 | D | — | — | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 18 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 19 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 20 | D | — | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 21 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 22 | I | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 23 | I | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 24 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 25 | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 26 | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 27 | S | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 28 | I | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 29 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 30 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 31 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 32 | S | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 33 | S | — | — | — | √ | √ | √ |

| 34 | S | — | √ | — | — | — | √ |

| 35 | S | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 36 | I | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 37 | D | — | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 38 | D | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 39 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

| 40 | D | — | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 41 | S | — | — | — | — | — | √ |

All events are numbered (column #) as in Table 1. The presence of the respective ‘PCC-M’ mutation in the different substrains is indicated by the check marks.

aThe deletion of 0.6 kb in the gene slr1753 compared with the reference was also verified here in ‘GT-Kazusa’.

3.2. SNPs in protein-coding genes

Of the total of 36 SNPs in ‘PCC-M’ compared with ‘GT-Kazusa’, all except 1 are located in the chromosome. The single base substitution that was found on the plasmid pCA2.4 within the repA gene (#42 in Table 1) seems to be no mutation but an error in the published sequence of ‘GT-Kazusa’, since in our PCR-control experiments, the sequence was identical in the three strains ‘GT-Kazusa’, ‘PCC-M’ and ‘GT-V’. Of the 35 chromosomal SNPs compared with ‘GT-Kazusa’, 5 are silent base substitutions, 14 substitutions lead to amino acid substitutions, in 6 cases a single basepair is deleted and in 2 cases (#23 and #28) one basepair was inserted within an ORF, causing a frameshift mutation. Furthermore, five substitutions, two single basepair insertions and one single basepair deletion were observed in intergenic regions (IGR) of ‘PCC-M’ compared with the reference (Table 1).

Seven SNPs are specifically shared between the ‘PCC-M’, ‘PCC-N and PCC-P’ substrains. These are in slr1865 (#13), encoding a hypothetical protein, in sll1951 (#15), encoding a haemolysin-like protein, in slr1983 (#16), encoding a two-component hybrid sensor and regulator protein, in slr0222 (#27), encoding the histidine kinase Hik25, a silent mutation in slr0302 (#32), encoding a PAS/PAC and GAF sensors-containing diguanylate cyclase, one missing basepair, leaving the spkA gene intact (#5) and, finally, in ssr1176 (#33), encoding a transposase (Tables 1 and 2).

The gene for a cell surface-localized haemolysin-like protein, HlyA (sll1951), reported to function as a barrier against the adsorption of toxic compounds,25,26 is lacking one nucleotide in ‘PCC-M’ compared with the reference (difference #15). In the ‘GT-Kazusa’, ‘GT-V’ as well as the ‘GT-I’ and ‘GT-S’ strains,9 the presence of the additional A leads to the fusion of two ORFs that are separate in ‘PCC-M’, ‘PCC-N’ and ‘PCC-P’ substrains.9 As a result, Sll1951 is 1741 amino acids in the former and only 1437 residues in the latter.

In our data, some other previously published mutations8,10 are confirmed. For instance, spkA (sll1574; #5), a regulator of cellular motility via phosphorylation of membrane proteins,11,27 is disrupted by a 1-bp insertion in the non-motile ‘GT-Kazusa’ and ‘GT-V’ strains, whereas it is intact in the motile ‘PCC-M’ strain (Table 1). Similarly, the pilC gene (slr0162/3) required for pili assembly has been reported to carry a frameshift mutation in the ‘GT-Kazusa’ and ‘GT-S’ sequences.8,10,28 We found an intact pilC gene in ‘PCC-M’ (#20), as well as in the ‘GT-V’ substrain.

Another SNP (G–A) exists in psaA (slr1834; #9), encoding the photosynthetic P700 apoprotein subunit Ia; however, in accordance with Tajima et al.10, we believe this is an annotation error in the database as we found an A in the respective position in all three strains dealt with in this work (Table 1). Similarly, ycf22 (sll0751; #26) is here suggested to be fused to the downstream reading frame sll0752. Indeed, in blastp comparisons, both proteins together match against a single, widely distributed, larger protein of 452 amino acids. This protein possesses a Ttg2C domain (COG1463), which is found in an ABC-type transport system involved in resistance to organic solvents. The acronym ycf stands for hypothetical chloroplast reading frames, meaning proteins conserved in chloroplasts and also cyanobacteria. The 1-bp shorter version, which is splitted into sll0751/sll0752, is a database error in the case of ‘GT-Kazusa’ as well.

3.2.1. SNPs unique to ‘PCC-M’

Six of the 10 SNPs unique to ‘PCC-M’ are located within coding regions and cause amino acid substitutions or alter the length of the respective reading frame.

A single basepair transversion in the gene sigF (slr1564; #39 in Table 1) is leading to a M231K substitution within the −35 element DNA-binding region29 of a group 3 sigma factor required for phototactic movement30 and salt-stress response.31 This SNP cannot lead to impaired motility as ‘PCC-M’ is motile but it might influence the DNA–protein interaction of SigF because positively charged residues such as lysine located in this part of the σ4.2 region can directly interact with DNA.29

Another transversion, in argB (slr1898; #8 in Table 1), leads to an S2N amino acid substitution in N-acetylglutamate kinase, the enzyme performing the first committed step of Arg biosynthesis. Transitions in sll1359 and slr1609 (#11 and #3 in Table 1) result in an N–K substitution at a very conserved position within a predicted cytochrome and an L608S (L548S) substitution in the long-chain acyl-CoA-synthetase Slr1609 that has been found crucial for fatty acid activation and the biosynthesis of alkanes.32 Interestingly, an unrelated SNP exists at position 488 923 within the slr1609 coding sequence in a strain ‘YF’, leading to a G546L (G486L) substitution.17 It should be noted that the slr1609 reading frame has been annotated 60 codons shorter (636 instead of 696 amino acids) during recent re-sequencing analyses,9,10 compared with the original annotation of ‘GT-Kazusa’ (numbers in brackets). The shorter Slr1609 protein of 636 amino acids is also consistent with the mapped start site of transcription at position 487 352,33 located 115 nt upstream of the revised start codon.

A transition in slr0753 (#41 in Table 1) leads to a P113L substitution in a putative chloride efflux transport protein involved in maintaining the chloride ion concentration homoeostasis as required for a functional photosystem II.34

A single basepair deletion in sll1496 (#38 in Table 1), encoding mannose-1-phosphate guanyltransferase, causes a frameshift and premature stop of the gene in ‘PCC-M’. The resulting protein is with 515 instead of 643 amino acids severely truncated and may be rendered function-less.

3.3. Point mutations in IGRs

Compared with the reference, eight SNPs are located in IGRs, three of these (#7, 24 and 36) are ‘PCC-M’ specific. One of these (#36 in Table 1) SNPs is predicted to affect one of the recently reported cis-antisense RNAs.33 The additional A between positions 3194022 and 3194023 is located in the IGR between genes slr0533 and slr0534, encoding histidine kinase 10 (Hik10) and the soluble lytic transglycosylase Slt. On the reverse strand, the additional T falls within the predicted −10 element of the slr0534_as3 promoter. Instead of the high-scoring CATAAT,33 the motif is changed to ATTAAT. Hence, a modulation of slr0534_as3 expression compared with the reference is possible. In contrast to its designation, this cis-antisense RNA overlaps the 3′ end of genes slr0533 and hik10 (due to an error in the annotation used as the reference). In microarray analyses, slr0534_as3 of strain ‘PCC-M’ was found to be moderately to highly expressed under four tested conditions. Compared with the accumulation of the hik10 mRNA, it appeared even stronger.33 A function for Hik10 has been found in the perception of salt stress or transduction of the signal.35 The slr0534_as3 transcript may play a silencing role with regard to hik10 under non-inducing conditions. Mutation of its promoter element may hence cause a physiological effect in the salt stress response.

Two other SNPs (at positions 831 647 and 2 400 722; #7 and #24 in Table 1) could have an impact on the promoter strength or the regulation of the genes infA and glcP. For glcP, the initiation site of transcription was mapped to position 2 400 66633 and for infA to position 831 635 (unpublished). Thus, these two SNPs are located 12 and 56 nt upstream of the respective initiation site of transcription. In the case of the infA promoter, the transition replaces a nucleotide within the putative −10 element, changing it from TGTGAT to TATGAT, a much more typical motif for a −10 element in Synechocystis.33 The mutation 56 nt upstream of the initiation site of transcription of glcP might be functionally relevant as well. The gene product, a glucose transporter, is directly relevant for the physiological ability to use glucose; its gene expression is affected by mutation of the gene for the AbrB-type transcription factor Sll0822.36 The region at position −56 might well be part of the recognized sequence.

3.4. Larger indels and plasmids

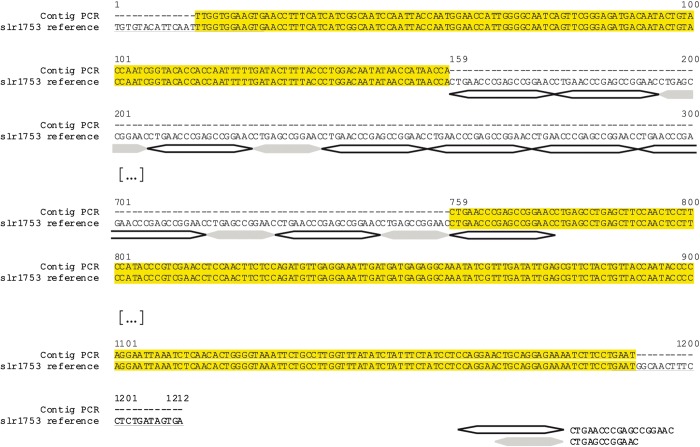

In addition to this relatively large number of SNPs, only seven larger deletions were found on the chromosome and two plasmids. Compared with the reference, a deletion of 0.6 kb exists in the gene slr1753 (#4 in Table 1), which encodes, according to our data, a giant protein comprising 1549 amino acids that probably is transported to the cell surface. However, we found this deletion in our verification also in ‘GT-Kazusa’ and ‘GT-V’. Moreover, the deleted/inserted region consists of long series of DNA repeats (Fig. 1), an evidence for a possible assembly or annotation error in the original sequence analysis.

Figure 1.

Alignment of the possible indel region in gene slr1753. The sequence obtained in the verification experiment is aligned with that of the ‘GT-Kazusa’ reference. Two types of DNA repeats are indicated by the filled and non-filled lozenges.

Given the very scarce available information concerning biological functions of the plasmids in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, it was interesting that all seven plasmids were detected during our analysis. Two, pCC5.2 and pCB2.4, were initially not found. However, as they were amplified easily by PCR, we re-inspected the unmapped sequencing reads, but still could not detect a single read matching these plasmids. This observation may relate to a lower copy number of these compared with the other plasmids, but this was not tested in the current study. Analysing the plasmid sequences, we observed a remarkable genetic stability. In addition to a single-base substitution in the plasmid pCA2.4 that might rather constitute an error in the reference sequence37 (see above) and a missing mobile element on the plasmid pSYSM, two mutations were observed, both in the plasmid pSYSA.

Two major mutations affect the clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats-CRISPR-associated proteins (CRISPR-Cas) system, located on the plasmid pSYSA. CRISPR-Cas systems provide in many archaea and bacteria an adaptive immunity against invading DNA.38–44 The plasmid pSYSA encodes the three independent systems CRISPR1, CRISPR2 and CRISPR3. A 2399-bp deletion encompassing the spacer-repeat regions 15–47 of CRISPR1 was detected in ‘PCC-M’ (#43), which also eliminated the relatively short genes ssr7018, ssl7019, ssl7020 and ssl7021, annotated within the spacer-repeat array of CRISPR1. However, the theoretical protein sequences of these gene products show no conservation at all and might not constitute real genes. Nevertheless, the deletion of spacer-repeat regions 15–47 of CRISPR1 is severe, since compared with the reference, it has eliminated two-thirds, 33 of its 49 spacer-repeat units. The sequence analysis suggests that the recombination events leading to the deletion of spacer-repeat regions 15–47 must have occurred within the direct repeats. Thus, this recombination is in agreement with previous observations that the downstream ends of the repeat clusters are conserved such that deletions and recombination events occur internally.45

A very different type of deletion was noticed for the CRISPR2 system located on the same plasmid. In this case, 159 bp were deleted (event #44 in Table 1). These 159 deleted bases correspond to positions 71 499–71 657 in the reference. The deletion encompasses two repeats including the spacer 41 in between. It is very surprising that the recombination did not occur within the repeat sections but in the adjacent spacers 40 and 42, thus generating a new ‘hybrid’ spacer 40 at positions 69 082–69 111 in the pSYSA plasmid of ‘PCC-M’ (Fig. 2). As a result, spacers 40, 41 and 42 of the original sequence are missing and became replaced by this hybrid sequence. The vast majority of described deletions in the CRISPR system occur between the direct repeats.45 Non-homologous recombination between two different spacers is rare, the deletion observed here in CRISPR2 of the plasmid pSYSA is generating additional sequence diversity in the CRISPR system. Due to the two deletions in the plasmid pSYSA, we determined its total length as 100 749 bp, compared with 103 307 bp for the reference.

Figure 2.

Non-homologous recombination in the plasmid pSYSA affecting spacers 40, 41 and 42 of CRISPR2. As a result of the 159-bp deletion in ‘PCC-M’ compared with ‘GT-Kazusa’, a novel hybrid spacer 40 was generated. The direct repeats are presented as squares and the nucleotide positions in the ‘GT-Kazusa’ are given according to the GenBank file NC_005230.

3.5. Mobile elements

As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 (differences #12, 17, 40 and 45), the ‘PCC-M’ substrain lacks four insertion elements of the ISY203 type present in ‘GT-Kazusa’.7 These elements are ISY203b, e and g on the chromosome and ISY203j on the plasmid pSYSM. These four indels have the exact same size of 1183 bp, only one is 1185 bp.

In the ‘GT-S’ substrain re-sequenced by Tajima et al.10 one of these four elements, ISY203e, is already present, placing this strain (in accordance with Ikeuchi and Tabata)8 before ‘GT-Kazusa’ in the strain history. The absence of ISY203b, e and g in ‘PCC-M’ is further shared with the strains ‘GT-I’, ‘PCC-N’ and ‘PCC-P’,9 whereas no statement is possible with regard to the possible presence of ISY203j on the plasmid pSYSM in the latter.

With respect to the described mobile elements, ‘PCC-M’ appears as one of the least-derived substrains.

4. Discussion

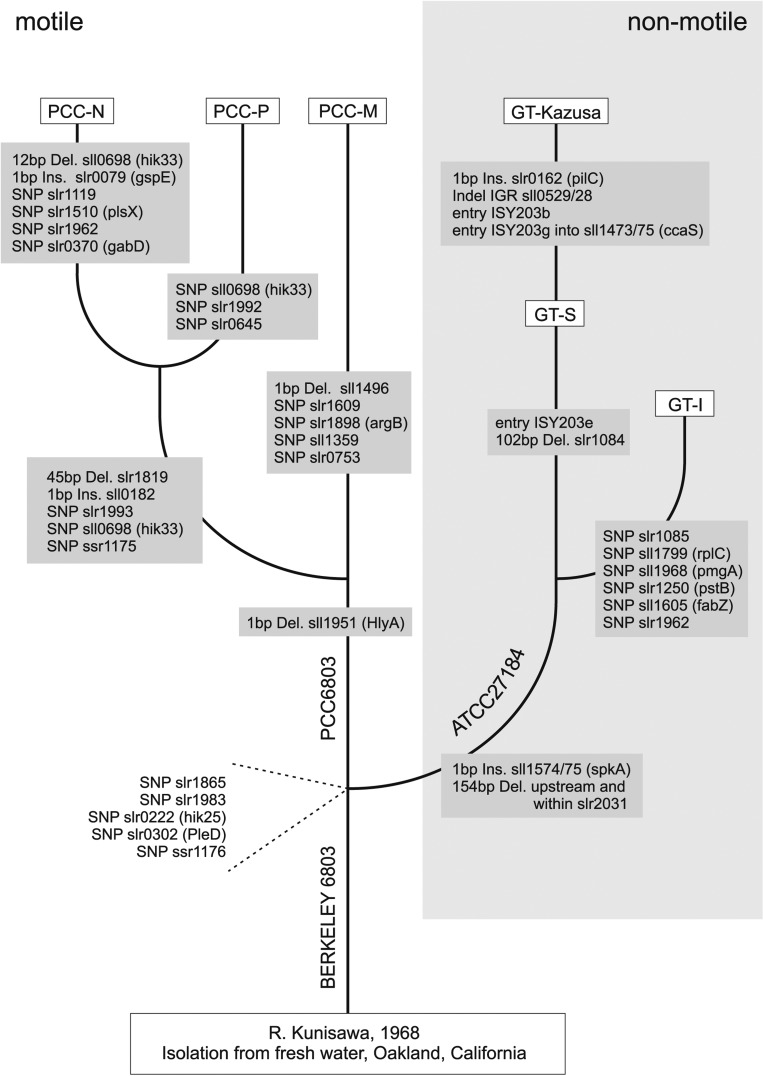

4.1. Strain history

‘PCC-M’ shows sequence differences in several genes compared with the reference sequence of ‘GT-Kazusa’ and also to the recently sequenced ‘GT-S’ strain. Kanesaki et al.9 concluded that 15 differences between the resequenced strains and the published GT-Kazusa sequence were annotation errors in the latter due to sequencing artefacts, a list to which we add two more putative errors in the database, differences #4 and #42 in Table 1. According to the proposed strain history in Ikeuchi and Tabata,8 the early division of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 into two branches occurred due to an insertion in spkA. Thus, our data suggest that the motile ‘PCC-M’ strain belongs to the motile PCC 6803 branch, whereas the non-motile ‘GT-Kazusa’, ‘GT-S’ and ‘GT-V’ strains are more closely related to each other and belong to the ATCC 27 184 branch. However, the 1-bp insertion in the pilC leading to ‘GT-Kazusa’ as described in the proposed strain history8 is not present in either ‘GT-S’ or ‘GT-V’, characterizing ‘GT-Kazusa’ as a more derived substrain.

That ‘PCC-M’ belongs to the motile PCC 6803 branch is further reinforced by our finding of six SNPs specifically shared between the ‘PCC-M’ and the ‘PCC-N and PCC-P’ substrains (Tables 1 and 2).9 These six SNPs are in slr1865, in sll1951, encoding a haemolysin-like protein, in ssr1176, encoding a transposase and, interestingly, in genes encoding sensor and/or regulatory proteins (slr1983, slr0222 and slr0302) (Tables 1 and 2) and must already have been present in the progenitor strain to ‘PCC-M’, ‘PCC-N’ and ‘PCC-P’. Additional support comes from the analysis of two larger indels (#2 and #6 in Table 1). The preceding paper, Kanesaki et al.,9 described difficulties in finding indels between direct repeat sequences such as slr1084 and slr2031 by short read type re-sequencing data. Therefore, these two regions were analysed by PCR and Sanger sequencing in addition to the re-sequencing analysis. Indeed, the finding of indels between direct repeat sequences in genes slr1084 and slr2031 turned out as not been straightforward in our analysis as well. Compared with the reference, we found in both cases the additional sequences of 102 and 154 bp to be present in ‘PCC-M’. This result is relevant for lineage relationships among substrains. The additional 102 bp in gene slr1084 are shared between ‘PCC-M’ and the other substrains ‘PCC-P’, ‘PCC-N’ and ‘GT-I’. Therefore, this must be a deletion in the lineage leading to GT-Kazusa and GT-S. In contrast, the additional 154 bp within and upstream of gene slr2031 are shared between ‘PCC-M’, ‘PCC-P’ and ‘PCC-N’ and are absent from all studied GT substrains. These 154 bp comprise the conserved start codon of slr2031 and extend the gene by 29 codons compared with ‘GT-Kazusa’. Hence, the lack of these 154 bp in GT strains indicate a functionally adverse deletion there. In fact, the 154-bp deletion in GT substrains was noticed before,46 as well as the activity of slr2031 in the original Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 substrains.47 From these considerations, the tree shown in Fig. 3 can be derived. In this tree, ‘GT-Kazusa’ is displayed as the strain with the longest evolutionary distance from the original isolate, whereas the ‘PCC-M’ substrain belongs to the ‘PCC’ group of substrains and is probably close to the original characteristics. All strains belonging to the ‘PCC’ group of substrains exhibit twitching motility as was shown also for the original PCC strain deposited in the Pasteur Culture Collection6 with variations in the motility behaviour.48,49 Since ‘PCC-M’ shows motility and is tolerant to glucose, it appears physiologically as a sort of intermediate between the two major branches: the motile and GT branches, consistent with its characterization as being close to the original characteristics.

Figure 3.

Visualization of phylogenetic relationships between various strains of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The occurrence of the identified SNPs and other known events are indicated along the branches. The eight events separating the ‘GT’ and ‘PCC’ strains from each other are given at the branch point where these two lineages split or on the respective branches where they occurred. Putative insertions and deletions are labelled ‘Ins’. and ‘Del’., respectively.

4.2. Re-sequencing studies of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803

The analysis of genome sequences of cyanobacteria has had a large impact on photosynthesis, ecology and biotechnology research.50 The present re-sequencing project delivers the new and complete sequence of the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 ‘PCC-M’, a substrain used in many laboratories and in several aspects close to the original isolate. Altogether, there are now chromosomal sequences for seven substrains of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 available: ‘PCC-M’ (this study); ‘PCC-P’ (positive phototaxis) and ‘PCC-N’ (negative phototaxis), both based on single colonies isolated from the PCC strain and designated according to their direction of phototactic movement;24 ‘GT-I’, the standard strain in Dr Ikeuchi's group;8 ‘YF’17 and ‘GT-S’,10 a current derivative of the original stock of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 from which the chromosomal reference sequence for ‘GT-Kazusa’ was determined in 19962 and for the large plasmids in 2003,20 whereas the three small plasmids had been sequenced already before.37,51,52

4.3. Mutations potentially linked to phenotype

It is likely that most of the identified differences between the sequenced substrains result from distinct differences in the cultivation conditions in the different laboratories that have selected for fixing one or the other mutation. That also implies that the majority of identified mutations are not silent but linked to a certain effect. Indeed, most mutations in coding regions are not silent as might be expected but lead to frameshifts, amino acid substitutions or the truncation of reading frames. Similarly, SNPs in non-coding regions are probably biologically meaningful, too. This idea received support here by linking three ‘PCC-M’-specific SNPs in IGRs to the promoter regions controlling the expression of two protein-coding and one antisense RNA.

For all these reasons, it appears likely that several of the mutations specific to ‘PCC-M’ or shared with ‘PCC-P’ and ‘PCC-N’ may be related to the known phenotypes of these strains. For example, the truncation of sll1951 (haemolysin) and possible truncation of slr1753 (surface protein) may contribute to a stress-induced clumping phenotype. Several other mutations might cause alterations in glucose tolerance or phototactic behaviour of these substrains. Differences at other loci may affect the phage resistance, stress response or functions in the primary metabolism, potentially relevant for the synthesis of alkanes or the N and C metabolism. The absence of ISY203g in the sll1473–5 regions in PCC substrains leads to an intact photoreceptor that regulates the expression of an alternative phycobilisome linker gene.53 Regarding phenotypic differences among motile PCC substrains, it might be noteworthy that ‘PCC-M’, despite its general ability to be motile, is not phototactic towards blue light (see direct comparison of strains in Fig. 1 of Fiedler et al.48). Here, the SNP #39 in the sigF gene, known to be involved in the control of phototactic movement30 might be considered, as the resulting M231K substitution could influence the DNA–protein interaction of this group 3 sigma factor in a very subtle way. For sure, the subtle differences in genome sequences have to be considered when choosing a particular substrain for certain experiments and when comparing phenotypes of mutant lines from different laboratories with the wild-type strain. Information on the re-sequenced genome and plasmid sequences including precisely annotated SNPs can be found in the eight sequence files available from GenBank under the accession numbers CP003265–CP003272.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-ENERGY-2010-1) under grant agreement no. [256808] and from the German Research Foundation (DFG) project FOR1680 ‘Unravelling the Prokaryotic Immune System’ (grant HE 2544/8-1) to WRH and from grant AL 892/1-4 to SAB.

Footnotes

Edited by Naotake Ogasawara

References

- 1.Stanier R.Y., Kunisawa R., Mandel M., Cohen-Bazire G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales) Bacteriol. Rev. 1971;35:171–205. doi: 10.1128/br.35.2.171-205.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., et al. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions (supplement) DNA Res. 1996;3:185–209. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.185. doi:10.1093/dnares/3.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haselkorn R. Genetic systems in cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:418–30. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04022-g. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(91)04022-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter R.D. DNA transformation. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:703–12. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67081-9. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(88)67081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams J.G.K. Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis 6803. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:766–78. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(88)67088-1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J.B., Herdmann M., Stanier R.Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto S., Ikeuchi M., Ohmori M. Experimental analysis of recently transposed insertion sequences in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 1999;6:265–73. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.265. doi:10.1093/dnares/6.5.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeuchi M., Tabata S. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803—a useful tool in the study of the genetics of cyanobacteria. Photosynth. Res. 2001;70:73–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1013887908680. doi:10.1023/A:1013887908680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanesaki Y., Shiwa Y., Tajima N., et al. Identification of substrain-specific mutations by massively parallel whole-genome resequencing of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2012;19:67–79. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr042. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsr042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tajima N., Sato S., Maruyama F., et al. Genomic structure of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strain GT-S. DNA Res. 2011;18:393–9. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr026. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamei A., Yuasa T., Orikawa K., Geng X.X., Ikeuchi M. A eukaryotic-type protein kinase, SpkA, is required for normal motility of the unicellular Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:1505–10. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1505-1510.2001. doi:10.1128/JB.183.5.1505-1510.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinlay J.B., Harwood C.S. Photobiological production of hydrogen gas as a biofuel. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010;21:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.02.012. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng M.D., Coleman J.R. Ethanol synthesis by genetic engineering in cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:523–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.523-528.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atsumi S., Higashide W., Liao J.C. Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:1177–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1586. doi:10.1038/nbt.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahama K., Matsuoka M., Nagahama K., Ogawa T. Construction and analysis of a recombinant cyanobacterium expressing a chromosomally inserted gene for an ethylene-forming enzyme at the psbAI locus. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003;95:302–5. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(03)80034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schirmer A., Rude M.A., Li X., Popova E., del Cardayre S.B. Microbial biosynthesis of alkanes. Science. 2010;329:559–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1187936. doi:10.1126/science.1187936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki R., Takeda T., Omata T., Ihara K., Fujita Y. MarR-type transcriptional regulator ChlR activates expression of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis genes in response to low-oxygen conditions in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:13500–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346205. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.346205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chevreux B., Wetter T., Suhai S. Proceedings of the German Conference on Bioinformatics (GCB); Hannover, Germany: 1999. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann S., Otto C., Kurtz S., et al. Fast mapping of short sequences with mismatches, insertions and deletions using index structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000502. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko T., Nakamura Y., Sasamoto S., et al. Structural analysis of four large plasmids harboring in a unicellular cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2003;10:221–8. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.5.221. doi:10.1093/dnares/10.5.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Q., Brune D., Nieman R., Vermaas W. Chlorophyll alpha synthesis upon interruption and deletion of por coding for the light-dependent NADPH: protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase in a photosystem-I-less/chlL− strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;253:161–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530161.x. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen G., Vermaas W.F. Chlorophyll in a Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 mutant without photosystem I and photosystem II core complexes. Evidence for peripheral antenna chlorophylls in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13904–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobotka R., Duhring U., Komenda J., et al. Importance of the cyanobacterial Gun4 protein for chlorophyll metabolism and assembly of photosynthetic complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:25794–802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803787200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M803787200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshihara S., Geng X., Okamoto S., et al. Mutational analysis of genes involved in pilus structure, motility and transformation competency in the unicellular motile cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:63–73. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce007. doi:10.1093/pcp/pce007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakiyama T., Araie H., Suzuki I., Shiraiwa Y. Functions of a hemolysin-like protein in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Arch. Microbiol. 2011;193:565–71. doi: 10.1007/s00203-011-0700-2. doi:10.1007/s00203-011-0700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakiyama T., Ueno H., Homma H., Numata O., Kuwabara T. Purification and characterization of a hemolysin-like protein, Sll1951, a nontoxic member of the RTX protein family from the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:3535–42. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3535-3542.2006. doi:10.1128/JB.188.10.3535-3542.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panichkin V.B., Arakawa-Kobayashi S., Kanaseki T., et al. Serine/threonine protein kinase SpkA in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is a regulator of expression of three putative pilA operons, formation of thick pili, and cell motility. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7696–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.00838-06. doi:10.1128/JB.00838-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhaya D., Vaulot D., Amin P., Takahashi A.W., Grossman A.R. Isolation of regulated genes of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 by differential display. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5692–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5692-5699.2000. doi:10.1128/JB.182.20.5692-5699.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane W.J., Darst S.A. The structural basis for promoter-35 element recognition by the group IV sigma factors. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040269. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhaya D., Watanabe N., Ogawa T., Grossman A.R. The role of an alternative sigma factor in motility and pilus formation in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. US A. 1999;96:3188–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3188. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.6.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huckauf J., Nomura C., Forchhammer K., Hagemann M. Stress responses of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 mutants impaired in genes encoding putative alternative sigma factors. Microbiology. 2000;146:2877–89. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-11-2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao Q., Wang W., Zhao H., Lu X. Effects of fatty acid activation on photosynthetic production of fatty acid-based biofuels in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2012;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-17. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitschke J., Georg J., Scholz I., et al. An experimentally anchored map of transcriptional start sites in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2124–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015154108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015154108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi M., Katoh H., Ikeuchi M. Mutations in a putative chloride efflux transporter gene suppress the chloride requirement of photosystem II in the cytochrome c550-deficient mutant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:799–804. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj052. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoumskaya M.A., Paithoonrangsarid K., Kanesaki Y., et al. Identical Hik-Rre systems are involved in perception and transduction of salt signals and hyperosmotic signals but regulate the expression of individual genes to different extents in Synechocystis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21531–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412174200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishii A., Hihara Y. An AbrB-like transcriptional regulator, Sll0822, is essential for the activation of nitrogen-regulated genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:660–70. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123505. doi:10.1104/pp.108.123505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X., McFadden B.A. A small plasmid, pCA2.4, from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 encodes a rep protein and replicates by a rolling circle mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3981–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3981-3991.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Attar S., Westra E.R., van der Oost J., Brouns S.J. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs): the hallmark of an ingenious antiviral defense mechanism in prokaryotes. Biol. Chem. 2011;392:277–89. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.042. doi:10.1515/bc.2011.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deveau H., Garneau J.E., Moineau S. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:475–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horvath P., Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science. 2010;327:167–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1179555. doi:10.1126/science.1179555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karginov F.V., Hannon G.J. The CRISPR system: small RNA-guided defense in bacteria and archaea. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.033. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marraffini L.A., Sontheimer E.J. Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature. 2010;463:568–71. doi: 10.1038/nature08703. doi:10.1038/nature08703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terns M.P., Terns R.M. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:321–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.005. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiedenheft B., Sternberg S.H., Doudna J.A. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482:331–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. doi:10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lillestol R.K., Shah S.A., Brugger K., et al. CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72:259–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh A., Sonoda M., Ogawa T. A possible role of 154-base pair nucleotides located upstream of ORF440 on CO2 transport of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. In: Mathis P., editor. Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 481–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamei A., Ogawa T., Ikeuchi M. Identification of a novel gene (slr2031) involved in high-light resistance in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. In: Garab G., editor. Photosynthesis: Mechanism and Effects. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 2901–5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiedler B., Börner T., Wilde A. Phototaxis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: role of different photoreceptors. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:1481–8. doi: 10.1562/2005-06-28-RA-592. doi:10.1562/2005-06-28-RA-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narikawa R., Suzuki F., Yoshihara S., et al. Novel photosensory two-component system (PixA-NixB-NixC) involved in the regulation of positive and negative phototaxis of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:2214–24. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr155. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcr155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hess W.R. Cyanobacterial genomics for ecology and biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.024. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu W., McFadden B.A. Sequence analysis of plasmid pCC5.2 from cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 that replicates by a rolling circle mechanism. Plasmid. 1997;37:95–104. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1281. doi:10.1006/plas.1997.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X., McFadden B.A. The complete DNA sequence and replication analysis of the plasmid pCB2.4 from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plasmid. 1994;31:131–7. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1014. doi:10.1006/plas.1994.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirose Y., Shimada T., Narikawa R., Katayama M., Ikeuchi M. Cyanobacteriochrome CcaS is the green light receptor that induces the expression of phycobilisome linker protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801826105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]