Abstract

Endothelial tubular morphogenesis relies on an exquisite interplay of microtubule dynamics and actin remodeling to propel directed cell migration. Recently, the dynamicity and integrity of microtubules have been implicated in the trafficking and efficient translation of the mRNA for HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor), the master regulator of tumor angiogenesis. Thus, microtubule-disrupting agents that perturb the HIF-1α axis and neovascularization cascade are attractive anticancer drug candidates. Here we show that EM011 (9-bromonoscapine), a microtubule-modulating agent, inhibits a spectrum of angiogenic events by interfering with endothelial cell invasion, migration and proliferation. Employing green-fluorescent transgenic zebrafish, we found that EM011 not only inhibited vasculogenesis but also disrupted preexisting vasculature. Mechanistically, EM011 caused proteasome-dependent, VHL-independent HIF-1α degradation and repressed expression of HIF-1α downstream targets, namely VEGF and survivin. Furthermore, EM011 inhibited membrane ruffling and impeded formation of filopodia, lamellipodia and stress fibers, which are critical for cell migration. These events were associated with a drug-mediated decrease in activation of Rho GTPases- RhoA, Cdc42 and Rac1, and correlated with a loss in the geometric precision of centrosome reorientation in the direction of movement. This is the first report to describe a previously unrecognized, antiangiogenic property of a noscapinoid, EM011, and provides evidence for novel anticancer strategies recruited by microtubule-modulating drugs.

Introduction

Tubular morphogenesis of blood vessels is a dynamic process that involves proliferation and directed migration of endothelial cells. In addition, migrating cells need to develop a unique morphological polarity involving asymmetry of their cytoskeleton, membrane trafficking and signaling (1–3). Cell motility also requires that the intracellular forces generated by dynamic reorganizations of actin and microtubule cytoskeletons within the cell be transmitted to the matrix outside the cells via tightly regulated formation and dissolution of cell–matrix contacts [focal complexes and focal adhesions (FAs)] (4). Thus, an attractive antiangiogenic strategy to disrupt endothelial cell function is to target the exquisitely regulated cooperativity of the actin/microtubule/FA axis.

It is well appreciated that disruption of microtubule dynamics is linked to inhibition of tumor angiogenesis via the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) pathway (5–7). Consequently, cytoskeleton-directed chemotherapeutics, such as members of the vinca and taxane family, have been shown to demonstrate significant antiangiogenic activity (8–10). Several other antimicrotubule drugs including combretastatin-A4 and 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME2) are currently in clinical trials due to their antiangiogenic activity (11–13). A recent report documented a previously unrecognized role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in repressing HIF-1α translation (14). The authors have elegantly demonstrated that HIF-1α mRNA binds to and traffics on dynamic microtubules to the sites of active translation. The disruption of microtubule dynamics triggers accumulation of HIF-1α mRNA into cytoplasmic P-bodies for translational repression, suggesting a direct role for microtubule integrity and dynamicity in HIF-1α translation (14). Although several tubulin-binding drugs have shown antiangiogenic activity, most studies to date have explored the roles of microtubules in antiangiogenic approaches deploying agents that depolymerize or hyperstabilize microtubules, thus addressing the consequences of extreme effects on microtubular cytoskeleton.

Seeking cues from in silico molecular modeling and rational drug design, we have launched a drug discovery program that aims to circumvent the ‘harsher’ side effects of current day antimicrotubule chemotherapy. Noscapinoids represent an emerging class of microtubule-modulating anticancer agents based upon the parent molecule, noscapine (Supplementary Figure 1A, available at Carcinogenesis Online) (15) that sets itself apart from currently available tubulin-binding drugs owing to its ‘kinder-gentler’ mechanism of action (16–21). Noscapine and its analogs have been shown to dampen microtubule dynamics just enough to alert mitotic checkpoints to stall mitosis without perturbing crucial physiological functions of microtubules such as intracellular transport (22–24). Recent studies have uncovered the antiangiogenic role of noscapine by perturbing the HIF-1α axis (25). An antiangiogenic screen of a library of microtubule-binding noscapine analogs by the Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) identified EM011, (S)-3-((R)-9-bromo-4-methoxy-6-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro[1,3]di-oxolo[4,5-g]isoquin-olin-5-yl)-6,7-dimethoxyisobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (also referred to as 9-bromonoscapine; Supplementary Figure 1B, available at Carcinogenesis Online), as a promising antiangiogenic agent. Given that EM011 is significantly more potent than noscapine in in vitro and in vivo models, we sought to evaluate and establish the antiangiogenic activity of EM011 using multifarious strategies, and to determine its underlying mechanism of antiangiogenic action. Our previously published data suggest that EM011 preserves the monomer/polymer ratio of tubulin within cells while merely dampening dynamic instability behavior of microtubules in treated cells (23). Thus, in this study, we employed EM011 concentrations that dampened microtubule dynamics without perturbing the total polymer mass of tubulin. We examined the specific effects of dampening microtubule dynamics on the ability of endothelial cells to adhere, polarize and migrate with the objective of understanding the cellular basis of EM011’s potent antiangiogenic properties.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PC-3 cells were grown using RPMI-1640 media with 10% FBS. HIF-1α and CD31 antibodies were from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). β-actin, α- tubulin and γ- tubulin were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). VE-cadherin, paxillin, p-paxillin, Rac1, Rho A and Cdc42 were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Primary antibodies against survivin and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA). Rhodamine-phalloidin and Alexa 488- or 555-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. RCC4 cells were generously provided by Lily Yang (Winship Cancer Institute, Emory, GA). Plasmid encoding green fluorescence protein (GFP)-tagged paxillin was purchased from Addgene. GFP-EB1 plasmid and CLIP170 antibody were provided by Dr Holly Goodson (University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN).

Proliferation, invasion and migration assays

HUVEC proliferation was measured using the sulforhodamine B assay as previously described (19). For the invasion assay, chambers were assembled using 8 μm pore transwell-inserts (BD Falcon) as upper chambers and 24-well plates as lower chambers. Cell culture inserts were coated with 100 μl Matrigel (1:1 diluted with PBS). 105 HUVECs or PC-3 cells were placed in the upper chamber in presence of EM011. At the end of incubation times, cells in the upper chamber were removed with cotton swabs and cells that traversed the Matrigel to the lower surface of the insert were fixed with 10% formalin, stained with crystal violet and counted under a light microscope. For chemotactic ‘migratory response’ of endothelial or PC-3 cells to EM011, we used cell culture inserts that were coated underside with Matrigel and cells were seeded next day onto the inserts in the upper chamber for varying time points. The effect of EM011 on endothelial cell migration was observed upon their inclusion in the lower chamber using crystal violet staining.

In vitro endothelial tube formation assay

Three-dimensional collagen gels containing HUVECs with or without EM011 were prepared as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen) and tube formation was visualized directly using a light microscope. Images were captured using a phase-contrast microscope and quantitation was performed using Metamorph.

Chick chorioallantoic membrane assay

EM011-mediated inhibition of blood vessel branching was observed in the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay (26). Fertilized chick eggs were incubated horizontally at 37°C in a humidified chamber for 7 days. A small orifice was made on the air sack side of the egg and suction was applied to displace the air and drop the CAM. A window of 0.6mm was cut open on the area where the CAM detached from the shell, and was sealed with adhesive tape. The eggs were re-incubated until processing the next day. Small 3M filter paper discs with holes in the center were saturated with PBS and placed on top of the CAM. EM011 (25 µM) or 10 µl of HBSS was placed in the center of the paper discs that were implanted on the CAM, and the eggs were then sealed with adhesive tape and returned to the incubator for 24h. The discs with attached CAM were cut from the rest of the egg after in ovo fixation with 4% PFA at 4°C for 20min and were examined under the microscope for branching blood vessels in control or 25 µM EM011 treatments.

Zebrafish angiogenesis assay

A transgenic zebrafish line that expresses green reef coral fluorescent protein (GRCFP) under the control of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR2) promoter [TG(VEGFR2:GRCFP)] for blood vessel restricted expression (27) was used to study the precise angiogenic stage where the drug intervenes. The effect of EM011 on zebrafish vasculogenesis was determined by treating the embryos with 25 µM EM011 at 24h postfertilization (hpf) for a period of 24h. To discern effects on preexisting vasculature, zebrafish embryos were treated with drug for 24h at 48 hpf, when intersegmental vessels have formed and are stabilized.

In vivo mouse matrigel plug assay

Male mice were injected subcutaneously near the abdominal midline, with 200 µl Matrigel (BD Biosciences) containing PC-3 (4×105) cells and the angiogenic factor, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 0.5 µg/ml). Mice were treated with vehicle or EM011 at 300mg/kg daily by oral gavage for 7 days. The Matrigel hardened to form a plug beneath the skin, which was removed 7 days later and formalin-fixed, processed and paraffin-embedded. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin as well as CD31, the immunohistochemical marker for endothelial cells to assess and quantitate the angiogenic response.

Chemokinetic assay

HUVECs were plated onto coverslips until confluence. A 200 µl pipette tip was used to create a scratch and cells were cultured in serum-free media for another 24h in the presence or absence of EM011 at 5, 10 or 25 μM concentrations. After incubation, images were taken under phase contrast using a ×10 objective.

Immunoblotting and immunostaining

Immunoblotting (HIF-1α, α-tubulin, Rac1, RhoA, Cdc42, paxillin, p-paxillin, survivin and β-actin) and immunostaining (HIF-1α, VEGF, α-tubulin, γ-tubulin, VE-cadherin, CD31, EB1, CLIP170 and rhodamine-phalloidin) for control and drug-treated samples were performed as previously described (21).

Promoter activity assay

The effect of EM011 under hypoxia on survivin or VEGF promoter activity was determined in PC-3 cells after transfecting luciferase survivin or VEGF plasmid for 24h. pRL-SV40 plasmid that expresses a Renilla luciferase gene (Promega, Madison, WI) was used as internal control. The promoter activity of the cell lysates were tested using Promega Dual Luciferase assay kit and measured using a plate reader.

Real-time RT-PCR assay

Total RNAs were isolated using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). 2 µg RNA from each sample was amplified with the Omniscript RT kit using an oligo(dT) primer (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) to generate 25 µl cDNA. 1 µl cDNA was then quantified by real-time PCR using primer pairs for HIF-1α (forward, 5′-ctggatgctggtgatttgga-3′; reverse, 5′-tgtcaccatcatctgtgag-3′) survivin (forward, 5′-tccactgccccactgagaac-3′; reverse, 5′ tggctcccagcctcca-3′), VEGF (forward, 5′-actttctgctgtcttgggtgca-3′; reverse, 5′-ccatgaacttcaccacttcg-3′) and β-actin (forward, 5′- aaagacctgtacgccaacacagtgctgtctgg-3′; reverse, 5′- cgtcatactcctgcttgctgatccacatctgc-3′) with SYBR Green PCR Master mix using the ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The quantity of PCR product generated from amplification of survivin, VEGF or HIF-1α genes was normalized using the quantity of β-actin product for each sample to obtain relative levels of gene expression.

Centration analysis of nucleus and centrosome position

Microtubules (green), centrosomes (red) and nuclei (blue) were stained using α-tubulin, γ-tubulin and DAPI, respectively. Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs were analyzed for nuclear and centrosomal reorientation as described (28). Briefly, the cell perimeter was selected and the cell centroid was determined using ImageJ software. The nuclear and centrosomal centroids were determined in a similar fashion. A line perpendicular to the leading edge (LE) and passing through the cell centroid was designated as the ‘y’ axis. ‘x’ and ‘y’ coordinates were assigned to each centroid, and then normalized with respect to the cell center, which was assigned the point (0,0). Coordinates for the nuclear and centrosomol centroids were adjusted in relation to this central point. Normalized vectors from the cell center to the nuclear and centrosomal centroids were calculated. The projection of each vector along the ‘y’ axis was used in the centration analysis, with the direction of each vector constituting the positive or negative position of the nucleus and centrosome with respect to the cell centroid.

Measurement of Cdc42 and Rac1 activity

The GST-PBD (p21-binding domain of Pak1 fused to glutathione S-transferase) pull-down assays were used to detect cellular activated (GTP-bound) Cdc42/Rac1. Briefly, HUVECs were treated for 2h with vehicle or 10 µM EM011 followed by washing with PBS and lysis using buffer (50mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10mM MgCl2, 0.15M NaCl and 1% NP-40). 500 µg protein equivalent lysates were incubated with 10 μg of sepharose-conjugated GST-PBD beads which bind activated Cdc42/Rac1. The beads were washed extensively, and proteins bound to beads were examined by immunoblot analysis for Rac1 or Cdc42.

Measurement of RhoA activity

The GST-RBD (Rhotekin-binding domain fused to glutathione S-transferase) binds specifically to GTP-bound, and not GDP-bound, RhoA proteins. Control or 2h EM011-treated HUVEC cell lysates were incubated with glutathione sepharose beads which specifically recognize and bind to the active, GTP-bound, form of RhoA. Proteins bound to beads were examined by immunoblot analysis for RhoA.

Membrane ruffling

To examine membrane ruffle dynamics, GFP-labeled HUVECs were cultured in a 37°C chamber on a TCS-SP5 confocal microscope (Leica). The leading edge (LE) of cells was recorded at 20 s intervals using the LASAF software. Membrane ruffle dynamics were presented as three-dimensional surface plots.

Data analysis

Experiments presented in figures are representative of three or more repetitions. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison between groups were evaluated by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Value of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

EM011 inhibits a cascade of critical cellular events in endothelial cells

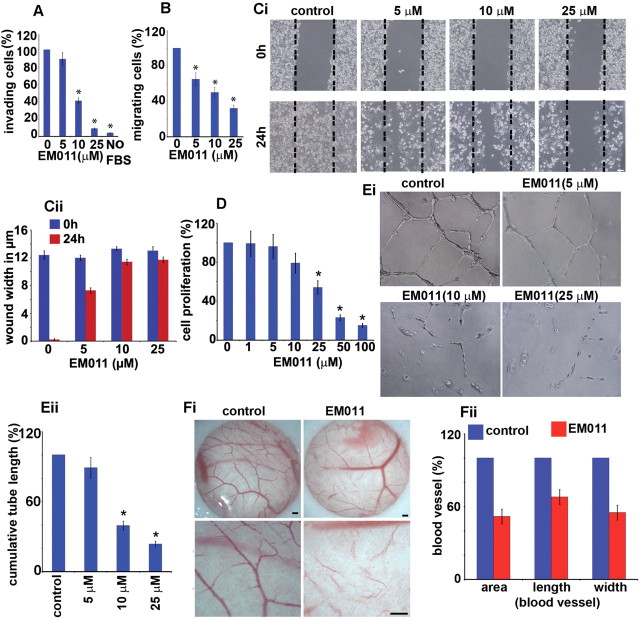

The establishment of neovasculature is a well-orchestrated process that involves invasion, migration, proliferation and tubular morphogenesis of endothelial cells (29–31). HUVECs are an ideal cellular model for studying angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in vitro and are particularly suited for pharmacological investigations of various facets of vascular biology since endothelial cells play a pivotal role in several pathophysiological processes, including cancer development. Therefore, to evaluate the antiangiogenic activity of EM011, we first examined its effect on invasion and migration of HUVECs through a simulated extracellular matrix using the modified Boyden transwell-chamber assay. We found that the invasion of HUVECs was significantly decreased by EM011 in a concentration-dependent manner. Phase-contrast images of cells that had invaded the Matrigel on the underside of the insert are shown (Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). EM011 (25 µM) decreased HUVEC invasion by ~91% compared with the control in response to 5% FBS as a chemoattractant (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). No cell invasion was observed with serum-free medium in the lower chamber (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). We next evaluated drug effects on endothelial cell migration employing chemotactic and chemokinetic models of migration. In a Boyden-chamber chemotactic assay, 25 µM EM011 inhibited the migratory response of HUVECs by ~68% compared with the control (Figure 1B, (*P < 0.05 versus control)). We also performed a complementary chemokinetic migration assay to determine whether EM011 affected directional endothelial cell motility. Since there is a likelihood that the impact of EM011 on cell proliferation or death may account for the apparent reduced migration, we performed the chemokinetic scratch assay in the presence of mitomycin, an inhibitor of proliferation. These assay conditions allowed us to decouple the effect of the drug on proliferation and migration, thus permitting evaluation of the drug’s anti-migratory potential without its non-specific effects on proliferation. To this end, confluent scrape-wounded HUVEC monolayers were incubated for 24h in the absence or presence of 5, 10 and 25 µM EM011 and 5 µg/ml mitomycin (Figure 1Ci). While control vehicle–treated cells migrated into the denuded area and recolonized ~96% of the original open area (Figure 1Ci and Cii (*P < 0.05 versus control)), EM011 remarkably inhibited this process in a concentration-dependent manner. Drug-treated HUVECs showed a decrease in the migratory potential of cells across the wound in a dose-dependent manner. EM011 at 25 µM concentration decreased the extent of wound closure by ~92% (only ~7% recolonization of the original area) compared with controls (Figure 1Cii). Together, our results offer complementary information on the chemotactic (Boyden-chamber) and chemokinetic (wound-healing) migration to emphasize the anti-migration effects of EM011.

Fig. 1.

EM011 inhibited the invasion and migration of endothelial cells in response to a chemotactic gradient. HUVECs were harvested and seeded onto 8 μm transwell-inserts (upper-chamber) coated with Matrigel in the presence of EM011 for 24h for the invasion assay. At the end of incubation times, cells in the upper chamber were removed with cotton swabs and cells that traversed the Matrigel to the lower surface of the insert were fixed with 10% formalin, stained with crystal violet, and counted under a light microscope. (A) Quantitation of the cells that invaded to the lower surface of the insert was carried out using three random fields/insert. The average number of invasive cells under control conditions (0.1% DMSO) was determined from three random fields and designated as the ‘100%’ value. For each treatment, the number of invasive cells in presence of EM011 was expressed as cells/field (mean ± SD, n = 3), quantitated as a percentage of the ‘100%’ value for the control. Migratory response was evaluated by coating the cell culture inserts underside with Matrigel and the cells were seeded next day onto the inserts in the upper chamber in the presence or absence of drug. The effect of drug on endothelial cell migration was observed by their inclusion in the lower chamber using crystal violet staining as described for the cell invasion assay. (B) Quantitation of cells that migrated to the lower surface of the insert was performed by counting cells from three random fields/insert. The average number of cells that had migrated under control conditions (0.1% DMSO) was determined from three random fields and designated as the ‘100%’ value. For each treatment, the number of cells that had migrated in presence of EM011 was expressed as cells/field (mean ± SD, n = 3), quantitated as a percentage of the ‘100%’ value for the control. Data are expressed as cells/field (mean ± SD) as a percentage of control. EM011 inhibited endothelial cell migration in a chemokinetic assay. (Ci) Photomicrographs (×10) showing confluent HUVECs that were mechanically scraped with a pipette tip, and the migration of HUVECs into the scraped area after 24h when treated with DMSO (control) or varying EM011 doses (5, 10, 25 µM). Dotted line indicates the denuded area occupied by the initial scraped area. (Cii) Quantitation of the extent of wound closure upon various treatments as measured by the width in µm of the denuded space. (D) shows the dose-dependent inhibition of HUVEC proliferation upon EM011 treatment using the sulforhodamine B assay. (Ei) EM011 inhibited in vitro endothelial tubule formation. The spontaneous formation of capillary-like structures by HUVECs on Matrigel was used to assess the angiogenic potential. HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel and 1h later, EM011 was added for 16h. Photomicrographs show that vehicle-treated controls migrated to form connected tubular networks, whereas EM011 significantly attenuated tubular morphogenesis and network formation. (Eii) Inhibition of endothelial tubule formation upon a 16h EM011 treatment was quantified from photographs by measuring the cumulative tube length contained in two random fields from each well under a phase-contrast microscope. Data are expressed as a percentage of the cumulative tube length in vehicle-treated cultures (mean ± SD). (Fi) Ex vivo antiangiogenic activity of EM011 in a CAM assay. Normal angiogenesis observed in CAM development in controls (Fi, left panel) versus decreased vascularization in the development of the CAM (Fi, right panel) when treated with 25 µM EM011. Scale bar = 5 µm. (Fii) illustrates a marked decrease in blood vessel area, length and width upon treatment with 25 μM EM011 compared with control vessels over a 24h period.

Beyond the migrating front, endothelial cells usually proliferate to generate necessary number of cells for making a new vessel. Thus, we examined the effect of EM011 on the proliferation of HUVECs using a sulforhodamine B assay. EM011 inhibited HUVEC proliferation in a concentration-time–dependent manner, with upto ~60% inhibition of proliferation upon a 48h treatment with 25 µM EM011 (Figure 1D, Supplementary Figure 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Having identified remarkable anti-invasive, antimigratory and antiproliferative properties of EM011 on endothelial cells, we next sought to examine these responses in the context of cancer cells. To this end, we evaluated the drug’s effect on the invasion and migration of metastatic PC-3 human prostate cancer cells, which represent the characteristics of cells in advanced prostate tumors and in general, constitute a great cellular model for studying cell invasion and migration. Our results demonstrated that 25 µM EM011 significantly inhibited invasion and migration of PC-3 cells in a time–dependent manner, suggesting strong antimigratory activity (Supplementary Figure 4A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). A chemokinetic scratch assay to further validate EM011’s affect on the migratory potential of PC-3 yielded remarkable inhibition of wound closure upon varying drug concentration in the presence of mitomycin (Supplementary Figure 5A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

EM011 disrupts tubular morphogenesis

Subsequent to cell proliferation, the new growth of endothelial cells spreads and aligns with each other to spontaneously form branching anastomosing tubes with multicentric junctions resulting in a three-dimensional meshwork of capillary-like tubular structures (32). Hence, our next experiment aimed to investigate EM011’s effect on tubular morphogenesis of HUVECs. Upon incubation for 16h, the cords fuse into continuous tubules with a complete lumen to form capillary-like structures in vehicle-treated cells (Figure 1Ei). However, a 16h EM011 (25 µM) treatment inhibited tubule formation with a significant reduction of ~76% in cumulative tube-length compared with vehicle-treated cultures (Figure 1Ei and Eii). This allowed us to conclude that EM011 affected endothelial cell morphogenesis into capillary tubules in vitro. Taken together, these results indicated that EM011 directly affected cultured endothelial cells by robustly inhibiting tissue remodeling processes such as invasion, migration, proliferation and capillary-tube formation, which are important attributes of a potential antiangiogenic drug candidate.

EM011 impairs ex vivo vessel outgrowth

Although in vitro cultures of isolated endothelial cells are useful to study formation of microvessels, they only partially mimic the intricacies of the elaborate angiogenic process such as the vascular wall and paracrine interactions between endothelial and perivascular cells like pericytes, smooth muscle cells or fibroblasts. In recognition of the fact that in vivo angiogenesis involves not only endothelial cells but also their surrounding cells, we examined the effect of EM011 in a CAM assay (Figure 1Fi). Our results showed that drug treatment markedly reduced vessel area by ~49%, length by ~32% and width by ~55% in chick embryos compared with control vehicle–treated embryos (Figure 1Fii). There were no observable signs of drug toxicity such as thrombosis, hemorrhage or egg lethality, confirming the non-toxic attributes of EM011.

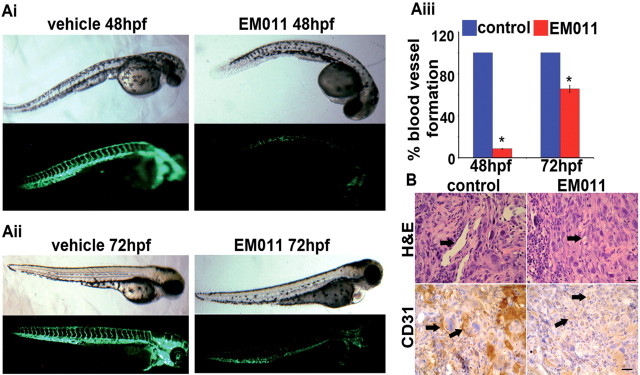

EM011 inhibits vasculogenesis and disrupts preexisting vasculature

Although the CAM assay comes closest to simulating the in vivo situation, it is best considered as an ex vivo assay. To address in vivo biological complexity, we performed a vertebrate whole-organism assay using a transgenic zebrafish model. The major mammalian pathways of angiogenic regulation are conserved in the zebrafish (33,34), making this transparent, optically visible model conducive for identification of the angiogenic stage where EM011 intervened. Essentially, this model allows analysis of the drug’s effects on vasculogenesis as well as on preexisting vasculature. Formation of stable vasculogenic vessels at 24 hpf is followed by commencement of blood flow within the embryo and formation of intersegmental vessels that sprout from preformed vasculogenic vessels and perfuse the embryo trunk (33). To first determine the drug’s effect on late-stage vasculogenesis, 24 hpf zebrafish embryos were treated with the vehicle (1% DMSO) or 25 µM EM011 for 24h. Figure 2Ai shows bright-field and fluorescent images of zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf. Normal development of vasculogenic and intersegmental vessels was evident in vehicle-treated controls, whereas drug-treated embryos showed significantly diminished vasculature (Figure 2Ai). Interestingly, the overall morphology of drug-treated embryos (bright-field) indicated minimal drug toxicity. To discern drug effects on preexisting vasculature, 48 hpf zebrafish embryos were treated with EM011 for 24h. At an endpoint time of 72 hpf, we found that EM011 remarkably collapsed preexisting vasculature, an attribute not commonly shared by many antiangiogenic agents (Figure 2Aii). Quantification of embryonic intersegmental vessel formation presents a ~91% and ~35% decrease in vessel formation upon a 24h treatment of 24 hpf and 48 hpf embryos, respectively [Figure 2Aiii (*P < 0.05 versus control)].

Fig. 2.

(Ai) EM011 inhibits angiogenic vessel growth in zebrafish embryos. Upper-panel (bright field) and lower-panel (fluorescent) depict images of 24 hpf zebrafish embryos treated for 24h with 1% DMSO (control) or 25 µM EM011. Significant inhibition of the outgrowth of intersegmental vessels indicates strong antiangiogenic effects of EM011. (Aii) EM011 disrupts preexisiting vasculature. 48 hpf embryos were treated with the drug for 24h. These embryos were imaged at 72 hpf when the vasculature is normally stabilized. The absence of intersegmental vessels and faint presence of the vasculogenic vessels show that EM011 significantly collapsed preexisting vasculature and promoted instability of these vessels. (Aiii) Quantification of intersegmental vessels upon 24h drug treatment of 24 hpf and 48 hpf embryos (*P < 0.05 versus control). Intersegmental vessels were first quantitated from 20 zebrafish embryos grown under control conditions and this value was designated at the ‘100%’ value. The number of intersegmental vessels were then determined for 20 embryos grown under each treatment condition, and each of these values was quantitated as a percentage of the ‘100%’ value for the control. (B) EM011 inhibited in vivo angiogenesis in a Matrigel plug assay. Photomicrographs show the effect of 7 day oral EM011 feeding on angiogenic response to FGF-2 supplemented PC-3 cells subcutaneously implanted as Matrigel plugs in mice. Blood vessel formation was examined by H&E and CD31 immunostaining of excised Matrigel plugs from mice that received vehicle or EM011 daily at a dose level of 300mg/kg by oral gavage. In the control images, arrows (in H&E micrographs) indicate subcutaneous Matrigel implants that demonstrate increased angiogenesis, seen as well-developed, endothelial cell–lined vascular spaces. This contrasts with the poorly developed vascular channels in the EM011 treated group. Arrows in the CD31 immunostained micrographs highlight the endothelial cells, with increased expression observed in the control group suggesting increased angiogenesis. Scale bar = 20 µm.

EM011 inhibits in vivo angiogenesis

To further investigate the drug’s effects on in vivo neovascularization, we next evaluated in vivo angiogenesis in a mouse model using a Matrigel plug assay. We found that control Matrigel plugs without FGF-2 supplements showed minimal endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis (data not shown). In stark contrast, vehicle-treated control mice with plugs containing PC-3 cells and FGF-2 demonstrated robust angiogenesis with accompanying proliferation of inflammatory and/or connective tissue cells (Figure 2B). This observation is consistent with the ability of FGF-2 to be a chemoattractant for various cells of neuroectodermal and mesodermal origin. FGF-2 supplemented PC-3 cells induced an angiogenic response that comprised of endothelial cell proliferation and their organization into blood vessels which was specifically inhibited in mice that received a daily dose of 300mg/kg EM011 for 7 days (Figure 2B). Thus, EM011 demonstrated specificity in inhibiting in vivo tumor angiogenesis with no effect on the accompanying proliferation and migration of inflammatory and connective tissue cells.

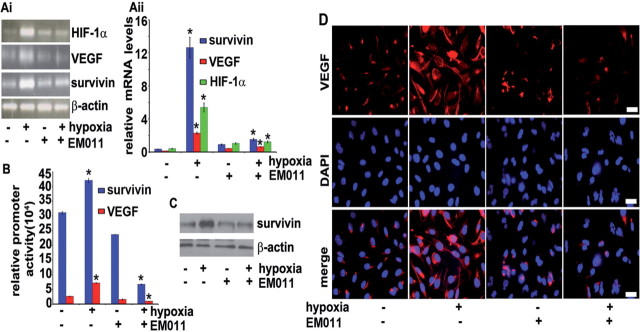

EM011 downregulates HIF-1α in a VHL-independent but proteasome-dependent manner

Overexpression of HIF-1α, a key feature of hypoxic response, strongly correlates with increased angiogenesis, abnormal vasculature, and increased proliferation of cancer cells in solid tumors (14,35). Several tubulin-binding drugs with differential effects on microtubule dynamics inhibit the HIF-1α pathway (5). Interestingly, the parent molecule, noscapine, has been recently shown to inhibit HIF-1α expression (25). Since EM011 is a brominated analog of noscapine, we reasoned that EM011 might share this biological activity. To gain mechanistic insights into EM011’s antiangiogenic behavior, we studied its effect on HIF-1α expression during normoxia and hypoxia. Immunoblotting data suggested that EM011 produced a time-dependent reduction in HIF-1α levels in PC-3 cells upon hypoxic exposure for the noted hours (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the inhibitory effects of 25 µM EM011 on HIF-1α expression levels were also evident during normoxia at 24h post-treatment (Figure 3B). These inhibitory effects of EM011 on HIF-1α expression were reproducible with variable efficiency in several different tumor cell lines including breast and glioma (data not shown). Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy in PC-3 cells further confirmed that 25 µM EM011 significantly impaired HIF-1α nuclear translocation while the microtubular networks were largely intact (Figure 3C). On the other hand, induction of HIF-1α and its nuclear accumulation was observed in PC-3 cells upon a 24h hypoxic exposure (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

EM011 decreased HIF-1α protein levels in a VHL-independent pathway. PC-3 cells were exposed to hypoxia in the presence or absence of 25 µM EM011 for (A) various time points under hypoxia, or (B) 24h under normoxia or hypoxia. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of HIF-1α in normoxic or hypoxic samples of PC-3 cells treated with 25 µM EM011 for 24h. Scale bar = 20 µm. (D) HIF-1α–dependent HRE-luc activity determined in PC-3 cells co-transfected for 6h with 6xHRE luc and pRL-SV40 Renilla luciferase plasmids followed by a 24h treatment with 0, 1, 10, 25 or 50 µM EM011 under hypoxia (*P < 0.05 versus control). (E) RCC4 cells were treated with 25 µM EM011 for 24h under normoxia and cell lysates were immunoblotted for HIF-1α protein expression. (F) Proteasome inhibition with 5 µM MG132 abrogates EM011-mediated HIF-1α degradation. PC-3 cells were co-treated with MG132 and EM011 treatment for 16h in the presence or absence of hypoxia. Cell lysates were processed for immunoblotting for HIF-1α expression.

Having identified drug-mediated inhibition of HIF-1α expression, we next examined the functional consequence of HIF-1α inhibition. To this end, PC-3 cells pretreated with increasing doses of EM011 for 24h were transiently transfected with a hypoxia-responsive element (HRE)-driven firefly luciferase reporter gene, the expression of which is dependent on the availability of HIF-1α. An SV40-driven Renilla luciferase vector was co-transfected as a transfection control. In agreement with the inhibition of HIF-1α expression, we found a dose-dependent reduction of HRE-driven luciferase activity upon EM011 treatment (Figure 3D).

The tumor suppressor Von Hippel Lindau (VHL), a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, targets HIF-1α for ubiquitin-mediated destruction under normal oxygen tension. To further explore mechanisms of EM011-mediated downregulation of HIF-1α, we tested whether this effect required a functional VHL protein and an active proteasome system. EM011 treatment of VHL-deficient RCC4 cells, which constitutively express HIF-1α, revealed that the drug-mediated destabilization of HIF-1α occurred independently of VHL function under normoxic conditions (Figure 3E). Next, we explored the role of proteasome in EM011-induced repression of HIF-1α by using MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. Co-treatment of EM011-treated cells with MG132 rescued HIF-1α protein from the degradation induced by EM011 (Figure 3F). The proteasome inhibitor mediated restoration of HIF-1α levels, thereby indicating that EM011 affected HIF-1α degradation through the proteasome system.

EM011 inhibits HIF-1α transcription and transactivation of hypoxia-inducible genes

Since regulation of HIF-1α pathway can be controlled at both transcriptional and translational levels, we next investigated if EM011 affected HIF-1α gene transcription. Levels of HIF-1α and β-actin mRNAs were measured using a quantitative RT-PCR assay and representative results of one of the three independent PCR assays are shown in Figure 4Ai. Our data clearly suggested that EM011 repressed HIF-1α mRNA levels by ~4.3-fold under hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, EM011 demonstrated a transcriptional repression of HIF-responsive genes, namely VEGF and survivin (Figure 4Ai). Quantitation of repression showed that EM011 decreased mRNA levels of VEGF and survivin during hypoxia by ~3.6 and ~8.3-fold (*P < 0.05 versus control), respectively, compared with hypoxia alone (Figure 4Aii). The effect of EM011 on HIF-1α gene transcription was further confirmed by HIF-1α overexpression in PC-3 cells. A remarkable decrease in message levels of HIF-1α, VEGF and survivin was observed upon EM011 treatment (Supplementary Figure 6A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To further examine if downregulation of HIF-1α correlated with an inhibition of HIF-1–responsive downstream genes, we used a luciferase reporter assay with a construct containing the luciferase gene under control of HREs from VEGF and survivin promoters (Figure 4B). Transiently-transfected PC-3 cells were subjected to hypoxia in presence of EM011 for 24h and luciferase luminescence was used as a readout for HIF-1α transactivation. As expected, hypoxia greatly induced luciferase activity in vehicle-treated control cells. Drug treatment, however, resulted in a pronounced decline in luciferase activity driven by HIF-inducible promoters for VEGF and survivin genes, reflecting significant reduction of HIF-1α transcriptional activity (Figure 4B). There was an inhibition of VEGF and survivin promoter activity by ~87% and ~84% (*P < 0.05 versus control), respectively, in drug-treated cells compared with hypoxic control cells (Figure 4B). This was in agreement with the drug’s ability to downregulate HIF-1α protein levels. Immunoblotting for survivin showed that EM011 could abrogate hypoxia-mediated upregulation of survivin expression (Figure 4C). Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs for VEGF staining revealed an intense staining pattern upon subjection to hypoxia, as expected. However, EM011 treatment concurrent with hypoxic stimulation attenuated VEGF expression as evident by the weak red intensity pattern (Figure 4D).

Fig. 4.

EM011 induces transcriptional repression of HIF-1α and its downstream target genes, VEGF and survivin. (Ai) EM011 decreases mRNA levels of HIF-1α, survivin and VEGF. PC-3 cells were treated with 25 µM drug in the presence or absence of hypoxia for 24h and total RNA was extracted followed by cDNA synthesis, which was quantified by real-time RT-PCR using specific primers. (Aii) Quantitation of relative mRNA levels. (B) EM011 inhibits HIF-1α transcriptional activity as seen by decreased VEGF or survivin promoter activity in a dual-luciferase promoter activity assay. (C) Immunoblot showing survivin levels under the noted treatment regimes. (D) Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs showing VEGF staining in control and EM011-treated cells under hypoxia or normoxia. Scale bar = 20 µm (*P < 0.05 versus control).

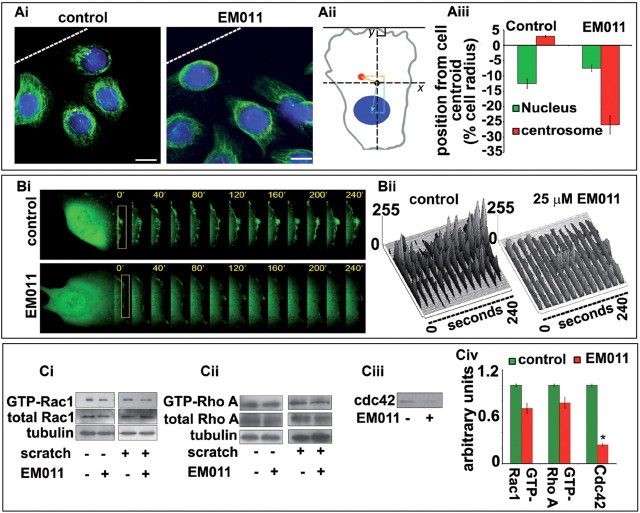

EM011 impairs cell polarization by disrupting centrosome repositioning

Our next step was to identify the cellular basis of the migration and invasion defects observed upon EM011 treatment. In migrating cells, polarization of the microtubule cytoskeleton is coupled with centrosome reorientation in the intended direction of movement (36). Partly due to centrosome repositioning, microtubules align along the axis of cell migration. Essentially, centrosome reorientation biases vesicle transport toward the LE by positioning Golgi between the nucleus and LE, which in collaboration with microtubules enhances the directional delivery and recycling of components to the LE (37). Since EM011 attenuates microtubule dynamics (20,21,24), we next asked if drug-induced modulation of dynamic instability of microtubules was associated with impaired centrosome reorientation. As shown in Figure 5Ai, in controls, cells at the wound margin exhibited a typical polarized morphology with centrosomes positioned in front of the nucleus facing the LE. In contrast, cells treated with EM011 exhibited polarization defects with randomly localized centrosomes (Figure 5Ai). Interestingly, EM011 inhibited endothelial cell migration at concentrations that did not affect gross microtubule morphology but instead induced changes in microtubule plasticity only by modulating microtubule dynamics (21). We performed a centration analysis (Figure 5Aii) by examining the position of nucleus and centrosome relative to the centroid of migrating HUVECs (28). A failure in rearward nuclear reorientation yielded a ~12% difference in centrosome positioning in EM011-treated cells when compared with controls, indicating centrosome disorientation upon drug treatment (Figure 5Aiii).

Fig. 5.

(Ai) EM011 impairs centrosome repositioning and disrupts directed migration. Confluent HUVEC monolayers were mechanically scraped to stimulate unidirectional migration, and the position of the centrosome in relation to the nucleus was visualized after 24h in the first row of cells adjacent to the open edge of the monolayer by immunofluorescent staining of α-tubulin (in green) for microtubules, γ-tubulin (in red) for centrosomes and DAPI (blue) for nuclei. White broken line indicates the LE. Scale bar = 20 µm. (Aii) An illustration of centration analysis that was performed by comparing the location of the nuclear and centrosomal centroids with the cell centroid. EM011-treated cells displayed a disruption in backward nuclear movement with respect to controls, indicating a perturbation in the migratory process. (Aiii) Graphical representation of the position from the cell centroid clearly displays a failure of rearward nuclear movement upon EM011 treatment. (Bi) HUVECs were transfected with pEGFPC1 followed by a scratch in the presence and absence of EM011. GFP fluorescence at the LE of cells was recorded at 40 s intervals using the TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica), equipped with a live-cell imaging workstation and the LASAF software. Rectangular regions were selected as indicated to analyze membrane ruffle dynamics. (Bii) Membrane ruffle dynamics was presented as three-dimensional surface plots. The y-axes of the plots denote the extent of protrusion of the region of the membrane ruffle delineated by the rectangle. (Ci–iii) HUVECs treated with vehicle or EM011 were scratched, and the level of activated (GTP-bound) Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 were assayed by immunoblot analysis of the GST-PBD/GST-RBD pull-down preparation with anti-Rac1, anti-Cdc42 and anti-RhoA antibodies. The levels of total Rac1, RhoA and tubulin were examined by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates. (Civ) Relative activity of Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 was measured by densitometric analysis of the blots. Data are the mean and standard error from three experiments (*P < 0.05 versus control).

EM011 impedes cell polarization by decreasing Rho GTPase activity

The morphological polarization of migrating endothelial cells is characterized by the appearance of membrane ruffles at the LE, asymmetric localization of signaling molecules and a reorganized cytoskeleton (2). To further confirm disruption of polarization, we first examined formation of membrane ruffles at the cellular periphery by transfecting HUVECs with pEGFPC1. The monolayer was then scratched in the presence and absence of EM011 (Figure 5Bi). GFP-fluorescence was monitored at the LE that showed thick lamellopodia-like protrusions and suggested robust membrane ruffling in controls. However, drug-treated cells showed significantly fewer ruffles (Figure 5Bi and Bii).

At the molecular level, various lines of evidence suggest that microtubules influence cell polarity and migration by affecting anchorage and protrusion through modulation of Rho family GTPases (1). Since the activity of Rho GTPases is vital for cell polarization and migration, we next investigated if EM011 modulated the activity of Rho family GTPases—Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 (Figure 5Ci–Civ). HUVECs treated with 10 µM EM011 or the vehicle were scratched and GST-PBD pull-down assays were performed. EM011 treatment caused modest but reproducible reductions in Rac1, RhoA and Cdc42 activity in HUVECs compared with the control group (Figure 5Ci–Civ).

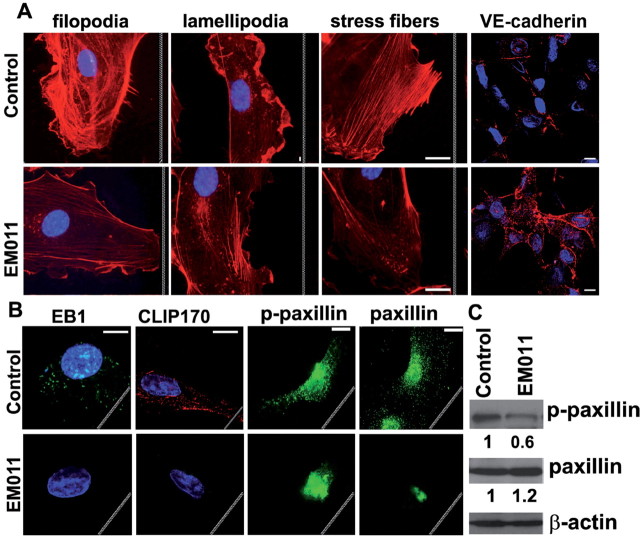

EM011 disrupts actin-microtubule cross-talk to inhibit cell migration

The dynamic cytoskeleton modulates the activity of Rho GTPases and, conversely, the activity of Rho GTPases might be responsible for the initial polarization of the cytoskeleton, suggesting existence of a positive feedback mechanism that maintains the stable polarization of a directionally migrating cell (1). We have previously shown that EM011 attenuates microtubule dynamics without affecting steady state monomer/polymer ratio of cellular tubulin (20,21,23). We envision that this dampening of microtubule dynamicity cascades to modulate Rho GTPase activity which may impact the exquisite interplay between actin and microtubule cytoskeletons necessary for efficient cross-talk between cellular polarization and local modulation of cell–matrix contacts for subsequent motility. Since EM011 treatment causes a reduction in Rho GTPase activation, we further asked how the microtubule-modulating drug EM011 affected the Rho GTPase-driven dynamic remodeling of actin cytoskeleton to yield filopodia, lamellipodia and stress fibers, and regulated adherens junctions which are essential events during the cell migration process (Figure 6A). Endothelial cells express VE-cadherin, which upon initiation of cell migration is lost (38). Filamentous filopodial projections act essentially as sensors of motile stimuli and protrusive thick lamellipodia at the LE allow swimming-like motility. Stress fibers anchored at FAs are primarily responsible for traction of cell rear toward the LE during migration (3). To gain further insights, we stained F-actin (using rhodamine-phalloidin) and VE-cadherin, and visualized HUVECs that were scratched in the presence or absence of EM011 exposure. Our data show that EM011 treatment reduced incidence of filopodial projections (Figure 6A). A reduction in lamellipodia formation was evident by an absence of thick cortical actin network characteristic of membrane ruffles (Figure 6A). Rho A activation drives formation of actin stress fibers and FAs and increases contractility (3). While actin stress fibers were clearly visible in migrating control HUVECs (Figure 6A), these fibers were significantly reduced in drug-treated cells (Figure 6A). The reduction in stress fibers was also associated with an increased accumulation and linear distribution of VE-cadherin at cell–cell contacts in drug-treated HUVECs compared with untreated controls (Figure 6A), further suggesting an inhibition of cell motility and an increase in cell–cell adhesion.

Fig. 6.

EM011 affects actin structures and adherens junctions involved in endothelial cell migration. (A) HUVECs scratched in the absence or presence of EM011 were stained for F-actin to visualize filopodia (filamentous membrane projections with long parallel actin filaments arranged in tight bundles), lamellipodia (cytoplasmic protrusions that contain a thick cortical network of actin filaments) and stress fibers (bundles of actin filaments anchored at FAs required for the traction of the rear of the cells toward the LE during migration). Endothelial cells were stained with VE-cadherin (red) and nuclei (blue). Interestingly, the VE-cadherin levels increased and appeared to get redistributed to the cellular periphery, particularly evident at sites of cell–cell contacts. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Immunofluorescence micrographs showing localization of EB1, CLIP170, paxillin and p-paxillin in HUVECs that were scratched in the presence or absence of EM011. Scale bar = 20 µm. White jagged lines indicate the LE. (C) EM011 diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin, but not total paxillin expression, in HUVECs. HUVECs were scratched in the presence or absence of 10 µM EM011 for 2h. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-phospho-paxillin and anti-paxillin. Values are from densitometric results of three separate experiments. *P < 0.05, EM011 treated versus control cells.

Cell migration requires the regulated binding of integrins to extracellular matrix adhesion molecules. In order to assess the impact of EM011 exposure on the ability of HUVECs to adhere to the substrate, we carried out a cell–matrix adhesion assay using fibronectin-coated plates. We found that EM011 treatment caused a concentration-dependent decrease in the ability of HUVECs to adhere to fibronectin-coated plates (Supplementary Figure 7, available at Carcinogenesis Online, upper panel) as well as vitronectin-coated cell culture dishes (data not shown). This loss of cell–substrate adhesion was accompanied by a marked decrease in vinculin staining in EM011-treated cells as compared with vehicle-treated controls (Supplementary Figure 7, available at Carcinogenesis Online, lower panels). Vinculin is a very important mechano-coupling component of the FA complexes at the intracellular face of the plasma membrane where it physically links transmembrane integrin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton and facilitates contractile force generation. Vinculin loss has been shown to impact assembly of FA complexes and impair cell adhesion to substratum and Rac-dependent lamellipodial extension (39,40). In fact, vinculin-deficient cells possess lamellipodia that are far less stable than in wild-type cells (40). Our data therefore strongly indicate that EM011 treatment leads to impaired migration triggered by a loss of vinculin that hinders FA assembly, lamellipodial protrusion and cell–matrix adhesion.

EM011 disrupts guided targeting of interphase microtubules and FA patterns

Guided targeting of interphase microtubules to FA sites by the actin cytoskeleton is a key step in the cascade of cell-migration events (3,4). This targeting mechanism includes growth of microtubules and their capture and transient stabilization at adhesion sites facilitated by a minimum steady-state concentration of plus-end–binding proteins such as EB1 and CLIP170 (4). In comparison with vehicle-treated controls, we found significantly reduced size of EB1 comets at the microtubule tips as well as a severely diminished staining pattern for CLIP170 in HUVECs that were scratched in the presence of EM011 (Figure 6B). We envisage that the decrease in microtubule dynamicity and the concomitant drastic reduction in EB1 and CLIP170 binding at microtubule plus-ends could impair the effectiveness of microtubule targeting to adhesion sites, and consequently, hinder the HUVECs ability to migrate over the substrate in the presence of EM011.

The FA molecule paxillin plays an indispensable role in the integration and transduction of signals from integrins and growth factor receptors to modulate cell motility, and this involves its tyrosine phosphorylation (41) and regulation of actin filament dynamics (42,43). Since the actin network plays an important role in the assembly/disassembly of paxillin at FAs, we next examined paxillin and its phosphorylation status upon EM011 treatment (Figure 6B). HUVECs transiently transfected with GFP-paxillin were scratched in the presence or absence of EM011. Immunofluorescence micrographs show that in migrating control cells, GFP-paxillin was recruited to form aggregates in the FAs at the protruding lamellipodium at the cell front (Figure 6B). EM011-treated GFP-paxillin-transfected HUVECs showed a decrease in lamellipodial protrusion, inhibition of cell migration and an aggregation of paxillin in the cell center. Thus, in contrast to control cells, which had lamellipodial protrusion with increased FA assembly in the front accompanied by a decrease in FA assembly in the center and the rear, drug-treated cells with attenuated microtubule dynamics underwent contraction from the periphery toward the cell center (Figure 6B). This was accompanied by paxillin-FA disassembly in the periphery and assembly in the center, resulting in a change in the distribution of paxillin-FAs during drug treatment (Figure 6B).

Having observed that drug-induced modulation of cytoskeletal proteins affected GFP-paxillin localization, we next determined whether paxillin levels underwent any changes or paxillin was modulated post-translationally concomitant with its subcellular redistribution. To this end, we examined the drug effects on paxillin expression and its tyrosine phosphorylation in HUVECs that were scratched in the presence or absence of EM011 (Figure 6C). Although drug treatment had little effect on the expression level of paxillin, EM011 caused a reduction in the tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin at 2h (Figure 6C).

Taken together, the data suggest that EM011 treatment not only disrupts cell polarization but also impairs the generation of filopodia, lamellopodia, stress fibres and appropriate patterns of FAs to facilitate directional cell migration.

Discussion

Once tumors escape from their stable location by breaking through the basement membrane, endothelial cells migrate toward cues provided by the tumor. Behind this migrating front, endothelial cells proliferate to make a new vessel that morphologically differentiates into capillary-like tubular networks to render support for subsequent maturation, branching, remodeling and selective regression to form a highly organized, functional microvascular network (32). Our data provide compelling evidence that EM011 affected each of these elements––invasion through the basement membrane, migration, proliferation and tube formation. While a CAM assay suggested that EM011 could significantly interfere with neovasculature establishment, the transgenic zebrafish model demonstrated drug-induced inhibition of vasculogenesis and disruption of preestablished vasculature. Mechanistically, impairment of angiogenesis was through inhibition of HIF-1α at the transcriptional as well as the level of protein stabilization in a proteasomal-dependent and VHL-independent manner.

Cell motility requires that robust actin polymerization be nucleated within the LE, causing a highly cross-linked meshwork of actin filaments to form within the lamellipodium whose growing and ‘seeking’ end faces the direction of migration (44,45). The constant unidirectional growth of actin filaments both pushes the LE forward and also creates a retrograde flow of actin toward the cell center (3,46–48). Microtubules in the lamella that grow toward the LE exhibit net polymerization at their plus-ends near the lamellipodium base and owing to the effect of actin retrograde flow, undergo bending and breakage in the cell body. Consequently, a number of microtubule minus-ends undergoing catastrophe are produced in the cell body together with several shortening plus-ends. A net concentration of localized microtubule growth near the LE activates Rac1 while microtubule disassembly in the cell body locally activates RhoA (1,3). Activation of Rac1 leads to the assembly of actin into protruding lamellipodia whereas RhoA activation results in organization of actin into contractile stress fibers and FAs in the cell body (1,3). Thus, the gradient in microtubule assembly states is translated into differential GTPase activation. Rac1 activity at the LE promotes further actin assembly, lamellipodium protrusion and actin retrograde flow in the lamellipodium and thus sets in motion a positive feedback loop that stabilizes one particular LE to maintain directional movement of the cell. Rac1 activity also promotes formation of smaller focal complexes in the LE. RhoA activity in the cell body, on the other hand, drives the organization of actin and myosin into contractile stress fibers, thus enhancing cell contractility (49,50). As RhoA activity bundles actin into stress fibers, integrin clustering occurs and this drives the assembly of larger focal complexes and promotes their maturation into FAs, a process facilitated by the targeting and capture of dynamic microtubules by FAs. Thus, dynamic instability of microtubules is pivotal not only for the generation and protrusion of lamellipodia but also for the regulated adhesion and cell contraction that occur during migration.

EM011 has been previously reported to reduce microtubule dynamicity without changing the monomer/polymer ratio of tubulin (20,21,23). Thus, there is a strong possibility that the positive feedback loop and microtubule interactions with actin are prone to becoming disturbed upon attenuation of microtubule dynamics. Interference in this positive feedback loop might contribute to the inhibition of Cdc42 activity that led to reduced filopodial extensions as well as decreased Rac1 activity that perhaps affected the formation of protruding lamellipodia. In addition, attenuated RhoA activation led to the subsequent inhibition of actin stress fiber formation. Furthermore, the drug-induced attenuation of RhoA activation may lead to a dissipation of the long-stress fibers that mediate contraction of the cell body to allow forward progression. Thus, the drug-mediated decrease in the formation of actin stress fibers led to attenuated traction forces for a rear release. Since Rho GTPases are controlled by the aggressive dynamicity of the microtubules to orchestrate cell migration, it is reasonable to speculate that EM011-induced dampening of microtubule dynamics explains the perturbations in the intricate equilibrium and tips the overall balance in favor of decreased polarization, cell–matrix adhesion and migration of endothelial cells. Consistent with this notion, EM011 increased expression of VE-cadherin at cell–cell junctions. VE-cadherin, similar to its epithelial cell counterpart, E-cadherin, is essential for control of vascular permeability and organization of tubular-like structures (38,51). It is reasonable to speculate that the presence of high levels of VE-cadherin perhaps decreases Rac1 activation and reduces formation of actin stress fibers, thus lending support to the idea that EM011 induces a cellular switch from a migratory phase to a stationary phase, and this is in part stabilized through upregulation of VE-cadherin.

Paxillin, an adaptor protein that localizes primarily in the FAs, plays a crucial role in recruiting cytoskeletal and signaling proteins to orchestrate the cross-talk between microtubules and actin filaments to regulate cell shape and motility (43). Several lines of evidence indicate that paxillin regulates Rac1 and Cdc42 activity to direct filopodial protrusions and lamellipodial extensions, important events for cell migration (4). In addition, paxillin is associated with several actin-binding proteins (such as vinculin and actopaxin) and tethered to the actin network (43). We found that EM011 treatment induced perturbation in the localization, distribution and tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin in HUVECs. This is perhaps attributable to drug-induced modulation of cytoskeletal proteins that causes diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and the relocalization of paxillin from FAs to cell center, which confirms conclusions from earlier studies (52) that tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin is an important process for paxillin-FA assembly/disassembly.

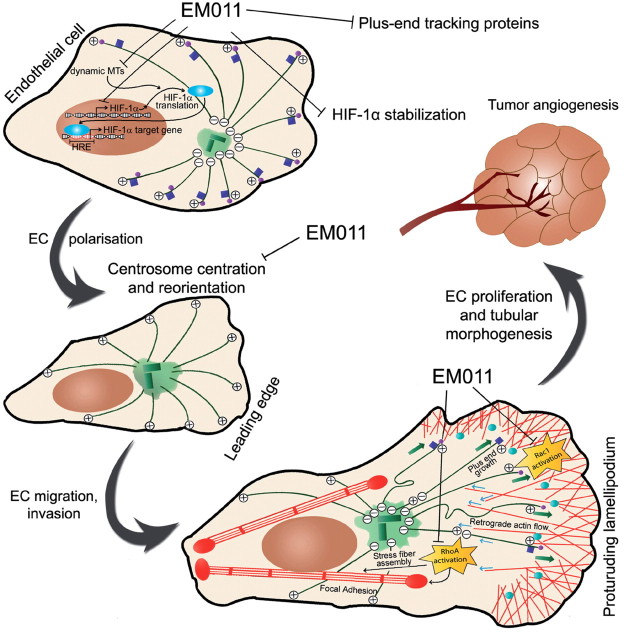

A well-orchestrated interplay between the cytoskeletal armor- actin, microtubules and intermediate filaments is a prerequisite for the regulation of cell migration and angiogenesis. Recent studies have uncovered a role for microtubules targeting to FAs in order to promote FA turnover (53). Targeting involves microtubule tip-complexes and signaling between proteins in microtubules and those in FAs. The frequency of FA targeting by microtubules is highest in the retracting regions; presumably, microtubules deliver multiple ‘relaxing signals’ in these zones to promote adhesion site disassembly (53). One may envisage that EM011-induced dampening of microtubules dynamics, accompanied by a drastic reduction in the localization of plus-end tracking proteins like EB1 and CLIP-170 to microtubules plus-ends, would reduce the frequency and efficacy of microtubules targeting to FAs, thus impairing their turnover and decreasing the cell’s migratory ability. Figure 7 is a schematic model that illustrates the effects of EM011 on various cellular pathways that work in unison to impact the spatiotemporal cascade of events that dictate the migratory process.

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of a working model to demonstrate that EM011 treatment disrupts various aspects of HIF-1α–dependent signaling and impairs cell polarization, migration and tumor angiogenesis. EM011 treatment decreases the transcription of HIF-1α by mechanisms yet to be identified. By attenuating microtubule dynamicity, EM011 also inhibits transport and translation of HIF-1α mRNA and induces proteasome-dependent degradation of HIF-1α. The net decrease in HIF-1α protein levels causes a reduction in expression of HIF-1α–responsive genes, including VEGF and survivin, that are essential for tumor angiogenesis. Reduced microtubule dynamicity also causes diminished binding of plus-end tracking proteins such as EB1 and CLIP-170 to microtubule plus-ends. EM011 inhibits the processes of centrosome centration and reorientation toward the direction of migration, which are crucial to the cell’s ability to perceive and alter the geometry of its actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in order to generate asymmetry between the cell front and rear for locomotion. Migrating cells develop a broad, flat lamellipodium by nucleating actin polymerization at the LE to produce a highly cross-linked meshwork of actin filaments (shown with red lines) whose growing ends face the cell front. Outgrowth of these filaments pushes the LE forward and generates retrograde flow of actin (shown by blue arrows) toward the cell center. Microtubules undergo net growth near the LE (depicted with green arrows) and activate the Rac1 GTPase which is responsible for lamellipodial protrusion and the formation of short-lived, small focal complexes at the lamellipodium base. Microtubules subjected to actin retrograde flow tend to bend and break in the cell body creating depolymerizing microtubule minus-ends and leading to RhoA activation in the cell body. EM011 hinders RhoA activation which normally drives assembly of contractile stress fibers and larger FAs. FAs are targeted by EB1- and CLIP-170–bound dynamic microtubule plus-ends, leading to FA disassembly and cell motility––a process also inhibited by EM011. Thus, EM011 drastically perturbs several crucial steps in endothelial cell migration and eventually, tumor angiogenesis.

Our data also show that EM011 impairs centrosome reorientation toward the direction of migration that perhaps prevented stabilization of lamellipodial extensions. These data imply that drug-mediated effects on microtubule plasticity/dynamics, rather than on gross microtubule organization or expression, are sufficient for inhibition of cell locomotion, a notion supported by studies with other microtubule-altering agents. In addition, we demonstrate that EM011 treatment impairs centrosome centration, which adversely affects the cell’s ability to explore, perceive and regulate its shape and geometry—an ability that is crucial for the generation of cellular asymmetry during cell migration.

Our data also show that EM011 treatment leads to proteasome-mediated degradation of HIF-1α in VHL-deficient RCC4 cells. VHL has been ascribed multiple functions, each possibly linked to tumor suppression. It is widely accepted that VHL acts as part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets HIF-1α for polyubiquitylation and degradation in an oxygen-dependent manner (54). In VHL-defective cancers and in the RCC4 cell line, the HIF-1α-directed transcriptional program is uncoupled from changes in oxygen availability, leading to overproduction of HIF target gene products. Growing evidence now indicates that tumor suppression by VHL also involves the control of a wide variety of HIF-1α-independent processes including microtubule dynamics regulation, primary cilium maintenance, cell proliferation control and responses to DNA damage. Among the HIF-independent functions, VHL has been shown to be a microtubule-associated protein with a dedicated microtubule-stabilizing function: VHL plays a dual role as a catastrophe inhibitor and as a rescue factor and thus protects microtubules from disassembly in vivo (55). It has been recently shown that microtubule dynamicity and integrity are intricately involved in the transport and translation of HIF-1α (14). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that EM011 triggers the degradation of HIF-1α by means other than by the dampening of microtubule dynamicity, it is tempting to propose a model wherein cellular levels of HIF-1α crucially depend on correct regulation of MT dynamics both for the synthesis of HIF-1α protein and for the stabilization and protection of HIF-1α from VHL-independent proteasome-mediated degradation. Our new data thus profoundly influence current models of HIF-1α protein regulation and compel us to rethink the roles of dynamic microtubules in hypoxia signaling and cancer development.

While ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated HIF-1α degradation provides tight control of HIF-1α levels in normoxia, recent studies have revealed that HIF-1α also undergoes constant turnover during prolonged hypoxia via an alternative, VHL-independent pathway that utilizes the proteolytic activity of the 20S proteasome but does not require HIF-1α ubiquitylation (56). Therefore, our data demonstrating VHL-independent HIF-1α degradation upon EM011 exposure is consistent with the existence of multiple mechanisms controlling the levels of this crucial transcription factor, which presumably come into play under different physiological and pathological conditions.

The microtubule-modulating agent EM011 has extensively been shown in vitro and in vivo models to induce selective cytotoxicity in cancer cells while sparing normal cells. Since EM011 appears to dually block VEGF activity, a potent pro-angiogenic factor, in PC-3 cancer cells and directly inhibit cell migration of EC cells, we have identified a novel antiangiogenic role of EM011. In conclusion, our data offer multifarious evidence to suggest that EM011 significantly interferes with several spatiotemporal events that dictate cell motility. Taken together, these data point to a novel mechanism of EM011-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis by disturbing the exquisite cooperativity between microtubules and actin that cross-talk to the HIF signaling to coordinate cell migration and angiogenesis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1– 7 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (1R00CA131489 to R.A.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (30825022 to J.Z.).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Peter Eimon for providing us the transgenic zebrafish. We acknowledge the help of Margaret Long and Sarah Long with the graphics of the model.

P. Karna performed most of the experiments and analyzed data. A. Fritz provided help and expertise with the zebrafish experiments. R. C. Turaga helped with vinculin staining and cell adhesion assays. R. P. Rida analyzed data and contributed toward writing of the paper. J. Gao helped in acquisition of time-lapse images of HUVEC cells. M. Gupta analyzed pathology data. E. Werner helped with the CAM assay and data analysis. C. Yates contributed reagents. J. Zhou contributed vital new reagents and provided useful insights for discussion. R. Aneja designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Abbreviations:

- CAM

chick chorioallantoic membrane

- FA

focal adhesion

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HRE

hypoxia-responsive element

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- LE

leading edge

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VHL

Von Hippel Lindau

References

- 1. Wittmann T, et al. (2001). Cell motility: can Rho GTPases and microtubules point the way? J. Cell Sci. 114 3795–3803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauffenburger D.A., et al. (1996). Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process Cell 84 359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waterman-Storer C.M., et al. (1999). Positive feedback interactions between microtubule and actin dynamics during cell motility Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Small J.V., et al. (2003). Microtubules meet substrate adhesions to arrange cell polarity Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15 40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mabjeesh N.J., et al. (2003). 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF Cancer Cell 3 363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pasquier E., et al. (2006). Microtubule-targeting agents in angiogenesis: where do we stand? Drug Resist. Updat., 9 74–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Escuin D., et al. (2005). Both microtubule-stabilizing and microtubule-destabilizing drugs inhibit hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha accumulation and activity by disrupting microtubule function Cancer Res. 65 9021–9028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayot C., et al. (2002). In vitro pharmacological characterizations of the anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor cell migration properties mediated by microtubule-affecting drugs, with special emphasis on the organization of the actin cytoskeleton Int. J. Oncol. 21 417–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vacca A., et al. (1999). Antiangiogenesis is produced by nontoxic doses of vinblastine Blood 94 4143–4155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pasquier E., et al. (2004). Antiangiogenic activity of paclitaxel is associated with its cytostatic effect, mediated by the initiation but not completion of a mitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathway Mol. Cancer Ther. 3 1301–1310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tozer G.M., et al. (2002). The biology of the combretastatins as tumour vascular targeting agents Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 83 21–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Young S.L., et al. (2004). Combretastatin A4 phosphate: background and current clinical status Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 13 1171–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sweeney C.J., et al. (2001). The antiangiogenic property of docetaxel is synergistic with a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor or 2-methoxyestradiol but antagonized by endothelial growth factors Cancer Res. 61 3369–3372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carbonaro M., et al. Microtubule disruption targets HIF-1alpha mRNA to cytoplasmic P-bodies for translational repression J. Cell Biol. 192 83–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ye K., et al. (2001). Sustained activation of p34(cdc2) is required for noscapine-induced apoptosis J. Biol. Chem. 276 46697–46700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aneja R., et al. (2006). Drug-resistant T-lymphoid tumors undergo apoptosis selectively in response to an antimicrotubule agent EM011 Blood 107 2486–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aneja R., et al. (2006). Rational design of the microtubule-targeting anti-breast cancer drug EM015 Cancer Res. 66 3782–3791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heidemann S. (2006). Microtubules, leukemia, and cough syrup Blood 107 2216–2217 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aneja R, et al. (2006). Treatment of hormone-refractory breast cancer: apoptosis and regression of human tumors implanted in mice Mol. Cancer Ther. 5 2366–2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aneja R., et al. Non-toxic melanoma therapy by a novel tubulin-binding agent Int. J. Cancer 126 256–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karna P., et al. A novel microtubule-modulating noscapinoid triggers apoptosis by inducing spindle multipolarity via centrosome amplification and declustering. Cell Death Differ., 18, 632–644. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landen J.W., et al. (2002). Noscapine alters microtubule dynamics in living cells and inhibits the progression of melanoma Cancer Res. 62 4109–4114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou J., et al. (2003). Brominated derivatives of noscapine are potent microtubule-interfering agents that perturb mitosis and inhibit cell proliferation Mol. Pharmacol. 63 799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aneja R., et al. A novel microtubule-modulating agent induces mitochondrially driven caspase-dependent apoptosis via mitotic checkpoint activation in human prostate cancer cells Eur. J. Cancer 46 1668–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Newcomb E.W., et al. (2006). Noscapine inhibits hypoxia-mediated HIF-1alpha expression andangiogenesis in vitro: a novel function for an old drug Int. J. Oncol. 28 1121–1130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ribatti D., et al. (1995). Endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor is implicated in the vascularization of the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane Dev. Biol. 170 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tran T.C., et al. (2007). Automated, quantitative screening assay for antiangiogenic compounds using transgenic zebrafish Cancer Res. 67 11386–11392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gomes E.R., et al. (2005). Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells Cell 121 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Folkman J. (1990). What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J. Natl Cancer Inst. 82 4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Folkman J. (2003). Angiogenesis inhibitors: a new class of drugs Cancer Biol. Ther. 2 S127–S133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Folkman J., et al. (1987). Angiogenic factors Science 235 442–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Auerbach R., et al. (2003). Angiogenesis assays: a critical overview Clin. Chem. 49 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Isogai S., et al. (2001). The vascular anatomy of the developing zebrafish: an atlas of embryonic and early larval development Dev. Biol. 230 278–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang D., et al. (2001). The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and hematopoiesis in zebrafish development Mech. Dev. 108 29–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Semenza G.L. (2003). Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy Nat. Rev. Cancer 3 721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gotlieb A.I., et al. (1981). Distribution of microtubule organizing centers in migrating sheets of endothelial cells J. Cell Biol. 91 589–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kupfer A., et al. (1982). Polarization of the Golgi apparatus and the microtubule-organizing center in cultured fibroblasts at the edge of an experimental wound Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79 2603–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abraham S., et al. (2009). VE-Cadherin-mediated cell-cell interaction suppresses sprouting via signaling to MLC2 phosphorylation Curr. Biol. 19 668–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ezzell R.M., et al. (1997). Vinculin promotes cell spreading by mechanically coupling integrins to the cytoskeleton Exp. Cell Res. 231 14–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goldmann W.H., et al. (2002). Intact vinculin protein is required for control of cell shape, cell mechanics, and rac-dependent lamellipodia formation Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290 749–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schaller M.D. (2001). Paxillin: a focal adhesion-associated adaptor protein Oncogene 20 6459–6472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Small J.V., et al. (2002). How do microtubules guide migrating cells? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 957–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turner C.E., et al. (1990). Paxillin: a new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions J. Cell Biol. 111 1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Small J.V., et al. (1978). Polarity of actin at the leading edge of cultured cells Nature 272 638–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Svitkina T.M., et al. (1997). Analysis of the actin-myosin II system in fish epidermal keratocytes: mechanism of cell body translocation J. Cell Biol. 139 397–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Henson J.H., et al. (1999). Two components of actin-based retrograde flow in sea urchin coelomocytes Mol. Biol. Cell 10 4075–4090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang Y.L. (1985). Exchange of actin subunits at the leading edge of living fibroblasts: possible role of treadmilling J. Cell Biol. 101 597–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pollard T.D., et al. (2001). Actin dynamics J. Cell Sci. 114 3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hall A. (1998). Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton Science 279 509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rottner K., et al. (1999). Interplay between Rac and Rho in the control of substrate contact dynamics Curr. Biol. 9 640–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nelson C.M., et al. (2004). Vascular endothelial-cadherin regulates cytoskeletal tension, cell spreading, and focal adhesions by stimulating RhoA Mol. Biol. Cell 15 2943–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Burridge K., et al. (1992). Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly J. Cell Biol. 119 893–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaverina I., et al. (1998). Targeting, capture, and stabilization of microtubules at early focal adhesions J. Cell Biol. 142 181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaelin W.G.Jr. et al. (2008). Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway Mol. Cell 30 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hergovich A., et al. (2003). Regulation of microtubule stability by the von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein pVHL Nat. Cell Biol. 5 64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kong X., et al. (2007). Constitutive/hypoxic degradation of HIF-alpha proteins by the proteasome is independent of von Hippel Lindau protein ubiquitylation and the transactivation activity of the protein J. Biol. Chem. 282 15498–15505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]